Abstract

Objective

How a healthy lifestyle intervention changes the frequency and duration of daily moderate-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior has not been well-characterized. Secondary analyses of data from the Make Better Choices randomized controlled trial were conducted to evaluate how interventions to increase physical activity or reduce leisure screen time affected the frequency and duration of these behaviors during treatment initiation and follow-up.

Methods

Participants were 202 adults who exhibited insufficient physical activity, excessive screen time and poor diet during a 14-day baseline screening period. The design was a randomized controlled trial with a three-week intervention period followed by eight 3-7 day bursts of data collection over the 6-month follow-up period after intervention termination. Participants self-reported on their physical activity and screen time at the end of each day.

Results

A two-part multilevel model indicated that, relative to baseline levels, the physical activity intervention increased the odds of daily moderate-vigorous intensity physical activity (frequency) but not the duration of activity during the intervention period and these effects persisted (albeit somewhat more weakly) during the follow-up period. The screen time intervention reduced both the frequency and duration of daily screen time from the beginning of the intervention through the follow-up period.

Conclusions

A three-week intervention increased daily physical activity frequency but not duration, and reduced both the frequency and duration of daily leisure screen time. These effects were maintained over 20 weeks following the end of the intervention.

Keywords: Exercise, Sitting, mHealth, Intraindividual

Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness reduce risk for premature mortality from non-communicable diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some cancers (Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2008). However, less than 50% of American adults report that they meet national physical activity guidelines, which prescribe either 75 min of vigorous-intensity or 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity in addition to twice weekly muscle strengthening activities on all major muscle groups (Carlson, Fulton, Schoenborn, & Loustalot, 2010). Accelerometer data suggest that the scope of inactivity in the United States may even be an order of magnitude greater(Troiano et al., 2008). Whereas insufficient moderate-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) is one form of physical activity risk behavior, adult Americans also spend more than 50% of their time engaged in sedentary behaviors which further increases their risk for premature mortality from chronic disease (Biswas et al., 2015; Matthews et al., 2008; Rezende, Rodrigues Lopes, Rey-López, Matsudo, & Luiz, 2014). One of the most common and modifiable forms of sedentary activity is time spent in front of a television or computer screen. Sedentary behavior pattern is one component of a broader syndrome of multiple clustered diet and activity chronic disease risk behaviors that is prevalent among western adults (e.g., consuming too many saturated fats, eating too few fruits and vegetables; Spring et al., 2014; Spring, King, Pagoto, Van Horn, & Fisher, 2015; Spring, Moller, & Coons, 2012). Adults with multiple behavioral risk factors are a priority population for preventive intervention because reducing a single risk behavior in these populations may have ripple effects that reduce other risk factors, thus cost-effectively improving health (Wilson, 2015). The current study examined how a multiple-behavior change intervention targeting several unhealthy diet and activity behaviors specifically affected MVPA and sedentary leisure screen time, in a sample with multiple behavioral risk factors. A question of particular interest was how participants adapted the frequency and duration of their MVPA and screen time in response to the intervention.

Contemporary lifestyle behavior change interventions are frequently guided, either explicitly or implicitly, by conceptual models from both control theory and social-cognitive theory. According to control theory, people set goals and then monitor, evaluate, and regulate their behavior to minimize discrepancies between the intended and actual behavior (Carver & Scheier, 1982, 1998). These negative feedback loops require effort to initiate unfamiliar or challenging behaviors but such change should become easier as a person gains experience and accumulates success at regulating their behavior around specific goals. These mastery experiences also shape people’s beliefs about their own capacity to enact desired lifestyle behaviors. Enhancing these self-efficacy beliefs is critical to behavior change in social-cognitive theory because they can influence behavior directly and indirectly (e.g., by promoting relevant goals or strengthening the effects of outcome expectations; Bandura, 1989, 2004). Based on the mechanisms of behavior change outlined in these theories, contemporary interventions frequently incorporate techniques such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, prompting, barrier identification, and social support to support motivation for lifestyle behavior change (Michie, Abraham, Whittington, McAteer, & Gupta, 2009).

Even with theory-driven behavior change techniques, deeply-engrained behaviors can be resistant to change. A failure to engage people in these effortful behavior change processes presents a fundamental barrier to change. Engagement with behavior change techniques can be enhanced with financial incentives (Gingerich, Anderson, & Koland, 2012). Such incentives are generally accepted and have shown promise for initiating behavior change (Giles, Robalino, McColl, Sniehotta, & Adams, 2014; Giles, Robalino, Sniehotta, Adams, & McColl, 2015). Financial incentives are often not sustainable long-term and effects typically disappear after removing the incentives (Mantzari et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2013). For that reason, it may be best to deploy financial incentives as a short-term strategy for engaging people in effortful self-regulation and improving health behavior.

An illustrative intervention derived from these findings to increase physical activity and reduce leisure screen time was the multiple-behavior change Make Better Choices intervention (Spring et al., 2010). This trial incorporated features such as progressive goal setting, self-monitoring with feedback, and behavior coaching. The primary outcome from this trial was a Composite Diet-Activity Improvement Score based on four diet and activity behaviors considered in aggregate. This composite measure improved most for participants who received interventions to increase fruit-vegetable intake and reduce screen time (Spring, Schneider, et al., 2012). Although the effect of interventions on individual health behaviors, such as physical activity, was plotted, it was not examined with inferential tests. Hence, the present study provides a more granular test of the nature of intervention effects on within-person changes in physical activity and leisure screen time as participants progressed from baseline through the intervention phases and through a 5-month follow-up phase.

Several unique characteristics of the Make Better Choices trial shaped our evaluation. First, since participants recorded their physical activity and leisure screen time daily, the resulting stream of intensive physical activity data invites tests of within-person changes in behavior from the baseline phase through the intervention and follow-up phases. This approach can thus estimate average intervention effects on person-specific behavior change (as opposed to changes in group average behavior). Modeling daily behavior instead of average behavior during a phase also permits us to control for established weekday-weekend differences in physical activity and total sedentary time (Conroy, Elavsky, Maher, & Doerksen, 2013; Conroy, Maher, Elavsky, Hyde, & Doerksen, 2013). The sensitivity of this approach to within-person behavior change provides a window into phase-specific intervention effects for individual participants rather than the statistically-constructed average person who may not resemble any actual people in the study.

Second, whereas many activity-related interventions focus on a global behavioral outcome (e.g., total volume of physical activity or total duration of sedentary behavior), the daily data collected in the MBC trial afforded an opportunity to differentiate between two dimensions of behavior: frequency and duration. This distinction is important for lifestyle physical activity interventions where the level of behavior is prescribed but not closely supervised in-person. The complexity of physical activity enables people to change their behavior in a variety of ways in response to an intervention yet little is known about the ways in which people actually modify their behavior in lifestyle interventions. Evaluating whether daily behavior changes in frequency, duration, or both is essential for understanding intervention effects and optimizing dose-response relations with health outcomes. With respect to sedentary behavior, the limited research on intervention efficacy has focused on total sedentary behavior without regard to the patterning of this behavior over time. This study will provide new insights into how people adapt when attempting to increase physical activity or reduce leisure screen time.

The Make Better Choices interventions for physical activity and sedentary behavior involved goals of increasing MVPA to at least 60 minutes per day or decreasing leisure screen time to less than 90 minutes each day. Participants who were assigned the goal of increasing MVPA were asked to increase both the frequency and duration of their MVPA. The physical activity intervention was hypothesized to increase the frequency and duration of daily physical activity, as compared to baseline, during both the intervention and follow-up phases of the trial. Likewise, since the sample consistently engaged in high levels of screen time, participants given the goal of decreasing screen time were advised both to decrease the daily duration of screen time and to increase the days with no screen time by substituting other activities. Three weeks of daily self-monitoring, graded goals, feedback, coaching, and incentives may suffice to plant the seeds for behavioral maintenance so we hypothesized the intervention would reduce both the daily frequency and duration of leisure screen time, relative to baseline levels, and that improvements would be maintained during the follow-up period. In testing these hypotheses, we controlled for time-varying characteristics (e.g., day of the week, day in the study) and time-invariant characteristics (e.g., age, sex, estimated household income, education, minority status, body mass index) that are associated with physical activity and sedentary behavior. The primary outcomes for this analysis were self-reported so we also controlled for individual differences in social desirability response bias.

Methods

Participants

The MBC sample included 204 adults who responded to community advertisements and had all of four behavioral risk factors (i.e., < 5 fruit/vegetable servings/day, >8% saturated fat intake, < 60 min/day MVPA, and >90 min/day screen time). Participants were randomized to one of 4 treatments, each of which involved both an activity intervention (either to increase physical activity or decrease leisure screen time) and a dietary intervention (either to increase fruit/vegetable consumption or decrease saturated fat intake). Study candidates were excluded if they had unstable medical conditions, current eating or substance use disorder, current suicidal ideation, or weighed more than 300 lbs. Daily data from two cases randomized to increase physical activity were lost during a laboratory move, leaving 202 participants for analysis. As seen in Table 1, the average participant was an overweight, young to early-midlife adult with a household income that would be considered middle class. The sample was mostly female (76%) with a balance between White (45%) and non-White (55%) races, and a variety of educational attainments ranging from not completing a bachelor’s degree (30%) to completing a graduate degree (26%). Full details about sample characteristics were reported by Spring et al. (2012).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for sample demographics and behavioral outcomes at baseline

| M (SD) | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.90 (11.0) | 29 | 21 – 60 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.34 (7.27) | 26.71 | 16.99 – 59.98 |

| Female | 76% | ||

| Minority status (%) | 45% | ||

| Income | |||

| $0-$15,000 (%) | 9.4% | ||

| $15,000-$20,000 (%) | 5.0% | ||

| $20,000-$25,000 (%) | 6.4% | ||

| $25,000-$30,000 (%) | 5.0% | ||

| $30,000-$35,000 (%) | 7.9% | ||

| $35,000-$40,000 (%) | 5.4% | ||

| $40,000-$45,000 (%) | 7.9% | ||

| $45,000-$50,000 (%) | 6.4% | ||

| $50,000-$60,000 (%) | 10.4% | ||

| $60,000-$75,000 (%) | 7.9% | ||

| Over $75,000 (%) | 28.2% | ||

| Education | |||

| Did not complete Bachelor's degree (%) | 29.7% | ||

| College graduate (%) | 22.8% | ||

| Some graduate coursework (%) | 21.3% | ||

| Graduate degree (%) | 26.2% | ||

| Social desirability | .54 (.18) | .55 | 0 – 1 |

| Frequency of daily MVPA | 0.66 (0.47) | 1 | 0 – 1 |

| Duration of MVPA (log(min)) | 4.33 (0.94) | 4.32 | 0.00 – 7.27 |

| Frequency of daily screen time | 0.87 (0.34) | 1 | 0 – 1 |

| Duration of screen time (log(min)) | 4.94 (0.84) | 5.01 | 1.61 – 7.21 |

Note. Frequency of physical activity and screen time codes indicated the complete absence of the behavior (0) or a non-zero level of the behavior (1).

Procedures

Study procedures were outlined in detail by Spring et al. (2010; 2012). Briefly, participants completed a two-week baseline phase during which they used a handheld electronic device to record dietary intake and provide end-of-day reports on their physical activities and leisure screen time. At the end of the baseline phase, participants who consistently exhibited all four lifestyle risk behaviors were stratified by sex and randomized to an intervention condition. Each intervention involved two phases (for specific details on the intervention, see Spring et al., 2010). In the first week (half-goal phase), coaches worked with each participant to set a behavior change goal halfway between their baseline level and the ultimate goal. This proportional initial goal allowed for early successes as behavioral skills were gradually shaped. Early successes that support the formation of efficacy beliefs were considered essential because the study population struggles with multiple health risk behaviors and was provided only a limited intervention period to build self-efficacy. Once participants attained the half-goal level, coaches raised goals to the full level for the final two weeks of the intervention period (full-goal phase). The full activity goal was ≥60 min of MVPA daily for those asked to increase activity or <90 min leisure screen time daily for those asked to decrease sedentary leisure. For example, a participant randomized to increase activity who had no minutes of MVPA during the baseline phase would be instructed to engage in 30 min of MVPA daily during the half-goal phase and to increase to 60 min daily during the full-goal phase.

Participants continued to self-monitor and electronically record and transmit to their coach at the end of each day the type and duration of all physical activities and leisure screen time throughout both the half-goal and full-goal phases of the three-week intervention period. Coaches referred to those data in weekly coaching calls when they provided supportive accountability, encouragement and help in planning how to cope with anticipated barriers. To fully engage participants and motivate them to change behaviors, financial incentives were offered to participants who met their daily behavior change goals (either by modifying frequency, duration, or both) and uploaded data during the half-goal phase ($175 total; Spring et al., 2010).

At the end of the intervention period, participants completed eight bursts of data collection over the next 20 weeks (follow-up phase). These bursts were scheduled for 7 days immediately after the intervention ended, 3 consecutive days in (a) each of the next two weeks, (b) every other week for weeks 4-9, and (c) monthly until the end of the follow-up period. During data collection bursts, participants engaged in self-monitoring but received no behavioral feedback, coaching or performance-contingent financial incentives. Financial incentives during this phase were offered to participants who uploaded data during each follow-up phase ($30 - $80/week; Spring et al., 2010). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Illinois-Chicago and Northwestern University.

Measures

The duration of daily physical activity and leisure screen time were assessed with an end-of-day 24-hour activity log. Regardless of intervention condition, participants accounted for their physical activity and leisure screen time during each 15-minute block of the day by selecting activities from the Compendium of Physical Activities (Ainsworth et al., 2000). Valid responses were encouraged using a bogus pipeline method that involved collecting urine samples and having participants wear an accelerometer (Actigraph 7164; Actigraph, LLC, Pensacola, Florida) during the baseline and intervention (but not follow-up) phases of the trial with the explanation that the biomarker and sensor data would be used to validate self-reported diet and physical activity scores (Roese & Jamieson, 1993). Self-reports were selected as the outcome for this study for several reasons. First, self-reported MVPA and sedentary data were the metrics participants used to self-regulate their behavior because at the time of the study, it was not possible to transmit accelerometry data to the handheld self-monitoring device in real time. Second, accelerometers were not used during the follow-up period. Third, accelerometers are not able to differentiate the targeted sedentary behavior (i.e., leisure screen time) from other forms of sedentary behavior.

The threat of socially-desirable response bias was controlled statistically by using the 33-item Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960). Participants rated items as being true (0) or false (1) for them; scores were calculated by averaging responses (after reverse-scoring relevant items) so that higher values indicated a greater tendency to respond in a socially-desirable manner.

Data Analysis

Daily activity logs were filtered to remove time spent in light-intensity physical activity and work-related screen time. The resulting score distributions were severely (positively) skewed because of the high frequency of days, across all groups and phases of the trial, during which participants reported either no MVPA or no screen time (see Results for details). To separate the processes that generated these data, each daily score was recoded as two variables: a binary variable indicating whether the participant reported engaging in any of the behavior that day (e.g., days with no physical activity/screen time were coded as 0 and days with any physical activity/screen time were coded as 1) and a continuous variable representing the duration of daily physical activity or leisure screen time. The latter variable was log-transformed to normalize the distribution, and values were set to missing when the participant reported no physical activity or leisure screen time for the day.

The four intervention groups were recoded as two directional goals on two experimental factors representing activity and diet interventions, respectively. For the physical activity model, groups of participants who received the increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behavior interventions were coded as +1 and −1, respectively. For the screen time model, those codes were reversed to facilitate interpretations. For both models, groups of participants who received the increase fruit/vegetable consumption and decrease saturated fat consumption were coded as +1 and −1, respectively. We calculated the interaction between these two experimental factors to represent the combination of activity and diet interventions.

Daily physical activity and leisure screen time scores were nested within participants. Consequently, multilevel mixed models were estimated to adjust for dependencies inherent in having repeated observations from each participant (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). Using the two-part random-effects model described by Olsen and Schafer (2001), the frequency of each behavior was modeled as the odds of a person reporting any amount of the behavior on a given day, and the duration was modeled as the number of minutes spent in the behavior (on days when the individual reported engaging in any amount of the behavior). By modeling these outcomes simultaneously, it was possible to maximize information about how the intervention changed behavior. Both outcomes were regressed on a common set of within- and between-person predictors. At the within-person level, both frequency and duration were regressed on a series of dummy variables that represented the days of the week and the intervention phase. Wednesday and Sunday were set as the reference categories in the physical activity and screen time models, respectively, because they had the lowest overall levels of physical activity and greatest screen time. The three dummy variables that represented the intervention phase were half-goal, full-goal, and follow-up; baseline served as the reference category. The three phase variables had random effects for both outcomes. At the between-person level, the average frequency and duration scores were regressed on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, body mass index, income, education, and minority status), social desirability, and three variables representing the two intervention factors (activity, diet) and their interaction. The slopes for the three intervention phases were regressed on the three variables representing the two intervention factors and their interaction. Covariances were estimated between the slopes for the intervention phases.

Results

Table 1 summarizes demographic and behavioral characteristics of the sample.

Daily Physical Activity

Participants provided physical activity data on a mean of 63.9 days (SD = 3.6, range = 49 – 102) for a total of 11,971 person·days. Across all groups and phases of the study, participants reported spending no time engaged in MVPA on 4058 days (33.9%).

The two-part model of physical activity was first estimated with the full set of covariates described above. When non-significant covariates were removed, conclusions about intervention effects remained identical. For presentational clarity, Table 2 presents coefficients from the reduced model. Coefficients on the left side of this table were based on covariates of physical activity frequency; coefficients on the right side of this table were based on covariates of physical activity duration.

Table 2.

Two-part multilevel model of daily physical activity frequency and duration

| Frequency |

Duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (π) |

SE | Odds Ratio |

Coefficient (γ) | SE | |

| Between-person model | |||||

| Activity intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | 0.99* | 0.44 | 2.69 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | 1.23** | 0.14 | 3.42 | 0.12** | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention X Follow-up phase | 0.49** | 0.11 | 1.63 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Diet intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | −0.06 | 0.20 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Diet intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | −0.05 | 0.18 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Diet intervention X Follow-up phase | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | −0.13 | 0.16 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | −0.02 | 0.20 | 0.98 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Follow-up phase | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.94 | −0.08 | 0.04 |

| Activity intervention | −0.09 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Diet intervention | 0.11 | 0.11 | 1.12 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Activity X Diet intervention interaction | 0.33** | 0.11 | 1.39 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Non-White | −0.42 | 0.24 | 0.66 | −0.10 | 0.08 |

| Social desirable response bias | 0.96 | 0.65 | 2.61 | 0.72** | 0.22 |

| Covariance: slopes for initial (half-goal) and final intervention | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.09** | 0.03 | |

| Covariance: slopes for initial (half-goal) intervention and follow-up | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.04 | |

| Covariance: slopes for final intervention and follow-up | 0.59** | 0.14 | 0.10* | 0.04 | |

| Residual variance in slope for initial (half-goal) intervention phase | 0.54 | 0.93 | 0.11** | 0.04 | |

| Residual variance in slope for final intervention phase | 0.96** | 0.24 | 0.13** | 0.04 | |

| Residual variance in slope for follow-up phase | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.16** | 0.05 | |

| Residual between-person variance | 1.59** | 0.28 | 0.20** | 0.04 | |

| Within-person model | |||||

| Threshold (Logistic Model)/Intercept (Continuous Model) | −0.57** | 0.31 | 4.15** | 0.07 | |

| Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | 1.06 | 0.67 | 2.89 | 0.14** | 0.04 |

| Final (full-goal) intervention phase | 1.16** | 0.13 | 3.19 | 0.20** | 0.04 |

| Follow-up phase | 0.52** | 0.13 | 1.68 | 0.16** | 0.04 |

| Monday | 0.17 | 0.09 | 1.19 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Tuesday | 0.16 | 0.09 | 1.18 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Thursday | 0.32** | 0.09 | 1.38 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Friday | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Saturday | −0.00 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.26** | 0.06 |

| Sunday | −0.19 | 0.12 | 0.82 | 0.19** | 0.05 |

| Residual within-person variance | 0.58** | 0.02 | |||

Note. Covariances were estimated between slopes p < .01,

p < .05.

Frequency of physical activity

The first key finding from this study was that participants who received the intervention to increase physical activity were significantly more likely to engage in physical activity during the half-goal (odds ratio [OR] = 2.69), full-goal (OR = 3.42), and follow-up phases (OR = 1.63) than during the baseline phase. The diet intervention was not associated with physical activity frequency during any phase (nor did it moderate effects of the activity intervention).

Additional coefficients in the model indicated that participants in the condition that targeted both increased physical activity and decreased saturated fat consumption reported the least frequent baseline physical activity. Individual differences in age, sex, race, BMI, income, education, and socially-desirable response bias were not associated with physical activity frequency. The odds of engaging in physical activity on any day were unassociated between the half-goal and both full-goal and follow-up phases. Participants who increased physical activity frequency most in the full-goal phase had the greatest increases in physical activity frequency during the follow-up phase (covariance [cov] = 0.59). At the within-person level, participants were more likely to report physical activity during the full-goal (OR = 3.19) and follow-up (OR = 1.68) phases than baseline. Participants also were more likely to engage in physical activity on Thursdays (compared to Wednesdays; OR = 1.38).

Duration of physical activity

The second key finding from this study was that the duration of daily MVPA increased as a function of the physical activity intervention during the full-goal phase (γ = 0.12) but not during the half-goal or follow-up phases. The diet intervention did not affect physical activity duration at any phase (nor did it moderate effects of the activity intervention).

Additional coefficients in the model indicated that participants who increased their physical activity duration most in the half-goal and full-goal phases had the greatest increases in physical activity duration during the full-goal (cov = 0.09) and follow-up phases (cov = 0.10), respectively. Changes in physical activity duration in the half-goal and follow-up phases were not associated. Participants with high social desirability scores reported longer daily PA duration (γ = 0.72); no other individual differences were associated with the daily physical activity duration. At the within-person level, the duration of activity reported was longer in the half-goal (γ = 0.14), full-goal (γ = 0.20), and follow-up phases (γ = 0.16) than the baseline phase. Participants also reported longer physical activity duration on Saturdays (γ = 0.26) and Sundays (γ = 0.19; compared to Wednesdays).

Summary of physical activity effects

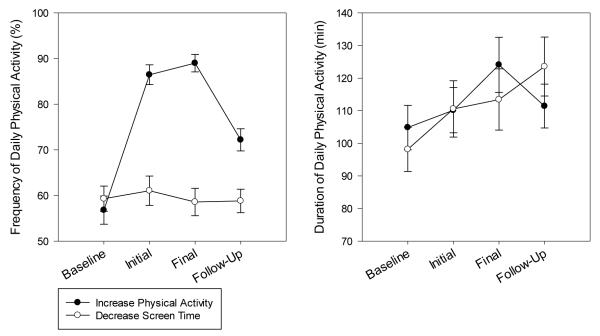

Figure 1 presents observed data on daily physical activity frequency and duration for the groups assigned to increase physical activity and reduce screen time. These plots illustrate that the activity intervention increased the frequency of daily physical activity considerably (~50% increase in daily engagement by the full-goal phase) but had a small, transient effect on activity duration (<20% increase by the full-goal phase which disappeared at follow-up).

Figure 1.

Observed frequency (left panel) and duration (right panel) of physical activity for groups assigned to increase physical activity and reduce screen time.

Daily Screen Time

Participants provided screen time data on a mean of 63.9 days (SD = 3.6, range = 49 – 102) for a total of 11,999 person·days. Across all groups and phases, participants reported having no screen time on 1562 days (13.0%).

The two-part model for screen time was first estimated with the full set of covariates described above. When non-significant covariates were removed, conclusions about intervention effects remained identical, so Table 3 presents coefficients from this reduced model. Coefficients on the left side of this table were based on covariates of screen time frequency; coefficients on the right side of this table were based on covariates of screen time duration.

Table 3.

Complete two-part multilevel model of daily screen time frequency and duration

| Frequency |

Duration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (π) |

SE | Odds Ratio |

Coefficient (γ) | SE | |

| Between-person model | |||||

| Activity intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | −0.33** | 0.06 | 0.72 | −0.28** | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | −0.65** | 0.14 | 0.52 | −0.32** | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention X Follow-up phase | −0.46** | 0.13 | 0.63 | −0.23** | 0.03 |

| Diet intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Diet intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | −0.02 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Diet intervention X Follow-up phase | −0.06 | 0.13 | 0.94 | 0.06* | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Final (full-goal) intervention phase | 0.22 | 0.14 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention X Diet intervention X Follow-up phase | 0.18 | 0.12 | 1.20 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Activity intervention | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.90 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Diet intervention | 0.13 | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Activity X Diet intervention interaction | −0.26* | 0.10 | 0.77 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Sex | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.84 | −0.25** | 0.07 |

| Socially-desirable response bias | −0.78 | 0.51 | 0.46 | −0.35* | 0.16 |

| College graduate | 0.44* | 0.19 | 1.55 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Some graduate education | 0.21 | 0.27 | 1.23 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Graduate degree | 0.26 | 0.22 | 1.30 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Covariance: slopes for initial (half-goal) and final intervention | 0.30** | 0.08 | 0.08** | 0.02 | |

| Covariance: slopes for initial (half-goal) intervention and follow-up | 0.38** | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Covariance: slopes for final intervention and follow-up | 0.69** | 0.19 | 0.04** | 0.01 | |

| Residual variance in slope for initial (half-goal) intervention phase | 0.15** | 0.04 | 0.09** | 0.02 | |

| Residual variance in slope for final intervention phase | 1.06** | 0.30 | 0.09** | 0.02 | |

| Residual variance in slope for follow-up phase | 1.23** | 0.22 | 0.09** | 0.01 | |

| Residual between-person variance | 0.76** | 0.13 | 0.12* | 0.01 | |

| Within-person model | |||||

| Threshold (Logistic)/Intercept (Continuous) | −3.24** | 0.16 | 0.04 | 5.58** | 0.08 |

| Initial (half-goal) intervention phase | −0.52** | 0.06 | 0.59 | −0.39** | 0.03 |

| Final intervention phase | −0.63** | 0.14 | 0.54 | −0.48** | 0.03 |

| Follow-up phase | −0.76** | 0.13 | 0.47 | −0.32** | 0.03 |

| Monday | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.92 | −0.24** | 0.03 |

| Tuesday | −0.24* | 0.12 | 0.79 | −0.30** | 0.03 |

| Wednesday | −0.41** | 0.13 | 0.66 | −0.31** | 0.03 |

| Thursday | −0.38** | 0.13 | 0.68 | −0.32** | 0.03 |

| Friday | −0.64** | 0.12 | 0.53 | −0.25** | 0.03 |

| Saturday | −0.48** | 0.13 | 0.62 | −0.09** | 0.03 |

| Residual within-person variance | 0.39** | 0.01 | |||

Note. p < .01,

p < .05.

Frequency of screen time

The third key finding from this study was that participants who received the screen time reduction intervention were significantly less likely to report any screen time on any given day during the half-goal (OR = 0.72), full-goal (OR = 0.52), and follow-up phases (OR = 0.63) (i.e., they decreased the frequency of days with leisure screen time relative to baseline). The diet intervention was not associated with changes in the frequency of daily leisure screen time during any phase (nor did it moderate effects of the screen time intervention).

Additional coefficients in the model indicated that participants in the condition that targeted increased physical activity and decreased saturated fat intake reported the least frequent baseline screen time. Participants with a college education reported more days with leisure screen time than those without a college education (OR = 1.55). Participants who reduced daily screen time frequency in the half-goal phase reduced daily screen time frequency during the full-intervention (cov = 0.30) and follow-up phases (cov = 0.38). Likewise, participants who reduced daily screen time frequency in the full-intervention phase reduced daily screen time frequency in the follow-up phase (cov = 0.69). No other between-person individual differences were associated with daily leisure screen time frequency. At the within-person level, participants reported less frequent daily leisure screen time during the half-goal (OR = 0.59), full-goal (OR = 0.54) and follow-up phases (OR = 0.47; compared to baseline) and from Tuesday through Saturday (OR ≤ 0.79; compared to Sundays).

Duration of screen time

The fourth key finding from this study was that participants who received the intervention to reduce sedentary behavior decreased their duration of daily screen time during the half-goal (γ = −0.28), full-goal (γ = −0.32), and follow-up phases (γ = −0.23). The diet intervention was not associated with screen time duration in the half-goal or full-goal phases but participants who received the intervention to increase fruit/vegetable consumption increased screen time during the follow-up phase (γ = 0.06). The diet intervention did not moderate effects of the activity intervention on screen time at any point in time.

Additional coefficients in this model indicated that women (γ = −0.25) and participants with strong social desirability scores (γ = −0.35) reported less screen time. Participants who reduced the duration of daily screen time in the half-goal phase reduced screen time duration during the full-intervention phase (cov = 0.08). Likewise, participants who reduced daily screen time duration in the full-intervention phase also reduced screen time duration in the follow-up phase (cov = 0.04). Changes in screen time duration during the half-goal phase were not associated with changes in the follow-up phase. At the within-person level, participants reported less screen time during the half-goal (γ = −0.39), full-goal (γ = −0.48) and follow-up phases (γ = −0.32; compared to baseline) and from Monday through Saturday (γ ≤ −0.09; compared to Sunday).

Summary of screen time effects

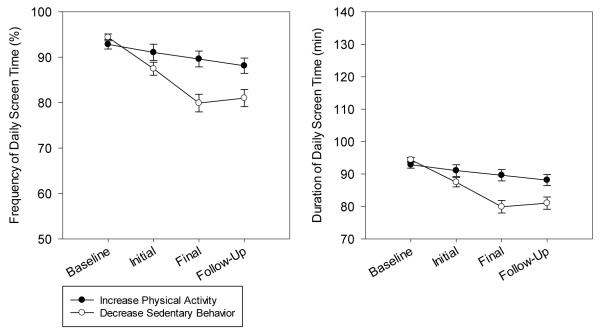

Figure 2 presents observed data on daily leisure screen time frequency and duration for the groups assigned to reduce screen time and increase physical activity. These plots illustrate that the screen time intervention both reduced the frequency (~15% reduction by the full-goal phase) and duration (~50% reduction during the full-goal phase) of daily screen time.

Figure 2.

Observed frequency (left panel) and duration (right panel) of leisure screen time for s assigned to increase physical activity and reduce screen time.

Discussion

The Make Better Choices study established the effects of lifestyle behavior interventions on both daily MVPA and daily leisure screen time. This study was novel in its use of daily outcome data to differentiate between the frequency and duration of each targeted activity behavior. The frequency of daily MVPA increased for participants exposed to the intervention designed to increase lifestyle MVPA, and these effects were maintained over 20 weeks after the end of the intervention, even after incentives based on goal attainment were stopped. Prioritizing increased frequency over intensity or duration is an ideal strategy for initiating increased physical activity because it minimizes the risk of adverse events (Powell, Paluch, & Blair, 2011). Frequency is commonly interpreted as an indicator of exercise adherence (Bollen, Dean, Siegert, Howe, & Goodwin, 2014). When the behavior is performed in a consistent context, behavioral frequency also contributes to habit formation (Wood, Quinn, & Kashy, 2002). Increasing the frequency of regular MVPA may serve as a high-priority behavior change outcome because it offer a means to establish habits and maintain initial behavior changes.

The duration of daily physical activity increased slightly during the full-goal phase; however, similar change occurred for the group targeting reduced sedentary behavior. We concluded that the intervention did not increase daily physical activity duration. As shown in Figure 1, when participants reported physical activity during the baseline phase, they reported durations around 100 min/day, which is well in excess of the 60 min/day intervention target. In hindsight, the 60 min/day goal would not be expected to increase duration. Goal setting is most effective when the aspirational level for behavior is moderately high (McEwan et al., 2015). Participants in the current trial may have needed a goal >100 minutes/day to see an increase in duration, yet it is fair to question whether it would even be desirable to increase the duration of daily MVPA given that such change could have the unintended consequence of increasing risk for adverse events (Powell et al., 2011). The present intervention employed a prudent approach by increasing frequency so participants had an opportunity to adapt to the increased training load. Future work should draw on baseline assessments to tailor goals based on established individual behavioral patterns and ensure safety of such goals.

The analytic approach applied here distinguished between two components of behavioral volume – frequency and duration. This analytic innovation revealed the specific behavioral adaptations made in response to the lifestyle interventions – adaptations which have historically been poorly understood despite their relevance for learning how to prescribe exercise regimens that optimize dose-response relations with health outcomes. For example, a recent review indicated that increasing the frequency of MVPA consistently increases energy expenditure and weight loss whereas the effects of increasing the duration of MVPA are more equivocal (J. Li, O’Connor, Zhou, & Campbell, 2014). Likewise, increased frequency of MVPA has been associated with decreased systemic inflammation whereas the increased physical activity duration has not (Loprinzi, Lee, & Cardinal, 2014). Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that bout duration is not associated with cardiometabolic risk (Loprinzi & Cardinal, 2013). Thus, the intervention that this study implemented to increase physical activity appears to be well-positioned to achieve several valuable health impacts because it stimulated an enduring increase in the frequency of MVPA. The observed effects were sufficient to move a person who was engaging in 30 min/week of MVPA to satisfying the aerobic activity requirements in national guidelines. At the risk of extrapolating well beyond our data, meta-analyses on dose-response relations between physical activity and health outcomes indicate that a person who previously engaged in 30 min/week of MVPA could significantly reduce their risk for diabetes, heart failure, coronary heart disease, all-cause cardiovascular mortality, and cancer mortality if they maintained the behavior change engendered by this intervention (Aune, Norat, Leitzmann, Tonstad, & Vatten, 2015; T. Li et al., 2015; Nocon et al., 2008; Pandey et al., 2015; Sattelmair et al., 2011). The analytic strategy applied to model frequency and duration was appropriate for daily moderate-vigorous physical activity because of its zero-inflated distribution. This strategy may be less relevant for modeling daily light physical activity which is more likely to be normally distributed.

Leisure screen time is a major component of adults’ non-obligatory sedentary behavior (Owen et al., 2011; Tudor-Locke, Johnson, & Katzmarzyk, 2010). The intervention to reduce leisure screen time was effective in reducing both the frequency and duration of leisure screen time. Relative to baseline, these intervention effects were evident across the entire intervention period and into the follow-up assessments even after participants stopped receiving incentives for reaching their goals. Previous work has focused on the total duration of sedentary time without distinguishing the daily patterns of behavior (Martin et al., 2015). This study extends the literature by clarifying the manner in which participants adapted their leisure screen time in response to a lifestyle intervention.

All participants were assigned to receive an intervention intended either to increase their MVPA or to reduce their leisure screen time. Since there was no inactive control group, it is important to consider whether the sedentary behavior intervention may have influenced the physical activity outcomes or vice versa. That is unlikely because neither analyses of the MBC trial data (Schneider et al., in press; Spring, Schneider, et al., 2012) nor findings by others (Owen, Healy, Matthews, & Dunstan, 2010) revealed evidence that physical activity substitutes for sedentary behavior or vice versa. Time that would have been allocated to leisure screen time is more likely to be re-allocated to light physical activity than to MVPA. It remains possible that as decreasing sedentary leisure increases light physical activity, the expected path of behavioral substitution, increased light physical activity may prove to be a gateway toward future increases in MVPA. To date, this gateway hypothesis has received little attention.

Neither dietary intervention had any effect on MVPA or leisure screen time. Even though change in untargeted health behaviors as a consequence of change in behaviors targeted by an intervention is a robust phenomenon (Spring, Moller, et al., 2012); these results suggest that the dietary changes targeted here did not spillover to impact non-dietary outcomes. Further work is needed to identify optimal behavior change goal bundles that enable interventions to maximize positive complementary and substitutive behavior changes to improve health.

This study has some noteworthy limitations. First, the outcome measure was self-reported and that method is vulnerable to threats from both social desirability and cognitive biases (particularly with payments contingent on goal attainment in the intervention phase). Although a bogus pipeline was instituted in the design to reduce the threat of social desirability it is unknown how effectively this feature minimized bias. The threat of cognitive biases was partly controlled by modeling within-person responses to the interventions; however, future work with objective outcome measures would be valuable. Notwithstanding these threats, the maintenance of behavior change in the follow-up period when payments were solely based on data submission strengthens our confidence in results from the intervention phase. Second, many additional aspects of physical activity were not captured by the outcomes of activity frequency and duration. Additional complexities of physical activity behavior that warrant investigation include activity type, whether the activity was accumulated in single or multiple bouts throughout the day, light physical activity, and total energy expenditure. Understanding how these characteristics change in response to a lifestyle intervention would be valuable in future research. Third, although this study provided detailed insight into how people adapt their behavior to a lifestyle intervention, it did not reveal how physical health is affected by the observed behavior changes. Specifically, it is not clear whether the increased frequency of MVPA or the decreased frequency and duration of leisure screen time produced by the interventions translated into clinically-meaningful changes in biomedical outcomes. Fourth, even though both activity interventions were efficacious in changing behavior, it was not clear which intervention components drove those effects. It is possible that some intervention components (e.g., graduated goal-setting, self-monitoring, behavioral feedback, efficacy enhancement, financial incentives) were inert and could be removed to reduce cost or burden in future implementations without reducing the magnitude of behavior change. Finally, the financial incentives used to engage participants in behavior change were not extravagant in relation to many current employee wellness incentives but they may nevertheless not be feasible in all contexts. Moreover, if deployed in a controlling manner, these incentives may crowd out or undermine intrinsic motivation and reduce maintenance of health behavior change.

In sum, this study provided new insights into how people adapt their behavior in response to a lifestyle intervention by illuminating the ways in which participants responded to the interventions on a daily basis. The Make Better Choices interventions increased the frequency (but not duration) of MVPA and decreased both the frequency and duration of leisure screen time. Behavior change was maintained, albeit it at a somewhat attenuated level, through the 20-week follow-up assessment. These results lead to the conclusion that the interventions were efficacious for stimulating long-lasting lifestyle behavior change while minimizing risk.

Acknowledgments

The Make Better Choices trial was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant HL075451 (Dr Spring), K07 CA154862-01 (Dr Siddique), and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center grant (NIH P30 CA060553). Support was also provided through the computational resources and staff contributions provided for the Social Sciences Computing cluster (SSCC) at Northwestern University. Recurring funding for the SSCC is provided by Office of the President, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Kellogg School of Management, the School of Professional Studies, and Northwestern University Information Technology.

Contributor Information

David E. Conroy, Department of Kinesiology, The Pennsylvania State University

Donald Hedeker, University of Chicago.

H. Gene McFadden, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University.

Christine A. Pellegrini, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University

Angela F. Pfammatter, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University

Siobhan M. Phillips, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University

Juned Siddique, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University.

Bonnie Spring, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University.

References

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aune D, Norat T, Leitzmann M, Tonstad S, Vatten L. Physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;30(7):529–542. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0056-z. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-0056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. http://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162(2):123–132. doi: 10.7326/M14-1651. http://doi.org/10.7326/M14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen JC, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, Howe TE, Goodwin VA. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005044. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Schoenborn CA, Loustalot F. Trend and prevalence estimates based on the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.06.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Control theory: a useful conceptual framework for personality-social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92(1):111–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy DE, Elavsky S, Maher JP, Doerksen SE. A daily process analysis of intentions and physical activity in college students. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2013;35:493–502. doi: 10.1123/jsep.35.5.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy DE, Maher JP, Elavsky S, Hyde AL, Doerksen SE. Sedentary behavior as a daily process regulated by habits and intentions. Health Psychology. 2013;32:1149–1157. doi: 10.1037/a0031629. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0031629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles EL, Robalino S, McColl E, Sniehotta FF, Adams J. The effectiveness of financial incentives for health behaviour change: systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2014;9(3):e90347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090347. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles EL, Robalino S, Sniehotta FF, Adams J, McColl E. Acceptability of financial incentives for encouraging uptake of healthy behaviours: A critical review using systematic methods. Preventive Medicine. 2015;73:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.029. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich SB, Anderson DR, Koland H. Impact of financial incentives on behavior change program participation and risk reduction in worksite health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP. 2012;27(2):119–122. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110726-ARB-295. http://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.110726-ARB-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, O’Connor LE, Zhou J, Campbell WW. Exercise patterns, ingestive behaviors, and energy balance. Physiology & Behavior. 2014;134:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.04.023. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Wei S, Shi Y, Pang S, Qin Q, Yin J, Liu L. The dose–response effect of physical activity on cancer mortality: findings from 71 prospective cohort studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094927. bjsports-2015-094927. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ. Association between biologic outcomes and objectively measured physical activity accumulated in ≥ 10-minute bouts and <10-minute bouts. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP. 2013;27(3):143–151. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110916-QUAN-348. http://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.110916-QUAN-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loprinzi PD, Lee H, Cardinal BJ. Daily movement patterns and biological markers among adults in the United States. Preventive Medicine. 2014;60:128–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzari E, Vogt F, Shemilt I, Wei Y, Higgins JPT, Marteau TM. Personal financial incentives for changing habitual health-related behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2015;75:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Fitzsimons C, Jepson R, Saunders DH, Ploeg H. P. van der, Teixeira PJ, Consortium, on behalf of the E Interventions with potential to reduce sedentary time in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094524. bjsports-2014-094524. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, Troiano RP. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. http://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan D, Harden SM, Zumbo BD, Sylvester BD, Kaulius M, Ruissen GR, Beauchamp MR. The effectiveness of multi-component goal setting interventions for changing physical activity behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review. 2015:1–22. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1104258. http://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1104258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychology. 2009;28(6):690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0016136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MS, Goodman JM, Alter DA, John LK, Oh PI, Pakosh MT, Faulkner GE. Financial incentives for exercise adherence in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45(5):658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocon M, Hiemann T, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Thalau F, Roll S, Willich SN. Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation: Official Journal of the European Society of Cardiology, Working Groups on Epidemiology & Prevention and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology. 2008;15(3):239–246. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f55e09. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f55e09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:730–745. [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2010;38(3):105–113. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. http://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Sugiyama T, Eakin EE, Gardiner PA, Tremblay MS, Sallis JF. Adults’ sedentary behavior determinants and interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.013. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Garg S, Khunger M, Darden D, Ayers C, Kumbhani DJ, Berry JD. Dose Response Relationship Between Physical Activity and Risk of Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis. Circulation. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015853. CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015853. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KE, Paluch AE, Blair SN. Physical activity for health: What kind? How much? How intense? On top of what? Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32:349–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101151. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende L. F. M. de, Rodrigues Lopes M, Rey-López JP, Matsudo VKR, Luiz O. do C. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: An overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105620. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roese NJ, Jamieson DW. Twenty years of bogus pipeline research: A critical review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(2):363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohl HW, Haskell W, Lee I-M. Dose Response Between Physical Activity and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation. 2011 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.010710. CIRCULATIONAHA.110.010710. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.010710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KL, Coons MJ, McFadden HG, Pellegrini CA, DeMott A, Siddique J, Spring B. Mechanisms of change in diet and activity in the Make Better Choices 1 trial. Health Psychology. doi: 10.1037/hea0000333. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. SAGE; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, King AC, Pagoto SL, Van Horn L, Fisher JD. Fostering multiple healthy lifestyle behaviors for primary prevention of cancer. The American Psychologist. 2015;70(2):75–90. doi: 10.1037/a0038806. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0038806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Moller AC, Colangelo LA, Siddique J, Roehrig M, Daviglus ML, Liu K. Healthy lifestyle change and subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2014;130(1):10–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005445. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Moller AC, Coons MJ. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England) 2012;34(Suppl 1):i3–10. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr111. http://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Schneider K, McFadden HG, Vaughn J, Kozak AT, Smith M, Hedeker D. Make Better Choices (MBC): study design of a randomized controlled trial testing optimal technology-supported change in multiple diet and physical activity risk behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:586. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-586. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Schneider K, McFadden HG, Vaughn J, Kozak AT, Smith M, Lloyd-Jones DM. Multiple behavior changes in diet and activity: a randomized controlled trial using mobile technology. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(10):789–796. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1044. http://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. http://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT. Frequently reported activities by intensity for U. S. adults: the American Time Use Survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(4):e13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK. Behavior matters: The relevance, impact, and reach of behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9672-1. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9672-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, Quinn JM, Kashy DA. Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(6):1281–1297. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]