Abstract

Childhood emotional abuse has been linked to problematic alcohol use in later life but there is a paucity of empirically based knowledge about the developmental pathways linking emotional abuse and alcohol use in young adulthood. Using a community sample of young individuals aged 18–25 (N = 268; female 52%), we performed structural equation modeling to investigate whether emotional abuse influences alcohol use through urgent personality trait and to determine pathways for these effects in a multivariate context. We also examined variations in these pathways by four different alcohol use outcomes including frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use disorders (AUD). The present study found that emotional abuse was related to urgency, which in turn influenced four types of alcohol use. Urgency may play a significant role in linking childhood maltreatment to alcohol use in young adulthood.

Keywords: Emotional abuse, Child maltreatment, Alcohol use and misuse, Binge drinking, Alcohol use disorder, Young adults

Childhood emotional abuse is a more hidden form of childhood maltreatment, which can be characterized as degrading, terrorizing, isolating, denying/rejecting, and exploitive/corruptive caregiving (Behl, Conyngham, & May, 2003; Brassard & Donovan, 2006; Trickett, Mennen, Kim, & Sang, 2009; Wekerle et al., 2009). According to the 2010 Federal report of child maltreatment statistics, 8% of the total 688,251 reported cases of maltreatment were emotional abuse (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Prior research suggested that the incidence of emotional abuse is at least more prevalent than is reported in the national statistics. For example, previous empirical studies suggested that prevalence rates of emotional abuse ranges from 12% to 48%, varying between samples studied (Hamarman, Pope, & Czaja, 2002; Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison, 1996; Spertus, Yehuda, Wong, Halligan, & Seremetis, 2003; Trickett et al., 2009). Emotional abuse itself is associated with a myriad of neuropsychosocial problems including disturbance in brain limbic systems, dissociative symptoms, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, hostility and delinquency (Braver, Bumberry, Green, & Rawson, 1992; Briere & Runtz, 1990; McGee, Wolfe, & Wilson, 1997; Mersky & Reynolds, 2007; Teicher, Samson, Polcari, & McGreenery, 2006).

Most forms of childhood maltreatment have been found to be subsequently associated with later harmful alcohol use habits (Dube et al., 2006; Gilbert et al., 2009), even though current evidence is not sufficient to support this relationship among adult males who had been victims of childhood maltreatment (Langeland & Hartgers, 1998; Widom & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 2001). A few existing studies analyzing the specific effects of emotional abuse on later alcohol use have found that childhood emotional abuse increases an individual’s risk for alcohol problems in adulthood (Chamberland, Fallon, Black, & Trocme, 2011; Moran, Vuchinich, & Hall, 2004; Widom & White, 1997). In a retrospective study of 8,417 adult health maintenance organization (HMO) members, Dube et al. (2006) found that emotional abuse was related to ever drinking alcohol and early onset of alcohol use (≤14 years), after the adjustment for demographics and education. Furthermore, emotional abuse was associated with adolescent drinking frequency in a sample of 2,164 students in the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades, controlling for age, gender, and family configuration (Moran et al., 2004). These studies provide insight into the possible significant effects of emotional abuse on alcohol use during young adulthood.

While empirical evidence supporting this relationship is emerging, there is a critical gap in our understanding of the mechanisms that explain the associations between emotional abuse and alcohol use in young adulthood. Common theoretical models proposed to explain why victims of child maltreatment are at increased risk for later hazardous drinking come from developmental psychopathology. At the heart of a developmental psychopathology perspective is an assumption that inappropriate development at one stage has a ripple effect on subsequent development (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995). For example, childhood maltreatment might lead to the development of less adaptive personality traits, which in turn increases an individual’s risk for alcohol problems in adulthood. Indeed, a substantial body of literature suggested that experience of childhood maltreatment predicts the development of urgent personality trait (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2007; Johnson et al., 2001; Kim, Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Manly, 2009; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 2004). Alcohol research has also given increasing attention to the role of urgent personality traits for onset and escalation of alcohol use (Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1988; Lejuez et al., 2010; Sher & Trull, 1994). Urgent personality trait, also called urgency, is often defined as the propensity to act on impulses, often under the influence of distress (Simons, Dvorak, Batien, & Wray, 2010; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Since numerous studies have found that maltreated children were more prone to negative emotionality and showed greater difficulties in dealing with psychological distress than non-maltreated children, urgency might play an important role in linking child maltreatment and later alcohol use (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Leslie et al., 2003; Shields, Cicchetti, & Ryan, 1994; Trickett, Negriff, Ji, & Peckins, 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that victims of child maltreatment might be more inclined to alcohol problems in young adult due to failure to inhibit behavior under the influence of psychological distress. The present study examined the role of urgent personality trait in linking childhood emotional abuse to alcohol problems in young adulthood.

The developmental literature suggests that exposure to childhood maltreatment interferes with normative personality development (Johnson, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, & Bernstein, 1999; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 2004). Since the nurturing roles and protective function of the child’s familial and social environment is critical in personality development, for emotionally abused children who often live in hostile and threatening caretaking environments, many positive personality traits are difficult to develop (Cohen, Chen, Crawford, Brook, & Gordon, 2007; Johnson, Smailes, Cohen, Brown, & Bernstein, 2000; Laporte, Paris, Guttman, & Russell, 2011). Specifically, in a longitudinal community sample of 793 children, Johnson et al. (2001) found that emotional abuse, particularly verbal abuse, is associated with borderline, narcissistic, obsessive–compulsive, and paranoid personality disorders during young adulthood. Further, Rogosch and Cicchetti (2004) examined the effects of child maltreatment on the Five-Factor personality dimensions (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience). In the three-year longitudinal analysis with a sample of 211 children, maltreated children appeared to have personality traits that might be best described as antagonistic, less trustworthy, and highly urgent. Thus, it is possible that emotionally abused children are susceptible to the development of an urgent personality trait.

Although urgency is one of the least-studied characteristics of impulsive personality (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), a few studies have revealed an association between elevated levels of urgency and alcohol use during young adulthood (Fischer, Anderson, & Smith, 2004; Whiteside & Lynam, 2009). For example, Whiteside and Lynam (2009) have found evidence of binge drinking and alcohol use disorders (AUD) among urgent individuals, while Fischer et al. (2004) discovered positive associations between urgency and alcohol-related problems. However, the association between urgency and alcohol use frequency has been mixed (Magid & Colder, 2007; Miller, Flory, Lynam, & Leukefeld, 2003; Shin, Hong, & Jeon, 2012). There has been evidence of both no association and a positive association between urgency levels and frequency of alcohol use. In one study investigating a sample of 267 undergraduate students from a large university setting (52% female, ages 18–26), urgency levels were not found to be associated with alcohol use frequency, but were related to alcohol-related problems (Magid & Colder, 2007). In a study by Cyders et al. (2009) investigating a sample of 293 first-year university students (75% female, average age 18.2 years), an association was found between urgency and drinking frequency, quantity, and alcohol-related problems (Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009). Inconsistent findings regarding the relation between urgency and alcohol use behaviors may be due to the fact that urgency relates to only certain stages of alcohol use or severe drinking behaviors (e.g., binge drinking). For this reason, examination of the pathways among emotional abuse, urgency and alcohol use needs to consider the heterogeneity of alcohol use behaviors including frequency of alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, binge drinking, and AUD.

Emotional abuse often occurs in conjunction with other forms of maltreatment. For example, a large majority (62–95%) of children who had been neglected and physically abused were also found to have experienced emotional abuse (Braver et al., 1992; Claussen & Crittenden, 1991; Higgins & McCabe, 2001; Trickett et al., 2009). Since risk factors are likely to cluster in the same individuals (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998), accounting for other forms of maltreatment experienced by a child may help researchers address the unique contribution of emotional abuse on alcohol use. The present study controlled for three subtypes of maltreatment including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, which allowed for a more stringent evaluation of the role of emotional abuse in alcohol use during young adulthood.

While the primary focus of the present study is on the role of emotional abuse and urgency, alcohol use is related to other individual and family contexts such as psychological distress, parental alcoholism, and peer alcohol use. Research has indicated that psychological distress operates as a risk factor for alcohol use among young adults (Abraham & Fava, 1999; Marmorstein, 2010; Merline, Jager, & Schulenberg, 2008). Since urgency, by definition, encompasses a repeated pattern of impulsive behaviors under the influence of psychological distress, adding psychological distress in model testing is particularly important in the current study. In addition, we included measures of parental alcoholism and peer alcohol use in model testing to adjust for potential genetic and social influences on alcohol use among young adults. The relationship between emotional abuse and alcohol use is undoubtedly complex, and is probably influenced by a large number of factors. For studying pathways in the relation of emotional abuse to alcohol use in young adulthood, the present study examined the role of urgency in four types of alcohol use including frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking, alcohol-related problems and AUD, controlling for demographics, psychological distress, parental alcoholism, and peer alcohol use. The hypothesis of our study is that emotional abuse and urgency will be positively associated with all types of alcohol behaviors including drink frequency, bring drinking, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol dependence, and that urgency will mediate these associations between emotional abuse and alcohol drinking outcomes.

Method

Procedures and Participants

The participants were recruited from the community using advertisements placed around the local community, seeking healthy young adults (ages 18–25), who are interested in a “study about childhood, family, and physical and mental health.” Participant eligibility was confirmed through an online screening survey that assessed participant age and health. Respondents were excluded if they were not between 18 and 25 years of age or rated their health as either bad or very bad. Data for the present study were collected from 268 young people (mean age = 21.9 years; SD = 2.1 years; range 18–25). Slightly more than half were female (51.9%); 57.5% were enrolled in college; and the majority of participants were White (64.6%). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Data were collected by trained interviewers through an hour-long, structured, face-to-face interview. After complete description of the study to participants, written informed consent was obtained. The study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 268).

| Range | Mean (SD)* or % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age* | 18–25 | 21.9 (2.1) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48.1 (129) | |

| Female | 51.9 (139) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 64.6 (173) | |

| Black | 11.6 (31) | |

| Hispanic | 5.6 (15) | |

| Asian | 8.6 (23) | |

| Other | 9.7 (26) | |

| Urgency* | 13–53 | 27.2 (9.3) |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Monthly frequency* | 0–31 | 8.0 (6.0) |

| Past year binge-drinking | ||

| Yes | 41 (110) | |

| Alcohol-related problem* | 0–59 | 9.5 (10.7) |

| AUD – 12-month | ||

| Yes | 28.7 (77) | |

| Peer alcohol use | ||

| None | 6.7 (18) | |

| One | 12.7 (34) | |

| Less than half | 11.2 (30) | |

| More than half | 23.1 (62) | |

| Almost all | 46.3 (124) | |

| Parental alcoholism* | 0–6 | 1.1 (1.9) |

| Psychological distress* | 33–78 | 47.0 (11.0) |

| Childhood maltreatment | ||

| Emotional abuse | ||

| Yes | 25.7 (69) | |

| Physical abuse | ||

| Yes | 18.7 (50) | |

| Sexual abuse | ||

| Yes | 7.1 (19) | |

| Emotional/physical neglect | ||

| Yes | 28.0 (75) | |

Mean values (standard deviations). All other measures reported in proportion (%). Valid percentages are reported.

Measures

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse and other subtypes of child maltreatment including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, was carefully evaluated using a computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) method of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 1994; Fink et al., 1995), which has been found to be useful in eliciting retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment from young adults (Everson et al., 2008). The CTQ used four severity categories: None to Minimal, Low to Moderate, Moderate to Severe, and Severe to Extreme. A participant having a score of at least moderate to severe was considered positive for the specific type of maltreatment in the present study. The CTQ has shown adequate reliability with internal consistency reliability coefficients ranging from .73 to .92, and validity supported by significant associations of the CTQ with official records including court and social service agency records (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997; Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Internal consistency reliability coefficient for emotional abuse in our sample was .88.

Urgency

Urgency was assessed using a negative urgency subscale of the Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking (UPPS) Impulsive Behavior scale (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The Urgency subscale consists of 11 items (e.g., when I feel bad, I will often do things I later regret in order to make myself feel better now). Many psychometric studies have reported its good reliability and validity (Magid & Colder, 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). High scores on urgency indicate more urgent personality traits. Internal consistency reliability coefficient for urgency in our sample was .88.

Alcohol Use

Frequency of alcohol use was measured with the question “in the past 12 months, on how many days did you drink alcohol per month?” Similarly, the frequency of past-year binge drinking was determined through the question “over the past 12 months, on how many days did you drink five (or four) or more drinks in a row?” (1 = every day, 2 = 3–5 days a week, 3 = 1 or 2 days a week, 4 = 2 or 3 days a month, 5 = once a month or less, 6 = 1 or 2 days in the past year, 7 = never). Subjects were classified as having participated in binge drinking if males consumed five or more drinks in a row and females four or more drinks in a row at least 2–3 days per month in the past 12 months (Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994). Further, the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) was utilized to measure alcohol-related problems in the past 12 months (White & Labouvie, 1989) whereas alcohol use disorders (AUDs), based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV), were assessed through the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) alcohol section (Cottler et al., 1991; Ustun et al., 1997). Internal consistency reliability coefficient for the RAPI for the current sample was .90.

Psychological Distress, Peer Alcohol Use, and Parental Alcoholism

Psychological distress was measured via the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 1993). Further, peer alcohol use was measured through questions addressing the number of subjects’ close friends who drink alcohol once a week or more. Finally, parental alcoholism was measured using the 6-item Children of Alcoholics Screening Test (CAST-6; Hodgins et al., 1993). Internal consistencies reliability coefficients for the BSI 18 and CAST-6 for our study sample were .93 and .92, respectively.

Results

Data Analysis

The measurement structure of urgency was tested by performing confirmatory factor analyses. Since the Urgency scale has 11 individual items, we created three parcels (i.e., groups) of items and used them as indicators for urgency. As combinations of items, a parcel of items provides better reliability and more scale points than multiple individual items, which reduced risk of spurious correlations among items and improved normal distribution approximation of latent construct indicators (Smith et al., 2007; Zapolski, Cyders, & Smith, 2009). We used the measurement model for urgency in further analyses. Next, structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses were used to investigate whether emotional abuse influences alcohol use through the personality trait of urgency and to determine pathways for these effects in a multivariate context. Mplus 6.11 was used to fit the structural models of emotional abuse, urgency and four types of alcohol use behaviors in separate models, controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, psychological distress, parental alcoholism, and peer alcohol use. Four separate SEMs specified the direct effects of emotional abuse on alcohol use as well as indirect effects of emotional abuse via urgency. The indirect effects equal the product of the direct effects involved (for example, multiplying the X to Z and Z to Y paths equals the X to Z to Y indirect effect). For all measurement and structural models of the analyses, a maximum likelihood estimator for a continuous variable and a weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted estimator (WLSMV) for a dichotomous variable were used to estimate covariance structure among measures. SEM models were assessed by inspecting the statistical significance of the following three statistics: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Rates of Emotional Abuse and Alcohol Use

Among the four types of childhood maltreatment, emotional abuse and neglect were most prevalent: 25.7% reported emotional abuse (n = 69) and 28% neglect (n = 75; Table 1). The average monthly frequency of alcohol use was approximately 8 days. A little less than half (41%; n = 110) engaged in binge drinking in the past 12 months, with approximately 28.7% having AUD (n = 77). With regard to peer alcohol use, 46.3% reported “almost all” friends and 23.1% reported “more than half” drank alcohol at least once a week.

Structural Equation Modeling Analyses for Four Types of Alcohol Use

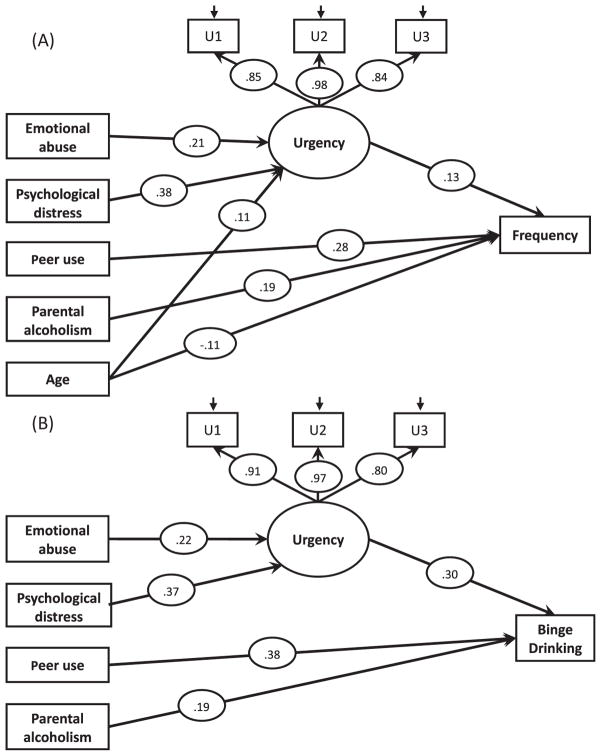

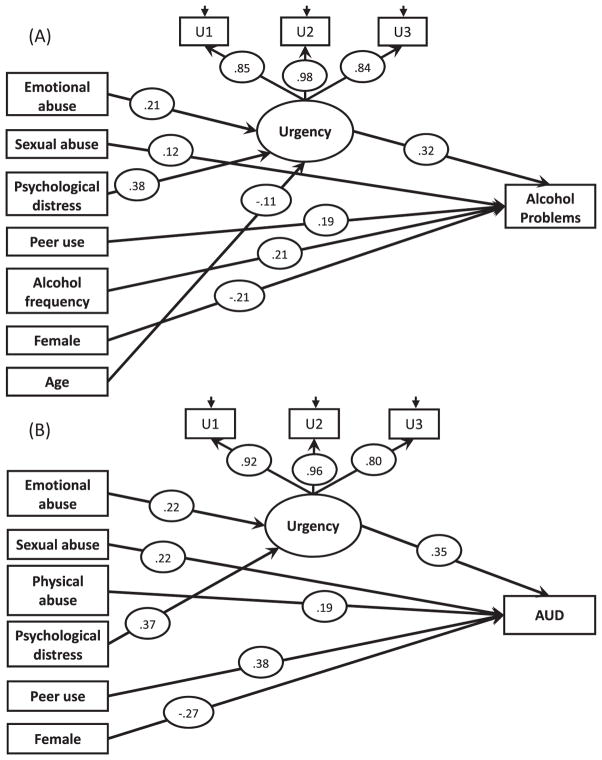

We examined four separate structural models where measures of emotional abuse served as exogenous variables whereas urgency and alcohol use were specified as endogenous variables. Pathways were specified from emotional abuse to urgency and from urgency to alcohol use. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, other types of childhood maltreatment (i.e., neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse), psychological distress, parental and peer alcohol use, and frequency of alcohol use (for alcohol-related problems model only) were entered into the models as covariates. The final models are presented in Fig. 1 for frequency of alcohol use and binge drinking and Fig. 2 for alcohol-related problems and AUD.

Fig. 1.

Structural model for emotional abuse, urgency, and alcohol use. (A) Frequency of alcohol use. (B) Binge drinking. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, and circled values are standardized coefficients. Coefficients are significant at p < .05.

Fig. 2.

Structural model for emotional abuse, urgency, and alcohol use. (A) Alcohol-related problems. (B) AUD. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, and circled values are standardized coefficients. Coefficients are significant at p < .05.

The following indices were obtained in the model for frequency of alcohol use (Fig. 1A), which showed a reasonable fit to the data: χ2(20, N = 268) = 37.82, CFI = .98, TLI = .95, and RMSEA = .06. Emotional abuse had a path to urgency (β = .21) whereas urgency had a path to frequency of alcohol use (β = .13). Emotional abuse had no direct path to frequency of alcohol use. A test of indirect effect of emotional abuse on frequency of alcohol use via urgency also indicated no significant indirect effect. Next, the structural model for binge drinking also showed an adequate fit to the data (Fig. 1B): χ2(20, N = 268) = 25.84, CFI = .98, TLI = .96, and RMSEA = .03. Emotional abuse had a path to higher levels of urgency (β = .22), which in turn had a path to binge drinking (β = .30). Emotional abuse had no direct path to binge drinking. Results for indirect effects showed that emotional abuse had significant indirect effects on binge drinking through urgency (β = .07). Furthermore, the final model for alcohol-related problems fit the data well with the following indices (Fig. 2A): χ2(23, N = 268) = 42.15, CFI = .98, TLI = .95, and RMSEA = .06. Emotional abuse had a path to urgency (β = .21), which then had a direct path to alcohol-related problems (β = .32). Given that emotional abuse had no direct path to alcohol-related problems, a test of indirect paths was conducted and found the significant indirect effect of emotional abuse on alcohol-related problems via urgency (β = .07). Finally, for our data, the following indices were obtained in the structural model for AUD (Fig. 2B): χ2(20, N = 268) = 27.67, CFI = .97, TLI = .94, and RMSEA = .04. Emotional abuse had a path to urgency (β = .22) whereas urgency had a path to AUD (β = .35). Emotional abuse had no direct path to AUD, yet had a significant indirect effect on AUD via urgency (β = .08).

Discussion

Personality traits may play a significant role in mediating the effects of childhood emotional abuse on alcohol use in later life stages. The present study examined the relationships among emotional abuse, urgency, and four types of alcohol use including frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking, alcohol-related problems, and AUD. In specific, we explored whether the relationship between emotional abuse and alcohol use in young adulthood could be attributable to the personality trait of urgency. Our primary findings indicated that emotional abuse is associated with binge drinking, alcohol-related problems and AUD, and that urgency mediates these associations, controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, other types of childhood maltreatment, psychological distress, parental alcoholism, and peer alcohol use.

Since lack of societal consensus exists in defining and classifying emotional abuse, it has received little attention as a specific form of childhood maltreatment (Trickett et al., 2009). Thus, despite growing literature on the effects of other forms of maltreatment such as sexual abuse on subsequent alcohol use, few studies have examined whether emotional abuse individually or in conjunction with other types of maltreatment influences hazardous drinking in young adulthood (Moran et al., 2004). Controlling for other types of maltreatment, the present study found that emotional abuse is indirectly related to alcohol use in young adulthood. Emotional abuse may manifest in multiple forms, including spurning, terrorizing, isolating, and exploiting (Brassard & Donovan, 2006; Trickett et al., 2009). A recent study found that terrorizing was associated with anxiety and somatic concerns whereas ignoring was related to depression and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD; Allen, 2008). Future studies of emotional abuse and alcohol use should consider the heterogeneous nature of emotional abuse and examine whether distinct types of emotional abuse are associated with different alcohol use outcomes in young adulthood.

Young adults with a history of childhood emotional abuse reported a higher level of urgency in the present study. Personality derives from the nurturing roles and protective function of the child’s familial and social environment (Caspi & Shiner, 2006). Thus, the roles of socializing agents such as parents or caregivers are critical for optimal personality development. For children exposed to childhood emotional abuse, the development of favorable interpersonal relationships and normative personality is often hampered by parental verbal aggression, negative interpersonal communication, and exploitative caregiving behaviors.

We also found that urgency mediates the relationship between emotional abuse and three alcohol behaviors including binge drinking, experiencing alcohol-related problems and AUD. Urgency is a motivationally driven, adverse response to psychological distress (Cyders & Smith, 2008). There is growing evidence that emotional abuse was more strongly related to psychological distresses, including anxiety and depression, than physical abuse and sexual abuse (Gibb et al., 2001; Kim & Cicchetti, 2006; McGee et al., 1997; Teicher et al., 2006). Emotionally abused children may be prone to alcohol problems in part because they are unlikely to inhibit behavior under the influence of psychological distress. An inability to control rapid or unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli in the face of intense negative affect is a textbook definition of the urgent personality trait (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001).

Further, the present study suggests that urgency may play distinctive roles in linking emotional abuse to different alcohol use outcomes in young adulthood. We found that urgency was not related to the emotional-abuse-to-drinking-frequency link, but mediated the relationships between emotional abuse and the escalation of alcohol use and development of AUD. The urgency trait is one facet of personality characteristics associated with impulsive behavior. Urgency differs from other impulsive personality traits such as sensation seeking and delayed reward discounting in that it emphasizes negative reinforcement; the individual acts impulsively to avoid distress or escape from negative emotionality. Urgent people with a history of childhood emotional abuse might engage in negative reinforcement-driven binge drinking to avoid negative emotions. Thus, once they experience the negative reinforcement of temporary relief from their distress by drinking heavily, it increases their likelihood to become involved in binge drinking in response to their future distresses, and ultimately to develop pathological drinking habits and AUD. Further, an explanation of the findings regarding alcohol-related problems may be also due to the nature of urgent personality. Urgent people who experienced emotional abuse in childhood may attempt to cope through unhealthy methods, such as heavy drinking, leading to lower self-regulation and increased alcohol-related problems (Magid & Colder, 2007). More specifically, under situations of distress, urgent individuals may feel especially compelled to use alcohol hastily and fail to control their behaviors when intoxicated. Therefore, for emotionally abused children who later develop the urgent personality trait, additive effects of urgent personality and alcohol-induced disinhibition might increase their propensities to engage in alcohol-related problems when they drink.

The results of the current study suggest that urgent personality trait would be potentially useful targets to prevent problematic alcohol use among young people who have exposure to childhood emotional abuse. Intervention and prevention efforts aiming at reducing urgent responses and promoting individual self-control may highly effective in reducing hazardous drinking, especially for impulsive young adults with previous exposure to emotional abuse. Targeted interventions based on personality traits have a theoretical rationale, and alcohol intervention paradigms improving personality traits have been tested to be effective in reducing alcohol use among young people (Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2011; Conrod, Castellanos, & Mackie, 2008; Conrod, Stewart, Comeau, & Maclean, 2006). In sum, the current findings may indicate that treatment of alcohol problems among individuals with a history of emotional abuse may be most successful when focused on urgent personality trait.

Limitations

The present study included a number of strengths such as comprehensive assessment of emotional abuse and alcohol use outcomes, and inclusion of both individual- and environmental-level influences (e.g., parental and peer alcohol use) on alcohol use in young adulthood. It is also important to note some of the limitations of the current study. First, because of the cross-sectional nature of the data, the present study provided no insight into temporal directionality among emotional abuse, urgency, and alcohol use. While we hypothesized the pathways from emotional abuse to alcohol use via urgency, there are other legitimate ways to interpret the data. For example, recent studies have found that alcohol use during young adulthood might influence changes in personality traits over time (Littlefield, Verges, Wood, & Sher, 2012; Quinn, Stappenbeck, & Fromme, 2011). Thus, urgency might be the developmental outcome of alcohol use as well as the predictor of it. Second, since emotional abuse-related data and alcohol use data were self-reported, they are subject to certain limitations including recall bias, social desirability, and response acquiescence. While retrospective self-report measures of childhood maltreatment are widely used in the existing studies examining the effects of early maltreatment on young adult outcomes (Milner et al., 2010; Scher et al., 2004; Teicher et al., 2006), it is also possible that young adults who currently involve in hazardous drinking or have a relatively high degree of psychological distress may attribute their current addictive behaviors to adverse childhood events such as emotional abuse.

Conclusion

Emotional abuse, while frequent, was seldom the focus of addiction research that investigated the etiology of alcohol use among child maltreatment victims. The present study highlighted the mediating role of urgent personality trait in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and alcohol use during young adulthood. Future research is warranted to explore how other characteristics of emotional abuse including subtype, developmental timing, frequency, and severity relate to alcohol use and to prospectively examine the developmental processes linking emotional abuse to alcohol use in young adulthood.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from NIDA DA030884 (Shin) and the AMBRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research (Shin). The Foundation had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Abraham HD, Fava M. Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B. An analysis of the impact of diverse forms of childhood psychological maltreatment on emotional adjustment in early adulthood. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13(3):307–312. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl LE, Conyngham HA, May PF. Trends in child maltreatment literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. 1994 doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace, Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brassard MR, Donovan KL. Defining psychological maltreatment. In: Freerick MM, Knutson JF, Trickett PK, Flanzer SM, editors. Child abuse and neglect: Definitions, classifications, and a framework for research. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookers Publishing Co., Inc; 2006. pp. 151–197. [Google Scholar]

- Braver M, Bumberry J, Green K, Rawson R. Childhood abuse and current psychological functioning in a university counseling center population. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1992;39(2):252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Runtz M. Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14(3):357–364. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90007-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Shiner RL. Personality development. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 300–365. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland C, Fallon B, Black T, Trocme N. Emotional maltreatment in Canada: Prevalence, reporting and child welfare responses (CIS2) Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35:841–854. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Personality, adrenal steroid hormones, and resilience in maltreated children: A multilevel perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):787–809. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen AH, Crittenden PM. Physical and psychological maltreatment: Relations among types of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1991;15(1–2):5–18. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12(4):494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Chen H, Crawford TN, Brook JS, Gordon K. Personality disorders in early adolescence and the development of later substance use disorders in the general population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S71–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C. Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(3):296–306. doi: 10.1037/a0022997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos N, Mackie C. Personality targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Comeau N, Maclean AM. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting personality risk factors for youth alcohol misuse. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(4):550–563. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Grant BF, Blaine J, Towle LH, Wittchen HU, Sartorius N. The CIDI-core substance abuse and dependence questions: Cross-cultural and nosological issues. The WHO/ADAMHA Field Trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;159:653–658. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134(6):807. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory. Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. 4. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(4):1–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson MD, Smith JB, Hussey JM, English D, Litrownik AJ, Dubowitz H, Runyan DK. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood abuse and child protective service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13(1):14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink LA, Bernstein D, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M. Initial reliability and validity of the Childhood Trauma Interview: A new multidimensional measure of childhood interpersonal trauma. 1995 doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Anderson K, Smith G. Coping with distress by eating or drinking: Role of trait urgency and expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(3):269–274. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Rose DT, Whitehouse WG, Donovan P, Hogan ME, Cronholm J, Tierney S. History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25(4):425–446. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamarman S, Pope KH, Czaja SJ. Emotional abuse in children: Variations in legal definitions and rates across the United States. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7(4):303–311. doi: 10.1177/107755902237261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:547–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, Maticka-Tyndale E, el-Guebaly N, West M. The CAST-6: Development of a short-form of the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18(3):337–345. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes EM, Skodol AE, Brown J, Oldham JM. Childhood verbal abuse and risk for personality disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42(1):16–23. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Smailes EM, Cohen P, Brown J, Bernstein DP. Associations between four types of childhood neglect and personality disorder symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood: Findings of a community-based longitudinal study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14(2):171–187. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2006;77(3):624–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):706–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D, Rogosch F, Manly JT. Child maltreatment and trajectories of personality and behavioral functioning: Implications for the development of personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(03):889–912. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeland W, Hartgers C. Child sexual and physical abuse and alcoholism: A review. Journal of the Studies of Alcohol. 1998;59:336–348. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte L, Paris J, Guttman H, Russell J. Psychopathology, childhood trauma, and personality traits in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and their sisters. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25(4):448–462. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Magidson JF, Mitchell SH, Sinha R, Stevens MC, De Wit H. Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(8):1334–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J, Rolls JA, Wood PA, Kelleher KJ. Comprehensive assessments for children entering foster care: A national perspective. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 Pt 1):134–142. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Verges A, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Transactional models between personality and alcohol involvement: A further examination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1037/a0026912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(7):1927–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR. Longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems: The influence of comorbid delinquent behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(6):564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychology. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Wolfe DA, Wilson SK. Multiple maltreatment experiences and adolescent behavior problems: Adolescents’ perspectives. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:131–149. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: Stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103:84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and violent delinquency: Disentangling main effects and subgroup effects. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):246–258. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(8):1403–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Milner JS, Thomsen CJ, Crouch JL, Rabenhorst MM, Martens PM, Dyslin CW, Merrill LL. Do trauma symptoms mediate the relationship between childhood physical abuse and adult child abuse risk? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(5):332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Vuchinich S, Hall NK. Associations between types of maltreatment and substance use during adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen P, Martin J, Anderson J, Romans S, Herbison G. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: A community study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(1):7–21. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Stappenbeck CA, Fromme K. Collegiate heavy drinking prospectively predicts change in sensation seeking and impulsivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(3):543–556. doi: 10.1037/a0023159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosch F, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment and emergent personality organization: Perspectives from the five-factor model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(2):123–145. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019766.47625.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Forde DR, McQuaid JR, Stein MB. Prevalence and demographic correlates of childhood maltreatment in an adult community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields AM, Cicchetti D, Ryan RM. The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and social competence among maltreated school-age children. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6(01):57–75. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S, Hong H, Jeon S. Personality and alcohol use: The role of impulsivity. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(12):1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14(2):155. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus IL, Yehuda R, Wong CM, Halligan S, Seremetis SV. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect as predictors of psychological and physical symptoms in women presenting to a primary care practice. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(11):1247–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Mennen FE, Kim K, Sang J. Emotional abuse in a sample of multiply maltreated, urban young adolescents: Issues of definition and identification. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2009;33(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Negriff S, Ji J, Peckins M. Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Development. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2010. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ustün B, Compton W, Mager D, Babor T, Baiyewu O, Chatterji S, Cottler L, Göğüş A, Mavreas V, Peters L, Pull C, Saunders J, Smeets R, Stipec MR, Vrasti R, Hasin D, Room R, Van den Brink W, Regier D, Blaine J, Grant BF, Sartorius N. WHO Study on the reliability and validity of the alcohol and drug use disorder instruments: Overview of methods and results. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(21):1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Leung E, Wall AM, MacMillan H, Boyle M, Trocme N, Waechter R. The contribution of childhood emotional abuse to teen dating violence among child protective services-involved youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse: Application of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2009;S(1):69–79. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19(7):559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. Alcohol abuse as a risk factor for and consequence of child abuse. Alcohol Research and Health. 2001;25:52–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, White HR. Problem behaviours in abused and neglected children grown up: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance abuse, crime and violence. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1997;7:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):348. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]