Abstract

Sexual positioning practices among men who have sex with men (MSM) have not received a thorough discussion in the MSM and HIV literature, given that risks for acquiring or transmitting HIV and STIs via condomless anal sex vary according to sexual positioning. MSM bear a disproportionate burden of HIV compared to the general population in the United States; surveillance efforts suggest that HIV and STIs are increasing among domestic and international populations of MSM. We conducted a narrative review, using a targeted literature search strategy, as an initial effort to explore processes through which sexual positioning practices may contribute to HIV/STI transmission. Peer-reviewed articles were eligible for inclusion if they contained a measure of sexual positioning identity and/or behavior (i.e. “top,” “bottom,” etc.) or sexual positioning behavior (receptive anal intercourse [RAI] or insertive anal intercourse [IAI]), or assessed the relationship between sexual positioning identity with HIV risk, anal sex practice, masculinity, power, partner type, or HIV status. A total of 23 articles met our inclusion criteria. This review highlights dynamic psycho-social processes likely underlying sexual decision-making related to sexual positioning identity and practices among MSM and MSM who have sex with women (MSMW), and ways these contexts may influence HIV/STI risk. Despite limited focus in the extant literature, this review notes the important role contextual factors (masculinity stereotypes, power, partner type, and HIV status) likely play in influencing sexual positioning identity and practices. Through this review we offer an initial synthesis of the literature describing sexual positioning identities and practices and conceptual model to provide insight into important areas of study through future research.

Keywords: MSM, sexual positioning, insertive anal sex, receptive anal sex, HIV, culture

Introduction

Sexual positioning practices among men who have sex with men (MSM) have not received a thorough discussion in the MSM and HIV literature. Risks for acquiring or transmitting HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) via condomless anal sex vary according to sexual positioning. Specifically, men who participate in receptive anal intercourse (RAI) are more likely to acquire HIV and rectal STIs compared to men who only participate in insertive anal intercourse (IAI) (Coates et al., 1988; Kent et al., 2005). A greater understanding of the dynamics underlying sexual positioning practices and the ways these dynamics may contribute to HIV and other STIs is needed (Baggaley, White, & Boily, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2014a, 2014b).

MSM bear a disproportionate burden of HIV and STIs compared to the general population in the United States (CDC, 2010; Scott et al., 2014), for whom rates of HIV and STIs continue to increase among domestic and international MSM populations (Beyrer et al., 2012; CDC, 2010; Prejean et al., 2011; van Griensven, de Lind van Wijngaarden, Baral, & Grulich, 2009). In 2013, gay and bisexual men in the United States accounted for 81% of estimated HIV diagnoses among all males aged 13 years and older and 65% of the estimated diagnoses among all HIV diagnoses that year (CDC 2015). Similarly, gonorrhea cases among MSM increased 14% compared to the cases among men who have sex with women only that remained stable and the proportion of cases among women that declined 13% (Kidd, Stenger, Kirkcaldy, Llata, & Weinstock, 2015). Data further show that STIs potentiate HIV acquisition and transmission (Dallabetta & Neilsen, 2005; Frye et al., 2009; Malott et al., 2013). Both RAI and IAI, as sexual positioning practices, can facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission among MSM. Specifically, condomless RAI may allow HIV greater access to the blood stream during sex due to the thin lining in the rectum and increased risk of tearing, while condomless IAI may allow HIV to enter through the opening of the penis (CDC, 2014, 2014; Edwards & Carne, 1998; Vitinghoff et al., 1999). With regard to facilitating HIV infection, ulcerative STIs (e.g. syphilis and herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2)) result in lesions that ultimately increase the number of inflammatory immune cells in the affected areas (genital tract or rectum) which serves as an entry point for HIV to infect and replicate. Similarly, inflammatory STIs (e.g. gonorrhea and chlamydia) also result in the inflammation of immune cells and facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission (Fleming & Wasserheit, 1999; Mayer & Venkatesh, 2011; Rottingen, William, & Garnett, 2001). MSM who practice both insertive and receptive roles for anal sex may be at high risk for HIV infection via RAI and may also potentiate subsequent HIV infection to others through IAI (Beyrer et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2011; Wolitski & Branson, 2002). Versatility (practicing both IAI and RAI) for anal sexual positioning thus increases the chance of infection and transmission to others in this group (van Druten, van Griensven, & Hendriks, 1992; Wiley & Herschkorn, 1989). The varying degrees of RAI, IAI, and versatility among MSM may create different risk profiles within MSM as a broader target population. Traditionally, the term MSM has included both homosexually and bisexually active men whether or not they identify as gay or bisexual. However, it may be more advantageous to consider how behavioral risk profiles between men who only have sex with men (MSM) might differ from men who have sex with men and women (MSMW), as recent studies have shown sociodemographic and behavioral differences between these two groups. Specifically, MSMW report higher prevalence of substance use, exchanging sex for money or drugs, and greater number of sexual partners, and lower proportion of condomless RAI, which create different profiles of sexual risk for both groups of men (Millett et al., 2012; Millett, Flores, Peterson, & Bakeman, 2007; Wheeler, Lauby, Liu, Sluytman, & Murrill, 2008).

Efforts to reduce incident HIV and STI infections among MSM and MSMW will have important individual and community-level health benefits, reducing opportunities for future HIV/STI transmission (Crandall & Coleman, 1992; Frye et al., 2009; Wolitski & Branson, 2002). Articulating how sexual positioning identities (“top”, “bottom,” “versatile,” etc.) and behaviors (RAI, IAI) among MSM and MSMW manifest to increase or reduce vulnerability to HIV and STIs may provide additional insights into modifiable risk factors and contexts. Different contextual factors may also affect the ability to negotiate HIV prevention practices and condom use. Such information could inform ways current and future prevention efforts might leverage sexual positioning dynamics among MSM and MSMW.

Correlates that may influence sexual positioning and sexual decision-making among MSM and/or MSMW have not been comprehensively assessed. Gender and power have been theoretically linked to the sexual transmission of HIV among both heterosexual and same-sex couples (Johns, Pingel, Eisenberg, Santana, & Bauermeister, 2012). In heterosexual transmission, power imbalances in sexual negotiation derived from gender roles are implicated in women’s increased vulnerability to HIV (Johns et al., 2012; MacPhail, Williams, & Campbell, 2002; Rosenthal & Levy, 2010). These forces have also been highlighted in same-sex sexual relationships. MSM characterized insertive and receptive partners (or “tops” and “bottoms”) with descriptions rooted in assumptions about sexual positioning and gender roles, but these assumptions did not always contribute to the distribution of power during sexual negotiations as in heterosexual sexual relationships. To date, the relationship between perceptions of masculinity, power, partner type, and HIV status has not been adequately summarized in the context of sexual positioning and versatility among the general population of MSM.

The purpose of this narrative review is to describe the existing literature on sexual positioning identities and practices among the general population of MSM in order to highlight its current and future contributions for HIV prevention research. With the aim of evaluating the extant work in this area for theoretical development and contributions, we adopt a narrative-style review as an alternative to a meta-analytic review, which is more appropriate for evaluating the magnitude and consistency of given a set of relationships (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, 2013). This review will begin by highlighting ways in which anal sexual positioning preferences and practices among MSM have been measured in the extant literature (i.e. self-labeling identities and behaviors). We will then review how selected factors affect sexual positioning practices (including masculinity stereotypes, power dynamics, partner type, and HIV status) that we hypothesize to be associated contexts under which sexual positioning practices increase vulnerability to HIV. We then provide discussion on how this literature could help inform new intervention strategies sensitive to sexual positioning contexts, targeting decision-making to practice RAI or IAI and sexual risk taking among MSM and MSMW. However, due to limited data making behavioral distinctions between MSM and MSMW, for the purposes of this review, we will consider MSM broadly and highlight behavioral characteristics among MSMW where available. In support of future work, we conclude with a more thorough consideration for bisexually-identified and bisexually active MSMW in the MSMW literature. Through this synthesis and critique of sexual decision-making and risk taking among MSM, we aim to add insight to the extant literature that will be important for enhancing current theoretical perspectives on same-sex, male centered sexual behaviors and sexual dynamics. We also offer contextual insights into gay culture and sexual practices among MSM for the social sciences, critical to future research and intervention development.

Literature Search Methods

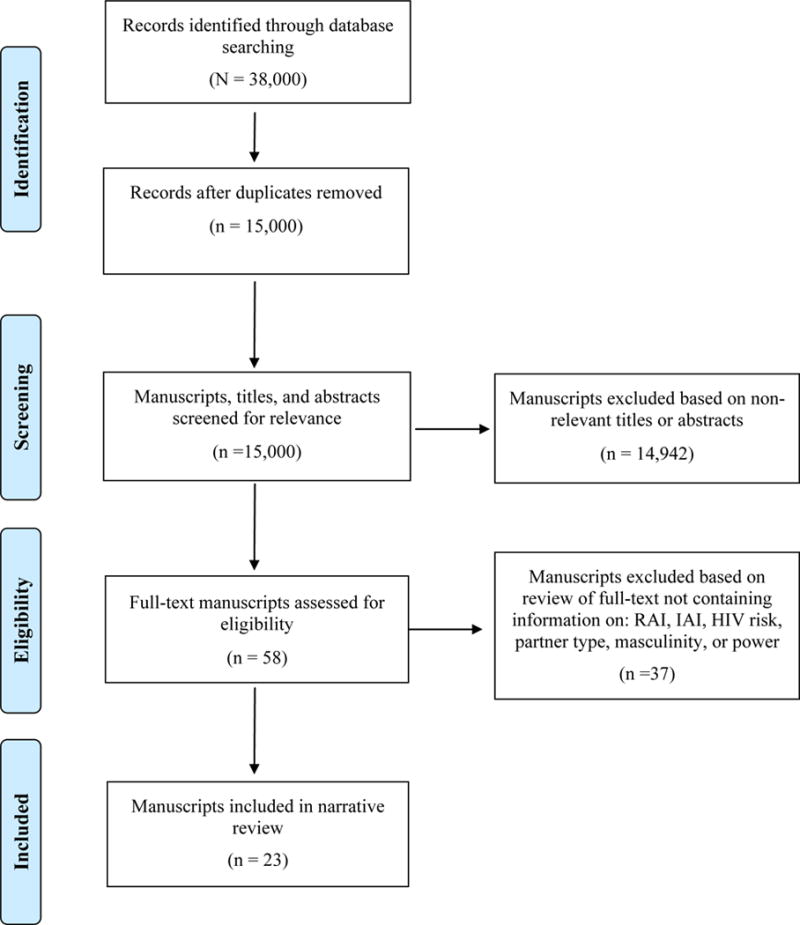

This narrative review utilized a targeted literature search strategy. In order to gather a range of relevant epidemiological, public health, and social science literature, we searched two online databases: PubMed and Google Scholar. The literature search was conducted in two phases between October and December 2014. First, we selected peer-reviewed articles directly related to sexual positioning among MSM, using search terms such as “MSM,” sexual positioning,” “top,” and “bottom” in both search engines. Second, we conducted a separate search for “receptive anal intercourse among MSM” and “insertive anal intercourse among MSM.” Combined, these searches resulted in about 38,000 abstracts which were unduplicated and reviewed for inclusion. Articles were included if they contained a measure of sexual positioning identity and/or behavior (i.e. “top,” “bottom,” etc.) or sexual positioning behavior (RAI or IAI), or assessed the relationship between sexual positioning identity with at least one of the following: HIV risk, condom use, gender roles, anal sex practice, masculinity, power, partner type, or HIV status. To be included in this review, the study needed to be conducted in the United States, Western Europe, Canada, or Australia to limit potential cultural differences between MSM populations (not ignoring possible cultural differences between racial/ethnic groups of MSM in the United States and other regions). Data from studies that included multiple countries were disaggregated and data from nations that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Dissertations, books, editorials, letters and commentaries were also excluded from this narrative review.

Based upon an initial review of the location, title, and abstract, 58 articles were assessed for inclusion, 23 of which were included in this review. There were 36 articles that were excluded because data did not provide insight about sexual positioning identity or practice, HIV risk, masculinity, power, partner type, or HIV status (Figure 1). Data from the 23 articles included in this review were organized into a summary table describing the studies, measurement of sexual positioning identity and practice, and major findings (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Literature Search Strategy

Table 1.

Description of studies meeting review criteria

| Study Descriptives | Measure of Sexual Positioning Identity (I) or Behavior (B) | Major Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Argonick et al. 2003 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross-sectional quantitative survey |

N: 441 Latino Men SO: Bisexual- or Gay-identified Age: 15–25 |

I: Not reported B: Total RAI, IAI, URAI, UIAI |

1. Bisexually-identified men were less likely to report RAI compared to gay-identified men (29% vs. 58%; OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.15, 0.60) 2. Bisexually-identified men were more likely to report condomless IAI during last encounter with a non-main male partner compared to gay-identified men (OR 3.45,95% CI 1.03, 11.53) |

| 2. Bauermeister et al. 2009 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross-sectional in-depth qualitative interview |

N: 120 men SO: MSM Age: ≥ 18 |

I: Not reported B: URAI |

1. HIV-positive men reported having greater number of URAI occasions, and more partners with whom they had URAI 2. HIV-positive participants, we found a positive association between the number of URAI occasions and greater benefits/gains to bareback sex in the overall score among HIV positive men (r= .38; p< .05) |

| 3. Carballo-Dieguez et al. 2004 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross-sectional quantitative survey, focus group |

N: 294 Latino men SO: Bisexual- or Gay- identified Age: 18–67 |

I: Activo & pasivo B: ‘If compared to you, your partner is taller, when it comes to oral sex, are you more likely to suck him or be sucked by him? When it comes to anal sex, are you more likely to fuck him or be fucked by him?’ A total of 22 such questions, grouped in 11 pairs of antonyms (e.g., tall/short, more macho/more effeminate) were asked. |

1. When partner is perceived to be more “macho” or aggressive taller, or have a bigger penis, darker, or more handsome, respondents report they are more likely to take the receptive role for oral and anal sex (McNemar’s p<.001) 2. Versatile individuals likely to take “passive” role when judge sexual partner appears more masculine. 3. Gender stereotypes of masculinity and femininity play an important role in the sexual behaviors of Latino gay and bisexual men. Stigma and guilt may be the cost of taking the “passive” role” |

| 4. Carrier 1977 Location: USA, Greece Design: Comparative study |

N: 5 countries SO: Homosexual Age: ≥ 18 |

I: Active & passive B: Insertor Insertee |

1. Males in Greece have rigidly defined insertor-insertee roles, and life events may be predictive of sexual role preferences 2. Among middle-class white American males, few or no sex-role feelings are associated with types of sex acts among homosexually active males |

| 5. Grov, Parson & Bimbi 2008 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey |

N: 1065 SO: Bisexual- and Gay identified Age: ≥ 18 |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile, Refused B: Not reported |

1. 33.2% identified as “Top” 37.3% identified as “versatile” 25.4% identified as “bottom” and 4.1% “refused.” 2. 7.1% perceived penis size was “below average” 56.0% perceived penis to be average” 36.9% perceived penis was above or way above average |

| 6. Hart et al. 2003 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey |

N: 205 SO: MSM Age: mean=37.7 |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile, These Labels Don’t Apply B: RAI, IAI |

1. 18% identified as “top,” 23% identified as “bottom,” 47% identified as “versatile,” 12% “Did not apply” 2. Tops and versatiles had higher proportion of IAI among all anal intercourse compared to “bottoms” (.86 and .53 versus .11, respectively) 3. Bottoms had higher proportion of RAI compared to tops and versatiles (100% compared to 41.4% and 79.5%, respectively) |

| 7. Hoppe 2011 Location: San Francisco, USA Design: In-depth qualitative interviews, focus groups |

N: 18 SO: Gay Age: 27–66 |

I: Bottom B: RAI |

1. Performance as a bottom is means of getting pleasure by giving pleasure 2. Men’s conceptions of their relations to power as bottoms was constituted through their relations to pleasure |

| 8. Husbands et al. 2013 Location: Toronto, Canada Design: Cross-sectional quantitative survey, in-depth qualitative interviews |

N=168 SO: Gay, bisexual, other Age: 18+ |

I: N/A B: IAI, RAI, Versatile |

1. Black men 2.4 times more likely to be the insertive partner with white men than Black men, 2.6 times more likely to be insertive with men from other ethnicities than Black men 2. 33% of Black men who reported adopting insertive roles with white men |

| 9. Jacobs et al. 2010 Location: South Florida; USA Design: Cross sectional survey |

N: 802 SO: MSM Age: 40–94 |

I: Not reported B: URAI, UIAI |

1. Mid-life men had higher proportion of reporting URAI compared to later-life men (37.8% versus 22.1%, respectively) 2. Mid-life men had higher proportion of UIAI with partners of unknown status compared to later life men (20.3% versus 11.9% respectively) |

| 10. Jeffries IV 2009 Location: USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey |

N: 4928 SO: MSM Age: 15–44 |

I: Not reported B: IAI, IAI only, RAI, RAI only. “Have you ever done any of the following with another male: (1) Put his penis in your mouth? (2) Put your penis in his mouth? (3) Put his penis in your rectum or butt? (4) Put your penis in his rectum or butt?” Measure of IAI, IAI only, RAI, RAI only. Same for oral sex |

1. Non-Mexican Latino MSM had greater preference for IAI compared to Mexican MSM (18.3% vs 3.3%) 2. Mexican MSM had a greater proportion of RAI compared to white MSM (13.3% vs. 4.6%) |

| 11. Johns et al. 2012 Location: Detroit, USA Design: In-depth qualitative interviews |

N: 34 SO: Gay Age: 18–24 |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile, Unspecified B: Not reported |

1. Within the context of a hookup, or casual sexual encounter, gender roles aided in sexual positioning decision-making 2. Within a romantic, long-term relationship, gender roles were not inherent to the negotiation of anal sex behaviors |

| 12. Kippax & Smith 2001 Location: Australia Design: In-depth qualitative interviews |

N: 51 SO: Gay Age: 20–51 |

I: Not reported B: IAI, RAI |

1. Some MSM praise the versatility to re-distribute power during sex during IAI or RAI 2. MSM may not necessarily maintain a one-directional relationship of giving and receiving power |

| 13. Klein 2009 Location: USA Design: Content analysis |

N: 1434 SO: Gay, Bisexual, Hetero/curious Age:18–64 |

I: Top, Versatile Top, Versatile, Versatile Bottom, Bottom B: IAI, RAI |

1. 35.4% of MSM self-identified as being “top” or “versatile top” 2. 22.4% of MSM self-identified as “versatile” 3. 42.3% of MSM self-identified as “bottom” or “versatile bottom” |

| 14. Lyons et al. 2011 Location: Australia Design: Cross-sectional quantitative survey |

N: 856 SO: Homosexual, gay Age: 16–76 |

I: Not reported B: IAI, RAI |

1. 83% of men in sample were versatile (practiced both IAI and RAI) in past 12 months 2. Men who were versatile were most likely to be aged 50 and over, in regular relationship, and of unknown HIV status. |

| 15. Lyons et al. 2012 Location: Australia Design: Cross-sectional quantitative survey |

N: 693 SO: Homosexual, gay Age: 40–81 |

I: Not reported B: IAI, RAI |

1. Men more likely to be versatile if younger, had higher income, or reported greater number of sexual partners (p=.05) 2. 20% of men in sample were highly versatile |

| 16. Moskowitz, Rieger, & Roloff 2008 Location: USA, Australia, Europe Design: Content analysis of personal ads found online |

N: 150 SO: Gay Age: 20–58 |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile B: IAI, RAI, fellatio, urination, fisting, foot play, armpit play, sex-toy play, defecation, verbal abuse, role-playing, and domination |

1. (92.6%) and versatiles (92.6%) reported willingness towards IAI, while only a minority of bottoms (20%) reported the same willingness, χ2(2, n = 145) = 78.84, Φ 2 = .55, p < .001 2. Tops had a significantly higher preference for being insertive over receptive, (M diff = 2.22, SD = 2.59), t(26) = 4.46, p < .001, d = .86. Bottoms showed a significantly higher preference for being receptive over insertive, (M diff = −3.00, SD = 2.92), t(49) = −7.26, p < .001, d = −1.03. And, as predicted for the versatile group, there was no statistically significant mean difference between being insertive versus receptive (M diff = .07, SD = 1.47), t(67) = .41, p = .68, d = .05 |

| 17. Moskowitz & Hart 2011 Location: USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey |

N: 429 SO: Gay and Bisexual Age: 18–79 |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile, Don’t have anal sex B: Top, Bottom, Versatile |

1. Tops were more likely to have larger erect penises (OR=2.05, 95% CI=1.42–2.98, p,.01) and more masculine (OR 1.30, 95% CI=1.11–1.51) than bottoms 2. Versatiles were more likely to have larger erect penises (OR=1.69 95% CI 1.20–2.40, p<.01) and more likely to be masculine than bottoms (OR=1.17, p=.05) |

| 18. Pachankis et al. 2013 Location: USA Design: Longitudinal survey, qualitative interviews |

N: 93 SO: Gay, Heterosexual, Bisexual but mostly gay, Bisexual, Bisexual but mostly Heterosexual, Queer, Uncertain Age: mean=20.61 |

I: Exclusively top, mostly top, versatile, mostly bottom, exclusively bottom, never labeled in this way, used these labels in the past but not anymore B: RAI, IAI |

1. 51.6% changed sexual positioning identity 2. Participants more likely to change into “mostly top” at Time 2 than any other position identity (x2 = 8.99, p<.01) 3. 82.1% of people who noted personal reasons personal growth (53.6% of whom noted increased self-awareness) as reasons for identity change 4. Four major reasons for changes in identity: Personal reasons, practical reasons, relationship reasons, and sociocultural reasons |

| 19. Parsons et al. 2003 Location: New York & San Francisco, USA Design: Cross sectional survey, qualitative interviews |

N: 456 SO: Gay, Bisexual, Heterosexual, Unsure Age: ≥ 18 |

I: Not reported B: UAI, UAR |

1. HIV MSM who reported UIAI perceived less responsibility to protect their partners from HIV 2. Men reporting URAI reported greater depression than those not reporting unprotected anal sex and greater and loneliness than those reporting UIAI |

| 20. Tskhay, Re, & Rule 2014 Location: USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey |

N: 121 SO: Gay, bisexual Age: mean=28.62 |

I: Top, Bottom B: Always top, sometimes top, versatile, sometimes bottom, always bottom |

1. Participants categorized approximately 80 % of tops and bottoms to their respective categories by facial cues |

| 21. Van De Ven et al. 2002 Location: Sydney, Australia Design: Cross sectional survey |

N: 14,165 SO: Gay Age: 14–81 |

I: N/A B: IAI, RAI, URAI, UIAI |

1. HIV positive MSM had higher proportion of RAI only compared to HIV negative MSM (69.0% and 9.3%, respectively) 2. HIV negative MSM had higher proportion of IAI only compared to HIV positive MSM (69.3% and 9.9%, respectively) |

| 22. Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg 2000 Location: New York, USA Design: Cross sectional quantitative survey, in-depth qualitative interviews |

N: 84 SO: Gay, Bisexual Age: 18–60 |

I: Top, Bottom, Other, N/A B: IAI, RAI |

1. 29.7% labeled themselves “top” and 28.6% labeled themselves bottoms at baseline 2. HIV positive status associated with MSM identifying as Bottom (p<.05) |

| 23. Wei & Raymond 2011 Location: San Francisco, USA Design: Cross sectional survey |

N: 386 SO: N/A Age: 18+ |

I: Top, Bottom, Versatile B: RAI, IAI |

1. 21% identified as bottom, 42% identified as top, 37% identified as bottom 2. Among all racial/ethnic groups, men did not maintain preferences 100% of the time, and no group maintained their preference at greater or lesser level than any other group |

SO = Sexual Orientation, RAI = Receptive Anal Intercourse, IAI = Insertive Anal Intercourse, URAI = Unprotected (condomless) Receptive Anal Intercourse, UAIA = Unprotected (condomless) Insertive Anal Intercourse

Review

Definition and Assessment of Sexual Positioning Identity and Practice

Eleven (47.8%) articles included in this review provided a definition and/or assessment of both sexual positioning identity and practice. In Western populations, men who prefer IAI have generally been referred to as “tops,” men who prefer RAI have been referred to as “bottoms,” and men who prefer both have been referred to as “versatile” or “vers” (Carrier, 1977; Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gómez, Halkitis, et al., 2003; van Druten et al., 1992; Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). Recently, new labels for sexual positioning preferences are being formed among MSM, including “versatile bottom” and “versatile top,” where identifying as a “versatile bottom” refers to someone who “mostly” has RAI (or “bottoms”) and sometimes has IAI, and identifying as a “versatile top” refers to someone who “mostly” has IAI (or “tops”) and occasionally has RAI (Klein, 2009; Wei & Raymond, 2011). Studies have suggested that there is no static or general dichotomous sexual positioning identity among MSM, that sexual role identity varies and may change over time, and may be dependent upon cultural context (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004; Carrier, 1977; Jeffries IV, 2009; Pachankis, Buttenwieser, Bernstein, & Bayles, 2013). However, anal sexual positioning refers to sexual behaviors or practices, while sexual role generally refers to self-ascribed identities that communicate preference for sexual positions. Sexual role identities also communicate contextual information related to gender and power dynamics within a sexual encounter or romantic relationship (Johns et al., 2012; Kippax & Smith, 2001).

Assessments of sexual positioning identity and practice in the literature were considerably inconsistent, limiting generalizability between studies. Most assessments of sexual positioning identity (‘top’, ‘bottom’, ‘versatile,’ etc.) or sexual positioning behaviors (IAI, RAI) were categorical, asking MSM to self-select among the available options (Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2010; Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gómez, Halkitis, et al., 2003; Johns et al., 2012; Klein, 2009; Moskowitz & Hart, 2011; Moskowitz, Rieger, & Roloff, 2008; Pachankis, Buttenwieser, Bernstein, & Bayles, 2013; Tskhay, Re, & Rule, 2014; Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000; Wei & Raymond, 2011). Studies working with Latino MSM have used Spanish terms “activo” and “pasivo” replace the terms “top” and “bottom” (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004; Carrier, 1977). Of these studies, four provided options to identify outside these categories; however, the ways in which this was done varied widely. Most often, MSM were provided an additional opt-out option such as “not applicable”, “no label’, or ‘unspecified,’ but attempts to disentangle what these non-specified options meant to these men in terms of their sexual identity/anal sex preferences was limited/non-existent. About 12% of men stated that these labels were “not applicable” to them, 26% noted that they never used these labels before, 8.2% were unspecified, and about 42% identified outside of the initial ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ identities. Alternative assessment methods were observed in two studies. Pachankis and colleagues (2013) expanded these traditional options to include positioning labels for MSM who “mostly top” or “mostly bottom,” which accounted for up to 44.1% of MSM. Only one additional study was observed that adopted a more continuous measure of sexual role preferences, asking MSM to identify their preferred sexual position on a one-item 5-point scale, where 1=“always top” to 5=“always bottom” (Tskhay et al., 2014).

Currently, there is no standard measure being used to assess sexual positioning identity, preferences, or behaviors for anal sex practice among MSM or MSMW. A dimensional measure that quantifies the positioning activity by a wider range of self-labeling practices may be useful to understand subgroups of MSM. That is, capturing the relationship between sexual positioning identities (including categories of “versatile top” and “versatile bottom”) and sexual practice to understand the relationship between identity and behaviors. To capture those who may not identify in these labels, there is a need for qualitative research to explore identity and behavior among this group of men, in addition to understanding how these labels and practices may vary between MSM and MSMW. Such efforts are needed to uncover what it means to not identify within the range of labels from “top” to “bottom” and create a consistent or better operationalized measure of what or who this group represents.

Future research should also continue to explore what it means for MSM and MSMW to identify within these sex role labels, how these labels are associated sexual practices over time and with different partner types (e.g., casual vs. primary partner, male vs. female) and what these labels mean in the broader social context of MSM and MSMW. Specifically, what role might these labels play when MSM engage with each other in person, via the internet, or online networking for social or sexual encounters. A deeper understanding of how identity labeling may differ or have different effects on sexual health behaviors among different MSM with regard to sexual positioning identities and practices (e.g. among “tops,” “bottoms,” “versatiles” etc.) is needed. Relatedly, most studies treat MSM and MSMW as one homogenous risk group instead of dynamic subcultures that can play an integral part of men’s social and sexual lives.

Epidemiology of Sexual Positioning Practice

Extant research shows varying demographic differences in prevalence of anal sexual positioning practice. Initial research on this issue suggested that being versatile may have been specific to middle and upper class Caucasian American MSM and may not be found among MSM of other ethnicities or socioeconomic backgrounds (Carrier, 1977). However, more recent and diverse samples of MSM show that some men may take versatile roles and practice both IAI and RAI (Grov et al., 2010; Husbands et al., 2013; Johns et al., 2012; Klein, 2009; Moskowitz & Hart, 2011; Pachankis et al., 2013). Data show that the range of MSM and MSMW identifying at “top” ranges from 18%–35%, identifying as “bottom” ranges from 23%–42%, identifying as “versatile” ranges from 42%–47%, and responses of “not applicable” have been highlighted among up to 12% of MSM (Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gómez, Halkitis, et al., 2003; Klein, 2009; Moskowitz et al., 2008).

Seven (30.4%) of these articles suggest that self-labels for positioning among MSM significantly correlate with anal sex behaviors. Previous work on MSM and anal sex practice suggests that MSM who identified as “top” had higher frequency and likelihood of IAI compared to those who identified as either “versatile” or “bottom,” and MSM who identified as “bottom” had higher frequency and likelihood of RAI compared to MSM who identified as “top” or versatile” (Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gómez, Halkitis, et al., 2003; Moskowitz et al., 2008; Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000; Wei & Raymond, 2011). As previously noted, MSM who identified as “versatile” were found to have varying frequencies of IAI and RAI (Lyons et al., 2011; Wei & Raymond, 2011).

Review of these sexual positioning self-labels shows occasional inconsistency between how men identify their sexual role compared to their sexual positioning practice. In one study, data showed that MSM who identified as “top” and “versatile” reported more IAI than those who identified as “bottom” (96% and 93.2% among “tops” and “versatiles,” respectively, versus 39% among “bottoms”). Additionally, MSM who identified as “bottom” were reportedly more likely to have RAI compared to those who identify as “top” or “versatile” (100% among “bottom” versus 41.4% among “tops” and 79.5% among “versatile”) (Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gómez, Halkitis, et al., 2003). But these data reveal not all MSM who identify as “top” practice IAI 100% of the time, and not all MSM who identify as “versatile” practice IAI and RAI with even frequencies, and MSM who identify as “bottom” do not solely practice RAI. While there is no consistent proportion of sexual role identity across these studies, it appears that highest proportion of MSM using these labels are those who identify as “versatile (Lyons et al., 2011; Moskowitz, Rieger, & Roloff, 2008; Pachankis et al., 2013).

Data also show that some MSM may change sexual positioning identity, and subsequently sexual positioning practices. With age, sexual positioning identity and practice change as a result of personal growth related to increased experience, increased confidence, and increased self-awareness (Pachankis et al., 2013). Of note, levels of RAI were lower as age groups increased; 28% of MSM ages 16–29 reported RAI, while 20% ages 30–49 and 15% of MSM ages 50 and older reported RAI. Additionally, MSM over 50 were more likely to report highest levels of versatility compared to the younger age groups (Lyons et al., 2011). Among a sample of men aged 40 and older, the younger MSM group (men under 60) were more likely to report RAI compared MSM over 60 (Jacobs et al., 2010). Only two studies in this review highlight differences in sexual positioning practices by age, and none of these studies qualitatively explore developmental trajectories for sexual positioning practices among MSM or MSMW. More research is needed to understand the role that age plays in the contexts of sexual positioning practices for MSM and MSMW, specifically how sexual positioning practices develop along the life course. Research should also standardize measures evaluating the relationship between self-labeling and actual anal sex positioning practice.

Contexts of Sexual Positioning Practice: Masculinity Stereotypes, Power, Partner Type, and HIV Status

Contexts that may influence sexual positioning and sexual decision making among MSM and MSMW have not been comprehensively assessed. The relationship between perceptions of masculinity stereotypes, power, partner type, and HIV status remain under explored in the context of sexual positioning and versatility. Even less is known about the ways these contextual influences may or may not differ between MSM and MSMW. This review highlights these constructs to illustrate the dynamic contexts under which these positioning identities and practices occur.

Masculinity Stereotypes

Eight (34.7%) of the articles in this review highlight issues of masculinity stereotypes related to sexual positioning practice. MSM perceptions of masculinity may be important when examining sexual positioning practice, including self-perceived masculinity, perceptions of partner masculinity, and penis size (Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2009; Johns et al., 2012). Some MSM refer to sexual positioning as highly gendered identities reflecting heterosexual gender roles and “top” and “bottom” identities representing varying degrees of “gayness”: “tops” were characterized as more masculine and “straight” compared to “bottoms” who are characterized as feminine and “gay” (Johns et al., 2012). Masculinity stereotypes were particularly emphasized among studies with Latino MSM. Active sexual roles (i.e. “top”) among gay and bisexually identified Latino men and IAI are often associated with social and cultural construction of masculinity (Agronick et al., 2004; Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004). Among Latino gay men, passive roles (i.e. “bottom”) and RAI are often associated with “feeling” or “acting like” a woman (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004; Jeffries IV, 2009). Younger Latino gay and bisexual men who engage in IAI may be less likely to consider themselves “woman-like” or “gay” (Agronick et al., 2004; Carrillo, 2002). Interestingly, some MSM noted versatile partners as ideal because they are perceived as more stable and provide an opportunity to relinquish masculinity stereotypes (Johns et al., 2012).

MSM may also be able to discern partner preferences as well vis-à-vis perceptions of masculinity; MSM who perceived themselves as more masculine correctly identified MSM who prefer to “bottom” through relative facial cues and MSM who perceived themselves as more feminine correctly identified MSM who prefer to “top” through the same mechanism (Tskhay et al., 2014). These subjective assumptions of partners’ sexual roles may be a precursor to sexual scripts underlying sexual encounters that might subsequently affect sexual positioning practice, condom use, or ability to engage in condom negotiation. However, our understanding of sexual positioning preferences and practices with respect to masculinity-based stereotypes is limited. Masculinity constructs are self-reported and relative to individual perception and many studies on sexual identity and practices lack standardized measures to assess the concept of what masculinity and femininity are.

As an extension of what may involve masculinity-based stereotypes, self-perceived penis size was statistically significantly related to sexual positioning as well. MSM who perceived their penis size to be below average size were more likely to identity as a “bottom” and men who perceived their penis seize to be above average size were more likely to identify as “top” (Grov et al., 2010). MSM who mostly practiced IAI were more likely to report having larger erect penises and more likely to perceive themselves to be masculine. By contrast, MSM who mostly practiced RAI were more likely to report having smaller erect penises and more likely to perceive themselves as feminine (Moskowitz & Hart, 2011). It may be that perceptions of these issues (e.g. penis size or masculinity) are more important than actual objective measures. Relatedly, there is limited awareness on how this contextual issue may differ for gay or bisexually identified men separately or compared to non-gay identified MSM/MSMW. Future research should continue to investigate these masculinity-based stereotypes with respect to sexual positioning identity and practice among MSM and MSMW.

Power

Five (21.7%) of the articles in this review explicitly highlight issues around power and anal sex practice among MSM, four of which provide information through in-depth qualitative interviews with MSM. Data highlight MSM perceptions of “tops” and “bottoms,” where “bottoms” were described as “passive” and tops were described as “powerful” (Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000); these perceived power differentials mimic the perceived power dynamics between men and women in heterosexual interactions. Power during RAI also occurs as a function of perceived pleasure from partners who “top” them (Hoppe, 2011). Some MSM regard the primary distribution of power as one where tops were the dominant partners, structuring the rules of a sexual encounter, and bottoms were passive partners, relinquishing control of their sexual experiences (Johns et al., 2012). Others may also praise the versatility in practicing both IAI and RAI with partners to re-distribute power during sex and not maintain a one-directional relationship of giving and receiving power (Kippax & Smith, 2001). One longitudinal study noted “power” as a reason for 14% of MSM who changed their sexual positioning identity and/or practice over time, though the proportion of MSM who changed from “top” practicing IAI to “bottom” practicing RAI and “bottom” practicing RAI to “top” practicing IAI is unclear (Pachankis et al., 2013).

Commentary around this issue is primarily restricted to qualitative data to date, and lacks complementary evidence exploring the magnitude and direction of power influencing anal sex practices and among MSM. However, it does lead into an extended discussion about other potential psychological underpinnings of sexual positioning practices. Specifically, some MSM practice RAI because it feels good to them, but also enjoy the perception of temporarily giving control of their bodies to their partners as a means for pleasure production as well, deriving pleasure from someone else’s pleasure in addition to their own (Hoppe, 2011). Additionally, some young MSM practice versatility (both RAI and IAI) with partners as a means of deviation from the gendered and stereotypical roles that are attributed to “top” and “bottom” identity/preference (Johns, et al., 2012).

Future research is needed to uncover the way in which power is defined and perceived by MSM and MSMW separately, and how this is expressed emotionally, physically, sexually, and financially; as such contexts likely influence subsequent sexual risk negotiation between male partners (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2004; Hoppe, 2011). Work is needed to more deeply explore power dynamics related to sexual positioning practices among MSMW. Understanding how these power dynamics may affect sexual practices with male and female partners would provide a welcome contribution to the literature.

Partner Type

Sexual encounters occur within a range of sexual partner types for MSM and MSMW. Some men have casual sexual partners with whom they have sex once or a few times but with whom there may be little or no emotional connection. Some have regular or steady partners with whom they may have consistent casual sex over an extended period of time but there is little or no emotional connection. Others have sexual partners within the context of a romantic relationship with whom they maintain an emotional connection as a regular partner or boyfriend (Johns et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2011; Pachankis et al., 2013). Including discussions involving sexual positioning practice by specifically male partner types with MSM and MSMW is critical because the dynamics of negotiating sexual positioning by each of these partners may be different. Five of the articles included in this review highlight differences in sexual positioning decision-making and practice among MSM and MSMW by partner type. For some, differences in partner type, such as sexual encounters with a “hookup” or casual partner versus a committed relationship influenced sexual positioning decision making (Johns et al., 2012). Specifically, within the context of a hookup or causal sexual encounter with men, gender roles aided in the decision process to “top” or “bottom.” Within the context of a romantic long-term relationship, gender roles were not inherent to the negotiation of anal sex positioning behaviors. Within the context of partner types, partner race/ethnicity also inform sexual positioning practice between; some Black MSM and MSMW noted being more likely to “top” for white romantic and casual partners and “bottom” or practice versatility for Black partners, highlighting a deeper sense of fulfillment in their intimate relationships with other Black men and interpreting their intimate relationships with white men as purely sexual (Hubach et al., 2015).

However, the research remains mixed, as differences in partner type do not always affect sexual positioning for anal sex between men (Lyons et al., 2011). A deeper understanding of how and when partner type affects sexual positioning practices among MSM and MSMW is important, since the extant literature suggests that MSM are less likely to use condoms with consistent sexual partners and that “hookups” can often occur in the context of substance use which can also lessen the likelihood of condom-protected sex (Rusch, Lampinen, Schilder, & Hogg, 2004; Sullivan, Salazar, Buchbinder, & Sanchez, 2009). Moreover, a more detailed narrative on how partner types affect sexual positioning practices with female partners for MSMW is also needed.

HIV Status

Data from four studies (18%) included in the review also show that individual and partner HIV status may affect sexual positioning and HIV prevention decision making. Some HIV negative MSM who have had condomless anal intercourse in serodiscordant relationships were insertive and most receptive MSM were HIV positive (Van de Ven et al., 2002). Even in serodiscordant relationships with a regular sexual partner, HIV positive MSM reported more RAI than HIV negative MSM (69% versus 9%) (Van de Ven et al., 2002). In casual sexual relationships among serodiscordant individuals, those who were HIV positive had a higher level of practicing both IAI and RAI compared to HIV negative MSM (58% compared to 44.4%) (Van de Ven et al., 2002). This trend in positioning practices by HIV status has been highlighted as strategic positioning, also known as sero-positioning (Flores, Bakeman, Millett, & Peterson, 2009; J. M. Snowden, Raymond, & McFarland, 2009; Jonathan M. Snowden, Raymond, & McFarland, 2011). This is the act of choosing a different sexual position depending on the serostatus of the sexual partner to prevent HIV acquisition or transmission and practiced within the belief that the risk of HIV acquisition is lessened when “topping” an HIV negative partner (Lyons et al., 2011; Murphy, Gorbach, Weiss, Hucks-Ortiz, & Shoptaw, 2013; Parsons, Halkitis, Wolitski, Gómez, & Study Team, 2003; Van de Ven et al., 2002). Data show that risk for HIV infection was higher among HIV negative MSM who engaged in strategic positioning compared to those who did not (Jin et al., 2009). Data on the prevalence of MSM who explicitly practice seropositioning ranges from 6% to 13%, although other studies have shown patterns of HIV negative MSM only practicing IAI with their HIV positive male partners (Murphy et al., 2013; Snowden et al., 2009; Snowden et al., 2011; Van de Ven et al., 2002). With the recent development of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to help prevent HIV infection, it remains unknown how this biomedical intervention may relate to sexual positioning or seropositioning behaviors among MSM or MSMW as well.

Self-reported HIV-positive status has also been significantly associated with identifying as a “bottom” (Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). Additionally, men who are versatile have been found to be most likely to not know their HIV status (Lyons et al., 2011). Data also show a stronger association between the number of partners and condomless RAI and greater sense of emotional connection and coping with vulnerability among HIV positive men compared to HIV negative men (Bauermeister, Carballo-Diéguez, Ventuneac, & Dolezal, 2009). Additionally, HIV positive MSM and MSMW who practiced condomless RAI were more likely to have depression compared to MSM and MSMW who did not (Parsons, Halkitis, Wolitski, Gómez, & Study Team, 2003). Still, the temporal relationship between HIV status and sexual positioning practice is inconsistent and unclear; especially regarding ways affect may differentially influence these decisions. Have MSM acquired HIV because they prefer RAI, or are they making conscious decisions to practice RAI because they perceive it is safer for their partners? Or, are HIV negative partners preferring partners who are more willing to bottom regardless of HIV status?

Discussion

While sexual positioning practices are related to HIV and STI transmission risk among MSM/MSMW, they have yet to receive an informed discussion in the extant literature. Through this narrative review, we highlight sexual positioning practices among MSM/MSMW in Western cultures, including many dynamic psycho-social forces present and involved in this sexual decision-making process. For many men, sexual positioning practices appear to be fluid, but do not necessarily occur at random. In particular, we drew from the literature ways in which masculinity stereotypes, power dynamics, partner type, and HIV status reflect important contextual elements likely affecting the ways in which sexual positioning practices between men play out.

Conceptual Model and Implications

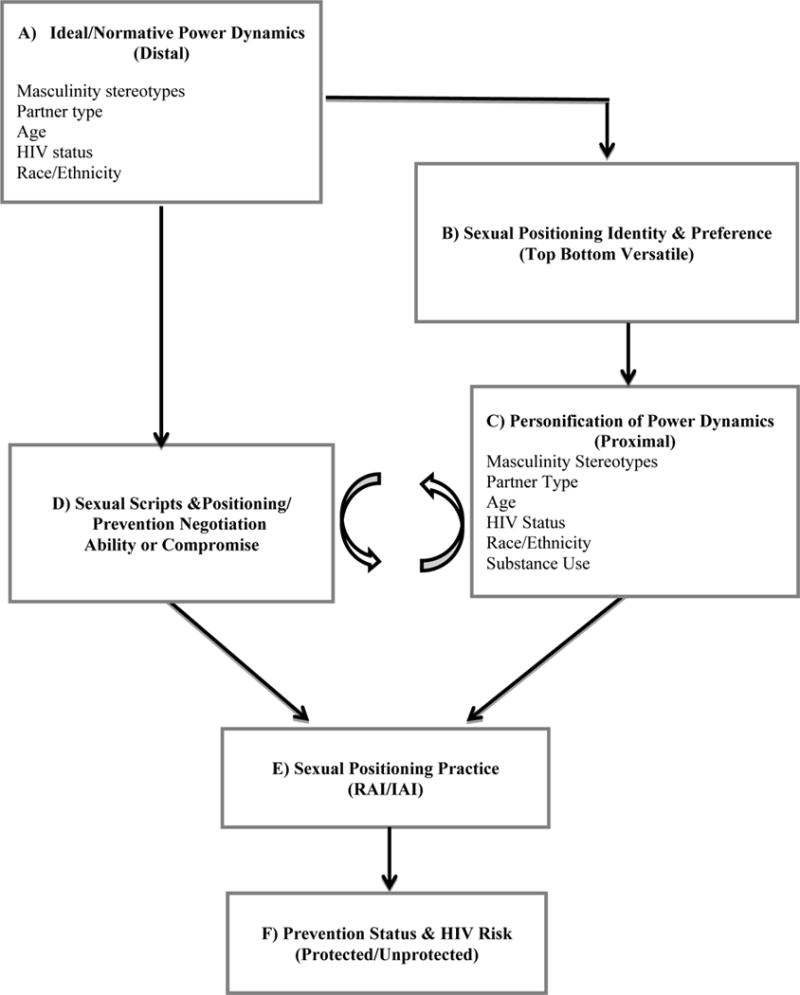

Relatedly, this review suggests ways these contextual sexual positioning factors are interrelated, but the reviewed literature stops short of informing how they might work together to affect HIV vulnerability. Building upon the observations made through our narrative review, we propose a conceptual model that may better capture the relationship between HIV/STI risk and sexual positioning practices among the general population of MSM as a function of masculinity stereotypes, power dynamics, partner type, and HIV status. Through this initial conceptual model we illustrate hypothesized relationships to be more rigorously explored and evaluated in future research (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model of Contexts for Sexual Positioning Practices among MSM and MSMW

As seen in Figure 2, the findings of this review suggest that there may be distal normative power dynamics, including masculinity stereotypes, partner type, and HIV status (Box A) affecting sexual positioning identity and preference (i.e. top, bottom, versatile, etc. preference; Box B) and the sexual scripts that allow for sexual positioning and/or condom negotiation ability within the sexual encounter (Box D). This model also considers individual and partner age and race/ethnicity within these distal and proximal forces as sexual identity and negotiation ability change with age and proximal power dynamics likely vary within and between different ethnic groups of MSM (Bowleg, 2004; Han, 2008; Husbands et al., 2013; Malebranche & Bryant, 2005). Sexual positioning identities and preferences guide the power dynamics present within the sexual encounter (Box C), which has a cyclical relationship with sexual positioning and condom use, implicated in the latitude an individual has to negotiate risk reduction behaviors (Box D). This dynamic and cyclical relationship then results in the practice of RAI or IAI (Box E) leading to the ultimate varying HIV and STI risk (Box F). Future efforts can continue to explore and begin to test the impact of distal normative power dynamics on sexual positioning identity and preference, sexual scripts, and HIV/STI prevention ability with partners and how these dynamics may affect the interpersonal personification of power dynamics within the sexual encounter and evaluate the latitude an individual has to negotiate risk reduction behaviors, which both result in the practice of RAI or IAI (Box E) leading to the ultimate varying HIV and STI risk. Future work should also evaluate the extent to which these processes may differ for MSM and MSMW.

This conceptual model highlights the wide range of psychosocial and psychosexual forces at play within the relational interactions of the sexual encounter that influence “top” and “bottom” practice within a given sexual encounter. Masculinity stereotypes are a salient theme with regard to sex between men; however, it is unclear how the process of perceived masculinity and femininity may be different for MSM and MSMW separately. For example, queer theory suggests the meaning of masculinity and femininity may differ vis-à-vis the performance of bisexual behavior with men versus women by MSMW, reflecting a gendered influence on proximal power dynamics not observed among MSM who do not have sex with women. Similarly, ways in which proximal power dynamics are influenced by the adoption (or non-adoption) of bisexual identity by MSMW may also influence the meaning and desire for sexual positioning practices (Callis, 2009). Insight into these stereotypes, particularly with respect to the relational interactions between men is important to unpack as these may inform spoken or unspoken sexual scripts between sexual partners immediately prior to or during the sexual encounter; part of which may include facial cues that have been described within the respective section. Gagnon and Simon’s (1984) theory of sexual scripting highlights that sexual interactions can be informed by sexual ‘scripts’ derived from cultural scenarios, interpersonal interactions, and intrapersonal characteristics that frame the way people experience different sexual interactions. Masculinity stereotypes may create cues that could be an important precursor to sexual scripts between men and may manifest differently for MSM and MSMW (Husbands et al., 2013; Lick & Johnson, 2015). From our review, it is unclear how sexual scripts may differ for MSM compared to MSMW or how the cultural meanings and values behind masculinity may affect sexual position decision-making within sub-cultures of MSM. Differing conceptions of masculinity might in turn result in different proportions of anal sex positioning practices in different cultural contexts. However, as mentioned previously, scales of masculinity are inconsistent, as studies consider self-reported perceptions of masculinity.

Immediately prior to and within the sexual encounter, proximal power dynamics affecting sexual scripts, condom use, and sexual positioning practices include masculinity stereotypes, age, partner type, and HIV status. We have extended these dynamics to include partner race/ethnicity and substance use as part of proximal forces affecting sexual positioning practices. Research suggests that Black MSM are expected to be “tops” because they are perceived as “hypermasculine” and sexually aggressive (Bowleg, 2004; Husbands et al., 2013; Malebranche & Bryant, 2005), and Asian MSM are expected to be “bottoms” because they are perceived as feminine and submissive (Han, 2008). Research also shows that substance use impairs judgment and reduces behavioral inhibitions, which may increase HIV and STI exposure (Kim, Kent, & Klausner, 2002) and that substance use during recent anal sex among MSM has been found to be associated with having an STI (Downing, Chiasson, & Hirshfield, 2015; Mansergh et al., 2008). Understanding these and other psychosocial underpinnings, such as personal satisfaction claimed via “bottoming” that may differentially influence power dynamics among MSM and MSMW, and ways affect related to levels of internalized homonegativity or optimism about one’s future previously found to be associated with condomless anal sex practices should be explored (Jacobs et al., 2010).

To that end, it is important to understand the contexts for a given sexual encounter as MSM may not simply practice just RAI or IAI in one encounter. Rather, there may also be a wider range of contextual “top” and “bottom” practices with certain partners over others, leading to a wide range of versatility practice among this group. Specifically, MSM may be versatile in that they may 1) practice RAI and IAI with the same partner within the same sexual act, 2) practice RAI and IAI with the same partner separately in different sexual acts, or 3) practice RAI with certain partners and IAI with others. As mentioned previously, risks for HIV and STIs vary by sexual positioning practices, and men who practice both insertive and receptive roles for anal sex may be at high risk for HIV infection via RAI and may also potentiate subsequent HIV infection to others through IAI (Beyrer et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2011; Wolitski & Branson, 2002). This range of versatility (practicing both IAI and RAI) for anal sexual positioning thus increases the chance of infection and transmission to others in this group (van Druten et al., 1992; Wiley & Herschkorn, 1989).

There is little discussion on how these dynamics vary across different ethnic groups and subcultures of MSM such as the house/ballroom community or leather community where concepts of masculinity and femininity, partner type, power dynamics, and HIV status may likely vary in meaning and influence on HIV prevention behavior. When considering the issues of sexual positioning and the ways masculinity, power, partner type, and HIV status intersect to inform safe or less safe sexual practices, subcultural dynamics among MSM and MSMW must be explored. Exploring these dynamics will uncover the ways in which these forces affect ethnic groups and subcultures of MSM/MSMW differently. Future studies should also attempt to uncover additional correlates of sexual positioning practices that may not have been studied such as age, and how these processes may occur as a function of psychosexual development along the life course.

For reasons highlighted in this review, it is imperative that interventions highlight risks associated with positioning preferences but that MSM are not discouraged from practicing sexual activities they prefer to practice. The CDC has identified seven high impact prevention intervention programs that specifically target (HIV negative) MSM in the United States. While the results of these studies show significant impacts on reducing condomless anal sex among MSM, five of these interventions focused on introducing condoms to anal sex for safer sex practice in the absence of any dialogue on sexual positioning practices, or discussion of the dynamic relationship between masculinity, power, partner type, and HIV status as risk factors for HIV infection, condom negotiation, and sexual positioning between MSM (CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group, 1999; Dilley et al., 2002; Kegeles, Hays, & Coates, 1996; Jeffrey A. Kelly, St. Lawrence, Hood, & Brasfield, 1989; O’Donnell, O’Donnell, San Doval, Duran, & Labes, 1998). The other two interventions highlight condomless IAI and RAI as outcomes of interest, but similarly do not explore these outcomes as a consequence of dynamic relational forces of masculinity, power dynamics, partner type, or HIV status (Jones et al., 2008; J A Kelly et al., 1991). Rather than focusing HIV prevention messaging solely on condom usage and minimizing partners, interventions should also encourage MSM and MSMW to explore the motivations of practicing either receptive or insertive anal sex.

While this narrative review provides important insights involving sexual positioning practice among MSM, there are limitations to consider. This review is not a meta-analysis, and does not describe the strength of effects in the literature. As evidenced by the current review, the available literature may still be too sparse to allow for the robustness of sexual positioning relationship to be assessed. Additionally, due to the sampling of the studies included in this review, we cannot systematically explore the concepts of masculinity stereotypes, power dynamics, partner type, and HIV status affect sexual positioning practices among MSM and MSMW separately.

This review also does not focus on sexual orientation, while distinctions are made between MSM and MSMW. As noted throughout this work, the extant literature commenting on this issue do not make behavioral distinctions between gay and bisexually-identified men versus other men who have sex with men, limiting our ability to highlight distinctions that may exist for these two groups separately. Currently, it is unclear how the psychosexual decision-making process may differ for gay and/or bisexually identified men, and how power dynamics with respect to sexual positioning and condom use manifest with women differently for bisexual men. Some bisexual men suggest a common perception that women are “safer” sexual partners than men, which inspire lower likelihood of condom usage with women and more condom usage with men regardless of sexual positioning, despite beliefs of being a “bridge” for HIV transmission to female partners (Dodge, Jeffries IV, & Sandfort, 2008; Hubach et al., 2013; Malebranche, 2008; Millett, Malebranche, Mason, & Spikes, 2005).

Additionally, this review does not explore drug use as a correlate of sexual practice, and has been found to affect sexual positioning and sexual risk-taking (Rusch et al., 2004), which may be further affected by the soliloquy of gender-based power dynamics experienced by syndemic-affected MSM (i.e. physical and sexual victimization, depression, resource instability (Kubicek, McNeeley, & Collins, 2014; Parsons et al., 2003; Stall et al., 2003; Williams, Wyatt, Resell, Peterson, & Asuan-O’Brien, 2004) This review focuses on identity and sexual positioning rather than the influence of drugs with sexual positioning practice to foster the development of a conceptual framework. This review also does not consider the relationship between sexual positioning identity and oral sex practice. This may be an area of further exploration in future research, particularly as it relates to high rates of extragenital (i.e. pharyngeal) STIs in this population (Jiddou, Alcaide, Rosa-Cunha, & Castro, 2013; Kent et al., 2005; Rietmeijer & McFarlane, 2009), and their role in facilitating HIV infection (Dallabetta & Neilsen, 2005; Rietmeijer & McFarlane, 2009). Still, this narrative review offers an initial synthesis of the literature describing this important aspect of not only HIV and STI prevention but the lives of MSM across cultural groups. The results of this review and our conceptual model offer preliminary insights into important forces to be studied with this issue, to not only understand the sexual behaviors of MSM groups, but to prevent negative sexual health outcomes.

References

- Agronick G, O’donnell L, Stueve A, Doval AS, Duran R, Vargo S. Sexual Behaviors and Risks Among Bisexually- and Gay-Identified Young Latino Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(2):185–197. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030249.11679.d0. http://doi.org/10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030249.11679.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Carballo-Diéguez A, Ventuneac A, Dolezal C. Assessing motivations to engage in intentional condomless anal intercourse in HIV-risk contexts (“bareback sex”) among men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2009;21(2):156–168. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.2.156. http://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, Brookmeyer R. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. 2012a;380(9839):367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. Love, Sex, and Masculinity in Sociocultural Context HIV Concerns and Condom Use among African American Men in Heterosexual Relationships. Men and Masculinities. 2004;7(2):166–186. http://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X03257523. [Google Scholar]

- Callis AS. Playing with Butler and Foucault: Bisexuality and Queer Theory. Journal of Bisexuality. 2009;9(3–4):213–233. http://doi.org/10.1080/15299710903316513. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Nieves L, Díaz F, Decena C, Balan I. Looking for a tall, dark, macho man … sexual-role behaviour variations in Latino gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2004;6(2):159–171. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691050310001619662. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier J. “Sex-role preference” as an explanatory variable in homosexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1977;6(1):53–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01579248. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF01579248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier JM. Mexican Male Bisexuality. Journal of Homosexuality. 1985;11(1–2):75–86. doi: 10.1300/J082v11n01_07. http://doi.org/10.1300/J082v11n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo H. The night is young: Sexuality in Mexico in the time of AIDS. xiii. Chicago, IL, US: University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects Research Group. Community-level HIV intervention in 5 cities: final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(3):336–345. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Gay and Bisexual Men | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC. 2015 Retrieved January 4, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men — 21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(37):1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS, Coleman R. Aids-Related Stigmatization and the Disruption of Social Relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9(2):163–177. http://doi.org/10.1177/0265407592092001. [Google Scholar]

- Dallabetta G, Neilsen G. Efforts to control sexually transmitted infections as a means to limit HIV transmission: What is the evidence? Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2005;7(1):79–84. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0027-8. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-005-0027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Sabatino J, Lihatsh T, Adler B, Casey S, McFarland W. Changing Sexual Behavior Among Gay Male Repeat Testers for HIV: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of a Single-Session Intervention. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;30(2):177–186. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00006. http://doi.org/10.1097/00042560-200206010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Jeffries IV W, Sandfort TGM. Beyond the Down Low: Sexual Risk, Protection, and Disclosure Among At-Risk Black Men Who Have Sex with Both Men and Women (MSMW) Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):683–696. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9356-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9356-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 1999;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores SA, Bakeman R, Millett GA, Peterson JL. HIV risk among bisexually and homosexually active racially diverse young men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(5):325–329. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181924201. http://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181924201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye V, Fortin P, MacKenzie S, Purcell D, Edwards LV, Mitchell SG, … Latka MH. Managing identity impacts associated with disclosure of HIV status: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Care. 2009a;21(8):1071–1078. doi: 10.1080/09540120802657514. http://doi.org/10.1080/09540120802657514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. The Association Between Penis Size and Sexual Health Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;39(3):788–797. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9439-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. A qualitative exploration of the relationship between racism and unsafe sex among Asian Pacific Islander gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):827–837. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9308-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, Wolitski RJ, Purcell DW, Gómez C, Halkitis P. Sexual behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: what’s in a label? Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(2):179–188. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552179. http://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T. Circuits of power, circuits of pleasure: Sexual scripting in gay men’s bottom narratives. Sexualities. 2011;14(2):193–217. http://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711399033. [Google Scholar]

- Hubach RD, Dodge B, Goncalves G, Malebranche D, Reece M, Pol BVD, Fortenberry JD. Gender Matters: Condom Use and Nonuse Among Behaviorally Bisexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;43(4):707–717. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0147-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubach RD, Dodge B, Schick V, Ramos WD, Herbenick D, Li MJ, Reece M. Experiences of HIV-positive gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men residing in relatively rural areas. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(7):795–809. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.994231. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.994231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husbands W, Makoroka L, Walcott R, Adam BD, George C, Remis RS, Rourke SB. Black gay men as sexual subjects: race, racialisation and the social relations of sex among Black gay men in Toronto. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2013;15(4):434–449. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763186. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.763186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RJ, Fernandez MI, Ownby RL, Bowen GS, Hardigan PC, Kane MN. Factors associated with risk for unprotected receptive and insertive anal intercourse in men aged 40 and older who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2010;22(10):1204–1211. doi: 10.1080/09540121003615137. http://doi.org/10.1080/09540121003615137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries IV WL. A Comparative Analysis of Homosexual Behaviors, Sex Role Preferences, and Anal Sex Proclivities in Latino and Non-Latino Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(5):765–778. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9254-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiddou R, Alcaide M, Rosa-Cunha I, Castro J. Pharyngeal Gonorrhea and Chlamydial Infections in Men who have Sex with Men, a Hidden Threat to the HIV Epidemic. Journal of Therapy & Management in HIV Infection. 2013;1(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax SC, Grulich AE. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS (London, England) 2009;23(2):243–252. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Pingel E, Eisenberg A, Santana ML, Bauermeister J. Butch tops and femme bottoms? Sexual positioning, sexual decision making, and gender roles among young gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;6(6):505–518. doi: 10.1177/1557988312455214. http://doi.org/10.1177/1557988312455214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Gray P, Whiteside YO, Wang T, Bost D, Dunbar E, Johnson WD. Evaluation of an HIV Prevention Intervention Adapted for Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegeles SM, Hays RB, Coates TJ. The Mpowerment Project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(8_Pt_1):1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.86.8_Pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, Andrew ME. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(2):168–171. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.81.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Hood HV, Brasfield TL. Behavioral intervention to reduce AIDS risk activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(1):60–67. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.60. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, Liska S, Gibson S, Hubbard G, Klausner JD. Prevalence of Rectal, Urethral, and Pharyngeal Chlamydia and Gonorrhea Detected in 2 Clinical Settings among Men Who Have Sex with Men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(1):67–74. doi: 10.1086/430704. http://doi.org/10.1086/430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S, Stenger M, Kirkcaldy RD, Llata E, Weinstock H. Increases in Syphilis and Gonorrhea Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. Presented at the 2015 CSTE Annual Conference, Cste. 2015 Retrieved from https://cste.confex.com/cste/2015/webprogram/Paper5018.html.

- Kippax S, Smith G. Anal Intercourse and Power in Sex Between Men. Sexualities. 2001;4(4):413–434. http://doi.org/10.1177/136346001004004002. [Google Scholar]

- Klein H. Sexual Orientation, Drug Use Preference during Sex, and HIV Risk Practices and Preferences among Men Who Specifically Seek Unprotected Sex Partners via the Internet. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6(5):1620–1632. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6051620. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6051620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McNeeley M, Collins S. “Same-Sex Relationship in a Straight World” Individual and Societal Influences on Power and Control in Young Men’s Relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0886260514532527. 0886260514532527. http://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514532527. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lick DJ, Johnson KL. Intersecting Race and Gender Cues are Associated with Perceptions of Gay Men’s Preferred Sexual Roles. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(5):1471–1481. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0472-2. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, Smith G, Grierson J, Smith A, McNally S, Couch M. Versatility and HIV vulnerability: investigating the proportion of Australian gay men having both insertive and receptive anal intercourse. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8(8):2164–2171. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02197.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail C, Williams BG, Campbell C. Relative risk of HIV infection among young men and women in a South African township. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2002;13(5):331–342. doi: 10.1258/0956462021925162. http://doi.org/10.1258/0956462021925162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ. Bisexually Active Black Men in the United States and HIV: Acknowledging More Than the “Down Low”. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Bryant L. Masclulinity & HIV Risk among Black MSM. Presented at the National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Malott RJ, Keller BO, Gaudet RG, McCaw SE, Lai CCL, Dobson-Belaire WN, Gray-Owen SD. Neisseria gonorrhoeae-derived heptose elicits an innate immune response and drives HIV-1 expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(25):10234–10239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303738110. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1303738110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Venkatesh KK. Interactions of HIV, Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Genital Tract Inflammation Facilitating Local Pathogen Transmission and Acquisition. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology (New York, N.Y.: 1989) 2011;65(3):308–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00942.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors: AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries 4th WL, Wilson PA, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Malebranche D, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing “down low”: bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7 Suppl):52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DA, Hart TA. The Influence of Physical Body Traits and Masculinity on Anal Sex Roles in Gay and Bisexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):835–841. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9754-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DA, Rieger G, Roloff ME. Tops, bottoms and versatiles. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2008;23(3):191–202. http://doi.org/10.1080/14681990802027259. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy RD, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw SJ. Seroadaptation in a Sample of Very Poor Los Angeles Area Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(5):1862–1872. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0213-2. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0213-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell CR, O’Donnell L, San Doval A, Duran R, Labes K. Reductions in STD Infections Subsequent to an STD Clinic Vis… : Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1998 doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00010. Retrieved June 5, 2015, from http://journals.lww.com/stdjournal/Fulltext/1998/03000/Reductions_in_STD_Infections_Subsequent_to_an_STD.10.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pachankis JE, Buttenwieser IG, Bernstein LB, Bayles DO. A longitudinal, mixed methods study of sexual position identity, behavior, and fantasies among young sexual minority men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42(7):1241–1253. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Gómez CA, Study Team TSUM. Correlates of Sexual Risk Behaviors among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(5):383–400. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.383.24043. http://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.15.6.383.24043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, for the HIV Incidence Surveillance Group Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietmeijer CA, McFarlane M. Web 2.0 and beyond: risks for sexually transmitted infections and opportunities for prevention. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2009;22(1):67–71. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328320a871. http://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e328320a871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Levy SR. Understanding Women’s Risk for Hiv Infection Using Social Dominance Theory and the Four Bases of Gendered Power. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34(1):21–35. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01538.x. [Google Scholar]