Abstract

Global warming increases sea temperature and leads to high temperature stress, which affects the yield and quality of Pyropia haitanensis. To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying high temperature stress in a high temperature tolerance strain Z-61, the iTRAQ technique was employed to reveal the global proteomic response of Z-61 under different durations of high temperature stress. We identified 151 differentially expressed proteins and classified them into 11 functional categories. The 4 major categories of these are protein synthesis and degradation, photosynthesis, defense response, and energy and carbohydrate metabolism. These findings indicated that photosynthesis, protein synthesis, and secondary metabolism are inhibited by heat to limit damage to a repairable level. As time progresses, misfolded proteins and ROS accumulate and lead to the up-regulation of molecular chaperones, proteases, and antioxidant systems. Furthermore, to cope with cells injured by heat, PCD works to remove them. Additionally, sulfur assimilation and cytoskeletons play essential roles in maintaining cellular and redox homeostasis. These processes are based on signal transduction in the phosphoinositide pathway and multiple ways to supply energy. Conclusively, Z-61 establishes a new steady-state balance of metabolic processes and survives under higher temperature stress.

Pyropia is an economically important marine red alga used for food, fertilizer, medicine, and chemicals. The farming and processing of Pyropia has become one of the largest seaweed industries in East Asian countries, including China, Japan, and South Korea1,2,3. Pyropia haitanensis, a typical warm temperate zone species originally found south of China, has been extensively cultured in the Fujian, Zhejiang, and Guangdong Provinces for more than 50 years, and its output accounts for about 75% of the total production of Pyropia in China2.

Temperature is the major environmental factor that affects the development, metabolism, productivity, and quality of P. haitanensis. Under natural conditions, P. haitanensis is cultured from September to March of the next year, and the optimal seawater temperature is 14 °C to 26 °C. However, in the early seeding period (September to October in south China), P. haitanensis farms often suffer from consistently high temperatures or the well-known “temperature rebound” as temperature increases following a dramatic drop to temperatures suitable for conchospore release and germination4. The persistence of high temperatures can negatively affect P. haitanensis blades by inhibiting the survival and division of these conchospores. In addition, germlings become prone to disease, premature senility, and eventual decay, leading to a substantial reduction in yield5. In recent years, high temperatures have markedly affected P. haitanensis cultivation and reduced its yield6. Furthermore, according to reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, high temperature stresses will increase in the near future due to global climate change. To adapt to global climate change and sustain Pyropia cultivation, several high temperature tolerance strains (Z-26, Z-61, and ZS-1) of P. haitanensis have been selected and widely cultivated in South China5,7. Therefore, a better understanding of the high temperature tolerance mechanisms in these tolerant strains would lay the theoretical foundation for further cultivar breeding of Pyropia.

The mechanisms of responding to high temperature stress have been investigated in a great deal of higher plants, especially in model plants and economic crops, and various mechanisms have been summarized. These include membrane stability maintenance, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, antioxidants production, the accumulation and adjustment of compatible solutes, the induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) cascades, and, most importantly, chaperone signaling and transcriptional activation8,9,10,11. However, much less is known about the mechanisms of high temperature tolerance in algae. To understand the physiology and molecular mechanisms underlying P. haitanensis high temperature stress responses, Zhang et al. compared the physiological response of a high temperature tolerance strain (Z-61) to that of a wild-type strain, and found that Z-61 induces its antioxidant and osmoregulation systems, whereas the wild-type strain only induces its osmoregulation system during high temperature stress3. Furthermore, the baseline activity of the antioxidant enzymes differed significantly between the 2 strains3. Recently, high throughput experimental methods such as transcriptomics and proteomics were also utilized to identify stress-responsive genes and proteins regulated by elevated temperatures in Pyropia. Transcriptomic work in Z-61 revealed that its high temperature response is characterized by rapid reprogramming of gene expression machinery leading to up- and down-regulation of thousands of genes within minutes of exposure to high temperature stress12. Additionally, the stress-related genes involved in several pathways have been identified, such as redox homeostasis, photosynthesis, energy metabolism, polysaccharide and cell wall metabolism, and defense. However, since changes in transcription often do not correspond with changes in protein expression13, comparative proteomic analysis based on 2-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) was conducted to screen the differentially expressed proteins in Z-61 under normal temperature and high temperature stress. Fifty-nine differentially expressed proteins, which involved processes such as photosynthesis, energy metabolism, redox homeostasis, response to stimuli, were identified6.

Proteins represent biochemical machinery and the functional processes of how an organism responds to a changing environment. Meanwhile, proteomics presents an effective approach to pursue a systems-based perspective of how proteins change, and thus how organisms adapt to various abiotic environments14. However, traditional gel-based proteomics is biased towards hydrophilic proteins with higher abundances and intermediate Mr and pI properties. Therefore, this technique is not sufficient for higher coverage and more accurate quantification in proteomic studies15. In recent years, new mass spectrometry-based proteomic techniques, such as isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) and Isotope-coded affinity tags (ICAT), have been applied for proteomic analysis. Among them, iTRAQ is the most popular technique in plant quantitative proteomics16,17. This technique is based on tagging the N-terminus of peptides generated from tryptic protein digests, which overcomes some limitations of gel-based techniques and also improves the throughput of proteomic studies. Furthermore, this technique has a high degree of sensitivity, and the amine specific isobaric reagents permit the identification and quantitation of up to 8 different samples simultaneously16,17. Thus, in this paper, we employed iTRAQ and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to further understand the molecular mechanisms underlying high temperature stress in Pyropia and reveal the global proteomic response of the Z-61 stains of P. haitanensis under high temperature stress.

Results

Overview of Quantitative Proteomics

A total of 269614 spectra were obtained from the iTRAQ-LC-MS/MS proteomic analysis of all Z-61 samples. After data filtering to eliminate low-scoring spectra, a total of 97072 unique spectra that met the strict confidence criteria for identification were matched to 1895 unique proteins (Supplementary Information Tables S1 and S2).

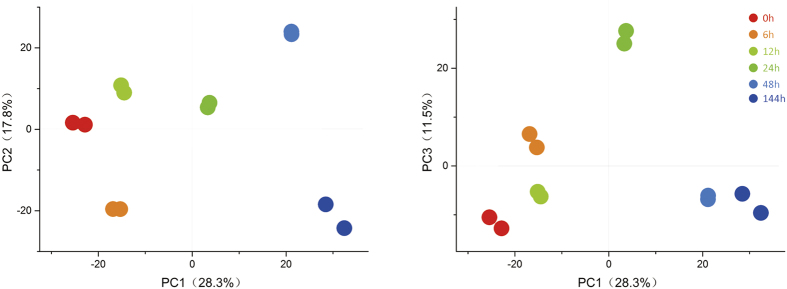

To assess the reproducibility of the iTRAQ data, PCA was performed on every 2 replicates at each time point (Fig. 1). Results show that the iTRAQ data in 2 replicates at each time point were almost unanimous, and different time points were clearly separated, suggesting that protein abundance changed with prolonged high temperature stress.

Figure 1. PCA of iTRAQ data in each treatment of high temperature stress.

Numbers in parentheses represent the percentage of total variance explained by the first, second, and third PC. The 2 biological replicates of a treatment are represented by dots of the same color.

Expression Profile of Differentially Expressed Proteins

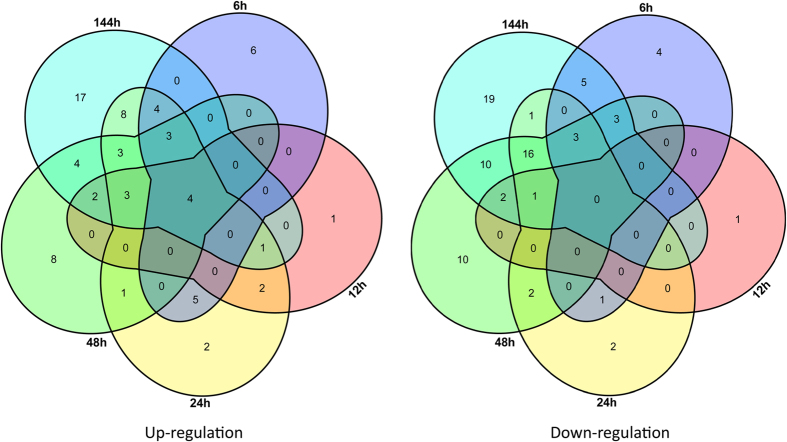

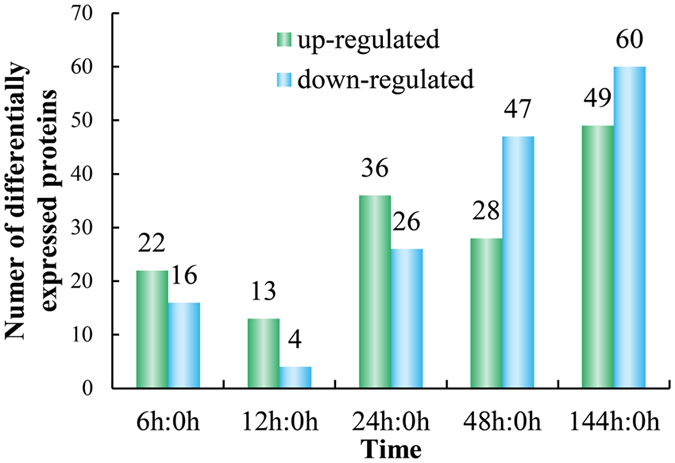

Among proteins that showed a significant change (P < 0.05) in abundance, 151 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were chosen by a ratio >1.50 or <0.67 at least in 1 time point under high temperature stress (Supplementary Information Table S2), representing 7.97% of the total identified proteins. In the control (0 h), and at 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 144 h of high temperature stress, 22, 13, 36, 28, and 49 proteins were up-regulated, while 16, 4, 26, 47, and 60 proteins were down-regulated, respectively (Fig. 2). Among these proteins, the number (17) of DEPs was the least between 12 h and 0 h, and the number (109) of DEPs was the most between 144 h and 0 h. We then analyzed the Venn diagram of the DEPs at different time points (Fig. 3). This diagram shows that different proteins work at different time points. Additionally, 4 DEPs were up-regulated at all time points: 2 disulfide isomerases, 1 hsp70, and 1 unknown protein.

Figure 2. Numbers of differentially expressed proteins in each comparison.

The numbers above the bars show the quantity of up-(green) and down-(blue) regulated expression proteins.

Figure 3. Venn diagram of differentially expressed proteins.

The sum of the numbers in each large circle represents the total number of differentially expressed proteins among various combinations; the overlapping parts of the circles represents common differentially expressed proteins between combinations.

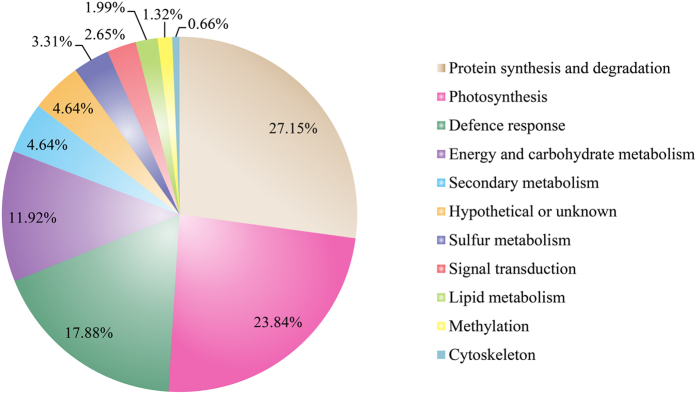

Functional Classification of Differentially Expressed Proteins

DEPs are classified into 11 categories according to their putative biological functions (Supplementary Information Table S3). Figure 4 shows these functional classification. The majority of DEPs (80.79%) are classified into 4 categories: protein synthesis and degradation (27.15%), photosynthesis (23.18%), defense response (17.88%), and energy and carbohydrate metabolism (12.58%). The other categories are as follows: secondary metabolism (4.64%), sulfur metabolism (3.31%), signal transduction (2.65%), lipid metabolism (1.99%), methylation (1.32%), cytoskeleton (0.66%), and hypothetical or unknown (4.64%).

Figure 4. Functional categorization of the 154 differentially expressed proteins.

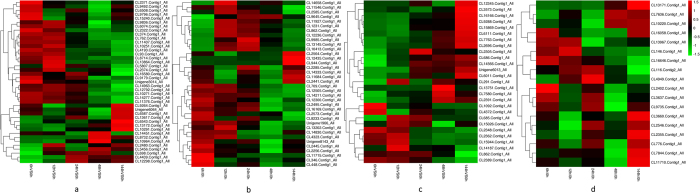

Based on hierarchical cluster analysis, we grouped the DEPs in the main categories during high temperature stress (Fig. 5). For protein synthesis and degradation (Fig. 5a), several enzymes involved in protein synthesis were down-regulated. On the contrary, proteins related to degradation were up-regulated. For photosynthesis (Fig. 5b), most proteins decreased, including photosystem II (PSII)-related proteins, phycobiliproteins, and proteins involved in the Calvin cycle. In contrast, for the defense response (Fig. 5c), many proteins were up-regulated, such as molecular chaperones, antioxidant enzymes, and metacaspases. Lastly, for energy and carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 5d), several proteins participated in glycolysis and the citric acid cycle were up-regulated.

Figure 5. Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed proteins with similar functions under high temperature stress.

(a) Proteins related to protein synthesis and degradation; (b) Proteins related to photosynthesis; (c) Proteins related to the defense response; (d) Proteins related to energy and carbohydrate metabolism.

Discussion

In recent years, transcriptomics and proteomics technologies have been widely applied to identify stress-responsive genes and proteins that are regulated by environmental stress in aquatic organisms18. Compared to transcriptomics, proteomics provides not only information at a mechanistic level but can also capture changes in protein activity measured as post-translational modifications19. Previously reported P. haitanensis proteomics studies were limited to 2D gel electrophoresis analysis6. However, this technique has several limitations, such as the low number of proteins it can identify and quantification inaccuracy, which limits its application for comprehensive analysis of proteome changes20. Although most proteomics studies in plants and algae have used 2D gel approaches, alternative methods such as iTRAQ and ICAT are now available21. In the present study, based on the iTRAQ technique, we successfully identified 151 proteins showing significant differential accumulation after high temperature stress. These proteins provide new insights into the mechanism of Pyropia responding to heat stress.

Protein Synthesis and Degradation

High temperature stress can repress the synthesis of proteins22,23. In this study, several proteins involved in protein synthesis were down-regulated, including threonine and tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase, ribosomal proteins, transaminases, threonine synthase, choline dehydrogenase, and nitrite reductase. However, it seems strange that some eukaryotic initiation factors (eIF) and protein synthesis elongation factors were up-regulated under high temperature stress (Supplementary Information Table S3). This may reveal the complexity of expression patterns for initiation and elongation factors following thermal stress24. In some previous studies, a high accumulation of eIF has been reported to induce cellular reorganization leading to PCD on a long-term exposure to high temperature stress25,26. Some other previous studies have also implicated the protein synthesis elongation factor in plant response to high temperature stress27,28. Elongation factors display chaperone activity, and it has been suggested that high temperature-induced accumulation of elongation factors is important for high temperature stress tolerance in plants. For example, cultivars expressing a higher elongation factor under high temperature stress were more tolerant to high temperature stress29.

High temperature stress is also associated with an enhanced risk of improper protein folding and denaturation30. The misfolded and denatured proteins may accumulate in cells under high temperature stress, which, if unchecked, leads to cell death. Two strategies solve this problem: refolding them or removing them. Several disulfide-isomerases, which play important roles in the folding of nascent polypeptides and in the proper formation of disulfide bonds in protein folding31, were observed to be up-regulated after heat treatment. Proteases, which remove the unfolded, denatured proteins and release amino acids for recycling32, were also up-regulated. Other proteins involved in removing the misfolded and denatured proteins were up-regulated as well, such as the glycine cleavage system p-protein and polyubiquitin (Supplementary Information Table S3).

Furthermore, vacuolar sorting protein, responsible for transport, was up-regulated under high temperature stress. This may provide cells with extra flexibility to cope with changing environmental conditions33. These results suggest when under high temperature stress, P. haitanensis reduced the production of proteins to avoid misfolding, and increased some enzymes to remove misfolded and denatured proteins.

Photosynthesis

Due to its complex mechanisms and requirement for enzymes, photosynthesis is particularly sensitive to heat stress. Changes in environmental temperature are reflected by photosynthesis, which triggers a response aimed at achieving the best possible performance under new conditions34. In this study, we identified 35 DEPs involved in photosynthesis, which accounted for 23.18% of all DEPs.

The first step of photosynthesis is light absorption. In contrast to higher plants, Pyropia has intricate light-harvesting systems comprised of phycobilisomes (PBSs), which are made of phycobiliproteins (PBPs) and linker polypeptides35. PBPs are divided into 3 main groups: allophycocyanin (APC), phycocyanin (PC), and phycoerythrin (PE). Light energy absorbed by PE migrates first to PC, then to APC, and finally to chlorophyll a36. In our study, we found 2 APC and 1 PE (Supplementary Information Table S3). Down-regulated expression of these proteins under high temperature stress indicated that their capacity for transferring light energy decreased. It is interesting that a light harvesting protein sharply increased at 144 h of heat treatment while APC and PE decreased (Supplementary Information Table S3). This may suggest that the protein takes charge of absorbing light under long-term heat stress. Additionally, a linker polypeptide was detected to be up-regulated. It functioned like linker polypeptides, which stabilize the PBS structure and optimize absorbance characteristics and energy transfer37.

PSII is more thermolabile than photosystem I (PSI), and has been long believed to be a prominent heat sensitive component of photosynthesis as its activity can be greatly reduced or even partially stopped under high temperature stress38. In the present study, the abundance of many proteins related to PSII was down-regulated, such as PsbU, PsbB, PsbS, PsbQ, cytochrome c550, and low PSII accumulation protein. However, PsaA, which is involved in PSI, was up-regulated (Supplementary Information Table S3). This means that high temperature stress can significantly decrease the PSII activity in P. haitanensis, but not in PSI, and the PSI-driven cyclic electron flow allows Pyropia to survive in stress conditions39,40.

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase), fructose bisphosphate aldolase, ribose-5-phosphate isomerase, and transketolase, which are involved in the Calvin cycle41, decreased under high temperature stress. Moreover, ferredoxin also decreased. This protein can modulate the activities of FBPase and SBPase42. The down-regulated expression of these proteins further suggests that high temperature stress inhibited photosynthesis in P. haitanensis.

Although most photosynthesis-related proteins down-regulated under heat stress, it is worth mentioning that carbonic anhydrase (CA) and oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1 (OEE) were up-regulated (Supplementary Information Table S2). CA plays a crucial role in the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) in algae43. In a previous study, several CA genes (PhαCA1, PhβCA2, PhβCA3, and PhγCA1) in P. haitanensis were found up-regulated during high temperature stress44. High temperature stress inhibits the utilization of inorganic carbon in P. haitanensis, and the higher the temperature, the lower the utilization45. As the key enzyme of inorganic carbon utilization, the CA level must be up-regulated to maintain the equilibrium between CO2 and HCO3− during stress. In addition to function in CCM, CA also shows antioxidant activity and plays a role in the hypersensitive defense response46. Expression of a rice carbonic anhydrase gene (OsCA1) and CA activity were up-regulated by some environmental stresses, and a transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing OsCA1 had a greater salt tolerance at the seedling stage than wild-type plants47. Additionally, recent research in Capsosiphon fulvescens showed that OEE is also an excellent antioxidant48.

Based on the expression of proteins related to photosynthesis, we conclude that P. haitanensis limited damage to a repairable level by reducing photosynthesis under high temperature stress.

Defense Response

Twenty-seven identified DEPs were functionally characterized as being involved in the defense response (Supplementary Information Table S3), which was classified into molecular chaperone, redox homeostasis, programmed cell death, and others.

An essential component of acquired thermotolerance in plants and other organisms is the induction and synthesis of molecular chaperones or heat shock proteins (HSPs)49. A wide range of proteins have chaperone activity. Moreover, many molecular chaperones were originally identified as heat-shock proteins50. In plants, well-characterized HSPs are grouped into 5 different families: HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and sHSP51. Excluding HSP100, all other heat-shock proteins identified in the present study were up-regulated (Supplementary Information Table S3). Furthermore, HSP70 was the most abundant, indicating its fundamental role in response to high temperature stress52. The up-regulation of these HSPs prevent denaturation of other proteins caused by high temperature, and thus improve the high temperature tolerance of P. haitanensis. Calnexin is an endoplasmic reticulum-localized molecular chaperone protein involved in the folding and quality control of proteins53. Previous study identified that the accumulation of calnexin helps plants deal with abiotic stresses54. The up-regulation of calnexin observed in this study (Supplementary Information Table S3) may suggest that calnexin work as a molecular chaperone and play an important role in responding to high temperature stress in P. haitanensis.

High temperature stress may disturb cellular redox homeostasis and promote the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Excessive ROS could damage cellular components. To cope with oxidative stress, cells have developed a wide range of antioxidant systems55,56,57,58. In this study, several antioxidant enzymes were identified (Supplementary Information Table S3), including ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), and methionine sulfoxide reductase (MSR). In contrast with the down-regulation of APX, CAT and MSR were up-regulated under high temperature stress. As an antioxidant, thioredoxin (TRX) can also protect cells from oxidative damage59. Although we could not find TRX in the DEPs, we did detect 2 related enzymes: methionine-S-oxide reductase, which is responsible for the TRX synthesis and was up-regulated under heat stress, and TRX reductase, which reduces TRX and was down-regulated. Furthermore, quinone oxidoreductase, which works as a superoxide scavenger60, increased under high temperature stress. The expression of these antioxidant enzymes suggest that they may play important roles in the pathway for scavenging ROS and contribute to the survival of P. haitanensis blades when under high temperature stress.

Programmed cell death (PCD) in plants is a crucial component of development and defense mechanisms61. PCD is triggered by the sequential activation of cysteine proteases known as caspases, and the inactive precursors of caspases (procaspases) is induced by the release of electron carrier protein cytochrome c62. Supplementary Information Table S2 shows that cytochrome c maintained its expression before 48 hours of heat treatment. We also observed an increase in metacaspase. This may suggest that PCD is also involved in the high temperature response of P. haitanensis. Accumulating evidence shows that PCD is triggered by different environmental factors such as high light, ultraviolet radiation, drought, salt, heat, cold, or flooding. Upon reaching certain thresholds with these changes, plant cells can no longer maintain proper metabolic processes and PCD is induced63. Although it is unfavorable for biomass production, the selective death of cells and tissues under abiotic stresses eventually provides survival advantages for the whole organism63.

Other stress-related proteins such as polyamine oxidase, stress-induced protein, and aldehyde dehydrogenase, were up-regulated to deal with high temperature stress (Supplementary Information Table S3). Several reports have shown that these proteins play a part in abiotic stress responses in plants64,65.

In conclusion, the defense response of P. haitanensis under high temperature stress is complicated and involves molecular chaperones, antioxidant systems, PCD, and other stress-related proteins. These proteins work together to maintain cellular and redox homeostasis.

Energy and Carbohydrate Metabolisms

Plants respond to stress conditions by triggering a network of events linked to energy and carbohydrate metabolism66. As expected, energy and carbohydrate metabolism were affected by heat in this research. The DEPs involved in energy and carbohydrate metabolism were divided into 4 groups: glycolysis, citric acid cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, and others (Supplementary Information Table S3).

Glycolysis is a metabolic pathway that oxidizes glucose to generate ATP, reductant, and pyruvate67. Under high temperature, all glycolysis-related proteins were up-regulated, including glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, enolase, transaldolase, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The citric acid cycle is a series of chemical reactions that produce energy. Citrate synthase and aconitate hydratase, which belong to this pathway, were up-regulated under heat stress. Similar to glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway generates NADPH and pentoses. Apart from the above-mentioned enzymes, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase and ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase were inhibited by heat stress. Furthermore, other proteins such as galactose kinase, UDP-glucose 4-epimerase, V-type proton ATPase, and ATP/ADP translocator, were up-regulated. These proteins are core members in energy and carbohydrate metabolism. In our study, due to many proteins being involved in the complex network of energy metabolism, it is unsurprising that proteins with different abundance profiles were identified. These results suggest that the blades of P. haitanensis require high energy levels to fuel defense mechanisms and repair damage under high temperature stress.

Secondary Metabolism

Secondary metabolites of plants often refer to compounds that have no fundamental role in the maintenance of life processes but are important for interaction with the environment for adaptation and defense68. Several enzymes that participate in isoprenoid, terpenoid, riboflavin, and nucleotide sugars metabolism decreased in the present research. They are 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase, farnesyltransferase, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase, FAD synthetase, and UDP-sulfoquinovose synthase. A previous study showed that stressed plants are expected to have reduced metabolic activities because of a reduced level of photosynthetic activity and reduced uptake of nitrogen from the soil69. Our results confirmed this point.

Sulfur Metabolism

Sulfur is a ubiquitous and essential element for plants70. Sulfur metabolism is important for biochemical and physiological processes, including redox cycles, enzyme activity regulation, and heavy metal and xenobiotic detoxification. In plants, abiotic stress affects sulfur metabolism, leading to the activation of a wide range of adaptive responses71,72. Five dysregulated proteins were classified into sulfur metabolism (Supplementary Information Table S3), while cysteine synthase and sulfate adenylyltransferase are enzymes involved in sulfur assimilation. The up-regulation of these proteins suggests that sulfur is required for P. haitanensis to adapt to heat stress.

Signal Transduction

The process by which plant cells sense stress signals and transmit them to cellular machinery to activate adaptive responses is referred to as signal transduction73. In other words, the initial high temperature stress signals must be transmitted by some signaling molecules and trigger downstream signaling processes and transcription controls, which in-turn activate stress-responsive mechanisms to reestablish homeostasis and protect and repair damaged proteins and membranes. In the present study, the receptor of activated protein kinase C (RACK) was up-regulated. RACK regulates various signaling pathways ranging from developmental processes to immune and stress responses in plants74. Additionally, 2 proteins that participate in inositol metabolism were found. Inositol serves as an important component of the phosphoinositide pathway, which is essential for plant survival in a changing environment75,76. The up-regulation of these 2 proteins indicate that the phosphoinositide pathway may play important roles in the signal transduction of P. haitanensis when under high temperature stress.

Lipid Metabolism

Lipids are linked to many cellular functions including storage for energy generation and membrane synthesis77. Previous research found that under high temperature stress, P. haitanensis increased energy metabolism to maintain physiological balance7. In this study, acyl-CoA binding protein and glyoxysomal beta-ketoacyl-thiolase, which participates in fatty acid beta-oxidation, increased at high temperature. This expression reflects that when coping with high temperature stress, P. haitanensis can also use lipids as an energy source.

Methylation

DNA methylation is an important mode of epigenetic modification in plants. It plays vital roles in regulating growth and development in plants, and is involved in responses to a variety of stresses. Environmental stimuli adjust gene networks associated with the stress response by changing the level and pattern of DNA methylation, thereby enhancing adaptation to various stresses78. S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase, which utilizes the methyl donor (SAM) as a cofactor to methylate nucleic acids, was down-regulated. This may increase the expression of some genes and proteins, thus protecting P. haitanensis from abiotic stress.

Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton in plant cells plays important roles in controlling cell shape and mediating intracellular signaling, and can undergo profound changes when under abiotic stress79. Tubulin is the major constituent of microtubules. It binds 2 moles of GTP, one at an exchangeable site on the beta chain and one at a non-exchangeable site on the alpha chain. Here, the up-regulation of the tubulin beta chain in response to high temperature stress indicated its function in P. haitanensis cellular homeostasis.

Conclusions

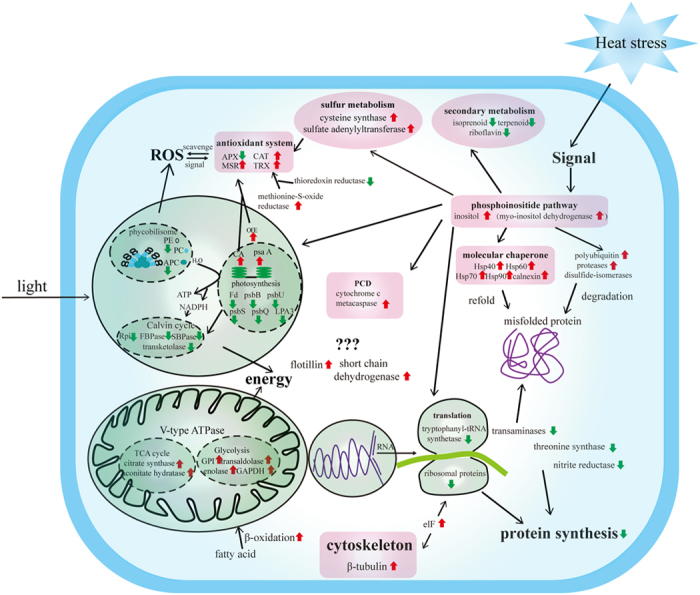

A significant number of stress-responsive proteins were identified from the Z-61 stain of P. haitanensis using the iTRAQ technique. The expression of these proteins shows that there is a clear response to high temperature in Z-61 (Fig. 6). The mechanism is as follows:

Figure 6. Cell diagram of Pyropia haitanensis mechanisms involved in high temperature stress tolerance.

Down-regulated proteins are indicated by  , whereas up-regulated proteins are indicated by

, whereas up-regulated proteins are indicated by  , hypothetical or unknown proteins are indicated by ???.

, hypothetical or unknown proteins are indicated by ???.

Under high temperature stress, photosynthesis, protein synthesis, and secondary metabolism are inhibited to limit damage to a repairable level. As time progresses, misfolded proteins and ROS accumulate, which are harmful to cells. This leads to the up-regulation of molecular chaperones, proteases, and antioxidant systems. It is inevitable that some cells are injured by high temperature, but PCD aims to remove them. Furthermore, sulfur assimilation and the cytoskeleton efficiently maintain cellular and redox homeostasis. In this process, the phosphoinositide pathway works as the major player for signal transduction. All these aforementioned behaviors require significant energy. Therefore, glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and beta-oxidation of fatty acids are up-regulated. In summary, all observed changes were aimed at establishing a new steady-state balance of metabolic processes to enable continual Z-61 function and survival under higher temperatures.

Materials and Methods

Plants and Stress Treatment

The Z-61 strain of P. haitanensis, which is tolerant to high temperatures and grows with a high yield, were used in this study. Samples were selected and purified by researchers working in the Laboratory of Germplasm Improvements and Applications of Pyropia in Jimei University, Fujian Province, China. Sixty 15 ± 2 cm long blades of Z-61 were randomly selected and cultured in 12 aerated flasks (2000 mL) with 5 blades each at 29 °C (high temperature), and were illuminated by 50–60 mol m−2s−1 photons (10:14, L:D) for 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 144 hours. Each sample had 2 biological replicates. The cultured medium was natural seawater enriched with MES medium.

Protein Extraction

Blade proteins were extracted according to a previously published method80. Briefly, blades were ground in a precooled mortar in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Approximately 0.2 g of the homogenate was precipitated for 2 h with 10 mL acetone, 10% trichloroacetic acid, 0.07% β-mercaptoethanol (BME), and 0.2% polyvinylpyrrolidone at −20 °C. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was rinsed 3 times in ice-cold acetone (including 0.07% BME). Between rinsing steps, samples were incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. Then, the pellet was air-dried, resuspended in 5 mL lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 65 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 4% CHAPS, 1 mM PMSF, and 2 mM EDTA), and vortexed for 1 h at room temperature. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and mixed well with ice-cold acetone (1: 4, v/v) with 30 mM DTT. After repeating this step twice, supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for iTRAQ analysis.

Protein Digestion and iTRAQ Labeling

For digestion, the 300-μg protein pellet from the previous step was resuspended in digestion buffer (100 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), 0.05% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)) to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL (total protein measured by bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)). Equal aliquots (500 μg) from each lysate were then digested with trypsin (Sigma; 1: 40 w/w) overnight at 37 °C in a sealed tube. The tryptic peptides were then lyophilized and dissolved in the 50% TEAB buffer, and the trypsin digested samples were analyzed using MALDI-TOF/TOF to ensure complete digestion.

The iTRAQ labeling of peptide samples derived from each time point of high temperature stress was performed using iTRAQ Reagent-8plex Multiplex Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For each time point (i.e., 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, or 144 h), 12 samples (2 biological replicates) were iTRAQ labeled. Peptides were labeled with respective isobaric tags (113 for 0 h; 114 for 6 h; 115 for 12 h; 116 for 24 h; 117 for 48 h; and 118 for 144 h), incubated for 2 h, and vacuum centrifuged to dryness.

Labeled peptides were then fractionated using Polysulfoethyl A SCX columns (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size, 200A° pore size) using an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. Retained peptides were eluted using Buffer A (10 mM KH2PO4 in an aqueous solution of 25% acetonitrile acidified to a pH of 3.0 with H3PO4) and Buffer B (Buffer A with 500 mM KCl). The following chromatographic gradients were applied: 0–25 min 100% Buffer A; 25–32 min 90% Buffer A and 10% Buffer B; 32–42 min 80% Buffer A and 20% Buffer B; 42–47 min 55% Buffer A and 45% Buffer B; 47–60 min 100% Buffer B; 60–75 min 100% Buffer A. Chromatograms were recorded at 214 nm. The collected fractions were desalted with Sep-Pak Vac C18 cartridges (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts), concentrated to dryness using vacuum centrifuge, and reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Protein digestion and iTRAQ labeling was conducted in 2 technical replicates.

LC-MS/MS Proteomic Analysis

The SCX peptide fractions were pooled to obtain 10 final fractions and reduce the number of samples and collection time. A 10-μL sample from each fraction was injected 3 times to the Proxeon Easy Nano-LC system. Peptides were separated on a C18 analytical reverse phase column (ID 75 μm × 10 cm, 200Å, 3 μm particles) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min and a linear LC gradient profile was used to elute peptides from the column. We then analyzed the fractions using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Data were acquired using a data-dependent acquisition mode in which, for each cycle, the 10 most abundant multiply-charged peptides (2+ to 4+) with an m/z between 300 and 1800 were selected for MS/MS with 15 s dynamic exclusion setting. The fragment intensity multiplier was set to 20 and the maximum accumulation time was 2 s. Peak areas of the iTRAQ reporter ions reflected the relative abundance of proteins in the samples.

Data Analysis

For iTRAQ/Shotgun protein identification, the raw mass data were processed with Proteome Discover 1.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and searched with in-house MASCOT software 2.3.02 (Matrix Science, London, U.K.) against the P. haitanensis UniGene database, which was obtained from whole transcriptome sequencing12. In the database search, all parameters were set as follows: specifying trypsin as the digestion enzyme; the carbamidomethylation of cysteine and iTRAQ 8plex modification of the N terminus and K as fixed modifications; iTRAQ 8plex modification of Y and oxidation on methionine as variable modification; the initial precursor mass tolerance to 20 ppm and the fragment ion level to 0.1 Da; and the maximum missed cleavages as 2. The data files generated by MASCOT were processed using Scaffold Q+ (Proteome Software, Portland). For iTRAQ quantification, the peptide for quantification was automatically selected by the algorithm to calculate the reporter peak area, error factor (EF), and p value. The resulting data set was auto bias-corrected to remove any variations due to unequal mixing during combining differently labeled samples. The average value of 2 biological replicates and 2 technical replicates were used to indicate the final protein abundances at a given time point. Proteins with a 1.5-fold change between samples and a p value less than 0.05 were determined as differentially expressed proteins.

Principal Component Analysis and Venn Diagram Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis was performed using the prcomp package, calculation was based on a singular value decomposition, and Fig. 1 were drawn by OriginPro 9.1. Venn diagram analysis was performed online (http://www.omicshare.com/tools/index.php/Home/Soft/venn).

Functional Classification and Enrichment Analysis

Differently expressed proteins were functionally classified according to MapMan ontology81. Enrichment analysis was conducted using the singular enrichment analysis (SEA) tool in the agriGO toolkit82. Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis of responsive proteins was conducted according to information from the KEGG Pathway Database.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Shi, J. et al. Differential Proteomic Analysis by iTRAQ Reveals the Mechanism of Pyropia haitanensis Responding to High Temperature Stress. Sci. Rep. 7, 44734; doi: 10.1038/srep44734 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos: 41276177), and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian, China (Grant Nos 2014J07006 and 2014J05041). The authors thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions C.S.C. and C.T.X. designed the experiments. J.Z.S., Y.T.C., Y.X., and D.H.J. conducted the experiments. J.Z.S., Y.T.C., Y.X., and C.T.X. analyzed the data. J.Z.S. and C.T.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Behura S., Sahoo S. & Srivastava V. K. Porphyra: the economic seaweed as a new experimental system. Curr. Sci. 83(11), 1313 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Blouin N. A., Brodie J. A., Grossman A. C., Xu P. & Brawley S. H. Porphyra: a marine crop shaped by stress. Trends. Plant. Sci. 16(1), 29–37 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland J. E. et al. A new look at an ancient order: generic revision of the Bangiales (Rhodophyta). J. Phycol. 47(5), 1131–1151 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xie C. T., Chen C. S., Ji D. H. & Zhou W. W. Physiological responses of gametophytic blades of Porphyra haitanensis to rising temperature stresses (in Chinese). J. Fish. China. 35, 379–386 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yan X. H., Lv F., Liu C. J. & Zheng Y. F. Selection and characterization of a high-temperature tolerant strain of Porphyra haitanensis Chang et Zheng (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 22(4), 511–516 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Chen C., Ji D., Hang N. & Xie C. Proteomic profile analysis of Pyropia haitanensis in response to high-temperature stress. J. Appl. Phycol. 26(1), 607–618 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. S. et al. Preliminary study on selecting the high temperature resistance strains and economic traits of Porphyra haitanensis (in Chinese). Acta. Oceanol. Sin. 30, 100–106 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A., Gelani S., Ashraf M. & Foolad M. R. Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 61(3), 199–223 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Finka A. & Goloubinoff P. How do plants feel the heat? Trends Biochem. Sci. 37(3), 118–125 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M., Nahar K., Alam M. M., Roychowdhury R. & Fujita M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14(5), 9643–9684 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driedonks N., Xu J., Peters J. L., Park S. & Rieu I. Multi-level interactions between heat shock factors, heat shock proteins, and the redox system regulate acclimation to heat. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 999 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B. The global transcriptome of Pyropia haitanensis and digital gene expression profile analysis under high-temperature stress (in Chinese). Master’s thesis, Jimei university, Xiamen (2013).

- Muers M. Gene expression: Transcriptome to proteome and back to genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12(8), 518–518 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomanek L. Proteomics to study adaptations in marine organisms to environmental stress. J. Proteomics. 105, 92–106 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachi A. & Bonaldi T. Quantitative proteomics as a new piece of the systems biology puzzle. J. Proteomics. 71(3), 357–367 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C. H. & Bern M. Recent developments in quantitative proteomics. Mutat. Res-Gen. Tox. En. 722(2), 171–182 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnouin K. Special issue in quantitative mass spectrometric proteomics. Amino Acids. 43(3), 1005–1007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew B. & Napier J. Application of genetics and genomics to aquaculture development: current and future directions. J. Agric. Sci. 149(S1), 143–151 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues P. M., Silva T. S., Dias J. & Jessen F. Proteomics in aquaculture: applications and trends. J. Proteomics. 75(14), 4325–4345 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze W. X. & Usadel B. Quantitation in mass-spectrometry-based proteomics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 491–516 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owiti J. et al. iTRAQ-based analysis of changes in the cassava root proteome reveals pathways associated with post-harvest physiological deterioration. Plant J. 67(1), 145–156 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. F. & Hershey J. W. Protein synthesis and protein phosphorylation during heat stress, recovery, and adaptation. J. Cell Biol. 109(4), 1467–1481 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulen H. & Eris A. Effect of heat stress on peroxidase activity and total protein content in strawberry plants. Plant Sci. 166(3), 739–744 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Majoul T., Bancel E., Triboï E., Ben Hamida J. & Branlard G. Proteomic analysis of the effect of heat stress on hexaploid wheat grain: characterization of heat-responsive proteins from non-prolamins fraction. Proteomics. 4(2), 505–513 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. et al. Heat stress-induced response of the proteomes of leaves from Salviasplendens Vista and King. Proteome Sci. 11(1), 25 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins J. A., Habte E., Templer S. E., Colby T., Schmidt J. & Korff M. Leaf proteome alterations in the context of physiological and morphological responses to drought and heat stress in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J. Exp.Bot. 64(11), 3201–3212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad P. V., Pisipati S. R., Mutava R. N. & Tuinstra M. R. Sensitivity of grain sorghum to high temperature stress during reproductive development. Crop Sci. 48(5), 1911–1917 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Pressman E., Peet M. M. & Pharr D. M. The effect of heat stress on tomato pollen characteristics is associated with changes in carbohydrate concentration in the developing anthers. Ann. Bot. 90(5), 631–636 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bita C. & Gerats T. Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 273 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosová K., Vítámvás P., Prášil I. T. & Renaut J. Plant proteome changes under abiotic stress—contribution of proteomics studies to understanding plant stress response. J. Proteomics. 74(8), 1301–132 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston N. L., Fan C., Schulze J. M., Jung R. & Boston R. S. Phylogenetic analyses identify 10 classes of the protein disulfide isomerase family in plants, including single-domain protein disulfide isomerase-related proteins. Plant Physiol. 137(2), 762–778 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Liu C. & Chen X. Proteomics of rice in response to heat stress and advances in genetic engineering for heat tolerance in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 30(12), 2155–2165 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang L., Etxeberria E. & den Ende W. Vacuolar protein sorting mechanisms in plants. FEBS J. 280(4), 979–993 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M. & Harris P. J. C. Photosynthesis under stressful environments: an overview. Photosynthetica. 51(2), 163–190 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lin A. P., Wang G. C., Yang F. & Pan G. H. Photosynthetic parameters of sexually different parts of Porphyra katadai var. hemiphylla (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) during dehydration and re-hydration. Planta. 229(4), 803–810 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonoff W. A. & MacColl R. Biliproteins and phycobilisomes from cyanobacteria and red algae at the extremes of habitat. Arch. Microbiol. 176(6), 400–405 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. N., Chen X. L., Zhang Y. Z. & Zhou B. C. Characterization, structure and function of linker polypeptides in phycobilisomes of cyanobacteria and red algae: an overview. BBA-Bioenergetics. 1708(2), 133–142 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur S., Agrawal D. & Jajoo A. Photosynthesis: Response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 137, 116–126 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. & Wang G. The enhancement of cyclic electron flow around photosystem I improves the recovery of severely desiccated Porphyra yezoensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). J. Exp. Bot. 63, 4349–4358 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. et al. The physiological links of the increased photosystem II activity in moderately desiccated Porphyra haitanensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) to the cyclic electron flow during desiccation and re-hydration. Photosynth. Res. 116(1), 45–54 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamoi M., Nagaoka M., Yabuta Y. & Shigeoka S. Carbon metabolism in the Calvin cycle. Plant Biotechnol. 22(5), 355–360 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan B. B. Regulation of CO2 assimilation in oxygenic photosynthesis: the ferredoxin/thioredoxin system: perspective on its discovery, present status, and future development. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 288(1), 1–9 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney J. V., Bartlett S. G. & Samuelsson G. Carbonic anhydrases in plants and algae. Plant Cell Environ. 24(2), 141–153 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Dai Z., Xu Y., Ji D. & Xie C. Cloning, expression, and characterization of carbonic anhydrase genes from Pyropia haitanensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 28(2), 1403–1417 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Dynamics of chloroplast proteome in salt-stressed mangrove Kandelia candel (L.) Druce. J. Proteome Res. 12(11), 5124–5136 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker D. H. et al. The tobacco salicylic acid-binding protein 3 (SABP3) is the chloroplast carbonic anhydrase, which exhibits antioxidant activity and plays a role in the hypersensitive defense response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(18), 11640–11645 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Zhang X., Guan Q., Takano T. & Liu S. Expression of a carbonic anhydrase gene is induced by environmental stresses in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnol. Lett. 29(1), 89–94 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Y., Choi Y. H., Lee J. I., Kim I. H. & Nam T. J. Antioxidant activity of oxygen evolving enhancer protein 1 purified from Capsosiphon fulvescens. J. Food Sci. 80(6), H1412–H1417 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Vinocur B., Shoseyov O. & Altman A. Role of plant heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones in the abiotic stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 9(5), 244–252 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Whaibi M. H. Plant heat-shock proteins: a mini review. J. King Saud U-Sci. 23(2), 139–150 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Swindell W. R., Huebner M. & Weber A. P. Transcriptional profiling of Arabidopsis heat shock proteins and transcription factors reveals extensive overlap between heat and non-heat stress response pathways. BMC Genomics. 8, 125 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kültz D. Evolution of the cellular stress proteome: from monophyletic origin to ubiquitous function. J. Exp. Bot. 206(18), 3119–3124 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri M. Z. et al. Characterization of calnexin in soybean roots and hypocotyls under osmotic stress. Phytochemistry. 74, 20–29 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwat M. & Naqvi A. R. Heterologous expression of rice calnexin (OsCNX) confers drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40(9), 5451–5464 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach H., Resnick L. & Brot N. Methionine sulfoxide reductases: history and cellular role in protecting against oxidative damage. BBA-Proteins Proteom. 1703(2), 203–212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locato V., Gadaleta C., De Gara L. & De Pinto M. C. Production of reactive species and modulation of antioxidant network in response to heat shock: a critical balance for cell fate. Plant Cell Environ. 31(11), 1606–1619 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. S. & Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 48(12), 909–930 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi A. et al. Catalase function in plants: a focus on Arabidopsis mutants as stress-mimic models. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 4197–4220 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos C. V. & Rey P. Plant thioredoxins are key actors in the oxidative stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 11(7), 329–334 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. et al. NAD (P) H: quinone oxidoreductase 1: role as a superoxide scavenger. Mol. Pharmacol. 65(5), 1238–1247 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reape T. J., Molony E. M. & McCabe P. F. Programmed cell death in plants: distinguishing between different modes. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 435–444 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantong G. & Gunawardena A. H. Programmed cell death: genes involved in signaling, regulation, and execution in plants and animals. Botany. 93(4), 193–210 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Wituszyńska W. & Karpiński S. Programmed cell death as a response to high light, UV and drought stress in plants. Abiotic Stress - Plant Responses and Applications in Agriculture.(ed. Vahdati K. & Leslie C.) 207–246 (InTech, Rijeka, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S. S., Ali M., Ahmad M. & Siddique K. H. Polyamines: natural and engineered abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 29(3), 300–311 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchoni S. O., Kuhns C., Ditzer A., Kirch H. H. & Bartels D. Over-expression of different aldehyde dehydrogenase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana confers tolerance to abiotic stress and protects plants against lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. Plant Cell Environ. 29(6), 1033–1048 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadražnik T., Hollung K., Egge-Jacobsen W., Meglič V. & Šuštar-Vozlič J. Differential proteomic analysis of drought stress response in leaves of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J. Proteomics. 78, 254–272 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton W. C. The organization and regulation of plant glycolysis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 47(1), 185–214 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akula R. & Ravishankar G. A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 6(11), 1720–1731 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P. et al. Analysis of different strategies adapted by two cassava cultivars in response to drought stress: ensuring survival or continuing growth. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 1477–1488 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Sulfur assimilatory metabolism. The long and smelling road. Plant Physiol. 136(1), 2443–2450 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocito F. F., Lancilli C., Giacomini B. & Sacchi G. A. Sulfur metabolism and cadmium stress in higher plants. Plant Stress. 1(2), 142–156 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. X., Wirtz M., Phua S. Y., Estavillo G. M. & Pogson B. J. Balancing metabolites in drought: the sulfur assimilation conundrum. Trends Plant Sci. 18(1), 18–29 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L. & Zhu J. K. Abiotic stress signal transduction in plants: molecular and genetic perspectives. Physiol. Plant. 112(1), 152–166 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islas-Flores T., Rahman A., Ullah H. & Villanueva M. A. The receptor for activated c kinase in plant signaling: tale of a promiscuous little molecule. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1090 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson J. M., Perera I. Y., Heilmann I., Persson S. & Boss W. F. Inositol signaling and plant growth. Trends Plant Sci. 5(6), 252–258 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnik T. & Vermeer J. E. Osmotic stress-induced phosphoinositide and inositol phosphate signalling in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 33(4), 655–669 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T. C. & Farese R. V. Jr. Lipid droplets and cellular lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 687–714 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V. & Zhu J. K. Epigenetic regulation of stress responses in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12(2), 133–139 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdrakhamanova A., Wang Q. Y., Khokhlova L. & Nick P. Is microtubule disassembly a trigger for cold acclimation? Plant Cell Physiol. 44(7), 676–686 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang N., Xie C. T., Chen C. S., Ji D. H. & Xu Y. Comparison of protein preparation methods of Porphyra haitanensis thalli for two-dimensional electrophoresis (in Chinese). J. Fish. China. 35, 1362–1368 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Usadel B. et al. A guide to using MapMan to visualize and compare omics data in plants: a case study in the crop species, Maize. Plant Cell Environ. 32(9), 1211–1229 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z. H. & Su Z. AgriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W64–70 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.