Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Nursing home (NH) residents have high risk for multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) infections. Use of isolation in NH residents with MDRO is not known. This study examines factors associated with isolation precautions use in NH residents with MDRO infection.

DESIGN

Retrospective, cross-sectional analysis.

SETTING

NHs with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ certification October 2010–December 2013.

PARTICIPANTS

MDRO infection positive assessments of elderly, long-stay residents.

MEASUREMENTS

Data obtained from: Minimum Data Set 3.0, Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reporting and Area Health Resource File. Multivariable regression with facility fixed effects was conducted.

RESULTS

The sample included 191,816 assessments of residents with MDRO infection. Of these, isolation use was recorded in 12.8%. Of the NHs reporting MDRO infection in the past year, 31% used isolation at least once among the MDRO infected. Resident characteristics positively associated with isolation use included locomotion: +23.6%, P < .001, and eating: +17.9%, P < .001. Isolation use was lower among those with MDRO history by 14.3%, p< .001. Residents in NHs that received an infection control-related citation in the past year had higher probability of isolation use (+3.4%, P = .02); those in NHs that received a quality of care citation had lower probability of isolation use (−3.3%, P = .03).

CONCLUSION

This is the first study to examine both the new MDS 3.0 isolation and MDRO items. Isolation was infrequently used and the proportion of isolated MDRO infections varied across facilities. Inspection citations were related to isolation use in the following year. Further research is needed to determine if and when isolation should be used to best decrease risk of MDRO transmission and improve the quality of care.

Keywords: Isolation precautions, infection control, nursing homes, large data analysis, Minimum Data Set

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization consider antibiotic resistance to be a serious threat.1, 2 Multidrug resistant organisms (MDROs) are bacteria that are resistant to one or more classes of antibiotics and are frequently resistant to almost all antimicrobial therapies.3 These infections are a particular concern in nursing homes (NHs), where prevalence is increasing and MDRO-infected residents have higher morbidity and mortality than patients in other settings.4, 5

MDROs are transmitted by direct and indirect contact; therefore, standard and contact precautions are widely recommended to prevent MDRO infections.5–7 Standard precautions are a set of infection prevention and control practices that include hand hygiene, gloving, mouth, nose and eye protection when needed and appropriate handling of resident care equipment and laundry.8 Contact precautions include using standard precautions plus: 1) placing an infected individual in a private room, and 2) donning a gown and gloves when in close contact with the patient and the patient’s environment.6 Droplet or airborne precautions include the use of contact precautions plus additional personnel protective equipment. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires NH staff to document the use of contact, droplet or airborne precautions (hereafter referred to as isolation).9

Isolation effectiveness has been studied in acute care settings, but is not well established in NH and may be impractical.7, 10–14 In NHs, an isolated resident “must remain in his/her room [which] requires that all services be brought to the resident (e.g. rehabilitation, social activities, dining, etc.)”.9 Therefore, in addition to requiring a private room, isolation also requires more resources than regular care (e.g., dedicated personal care items and more staff time to put on gowns and gloves when entering the room). The additional cost of isolation in long-term care has been estimated to be $6,000 per isolated resident annually, which has been reported to influence isolation use in facilities with fewer available resources.15–17 Further, isolation is often in conflict with the NH goals of care to promote autonomy, function, dignity and comfort and may therefore present an ethical dilemma.18, 19 As such, NH staff must decide to implement isolation on a case-by-case basis to maximize resident quality of life while minimizing transmission risk.6, 7

Clinical practice guidelines acknowledge that the decision to use isolation in NHs depends on the scenario, client (i.e., demographic and clinical) and system (i.e., facility and location) characteristics.7 However, as many of these factors are perception-driven rather than evidence-based, substantial variation may exist in clinical practice. This study examines client and system characteristics that are associated with isolation use among MDRO-infected residents.

METHODS

A retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of residents in CMS-certified NHs was conducted using national data available as part of larger study (R01NR013687). Resident level data were de-identified and new identification numbers were assigned to unique individuals. The Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center approved this study.

Data Sources

Three datasets were merged: Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0, Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reporting (CASPER) and Area Health Resource File (AHRF). NH staff must complete detailed clinical MDS assessments for all residents as part of the CMS reimbursement eligibility criteria and quality assurance system. The MDS therefore captures data in 96% of U.S. NHs.20 A registered nurse (RN) must coordinate collection of MDS resident health status information and sign-off on each completed assessment. This study used information from MDS assessments collected at regular intervals (admission, quarterly and annual assessments). Only MDS 3.0 data were used as the isolation item is new to this version and active diagnoses (including MDRO) changed since the 2.0 version to improve reliability and validity.21 In a national evaluation study, the MDS variables used in this study all had very good or excellent reliability (measured as agreement between nurse researchers) and validity (between nurse researchers and facility nurses); that is reliability and validity were excellent for isolation (.844 and .901, respectively).22 Additionally, there was high reliability (100% agreement) and excellent validity (Kappa of .971) regarding MDS 3.0 reporting of various MDROs.22

CASPER is also a component of CMS’s quality assurance system and submission of these data is required to obtain CMS reimbursement.23 Data contained in CASPER represent facility characteristics in the two weeks prior to the annual CMS inspection. Area Health Resource File (AHRF) contributed data regarding the local environment in which the NHs operated. AHRF is compiled by Health Resources and Services Administration from 50 databases containing county-level health status, facilities, professions, economic activities, and socioeconomic and environmental characteristics of geographic locations in the U.S.24

MDS assessments were linked to CASPER by facility ID and the date, pairing data from the most recent facility inspection that predated the date of the MDS assessment. AHRF data were then linked by county and year. Therefore, this study included MDS data from October 2010 through December 2013, the most recent prior CASPER data from 2009–2013, and AHRF data from 2010–2013.

Study Sample

Admission, quarterly and annual MDS assessments of MDRO positive residents aged > 64 years were examined. MDRO status was identified using MDS item I1700, which indicates that the infection 1) was diagnosed by an advanced healthcare provider in the past 60 days and 2) had “a direct relationship to the resident’s current functional status, cognitive status, mood or behavior status, medical treatments, nursing monitoring, or risk of death” within the past 7 days.25 The sample included assessments from NHs that were identifiable in both MDS and CASPER data, were freestanding, with 25 to 320 beds (98% of NHs). This eliminated hospital-based and exceptionally small or large facilities, which are not generalizable to the vast majority of NHs.17, 26

Variables

The dependent variable was isolation use. While various practices may be referred to as ‘isolation’ by NH staff, MDS 3.0 isolation item is any contact, droplet and airborne isolation precautions as defined by CDC guidelines and “the resident is in a room alone because of active infection” in the facility within the past 14 days.5, 27

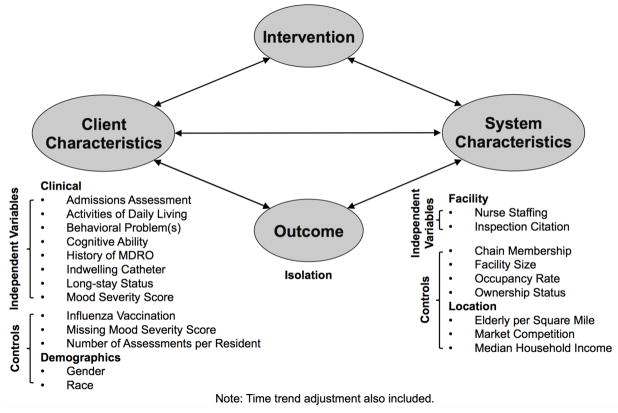

Guided by the Quality Health Outcomes framework, clinical guidelines and previous qualitative research, empirical models were specified including client and system characteristics (see Figure 1).5–7, 28, 29 Client characteristics included admissions assessment, activities of daily living (ADLs), behavioral problem(s), cognitive ability (Alzhiemer’s dementia, non-Alzheimer’s dementia, wandering and ability to make self understood, a component of an established MDS-based cognitive summary measure), history of MDRO (i.e., whether the individual has an MDRO-positive MDS assessment in these data prior to the current assessment), indwelling catheter use, being a long stay resident (i.e., in the NH for > 100 days) and mood severity score. 6, 7, 27, 29, 30 System characteristics potentially associated with isolation use were: nurse staffing (RN, licensed practical nurse and certified nurse aide full time equivalent, FTE, hours per resident per day) and inspection citation (infection control-related and care quality deficiency) on the most recent prior CMS inspection.31

Figure 1. Conceptual model of isolation.

(Among multidrug resistant organism (MDRO) infected nursing home residents, as organized by the Quality Health Outcomes conceptual framework)

Control variables included client demographics (i.e., gender, race), resident influenza vaccination, number of assessments per resident, time trend (assessment date), and facility characteristics (chain membership, facility size, occupancy rate, ownership status).7 Control variables related to NH location included county demand for NH services (elderly per square mile), market competition (Herfindahl index, scale of 0–10,000, with 10,000 indicating complete market share of NH beds in the county), and median household income.32 The number of assessments per resident was included to adjust for multiple measures of unique individuals and dummy variables were included to adjust for missing values of key characteristics if these values were missing > 10% of values. Other variables with missing data (> 10%) were noted and removed. In addition to the above, seasonality (month), age, history of MDRO on a previous assessment and CMS region were assessed to describe the sample.

Data Analysis

Data were cleaned and continuous variables were standardized and categorized into deciles. Descriptive statistics of all independent variables were calculated. Resident assessment descriptions included resident-level clustering to account for repeated measures of unique individuals and facilities, respectively.

Multivariable linear probability models were generated and fit-tested to specify a final model. A preliminary main effects model was developed to assess the functional forms of continuous variables and the outcome and specify each variable in the final model. Categorical dummy variables were jointly assessed; and, if clinically meaningful interaction terms were suspected, these were included if each either individually or jointly contributed to the model. Use of logistic regression models was not feasible given the size of the data set, number of variables, and available computational power. Further, as facility fixed effects were used to mitigate the effect of unobserved NH characteristics, a linear probability model is preferred to avoid bias.33 Goodness of fit of the final model was assessed by C-statistic.

Robustness of final model results was tested by varying assumptions as follows: (A) changing the definition of a long-stay resident from >100 day stay to having an annual assessment, (B) including non-elderly residents, (C) excluding admissions assessments, (D) using state fixed effects and (E) using CMS region fixed effects. Each test was two-sided with alpha = .05. All analyses were conducted in Stata 13.34

RESULTS

The data included 191,816 observations with MDRO infection (138,294 unique residents in 11,773 NHs). The sample represented residents that were predominantly female (59%) and non-Hispanic White (83.9%) with a mean age of 80.5 years (see Table 1). Of these MDRO infection positive assessments, 12.8% reported isolation. Of the NHs reporting MDRO infection in the past year, 31% used isolation at least once among MDRO-infected residents.

Table 1.

Characteristics of nursing home resident assessments showing multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) active infection.

| All MDRO-Infected (N = 191,816) | Isolation (n = 24,557) | No Isolation (n = 167,259) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident Demographics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

| Age in years | 80.5 | 8.5 | 79.8 | 8.4 | 80.6 | 8.5 | < .001 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P | |

| Female gender | 113,321 | 59.1 | 14,020 | 57.1 | 99,301 | 59.4 | < .001 |

| Race | |||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 648 | 0.3 | 68 | 0.3 | 580 | 0.4 | 0.124 |

| Asian | 2,123 | 1.1 | 349 | 1.4 | 1,774 | 1.1 | < .001 |

| Black | 16,456 | 8.6 | 2,524 | 10.3 | 13,932 | 8.3 | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 7,028 | 3.7 | 1,269 | 5.2 | 5,759 | 3.4 | < .001 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 478 | 0.3 | 56 | 0.2 | 431 | 0.3 | 0.409 |

| White | 160,993 | 83.9 | 19,775 | 80.8 | 141,218 | 84.4 | < .001 |

| Clinical Characteristics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

| Activities of daily living score (0–28)a | 18.7 | 5.4 | 19.5 | 5.4 | 18.6 | 5.4 | < 0.001 |

| Mood severity score (0–27)b | 3.1 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P | |

| Behavioral problems | 18,444 | 9.7 | 2,177 | 9.0 | 16,267 | 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| Dementia diagnosis | 66,433 | 34.6 | 7,668 | 31.2 | 58,765 | 35.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of MDRO infection | 53,505 | 27.9 | 3,704 | 15.1 | 49,801 | 29.8 | < 0.001 |

| Proximal MDRO infection (within 6 weeks) | 465 | 0.2 | 75 | 0.3 | 390 | 0.2 | 0.071 |

| Indwelling catheter | 41,497 | 21.6 | 6,514 | 26.5 | 34,983 | 20.9 | < 0.001 |

| Influenza vaccination in current season | 54,616 | 29.3 | 4,960 | 20.9 | 49,656 | 30.6 | < 0.001 |

| Long-stay status (> 100 days in facility) | 48,708 | 25.4 | 3,361 | 13.7 | 45,347 | 27.1 | < 0.001 |

| Wandering | 3,752 | 2.0 | 302 | 1.24 | 3,450 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Makes Self Understood | 136,157 | 71.3 | 17,011 | 69.9 | 119,146 | 71.5 | <0.001 |

| Other Factors | |||||||

| Time trend | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | < .001 |

| Month of assessment (seasonality) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | < .001 |

| State | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | < .001 |

| CMS region | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | < .001 |

Note: Representing 138,294 unique residents in 11,773 facilities. P values calculated by simple logistic regression with robust standard errors (resident-level clustering), significance level is alpha = .05; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Independent performance on all on the activities of daily living is zero and higher score indicates more support is needed.

Higher mood severity score represents worse condition.

Demographics associated with isolation were younger age, male gender, Asian and Black race and Hispanic ethnicity (each P < .001). White race was inversely associated with isolation (P < .001). Clinically significant differences associated with isolation use in bivariate analyses were less independent ADLs (mean: 19.5 vs.18.6, P < .001, the difference between supervision and support on one of seven ADLs), and indwelling catheter use (26.5% vs. 20.9%, P < .001). Assessments showing isolation were less likely to indicate a dementia diagnosis (31.2% vs. 35.1%, P < .001), history of MDRO on the MDS (15.1% vs. 29.8%, P < .001), influenza vaccination (20.9% vs. 30.6%, P < .001), or long-stay status (13.7% vs. 27.1%, P < .001). Isolation use was also correlated with the quarter of assessment (time trend), state and CMS region (each P < .001).

The final model had a C-statistic of .59, indicating fit greater than random chance (See Table 2, the full model output is available in the Supplementary Table S1).35 Needing support with locomotion and eating were associated with a 23.6% and 17.9% increase in probability of isolation respectively (P values < .001). Having an indwelling catheter increased the probability of isolation by 8.2% (P < .001); isolation use was also more likely to be recorded on assessment conducted for admission (48.1%, P < .001). Clinical characteristics associated with lower isolation probability were having a history of MDRO (−14.3%, P < .001), needing support with bed mobility ADLs (−9.2%, P = .01), and wandering. While dementia diagnosis and mood severity score were not significant, both groups of variables jointly contributed to the model (data not shown).

Table 2. Significant associations in linear probability model with facility fixed effects.

Dependent variable: Isolation precautions (188,059 assessments, from 11,830 Nursing Homes)

| Characteristic | Isolation Rate (%) | Change from Reference (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Activities of daily living: Bed mobilitya | |||

| Support needed/activity did not occur | 12.7% | −9.2% | .01 |

| Activities of daily living: Eatinga | |||

| Support needed/activity did not occur | 14.1% | 17.9% | < .001 |

| Activities of daily living: Locomotiona | |||

| Support needed/activity did not occur | 13.2% | 23.6% | < .001 |

| Admissions assessment | 15.0% | 48.1% | < .001 |

| History of MDRO-positive MDS assessment | 11.5% | −14.3% | < .001 |

| Indwelling catheter | 13.7% | 8.2% | < .001 |

| Wandering (reference: no wandering) | |||

| 1–3 days of last week | 10.34% | −19.84% | < .001 |

| 4–6 days of last week | 9.07% | −29.69% | < .001 |

| Daily wandering in last week | 10.78% | −16.43% | .02 |

| Facility characteristics | |||

| Citation on last inspection: Infection control | 13.12% | 3.39% | .02 |

| Citation on last inspection: Care quality | 12.71% | −3.27% | .03 |

| Staffing: Registered Nurse (RN)b,c | |||

| 0.00–0.23 | 13.9% | 6.4% | .45 |

| 0.23–0.46 | 12.4% | −5.0% | .06 |

| 0.46–0.69 (Reference) | 13.0% | -- | -- |

| 0.69–0.92 | 13.0% | −0.3% | .87 |

| 0.92–1.15 | 13.1% | 0.6% | .84 |

| 1.15–1.39 | 12.7% | −2.8% | .51 |

| 1.39–1.62 | 13.4% | 2.8% | .63 |

| 1.62–1.85 | 10.6% | −18.9% | .02 |

| 1.85–2.08 | 9.6% | −26.7% | .01 |

| 2.08–2.31 | 14.4% | 10.1% | .45 |

| Top 1% of RN staffing levels | 4.8% | −62.7% | < .001 |

| Isolation Rate at Mean | 1 SD Change | P | |

| Staffing: Licensed practical nursec,d | 12.5% | −2.5% | .015e |

| Staffing: Certified nurse aidec,d | 12.3% | −4.13% | .005e |

Note: C-stat: .59, significance level is alpha = .05, SD = standard deviation, MDRO = multidrug resistant organism, MDS = Minimum Data Set.

Activities of daily living (ADLs) reference categories are “independent”;

Standardized and divided into 10 categories by value;

Highest 1% of values excluded as outliers, measured in full-time equivalent hours per resident per day;

squared values included;

P value from joint contribution (F) test.

Control variables (not shown): Race, gender, assessments per resident, influenza vaccination, facility characteristics (chain membership, ownership status, facility size, occupancy rate), location characteristics (Herfindahl index and county median income) and interaction terms (makes self understood and verbal behavior problems, makes self understood and dementia, dementia and hygiene ADLs, dementia and eating ADLs, dementia and toileting ADLs, dementia and dressing ADLs, Herfindahl index and elderly per square mile, Herfindahl index and median household income and median household income and elderly per square mile).

NHs with 1.62–2.08 RN FTE per resident per day were less likely to use isolation than those with 0.46–0.69 FTEs. Both higher licensed practical nurses and certified nurse aide staffing were associated with lower isolation use. MDRO-infected residents in NHs that received an infection control-related citation in the past year were associated with a 3.4% increased probability of isolation use (P = .02), conversely those in a NH that received a quality of care citation in the past year were less likely to be in isolation (−3.3%, P = .03).

The above results were robust (data not shown) regarding (A) different long-stay definition and (B) including residents under age 65. When (C) changing the sample to exclude admissions assessments, associations with needing eating support and RN staffing level became weaker. Using state fixed effects (D) verbal behavioral problems (> 4 days of the last week) and LPN staffing became positively associated and having an indwelling catheter had a stronger positive association. RN staffing became negatively associated with isolation use. Using CMS region fixed effects (E) changed these same associations as the state fixed effects model and weakened relationships with aide staffing and isolation use and strengthened the positive association of MDRO history and the negative association of long-stay status.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine both the new MDS 3.0 isolation and MDRO items and provides novel understanding about nationwide isolation use in NHs. MDRO-infected residents were rarely in isolation (12.8%). Further, there was wide variation across NHs in the proportion of MDRO-infected residents in isolation, with 69% of NHs having no isolation concurrent with MDRO infection. These rates were surprising considering that 20% of all hospital inpatients are isolated at any given time.36 This isolation pattern warrants further investigation as to whether current use is effective to prevent MDRO transmission.

Many associations with isolation were consistent with findings of previous studies of care goals and infection prevention practices in this setting.16, 29, 37 For example, other researchers found that clinical history was uncertain for some admissions, and some NHs have policies to address transmission risk from new residents with pre-emptive isolation.29, 38 In previous qualitative research, we found that the quality of life and preserving autonomy were high priorities among NH staff making isolation decisions.29 Goals to preserve resident psychosocial health and functionality may explain why some NHs were not using isolation as often for residents who needed support with eating and locomotion ADLs.

However, the relationship between isolation and having an indwelling catheter was unexpected. While these data did not indicate whether the MDRO infection was in the catheter or elsewhere, American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) guidelines indicate that residents with an infection within an indwelling catheter may pose lower transmission risk, and therefore may be less likely to need isolation than those with an infection in another location.7 It is not clear why those with MDRO and an indwelling catheter were more likely to be isolated and further research is warranted.

Facility resources may be influencing patterns of isolation use. Some nurses may perceive isolation as a time-intensive practice and be less likely to implement isolation among residents who require more frequent nursing care.39 This may explain the negative association between needing bed mobility support and isolation use, as these residents must be repositioned at least every 2 hours to avoid pressure ulcers (without a pressure-reducing device).39, 40 Further, there was an inverse relationship between wandering and isolation use, which may be due to a perception that residents who wander need more attention from nursing staff to ensure the resident stays in a private room.29 Similarly, those who need assistance with locomotion may be more likely to be isolated because they may require less staff oversight to ensure compliance. While it was not possible to determine from these data whether the additional resource burden to the NH influenced isolation, it would be consistent with a survey in which 21.4% of NHs reported that they could not use isolation due to a lack of either dedicated equipment or a private room.37

CMS inspections also affect infection control practices. There was a negative relationship between receiving a quality of care citation and isolation over the next year. While the cause is unclear, this relationship may indicate that these NHs have had to divert resources from infection control to improve other care areas. It may be important to determine if NHs have reasonable resources to meet the regulations and recommended clinical practices. Additionally, NHs that received an infection control-related citation in the past year were more likely to use isolation. It is possible, given that limited infection-related training and knowledge previously identified among NH staff, that those who received a citation would have been recently informed of recommended practices and therefore more likely to use isolation.19, 29 If this was the case, further education regarding the appropriate use of isolation may be needed to improve care. Previously, we have found that infection control training for NH staff is associated with fewer infection control-related citations.29, 41

The influence of CMS regulation on NH practice may also explain the relationship between isolation and wandering. An inverse association with wandering may exist because staff did not want to imply an isolation protocol breach has taken place (i.e., resident left the room). Non-compliance may result in increased regulatory oversight and financial penalties.42

From these data, it was not possible to confirm the rationale for isolation use nor the effectiveness of the practice. Future researchers should identify whether a specific isolation decision is appropriate (i.e., transmission to another resident is likely without isolation use), especially considering the CDC and the AMDA recommended implementing infection prevention interventions on case by case basis in this setting and the low rate of isolation use identified here.3, 5, 7 It may be that an optimally-functioning NH can be using isolation rarely given the particular client and system characteristics resulting in low probability of transmission. The evidence regarding the effectiveness of isolation precautions is poor, let alone in the long-term care setting and with specific resident clinical characteristics and needs.11–13 Therefore, it would also be beneficial to understand whether use of isolation should be limited to high-risk transmission activities (e.g., assisting with hygiene ADLs) and/or high-risk resident populations.

Finally, as NH staffing levels have been previously associated with high care quality, it was surprising that some higher levels of RNs, licensed practical nurse and certified nurse aide staffing were associated with less isolation use compared to the highest levels of each staff type.43 Within the facility fixed effects models, staffing levels within an individual facility may act as a proxy for higher overall infection rates (i.e., at times with more temporary workers or infection outbreaks) and thereby when less available private rooms for each MDRO-infected resident. Therefore, future investigators should assess whether the facility-wide rate of MDRO and other infections are associated with isolation use.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include use of a large, representative dataset that allowed for a comprehensive assessment of client and system characteristics associated with isolation. Another strength was the robustness of these findings when model inputs varied. A limitation of the MDS was that assessments offer a snapshot of resident health with variable look-back periods by item.44 It did not indicate if the resident left the facility for less than 30 days (i.e., hospital admission). The MDS did not record MDRO infection type, location, severity or source, nor did it include information regarding available resources, equipment or private rooms, which may influence isolation use.7 This MDRO-infected resident sample may have underrepresented the use of isolation for other organisms (e.g., norovirus) and this analysis did not include hospice as a factor that may influence isolation use. This may explain the moderate C-statistic for the final model. Further, the reason for isolation was not identified on the MDS and it is possible that isolated residents in this sample may represent isolation for conditions other than MDRO infection; and the different look-back periods for MDRO and isolation (7 vs. 14 days) could mean that isolation could have taken place before MDRO-infection. These data do not include cohorting, other infection control practices or prevalence of infection in the NH for which isolation may be required. Use of other care practices may cause variation in the observed use of isolation. Personnel at specific types of facilities (e.g., government versus privately owned) and or in various regions (e.g., California versus Vermont) may compile and submit these data differently despite the clear definitions in the user manual.45 Furthermore, we controlled for many facility characteristics, including using facility fixed-effects, which was a strength of the study.

Conclusions

Isolation was used for few MDRO-infected residents and most NHs did not place MDRO-infected residents in isolation. These findings have implications for education, policy and research. Additional training may be needed to ensure isolation is used appropriately in NHs. However, training may be more efficient to reduce infection with availability of new effectiveness evidence. Research is needed to determine if isolation is effective to prevent MDRO transmission, especially compared to other practices intended to reduce transmission. Future research should also address whether nurse staffing is a proxy for other system characteristics affecting isolation use. This evidence can inform policies, standardize, and perhaps simplify guidelines and thereby ensure consistent, high quality care for residents across NHs. As NH inspection citations were associated with future isolation use, inspections may be a useful tool to align practice with new evidence and policies as they become available.

Supplementary Material

Results of full multivariable linear probability model (1) with facility-level clustered robust standard errors and (2) facility-level fixed effects

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Nicholas Castle, Jingjing Shang, Rebecca Schnall and Elaine Larson to study design.

Funding source:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR013687 and F31 NR015176), the Eastern Nursing Research Society and the Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these sponsors. This study was presented in part at the Eastern Nursing Research Society 2016 Annual Conference in Pittsburgh, PA and at the Interdisciplinary Research Group on Nursing Issues of AcademyHealth at the Annual Research Meeting 2016 in Boston, MA.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Study concept and design: Cohen, Stone, and Dick. Acquisition of data: Stone and Dick. Analysis and interpretation of data: Cohen. Drafting of the manuscript: Cohen. Revision and approval of the manuscript: All authors.

Sponsor’s role: The study sponsors, The National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR), Eastern Nursing Research Society and the Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science, had no role in designing this research, preforming the study, or completing the corresponding manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Checklist:

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | * Author 1: Catherine Cohen | Author 2: Andrew Dick | Author 3: Patricia Stone | Etc. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | |||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | |||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | |||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | |||||

| Patents | X | X | X | |||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | |||||

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. 2013 (online). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/

- 2.World Health Organization. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Antimicrobial resistance global report on surveillance. (online). Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al. Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in health care settings, 2006. Am J Infect Control. 2006;35:S165–S193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzig CT, Dick A, Sorbero M, et al. Longitudinal infection trends in United States nursing homes, 2006–2011 [Abstract] Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014 Fall;2014(Suppl 1):S258–S259. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S, et al. SHEA/APIC guideline: Infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility, July 2008. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:785–814. doi: 10.1086/592416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings (online) doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.American Medical Directors Association. Common infections in the long-term care setting clinical practice guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2011. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 17, 2016];Precautions to prevent spread of MRSA (online) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/healthcare/clinicians/precautions.html.

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument user’s manual. 2012. pp. I–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Agata EM, Horn MA, Ruan S, et al. Efficacy of infection control interventions in reducing the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms in the hospital setting. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen CC, Cohen B, Shang J. Effectiveness of contact precautions against multidrug-resistant organism transmission in acute care: A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2015;90:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan DJ, Murthy R, Munoz-Price LS, et al. Reconsidering contact precautions for endemic Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1163–1172. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kullar R, Vassallo A, Turkel S, et al. Degowning the controversies of contact precautions for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A review. Am J Infect Control. 2015;44:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mody L, Bradley SF, Galecki A, et al. Conceptual model for reducing infections and antimicrobial resistance in skilled nursing facilities: Focusing on residents with indwelling devices. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:654–661. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks E, Medina-Walpole A, Gillespie S, et al. Elimination of contact precautions for nursing home residents colonized with multi-drug resistant organisms: Substantial cost reduction and improved quality of life. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:B19–B19. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreman T, Hu J, Pottinger J, et al. Survey of long-term-care facilities in Iowa for policies and practices regarding residents with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Infec Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:811–815. doi: 10.1086/502498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 1, 2016];National action plan to prevent health care-associated infections: Road map to elimination (online) Available at: https://health.gov/hcq/prevent-hai-action-plan.asp-phase3.

- 18.Unwin BK, Porvaznik M, Spoelhof GD. Nursing home care: Part I—principles and pitfalls of practice. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:1219–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone PW, Herzig CT, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, et al. Understanding infection prevention and control in nursing homes: A qualitative study. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castle N, Wagner L, Ferguson J, et al. Hand hygiene deficiency citations in nursing homes. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33:24–50. doi: 10.1177/0733464812449903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed December 17, 2015];MDS 3.0 for nursing homes and swing bed providers (online) Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIMDS30.html.

- 22.Saliba D, Buchanan J. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Development and validation of a revised nursing home assessment tool: MDS 3.0 (online) Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/downloads/mds30finalreport.pdf.

- 23.American Health Care Association. [Accessed September 13, 2013];What is OSCAR Data? (online) Available at: http://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/oscar_data/Pages/WhatisOSCARData.aspx.

- 24.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [Accessed October 12, 2013];Area Resource File (AHRF) (online) Available at: http://www.arf.hrsa.gov/faqs.htm - 1.

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 1, 2016];MDS 3.0 RAI manual v1.11 replacement manual pages and change tables October 2013 (online) Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursinghomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html.

- 26.Zhang NJ, Paek SC, Wan TTH. Reliability estimates of clinical measures between Minimum Data Set and Online Survey Certification and Reporting data of US nursing homes. Med Care. 2009;47:492–495. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e31818c014b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.RTI International. [Accessed August 1, 2016];MDS 3.0 quality measures user’s manual v8.0 04-15-2013 (online) Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-User%E2%80%99s-Manual-V80.pdf.

- 28.Mitchell PH, Ferketich S, Jennings BM. Quality health outcomes model. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1998;30:43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen CC, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Herzig CT, et al. Infection prevention and control in nursing homes: A qualitative study of decision-making regarding isolation-based practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:630–636. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castle NG, Wagner LM, Ferguson-Rome JC, et al. Nursing home deficiency citations for infection control. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Department of Justice. [Accessed January 20, 2016];Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (online) Available at: http://www.justice.gov/atr/herfindahl-hirschman-index.

- 33.Greene WH. [Accessed August 1, 2016];The behavior of the fixed effects estimator in nonlinear models (online) Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1292651.

- 34.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosmer DW. Applied logistic regression. 3. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Day HR, Perencevich EN, Harris AD, et al. Do contact precautions cause depression? A two-year study at a tertiary care medical centre. J Hosp Infect. 2011;79:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye Z, Mukamel DB, Huang SS, et al. Healthcare-associated pathogens and nursing home policies and practices: Results from a national survey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:759–766. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, et al. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: A qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1095–1102. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillemin I, Marrel A, Beriot-Mathiot A, et al. How do Clostridium difficile infections affect nurses’ everyday hospital work: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 2):38–45. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas DR. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen CC, Engberg J, Herzig CT, et al. Nursing homes in states with infection control training or infection reporting have reduced infection control deficiency citations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1475–1476. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 26, 2013];Nursing homes: About nursing home inspections (online) Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/nursing/aboutinspections.asp.

- 43.Castle NG, Engberg J. The influence of staffing characteristics on quality of care in nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1822–1847. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Research Data Assistance Center. [Accessed October 18, 2013];Long-term care Minimum Data Set 3.0 (online) Available at: http://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mds-3.0/data-documentation.

- 45.Mor V, Caswell C, Littlehale S, et al. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Changes in the quality of nursing homes in the US: A review and data update (online) Available at: https://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/quality/documents/changesinnursinghomequality.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of full multivariable linear probability model (1) with facility-level clustered robust standard errors and (2) facility-level fixed effects