Abstract

Objectives:

We developed a standardized cost estimation method for occupational health (OH) services. The purpose of this study was to set reference OH services costs and to conduct OH services cost management assessments in two workplaces by comparing actual OH services costs with the reference costs.

Methods:

Data were obtained from retrospective analyses of OH services costs regarding 15 OH activities over a 1-year period in three manufacturing workplaces. We set the reference OH services costs in one of the three locations and compared OH services costs of each of the two other workplaces with the reference costs.

Results:

The total reference OH services cost was 176,654 Japanese yen (JPY) per employee. The personnel cost for OH staff to conduct OH services was JPY 47,993, and the personnel cost for non-OH staff was JPY 38,699. The personnel cost for receipt of OH services-opportunity cost-was JPY 19,747, expense was JPY 25,512, depreciation expense was 34,849, and outsourcing cost was JPY 9,854. We compared actual OH services costs from two workplaces (the total OH services costs were JPY 182,151 and JPY 238,023) with the reference costs according to OH activity. The actual costs were different from the reference costs, especially in the case of personnel cost for non-OH staff, expense, and depreciation expense.

Conclusions:

Using our cost estimation tool, it is helpful to compare actual OH services cost data with reference cost data. The outcomes help employers make informed decisions regarding investment in OH services.

Keywords: Costs and cost analysis, Cost management, Economic evaluation, Occupational health services, Reference cost

Introduction

Occupational health (OH) services are a part of a business's activities. Employers make the final decisions about OH services and are ultimately responsible for the implementation of OH services. To determine the appropriate allocation of investment in OH services, employers consider the current health risks of their employees and the possible impact of these health risks on business (for example, on productivity) and judge the priority of OH services by reference to OH services costs. This analysis is required, as costs are an important driver for all business decisions1). The cost of OH services is not a wasted expense but instead is an investment in the human resources of companies2). Investment in OH services as part of human resource management has great potential value to a business and may aid in the business's future competitiveness3). However, few companies apply systematic, continuous, and strategically aligned OH services cost management procedures3).

For strategic cost management, a business has to conduct a cost calculation4). We developed a standardized cost estimation tool to calculate actual OH services costs, from an employers' perspective, based on an activity-based costing method and published the results in a previous article5). In activity-based costing, cost estimations are generated according to activity6). This allows employers to know both the total OH services cost and a detailed breakdown of the OH services costs by OH activity, which is the first step in cost management.

The second step is cost variance analysis, which is a comparison of actual costs with the reference costs4). In general, a reference cost is calculated according to the length of time and price of a standard work process6). Cost management is the process of identifying the causes of variances between reference costs and actual costs and introducing measures to improve them. In the healthcare field, many hospitals compare actual costs with reference costs to improve work processes in the hospital7). Reference costs are calculated by a diagnosis procedure combination because they are created according to standard medical treatment processes8). At the time of this study, there was no standard OH services process that had gained consensus in society. Because of this, reference costs had to be calculated as the OH services costs in a workplace where OH activities were accepted as good practice.

The purposes of this study were to establish reference OH services costs based on one Japanese manufacturing company where OH activities were accepted as best practice and to conduct OH services cost management in two workplaces by comparing the actual OH services costs to the reference costs.

Subjects and Methods

Definition of OH services cost

In this study, we calculated the actual cost that was expended for all OH activities from a corporate perspective. The Health Insurance Society, which must endeavor to provide services consisting of health education, health counseling, health checkups, and other services necessary to maintain and promote the health of insured persons by Japanese laws-Health Insurance Act, National Public Officers Mutual Aid Association Act, Local Public Service Mutual Aid Association Act, Mariners Insurance Act, and National Health Insurance Act-often provides a wellness program in occupational settings in Japan, but the cost of this program was outside the coverage of this study because the Health Insurance Society is a separate organization, that is not part of the companies to which it provides services. Some studies have added costs of health-related productivity loss to the total OH services cost9,10). We did not follow that procedure in this study because we considered health-related productivity loss to be a consequence of OH services.

Employees received OH services during their working hours, so from a corporate perspective, their personnel cost for hours receiving OH services-the opportunity cost-was part of the OH services costs. This study is the first trial to estimate the total OH cost including opportunity cost.

How to estimate OH services costs

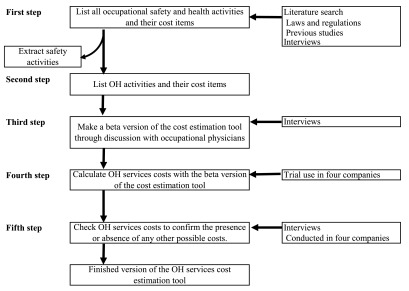

We developed a standardized cost estimation tool and reported the detailed process in a previous paper5). The development process is shown in Fig. 1. First, we listed all occupational safety and health activities and identified the management resources (production, human, and financial resources) required in each activity through a literature search and interviews. Second, we listed OH activities and the cost items, which were extracted from all occupational safety and health activities and the cost items. Third, we interviewed three occupational physicians to discuss practical methods for calculating OH costs. We then made a beta version of the cost estimation tool. Fourth, occupational physicians calculated OH services costs with the cost estimation tool by communicating with other occupational safety and health staff, human resources, and financial departments in four companies. We chose four workplaces by using the following three selection criteria: 1. OH services were implemented based on an occupational safety and health management system, 2. A sufficient number of experienced OH professionals conducted OH services, and 3. occupational physicians were qualified as Senior Occupational Health Physicians certified by the Japan Society for Occupational Health. Fifth, we interviewed occupational physicians in the four companies to confirm the presence or absence of any other possible costs.

Fig. 1.

Development process of the OH services cost estimation tool. OH=occupational health.

In this paper, we show the OH services cost structure for three (workplaces A, B, and C) out of the four workplaces because we could not estimate the actual OH services costs in one workplace due to a lack of personnel cost data as a result of the policy of the company regarding protection of confidential information.

The OH services cost estimation tool is divided into three parts: basic information, personnel cost for OH staff, and cost of each activity. The first part of the tool includes basic information. Basic information of the three workplaces is shown in Table 1. All companies were manufacturers listed in the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. There were 1,370 employees in workplace A, 1,080 employees in workplace B, and 223 employees in workplace C. The cost estimation period was one year: from 1 April 2010 to 31 March 2011 in workplace A, from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2010 in workplace B, and from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2010 in workplace C. OH services in workplace A were conducted by a full-time occupational physician, three OH nurses, and three health officers. OH services in workplace B were conducted by a full-time occupational physician, two OH nurses, and two industrial hygienists. OH services in workplace C were conducted by a part-time occupational physician and one part-time OH nurse with one full-time occupational physician's assistance. We required the personnel cost per person per hour for calculating opportunity cost. Although we could not determine opportunity cost from business accounting records, we could estimate the opportunity cost using our cost estimation tool.

Table 1.

Basic information about workers, the cost estimation period, and the mean personnel costs per person per hour from three manufacturing workplaces (A, B, and C). Costs are shown in Japanese yen. One euro was equivalent to 125.20 Japanese yen and one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 93.38 Japanese yen in April 2010. JPY=Japanese yen.

| Workplace A | Workplace B | Workplace C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of workers | 1,370 | 1,080 | 223 | |

| Males (number/%) | 1,200/87.6 | 1,026/95.0 | 215/96.4 | |

| Females (number/%) | 170/12.4 | 54/5.0 | 8/3.6 | |

| Managers (number/%) | 220/19.1 | 105/10.8 | 40/21.9 | |

| Non-managers (number/%) | 1,150/80.9 | 975/89.2 | 183/78.1 | |

| Cost estimation period | ||||

| From | 1 April 2010 | 1 January 2010 | 1 April 2009 | |

| To | 31 March 2011 | 31 December 2010 | 31 March 2010 | |

| Mean personnel cost per person per year (JPY) | 9,400,000 | 6,004,720 | 7,461,883 | |

| Mean personnel cost per person per hour (JPY) | ||||

| All employees | 5,000 | 3,194 | 3,831 | |

| Managers | 6,000 | 5,000 | 6,081 | |

| Rank-and-file employees | 4,800 | 3,000 | 3,378 | |

The second part of the tool includes the personnel cost for OH staff. For estimating the personnel cost, we required information on the number of OH staff, their personnel cost, and their proportion of time engaged in OH services.

The third part of the tool includes the cost of each OH activity. The cost of each activity include its expense, depreciation expense, outsourcing cost, and opportunity cost. We divided OH services into 15 activities. These were emergency response and support; equipment and fixtures; working environment measurement and exposure measurement; health checkup; health management; mental health countermeasures; operation of the occupational health department; health promotion and welfare; management of occupational health activities; licensing, skill training courses, etc.; health education as required by law; meetings; patrols; occupational accidents and injuries; and other.

Setting the reference OH services costs

In accounting for cost management, employers compare the actual costs with the reference costs in the case of best practice, explore the reason for any variance, and improve their activities. In this study, we set the reference OH services costs for conduct of OH services cost management.

Reference costs are generally estimated by the cost structure of a best practice organization, not the average costs. We defined three selection criterion for an organization where OH activities were accepted as best practice. First, the process of providing OH services was that considered to be the best practice. OH services in three workplaces were based on occupational safety and health management system, and workplaces A and C had obtained OHSAS 18001 certification. Second, the health outcomes of employees were good. We could not obtain information about health outcomes in this study. Third, there were no exceptional circumstances influencing the cost structure. In workplace B, industrial hygienists conducted OH services. That is uncommon. In workplace C, a fatal accident had occurred in the year preceding cost estimation. That affected the cost structure. We set the OH services costs of workplace A as the reference costs.

We calculated the OH services cost per OH activity in workplace A and created a cost structure as a cost coefficient table.

OH services cost management in two workplaces

We calculated the actual OH services costs per OH activity in workplaces B and C. We allocated the actual total OH services costs of workplace B and C to each OH activity by using the allocation rates of workplace A as the reference rates. Our researchers compared the actual OH services costs to the reference costs and discussed reasons for any variance.

Methodological quality of cost analysis in economic evaluation

We used the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC-list) to methodically judge the quality of the cost analysis11-13). As the costing period was only one year, no discounting was required and no discount was applied for inflation. We did not conduct either an incremental analysis or a sensitivity analysis because we had calculated the actual OH services costs of all OH activities.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medicine and Medical Care, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan.

Results

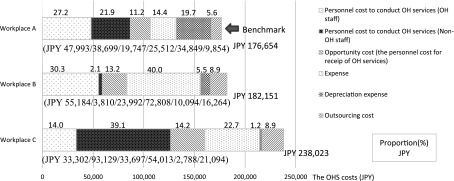

Actual OH services costs in workplace A are shown in the cost coefficient table in Table 2. The total OH services cost per employee was 176,654 Japanese yen (JPY). The personnel cost for OH staff to conduct OH services and the proportion of the total OH services cost were JPY 47,993 and 27.2%, respectively. The personnel cost for non-OH staff to conduct OH services and the proportion of the total OH services cost were JPY 38,699 and 21.9%, respectively. The personnel cost for receipt of OH services (the opportunity cost) and proportion of the total OH services cost were JPY 19,747 and 11.2%, respectively. The expense, depreciation expense (investment), and outsourcing cost, and the proportions of the total OH services cost were JPY 25,512, JPY 34,849, and JPY 9,854 and 14.4%, 19.7%, and 5.6%, respectively.

Table 2.

Actual OH services costs in workplace A. This table is shown as a cost coefficient table. Costs are shown in Japanese yen. One euro was equivalent to 125.20 Japanese yen and one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 93.38 Japanese yen in April 2010. OH=occupational health; JPY=Japanese yen.

| Personnel cost of OH services | Expense | Depreciation expense | Outsourcing cost | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel cost to conduct OH services | Personnel cost for receipt of OH services | ||||||||||||

| OH staffa | Non-OH staff | Opportunity cost | Expense | Depreciation expense (investment) | Outsourcing cost | Totalb | |||||||

| Item of OH activities | JPY | % | JPY | % | JPY | % | JPY | % | JPY | % | JPY | % | |

|

aWe did not conduct a time study of OH staff, so we did not allocate the personnel cost of OH staff to each OH activity.

bWe did not calculate the amount of the personnel cost of OH staff per OH activity, so we did not show the total cost per OH activity. | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emergency response and support | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 315 | 0.2 | 80 | 0.0 | 58 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 2. Equipment and fixtures | .. | 1,752 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,861 | 1.1 | 32,564 | 18.4 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 3. Working environment measurements, exposure measurements | .. | 631 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6,387 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 438 | 0.2 | .. | |

| 4. Health checkup | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 10,071 | 5.7 | 146 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 7,664 | 4.3 | .. | |

| 5. Health management | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 7,312 | 4.1 | 223 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 6. Mental health countermeasures | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 1,532 | 0.9 | 73 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 511 | 0.3 | .. | |

| 7. Operation of occupational health department | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4,270 | 2.4 | 2,226 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 8. Health promotion and welfare | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 307 | 0.2 | 1,350 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 146 | 0.1 | .. | |

| 9. Management of occupational health activities | .. | 7,717 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 438 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,095 | 0.6 | .. | |

| 10. Licensing, skill training courses, etc. | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 172 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 11. Health education designated by law | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 210 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 12. Meetings | .. | 27,270 | 15.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 13. Patrol | .. | 1,182 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 14. Occupational accidents and injuries | .. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10,438 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| 15. Other | .. | 147 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 73 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .. | |

| Cost per employee (JPY) and proportion (%) | 47,993 | 27.2 | 38,699 | 21.9 | 19,747 | 11.2 | 25,512 | 14.4 | 34,849 | 19.7 | 9,854 | 5.6 | 176,654 |

The details of the actual OH services cost per employee and proportions (%) of the total OH services costs in the three workplaces are shown in Fig. 2. The total OH services cost per employee was JPY 182,151 in workplace B and JPY 238,023 in workplace C. The personnel cost for receipt of OH services (opportunity cost) and the proportion of the total OH services cost were JPY 23,992 and 13.2% in workplace B and JPY 33,697 and 14.2% in workplace C.

Fig. 2.

Total actual OH services cost per employee in each workplace and the proportion of the personnel cost to conduct OH services, opportunity cost, expense, depreciation expense, and outsourcing cost. Costs are shown in Japanese yen. One euro was equivalent to 125.20 Japanese yen and one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 93.38 Japanese yen in April 2010. OH=occupational health; JPY=Japanese yen.

Table 3 shows a comparison of actual costs with reference costs in workplace B. For setting the reference cost of each cost item in workplace B, the actual total OH services cost of workplace B (JPY 182,151) was allocated based on the reference allocation rates of workplace A. The actual personnel cost to conduct OH services (OH staff) (JPY 55,184), personnel cost for receipt of OH services (opportunity cost) (JPY 23,992), expense (JPY 72,808), and outsourcing cost (JPY 16,264) were more than the reference costs (JPY 49,486, JPY 20,361, JPY 26,306, and JPY 10,161, respectively) in workplace B. In contrast, the actual personnel cost to conduct OH services (non-OH staff) (JPY 3,810) and depreciation expense (investment) (JPY 10,094) were less than the reference costs (JPY 39,903 and JPY 35,934, respectively).

Table 3.

Comparison of the actual OH services costs in workplace B to the reference cost. The reference costs were calculated by dividing the actual total OH services cost of workplace B in proportion to the OH services costs of workplace A, which was the benchmark. Costs are shown in Japanese yen. One euro was equivalent to 125.20 Japanese yen and one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 93.38 Japanese yen in April 2010. OH=occupational health; JPY=Japanese yen.

| Personnel cost of OH services | Expense | Depreciation expense | Outsourcing cost | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel cost to conduct OH services | Personnel cost for receipt of OH services | ||||||||||||

| OH staffa | Non-OH staff | Opportunity cost | Expense | Depreciation expense (investment) | Outsourcing cost | Totalb | |||||||

| Item of occupational health activities | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) |

|

aWe did not conduct a time study of OH staff, so we did not allocate the personnel cost of OH staff to each OH activity.

bWe did not calculate the amount of the personnel cost of OH staff per OH activity, so we did not show the total costs per OH activity. | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emergency response and support | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 325 | 1,084 | 83 | 443 | 60 | 563 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 2. Equipment and fixtures | .. | .. | 1,806 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 1,919 | 56,903 | 33,578 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 3. Working environment measurements, exposure measurements | .. | .. | 650 | 3,420 | 0 | 0 | 6,586 | 782 | 0 | 272 | 452 | 917 | .. |

| 4. Health checkup | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 10,384 | 18,011 | 151 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7,903 | 14,714 | .. |

| 5. Health management | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 7,540 | 3,297 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 6. Mental health countermeasures | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 1,579 | 1,350 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 527 | 633 | .. |

| 7. Operation of occupational health department | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,403 | 1,941 | 2,296 | 9,259 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 8. Health promotion and welfare | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 316 | 58 | 1,392 | 331 | 0 | 0 | 151 | 0 | .. |

| 9. Management of occupational health activities | .. | .. | 7,957 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 452 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,129 | 0 | .. |

| 10. Licensing, skill training courses, etc. | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 192 | 178 | 145 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 11. Health education designated by law | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 217 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 12. Meetings | .. | .. | 28,119 | 226 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 13. Patrol | .. | .. | 1,219 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 14. Occupational accidents and injuries | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,763 | 12,263 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 15. Other | .. | .. | 152 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| Cost per employee (JPY) | 49,486 | 55,184 | 39,903 | 3,810 | 20,361 | 23,992 | 26,306 | 72,808 | 35,934 | 10,094 | 10,161 | 16,264 | 182,151 |

With regard to opportunity cost in workplace B, the actual cost of emergency response and support (JPY 1,084) was about three times more than the reference cost (JPY 325). Many employees attended first aid trainings because there is a high risk of fire due to explosions in workplace B. The actual opportunity cost of health checkups (JPY 18,011) was substantially more than the reference cost (JPY 10,384). The expense of equipment and fixtures (JPY 56,903) was about 30 times more than the reference cost (JPY 1,919) because at least one respirator (chemical-cartridge or dust respirator) per employee was needed in workplace B. With regard to the outsourcing cost, the actual cost of health checkups (JPY 14,714) was more than the reference cost (JPY 7,903).

Table 4 shows a comparison of actual costs with reference costs in workplace C. For setting the reference cost of each cost item in workplace C, the actual total OH services cost of workplace C (JPY 238,023) was allocated based on the reference allocation rates of workplace A. The actual personnel cost to conduct OH services (non-OH staff) (JPY 93,129), personnel cost for receipt of receive OH services (opportunity cost) (JPY 33,697), expense (JPY 54,013), and outsourcing cost (JPY 21,094) were more than the reference costs (JPY 52,143, JPY 26,606, JPY 34,374, and JPY 13,277, respectively) in workplace C. In contrast, the actual personnel cost to conduct OH services (OH staff) (JPY 33,302) and depreciation expense (investment) (JPY 2,788) were less than the reference costs (JPY 64,666 and JPY 46,956, respectively).

Table 4.

Comparison of the actual OH services costs in workplace C to the reference cost. The reference costs were calculated by dividing the actual total OH services cost of workplace C in proportion to the OH services costs of workplace A, which was the benchmark. Costs are shown in Japanese yen. One euro was equivalent to 125.20 Japanese yen and one U.S. dollar was equivalent to 93.38 Japanese yen in April 2010. OH=occupational health; JPY=Japanese yen.

| Personnel cost of OH services | Expense | Depreciation expense | Outsourcing cost | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel cost to conduct OH services | Personnel cost for receipt of OH services | ||||||||||||

| OH staffa | Non-OH staff | Opportunity cost | Expense | Depreciation expense (investment) | Outsourcing cost | Totalb | |||||||

| Item of OH activities | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Reference cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) | Actual cost (JPY) |

|

aWe did not conduct a time study of OH staff, so we did not allocate the personnel cost of OH staff to each OH activity.

bWe did not calculate the amount of the personnel cost of OH staff per OH activity, so we did not show the total cost per OH activity. | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emergency response and support | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 425 | 4,847 | 108 | 1,300 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 2. Equipment and fixtures | .. | .. | 2,360 | 654 | 0 | 0 | 2,508 | 40,906 | 43,877 | 482 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 3. Working environment measurements, exposure measurements | .. | .. | 850 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8,606 | 359 | 0 | 0 | 590 | 4,175 | .. |

| 4. Health checkup | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 13,569 | 10,992 | 197 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,327 | 12,139 | .. |

| 5. Health management | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 9,852 | 4,519 | 300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 6. Mental health countermeasures | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 2,064 | 1,141 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 688 | 1,193 | .. |

| 7. Operation of occupational health department | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5,753 | 879 | 3,000 | 2,306 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 8. Health promotion and welfare | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 413 | 2,913 | 1,819 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 197 | 0 | .. |

| 9. Management of occupational health activities | .. | .. | 10,398 | 39,104 | 0 | 0 | 590 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,475 | 2,691 | .. |

| 10. Licensing, skill training courses, etc. | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 232 | 275 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 11. Health education designated by law | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 283 | 9,286 | 0 | 158 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 12. Meetings | .. | .. | 36,744 | 49,443 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 13. Patrol | .. | .. | 1,593 | 3,927 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 14. Occupational accidents and injuries | .. | .. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14,064 | 10,135 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .. |

| 15. Other | .. | .. | 198 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 897 | .. |

| Cost per employee (JPY) | 64,666 | 33,302 | 52,143 | 93,129 | 26,606 | 33,697 | 34,374 | 54,013 | 46,956 | 2,788 | 13,277 | 21,094 | 238,023 |

With regard to opportunity cost in workplace C, the actual costs of emergency response and support (JPY 4,847) and health education designated by law (JPY 9,286) were particularly more expensive than the reference costs (JPY 425 and JPY 283, respectively). In the year preceding cost estimation, there had been a fatal accident in workplace C. As a countermeasure, workplace C made a strong effort to improve training and management of occupational safety and health. They had also bought equipment and fixtures including personal protective equipment, so the actual expense (JPY 40,906) was about 16 times more expensive than the reference cost (JPY 2,508).

Discussion

Using our standardized cost estimation tool, we set the reference OH services costs based on the cost data in workplace A as a benchmark.

The reference OH services cost

We judged OH activities in workplace A as best practice and set the reference OH services costs based on workplace A. In workplace A, the personnel cost of OH staff per employee was JPY 47,993, and the proportion of the total OH services cost (JPY 176,654) was 27.2%. OH staff, experts in health care, play a large role in OH activities. A report published by International Social Security Association14) showed that the average personnel cost of in-house/external safety professionals, in-house/external occupational physicians, was 278 euro per employee (JPY 34,806 in April, 2010). Our study was confined to OH services that did not include occupational safety activities, so the personnel costs in workplace A were relatively high.

We considered the OH services costs as a human capital investment, so we compared the OH services costs with the annual personnel cost in workplace A. Total OH services cost/the annual corporate personnel cost (%) was JPY 176,654/JPY 9,400,000 (1.88%) per employee. There is no comparable data in the OH field to our knowledge. Education for workers is also regarded as a human capital investment within companies. The same benchmark was used for education: in-house education costs/payroll. The average direct expenditure for in-house education per employee is the ratio of how much an organization spends on learning and development (L&D) by the number of employees15). Items included in in-house education cost are L&D staff salary, travel cost for L&D staff, administrative cost, non-salary development cost, delivery cost, outsourced activities, and tuition reimbursement. Among the Fortune Global 500 corporations, the average direct expenditure per employee was USD 802 (JPY 74,888) in April 2010, and the direct expenditure as a proportion of payroll was 1.70% in 2012.

OH services cost management in workplace B by comparison with the reference costs

The actual personnel cost of OH staff to conduct OH services in workplace B was more than the reference cost, whereas the actual personnel cost of non-OH staff was considerably less than the reference cost. This was consistent with the OH management style in workplace B. Workplace B had two industrial hygienists and gave a large role in OH services to them, whereas workplace B had not assigned non-OH staff to OH services. The cost structure demonstrates how to conduct actual OH services.

The actual outsourcing cost for management of OH activities was zero because workplace B had not received any external certifications such as OHSAS 18001, whereas its actual personnel cost of non-OH staff to conduct OH services (JPY 7,957) was more than the reference costs because of a vigorous internal audit.

OH services cost management in workplace C by comparison with the reference costs

The actual personnel cost of OH staff to conduct OH services (JPY 33,302) was about half the reference cost. Workplace C was of medium scale and hired a part-time occupational physician. This affected the cost structure. In contrast, the actual personnel cost of non-OH staff to conduct OH services (JPY 93,129) was about two times more than the reference cost. This was especially prominent in the actual personnel cost of non-OH staff for management of OH activities (JPY 39,104). Risk assessment was conducted in all departments in workplace C once per month, and almost all employees attend the risk assessment. This suggests that the cost structure was consistent with the actual OH activities.

The actual depreciation expense (investment) (JPY 482) of equipment and fixtures, such as local exhaust ventilation, was only about one-hundredth the reference cost (JPY 43,877). This suggests that the needs for equipment and fixtures depend on category of industry and process of production.

Opportunity cost

This study is the first trial to construct a cost coefficient table including opportunity cost. OH services involve health interventions for employees by OH staff, and the methods of intervention are education, face-to-face guidance, health checkups, and medical treatment.

Economic evaluations are systematic comparisons of two or more health technologies, services, or programs looking at costs and consequences, and they include cost-minimization analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, and cost-benefit analysis13,16). Many economic evaluation studies have previously been conducted in the OH field, and cost analysis was usually conducted10,17,18). However, many previous research studies did not estimate opportunity cost. In our study, the opportunity cost per employee and proportion of opportunity cost in total OH services cost were JPY 19,747 and 11.2%, JPY 23,992 and 13.2%, and JPY 33,697 and 14.2%, respectively, in the three workplaces. These values were not negligible. In economic evaluation studies from a corporation's perspective, we should not forget to calculate opportunity cost.

In OH practices, opportunity cost reflects how widely the OH services reach employees because the cost is proportional to the time required for employees to receive OH services. The opportunity cost of health checkups was relatively high in terms of total opportunity cost and demonstrated how to conduct health checkups. The actual opportunity cost of health checkups (JPY 18,011) in workplace B was substantially more than the reference cost (JPY 10,384). In workplace B, health checkups had been conducted mainly outside the workplace, whereas in workplace A, health checkups had been conducted inside the workplace by an outsourcing institutiion. Employees over 35 years of age in workplace B were entitled to one day of leave in order to undergo a complete medical checkup in a hospital away from the business.

How to use a cost coefficient table

With a cost coefficient table, companies can compare the actual OH services costs with the reference costs. OH practitioners can report the characteristics of the cost structure for their own OH activities to employers compared with reference cost data. This is helpful for employers to judge how much is appropriate for investment in OH services and to make decisions regarding investment in OH services. For external stakeholders, the information can be used to detail activities as part of the company's corporate social responsibility. Several companies in Japan are making their OH services cost data available in their corporate social responsibility reports19).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of using the cost coefficient table that we developed is that the format of the data allows us to see the OH services cost of each activity and compare the cost with the reference cost. This is helpful to make decisions about investment in OH services.

There are several limitations in this study. We created a cost coefficient table and configured reference costs from only one company's cost data (workplace A). We chose workplace A because we judged OH services in workplace A as best practice based on its work process. Further studies are needed to validate reference costs by calculating OH services costs in more workplaces where OH services are accepted as best practice. The reference costs of OH services in this study were calculated based on large-scale manufacturing enterprises in Japan. Further studies are needed to make a cost coefficient table in various categories of business and in small-scale enterprises. Further studies are also needed to gather more data to establish standard OH costs for each category of business and for each size of company. Another limitation is that we did not compare reference costs with the consequences of OH interventions. Consequences can be the number of occupational diseases, frequency of lost-worktime illnesses, risk reduction of work-related illnesses, and improvement of health-related productivity. In this study, we did not obtain data regarding consequences. Further studies are needed to analyze this aspect.

Concluding remarks

We created a cost coefficient table for OH services including opportunity cost, set reference OH services costs, and compared actual OH services cost data to the reference data. The cost data from a cost coefficient table is helpful for employers to make decisions regarding investment in OH services.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their sincere appreciation to the companies that participated in this study. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Hiromi Ishida (Occupational Health Nurse), Mr. Haruo Hashimoto (Industrial Hygienist), Mr. Takuro Shoji (Safety specialist), and Mr. Osamu Sonoda (Certified Public Accountant).

This research was funded by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H23-Roudou-Wakate-006, Tomohisa Nagata as a representative researcher). The authors declare that they have no conflicting interests.

References

- 1). Verbeek J, Pulliainen M, Kankaanpaa E. A systematic review of occupational safety and health business cases. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009; 35: 403-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Berger ML, Howell R, Nicholson S, Sharda C. Investing in healthy human capital. J Occup Environ Med 2003; 45: 1213-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Koper B, Moller K, Zwetsloot G. The occupational safety and health scorecard-a business case example for strategic management. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009; 35: 413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Sakurai M. Management accounting. 5th ed, Tokyo (Japan): Dobunkanshuppan; 2012. p. 111-142 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 5). Nagata T, Mori K, Aratake Y, et al. . Development of cost estimation tools for total occupational safety and health activities and occupational health services: Cost estimation from a corporate perspective. J Occup Health 2014; 56: 215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev 2004; 82: 131-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Matsuda S. Strategic hospital management by DPC. Tokyo (Japan): Nihoniryoukikaku; 2010. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 8). Matsuda S. Interpretation of DPC from the basics. 3rd ed Tokyo (Japan): Igakushoin; 2011. p. 62-91 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 9). Bergstrom M. The potential-method-An economic evaluation tool. J Safety Res 2005; 36: 237-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Uegaki K, de Bruijne MC, van der Beek AJ, van Mechelen W, van Tulder MW. Economic evaluations of occupational health interventions from a company's perspective: A systematic review of methods to estimate the cost of health-related productivity loss. J Occup Rehabil 2011; 21: 90-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Vale L. Quality of systematic reviews of economic evaluations in health care. JAMA 2002; 287: 2809-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005; 21: 240-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Uegaki K, de Bruijne MC, Lambeek L, et al. . Economic evaluations of occupational health interventions from a corporate perspective- A systematic review of methodological quality. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010; 36: 273-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Braunig D, Kohstall T. Calculating the international return on prevention for companies: Costs and benefits of investments in occupational safety and health. Geneva (Switzerland): International Social Security Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15). Miller L. State of the industry, 2013. ASTD's annual review of workplace learning and development data. Virginia (the United States of America): the American Society of Training and Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16). Drummond M. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed, Oxford (The United Kingdom): Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- 17). Tompa E, Dolinschi R, de Oliveira C. Practice and potential of economic evaluation of workplace-based interventions for occupational health and safety. J Occup Rehabil 2006; 16: 375-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Tompa E, Dolinschi R, de Oliveira C, Irvin E. A systematic review of occupational health and safety interventions with economic analyses. J Occup Environ Med 2009; 51: 1004-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). TEIJIN LIMITED, Teijin Group Corporate Social Responsibility Report. [Online]. 2012 [cited 2015 Sep. 28]; Available from: URL: http://www.teijin.com/csr/report/pdf/csr_12_10.pdf. p. 49.