Abstract

Background

Sapovirus (SaV), a member of the family Caliciviridae, is an etiologic agent of gastroenteritis in humans and pigs. To date, both intra- and inter-genogroup recombinant strains have been reported in many countries except for China. Here, we report an intra-genogroup recombination of porcine SaV identified from a piglet with diarrhea of China.

Methods

A fecal sample from a 15-day-old piglet with diarrhea was collected from Shanghai, China. Common agents of gastroenteritis including porcine circovirus type 2, porcine rotavirus, porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus, porcine SaV, porcine norovirus, and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus were detected by RT-PCR or PCR method. The complete genome of porcine SaV was then determined by RT-PCR method.

Phylogenetic analyses based on the structural region and nonstructural (NS) region were carried out to group this SaV strain, and it was divided into different genotypes based on these two regions. Recombination analysis based on the genomic sequence was further performed to confirm this recombinant event and locate the breakpoint.

Results

All of the agents showed negative results except for SaV. Analysis of the complete genome sequence showed that this strain was 7387 nt long with two ORFs and belonged to SaV GIII. Phylogenetic analyses of the structural region (complete VP1 nucleotide sequences) grouped this strain into GIII-3, whereas of the nonstructural region (RdRp nucleotide sequences) grouped this strain into GIII-2. Recombination analysis based on the genomic sequence confirmed this recombinant event and identified two parental strains that were JJ259 (KT922089, GIII-2) and CH430 (KF204570, GIII-3). The breakpoint located at position 5139 nt of the genome (RdRp-capsid junction region). Etiologic analysis showed the fecal sample was negative with the common agents of gastroenteritis, except for porcine SaV, which suggested that this recombinant strain might lead to this piglet diarrhea.

Conclusions

P2 strain was an intra-genogroup recombinant porcine SaV. To the best of our knowledge, this study would be the first report that intra-genogroup recombination of porcine SaV infection was identified in pig herd in China.

Keywords: Porcine sapovirus, Genome organization, Recombination

Background

Sapovirus (SaV) is the causative agent of gastroenteritis and has been detected in multiple mammalian species and pigs are the predominant host of SaV [1–3]. Based on the complete capsid protein VP1 sequences, SaV now has been divided into 15 genogroups (GI-GXV) and GIII was the predominant one infecting pigs [4]. GIII strains have been further clustered into several genotypes based on the partial VP1 or RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) sequences reported by different researchers [5, 6]. Genomic organization of a common SaV includes two open reading frames (ORF1 and ORF2), whereas in certain genogroups strains were identified an additional ORF (ORF3) [7–9]. ORF1 encodes the predicted viral NS proteins and the major capsid protein VP1, ORF2 encodes the minor capsid protein VP2, and ORF 3 encodes a small basic protein with unknown function [9].

SaV strains with inconsistent grouping between the nonstructural protein-encoding region (including the RdRp region) and the VP1 encoding region have been designated as “recombinant”. Previous studies suggested that the recombination site was at the polymerase-capsid junction [1, 2]. To date, both intra- and inter-genogroup recombinant strains have been reported in humans, however, few porcine recombinant SaV strains have been reported all over the world [10–13]. In particular, no recombinant strain of SaV has been identified either in human or pig in China.

In the present study, we characterized the complete genome of a porcine SaV which might lead to a piglet diarrhea and analyzed the recombination of this strain. Phylogenetic and recombination analysis showed that this strain was an intra-genogroup recombinant, and the breakpoint for this recombination event located at the polymerase-capsid junction within ORF1. This is the first report that intra-genogroup recombination of porcine SaV related with a piglet diarrhea in China.

Methods

Specimens

A fecal sample from a 15-day-old piglet with diarrhea was collected in October, 2015 in Shanghai, China. Bacterial infection was ruled out by the diagnosis of the licensed veterinarian from the pig farm. In order to avoid sample contamination, specimen was obtained directly from the pig anus and disposable materials were used during sampling. Stool sample was freshly collected and immediately converted to 10% (w/v) suspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 7.2-7.4) for further RNA and DNA extraction.

RNA and DNA extraction

Viral RNA/DNA was extracted from 200 μl of fecal supernatant by using the TaKaRa MinBEST Viral RNA/DNA Extraction Kit version 5.0 (TaKaRa, Japan), according to the manual instruction. RNA/DNA was dissolved in 25 μl RNase-free water and reverse transcription was performed immediately.

RT-PCR or PCR

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays with certain primer sets for the detection of porcine common viruses that may cause pig diarrhea including porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2), porcine rotavirus (PRV), porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (PTGV), porcine SaV, porcine norovirus (NoV), and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) were performed as previously described [14–16].

Whole genome amplification

To amplify the genome of this SaV strain, the first strand cDNA was synthetized in 20 μl reaction mixture followed the Thermo Scientific RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit’s (Thermo, USA) introductions with 1 μl random hexamer primer supplied by the kit for the full sequences amplification or 1 μl gene-specific primer QT (Table 1) especially for the 3’ end amplification (3’ RACE method), respectively [17]. Eleven sets of specific primers were designed based on KF204570 to amplify the remaining sequences (Table 1). All the PCR products were purified by OMEGA Gel Kit (OMEGA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions, ligated to the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa, Japan) and then transformed into DH5α competent Escherichia coli cells (Yeasen, China). For each product, three to five colonies were selected and sequenced (Sangon, China) in both directions with the M13+/- universal primers. The consensus sequences were assembled using the Lasergene Software package (version 8) (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI).

Table 1.

Primers for amplifying the complete genome

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5’-3’) | Position | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAVP1F | GTGATCGTGATGGCTAATTGC | 1-21 | JX678943 |

| SAVP1R | GAACTGTTTCAACACTGT | 622-639 | JX678943 |

| SAVP2F | GGGACATGTGGCAGTAC | 533-549 | JX678943 |

| SAVP2R | TTGAAGTAGTCCACTATCCACAT | 1087-1109 | JX678943 |

| SAVP3F | ACTGACAAGTTTGCTGA | 862-878 | JX678943 |

| SAVP3R | GTGTGGGGCAATTGGTGGT | 1660-1678 | JX678943 |

| SAV4FW | TTGAATTGTGACCGGCCAGAG | 1600-1620 | KX688107 |

| SAVP5R | TCATCATACTCATCGTCCCT | 2863-2882 | JX678943 |

| SAVP6F | CTGAACACCCGTGA | 2782-2795 | JX678943 |

| SAVP9R | AGCACAGCCATGGCAAAG | 4551-4568 | JX678943 |

| SAVP10F | CCATAGCCACACTGTGTTCAC | 4427-4447 | JX678943 |

| SAVP10R | TCTTCATCTTCATTGGTGGGAG | 5102-5123 | JX678943 |

| SAVP11F | CCAAGGGCAGTGTTTGAC | 4963-4980 | JX678943 |

| SAVP11R | GGTTGGTACACATAAAGTGCC | 5676-5696 | JX678943 |

| SAVP12F | GATGTTAGGGCGGTGGA | 5620-5636 | JX678943 |

| SAVP12R | AGGTGAAAGTGGTGTCTTCTG | 6674-6694 | JX678943 |

| SAVP13F | CTCGGCACGCACACGGG | 6469-6485 | JX678943 |

| SAVP13R | TGATTGGCAGGTAAATTTG | 6961-6979 | JX678943 |

| SAV14N | GATGGAGTTGGCTAAAGAACA | 6893-6913 | KX688107 |

| QT | CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACGAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | [17] | |

| QO | CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACG | [17] | |

| QI | GAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGC | [17] |

Sequence and recombination analysis

Similarity searches of the sequences were carried out in BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). After a multiple alignment with CLUSTAL W embedded in MEGA 7, the phylogenetic relationship of the strain in the present study and the reference sequences were assessed using MEGA 7. For analysis in MEGA 7, Jukes-cantor (JC) distance was utilized, employing the Neighbor joining (NJ) algorithm [18]. The reliability of different phylogenetic groupings was evaluated by using the bootstrap test (1000 bootstrap replications) available in MEGA 7. The identification of recombinants was performed by using the Recombination Detection Program 4 (RDP 4) (http://darwin.uvigo.es/rdp/rdp.html) [19]. Prototype SaV strains used as references in the analysis with their corresponding GenBank accession numbers, source of origin and genogroups are showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profile of porcine sapovirus isolates used for sequence analyses

| Strain ID | GenBank accession number | Length | Geographic origin | Genogroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VZ | DQ056363 | 1940 bp | Venezuela | GIII |

| YiY1/2006 | EU381231 | 1635 bp | China b | GIII |

| OH-MM280/2003 | AY823308 | 2971 bp | USA | GIII |

| NC-QW270 | AY826426 | 2971 bp | USA | GIII |

| S20 | AB242875 | 1635 bp | Japan | GIII |

| HW20/2007 | HM346629 | 2983 bp | South Korea | GIII |

| DG24/2007 | HM346628 | 3016 bp | South Korea | GIII |

| ah-1/2009 | JX678943 | 7342 bp | China b | GIII |

| Cowden | AF182760 | 7320 bp | USA | GIII |

| LL14 | AY425671 | 7291 bp | USA | GIII |

| JJ259 | KT922089 | 7347 bp | USA | GIII |

| sav1/2008 | FJ387164 | 7558 bp | China b | GIII |

| CH430/2012 | KF204570 | 7371 bp | China b | GIII |

| p2a | KX688107 | 7371 bp | China b | GIII |

| WG194D-1 | KX000383 | 7496 bp | USA | GV |

| TYMPo239 | AB521771 | 3949 bp | Japan | GV |

| TYMPo31 | AB521772 | 3949 bp | Japan | GV |

| OH-JJ674 | KJ508818 | 7198 bp | USA | GVI |

| OH-JJ681 | AY974192 | 7198 bp | USA | GVI |

| RV0042/2011 | KX000384 | 7150 bp | USA | GVII |

| OH-LL26/2002 | AY974195 | 2952 bp | USA | GVII |

| K7 | AB221130 | 7144 bp | Japan | GVII |

| K10 | AB221131 | 2972 bp | Japan | GVII |

| AB23 | FJ498787 | 3000 bp | Canada | GVII |

| DO19/2007 | HM346630 | 2983 bp | South Korea | GVII |

| 2014P2 | DQ359099 | 1626 bp | Brazil | GVII |

| F2-4/2006 | GU230161 | 2935 bp | Canada | GVII |

| F8-9/2006 | GU230162 | 2926 bp | Canada | GVII |

| WGP3/2009 | KC309420 | 2933 bp | USA | GVII |

| WGP247/2009 | KC309421 | 6052 bp | USA | GVII |

| WG194D/2009 | KC309416 | 6654 bp | USA | GVIII |

| WG214D/2009 | KC309419 | 7497 bp | USA | GVIII |

| 06-18p3 | EU221477 | 3094 bp | Italy | GVIII |

| F19-10 | FJ498786 | 3142 bp | Canda | GVIII |

| WG180B | KC309415 | 3111 bp | USA | GVIII |

| WG197C/2009 | KC309417 | 6497 bp | USA | GVIII |

| WG214C | KC309418 | 3695 bp | USA | GIX |

| F16-7 | FJ498788 | 2982 bp | Canada | GIX |

| K8 | AB242873 | 1617 bp | Japan | GX |

| 2053P4 | DQ359100 | 1635 bp | Brazil | GXI |

aThe strain with complete genomic sequence determined in this study

bThe strains which were deposited in GenBank database by Chinese researchers and used in this study were bolded

Results

Result of viruses detection

RT-PCR or PCR were performed to detect the common viruses that may cause pig diarrhea. Result showed that the fecal sample was negative for porcine NoV, PCV 2, PRV, PTGV and PEDV, but was positive for porcine SaV.

Genome organization

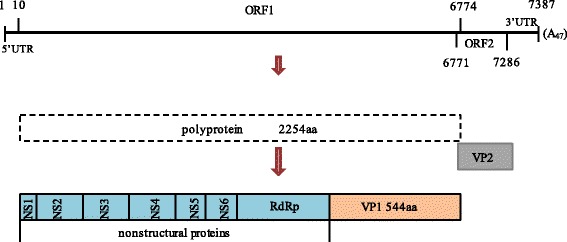

The whole genome of p2 strain was determined by RT-PCR and 3’ RACE method. The entire genome of this porcine SaV strain (named as p2, GenBank no. KX688107) consisted of 7387 nucleotides (nt) including the poly (A) tail with a 9 nt 5’ untranslated region (UTR) and a 54 nt 3’-UTR. Similar to previously reported porcine strains, p2 has two ORFs. ORF1 comprised 6,765 nt (10-6774) encoding a single polyprotein of 2,254 amino acid (aa). ORF2 comprised 516 nt (6771–7286) and contained a 4-nt overlapping region (6771ATGA6774) with the 3′ end of ORF1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of strain p2 genome organization. The full genome of strain p2 is a linear, positive-sense,single-stranded RNA of 7387 bp with a poly (A) tail at the 3’ end. The nucleotides coordinate of 5’ UTR, ORF 1 and ORF 2, and 3’ UTR are indicated on the map. ORF1 encoded a single polyprotein which was subsequently cleaved into seven nonstructural proteins containing the RdRp region and the major capsid protein VP1. ORF2 encoded the minor capsid protein VP2 (171 aa)

Phylogenetic and recombination analysis

P2 shared the highest nucleotide homology (91%) through the entire genome and about 94% in the capsid region with CH430 (GIII-3, GenBank no. KF204570) (a Chinese porcine SaV strain), respectively. However, it shared only 87% identity with strain CH430 in the RdRp region. On the contrary, p2 shared the highest 91% nucleotide identity with an American strain JJ259 (GIII-2, GenBank no. KT922089) in the RdRp region, which was opposite to the general phenomenon observed for caliciviruses that the RdRp region is more conserved than the capsid region. In the previous studies, SaV strains with inconsistent grouping between the nonstructural protein-encoding region (including the RdRp region) and the VP1 encoding region were designated as recombinant. All of these suggested that p2 strain may be a recombinant virus.

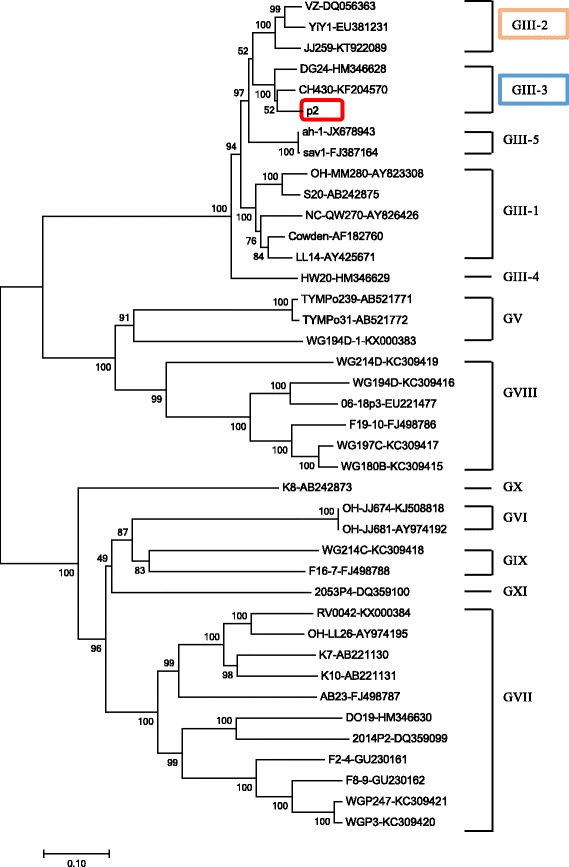

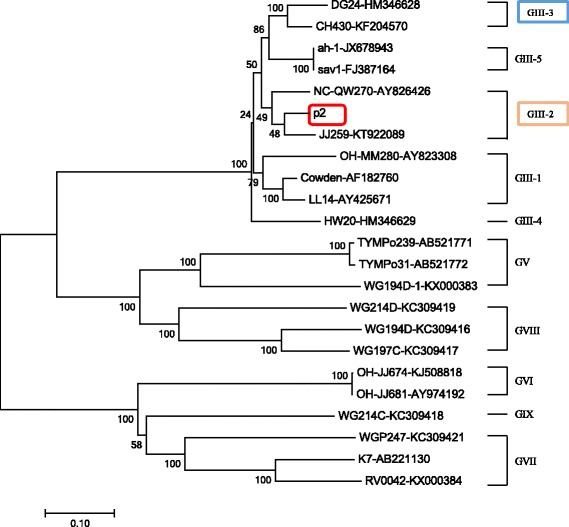

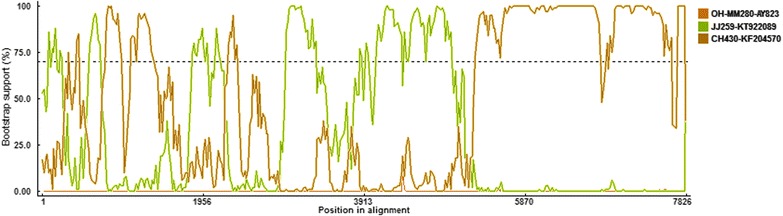

Phylogenetic and recombination analysis were further performed to verify the genotype definition and recombination. Phylogenetic tree based on 42 of the complete VP1 nucleotide sequences was constructed by the NJ method, in which p2 was grouped into GIII-3 clustering with CH430 (Fig. 2). However, phylogenetic analysis based on the 3’ end of RdRp nucleotide sequences gave a different grouping result, in which p2 was grouped into the GIII-2 clustering with JJ259 (Fig. 3). This finding suggested that this strain may be an intra-genogroup recombinant within GIII. To confirm the finding and detect the breakpoint where the recombination event occurred, we performed recombination analysis with p2 as the query sequence, JJ259 and CH430 as the background sequences and OH-MM280 (GIII-1, GenBank no. AY823308) as the outlier sequence using RPD software. Recombination analysis confirmed that the p2 strain was a recombinant and the major and minor parent was JJ259 and CH430, respectively. Moreover, the breakpoint for this recombination event located at position 5139 nt of the genome, which was the polymerase-capsid junction within ORF1 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the complete VP1 nucleotide sequences of 42 SaV strains using MEGA 7. These strains represented all reported 8 genogroups (GIII, GV-GXI) of porcine SaV. GIII strains were grouped into 5 genotypes (GIII-1 – GIII-5). Among those strains, the p2 strain determined in this study was marked with box. Each SaV strain is presented as the following format: strain ID- GenBank accession number

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the 3’ end of RdRp nucleotide sequences (780 bp) of SaV strains. Only 25 of 42 strains had the available sequences of 3’ end of the RdRp region covering the RdRp-capsid junction and GIII strains were grouped into 5 genotypes (GIII-1-GIII-5). The strain p2 reported in this study was indicated in box

Fig. 4.

Identification of recombinant p2 strain based on RDP 4. BOOTSCAN evidence for the recombination origin on the basis of pairwise distance, modeled with a window size 200, step size 25, and 100 Bootstrap replicates

Discussion

SaV causes acute gastroenteritis in humans and animals including pigs, mink, dogs, sea lions, and bats [4, 9, 20]. Porcine SaV and human strains were separated into a different genogroups, however, based on analyses of RdRp or capsid protein genes, porcine SaV that genetically resembled human strains rather than previously recognized porcine strains had been identified [21, 22]. These findings suggested the possibility of a pig reservoir for human strains or vice versa. Meanwhile, recombination as an important survival event for all living creatures, may result in generation of new viruses with unknown pathogenic potential and altered species tropism for both animals and humans [23]. To date, both intra- and inter-genogroup recombinant strains have been reported [11–13, 22–24]. So far the recombinant strain was not found in either human beings or animals of China, although the SaV infections in children and pigs were common in this area [25–27]. Here, we reported a complete genome of a recombinant SaV strain that identified from a piglet with diarrhea in China. Phylogenetic and recombination analysis based on the genomic sequences showed that p2 was an intra-genogroup recombinant within GIII, and the breakpoint located in the RdRp-capsid junction region, which was consistent with most of other SaV recombination events. Previous reports had shown that, in the genome of SaV, recombination mostly occurred at the polymerase-capsid junction region within ORF 1 which was referred as ‘hot spot’ [2, 13]. Chang et al. detected a 2.2 kb RNA in vitro replication assay with the replication complex of SaV Cowden strain extracted from virus-infected cells suggesting that SaV will generate subgenomic RNA during virus replication [8]. Moreover, researchers found that the RdRp-capsid junction region of SaV contained a highly conserved ~20 nucleotide (nt) motif in both genomic and subgenomic RNA molecules which was considered as a transcription start signal [2]. This conserved nucleotide motif may facilitate homologous recombination during co-infection of a cell by different genogroups of virus.

SaV has been detected in a wide range of mammals with potential ability of zoonotic transmission [28–31]. Recombination was considered as a force of evolution which may produce new virus with potentially different pathogenesis and virulence [32]. Moreover, an infectious NoV chimera comprising the distinct biological properties from the parental viruses has been constructed and is infectious in vivo [32, 33]. Therefore, detection and understanding the recombination of SaV is important. In the current study, p2 strain was identified from a pig with diarrhea, in which bacteria and the common enteric viruses that cause pig gastroenteritis were ruled out. This suggested that this recombinant virus may cause this piglet diarrhea under the nature condition. More researches such as experimental infection should be performed in the future to confirm the pathogenicity of this recombinant strain.

Conclusions

This is the first report that an intra-genogroup recombinant porcine SaV infected piglet in China and may lead to the piglet diarrhea. This finding raised our awareness of whether recombination in SaV will increase its virulence.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No.31270186, 31572525 and 31402211); The Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20140578), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2013 M530234; The Ph.D Programs Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (No. 20133227120010); Jiangsu Planned Projects for Postdoctoral Research Funds, (No. 1301142C).

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting the results are included in the article.

Authors' contributions

XGH, QS and JJL conceived the study and designed the experiments. JJL and QS performed the laboratory assays, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- aa

Amino acid

- GIII

Genogroup III

- JC

Jukes-cantor

- NJ

Neighbor joining

- NoV

Norovirus

- nt

Nucleotides

- ORF

Open reading frame

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCV2

Porcine circovirus type 2

- PEDV

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus

- PRV

Porcine rotavirus

- PTGV

Porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SaV

Sapovirus

- UTR

Untranslated region.

Contributor Information

Jingjiao Li, Email: lijingjiao2015SJTU@sjtu.edu.cn.

Quan Shen, Email: shenquanfly@yahoo.com.

Wen Zhang, Email: z0216wen@yahoo.com.

Tingting Zhao, Email: shilohzhao@126.com.

Yi Li, Email: 1164173189@qq.com.

Jing Jiang, Email: jiangjing@shciq.gov.cn.

Xiangqian Yu, Email: Yuxiangqian134@126.com.

Zhibo Guo, Email: boboguo84@hotmail.com.

Li Cui, Email: lcui@sjtu.edu.cn.

Xiuguo Hua, Email: hxg@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Hansman GS, Oka T, Katayama K, Takeda N. Human sapoviruses: genetic diversity, recombination, and classification. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17(2):133–41. doi: 10.1002/rmv.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oka T, Wang Q, Katayama K, Saif LJ. Comprehensive review of human sapoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(1):32–53. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren Z, Kong Y, Wang J, Wang Q, Huang A, Xu H. Etiological study of enteric viruses and the genetic diversity of norovirus, sapovirus, adenovirus, and astrovirus in children with diarrhea in Chongqing, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:412. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oka T, Lu Z, Phan T, Delwart EL, Saif LJ, Wang Q. Genetic Characterization and Classification of Human and Animal Sapoviruses. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dufkova L, Scigalkova I, Moutelikova R, Malenovska H, Prodelalova J. Genetic diversity of porcine sapoviruses, kobuviruses, and astroviruses in asymptomatic pigs: an emerging new sapovirus GIII genotype. Arch Virol. 2013;158(3):549–58. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1528-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu GH, Li RC, Huang ZB, Yang J, Xiao CT, Li J, Li MX, Yan YQ, Yu XL. RT-PCR test for detecting porcine sapovirus in weanling piglets in Hunan Province, China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44(7):1335–9. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farkas T, Zhong WM, Jing Y, Huang PW, Espinosa SM, Martinez N, Morrow AL, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pickering LK, Jiang X. Genetic diversity among sapoviruses. Arch Virol. 2004;149(7):1309–23. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang KO, Sosnovtsev SV, Belliot G, Wang Q, Saif LJ, Green KY. Reverse genetics system for porcine enteric calicivirus, a prototype sapovirus in the Caliciviridae. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1409–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1409-1416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tse H, Chan WM, Li KS, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Discovery and genomic characterization of a novel bat sapovirus with unusual genomic features and phylogenetic position. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansman GS, Takeda N, Oka T, Oseto M, Hedlund KO, Katayama K. Intergenogroup recombination in sapoviruses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(12):1916–20. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dey SK, Mizuguchi M, Okitsu S, Ushijima H. Novel recombinant sapovirus in Bangladesh. Clin Lab. 2011;57(1-2):91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phan TG, Okitsu S, Muller WE, Kohno H, Ushijima H. Novel recombinant sapovirus, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):865–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katayama K, Miyoshi T, Uchino K, Oka T, Tanaka T, Takeda N, Hansman GS. Novel recombinant sapovirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(10):1874–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JS, Song DS, Kim SY, Lyoo KS, Park BK. Detection of porcine circovirus type 2 in feces of pigs with or without enteric disease by polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2003;15(4):369–73. doi: 10.1177/104063870301500412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Huang PW, Zhong WM, Farkas T, Cubitt DW, Matson DO. Design and evaluation of a primer pair that detects both Norwalk- and Sapporo-like caliciviruses by RT-PCR. J Virol Methods. 1999;83(1-2):145–54. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Zhang Q, He C, Zhang L, Li J, Zhang W, Cao W, Lv YG, Liu Z, Zhang JX, Shao ZJ. Recombination and natural selection in hepatitis E virus genotypes. J Med Virol. 2012;84(9):1396–407. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scotto-Lavino E, Du GW, Frohman MA. 3 ' End cDNA amplification using classic RACE. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(6):2742–5. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5(2):150–63. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin D, Rybicki E. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(6):562–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evermann JF, Smith AW, Skilling DE, McKeirnan AJ. Ultrastructure of newly recognized caliciviruses of the dog and mink. Arch Virol. 1983;76(3):257–61. doi: 10.1007/BF01311109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang QH, Han MG, Funk JA, Bowman G, Janies DA, Saif LJ. Genetic diversity and recombination of porcine sapoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(12):5963–72. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.5963-5972.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martella V, Lorusso E, Banyai K, Decaro N, Corrente M, Elia G, Cavalli A, Radogna A, Costantini V, Saif LJ, Lavazza A, Di Trani L, Buonavoglia C. Identification of a porcine calicivirus related genetically to human sapoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(6):1907–13. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00341-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bank-Wolf BR, Konig M, Thiel HJ. Zoonotic aspects of infections with noroviruses and sapoviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140(3-4):204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitamoto N, Oka T, Katayama K, Li TC, Takeda N, Kato Y, Miyoshi T, Tanaka T. Novel monoclonal antibodies broadly reactive to human recombinant sapovirus-like particles. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56(11):760–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Q, Zhang W, Yang SX, Chen Y, Ning HB, Shan TL, Liu JF, Yang ZB, Cui L, Zhu JG, Hua XG. Molecular detection and prevalence of porcine caliciviruses in eastern China from 2008 to 2009. Arch Virol. 2009;154(10):1625–30. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Shen Q, Hua XG, Cui L, Liu JF, Yang SX. The first Chinese porcine sapovirus strain that contributed to an outbreak of gastroenteritis in piglets. J Virol. 2008;82(16):8239–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao ZY, Li XT, Yan HQ, Li WH, Jia L, Hu L, Hu H, Liu BW, Li J, Wang QY. Human calicivirus occurrence among outpatients with diarrhea in Beijing, China, between April 2011 and March 2013. J Med Virol. 2015;87(12):2040–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergallo M, Galliano I, Montanari P, Brusin MR, Finotti S, Paderi G, Gabiano C. Development of a quantitative real-time PCR assay for sapovirus in children under 5-years-old in Regina Margherita Hospital of Turin, Italy. Can J Microbiol. 2017;63:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Li L, Shan T, Wang C, Cote C, Kolman J, Onions D, Gulland FM, Delwart E. The fecal viral flora of California sea lions. J Virol. 2011;85(19):9909–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oka T, Yamamoto M, Katayama K, Hansman GS, Ogawa S, Miyamura T, Takeda N. Identification of the cleavage sites of sapovirus open reading frame 1 polyprotein. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(Pt 11):3329–38. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura K, Saga Y, Iwai M, Obara M, Horimoto E, Hasegawa S, Kurata T, Okumura H, Nagoshi M, Takizawa T. Frequent detection of noroviruses and sapoviruses in swine and high genetic diversity of porcine sapovirus in Japan during Fiscal Year 2008. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(4):1215–22. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02130-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathijs E, Muylkens B, Mauroy A, Ziant D, Delwiche T, Thiry E. Experimental evidence of recombination in murine noroviruses. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 11):2723–33. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.024109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathijs E, Oliveira-Filho EF, Dal Pozzo F, Mauroy A, Thiry D, Massart F, Saegerman C, Thiry E. Infectivity of a recombinant murine norovirus (RecMNV) in Balb/cByJ mice. Vet Microbiol. 2016;192:118–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the results are included in the article.