Abstract

The retroviral integrase (IN) carries out the integration of a dsDNA copy of the viral genome into the host DNA, an essential step for viral replication. All IN proteins have three general domains, the N-terminal domain (NTD), the catalytic core domain (CCD), and the C-terminal domain (CTD). The NTD includes an HHCC zinc finger-like motif, which is conserved in all retroviral IN proteins. Two crystal structures of Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) IN N-terminal region (NTR) constructs that both include an N-terminal extension domain (NED, residues 1-44) and an HHCC zinc-finger NTD (residues 45-105), in two crystal forms are reported. The structures of IN NTR constructs encoding residues 1-105 (NTR1-105) and 8-105 (NTR8-105) were determined at 2.7 and 2.15 Å resolution, respectively and belong to different space groups. While both crystal forms have similar protomer structures, NTR1-105 packs as a dimer and NTR8-105 packs as a tetramer in the asymmetric unit. The structure of the NED consists of three anti-parallel β-strands and an α-helix, similar to the NED of prototype foamy virus (PFV) IN. These three β-strands form an extended β-sheet with another β-strand in the HHCC Zn2+ binding domain, which is a unique structural feature for the M-MuLV IN. The HHCC Zn2+ binding domain structure is similar to that in HIV and PFV INs, with variations within the loop regions. Differences between the PFV and MLV IN NEDs localize at regions identified to interact with the PFV LTR and are compared with established biochemical and virological data for M-MuLV.

Keywords: Retroviral integrase, N-terminal extension domain, Zn2+ finger protein, Homology modeling, N-terminal domain, DNA integration

Introduction

The integration of double-stranded retroviral DNA into the host chromatin is catalyzed by the viral encoded integrase (IN) protein. The IN protein is comprised of an N-terminal zinc binding domain (NTD), a catalytic core domain (CCD), and a C-terminal domain (CTD) (for a review see1). Integration involves the coordinated assembly of the IN proteins, the two viral DNA termini, and the host target DNA into an intasome complex. Insights into the assembled intasome have been obtained from structural studies of the PFV IN2–5, RSV IN6, MMTV IN7 and molecular modeling based upon these structures. Target DNA binding sites localize within the CCD and CTD4,8–10, whereas viral long-terminal repeat (LTR) DNA recognition localizes to all three domains, including the N-terminal region (residues 1-105)2,4,6,7.

The IN NTD contains two conserved histidine and two conserved cysteine residues (HHCC), which are required for Zn2+ binding11. In HIV and RSV IN proteins, the NTD containing this invariable HHCC motif is ~ 50 residues in length12–14. However, M-MuLV IN has an additional 44 residues preceding the HHCC Zn-finger subdomain15,16, with 19% sequence similarity (ClustalW) with the NED found in the prototype foamy virus (PFV) IN2. We refer to this segment of NED followed by NTD, of M-MuLV, PFV, and related INs, as the N-terminal Region (NTR, residues 1-105) of IN. In PFV IN, the NTR consists of the N-terminal extension domain (NED, residues 1-48) and the N-terminal domain (NTD, residues 51-105)2.

The IN protein is expressed within the Gag-Pol precursor protein and is excised through proteolytic cleavage by the viral protease within the viral particle1,17. Upon infection, the IN protein is associated with the reverse transcription complex (RTC), which transitions to the preintegration complex (PIC) upon formation of the newly generated double-stranded viral DNA1,18. For M-MuLV, proteins associated with the PIC include the capsid (CA), p12, IN viral proteins and cellular proteins including barrier-to-autointegration factor 1 (BAF)18–22. Ultimately, integration occurs in the nucleus through interaction of the M-MuLV IN protein with the cellular bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins23–26. The conformational states of the IN, from the precursor state through the intasome complex, must therefore be highly dynamic.

When expressed as isolated domains, the NTD of HIV and NTR of M-MuLV IN form dimers in solution27–29. The HIV IN protein, lacking an NED subdomain, dimerizes through its HHCC Zn-finger27. However, the HHCC Zn-finger (residues 51-105) of M-MuLV IN alone is not sufficient for stable dimer formation29. The NTR segment (i.e. NED plus NTD) of M-MuLV IN is capable of complementing IN bearing NTR deletions, as measured by in vitro IN activity assays28,29. However, the HHCC Zn-finger alone is not sufficient for complementation29. Therefore, the NED subdomain is required for M-MuLV IN activity29. Within the PFV intasome, the IN NTR is observed as a monomer; and dimers of PFV NTR are not observed within any available crystal structures2,4.

To gain insight into structure-function relationships of the M-MuLV IN NTR, we determined its 3-dimensional (3D) structure. Here we report X-ray crystal structures of M-MuLV IN NTR crystallized in two crystal forms. Form I, a construct containing residues 1-105 (with a C-terminal His6 tag), in space group R32, was determined to 2.7 Å resolution. Form II, a shorter construct consisting of residues 8-105, IN8-105, in space group P21, was solved to 2.15 Å resolution. These structures reveal that key residues, shown to be important for strand transfer activity29 contribute to an extensive basic surface. By analogy with the X-ray crystal structure of PFV IN bound to the viral LTR2, this basic surface of M-MuLV appears to function in binding the LTR DNA, a key step in the mechanism of IN integration. Overall, the structural and subdomain organization of the M-MuLV IN NTR is similar to that of PFV IN NTR, with some key structural differences that include regions of the PFV NTR that are important in binding the LTR in the intasome complex2. The key LTR DNA binding residues of PFV IN NTR are biophysically quite different than the corresponding residues in the M-MuLV IN NTR structure. This suggests that the details of the recognition of the M-MuLV IN for its cognate LTR DNA sequences are distinct from that of the PFV IN:LTR DNA interaction.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

A DNA fragment encoding M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 (residues 1-105) was generated by PCR from the full-length gene and cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET21_NESG30, with a short C-terminal purification tag “LEHHHHHH”. The plasmid was then transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Strategene). These cells were grown in either minimal media containing selenium-methionine or LB media (1L) at 37 °C to O.D.600 of ~0.8 units, and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside overnight at 17 °C. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in 1x PBS buffer by mild sonication to release the soluble target protein. After high-speed centrifugation, the supernatant was applied to a 5 ml His-tag affinity column (GE Healthcare), and eluted with a linear (50–500 mM) imidazole gradient. Further purification was accomplished by size exclusion chromatography using a HighLoad 26/60 Superdex S75 column (GE Healthcare). The purified protein was over 95% pure based on SDS PAGE, and was also validated by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (13.6 kDa).

In an effort to optimize crystallization, a second IN NTR construct (IN NTR8-105, residues 8-105) was generated by PCR and expressed in pET15-TEV-NESG30,31, encoding a TEV protease cleavage site after the N-terminal His-tag. The procedures used for the expression and purification of IN NTR8-105 are similar to the procedures described above, with the additional step of treating with TEV protease followed by passing the cleaved product through a His-tag affinity column (GE Healthcare), and a final gel filtration purification using a Superdex S75 column, as described elsewhere30,31.

Crystallization and data collection

The purified M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in 0.05 M MES at pH 6.5 and stored at −80°C prior to crystallization. The initial crystallization screening was performed at the high-throughput screening (HTS) facility at Hauptman-Woodward Research Institute (HWI) located in Buffalo, NY, where 1536 crystallization conditions were screened using the microbatch method32. Initial crystallization hits were further optimized manually to obtain diffraction quality crystals. The addition of detergents was important in improving the diffraction quality of the crystals. Optimal conditions for crystallization were obtained at room temperature in 2.0 M sodium malonate, 0.1 M sodium acetate at pH 5.0, in the presence of 0.05% Anapoe X-305.

Diffraction of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 crystals was first tested using a Rigaku R-AXIS IV++ detector. The crystals were harvested directly from the drops and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. A complete three-wavelength multiple anomalous dispersion (MAD) data set to 2.7 Å was then collected at beamline X4A of the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). The HKL2000 package33 was used to index, integrate and scale the data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| NTR1-105 | NTR8-105 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | R32 | P21 | ||

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 112.82, 112.82, 115.53 | 44.66, 38.44, 135.27 | ||

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 91.70, 90 | ||

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97917 | 0.97940 | 0.96863 | 1.07500 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.8 (2.80–2.90)* | 2.7 (2.70–2.80) | 3.0 (3.00–3.11) | 2.15 (2.15–2.23) |

| Rmerge (%) | 10.5 (62.0) | 10.0 (88.6) | 10.3 (51.4) | 8.1 (60.5) |

| I/σI | 22.56 (3.52) | 21.55 (2.56) | 22.82 (4.59) | 12.10 (2.40) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (100) | 99.8 (100) | 99.7 (100) | 98.1 (97.0) |

| Redundancy | 8.8 (8.8) | 10.2 (9.6) | 8.0 (8.1) | 6.7 (6.2) |

|

| ||||

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.69 | 2.15 | ||

| No. reflections | 7829 | 24869 | ||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 22.9/27.4 | 23.4/26.5 | ||

| No. atoms | ||||

| Protein | 1574 | 3103 | ||

| Ligand/ion | 10 | 120 | ||

| Water | 36 | 61 | ||

| B-factors (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 94.83 | 62.52 | ||

| Ligand/ion | 70.67 | 80.06 | ||

| Water | 71.49 | 52.04 | ||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.674 | 1.321 | ||

| Bond angles (°) | 0.004 | 0.010 | ||

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 was concentrated to 5 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 0.02% NaN3, and screened at HWI for initial crystallization screening, as described above 32, followed by manual optimization. The best crystals of IN8-105 NTR were grown in 1.0 M K2HPO4, 0.1 M sodium acetate at pH 4.6, in the presence of 0.05% Anapoe X-305. The crystals were briefly soaked in cryo buffer containing mother liquid plus 15% glycerol and flash frozen in liquid N2. Preliminary diffraction analysis was carried out with a home X-ray source, and provided diffraction to 2.5 Å resolution. Higher resolution data to 2.15 Å were collected at NSLS beamline X29A at BNL using their mail-in data collection service34. The data processing was performed by HKL200033. The resulting crystallographic statistics are listed in Table 1.

Structure determination and refinement

The crystal structure of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 was determined by MAD methods using the program Solve35. Density modification and automated model building were performed with Resolve36. Initially, approximately 50% of the residues could be automatically built by Resolve. Significant effort was spent on manual tracing and model building, and the model was gradually completed. Structure refinement was carried out with program PHENIX37, and the final refined structure was validated by MOLPROBITY38. Manual model building and adjustment were performed using COOT39. The final structure refinement and geometry statistics are summarized in Table 1.

The crystal structure of IN NTR8-105 was determined by molecular replacement with program Phaser40, using the structure of IN NTR1-105 as a search model. Structure refinement, model building and validation were all performed as detailed above. The final structure was optimized with PDB_REDO41, which improved the model quality. The statistics for the final structure refinement and model geometry are summarized in Table 1.

Interface residues and buried surface areas for the two crystal structures were computed using the EBI-PISA server42.

Results and Discussion

Overall structure of M-MuLV IN-NTR1-105

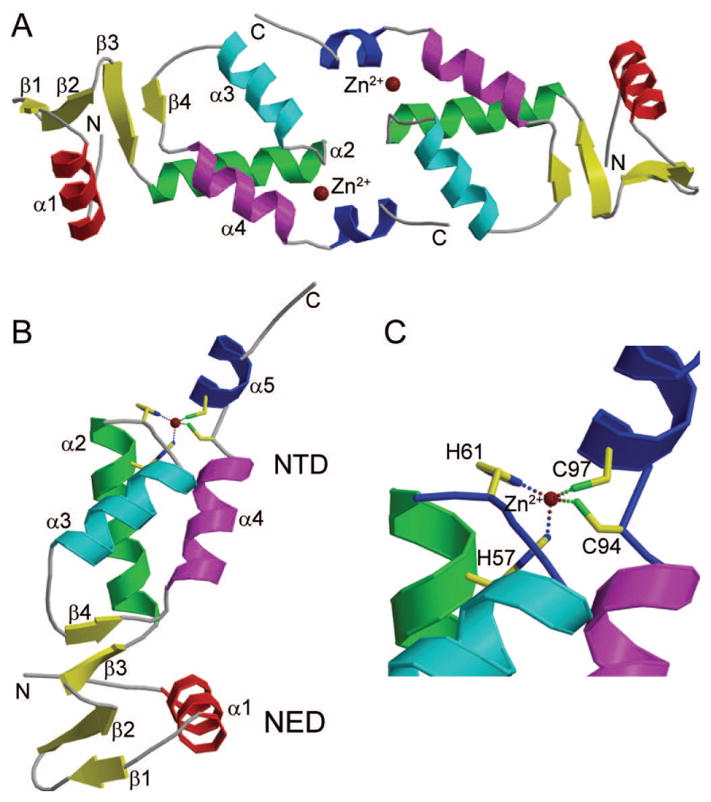

The crystals of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105, belong to space group R32, with two M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1A). The structure was determined by MAD to 2.7 Å resolution. The dimer interface is relatively small, burying only 378 Å2 of surface, and mainly includes the following key interacting residues of T60, L62, S63, K66, A69, L70, R73, Q99, V100, N101, A102 and S103. The first 10 amino acid residues in both molecules are missing due to lack of electron densities, suggesting that these first 10 residues are highly flexible. The M-MuLV protease cleavage recognition site for Gag-Pol polyprotein processing resides in these initial 5 IN residues17. The C-terminal tag (LEHHHHHH) was also not detected at this resolution. The two molecules in the asymmetric unit are very similar, having a backbone Cα RMSD of 0.008 Å for residues 12-104. Each molecule contains both the NED and NTD HHCC Zn2+ -finger domains (Fig. 1B). The ion Zn2+ is coordinated by residues H57, H61, C94 and C97 (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Overall crystal structure of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105.

(A) The two M-MuLV IN NTD1-105 molecules in the asymmetric unit. The two Zn2+ ions are shown as brown spheres and labeled. N- and C-termini in both molecules are indicated with “N” and “C”, respectively. (B) Each M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 has two regions, the NED and NTD subdomain. There are 3 β-strands and one α-helix in the NED subdomain, and four α-helices and 1 short β-strand in the NTD subdomain. (C) The Zn2+ binding site in the NTD subdomain, which consists of residues H57, H61, C94 and C97.

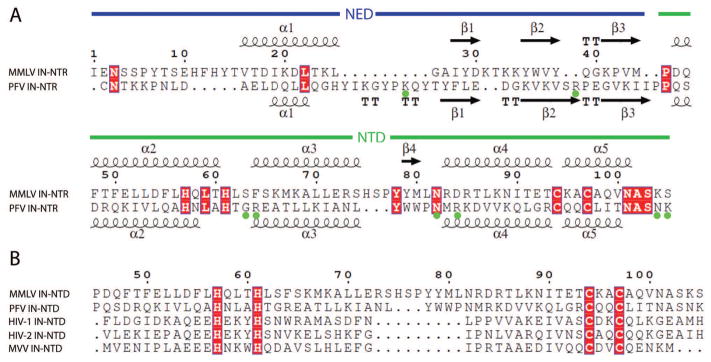

The NED is composed of three short anti-parallel β-strands and one α-helix (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the β3 strand of the NED interacts with the β4 strand in the α3-α4 loop of the HHCC Zn2+ binding domain, forming an extended β-sheet (Fig. 1B), which stabilizes the orientations of the NED and NTD with respect to one another. Similar to other IN proteins, the M-MuLV IN NTD HHCC Zn2+-finger domain is composed of 3 core helices (α2, α3 and α4), and a C-terminal α-helix α5 (Fig. 2A). Additionally, there is a short β-strand within the α3-α4 loop, β4, previously not identified in other IN proteins (Fig. 2A). Sequence alignment of the M-MuLV NTD with that of PFV, HIV-1, HIV-2, and maedi-visna virus (MVV) (Fig. 2B) indicates that the α3-α4 loop in M-MuLV IN (residues 75-82) is longer than that in all other IN proteins, allowing for formation of the β-sheet that bridges the NED and NTD regions.

Figure 2. Sequence and structural alignment of M-MuLV (MMLV).

(A) Structure-based sequence alignment of M-MuLV and PFV IN-NTR. The NED is defined as residues 1-48 (blue line), and the NTD as residues 51-102 (green line) of PFV2. The 8 residues in PFV IN NTR marked with green dots are those contacting DNA directly in the complex formed between the PFV IN NTR and LTR DNA2. TT- tight turns. (B) Sequence alignment of the NTD regions among M-MuLV, PFV, HIV-1, HIV-2, and MVV INs. Dark red boxes indicate residues that show sequence identity. Sequence numbering in panels A and B is for M-MuLV IN. Sequence alignments and identities were generated using the ESpript server47.

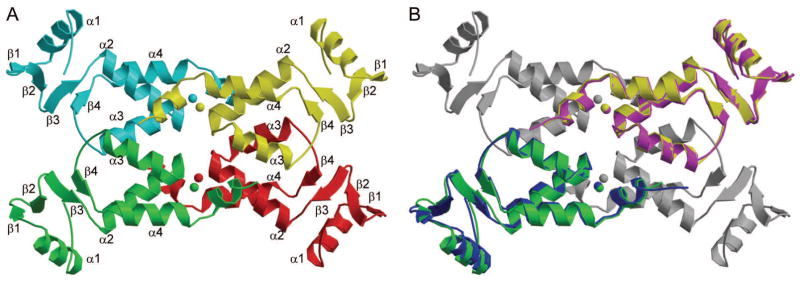

Overall structure of M-MuLV IN8-105

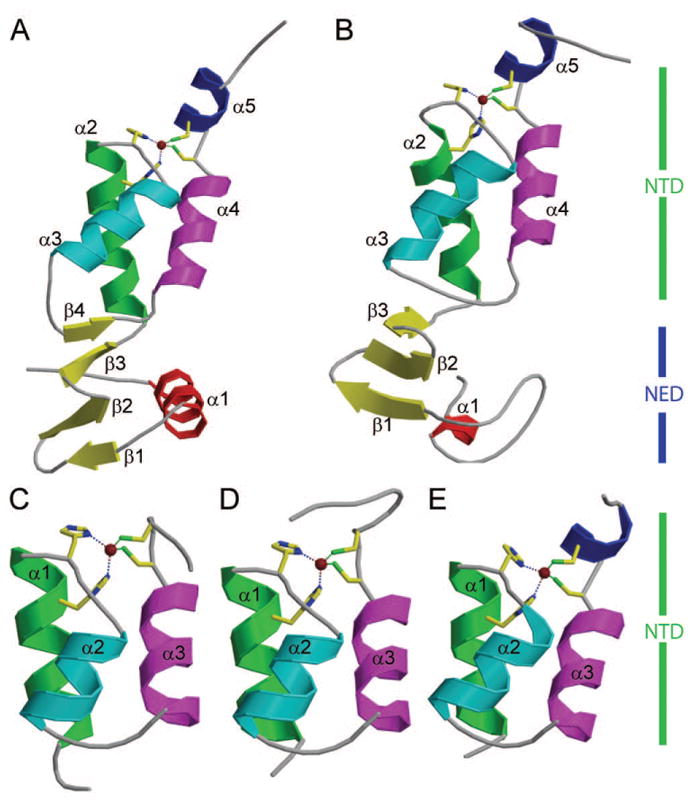

Treatment of the M-MuLV IN8-105 construct with TEV removes the N-terminal His6 tag and results with the N-terminal Ser-His sequence upstream of the IN8-105 sequence. The resulting IN8-105 construct was crystallized, and its structure determined to 2.15 Å resolution (Fig. 3A, B). These crystals belong to space group P21, where there are four molecules in the asymmetric unit. Although M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 is a shorter protein (lacking both the His tag and seven N-terminal IN residues), crystallized under different conditions, and belongs to a different space group compared to M-MuLV IN NTR1-105, the structures of the individual protomers are nearly identical.

Figure 3. Crystal structure of M-MuLV IN8-105.

(A) The four molecules in the asymmetric unit, each in shown in different colors, form a dimer-of-dimers. The Zn2+ ions are colored in the same as the protein in which it is located. (B) Superimposition of the common dimer from the M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 structure onto M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 structure. The two monomers used in fitting in M-MuLV IN8-105 are colored the same as in (A), and the other two are in gray. The two monomers from M-MuLV IN NTD1-105 are colored in magenta and blue, respectively.

Although these two structures were from different space groups, the molecular packing in the respective crystals is very similar. In the M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 structure, the 4 molecules form a butterfly shaped symmetric “dimer-of-dimers”. A total of six interacting interfaces are present, burying a combined area of 1996.8 Å2. The interfaces are stabilized by 1 salt bridge and 11 hydrogen bonded interactions. These include the salt bridge between D54 (chain A) and K95 (chain D) and the following hydrogen bonded interactions – Q58 (chain C) and Q58 (chain B), Q58 (chain C) and H61 (chain B), K66 (chain B) and N101 (chain A), Q99 (chain B) and R73 (chain A), N101 (chain B) and K66 (chain A), S103 (chain B) and R73 (chain A), H75 (chain C) and Y78 (chain A), Y78 (chain C) and H75 (chain A), Y78 (chain D) and H75 (chain B) and two hydrogen bonds between A102 (chain D) and R73 (chain C). Additionally, in the structure of the M-MuLV IN NTR1-105, the 4 molecules that interact to form the butterfly shaped “dimer-of-dimers”, similar to that of the M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 structure, can be identified with molecules from the neighboring asymmetric unit. Fig. 3B highlights the overlap of the dimer identified for M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 with the M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 dimer-of-dimers. Superimposition of the corresponding “dimers” of the two structures has a Cα RMSD of 0.89 Å. Preparative gel filtration demonstrates that M-MuLV IN NTR1-10528,29 forms dimers in solution, with no identifiable tetramers. The shorter M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 construct also forms dimers with little evidence for oligomerization, based on analytical gel filtration with static light scattering detection (AGF-MALS)31 (Fig. S1). Therefore, the butterfly shaped tetramer of M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 appears to be stabilized by crystal packing interactions. In contrast, the two molecules in the asymmetric unit of the M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 structure do not have extensive intermolecular interactions. It is important to recognize that dimers (or ‘dimers of dimers’) observed in crystal lattice environments are not necessarily biologically relevant. Without further evidence, we cannot conclude that the dimers we observed in these crystal structures represent the dimer(s) that form in solution, or that these dimers are relevant to structures that are formed by full-length IN in its biological contexts. Moreover, mutating the interface residues in the crystal structure, K66 or R73, did not disrupt dimer formation in gel filtration experiments29.

Structural and functional comparison with PFV IN-NTD and HIV IN-NTDs

Fig. 4 shows the structural comparison of NTRs from M-MuLV and PFV, and NTDs from HIV-1, HIV-2 and MVV. HIV-1, HIV-2, and MVV INs lack the NED N-terminal extension subdomain that is present in the M-MuLV and PFV INs. In all five structures, the overall fold of the HHCC Zn-finger NTD domains, and positioning of the zinc ion are similar. HIV-1 and HIV-2 INs lack the C-terminal helix α5 in their isolated NTDs. The NTD structures vary primarily in the sizes of the surface loops. Within the NTD, the α2 region of PFV is shorter, providing a larger loop between α2 and α3. Similarly, the loops between α3 and α4 are quite distinct. All three viral NTDs that consist solely of the Zn-finger subdomain contain an extremely short loop consisting of 4 residues between the α3 and α4 helices (Fig. 2B). In contrast this region is greatly expanded in both virus INs encoding NED regions, with M-MuLV IN containing the largest loop, providing the additional β-strand that forms the β-sheet with the NED (Fig. 2B).

Figure 4. Structure comparison of M-MuLV IN-NTR with other virus IN NTRs and NTDs.

(A) Crystal structure of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 structure (PDB ID: 3NNQ). (B) Crystal structure of PFV IN NTR1-105 (PDB ID: 3L2Q). (C) Crystal structure of HIV-1 IN NTD (PDB ID: 1K6Y). (D) Crystal structure of HIV-2 IN NTD (PDB ID: 3F9K). (E) Crystal structure of MVV IN NTD (PDB ID: 3HPG). In the case of (C), (D) and (E), the NED region present in M-MuLV and PFV INs is absent from these INs. All panels show the HHCC motif as stick projections, coordinating a zinc ion that is shown is a brown dot. Panels A and B NTR’s consist of the NED (blue vertical bar) and NTD (green), while panels C, D and E consist of only the NTD (green vertical bars). In panels A and B the NED is comprised of the α1 helix and β1, β2 and β3 strands. In all five panels, the NTD is comprised of only α helices, except for M-MuLV, which has a β4 strand.

Although the PFV and M-MuLV NEDs are structurally similar to one another, and share an overall similar fold, overlay of the two proteins show differences in the relative orientation of the NED with respect to the NTD (Fig. 4A, B and Fig. S2, S3). Significantly, the formation of the extended β-sheet in M-MuLV IN defines the orientation of the NED with respect to the NTD.

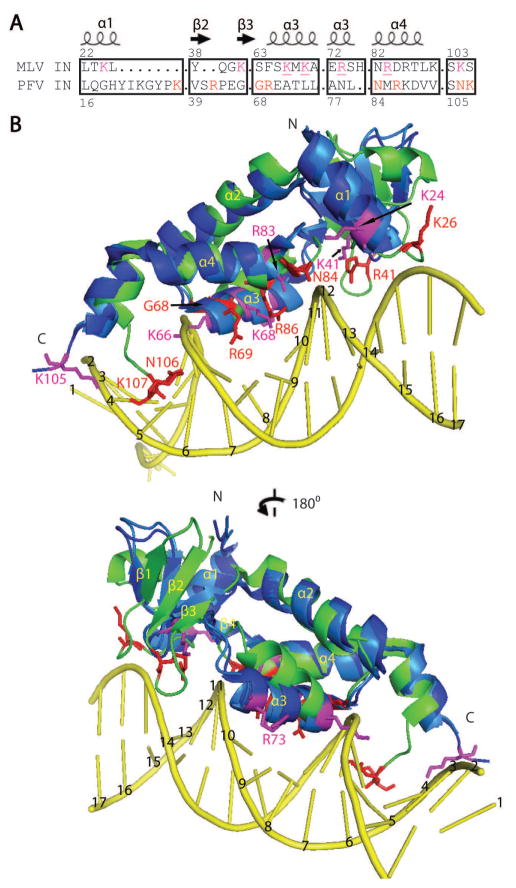

The PFV IN has been shown to interact with viral DNA using basic residues in two loop regions of the NED (i.e., residue K26 between α1 and β1, and residue R41 between β2 and β3)2. Sequence alignment (Fig. 2A) shows that both of these loop regions, including these basic residues (indicated by green dots on the PFV IN sequence) are deleted in the M-MuLV NED. This implies either that the M-MuLV NED does not form analogous close contact interactions with the viral LTR, or that the M-MuLV viral LTR forms an altered or bent structure, possibly associated with the highly conserved GGGG sequence at positions 10–13 nucleotides upstream of the viral termini that undergoes strand transfer43–45.

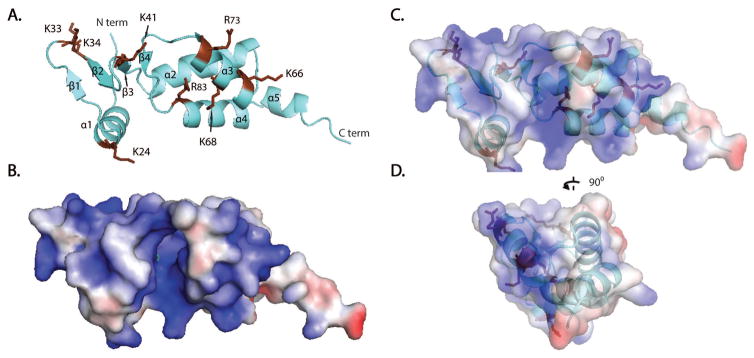

Additional positions within the NTR of PFV IN have been identified to be in contact with DNA. These include residues G68, R69, N84, R86, N106, and K1072. Of these positions, only residue N84 is conserved in M-MuLV IN. Previous mutational analysis of M-MuLV IN NTR of residues potentially involved in DNA interactions focused on basic residues conserved in related gammaretroviruses including MCF, Friend MLV, AKV, FeLV and RaLV29. From these studies, mutations within the NED including K24A, K33A/K34A, and K41A did not alter in vitro integration activities, whereas mutation within the NTD including K66A/K68A and R73A dramatically decreased both viral titer and in vitro 3′ cleavage and strand transfer. The R83A mutant complements CCD/CTD constructs for strand transfer but not for 3′ processing29. These basic residues are highlighted in red in Fig. 5A. The surface electrostatic potential distribution on the surface of the M-MuLV NTR (Fig. 5B) further suggests that these basic residues within the NTR form a DNA-binding cluster on one face of the domain (Fig. 5C, D). A sequence alignment of critical regions of M-MuLV and PFV IN (Fig. 6A) shows key basic residues of M-MuLV IN (marked in magenta and underlined), which when mutated affect strand transfer in vitro29, along with analogous residues of PFV IN (marked in red) that interact with the LTR in the crystal structure of the PFV IN – LTR complex2. These key residues of M-MuLV and PFV INs are in similar positions in superimposed structures of the corresponding NTRs.

Figure 5. Surface electrostatic potential of M-MuLV IN NTR.

(A) Ribbon representation of M-MuLV NTR1-105 in aquamarine with basic residues and their side chains marked in brown. N- and C-termini are indicated with “N” and “C”, respectively. (B) Surface electrostatic potential of M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 with red and blue colors indicating surface electrostatic potentials at +/− 2 kT, at an ionic strength of 0.15 M and 298 K. (C) Transparent representation of panel B with the ribbon representation within. (D) View of the image in panel C rotated by 90°, showing basic residues (highlighted in brown) predicted to interact with DNA, largely clustering on one face. Images were generated using PyMol48.

Figure 6. Overlay of M-MuLV and PFV IN NTRs.

(A) Sequence alignment adapted from Fig. 2 indicating key residues and secondary structural features of M-MuLV and PFV IN NTRs. Sequences between the boxed regions are not shown. Key M-MuLV residues are marked in magenta and those of PFV are marked in red. Residues that are important for in vitro integration activity for M-MuLV are underlined. (B) Model of M-MuLV NTR – LTR complex based on the X-ray crystal structure of the homologous PFV NTR – LTR complex2. PFV IN NTR (green) with DNA-binding residues represented with red sticks. Key residues predicted to be important in DNA binding for the M-MuLV IN NTR are represented with magenta sticks. Both crystal forms of M-MuLV IN NTR are depicted in the figure as blue (M-MuLV IN8-105) and light blue (M-MuLV IN1-105) and overlaid with PFV IN NTR. For ease of representation only the side chains of M-MuLV IN8-105 are displayed in magenta. The top and bottom images of panel B differ by a 180° rotation. N- and C-termini are indicated with “N” and “C”, respectively. In both panels, the transferred strand during integration is numbered in the 3′-5′ direction; the CA dinucleotide occupies positions 2 and 1, respectively.

These conserved basic residues of the M-MuLV NTR also form contacts with DNA in a simple homology model of the M-MuLV IN-LTR DNA complex (Fig. 6B), which was constructed based on the crystal structure of the PFV IN-LTR DNA complex2. Significantly, the positioning of M-MuLV IN residues K66/K68 in this simple model places them in close proximity with the viral LTR, particularly residue K68 which interacts at sequence positions 9–10 bases from the termini of the LTR that undergoes strand transfer. In this model, the sequences within the NED are held in position by the novel β-sheet formed between NED and NTD, which results in a relatively constrained conformation when compared with the PFV NTR. Disruption of this β-sheet would allow conformational flexibility in the relative orientation of the NED and NTD, potentially enabling optimal interaction with the viral DNA. Mutational analysis has indicated that the basic residues within the NED are not essential for virus viability ( reference 29 and data not shown). Within the PFV NTR, the NED does not provide base-specific contacts with the viral LTR but rather only enables stabilization of the interaction through contacts with the phosphodiester backbone2. Consequently, this model does not rule out an additional role for the NED in interacting with host proteins.

The role of the NED of the NTR of M-MuLV and PFV INs has been postulated to improve stabilization of the viral LTR:IN interaction2. For HIV-1 IN, enhanced activity and solubility was observed when fused with the non-specific DNA binding domain (Sso7d) as a surrogate for NED46. However, this enhanced activity was not affected by substituting amino acids in Sso7d that contribute to non-specific DNA binding. This suggests that the Sso7d fusion is blocking formation of a non-productive complex, rather than directly aiding in the engagement of viral LTR. Interestingly, the fusion of the PFV NED to the HIV IN NTD does not yield a highly active protein46.

Our analysis of these X-ray crystal structures together with published mutagenesis and virology studies28,29 suggest that specific structural features of the M-MuLV IN NED can provide additional stabilizing contacts in IN-LTR complex; at least some key determinants for conferring LTR specificity must reside in the NED. Moreover, the NEDs appear to have evolved to specifically function only in the context of their respective retroviral INs.

Data deposition

Coordinates and structure factors for these M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 and IN NTR8-105 X-ray crystal structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID: 3NNQ and 4NZG respectively). Note that the residue numbering in these PDB entries is shifted by +1 residue relative to the literature numbering used in this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Hauptman-Woodward Research Institute high-throughput crystallization screening facility for initial crystallization screening. X-ray diffraction data for M-MuLV IN NTR1-105 were measured on beamline X4A of the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS). We thank John Schwanof and Randy Abramowitz for their help in data collection. X-ray diffraction data for M-MuLV IN NTR8-105 were measured on NSLS beamline X29A where the financial support comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health, and we thank Dr Howard Robinson for his help with data collection. G.T. Montelione and R. Xiao are associated with Nexomics Biosciences, Inc., a structural biology consulting company. Since completing this work, T. Acton has moved to Evotech, Inc. This work was supported as a Community Outreach activity of the NIGMS Protein Structure Initiative grant U54 GM094597 (GTM) and by grants R01GM070837 and RO1GM110639 (MR).

References

- 1.Craigie R, Bushman FD. HIV DNA Integration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(7):a006890. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature. 2010;464(7286):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hare S, Maertens GN, Cherepanov P. 3′-processing and strand transfer catalysed by retroviral integrase in crystallo. EMBO J. 2012;31(13):3020–3028. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maertens GN, Hare S, Cherepanov P. The mechanism of retroviral integration from X-ray structures of its key intermediates. Nature. 2010;468:326–329. doi: 10.1038/nature09517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maskell DP, Renault L, Serrao E, Lesbats P, Matadeen R, Hare S, Lindemann D, Engelman AN, Costa A, Cherepanov P. Structural basis for retroviral integration into nucleosomes. Nature. 2015;523(7560):366–369. doi: 10.1038/nature14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin Z, Shi K, Banerjee S, Pandey KK, Bera S, Grandgenett DP, Aihara H. Crystal structure of the Rous sarcoma virus intasome. Nature. 2016;530(7590):362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature16950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballandras-Colas A, Brown M, Cook NJ, Dewdney TG, Demeler B, Cherepanov P, Lyumkis D, Engelman AN. Cryo-EM reveals a novel octameric integrase structure for betaretroviral intasome function. Nature. 2016;530(7590):358–361. doi: 10.1038/nature16955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiyer S, Rossi P, Malani N, Schneider WM, Chandar A, Bushman FD, Montelione GT, Roth MJ. Structural and sequencing analysis of local target DNA recognition by MLV integrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(11):5647–5663. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak MG, Sudol M, Lee NE, Jr, WMK, Katzman M. Identifying amino acid residues that contribute to the cellular-DNA binding site on retroviral integrase. Virology. 2009;389:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serrao E, Ballandras-Colas A, Cherepanov P, Maertens GN, Engelman AN. Key determinants of target DNA recognition by retroviral intasomes. Retrovirology. 2015;12(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson MS, McClure MA, Feng DF, Gray J, Doolittle RF. Computer analysis of retroviral pol genes: Assignment of enzymatic functions to specific sequences and homologies with nonviral enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7648–7652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eijkelenboom APAA, Ent FMIvd, Vos A, Doreleijers JF, Hard K, Tullius TD, Plasterk RHA, Kaptein R, Boelens R. The solution structure of the amino-terminal HHCC domain of HIV-2 integrase: a three-helix bundle stabilized by zinc. Current Biology. 1997;7(10):739–746. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J-Y, Ling H, Yang W, Craigie R. Structure of a two-domain fragment of HIV-1 integrase: implications for domain organization in the intact protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:7333–7343. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bojja RS, Andrake MD, Merkel G, Weigand S, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Skalka AM. Architecture and assembly of HIV integrase multimers in the absence of DNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(10):7373–7386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonsson CB, Donzella GA, Gaucan E, Smith CM, Roth MJ. Functional domains of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase defined by mutation and complementation analysis. J Virol. 1996;70(7):4585–4597. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4585-4597.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson CB, Roth MJ. Role of the His-Cys finger of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase protein in integration and disintegration. J Virol. 1993;67(9):5562–5571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5562-5571.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menendez-Arias L, Gotte D, Oroszlan S. Moloney murine leukemia virus protease: bacterial expression and characterization of the purified enzyme. Virology. 1993;196(2):557–563. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fassati A, Goff SP. Characterization of intracellular reverse transcription complexes of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1999;73(11):8919–8925. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.8919-8925.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowerman B, Brown PO, Bishop JM, Varmus HE. A nucleoprotein complex mediates the integration of retroviral DNA. Genes & Development. 1989;3:469–478. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MS, Craigie R. A previously unidentified host protein protects retroviral DNA from autointegration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prizan-Ravid A, Elis E, Laham-Karam N, Selig S, Ehrlich M, Bacharach E. The Gag cleavage product, p12, is a functional constituent of the murine leukemia virus pre-integration complex. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(11):e1001183. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki Y, Craigie R. Regulatory mechanisms by which barrier-to-autointegration factor blocks autointegration and stimulates intermolecular integration of Moloney murine leukemia virus preintegration complexes. J Virol. 2002;76:12376–12380. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12376-12380.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Rijck J, de Kogel C, Demeulemeester J, Vets S, El Ashkar S, Malani N, Bushman FD, Landuyt B, Husson SJ, Busschots K, Gijsbers R, Debyser Z. The BET family of proteins targets Moloney murine leukemia virus integration near transcription start sites. Cell Rep. 2013;5(4):886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aiyer S, Swapna GVT, Malani N, Aramini JM, Schneider WM, Plumb MR, Ghanem M, Larue RC, Sharma A, Studamire B, Kvaratskhelia M, Bushman FD, Montelione GT, Roth MJ. Altering murine leukemia virus integration through disruption of the integrase and BET protein family interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):5917–5928. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta SS, Maetzig T, Maertens GN, Sharif A, Rothe M, Weidner-Glunde M, Galla M, Schambach A, Cherepanov P, Schulz TF. Bromo and ET domain (BET) chromatin regulators serve as co-factors for murine leukemia virus integration. J Virol. 2013;87(23):12721–12736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01942-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma A, Larue RC, Plumb MR, Malani N, Male F, Slaughter A, Kessl JJ, Shkriabai N, Coward E, Aiyer SS, Green PL, Wu L, Roth MJ, Bushman FD, Kvaratskhelia M. BET proteins promote efficient murine leukemia virus integration at transcription start sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(29):12036–12041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307157110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai M, Zheng R, Caffrey M, Craigie R, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Solution structure of the N-terminal zinc binding domain of HIV-1 integrase. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(7):567–577. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang F, Leon O, Greenfield NJ, Roth MJ. Functional interactions of the HHCC domain of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase revealed by non-overlapping complementation and zinc dependent dimerization. J Virol. 1999;73:1809–1817. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1809-1817.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang F, Seamon JA, Roth MJ. Mutational analysis of the N-terminus of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase. Virology. 2001;291:32–45. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acton TB, Xiao R, Anderson S, Aramini J, Buchwald WA, Ciccosanti C, Conover K, Everett J, Hamilton K, Huang YJ, Janjua H, Kornhaber G, Lau J, Lee DY, Liu G, Maglaqui M, Ma L, Mao L, Patel D, Rossi P, Sahdev S, Shastry R, Swapna GV, Tang Y, Tong S, Wang D, Wang H, Zhao L, Montelione GT. Preparation of protein samples for NMR structure, function, and small-molecule screening studies. Methods Enzymol. 2011;493:21–60. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00002-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao R, Anderson S, Aramini J, Belote R, Buchwald WA, Ciccosanti C, Conover K, Everett JK, Hamilton K, Huang YJ, Janjua H, Jiang M, Kornhaber GJ, Lee DY, Locke JY, Ma LC, Maglaqui M, Mao L, Mitra S, Patel D, Rossi P, Sahdev S, Sharma S, Shastry R, Swapna GV, Tong SN, Wang D, Wang H, Zhao L, Montelione GT, Acton TB. The high-throughput protein sample production platform of the Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium. J Struct Biol. 2010;172(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luft JR, Collins RJ, Fehrman NA, Lauricella AM, Veatch CK, DeTitta GT. A deliberate approach to screening for initial crystallization conditions of biological macromolecules. J Struct Biol. 2003;142(1):170–179. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. Vol. 276. Academic Press; 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode; pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson H, Soares AS, Becker M, Sweet R, Heroux A. Mail-in crystallography program at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s National Synchrotron Light Source. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 11):1336–1339. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906026321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55(Pt 4):849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56(Pt 8):965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, 3rd, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins. 2003;50(3):437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joosten RP, Joosten K, Murshudov GN, Perrakis A. PDB_REDO: constructive validation, more than just looking for errors. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:484–496. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911054515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donzella GA, Jonsson CB, Roth MJ. Influence of substrate structure on disintegration activity of Moloney murine leukemia virus integrase. J Virol. 1993;67(12):7077–7087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7077-7087.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Neill RR, Buckler CE, Theodore TS, Martin MA, Repaske R. Envelope and long terminal repeat sequences of a cloned infectious NZB xenotropic murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1985;53(1):100–106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.1.100-106.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Golemis EA, Speck NA, Hopkins N. Alignment of U3 region sequences of mammalian type C viruses: identification of highly conserved motifs and implications for enhancer design. J Virol. 1990;64(2):534–542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.534-542.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M, Jurado KA, Lin S, Engelman A, Craigie R. Engineered hyperactive integrase for concerted HIV-1 DNA integration. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15(4):305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schrodinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W545–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.