Abstract

Background

Postural instability is one of most disabling motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Indices of multi-muscle synergies are new measurements of postural stability.

Objectives

We explored the effects of dopamine-replacement drugs on multi-muscle synergies stabilizing center of pressure coordinate and their adjustments prior to a self-triggered perturbation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. We hypothesized that both synergy indices and synergy adjustments would be improved on dopaminergic drugs.

Methods

Patients at Hoehn-Yahr stages II and III performed whole-body tasks both off- and on-drugs while standing. Muscle modes were identified as factors in the muscle activation space. Synergy indices stabilizing center of pressure in the anterior-posterior direction were quantified in the muscle mode space during a load-release task.

Results

Dopamine-replacement drugs led to more consistent organization of muscles in stable groups (muscle modes). On-drugs patients showed larger indices of synergies and anticipatory synergy adjustments. In contrast, no medication effects were seen on anticipatory postural adjustments or other performance indices.

Conclusions

Dopamine-replacement drugs lead to significant changes in characteristics of multi-muscle synergies in Parkinson’s disease. Studies of synergies may provide a biomarker sensitive to problems with postural stability and agility and to efficacy of dopamine-replacement therapy.

Keywords: Posture, Parkinson’s disease, synergy, muscle mode, anticipatory synergy adjustments, dopaminergic medication

Introduction

Postural instability represents one of the important features of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which is also a major source of disability in PD as the disease advances. The emergence of postural instability signifies a major landmark of progression from stage-II to stage-III according to the Hoehn and Yahr (HY, [Hoehn and Yahr 1967]) staging for PD. Clinical assessment of postural instability in PD typically is subjective [Ozinga et al. 2015], e.g. based on observations of patient’s reaction during the shoulder pull-test and reports of the incidence of falls. Recently, we have shown that the measurement of impaired stability control may be used as an early biomarker of PD, sensitive in detecting the problems with postural stability even in HY stage II PD patients (reviewed in [Latash and Huang 2015]).

In earlier studies, we analyzed synergies defined as neural organizations of large sets of effectors, e.g., digits, joint, or muscles, providing the stability of important performance variables [Latash et al. 2007; Latash 2012]. These studies used an index of multi-muscle synergies computed within the framework of the uncontrolled manifold (UCM) hypothesis (Scholz and Schöner 1999) and representing the relative amount of inter-trial variance that had no effect on shifts of the center of pressure (COP) in the total amount of this variance (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003). Quantitative analysis of such task-specific synergies has shown that during steady-state action synergies are typically strong while they show a drop in the synergy index when a person prepares to perform a quick action. These anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs, [Olafsdottir et al. 2005; Shim et al. 2005]) are seen 200–300 ms prior to the action initiation; ASAs represent an important reflection of controlled stability that allows combining stability during steady state and agility in transition to a quick action [Latash and Huang 2015]. Recent studies have shown that the synergy index during steady-state performance is lower and ASAs are reduced and delayed in PD subjects [Park et al. 2012; Jo et al. 2015], in particular in postural tasks [Falaki et al. 2016].

In this study, we explored whether indices of synergies in PD patients performing a postural task are sensitive to dopamine-replacement medication. Based on an earlier study [Park et al. 2014], we expected that dopamine-replacement therapy would lead to higher synergy indices (increased stability) during quiet standing (Hypothesis 1) and larger ASAs (increased agility) in preparation to the self-imposed perturbation (Hypothesis 2). The confirmation of these hypotheses would underscore the importance of the basal ganglia in synergic control, and the potential utility of synergy indices for clinical research and practice.

Methods

Subjects

A group of 6 HY stage II and 4 HY stage III (4 females) PD patients (aged 69.4 ± 6.3 years, mean ± standard deviation, SD) participated in this study. No healthy controls were tested because this comparison had been performed in an earlier study [10]. Table 1 presents general information about the subjects. All subjects were diagnosed by an experienced clinician. All subjects gave written informed consent approved by the Hershey Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Description of PD participants.

| Patient, HY | Gender, M/F | Age, years | Symptom Onset, R/L | Years since diagnosis | UPDRS Off-drug | UPDRS On-drug | Axial motor sub-score Off-drug | Axial motor sub-score On-drug | Mass kg | Height cm | LEDD mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, III | M | 63.0 | L | 11.7 | 21 | 13 | 14 | 5 | 84 | 175 | 667 |

| 2, II | M | 64.1 | R | 8.6 | 46 | 30 | 13 | 7 | 96 | 178 | 635 |

| 3, II | M | 70.7 | Bilateral | 1.5 | 19 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 76 | 177 | 250 |

| 4, II | F | 64.2 | R | 12.2 | 16 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 55 | 162 | 550 |

| 5, III | M | 69.9 | Bilateral | 1.1 | 37 | 33 | 10 | 9 | 81 | 169 | 500 |

| 6, II | F | 67.1 | L | 3.3 | 27 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 72 | 153 | 750 |

| 7, II | F | 72.8 | R | 4.8 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 74 | 153 | 480 |

| 8, II | F | 66.8 | R | 4.8 | 38 | 25 | 9 | 9 | 98 | 156 | 700 |

| 9, III | M | 74.6 | L | 8.6 | 31 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 61 | 163 | 650 |

| 10, III | M | 79.1 | R | 2.3 | 29 | 25 | 14 | 13 | 100 | 180 | 600 |

HY: Hoehn and Yahr stage, M/F: male/females, R/L: right/left, LEDD: levodopa equivalent daily dose, UPDRS: Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III – motor scores (UPDRS-III), levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was estimated based on [Tomlinson et al. 2010].

Apparatus

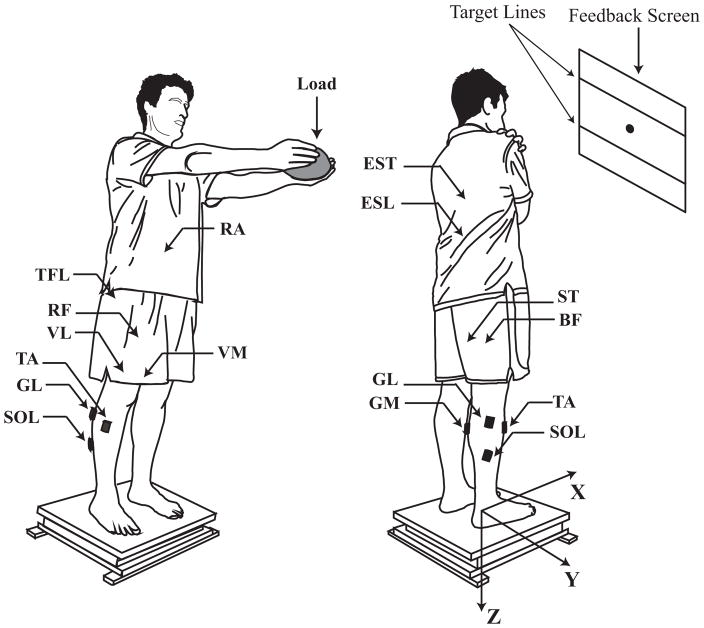

Subjects stood on a force platform (OPTIMA, Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., MA, USA), which recorded components of the forces applied to the surface of the platform along the anterior-posterior direction (FX) and the vertical direction (FZ), and the moment of force around the Y-axis (MY). The orthogonal X, Y, Z axes refer to the platform coordinate system. Time-varying X- and Y-coordinates of the point of application of the ground reaction force were considered as the COP coordinates. A 23″ monitor mounted at eye level 1.5 m from the subject was used for visual feedback of the COP coordinate in the XY plane, in the anterior-posterior direction (COPAP), and in the medial-lateral direction (COPML). All subjects wore a safety harness. Figure 1 demonstrates the experimental setup.

Figure 1.

The experimental setup. Left: posture of participants in the load release (LR) task with fully extended arms holding the load. Right: posture of participants with arms across the chest in quiet standing (QS), voluntary sway (VS), and fast body motion (FBM) tasks. The dot on the screen is the position of the COP shown to the participant. Visual feedback was not given during the QS task. X, Y, and Z axes represent the orthogonal coordinate system of the force platform. Locations of the electrodes are shown with arrows and black rectangles. TA: tibialis anterior; SOL: soleus; GM: gastrocnemius medialis; GL: gastrocnemius lateralis; BF: biceps femoris; ST: semitendinosus; RF: rectus femoris; VL: vastus lateralis; VM: vastus medialis; TFL: tensor fasciae latae; ESL: lumbar erector spinae; EST: thoracic erector spinae; RA: rectus abdominis. The safety harness always was used (not drawn).

A 16-channel Trigno Wireless System (Delsys Inc., MA, USA) was used to record surface muscle activity (electromyogram, EMG). Using adhesive sensor interfaces, active electrodes (37 × 26 × 15 mm, 14 g) with built-in pre-amplifiers on the recording heads (by a factor of 909) were placed over the bellies of the following right-side muscles: tibialis anterior (TA), soleus (SOL), gastrocnemius medialis (GM), gastrocnemius lateralis (GL), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus medialis (VM), tensor fasciae latae (TFL), lumbar erector spinae (ESL), thoracic erector spinae (EST), and rectus abdominis (RA). Sensors were placed according to published guidelines (Criswell and Cram, 2011) and subsequently confirmed by observing EMG patterns of related isometric contractions and free movements. Trigno EMG parallel-bar sensors utilize four bar contacts (99.9% silver, 5×1 mm, fixed contacts distance: 10 mm parallel to muscle fibers) to ensure effective detection of the signal from the muscle below the skin with minimal crosstalk. Prior to affixing EMG sensors, the skin at the sensor site was properly wiped with isopropyl alcohol swabs to remove oils and dry dermis. Trigno EMG sensors provide the following specifications: common mode rejection noise > 80 db; EMG baseline noise < 750 nV RMS; and ±5 V analog output range. EMG signals and force platform data were sampled at 1 KHz with a 16-bit resolution (PCI-6225, National Instruments Co., TX, USA) using customized LabVIEW-based software (LabVIEW 2013, National Instruments Co., TX, USA).

Procedures

PD patients were tested twice: early in the morning prior to taking their first medication following an overnight withdrawal (off-drug condition) and one hour after taking their medication (on-drug condition). Participants stood barefoot on the force platform with their feet parallel and shoulder width apart (Fig. 1). The foot position was marked on the surface of the platform and reproduced across all trials. There were four tasks: 1) quiet standing (QS), 2) voluntary sway (VS), 3) load release (LR), and 4) fast-body motion (FBM). Tasks always were performed in this order: QS, VS, and block randomized LR and FBM.

QS task

This task was performed to measure the baseline muscle activity, which was used for further EMG normalization. Participants stood quietly on the force platform and tried to avoid body movements for 30 s without visual feedback on COP coordinates. The arms were held across the chest. During the other tasks visual feedback on both COP coordinates was provided on the screen.

VS task

The purpose of this task was to define a low-dimensional set of elemental variables (M-modes, muscle groups with parallel changes in activation levels [Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003a]) and to link small changes in M-modes to COPAP shifts (the Jacobian, J [Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003b; Danna-Dos-Santos et al. 2007]). Participants performed continuous voluntary body sway in the anterior-posterior direction shifting COPAP between two targets shown on the screen over 6 cm at 0.5 Hz paced by a metronome. Two 30-s trials were performed providing an adequate number of data-points to define the M-modes and J.

LR task

Participants fully extended their arms and held a brick-shaped load (20 cm long; 2 kg for males and 1.5 kg for females) by pressing on its sides with the palms. With the load, participants were asked to lean forward about the ankle joints to a new COPAP position shifted forward by 3 cm, hold this position for ~2–3 s, and then release the load in a self-paced manner with a quick, low-amplitude bilateral shoulder abduction movement (as in [Aruin and Latash 1995]). The task included 24 trials to generate enough data for variance analysis. Participants were provided with rest intervals (2–3-min after each 12 trials), snacks, and drinks as needed.

FBM task

The purpose of this task was to compare the ability to make fast whole-body actions off- and on-drug. Each trial began with standing quietly in the initial position. Subjects then were asked to reach the posterior target shown on the screen (3 cm away from the natural COPAP position), keep this position for about 2 s, and perform, in a self-paced manner, a discrete body motion forward to a target located 6 cm anterior as fast as they could. Participants were asked to perform movements about ankle joints, while keeping full contact of their feet with the platform, and pay attention mainly to the speed of the forward motion rather than to its accuracy. Seven trials were performed to compare changes in characteristics of the COP trajectories between the on-drug and off-drug conditions.

Prior to data collection, participants went through a familiarization session during which the following number of practice trials were performed for each task: two trials prior to the VS task; four trials prior to the LR task; and four trials prior to the FBM task. During the on-drug testing, participants performed only one practice trial prior to the LR and FBM tasks.

Data Processing

Recorded signals were processed offline using a customized MATLAB program (R2013a, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Force platform signals were low-pass filtered at 10 Hz with a fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter. The filtered data were used to compute time-varying COPAP [Winter et al. 1996]. To avoid edge effects for VS trials (the action during its initiation and close to its termination), only the data within the interval {3 s; 28 s} were used. On average, each subject performed 10 full cycles within this interval. Trials without major errors were accepted; the number of those trials was 16 ± 2 and 16 ± 1 for LR, 6 ± 2 and 6 ±1 for FBM, for the off-drug and on-drug conditions, respectively.

Basic EMG analysis

Raw EMG signals were first band-pass filtered (20–350 Hz) using a fourth-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter, full-wave rectified and low-pass filtered by applying a moving average 100-ms window. To account for the electro-mechanical delay [Corcos et al. 1992], EMG data were shifted 50 ms backward with respect to the force platform data for computations involving both EMG and mechanical signals. EMG signals were corrected for baseline values by subtracting the average muscle activation levels measured within the QS task in the time interval from 2 to 8 s, and normalized (EMGNORM) by the peak value (EMGPEAK) of the corresponding muscle activation level observed across VS trials:

Initiation of anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs [Belenkiy et al. 1967; Massion 1992]) in the LR task was defined using the time when the averaged across trials muscle activation level within a series performed by a subject exceeded ±2 SD from its respective mean activity (computed over the time interval {T0-1000 ms; T0-300 ms}). Dorsal muscles showed clear APAs in all participants; hence, the time when the earliest APA happened across those muscles was selected as tAPA. The identified tAPA values were further confirmed visually to avoid false starts due to spontaneous transient EMG changes, including possible episodes of co-contraction.

Defining muscle modes

Principal component analysis (PCA) with factor extraction [Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003b; Danna-Dos-Santos et al. 2007] after Varimax rotation was applied to the correlation matrix of the IEMGNORM data from the VS task integrated over 50-ms time windows. Based on the Kaiser criterion, four PCs were accepted as M-modes [Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003a], confirmed by visual inspection of the scree plot.

Defining the Jacobian matrix

The J matrix links small changes in the M-mode magnitudes (ΔM) to COPAP shifts (ΔCOPAP). For each subject, J matrix was formed by the coefficients of the multiple regression analysis without intercept:

Analysis of variance within the uncontrolled manifold hypothesis

Within the uncontrolled manifold (UCM) hypothesis [Scholz and Schöner 1999; Latash et al. 2007], synergies were analyzed according to previously published methods [Klous et al. 2011]. Inter-trial variance in the M-mode space that did not affect COPAP (VUCM) and variance that did (variance in orthogonal directions, VORT) was computed per degree of freedom in each space. For computational details see [Klous et al. 2011; Tresch et al. 2006]. VUCM > VORT indicates a synergy stabilizing COPAP (reviewed in [Latash et al. 2007]). An index of synergy was calculated: ΔV = (VUCM−VORT)/VTOT, where VTOT is total variance and all variance indices are computed per dimension. For further statistical analysis, ΔV was log-transformed using a modified Fisher’s z-transform, resulting in ΔVZ [Solnik et al. 2013].

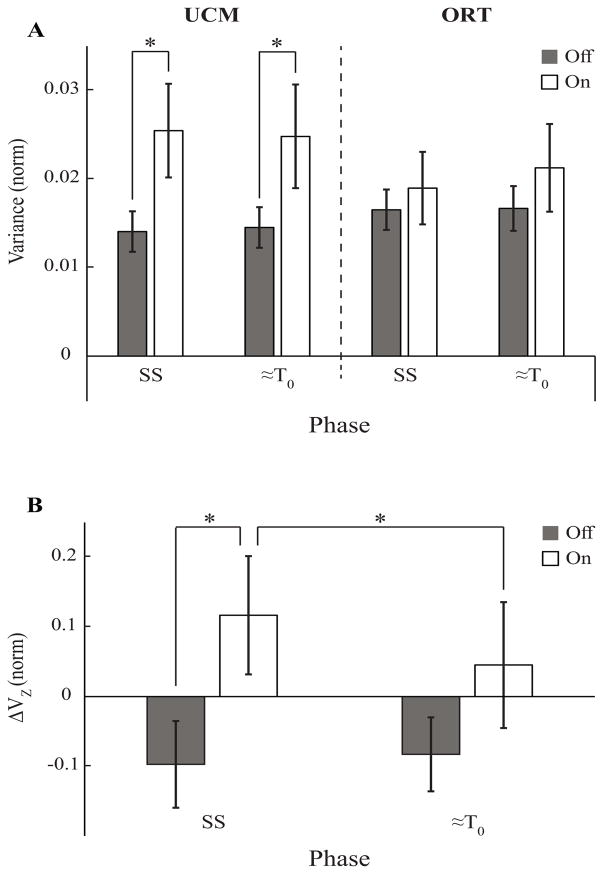

To quantify anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs), the synergy index was averaged within two time intervals during the LR task. The first was a 200-ms steady state (SS, Fig. 2A) from (T0-1000) ms to (T0-800) ms, whereas the second was a 50-ms time interval about T0 (≈T0, Fig. 2A). ASA was quantified as the amount of ΔVZ drop in preparation to the movement, ΔΔVZ.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SE values of two inter-trial variance components (VUCM and VORT, A) and z-transformed synergy indices (ΔVZ, B) averaged across patients for the Off-drug and On-drug conditions (black and white bars, respectively) during the SS (steady state) and ≈T0 (movement initiation) time intervals. SS and ≈T0 are the two time intervals selected for statistical analysis. Stars show statistically significant differences.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± standard errors (SE) with median and inter-quartiles (IQR) values. We used Wilcoxon signed-rank test and two-way and three-way ANOVAs with repeated measures, factors Variance (VUCM and VORT), Phase (SS and ≈T0), and Condition (off-drug and on-drug) to analyze effects of medication on the main outcome variables across phases. For all analyses, the data were checked for sphericity and normality violations; Geenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were used to explore significant effects at p<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of COP displacements and EMG patterns

Both the average rate of COPAP shift, (dCOP/dt)AV and the maximum rate of COPAP shift, (dCOP/dt)MAX during the fast body motion task were significantly smaller in the off-drug condition than in the on-drug condition: 15.0±1.05 (median: 14.6; IQR: 13.1, 17.1) cm/s vs. 18.0±1.22 (median: 17.2; IQR: 15.7, 19.1) cm/s, p<0.005; and 34.8±2.68 (median: 31.1; IQR: 28.9, 38.5) cm/s vs. 40.0±2.89 (median: 37.9; IQR: 33.5, 45.1) cm/s, p<0.01, respectively.

In the load release (LR) task, consistent changes in the EMG signals prior to the load release time (T0) were seen in all subjects, starting as early as 150 ms prior to T0. This early modulation, anticipatory postural adjustment (APA), was observed most commonly in GM, BF, ST, EST, and ESL. On average, there was only a small, non-significant difference in tAPA between the two medication conditions (off-drug −135.5±15.15 (median: −132.5; IQR: −178.5, −107.5) ms vs. on-drug: −156.1±14.18 (median: −179.5; IQR: −193.5, −110.5) ms).

Defining M-modes and Jacobian

The PCA with rotation and factor extraction on IEMGNORM in the VS task allowed identifying the first four M-modes, which accounted for 68.6±2.2% (median: 68.7; IQR: 65.5, 72.9) of the total variance in the off-drug condition, and 74.7±2.4% (median: 74.8; IQR: 68.2, 80.7) in the on-drug condition (p<0.01; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

For each participant and medication condition, multiple linear regression analysis was used to identify how shifts of COPAP (ΔCOPAP) were related to small M-mode magnitude changes (ΔM, see ‘Methods’). In both medication conditions, all ΔM values were significant predictors of ΔCOPAP (p < 0.001). Adjusted R2 values were 0.62±0.04 (median: 0.61; IQR: 0.53, 0.69) and 0.66±0.04 (median: 0.67; IQR: 0.6, 0.73) in the off-drug and on-drug conditions, respectively (p < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Analysis of M-mode variance

EMG data from the LR trials were used to quantify across-trial variance in two M-mode subspaces, VUCM (variance leading to unchanged COPAP) and VORT (variance leading to COPAP shifts). When subjects were standing quietly (steady state), VUCM was nearly two-fold higher in the on-drug condition compared to the off-drug condition (Fig. 2A), whereas there were no major differences between the VORT magnitudes (Fig. 2A).

By the time of load release (T0), there was a small drop in VUCM and a small increase in VORT in the on-drug condition, without consistent difference in either index in the off-drug condition. ANOVA on VUCM and VORT showed a significant Condition × Phase × Variance interaction [F(1,18)=5.74, p<0.05] with no other significant effects. The interaction reflected counter-directional changes in the two variance components between the two phases confirmed by a two-way ANOVA showing a significant ΔVariance × Condition interaction [F(1,18)=5.74, p<0.05]. Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test confirmed that VUCM was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in the on-drug condition compared to the off-drug condition during both SS (median: 0.02; IQR: 0.0145, 0.037 vs. median: 0.0107; IQR: 0.0096, 0.0193) and ≈T0 phases (median: 0.0188; IQR: 0.0153, 0.031 vs. median: 0.0137; IQR: 0.0094, 0.0178).

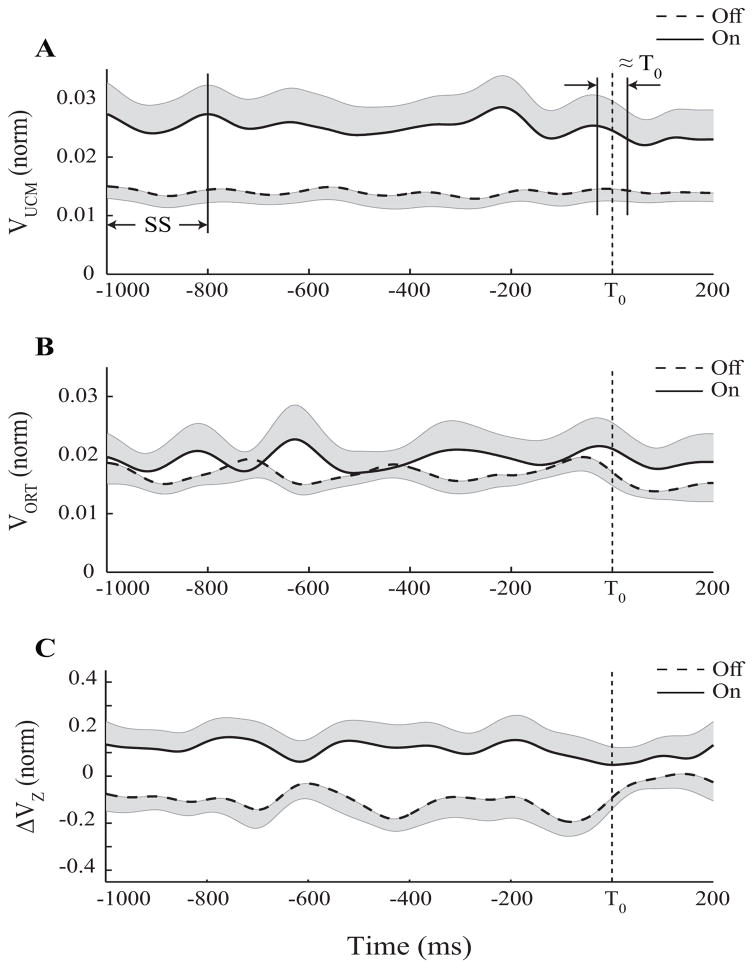

Time profiles of the synergy index, ΔVZ with standard error shades are presented in Figure 3C; ΔVZ during steady state was significantly lower in the off-drug condition compared to the on-drug condition (median: −0.124; IQR: −0.264, 0.069 vs. median: 0.104; IQR: 0.038, 0.239; p < 0.01, Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test). Nine out of 10 subjects showed a >40% increase in the magnitude of the synergy index from the off-drug condition to the on-drug condition. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant Condition × Phase interaction [F(1,18)=5.47, p<0.05] reflecting a significant drop in ΔVZ from SS to ≈T0 (median: 0.04; IQR: −0.076, 0.168; F(1,9)=7.63, p<0.05), i.e. ASAs, on-drug only (Figure 2B). There was a small increase in ΔVZ from SS to ≈T0 in the off-drug condition by 0.014±0.026 (median: 0.037; IQR: −0.042, 0.077), whereas on-drug ΔVZ decreased by 0.071±0.026 (median: 0.093; IQR: 0.063, 0.126; p<0.05, Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test).

Figure 3.

Time profiles of the two inter-trial variance components VUCM (A) and VORT (B), and z-transformed synergy index (ΔVZ, C) during the load-release (LR) task, averaged across patients for the Off-drug (dashed line) and On-drug (solid line) conditions. The vertical dashed lines mark the load release moment. SS (steady state) and ≈T0 (movement initiation) are the two time intervals selected for statistical analysis.

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that dopamine-replacement medication would result in: (1) higher synergy indices during the quiet standing (higher stability); and 2) larger anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs) in preparation to a self-triggered perturbation (higher agility). Both hypotheses have been confirmed in the experiment. The latter effect may be related to the improved performance in the fast-sway task. We observed larger changes in the component of variance (VUCM) that had no effect on the center of pressure coordinate. This result is important, as it suggests that medication led to more flexible behavior in the patients and increased variability at the level of M-modes without negative impact on precision of performance with respect to COPAP. In addition, we observed significant medication effects on the ability of patients to unite muscles into stable groups (muscle modes, M-modes). Our results, together with the results of an earlier study, which documented synergy index and ASA differences between PD patients and healthy controls [Falaki et al. 2016], point at several critical actions of dopamine replacement medications related to synergic control of muscles in postural tasks.

Drug effects on synergies in PD

The term ‘synergy’ has at least three different meanings in movement science. In the clinical literature, this word commonly implies stereotypical patterns of muscle activation that interfere with purposeful actions after stroke [Bobath 1978; DeWald et al. 1995]. Another commonly used meaning is a number of performance variables, kinetic, kinematic, or electromyographic, that show parallel changes with task parameters or over time [d’Avella et al. 2003; Krishnamoorthy et al. 2003a; Ivanenko et al. 2004; Ting and Macpherson 2005]; e.g., M-modes in our study. We define synergies as neurophysiological mechanisms providing for stability of salient performance variables (reviewed in [Latash et al. 2007]).

In our study, we used PCA with rotation and factor extraction to identify a set of orthogonal M-modes, which is a major advantage for inter-trial variance analysis of multi-M-mode synergies stabilizing the COPAP coordinate (cf. [Tresch et al. 2006]). If subjects use a consistent set of M-modes over the performance of the cyclical sway task, the amount of variance accounted for by a set of M-modes is expected to be relatively high. If the subjects switch the way muscles are organized into M-modes during the cyclical sway task, the index is expected to drop. The amount of variance in the muscle activation space accounted for by four M-modes was significantly higher in the on-drug condition. This observation suggests that the drug helped the participants to be more consistent in using the same M-modes throughout the cycle.

Recently, we have documented a drop in the index of M-mode synergies in PD, which was seen even in HY stage-II patients [Falaki et al. 2016]. In the current study, these synergy index values, on average, were negative or close to zero in patients off-drug. PD patients, however, showed positive synergy index values while on-drug. This may be interpreted as a complete loss in the ability to organize M-modes into COPAP stabilizing synergies in our patient group, which is partly recovered with the help of medications.

We would like to emphasize that the medication did not lead to significant changes in VORT, a component of variance affecting COPAP. The other component of variance, VUCM, which did not affect COPAP, increased nearly two-fold in the on-drug condition. In more intuitive terms, the subjects became more variable (less stereotypical) without becoming less accurate.

Feed-forward control of postural tasks in PD

PD is known to affect feed-forward adjustments across motor tasks. In particular, PD has been reported to lead to delayed and reduced anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) during postural tasks [Bazalgette et al. 1986; Dick et al. 1986; Latash et al. 1995]. In our experiment, we quantified only the timing of APAs and found no significant medication effects on this index. These results are consistent with earlier observations of minor or lacking effects of dopamine-replacement drugs on APAs (e.g., de Kam et al. 2014).

Another aspect of feed-forward control, anticipatory synergy adjustments (ASAs; [Olafsdottir et al. 2005; Shim et al. 2005]) represent gradual attenuation of a synergy stabilizing a salient performance variable in preparation to an action involving a quick change of that variable. ASAs are functionally important and their impairment potentially can lead to difficulties with movement initiation [Latash and Huang 2015]. In contrast to the unchanged APAs, ASAs were significantly smaller in the off-drug condition compared to on-drug. This could be related to the improved performance of participants in the fast-sway task on-drug. Our observations suggest that feed-forward control of the stability of multi-muscle actions may be improved by medications without necessarily affecting the net mechanical effects of APAs.

One of the drawbacks of the current study is the relatively small sample of PD patients. Whereas we obtained statistically significant effects, it is possible that testing a larger group would also reveal differences between HY stage-II and stage-III patients. Future studies with larger sample sizes and with levodopa-challenge (suboptimal dosages of medication) are warranted to provide a better understanding of the clinical and neurobiological implications of synergy measurements.

Concluding comments

To conclude, our study has shown that dopamine-replacement drugs lead to higher indices of multi-muscle synergies and higher ASA indices in PD. These results underscore the importance of the basal ganglia circuitry for both stability of multi-muscle action and agility of behavior.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the study. XH and MML were supported by NIH grants NS060722, ES019672, and NS082151 during the past 12 months. MML also has an internal grant from Penn State University but received no salary support as part of the award. MLL and AF were supported by NIH grants NS035032 and AR048563. This publication was also supported, in part, by Grants UL1 TR000127 and TL1 TR000125 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Biographies

Ali Falaki

Mr. Falaki is a doctoral student in Kinesiology and in Clinical and Translational Sciences at the Pennsylvania State University. He earned a Master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Amirkabir University of Technology in Tehran, Iran. His research is focused on the multi-muscle control of whole-body movements, including postural tasks, and to changes in the control of multi-muscle systems in neurological disorders including Parkinson’s disease.

Mechelle Lewis

Dr. Lewis has a broad background in neurobiology, with specific training in key research areas [Parkinson’s disease (PD), experimental design, and translational research]. She has a keen interest in both normal and dysfunctional brain processes, as well as the development of tools and markers to help us better understand brain function. Dr. Lewis collaborates on several NIH-funded research projects, particularly those focused on the development of brain imaging measures that can diagnose and monitor PD disease and its progression, as well as those that may assist in assessing measurements in prodromal populations. She has extensive experience in coordinating multi-disciplined, collaborative projects and serves as the central liaison on all projects ongoing in the lab.

Mark L. Latash

Mark Latash is Distinguished Professor of Kinesiology and Director of the Motor Control Laboratory at the Pennsylvania State University. His research is focused on the control and coordination of human voluntary movements and movement disorders. He is the author of “Control of Human Movement” (1993), “The Neurophysiological Basis of Movement” (1998, 2008), “Synergy” (2008), “Fundamentals of Motor Control” (2012), and “Biomechanics and Motor Control: Defining Central Concepts” (with Vladimir Zatsiorsky, 2016). In addition, he edited nine books and published over 350 papers in refereed journals. Mark Latash served as the Founding Editor of the journal “Motor Control” (1996–2007), as President of the International Society of Motor Control (2001–2005) and as Director of the annual Motor Control Summer School series since 2004. He is a recipient of the Bernstein Prize in motor control.

Xuemei Huang

Dr. Huang is a board-certified research neurologist whose clinical practice and scholarly concentrations are focused on neurodegenerative disorders. Because of her background and training, she has a strong interest in translational neuroscience. Dr. Huang has been NIH funded since 2003, just after she began the first faculty position. Her major focus is the use of novel imaging modalities and designs to elucidate neurocircuitry (particularly basal ganglia and cerebellum) underlying various signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD), and the development of MRI biomarkers for early detection and progression of PD and related disorders. The other area of research in Dr. Huang’s group is the interactive role of genetic and environmental factors in the etiology of PD and related disorders. Her clinical strength is the application of sophisticated pharmacological approaches to the treatment of movement disorders, and this, is turn, interacts with her research foci.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aruin AS, Latash ML. The role of motor action in anticipatory postural adjustments studied with self-induced and externally-triggered perturbations. Experimental Brain Research. 1995;106:291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00241125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazalgette D, Zattara M, Bathien N, Bouisset S, Rondot P. Postural adjustments associated with rapid voluntary arm movements in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Advances in Neurology. 1986;45:371–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenkiy VY, Gurfinkel VS, Paltsev YI. Elements of control of voluntary movements. Biofizika. 1967;10:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobath B. Adult Hemiplegia: Evaluation and Treatment. William Heinemann; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Corcos DM, Gottlieb GL, Latash ML, Almeida GL, Agarwal GC. Electromechanical delay: An experimental artifact. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 1992;2:59–68. doi: 10.1016/1050-6411(92)90017-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criswell E, Cram JR. Cram’s introduction to surface electromyography. 2. Jones and Bartlett; Sudbury, MA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Danna-Dos-Santos A, Slomka K, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Muscle modes and synergies during voluntary body sway. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;179:533–550. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Saltiel P, Bizzi E. Combinations of muscle synergies in the construction of a natural motor behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:300–308. doi: 10.1038/nn1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kam D, Nonnekes J, Oude Nijhuis LB, Geurts AC, Bloem BR, Weerdesteyn V. Dopaminergic medication does not improve stepping responses following backward and forward balance perturbations in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology. 261:2330–2337. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWald JP, Pope PS, Given JD, Buchanan TS, Rymer WZ. Abnormal muscle coactivation patterns during isometric torque generation at the elbow and shoulder in hemiparetic subjects. Brain. 1995;118:495–510. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick JPR, Rothwell JC, Berardelli A, Thompson PD, Gioux M, Benecke R, Day BL, Marsden CD. Associated postural adjustments in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1986;49:1378–1385. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.12.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falaki A, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML. Impaired synergic control of posture in Parkinson’s patients without postural instability. Gait and Posture. 2016;44:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn M, Yahr M. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko YP, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F. Five basic muscle activation patterns account for muscle activity during human locomotion. Journal of Physiology. 2004;556:267–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Park J, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML. Prehension synergies and hand function in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Brain Research. 2015;233:425–440. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4130-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klous M, Mikulic P, Latash ML. Two aspects of feed-forward postural control: Anticipatory postural adjustments and anticipatory synergy adjustments. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:2275–2288. doi: 10.1152/jn.00665.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy V, Goodman SR, Latash ML, Zatsiorsky VM. Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons: Identification of muscle modes. Biological Cybernetics. 2003a;89:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s00422-003-0419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy V, Latash ML, Scholz JP, Zatsiorsky VM. Muscle synergies during shifts of the center of pressure by standing persons. Experimental Brain Research. 2003b;152:281–292. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML. The bliss (not the problem) of motor abundance (not redundancy) Experimental Brain Research. 2012;217:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3000-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Aruin AS, Neyman I, Nicholas JJ. Anticipatory postural adjustments during self-inflicted and predictable perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1995;58:326–334. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Huang X. Neural control of movement stability: Lessons from studies of neurological patients. Neuroscience. 2015;301:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schöner G. Toward a new theory of motor synergies. Motor Control. 2007;11:276–308. doi: 10.1123/mcj.11.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion J. (1992) Movement, posture and equilibrium – interaction and coordination. Progress in Neurobiology. 1992;38:35–56. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90034-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir H, Yoshida N, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Anticipatory covariation of finger forces during self-paced and reaction time force production. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;381:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozinga SJ, Machado AG, Miller Koop M, Rosenfeldt AB, Alberts JL. Objective assessment of postural stability in Parkinson’s disease using mobile technology. Movement Disorders. 2015;30:1214–1221. doi: 10.1002/mds.26214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML. Dopaminergic modulation of motor coordination in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2014;20:64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Wu Y-H, Lewis MM, Huang X, Latash ML. Changes in multi-finger interaction and coordination in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2012;108:915–924. doi: 10.1152/jn.00043.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schöner G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: Identifying control variables for a functional task. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;126:289–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK, Olafsdottir H, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. The emergence and disappearance of multi-digit synergies during force production tasks. Experimental Brain Research. 2005;164:260–270. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnik S, Pazin N, Coelho C, Rosenbaum DA, Scholz JP, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. End-state comfort and joint configuration variance during reaching. Experimental Brain Research. 2013;225:431–442. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting LH, Macpherson JM. A limited set of muscle synergies for force control during a postural task. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2005;93:609–613. doi: 10.1152/jn.00681.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2010;25:2649–53. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Cheung VC, d’Avella A. Matrix factorization algorithms for the identification of muscle synergies: evaluation on simulated and experimental data sets. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95:2199–2212. doi: 10.1152/jn.00222.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA, Prince F, Frank JS, et al. Unified theory regarding A/P and M/L balance in quiet stance. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:2334–2343. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]