Abstract

Background

Treatment with statins improves clinical outcome, but the exact mechanisms of pleiotropic statin effects on vascular function in human atherosclerosis remain unclear. We examined the direct effects of atorvastatin on tetrahydrobiopterin-mediated endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase coupling in patients with coronary artery disease.

Methods and Results

We first examined the association of statin treatment with vascular NO bioavailability and arterial superoxide (O2·−) in 492 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Then, 42 statin-naïve patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery were randomized to atorvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for 3 days before surgery to examine the impact of atorvastatin on endothelial function and O2·− generation in internal mammary arteries. Finally, segments of internal mammary arteries from 26 patients were used in ex vivo experiments to evaluate the statin-dependent mechanisms regulating the vascular redox state. Statin treatment was associated with improved vascular NO bioavailability and reduced O2·− generation in internal mammary arteries. Oral atorvastatin increased vascular tetrahydrobiopterin bioavailability and reduced basal and N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester–inhibitable O2·− in internal mammary arteries independently of low-density lipoprotein lowering. In ex vivo experiments, atorvastatin rapidly improved vascular tetrahydrobiopterin bioavailability by upregulating GTP-cyclohydrolase I gene expression and activity, resulting in improved endothelial NO synthase coupling and reduced vascular O2·−. These effects were reversed by mevalonate, indicating a direct effect of vascular hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibition.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates for the first time in humans the direct effects of statin treatment on the vascular wall, supporting the notion that this effect is independent of low-density lipoprotein lowering. Atorvastatin directly improves vascular NO bioavailability and reduces vascular O2·− through tetrahydrobiopterin-mediated endothelial NO synthase coupling. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms mediating the beneficial vascular effects of statins in humans.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01013103.

Keywords: statins, tetrahydrobiopterin, oxidative stress, superoxide, nitric oxide synthase

Statins are now considered a fundamental component of the treatment of patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease.1 Reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by statins reduces cardiovascular risk in both primary1 and secondary2 prevention and is associated with improvements in other markers of vascular disease risk, including inflammation and endothelial function.3,4

Clinical Perspective.

Statin treatment reduces cardiovascular risk. Although statins exert their antiatherogenic effects mainly by reducing low-density lipoprotein, experimental studies demonstrated a number of pleiotropic effects directly on the vascular cells. However, mechanistic studies examining the pleiotropic effect of statins on endothelial nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and the vascular redox state in human arteries are remarkably limited. In the present study, we first demonstrate that in a real-life population of 492 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, the use of statins was a predictor of both improved endothelial function and reduced vascular superoxide (O2·−) in internal mammary arteries (IMAs). Next, in a randomized, clinical trial with 42 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, we demonstrated that 3 days of treatment with atorvastatin 40 mg/d before coronary artery bypass graft surgery improved endothelial function and reduced vascular O2·− in internal mammary arteries of these patients by improving endothelial NO synthase coupling with increased vascular levels of the endothelial NO synthase cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin. We then performed a number of mechanistic ex vivo experiments in which atorvastatin rapidly upregulated GTP-cyclohydrolase I gene expression in the arterial wall, increased GTP cyclohydrolase I activity, and stimulated the synthesis of vascular biopterins, resulting in an improvement of endothelial NO synthase coupling, a reduction of endothelium-derived vascular O2·−, and an improvement in endothelial function in a low-density lipoprotein–free environment. These effects were due to a direct inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in the vascular wall. Therefore, our study demonstrates for the first time in humans that high-dose treatment with atorvastatin rapidly modifies the vascular redox state and endothelial function via tetrahydrobiopterin-mediated endothelial NO synthase coupling, providing one of the first direct reports of a pleiotropic effect of statins on the human arterial endothelium.

In addition to LDL lowering, statins have been demonstrated to exert a number of pleiotropic effects.5–7 Reduction of LDL by statin therapy appears to confer a greater reduction of cardio-vascular risk than LDL lowering by other modalities,8 and clinical trials demonstrate that statin treatment improves endothelial function more effectively than LDL lowering by diet or ezetimibe.9 These potential effects of statins are important because they may identify novel therapeutic mechanisms that are amenable to further modification or suggest new clinical indications for statin therapy.

Vascular oxidative stress is a key feature of atherogenesis,5 and targeting vascular redox signaling is a rational therapeutic goal in vascular disease pathogenesis. However, identifying the specific enzymatic systems and mechanisms that regulate vascular redox signaling is a critical requirement for developing novel therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis.5,10 Recent observations suggest that uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) is an important mechanism that links impaired endothelial function with increased vascular superoxide production in humans.11 Reduced levels of the eNOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) leads to eNOS uncoupling in the human vasculature,12,13 whereas restoration of vascular BH4 bioavailability can reverse eNOS uncoupling, shifting the enzyme toward the production of NO,14–17 and may retard vascular disease progression.18 Although these observations suggest that eNOS coupling is a potential therapeutic target in vascular disease pathogenesis,5 it remains uncertain whether eNOS coupling is amenable to therapeutic intervention in humans.

Recent evidence suggested that statin treatment exerts systemic antioxidant effects in patients with atherosclerosis,19 whereas experimental studies have demonstrated that statins also reduce vascular O2·− generation in animal20 and cell culture21 models. In endothelial cells, statins rapidly increased BH4 bioavailability by upregulating GCH1, encoding GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH I), the rate-limiting enzyme in the BH4 biosynthetic pathway.22 Recent evidence suggested a direct effect of statins on Rho/Rho kinase pathway in human leukocytes, providing the first strong evidence of a direct pleiotropic effect of statins at the level of cell signaling in humans.7,23 However, the direct effects of statins on human arterial O2·− generation and their possible impact on eNOS coupling in human blood vessels are unknown.

We sought to investigate the effects and mechanisms of statin treatment on the human vasculature by quantifying the effects of statins on vascular NO bioavailability, vascular O2·− generation, and BH4-mediated eNOS coupling in patients with coronary artery disease. We first tested for associations between statin treatment and markers of endothelial function in a cohort of coronary artery disease patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and then carried out a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of short-term statin treatment. In each study, we evaluated the functional and biochemical effects of statins in samples of blood vessels obtained at the time of CABG. Finally, we probed mechanisms in studies of human vessels exposed to statins ex vivo, thus removing the systemic effects of LDL lowering.

Methods

Study Populations and Clinical Trial Protocol

In study 1, we examined whether treatment with statins was associated with endothelial function and the arterial redox state in patients with coronary artery disease. A total of 886 patients scheduled for elective CABG at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford (n=395) or the Hippokration Hospital in Athens (n=491) were screened prospectively from 2004 to 2010. Of this population, 610 met the inclusion criteria (Oxford, n=285; Athens, n=325) and 492 agreed to participate (Oxford, n=254; Athens, n=238). There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics of patients between the 2 centers. Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement shows a diagram of the recruitment procedure. Exclusion criteria were any inflammatory, infective, liver, or renal disease or malignancy. Patients receiving nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, dietary supplements, or antioxidant vitamins were also excluded. Patients not treated with statins were defined as those who had not received any statin treatment for at least 2 months before recruitment. Blood samples were collected, and endothelial function was evaluated by measuring flow-mediated dilation (FMD) in the brachial artery by ultrasound. At the time of CABG, samples of internal mammary artery (IMA) were collected and used to evaluate arterial O2·− generation. Endothelial function was also evaluated in saphenous vein segments through ex vivo isometric tension studies in organ baths.

In study 2, we examined whether the associations between statin treatment and vascular redox observed in study 1 were causal. To address that question, a total of 332 patients undergoing elective CABG were screened to identify patients who were not currently taking statins and fulfilled the inclusion criteria (n=66), 42 of whom agreed to participate. Patients were then randomized to receive either atorvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for 3 days preoperatively in a randomized (using block randomization), double-blind fashion. Flow-mediated dilation was determined at baseline (before treatment initiation) and on the day before CABG. Blood samples were obtained at baseline and on the morning of the operation. During CABG, segments of IMA were collected to evaluate the mechanisms regulating vascular O2·− and NO bioavailability. Exclusion criteria were any inflammatory, infective, liver, or renal disease; malignancy; and known intolerance to statins. Patients receiving non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs, dietary supplements, and antioxidant vitamins and those who received statins during the previous 3 months were also excluded.

In study 3, we examined whether the effect of atorvastatin on vascular redox state in human arteries was independent of the systemic effects of LDL lowering and explored possible alternative mechanisms. We used an ex vivo system of human vessels in which we exposed IMAs directly to atorvastatin in an LDL-free environment. For these experiments, we prospectively screened 54 patients scheduled for elective CABG; 36 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and 26 agreed to participate. Because of the various different experiments, vessels from different patients were used in different experiments as stated. Blood samples from these patients were obtained on the morning before CABG, and segments of IMA were harvested and transferred to the laboratory for the ex vivo experiments.14 The inclusion criteria were the same as for study 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the 3 studies are presented in Table 1. Risk factors were defined according to the Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the definition and identification of risk factors24 as follows. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg on multiple measurements or taking antihypertensive medications. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a history of hypercholesterolemia for >3 months that led to the initiation of lipid-lowering therapy by the primary physician or fasting serum cholesterol value >240 mg/dL. Diabetes mellitus was defined as high fasting blood glucose levels (≥120 mg/dL), requiring glucose lowering therapy, or taking antidiabetic treatment. Smoking status was defined as follows: nonsmokers, those who had never smoked; ex-smokers, those who had stopped cigarette smoking for >1 month; and active smokers, those who had smoked any cigarettes during the last month. The study protocol was approved by the local research ethics committees, and each patient gave written informed consent.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Details of the Participants.

| Study 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Placebo | Atorvastatin | Study 3 | |

| Patients (M/F), n | 492 (411/81) | 21 (20/1) | 21 (18/3)* | 26 (21/5) |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Age, y | 65.9±0.41 | 67.38±1.99 | 66.14±2.04* | 63.5±1.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n | 159 | 9 | 7* | 7 |

| Dyslipidemia, n | 311 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Hypertension, n | 333 | 16 | 18* | 12 |

| Smokers, n | ||||

| Current | 185 | 7 | 8* | 7 |

| Ex-smokers | 212 | 10 | 9* | 13 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.7±0.22 | 27.7±0.8 | 27.5±0.7* | 27.9±0.7 |

| Serum lipid levels | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 166 (143–195) | 205 (157–244) | 225 (184–243) | 184 (141–218) |

| Posttreatment | … | 191 (165–251) | 171 (144–204) | … |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 125 (94–162) | 206 (102–264) | 132 (94–191) | 123 (104–160) |

| Posttreatment | … | 146 (105–185) | 113 (89–166) | … |

| HDL, mg/dL | ||||

| Baseline | 39.0 (33.0–43.8) | 35.0 (31.0–47.0) | 39.0 (35.5–42.8) | 35.0 (31.5–40.0) |

| Posttreatment | … | 39.0 (32.5–42.0) | 37.0 (33.0–45.0) | … |

| Medication, n | ||||

| Statins | 395 | … | …. | 9 |

| ACEi | 272 | 8 | 11* | 16 |

| ARBs | 52 | 4 | 6* | 5 |

| CCBs | 135 | 5 | 5* | 4 |

| β-blockers | 368 | 13 | 13* | 21 |

| Aspirin | 390 | 12 | 13* | 22 |

| Clopidogrel | 154 | 8 | 6* | 14 |

| Diuretics | 104 | 8 | 10* | 6 |

HDL indicates high-density lipoprotein; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; and CCB, calcium channel blockers. There was no significant difference in the changes of serum lipid levels between the atorvastatin- and placebo-treated groups (as tested by ANOVA for repeated measures with time-by-treatment interaction). Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SEM or median (25th to 75th percentile) as appropriate.

P=NS (P>0.05 vs placebo).

Assessment of Endothelial Function

Flow-mediated dilation and endothelium-independent vasodilatations of the brachial artery (for studies 1 and 2) were measured by ultrasound (see the online-only Data Supplement).

Vessel Harvesting and Vasomotor Studies

Vasomotor studies in study 1 were performed in saphenous vein samples. Vessel harvesting and the methodology of vasomotor studies are described in the online-only Data Supplement.

Oxidative Fluorescent Microtopography

In situ O2·− production was determined in vessel cryosections from study 3 with oxidative fluorescent dye dihydroethidium, as described in the online-only Data Supplement.

Determination of Vascular Superoxide Production

Vascular O2·− production (in all studies) was measured in fresh segments of intact IMA with lucigenin (5 µmol/L)-enhanced chemiluminescence (see the online-only Data Supplement).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was extracted from paired IMA rings from the ex vivo study (study 3), and the expression of GCH1 was quantified by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (see the online-only Data Supplement).

Measurement of Vascular Rac1 Activation

Rac1 activation was evaluated by an affinity precipitation assay using PAK1-PBD–conjugated glutathione agarose beads (see the online-only Data Supplement).

Ex Vivo Studies (Study 3)

To examine the direct effect of atorvastatin on vascular O2·− generation in human arteries, IMA segments were incubated ex vivo for 6 hours in an organ bath system containing oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Krebs Henseleit buffer at 37°C, as we have previously described.14 Two rings from the same IMA were incubated with either 0 or 5 µmol/L atorvastatin for 6 hours. Both basal O2·− and N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)–inhibitable vascular O2·− were quantified in both rings from each patient at the end of the incubation period. To examine whether the effects of atorvastatin on human IMAs were mediated through direct inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase in the vascular wall, we incubated paired IMA segments from 13 patients with/without atorvastatin in the presence or absence of mevalonate (200 µmol/L) for 6 hours. Five of these vessels were used for luminometry experiments and 8 for dihydroethidium staining and fluorescence microtopography. To evaluate the effect of atorvastatin on GTPCH activity, serial IMA rings from 8 patients were incubated for 6 hours (control) in the presence of the GTPCH inhibitor 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine (DAHP; 1 mmol/L), DAHP and atorvastatin (5 µmol/L), or atorvastatin alone. Vascular biopterins were then determined in these vessels to examine whether the effect of atorvastatin on vascular biopterins was due to an increase in GTPCH activity.

Blood Sampling and Serum Lipid Measurements

Fasting venous blood samples were taken after 12 hours of fasting on the morning of the operation (studies 1 and 3) or both at baseline and on the morning of the operation (study 2) (see the online-only Data Supplement for further details).

Determination of Plasma and Vascular Biopterin Levels

Levels of BH4 and total biopterins (BH4 plus dihydrobiopterin [BH2] plus biopterin) in plasma (study 2) or vessel tissue lysates (studies 2 and 3) were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography followed by electrochemical (BH4) and fluorescence (BH2 and biopterin) detection, as we have previously described.24

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables in all 3 studies were tested for normal distribution by use of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and a significance level <0.05 was used to reject the null hypothesis of normal distribution. Nonnormally distributed variables were log transformed for analysis, and they all met the criterion for normality after their first transformation; these variables are presented in a nonlogarithmic format as median (25th to 75th percentile).

Sample size calculations were based on previous data from our laboratory. For study 1, we assumed that 80% of the eligible subjects would be receiving statin treatment. Therefore, we estimated that 420 samples would be able to detect a difference 0.753 relative light units (RLU) · s−1 · mg−1 in vascular O2·− between statin-treated and statin-untreated patients, with a power of 90% and an α of 0.05, when SD=1.9 RLU · s−1 · mg−1. However, we increased the number of patients to 492 to allow for possible incomplete data in some patients. For study 2 (statin-naïve patients), power calculations suggested that 20 subjects per group would be able to detect a 2.21-RLU · s−1 · mg−1 difference in vascular O2·− generation with an α of 0.05 and a power of 90% when SD=2.0 RLU · s−1 · mg−1, as suggested by previous data from our laboratory in a similar population. For study 3, sample size calculations were performed on the basis of our previous experience on this model,14,25 and we estimated that with 5 pairs of samples (serial rings from the same vessel) we would be able to identify a change of vascular O2·− by 5.4 RLU · s−1 · mg−1 and vascular BH4 by 16.6 pmol/g with a power of 90% and an α of 0.05 when the SD for the difference in the response of matched pairs is 2.8 RLU · s−1 · mg−1 for O2·− and 8.6 pmol/g for BH4. However, we increased the numbers to 10 in individual experiments, depending on sample availability.

In both studies 1 and 2, continuous variables between 2 independent groups were compared by using unpaired t test, whereas categorical variables were compared by use of the χ2 test as appropriate. For the organ bath experiments, the effect of treatment on vasorelaxations in response to acetylcholine was evaluated by using 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures (examining the effect of acetylcholine concentration–by–statin treatment status [fixed factors] interaction on vasorelaxations) in a full factorial model. Because the sphericity assumption did not hold (Mauchly test of sphericity, P<0.0001), the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used, which showed a significant difference in vasorelaxations through the course of the study (F=22.783, P<0.01). The effect of treatment on plasma biomarkers and FMD was compared between the 2 groups in study 2 by use of 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures with time-by-treatment interaction (fixed factors). For the ex vivo experiments in study 3 (in which serial rings from the same vessel were incubated with 0 or 5µmol/L atorvastatin in the presence or absence of mevalonate or DAHP as stated), we first performed 1-way ANOVA for repeated measures to test whether the type of incubation (fixed factor) would affect superoxide generation or BH4 levels. Compound symmetry was assumed and sphericity was confirmed by the Mauchly test in all ANOVA models in study 3. When a significant overall P value was detected, individual paired comparisons were performed, and P values were corrected with the Bonferroni correction. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were met in all ANOVA models in the 3 studies.

Correlations between continuous variables were assessed by use of bivariate analysis. The Pearson coefficient was estimated.

In study 1, we performed linear regression by using FMD or arterial O2·− as the dependent variable and the clinical demographic characteristics (age, sex, diabetes mellitus, active smoking dyslipidemia, hypertension, and body mass index) and medication (statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, aspirin, clopidogrel, and diuretics) as independent variables that showed an association with the dependent variable in bivariate analysis at the level of 15%. A backward elimination procedure was then used by having P=0.1 as threshold to remove a variable from the respective model. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS version 18.0. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In every analysis, we included only those patients without missing values. Patients with missing values were excluded from the respective analyses.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Associations Between Statin Therapy, Endothelial Function, and Vascular Superoxide (Study 1)

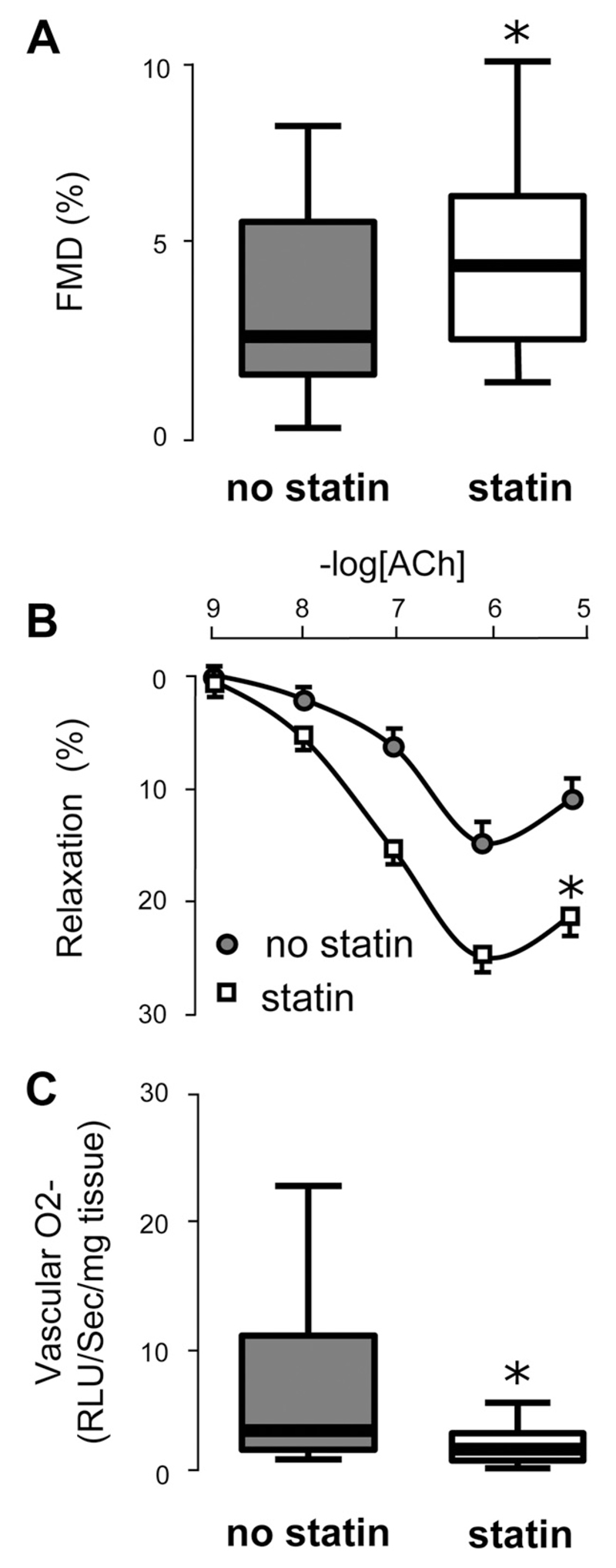

In study 1, we first examined whether statin treatment was associated with endothelial function and vascular O2·− generation in 492 patients undergoing CABG. In multivariable analysis, we observed that statin treatment was associated with FMD after controlling for risk factors and other medication (Table 2). We observed that those patients receiving statins had significantly greater FMD of the brachial artery in vivo and greater vasorelaxations of saphenous vein in response to acetylcholine ex vivo, findings that suggested improved endothelial NO bioavailability (Figure 1). There was no significant association between statin treatment and either endothelium-independent dilatation of the brachial artery to nitroglycerine or vasorelaxations of saphenous vein to sodium nitroprusside (data not shown). Furthermore, in multivariable analysis, statin treatment was associated with O2·− generation in IMA after controlling for risk factors and other medication, with patients receiving statins having significantly lower arterial O2·− generation compared with those not receiving statins (Figure 1). A similar effect of statin treatment on vascular O2·− was observed in saphenous vein segments obtained from these patients (data not shown). However, this was an observational, nonrandomized study, and there was large heterogeneity in the type of statin treatment and the dosage administered.

Table 2. Multivariable Predictive Models of Flow-Mediated Dilation and Arterial Superoxide in Study 1.

| FMD in Brachial Artery (Model: R2= 0.271, P=0.0001), % |

Log(O2·−) in Internal Mammary Artery (Model: R2=0.218, P=0.0001), RLU · s–1 · mg−1 Tissue |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Regression Estimates of β (SE), P | Variable | Regression Estimates of β (SE), P |

| Statin treatment | 1.3 (0.5), 0.01 | Statin treatment | −0.4 (0.08), 0.0001 |

| ACEi/ARB | 2.7 (0.4), 0.001 | Diabetes mellitus | 0.2 (0.04), 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | −1.3 (0.5), 0.006 | Hypertension | 0.1 (0.05), 0.030 |

| Hypertension | −1.8 (0.5), 0.0001 | Active smoking | 0.06 (0.03), 0.032 |

| Active smoking | −1.7 (0.3), 0.0001 | ||

FMD indicates flow-mediated dilation in the brachial artery; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; and ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Figure 1.

In study 1 (n=492), patients receiving regular statin treatment, had significantly better flow-mediated dilation (FMD) compared with those not receiving statins (A). In saphenous veins obtained from 256 of these patients during coronary artery bypass graft surgery, ex vivo vasorelaxations in response to acetylcholine (ACh) were significantly greater in subjects receiving statins (n=212) compared with those not receiving statins (n=44; B). In internal mammary artery samples obtained from these patients, vascular O2·− was significantly lower in those receiving statin treatment compared with those not receiving statins (C). The statin treatments in this population were simvastatin (63.1%), atorvastatin (26.8%), rosuvastatin (4.3%), pravastatin (3%), lovastatin (1.6%), and fluvastatin (1%). Values expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile; A and C) or mean±SEM (B). *P<0.01 vs no statin treatment (P values were derived from unpaired t test of the log-transformed values for A and C and by 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures for B).

Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Statin Treatment in Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patients (Study 2)

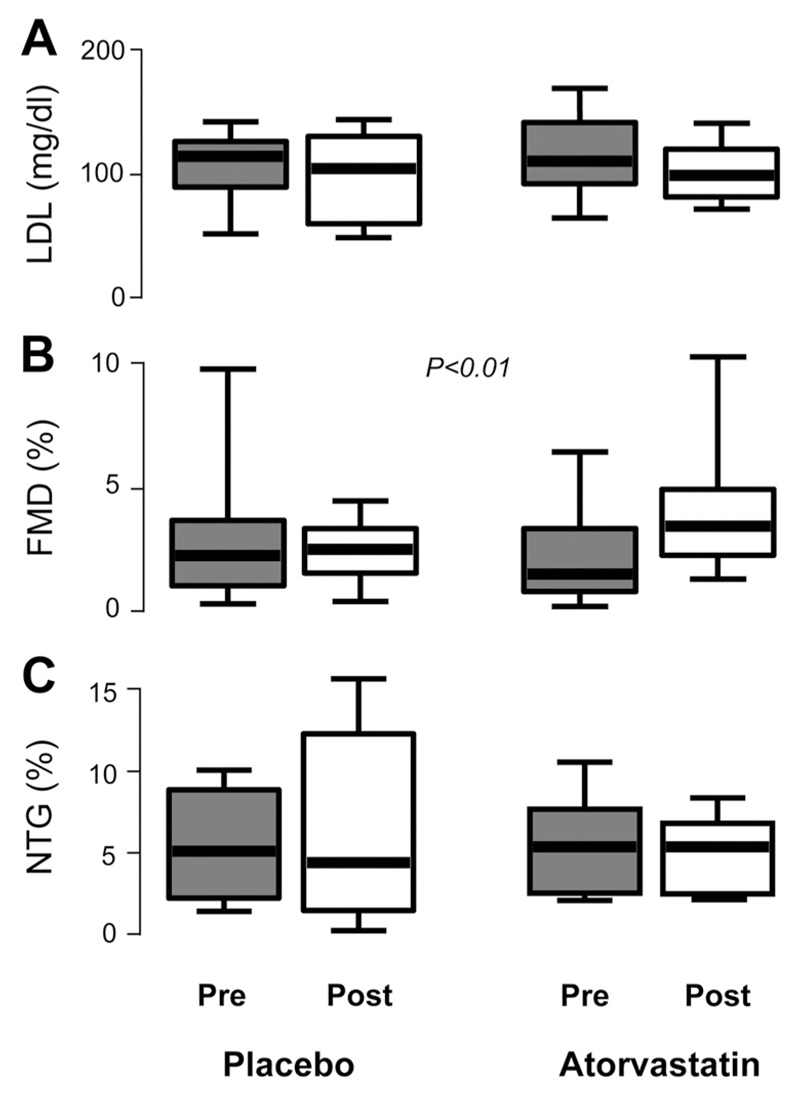

Although the results of study 1 revealed associations between the use of statin therapy, vascular NO bioavailability, and O2·− generation in human arteries, these findings did not imply causality, nor could they address statin effects independent of the systemic effects of chronic LDL reduction. Accordingly, we next conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in which 42 statin-naïve patients were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 40 mg/d or placebo for 3 days before CABG (study 2). This short treatment period was chosen to test the vascular effects of atorvastatin before a significant lowering of LDL was observed. Indeed, after 3 days of treatment, there was no significant reduction of LDL in the atorvastatin-treated group compared with the placebo group (Figure 2). However, atorvastatin induced a significant improvement in FMD compared with placebo, with no change in the response to nitroglycerine (Figure 2). Importantly, there was no correlation between the change in LDL and the respective change in FMD in the study population (r=−0.011, P=0.948), further supporting the notion that the effect of atorvastatin on FMD was independent of LDL lowering.

Figure 2.

In study 2, there was no significant difference in the change in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels between patients who received atorvastatin (n=21) and those who received placebo (n=21; P=0.704; A). However, flow-mediated dilation (FMD) was improved in the atorvastatin-treated group compared with placebo (B). There was no significant difference (P=0.774) in the changes in endothelium-independent dilatation of the brachial artery in response to nitroglycerine (NTG) between the 2 groups (C). P values were derived by using 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures with time-by-treatment interaction on the log-transformed values. Values expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile).

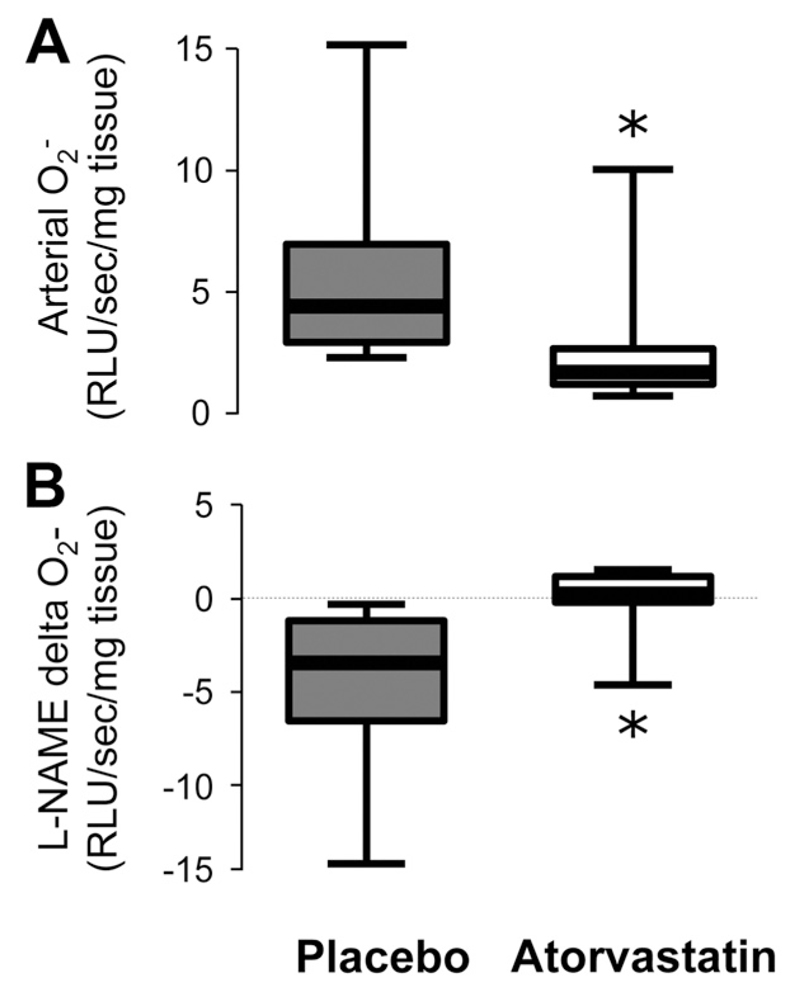

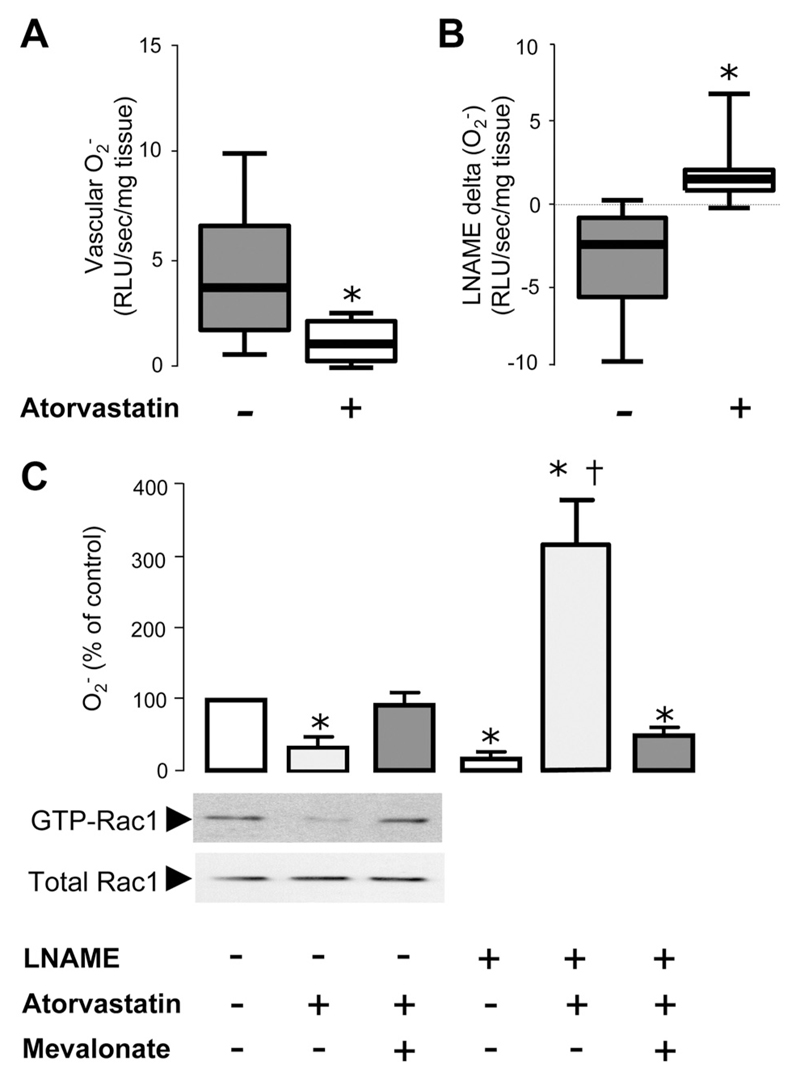

We next examined the effects of atorvastatin treatment on O2·− production from segments of IMA obtained at CABG. We observed that 3 days of atorvastatin treatment significantly reduced arterial O2·− compared with placebo (Figure 3). Importantly, vascular O2·− generation in IMAs from these patients was not correlated with the changes in LDL (r=0.224, P=0.226). To address the possible effects of atorvastatin on eNOS uncoupling, we measured L-NAME– inhibitable O2·− in these vessels. Treatment with atorvastatin reduced L-NAME–inhibitable O2·−, suggesting an improvement in arterial eNOS coupling (Figure 3). Again, these changes were not correlated with the respective changes in LDL after 3 days of statin treatment (r=−0.269, P=0.150), implying a direct effect of statins on the redox state of human arteries in vivo.

Figure 3.

In study 2, vascular superoxide (O2·−) generation in internal mammary arteries obtained from patients who received atorvastatin (n=18) was significantly lower compared with patients who received placebo (n=20; A). In the same vessels, O2·− generation was decreased by N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) in mammary arteries obtained from patients who received placebo (B), whereas this effect was reversed in vessels from atorvastatin-treated patients. Values expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile). *P<0.01 vs placebo.

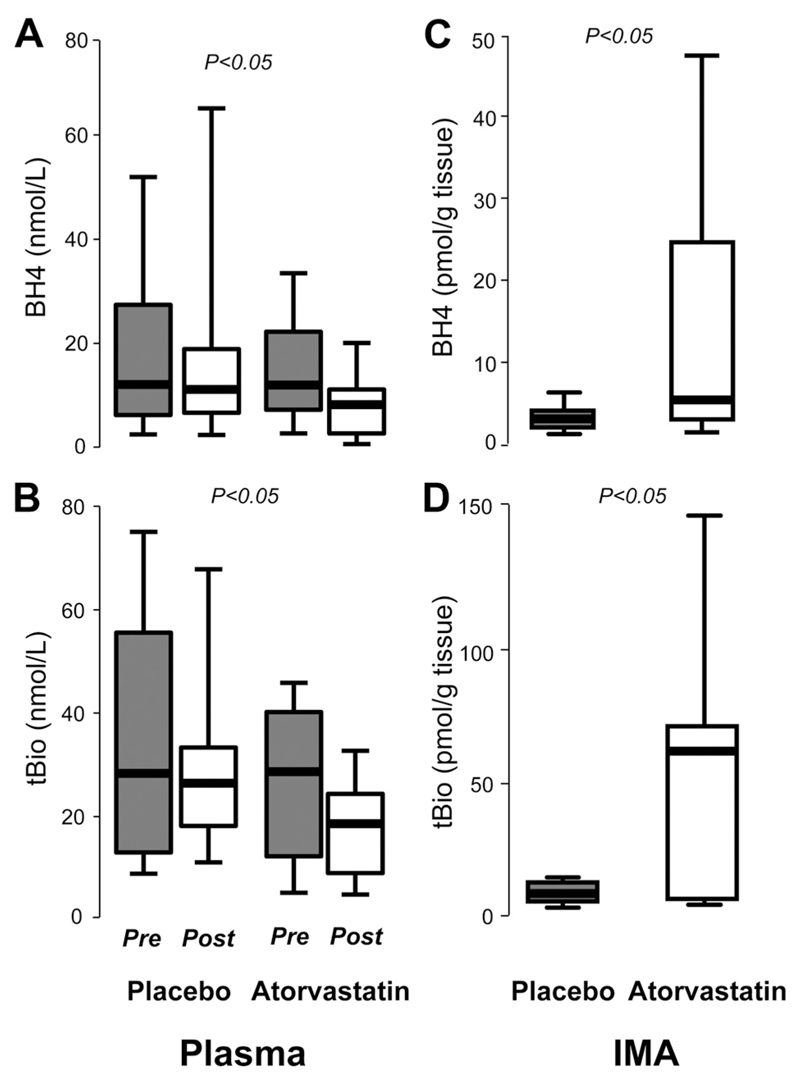

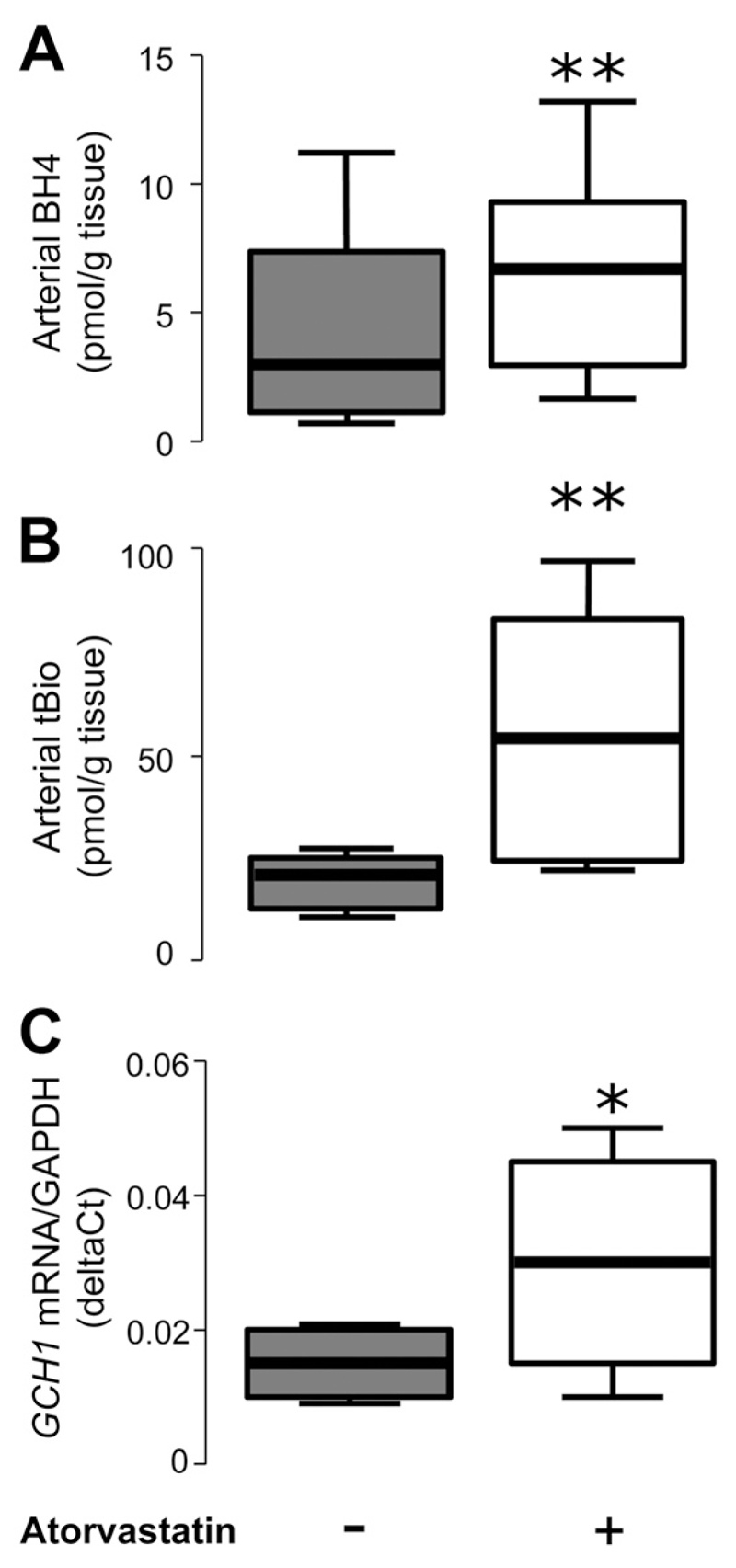

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying the observed effects of atorvastatin on eNOS coupling, we quantified the levels of BH4 in both plasma and vessel tissue obtained at the time of CABG. We observed that atorvastatin treatment for 3 days resulted in a modest but significant reduction in plasma BH4 and total biopterins (Figure 4), consistent with a systemic antiinflammatory effect of statins. In contrast, vascular tissue BH4 levels in IMA segments obtained at CABG surgery were strikingly increased, by >3-fold, in patients receiving atorvastatin (Figure 4). A similarly striking effect was also observed on vascular total biopterins, suggesting that atorvastatin treatment stimulates biopterin, biosynthesis, leading to an increase in all biopterin species in human arteries (Figure 4). No changes in the ratio of BH4 to BH2 or BH4 to total biopterins were observed either in plasma or in the vessels from this study.

Figure 4.

In study 2, plasma tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4; A) and total biopterins (tBio; B) were significantly reduced in patients who received atorvastatin (n=18) compared with placebo (n=20). However, vascular BH4 (C) and tBio (D) were significantly greater in mammary arteries (IMA) obtained from patients who received atorvastatin compared with placebo. Values are expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile). P values in A and B were derived from 2-way ANOVA with time-by-group interaction and in C and D from unpaired t test between the 2 groups on the log-transformed values.

Direct Effects of Atorvastatin Treatment on Human Arteries Ex Vivo (Study 3)

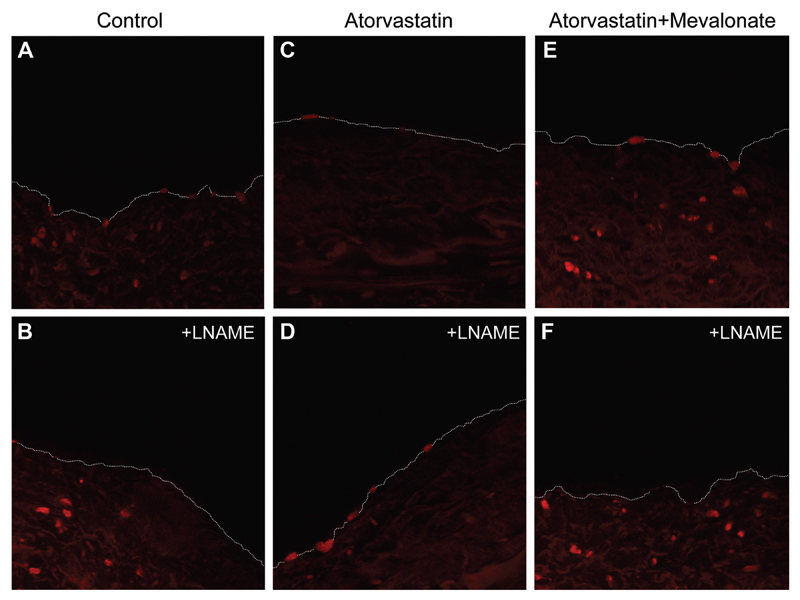

Although the results of study 2 demonstrated that short-term oral treatment with atorvastatin 40 mg/d leads to a significant reduction of vascular O2·− in human arteries through an improvement of eNOS coupling, it was still unclear whether this effect was due to a direct impact on the vessel wall or to other systemic effects. Accordingly, we next tested the effects of atorvastatin in an ex vivo study in which paired segments of IMAs were incubated in the presence of either 0 or 5µmol/L atorvastatin for 6 hours in an LDL-free environment. We observed that atorvastatin rapidly reduced O2·− generation (Figure 5). In particular, atorvastatin reversed L-NAME–inhibitable vascular O2·− in these arteries, suggesting that atorvastatin reduces vascular O2·− by improving enzymatic coupling of eNOS (Figure 5). The effects of atorvastatin on both vascular O2·− and L-NAME–delta (O2·−) were reversed by the presence of mevalonate (Figure 5). These findings suggested that atorvastatin exerts its striking effect on vascular O2·− generation in human arteries independently of systemic LDL lowering by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase directly in the arterial wall. Indeed, incubation with atorvastatin reduced vascular Rac1 activation, an effect that was reversed by mevalonate (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In study 3, ex vivo incubation of human mammary arteries with atorvastatin (5 μmol/L) induced a significant reduction of vascular superoxide (O2·− ; A) and reversed N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)–inhibitable O2·− (B) in these vessels (n=10 patients). In a second set of experiments (C; n=5 patients), the reduction of vascular O2·− by atorvastatin was reversed in the presence of mevalonate (P=0.650 vs control after Bonferroni correction). In this experiment (C), L-NAME reduced vascular O2·− in the absence of atorvastatin and increased vascular O2·− in vessels preincubated with atorvastatin. Coincubation of these vessels with atorvastatin and mevalonate prevented the effect of atorvastatin on L-NAME–induced changes in vascular O2·− (P=0.08 for L-NAME plus atorvastatin plus mevalonate vs L-NAME only). The direct effect of atorvastatin on vascular wall biology was also confirmed by demonstrating a change in vascular Rac1 activation in these vessels (C). − Indicates no atorvastatin or mevalonate; +, atorvastatin 5μmol/L or mevalonate 200μmol/L. Values are expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile; A and B) or mean±SEM (C). One-way repeated measures ANOVA in C revealed a significant effect of treatment in all readouts (PANOVA<0.001). *P<0.01 for individual comparisons vs control (no atorvastatin, no mevalonate and no L-NAME) after Bonferroni correction; †P<0.01 for individual comparisons vs L-NAME alone (no atorvastatin, no mevalonate) after Bonferroni correction.

To estimate the exact effects of atorvastatin on endothelium-derived O2·−, we performed dihydroethidium staining in vessels from 8 patients in the ex vivo study (study 3; Figure 6). We observed that atorvastatin reduced endothelium-derived O2·− and that this effect was reversed by mevalonate (Figure 6). In addition, L-NAME reduced endothelium-derived O2·− in control vessels and increased endothelium-derived O2·− in vessels incubated with atorvastatin. This effect of atorvastatin was reversed by mevalonate (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Dihydroethidium staining in cryosections of serial internal mammary artery rings from the same vessel incubated for 6 hours with atorvastatin 0 μmol/L (A and B), atorvastatin 5 μmol/L (C and D), and atorvastatin 5 μmol/L plus mevalonate 200 μmol/L (E and F). Endothelium-derived dihydroethidium staining was reduced after atorvastatin, whereas this effect was reversed by mevalonate. N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) induced a reduction of endothelium-derived fluorescence in control (B) and atorvastatin plus mevalonate vessels (F), whereas an opposite effect was observed in the atorvastatin-treated vessels (D). This observation suggests an improvement of endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling by atorvastatin, an effect that is prevented by mevalonate. Images are representative of 8 sets of internal mammary arteries.

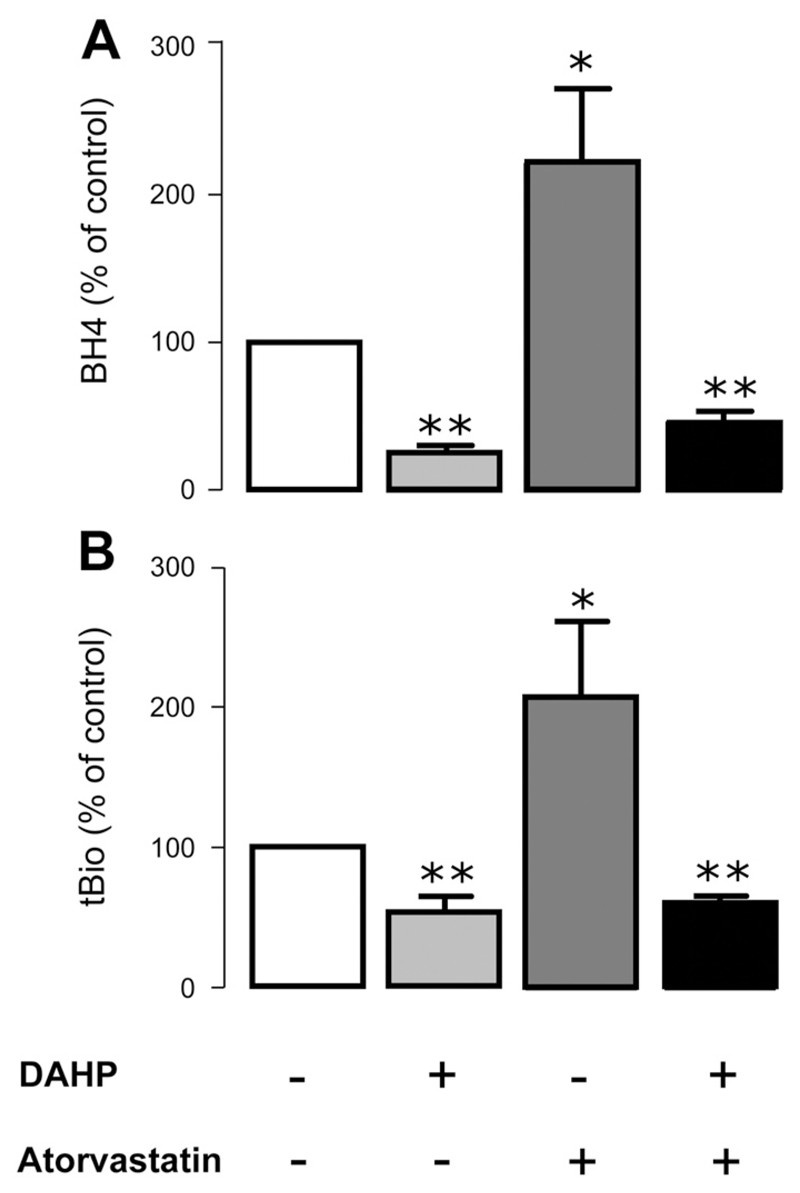

To further explore the mechanisms by which atorvastatin modifies eNOS coupling in human vessels, we quantified the changes in vascular biopterin bioavailability. In keeping with the results from study 2, we observed that after 6 hours of incubation, atorvastatin induced a significant elevation of vascular tissue BH4 and total biopterins (but not the ratio of BH4 to BH2 or BH4 to total biopterins). Furthermore, we observed a significant upregulation of GCH1 gene expression encoding GTPCH I, measured by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (Figure 7). We also observed that the atorvastatin-induced elevation of vascular biopterins in our ex vivo model was prevented in the presence of the GTPCH I inhibitor DAHP, suggesting that the effect of atorvastatin on vascular biopterins is mediated through GTPCH I activation (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

In study 3, ex vivo incubation of human internal mammary arteries (from 10 patients) with atorvastatin induced a significant increase of vascular tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4; A) and total biopterins (tBio; B) compared with control. Atorvastatin also significantly increased GCH1 mRNA (relative to GAPDH) in these vessels (C). Values are expressed as median (25th to 75th percentile). − Indicates no atorvastatin; +, atorvastatin 5 μmol/L. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs control (no atorvastatin).

Figure 8.

In study 3, 6 hours of incubation of serial internal mammary artery rings (from 8 patients) with atorvastatin increased both vascular tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4; A) and total biopterins (tBio; B). However, in the presence of the GTP cyclohydrolase I inhibitor DAHP, vascular BH4 (A) and tBio (B) were both significantly reduced and atorvastatin could not prevent this reduction, suggesting that the impact of atorvastatin on vascular biopterins is mediated through an effect on GTP cyclohydrolase I enzymatic activity. − Indicates no atorvastatin or DAHP; +, atorvastatin 5 μmol/L or DAHP 1 mmol/L. Values are expressed as mean±SEM. One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of treatment on all readouts (PANOVA<0.001). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 for individual comparisons vs control (no atorvastatin, no DAHP) after Bonferroni correction.

Discussion

In this study, we first demonstrate that statin treatment is associated with reduced arterial O2·− generation and improved endothelial function in patients with atherosclerosis. Moreover, we demonstrate for the first time in humans a direct pleiotropic effect of atorvastatin on the human arterial wall by showing that atorvastatin treatment rapidly reduces vascular O2·− generation in the human arterial wall and improves endothelial function within 3 days without any significant change in LDL cholesterol. We further demonstrate that these beneficial direct effects of atorvastatin on the human vascular wall, causing direct inhibition of vascular HMG CoA reductase and the mevalonate pathway, could be mediated by improved eNOS coupling through increased BH4 bioavailability. These novel findings provide important evidence indicating a direct effect of statin treatment on arterial eNOS function and redox signaling in human atherosclerosis.

Statins and Pleiotropic Effects on Endothelial Function

Inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase by statins has large beneficial impacts on cardiovascular risk.1,2 HMG-CoA reductase leads to the synthesis of mevalonate, which is then converted to fernesyl-PP. From this metabolite, the pathway leads either to the synthesis of cholesterol or to the synthesis of geranylgeranyl-PP, which results in the activation of geranylgeranylated proteins such as Rho and others (ie, Rac1). These are molecules with a well-characterized role in atherogenesis. However, this information is based largely on animal and cell culture studies,3,4,26 and there is no direct evidence regarding the role of HMG-CoA reductase in human vessels.

Statins have systemic antioxidant effects and improve endothelial function3,4,26 by preventing the oxidation of NO and by upregulating eNOS in animal models.27,28 Recently, the first important evidence for a direct pleiotropic effect of statins in humans was shown at the level of cell signaling by studies on the Rho/Rho kinase pathway in human leukocytes after statin treatment.7,23 However, most of the mechanistic data implicating a direct pleiotropic effect of statins on the vascular wall are based on cell culture and animal models.3,4,26 Separating the effects of statin therapy exerted by LDL lowering from potential pleiotropic effects is impossible in observational studies or clinical trials because the magnitude of LDL lowering and other effects mediated by HMG CoA reductase inhibition are inextricably linked in individual patients.

An important study by Landmesser at al9 showed that statin treatment improved endothelial function to a significantly greater extent than ezetimibe despite a similar reduction of LDL. Although this study provided strong evidence for a pleiotropic effect of statins on the human vascular endothelium, the mechanisms mediating vascular pleiotropic effects of statins in humans remain unclear.

In the present study, we observed that statin treatment is a strong independent predictor of endothelial function in patients with advanced coronary atherosclerosis. To further investigate the association between statin treatment and endothelial function, we performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in which we observed that atorvastatin treatment for just 3 days improved endothelial function in the brachial artery in patients with atherosclerosis before any significant change in, and independently of, LDL cholesterol levels.

Statins and Oxidative Stress

Clinical evidence suggests that treatment with statins is associated with an early reduction of systemic oxidative stress,19 partly as a result of the reduction of NADPH oxidase activity in the arterial wall.29 Incubation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with atorvastatin rapidly increased NO and reduced ONOO− generation.30 In experimental diabetes mellitus, atorvastatin improved eNOS coupling by increasing the bioavailability of the eNOS cofactor BH4.31 This effect was proposed to be due to upregulation of GTPCH I, the rate-limiting enzyme in BH4 biosynthesis, in the vascular wall.31 Indeed, Hattori et al22 first reported that statins rapidly upregulate GCH1 gene expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, leading to increased BH4 bioavailability.32

Despite the previous reports on the impact of statins on redox state of endothelial cells in experimental animal models, it is not known whether these mechanisms regulate eNOS coupling in the human arterial wall. This is an important question not just for understanding the mechanism of action of statins in human atherosclerosis but also for validating the therapeutic potential of these mechanisms as targets for other novel agents. We now demonstrate for the first time in humans that short-term atorvastatin treatment (40 mg/d for 3 days) reduces vascular O2·− generation in human IMAs of patients with atherosclerosis. By using an ex vivo model of human IMAs, we also demonstrate that atorvastatin reduces arterial O2·− generation even in the absence of LDL. This effect was due largely to an improvement in eNOS coupling in these arteries, and it was reversed by mevalonate, as was confirmed by estimating the effects of atorvastatin and mevalonate on endothelium-derived O2·− in these vessels. These findings suggest that direct inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase in the arterial wall is an important mechanism by which statins exert their vascular effects.

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms by which atorvastatin improves eNOS coupling in the human arterial wall, we examined the impact of treatment on vascular BH4 bioavailability. Because BH4 is a critical cofactor of eNOS that is required to maintain eNOS enzymatic uncoupling in the vascular wall,12 we hypothesized that statin treatment exerts its effects on vascular redox by modifying the BH4-mediated eNOS coupling. Indeed, we observed that short-term atorvastatin treatment had a striking effect on BH4 and total biopterin bioavailability in the arterial wall, indicating that an effect on BH4 biosynthesis occurs in vivo. This finding was also confirmed in the ex vivo model of human arteries in which short-term incubation of IMAs with atorvastatin also increased vascular BH4 and total biopterins. This is due largely to increased biosynthesis of biopterins in the vascular wall, a conclusion supported not only by the increase of vascular total biopterins (including BH4, BH2, and biopterin) but also by the upregulation of GCH1 gene expression and increase in GTPCH activity in these arteries.

Despite previous studies suggesting that the ratio of BH4 to BH2 or BH4 to total biopterins may be important for eNOS biology in endothelial cells,33 atorvastatin treatment had no impact on either plasma or vascular ratios of BH4 to BH2 or BH4 to total biopterins in our clinical study. In the vascular wall of patients with advanced coronary artery disease, these relationships appear to be much more complex. For example, the absolute vascular BH4 was a much stronger determinant of vascular endothelial function or O2·− generation than the ratio of BH4 to BH2 or BH4 to total biopterins,12,34 reflecting the biological complexity in human vessels (which comprise multiple cell types, not just endothelial cells) or technical limitations of biopterin analysis in retrieved clinical material.

In contrast to the effect of atorvastatin on vascular tissue biopterins, we observed that atorvastatin treatment for 3 days was associated with a modest but significant reduction in plasma biopterins. As we have previously documented, there is a discordance between plasma and vascular BH4 levels in human atherosclerosis.12 Plasma biopterins levels are driven by inflammatory mechanisms, and under conditions of systemic low-grade inflammation, which is observed in patients with atherosclerosis, plasma biopterins are inversely correlated with vascular biopterins.12 Therefore, the reduction of plasma biopterins after statin treatment is compatible with a systemic antiinflammatory effect of statins. Statin treatment is also known to increase eNOS expression in endothelial cell culture22 and experimental animal models,31 probably by stabilizing eNOS mRNA.35 However, the limited amount of vascular tissue available for analysis precluded quantification of eNOS expression in this study.

Conclusions

We demonstrate for the first time in humans that statins have a direct impact on the arterial redox state and NO bioavailability by reducing uncoupled eNOS-derived O2·−. This effect was accompanied by an increase in vascular BH4 bioavailability and upregulation of the GCH1 gene encoding GTPCH I. Our findings support the notion that these effects of atorvastatin on the vascular wall are independent of LDL lowering and result directly from inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. These novel findings provide an additional mechanism by which statins exert their beneficial effects in atherosclerosis and identify eNOS coupling and vascular BH4 availability as rational therapeutic targets in vascular disease.

Supplementary Material

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985150/DC1.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme (Marie Curie reintegration grant under grant agreement 224832 to Dr Antoniades). Drs Channon and Casadei are supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG/08/119/26263 and RG/06/001, respectively), The Leducq Foundation, and the Oxford National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Contributor Information

Charalambos Antoniades, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK; First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Constantinos Bakogiannis, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Paul Leeson, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Tomasz J. Guzik, Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland.

Mei-Hua Zhang, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Dimitris Tousoulis, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Alexios S. Antonopoulos, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Michael Demosthenous, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Kyriakoula Marinou, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Ashley Hale, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Andreas Paschalis, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece; Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland; Department of Cardiac Surgery, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Costas Psarros, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Costas Triantafyllou, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Jennifer Bendall, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Barbara Casadei, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Christodoulos Stefanadis, First Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Hippokration Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Keith M. Channon, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Oxford, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

References

- 1.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Reduction in C-reactive protein and LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular event rates after initiation of rosuvastatin: a prospective study of the JUPITER trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, Rifai N, Rose LM, McCabe CH, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorrentino S, Landmesser U. Nonlipid-lowering effects of statins. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2005;7:459–466. doi: 10.1007/s11936-005-0031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Q, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statins: basic research and clinical perspectives. Circ J. 74:818–826. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Bendall JK, Channon KM. Targeting redox signaling in the vascular wall: from basic science to clinical practice. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:329–342. doi: 10.2174/138161209787354230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osto E, Coppolino G, Volpe M, Cosentino F. Restoring the dysfunctional endothelium. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1053–1068. doi: 10.2174/138161207780487566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawlings R, Nohria A, Liu PY, Donnelly J, Creager MA, Ganz P, Selwyn A, Liao JK. Comparison of effects of rosuvastatin (10 mg) versus atorvastatin (40 mg) on rho kinase activity in Caucasian men with a previous atherosclerotic event. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor AJ, Villines TC, Stanek EJ, Devine PJ, Griffen L, Miller M, Weissman NJ, Turco M. Extended-release niacin or ezetimibe and carotid intima-media thickness. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2113–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landmesser U, Bahlmann F, Mueller M, Spiekermann S, Kirchhoff N, Schulz S, Manes C, Fischer D, de Groot K, Fliser D, Fauler G, Marz W, Drexler H. Simvastatin versus ezetimibe: pleiotropic and lipid-lowering effects on endothelial function in humans. Circulation. 2005;111:2356–2363. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164260.82417.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackwell KA, Sorenson JP, Richardson DM, Smith LA, Suda O, Nath K, Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of aging-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: role of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2448–H2453. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00248.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzik TJ, Mussa S, Gastaldi D, Sadowski J, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM. Mechanisms of increased vascular superoxide production in human diabetes mellitus: role of NAD(P)H oxidase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;105:1656–1662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012748.58444.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Crabtree M, Rinze R, Alp N, Cunnington C, Diesch J, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C, Leeson P, Ratnatunga C, et al. Altered plasma versus vascular biopterins in human atherosclerosis reveal relationships between endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling, endothelial function, and inflammation. Circulation. 2007;116:2851–2859. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Warrick N, Shijie C, DeBono J, Lee J, Leeson P, Neubauer S, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Refsum H, et al. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate rapidly improves endothelial function and decreases superoxide production in human vessels: effects on vascular tetrahydrobiopterin availability and eNOS coupling. Circulation. 2006;114:1193–1201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.612325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosentino F, Hurlimann D, Delli Gatti C, Chenevard R, Blau N, Alp NJ, Channon KM, Eto M, Lerch P, Enseleit F, Ruschitzka F, et al. Chronic treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin reverses endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolaemia. Heart. 2008;94:487–492. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.122184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier W, Cosentino F, Lutolf RB, Fleisch M, Seiler C, Hess OM, Meier B, Luscher TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;35:173–178. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200002000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katusic ZS, d’Uscio LV, Nath KA. Vascular protection by tetrahydrobiopterin: progress and therapeutic prospects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattori Y, Hattori S, Wang X, Satoh H, Nakanishi N, Kasai K. Oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin slows the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:865–870. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258946.55438.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cangemi R, Loffredo L, Carnevale R, Perri L, Patrizi MP, Sanguigni V, Pignatelli P, Violi F. Early decrease of oxidative stress by atorvastatin in hypercholesterolaemic patients: effect on circulating vitamin E. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:54–62. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otto A, Fontaine J, Tschirhart E, Fontaine D, Berkenboom G. Rosuvastatin treatment protects against nitrate-induced oxidative stress in eNOS knockout mice: implication of the NAD(P)H oxidase pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:544–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rueckschloss U, Galle J, Holtz J, Zerkowski HR, Morawietz H. Induction of NAD(P)H oxidase by oxidized low-density lipoprotein in human endothelial cells: antioxidative potential of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor therapy. Circulation. 2001;104:1767–1772. doi: 10.1161/hc4001.097056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattori Y, Nakanishi N, Akimoto K, Yoshida M, Kasai K. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor increases GTP cyclohydrolase I mRNA and tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:176–182. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054659.72231.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu PY, Liu YW, Lin LJ, Chen JH, Liao JK. Evidence for statin pleiotropy in humans: differential effects of statins and ezetimibe on rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase activity, endothelial function, and inflammation. Circulation. 2009;119:131–138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antoniades C, Bakogiannis C, Tousoulis D, Reilly S, Zhang MH, Paschalis A, Antonopoulos A, Demosthenous M, Miliou A, Psarros C, Marinou K, et al. Preoperative atorvastatin treatment in CABG patients rapidly improves vein graft redox state by inhibition of Rac1 and NADPH-oxidase activity preoperative atorvastatin treatment in CABG patients rapidly improves vein. Circulation. 2010;122:S66–S73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang CY, Liu PY, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statin therapy: molecular mechanisms and clinical results. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97:1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.12.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laufs U, Liao JK. Post-transcriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA stability by Rho GTPase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24266–24271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morawietz H, Erbs S, Holtz J, Schubert A, Krekler M, Goettsch W, Kuss O, Adams V, Lenk K, Mohr FW, Schuler G, et al. Endothelial protection, AT1 blockade and cholesterol-dependent oxidative stress: the EPAS trial. Circulation. 2006;114(suppl):I-296–I-301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason RP, Kubant R, Heeba G, Jacob RF, Day CA, Medlin YS, Funovics P, Malinski T. Synergistic effect of amlodipine and atorvastatin in reversing LDL-induced endothelial dysfunction. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1798–1806. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel P, Daiber A, Oelze M, Brandt M, Closs E, Xu J, Thum T, Bauersachs J, Ertl G, Zou MH, Forstermann U, et al. Mechanisms underlying recoupling of eNOS by HMG-CoA reductase inhibition in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda N, Hayashi Y, Takahashi Y, Hattori Y. Phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase is diminished in mesenteric arteries from septic rabbits depending on the altered phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway: reversal effect of fluvastatin therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1348–1354. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Al-Wakeel Y, Warrick N, Hale AB, Cai S, Channon KM, Alp NJ. Quantitative regulation of intracellular endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) coupling by both tetrahydrobiopterin-eNOS stoichiometry and biopterin redox status: insights from cells with tetregulated GTP cyclohydrolase I expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1136–1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Van Assche T, Cunnington C, Tegeder I, Lotsch J, Guzik TJ, Leeson P, Diesch J, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C, et al. GCH1 haplotype determines vascular and plasma biopterin availability in coronary artery disease effects on vascular superoxide production and endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosmidou I, Moore JP, Weber M, Searles CD. Statin treatment and 3' polyadenylation of eNOS mRNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2642–2649. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.154492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.