Abstract

Background

Melanoma incidence has increased in recent decades in the United States. Uncertainty remains regarding how much of this increase is attributable to greater melanoma screening activities, potential detection bias and overdiagnosis.

Objective

Use a cross-sectional ecological analysis to evaluate the relationship between skin biopsy and melanoma incidence rates over a more recent time period than prior reports.

Methods

Examination of the association of biopsy rates and melanoma incidence (invasive and in situ) in SEER-Medicare data (including 10 states) for 2002–2009.

Results

The skin biopsy rate increased approximately 50% (6% per year) throughout this 8-year period, from 7,012 biopsies per 100,000 persons in 2002 to 10,528 biopsies per 100,000 persons in 2009. Overall melanoma incidence rate increased approximately 4% (< 1% per year) over the same time period. Incidence of melanoma in situ increased approximately 10% (1% per year), while incidence of invasive melanoma increased from 2002–5 then decreased from 2006–9. Regression models estimated that, on average, for every 1,000 skin biopsies performed, an additional 5.2 (95% CI: 4.1, 6.3) cases of melanoma in situ were diagnosed and 8.1 (95%CI: 6.7, 9.5) cases of invasive melanoma were diagnosed. When considering individual states, some demonstrated a positive association between biopsy rate and invasive melanoma incidence, others an inverse association, and still others a more complex pattern.

Conclusions and Relevance

Increased skin biopsies over time are associated with increased diagnosis of in situ melanoma, but the association with invasive melanoma is more complex.

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma incidence continues to increase in the United States (US), despite declines observed for many other cancer types. While the recent introduction of novel immunologic and targeted therapies has substantially advanced treatment options for late-stage melanoma, currently available population-based data indicate that melanoma-related mortality has remained relatively stable over the past several decades.(1) Persistence of stable disease-related mortality in light of increasing melanoma incidence has raised concerns that the latter may be an epidemiologic artifact reflecting potential disease “over-diagnosis,” rather than true increases in incidence of melanomas having malignant potential.

Overdiagnosis may result from increased detection of otherwise biologically benign lesions that portend no additional mortality risk, a concept that is well described for other cancer sites, including prostate, thyroid, lung, and breast,(2) or from selective diagnosis of indolent disease. Whether due to effects of length time or lead time bias, or to misidentification of mimics as true disease, increased screening may lead to greater detection of disease without appreciably influencing disease-specific morbidity or mortality. Indeed, under some circumstances morbidity may increase. In the specific case of thyroid cancer screening in South Korea, for example, the thyroid cancer “epidemic” followed from the intuitive appeal of screening aided by an emergent business structure comprising fee-for-service physician reimbursement, government payment of costs, and advanced imaging and robotic technologies. Despite detection of many more cases of incident thyroid cancer and considerable utilization of resources, this screening effort resulted in greater treatment-related morbidity without lowering cancer-related mortality(3).

The possibility of melanoma overdiagnosis is supported by prior research among Medicare beneficiaries over age 65 within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry system in an earlier time period. From 1986 to 2001, skin biopsy rates increased approximately 154% (approximately 10% per year) within this patient group, paralleled by a 140% (approximately 9% per year) increase in overall melanoma incidence.(1) U.S. melanoma incidence increased from approximately 8 cases per 100,000 persons in 1975 to 24 cases per 100,000 persons in 2010—a nearly 200% increase—while melanoma-specific mortality rose by a much smaller 32%, from 2.07 to 2.74 deaths per 100,000 persons, over the same 35 year period.(4) Melanoma screening through skin biopsy utilization has been thus characterized as expanding “the population of indolent tumors, with little or no effect on the small population of more aggressive tumors.”(4) Similarly, an analysis of SEER data over the time interval from 1988–2006 found that enhanced surveillance during that period resulted in no decline in the proportion of thick melanomas with unfavorable prognostic characteristics but did correlate with a substantial increase in incidence of melanomas in situ(5). Other evaluations have noted increases in incidence of both thick and thin melaomas, suggesting that overdiagnosis may not be a sufficient explanation.(6)

However, the ecological association between skin biopsy rates and melanoma incidence has not been examined for more recent years, resulting in important knowledge gaps regarding the replicability and applicability of these findings for populations currently at risk for melanoma. Accordingly, we sought to evaluate the association between skin biopsy rates and melanoma incidence among the Medicare population over a more recent period. We hypothesized that a similar, positive association would be observed between skin biopsy rates and melanoma incidence. We also hypothesized that increased skin biopsies would be associated with greater detection of earlier stage disease (i.e. melanoma in situ) compared to more advanced melanoma.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Sample

We conducted a cross-sectional ecological study of Medicare physician claims (Part B) among fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries aged 65 years and older who were diagnosed with melanoma using the SEER-Medicare database. A majority of the U. S. population that is over age 65 receives health insurance through the Medicare FFS program. The SEER-Medicare database links high fidelity patient-level SEER registry cancer information with patient-level administrative billing claims and is widely regarded as the premier source for cancer-related health services and epidemiologic research in the US.(7, 8) Tumor registry data from California, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Utah are included within the SEER-Medicare database.(9)

Our study sample was comprised of two patient subpopulations. The first subpopulation consisted of patients 65 years or older diagnosed with incident melanoma from years 2002 through 2009. The second subpopulation was comprised of patients 65 years and older included within the SEER-Medicare 5% sample of non-cancer beneficiaries residing within SEER registry states over the same time period. Use of both subpopulations was necessary in order to capture both incident disease—which, by definition, occurred only in those patients diagnosed with cancer—as well as skin biopsy utilization among at-risk patients, i.e. those who may be subject to skin biopsy procedures but who have not yet been diagnosed with melanoma (or other malignancies).

Primary Outcome, Exposure, and Covariates of Interest

Our primary outcome was melanoma incidence, estimated per 100,000 Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries. We used SEER registry data indicating depth of tumor invasion to stratify this outcome into the following categories: (a) “melanoma in situ,” (b) “invasive melanoma ≤1mm in depth,” (c) “invasive melanoma >1mm in depth,” and (d) “invasive melanoma any/unknown depth.”

Our primary exposure of interest was the skin biopsy rate (per 100,000 Medicare Part B FFS beneficiaries, and for any indication, skin cancer or not). This was estimated for each SEER state, age, and gender, by counting the number of days on which beneficiaries within the non-cancer 5% sample from SEER-Medicare underwent one or more skin biopsy procedures divided by the number of non-cancer beneficiaries. Skin biopsy procedures were identified using billing claims for corresponding Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. Additional covariates included patient age (categorized as 65 to <75 years, 75 to <85 years, or ≥85 years), gender, SEER registry, and year.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the baseline distribution of skin biopsy rates and unadjusted melanoma incidence rates (stratified by depth of invasion) by covariate across our study sample. Multivariable linear regression was used to evaluate the association between skin biopsy rates and melanoma incidence, adjusted for all other covariates. The unit of analysis for this analytic model was the SEER state in an individual year for a specific age group and gender, yielding 480 (10 states × 8 years × 3 age groups × 2 genders) unique observations.

Recognizing that the magnitude of the effect of skin biopsy rates on melanoma incidence may vary by state and year, we included an interaction term for these covariates in the analysis. This allowed melanoma incidence to vary over time independently by SEER state. The risk-adjusted model was used to estimate the number of additional melanomas stratified by depth of invasion that would be diagnosed per 1,000 skin biopsies. To address apparent changes in invasive melanoma in more recent years, we analyzed associations both overall and in two 4-year time periods, 2002–2005 and 2006–2009.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata SE 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and all statistical tests were 2-tailed with alpha equal to 0.05. The Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study (CPHS # 22983).

RESULTS

Skin biopsy rates among Medicare beneficiaries increased approximately 50% (6% per year) over the study period, from 7,011.6 biopsies per 100,000 persons in 2002 to 10,528.0 biopsies per 100,000 persons in 2009 (Table 1). Overall melanoma incidence rates increased approximately 4% (< 1% per year) over the same time period, from 141.3 cases per 100,000 persons in 2002 to 146.6 cases per 100,000 persons in 2009 (Table 1). After stratifying by depth of invasion, the incidence of melanoma in situ increased approximately 10% from 2002 to 2009 (1% per year), while the incidence of invasive melanoma increased by 12% from 2002 to 2005 (12%), and then decreased by 10% from 2006 through 2009 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics Associated with Melanoma Incidence and Skin Biopsy Rates per 100,000 Medicare Beneficiaries from 2002–2009.

| Characteristic | Skin biopsy | Melanoma in situ |

Melanoma ≤1mm depth |

Melanoma >1mm depth |

All invasive melanoma* |

All stage melanoma (including in-situ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||||||

| 65 to <75 years | 7384.1 | 55.6 | 44.8 | 19.8 | 74.7 | 130.3 | |

| 75 to <85 years | 10645.9 | 75.2 | 54.6 | 32.6 | 101.8 | 177.1 | |

| ≥85 years | 9038.5 | 53.9 | 40.0 | 34.2 | 90.0 | 143.9 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 10634.1 | 100.7 | 76.7 | 42.8 | 140.0 | 240.6 | |

| Female | 7534.6 | 37.7 | 29.0 | 16.0 | 52.5 | 90.2 | |

| SEER registry state | |||||||

| California | 9251.2 | 64.9 | 46.3 | 27.9 | 85.6 | 150.5 | |

| Connecticut | 9369.6 | 72.3 | 55.1 | 26.4 | 92.3 | 164.6 | |

| Georgia | 10904.4 | 52.4 | 49.5 | 26.1 | 88.8 | 141.2 | |

| Hawaii | 3231.5 | 24.0 | 28.7 | 14.9 | 49.5 | 73.5 | |

| Iowa | 5899.5 | 42.0 | 32.9 | 26.1 | 65.9 | 107.8 | |

| Kentucky | 6823.4 | 54.1 | 46.0 | 28.8 | 86.5 | 140.6 | |

| Louisiana | 6148.5 | 42.4 | 32.3 | 18.8 | 61.3 | 103.7 | |

| New Jersey | 10130.4 | 82.6 | 60.3 | 27.0 | 107.1 | 189.6 | |

| New Mexico | 5417.4 | 49.7 | 38.9 | 17.1 | 70.2 | 119.9 | |

| Utah | 9082.8 | 92.8 | 61.4 | 32.9 | 104.1 | 196.8 | |

| Yearly Rates | |||||||

| 2002 | 7011.6 | 59.5 | 42.7 | 23.5 | 81.8 | 141.3 | |

| 2003 | 7229.6 | 56.2 | 44.3 | 23.9 | 82.9 | 139.1 | |

| 2004 | 7829.6 | 55.0 | 47.0 | 27.7 | 87.9 | 142.9 | |

| 2005 | 8454.7 | 59.5 | 50.8 | 27.9 | 91.4 | 150.9 | |

| 2006 | 9021.4 | 65.9 | 49.6 | 29.0 | 90.1 | 156.0 | |

| 2007 | 9396.4 | 67.1 | 49.7 | 27.0 | 87.8 | 154.9 | |

| 2008 | 10046.8 | 65.8 | 49.2 | 25.8 | 86.0 | 151.8 | |

| 2009 | 10528.0 | 65.6 | 45.1 | 25.6 | 81.0 | 146.6 | |

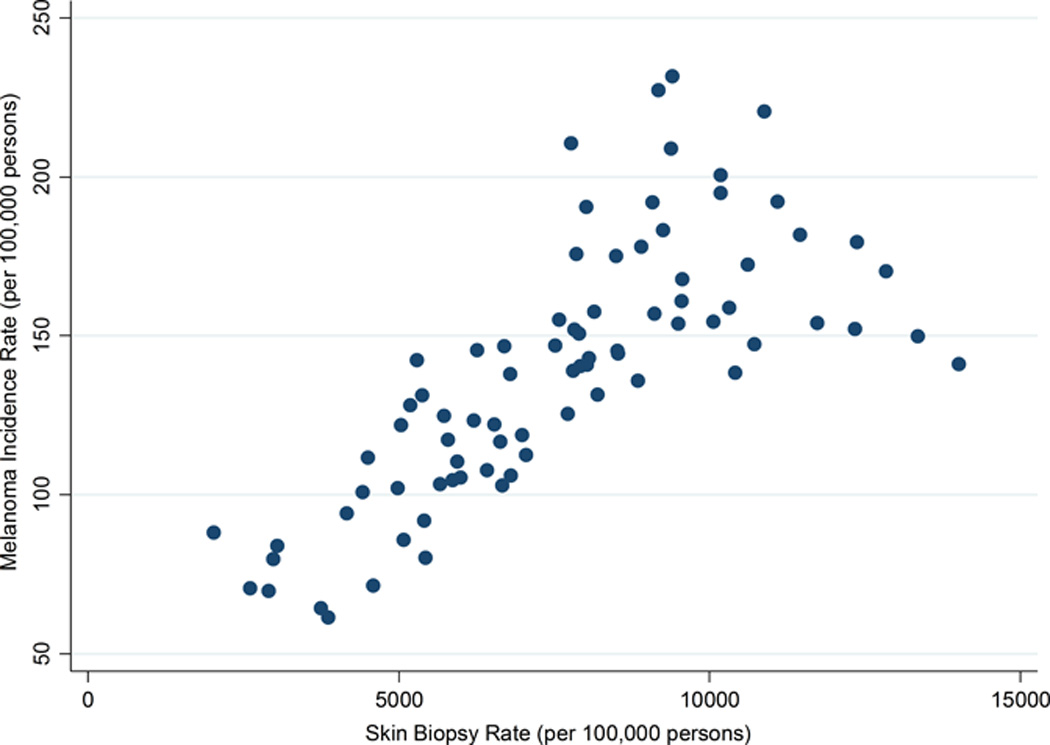

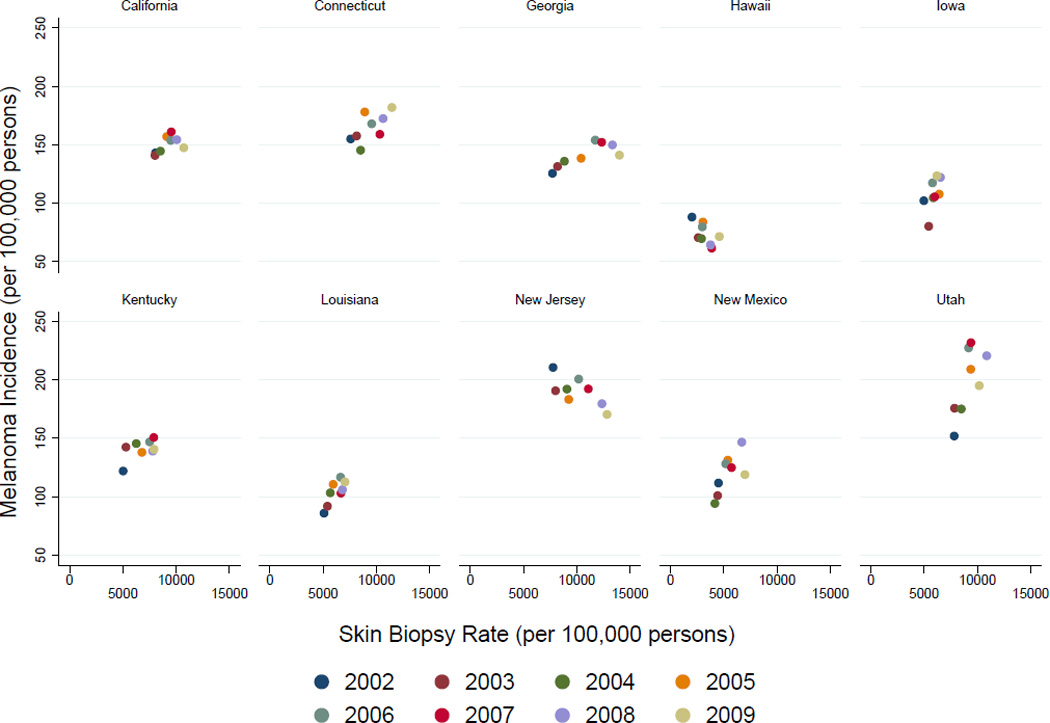

The overall association between melanoma incidence and skin biopsy rate when aggregated across all SEER states and years appeared positive based on the scatterplot of year, state, age, and gender-specific data points (Figure 1). However, associations varied when stratified by state (Figure 2, eFigure 1). These included differences in the magnitude of associations (e.g., the “shallow” slope observed for Kentucky versus the “steep” slopes observed for Iowa and Utah), inverse associations in certain states (e.g. Hawaii and New Jersey), and mixed associations in other states (e.g. California and Georgia).

Figure 1.

Association between Melanoma Incidence and Skin Biopsy Rates, Aggregated Across SEER States, 2002–2009

Figure 2.

Associations between Melanoma Incidence and Skin Biopsy Rates, Stratified by SEER State, 2002–2009

Regression analyses indicated that, on average, for every 1,000 skin biopsies performed among Medicare beneficiaries over the time period studied, an additional 5.2 cases of melanoma in situ were diagnosed (Table 2) and that the number of additional cases was somewhat higher in the early (2002–2005) versus late (2006–2009) time period (5.7 vs. 4.4 additional cases). By comparison, the number of invasive melanomas ≥ 1mm resulting from an additional 1,000 skin biopsies was estimated to be 3.5 over the entire time period and 4.3 from 2002–05 vs. 2.7 from 2006–09 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated number of additional melanoma cases diagnosed per 1,000 skin biopsies+ overall and stratified by time period 2002–2005 and 2006–2009.

| Additional cases per 1,000 biopsies [95% Confidence Interval] by time period.*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth of Invasion | Overall: 2002–2009 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 |

| In situ | 5.2 [4.1, 6.3] | 5.7 [4.0, 7.5] | 4.4 [2.9, 6.0] |

| ≤1mm | 3.6 [2.7, 4.4] | 4.5 [3.1, 6.0] | 3.0 [1.8, 4.2] |

| > 1mm | 3.5 [2.7, 4.2] | 4.3 [3.1, 4.0] | 2.7 [1.6, 3.8] |

| All invasive * | 8.1 [6.7, 9.5] | 11.0 [8.9, 13.1] | 6.3 [4.3, 8.2] |

| All stages ** | 13.3 [11.2, 15.4] | 16.7 [13.5, 19.8] | 10.7 [7.8, 13.6] |

Includes invasive melanoma of unknown thickness.

In situ and invasive melanoma;

all coefficient p-values<0.0001

Incidence rates by depth of invasion were estimated in a regression model that included biopsy rate, age group, gender, state, year and a state by year interactions term.

DISCUSSION

Our results, utilizing patient data from the 10 current SEER states over a more recent time period, confirm the association between skin biopsy utilization and incidence of melanoma in situ among Medicare beneficiaries, but reveal a more complex picture for incidence of invasive melanoma. Concern over detection bias in melanoma diagnosis was raised by Welch et al. in 2005.(1) Their ecologic analysis noted a parallel rise in biopsy rates and melanoma incidence rates in the Medicare Part B FFS population in the 9 original SEER registry states between 1986 and 2001. Subsequently, concerns of melanoma overdiagnosis have been echoed by other investigators. (2, 4) Data from other studies, however, suggest the increase in melanoma incidence is not solely due to overdiagnosis (6), generating substantial controversy both within and outside of the dermatologic community. Our analytic approach was similar to that used by Welch et al.(1), but our findings suggest a more complex relationship between the number of skin biopsies and invasive melanoma than observed in their study with the association changing over time. The heterogeneity of these relationships across states suggest that detection bias, as indicated by biopsy rate, is not a satisfactory explanation of the observed heterogeneity, nor do latitude, heath insurance (all were covered by Medicare), or other surveillance programs provide a ready explanation. Factors not documented in this report, including regional variations in diagnostic practices among pathologists, must be considered and evaluated.

While randomized trials evaluating the impact of skin cancer screening programs are lacking for melanoma, relevant data from two population-based studies have been published. In California, a large population of employees at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories underwent medical screening by dermatologists, resulting in increased diagnosis of in situ melanoma together with a decrease in melanoma mortality(10). In Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, a year-long pilot project from 2003 to 2004 emphasizing screening for melanoma through publicity and public awareness campaigns as well as financial incentives was associated with a 53% increase in melanoma in women, and a 26% increase in men, compared to 18% and 10% in Saarland, a comparator German state with a high quality registry but no screening program. The screening program in Schleswig-Holstein was associated with an approximately 50% reduction in mortality, while neighboring German states lacking the pilot project showed little change in melanoma-specific mortality(11). Also, melanoma-specific mortality increased in Schleswig-Holstein following discontinuation of the pilot program, returning to the national German average of approximately 2.4 deaths per 100,000 persons.

The apparent success of the Schleswig-Holstein pilot program prompted Germany to implement nationwide skin cancer screening in 2008 with the hope of decreasing overall melanoma-specific mortality. However, following the introduction of this national skin cancer screening initiative, no detectable decrease in melanoma-related mortality has yet been observed across the entire German population, despite an initial 30% increase in melanoma incidence resulting from more prevalent screening(12). Recently, some have suggested that the decline in melanoma mortality could be explained by cancer registry misclassification of actual melanoma deaths as deaths from other causes by use of erroneous codes under the rubric of the Tenth Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10)(13). These data remain controversial, and illustrate some of the complexities pertaining to melanoma screening including multifactorial patient-, physician-, and health system-related characteristics and artifactual effects that are neither readily predictable nor easily analyzed.

Our study has limitations. It is ecologic by design and our regression models—while suggestive—do not prove that a causal relationship exists between population-based skin biopsy rates and melanoma over-diagnosis. We were unable to distinguish biopsies involving melanocytic skin lesions from biopsies involving other conditions affecting the skin. We were also unable to adjust for all known confounders, which may otherwise bias our estimates. In addition, our study was restricted to patients enrolled in the Medicare Part B FFS system, and our results may not be generalizable to patients enrolled in Medicare Part C (managed care), private/commercial insurance programs, or those who are uninsured. Our regression modeling may be criticized for the structure of the data points (48 distinct but not independent points per state), which may obscure time trends in the face of strong geographic trends. Finally, these results may not be generalizable to populations outside of the U.S., which may vary in health system structure and access, environmental risk factors, and genetic susceptibilities.

Our data are consistent with the possibility that public health efforts directed towards early detection of melanoma may contribute to melanoma overdiagnosis, particularly with regards to in situ disease. However, it is also possible that increased biopsies are driven, in part, by underlying increases in melanoma incidence rates. Additional research is needed to further clarify the relationship between melanoma screening, incidence, and mortality. Meanwhile, the relationship between increasing biopsy rates and increasing melanoma incidence rates must be interpreted cautiously. It is notable that the incidence rate of invasive melanoma did not continue to increase between 2005 and 2009, while the rate of skin biopsies did continue to increase, suggesting that the relationship between biopsy rates and melanoma rates is not fully understood. Over-diagnosis of other cancers such as breast, prostate and thyroid cancers has been reported, with efforts underway to reduce unnecessary cancer-related screening, surveillance, and other medical interventions (3). Similarly, we believe that continued collaborative efforts are needed to further advance the dermatologic community toward optimized care delivery for all patients at risk for melanoma.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1. Association between Melanoma Incidence and Skin Biopsy Rates for each state stratified by year.

Bulleted Statements.

Persistence of stable melanoma mortality in light of increasing melanoma incidence has raised concerns that the latter may be due to “over-diagnosis”.

The ecologic association between skin biopsy rates and melanoma incidence was observed for 1986–2001 but has not been examined for more recent years, resulting in important knowledge gaps. We find this pattern, suggestive of over-diagnosis, persists for melanoma in situ but not invasive melanoma for 2002–2009.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Tosteson and Ms. Wang had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Weinstock, Lott, Wang, Titus, Tosteson, Elmore; Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: Weinstock, Lott, Wang, Titus, Onega, Nelson, Tosteson, Elmore; Drafting of the manuscript: Weinstock, Lott, Tosteson; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Weinstock, Lott, Wang, Titus, Onega, Nelson, Pearson, Tosteson, Elmore, Piepkorn; Statistical analysis: Weinstock, Lott, Wang, Tosteson; Obtained funding: Elmore, Tosteson, Titus; Administrative, technical, or material support: Weinstock, Lott, Wang, Tosteson, Elmore, Pearson; Study supervision: Weinstock, Lott, Tosteson, Elmore

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA151306 and K05 CA104699). Funding/Sponsor was involved in the design and conduct of the study: No; Collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data: No; Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: No; Decision to submit the manuscript for publication: No

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Lott is an employee of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, LLC, which had no involvement in this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Welch HG, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Skin biopsy rates and incidence of melanoma: population based ecological study. BMJ. 2005;331(7515):481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38516.649537.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn HS, Welch HG. South Korea's Thyroid-Cancer "Epidemic"--Turning the Tide. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(24):2389–2390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1507622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, Nelson P, Ransohoff DF, Welch HG, et al. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):e234–e242. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Melanoma thickness trends in the United States, 1988–2006. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(3):793–797. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, et al. Increasing burden of melanoma in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(7):1666–1674. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma X, Wang R, Long JB, et al. The cost implications of prostate cancer screening in the Medicare population. Cancer. 2014;120(1):96–102. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute. [cited 2016 July 26];About the SEER Registries: National Institutes of Health. 2016 Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser Family Foundation. [cited 2016 July 26];Medicare Beneficiaries as a Percent of Total Population: Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016 Available from: http://kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/medicare-beneficiaries-as-of-total-pop/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider JS, Moore DH, 2nd, Sagebiel RW. Early diagnosis of cutaneous malignant melanoma at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126(6):767–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives?: an observational study comparing trends in melanoma mortality in regions with and without screening. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5395–5402. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katalinic A, Eisemann N, Waldmann A. Skin Cancer Screening in Germany. Documenting Melanoma Incidence and Mortality From 2008 to 2013. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2015;112(38):629–634. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A, Jockel KH. Does skin cancer screening save lives? A detailed analysis of mortality time trends in Schleswig-Holstein and Germany. Cancer. 2016;122(3):432–437. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Association between Melanoma Incidence and Skin Biopsy Rates for each state stratified by year.