Abstract

This Academic Highlights section of The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the teleconference “Enhancement of Treatment Response in Depression” held May 18, 2004, and supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Cephalon, Inc. This meeting report was prepared by Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Monoamines, Neuropeptides, and Neurotrophins

Kerry J. Ressler, M.D., Ph.D., began his discussion by stating that major depressive disorder is a common syndromal disorder associated with extreme morbidity and mortality. Physicians should view depression as a result of dysfunctioning brain circuits.

The monoamines serotonin and nor-epinephrine are crucial regulators of a plethora of behaviors ranging from stress response to concentration, Dr. Ressler explained. Likewise, the neuropeptide corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is associated with behavior-specific neuronal circuits. Recent evidence also suggests that another neuropeptide, hypocretin, may play a role in depression, specifically in regard to the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle. Abnormalities of neurotrophins and brain-tissue development have been linked to depressive disorder as well, added Dr. Ressler.

Monoamines

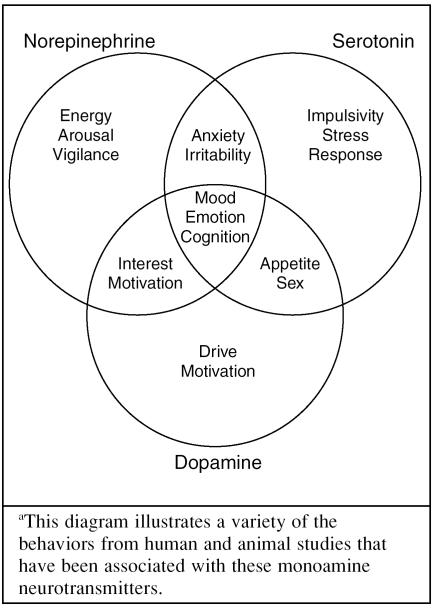

Dr. Ressler explained that the monoamines dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin regulate the broad functioning of brain circuits (Figure 1) and are produced in the ascending arousal system. While some of the roles that these monoamines play in the functioning of the brain are well-understood—for example, the role of dopamine in motivation—other roles are more speculative, such as the role of serotonin in impulsivity.

Figure 1.

Roles of the Monoamines in the Braina

However, Dr. Ressler commented, norepinephrine and serotonin dysregulation are known to play a crucial role in the development of depressive disorder. Depression has been found to be not only a result of dysregulation in either the norepinephrine or serotonin system, but also a result of disturbances in the balance between these 2 neuro-transmitters.1

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is involved in the arousal, vigilance, and stress response systems of the brain2 and is characterized by burst firing when the brain switches from a calm wakeful state to one of vigilance and attention.

Dr. Ressler remarked that in depression, the norepinephrine system probably does not involve a gross increase or decrease in static levels of neuro-transmission, but rather a dysregulation of dynamic levels of neurotransmission. Evidence3,4 suggests an overactivation of norepinephrine release and/or hypersensitivity of the norepinephrine systems in depression.

Dr. Ressler added that levels of tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme required for the production of norepinephrine, may be a marker for norepinephrine dysregulation. In one study,3 tyrosine hydroxylase protein levels were measured in the postmortem brains of 13 people with depression and 13 age-matched controls. Tyrosine hydroxylase levels were found to be elevated among depressed patients, suggesting either a premortem overactivity of tyrosine hydroxylase or a deficiency in norepinephrine.

Serotonin

In contrast to norepinephrine's burst firing activity, serotonin's activity in the brain is characterized by a relatively slow rhythmic pattern—only a few times per second—explained Dr. Ressler. The serotonin system is thought to be associated with quiet, internally directed activity and inhibited by behavioral orientation and vigilance. For example, in an electrophysiologic study5 of the raphe nucleus of cats, the cat's dorsal raphe nucleus serotonergic neurons were activated when the cat was grooming itself. However, when a door was opened or shut, the cat's internally directed grooming behavior stopped, and the raphe appeared to completely shut off.

Studies1,4 suggest that patients with depression and anxiety have decreased levels of serotonin and its metabolites. In a study by Geracioti and colleagues,1 control subjects with high levels of norepinephrine had relatively low levels of serotonin, and vice versa, consistent with inverse correlation of raphe firing with locus ceruleus activity. In contrast, in patients with depression, such a correlation was absent, consistent with a dysregulation in the coordinated activity between these 2 monoamine neurotransmitter systems.

Neuropeptide Systems

Neuropeptides mediate behavior-specific components of neural circuits, continued Dr. Ressler. Specific neuropeptides such as CRH have been associated with the dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal stress axis and depression. However, Dr. Ressler added, other neuropeptides such as hypocretin have been discovered that may play a crucial role in depression, particularly in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone

CRH is released from the hypothalamus and increases adrenocorticotropic hormone release from the pituitary gland. CRH helps modulate norepinephrine by increasing cortisol release from the adrenal gland, which, in turn, increases norepinephrine release from the locus ceruleus. Also, CRH-producing neurons project directly from the amygdala to the locus ceruleus.6 Dr. Ressler remarked that patients with depression have increased levels of CRH when compared with non-depressed participants.7,8

Hypocretin

Hypocretin, a recently discovered neuropeptide, is released from the hypothalamus into monoamine systems mediating arousal. Hypocretin is required for normal modulations of sleep and wake cycles.

Patients with depression have been found to have significantly less peak-to-trough hypocretin variations.6 Dr. Ressler mentioned that this evidence suggests that some neuropeptides may mediate the symptoms of sleep-wake disruption in some subtypes of depression.

Neurotrophins and Neuroplasticity

Neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are thought to be involved in enhancing neuroplasticity and enhancing the number of neurons that are born within the hippocampus. Mood disorders such as depression are associated with impairments of structural plasticity and cellular resistance, explained Dr. Ressler.9

CRH has also been found to be involved in the modulation of neuroplasticity. Studies10,11 have repeatedly found that patients with depression have a decrease in hippocampal size when compared with control participants. Elevated CRH and/or cortisol may contribute to decreased hippocampal size through increased atrophy and cell death in combination with diminished cellular resiliency that may occur with abnormal BDNF function.

Chronic Antidepressant Treatment

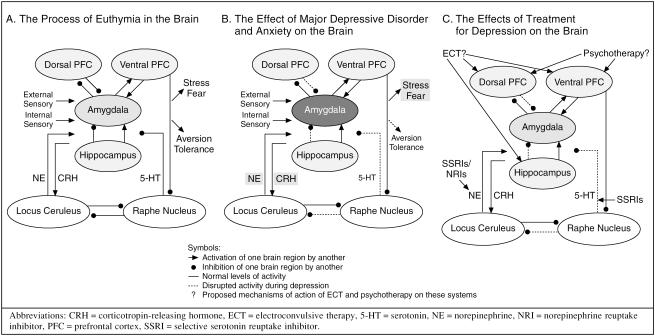

Dr. Ressler stated that, in euthymia, the amygdala's role is to compare external sensory and internal memory events. This process occurs through an interaction among the amygdala, hippocampus, locus ceruleus, raphe nucleus, and the dorsal and ventral prefrontal cortices. The pathways involved are modulated by norepinephrine, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing hormone (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Brain Processes in Patients With Euthymia, Untreated Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety, or Treated Depression

However, in the brain of patients with depression, the amygdala appears to be hyperactive, and other areas of the brain malfunction (Figure 2B). The amygdala responds to external sensory information as being more stressful than usual. Therefore, antidepressant treatments function by correcting disrupted circuits in these areas of the brain, summarized Dr. Ressler (Figure 2C).

Monoamines

Dr. Ressler noted that antidepressant treatment can regulate norepinephrine levels and increase serotonin levels.

Normalizing norepinephrine levels may be possible by decreasing tyrosine hydroxylase levels. Nestler and colleagues12 found that total levels of tyrosine hydroxylase proteins were decreased in the brains of rats treated with nortriptyline, a norepinephrine-specific agent; electroconvulsive therapy, a panmonoamine treatment; fluoxetine, an inhibitor of serotonin re-uptake; and bupropion. However, haloperidol, diazepam, and morphine were found to have no effect on tyrosine hydroxylase levels. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment has been found to increase serotonin levels in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and frontal cortex of patients with depression.13

Neurotrophins

In patients with depression, there is a decrease in neuroplasticity and BDNF release, reviewed Dr. Ressler. In a postmortem study,14 increased BDNF release was found in subjects treated with antidepressants when compared with untreated subjects.

Dr. Ressler remarked that hippocampal neurogenesis may be required for antidepressant efficacy.15 Chronic antidepressant treatment has been found to increase cell numbers in the hippocampus as well as to increase outgrowth of neuronal processes.16

Conclusion

Dr. Ressler summarized that monoamines regulate multiple broad systems including stress, fear, and arousal circuits; neuropeptides mediate behavior-specific circuits such as wakefulness; and neurotrophins allow for plasticity and maintenance of neural circuits.

By understanding the roles these brain circuits play in depression, clinicians can develop a better understanding of response and remission, remarked Dr. Ressler. Remission from major depression occurs when the correction of one disrupted circuit leads to the correction of the other circuits. Hence, resistance or partial response occurs when one disrupted circuit is corrected, but other circuits fail to normalize.

REFERENCES

- Geracioti TD Jr, Loosen PT, and Ekhator NN. et al. Uncoupling of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in depression: preliminary evidence from continuous cerebrospinal fluid sampling. Depress Anxiety. 1997 6:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Chiang C, Alexinsky T. Discharge of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats and monkeys suggests a role in vigilance. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:501–520. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63830-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MY, Klimek V, and Dilley GE. et al. Elevated levels of tyrosine hydroxylase in the locus coeruleus in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1999 46:1275–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12(suppl 1):2–19. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<2::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornal CA, Metzler CW, and Marrosu F. et al. A subgroup of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons in the cat is strongly activated during oral-buccal movements. Brain Res. 1996 716:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purba JS, Raadsheer FC, and Hofman MA. et al. Increased number of corticotropin-releasing hormone expressing neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuroendocrinology. 1995 62:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raadsheer FC, Hoogendijk WJ, and Stam FC. et al. Increased numbers of corticotropin-releasing hormone expressing neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of depressed patients. Neuroendocrinology. 1994 60:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB, Widerlov E, and Bissette G. et al. Elevated concentrations of CSF corticotropin-releasing factor-like immuno-reactivity in depressed patients. Science. 1984 226:1342–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji HK, Duman RS. Impairments of neruoplasticity and cellular resilience in severe mood disorders: implications for the development of novel therapeutics. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35:5–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M, and Andersen E. et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 157:115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YL, Wang PW, and Gado MH. et al. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 93:3908–3913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, McMahon A, and Sabban EL. et al. Chronic antidepressant administration decreases the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat locus coeruleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 87:7522–7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, Bouchard C. Modulation of 5-HT release in the guinea-pig brain following long-term administration of antidepressant drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:485–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Dowlatshahi D, and MacQueen GM. et al. Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol Psychiatry. 2001 50:260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L, Saxe M, and Gross C. et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003 301:805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS. Synaptic plasticity and mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(suppl 1):S29–S34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pharmacologic Approaches to the Management of Residual Symptoms in Major Depressive Disorder

Maurizio Fava, M.D., stated that major depressive disorder is frequently underrecognized and undertreated in the primary care setting despite its relatively high prevalence.1 One reason for the lack of recognition of depression is that the full spectrum of depression symptomatology is largely unacknowledged in depression classification and rating scales. However, recognition of these symptoms is crucial to depression treatment, because many of these symptoms persist despite adequate antidepressant therapy, asserted Dr. Fava.

Recognizing Symptoms of Depression

Major depressive disorder is typically thought to consist of primarily psychological symptoms (such as depressed mood, feelings of guilt, or indecisiveness), and this idea is reflected in the DSM-IV-TR classification of depression.2 However, Dr. Fava stated, major depressive disorder should be thought of as including a constellation of symptoms across 3 domains: psychological, behavioral, and somatic (Table 1). Somatic and behavioral symptoms are often overlooked in the recognition of depression and treatment, in part because the DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder list 6 psychological symptoms and 3 somatic symptoms; 1 psychological symptom can be seen as a behavioral symptom as well.

Table 1.

Common Symptoms of Unipolar Depressiona

Dr. Fava emphasized that clinicians need to be aware of the psychological, behavioral, and somatic symptoms of depression to adequately address patients' needs. He explained that the clinician and patient perspectives often differ. Clinicians have been taught to treat the disorder itself, but patients are often more concerned with the alleviation of symptoms. However, psychiatry is shifting toward a treatment approach that focuses more on the symptoms of depression rather than the syndrome of depression.

When targeting specific symptoms or symptom domains, clinicians need to assess the effects of treatment. Dr. Fava explained that, unfortunately, the instruments that are typically used are somewhat limited. For example, clinician-rated instruments such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D),3 the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),4 and the Inventory for Depression Symptomatology5 are useful scales, but these scales reflect DSM nosology and focus primarily on psychological symptoms. These scales do not fully cover all the current DSM symptoms for major depressive disorder and only partially measure somatic symptoms.

Similar problems are also encountered when using patient-rated instruments such as the Beck Depression Inventory,6 HANDS,7 and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale,8 which are all heavily weighted to measure psychological symptoms.

Response and Residual Symptoms

Although the currently available instruments are limited in their capacity to measure all 3 symptom domains, they can be used to classify symptom improvement of patients being treated for depression. Clinical studies, Dr. Fava related, tend to divide treatment outcome into 3 groups on the basis of the degree of symptom impairment: nonresponse, partial response, and response. All categorizations assume an adequate antidepressant trial in terms of both dose and time. The first category, nonresponse, describes patients who experience < 25% improvement in depressive symptoms as measured by a rating scale. Partial response typically indicates a clinically significant improvement that is not robust, such as a 25% to 50% improvement on rating scale score, but marked with residual symptoms. Response describes patients who experience a robust improvement, i.e., ≥ 50% improvement according to the rating scale score with mild residual symptoms.

Even patients whose depression is described as being in remission, i.e., the return to premorbid functioning, can experience some residual symptoms. Dr. Fava noted that remission is not reached frequently enough. In a review of 36 clinical trials of antidepressants, Fava and Davidson9 found that many of the reviewed studies reported that 50% or more of patients were partial or nonresponders.

Residual symptoms among responders are also prevalent. Patients who achieve full remission have significantly fewer days missed from work than nonremitters.10 For example, Nierenberg and colleagues11 assessed the presence and number of residual symptoms in 108 full responders (HAM-D scores ≤ 7, which is considered remission in many studies) to fluoxetine treatment. Fewer than 20% had no residual symptoms, and over half had 2 or more symptoms.

The importance of residual symptoms has been demonstrated, according to Dr. Fava. For example, Paykel and colleagues12 have shown that relapse and recurrence are less likely in patients without residual symptoms (25%) than in patients with residual symptoms (76%). According to a long-term study by Judd and coworkers,13 patients who had subthreshold residual symptoms were more likely to experience relapse or recurrence, relapsed more quickly, and had shorter well intervals than did recovered patients without residual symptoms.

Types of Residual Symptoms

Some residual symptoms are more common than others, stated Dr. Fava. For example, anxiety is a common residual symptom in depression,14 and in a study15 of elderly patients with depression, those who were still anxious at the time of remission had a shorter time to relapse or recurrence than non-anxious patients.

Somatic symptoms are common residual symptoms as well. Denninger and colleagues16 have found that residual somatic symptoms are significantly more common in responders who have not remitted than in remitters. Sleep disturbances may also linger among responders to antidepressant treatment, as Nierenberg and coworkers11 found. In a study by Reynolds et al.,17 patients who received maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy and had good sleep quality were more likely to remain well for at least 1 year (90%) compared with those with residual poor sleep quality (33%).

The presence of residual symptoms may be due to conditions other than depression, explained Dr. Fava, and a careful differential diagnosis is essential. Fatigue, for example, may be due to hyperthyroidism. Antidepressant-induced adverse effects may also cause a variety of symptoms that could be misinterpreted as residual symptoms of depression such as sleepiness, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and apathy. Clinicians should try to distinguish residual symptoms from psychiatric or medical comorbidity or medication side effects.

Achieving Remission and Managing Residual Symptoms

Several strategies can be used to help patients achieve remission (Table 2). Dr. Fava reviewed management strategies for 2 common residual symptoms: anxiety and hypersomnia/ fatigue.

Table 2.

Strategies to Enhance the Chances of Achieving Remission of Depression

Anxiety

When a patient presents with anxiety as a residual symptom or as a side effect, the physician may want to consider switching to a more sedating antidepressant. However, switching treatment may sometimes be inappropriate, since doing so may sacrifice the response a patient has already achieved. Clinicians may want to consider increasing the antidepressant dosage to levels higher than the ones used for depression.

Dr. Fava explained that polypharmacy is used more commonly to treat anxiety as a residual symptom or as a side effect. Although many of these treatments have not yet been approved for anxiety treatment, augmenting agents such as benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, and buspirone are common pharmacologic options. Concomitant psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, may also be helpful in managing anxiety, particularly in patients with comorbid panic disorder or phobias.

Hypersomnia and fatigue

In managing hypersomnia and fatigue in depression, Dr. Fava explained that the first step is to rule out concomitant substance abuse. Clinicians should then educate patients on proper sleep hygiene.

It is not uncommon for clinicians to experiment with the timing of antidepressant dosing to help patients sleep or, in the case of fatigue, to help patients be more alert, remarked Dr. Fava. Reducing the antidepressant dose or switching agents may help alleviate symptoms, but once again, physicians run the risk of losing efficacy when reducing or switching antidepressants.

If hypersomnia or fatigue is due to poor sleep quality, Dr. Fava recommended adjunctive treatments such as hypnotics or benzodiazepines. For hypersomnia or fatigue, psychostimulants, modafinil, bupropion, or a nor-epinephrine reuptake inhibitor such as atomoxetine may be prescribed.

Dr. Fava commented that many of these strategies are used in an off-label fashion and studies are clearly needed to prove their efficacy. Preliminary results from a study18 of modafinil as an adjunct to SSRIs found that nonresponsive or partially responsive patients experiencing persistent fatigue and sleepiness were significantly more improved after receiving modafinil according to Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale scores (p < .05 vs. placebo) than untreated patients. In addition, modafinil was associated with a significant decrease in mean scores on the “worst” item of the Brief Fatigue Inventory (p < .05 vs. placebo).

Conclusion

In conclusion, said Dr. Fava, incomplete response to antidepressant treatment is the rule, not the exception. Residual symptoms are common and may be psychological, behavioral, and/or somatic in nature. Clinicians use many augmentation strategies for the management of residual symptoms, but clearly, further studies are needed to assess the efficacy of these strategies.

REFERENCES

- Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosug Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg MC. A new depression rating scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Giles GE, and Schlesser MA. et al. The Inventory for Depression Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatr Res. 1986 18:65–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, and Mendelson M. et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 4:561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer L, Jacobs DG, and Meszler-Reizes J. et al. Development of a brief screening instrument: the HANDS. Psychother Psychosom. 2000 69:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Revicki D, and Heiligenstein J. et al. Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 22:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, and Leslie VC. et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 60:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Ramana R, and Cooper Z. et al. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995 25:1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Paulus MJ, and Schettler PJ. et al. Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? Am J Psychiatry. 2000 157:1501–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opdyke KS, Reynolds CF III, and Frank E. et al. Effect of continuation treatment on residual symptoms in late-life depression: how well is “well”? Depress Anxiety. 1996–1997 4:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AJ, Rifat SL. Two-year outcome of elderly patients with anxious depression. Psychiatry Res. 1997;66:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)02964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denninger JW, Mahal Y, and Merens W. et al. The relationship between somatic symptoms and depression. In: New Research Abstracts of the 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 21, 2002; Philadelphia, Pa. Abstract NR251:68. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CF III, Frank E, and Houck PR. et al. Which elderly patients with remitted depression remain well with continued interpersonal psychotherapy after discontinuation of antidepressant medication? Am J Psychiatry. 1997 154:958–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, De Battista C, and Thase ME. et al. Modafinil as augmentation agent in adults with major depressive disorder, sleepiness, and fatigue [poster]. Presented at the 42nd annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 7–11, 2003; San Juan, Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

The Brain and the Mind in Depression

Philip T. Ninan, M.D., discussed depression from the perspective of the brain and the mind. The brain is the organ at the core of mental disciplines, and without the brain there would be no mind. As an organ, the human brain is unique since the higher order of output influences its own functioning. For example, the mind has the executive capacity to make conscious, willful choices that can affect the functioning of the brain. Such systems-level knowledge is a necessary foundation to understand mental illnesses like major depression and to critically guide the prescription of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic treatments.

Heterogeneity of Major Depression

Major depression is a clinical label. The DSM-IV diagnosis1 requires a minimum 2-week period of at least 5 of 9 symptoms, one being either sadness or anhedonia. Several subtypes of the disorder exist. In attempts to address this heterogeneity, 2 broad types have emerged with some regularity in the literature—the melancholic type with persuasive neurobiological evidence of deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, “stress” axis, and atypical depression marked by prominent anxiety, akin to major depression with a comorbid anxiety disorder. An overactive anxiety neurocircuit is suggested as the initiating pathophysiology in atypical depression, with the subsequent development of depression.2 Why is there not a one-to-one correlation between neurobiology and clinical presentations? For that, we have to examine the brain and its product, the mind.

The Brain as a Cartographer

One way to understand the brain's function is to see the brain as a cartographer. The brain functions by making internal maps of the external world. Such maps are patterns of neural activity that represent external reality, just like a conventional map is a pictorial representation of a geographical area.

The brain creates maps of the body through somatosensory and visceral representations. Somatosensory representations of the body are located in the parietal lobe, which straddles the parietal ridge, which represents different anatomical areas. The insular cortex represents information from the internal organs for a visceral map.3 The combination of the somatosensory and visceral representations forms the basis of the somatic self. Abnormal functioning in these maps can theoretically have profound influences. Somatic symptoms in illnesses like major depression may result from functional aberrations in somatic representations. In an extreme example, a seizure affecting the somatosensory cortex results in an individual's losing awareness of the body, a condition called asomatognosia.

The somatic representation of the self is a necessary foundation for the psychological self. Psychoanalytic theory argues that the psychological self is critically influenced by relationships, particularly early in development.4 For example, early in life, the mother-child relationship is potently internalized in the developing brain of the child. The infant has yet to form clear representations of its somatic boundaries and is strongly influenced by maternal emotions. With the development of representations of physical boundaries, the child experiences the self as separate and therefore independent. A failure of appropriate development in somatic representations may leave the individual without a sense of a stable psychic self. Such a person would be inordinately suggestible and excessively vulnerable to outside influences.

Perception and Response

The process in which the brain creates these internal maps begins with perception, continued Dr. Ninan. For perception to occur, sensory representations have to be selectively received or matched by complementary pre-existing internal templates.5,6 Subjective perception occurs when 2 visual representations coalesce—the “bottom-up” information coming through the retina to the occipital cortex, and the “top-down” information of the internal template perceiving the external information.

Perceptions evoke action. Actions can be reflexive (such as blink of an eye), automatic (such as emotion), or executive (such as cognition) as well as self-generated. A reflex reaction happens quickly and requires limited information processing, involving only a few synaptic connections. An evoked response beyond a reflexive one initially activates limbic sites where, if the input matches an internal template, it triggers an emotional response. The responses are broadly valued as positive or negative and emerge to subjective awareness as feelings. Negative emotions, triggered via the amygdala, include anxiety and sadness, whereas positive emotions include feelings of happiness and pleasure.7

The Nature of Emotions

Emotions are automatic and occur with activity in the limbic circuits prior to conscious awareness. Emotions are triggered preconsciously and cannot be willfully chosen. What is within volition, however, is whether an individual executively agrees with the emotion experienced and subsequently chooses to inhibit or intensify the emotion. Decisions based on emotions are intuitive because they are not deliberate. Given the complex and differential time frames for emotions, cognitive processing, and conscious awareness, such emotional decisions are vulnerable to post hoc rationalization.

Intense emotions are experiential, global, and overpowering because they are indelibly tied to the body. Intense emotions drive cognitions and behavior.8 They diminish the individual's capacity to make independent observations or executive decisions. Emotions drain working memory capacity and the ability to plan a deliberate response. For example, anxiety experienced at an emotional level commands catastrophic cognitions, called worry. Likewise, positive emotions such as pleasure result in cognitions that are lavish and behaviors that are expansive and inclusive. Emotions also drive behavior—anxiety results in physical tension, restlessness, the desire to flee, or defensive aggression.

Emotions are associative, such that a current emotion is typically associated with other events that induced similar responses in the past. The lifespan of an experienced emotion generally stretches beyond the time frame of cognitive events, and residual emotions can influence subsequent events even if they are independent and unrelated. In anxiety, this association occurs when the information reaching the amygdala matches previously stored threat templates, a fixed action pattern from responses are activated such as fear of immediate physical threats or anxiety from anticipated psychological threats. The amygdala serves as a central command switch, which activates a cascade of events in the brain and body that enhance survival. Based on preclinical studies, negative emotional responses appear to be conditioned in 3 different ways: fear, contextual conditioning, and avoidance.9–11 Using the example of an individual's memory of being assaulted in an alley late at night, Dr. Ninan reviewed the different types of negative conditioning and the responses they evoke (Table 3).

Table 3.

Conditioning of a Negative Response: An Individual Assaulted Late at Night in an Alleya

Cognition

Cognition is the capacity to frame information in different contexts and change it proportionately so that the end product appears reasoned, balanced, and logical.7 Cognitive systems gather information about a current situation, apply relevant memories, run simulations of possible outcomes, frame information in the context of the self and its ideals and goals, and then choose a decision. Language allows cognitions to be nuanced, differentiated, and communicated. Cognitive processes allow human behavior to rise above predetermined responses and move toward willful choice.

Important neurobiological differences exist in the systems that underlie emotions and cognition. The neurocircuits mediating emotions are largely feed-forward systems, while cognition emerges from recursive circuits that prominently include feedback mechanisms. Thus executive functions move beyond the matching receptivity of representations that are at the core of emotions. Cognition has the ability to hold and process information in working memory, access relevant memories, and inhibit automatic responses for social or other reasons.

In major depression, cognitive processes lose their multifaceted abilities and become ruminatively repetitive, restricted in content, and focused on guilt, hopelessness, and death. Functional brain imaging studies support the postulated interactive relationship between emotions and cognition. Mayberg and colleagues12 used positron emission tomography to measure brain changes in healthy volunteers who were asked to recount sad personal experiences and depressed patients who were treated with fluoxetine. Sad memories in healthy subjects increased blood flow in critical emotional centers and decreased blood flow in executive regions that mediate cognitive processes. In successfully treated depressed patients, the opposite pattern was seen. These results suggest that with sadness or depression, overactivity of negative emotional systems is coupled with reduced executive and cognitive capacity. Successful pharmacologic treatment improves depressive symptoms and reestablishes the normal balance between emotions and cognition.

Mechanisms of Treatment Response

There are several ways to treat major depression to remission. Ninan posed the question, can an understanding of pathophysiology guide treatment choices? Antidepressant pharmacotherapy influences parts of the brain that may be overactive or oversensitized in depression, commented Dr. Ninan (Table 4). For example, inhibiting exaggerated negative emotional reactions through the amygdala may enable a depressed individual to override sadness and its associated ruminations. Increasing neurogenesis in the hippocampus might enhance working memory capacity so that a person is able to juggle more complex multiplex information simultaneously.

Table 4.

Possible Mechanisms of Response to Pharmacotherapy

Different forms of psychotherapy may have different mechanisms of action (Table 5). For example, the empathy perceived in supportive psychotherapy may engage circuits that represent social relationships; sharing and feeling emotionally connected to a compassionate individual may calm psychic distress. Psychodynamic psychotherapy may reawaken traumatic emotional memories so that they become labile again. In the current therapeutic context, an adult's knowledge can modify such memories during reconsolidation. The brain that now remembers the event is different from the brain that originally memorized the experience and the process of reconsolidation releases the traumatic memory from the emotions triggered during the trauma.

Table 5.

Possible Mechanisms of Action of Psychotherapy

Cognitive therapy allows the individual to alter the cognitive context, i.e., automatic assumptions and belief systems that perpetuate negative emotional responses. Framing experiences in a healthier, more rational context opens the depressed individual to a variety of potentially corrective processes. Behavioral treatments focus on avoidance using sustained exposure to generate extinction, a process by which new memories are formed with benign associations devoid of anxiety.

Conclusion

The human brain is a highly complicated structure, and much can go awry in it. Information is the currency of the brain: the processing of information generates perception, emotions, cognition, and behavior. The interaction of these brain functions and their dysregulation form the basis of mental illnesses such as major depression.

A healthy, nondepressed individual is free to override a negative emotional response with rational cognitions. A depressed individual appears to have lost that choice. Executive control has shifted to a more primitive emotional circuitry, leaving the individual captive to repetitive negative fixed-action patterns of behavior. Understanding the delicate balance between the brain and the mind, and the critical junctions at which abnormalities can occur, can provide a basis for appreciating how treatments work. Such knowledge arms the practicing clinician with the ability to intelligently prescribe treatments, whether pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy, most likely to successfully target the pathology underlying the illness.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Ninan PT, Berger J. Symptomatic and syndromal anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:79–85. doi: 10.1002/da.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel? interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Natl Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg OF. Objects-Relations Theory and Clinical Psychoanalysis. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Allman J, Miezin F, McGuinness E. Stimulus specific response from beyond the classical receptive field: neurophysiological mechanisms for local-global comparisons in visual neurons. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1985;8:407–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros JA, Forlano PM, and Deitcher DL. et al. Steroid-dependent auditory plasticity leads to adaptive coupling of sender and receiver. Science. 2004 305:404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan PT, Feigon SA, Knight B. Strategies for treatment-resistant depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36:S67–S78. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. San Diego, Calif: Harcourt. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- McKernan MG, Shinnick-Gallagher P. Fear conditioning induces a lasting potentiation of synaptic currents in vitro. Nature. 1997;390:607–611. doi: 10.1038/37605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. Fear and the brain: where have we been and where are we going? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1229–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Are different parts of the extended amygdala involved in fear versus anxiety? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, and Brannan SK. et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 156:675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drug names: atomoxetine (Strattera), bupropion (Wellbutrin and others), buspirone (BuSpar and others), diazepam (Diastat, Valium, and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), haloperidol (Haldol and others), modafinil (Provigil), morphine (Avinza, Oramorph, and others), nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor, and others).

Pretest and Objective

Instructions and Posttest

Registration and Evaluation

Footnotes

The teleconference was chaired by Philip T. Ninan, M.D., Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Ga. The faculty were Maurizio Fava, M.D., Depression Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Kerry J. Ressler, M.D., Ph.D., the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, and the Yerkes Primate Research Center, Atlanta, Ga.

Continuing Medical Education Faculty Disclosure

In the spirit of full disclosure and in compliance with all ACCME Essential Areas and Policies, the faculty for this CME activity were asked to complete a full disclosure statement.

Dr. Ninan is an employee of Emory University; is a consultant for Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest, Janssen, Solvay, Wyeth, and UCB Pharma; has received research grant support from Cephalon, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Forest, Janssen, and Glaxo; and has received honoraria from and is on the speakers or advisory board for Cephalon, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, and Wyeth. Dr. Fava has received research support from Abbott, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, and Lorex; has received honoraria from Bayer AG, Compellis, Janssen, Knoll Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, and Somerset; and has received both research grant support and honoraria from Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Organon, Pharmavite, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Solvay, and Wyeth. Dr. Ressler has received research grant support from Pfizer and has received honoraria from Cephalon.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CME provider and publisher or the commercial supporter.