Abstract

Crime is a major public health and safety threat. Many studies have suggested that early exposure to child maltreatment increases an individual's risk for persistent serious crime in adulthood. Despite these findings about the connection between child maltreatment and criminal behavior, there is a paucity of empirically-based knowledge about the processes or pathways that link child maltreatment to later involvement in crime. Using a community sample of 337 young adults (ages 18-25) in a U.S. metropolitan area, the present study examined the role of various facets of impulsivity in linking child maltreatment to crime. A series of factor analyses identified three types of crime including property crime, violent crime, and fraud. Structural equation modelings were conducted to examine the associations among childhood maltreatment, four facets of impulsivity, and criminal behavior, controlling for sociodemographic information, family income and psychological symptoms. The present study found that child emotional abuse was indirectly related to property crime and fraud through urgency while a lack of premeditation mediates the relationship between child neglect and property crime. Child physical abuse was directly related to all three types of crime. Personality traits of urgency and lack of premeditation may play a significant role in the maltreatment-crime link. Preventive interventions targeting impulsivity traits such as urgency and a lack of premeditation might have promising impacts in curbing criminal behavior among maltreatment victims.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Child abuse, Child neglect, Impulsivity, Criminal behavior, Crime

Introduction

While crime rates have decreased significantly over the past two decades in the United States, crime still represents a serious social problem estimated to cost more than $1 trillion in direct annual loss to society.1-3A large body of research substantiates that early exposure to violence, such as child maltreatment, increases an individual's risk for a variety of health and social problems throughout the lifespan, and is particularly associated with persistent serious crime in young adulthood.4-10 This association might arise from a variety of determinants, ranging from genetic, neurobiological, psychological, environmental, and cultural factors.7,11 Recent studies examining the etiology of criminal behavior have focused on the role of personality traits in promoting crime. For example, a personality trait of impulsivity, which is often defined as a predisposition toward reacting rapidly or in unplanned ways to internal or external stimuli without proper regard for negative consequences or inherent risks, has been found to be one of the strongest personality-related predictors of crime.12-16 Although a high vulnerability of maltreated children to develop impulsive personality has been also widely documented, few studies have examined the specific role of impulsivity in linking childhood maltreatment and crime in later life.

Numerous studies have suggested that childhood maltreatment increases an individual's risk for persistent involvement in crime in adulthood.8,17-22 Several longitudinal studies estimate that maltreated children are 2 to 6 times more likely to develop criminal behavior in young adulthood, than are non-maltreated children. For example, in a well-designed longitudinal study of youth in high-crime areas, Smith and Thornberry (2013) found that child maltreatment was associated with a 2.24-fold (odd ratio) increase in risk for arrest, and with a 1.75-fold increase for general offending and a 2.03-fold increase for violent offending in young adulthood, controlling for adolescent antisocial behavior and socio-demographic characteristics.23 Similarly, in the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Stouthamer-Loeber and colleagues (2001) found that 77% of the maltreatment victims, compared to 43% of the non-victims, engaged in adolescent physical fighting, and that child maltreatment related to a 4-fold increase in truancy and running away from home.4 Further, exploring the link between child maltreatment and criminal behavior over three developmental periods (i.e., adolescence, early adulthood, adulthood) in the National Youth Survey, Fagan (2005) found a strong association between childhood maltreatment and involvement in criminal behavior that continued into adulthood across crime types including index offending and intimate partner violence.2 Although numerous studies have found a positive relationship between child maltreatment and crime, it is less clear why childhood maltreatment increases an individual's risk for crime.

Prior research examining the developmental sequelae of child maltreatment points to impulsivity as a significant susceptibility factor for criminal behavior.24-26 The literature suggests that many positive personality traits are difficult to learn for maltreatment victims who often lived in volatile and threatening caretaking environments. Therefore, maltreatment victims are more prone to develop impulsive personality traits.27,28 Exploring the longitudinal effects of child maltreatment on personality development children, Rogosch and Cicchetti (2004) found that victims of child maltreatment tended to show less adaptive personality traits that might be best described as impulsive, antagonistic, less trustworthy, and highly urgent.28,29 A recent study comparing cocaine users with a history of child maltreatment to cocaine users who have never been maltreated, suggests that the most salient group differences were not in intelligence or attention spans, but in impulsivity.25 In this study, maltreatment was associated with higher levels of impulsivity, controlling for current levels of cocaine use. Therefore, it is possible that maltreatment victims are highly vulnerable to the development and maintenance of criminal behavior because of impulsive personality traits.

Several theories of crime such as Gottfredson and Hirschi's general theory of crime suggest that personality traits of impulsivity are tightly related to all types of criminal behavior, which has been supported by a large body of empirical studies.12-14,30-33 In the Pathways to Desistance study of 701 adjudicated adolescents, Bechtold and colleagues (2013) found that adolescent impulsivity was associated with criminal behaviors throughout late adolescence and early adulthood.14 Moreover, impulsivity was identified as a significant predictor for violent crime such as physical fighting, using a weapon, hurting another person, armed robbery, and intimate partner violence.34 Given the critical role impulsivity plays in involvement in crime, it is not surprising to note that most risk assessment measures for criminal offending are designed to measure impulsivity more than any other constructs.35

Individuals who suffer from childhood maltreatment and those that are impulsive appear to be at elevated risk for crime. Despite indications that impulsivity might be the core factor underlying the negative effects of child maltreatment on criminal behavior in later life, it has received little attention, particularly with respect to its impact on different types of criminal behavior such as property crime, violent crime, and fraud. We examined the role of impulsivity in linking child maltreatment and criminal behavior, and explored how different impulsivity traits (e.g., non-planning, deliberation, urgency, sensation seeking) are associated with childhood maltreatment and criminal behavior in young adulthood.

Methods

Procedures and participants

The participants were young adults aged 18 to 25. All participants were recruited through advertisements placed in public areas such as bus stops, bulletin boards, and subway stations in a Northeastern metropolitan area. The recruitment advertisements, entitled “Childhood Experiences and Later Development,” simply introduced the present study as a “study about childhood, family, and physical and mental health.” Those individuals who responded to the advertisement were included in the study if they met the age requirement, and if their health status did not indicate any major medical concerns (e.g., cancer or other life-threatening illness) during the initial interview. Trained interviewers collected data through an hour-long, structured, face-to-face interview in a laboratory. Our sample includes 337 young adults (mean age= 21.7). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they were given a full description of the study requirements, risks, and potential benefits. The Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Childhood Maltreatment

Childhood maltreatment was assessed using a computer assisted self-interviewing (CASI) method of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ).36,37 A CASI has been found to increase endorsement rates of sensitive behaviors such as child maltreatment and crime.38,39 The CTQ (25 items) measures four types of child maltreatment including emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and neglect that occurred prior to age 18, and demonstrated adequate reliability and validity.37,40 Using previously established procedures described in empirical studies, severity scores for each maltreatment subtypes were computed.37,41 Internal consistencies of the CTQ for the current study are .89 (Cronbach's α) for emotional, .86 for physical, .86 for sexual abuse, and .71 for neglect.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was measured by the Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, and Sensation Seeking (UPPS) Impulsive Behavior Scale.42 The UPPS measures four characteristics of impulsivity, including urgency (12 items), (lack of) premeditation (11 items), (lack of) perseverance (10 items), and sensation seeking (12 items). Higher UPPS scale scores indicate a more impulsive personality. The UPPS scale has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity.42-44 Internal consistencies of the UPPS for the current study are .89 for urgency, .92 for premeditation, .72 for perseverance, and .90 for sensation seeking.

Crime

We used a 13-item crime questionnaire adapted from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Study.45 It measures the respondent's criminal involvement in the past 12 months. Sample items are included in Table 2, which have a range of response categories from 0 (never) to 3 (5 or more times).

Table 2.

Standardized loadings for constructs in confirmatory model of criminal behavior (Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

| Loading |

|

|---|---|

| Construct and indicators | |

| Property crime | |

| Property damage | .72 |

| Stealing > $50 | .85 |

| Stealing < $50 | .84 |

| Buy/sell/hold stolen property | .75 |

| Violent crime | |

| Physical fight | .59 |

| Weapon in fight | .67 |

| Injured in fight | .78 |

| Injured others in fight | .80 |

| Fraud | |

| Use stolen credit/ATM cards | .55 |

| Write bad checks | .94 |

Covariates

Psychological symptoms were measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18).46 The BSI-18 measures three dimensions of psychological symptoms including somatization, depression, and anxiety, in the past seven days, and computes the BSI Global Severity Index (GSI) score, of which higher scores of the GSI indicate a higher level of overall psychological symptoms. An internal consistency for the current sample was .93. Finally, demographic information, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and family income was assessed by using a structured questionnaire.

Data analysis

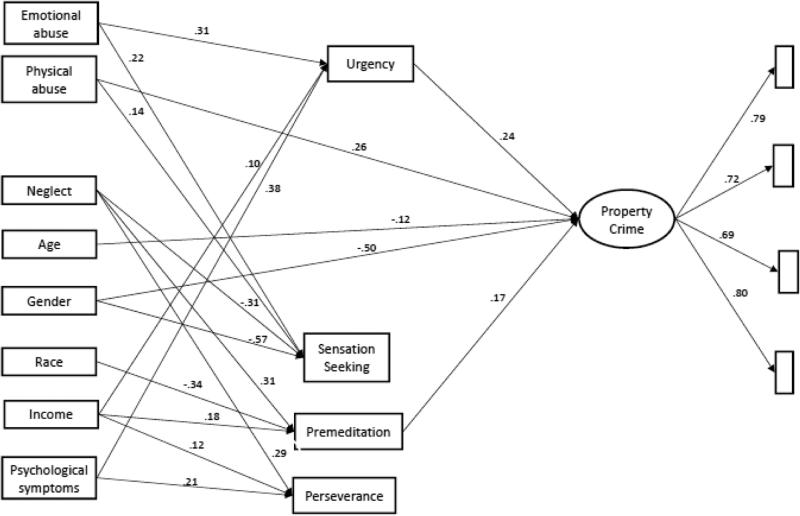

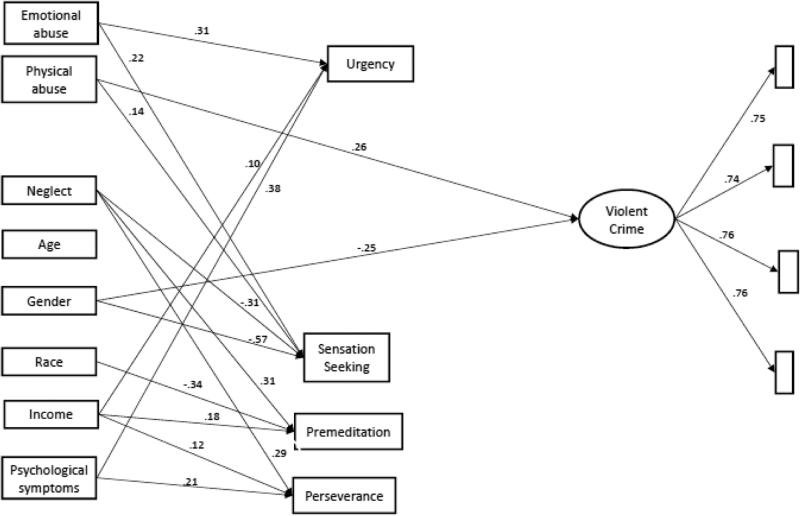

We performed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the measurement structure of the crime measure. The relationships among child maltreatment, impulsivity, and crime were explored by conducting three separate structural equation modelings (SEMs; Figures 1-3). Four types of maltreatment along with demographic variables and psychological symptoms were specified to directly affect criminal behavior variables and to indirectly affect them through the mediating variable, impulsivity. The indirect effect of maltreatment on crime, via impulsivity, was examined as the product of the coefficients of these relationships, and the standard errors of the indirect effects were calculated using the delta method.47-49 In accordance with previous recommendations, we used the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR) as standardized indices of model fit.50 A model can be considered to fit the data well if CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.06, and SRMR < 0.08.50,51 The Mplus 7.0 was used for all analyses using maximum likelihood estimation.52 Because four cases had missing data on both childhood maltreatment and crime, final analyses included 333 participants.

Figure 1.

Structural model for child maltreatment, impulsivity, and property crime. Exogenous variables specified as freely correlated. Covariances of exogenous variables and of residual terms for endogenous constructs were included in the model, but are not shown in the figure. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, and values are standardized coefficients. Coefficients are significant at p < .05. Only significant paths are shown (Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

Figure 3.

Structural model for child maltreatment, impulsivity, and fraud. Exogenous variables specified as freely correlated. Covariances of exogenous variables and of residual terms for endogenous constructs were included in the model, but are not shown in the figure. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, and values are standardized coefficients. Coefficients are significant at p < .05. Only significant paths are shown (Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

Results

Measurement Structure of Criminal Behavior

We specified a series of EFA models using the 13 crime-related items to examine the measurement structure of crime. Standardized factor loadings of .50 were used as evidence that an item had a meaningful loading on a construct. We compared the fits of models in which the indicators of crime were specified as measuring from one to four constructs. Initially, two items were dropped due to small factor loadings. Then, using the remaining 11 items, a 3-factor solution in which the indicators of crime are specified as measuring three constructs was compared to a 1-factor and a 2-factor solution. A 4-factor solution did not converge. Compared to a 1-factor (χ2 (65)=755.56, CFI=.63, RMSEA=.18, SRMR=.11) and a 2-factor solutions (χ2 (53)=380.41, CFI=.82, RMSEA=.14, SRMR=.07), a 3-factor solution had better fit (χ2 (42)=212.15, CFI=.91, RMSEA=.11, SRMR=.04). Eigenvalues for the correlation matrix were 5.05 (1-factor), 1.80 (2-factor), 1.41 (3-factor), and 0.89 (4-factor solution). Thus, after conducting CFA of the 3-factor solution, which fit the data well (χ2 (32)=186, CFI=.89, RMSEA=.01, SRMR=.07), a 3-factor model with latent constructs representing property, violent, and fraudulent crime was used in further analyses. Factor loadings for the CFA model and the indicators of each latent construct are presented in Table 2 whereas construct correlations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations of study variables (Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Abuse | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Physical Abuse | .64** | — | |||||||||

| 3. Sexual Abuse | .31** | .37** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Neglect | .75** | .53** | .33** | — | |||||||

| 5. Urgency | .40** | .19** | .05 | .29** | — | ||||||

| 6. Premeditation | .11* | .06 | .03 | .19** | .39** | — | |||||

| 7. Perseverance | .13* | .01 | .00 | .20** | .48** | .48** | — | ||||

| 8. Sensation Seeking | .01 | .08 | −.05 | −.12* | .15** | .18** | .01 | — | |||

| 9. Property Crime | .27** | .36** | .17** | .24** | .39** | .27** | .25** | .17** | — | ||

| 10. Violent Crime | .30** | .38** | .17** | .30** | .25** | .14** | .10 | .07 | .61** | — | |

| 11. Fraud | .24** | .36** | .22** | .26** | .25** | .17** | .13* | .10 | .61** | .51** | — |

Note: N for analysis = 333.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Childhood Maltreatment, Impulsivity, and Crime

Figure 1 presents the property crime model (χ2=77, df=41, CFI=.97, RMSEA=.05). Among maltreatment subtypes, only physical abuse had a direct significant path to property crime. Emotional abuse had a significant path to urgency and sensation seeking. Physical abuse was associated with sensation seeking whereas neglect had a significant path to sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance. Furthermore, out of four types of impulsivity, urgency and lack of premeditation had direct significant paths to property crime. A test of indirect paths found that the mediated effects of emotional abuse on property crime via urgency were significant (β=.07), and that lack of premeditation mediated the association between neglect and property crime (β=.07).

The violent crime model showed reasonable model fit (Figure 2; χ2=87, df=41, CFI=.95, RMSEA=.06). Regarding the subtypes of maltreatment, only physical abuse was significantly related to violent crime. Emotional abuse was associated with urgency and sensation seeking whereas physical abuse had a direct significant path to sensation seeking. Furthermore, childhood neglect was related to sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance. Finally, impulsivity was not related to violent crime.

Figure 2.

Structural model for child maltreatment, impulsivity, and violent crime. Exogenous variables specified as freely correlated. Covariances of exogenous variables and of residual terms for endogenous constructs were included in the model, but are not shown in the figure. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, and values are standardized coefficients. Coefficients are significant at p < .05. Only significant paths are shown (Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

Figure 3 represents the fraudulent crime model (χ2=16, df=12, CFI=.99, RMSEA=.03). Among all subtypes of maltreatment, physical abuse and sexual abuse had a direct significant path to fraudulent crime. Emotional abuse had a direct significant path to urgency and sensation seeking whereas physical abuse was related to sensation seeking. Neglect was associated with sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance. Lastly, out of the four types of impulsivity, urgency had a direct significant path to fraudulent crime. Results for indirect effects also showed that urgency mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and fraud (β=.06).

Discussion

We examined the relationships among childhood maltreatment, impulsivity, and three types of crime. Three main findings emerged. First, regarding the associations among child maltreatment, impulsivity and crime, emotional abuse was associated with urgency which in turn was associated with property crime as well as fraud, even after controlling for demographic and socioeconomic status, and psychological symptoms. Second, lack of premeditation significantly mediated the relationship between child neglect and property crime. Lastly, physical abuse was significantly and directly related to all types of crime.

The impulsive trait of urgency may play a significant role in linking emotional abuse to crime in young adulthood. Urgency mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and two types of crime such as property crime and fraud. According to the UPPS model of impulsivity, urgency represents a tendency to act impulsively in order to alleviate negative emotional states.42 Individuals who experienced emotional abuse may adversely respond to psychological distress by acting impulsively. The literature suggests that emotional abuse is more strongly related to psychological symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression), than physical or sexual abuse.53-56 Therefore, young adults with a history of childhood emotional abuse may be prone to committing crime in part because they are unlikely to inhibit behavior under the influence of psychological distress. Along the same lines, our findings regarding emotional abuse and property crime, particularly vandalism, could be explained through the development of uncontrollable negative emotionality such as anger and hostility that is built up as a result of emotional abuse and could foster a desire to destroy property.57 Victims of emotional abuse who have urgent personality traits may be stealing and vandalizing property to release and regulate emotional negativity. However, our findings of the significant association between urgency and crime even after controlling for psychological symptoms also suggest that urgency may have an independent impact on crime among emotional abuse victims regardless of levels of psychological symptoms. Therefore, future studies are warranted to examine the interactive effects of urgency and negative emotionality on crime.

We also found that child neglect was associated with lack of premeditation, which in turn influenced property crime. Since premeditation is the idea that individuals inhibit impulsive responses and delay action in favor of careful thinking and planning, it seems that young individuals who suffer from childhood neglect are likely to act without consideration of future consequences of their actions.42 There are a number of ways child neglect may influence lack of premeditation. From developmental perspectives, the development of personality traits of premeditation often depends on interactions between attributes of a child and the social environment in which development takes place, such as parents and families.58-60 Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) have argued that self-regulation is primarily a result of parenting practices, including appropriate monitoring, supervision and correction.12 Child neglect, which is often defined as parental failure to provide a minimum degree of care, includes parental omissions in monitoring, supervising and modeling proper impulse control.61 Indeed, prior research reports the significant relationship between parenting styles/practices and the development of various individual traits such as self-regulation.62-71 For example, De Bellis and his colleagues (2009) found that compared to non-victims of child neglect, neglected children had significantly limited premeditation attributes in early childhood (ages 7 to 8), including attention and planning.72 Therefore, child neglect might be related to lack of monitoring, modeling and reinforcement of premeditation skills in adolescence, which could manifest in a lack of premeditation in young adulthood.

The literature also suggests that childhood neglect is related to neurological deficits. Several studies have indicated that child neglect is related to altered brain development in regions that are involved in cognitive functioning and planning such as the prefrontal cortex and corpus callosum.73-76 This suggests that maltreatment-related structural and functional alterations in the brain may instigate cognitive difficulties in planning and premeditation, which in turn enhances risk for criminal behavior among neglect victims.

In our study, child physical abuse had direct significant paths to all three types of crime. Although there are mixed findings in relation to property crime among victims of physical abuse, previous studies have reported consistent patterns of a relationship between physical abuse and violent crime.2,21,22,77-83 The literature also suggests that physical abuse is more likely to relate to violent crime than sexual abuse or neglect.84

Multiple ways have been suggested in which physical abuse is linked to aggression and violence. Some argue that physical abuse and violence share negative family factors of which explain the association between early exposure to physical abuse and violent crime in later lives whereas others hypothesize that exposure to physical abuse directly relates to violence independent of negative family environment.81,85-87 For example, while its position is not fully supported by some research, the cycle of violence theory assumes that children's experience of physical abuse, particularly by their caregivers, increases their risk of engaging in aggression and violent crime in adulthood because of abusive rearing environment.84,88,89 Hostile and abusive family environments often relate to lacks of family warmth and support, promote deviant socialization, and foster violent coping strategies such as lashing out in anger, being aggressive with others and getting into fights.90-92 Using data from the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Stouthamer-Loeber and colleagues (2002) found that family environmental factors were related to maltreatment as well as to persistent violence.87 However, when family characteristics and environment are controlled, child maltreatment did not relate to persistent violence any longer.87 In contrast, another study found that exposure to physical abuse was associated with aggression and violence even after controlling for family factors such as family structure, family offending history, and family conflict.77 In the same study, the association between physical abuse and property crime disappeared when the family factors are controlled. Future research is warranted to examine the complex relationships among adverse family characteristics, exposure to physical abuse and violent crime to identify the independent or combined effects of family environment and physical maltreatment on later development of violent crime.

There are a number of theoretical and policy implications of our findings. First, we found evidence that child maltreatment in the forms of emotional abuse and neglect were related to higher levels of urgency and lower premeditation, which in turn influenced property and fraudulent crimes. Thus, our evidence indicates that the effects of childhood emotional abuse and neglect may be offset by early preventive intervention targeting individual traits and self-regulation processes such as those reflecting urgency and premeditation. For example, a prevention program that targets individual self-regulation processes to avoid rapid and unplanned reaction to internal or external stimuli and to decrease the tendency to act rashly to regulate negative emotion may have crime-reducing impacts as well. Furthermore, a large body of evidence suggests that impulsivity and low self-control may also be influenced by socialization efforts. For example, Hay and Forrest (2006) examined self-reported parenting techniques and self-control of the child from age 7 to 15.70 Although finding substantial stability in self-reported self-control over time, they found that changes in parenting techniques significantly influenced changes in a child's self-control capability over time. They conclude that when the quality of parental socialization and interactions increase, so does self-control of the child. This suggests that later socialization experiences with conventional others as well as preventive interventions may also impact the development of urgency and premeditation. Our results also suggest some levels of specificity in the effects of maltreatment subtypes on impulsivity subtraits as well as criminal behavior. Specific forms of child maltreatment were significantly associated with various forms of impulsivity traits, as well as criminal offending. This suggests that greater specificity and precision in identifying specific forms of maltreatment would benefit the identification and assessment of the best suitable treatment programs for victims of childhood abuse and neglect.

Study limitations and strengths

The current study had several limitations and strengths. First, involvement in criminal behavior came from young adult self-reports, which are subject to social desirability bias. Furthermore, given that we used a retrospective self-report of child maltreatment, it is possible that participants may have had trouble recalling their past histories of maltreatment. A few studies examining convergent validity of retrospective childhood maltreatment reports have concluded that when research participants report childhood maltreatment, their self-reports are relatively concordant with official records (e.g., court records) and reports from other informants (e.g., siblings, parents).93 In a recent longitudinal study, Everson and colleagues (2008) also found that adolescent self-reports of child maltreatment surpassed child protective services determinations of child maltreatment in predicting psychopathological symptoms.94 Second, it is also important to acknowledge that other factors besides child maltreatment may have influenced criminal behavior in young adulthood, including substance abuse, genetics, parental substance abuse and criminal histories which have been shown to influence criminal offending.78,95-97 Third, since we used a non-probability convenient sample from one urban setting, we have no way of determining its representativeness. However, as presented in Table 1, the prevalence of different forms of child maltreatment among our sample is highly comparable to the child maltreatment statistics reported by both the federal government and studies using population-based probability samples.98,99 Finally, although life-course criminology studies underscore the importance of examining processes within adverse childhood experiences such as child maltreatment, our measure of child maltreatment only assess the severity of maltreatment.5,100,101 Therefore, future studies need to examine the effects of the totality of a child's maltreatment experience on the development of criminal behavior and to include other maltreatment-event characteristics such as developmental timing of abuse and neglect, and chronicity of maltreatment experiences. Finally, the present study is limited by its use of a cross-sectional design, which does not provide any insight into temporal ordering among child maltreatment, impulsivity, and criminal behavior. Although we found that emotional abuse was related to property and fraud-based crime through urgency, involvement in criminal behavior during adolescence might promote urgent and unplanning personality traits. Therefore, impulsivity might be the negative outcome of chronic involvement in crime as well as the predictor of it.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N =333; Past to Present survey, 2013, United States).

| Range | Mean (SD) a or % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 18-25 | 21.7 (2.1) |

| Gender b | ||

| Male | 47.5 (160) | |

| Female | 52.5 (177) | |

| Race/Ethnicity b | ||

| White | 55.5 (187) | |

| Black | 16.9 (57) | |

| Hispanic | 8.6 (29) | |

| Asian | 8.0 (27) | |

| Other | 10.7 (36) | |

| Family Income | ||

| Much less than enough money for our needs | 1.9 (6) | |

| Less than enough money for our needs | 21.4 (72) | |

| Enough money for our needs | 52.5 (177) | |

| More than enough money for our needs | 23.0 (78) | |

| Much more than enough money for our needs | 1.2 (4) | |

| Impulsivity | ||

| Urgency | 12-57 | 27.3 (9.8) |

| Lack of Premeditation | 11-55 | 27.2 (8.6) |

| Lack of Perseverance | 10-45 | 22.8 (7.5) |

| Sensation Seeking | 12-60 | 40.0 (11.5) |

| Psychological Distress | 33-80 | 50.9 (10.8) |

| Childhood Maltreatment | ||

| Emotional abuse | 5-25 | 9.98 (5.3) |

| Physical abuse | 5-25 | 7.64 (4.2) |

| Sexual abuse | 5-25 | 5.94 (3.1) |

| Neglect | 5-22 | 8.88 (3.7) |

Valid percentages are reported.

Proportion (N). All other measures reported in mean values (standard deviations).

Conclusion

Impulsivity is an important personality trait that influences delinquency and criminal involvement in young adulthood. The present study examined the complex pathways from childhood maltreatment to impulsivity, and from impulsivity to crime. We also explored how distinct forms of impulsivity relate to different types of criminal behavior in young adulthood. Our results indicate that urgency and lack of premeditation play important roles in the maltreatment-crime link, and should be included in crime prevention and intervention programs serving young adult victims of childhood maltreatment.

Highlights.

Childhood maltreatment increases the risk for later involvement in crime.

Few studies have explored the pathways from child maltreatment to crime.

We examined the role of impulsivity in the child maltreatment to crime link.

Impulsivity played a significant role in linking child maltreatment to crime.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source: This research was supported by grants from NIDA DA030884 (Shin) and the AMBRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research (Shin). The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McCollister KE, French MT, Fang H. The cost of crime to society: new crime-specific estimates for policy and program evaluation. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1-2):98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagan A. The Relationship Between Adolescent Physical Abuse and Criminal Offending: Support for an Enduring and Generalized Cycle of Violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(5):279–290. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics. 2016 http://www.ucrdatatool.gov/

- 4.Stouthamer, Loeber M, Loeber R, Homish DL, Wei E. Maltreatment of boys and the development of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widom CS, White HR. Problem behaviours in abused and neglected children grown up: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance abuse, crime and violence. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1997;7:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maas C, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C. Review on research on child maltreatment and violence in youth. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2008;9(1):56–67. doi: 10.1177/1524838007311105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith CA, Ireland TO, Thornberry TP. Adolescent maltreatment and its impact on young adult antisocial behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(10):1099–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelhor D. Childhood Victimization: Violence, Crime, and Abuse in the Lives of Young People. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Taylor A. Physical maltreatment victim to antisocial child: evidence of an environmentally mediated process. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(1):44–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson HW, Stover CS, Berkowitz SJ. Research review: The relationship between childhood violence exposure and juvenile antisocial behavior: a meta-analytic review. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2009;50(7):769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruise KR, Fernandez K, McCoy WK, Guy LS, Colwell LH, Douglas TR. The Influence of Psychosocial Maturity on Adolescent Offenders' Delinquent Behavior. Youth violence and juvenile justice. 2008;6(2):178–194. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bechtold J, Cavanagh C, Shulman EP, Cauffman E. Does mother know best? Adolescent and mother reports of impulsivity and subsequent delinquency. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2014;43(11):1903–1913. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP. Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental psychology. 2009;45(6):1654–1668. doi: 10.1037/a0015862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pratt TC, Cullen FT. The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi's general theory of crime: A meta-analysis. Criminology. 2000;38(3):931–964. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and violent delinquency: Disentangling main effects and subgroup effects. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):246–258. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Violent children: bridging development, intervention, and public policy. Developmental psychology. 2003;39(2):187–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxfield MG, Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Revisited 6 years later. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1996;150(4):390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The causal impact of childhood-limited maltreatment and adolescent maltreatment on early adult adjustment. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: a prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12(3):233–245. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widom CS. An examination of pathways from childhood victimization to violence: The role of early aggression and problematic alcohol use. Violence and Victims. 2006;21(6):675–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CA, Park A, Ireland TO, Elwyn L, Thornberry TP. Long-term outcomes of young adults exposed to maltreatment: the role of educational experiences in promoting resilience to crime and violence in early adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(1):121–156. doi: 10.1177/0886260512448845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beers SR, De Bellis MD. Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related Posttraumatic Sress Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):483–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narvaez JCM, Magalhães PVS, Trindade EK, et al. Childhood trauma, impulsivity, and executive functioning in crack cocaine users. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2012;53(3):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall-Tackett K. The health effects of childhood abuse: four pathways by which abuse can influence health. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6-7):715–729. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56(7):600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogosch F, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment and emergent personality organization: Perspectives from the five-factor model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(2):123–145. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019766.47625.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Committee for Hispanic Children and Families Inc. Creating a Latino child welfare agenda: A strategic framework for change. The Committee For Hispanic Children And Families, Inc.; New York: n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luengo MA, Carrillo-de-la-Pena MT, Otero JM, Romero E. A short-term longitudinal study of impulsivity and antisocial behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1994;66(3):542–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jolliffe D, Farrington DP. A systematic review of the relationship between childhood impulsiveness and later violence. Personality, Personality disorder, and violence. 2009:41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitaro F, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE. Impulsivity predicts problem gambling in low SES adolescent males. Addiction. 1999;94(4):565–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94456511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loeber R, Blanc ML. Toward a Developmental Criminology. Crime and Justice. 1990;12:375–473. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derefinko K, DeWall CN, Metze AV, Walsh EC, Lynam DR. Do different facets of impulsivity predict different types of aggression? Aggressive behavior. 2011;37(3):223–233. doi: 10.1002/ab.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulvey EP, Iselin AM. Improving professional judgments of risk and amenability in juvenile justice. The Future of children / Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 2008;18(2):35–57. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. Harcourt Brace, Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.WRIGHT DL, AQUILINO WS, SUPPLE AJ. A Comparison of Computer-Assisted and Paper-and-Pencil Self-Administered Questionnaires in a Survey on Smoking, Alcohol, and Drug Use. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1998;62(3):331–353. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright KD, Asmundson GJG, McCreary DR, Scher C, Hami S, Stein MB. Factorial validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in men and women. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13(4):179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(7):1927–1937. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19(7):559–574. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. 2003 http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html.

- 46.Derogatis LR. BSI Brief Symptom Inventory. Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. 4ed. National Computer Systems; Minneapolis: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating Mediated Effects in Prevention Studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarter R, Vanyukov M. Introduction: Theoretical and operational framework for research into the etiology of substance use disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;10(4):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, et al. History of childhood maltreatment, negative cognitive styles, and episodes of depression in adulthood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25(4):425–446. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self-system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2006;77(3):624–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGee RA, Wolfe DA, Wilson SK. Multiple maltreatment experiences and adolescent behavior problems: Adolescents’ perspectives. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:131–149. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ribeiro da Silva D, Rigo D, Salekin R. Child and adolescent psychopathy: Assessment issues and treatment needs. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wills TA, Dishion TJ. Temperament and adolescent substance use: A transactional analysis of emerging self-control. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology : the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2004;33(1):69–81. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zimmerman BJ. Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In: Boekaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cicchetti D, Valentino K. An ecological transactional perspective on child maltreatment: Failure of the average expectable environment and its influence upon child development. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation (2nd ed.) 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 129–201. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scannapieco M. Developmental outcomes of child neglect. APSAC Advisor. 2008;20(1):7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baumrind D. Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Development. 1966;37(4):887–907. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baumrind D. The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Competence and Substance Use. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11(1):56–95. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gray MR, Steinberg L. Unpacking Authoritative Parenting: Reassessing a Multidimensional Construct. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(3):574–587. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement. Child Development. 1992;63:1266–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinberg L, Elmen JD, Mounts NS. Authoritative Parenting, Psychosocial Maturity, and Academic Success among Adolescents. Child Development. 1989;60(6):1424–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM. Authoritative Parenting and Adolescent Adjustment Across Varied Ecological Niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Lawrence Erlbaum) 1991;1(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Unnever JD, Cullen FT, Pratt TC. Parental management, ADHD, and delinquent involvement: Reassessing Gottfredson and Hirschi's general theory. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20(3):471–500. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hay C. PARENTING, SELF-CONTROL, AND DELINQUENCY: A TEST OF SELF-CONTROL THEORY*. Criminology. 2001;39(3):707–736. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hay C, Forrest W. THE DEVELOPMENT OF SELF-CONTROL: EXAMINING SELF-CONTROL THEORY'S STABILITY THESIS*. Criminology. 2006;44(4):739–774. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hope TL, Grasmick HG, Pointon LJ. THE FAMILY IN GOTTFREDSON AND HIRSCHI'S GENERAL THEORY OF CRIME: STRUCTURE, PARENTING, AND SELF-CONTROL. Sociological Focus. 2003;36(4):291–311. [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Bellis MD, Hooper SR, Spratt EG, Woolley DP. Neuropsychological findings in childhood neglect and their relationships to pediatric PTSD. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15(6):868–878. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Brito SA, Viding E, Sebastian CL, et al. Reduced Orbitofrontal and Temporal Grey Matter in a Community Sample of Maltreated Children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tomoda A, Suzuki H, Rabi K, Sheu YS, Polcari A, Teicher MH. Reduced prefrontal cortical gray matter volume in young adults exposed to harsh corporal punishment. NeuroImage. 2009;47(Suppl 2):T66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen RA, Grieve S, Hoth KF, et al. Early life stress and morphometry of the adult anterior cingulate cortex and caudate nuclei. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(10):975–982. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Teicher MH, Ito Y, Glod CA, Andersen SL, Dumont N, Ackerman E. Preliminary evidence for abnormal cortical development in physically and sexually abused children using EEG coherence and MRI. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;821:160–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Physical punishment/maltreatment during childhood and adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(7):617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Forsman M, Langstrom N. Child maltreatment and adult violent offending: population-based twin study addressing the ‘cycle of violence’ hypothesis. Psychological medicine. 2012;42(9):1977–1983. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rebellon CJ, Van Gundy K. Can Control Theory Explain the Link Between Parental Physical Abuse and Delinquency? A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2005;42(3):247–274. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watts SJ, McNulty TL. Childhood abuse and criminal behavior: testing a general strain theory model. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2013;28(15):3023–3040. doi: 10.1177/0886260513488696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Widom CS. Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59(3):355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Widom CS, White HR. Problem behaviours in abused and neglected children grown up: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance abuse, crime and violence. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1997;7:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wright EM, Fagan AA. The cycle of violence in context: Exploring the moderating roles of neighborhood disadvantage and cultural norms. Criminology. 2013;51(2):217–249. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Widom C. In: The cycle of violence. U.S. Department of Justice NIoJ, editor. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kelley BT, Thornberry TP, Smith CA. In the wake of childhood maltreatment. National Institute of Justice; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Henggeler SW, McKee E, Borduin CM. Is There a Link Between Maternal Neglect and Adolescent Delinquency? Journal of clinical child psychology. 1989;18(3):242–246. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stouthamer-Loeber M, Wei EH, Homish DL, Loeber R. Which Family and Demographic Factors Are Related to Both Maltreatment and Persistent Serious Juvenile Delinquency? Children's Services. 2002;5(4):261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dixon L, Browne K, Hamilton-Giachritsis C. Risk factors of parents abused as children: a mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part I). J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ. Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systematic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2012;13(3):135–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838012447697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brezina T. Adolescent Maltreatment and Delinquency: The Question of Intervening Processes. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1998;35(1):71–99. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child maltreatment. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Polo-Tomas M, Taylor A. Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: a cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(3):231–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bifulco A, Brown GW, Lillie A, Jarvis J. Memories of childhood neglect and abuse: Corroboration in a series of sisters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(3):365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Everson MD, Smith JB, Hussey JM, et al. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood abuse and child protective service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13(1):14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cook AK. I'm tired of my child getting into trouble: Parental controls and supports of juvenile probationers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2013;52:529–543. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hirschel D, Hutchison I, Shaw M. The Interrelationship Between Substance Abuse and the Likelihood of Arrest, Conviction, and Re-offending in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25(1):81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Widom CS, Marmorstein NR, White HR. Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(4):394–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Child Maltreatment 2013. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cicchetti D, Cohen D. Theory and method, risk, disorder, and adaptation: Developmental psychopathology, 1-2. 1-2. Wiley; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Understanding desistance from crime. Crime and Justice. 2001;28:1–69. [Google Scholar]