Abstract

There are >100,000 patients waiting for kidney transplants in the US, and a vast need worldwide. Xenotransplantation, in the form of the transplantation of kidneys from genetically-engineered pigs, offers the possibility of overcoming the chronic shortage of deceased and living human donors. These genetic manipulations can take the form of (i) knockout of pig genes that are responsible for the expression of antigens against which the primate (human or nonhuman primate) has natural ‘preformed’ antibodies that bind and initiate complement-mediated destruction, or (ii) the insertion of human transgenes that provide protection against the human complement, coagulation, or inflammatory responses. Between 1989 and 2015, pig kidney graft survival in nonhuman primates increased from 23 days to almost 10 months. There appear to be no clinically significant physiological incompatibilities in renal function between pig and primate. The organ-source pigs will be housed in a biosecure environment, and thus the risk of transferring an exogenous potentially pathogenic microorganism will be less than after allotransplantation. Although the risk associated with porcine endogenous retroviruses is considered small, techniques are now available whereby they could potentially be excluded from the pig. The FDA suggests that xenotransplantation should be restricted to “patients with serious or life-threatening diseases for whom adequately safe and effective alternative therapies are not available.” These might include those with (i) a high degree of allosensitization to human leukocyte antigens (HLA) or (ii) rapid recurrence of primary disease in previous allografts. The potential psychosocial, regulatory, and legal aspects of clinical xenotransplantation are briefly discussed.

Keywords: Allosensitization; Clinical trial; Kidney; Pig, genetically-engineered; Xenotransplantation

Introduction

Organ allotransplantation was one of the great medical advances during the latter part of the 20th century. However, the number of organ donors clearly does not keep up with the need. There are currently >100,000 patients waiting for kidney transplants in the US,1 and probably at least an equal number throughout the rest of the world. In the US, although 16,291 kidney transplants from deceased donors took place in 2015, 4,761 patients died while awaiting a kidney.

The benefits of kidney transplantation are well-documented. When compared with hemodialysis, kidney transplantation prolongs survival. In a study from 2005 looking at outcomes following cadaveric renal transplantation, in patients aged 18 to 34 years the expected survival is 6.7 years on hemodialysis, but 18 years after kidney transplantation. In patients aged 35 to 49 years, survival improves from 5.1 years to 11.2 years post-transplantation.2 Transplantation is also cost-effective for society; in the US dialysis costs approximately $39,000 each year versus $16,600 for the first year post-transplantation.3

Xenotransplantation, in the form of the transplantation of kidneys from genetically-engineered pigs, offers the possibility of overcoming the chronic shortage of deceased human donors (Table 1).4 Kidney xenotransplantation has a long history going back >100 years,5 mainly relating to the clinical transplantation of kidneys from nonhuman primates (NHPs). It is only relatively recently that significant progress has been made in the transplantation of pig kidneys in the experimental laboratory. However, the authors and other contributors to the field believe that progress in improving outcomes in preclinical model is encouraging. We estimate that the outcome endpoints defined by the International Xenotransplantation Association for when a clinical trial should be considered will be met in the near future.

Table 1.

Major advantages of kidney xenotransplantation over allotransplantation

| 1. | Unlimited supply of organs, tissues, and cells |

| Will allow transplantation procedures in ‘borderline’ candidates who might otherwise be declined and of retransplantation without the ethical dilemma of deciding which patient should receive a scarce donor organ | |

| 2. | Organs available electively |

| Will avoid the need for chronic dialysis in patients with renal failure | |

| 3. | Avoids the detrimental effects of brain death on donor organs |

| The process of undergoing brain death can cause structural injury of the organs and result in depletion of energy stores, jeopardizing early graft function after transplantation | |

| 4. | Provides exogenous infection-free sources of organs, tissues, and cells |

| 5. | Obviates the ‘cultural’ barriers to deceased human organ donation present in some countries, e.g., Japan |

History of kidney xenotransplantation

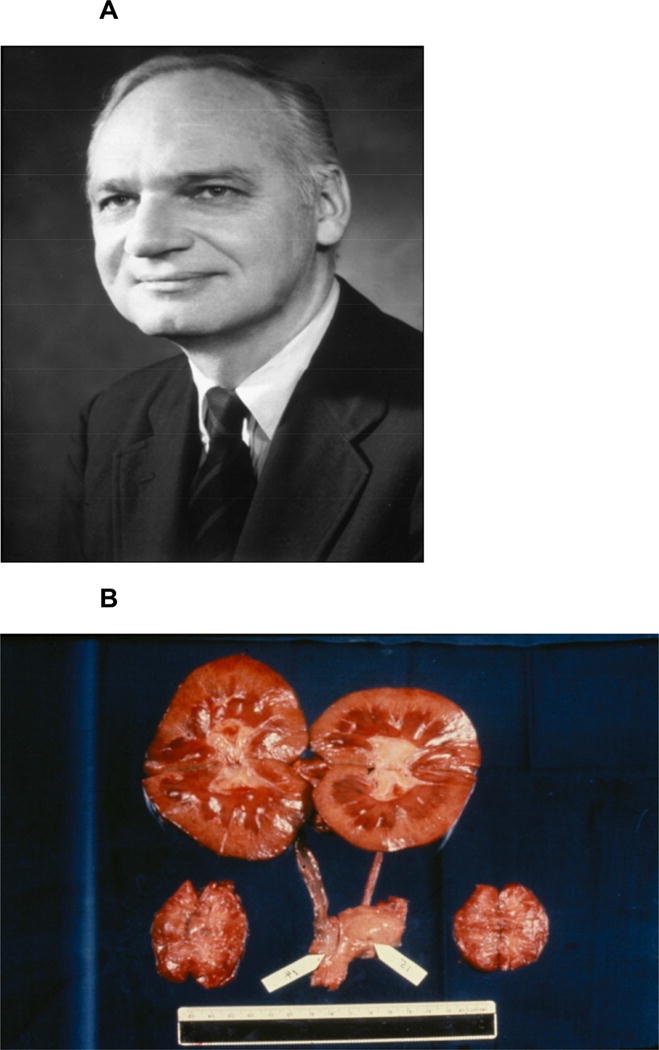

In the 1960s, several attempts were made to provide organs from evolutionary closely-related species. Perhaps the most important of these studies was that by Reemtsma (Figure 1A) and his colleagues who transplanted chimpanzee kidneys into 13 patients, with survival ranging from 11 days to 2 months, except for one patient who returned to work for almost 9 months before suddenly dying from what was believed to be an electrolyte disturbance. At autopsy, the pair of chimpanzee kidneys that had been transplanted appeared macroscopically (Figure 1B) and microscopically normal.

Figure 1.

(A) Keith Reemtsma, who carried out a series of chimpanzee kidney transplants in patients in renal failure the early 1960s. (B) Macroscopic appearances at necropsy of a pair of chimpanzee kidneys transplanted into a patient 9 months previously by Keith Reemtsma.

The majority of deaths in all of these clinical studies were related either to rejection (because of the limited immunosuppressive agents available at the time) or to infection (because of the excessive administration of these agents). Because of the disappointing results, subsequent clinical kidney transplantation efforts were almost exclusively directed to allotransplantation.

However, since human organs remained scarce because of increasing need, researchers turned again to the possibility of xenotransplantation. For a number of reasons, the pig was identified as the most likely potential source of organs for humans. The pig-to-NHP has become the standard experimental model.

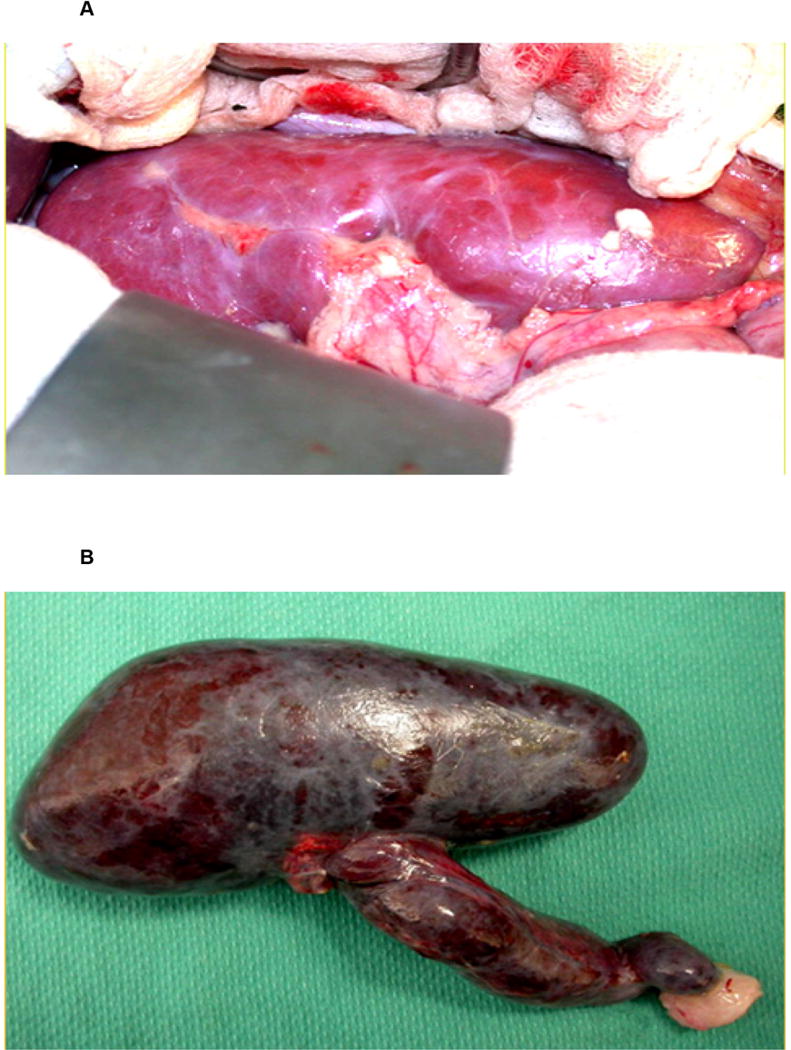

Rejection of a pig organ by a primate is much more vigorous than of an allograft, largely because of the activity of primate natural antibody and the innate immune response (complement, coagulation, innate immune cells, e.g., monocytes, macrophages, NK cells).6 Survival of genetically-unmodified (wild-type) pig kidneys in NHPs generally occurs within minutes (Figure 2), but, after genetically-engineered pigs became available, the results showed gradual improvement until 2015, since when more rapid progress has been made.7, 8

Figure 2.

(A) Macroscopic appearance of a wild-type (genetically-unmodified) pig kidney transplanted into a baboon immediately after graft reperfusion. (B) The same kidney 5 minutes later after it had undergone hyperacute rejection. (Reproduced with permission from6.)

Progress in genetic modification of pigs

A major reason for this progress has been the increasing availability of pigs with genetic modifications that protect the pig tissues from the primate immune response and/or correct molecular incompatibilities between pig and primate.9 These genetic manipulations can take the form of (i) knockout of pig genes that are responsible for the expression of antigens against which the primate (human or NHP) has natural ‘preformed’ antibodies that bind to these antigens and initiate complement- and/or coagulation-mediated destruction, or (ii) the insertion of human transgenes that provide protection against the human complement, coagulation, or inflammatory responses.9

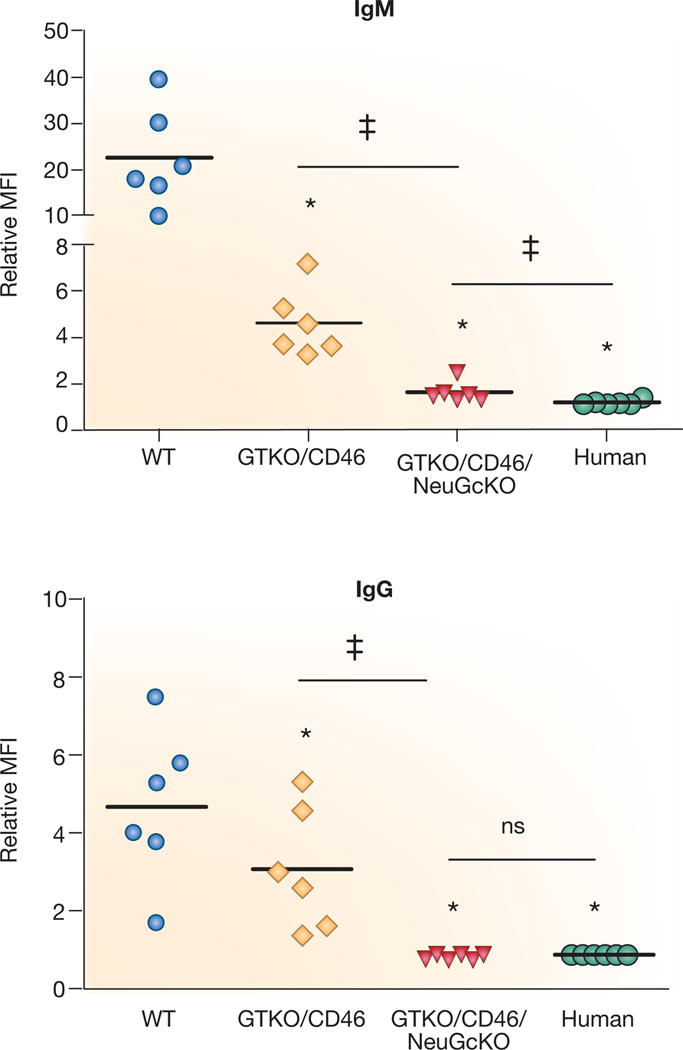

To date, three pig antigens have been identified, the most important of which is galactose-α1,3-galactose (Gal),6 the others being N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NeuGc) and the Sd(a) antigen. All three have now been ‘knocked out in pigs.9 When one or more of these pig antigens is not expressed, there is a significant reduction in the binding of primate antibody to pig vascular endothelial cells (Figure 3). Further graft protection is provided by the expression of a human complement-regulatory protein (e.g., CD46, CD55, CD59) and/or a human coagulation-regulatory protein (e.g., thrombomodulin, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, endothelial protein C receptor). As a result of these genetic manipulations (now including up to 6 in a single pig, the transplantation of pig organs into NHPs is no longer limited by antibody-mediated (hyperacute or acute vascular) rejection.

Figure 3.

Human IgM and IgG antibody binding to pig and human aortic endothelial cells (AECs) by flow cytometry. Human IgM (top) and IgG (bottom) binding to GTKO/hCD46 pAECs was significantly decreased compared to wild-type (WT) pig AECs (*p<0.05), and was further decreased to GTKO/hCD46/NeuGcKO pig AECs (*p<0.05). There was significantly greater IgM binding to GTKO/hCD46/NeuGcKO pig AECs than human AECs (‡p<0.05), but there was no statistical significance in the extent of IgG binding between them.

Furthermore, some of the genetic manipulations already carried out in pigs to reduce the effects of the primate natural antibody and innate immune response (complement and coagulation) have been found to reduce the effects of the T cell response,6, 9 thus reducing the need for exogenous immunosuppressive therapy. Still other genetic modifications can reduce the cellular response further.6, 9

The great advantage of xenotransplantation is that, for the first time, it allows modification of the donor rather than simply of the recipient of the transplant. With the relatively recent introduction of new techniques, such as CRISPR/Cas9, the pace of pig modification will now significantly increase.10

Progress in immunosuppressive therapy

When conventional immunosuppressive therapy, e.g., calcineurin-based, is administered to the NHP recipient – even of a genetically-engineered pig organ – graft failure develops within weeks unless very high levels of the agents are maintained (Table 2). There has been much greater success with some of the newer agents that block the T cell costimulation pathways, e.g., the CD40/CD154 pathway (by anti-CD154mAb or anti-CD40mAb), introduced into xenotransplantation by Buhler et al. in 2000.11 Although anti-CD154mAb therapy is unlikely to be available for clinical use because of its thrombogenic properties, an anti-CD40mAb-based regimen is likely to be equally successful.12

Table 2.

Milestones in pig-to-nonhuman primate kidney transplantation: 1989–2015.*

| Year | Donor (pig) | Recipient | Immunosuppressive regimen | Survival (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | WT | Baboon | Conventional (PE, ALG, CsA, CS, SBGS) |

23 |

| 1998 | CD55 | Cynomolgus monkey | Conventional (CyP, CsA, CS) |

62 |

| 2004 | CD55 | Cynomolgus monkey | Conventional (CyP, CsA, MMF, CS) |

90 |

| 2005 | GTKO | Baboon | Costimulation blockade-based (Anti-CD2mAb, anti-CD154mAb, MMF, CS) |

83 |

| 2015 | GTKO/CD46/CD55/TBM/EPCR/CD39 | Baboon | Costimulation blockade-based (ATG, anti-CD20mAb, anti-CD40mAb, rapamycin, CS) |

136 |

| 2015 | GTKO/CD55 | Rhesus monkey | Costimulation blockade-based (Anti-CD4mAb, anti-CD8mAb, anti-CD154mAb, MMF, CS) |

310 |

Individual references can be found in references 7 and 8.

ALG = anti-lymphocyte globulin/serum; CD39 = expression of the human coagulation-regulatory gene, CD39; CD46 and CD55 = expression of human complement-regulatory genes; CS = corticosteroid; CsA = cyclosporine A; Cyp = cyclophosphamide; EPCR = expression of the human coagulation-regulatory gene, endothelial protein C receptor; GTKO = α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pig; mAb = monoclonal antibody; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; PE = plasma exchange/plasmapheresis; SBGS = administration of soluble blood group substances A and B; TBM = expression of the human coagulation-regulatory gene, thrombomodulin; WT = wild-type (genetically-unmodified) pig.

There is increasing evidence for an inflammatory response to the xenograft that is independent of the adaptive immune response.6 Adjunctive therapy with an anti-inflammatory agent, e.g., the anti-interleukin-6 receptor agent, tocilizumab, appears to be beneficial,12 but here again genetically-engineered pigs expressing an anti-inflammatory transgene (e.g., A20, heme-oxygenase-1) may prove preferable.9

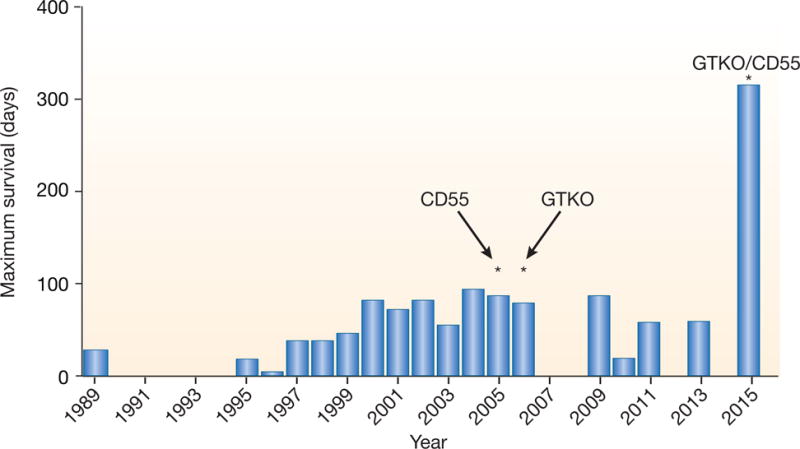

Progress in the pig-to-NHP kidney transplantation model

In 1989, using genetically-unmodified (wild-type) pig kidneys, the longest life-supporting kidney graft survival was 23 days7 (Table 2 and Figure 4). By 2004, CD55-transgenic pig kidney graft survival had been extended to 90 days.8 With cotransplantation of donor-specific thymic tissue, GTKO pig kidney graft survival reached 83 days in 2005.8 In 2015, two groups reported survival of life-supporting genetically-engineered pig kidneys for >4months,12, 13 with one monkey surviving for approximately 10months (Adams A, personal communication). At our own center, we currently have two baboons with life-supporting pig kidney grafts active and healthy at >7 months (Iwase H, et al, unpublished).

Figure 4.

Maximum life-supporting pig kidney graft survival after transplantation into nonhuman primates (by year).

(WT = wild-type [i.e., genetically-unmodified] pig as source of kidney; CD55 = organ source pig genetically modified to express the human complement-regulatory protein CD55 [decay-accelerating factor]; GTKO = α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pig that does not express the important Gal antigen that is a major target for primate anti-pig antibodies; GTKO/CD55 = GTKO pig expressing human CD55).

Potential physiological discrepancies

Although pig kidneys are remarkably similar in structure and relative size to human kidneys, there may be physiological incompatibilities between pig and primate that could potentially be problematic.14 “The size of the transplanted pig kidney could potentially increase according to normal pig growth, at least for a period of time. Indeed, our group has seen growth of the kidney xenograft during the first post-transplant month, but thereafter growth was very modest. This observation correlates with the earlier studies of Soin et al.15 However, others with long-term renal xenograft survival did not observe significant xenograft growth.13 Moderate-to-severe proteinuria with resulting hypoalbuminemia were uniformly documented in the early studies of pig kidney xenotransplantation, necessitating frequent infusions of human albumin.16 Whether this phenomenon was due to the immune response (activation or injury of glomerular and/or tubular cells) or to an inherent physiological incompatibility between pigs and primates, or both, was uncertain. Recently, however, minimal proteinuria with no accompanying hypoalbuminemia has been documented in NHPs with pig kidney grafts, probably because the immune response has been more fully controlled by the genetic modification of the donor pig and/or pharmacological intervention.12, 13

Potential infectious risks

The organ-source pigs will be housed in a biosecure, isolation environment, and the absence of microorganisms of concern will be monitored on a regular basis. The pigs should therefore be preferable in this respect to the average deceased human donor who is likely to transfer viruses such as cytomegalovirus to the recipient of the organ. However, porcine endogenous retroviruses are present in the genome of every pig cell, and therefore will be transferred with the organ. Although the risk associated with these retroviruses is considered small, techniques are now available whereby they could potentially be inactivated or excluded from the pig.9

In summary, therefore, the combination of (i) a graft from a specific genetically-engineered pig, (ii) an effective immunosuppressive regimen, and (iii) anti-inflammatory therapy appears to prevent immune injury and a protein-losing nephropathy, and inhibited (or significantly delays) coagulation dysfunction. To date, no safety concerns that would definitively prohibit a clinical trial have been identified.

Selection of patients for initial clinical trials

The selection of patients who could be considered for a pilot clinical trial of pig kidney xenotransplantation is not as simple as one might anticipate.17 Patients who are considered unacceptable for allotransplantation, e.g., because of the presence of chronic infection or malignant disease, should also be excluded from the initial clinical trials of xenotransplantation as in both cases they would be at high-risk of mortality from the effects of immunosuppressive therapy. This would neither provide a fair trial of xenotransplantation nor be in the patient’s best interests.

The FDA suggests that xenotransplantation should be limited to “patients with serious or life-threatening diseases for whom adequately safe and effective alternative therapies are not available”, while limiting the therapy to those patients “who have potential for a clinically significant improvement with increased quality of life following the procedure”.18 Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESRD) can be supported by hemodialysis, posing questions about the ethics of the initial clinical trials of xenotransplantation that have to be addressed. However, allotransplantation provides improved patient survival and improved quality of life as compared to remaining on dialysis, and it is possible pig kidney transplantation could provide a similar advantage in patients who are candidates for an allograft but who, for specific medical reasons (see below, and reviewed in17), cannot be offered one.

The major reasons for a patient not being a candidate for an allograft are (i) a high degree of allosensitization to human leukocyte antigens (HLA) or (ii) rapid recurrence of primary disease in previous allografts. The new Kidney Allocation System of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) may provide for optimized organ allocation to highly-sensitized patients, but a subgroup of patients will find it near-impossible to be allocated cross-match-negative allografts. Although limited, current published evidence is that a patient sensitized to HLA will be at little greater risk of rejecting a pig graft than an unsensitized patient, although there are some data that conflict with this conclusion19; Tector AJ, et al, unpublished). Furthermore, if anti-pig antibodies develop in the patient after a pig graft, the present limited data suggest that this should not preclude the patient from subsequent allotransplantation.

At our center, if a patient has lost two allografts in the previous 4 years from recurrence of the primary disease (in the absence of acute or chronic rejection, noncompliance with medications, or other technical issues), we will not relist that patient for a further allograft. Diseases such as focal sclerosing glomerulonephritis (FSGS), immunoglobulin A nephropathy, and dense deposit membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN type II; dense deposit disease) have a high incidence of recurrence (reviewed in17).

FSGS is the primary diagnosis in about 5% of all patients undergoing renal transplantation. A subset of these patients experience recurrence, sometimes rapidly, and in a second allotransplant the recurrence rate may reach 80–100%. In one report, of 8 patients who lost their primary allograft rapidly to FSGS, 3 patients lost 6 subsequent allografts within 5 months, demonstrating the rationale for not retransplanting this patient subgroup.

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy is the cause of ESRD in 20% of patients who go on to have a kidney allograft. Recurrence leading to graft failure is less frequent than for FSGS, but still results in ESRD in 2–16% of patients with allografts. Recurrence is more common in a second graft. Recurrence of MPGN type II can be as high as 41–49%, and 42–67% of these patients subsequently lose their allografts.

It is not known whether there will be a similar risk of disease recurrence in the xenograft or whether the pig kidney will be resistant to this.

Psychosocial aspects

Successful xenotransplantation will avoid some of the ethical problems associated with allotransplantation in some parts of the world, e.g., coercion and/or payment of living donors.20 It will also avoid some of the stresses related to allotransplantation, e.g., the long wait for a suitable deceased human organ, and reduce the complications and costs associated with long-term dialysis. However, there are potential patient and family psychosocial factors that may be encountered by the medical team that have not been considered previously (Table 3).21

Table 3.

Possible psychosocial factors in the recipient associated with solid organ allotransplantation or xenotransplantation*

| Factor | Allotransplantation | Xenotransplantation |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial/compliance issues | Yes | Yes |

| Stress related to donor availability | Yes | No |

| Stress related to extended waiting time | Yes | No |

| Religious concerns | Possibly | Possibly |

| Concern related to male/female gender | Possibly | No |

| Concern related to ‘humanness’ | No | Possibly |

| Stress related to public health issues | No | Possibly |

| Doubts related to animal rights | No | Possibly |

| Doubts related to public opinion | No | Possibly |

| Concerns related to potential unknown risks of infection | Possibly | Yes |

The views and beliefs of potential xenotransplant recipients and families have not been widely explored. Concerns go beyond the issue of whether or not Muslims and Jews consume pork, as the implantation of a pig organ may have a much greater psychosocial impact. There are religious and psychological issues that need to be better understood. The broader question is what it means to be ‘human’ from the perspective of the patient, family, and community, rather than from that of the medical profession. The preponderance of the existing literature is primarily from an individual professional, cultural, or philosophical perspective and, although helpful, does not really provide the guidance necessary for the transplant team in the psychosocial selection of the candidate or care of the recipient.

More needs to be done to explore public opinion about the potential risks associated with xenotransplantation, coupled with efforts to educate society about the procedure. For example, attitudes to animal rights may impact the selection of candidates, and there is a lack of information on the relationship between a patient’s theological beliefs (if any) and his or her attitude to xenotransplantation.

Regulation of clinical trials of pig kidney transplantation

This topic has recently been comprehensively reviewed by Schuurman.22 Clinical trials of pancreatic islet23 and corneal xenotransplantation have already been performed in some parts of the world, and other trials are currently underway, but the governmental/legal framework in the US may be more stringent, particularly in regard to the transplantation of solid organs, such as the kidney.

In addition to providing guidance on source animal characterization, microbiological testing of animals, and preclinical considerations, the federal guideline that addresses xenotransplantation in the USA also discussed clinical issues.18 This document serves as a benchmark for what the US government is considering on the topic of xenotransplantation.

Obtaining consent for a clinical trial to be initiated in the US will not be a simple procedure.24 The Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) oversees the transplantation of vascularized human organs. The FDA has regulatory oversight of xenotransplantation products, including live organs, and clinical investigation will need an Investigation New Drug (IND) application. The FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) regulates genetically-engineered animal products.25

At some point in the relatively near future, we believe that representatives of those working in the field of xenotransplantation, as well as regulatory agencies under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (FDA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HRSA, National Institutes of Health, and the DHHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation) and the FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine, will feel comfortable with initiating clinical trials of pig organ transplantation.

Legal Implications

Assuming all federal guidelines are followed, as well as adherence to a local Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol, transplant centers could still be exposed to legal action.26 The main legal concern for a transplant center would be to be held accountable for the transmission of an infectious disease from the organ to the recipient. Although very unlikely, it remains a possibility that a porcine microorganism may not only infect the patient, but be passed to close contacts, e.g., family, hospital staff, and thus be spread into the community. Legal defenses would rest on following Federal Guidelines and being transparent to the public.

Conclusions

The average waiting time for a kidney allograft is now >5 years in the US, during which period the patient’s general health frequently declines. There is a negative correlation between the length of the waiting period and the outcome of kidney allotransplantation. There is, therefore, an urgent need for an alternative source of kidneys for clinical transplantation. Recent progress in the experimental laboratory suggests that genetically-engineered pigs will fulfill this need.

In the initial clinical trials, carefully-selected patients who are unable to obtain an allograft may benefit significantly, thus extending this novel form of therapy to all patients suitable for kidney transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Work on xenotransplantation in the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute at the University of Pittsburgh has been supported in part by NIH grants U01 AI068642, R21 AI074844, and U19 AI090959, and by Sponsored Research Agreements between the University of Pittsburgh and Revivicor, Inc., Blacksburg, VA.

Abbreviations

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FSGS

focal sclerosing glomerulonephritis

- GTKO

galactose-α1,3-galactose (Gal) gene-knockout

- MPGN

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- NHP

nonhuman primate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

No author reports a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ekser B, Cooper DK, Tector AJ. The need for xenotransplantation as a source of organs and cells for clinical transplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;23:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL. Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1859–1865. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JM, Schnitzler MA, Gustafson SK, et al. Cost Implications of New National Allocation Policy for Deceased Donor Kidneys in the United States. Transplantation. 2016;100:879–885. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper DK. The case for xenotransplantation. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:288–293. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper DK. A brief history of cross-species organ transplantation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2012;25:49–57. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2012.11928783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DK, Ezzelarab MB, Hara H, et al. The pathobiology of pig-to-primate xenotransplantation: a historical review. Xenotransplantation. 2016;23:83–105. doi: 10.1111/xen.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambrigts D, Sachs DH, Cooper DK. Discordant organ xenotransplantation in primates: world experience and current status. Transplantation. 1998;66:547–561. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper DK, Satyananda V, Ekser B, et al. Progress in pig-to-nonhuman primate transplantation models (1998–2013): a comprehensive review of the literature. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21:397–419. doi: 10.1111/xen.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper DK, Ekser B, Ramsoondar J, et al. The role of genetically-engineered pigs in xenotransplantation research. J Pathol. 2016;238:288–299. doi: 10.1002/path.4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler JR, Ladowski JM, Martens GR, et al. Recent advances in genome editing and creation of genetically modified pigs. Int J Surg. 2015;23:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhler L, Awwad M, Basker M, et al. High-dose porcine hematopoietic cell transplantation combined with CD40 ligand blockade in baboons prevents an induced anti-pig humoral response. Transplantation. 2000;69:2296–2304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwase H, Liu H, Wijkstrom M, et al. Pig kidney graft survival in a baboon for 136 days: longest life-supporting organ graft survival to date. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:302–309. doi: 10.1111/xen.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, et al. Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:221–230. doi: 10.1111/xen.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim Z, Busch J, Awwad M, et al. Selected physiologic compatibilities and incompatibilities between human and porcine organ systems. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soin B, Ostlie D, Cozzi E, et al. Growth of porcine kidneys in their native and xenograft environment. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:96–100. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soin B, Smith KG, Zaidi A, et al. Physiological aspects of pig-to-primate renal xenotransplantation. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1592–1597. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper DKC, Wijkstrom M, Hariharan S, et al. Selection of patients for initial clinical trials of solid organ xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001582. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FDA. Guidance for industry: source animals, product, preclinical, and clinical issues concerning the use of xenotransplantation products in human. 2016 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Xenotransplantation/ucm074354.htm. 2003.

- 19.Oostingh GJ, Davies HF, Tang KC, et al. Sensitisation to swine leukocyte antigens in patients with broadly reactive HLA specific antibodies. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:267–273. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smetanka C, Cooper DK. The ethics debate in relation to xenotransplantation. Rev Sci Tech. 2005;24:335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paris W, Jang K, Bargainer R, et al. Psychosocial challenges of xenotransplantation: the need for a multi-disciplinary, religious, and cultural dialogue. Xenotransplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/xen.12263. (Resubmitted after revision) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuurman HJ. Regulatory aspects of clinical xenotransplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;23:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper DKC, Matsumoto S, Abalovich A, et al. Progress in clinical encapsulated islet xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001371. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arcidiacono JA, Evdokimov E, Lee MH, et al. Regulation of xenogeneic porcine pancreatic islets. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CVM, published Guidance for Industry in June 2015: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/animalveterinary/guidancecomplianceenforcement/guidanceforindustry/ucm113903.pdf.

- 26.Triller K, Bobinski MA. Tort liability of xenotransplantation centers. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:310–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]