Abstract

Background: Despite its considerable personal toll and its impact on the economy and the legal system, kleptomania is an understudied psychiatric disorder.

Method: We review what is known about the epidemiology, course, and treatment of kleptomania and describe 40 patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for the disorder.

Results: Our data suggest a female preponderance, with an early age at onset and most often a continuous course. No other gender-based differences were seen. The majority of our subjects had not received treatment for kleptomania despite often having sought help for comorbid psychiatric conditions, most commonly major depressive disorder. Our data confirm kleptomania's devastating effects on personal and professional lives and serious legal consequences, reflected in high arrest and incarceration rates. Because patients with kleptomania rarely seek psychiatric help for the disorder, we indicate how other health care providers can screen for it, possibly as part of taking patients' legal and social histories, and suggest treatments.

Conclusion: Awareness of kleptomania, empathy toward those afflicted, and rigorous research into treatment options are needed to mitigate kleptomania's personal and societal costs.

Since its introduction into the psychiatric lexicon as a diagnostic term in 1838,1 kleptomania has been the subject of intense controversy and debate. In question is whether it represents a medical disorder or a form of illegal and deviant behavior more akin to sociopathy. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (DSM-IV)2 includes kleptomania with the impulse control disorders not elsewhere classified, alongside trichotillomania (compulsive hair pulling), pyromania (compulsive fire setting), and intermittent explosive disorder. DSM-IV defines kleptomania as a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Like other impulse control disorders, kleptomania is characterized by an anxiety-driven urge to perform an act that is pleasurable in the moment but causes significant distress and dysfunction. Careful attention should be given to distinguishing kleptomania from antisocial personality disorder. Unlike the latter disorder, kleptomania is characterized by the presence of guilt and remorse and the lack of theft motives such as monetary gain, personal use, stealing to impress someone, or stealing to support a drug habit.

The prevalence of kleptomania in the U.S. general population is unknown but has been estimated at 6 per 1000 people, which translates into about 1.2 million of the 200 million American adults.3 Kleptomania is thought to account for 5% of shoplifting.4 Based on total shoplifting costs of $10 billion in 2002,5 this 5% translates into a $500 million annual loss to the economy attributable to kleptomania. This loss does not include the costs associated with stealing from friends and acquaintances or costs incurred by the legal system. Besides its grave toll on individuals and families, kleptomanic behavior carries serious legal consequences: approximately 2 million Americans are charged with shoplifting annually.6 If kleptomania accounts for 5% of these, this translates into 100,000 arrests.

Here, we describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of 40 subjects meeting DSM-IV criteria for kleptomania. We conclude with suggestions for treatment options derived from the scant literature available.

METHOD

We recruited subjects using local radio and newspaper advertisements. Subjects called our research telephone line, and a diagnostic interview was scheduled. At the beginning of the interview, we obtained verbal informed consent as approved by our institutional review board. Subjects were assured of the confidentiality of all information, and all identifying information was removed from their interview responses. Careful attention was given to ruling out antisocial personality disorder. Subjects meeting the DSM-IV criteria for kleptomania were then further interviewed.

The interviewer (E.A., L.M.K.) elicited any lifetime history of psychiatric comorbidities, substance abuse or dependence, and medical conditions as well as current and past psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic interventions. Based on the findings by Grant and Kim7 that correlate kleptomanic behavior with specific stimuli and mood states, subjects were asked about possible triggers for stealing, such as sights, objects, depression, anxiety, anger, and boredom as well as any spontaneous urges to steal occurring on or shortly after awakening. The course of the disorder was assessed by inquiring about the age at onset, the continuous versus episodic nature of the stealing, and the longest kleptomania-free interval. Subjects were asked for their theft frequency in the 2 weeks, 1 month, and 6 months prior to the interview. The number of arrests and incarcerations and the nature of the punishment were recorded. Marital status, employment status, and annual household income also were obtained.

Given the relatively small sample size in some of the statistical categories studied, the Fisher exact test was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

Of 72 callers we interviewed, 40 subjects meeting the DSM-IV criteria for kleptomania were identified. Of the 32 callers who did not have kleptomania, 11 had remorseless stealing more consistent with antisocial personality disorder, 3 had bipolar disorder and stole only while in a manic or hypomanic phase, 3 stole to support a drug habit, and the remaining 15 called to learn more about the disorder but did not suffer from it.

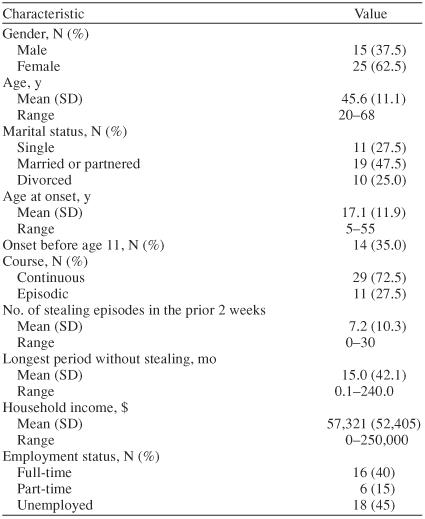

Table 1 displays the subjects' demographic and clinical characteristics. The majority of the 40 callers with kleptomania were female. The subjects' mean age was 45.6 ±11.1 years (median = 47.5; range, 20 to 68 years). About half were married or partnered, one quarter were divorced, and one quarter were single. The mean and median ages at onset were in the teenage years, and one third had onset before adolescence. Most subjects had a continuous course after onset. Stealing episodes were frequent in the 2 weeks prior to presentation, with a median of 4 episodes. Periods between stealing episodes were generally short, with a median of slightly less than 3 months. No statistically significant difference was seen between the genders with regard to age at onset, nature of course, number of stealing episodes, and longest stealing-free interval (Fisher exact test).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics in 40 Subjects With DSM-IV–Defined Kleptomania

Of the 40 study participants, only 2 subjects (5.0%) had received medication treatment for kleptomania. They had been prescribed sertraline and fluoxetine, at unknown doses, with only mild benefit. Thirteen participants (32.5%) had received counseling specifically targeting kleptomania: 11 (27.5%) had been treated in individual psychotherapy and 2 (5.0%) in group psychotherapy. Two subjects (5.0%) undertook therapy to comply with a court order that followed an arrest. None of the subjects who received psychotherapy experienced any sustained improvement in their symptoms.

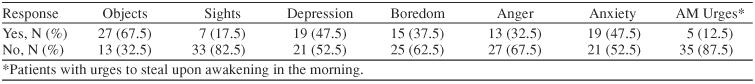

Triggers for stealing varied (Table 2). The most common were particular objects and depression and anxiety states.

Table 2.

Kleptomania Triggers in 40 Subjects With DSM-IV–Defined Kleptomania

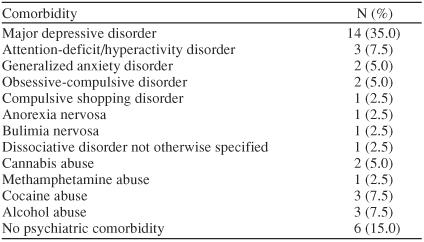

Thirty-four subjects (85.0%) had a lifetime comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, with major depressive disorder being by far the most common comorbid condition (Table 3). These disorders are thought to be independent from kleptomania since, although some patients described depression and anxiety states as possible triggers for kleptomanic behavior (Table 2), no patients reported stealing exclusively when feeling depressed or anxious.

Table 3.

Lifetime Psychiatric Comorbidities in 40 Subjects With DSM-IV–Defined Kleptomania

Thirty-one subjects (77.5%) had been arrested for shoplifting. The mean number of arrests for the group was 2.4 (median = 2; range, 0 to 10), and 7 subjects (17.5%) had served jail time.

Almost every subject (N = 39, 97.5%) had actively lied about their kleptomanic behavior to spouses and close family members. Nineteen subjects (47.5%) felt that hiding this consuming problem from loved ones led directly to deterioration of those relationships. For 17 subjects (42.5%), kleptomanic behavior seriously impaired work productivity through work time wasted dealing with the urges, the guilt that follows the theft, and the personal and legal consequences of the behavior.

DISCUSSION

These data indicate an early onset for DSM-IV–defined kleptomania: 35.0% of subjects manifested their first symptoms before age 11. For the entire sample, the mean age at onset was about 17, similar to that reported in other series.7 This finding underlines the importance of early diagnosis and intervention, which might help prevent a commonly lifelong condition (unrelenting for 72.5% of study subjects, although the recruitment method may have underrepresented patients for whom the problem is transient in nature, as they may be less likely to enroll in such a trial).

Other epidemiologic reviews have suggested a female preponderance for kleptomania, ranging from 77% to 81% of the total sample1,3; our data indicate a slightly lower female to male ratio of 5:3 (62.5%). One possible explanation for the higher rates among females is that they may be more likely to be given a diagnosis of kleptomania and males a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder.

Lifetime psychiatric comorbidities appeared to be common, affecting 85% of subjects. Some series have reported bipolar disorder to be the most common comorbidity,4,8 whereas another,7 like ours, found major depressive disorder to be more common. We identified no cases of comorbid bipolar disorder, although 3 callers with bipolar disorder who did not have kleptomania reported stealing only during hypomanic or manic periods. Despite attempted treatment of comorbid conditions in nearly half of our subjects, less than 5% received psychopharmacologic interventions specifically targeting kleptomania. This finding may be due to patients not feeling safe disclosing to their treating clinicians a problem that is both illegal and highly stigmatized. This low rate of pharmacologic intervention may also reflect hesitation on the part of clinicians to prescribe medications for kleptomania in the absence of strong evidence from double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Alternately, this finding may point to a potential bias against a biological explanation for the disorder and toward a more psychological formulation that suggests that psychotherapy is the treatment of choice.

Our results also underline the high emotional and professional costs this disorder levies on the individual: arrests, jail time, disrupted relationships, and blighted careers.

Like subjects in another series,4 our interviewees who received individual or group psychotherapy aimed at kleptomania experienced no sustained benefits. Various psychodynamic and behavior therapy approaches have been utilized to treat kleptomania but with inconsistent success.9 Covert sensitization, where the patient is instructed to imagine himself or herself stealing and then to imagine a negative outcome such as being caught or feeling nauseous or short of breath, has been reported to be helpful in at least 3 cases.10,11,12 Imaginal desensitization was used successfully in 2 other patients.13 This technique involves helping the patient achieve a relaxed state through progressive muscle relaxation and asking the patient to imagine the different steps of the stealing episode, meanwhile suggesting that he or she could better control the urge to steal by controlling the anxiety. In the absence of controlled trials, we favor using cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques that encourage resisting the impulse, teach methods for reducing the accompanying anxiety, and highlight the consequences of the kleptomanic behavior.

Case reports and open-label trials using medications including naltrexone, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, topiramate, valproic acid, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, trazodone, and buspirone have yielded mixed results.9,14–17 Given the success in double-blind placebo-controlled trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of other impulse control disorders,18–20 it is plausible that kleptomania may be similarly responsive. We are currently conducting the first double-blind placebo-controlled trial to test this hypothesis, using the SSRI escitalopram.

One reasonable pharmacologic approach would be to start an SSRI and gradually increase the dose to the maximum comfortably tolerated dose consistent with U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved use. If no response is seen after 8 weeks of treatment at this dose, the literature suggests that switching to or augmenting with the narcotic antagonist naltrexone may be beneficial. In a 12-week open-label study testing naltrexone,16 25 to 200 mg/day, in 10 subjects with kleptomania, 9 participants responded, as reflected in a “much improved” or “very much improved” rating on the Clinical Global Impressions scale. However, given its potential for hepatic toxicity, it is advisable to avoid naltrexone in patients with significant liver pathology and to monitor liver function tests at baseline and during treatment.21

CONCLUSION

Kleptomania has many victims: the patient, the family, the person or institution stolen from, and society at large, which incurs a burdened legal system and an inflated price of goods. Given the secrecy and embarrassment that surround it, kleptomania often goes undiagnosed. General medical practitioners have a unique opportunity to screen for this illness, thus helping to prevent what is frequently a lifetime of symptoms. While collecting the social history, inserting a neutral question about any present or past legal troubles may be sufficient to offer clues to the diagnosis and prompt a psychiatric referral. Additional questions could inquire into “recurrent, disturbing urges to take things that don't belong to you.” Empathy, careful diagnosis, and early intervention are crucial if we are to mitigate the considerable personal, legal, and economic costs of kleptomania. Research comparing various psychotherapy and medication approaches to treating this disorder is clearly needed. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials should be conducted to test the relative effectiveness of various medications, particularly serotonergically active drugs that have been shown to be effective in other disorders of impulse control.18–20

Drug names: buspirone (BuSpar and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), lithium (Lithobid, Eskalith, and others), naltrexone (Revia and others), sertraline (Zoloft), topiramate (Topamax), trazodone (Desyrel and others), valproic acid (Depakene and others).

Footnotes

This article was supported by a grant from Forest Laboratories, New York, N.Y.

Dr. Aboujaoude has received honoraria from and serves on the speakers or advisory board for Forest. Dr. Koran has received grant/ research support from Forest, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca and honoraria from Forest. Ms. Gamel has received grant/research support from Forest.

REFERENCES

- McElroy SL, Hudson JI, and Pope HG. et al. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology. Psychol Med. 1991 21:93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986–996. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.8.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Pope HG, and Hudson JI. et al. Kleptomania: a report of 20 cases. Am J Psychiatry. 1991 148:652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger RC, Davis JL. 2002 National Retail Security Survey Final Report. Gainesville, Fla: University of Florida. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: The Compulsion to Steal—What Can Be Done? Far Hills, NJ: New Horizon Press. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Grant ME, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients with kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:378–384. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.34628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presta S, Marazziti D, and Dell'Osso L. et al. Kleptomania: clinical features and comorbidity in an Italian sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2002 43:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koran LM. Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders in Adults. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Guidry LS. Use of a covert punishing contingency in compulsive stealing. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1975;6:169. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier J, Pellerin D. Management of compulsive shoplifting through covert sensitization. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982;13:73–75. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keutzer C. Kleptomania: a direct approach to treatment. Br J Med Psychol. 1972;45:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1972.tb02194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConaghy N, Blaszczynski A. Imaginal desensitization: a cost effective treatment in two shoplifters and a binge-eater resistant to previous therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1988;22:78–82. doi: 10.1080/00048678809158945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durst R, Katz G, Knobler HY. Buspirone augmentation of fluvoxamine in the treatment of kleptomania. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:586–588. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Low BL. Treatment of kleptomania with fluvoxamine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:314–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:349–356. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannon PN. Topiramate for the treatment of kleptomania: a case series and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:1–4. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200301000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MR, Elliott M, and Thompson H. et al. Fluoxetine in pathological skin picking: open-label and double-blind results. Psychosomatics. 2001 42:314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Grant JE, and Adson DE. et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koran LM, Chuong HW, and Bullock KD. et al. Citalopram for compulsive shopping disorder: an open-label study followed by double-blind discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64:793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verebey KG, Mule SJ. Naltrexone (Trexan): a review of hepatotoxicity issues. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]