Abstract

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy enables non-invasive chemical studies of intact living matter. However, the use of NMR at the volume scale typical of microorganisms is hindered by sensitivity limitations, and experiments on single intact organisms have so far been limited to entities having volumes larger than 5 nL. Here we show NMR spectroscopy experiments conducted on single intact ova of 0.1 and 0.5 nL (i.e. 10 to 50 times smaller than previously achieved), thereby reaching the relevant volume scale where life development begins for a broad variety of organisms, humans included. Performing experiments with inductive ultra-compact (1 mm2) single-chip NMR probes, consisting of a low noise transceiver and a multilayer 150 μm planar microcoil, we demonstrate that the achieved limit of detection (about 5 pmol of 1H nuclei) is sufficient to detect endogenous compounds. Our findings suggest that single-chip probes are promising candidates to enable NMR-based study and selection of microscopic entities at biologically relevant volume scales.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a well-established spectroscopic technique widely employed in physics, chemistry, medicine, and biology. It allows for experiments on living matter1,2, whose relevance in biology is proven by developments such as in vivo protein structure determination3, metabolic profiling4, visualization of gene expression5, and latent phenotype characterization6. Despite its advantages, NMR suffers from a significantly lower sensitivity with respect to other methods. As a result, experiments are often restricted to large ensembles of cells1,3,4,6.

Single cell studies are necessary to investigate heterogeneous phenomena within a cell population7,8,9. Recently, a number of techniques were applied to intracellular metabolic profiling at single cell scale, all having different limitations and degree of invasivity. For instance, mass spectrometry and fluorescence labeling allow high sensitivities, but require cellular content extraction or selective labeling with fluorophores7,9. Questions concerning invasivity stimulated the coin of the biological equivalent of the so called observer effect, referring to the inability to separate a measurement from its potential influence on the observed cell9. In this regard, NMR is one of the most promising techniques for studies of intracellular compounds in untouched living entities (i.e., with extremely weak physical and chemical perturbations)1,7.

The application of NMR to intact individual microscopic biological entities was previously reported down to a volume of 5 nL. The first single-cell NMR experiments were performed on Xenopus laevis ova10 which have volumes of about 1 μL. Later, single giant neurons of Aplysia californica, with volumes of approximately 10 nL, were studied11. The particularly large volumes of these cells allowed several pioneering studies such as the profiling of highly concentrated metabolites and their subcellular localization12,13, imaging of Xenopus laevis cleavage14 and neurons structure15, and study of water diffusion properties within the cytoplasm and nucleus10,11,16,17,18. Recently, also spectroscopy of a single adult C. elegans worm (about 5 nL volume) was reported19.

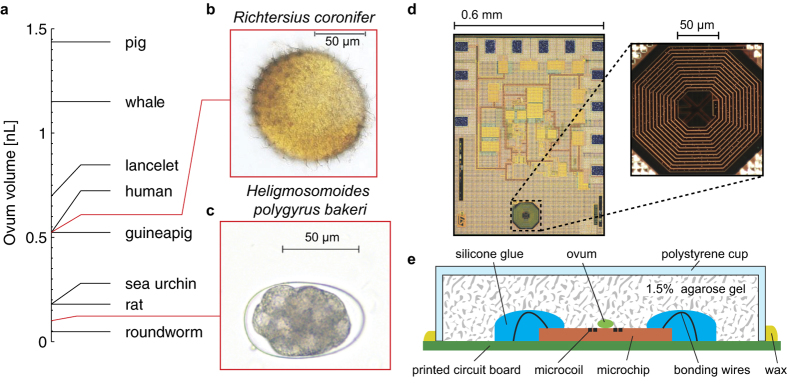

In this work we report, for the first time, NMR-based spectroscopy of single untouched sub-nL ova, specifically describing experiments on the tardigrade Richtersius coronifer (Rc) and the nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri (Hp). These ova are just two of the many models present at the sub-nL scale (Fig. 1a), which include numerous species of microorganisms, echinoderms, and mammals (humans included)20. Rc ova are spherical with conical processes on the cuticular surface of the egg shell and have a typical volume of 0.5 nL (Fig. 1b). Hp ova are ellipsoidal and have a typical volume of about 0.1 nL (Fig. 1c). NMR spectroscopy of sub-nL biological samples is both a volume and concentration limited problem, setting severe constraints on the required spin sensitivity. Here we employ a recently developed single-chip integrated inductive NMR probe21 entirely realized with a commercially accessible complementary-metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology, where the combination of a low noise transceiver and a multilayer microcoil allows for high spin sensitivities in sub-nL volumes (Fig. 1d). In brief, the entire NMR probe occupies an area of about 1 mm2, it has a sensitive region of about 200 pL (on top of the microcoil) with a spin sensitivity at 7 T of about 1.5 × 1013 spins/Hz1/2, and its planar geometry allows for a relatively easy access to the sensor. In order to use the device for the spectroscopy of sub-nL ova of microorganisms, we manually place the sample in the sensitive region of the probe using a polystyrene cup filled by agarose gel (see Methods). Figure 1e describes the assembled probe where single ova are in contact with the microcoil surface and embedded in the gel. This setup systematically allows for experimental times as long as one day.

Figure 1. Samples and setup.

(a) Approximate volumes of ova of selected animals. (b,c) Typical bright field images of the ova studied in this work. (d) Photographs of the integrated microchip and microcoil (details in Ref. 21). (e) Schematic representation of the single ovum probe in section view.

Results

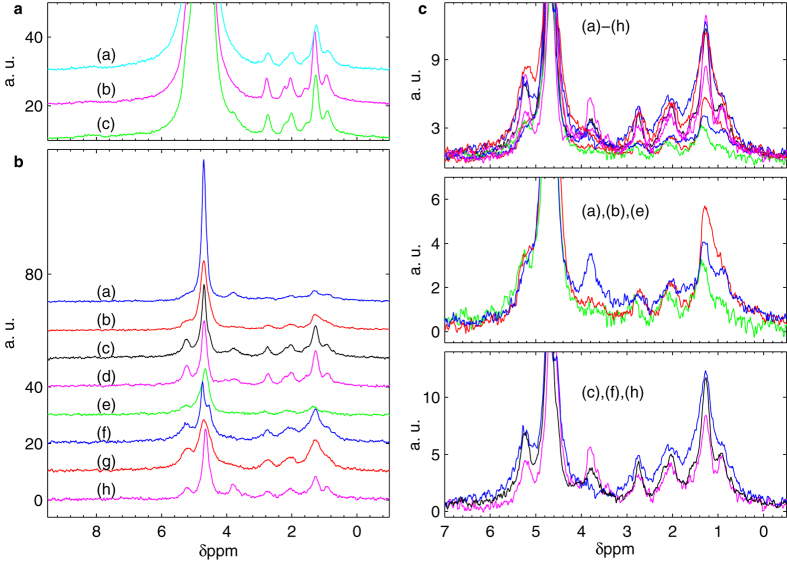

Linewidth in Rc ova

Figure 2a shows three 1H NMR spectra obtained at 7 T (300 MHz) from single Rc ova embedded in H2O-based agarose gels. Due to a measured linewidth of about 70 Hz, the strong water signal (used as internal chemical shift reference at 4.7 ppm17) overlaps with nearby resonance lines. The relatively short spin-spin relaxation times typically observed in oocytes explain only partially these broad lines13,17,18 that must be caused by susceptibility mismatches. In order to investigate the origin of the field distortions we performed measurements with an alternative setup enabling the spectroscopy of these samples in pure water and with controlled and reduced hardware-related field distortions (see S.I). Repeated experiments suggest that the linewidth measured in Rc ova is intrinsically related to the sample, probably resulting from microscopic constituents of the ovum introducing susceptibility mismatches whose typical spatial distribution impedes field shimming in the intracellular region. In line with this observation, previous studies limited to the vegetal cytoplasm of intact Xenopus laevis ova attributed similarly broad linewidths (about 0.3 ppm) to the presence of yolk platelets, or other organelles with paramagnetic components, generating local susceptibility mismatches13. However, despite the relatively low spectral resolution that characterizes Rc ova, the achieved limit of detection (advantageous in the setup employing the integrated single-chip probe) is sufficient for a qualitative detection of intracellular compounds (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. NMR spectroscopy of single Richtersius coronifer (Rc) ova.

(a) Three Rc single ovum experiments in H2O-based gels realized by dispersing 1.5% agarose in either M9 buffer (a) or pure H2O (b–c). (b) Eight Rc single ovum experiments in D2O-based gels realized by dispersing 1.5% agarose in pure D2O. (c) Detailed comparison of Rc ova in D2O-based gels. Colors refer to the same spectra as in (b).

Rc ova spectroscopy

In presence of susceptibility mismatches enlarging the water signal it is difficult to apply water suppression techniques without introducing significant spectral artifacts22. As an alternative to the use of water suppression techniques we embedded the biological sample in gels based on heavy water (D2O), thus eliminating the water signal by replacement of water with D2O. In D2O-based agarose gels, HDO is formed by proton exchange with the OH groups in the agarose molecule. HDO resonates at about 0.03 ppm relative to the H2O chemical shift23 and contributes to the only background signal that is visible in our experimental conditions and time scales (Fig. S2). The weaker background signal in D2O gels (about 100 times smaller than in H2O gels) is reproducible, allows one to better resolve the resonance lines close to water, and can be used as internal chemical shift reference (at 4.7 ppm as water). We do not exclude that, in presence of the sample, the peak at 4.7 ppm results also from leftover H2O within the ova.

Figure 2b shows NMR spectra of eight single Rc ova in D2O-based gels obtained by dispersing agarose in pure heavy water. These spectra exhibit linewidths and chemical shifts compatible with the ones observed in H2O-based gels. A detailed comparison among spectra of different ova seem to indicate that the Rc ova exhibit a certain degree of spectral heterogeneity (Fig. 2c). In what follows we discuss the possible experimental artifacts that could lead to artificial spectral diversities and show a reproducibility study of single ova spectra.

Rc ova are randomly selected from a population where there is no control over fertilization and/or development stage. Their volume is approximatively spherical, with a diameter naturally varying from 100 to 130 μm. As shown in detail by the sensitivity maps in Fig. S3, the most sensitive region of our excitation/detection microcoil roughly corresponds to a deformed semi-ellipsoid of about 200 pl, i.e. smaller than the ova volume. Consequently, the signal amplitude does not depend linearly on the ovum volume. In order to quantitatively estimate the dependence of the signal amplitudes on the natural variability of ova volumes, we performed a numerical integration of the effective sensitivity shown in Fig. S3 over spherical volumes (representing Rc ova) having diameters of 100 and 130 μm, placed on top of the microcoil, in which an homogeneous spin density is considered. The result of this calculation indicate that the maximum variability of signal amplitude due to different ova volumes is of about 25%. This value slightly increase to about 30% when the smaller sphere is laterally displaced by 15 μm with the respect to center of the microcoil. From this estimation, we deduce that the variability in terms of signal amplitudes shown in Fig. 2 (as large as 350%) cannot be explained by the natural variability of ova volumes and/or the ovum-to-microcoil misalignment.

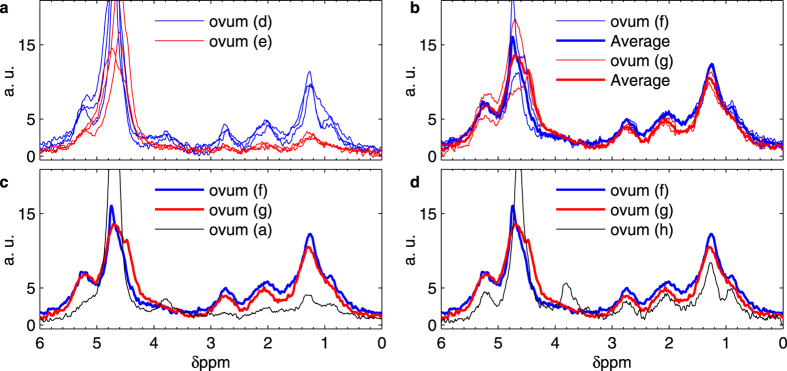

Other factors that might provoke artificial heterogeneity among these NMR spectra can be: (1) the non-homogeneous coil sensitivity combined with a non-uniform intracellular chemical composition; (2) the random orientation of the ovum within the structural field inhomogeneity of the setup; (3) the presence, upon sample placing, of invisible air bubbles at the microchip-sample-gel interface (see Methods for assembly procedure). In order to investigate these possible sources of artifacts, we performed six additional experiments on four Rc ova, in particular on the ova which produced the spectra (d), (e), (f) and (g) shown Fig. 2b. Figure 3a shows spectra of ovum (d) and ovum (e) after three arbitrary repositioning, realized delicately rotating the ova within the respective spent gels. Although we observe some variations of the linewidths as well as of the signal amplitudes, the dominant spectral features (i.e. the ones between 0 and 4 ppm) are conserved upon sample rotation and change of local environment. Figure 3b shows the result of experiments where both ovum (f) and (g) are repositioned in a fresh gel. As we can see, the dominant spectral features were conserved also upon transfer into fresh gels. Figure 3c and d compare the averaged spectra of ova (f) and (g) to spectra of ova (a) and (h), showing that the variability in spectra of different ova can be larger than the variability of repeated experiments on the same ovum. Overall, Fig. 3 suggests that the observed diversity among spectra of Rc ova cannot be attributed only to the manipulation and positioning of the ovum but must be caused, at least partially, by its intrinsic properties.

Figure 3. Reproducibility study of Richtersius coronifer (Rc) spectra.

(a) Measurements of two ova, ovum (d) and ovum (e) as indicated in Fig. 2b. Each ovum was arbitrarily repositioned three times within the respective spent gels. Each spectrum results from 12 hours of averaging. (b) Measurements of two ova, ovum (f) and ovum (g) as indicated in Fig. 2b. Each ovum was arbitrarily repositioned twice within fresh gels. Each spectrum results from 12 hours of averaging. (c) Comparison of averaged spectra of ova (f) and (g) with spectrum of ovum (a) as indicated in Fig. 2b. (d) Comparison of averaged spectra of ova (f) and (g) with spectrum of ovum (h) as indicated in Fig. 2b.

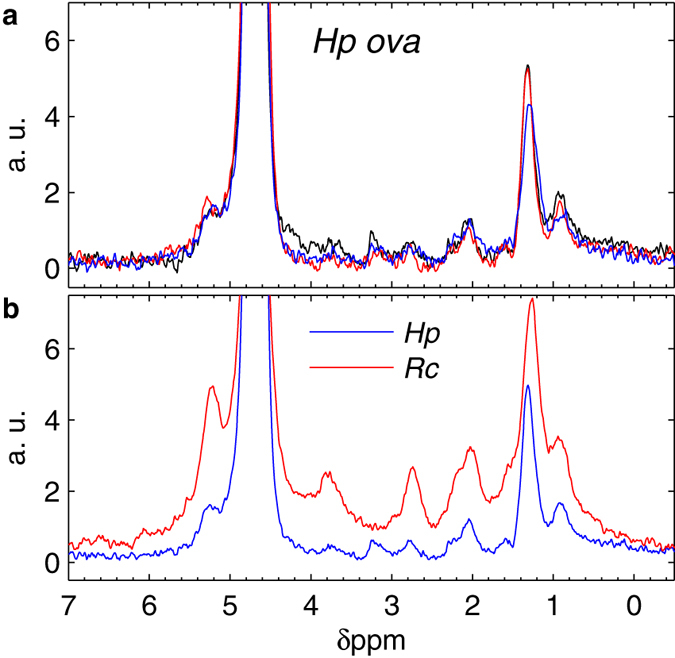

Hp ova spectroscopy

Figure 4a shows 1H NMR spectra obtained from three different single Hp ova placed in D2O-based gel, resulting from 36 hours of averaging and characterized by a linewidth of about 0.25 ppm. Hp ova, whose ellipsoidal shape was systematically oriented horizontally on the gel, were always entirely contained within the most sensitive region of the probe (see Figs 1c and S3) allowing for a full exploitation of the microcoil high sensitivity. Contrarily to the case of Rc ova, in these measurements on Hp ova we do not observe a clear indication of heterogeneity despite the study is performed at comparable effective sensing capability (see below). With a typical volume of about 0.1 nl the Hp ovum is, to date, the smallest intact biological sample in which intracellular compounds are detected with NMR spectroscopy. Figure 4b shows averaged NMR spectra obtained from experiments on Rc and Hp ova in D2O-based gels. These spectra indicate that, at our level of sensitivity, the averaged intracellular chemical compositions of Rc and Hp ova are similar, with only small eventual differences at 3.2 and 3.8 ppm between the two species.

Figure 4. NMR spectra of single Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri (Hp) ova and averaged spectra of Richtersius coronifer (Rc) and Hp.

(a) Three Hp single ovum experiments in D2O-based gels. (b) Comparison between average spectra of five Rc ova (red) and three Hp ova (blue) in D2O-based gels.

Sensitivity of the single-chip probe

Due to the planar geometry of the excitation/detection coil, our probe has an effective spin sensitivity which depends on the sample volume, shape, and distance from the coil surface. Our experimental conditions are characterized by a spectral resolution of about 0.3 ppm and a field strength of 7 T. In the case of a spherical sample of 30 μm diameter in contact with the chip surface, the time-domain spin sensitivity of about 1.5 × 1013 spins/Hz1/2 corresponds to a limit of detection (LOD) in the frequency domain of about 700 pmol of 1H nuclei per single scan (quantity of 1H nuclei that gives a signal-to-noise ratio of three). In this example the sensing capability of the microcoil is fully exploited as the sample is contained within the most sensitive region of the detector (see S3). In the case of a spherical sample of 100 μm diameter in contact with the chip surface, the spin sensitivity is reduced to about 4 × 1013 spins/Hz1/2, corresponding to an LOD in the frequency domain of about 1900 pmol of 1H nuclei per single scan (the spins intended to be distributed homogeneously within the whole sample). In terms of LOD, the performance of our single-chip probe are competitive with the most sensitive inductive NMR devices so far reported24,25,26,27.

Chemical shifts in Rc and Hp ova

In this study the relatively small number of samples available (see Methods) poses significant and non-trivial technical challenges to studies of ova collections aimed at the elucidation of proton peaks assignment (see Discussion). In our experiments the peak assignment is hindered by the combination of a small number of spins with a relatively poor spectral resolution. Nevertheless, a few qualitative observations can be done by comparison to previously reported NMR spectra of intact C. elegans worms28 and Xenopus laevis ova13,17. Although these NMR-based studies analyze biological entities that are different from the ones investigated in this work, they probably represent the closest term of comparison available in literature in terms of volume size and samples nature. The NMR signals in Xenopus laevis13,17 at about 0.9, 1.3, 2.1, 2.8, 5.2 ppm were attributed to highly concentrated yolk lipids (in particular triglycerides13,29). These results well explain the origin of the dominant features in both Rc and Hp ova spectra. In Fig. 4a and b, a peak at about 3.2 ppm seems to discriminate the intracellular content of Hp ova from the one of Rc ova. Prominent resonances at about 3.2 ppm were previously assigned to a relatively restricted group of metabolites in intact C. elegans worms, which are nematodes as Hp28.

As shown in Fig. 2 a visible signal at 3.8 ppm is present in some Rc ova. A resonance at about 4 ppm was assigned to the glycerol backbone in Xenopus laevis, typically lower and broader with respect to the other lipid signals (to which this compound is strictly related)13. Hence, this resonance is hardly related to yolk lipids. The presence of a highly concentrated endogenous compound is a more likely explanation for the signal detected at this particular chemical shift.

Discussion

In this study we reported on the use of a state of art sub-nL NMR probe for the analysis of single sub-nL ova of microorganisms, indicating the limits of the technique for the non-invasive detection of intracellular compounds within ova as small as 0.1 nl. The results shown may be used as a starting point to extrapolate the realistic experimental possibilities offered by NMR tools for applications such as the non-invasive selection of microscopic entities based on the direct quantification of highly concentrated endogenous compounds. In terms of spin sensitivity performance that future setups may offer, a straightforward improvement is the use of a higher field. Moving from 7 T to 23.5 T (the highest field commercially available) with the same microcoil should improve the spin sensitivity by a factor of six if the linewidth originates entirely from magnetic susceptibility issues (see S.IV). In these conditions it is reasonable to achieve limits of detection on 1H nuclei in the order of 7 pmol in 10 minutes and 0.9 pmol in 10 hours for samples having a volume below 100 pl and linewidths as large as 0.3 ppm. Further improvements are obvious for samples exhibiting typical linewidths narrower than the ones observed in this study.

Improved spectral resolutions may be obtained by MAS techniques13,19,30. A few explorations on microscopic intact biological samples report linewidths of about 0.1 ppm in Xenopus laevis eggs at 14 T13 and C. elegans at 23.5 T19. Experiments on large collections of C. elegans and bovine tissues demonstrate linewidths as narrow as 0.05 ppm19,30. It seems therefore reasonable to obtain significant narrowing of the line via MAS. Although MAS probes are not yet optimized for maximum sensitivity at the sub-nL scale, its application at larger volume scales (few tens of nL) may already provide tools supporting the study of sub-nL ova. In wider terms, static and/or spinning probes analyzing 10 nL collections of rare or precious sub-nL ova would allow for proton assignments (elucidating eventual heterogeneities detected among individual samples at the single ovum level) and a better characterization of the spin-spin relaxation properties without need of excessive sample accumulation. However, the realization of such tools is hindered by significant technical challenges, simultaneously requiring small sensitive volumes, high filling factors, high resolution, MAS, and sample loading and manipulation capabilities.

Our results, obtained at a relatively weak field of 7 T, suggest that a LOD of about 5 pmol of 1H nuclei within a sub-nL region (in this study specifically corresponding to sensitivities ranging from 20 to 50 mM in terms of intracellular concentration) is sufficient for the detection of the most concentrated compounds in individual ova of microorganisms having volumes below 1 nL. Curiously, signals at chemical shifts that are not typical of yolk lipids are visible. This indication seems, at first sight, in contradiction with the previous NMR spectroscopic studies of intact Xenopus laevis ova13, where yolk lipids explain all the spectroscopic features, which are essentially identical to those of the yolk of an hen egg31. In order to detect metabolites in these samples it was indeed necessary the use of magic angle spinning probes at 14 T loaded with more than one ovum13. However, the Xenopus laevis ovum (the smallest previously analyzed with NMR spectroscopy) might not be the best term of comparison, as its typical volume (about 1 μL) is larger by a factor ranging from 103 to 104 with respect to the ova studied in this work.

A peculiar class of sub-nL ova that justifies the interest in approaches for the non-invasive intracellular spectroscopy of individual samples is constituted by the mammalian zygotes. Recent studies demonstrate, using techniques other than NMR, that in sheep32 and human33 oocytes the uptake or production rates of metabolites such as lactate, pyruvate, and glucose can reach 100 pmol/oocyte/h and change radically along the natural development. It is worth noting that these results concern exchange rates measured in the extracellular medium and, hence, do not provide a direct quantification of the intracellular content and its time evolution. Spectrophotometry of intracellular extracts, on the other hand, has shown that up to 30 pmol/oocyte of glutathione (GSH) are contained in oocytes of goat34 and pig35,36 and can change in reaction to environment and developmental stage37. Variations of a few pmol/oocyte of GSH in time scales of the order of several hours have been reported in hamster38 and rat39 oocytes. In these studies, the intracellular GSH content and its evolution is directly measured, but the ensemble measurements hide possible heterogeneities among single entities. These findings indicate that the sensitivity achievable with high sensitivity miniaturized inductive NMR probes should be sufficient for a non-invasive real-time intracellular monitoring of GSH in single mammalian zygotes. The application of NMR spectroscopy to the analysis of spent culture media was recently proposed to aid the selection of viable human embryos for in vitro fertilization purposes40. The direct application of NMR on single embryos using miniaturized high sensitivity probes is potentially advantageous for this aim. We suggest that systematic and extensive NMR studies on single cultured ova may provide new data that could shed light on cryptic processes involved in embryonic development32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 and provide new methodologies to estimate embryonic health37,40.

The hardware used in this work is an ultra-compact integrated probe entirely realized with commercially accessible complementary-metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technologies that might open to the realistic possibility of implementing relatively low-cost arrayed miniaturized probes. However, improvements for what concern samples manipulation are required, especially for applications aiming at studying precious samples such as mammalian embryos. Recently, many efforts were successfully dedicated to the microfabrication of devices for manipulation and culture of individual living embryos41,42. Both integrated circuits and microfluidics are suitable for arrays implementation, and their combination has been demonstrated in applications such as single cell magnetic manipulation43 and flow cytometry44. We believe that this combination can be extended to NMR applications for the realization of arrayed high sensitivity NMR probes, enabling simultaneous studies on a large number of single biological entities in the same magnet.

Methods

Experiments and protocols were approved by the SV-biosecurity unit committee of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and carried out in accordance with the experimentation guidelines of the institution.

Single ovum probe mounting

The ova were first transferred, using a 100 μl pipette, from the tube into a Petri dish filled by 1.5% H2O-based agarose gel. Often more than one ovum was found on the Petri dish, in which case the additional samples were left isolated on the gel for eventual later use and stored at 4 °C between successive experiments. Single ova were transferred into a 1.5% agarose gel-filled polystyrene cup using two eyelashes. No visible damage to the ova was provoked during this procedure. The concentration of agarose was carefully chosen, based on repeated assemblies of ova, such that the resulting gel was hard enough to allow a stable placement of the ovum but still sufficiently soft to avoid ovum rupture during the setup assembly (typically happening for gels with more than 3% of agarose). The gel matrix was providing a deformable soft surface to embed and hold the ovum. When placed on the gel, the ovum was protruding from the surface by about half of its volume, hence ensuring an initial physical contact between the ovum and the surface of the microcoil upon placing. Later, the cylindrical polystyrene cup, containing the gel with the ovum on its surface, was positioned on top of the microchip in such a way that the ovum was precisely placed over the microcoil. The local depletion of any visible air bubble was relatively easy and reproducible. The cup was fixed to the printed circuit board with candle wax. The gel keeps the sample in close contact with the coil for days without physically damaging it, whereas the wax prevents gel drying. The microchip was wire bonded to a printed circuit board, with bonding wires electrically isolated by a silicone glue. Figure 1e describes the assembled probe.

Tardigrade Richtersius coronifer (Rc)

Eggs of Rc were extracted from a moss sample collected in Öland (Sweden) by washing the substrate, previously submerged in water for 30 min, on sieves under tap water and then individually picking up eggs with a glass pipette under a dissecting microscope. The eggs were shipped within 24 hours in sealed tubes with water and subsequently stored at −20 °C before use. The embryonic development of Rc ova is relatively slow, with the eggs hatching in more than 50 days45. All experiments were carried out within a week after tube opening. The tube was stored at 4 °C between separated experiments. The NMR experiments were performed in H2O, M9, and D2O. It is known that prolonged exposure to a high concentration of D2O affects living organisms to different extents, from lethal to marginal46,47. In order to test the effects of D2O exposure on Rc specimens, 16 eggs and 10 animals were submerged in D2O (at 15 °C) for 36 and 24 hours respectively and then transferred in H2O. A control group of 16 eggs was kept in H2O. The effects of the exposition to D2O on the survival of the specimens were not negligible but definitively not systematically lethal: all the animals survived, and a hatching of 84% in the control group and of 63% in those exposed to D2O was observed after a time of approximately 2 months. The total amount of Rc ova available for this study was of about 120 units.

Nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri (Hp)

Eggs of Hp were collected from faeces of infected mice. Faeces were first dissolved in water and then washed with a saturated NaCl solution. Floating eggs were collected from the top layer of the solution and washed twice. Final centrifugation in water for 5 minutes at 2000 rpm sedimented clean eggs at the bottom of the tube. The amount of ova typically available at each extraction varied from tens to a few hundred depending on the host organism response to the infection. Fecundated ova of Hp develop into a fully embryonated state within 24 hours and within two days stage 1 larvae begin to emerge48. In H2O-based gels Hp ova regularly hatched after a few hours, the emerging larvae migrating far from the sensitive region of the microcoil. In D2O-based gels the ova never hatched within two days of observation, hence allowing for the necessary long averaging time. All experiments were carried out within two days after sample extraction. The tube was stored at 4 °C between separated experiments.

NMR experimental details

NMR experiments were performed in the 54 mm room temperature bore of a Bruker 7.05 T (300 MHz) superconducting magnet. The electronic setup was identical to the one described in details in ref. 21. All experiments employing the single-chip probe were performed with a repetition time of 2 s, a π/2 pulse length of 2.5 μs, and an acquisition time of 400 ms. The time domain data were post-processed by applying an exponential filter with decay of 50 ms. The alphabetic order in Fig. 2b corresponds to the chronologic order of the measurements.

Chemicals

H2O (Sigma Aldrich, 270733). D2O (Acros Organics, 166301000). Agarose (BioConcept, Standard Agarose LE-7-01P02-R). Silicone glue (Momentive, RTV118). Polystyrene cup (Semadeni, 10 mm diameter, 5 mm height). The M9 buffer is prepared as in ref. 49.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Grisi, M. et al. NMR spectroscopy of single sub-nL ova with inductive ultra-compact single-chip probes. Sci. Rep. 7, 44670; doi: 10.1038/srep44670 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre Gönczy and Enrica Montinaro for discussions on the experimental setup, Ingemar Jönsson for providing the moss with Rc ova, and Manuel Kulagin for helping in Hp ova extraction.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.G. and G.B. conceived the work. M.G. designed the experimental setup, performed experiments and data analysis. F.V. and B.A. provided micro-fabricated probes. B.V., R.G. and N.H. provided samples and protocols. M.G. and G.B. wrote the manuscript. N.H., B.V., R.G., F.V., B. A. contributed to writing at all stages of their involvement in this project. All the authors discussed the results and implications, edited and approved the manuscript.

References

- Selenko P. & Wagner G. Looking into live cells with in-cell NMR spectroscopy. J Struct Biol 158, 244–253 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serber Z., Corsini L., Durst F. & Dotsch V. In-cell NMR spectroscopy. Methods in enzymology 394, 17–41 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara D. et al. Protein structure determination in living cells by in-cell NMR spectroscopy. Nature 458, 102–105 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin R. T., Morgan L. O., Gregg C. T. & Matwiyof N. A. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of living cells and their metabolism of a specifically labeled 13C substrate. Febs Lett 28, 259–264 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie A. Y. et al. In vivo visualization of gene expression using magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Biotechnol 18, 321–325 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise B. J. et al. Metabotyping of Caenorhabditis elegans reveals latent phenotypes. P Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 19808–19812 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubakhin S. S., Romanova E. V., Nemes P. & Sweedler J. V. Profiling metabolites and peptides in single cells. Nat Methods 8, S20–S29 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenobi R. Single-cell metabolomics: analytical and biological perspectives. Science 342, 1243259 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm-Stecher B. F. & Johnson E. A. Single-cell microbiology: tools, technologies, and applications. Microbiol Mol Biol R 68, 538–559 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo J. B., Blackband S. J., Schoeniger J., Mattingly M. A. & Hintermann M. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of a single cell. Nature 322, 190–191 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeniger J. S., Aiken N., Hsu E. & Blackband S. J. Relaxation-time and diffusion NMR microscopy of single neurons. J Magn Reson Ser B 103, 261–273 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S. C. et al. NMR spectroscopy of single neurons. Magn Reson Med 44, 19–22 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. C. et al. Subcellular in vivo1H MR spectroscopy of Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biophys J 90, 1797–1803 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. C. et al. In vivo magnetic resonance microscopy of differentiation in Xenopus laevis embryos from the first cleavage onwards. Differentiation 75, 84–92 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Flint J. J., Hansen B. & Blackband S. J. Investigation of the subcellular architecture of L7 neurons of Aplysia californica using magnetic resonance microscopy (MRM) at 7.8 microns. Sci Rep-Uk 5, 11147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S. C., Buckley D. L., Gibb S., Webb A. G. & Blackband S. J. MR microscopy of multicomponent diffusion in single neurons. Magn Reson Med 46, 1107–1112 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehy J. V., Ackerman J. J. H. & Neil J. J. Water and lipid MRI of the Xenopus oocyte. Magn Reson Med 46, 900–906 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauser S., Zschunke A., Khuen A. & Keller K. Estimation of Water Content and Water Mobility in the Nucleus and Cytoplasm of Xenopus Laevis Oocytes by Nmr Microscopy. Magn Reson Imaging 13, 269–276 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A. et al. μHigh Resolution-Magic-Angle Spinning NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolic Phenotyping of Caenorhabditis elegans . Anal Chem 86, 6064–6070 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flindt R. Amazing numbers in biology. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Grisi M., Gualco G. & Boero G. A broadband single-chip transceiver for multi-nuclear NMR probes. Rev Sci Instrum 86, 044703 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z. C. Proton MRS and MRSI of the brain without water suppression. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp 86–87, 65–79 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J. R., Drinkard W. C. & Kivelson D. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectrum of HDO. J Chem Phys 37, 150-& (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Peck T. L., Magin R. L. & Lauterbur P. C. Design and Analysis of Microcoils for NMR Microscopy. J Magn Reson Ser B 108, 114–124 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber D. A., Cooper R. L., Ciobanu L. & Pennington C. H. Design and testing of high sensitivity microreceiver coil apparatus for nuclear magnetic resonance and imaging. Rev Sci Instrum 72, 2171–2179 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Minard K. R. & Wind R. A. Picoliter 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson 154, 336–343 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badilita V. et al. Microscale nuclear magnetic resonance: a tool for soft matter research. Soft Matter 8, 10583–10597 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pontoizeau C. et al. Metabolomics Analysis Uncovers That Dietary Restriction Buffers Metabolic Changes Associated with Aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Proteome Res 13, 2910–2919 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak L. S. et al. Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by 1H spectroscopy: validation in vivo. Am J Physiol 276, E977–989 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariou D., Le Goff G. & Jacquinot J. F. High-resolution, high-sensitivity NMR of nanolitre anisotropic samples by coil spinning. Nature 447, 694 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasundar R., Ayyar S. & Raghunathan P. Proton resonance imaging and relaxation in raw and cooked hen eggs. Magn Reson Imaging 15, 709–717 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner D. K., Lane M., Spitzer A. & Batt P. A. Enhanced rates of cleavage and development for sheep zygotes cultured to the blastocyst stage in vitro in the absence of serum and somatic cells: amino acids, vitamins, and culturing embryos in groups stimulate development. Biol Reprod 50, 390–400 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreker F. & Englert Y. In vitro development and metabolism of the human embryo up to the blastocyst stage. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B 92, 51–56 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-González E., López-Bejar M., Mertens M. J. & Paramio M. T. Effects on in vitro embryo development and intracellular glutathione content of the presence of thiol compounds during maturation of prepubertal goat oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 65, 446–453 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeydeera L. R., Wang W. H., Cantley T. C., Rieke A. & Day B. N. Coculture with follicular shell pieces can enhance the developmental competence of pig oocytes after in vitro fertilization: Relevance to intracellular glutathione. Biol Reprod 58, 213–218 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brad A. M. et al. Glutathione and adenosine triphosphate content of in vivo and in vitro matured porcine oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 64, 492–498 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luberda Z. The role of glutathione in mammalian gametes. Reproductive biology 5, 5–17 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuelke K. A., Jeffay S. C., Zucker R. M. & Perreault S. D. Glutathione (GSH) concentrations vary with the cell cycle in maturing hamster oocytes, zygotes, and pre-implantation stage embryos. Mol Reprod Dev 64, 106–112 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi H., Bandoh N., Nakahira S., Oh S. H. & Tsuboi S. Changes in intracellular content of glutathione and thiols associated with γ-glutamyl cycle during sperm penetration and pronuclear formation in rat oocytes. Zygote 7, 301–305 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seli E., Botros L., Sakkas D. & Burns D. H. Noninvasive metabolomic profiling of embryo culture media using proton nuclear magnetic resonance correlates with reproductive potential of embryos in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril 90, 2183–2189 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanski J. P. et al. Noninvasive metabolic profiling using microfluidics for analysis of single preimplantation embryos. Anal Chem 80, 6500–6507 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves T. C. et al. A microfluidic system supports single mouse embryo culture leading to full-term development. Rsc Adv 3, 26451–26458 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Liu Y., Ham D. & Westervelt R. M. Integrated cell manipulation system - CMOS/microfluidic hybrid. Lab Chip 7, 331–337 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley L., Kaler K. V. I. S. & Yadid-Pecht O. Hybrid integration of an active pixel sensor and microfluidics for cytometry on a chip. Ieee T Circuits-I 54, 99–110 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson I. et al. Tolerance to γ-irradiation in eggs of the tardigrade Richtersius coronifer depends on stage of development. J Limnol 72, 73–79 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Czajka D. M., Fischer C. S., Finkel A. J. & Katz J. J. Physiological effects of deuterium on dogs. Am J Physiol 201, 357–362 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumitro S. B. & Sato H. The isotopic effects of D2O in developing sea urchin eggs. Cell Struct Funct 14, 95–111 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wabo Poné J. et al. The in vitro effects of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Ageratum conyzoides (Asteraceae) on three life cycle stages of the parasitic nematode Heligmosomoides bakeri (Nematoda: Heligmosomatidae). Veterinary Medicine International 140293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.