Abstract

Bacterial wilt of potatoes—also called brown rot—is a devastating disease caused by the vascular pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum that leads to significant yield loss. As in other plant-pathogen interactions, the first contacts established between the bacterium and the plant largely condition the disease outcome. Here, we studied the transcriptome of R. solanacearum UY031 early after infection in two accessions of the wild potato Solanum commersonii showing contrasting resistance to bacterial wilt. Total RNAs obtained from asymptomatic infected roots were deep sequenced and for 4,609 out of the 4,778 annotated genes in strain UY031 were recovered. Only 2 genes were differentially-expressed between the resistant and the susceptible plant accessions, suggesting that the bacterial component plays a minor role in the establishment of disease. On the contrary, 422 genes were differentially expressed (DE) in planta compared to growth on a synthetic rich medium. Only 73 of these genes had been previously identified as DE in a transcriptome of R. solanacearum extracted from infected tomato xylem vessels. Virulence determinants such as the Type Three Secretion System (T3SS) and its effector proteins, motility structures, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxifying enzymes were induced during infection of S. commersonii. On the contrary, metabolic activities were mostly repressed during early root colonization, with the notable exception of nitrogen metabolism, sulfate reduction and phosphate uptake. Several of the R. solanacearum genes identified as significantly up-regulated during infection had not been previously described as virulence factors. This is the first report describing the R. solanacearum transcriptome directly obtained from infected tissue and also the first to analyze bacterial gene expression in the roots, where plant infection takes place. We also demonstrate that the bacterial transcriptome in planta can be studied when pathogen numbers are low by sequencing transcripts from infected tissue avoiding prokaryotic RNA enrichment.

Keywords: Ralstonia solanacearum, bacterial wilt, Solanum commersonii, RNA sequencing, transcriptomics, disease resistance, potato brown rot

Introduction

Changes in pathogen gene expression control the switch from a commensal to a parasitic relationship with the host, which may subvert the host metabolism or development to the pathogen's benefit (Stes et al., 2011). However, there is still limited information concerning how this is controlled. Understanding how these trophic relationships initiate and persist in the host requires deciphering the functional adaptations at the transcriptomic level. Pioneer studies of the expression profiles of bacterial animal pathogens in infected tissues showed that the genes induced more strongly contributed to bacterial virulence and/or survival in the host (reviewed in La et al., 2008).

Ralstonia solanacearum is the causal agent of the destructive bacterial wilt disease in tropical and subtropical crops, including tomato, tobacco, banana, peanut, and eggplant (Hayward, 1991; Peeters et al., 2013). The disease in potato is also called brown rot and is endemic in the Andean region, where potato is a staple food, causing an important impact on food production and the economy (Priou, 2004; Coll and Valls, 2013). Disease control of bacterial wilt is very challenging, because of the bacterium aggressiveness, its persistence in the field and the lack of resistant commercial varieties in any of its hosts. Potato breeding programs have used wild species related to Solanum tuberosum, such as Solanum commersonii, as sources of resistance against bacterial wilt (Kim-Lee et al., 2005; Siri et al., 2009).

As in most Gram-negative animal and plant pathogens, the major pathogenicity determinant in R. solanacearum is the type three secretion system (T3SS) (Boucher et al., 1987). This system injects bacterial proteins called effectors directly into the eukaryotic host cells to manipulate the host defenses and establish disease (Buttner, 2016; Popa et al., 2016a). Amongst other factors that contribute to R. solanacearum virulence are motility—either caused by flagella or type IV pili- and the reactive oxygen species (ROS)- detoxifying enzymes (Meng, 2013).

In vitro studies using microarrays allowed the study of R. solanacearum virulence gene expression and the discovery of novel regulatory networks (Occhialini et al., 2005; Valls et al., 2006). However, the first studies on gene expression in planta using quantitative reporters indicated that R. solanacearum virulence genes showed unexpected expression patterns (Monteiro et al., 2012). Contrary to what was believed based on in vitro studies, it was demonstrated that the genes encoding the T3SS genes and its associated effectors were transcribed in planta at late stages of infection (Monteiro et al., 2012). These findings were later confirmed in transcriptomic studies with R. solanacearum extracted from infected tomato and banana plants (Jacobs et al., 2012; Ailloud et al., 2016). However, these studies in planta could only be performed from heavily colonized plants, as limited pathogen biomass has hindered until recently the investigation of gene expression at the early stages of the interaction, when plants are still asymptomatic.

In a previous work, we demonstrated that rRNA-depleted RNAs obtained from infected roots could be used to determine the transcriptomic responses of S. commersonnii plants resistant or susceptible to bacterial wilt through RNA sequencing (Zuluaga et al., 2015). Here, we have used these sequences to extract R. solanacearum UY031 transcripts in silico and have compared them to the bacterial transcriptomes obtained in synthetic media to investigate the pathogen RNAs expressed during early infection. Our results reveal differential expression of a number of known and putative transcriptional regulators and virulence factors during early plant colonization, providing insight into their role in infection.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plant accessions, and growth conditions

The R. solanacearum isolate UY031, phylotype IIB, sequevar 1, originally isolated from potato (Siri et al., 2011), carrying the LUX-operon under the psbA promoter (Monteiro et al., 2012) was used for all experiments. Bacteria were routinely grown in rich B medium as described (Monteiro et al., 2012).

S. commersonnii accessions F97 (susceptible to bacterial wilt) and F118 (moderately resistant) obtained from a segregating population were used in this work and propagated in vitro as described (Zuluaga et al., 2015).

Sample preparation

As a control condition, bacteria were grown for 2 days on rich solid medium without tetrazolium chloride or antibiotics at the appropriate dilution to obtain separate colonies. Bacteria were recovered from plates and mixed with 5% of an ice-cold transcription stop solution [5% (vol/vol) water-saturated phenol in ethanol]. Cells were centrifuged at 4°C for 2 min at maximum speed and the bacterial pellet was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For plant RNA samples, S. commersonii F97 and F118 roots were inoculated as described in Zuluaga et al. (2015). Briefly, plant roots from 2-week old plants grown in soil were injured with a 1 ml pipette tip and inoculated by soil drenching with a bacterial solution at 107 colony forming units (cfu)/ml. Control plants were mock-inoculated with water. After inoculation, plants were kept in a growth chamber at 28°C in long-day conditions. Luminescence quantification was used to select plants with comparable infection levels in the susceptible and the resistant accessions, corresponding to approximately 105 colony forming units per g of tissue (Cruz et al., 2014).

RNA extraction, sequencing, and library preparation

Total RNA from bacterial cultures was extracted using the SV Total RNA Isolation System kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions for Gram-negative Bacteria. Infected plant RNA extractions were carried out as described (Cruz et al., 2014). RNA concentration and quality was measured using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. For rRNA depletion, 2.5 μg of RNA were treated with the Ribo-zero(™) magnetic kit for bacteria (Epicenter). Three biological replicates per condition were subjected to sequencing on an Illumina-Solexa Genome Analyzer II apparatus in the Shanghai PSC Genomics facility using multiplexing and kits specially adapted to obtain 100 bp paired-end reads in stranded libraries. Raw sequencing data is available in the Sequence Read Archive under the accession code SRP096020.

Read mapping, quantification, and differential gene expression analysis

FASTQC was used to evaluate the quality of the RNA-seq raw data. R. solanacearum reads were identified from total infected root sequences using Bowtie2 (version 2.2.6; Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) as described in the results section. The completely sequenced genome of strain UY031 (Guarischi-Sousa et al., 2016) was used as reference. For identification of R. solanacearum reads, the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA) tool was initially used. However, a high number of reads from mock-inoculated control samples mapped to the bacterial genome (Table 1). Visual evaluation of these mapped reads using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tool (Robinson et al., 2011; Thorvaldsdottir et al., 2013) showed that most contained mismatches to the R. solanacearum genome sequence, indicating that they likely belonged to contaminating bacteria. BWA was thus assayed with more stringent parameters (-B 20-O 30-E 5-U 85), to increase penalties for mismatches, gap openings, gap extension, and unpaired read pairs, resulting in a reduction of only half of the reads mapping to the genome. Finally, Bowtie2 was assayed, once more using stringent parameters to penalize mismatches and gaps (–mp 30–rdg 25,15–rfg 25,15). In this case, mapped reads levels in mock-inoculated plants could be considered background compared to the high read numbers from inoculated samples, thus, Bowtie2 was finally used in all samples analyzed, including RNA-seq reads coming from in vitro grown bacteria (Table 1). Alignments were summarized by genes on counting tables using HTSeq-count (version 0.6.1 p1; Anders et al., 2015) and NCBI's reference annotation (genome features were extracted from NCBI's RefSeq sequences NZ_CP012687.1 and NZ_CP012688.1); alignments with quality lower than 10 were discarded. Differential expression (DE) analysis was carried out with the DESeq2 (version 1.12.3; Love et al., 2014) package in R (version 3.3.2). Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used for multiple testing corrections. Genes with log2(fold-change) > 0.5 and q < 0.01 were considered as differentially expressed. We used these thresholds to select for relevant and robust differentially expressed genes. Final annotation of the genome was defined based on the NCBI gene locus and the gene name and description of the reference R. solanacearum GMI1000 genome annotation (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of aligned reads to the R. solanacearum UY031 genome from mock-inoculated (Control) and inoculated Solanum commersonii accessions.

| BWAa | BWA_stringentb | Bowtie2_stringent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditionc | Replica | Total reads | Reads | % | Reads | % | Reads | % |

| Resistant mock-inoculated | 1 | 83867508 | 110859 | 0.1 | 66083 | 0.1 | 601 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 88913944 | 42040 | 0.0 | 25296 | 0.0 | 771 | 0.0 | |

| Resistant infected | 1 | 71855042 | 348369 | 0.5 | 330968 | 0.5 | 290036 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 96470501 | 943974 | 1.0 | 924297 | 1.0 | 879112 | 0.9 | |

| 3 | 23473454 | 249285 | 1.1 | 234153 | 1.0 | 183728 | 0.8 | |

| Susceptible mock-inoculated | 1 | 100234418 | 70173 | 0.1 | 40797 | 0.0 | 300 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 27594608 | 15060 | 0.1 | 8889 | 0.0 | 137 | 0.0 | |

| Susceptible infected | 1 | 75368620 | 249382 | 0.3 | 232550 | 0.3 | 211561 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 93023963 | 2103356 | 2.3 | 2010284 | 2.2 | 1867585 | 2.0 | |

| 3 | 24695183 | 518872 | 2.1 | 484873 | 2.0 | 410525 | 1.7 | |

Burrows-Wheeler Alignment.

Burrows-Wheeler Alignment using stringent parameters as described in methods.

Samples from Zuluaga, Solé, Lu, BMC Genomics, 2015.

Homology analysis

get_homologs (version 2.0; Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013) was used for searching R. solanacearum UY031 homologous genes on R. solanacearum GMI1000, R. solanacearum IPO1609 and R. solanacearum UW551 strains as well as in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a; NCBI RefSeq sequences GCF_001299555.1, GCF_000009125.1, GCF_001050995.1, GCF_000167955.1, and GCF_000012245.1, respectively. Default algorithm of bidirectional best-hits was used on homologous genes search.

Functional categories

R. solanacearum UY031's genes were functionally categorized using two different strategies. Firstly, functional categories from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a as defined by Yu et al. (2013), were translated to R. solanacearum UY031 based on homology information between the two strains. Although the P. syringae-derived categories should be more specific and accurate for another bacterial plant pathogen, almost 70% of the R. solanacearum UY031 genes could not be classified using this method. Therefore, a second strategy based on Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) categories was applied. Genome features were extracted from NCBI's RefSeq annotation and cdd2cog.pl script (version 0.1; Leimbach, 2016) was used to assign COG IDs and functional categories to the differentially expressed genes (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Obtaining R. solanacearum sequences from infected root tissues

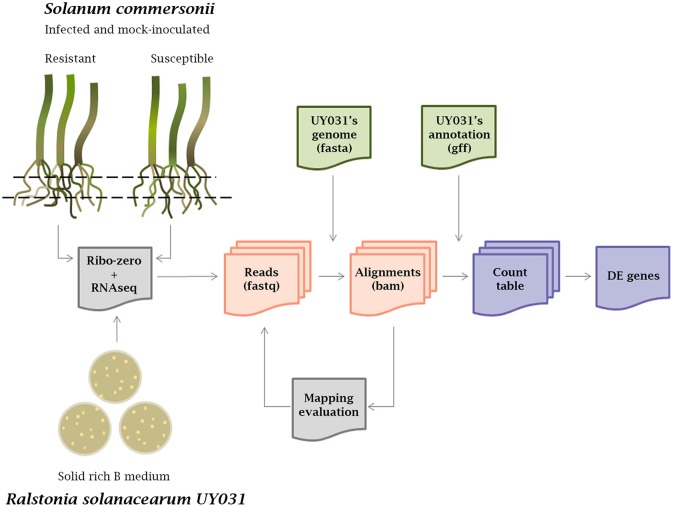

cDNA libraries from rRNA-depleted RNAs isolated from S. commersonii roots inoculated with R. solanacearum were sequenced using Illumina technology as previously reported (Zuluaga et al., 2015). To generate the transcriptomic profile of the bacteria growing inside root tissues, R. solanacearum UY031 sequences were obtained following the pipeline detailed in Figure 1. First, reads from mock-inoculated plants were used as a control to determine the best alignment tool to map against the R. solanacearum UY031 reference genome (Guarischi-Sousa et al., 2016; see material and methods). The Bowtie2 alignment tool with stringent parameters was used, as it retained a number of R. solanacearum reads in mock-inoculated plants that could be considered background levels compared to the high read numbers from inoculated samples (Table 1). All samples were analyzed with Bowtie2, including RNA-seq reads coming from in vitro grown bacteria. We determined that around 1% of the total sequenced reads from plant tissues corresponded to R. solanacearum and these were retained for further analyses. S. commersonnii sequences accounted on average for 63.15% of the total reads sequenced and the remaining reads corresponded mostly to contamination by other bacterial endophytes. The retrieved bacterial sequences were quantified and differentially expressed (DE) genes comparing the different conditions were determined. Total RNAs from infected S. commersonii enabled transcript quantification for over 96% of R. solanacearum UY031 predicted genes (4,609 out of the 4,778; Guarischi-Sousa et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the transcriptomic analysis. RNAseq was carried out from roots of infected and mock-inoculated Solanum commersonii resistant and susceptible varieties and from bacteria grown in solid rich B medium. Three biological replicates were used for each condition. Total extracted RNAs were treated with Ribo-zero to remove rRNA and sequenced using Illumina technology. Raw reads were aligned against the R. solanacearum UY031 genome using different alignment tools and mapping was visually evaluated with the IGV Browser. Mapped reads were quantified using count tables and differential expression (DE) analysis was carried out.

Similar R. solanacearum genes are differentially expressed upon infection of resistant and susceptible S. commersonii plants

In order to compare the R. solanacearum gene expression patterns during infection of resistant and susceptible wild potato plants, we analyzed separately the bacterial reads obtained from infected S. commersonii accessions F118 and F97, respectively. Surprisingly, only two out of the 4,609 genes for which expression was detected showed differential expression between the two genotypes. The differentially-expressed (DE) genes, RSUY_RS08455, and RSUY_RS16950, were both up-regulated in bacteria grown inside the resistant accession (Table 2). The first gene corresponds to an uncharacterized member of the MarR transcriptional regulator family, while the second encodes a hypothetical protein.

Table 2.

R. solanacearum UY031 genes differentially expressed in resistant vs. susceptible S. commersonii.

| UY031 NCBI locusa | UY031 Prokka locusb | GMI1000 locusc | Gene product | Log2FC | Adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSUY_RS08455 | RSUY_17320 | RSc1295 | MarR family transcriptional regulator | 2.37 | 0.0004 |

| RSUY_RS16950 | RSUY_34650 | RSp0403 | hypothetical protein | 2.53 | 0.0017 |

Since R. solanacearum showed extremely similar (>99.9%) transcriptional behavior during interaction with both S. commersonii accessions, bacterial reads from both accessions were treated as biological replicates in the rest of this study.

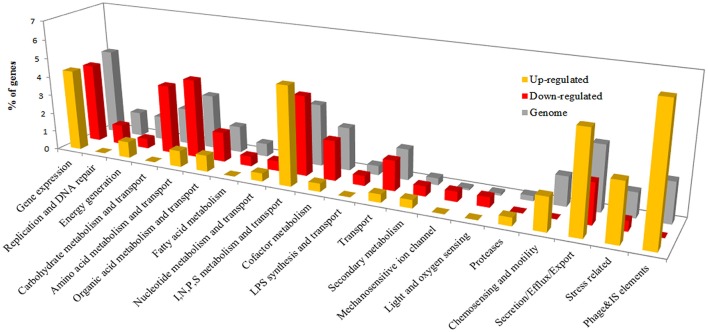

R. solanacearum activates stress-related genes and shuts down metabolic activities during early root colonization

The R. solanacearum in planta gene expression dataset was compared to a reference condition consisting of bacteria grown on solid rich B medium. Bacteria grown on solid medium were used as the reference condition instead of liquid cultures. R. solanacearum colonies grown on solid media better mimic the biofilms and microcolonies formed by R. solanacearum during early infection, when most bacteria occupy plant intercellular spaces (Mori et al., 2016). A total of 422 genes were differentially expressed during pre-symptomatic infection (231 up-regulated and 191 down-regulated), compared to growth on rich medium (Supplementary Table 2). These DE genes were classified into the functional categories previously used for gene expression studies in the plant pathogenic bacterium P. syringae (Yu et al., 2013; Supplementary Table 3). The number of successfully classified genes in each category was quantified in differentially induced or repressed groups and in the whole genome as a reference (Figure 2). This analysis revealed four categories highly over-represented in the up-regulated genes and under-represented in down-regulated genes: stress, secretion, chemosensing, and motility and phage and insertion sequences (IS). These categories represent together approximately 20% of the total induced genes in planta. The opposite trend (under-representation in up-regulated and over-representation in down-regulated genes) is observed in the categories including genes for transport and metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates. In addition, the categories replication and DNA repair, transport, fatty acid metabolism and cofactor metabolism are strongly under-represented amongst the up-regulated genes in planta (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of DE genes classified into Pseudomonas syringae-derived functional categories (Yu et al., 2013). Genes DE between growth in planta vs. rich medium were classified according to the functional categories described for P. syringae (Yu et al., 2013). Categories were grouped by function similarity for better visualization (Supplementary Table 4). As a reference, functional category distribution considering all annotated genes in the UY031 genome is shown.

We used the P. syringae categories because they were created to describe the genes of a bacterial plant pathogen and are thus very informative for this study. However, the same analysis was carried out using the widely used but more general COG categories, and the results confirmed the previously-described tendencies (Supplementary Figure 1). Genes involved in carbohydrate, amino acid, lipid, cofactor, and secondary metabolism were over-represented among those down-regulated in planta. A clear enrichment of replication, cell motility and recombination and repair (where IS elements are included) was observed in the up-regulated genes. Interestingly, a clear asymmetry was seen for unclassified genes in this case, for they represent 40% of the up-regulated but only 7% of the down-regulated genes.

Closer scrutiny of the up-regulated genes in the plant revealed that the category secretion included 11 genes encoding the T3SS and its associated effectors and four chemosensing and motility genes, coding for pilus assembly and flagellum transcriptional activators (Table 3).

Table 3.

R. solanacearum UY031 genes differentially expressed in potato roots vs. solid rich medium.

| Function | UY031 NCBI locusa | UY031 Prokka locusb | GMI1000 locusc | Log2FC | Gene name | Gene product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RALSTONIA SOLANACEARUM VIRULENCE GENES | ||||||

| Type III secretion system and effectors | RSUY_RS19685 | RSUY_40420 | RSp0855 | 7.80 | hrpY | Type III secretion system protein HrpY |

| RSUY_RS19795 | RSUY_40640 | RSp0877 | 4.66 | popA | Type III effector protein PopA | |

| RSUY_RS19790 | RSUY_40630 | RSp0876 | 4.27 | popB | Type III effector protein PopB | |

| RSUY_RS20380 | RSUY_41860 | RSp1024 | 3.96 | awr5_1 | Type III effector protein AWR5 | |

| RSUY_RS22080 | RSUY_45370 | RSp0900 | 3.94 | popF1 | Type III effector protein PopF1 | |

| RSUY_RS16550 | RSUY_33840 | RSp0304 | 3.76 | ripD | Type III effector protein RipD | |

| RSUY_RS19785 | RSUY_40620 | RSp0875 | 3.35 | popC | Type III effector protein PopC | |

| RSUY_RS19735 | RSUY_40520 | RSp0865 | 3.08 | hrpK | Type III secretion system protein HrpK | |

| RSUY_RS19690 | RSUY_40430 | RSp0856 | 2.86 | hrpX | Type III secretion system protein HrpX | |

| RSUY_RS19770 | RSUY_40590 | RSp0872 | 2.69 | hrcT | HrcT family type III secretion system export apparatus protein | |

| RSUY_RS09370 | RSUY_19160 | − | 2.44 | ripV2 | Type III effector protein RipV2 | |

| RSUY_RS19150 | RSUY_39290 | RSp0731 | −2.61 | ripTPS | Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase | |

| RSUY_RS21730 | RSUY_44630 | RSp1374 | −2.88 | ripS2 | Type III effector protein SKWP2 | |

| RSUY_RS21610 | RSUY_44390 | RSp1277 | −3.50 | ripQ | Type III effector protein RipQ | |

| Motility | RSUY_RS04635 | RSUY_09450 | RSc0727 | 3.14 | pilV | Type IV pilus modification protein PilV |

| RSUY_RS22435 | RSUY_46110 | RSp1412 | 2.65 | flhC | Transcriptional activator FlhC | |

| RSUY_RS02415 | RSUY_04970 | RSc2974 | 2.62 | pilN | Tfp pilus assembly protein PilN | |

| RSUY_RS22440 | RSUY_46120 | RSp1413 | 2.47 | flhD | Flagellar transcriptional activator FlhD | |

| RSUY_RS04630 | RSUY_09440 | RSc0726 | 2.30 | pilW | Pilus assembly protein PilW | |

| RSUY_RS02410 | RSUY_04960 | RSc2975 | 2.28 | pilM | Pilus assembly protein PilM | |

| RSUY_RS04330 | RSUY_08850 | RSc0668 | 2.20 | pilG | Two-component system response regulator | |

| RSUY_RS04335 | RSUY_08860 | RSc0669 | 1.95 | pilH | Two-component system response regulator | |

| RSUY_RS11250 | RSUY_22930 | RSc1986 | 1.24 | fimV | Tfp pilus assembly protein FimV | |

| RSUY_RS04590 | RSUY_09370 | RSc0718 | −3.56 | pilY | Pilus assembly protein PilY | |

| Stress responses | RSUY_RS22220 | RSUY_45660 | RSp1581 | 3.16 | katE | Catalase katE |

| RSUY_RS00425 | RSUY_00900 | RSc3398 | 3.10 | hmpX | flavohemoprotein | |

| RSUY_RS17495 | RSUY_35830 | RSp0245 | 2.64 | ahpC1 | Peroxiredoxin | |

| RSUY_RS17500 | RSUY_35840 | RSp0246 | 2.21 | ahpF | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F | |

| RSUY_RS04770 | RSUY_09720 | RSc0754 | 1.96 | − | Peroxidase | |

| RSUY_RS04870 | RSUY_09930 | RSc0775 | 1.82 | katGb | Catalase katGb | |

| RSUY_RS01185 | RSUY_02450 | RSc3254 | −3.11 | − | alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | |

| Other virulence factors | RSUY_RS18925 | RSUY_38830 | RSp0676 | 3.71 | metE | Methionine synthase II (cobalamin-independent) |

| RSUY_RS01465 | RSUY_03030 | RSp0693 | 3.38 | hdfA | Dioxygenase | |

| RSUY_RS14015 | RSUY_28660 | RSc0408 | 2.22 | rpoN1 | RNA polymerase sigma-54 factor | |

| RSUY_RS17795 | RSUY_36440 | RSp1529 | 1.72 | efe | 2-oxoglutarate-dependentethylene/succinate-forming enzyme | |

| RSUY_RS04455 | RSUY_09100 | RSc0693 | −2.19 | kdtA | 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic-acid transferase | |

| Type II Secretion System | RSUY_RS01675 | RSUY_03470 | RSc3109 | −2.63 | gspJ | General secretion pathway protein GspJ |

| RSUY_RS16275 | RSUY_33280 | RSp0148 | −3.19 | gspE | General secretion pathway protein GspE | |

| Type VI secretion system | RSUY_RS19215 | RSUY_39440 | RSp0746 | 2.25 | − | Type VI secretion protein |

| Cofactor metabolism and transport | RSUY_RS04050 | RSUY_08280 | RSc2633 | −2.92 | pabB | aminodeoxychorismate synthase component I |

| Quorum sensing | RSUY_RS01010 | RSUY_02100 | RSc3286 | −3.24 | solI | Acyl-homoserine-lactone synthase |

| RALSTONIA SOLANACEARUM GENES INVOLVED IN PLANT COLONIZATION | ||||||

| Aminoacid metabolism | RSUY_RS21930 | RSUY_45070 | RSp1263 | 2.019462 | nadB2 | L-aspartate oxidase |

| RSUY_RS04790 | RSUY_09760 | RSc0758 | 1.900185 | − | Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase 1 | |

| RSUY_RS01705 | RSUY_03530 | RSc3103 | −1.93219 | − | 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | |

| RSUY_RS00955 | RSUY_01990 | RSc3295 | −1.97096 | gcvP | glycine dehydrogenase | |

| RSUY_RS00965 | RSUY_02010 | RSc3293 | −2.1387 | gcvT | aminomethyltransferase | |

| RSUY_RS08880 | RSUY_18160 | RSc1381 | −2.22786 | − | glutathione ABC transporter permease GsiC | |

| RSUY_RS02965 | RSUY_06080 | RSc2867 | −2.45751 | dppD1 | peptide ABC transporter substrate-bindingprotein | |

| RSUY_RS19000 | RSUY_38980 | RSp0691 | −2.63642 | hmgA | homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase | |

| RSUY_RS08860 | RSUY_18120 | RSc1377 | −2.72373 | − | transcriptional regulator | |

| RSUY_RS00950 | RSUY_01980 | RSc3296 | −2.82715 | sdaA2 | L-serine ammonia-lyase / L-serine ammonia-lyase | |

| RSUY_RS18995 | RSUY_38970 | RSp0690 | −2.93699 | hmgB | fumarylacetoacetase | |

| RSUY_RS08895 | RSUY_18190 | RSc1384 | −3.10843 | − | D-aminopeptidase | |

| RSUY_RS08865 | RSUY_18130 | RSc1378 | −3.44342 | − | isoaspartyl peptidase | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | RSUY_RS22935 | RSUY_47230 | RSp1633 | −1.90617 | xylF | D-xylose ABC transporter substrate-bindingprotein |

| RSUY_RS22945 | RSUY_47250 | RSp1635 | −2.40016 | xylH | xylose ABC transporter permease | |

| RSUY_RS21965 | RSUY_45140 | RSp1270 | −2.4781 | − | glycosyl hydrolase | |

| RSUY_RS22940 | RSUY_47240 | RSp1634 | −2.98048 | xylG | D-xylose ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| RSUY_RS17060 | RSUY_34910 | RSp0423 | −3.65067 | − | aldolase | |

| RSUY_RS22950 | RSUY_47260 | RSp1636 | −4.75552 | − | NAD-dependent dehydratase | |

| Transcriptional and response regulators | RSUY_RS08455 | RSUY_17320 | RSc1295 | 4.365537 | − | MarR family transcriptional regulator |

| RSUY_RS22955 | RSUY_47270 | RSp1637 | −1.62836 | − | LacI family transcriptional regulator | |

| RSUY_RS06090 | RSUY_12470 | RSc2209 | −1.75486 | − | LysR family transcriptional regulator | |

| RSUY_RS00225 | RSUY_00480 | RSc0040 | −2.26596 | − | two-component system response regulator | |

| RSUY_RS00910 | RSUY_01900 | RSc3301 | −2.57757 | putA | trifunctional transcriptional regulator | |

| Siderophore biosynthesis | RSUY_RS17055 | RSUY_34900 | RSp0422 | −2.30463 | − | siderophore biosynthesis protein |

| RSUY_RS03590 | RSUY_07350 | RSc2729 | −2.4997 | − | membrane protein / membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS17040 | RSUY_34870 | RSp0419 | −2.75083 | − | siderophore biosynthesis protein | |

| RSUY_RS17050 | RSUY_34890 | RSp0421 | −2.94313 | − | siderophore biosynthesis protein | |

| Nitrogen metabolism | RSUY_RS14025 | RSUY_28680 | RSc0406 | 2.27 | ptsN | PTS IIA-like nitrogen-regulatory protein PtsN |

| RSUY_RS17995 | RSUY_36860 | RSp0980 | 2.24 | narL | DNA-binding response regulator | |

| RSUY_RS11470 | RSUY_23380 | RSc2031 | −3.3167 | ureE | urease accessory protein UreE | |

| Transporters | RSUY_RS20760 | RSUY_42660 | RSp1283 | 2.005142 | − | porin |

| RSUY_RS11090 | RSUY_22610 | RSc1951 | −2.22 | − | cation acetate symporter | |

| RSUY_RS22930 | RSUY_47220 | RSp1632 | −2.42488 | oprB | porin | |

| RSUY_RS05795 | RSUY_11880 | RSc2274 | −2.96894 | ragC | Cation efflux protein | |

| Organic acid metabolism | RSUY_RS19540 | RSUY_40110 | RSp0826 | 3.403389 | − | 5-dehydro-4-deoxyglucarate dehydratase |

| RSUY_RS19480 | RSUY_39990 | RSp0814 | 2.44631 | mqo | malate:quinone oxidoreductase | |

| RSUY_RS11960 | RSUY_24410 | RSc2358 | −1.7429 | ppc | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | |

| Proteases | RSUY_RS12475 | RSUY_25460 | RSc2465 | 2.359347 | clpS | ATP-dependent Clp protease adaptor ClpS |

| RSUY_RS18550 | RSUY_38040 | RSp0603 | 2.211049 | − | serine protease | |

| RSUY_RS14120 | RSUY_28870 | RSc0388 | −1.98903 | − | zinc protease | |

| Lipid metabolism | RSUY_RS17295 | RSUY_35410 | − | 2.478807 | − | Acyl-CoA synthetase |

| RSUY_RS01975 | RSUY_04090 | RSc3052 | −2.40887 | glpK | glycerol kinase | |

| Energy | RSUY_RS08510 | RSUY_17430 | RSc1305 | 3.640811 | fpr | ferredoxin–NADP(+) reductase |

| RSUY_RS08360 | RSUY_17120 | RSc1276 | 3.417949 | − | cytochrome c oxidase, cbb3-type subunit I | |

| Signal transduction | RSUY_RS23055 | RSUY_47460 | RSc0617 | 1.988909 | − | signal peptidase |

| RSUY_RS01700 | RSUY_03520 | RSc3104 | 1.73953 | − | calcium sensor EFh | |

| Stress related | RSUY_RS13090 | RSUY_26760 | RSc0582 | 2.610905 | − | avrD-like protein |

| RSUY_RS21705 | RSUY_44580 | RSp1306 | −2.11404 | speE2 | spermidine synthetase | |

| Cofactor metabolism and transport | RSUY_RS02845 | RSUY_05840 | RSc2886 | −2.57058 | − | adenylate cyclase |

| Recombination and repair | RSUY_RS07890 | RSUY_16140 | RSc1189 | −2.09233 | − | recombinase RecB |

| Translation | RSUY_RS15445 | RSUY_31580 | RSc0085 | −2.70405 | cca | multifunctional CCA protein |

| Hypothetical proteins | RSUY_RS19605 | RSUY_40240 | − | 4.758974 | − | hypothetical protein |

| RSUY_RS17575 | RSUY_35990 | RSp0261 | 4.146986 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS16950 | RSUY_34650 | RSp0403 | 3.74634 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS22040 | RSUY_45290 | RSp0982 | 3.589851 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS12885 | RSUY_26330 | RSc0613 | 3.409348 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS08290 | RSUY_16960 | RSc1262 | 3.394474 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS06775 | RSUY_13900 | RSc0971 | 3.025981 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS20375 | RSUY_41850 | − | 3.019263 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS01105 | RSUY_02290 | RSc3270 | 2.806237 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS15470 | RSUY_31630 | RSc0080 | 2.792044 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS14600 | RSUY_29830 | RSc0297 | 2.641501 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS05760 | RSUY_11810 | RSc2280 | 2.552951 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS10215 | RSUY_20850 | RSc1622 | 2.233892 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS12820 | RSUY_26200 | − | 2.213444 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS22015 | RSUY_45240 | RSp1546 | 2.185718 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS01435 | RSUY_02950 | RSc0616 | 2.148496 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS06705 | RSUY_13730 | RSc0953 | 2.116755 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS01875 | RSUY_03890 | RSc3072 | 2.098485 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS04190 | RSUY_08560 | RSc2555 | 1.909667 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS05940 | RSUY_12170 | RSc2238 | 1.775776 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS04990 | RSUY_10170 | RSc0799 | −1.56204 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS02135 | RSUY_04410 | RSc3030 | −2.05111 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| RSUY_RS20585 | RSUY_42270 | − | −2.22451 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS14980 | RSUY_30600 | RSc0211 | −2.4077 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS17045 | RSUY_34880 | RSp0420 | −2.58002 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS15175 | RSUY_31000 | RSc0146 | −2.83465 | − | hypothetical protein | |

| PUTATIVE VIRULENCE GENES AND PLANT COLONIZATION METABOLIC ACTIVITIES | ||||||

| Transporters | RSUY_RS00490 | RSUY_01050 | RSc3386 | 3.50 | − | metal ABC transporter substrate-binding protein |

| RSUY_RS17605 | RSUY_36050 | RSp0429 | 3.24 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS20020 | RSUY_41100 | RSp0931 | 2.92 | − | ABC transporter | |

| RSUY_RS19045 | RSUY_39070 | RSp0706 | −1.77 | − | metal-dependent hydrolase | |

| RSUY_RS18205 | RSUY_37320 | RSp0481 | −2.03 | − | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | |

| RSUY_RS18195 | RSUY_37300 | RSp0479 | −2.09 | − | amino acid ABC transporter ATPase | |

| RSUY_RS21220 | RSUY_43600 | RSp1181 | −2.11 | − | transporter | |

| RSUY_RS18895 | RSUY_38770 | RSp0670 | −2.14 | − | acriflavine resistance protein B / transporter protein | |

| RSUY_RS17425 | RSUY_35690 | RSp0234 | −2.37 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS09885 | RSUY_20190 | RSc1738 | −2.40 | − | ABC transporter ATPbinding protein | |

| RSUY_RS21615 | RSUY_44400 | RSp1278 | −2.49 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS21315 | RSUY_43800 | RSp1200 | −2.60 | − | RND transporter | |

| RSUY_RS03020 | RSUY_06190 | RSc2856 | −2.72 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS01560 | RSUY_03230 | RSc3134 | −2.94 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS06940 | RSUY_14230 | RSc1002 | −2.95 | − | membrane protein | |

| RSUY_RS15855 | RSUY_32410 | − | −2.98 | oprM | RND transporter | |

| RSUY_RS20395 | RSUY_41890 | − | −2.99 | ybtP | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| RSUY_RS15985 | RSUY_32660 | RSp0078 | −3.05 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS18200 | RSUY_37310 | RSp0480 | −3.17 | − | amino acid ABC transporter permease | |

| RSUY_RS19050 | RSUY_39080 | RSp0707 | −3.19 | − | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| RSUY_RS21055 | RSUY_43260 | RSp1114 | −3.35 | − | RND transporter | |

| RSUY_RS01890 | RSUY_03920 | RSc3069 | −3.50 | − | MFS transporter | |

| RSUY_RS22255 | RSUY_45730 | RSp1595 | −3.73 | − | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| RSUY_RS04055 | RSUY_08290 | RSc2632 | −3.85 | − | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| Lipid metabolism | RSUY_RS14075 | RSUY_28780 | RSc0396 | 3.29 | ipk | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-D-erythritolkinase |

| RSUY_RS10705 | RSUY_21830 | RSc1540 | 3.14 | − | acyltransferase | |

| RSUY_RS19325 | RSUY_39670 | − | 2.15 | − | Phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylglycerophosphate/cardiolipin synthase | |

| RSUY_RS09620 | RSUY_19650 | RSc1772 | −2.06 | − | alpha/beta hydrolase | |

| RSUY_RS14790 | RSUY_30210 | RSc0262 | −2.17 | − | glyoxylate/hydroxypyruvate reductase A | |

| RSUY_RS00675 | RSUY_01440 | RSc3346 | −2.24 | − | alpha/beta hydrolase | |

| RSUY_RS13905 | RSUY_28430 | RSc0427 | −2.30 | − | beta-ketoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthaseII | |

| RSUY_RS09090 | RSUY_18590 | − | −2.77 | − | Lysophospholipase | |

| RSUY_RS01035 | RSUY_02150 | RSc3283 | −2.82 | glxR | 2-hydroxy-3-oxopropionate reductase | |

| RSUY_RS10955 | RSUY_22330 | RSc1874 | −2.82 | − | NUDIX hydrolase | |

| RSUY_RS14265 | RSUY_29170 | RSc0357 | −2.86 | gpsA | glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD(P)(+)) | |

| RSUY_RS11775 | RSUY_23990 | RSc2091 | −3.04 | − | ABC transporter permease | |

| RSUY_RS15945 | RSUY_32580 | RSp0036 | −3.05 | − | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | |

| RSUY_RS21855 | RSUY_44890 | RSp1245 | −3.30 | − | esterase | |

| RSUY_RS20415 | RSUY_41930 | − | −3.31 | − | Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase | |

| RSUY_RS21590 | RSUY_44350 | − | −3.32 | − | Dehydrogenases | |

| RSUY_RS20425 | RSUY_41950 | − | −3.60 | − | Polyketide synthase | |

| RSUY_RS14720 | RSUY_30070 | RSc0275 | −3.61 | − | short-chain dehydrogenase | |

| RSUY_RS10105 | RSUY_20630 | RSc1643 | −4.27 | ispD | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphatecytidylyltransferase | |

| Other putative virulence factors | RSUY_RS16085 | RSUY_32860 | RSp0112 | 2.09 | − | carbonic anhydrase |

| RSUY_RS00735 | RSUY_01550 | RSp0085 | 1.66 | − | type IV secretion protein Rhs | |

| RSUY_RS00905 | RSUY_01890 | RSc3302 | −2.04 | priA | primosomal protein N' | |

| RSUY_RS15535 | RSUY_31760 | RSc0068 | −2.06 | smf | DNA processing protein DprA | |

| RSUY_RS14955 | RSUY_30550 | RSc0222 | −2.29 | rtcR | Fis family transcriptional regulator | |

| RSUY_RS17190 | RSUY_35180 | RSp0181 | −3.10 | − | activator of HSP90 ATPase | |

| RSUY_RS14940 | RSUY_30520 | RSc0226 | −3.23 | rtcA | RNA 3'-terminal phosphate cyclase | |

| Sulfur metabolism and transport | RSUY_RS12265 | RSUY_25040 | RSc2425 | 3.22 | cysI1 | Sulfite reductase/sulfite reductase |

| RSUY_RS07020 | RSUY_14390 | RSc1019 | 2.23 | nifS | Cysteine desulfurase IscS | |

| RSUY_RS12250 | RSUY_25010 | RSc2422 | 2.14 | cysD | Sulfate adenylyltransferase small subunit | |

| RSUY_RS12245 | RSUY_25000 | RSc2421 | 1.89 | cysN | Sulfate adenylyltransferase | |

| RSUY_RS07025 | RSUY_14400 | RSc1020 | 1.60 | nifU | Iron-sulfur cluster scaffold-like protein | |

| RSUY_RS17845 | RSUY_36540 | RSp1519 | −3.36 | − | Membrane protein | |

| Cofactor metabolism and transport | RSUY_RS11705 | RSUY_23850 | RSc2077 | 1.85 | ilvI | acetolactate synthase |

| RSUY_RS18660 | RSUY_38270 | RSp0615 | −2.97 | cbiA | cobyrinic acid a,c-diamide synthase | |

| RSUY_RS18690 | RSUY_38330 | RSp0621 | −2.97 | cbiL | precorrin-2 C(20)-methyltransferase | |

| RSUY_RS18680 | RSUY_38310 | RSp0619 | −3.00 | cbiG | cobalamin biosynthesis protein CbiG | |

| RSUY_RS03905 | RSUY_07990 | RSc2663 | −3.51 | − | ATP:cob(I)alamin adenosyltransferase | |

| Phosphate mobilization | RSUY_RS10765 | RSUY_21950 | RSc1529 | 2.01 | pstS1 | phosphate ABC transporter substrate-bindingprotein PstS |

| RSUY_RS07715 | RSUY_15790 | RSc1160 | 1.63 | suhB | Inositol monophosphatase | |

| RSUY_RS10750 | RSUY_21920 | RSc1532 | 1.52 | pstB | phosphate ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

Taken together, these results show a major induction of stress-related activities and an inhibition of the central metabolism when the bacterium grows in planta compared to synthetic media.

R. solanacearum virulence genes are differentially expressed in wild potato roots

Among the 422 genes DE during S. commersonii root colonization, 34% (80 induced and 65 repressed genes) had been identified in previous studies analyzing gene expression of R. solanacearum cells recovered from infected plant stems (see references below). Notably, 73 genes were also DE in microarray analyses of R. solanacearum UW551 -a phylotype IIB strain highly similar to UY031- isolated from tomato (Jacobs et al., 2012). Also, 42 genes have been shown to be induced in a temperature-dependent manner when bacteria grew in tomato xylem or rhizosphere (Bocsanczy et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2015). In addition, 31 DE genes (most of them induced in planta) are part of either the HrpB or HrpG regulons, which are known to trigger expression of the T3SS and other virulence genes in response to direct plant cell contact (Valls et al., 2006).

Amongst the R. solanacearum genes induced during plant colonization, 31 encode already reported virulence traits (Table 3). As expected, genes encoding the T3SS (hrpY, hrpX, hrpK, hrcT) and some of its related effectors (ripV2, popC, ripD, popF1, awr5_1, popB, and popA) were induced inside the plant (Boucher et al., 1987; Cunnac et al., 2004). Motility and adherence genes were also up-regulated, including type IV pili (pilG, pilH, pilN, pilM, pilY, pilW, and fimV), as well as the transcriptional activators of the flagellum genes flhC and flhD (Kang et al., 2002; Tans-Kersten et al., 2004). Other induced genes encoding described factors that are key for bacterial virulence included hdfA (Delaspre et al., 2007), efe (Valls et al., 2006), metE (Plener et al., 2012), and rpoN1 (Lundgren et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2015; Table 3). Peroxidases, catalases (katE, katG) and alkyl hydroperoxide reductases (ahpC1, ahpF), which have been described to combat the oxidative stress response during plant infection (Rocha and Smith, 1999; Flores-Cruz and Allen, 2009; Ailloud et al., 2016) were also induced. Similarly, the flavohemoprotein hmpX, involved in NO-detoxification (Dalsing and Allen, 2014), was also induced.

In contrast, only 10 reported virulence determinants were down-regulated, including the type III effectors ripQ, ripS2, and ripTPS, the quorum sensing regulator solI (Flavier et al., 1997) and the Type II secretion system genes gspE, gspJ (Table 3).

R. solanacearum genes for plant colonization are differentially expressed in S. commersonii roots

Thirty-six R. solanacearum genes previously described as related to plant colonization in gene expression studies in other plant species were also induced in potato. Few metabolic genes were induced in planta, being an exception nadB2, involved in the degradation of L-aspartate in the xylem (Brown and Allen, 2004) and the ptsN and narL nitrogen metabolism genes, known to be active during plant colonization (Dalsing and Allen, 2014; Dalsing et al., 2015; Table 3).

Amongst the down-regulated genes, 42 had also been described as specifically down-regulated during plant colonization (Jacobs et al., 2012). Most repressed genes encoded metabolic enzymes and transporters. Examples are the xylose transporters xylF, xylG, and xylH, glycine catabolism genes gcvP, gcvT, and gcvA, the adenilate cyclase coding gene RSUY_RS02845, four siderophore biosynthesis genes and 11 genes involved in amino acid metabolism (Table 3). Also, the stress response gene speE2 and five transcriptional and response regulators were repressed in planta.

Novel putative virulence genes and metabolic traits involved in early stages of wild potato infection by R. solanacearum

Transcriptomic analysis of S. commersoni early root infection revealed highly induced R. solanacearum virulence factors still uncharacterized in this pathogen that may play a role at this stage of the interaction with the host. An example of this is suhB, a global virulence regulator controlling the type III and type VI secretion systems, flagellum biosynthesis, and biofilm formation in the human pathogens Burkholderia cenocepacia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Rosales-Reyes et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). Similarly, a P. aeruginosa orthologue of the in planta induced type IV secretion gene Rhs has been described as a virulence determinant (Kung et al., 2012).

Metabolic traits that might be key at this point of plant infection are the assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway and phosphate mobilization, since cysD, cysN, and cysI (sulfate reduction) and pstB and pstS1 (phosphate mobilization) were induced during S. commersonii root infection. Also, carbonic anhydrase (RSUY_RS16085), which plays a role in disease establishment between potato and Phytophthora infestans (Restrepo et al., 2005), was also found to be up-regulated in the R. solanacearum interaction with wild potato.

The most important category amongst the R. solanacearum genes down-regulated in S. commersonii with so far no assigned functions in plant colonization or virulence was metabolite transporters. Almost half of these corresponded to the ABC-family, including five amino acid transporters. In contrast, the seven major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters found in this category are involved with carbohydrate transport. The rest of genes were classified as permeases or RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) efflux systems (Table 3). The major metabolic activities identified as repressed in planta for the first time were lipid mobilization and cofactor metabolism, such as the anaerobic cobalamin biosynthesis operon (cbiA, cbiG, and cbiL), and stress-response genes such as rtcA and rtcR, involved in RNA repair (Das and Shuman, 2013).

In sum, our work reflects important gene expression changes between parasitic life and growth in rich medium (see below). This was corroborated by the fact that seven genes annotated as response regulators were also DE, five of them induced (Table 3).

Discussion

Some R. solanacearum virulence and stress-responsive genes are induced irrespective of the plant host

1/3 of the R. solanacearum genes DE during potato infection had been also found DE when the bacterium colonized other plant species and many of these correspond to virulence determinants. For instance, we found that genes encoding the type III secretion system and its associated effectors (popA, popB, popC, popF1, ripD, ripV2, and awr5_1) were induced in potato (Table 3). Except for awr5_1, all these effectors had already been described as up-regulated when the bacterium grew in tomato and in melon (Ailloud et al., 2016), likely indicating that they are part of the minimal gene set required for bacterial virulence. Similarly, the effector ripTPS was down-regulated both in potato (Table 3) and during the interaction with melon (Ailloud et al., 2016). Also sharing similar up-regulation in potato (Table 3) and tomato are the transcriptional activators flhC and flhD (Jacobs et al., 2012), which regulate flagellum-encoding genes (Tans-Kersten et al., 2004) and the nitrogen metabolism genes narL, ptsN, and hmpX (Dalsing and Allen, 2014; Dalsing et al., 2015), implying that they all play a key role during plant infection. Additional genes induced during potato colonization had been described as key for virulence on other plant hosts, including small molecule hdfA (Delaspre et al., 2007), the ethylene forming enzyme efe (Valls et al., 2006), the methionine metabolism gene metE (Plener et al., 2012) and the alternative sigma factor rpoN1 (Lundgren et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2015). These factors may be also considered essential for growth in planta, irrespective of the infected species.

Several transposable elements had been identified in an in vivo screening for genes expressed during R. solanacearum growth in tomato plants (Brown and Allen, 2004), and we found 16 transposases up-regulated in potato (Table 3). This may reflect common stressing conditions in various plant hosts, as stress is known to turn on transcription of transposable elements in various organisms (Capy et al., 2000). Oxidative stress seems also a condition generally encountered by R. solanacearum in plant tissues, as peroxidases, catalases, and peroxiredoxins, required for the bacterium to combat this stress in different plants (Rocha and Smith, 1999; Flores-Cruz and Allen, 2009; Ailloud et al., 2016), were also induced in potato.

Changes in the host environment and/or the disease stage may account for opposing bacterial virulence gene expression in different plants

Some of the R. solanacearum virulence genes DE in potato showed opposite trends in other host plants. ripQ and ripS2, two of the three type III secreted effectors inhibited in potato were, respectively, upregulated and not DE in melon, tomato and banana (Ailloud et al., 2016). Interestingly, these two downregulated effectors, together with the also repressed stress response gene speE2, are located in a genomic region that is deleted in the avirulent R. solanacearum strain UY043 (Siri et al., 2014), which suggests their involvement in bacterial virulence. Similarly, the effector awr5_1, which was described to trigger hypersensitive response (HR) in tobacco and to inhibit the TOR pathway (Sole et al., 2012; Popa et al., 2016b), showed opposite regulation in potato when compared to tomato and melon (Ailloud et al., 2016), suggesting that it may play host-specific roles. Similarly, genes pilG, pilH, pilN, pilM, pilY, and pilW, coding for structural components of the type IV pili involved in twitching motility and adherence (Liu et al., 2001; Kang et al., 2002) were induced in the current work but repressed in other plant species (Jacobs et al., 2012).

In addition, some virulence determinants well-described as induced during growth in planta were repressed or not DE in potato. Remarkably, the exopolysaccharide synthesis and regulation genes (eps) as well as most known cell wall degrading enzymes (pehA, pehB, pehC, egl, and cbhA), which are virulence determinants (Schell, 2000) induced during tomato infection (UW551 strain) infection (Jacobs et al., 2012) were absent from the potato DE dataset.

Differences in the host environment or in the tissue environment and disease stage are the two most plausible reasons for the discrepancies between virulence gene expression data in potato and in other plant hosts. We favor the latter explanation, as our samples were collected from bacteria growing in the root (including apoplastic and xylematic bacteria) at early times after inoculation while all previous transcriptomic work had been performed from bacteria extracted from xylem at later infection stages.

Three independent observations support the existence of stage-specific environmental cues that differentially affect gene expression in this work compared to previous studies. First, genes that are induced at high bacterial densities are absent from the potato DE genes. Examples are the mentioned exopolysaccharide synthesis genes or the quorum sensing regulator solI, repressed in our conditions but slightly induced in bacteria isolated from the tomato shoot xylem (Jacobs et al., 2012). In the low bacterial cell densities in the roots the phcA cell-density regulator was not induced, impeding solI or eps expression (Huang et al., 1995; Flavier et al., 1997). Second, three out of the six type III effectors that are induced in potato were described as secreted at early stages (Lonjon et al., 2016), two of them (popF1 and popA) also proposed to play an important role in the first steps of infection (Kanda et al., 2003). On the contrary, only two out of the 38 described as “late” effectors (ripD and popC) were induced in our root transcriptome. Third, the afore-mentioned transcriptional regulators flhC and flhD responsible for the activation of the flagellum genes were up-regulated in potato root samples (Table 3) and also in the tomato xylem (Jacobs et al., 2012), but only in the latter were the flagellum structural genes induced, suggesting that the potato transcriptome represents an earlier stage where complete activation of this regulon has not yet occurred. These observations imply that our transcriptome represents a snapshot of a precise stage of the genetic programs deployed consecutively during plant colonization.

Finally, we cannot rule out that changes in R. solanacearum DE genes in different studies are due to the use of different strains. Differing transcriptomes of two R. solanacearum strains in the same plant environment have already been reported (Ailloud et al., 2016). However, the fact that previous gene expression studies were performed with strain UW551, which is genetically extremely close to UY031 used here, render this explanation unlikely. Standardization of the plant inoculation and sampling procedures and a systematic analysis of plant-pathogen interactions dissecting gene expression over time in a defined strain-host pathosystem would clarify the nature of the observed discrepancies between transcriptomic studies.

The R. solanacearum metabolic state during potato root colonization

From the transcriptomic information gathered in this work, we can infer for the first time the environmental conditions encountered by R. solanacearum in the root, the site where plant infection takes place.

A first observation is that the bacterium seems to start to run out of O2. An indication of this is the highly induced Cbb3-cco, a high affinity cytochrome c oxidase known to contribute to the growth of R. solanacearum and other bacteria in microaerobic or anoxic environments (Colburn-Clifford and Allen, 2010; Hamada et al., 2014), such as the plant xylem (Pegg, 1985). Upregulation of the low O2 affinity cytochrome ubiquinol oxidase genes cyoA1 and cyoB1 reinforces the notion of a microaerobic rather than an anoxic environment. In agreement with this, nrdB, which is required for growth in aerobiosis (Casado et al., 1991), was up-regulated, and nrdG and nrdD, required in strict anaerobiosis (Garriga et al., 1996; Ailloud et al., 2016) were not induced. Further, the cbiA, cbiL, and cbiG genes, which are involved in anaerobic cobalamin synthesis (Roessner and Scott, 2006), were repressed. Another indication of microaerobic conditions is the induction of genes driving nitrate and sulfate anaerobic respiration. Examples are the cys genes, involved in the assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway (Kredich, 1992), ptsN—a nitrogen-dependent regulatory protein, rpoN1, -the global nitrogen regulator- and narL -the nitrate/nitrite-responsive transcriptional regulator- were all induced in wild potato roots. All these findings suggest that during early root infection R. solanacearum is experiencing the transition from an aerobic environment to the anaerobic conditions established at the onset of disease during xylem colonization (Ailloud et al., 2016).

Another take home message from the root transcriptomes is that few central metabolic pathways seem to be active. It was previously described that a large proportion of the R. solanacearum genes involved in amino acid metabolism and transport was down-regulated during growth in the xylem (Ailloud et al., 2016) and we found that this was also the case during growth in the root tissues at early stages of infection. For instance, the glycine catabolism genes gcvP, gcvT, and gcvA as well as the dipeptide uptake gene dppD1 were repressed in both cases (Table 3; Ailloud et al., 2016). Other R. solanacearum metabolic genes previously known to be repressed in planta also down-regulated here included carbohydrate metabolism genes such as the xylose transporter operon xylFGH and Glucosamine 6-phosphate synthetase, the key enzyme controlling amino sugar biosynthesis (Milewski, 2002; Jacobs et al., 2012). Lipid metabolism was also strikingly repressed during root colonization. Out of the 21 DE genes involved in lipid mobilization, only 2 have been found in previous gene expression studies in R. solanacearum (Table 3; Jacobs et al., 2012). Thus, the downregulation of lipid metabolism could be specific to early infection stages or to wild potato colonization. In this sense, lipid metabolism has been reported to play an important role during plant-host interactions by modulating defense responses in plants and pathogen infection (Casadevall and Pirofski, 2001; Wenk, 2006). Cofactor metabolism was also repressed including the folate synthesis gene pabB (Table 3), already known to be down-regulated in planta (Shinohara et al., 2005), the cobalamin biosynthesis genes and adenilate cyclase. Repression of adenylate cyclase, which is a global metabolic regulator in bacteria (Ullmann and Danchin, 1980), illustrates the magnitude of the metabolic shutdown experienced by R. solanacearum in the roots of S. commersonii.

In contrast with the global metabolic shutdown, aspartate and tryptophan catabolism genes were up-regulated when R. solanacearum grew in the plant roots. The aspartate catabolism gene nadB2 had already been identified as an essential gene for in planta growth in an in vivo screening (Brown and Allen, 2004). Interestingly, aspartate is the second most abundant aminoacid in the tomato apoplast and less so in the xylem (Zuluaga et al., 2013), which is in agreement with the bacterium mostly thriving in the apoplastic root spaces at the early infection times analyzed. Also induced was the Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Concentrations of this aminoacid are high at lateral root emergence sites (Jaeger et al., 1999), and it was suggested that it is also present in the tomato apoplast (Yu et al., 2013). Induction of tryptophan catabolism would thus be indicative of early plant colonization.

These results likely indicate the existence of a trade-off between the expression of virulence and metabolic genes. This has already been described in a previous study where the quorum-sensing-dependent regulatory protein PhcA regulated a trade-off between production of R. solanacearum exopolysaccharides and bacterial proliferation (Peyraud et al., 2016).

Proposed new virulence determinants important for early root colonization

RSUY_RS08455 and RSUY_RS16950 were found to be upregulated in a resistant S. commersonii accession compared to a susceptible one (Table 2), as well as during root colonization compared to rich medium (Table 3). Although these genes also appeared in the microarray transcriptome of bacteria extracted from infected tomato xylem vessels (Jacobs et al., 2012), they have not been characterized.

Similarly, the gene encoding an avrD-like protein was up-regulated in tomato xylem (Jacobs et al., 2012) and in wild potato (Table 3). AvrD is required in P. syringae for the synthesis of syringolide, small molecules that can elicit a hypersensitive response on resistant plants (Keen et al., 1990; Mucyn et al., 2014). In R. solanacearum the avrD-like protein encoding gene is activated by the master virulence regulator HrpG (Valls et al., 2006). Considering the persistence of these three genes among the up-regulated during plant colonization, we suggest that they encode for potential virulence factors, probably necessary independently of the host or the infection stage.

Three genes found up-regulated in S. commersonii (suhB, rhs and the carbonic anhydrase gene RSUY_RS16085, Table 3) have been involved in bacterial virulence on animals and constitute putative virulence genes in R. solanacearum. Although classified as a phosphate mobilization gene (Table 3), suhB is a super-regulator involved in the proper rRNA folding (Singh et al., 2016). It plays a role in virulence of animal bacterial pathogens, influencing T3SS, T6SS, flagellum and biofilm regulation and probably acts in opposite ways in different bacteria (Rosales-Reyes et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). Interestingly, SuhB differential expression was also observed in two R. solanacearum strains (Meng et al., 2015). The function of Rhs (Rearrangement Hot Spot) proteins is ill-defined but they are considered to promote recombination (Lin et al., 1984). Interestingly, a member of the Rhs family was described to be induced during infection and associated with increased bacterial numbers and decreased survival in mice during pneumonia caused by P. aeruginosa (Kung et al., 2012). Finally, carbonic anhydrase catalyzes the inter-conversion between carbon dioxide and bicarbonate but is also required for growth of many animal pathogenic microorganisms (Capasso and Supuran, 2015). In addition, a role in disease establishment between potato and Phytophthora infestans was also reported (Restrepo et al., 2005), suggesting the possible implication of CAs during host colonization. These evidences suggest that suhB, rhs, and RSUY_RS16085 encode putative virulence factors shared between gram-negative bacterial pathogens that infect animals and plants.

The assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway (cysD, cysN, and cysI) and the phosphate mobilization (pstB and pstS1) were also induced during root colonization (Table 3). cysD and cysN, encode an ATP sulfurylase that produces APS, which can be in turn reduced to PAPS to ultimately synthesize cysteine by cysI. A study carried out in a closely related plant pathogenic bacterium, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae, was demonstrated that mutation of either raxP or raxQ (homologs of cysD and cysN) impaired production of APS and PAPS and were required for the correct activity of the avirulence protein AvrXa21 (Shen et al., 2002). Further, several studies demonstrated that mutations on the pst system, responsible for phosphate uptake, affected virulence in diverse animal pathogenic bacteria (Rao et al., 2004; Lamarche et al., 2005, 2008). Altogether, these studies suggest that both systems might be regulators of bacterial pathogenicity, which could also be conserved in plant pathogens.

Finally, the rtcA and its regulator rtcR are down-regulated in planta (Table 3). The rtc system is involved in the regulation of the RNA repair system for ribosome homeostasis through the activation of rtcR by different agents and genetic lesions which in turn activates the rtcAB genes (Das and Shuman, 2013). The rtc system was also involved in the functioning of chemotaxis and motility in Escherichia coli (Engl et al., 2016), as mutations in either rtcA or rtcB increased motility. Since rtc acts a repressor of motility, its down-regulation in S. commersonii colonization could influence bacterial motility, a key virulence determinant.

Author contributions

MP performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; RG analyzed data; PZ performed experiments; NC designed the research and wrote the manuscript; AM designed experiments and analyzed data; JS designed the research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; MV designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by projects AGL2013-46898-R, AGL2016-78002-R, and RyC 2014-16158 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. We also acknowledge financial support from the “Severo Ochoa Program for Centres of Excellence in R&D” 2016-2019 (SEV-2015-0533) and the CERCA Program of the Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya) and from COST Action SUSTAIN (FA1208) from the European Union. APM is funded by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese 1000 Talents Program. MP holds an APIF doctoral fellowship from Universitat de Barcelona and received a travel fellowship allowed by Fundació Montcelimar and Universitat de Barcelona to carry out a short stay in JCS's lab. RGS holds a doctoral fellowship; grant 2012/15197-1, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and JCS has a CNPq research fellowship.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. de Pedro for helping in the solid rich medium sample preparation, I. Erill for helping in the transcriptomic data interpretation, S. Genin, and S. Lindow for inspiring discussions, C. Madrid, and C. Balsalobre for advice on transcriptome data interpretation, M. Solé for the potato infection set up and F. Vilaró, M. dalla Rizza, and M.J. Pianzzola for their advice and for providing the S. commersonii genotypes used in this study. We thank the Shanghai PSC Genomics facility for RNA sequencing.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00370/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ailloud F., Lowe T. M., Robene I., Cruveiller S., Allen C., Prior P. (2016). In planta comparative transcriptomics of host-adapted strains of Ralstonia solanacearum. PeerJ. 4:e1549. 10.7717/peerj.1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T., Huber W. (2015). HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocsanczy A. M., Achenbach U. C., Mangravita-Novo A., Chow M., Norman D. J. (2014). Proteomic comparison of Ralstonia solanacearum strains reveals temperature dependent virulence factors. BMC Genomics 15:280. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher C. A., Van Gijsegem F., Barberis P. A., Arlat M., Zischek C. (1987). Pseudomonas solanacearum genes controlling both pathogenicity on tomato and hypersensitivity on tobacco are clustered. J. Bacteriol. 169, 5626–5632. 10.1128/jb.169.12.5626-5632.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G., Allen C. (2004). Ralstonia solanacearum genes induced during growth in tomato: an inside view of bacterial wilt. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1641–1660. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner D. (2016). Behind the lines-actions of bacterial type III effector proteins in plant cells. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 894–937. 10.1093/femsre/fuw026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso C., Supuran C. T. (2015). Bacterial, fungal and protozoan carbonic anhydrases as drug targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 19, 1689–1704. 10.1517/14728222.2015.1067685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capy P., Gasperi G., Biémont C., Bazin C. (2000). Stress and transposable elements: co-evolution or useful parasites? Heredity (Edinb). 85, 101–106. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A., Pirofski L. (2001). Host-pathogen interactions: the attributes of virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 337–344. 10.1086/322044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado C., Llagostera M., Barbe J. (1991). Expression of nrdA and nrdB genes of Escherichia coli is decreased under anaerobiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 67, 153–157. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04432.x-i1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn-Clifford J., Allen C. (2010). A cbb(3)-type cytochrome C oxidase contributes to Ralstonia solanacearum R3bv2 growth in microaerobic environments and to bacterial wilt disease development in tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 1042–1052. 10.1094/MPMI-23-8-1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll N. S., Valls M. (2013). Current knowledge on the Ralstonia solanacearum type III secretion system. Microb. Biotechnol. 6, 614–620. 10.1111/1751-7915.12056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Moreira B., Vinuesa P. (2013). GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7696–7701. 10.1128/aem.02411-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz A. P., Ferreira V., Pianzzola M. J., Siri M. I., Coll N. S., Valls M. (2014). A novel, sensitive method to evaluate potato germplasm for bacterial wilt resistance using a luminescent Ralstonia solanacearum reporter strain. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 277–285. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0303-FI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac S., Occhialini A., Barberis P., Boucher C., Genin S. (2004). Inventory and functional analysis of the large Hrp regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum: identification of novel effector proteins translocated to plant host cells through the type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 115–128. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsing B. L., Allen C. (2014). Nitrate assimilation contributes to Ralstonia solanacearum root attachment, stem colonization, and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 196, 949–960. 10.1128/JB.01378-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsing B. L., Truchon A. N., Gonzalez-Orta E. T., Milling A. S., Allen C. (2015). Ralstonia solanacearum uses inorganic nitrogen metabolism for virulence, ATP production, and detoxification in the oxygen-limited host xylem environment. MBio 6:e02471. 10.1128/mBio.02471-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das U., Shuman S. (2013). 2'-Phosphate cyclase activity of RtcA: a potential rationale for the operon organization of RtcA with an RNA repair ligase RtcB in Escherichia coli and other bacterial taxa. RNA 19, 1355–1362. 10.1261/rna.039917.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaspre F., Nieto Penalver C. G., Saurel O., Kiefer P., Gras E., Milon A., et al. (2007). The Ralstonia solanacearum pathogenicity regulator HrpB induces 3-hydroxy-oxindole synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15870–15875. 10.1073/pnas.0700782104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engl C., Schaefer J., Kotta-Loizou I., Buck M. (2016). Cellular and molecular phenotypes depending upon the RNA repair system RtcAB of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 9933–9941. 10.1093/nar/gkw628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavier A. B., Ganova-Raeva L. M., Schell M. A., Denny T. P. (1997). Hierarchical autoinduction in Ralstonia solanacearum: control of Acyl-homoserine lactone production by a novel autoregulatory system responsive to 3-hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester. J. Bacteriol. 179, 7089–7097. 10.1128/jb.179.22.7089-7097.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Cruz Z., Allen C. (2009). Ralstonia solanacearum encounters an oxidative environment during tomato infection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 773–782. 10.1094/MPMI-22-7-0773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga X., Eliasson R., Torrents E., Barbé J., Gibert I., Reichard P. (1996). nrdD and nrdG genes are essential for strict anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 229, 189–192. 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarischi-Sousa R., Puigvert M., Coll N. S., Siri M. I., Pianzzola M. J., Valls M., et al. (2016). Complete genome sequence of the potato pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum UY031. Stand. Genomic Sci. 11, 7. 10.1186/s40793-016-0131-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., Toyofuku M., Miyano T., Nomura N. (2014). cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidases, aerobic respiratory enzymes, impact the anaerobic life of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 196, 3881–3889. 10.1128/jb.01978-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward A. C. (1991). Biology and epidemiology of bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 29, 65–87. 10.1146/annurev.py.29.090191.000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Carney B. F., Denny T. P., Weissinger A. K., Schell M. A. (1995). A complex network regulates expression of eps and other virulence genes of Pseudomonas solanacearum. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1259–1267. 10.1128/jb.177.5.1259-1267.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. M., Babujee L., Meng F., Milling A., Allen C. (2012). The in planta transcriptome of Ralstonia solanacearum: conserved physiological and virulence strategies during bacterial wilt of tomato. MBio 3:e00114–12. 10.1128/mBio.00114-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger C. H., III., Lindow S. E., Miller W., Clark E., Firestone M. K. (1999). Mapping of sugar and amino acid availability in soil around roots with bacterial sensors of sucrose and tryptophan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2685–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda A., Yasukohchi M., Ohnishi K., Kiba A., Okuno T., Hikichi Y. (2003). Ectopic expression of Ralstonia solanacearum effector protein PopA early in invasion results in loss of virulence. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 447–455. 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.5.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Liu H., Genin S., Schell M. A., Denny T. P. (2002). Ralstonia solanacearum requires type 4 pili to adhere to multiple surfaces and for natural transformation and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 427–437. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen N. T., Tamaki S., Kobayashi D., Gerhold D., Stayton M., Shen H., et al. (1990). Bacteria expressing avirulence Gene D produce a specific elicitor of the soybean hypersensitive reaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 3, 112–121. 10.1094/MPMI-3-112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Lee H., Moon J. S., Hong Y. J., Kim M. S., Cho H. M. (2005). Bacterial wilt resistance in the progenies of the fusion hybrids between haploid of potato and Solanum commersonii. Am. J. Potato Res. 82, 129–137. 10.1007/BF02853650 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kredich N. M. (1992). The molecular basis for positive regulation of cys promoters in Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 2747–2753. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01453.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung V. L., Khare S., Stehlik C., Bacon E. M., Hughes A. J., Hauser A. R. (2012). An rhs gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a virulence protein that activates the inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1275–1280. 10.1073/pnas.1109285109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La M. V., Raoult D., Renesto P. (2008). Regulation of whole bacterial pathogen transcription within infected hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 440–460. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche M. G., Dozois C. M., Daigle F., Caza M., Curtiss R., III., Dubreuil J. D., et al. (2005). Inactivation of the pst system reduces the virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 strain. Infect. Immun. 73, 4138–4145. 10.1128/iai.73.7.4138-4145.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche M. G., Wanner B. L., Crepin S., Harel J. (2008). The phosphate regulon and bacterial virulence: a regulatory network connecting phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32 461–473. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimbach A. (2016). Bac-Genomics-Scripts: Bovine E. coli Mastitis Comparative Genomics Edition [Data set]. Zenodo; 10.5281/zenodo.215824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Xu C., Jin Y., Sun Z., Liu C., Shi J., et al. (2013). SuhB is a regulator of multiple virulence genes and essential for pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 4, e00419–e00413. 10.1128/mbio.00419-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R. J., Capage M., Hill C. W. (1984). A repetitive DNA sequence, rhs, responsible for duplications within the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. J. Mol. Biol. 177, 1–18. 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Kang Y., Genin S., Schell M. A., Denny T. P. (2001). Twitching motility of Ralstonia solanacearum requires a type IV pilus system. Microbiology (Reading,. Engl). 147, 3215–3229. 10.1099/00221287-147-12-3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonjon F., Turner M., Henry C., Rengel D., Lohou D., van de Kerkhove Q., et al. (2016). Comparative secretome analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum Type 3 secretion-associated mutants reveals a fine control of effector delivery, essential for bacterial pathogenicity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 15, 598–613. 10.1074/mcp.M115.051078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren B. R., Connolly M. P., Choudhary P., Brookins-Little T. S., Chatterjee S., Raina R., et al. (2015). Defining the metabolic functions and roles in virulence of the rpoN1 and rpoN2 Genes in Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000. PLoS ONE 10:e0144852. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F. (2013). The virulence factors of the bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 4:168. 10.4172/2157-7471.1000168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F., Babujee L., Jacobs J. M., Allen C. (2015). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals cool virulence factors of Ralstonia solanacearum Race 3 Biovar 2. PLoS ONE 10:e0139090. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewski S. (2002). Glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase–the multi-facets enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1597, 173–192. 10.1016/S0167-4838(02)00318-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro F., Genin S., van Dijk I., Valls M. (2012). A luminescent reporter evidences active expression of Ralstonia solanacearum type III secretion system genes throughout plant infection. Microbiology (Reading,. Engl). 158, 2107–2116. 10.1099/mic.0.058610-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y., Inoue K., Ikeda K., Nakayashiki H., Higashimoto C., Ohnishi K., et al. (2016). The vascular plant-pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum produces biofilms required for its virulence on the surfaces of tomato cells adjacent to intercellular spaces. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 890–902. 10.1111/mpp.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucyn T. S., Yourstone S., Lind A. L., Biswas S., Nishimura M. T., Baltrus D. A., et al. (2014). Variable suites of non-effector genes are co-regulated in the type III secretion virulence regulon across the Pseudomonas syringae phylogeny. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003807. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occhialini A., Cunnac S., Reymond N., Genin S., Boucher C. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in Ralstonia solanacearum reveals that the hrpB gene acts as a regulatory switch controlling multiple virulence pathways. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18, 938–949. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters N., Guidot A., Vailleau F., Valls M. (2013). Ralstonia solanacearum, a widespread bacterial plant pathogen in the post-genomic era. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 651–662. 10.1111/mpp.12038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg G. F. (1985). Life in a black hole: the microenvironment of the vascular pathogen. Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 85, 1–20. 10.1016/S0007-1528(85)80043-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peyraud R., Cottret L., Marmiesse L., Gouzy J., Genin S. (2016). A resource allocation trade-off between virulence and proliferation drives metabolic versatility in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005939. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plener L., Boistard P., Gonzalez A., Boucher C., Genin S. (2012). Metabolic adaptation of Ralstonia solanacearum during plant infection: a methionine biosynthesis case study. PLoS ONE 7:e36877. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa C., Coll N. S., Valls M., Sessa G. (2016a). Yeast as a heterologous model system to uncover type III effector function. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005360. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]