Abstract

Tourists consider many factors, including health, when choosing travel destinations. The potential for exposure to novel or foreign diseases alone can deter travelers from selecting high-risk locations for disease transmission. The 2015–2016 Zika Virus (ZIKV) outbreak in the Americas and Caribbean prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. This study investigated factors that may contribute to travel avoidance to areas experiencing ZIKV transmission while also considering different levels of health concern and awareness among groups with varying demographics. An online survey was administered February 10–12, 2016 to a sample of U.S. residents (n = 964). Demographics, information about travel behaviors, and levels of health concern were collected. Ordered logit models were employed to assess the impacts of the ZIKV outbreak on travel planning. Respondents giving higher levels of attention to general health were more likely to avoid travel to areas experiencing ZIKV transmission. It is anticipated that the findings of this study may be of interest to public health officials, healthcare providers, and government officials attempting to mitigate impacts of ZIKV. Disease outbreaks in regions of the world typically frequented by vacation or leisure travelers are particularly problematic due to the increased amount of exposure to disease in an immunologically naïve population that may then contribute to the outbreak through their travel plans. Avoiding travel to destinations experiencing outbreaks of disease due to health concerns may be interpreted positively by the public health community but can have negative economic consequences.

Keywords: Public health, Zika virus, ZIKV, Travel plans, Public perceptions

Highlights

-

•

High levels of ZIKV awareness, but little done to prevent mosquito bites.

-

•

Travelers tended to be more concerned about health than non-travelers were.

-

•

ZIKV-related travel avoidance increased for those with children.

-

•

ZIKV-related travel avoidance increased for those from unaffected regions.

1. Introduction

Personal health has long been recognized as a consideration, or risk factor, for travelers. Concerns include increased exposure to common cold and flu viruses on public transportation or by staying in close quarters with large numbers of people, and locale-specific disease exposure which may not exist in one's home country or region. Depending on the specific destination, health impacts from disease vectors, like mosquitoes, may be a problem (or concern) for even experienced and educated travelers. And, perhaps least mentioned but widespread in impact, are concerns about maintaining physical fitness and obtaining regular exercise. Efforts to cater to health-conscious travels have driven investment in gyms, fitness equipment, and personal health services by many hotels, resorts, and even modes of transportation – like cruise ships.

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2015) tourism worldwide contributes 9% of the total GDP (including direct, indirect, and induced impacts). Over half of the total travel reported in 2014 was for the purpose of leisure, recreation, and holidays (UNWTO, 2015). The Americas was the fastest growing region for tourism in 2014 (UNWTO, 2015). “The Americas (+ 8%) saw the highest relative growth across all world regions in 2014, welcoming 13 million more international tourists, increasing the total to 181 million arrivals. International tourism receipts in the region reached US$ 274 billion in one year, an increase of 3% in real terms. The region increased its share of worldwide arrivals to 16%, while its share of receipts was 22%.” (UNWTO, 2015).

1.1. ZIKV in 2016

ZIKV was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) in February 2016 following reports of a widespread epidemic in the Americas and Caribbean (Petersen et al., 2016). The mosquito-borne arbovirus was first isolated in Africa in 1947 (Dick et al., 1952), but ZIKV was not recognized as important in terms of human health impact until the ZIKV disease outbreak on Yap Island in the Federated States of Micronesia in 2007 (Duffy et al., 2009). Though most of the population of Yap were infected by ZIKV, only mild symptoms of disease were reported, primarily fever, headache, and rash (Duffy et al., 2009).

In 2013 a ZIKV outbreak occurred in French Polynesia that resulted in 29,000 suspected cases of disease (Ioos et al., 2014) and a subsequent increase in cases of an auto-immune disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis (Willison et al., 2016). ZIKV continued to spread to other Pacific Islands from 2013 to 2014 (Musso, 2015) and was first detected in Brazil in early 2015 (Campos et al., 2015). The majority of patients with ZIKV infections have no clinical signs of disease. When symptoms do manifest they are most commonly reported to be similar to signs of other arboviral infections, such as rash (90%), arthritis or arthralgia (65%), fever (65%), conjunctivitis (55%), myalgia (48%), headache (45%), and retro-orbital pain (39%) (Buathong et al., 2015). However, more severe clinical signs have been associated with the ZIKV epidemic in Brazil, notably a drastic increase in the number of microcephaly cases detected in fetuses and newborns (Broutet et al., 2016) as well as death of a limited number of patients (Arzuza-Ortega et al., 2016, Sarmiento-Ospina et al., 2016). It is speculated ZIKV induces brain injury in the fetus that results in cell death and brain shrinkage which ultimately results in the diagnosis of microcephaly, which may result in impaired cognitive development.

1.2. Health concerns and travel in 2016

The intersection between health concerns and travel is especially apparent during disease outbreaks. Disease outbreaks in regions of the world typically frequented by vacation or leisure travelers may be problematic from an economic standpoint if travel to such destinations is avoided, which is precisely what is recommended by public health officials. Most tourists visit destinations within their own region (UNWTO, 2015), making the Caribbean a sought after destination for visitors from the Americas. Arrivals in the Caribbean were up 6% overall where several locations, including Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, Grenada, Haiti, and the Cayman Islands, all posted doubled-digit increases in arrival numbers (UNWTO, 2015). ZIKV remains a worldwide concern as people travel to/from popular destinations that are within impact zones; one recent example was concern over travel to the 2016 Olympic Games.

Health when traveling has been a long discussed topic which has received attention from the travel industry, health professionals, and marketers. In recent years the growth in travel across the Americas (and specifically in the Caribbean) has intersected the ZIKV outbreak currently being experienced. The objectives of this paper are to (1) examine levels of health concern and awareness across demographics, (2) measure ZIKV awareness across various groups of respondents, and (3) investigate factors that may contribute to travel avoidance to various locales experiencing ZIKV transmission. Improved understanding of the potential relationships between demographics and health concerns of travelers, perceptions of ZIKV, and impacts on travel plans are important for the economies of the Caribbean which depend on tourism, as well as health officials within and outside the region as they seek to address the ZIKV outbreak.

2. Data and methods

An online survey with two focus areas, health concern (assessed as an individual's stated level of concern about seven key health issues) and travel, was administered on February 10th through the 12th, 2016. Respondents were identified and contacted through the use of a large opt-in panel database maintained by Lightspeed, GMI. Respondents were targeted to be representative of the U.S. population in terms of gender, income, education, and geographical region of residence according to the U.S. Census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014) and were required to be 18 years of age or older to participate. In total 964 respondents participated in the survey.

In addition to basic demographics, respondents were asked about their recent travel behaviors as well as their level of concern for seven areas of health. Specific to travel intentions, respondents were asked about their likelihood to avoid travel to Florida, Texas, Puerto Rico, and Caribbean Islands in the next 12 months. The Caribbean and Puerto Rico were selected for study based on their challenges with the recent ZIKV outbreak, while Florida and Texas were included given their proximity to the outbreak area and potential for eventual concern regarding ZIKV. The seven areas surrounding health concern investigated were physical fitness, heart health, mental health, cancer, flu, antibiotic resistant bacterial infection, and prenatal care. Precisely, respondents were asked, On a scale of one (I do not give any thought to this at all) to five (I think about this constantly), please rank the level of attention or thought you provide to the following aspects of health and well-being. Please select the number on the scale that best represents your level of attention. Three categories of health valuation were developed based on responses received, specifically “Does not think about often” represents respondents who gave a rank of 1 or 2, “Thinks about some of the time,” are those who gave a rank of 3 and “Thinks about often/constantly” represents those who gave a rank of 4 or 5.

Finally, given the intended focus of this analysis on the intersection of health and travel, the current ZIKV outbreak (2016) was a specific health focus of this analysis. Respondents were asked about their ZIKV awareness, knowledge about the virus and its symptoms, and the prevention measures taken by respondents' households.

Basic summary statistics to questions about respondent demographics, household behaviors surrounding travel, mosquito-borne disease transmission prevention measures, travel experiences, and concern about health factors were completed. Cross tabulations are employed in this analysis to analyze relationships between health concerns and travel.

2.1. Ordered logit model

Given the focus of this analysis on assessing the potential impacts of the ZIKV outbreak on travel planning, in particular to affected regions, four ordered logit models were estimated to identify factors related to stated intentions to avoid travel to four different locations: Florida, Texas, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean. The models were based on the question At this point in time, how likely are you to avoid travel to the following locations in the coming 12 months due to concerns about the Zika virus on the provided scale of ONE to FIVE? An ordered logit uses the ranked categories of the Likert scale to create thresholds (Baum, 2006). In this instance the dependent variable y was established as an ordered categorical dependent variable, with the values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 as the ranked (in order of likeliness to avoid, on a scale of one to five) categories. Using k to represent thresholds, a rank would be established in the following way If y∗ < k1 then y = 1 , If k1 < y∗ < k2 then y = 2 and so on until If k4 < y∗ then y = 5 and y⁎ is a latent variable (Baum, 2006). The probability of each rank outcome j can then be estimated Pr(yi = j) = Pr (kj − 1 < βXi + ui < kj) (Baum, 2006). This states that the probability of a particular outcome j being chosen is dependent on βXi falling between threshold kj and kj-1 for each individual (Baum, 2006). The coefficients from this estimate provide the direction of change and significance but not the magnitude.

A number of dummy variables (two value categorical variables) were incorporated as explanatory variables in the ordered logit models. Male was a dummy where (1) represents being male. Two of the three age groups, Age 18 to 34 and Age 35 to 54 were used in the model, while the third category Age 55 to 88 was the referent group. Region and income were treated similarly with dummy variables created for the Midwest, South, and North regions and the West being the referent. Low income, and High income were included in the logit model as dummy variables (both relative to Medium income which was the referent). Education was accounted for by the creation of a two category (dummy) variable which was (1) for those respondents having obtained a college degree and (0) for those who had not. Respondent's level of health concern (or thought devoted to health factors) was summed across the seven health categories investigated (physical fitness, heart health, mental health, cancer, flu, antibiotic resistant bacterial infection, and prenatal care) to create the only continuous explanatory variable in the model.1

3. Results and discussion

A total of 964 respondents were identified and contacted through the use of a large opt-in panel database between February 10th and 12th, 2016. Data on respondents' stated health concerns, travel behaviors, and travel intentions were collected. Summary statistics and demographics are presented in Table 1. The sample was comprised of approximately half male and half female respondents. Just under half of respondents had household incomes of less than $50,000 annually and 59% had obtained a college degree (or the equivalent). The majority of the sample have no children in the household. Given the heightened concern surrounding ZIKV for pregnant women, pregnancy intentions were requested from respondents. A total of 4% of respondents were pregnant at the time they responded to the survey while another 5% indicated a household member was currently pregnant.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics (% of respondents; n = 964).

| Variable description | % of respondents n = 964 | % of those who have personally traveled more than five hours from home within the U.S. in the last 12 months n = 597 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 47 | 49 |

| Female | 53 | 51 |

| Age | ||

| 18 to 34 | 28 | 36 |

| 35 to 54 | 38 | 36 |

| 55 to 88 | 34 | 28 |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 23 | 22 |

| South | 35 | 35 |

| West | 23 | 24 |

| Northeast | 19 | 19 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 48 | 35 |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 19 | 21 |

| $75,001 or more | 33 | 44 |

| Education | ||

| Has not obtained a college degree or the equivalent | 41 | 33 |

| Has obtained a college degree or the equivalent | 59 | 67 |

| Children in household: at least one of | ||

| Age 0 to 4 years | 11 | 19 |

| Age 5 to 10 years | 19 | 36 |

| Age 11 to 15 years | 17 | 27 |

| Age 16 to 18 years | 08 | 13 |

| Pregnancy intentions | ||

| I am currently pregnant | 04 | |

| Someone else in my household is pregnant | 05 | |

| There has been a pregnancy in my household in the last 3 years | 05 | |

| Someone intends to become pregnant in the next 1 year | 05 | |

| Someone intends to become pregnant in the next 2–3 years | 06 | |

| Not applicable to me | 80 |

The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

Given the focus of this analysis on the intersection of health (including perceptions of ZIKV) with participation in travel, Table 1 also presents demographics for the subsample of respondents who have personally traveled more than five hours from home within the U.S. in the last 12 months. Looking specifically at the subsample of travelers (n = 597), the youngest age bracket of respondents made up only 28% of the sample overall, but 36% of travelers. While households with income of less than $50,000 annually made up nearly 50% of the sample overall, they comprised only 35% of the travelers subset.

3.1. Reported health concerns and travel experience

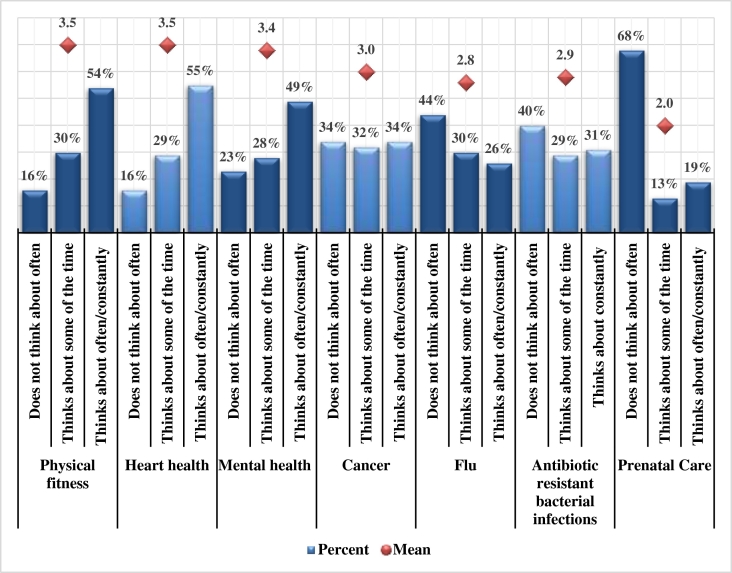

Fig. 1 details responses by respondents across three categories, namely “does not think about often”, “thinks about some of the time”, and “thinks about often/constantly” as well as providing the mean value for each of the seven areas of health studied. In total, respondents reported that they think about often/constantly physical fitness and heart health, followed by mental health. Mean values across all respondents also highlighted these three areas of health as the most highly ranked in terms of attention paid to these areas by respondents. Given prenatal care is a concern for only a segment of the population, it is not surprising that this was the lowest mean category (68% of respondents did not think about it often) across the sample as a whole.

Fig. 1.

Summary of respondents' reported levels of health concerns (n = 964, % of respondents). This summary is based on a five-point Likert scale question in which one was I do not give this any thought, and five was I think about this constantly. The lower options, 1 and 2 were combined into Does not thing about often, option 3 is things about some of the time, and the upper option, 4 and 5, were combined to Thinks about often/constantly. The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

In total 61.9% of the total sample of respondents had traveled > 5 h from home in the 12 months preceding the survey. In the year preceding the survey, 14% of respondents had traveled by cruise ship, 42% via domestic air travel (within the U.S.), 22% via international air travel (outside the U.S.), 47% on a “road trip” of > 5 h in a private vehicle, 20% via public bus, and 15% by train. Specifically looking at travel outside the U.S. in the 12 months before the survey, 28% of respondents indicated they had traveled outside the U.S., while 15% indicated another adult household member had, and 6% indicated a child household member had. In total, 68% of those sampled had not traveled nor had another adult or child in their household traveled outside the U.S. in the past 12 months. Given the focus on the Caribbean region, further analysis into modes of travel, including cruise ships, were conducted. Of those traveling by cruise ship in the past 12 months, 65.2% earn $75,001 or more annually, 80.7% have a college degree, and 57.0% have at least one child in the household. Looking specifically at those who have traveled by air internationally in the past year, 61.5% earn $75,001 or more annually, 87.2% have a college degree, and 56.7% have at least one child in the household.

A total of 22% of respondents had visited the Caribbean in the 2 years preceding the survey. Ten percent of households had an adult member of their household travel to the Caribbean in the 24 months leading up to the survey, while only 3% indicated a child household member had. Thus, 76% of those sampled had not traveled nor had another adult or child in their household traveled to the Caribbean in the past 24 months.

Of those who had visited the Caribbean in the past 2 years, 64.2% are male, 42.0% are 18 to 34 years of age, 63.7% earn more than $75,001 annually, 79.7% have a college degree, and 63.2% have at least one child living in the household. Of respondents who reportedly had a child household member visit the Caribbean in the past 24 months, most were under the age of 55 to 88 (56.7% were 18 to 34; 40.0% were 35 to 54; and only 3.3% were 55 to 88 years of age), 83.3% earn more than $75,001 annually, and 90.0% have a college degree.

Cross tabulations of levels of reported concern about each of the seven focused upon health areas and age, region, income, education, travel experience, and whether or not children were present in the household are presented in Table 2. Of those respondents who reported that they think about physical fitness often/constantly, 35.6% were 18 to 34 years of age, 68.6% have a college degree, 71.6% have traveled in the past year, 55.7% have no children living in the household, and 58.1% were female. Mental health concern tended to be less often reported in the older age bracket studied. Of those were who reported often/constant thought to mental health, 70.1% had traveled in the past year, and 56.1% had no children living in the household. Cancer, flu, antibiotic resistant bacterial infections, and prenatal care all continue to display similar trends in that > 65% of those reporting high levels of attention to these concerns have traveled in the past 12 months. Not surprisingly, of those reporting high attention to prenatal care, 76% had children in the household. Perhaps more surprisingly, of those thinking often about prenatal care 83.8% had traveled in the past 12 months. Given the risks for pregnant women with ZIKV, the overlap between prenatal care attention/concern and travel is of particular interest in this analysis.

Table 2.

Cross tabulations of respondent demographics and responses to level of concern for personal health (% of respondents; n = 964).

| Age |

Region |

Income |

Education |

Traveled > 5 h from home in last 12 months |

Children in the household |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 34 | 35 to 54 | 55 to 88 | Midwest | South | West | Northeast | Less than $50,000 | $50,001–$75,000 | $75,001 or more | No college degree | Obtained college degree | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Physical fitness | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 18.4a | 39.9b | 41.8b | 27.8a | 36.1ab | 17.7b | 18.4ab | 64.6a | 17.1b | 18.4c | 58.9a | 41.4b | 59.5a | 40.5b | 71.5a | 28.5b |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 35.6a | 37.9b | 26.4c | 20.9a | 34.3ab | 24.3ab | 20.5b | 39.5a | 21.3b | 39.3b | 31.4a | 68.6b | 28.4a | 71.6b | 55.7a | 44.3b |

| Heart health | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 34.6a | 35.9ab | 29.4b | 24.2a | 37.3a | 18.3a | 20.3a | 60.8a | 20.3a | 19.0b | 47.1a | 52.9a | 51.6a | 48.4b | 67.3a | 32.7a |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 27.8a | 36.7a | 35.5a | 20.2a | 35.5ab | 23.8b | 20.4b | 41.6a | 18.7a | 39.7b | 35.9a | 64.1b | 31.8a | 68.2b | 58.6a | 52.4b |

| Mental health | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 18.3a | 37.9b | 43.8b | 23.7a | 34.2a | 21.9a | 20.1a | 54.3a | 19.6ab | 26.0b | 42.9a | 57.1a | 47.5a | 52.5b | 75.8a | 24.2b |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 36.1a | 36.3b | 27.6c | 20.6a | 35.9ab | 23.1ab | 20.4b | 44.6a | 19.5ab | 35.9b | 38.0a | 62.0a | 29.9a | 70.1b | 56.1a | 43.9b |

| Cancer | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 26.4a | 39.0a | 34.7a | 22.1a | 37.4a | 22.1a | 18.4a | 53.7a | 19.3ab | 27.0b | 41.1a | 58.9a | 46.a | 54.0b | 67.2a | 32.8a |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 32.4a | 34.6b | 33ab | 19.9a | 34.9ab | 23.9ab | 21.4b | 41.9a | 16.2a | 41.9b | 37.6a | 62.4a | 31.2a | 68.8b | 54.7a | 45.3b |

| Flu | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 21.9a | 38.2b | 39.9b | 23.3a | 35.9a | 23.3a | 18.5a | 53.7a | 18.8ab | 27.6b | 40.9a | 59.1a | 44.7a | 55.3b | 73.6a | 26.4b |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 41.3a | 36.6b | 22.0c | 17.3a | 37.2bc | 21.3ac | 24.0b | 39.0a | 15.7a | 45.3b | 36.2a | 63.8a | 25.2a | 74.8b | 41.7a | 58.3b |

| Antibiotic resistant bacterial infections | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 24.5a | 36.9ab | 3.87b | 24.5a | 33.2a | 24.5a | 17.8a | 54.9a | 17.0b | 28.1b | 42.8a | 57.2a | 47.7a | 52.3b | 73.2a | 26.8b |

| Thinks about constantly | 36.9a | 36.3b | 26.8b | 16.9a | 38.6b | 22.7ab | 21.7b | 40.7a | 16.6a | 42.7b | 36.9a | 63.1a | 30.2a | 69.8b | 48.1a | 51.9b |

| Prenatal care | ||||||||||||||||

| Does not think about often | 15.8a | 38.5b | 48.8c | 25.6a | 36.4ab | 20.2c | 17.9bc | 53.9a | 17.6b | 28.5b | 44.5a | 55.5b | 44.4a | 55.6b | 76.8a | 23.2b |

| Thinks about often/constantly | 59.8a | 31.4b | 6.1c | 11.7a | 31.8b | 31.3c | 25.1c | 25.7a | 20.7b | 53.6c | 24.6a | 75.4b | 16.2a | 83.8b | 24.0a | 76.0b |

Statistically, a is different from b and c, and b, from c and a, and c from b and a. The central health evaluation “Thinks about some of the time” has been omitted for brevity. Values for Female and Male were not provided because there was no significant differences except for in two case: Physical fitness “Thinks about some of the time”: Male 41.9% is different from 58.1% for Female and Prenatal Care “Thinks about often/constantly” 56.4% for male is different form 43.6% for female. No other difference existed between the two. The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

3.2. ZIKV outbreak information and impacts

Eighty-four percent of respondents were aware of the ZIKV outbreak at the time of the survey, but only 30% were aware of the CDC recommendation to postpone travel to places where transmission was taking place. Fig. 2 displays an infographic summarizing respondent's general knowledge about ZIKV and its symptoms, as well as the mosquito bite prevention steps being used. While nearly half of respondents reported using bug repellant spray, only 22% reported actively removing standing water around their homes. This may suggest a lack of awareness of prevention strategies that are necessary for control of vector-borne diseases such as ZIKV.

Fig. 2.

Zika Awareness Infographic. The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

Table 3 displays ZIKV knowledge and awareness across different demographic groups. Of those who reported awareness of the outbreak, 62.9% had earned a college degree. Of those who reported knowing that ZIKV is spread by the same type of mosquitoes that spread Dengue and Chikungunya, 72.3% had a college degree, 71.3% had traveled, and 50.3% had at least one child in the household. More generally, those who responded as knowing that mosquitoes can spread viruses among humans more often than not (> 60%) had a college degree and had traveled.

Table 3.

Cross tabulations of respondent demographics and reported Zika virus awareness in 2016 (% of respondents; n = 964).

| Age |

Region |

Income |

Education |

Traveled > 5 h from home in last 12 months |

Children in the household |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 34 | 35 to 54 | 55 to 88 | Midwest | South | West | Northeast | Less than $50,000 | $50,001–$75,000 | $75,001 or more | No college degree | Obtained college degree | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| I am aware of the Zika virus outbreak | 25.6a | 36.2a | 38.2b | 22.5a | 35.6a | 23.3a | 18.6a | 45.0a | 19.1b | 35.9b | 37.1a | 62.9b | 36.0a | 64.0b | 65.6a | 34.4a |

| I am aware of the effect on pregnant women | 26.4a | 36.1a | 37.4b | 22.9a | 35.0a | 23.2a | 18.9a | 43.9a | 19.3b | 36.8b | 36.6a | 63.7b | 36.0a | 64.0b | 64.0a | 36.0a |

| Zika details awareness, percent of respondents reporting agreement that: | ||||||||||||||||

| Approximately 1 in 5 people infected with Zika virus will develop Zika and become ill. | 31.6a | 33.0b | 35.4ab | 17.5a | 37.5b | 27.0b | 17.9ab | 34.0a | 19.6b | 46.3c | 27.7a | 72.3b | 24.6a | 75.4b | 52.3a | 47.7b |

| The incubation period for the Zika virus is not known, but is believed to be a few days to a week. | 25.3a | 33.3a | 41.3b | 20.7a | 34.0a | 26.0a | 19.3a | 39.0a | 18.7ab | 42.3b | 32.7a | 67.3b | 32.3a | 67.7b | 59.0a | 41.0b |

| The Zika virus illness is usually mild and lasts for several days to a week. | 25.5a | 32.0a | 42.5b | 21.5a | 32.3a | 25.2a | 20.9a | 35.7a | 20.6b | 43.7b | 31.1a | 68.9b | 28.9a | 71.1b | 62.2a | 37.8a |

| People sick with the Zika virus do not usually get sick enough to go to the hospital. | 18.3a | 34.8b | 47.0c | 25.4a | 33.0a | 21.5a | 20.1a | 41.9a | 16.1a | 41.9b | 34.4a | 65.6b | 34.1a | 65.9a | 67.0a | 33.0a |

| People rarely die of Zika | 23.5a | 32.6a | 43.9b | 22.5a | 33.0a | 22.5a | 22.1a | 39.6a | 18.9ab | 41.4b | 32.3a | 67.7b | 28.4a | 71.6b | 68.4a | 31.6a |

| The CDC in the US has recommended that pregnant women postpone travel to destinations where Zika virus transmission is taking place. | 19.7a | 34.9b | 45.4c | 24.0a | 35.1a | 23.1a | 17.7a | 45.8a | 18.5a | 35.7a | 37.0a | 63.0b | 37.4a | 62.6a | 71.4a | 28.6b |

| There has been at least one known case of sexual transmission of the Zika virus in the US. | 15.8a | 35.5b | 48.8c | 26.8a | 33.7b | 22.7ab | 16.7b | 47a | 20.2a | 32.8a | 38.2a | 61.8a | 39.2a | 60.8a | 74.9a | 25.1b |

| I am not familiar with any of these details. | 32.7a | 40.0a | 27.3b | 24.1a | 38.6a | 18.2a | 19.1a | 67.7a | 12.7b | 19.5b | 61.4a | 38.6b | 50.0a | 50.0b | 70.0a | 30.0b |

| Before survey I was aware | ||||||||||||||||

| The Zika virus is spread by the same type of mosquitoes as spread Dengue and Chikungunya | 35.3a | 39.3b | 25.4c | 19.5a | 35.5ab | 24.9b | 20.1ab | 33.0a | 21.8b | 45.2b | 27.7a | 72.3b | 28.7a | 71.3b | 49.7a | 50.3b |

| The mosquito that spreads the Zika virus bites primarily during the daytime | 34.3a | 39.2a | 26.5b | 20.2a | 35.8a | 23.8a | 20.2a | 38.0a | 21.1b | 41.0b | 31.9a | 68.1b | 31.3a | 68.7b | 51.2a | 48.8b |

| Mosquitoes can spread viruses among humans | 26.5a | 37.7ab | 35.8b | 23.4ab | 36.9b | 22.0ab | 17.6a | 46.1a | 19.7b | 34.2ab | 38.2a | 61.8b | 36.4a | 63.6b | 64.7a | 35.3a |

Statistically, a is different from b and c, and b, from c and a, and c from b and a. Prevention removed. Male and female removed for all rows and were significantly different for the following: I am aware of the Effect on Pregnant Women Male: 45.3a, Female: 54.7b; Approximately 1 in 5 people infected with Zika virus will develop Zika and become ill: Male:53.7a, Female: 46.3b; The Center for Disease Control in the United States has recommended that pregnant women postpone travel to destinations where Zika virus transmission is taking place: Male: 40.6a Female: 59.4b; I am not familiar with any of these details.: Male: 39.4a, Female: 60.6b; Fever: Male: 44.4a, Female: 55.6b; Rash: Male: 41.6a, Female: 58.4b; The Zika virus is spread by the same type of mosquitoes as spread Dengue and Chikungunya Male: 55.8a, Female: 44.2b; The mosquito that spreads the Zika virus bites primarily during the daytime Male: 53.3a, Female: 46.7b. The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

Implications of changing travel plans to the states of Florida and Texas, as well as to Puerto Rico and Caribbean Islands were investigated (Table 4). For both Florida and Texas, having at least one child in the household was associated with being more likely to avoid travel (to these locales) than if there were no children present. In addition, travel was more likely to be avoided if the respondent was from the Midwest region of the U.S. and less likely to be avoided if the respondent was from the South, compared to being from the Western U.S. Potentially most interesting, given the focus upon the intersection of health and travel, was the finding that travel was more likely to be avoided to both Florida and Texas as respondents placed increasing value/attention on their health.

Table 4.

Likelihood of avoiding travel in the next 12 months due to concerns about Zika.

| The State of Florida |

The State of Texas |

Puerto Rico |

Caribbean Islands |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description | Coefficient (SE) | Confidence interval |

Coefficient (SE) | Confidence interval |

Coefficient (SE) | Confidence interval |

Coefficient (SE) | Confidence interval |

||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| age18to34 | 1 = age 18 to 34 | 0.0319 (0.1606) |

− 0.2828 | 0.3467 | 0.0031 (0.1605) |

− 0.3115 | 0.3177 | − 0.4343*** (0.1639) |

− 0.7557 | − 0.1130 | − 0.4238*** (0.1649) |

− 0.7471 | − 0.1004 |

| age35to54 | 1 = age 35 to 54 | 0.1698 (0.1496) |

− 0.1234 | 0.4632 | 0.0053 (0.1507) |

− 0.2900 | 0.3008 | − 0.3206** (0.1537) |

− 0.6218 | − 0.0193 | − 0.3411** (0.1550) |

− 0.6449 | − 0.0372 |

| male | 1 = male | − 0.0049 (0.1172) |

− 0.2348 | 0.2249 | − 0.0279 (0.1167) |

− 0.2567 | 0.2008 | − 0.2168* (0.1186) |

− 0.4494 | 0.0157 | − 0.1738 (0.1193) |

− 0.4077 | 0.0600 |

| childdum | 1 = has at least one child | 0.5520*** (0.1431) |

0.2715 | 0.8325 | 0.4243*** (0.1433) |

0.1434 | 0.7052 | 0.2034 (0.1448) |

− 0.0804 | 0.4874 | 0.2120 (0.1457) |

− 0.0736 | 0.4976 |

| MidwestSTdum | 1 = from the Midwest | − 0.4197** (0.1742) |

− 0.7613 | − 0.0782 | − 0.3240* (0.1726) |

− 0.6624 | 0.0144 | − 0.1383 (0.1764) |

− 0.4841 | 0.2074 | − 0.1938 (0.1764) |

− 0.5398 | 0.1520 |

| SouthSTdum | 1 = from the South | − 0.5820*** (0.1592) |

− 0.8942 | − 0.2698 | − 0.5327*** (0.1593) |

− 0.8449 | − 0.2204 | − 0.2747* (0.1602) |

− 0.5887 | 0.0393 | − 0.1814 (0.1606) |

− 0.4963 | 0.1333 |

| NortheastSTdum | 1 = from the North East | − 0.2278 (0.1791) |

− 0.5789 | 0.1231 | − 0.0513 (0.1779) |

− 0.4000 | 0.2973 | − 0.1951 (0.1812) |

− 0.5504 | 0.1601 | − 0.1410 (0.1830) |

− 0.4997 | 0.2177 |

| Inclow | 1 = income <$50,000 | 0.0144 (0.1605) |

− 0.3001 | 0.3290 | 0.0657 (0.1617) |

− 0.3827 | 0.2512 | − 0.2032 (0.1666) |

− 0.5298 | 0.1232 | − 0.0661 (0.1688) |

− 0.3970 | 0.2648 |

| Inchigh | 1 = income >$75,001 | − 0.1757 (0.1659) |

− 0.5011 | 0.1495 | − 0.1191 (0.1659) |

− 0.4443 | 0.2060 | − 0.5581*** (0.1702) |

− 0.8918 | − 0.2245 | − 0.5442*** (0.1705) |

− 0.8783 | − 0.2100 |

| Degree | 1 = has college degree | − 0.0024 (0.1271) |

− 0.2515 | 0.2466 | − 0.0499 (0.1276) |

− 0.3002 | 0.2002 | − 0.2238* (0.1309) |

− 0.4804 | 0.0327 | − 0.1640 (0.1322) |

− 0.4232 | 0.0951 |

| HealthSum | Valuation of health | 0.0824*** (0.0159) |

0.0512 | 0.1136 | 0.0744*** (0.0158) |

0.0433 | 0.1054 | 0.0621*** (0.0158) |

0.0311 | 0.0311 | 0.0814*** (0.0159) |

0.0501 | 0.1127 |

| Cut one | − 0.4769 (0.2342) |

− 0.7376 (0.2348) |

− 2.0235 (0.2454) |

− 1.7848 (0.2478) |

|||||||||

| Cut two |

0.0812 (0.2332) |

− 0.1548 (0.2336) |

− 1.5495 (0.2416) |

− 1.3046 (0.2439) |

|||||||||

| Cut three |

0.9485 (0.2351) |

0.8696 (0.2354) |

− 0.6311 (0.2379) |

− 0.4022 (0.2409) |

|||||||||

| Cut four |

1.677 (0.2399) |

1.694 (0.2402) |

0.0854 (0.2369) |

0.2506 (0.2407) |

|||||||||

|

PsuedoR2 Prob > Chi2 Log likelihood |

0.0275 0.0000 − 1462.2256 |

0.0216 0.0000 − 1483.7952 |

0.0139 0.0000 − 1416.0743 |

0.0169 0.0000 − 1386.8668 |

|||||||||

Significance is denoted at the 10% level by ⁎, at the 5% level by ⁎⁎, and at the 1% level by ⁎⁎⁎. The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

In addition to Florida and Texas, two other locations were investigated, namely Puerto Rico and Caribbean Islands, each in its own separate model. With respect to the outcomes of these two models, being from the two younger age brackets was associated with being less likely to avoid travel as was being from the higher income bracket (compared to middle income bracket) in this study. In addition, for both models (locations), just as was seen in the models for Florida and Texas, having higher levels of attention paid to health overall was associated with being more likely to avoid travel to these locations. In addition to these factors, three additional significant coefficients resulted from the model analyzing travel avoidance for Puerto Rico; being male was associated with being less likely to avoid travel (compared to being female), as was being from the South (relative to being from the West), and having a college degree (compared to not having a degree).

4. Conclusions and implications

Surprisingly few respondents were taking significant steps to reduce mosquito bites even though recognition of ZIKV and knowledge about the virus and transmission was reasonably high. From a public health perspective, this may indicate a failure to communicate appropriate disease prevention strategies to the U.S. population. Further work should be done to ensure awareness and implementation of vector-borne disease prevention strategies are being suitably employed. Overall travel avoidance to U.S. states for which ZIKV is a concern was increased for those with children, those from regions less likely to be impacted, and those more concerned about their health. Avoidance of travel to Caribbean Islands and Puerto Rico were similar in terms of the contribution of health; increased levels of concern for health were associated with increased levels/likelihood of avoidance of travel to these locations. While the factors contributing to travel avoidance are likely unsurprising, these findings are worrisome given earlier findings in this analysis highlighted that those who have traveled in the past year tended to be concerned about health (as well as have higher education, higher income, and often had children in the household). These findings suggest that travel avoidance is being influenced by precisely those factors which were associated with travelers. In particular, disease outbreaks in regions of the world typically frequented by vacation or leisure travelers may be problematic if travel to such destinations is avoided due to health concerns.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Using the three levels of health evaluation from the Likert scale health question a total health sum was obtained. By summing across all health categories a respondent's score could range from a low valuation of health, a score of 0 for which all categories were Does not think about often, to a very high valuation of health, a score of 14 for which all categories were Thinks about often/constantly.

Contributor Information

Nicole J. Olynk Widmar, Email: nwidmar@purdue.edu.

S.R. Dominick, Email: sdominic@purdue.edu.

Audrey Ruple, Email: aruplecz@purdue.edu.

Wallace E. Tyner, Email: wtyner@purdue.edu.

Appendix A. Zika virus awareness, infographic summary (% of respondents; n = 964)

| Variable description | % of respondents |

|---|---|

| Mosquito prevention | |

| Yes: Bug spray or insect repellent | 49.5 |

| Yes: Clothing with long sleeves or pants specifically for insect bite control | 21.2 |

| Yes: Mosquito nets or other mechanisms | 7.4 |

| Yes: Actively remove standing water around our homes | 21.9 |

| Yes: Insect sprays, foggers, or other products to control mosquito populations in our yard or home | 13.5 |

| No active management | 41.1 |

| Awareness of Zika outbreak | |

| I am aware of the Zika virus outbreak | 83.6 |

| I recall hearing of an outbreak, but do not recall the name of the illness | 7.5 |

| I am not aware of any outbreak | 8.9 |

| Awareness of effect on pregnant women | |

| I am aware | 81.2 |

| I am not aware | 18.8 |

| Zika details awareness | |

| Approximately 1 in 5 people infected with Zika virus will develop Zika and become ill. | 29.6 |

| The incubation period (the time from exposure to symptoms) for the Zika virus is not known, but is believed to be a few days to a week. | 31.1 |

| The Zika virus illness is usually mild and lasts for several days to a week. | 33.7 |

| People sick with the Zika virus do not usually get sick enough to go to the hospital. | 28.9 |

| People rarely die of Zika. | 29.6 |

| The Center for Disease Control in the United States has recommended that pregnant women postpone travel to destinations where Zika virus transmission is taking place. | 29.6 |

| There has been at least one known case of sexual transmission of the Zika virus in the United States. | 42.1 |

| I am not familiar with any of these details. | 22.8 |

| Awareness Zika symptoms | |

| Fever | 66.1 |

| Joint pain | 38.9 |

| Rash | 36.9 |

| Conjunctivitis (red eyes) | 22.8 |

| Sneezing | 16.5 |

| Muscle pain | 41.2 |

| Headache | 44.2 |

| None of these symptoms are associated. | 17.7 |

| Before survey I was aware | |

| The Zika virus is spread by the same type of mosquitoes as spread Dengue and Chikungunya | 40.9 |

| The mosquito that spreads the Zika virus bites primarily during the daytime | 34.4 |

| Mosquitoes can spread viruses among humans | 80.6 |

The data for this analysis was collected via an online survey conducted by Purdue University taking place from February 10th–12th of 2016.

References

- Arzuza-Ortega L., Polo A., Perez-Tatis G. Fatal sickle cell disease and Zika virus infection in girl from Columbia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:925–927. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.151934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum C.F. Stata Press; College Station, TX: 2006. An Introduction to Modern Econometrics Using Stata. [Google Scholar]

- Broutet N., Krauer F., Riesen M. Zika virus as a cause of neurologic disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374(16):1506–1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1602708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buathong R., Hermann L., Thaisomboonsuk B. Detection of Zika virus infection in Thailand, 2012–2014. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;93:380–383. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0022. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos G.S., Bandeira A.C., Sardi S.I. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21(10):1885–1886. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick G.W., Kitchen S.F., Haddow A.J. Zika virus. I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952;46:509–520. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy M.R., Chen T.H., Hancock W.T. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2536–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioos S., Mallet H.P., Leparc Goffart I., Gauthier V., Cardoso T., Herida M. Current Zika virus epidemiology and recent epidemics. Med. Mal. Infect. 2014;44:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso D. Zika virus transmission from French Polynesia to Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:1887. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.151125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen L.R., Jamieson D.J., Powers A.M., Honein M.A. Zika virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1552–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1602113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento-Ospina A., Vasquez-Serna H., Jimenez-Canizales C.E., Villamil-Gomez W.E., Rodriguez-Morales A.J. Zika virus associated deaths in Colombia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30006-8. (pii S1473-3099(16)30006-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010, 2010 Demographic Profile Data. Accessed December 31, 2015 at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DP_DPDP1&prodType=table. (2010 Census, Revised 2014)

- Willison H.J., Jacobs B.C., van Doorn P.A. Guillain–Barre syndrome. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00339-1. (pii S0140-6736(16)00339-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization UNWTO Tourism Highlights. 2015. http://www2.unwto.org/content/why-tourism Edition. Downloaded at.