Abstract

All living beings are programmed to death due to aging and age-related processes. Aging is a normal process of every living species. While all cells are inevitably progressing towards death, many disease processes accelerate the aging process, leading to senescence. Pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and skin diseases have been associated with deregulated aging. Healthy aging can delay onset of all age-related diseases. Genetics and epigenetics are reported to play large roles in accelerating and/or delaying the onset of age-related diseases. Cellular mechanisms of aging and age-related diseases are not completely understood. However, recent molecular biology discoveries have revealed that microRNAs (miRNAs) are potential sensors of aging and cellular senescence. Due to miRNAs capability to bind to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA of specific genes, miRNAs can prevent the translation of specific genes. The purpose of our article is to highlight recent advancements in miRNAs and their involvement in cellular changes in aging and senescence. Our article discusses the current understanding of cellular senescence, its interplay with miRNAs regulation, and how they both contribute to disease processes.

Keywords: microRNA, Aging, Senescence, Oxidative-stress, Alzheimer’s disease

1. Introduction

Aging is a normal aspect of all living beings. While all cells are inevitably progressing towards death, many disease processes accelerate or deregulate the aging process, leading to abnormal senescence. Neuropathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are associated with such an aging model. Additionally, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and skin diseases have links to improper aging.

In recent years, researchers have elucidated microRNAs (miRNAs) as a potent form of genetic regulation in many species. By binding to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA of specific genes, miRNAs function to prevent the translation of specific genes (Llave et al., 2002). Due to their role in silencing the expression of genes, miRNAs provide a promising target for research involving regulation of cellular processes.

Cellular senescence involves permanent stoppage of growth and programmed cell death. During senescence, various tumor suppressors and death signals inhibit many of the normal functions of the cell. Common tumor suppressor systems such as p53, p21, and p16 are regulated by miRNA expression (Borgdorff et al., 2010; Gómez-Cabello et al., 2013; Overhoff et al., 2014; Ugalde et al., 2011; Yamakuchi et al., 2008). The role of miRNAs in modulating the expression of pathways leading to cellular senescence has led to an increased focus on their role in induced cell death.

Mechanisms carrying out cellular senescence include production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), shortening of telomeres, mitochondrial damage, and cell cycle arrest by production of tumor suppressor proteins. MiRNAs have also been shown to target genes involved in the production of ROS and inflammatory cytokines, a characteristic feature of senescent cells in aging (Bai et al., 2011; Bhaumik et al., 2009; Cho et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2012; Quinn and O’Neill, 2011). Additionally, miR-200c has been shown to be upregulated in endothelial cells in response to stress signals such as ROS, leading to senescence of the cells (Magenta et al., 2011). Other mechanisms for inducing senescence include telomere shortening and alteration of mitochondrial efficiency, and miRNAs that target corresponding mRNAs in those pathways have also been discovered (Bonifacio and Jarstfer, 2010; Li et al., 2011).

While some of the main functions of miRNAs revolve around their effects on inhibiting translation of specific mRNAs into proteins, let-7 has been shown to activate the host’s immune system by mimicking single-stranded viral RNA and activating toll-like receptors (TLRs), which is commonly seen in microglia during neurodegeneration (Lehmann et al., 2012). The interplay of miRNAs and TLRs indicates a unique role of miRNAs, different from that of binding to the 3’ UTR of mRNAs.

With the emphasis placed on miRNAs and their role in aging, it is important to consider the current state of the research on the topic. This article will seek to address the current understanding of cellular senescence, its interplay with miRNA regulation, and how they both contribute to disease processes.

2. Senescence

One of the most powerful management techniques for preventing the generation of neoplastic cell lines is cellular senescence. As previously discussed, tumor suppressors, ROS, telomere shortening, and mitochondrial alteration are common mechanisms by which cellular senescence is initiated. In a study involving squamous cell carcinoma cells, it was found that normal keratinocytes experience cellular senescence in response to exposure to ROS via an upregulation of the p16 tumor suppressor, while cancerous cells with hypermethylation at the p16 promoter did not experience the same effect (Sasaki et al., 2014). Additionally, p16 tumor suppressor can cause senescence by preventing the G1-S phase transition of the cell cycle through inhibition of CDK4/6 activity, leading to net increased activity of the downstream Rb tumor suppressor (Rayess et al., 2012).

A classic tumor suppressor pathway involved in senescence is centered around p53. Mice cells with a mutated p53 gene have been shown to be subject to tumorigenesis (Donehower et al., 1992). In addition to studies with p53 mutations, another study found that restoration of p53 function in p53 mutants led to regression of tumor growth in liver cancer cell lines of mice through the induction of the host’s innate immune system to act on the tumor cells (Xue et al., 2007). Additionally, p53 has been shown to decrease GLUT1 and GLUT4 glucose transporters in osteosarcoma cell lines, an antagonistic mechanism to the characteristic increased intake of sugars in tumor cell lines (Hatanaka, 1974; Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph et al., 2004).

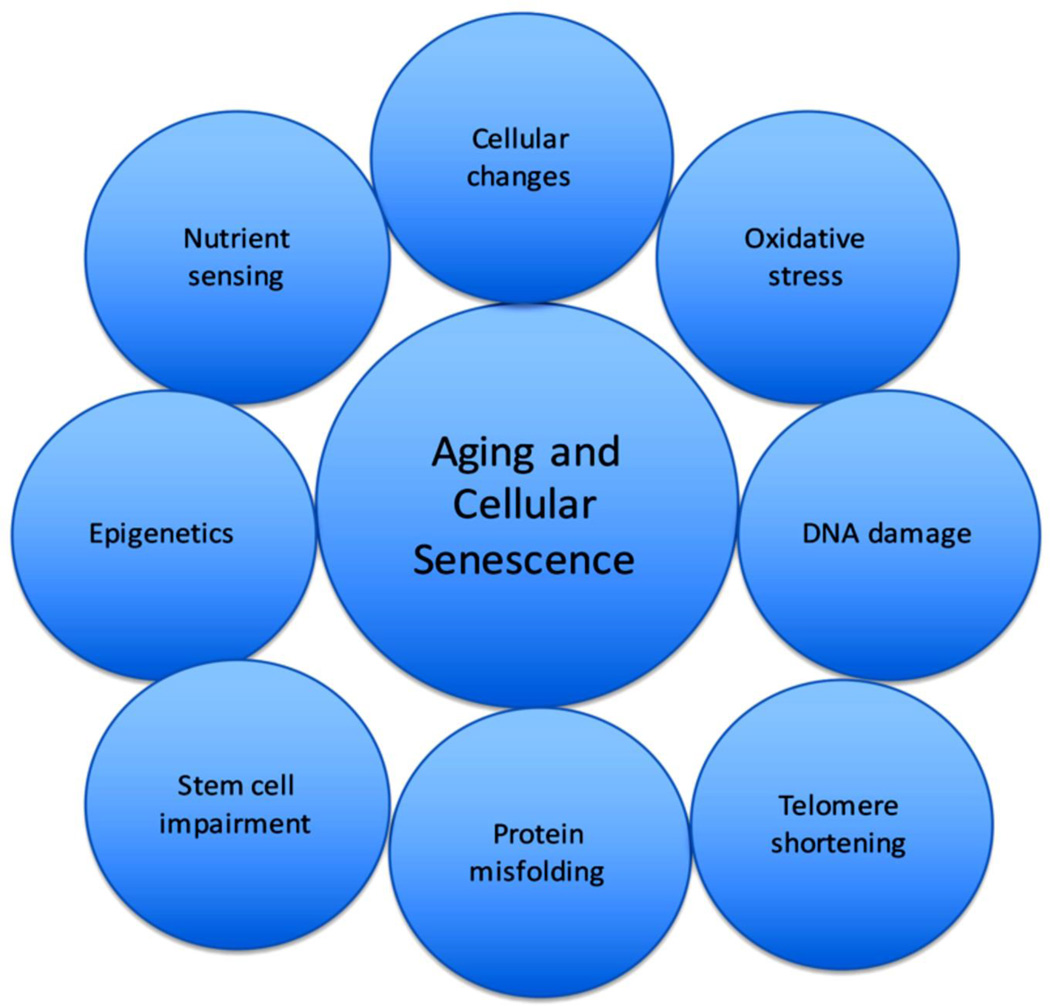

Telomere length and protection are also important factors regulating cell lifespans. Since telomerase is inactive in mature cells, they are vulnerable to aging through the progressive shortening of telomeres until they reach the “Hayflick limit” of cell divisions and telomere shortening, at which cell death occurs (Hayflick, 1965). The shelterin complex, which includes telomeric repeat binding factor 1 and 2 (TRF1 and TRF2), and protection of telomeres 1, and several other proteins, functions to protect from the inappropriate recognition of telomeres by the cell’s DNA repair system (de Lange, 2005). Altering the expression of the shelterin complex could have consequences on the livelihood of cells. As shortened telomeres have been implicated in diseases involving shortened cellular lifespan such as atherosclerosis, a strong possibility remains that telomere length and cellular senescence are interlinked (Ogami et al., 2004). For progenitor cells in which telomerase is still readily expressed, modulation of its expression could alter the viability of these cells. The most common causes of cellular senescence and aging at the cellular level are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The figure describes factors that play into the process of aging and cellular senescence.

3. miRNA synthesis/action

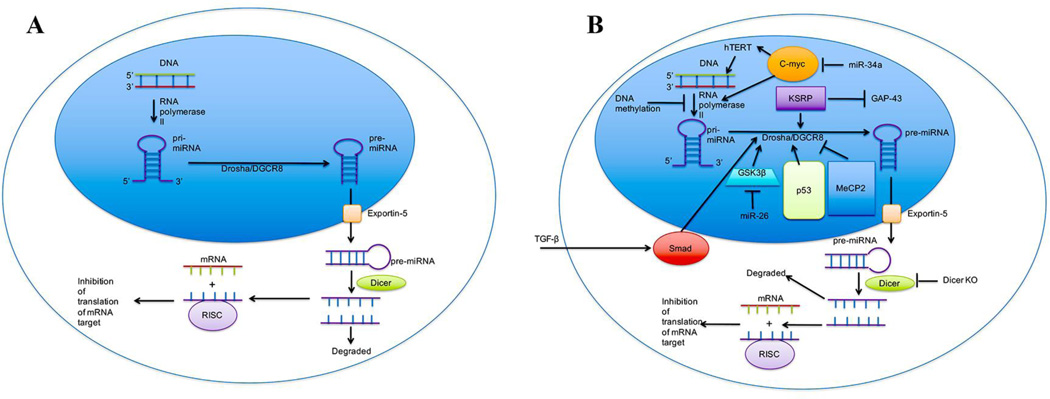

All miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) are the initial transcript produced by RNA polymerase II. Pri-miRNAs are processed in the nucleus by the Drosha protein to produce the approximately 70-nucleotide precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Lee et al., 2003). After pre-miRNA is synthesized, it is shuttled out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm through the exportin-5 channel (Yi et al., 2003). The final maturation steps involve cleavage of a stem loop in the pre-miRNA, which is carried out by the Dicer protein in the cytoplasm, generating mature miRNA guide sequences of about 22-nucleotide length (Bernstein et al., 2001; Hutvágner et al., 2001). At the same time as the final steps of maturation by Dicer are occurring, mature miRNA forms a complex with the Ago2 protein, Dicer, and HIV-1 TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP) called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Gregory et al., 2005). RISC is capable of interacting with the 3’ UTR of mRNAs, leading to either degradation of the mRNA or sequestering of the mRNA from translational machinery depending on the level of sequence complementarity. In addition to being present within the cell, miRNAs can circulate in protein-bound, membrane-bound, or HDL-bound forms in the bloodstream (Arroyo et al., 2011; Hunter et al., 2008; Vickers et al., 2011). Figure 2a shows the normal biosynthesis of miRNA as described above.

Figure 2.

MicroRNA biogenesis. Image A represents normal biogenesis of miRNAs. Image B represents biogenesis in a disease or abnormal condition. Biogenesis of miRNA begins with the transcription of pri-miRNA by RNA polymerase II. The activity of RNA polymerase II can be upregulated in the presence of c-myc, and its action can be inhibited through DNA methylation at CpG sites throughout promoter sites, including those of miRNAs. C-myc expression is downregulated by miR-34a, a commonly seen miRNA in aging processes. A common action of c-myc is the activation of hTERT, leading to increased longevity. After the transcription of pri-miRNA, the Drosha/DGCR8 protein complex acts to trim the pri-miRNA into a second precursor, pre-miRNA. The action of Drosha can be upregulated by GSK3β, Smad, KSRP, and p53, while that of DGCR8 can be downregulated by the action of MeCP2. Smad has been shown to be activated by TGF-β, leading to the nuclear localization of Smad and the subsequent activation of Drosha. Smad’s activation by TGF-β has been shown to be disrupted in skin cells of photoaged adults. GSK3β expression can be inhibited by miR-26a, leading to the promotion of axonal regeneration. KSRP is known to inhibit GAP-43, a promoter of axonal outgrowth in embryos. Upon dissociation with Drosha/DGCR8, pre-miRNA is transported out of the nucleus through the exportin-5 channel into the cytoplasm. In the cytoplasm, Dicer acts to cut the hairpinned double-stranded pre-miRNA into mature single stranded miRNA. From there, one strand is degraded, while the other is incorporated into the RISC complex that targets mRNA to prevent translation. In mice with Dicer knockouts, a rapid Alzheimer’s-like neurodegeneration takes place.

3.1. Regulation of miRNA synthesis

MiRNA expression can be modulated epigenetically through DNA methylation. In the temporal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, a profile of six miRNAs involved in the regulation of a myelination pathway were found to be downregulated by hypermethylation of their CpG sites (Villela et al., 2016). Additionally, the miR-34a gene has been shown to be hypermethylated in ovarian cancer cells, indicating that its downregulation through epigenetics could promote the cancerous phenotype of the cells (Schmid et al., 2016). In a fetal alcohol syndrome model in mice, fetal exposure to alcohol was shown to alter DNA methylation in such a way that upregulated the expression of miRNAs commonly seen in neurological and cognitive deficits (Laufer et al., 2013).

Biogenesis of miRNAs can be controlled at several steps during its synthesis. RNA polymerase II provides the first site of regulation for miRNA expression. C-myc has been shown to promote the elongation step of transcription for RNA polymerase II, leading to increased miRNA expression (Price, 2010; Rahl et al., 2010).

During processing of pri-miRNA by Drosha, the p53 tumor suppressor can associate with the p68 subunit of the Drosha complex and upregulate Drosha’s ability to yield pre-miRNA (Suzuki et al., 2009). In some cancers, p53 is downregulated leading to decreased functionality of Drosha, leading to increased tumor formation (Gurtner et al., 2016). Also, the Drosha protein must be phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) in order for it to be localized to the nucleus of the cell and to be functional (Tang et al., 2011). KH-type splicing regulator protein (KSRP) binds to the stem loop area of pri-miRNA, resulting in an increase in the processing capability of Drosha (Trabucchi et al., 2009). Similarly, activation of cells by TGF-β leads to activation of Smad proteins, their subsequent translocation into the nucleus, and the binding of Smads to stretches of pri-miRNA that allow for more efficient processing by Drosha (Davis et al., 2010). An example of downregulation of the Drosha complex comes when methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) binds to the Drosha complex subunit DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 (DGCR8) protein, preventing effective assembly of the Drosha complex (Cheng et al., 2014). The regulation of miRNA synthesis is shown in Figure 2b with the discussed regulatory elements portrayed.

3.2. Changes in miRNA synthesis corresponding with aging

A common theme seen with aging is the upregulation of miRNA expression, as is seen in the mouse liver (Maes et al., 2008). MiR-34a has been shown to promote senescence in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of the c-myc pathway, leading to inactivation of the hTERT pathway (Xu et al., 2015). The inactivation of c-myc provides an example of a miRNA inhibiting the transcription of all RNAs, including miRNAs.

As aging progresses, cells are exposed to more stress. During stressful conditions, p53 is frequently upregulated. As previously discussed, a higher expression of p53 could potentially improve Drosha’s ability to yield pre-miRNA, thus expediting the maturation process.

One of the significant findings in a twin study on Alzheimer’s disease patients was an increase in DNA methylation in the cortex (Mastroeni et al., 2009). Additionally, DNA methylation in the temporal cortex has been shown to directly target the CpG islands of miRNAs (Villela et al., 2016). By modulating the expression of regulatory miRNAs in the cortex, DNA methylation constitutes a process that can bring about an aging phenotype as seen in cells affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

The expression of GSK3β can be decreased via expression of miR-26a, leading to promotion of neuronal axon regeneration through gene regulation (Jiang et al., 2015). By inhibiting the proliferation of axons, miR-26 represents a case of gene regulation leading to accelerated aging. Consistent with rapid aging and neurodegeneration, increased expression of KSRP also resulted in a decrease in axonal outgrowth via downregulation of the growth factor GAP-43’s mRNA (Bird et al., 2013). Decreasing expression of MeCP2 in glutamatergic neurons of mice led to a shorter lifespan and various neurological abnormalities (Meng et al., 2016). All in all, regulation at the level of miRNA synthesis could have dire consequences on the lifespan of cells.

Photoaging has been shown to disrupt transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling in skin cells, leading to failure to activate the Smad pathway (Han et al., 2005). When skin cells are unable to respond to the TGF-β signal, activation of Drosha by Smad could potentially be disrupted. These results suggest that the characteristic phenotype seen in photoaging could potentially be due to disruption of normal miRNA synthesis.

It has been shown that mice with a Dicer knockout in frontal cortex neurons displayed neurodegeneration (Cheng et al., 2014). An additional study showed that a Dicer knockout in adipose tissue effectively reversed the slowed rate of aging brought about by dietary restriction in mice (Reis et al., 2016). The detrimental effects to longevity seen when Dicer, a key maturing step in the development of miRNAs, is knocked out indicates miRNAs could play a crucial role in many areas of development. Figure 2b also highlights the age-related changes seen in miRNA synthesis.

3.3. Research in lower species

Much of the current knowledge of how miRNAs can induce senescence has come from research done in flies, worms, and mice. How well much of this research translates to humans is yet to be seen, but some of the findings in lower species has shown promising correlation in humans.

Drosophila melanogaster has been shown to develop in accordance with regulation of miRNAs. During overexpression of mirvana/miR-278 in Drosophila flies, tumors start to form in the developing eye, likely due to inhibition of apoptosis (Nairz et al., 2006). Additionally, mutation of miR-14 in Drosophila flies has been shown to decrease lifespan, indicating its role in preventing senescence (Xu et al., 2003).

Some of the earliest recognition of miRNAs were in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) worms. One study showed that the expression of lsy-6 miRNA dictates the left-right development of the nervous system of C. elegans (Johnston and Hobert, 2003). The lifespan of C. elegans is also affected by the expression of miRNAs, with higher lin-4 miRNA expression correlating with decreased lin-14 expression and a longer lifespan (Boehm and Slack, 2005).

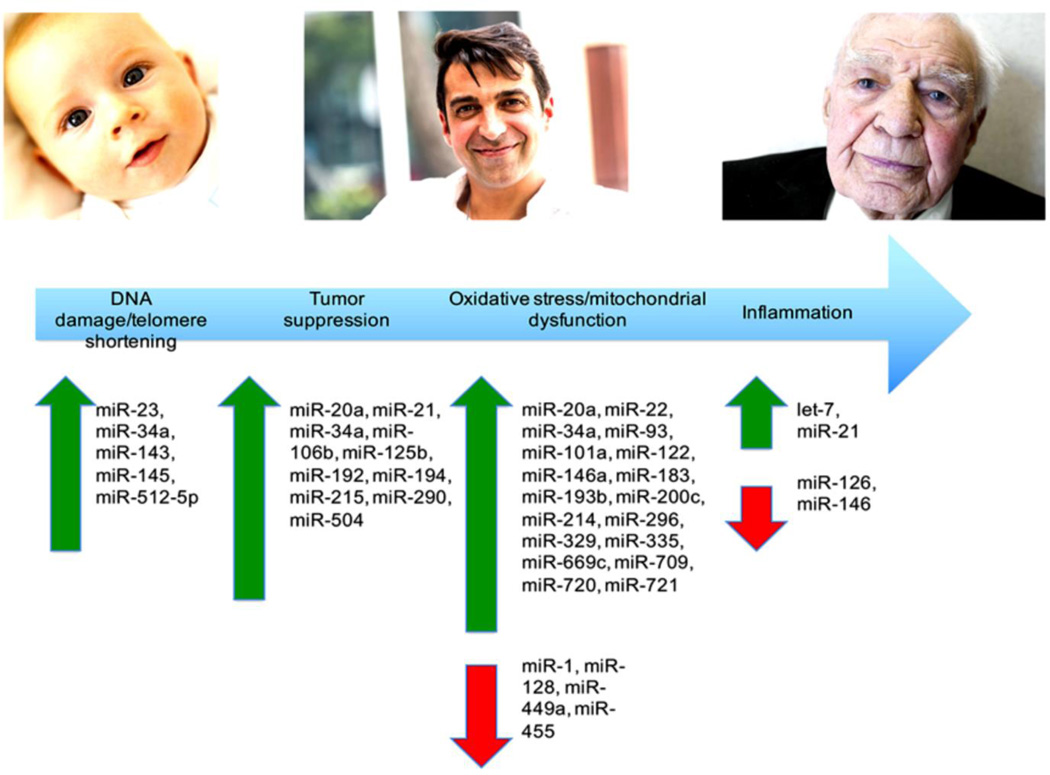

3.4. Interplay of miRNAs and cellular senescence

Many of the processes that carry out cellular senescence are regulated by miRNA expression. Via downregulation of transcripts of genes that typically promote cellular livelihood, miRNAs have become a central focus of research surrounding cellular senescence. Figure 3 portrays the changes in miRNA expression seen during events surrounding cellular senescence and aging.

Figure 3.

The progression of aging at the cellular level can be seen as induction of a series of cellular events. As each event occurs, a corresponding miRNA profile can be seen. The above figure documents some of the miRNA signatures seen during each stage of senescence.

3.4.1. miRNAs and oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is the condition in which the body is unable to completely detoxify ROS. Cells that experience oxidative stress may undergo senescence. In embryonic fibroblasts from a mouse model that rapidly accumulates DNA damage from oxidative stress, miR-449a, miR-455, and miR-128 were found to be significantly downregulated (Nidadavolu et al., 2013). These results mirrored expression found in kidneys of elderly mice. In a study that used benzo-α-pyrene to induce oxidative stress in C. elegans, miR-1, miR-355, miR-50, miR-51, miR-58, miR-796, and miR-84 were found to have modified expression (Wu et al., 2015). These miRNAs may be involved in the regulation of SKiNhead-1, a transcription factor involved in antioxidant response element (ARE) regulation, and gamma-glutamine cysteine synthase heavy chain, an ARE (Wu et al., 2015). In a mouse model with oxidative liver injury induced by treatment with the anti-tuberclosis drug isoniazid, expression of miR-122 in tissue was significantly changed at days 3 and 5 (Wu et al., 2015). In a study of miRNAs expressed in oxidatively stressed hippocampal neurons in senescence accelerated mice, miR-329, miR-193b, miR-20a, miR-296, and miR-130b were found to be upregulated (Zhang et al., 2014). These miRNAs may be involved in a variety of processes, such as regulation of cell growth, apoptosis, signal transmission, and cancer development, especially through the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. MiR-200c expression increases with oxidative stress, leading to senescence and cell apoptosis (Magenta et al., 2011). Expression of miR-183 is upregulated in oxidative stress-induced senescence (Li et al., 2009). In addition, oxidative stress can be initiated by the altered expression of miRNAs. For example, miR-146a acts to downregulate the NOX4 subunit of NADPH oxidase. This miRNA is downregulated in senescence, leading to increased NADPH oxidase activity and further oxidative stress (Vasa-Nicotera et al., 2011). Table 1 summarized the details of miRNAs related to oxidative stress.

Table 1.

Summary of miRNAs related to cellular pathways in Ageing and senescence

| miRNA | Important Processes/Functions | Expression/Relationship | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress/Mitochondrial Dysfunction | |||

| miR-1 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; neurodegenerative disease; acute myocardial infarction; muscular aging |

Decreased in response to oxidative stress. Potential biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. Elevated in the bloodstream of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Expression is downregulated in aging muscle of pig. |

Wu et al., (2015) Margis et al., (2011); Wang et al., (2010); Redshaw et al., (2014) |

| miR-15b | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Inhibits senescence-associated mitochondrial stress. |

Lang et al., (2016) |

| miR-20a | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; tumor suppression; neurodegenerative disease |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. Downregulates p53 mRNA, leading to increased proliferation. Upregulated in the blood leukocytes of Parkinson’s patients. |

Zhang et al., (2014); Poliseno et al., (2008); Soreq et al., (2013) |

| miR-22 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; muscle progenitor cell differentiation |

Targets mRNA of the ETC ATPase, decreasing mitochondrial efficiency. Upregulation promotes smooth muscle cell differentiation |

Li et al., (2011); Zhao et al., (2015) |

| miR-34a | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; tumor suppression; telomere shortening; muscle progenitor cell differentiation |

Promotes all processes listed. Inhibits c-myc function. |

Yamakuchi et al., (2008); Chang et al., (2007); Bai et al., (2011); Yang et al., (2011); Xu et al., (2015); Yu et al., (2015) |

| miR-50 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-51 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-58 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-84 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-93 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; aging |

Upregulated in the livers of aging mice; targets glutathione-S-transferases, which normally protect from oxidative stress. Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. |

Maes et al., (2008); Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-122 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated during oxidative stress. | Song et al., (2015) |

| miR-128 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Downregulated during oxidative stress. | Nidadavolu et al., (2013) |

| miR-130b | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Zhang et al., (2014) |

| miR-146a | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; neurodegenerative disease |

Downregulated during senescence. Normally downregulates the NOX4 subunit of NADPH oxidase. Upregulated in the CSF/ECF of Alzheimer’s patients. |

Vasa-Nicotera et al., (2011); Roggli et al., (2010); Alexandrov et al., (2012) |

| miR-183 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Li et al., (2009) |

| miR-193b | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Zhang et al., (2014) |

| miR-200c | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Magenta et al., (2011) |

| miR-214 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction; osteoporosis |

Upregulated in the livers of aging mice; targets glutathione-S-transferases, which normally protect from oxidative stress. Inhibits osteoblast activity. |

Maes et al., (2008); Wang et al., (2013) |

| miR-296 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Zhang et al., (2014) |

| miR-329 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Zhang et al., (2014) |

| miR-335 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Downregulates antioxidant enzymes in the mitochondria. |

Bai et al., (2011) |

| miR-355 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-449a | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Downregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Nidadavolu et al., (2013) |

| miR-455 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Downregulated in response to oxidative stress. | Nidadavolu et al., (2013) |

| miR-669c | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in the livers of aging mice; targets glutathione-S-transferases, which normally protect from oxidative stress. |

Maes et al., (2008) |

| miR-709 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Upregulated in the livers of aging mice; targets glutathione-S-transferases, which normally protect from oxidative stress. |

Maes et al., (2008) |

| miR-796 | Oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction |

Altered in response to oxidative stress. | Wu et al., (2015) |

| miR-101a | Mitochondrial dysfunction | Targets mRNA of the ETC ATPase, decreasing mitochondrial efficiency. |

Li et al., (2011) |

| miR-210 | Mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagy |

Controls autophagy through mTOR-dependent mechanism and inhibits the mitochondrial ETC. |

Faraonio et al., (2011); Puisségur et al., (2010) |

| miR-494 | Mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagy |

Controls autophagy of the mitochondria through mTOR-dependent mechanism. Likely controls ETC, cell cycle, and mitochondrial translation. |

Faraonio et al., (2011); Bandiera et al., (2011) |

| miR-720 | Mitochondrial dysfunction | Targets ETC ATPase mRNA. | Li et al., (2011) |

| miR-721 | Mitochondrial dysfunction | Targets ETC ATPase mRNA. | Li et al., (2011) |

| Sarcopenia | |||

| Let-7 family | Sarcopenia | Significantly elevated in older subjects | Drummond et al., (2011) |

| miR-126 | Sarcopenia | Important regulator of the transcriptional response to exercise |

Rivas et al., (2014) |

| miR-24 | Muscular aging | Expression is upregulated in aging muscle of pig. | Redshaw et al., (2014) |

| miR-29 | Muscle senescence | Induces cellular senescence in aging muscle | Hu et al., 2014 |

| Inflammation | |||

| let-7 | Inflammation | Activates toll-like receptors (TLRs), promoting inflammation. |

Lehmann et al., (2012) |

| miR-146 | Inflammation | Inhibits inflammation. Potentially a negative feedback system. |

Olivieri et al., (2012); Taganov et al., (2006) |

| Tumor Suppression | |||

| miR-19b | Tumor suppression | Downregulates p53 expression, leading to increased proliferation. |

Fan et al., (2014) |

| miR-21 | Tumor suppression; osteosarcoma/osteoporosis |

Targets p21 tumor suppressor mRNA, leading to increased proliferation. Biomarker for inflammation in pancreatic beta cells. Upregulated in osteosarcoma cells. Downregulated in osteoporotic mesenchymal stem cell |

Gómez-Cabello et al., (2013); Roggli et al., (2010); Ziyan et al., (2011); Yang et al., (2013) |

| miR-29 | Tumor suppression; neurodegenerative disease |

Activates p53, leading to tumor suppression. Potential blood biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. |

Ugalde et al., (2011); Margis et al., (2011) |

| miR-106b | Tumor suppression; aging | Inhibits tumor suppression by targeting p21 mRNA. Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. |

Borgdorff et al., (2010); Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-125b | Tumor suppression; neurodegenerative disease |

Inhibits tumor suppression by targeting p53 mRNA. Expression correlates with Alzheimer’s Disease. |

Hu et al., (2010); Le et al., (2009); Tan et al., (2014) |

| miR-192 | Tumor suppression | Expression is induced by p53. Reduced in cancerous conditions. |

Braun et al., (2008) |

| miR-194 | Tumor suppression | Expression is induced by p53. Reduced in cancerous conditions. |

Braun et al., (2008) |

| miR-215 | Tumor suppression | Expression is induced by p53. Reduced in cancerous conditions. |

Braun et al., (2008) |

| miR-290 | Tumor suppression | Downregulates LRF, leading to increased p16 tumor suppressor expression. |

Pitto et al., (2009) |

| miR-504 | Tumor suppression | Targets p53 mRNA, inhibiting tumor suppression. | Hu et al., (2010) |

| Neurodegenerative Disease | |||

| miR-9 | Neurodegenerative disease | Increased in the CSF and ECF of Alzheimer’s patients. |

Alexandrov et al., (2012) |

| miR-16 | Neurodegenerative disease | Downregulated in the blood leukocytes of Parkinson’s patients. |

Soreq et al., (2013) |

| miR-16-2-3p | Neurodegenerative disease | Potential blood biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. | Margis et al., (2011) |

| miR-22-5p | Neurodegenerative disease | Potential blood biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. | Margis et al., (2011) |

| miR-26a | Neurodegenerative disease | Promotes axonal regeneration by inhibiting GSK3β expression. |

Jiang et al., (2015) |

| miR-26a-2-3p | Neurodegenerative disease | Potential blood biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease | Margis et al., (2011) |

| hsa-miR-27a-3p | Neurodegenerative disease | Expression is decreased in the CSF of Alzheimer’s patients. |

Sala et al., (2013) |

| miR-30a | Neurodegenerative disease | Potential blood biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. | Margis et al., (2011) |

| miR-155 | Neurodegenerative disease; rheumatoid arthritis |

Upregulated in rheumatoid arthritis and the CSF/ECF of Alzheimer’s patients. |

Kurowska-Stolarska et al., (2011); Alexandrov et al., (2012) |

| miR-320 | Neurodegenerative disease | Downregulated in the blood leukocytes of Parkinson’s patients. |

Soreq et al., (2013) |

| miR-331-5p | Neurodegenerative disease | Upregulated in the plasma of Parkinson’s patients. | Cardo et al., (2013) |

| miR-450b-3p | Neurodegenerative disease | Upregulated in the plasma of Parkinson’s patients. | Khoo et al., (2012) |

| miR-505 | Neurodegenerative disease | Upregulated in the plasma of Parkinson’s patients. | Khoo et al., (2012) |

| miR-626 | Neurodegenerative disease | Upregulated in the plasma of Parkinson’s patients. | Khoo et al., (2012) |

| miR-1826 | Neurodegenerative disease | Upregulated in the plasma of Parkinson’s patients. | Khoo et al., (2012) |

| Type II Diabetes | |||

| miR-15a | Type II diabetes | Downregulated in type II diabetes 5–10 years before the onset of the disease. |

Zampetaki et al., (2010) |

| miR-27a | Type II diabetes | Upregulated in type II diabetes; expression levels correlated with higher fasting glucose levels. |

Karolina et al., (2012) |

| miR-29b | Type II diabetes | Downregulated in type II diabetes 5–10 years before the onset of the disease. |

Zampetaki et al., (2010) |

| miR-126 | Type II diabetes; inflammation; atherosclerosis |

Inhibits the NFκB pathway. Alters the expression of VCAM-1 in inflammation. When administered in apoptotic bodies to atherosclerosis patients, improved vasculature by increasing production of chemokine CXCL12. Downregulated in type II diabetes 5–10 years before the onset of the disease. |

Harris et al., (2008); Asgeirsdóttir et al., (2012); Qin et al., (2012); Feng et al., (2012); Zampetaki et al., (2010) |

| miR-150 | Type II diabetes | Upregulated in type II diabetes. Expression levels correlated with higher fasting glucose levels. |

Karolina et al., (2012) |

| miR-193 | Type II diabetes | Upregulated in type II diabetes. Expression levels correlated with higher fasting glucose levels. |

Karolina et al., (2012) |

| miR-223 | Type II diabetes | Downregulated in type II diabetes 5–10 years before the onset of the disease. |

Zampetaki et al., (2010) |

| miR-320a | Type II diabetes | Upregulated in type II diabetes. Expression levels correlated with higher fasting glucose levels. |

Karolina et al., (2012) |

| miR-375 | Type II diabetes | Upregulated in type II diabetes. Expression levels correlated with higher fasting glucose levels. |

Karolina et al., (2012) |

| Aging | |||

| lin-4 | Aging | Increases lifespan in C. elegans. | Boehm et al., (2005) |

| miR-7a | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-14 | Aging | Decreases lifespan in Drosophila flies. | Xu et al., (2003) |

| miR-24-3p | Aging | Biomarker for aging in the saliva. | Machida et al., (2015) |

| miR-29a | Aging | Upregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-29c | Aging | Upregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-148b-3p | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-185 | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-195 | Aging | Upregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-301a/b | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-405a | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-497 | Aging | Upregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| miR-539 | Aging | Downregulated in the livers of aging rats. | Mimura et al., (2014) |

| Telomere Shortening | |||

| miR-23 | Telomere shortening; amino acid metabolism |

Leads to shortened telomeres. Inhibits ATP production via amino acid metabolism. |

Luo et al., (2015); Gao et al., (2009) |

| miR-143 | Telomere shortening | Upregulated in cells lacking TERT. | Bonifacio et al., (2010) |

| miR-145 | Telomere shortening | Upregulated in cells lacking TERT. | Bonifacio et al., (2010) |

| miR-512-5p | Telomere shortening | Targets hTERT mRNA. | Li et al., (2015) |

| miR-101 | Autophagy | Downregulates pro-autophagic genes. | Frankel et al., (2011) |

| miR-204 | Autophagy | Inhibits autophagy. | Mikhaylova et al., (2012) |

| miR-376a* | Autophagy | Controls autophagy through mTOR-dependent mechanism. |

Faraonio et al., (2011) |

| miR-486-5p | Autophagy | Controls autophagy of the mitochondria through mTOR-dependent mechanism. |

Faraonio et al., (2011) |

| Osteoarthritis | |||

| hsa-miR-149* | Osteoarthritis | Downregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| hsa-mir-483-5p | Osteoarthritis | Upregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| hsa-miR-576-5p | Osteoarthritis | Downregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| hsa-miR-582-3p | Osteoarthritis | Downregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| hsa-miR-634 | Osteoarthritis | Downregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| hsa-miR-1227 | Osteoarthritis | Downregulated in the chondrocytes of osteoarthritic patients. |

Díaz-Prado et al., (2012) |

| Development | |||

| lsy-6 | Development | Dictates left/right neuronal asymmetry in C. elegans. |

Johnston et al., (2003) |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | |||

| miR-133a | Acute myocardial infarction; osteoporosis |

Elevated in the bloodstream of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Upregulated in the osteoclast precursors of osteoporotic women. |

Wang et al., (2010); Wang et al., (2012) |

| miR-208a | Acute myocardial infarction | Elevated in the bloodstream of patients with acute myocardial infarction. |

Wang et al., (2010) |

| miR-499 | Acute myocardial infarction | Elevated in the bloodstream of patients with acute myocardial infarction. |

Wang et al., (2010) |

| Tumor Formation | |||

| mirvana/miR-278 | Tumor formation | Upregulation associated with tumor formation in Drosophila flies. |

Nairz et al., (2006) |

3.4.2. miRNAs and mitochondrial dysfunction

Senescence is widely known to be induced by mitochondrial damage. MiRNAs can modulate this induction of senescence by controlling autophagy of the mitochondria. MiR-210, miR-376a*, miR-486-5p, miR-494, and miR-542-5p likely control autophagy through an mTOR-dependent mechanism (Faraonio et al., 2011). On the other hand, miR-101 has been shown to inhibit autophagy by targeting a number of pro-autophagic proteins (Frankel et al., 2011). Evidence has been collected that miR-34a inhibits autophagy in C. elegans and probably in higher organisms as well (Yang et al., 2011). MiR-204 has been shown to be significantly upregulated in proliferative endothelial cells, possibly functioning in autophagy inhibition (Mikhaylova et al., 2012). The electron transport chain (ETC) is another target for miRNA action. MiR-210 is upregulated in senescence and has been shown to act by inhibiting translation of ETC protein machinery (Puisségur et al., 2010). MiR-494 was also shown to induce senescence, likely by controlling ATP synthesis by the ETC, cell cycling, and mitochondrial translation (Bandiera et al., 2011). Other miRNAs such as miR-335 and miR-34a increase ROS production, exerting their effect by downregulating the expression of antioxidative enzymes in the mitochondria (Bai et al., 2011). MiR-23a/b decreases ATP production by targeting proteins involved in ATP synthesis via amino acid catabolism (Gao et al., 2009). Expression of mitochondrial protein SIRT4 is upregulated by stress. MiR-15b acts as an inhibitor of SIRT4 and counteracts senescence associated mitochondrial dysfunction (Lang et al., 2016). Details of miRNAs related to mitochondrial dysfunction are given in Table 1.

3.4.3. miRNAs and p53

P53 is an important protein in the regulation of the cell cycle and preventing tumorigenesis. Its importance is so profound that it is often referred to as the guardian of the genome. P53, along with similar proteins p16 and p21, has a number of interactions and relationships with miRNAs. miR-34a is upregulated by p53 and may act by binding and deactivating SIRT1, an inhibitor of p53, causing a positive feedback loop (Chang et al., 2007; Yamakuchi et al., 2008). Alternatively, it may act by suppressing expression of a different family of p53 inhibiting proteins, the E2F family (Tazawa et al., 2007). MiR-192, miR-194, and miR-215 are also induced by p53, and can also cause cell cycle arrest (Braun et al., 2008). The mRNA encoded by the p53 gene is directly targeted by miR-504 and miR-125b (Hu et al., 2010; Le et al., 2009). MiR-20a also inhibits p53 expression and, therefore, prevents cell death (Poliseno et al., 2008). It acts by downregulating expression of LRF, which inhibits p19ARF, a repressor of p53 inhibitor MDM2 (Polisen et al., 2008; Pomerantz et al., 1998). This downregulation of LRF also allows for increased expression of miR-290, which leads to increased expression of the INK4A gene locus, particularly the p16 tumor suppressor, in mouse fibroblast cells (Pitto et al., 2009). The miR-106b family of miRNAs target the 3’ UTR of the p21 transcript, preventing its translation and function as a tumor suppressor (Borgdorff et al., 2010). P53 was also shown to be a downstream target of miR-19b (Fan et al., 2014). MiR-21 may target p21, as it has been shown to reverse the effects of a deletion of DGCR8, the Drosha auxiliary protein, which usually leads to senescence (Gómez-Cabello et al., 2013). Details of miRNAs related to p53 are given in Table 1.

3.4.4. miRNAs and telomerase shortening

Telomeres are long repeating sequences of nucleotides at the end of linear chromosomes, such as those in humans. They shorten with age, and the process of shortening has been associated with miRNA expression and senescence. TRF1 and TRF2 are proteins essential for maintenance of telomeres. miR-23a has been shown to have the capacity to directly target the 3’ UTR of the TRF2 transcript (Luo et al., 2015). Overexpression of miR-23a caused telomere dysfunction and more rapid onset of senescence. One study showed that a complex of natural yeast proteins caused upregulation of TRF2, while downregulating miR-29a-3p, miR-30a-5p, and miR-34a-5p in human fibroblasts (Yan et al., 2015). Similar to miR-23a and TRF2, miR-155 has been shown to target TRF1 in human breast cancer cells, causing telomeres to be more fragile (Dinami et al., 2014). MiR-138 targets transcripts encoding telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (Mitomo et al., 2008), a subunit of a protein called telomerase that lengthens telomeres by the addition of nucleotides. Human TERT has been identified as a target of miR-512-5p (Li et al., 2015). In a study that examined differences in miRNA expression in TERT-immortalized and non-immortalized human foreskin fibroblasts, miR-143 and miR-145 levels were upregulated in senescent fibroblasts when compared to immortalized fibroblasts (Bonifacio and Jarstfer, 2010). Details of miRNAs related to telomerase shortening are given in Table 1.

3.4.5. miRNAs and inflammation

Inflammation is an immunological process characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain. Inflammation has been implicated in triggering senescence and tends to increase with age. MiR-21 has been demonstrated to be a biomarker for inflammation associated with aging, a process known as “inflamm-aging,” as well as cardiovascular disease (Olivieri et al., 2012a). MiR-21 levels were also increased in the beta cells of the pancreas in response to exposure to inflammatory cytokines, leading to a decrease in expression of proteins involved in insulin secretion (Roggli et al., 2010). In addition, miR-21 decreases the expression of PDCD4, a known promoter of inflammatory activity (Sheedy et al., 2009). miR-146a, like miR-21, is modulated in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines in the beta cells of the pancreas (Roggli et al., 2010). Additionally, miR-146 is known to be involved in regulation of transcripts in two important cellular signaling pathways in cells involved in vascular remodeling: the NFκB and Toll-like receptor pathways (Olivieri et al., 2012b). Activation of these pathways leads to inflammation. MiR-146a and 146b have also been shown to downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in human fibroblasts (Bhaumik et al., 2009). MiR-146 has even been suggested to act in a negative feedback loop, given that its expression increases as the inflammatory response progresses (Taganov et al., 2006). MiR-155 has been demonstrated to have higher expression levels in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, an inflammatory process (Kurowska-Stolarska et al., 2011). MiR-126 is involved in the inflammation process by altering expression of cell-adhesion molecules, like VCAM-1 (Asgeirsdóttir et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2012). It also has a role in reducing the expression of IKBA, which inhibits the NFκB pathway (Feng et al., 2012). Details about miRNAs related to inflammation are mentioned in Table 1.

4. MicroRNAs in specific tissues and disease processes

4.1. Aging

As aging progresses in the livers of mice, miR-93, miR-214, and miR-669c, and miR-709 are expressed at higher levels (Maes et al., 2008). Furthermore, miR-93 and miR-214 were shown to be specifically upregulated in the livers of very elderly mice. Collectively, these miRNAs downregulate the glutathione-S-transferases, which normally protect cells from oxidative processes. The upregulation of these miRNAs could provide a profile unique to senescent hepatocytes. In rat livers, a number of miRNAs were found to have differentiated expression with age. MiR-29a, miR-29c, miR-195, and miR-497 were found to be upregulated (Mimura et al., 2014). MiR-301a, miR-148b-3p, miR-7a, miR-93, miR-106b, miR-185, miR-405a, miR-539, and miR-301b were downregulated (Mimura et al., 2014).

Past research has shown that miRNAs can potentially be used as biomarkers for the detection of certain diseases. This presents an opportunity to possibly use miRNA screening as a means to detecting pathologies wherein senescence is a factor, such as neurodegenerative diseases, especially given the ease of detection and high specificity of miRNAs (Grasso et al., 2014). MiR-34a has been identified as a biomarker for brain aging in mouse models (Li et al., 2011). A pilot study on exosomal miRNAs in saliva suggests that these miRNAs may be potential biomarkers for aging, particularly identifying miR-24-3p as a promising novel candidate (Machida et al., 2015).

4.2. Vascular diseases

Molecular changes that occur as aging progresses can lead to pathological consequences. In vascular diseases, as aging sets in, the expression of the endothelial adhesion molecule ICAM-1 accumulates in the membranes of endothelial cells, leading to age-related vascular pathologies (Zhou et al., 2006). Additionally, type II diabetes can occur due to excessive telomere shortening in beta pancreatic cells (Guo et al., 2011). Other pathologies such as the vascular stiffening associated with hypertension have been associated with accelerated aging models (Gerhard-Herman et Al., 2012). Elasticity and compliance of the heart decrease with age, which causes an increase in its resistance and workload (Stern, 2003). This may in turn cause cardiac hypertrophy. If hypertrophy affects the sinus node, dangerous changes to heart rate and rhythm can occur. In the case of the cardiovascular system, one study showed that acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients displayed elevated miR-1, miR-133a, miR-499, and miR-208a (Wang et al., 2010). MiR-208a can be seen very rapidly in the bloodstream after AMI, providing a quick diagnostic tool (Wang et al., 2010). Several studies have found circulating miRNAs change following stroke in humans (Vijayan et al., 2016). In atherosclerosis, administering miR-126 apoptotic bodies leads to improved vasculature by increasing the production of chemokine CXCL12, leading to increased migration of endothelial progenitor cells to the impacted area (Zernecke et al., 2009).

4.3. Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) also displays several miRNAs that could serve as potential biomarkers. These include miR-15a, miR-29b, miR-126, and miR-223, which have been found to be downregulated in T2DM, even 5–10 years before onset of the disease (Zampetaki et al., 2010). Similarly, miR-27a, miR-150, miR-193, miR-320a, and miR-375 were found to be upregulated, and their expression levels also showed significant correlation with higher fasting glucose levels (Karolina et al., 2012).

4.4. Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases also follow abnormal cellular aging. The pathogenesis of AD has been associated with the shortening of telomeres in the microglial cells of the brain in the presence of amyloid plaques (Flanary et al., 2007). Neurodegeneration in AD occurs in the temporal and parietal lobes, as well as the frontal cortex and cingulate gyrus (Wenk, 2003). Mitochondrial damage has also been shown to affect the neurons of the substantia nigra, correlating with the effects of mild parkinsonian syndrome (Kraytsber et al., 2006). Telomere shortening in blood mononuclear cells and increased markers of oxidative stress have been found to correlate with severe forms of multiple sclerosis, potentially leading to altered inflammation and cellular senescence (Guan et al., 2015). In a rat model representing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), astrocytes were shown to undergo senescence, inhibiting their ability to support motor neurons (Das and Svendsen, 2015).

Expanded triplet repeats are reported to cause multiple neurological diseases, such as Huntington’s, myotonic dystrophy and spinocerebellar ataxias (Nageshwaran et al., 2015). In HD patients, a higher number of CAG repeats correlated with a more rapid clinical progression of symptoms (Rosenblatt et al., 2012). One study showed that the higher number of CTG repeats present in myotonic dystrophy type I correlated with an earlier age of onset of the disease, indicating accelerated aging (Morales et al., 2012).

4.5. Alzheimer’s disease

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), circulating miRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells has been shown to be increased (Schipper et al., 2007). More work in blood cells found a 12-miRNA signature that was shown to be able to identify AD against controls with 93% accuracy, 95% specificity, and 92% sensitivity (Leidinger et al., 2013). In plasma, a 7-miRNA signature was found that could identify AD versus controls with 95% accuracy (Kumar et al., 2013). In cerebrospinal fluid, decreased expression of hsa-miR-27a-3p was found in Alzheimer’s patients (Sala Frigerio et al., 2013). MiR-125b has been suggested as a biomarker for AD upon discovery that its level of expression is correlated with the results of the Mini Mental State Examination (Tan et al., 2014). In the CSF and ECF of Alzheimer’s patients, miR-9, miR-146a, and miR-155 are all upregulated (Alexandrov et al., 2012). A critical analysis of previous reports identified six miRNAs: miR-9, miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-181c, let-7g-5p, and miR-191-5p could be the potential candidate for biomarker studies (Kumar et al., 2016). The discovery of a unique miRNA expression profile in AD patients could open the door for a powerful diagnostic tool for the disease before its deleterious effects set in.

4.6. Parkinson’s disease

MiRNAs have been proposed as biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease as well. MiR-1, miR-22-5p, and miR-29 levels in the blood of patients can be used to differentiate subjects with untreated PD from healthy subjects (Margis et al., 2011). MiR-16-2-3p, miR-26a-2-3p, and miR-30a levels were similarly found to be usable to distinguish treated and untreated PD patients (Margis et al., 2011). Studies on miRNAs in plasma of PD patients have shown upregulation of miR-331-5p, miR-1826, miR-450b-3p, miR-626, and miR-505 (Cardo et al., 2013; Khoo et al., 2012). MiR-16, miR-20a, and miR-320 have been shown to have significantly altered expression in blood leukocytes of PD patients (Soreq et al., 2013).

4.7. Cancer

In many cancers, the inhibition of senescence has been shown to lead to increased proliferation. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor pathway have been shown to lead to tumorigenesis (Donehower et al., 1992). The inhibition of tumor suppressor systems provides a powerful mechanism by which cancer can take hold. Accumulation of mutations has been suggested to be a driving force in both aging and the onset of cancer (Falandry et al., 2014). The incidence of many types of cancer such as colorectal cancer and some types of leukemia increases exponentially with age (Adams et al., 2015).

MiRNA expression profiles have been described for breast cancer cells. In the case of miR-31, its upregulation is seen in breast cancer cells, possibly leading to the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent DNA damage (Cho et al., 2015). MiR-125b is upregulated in breast cancer by entinostat, and the miRNAs act to downregulate the anti-apoptotic erbB2/erbB3 (Wang et al., 2013). The net result of this interaction is apoptosis of the breast cancer cells. By investigating a specific miRNA profile for breast cancer, miRNAs could potentially be tested for diagnostic purposes. The expression of miR-34a in ovarian cancer cells is controlled by hypermethylation of promoter CpG sites (Schmid et al., 2016). Epigenetic silencing of miR-34a through the hypermethylation could lead to cancerous conditions.

4.8. Skin diseases

A number of skin-related disorders are associated with aging, aside from the standard sagging and wrinkling. Common skin disorders that occur with advanced age include decubitus ulcers, xerosis, asteatotic dermatitis, pruritis, and stasis dermatitis (Jafferany et al., 2012). Various viral infections are common with age, including the reactivation of dormant varicella zoster virus, which causes shingles. Different types of fungal infections also increase with age, such as onychomycosis, tinea pedis, tinea cruris, and candidiasis (Jafferany et al., 2012). Jinnin (2015), revealed the role of various miRNAs in common skin diseases (Jinnin, 2015). In 2007, Sonkoly and coworkers, identified a keratinocyte-derived, miR-203 in a panel of 21 different human organs and tissues. miR-203 exclusively expressed by keratinocytes and showed highly skin-specific expression profile. Upregulation of miR-203 in psoriatic plaques leads to downregulation of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS-3), which is involved in inflammatory responses and keratinocyte functions (Sonkoly et al., 2007). Recently, Srivastava and colleagues (2016) unveiled the role of miR-146a in psoriasis patients and mouse model. They observed the genetic deletion of miR-146a leads to earlier onset and induced skin inflammation (Srivastava et al., 2016). Further, miR-217 expression was found to be down-regulated in psoriasis keratinocytes of psoriatic patients (Zhu et al., 2016). However, overexpression of miR-217 inhibited the proliferation of primary human keratinocytes. Therefore, endogenous inhibition of miR-217 increased cell proliferation and delayed differentiation by modulation of Grainyhead-like 2 gene (Zhu et al., 2016).

4.9. Osteoporosis

MiR-21 was found to be upregulated in osteosarcoma cells and downregulated by TNF-α in the mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) of postmenopausal osteoporotic women (Ziyan et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013). One study found that the function of miR-21 was to downregulate the expression of the tumor suppressor RECK (Ziyan et al., 2011). MiR-133a has also been shown to be upregulated in the circulating monocytes (osteoclast precursors) of osteoporotic women and has thus been identified as a peripheral biomarker of osteoporosis (Wang et al., 2012). A similar study found that miR-214 acted to inhibit osteoblast activity in human specimens, acting to antagonize the formation of bone (Wang et al., 2013).

As a biomarker for osteoarthritis, miR-483-5p was shown to be upregulated in chondrocytes of arthritic patients (Díaz-Prado et al., 2012). Additionally, the same study showed that miR-149*, miR-582-3p, miR-1227, miR-634, miR-576-5p, and miR-641 had a lower expression profile in patients with osteoarthritis (Díaz-Prado et al., 2012).

4.10. Skeletal muscle

The life cycle of skeletal muscle can also be modulated by miRNAs. One study showed that miR-29 could lead to muscle progenitor cell (MPC) senescence by targeting the mRNAs of IGF-1, p85a, and B-myb (Hu et al., 2014). IGF-1 and p85a are involved in the IGF-1/PI3K pathway, which is downregulated during muscular senescence, and B-myb inhibits the activity of p16INK4A and p53, potent tumor suppressor proteins.

MiRNAs are known to be instrumental in the differentiation of muscles cells from their stem cell progenitors. In a study involving isolation of different miRNAs from diaphragm and semimebranosus muscle of young and old pigs, differential expression was observed between the two age groups. Older pigs showed reduced expression of miR-1 and miR-206 but increased expression of miR-24 (Redshaw et al., 2014). Further miR-34a has been shown to play an important role in the differentiation of smooth muscle cells (SMC) from pluripotent stem cells via upregulation of sirtuin 1 (Yu et al., 2015). Upregulation of miR-22 has also been shown to be important for SMC differentiation (Zhao et al., 2015).

4.11. Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is a multifactorial disease and it has been characterized by age related, loss of skeletal muscle tissue and strength. It often occurs as a result of atrophy of muscles. Sarcopenia is also associated with acute and chronic disease states, obesity, pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased insulin resistance, fatigue, falls, and mortality (Peng et al., 2012). There are many factors that contribute to cause sarcopenia i.e., inflammatory pathway activation, environmental reasons, mitochondrial abnormalities, reduced satellite cell numbers, loss of neuromuscular junctions (Walston, 2012). There are some cellular processes which can explain aging induced sarcopenia includes changes in hormonal level, protein degradation in muscle, reactive oxygen species and myogenesis (Hu et al., 2014). MiRNAs have multiple gene targets, each target might be regulated by a group of miRNAs (Brown and Goljanek-Whysall, 2015). The investigation of roles of miRNAs in inflammation and sarcopenia will helpful to develop effective targeted therapeutic strategies and also will unravel their roles in immunity and metabolism.

In 2011, Drummond and coworkers studied the aging and miRNA expression in human skeletal muscle using microarray and bioinformatics analysis. In this study, Let7 family members Let7b and Let7e were significantly elevated and it was further validated in older subjects. Further, the data suggested that aging was characterized by a higher expression of Let7 family members that might down regulate genes related to cellular proliferation and higher Let7 expression might be an indicator of impaired cell cycle function possibly contributing to reduced muscle cell renewal and regeneration in older human muscle (Drummond et al., 2011). Rivas and colleagues (2014) tested the novel hypothesis that dysregulation of miRNAs might contribute to reduced muscle plasticity with aging. MiR-126 as an important regulator of the transcriptional response to exercise and reduced lean mass in old men. Further, the study concluded that mechanistic role of miRNA in the adaptation of muscle to anabolic stimulation and reveals a significant impairment in exercise induced miRNA/mRNA regulation with aging (Rivas et al., 2014). Aging-induced muscle senescence results from activation of miR-29 by Wnt-3a leading to suppressed expression of several signaling proteins (p85α, IGF-1 and B-myb) that act coordinately to damage the proliferation of muscle progenitor cells contributing to muscle atrophy. The increase in miR-29 provides a potential mechanism for aging-induced sarcopenia (Hu et al., 2014).

5. Conclusions and Further Directions

Though a relatively young field of research, miRNAs have provided a unique target for future studies to look at epigenetics and how they affect disease processes. The many studies discussed in this article connect miRNA regulation with the induction of cellular senescence and many disease processes. Control of cellular senescence through miRNA expression can occur through targeting of mechanisms of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, telomere shortening, and tumor suppression. The aging of cells could have effects on the biogenesis of certain miRNAs. As shown in Figure 2, various steps in the biogenesis of miRNAs are subject to modulation by various regulators. In the cases studied, many of the modulators of miRNA synthesis had their expression altered during the aging process. It remains a strong possibility that products of the normal aging process could function as promoters or suppressors of miRNA synthesis.

While many miRNAs discussed here apply to more than one system or disease, some are specific to a certain pathology or tissue type. Identifying a clear expression profile for human diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, type II diabetes, acute myocardial infarction, and osteoarthritis could provide potent means of identifying the diseases early on in their onset while viable treatments are still a possibility. Additionally, many miRNAs are also involved with the suppression of mechanisms by which cells are able to induce senescence, indicating a possible role in tumorigenesis.

Future studies could seek to further elucidate miRNA expression profiles in human patients with specific diseases. Additionally, further exploration of specific tissue types undergoing various degrees of aging could further clarify miRNAs with modulated expression in different body systems. The expansion of knowledge regarding miRNA regulation of cellular senescence has implications in a plethora of disease processes as well as the normal aging process. If more information is gathered surrounding these topics, diagnostic techniques for diseases and accelerated aging could be developed and improved with increased rapidity and accuracy.

Highlights.

All living beings are programmed to death due to aging and age-related processes.

Genetics and epigenetics are reported to play large roles in accelerating and/or delaying the onset of age-related diseases.

MicroRNAs are potential sensors of aging and cellular senescence.

MiRNAs can prevent the translation of specific genes and impair cellular functions.

Acknowledgments

Work presented in this article is supported by NIH grants AG042178, AG047812 and the Garrison Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Jasper H, Rudolph KL. Aging-Induced Stem Cell Mutations as Drivers for Disease and Cancer. Cell stem cell. 2015;16:601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov PN, Dua P, Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. microRNA (miRNA) speciation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and extracellular fluid (ECF) Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;3:365–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. PNAS. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgeirsdóttir SA, van Solingen C, Kurniati NF. MicroRNA-126 contributes to renal microvascular heterogeneity of VCAM-1 protein expression in acute inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1630–F1639. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00400.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai X, Ma Y, Ding R, Fu B, Shi S, Chen X. miR-335 and miR-34a promote renal senescence by suppressing mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22:1252–1261. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera S, Rüberg S, Girard M, Cagnard N, Hanein S, Chrétien D, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Henrion-Caude A. Nuclear outsourcing of RNA interference components to human mitochondria. Plos ONE. 2011;6:e20746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik D, Scott GK, Schokrpur S. MicroRNAs miR-146a/b negatively modulate the senescence-associated inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-8. Aging. 2009;1:402–411. doi: 10.18632/aging.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CW, Gardiner AS, Bolognani F. KSRP modulation of GAP-43 mRNA stability restricts axonal outgrowth in embryonic hippocampal neurons. Plos ONE. 2013;8:e79255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Slack F. A developmental timing microRNA and its target regulate life span in C. elegans . Science. 2005;310:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1115596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacio LN, Jarstfer MB. MiRNA profile associated with replicative senescence, extended cell culture, and ectopic telomerase expression in human foreskin fibroblasts. Plos ONE. 2010;5:e12519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff V, Lleonart ME, Bishop CL. Multiple microRNAs rescue from Ras-induced senescence by inhibiting p21(Waf1/Cip1) Oncogene. 2010;29:2262–2271. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun CJ, Zhang X, Savelyeva I, Wolff S, Moll UM, Schepeler T, Ørntoft TF, Andersen CL, Dobbelstein M. p53-Responsive MicroRNAs 192 and 215 are capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10094–10104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Goljanek-Whysall K. microRNAs: Modulators of the underlying pathophysiology of sarcopenia? Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardo LF, Coto E, de Mena L, Ribacoba R, Moris G, Menéndez M, Alvarez V. Profile of microRNAs in the plasma of Parkinson’s disease patients and healthy controls. J Neurol. 2013;260:1420–1422. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol. cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Zhang C, Xu C, Wang L, Zou X, Chen G. Age-dependent neuron loss is associated with impaired adult neurogenesis in forebrain neuron-specific Dicer conditional knockout mice. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2014;57:186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Wang Z, Liao Q. MeCP2 suppresses nuclear microRNA processing and dendritic growth by regulating the DGCR8/Drosha complex. Dev. cell. 2014;28:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Dimri M, Dimri GP. MicroRNA-31 is a transcriptional target of histone deacetylase inhibitors and a regulator of cellular senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:10555–10567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.624361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das MM, Svendsen CN. Astrocytes show reduced support of motor neurons with aging that is accelerated in a rodent model of ALS. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:1130–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Nguyen PH, Lagna G, Hata A. Smad proteins bind a conserved RNA sequence to promote microRNA maturation by Drosha. Mol. cell. 2010;39:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes. Dev. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Prado S, Cicione C, Muiños-López E, Hermida-Gómez T, Oreiro N, Fernández-López C, Blanco FJ. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal and osteoarthritic human chondrocytes. BMC. Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012;13:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinami R, Ercolani C, Petti E. miR-155 drives telomere fragility in human breast cancer by targeting TRF1. Cancer res. 2014;74:4145–4156. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MJ, McCarthy JJ, Sinha M, Spratt HM, Volpi E, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Aging and microRNA expression in human skeletal muscle: a microarray and bioinformatics analysis. Physiol. Genomics. 2011;43:595–603. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00148.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falandry C, Bonnefoy M, Freyer G, Gilson E. Biology of cancer and aging: a complex association with cellular senescence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:2604–2610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Yin S, Hao Y, Yang J, Zhang H, Sun C, Ma M, Chang Q, Xi JJ. miR-19b promotes tumor growth and metastasis via targeting TP53. RNA. 2014;20:765–772. doi: 10.1261/rna.043026.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraonio R, Salerno P, Passaro F, Sedia C, Iaccio A, Bellelli R, Nappi TC, Comegna M, Romano S, Salvatore G, Santoro M, Cimino F. A set of miRNAs participates in the cellular senescence program in human diploid fibroblasts. Cell. Death. Differ. 2011;19:713–721. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Wang H, Ye S. Up-regulation of microRNA-126 may contribute to pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis via regulating NF-kappaB inhibitor IκBα. Plos ONE. 2012;7:e52782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanary BE, Sammons NW, Nguyen C, Walker D, Streit WJ. Evidence that aging and amyloid promote microglial cell senescence. Rejuvenation. Res. 2007;10:61–74. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel LB, Wen J, Lees M, Høyer-Hansen M, Farkas T, Krogh A, Jäättelä M, Lund AH. microRNA-101 is a potent inhibitor of autophagy. EMBO J. 2011;30:4628–4641. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard-Herman M, Smoot LB, Wake N. Mechanisms of premature vascular aging in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Hypertension. 2012;59:92–97. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Cabello D, Adrados I, Gamarra D. DGCR8-mediated disruption of miRNA biogenesis induces cellular senescence in primary fibroblasts. Aging cell. 2013;12:923–931. doi: 10.1111/acel.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso M, Piscopo P, Confaloni A, Denti MA. Circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders. Molecules. 2014;19:6891–9910. doi: 10.3390/molecules19056891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JZ, Guan WP, Maeda T, Guoqing X, GuangZhi W, Makino N. Patients with multiple sclerosis show increased oxidative stress markers and somatic telomere length shortening. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015;400:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo N, Parry EM, Li LS. Short telomeres compromise β-cell signaling and survival. Plos ONE. 2011;6:e17858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner A, Falcone E, Garibaldi F, Piaggio G. Dysregulation of microRNA biogenesis in cancer: the impact of mutant p53 on Drosha complex activity. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2016;35:45. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0319-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KH, Choi HR, Won CH. Alteration of the TGF-beta/SMAD pathway in intrinsically and UV-induced skin aging. Mech. Ageing. Dev. 2005;126:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. PNAS. 2008;105:1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka M. Transport of sugars in tumor cell membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1974;355:77–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(74)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell. Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Chan CS, Wu R, Zhang C, Sun Y, Song JS, Tang LH, Levine AJ, Feng Z. Negative regulation of tumor suppressor p53 by microRNA miR-504. Mol. cell. 2010;38:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Klein JD, Mitch WE, Zhang L, Martinez I, Wang XH. MicroRNA-29 induces cellular senescence in aging muscle through multiple signaling pathways. Aging. 2014;6:160–175. doi: 10.18632/aging.100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MP, Ismail N, Zhang X. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. Plos ONE. 2008;3:e3694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvágner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Bálint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;93:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafferany M, Huynh TV, Silverman MA, Zaidi Z. Geriatric dermatoses: a clinical review of skin diseases in an aging population. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012;51:509–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JJ, Liu CM, Zhang BY. MicroRNA-26a supports mammalian axon regeneration in vivo by suppressing GSK3β expression. Cell. Death. Dis. 2015;6: e1865. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnin M. Recent progress in studies of miRNA and skin diseases. J. Dermatol. 2015;42:551–558. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RJ, Hobert O. A microRNA controlling left/right neuronal asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;426:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature02255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolina DS, Tavintharan S, Armugam A, Sepramaniam S, Pek SL, Wong MT, Lim SC, Sum CF, Jeyaseelan K. Circulating miRNA profiles in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:2271–2276. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SK, Petillo D, Kang UJ. Plasma-based circulating MicroRNA biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2012;2:321–331. doi: 10.3233/JPD-012144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraytsberg Y, Kudryavtseva E, McKee AC, Geula C, Kowall NW, Khrapko K. Mitochondrial DNA deletions are abundant and cause functional impairment in aged human substantia nigra neurons. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:518–520. doi: 10.1038/ng1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Dezso Z, MacKenzie C. Circulating miRNA biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Plos ONE. 2013;8:e69807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Reddy PH. Are circulating microRNAs peripheral biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1862:1617–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Stolarska M, Alivernini S, Ballantine LE. MicroRNA-155 as a proinflammatory regulator in clinical and experimental arthritis. PNAS. 2011;108:11193–11198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019536108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A, Grether-Beck S, Singh M. MicroRNA-15b regulates mitochondrial ROS production and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype through sirtuin 4/SIRT4. Aging. 2016;8:484–509. doi: 10.18632/aging.100905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer BI, Mantha K, Kleiber ML, Diehl EJ, Addison SM, Singh SM. Long-lasting alterations to DNA methylation and ncRNAs could underlie the effects of fetal alcohol exposure in mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013;6:977–992. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, The C, Shyh-Chang N. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes. Dev. 2009;23:862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann SM, Krüger C, Park B. An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates Toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:827–835. doi: 10.1038/nn.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidinger P, Backes C, Deutscher S, Schmitt K, Mueller SC, Frese K, Haas J, Ruprecht K, Paul F, Stähler C, Lang CJ, Meder B, Bartfai T, Meese E, Keller A. A blood based 12-miRNA signature of Alzheimer disease patients. Genome Biol. 2013;14: R78. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-r78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Luna C, Qiu J, Epstein DL, Gonzalez P. Alterations in microRNA expression in stress-induced cellular senescence. Mech. Ageing. Dev. 2009;130:731–741. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lei H, Xu Y, Tao ZZ. miR-512-5p suppresses tumor growth by targeting hTERT in telomerase positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Plos ONE. 2015;10:e0135265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Bates DJ, An J, Terry DA, Wang E. Up-regulation of key microRNAs, and inverse down-regulation of their predicted oxidative phosphorylation target genes, during aging in mouse brain. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:944–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Khanna A, Li N, Wang E. Circulatory miR34a as an RNA based, noninvasive biomarker for brain aging. Aging. 2011;3:985–1002. doi: 10.18632/aging.100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]