Abstract

Introduction:

Legislation making seatbelt use mandatory is considered to have reduced fatal and serious injuries by 25%, with UK government estimates predicting more than 50,000 lives saved since its introduction. However, whilst the widespread use of seatbelts has reduced the incidence of major traumatic injury and death from road-traffic collisions (RTCs), their use has also heralded a range of different injuries. The first ever seatbelt related injury was described in 1956, and since then clear patterns of seatbelt-related injuries have been recognised.

Methodology and Findings:

This review of the published literature demonstrates that the combination of airbags and three-point seatbelts renders no part of the body free from injury. Serious injuries can, and do, occur even when passengers are properly restrained and attending clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for overt or covert intra-abdominal injuries when patients involved in RTCs attend the Emergency Department. Bruising to the trunk and abdomen in a seatbelt distribution is an obvious sign that suggests an increased risk of abdominal and thoracic injury, but bruising may not be apparent and its absence should not be falsely reassuring. A high index of suspicion should be retained for other subtler signs of injury. Children and pregnant women represent high-risk groups who are particularly vulnerable to injuries.

Conclusion:

In this review we highlight the common patterns of seatbelt-related injuries. A greater awareness of the type of injuries caused by seatbelt use will help clinicians to identify and treat overt and covert injuries earlier, and help reduce the rates of morbidity and mortality following RTCs.

Key Words: Car-restraint systems, chance fracture, road traffic accident, seat belt syndrome, seat belts, trauma

INTRODUCTION

In 1983, legislation was passed making it compulsory for all front-seat passengers to wear seat belts in the UK. This was then extended to include rear-seat passengers 8 years later. Despite this, a survey in 2007 by The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents showed that there is still significant morbidity and mortality from passengers' traveling unrestrained. They estimated 370 deaths and a further 27,774 people seriously injured every year.[1]

Since the introduction of seat belt laws, there has been an approximate 25% reduction in fatal and serious injuries from randomized controlled trials (RTCs). The UK government estimates that more than 50,000 lives have been saved by seat belts, and of the fatalities that have been recorded, one-third of these were not wearing seat belts.[1,2] Similar reductions in mortality have been recorded in other countries. In spite of the evidence supporting seat belt use, compliance among the general population is not universal and is estimated to be 93% in the UK.[3,4] Although the benefits of seatbelts are clear, it must not be forgotten by health professionals that seat belts are associated with their own patterns-of-injury that should be deliberately and specifically looked for when assessing all patients involved in RTCs. The first reported seat belt-related injury was a small bowel injury in a passenger wearing a lap belt.[5] Since then, more complex patterns of injury associated with lap belts, three-point restraint seat belts, and airbags have been reported,[6] with no area of the body immune from injury. An increase in hollow viscus injuries, thoracic injuries, abdominal wall hernias, and neck injuries have all been recorded in individuals wearing seat belts involved in RTCs.[7]

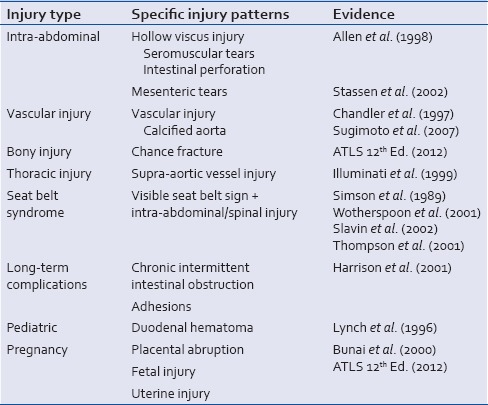

A recent report by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death in 2007 showed that 60% of major trauma patients received a standard of care that was “less than good practice.” Furthermore, on the basis of an estimate by the National Audit Office, about 3000 deaths in hospitals result from major trauma each year. Improvements in care might save 450–600 additional lives each year across England.[8] This short review aims to increase awareness of the patterns of injury [Table 1] that can often be found in seat belt wearers after an RTC, and encourage clinicians to maintain a high degree of suspicion to ensure early diagnosis and effective management when dealing with trauma patients.

Table 1.

Pattern of injury seen in seat belt-related trauma patients

THORACIC INJURIES

There are also reports describing less common injuries to the supra-aortic vessels (carotid and subclavian) in association with first and second rib fractures from the shoulder harness of seat belts.[9]

SEAT BELT SIGN AND SEAT BELT SYNDROME

Seat belt sign is the characteristic pattern of contusion across the chest wall and abdomen seen in a restrained passenger involved in an RTC. It is indicative of an internal injury in as many as 30% of cases seen in the emergency department.[6]

Seat belt syndrome describes the presence of the seat belt sign plus an intra-abdominal or spinal injury. As such, clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for other injuries in all patients presenting with visible seat belt bruising. Furthermore, since the advent of the new three-point restraint systems (including airbags), seat belt syndrome is being increasingly reported.[7,10,11,12]

INTRA-ABDOMINAL INJURIES

Intestinal injuries are more common in patients wearing a seat belt than those who travel unrestrained[7] and a visible seat belt contusion is associated with a threefold higher incidence of intestinal perforation.[13] Allen et al. revealed a 10% incidence of hollow viscus injury including intestinal perforations, seromuscular tears and/or mesenteric tears in association with seat belt marks to the trunk.[14] This association was more apparent when there was coexisting injury to a solid organ; specifically, there was a 50% increased risk of injury to a hollow viscus when the pancreas was involved. These injuries are the result of the dissipation of kinetic energy through the body as the seat belt restricts the passenger, preventing ejection from the seat. As such the less mobile areas of the bowel (proximal jejunum) are more vulnerable to injury. Furthermore, there have been reports of vascular injuries to the aorta when calcified, caused by direct pressure from the seat belt.[15,16]

The long-term complications of seat belt injuries have also been demonstrated many years later with one case report of chronic intermittent intestinal obstruction, some 7 years after the initial injury, resulting from adhesions.[17] It has been demonstrated in the pediatric population that direct injury to the bowel from seat belts, such as bruising/compression sufficient to cause ischemia, did, in turn, lead to strictures.[18] There have also been case reports of a duodenal hematoma in a child presenting 4 days following injury with signs of intestinal obstruction. This injury results from the shearing forces which lead to bleeding from the small vessels. It is more common in the pediatric population due to the poorly developed abdominal wall musculature, the wide costal angle in children, and closely related vascular pedicles.[19]

BONY INJURIES

Another common injury discovered in this group of patients is the chance fracture. This is a transverse vertebral fracture, caused by hyperflexion about an axis anterior to the vertebral column. Chance fractures were first described in 1948 and are found most commonly in passengers wearing a “lap-belt.” Chance fractures are seen in association with intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal visceral trauma in 50%–65% of the cases.

PREGNANCY

The widespread introduction of seat belts for front seat passengers has undoubtedly reduced injury and death during impact. Contrary to popular belief, pregnant women wearing seat belts in RTCs are not at increased risk of adverse fetal outcomes if the seat belt is properly positioned (with the lap belt placed snugly under the abdomen and shoulder restraints positioned diagonally across the chest).[20] This reduces the likelihood of direct and indirect fetal injury because of the greater surface area over which the deceleration force is dissipated and also preventing forward flexion of the mother over the gravid uterus. However, there have been reports of abruptio placentae, fetal injuries, and uterine injuries when seat belts are not worn correctly adjusted for the gravid uterus.[21,22] The type of restraint system employed does affect the frequency of uterine rupture and fetal death.

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

The most important recommendation in diagnosing any of the injuries that occur with seat belts, especially those with visible bruising, is to have a high index of clinical suspicion. This should be accompanied by repeated observation and monitoring and the judicious use of available imaging modalities.

Modern day emergency medicine allows for the use of a number of diagnostic tools to rule out both overt and covert injuries. Focused abdominal sonography for trauma has emerged as a quick and easily available tool in diagnosing the presence of intraperitoneal fluid or blood. The reported sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography is in the range of 41% and 99.7% respectively, but a negative predictive rate of 95% must be taken into account.[12,23]

Assessment of fetal cardiotocography should be performed in all pregnancies where a deceleration collision in the presence of a maternal seat belt restraint makes fetal injury a possibility.

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has been performed with success in patients with blunt abdominal trauma who are unstable and need urgent intervention. In one study on road traffic accidents, DPL was shown to have 100% sensitivity in comparison to computed tomography (CT) abdomen which had a sensitivity of only 85%.[14] However, CT scanning confers other advantages, including the ability to detect extraluminal air or extravasation of oral contrast into the peritoneal cavity both of which are critical in deciding on the need for early operative intervention.[10] CT scanning also has a high sensitivity for detecting blunt pancreatic trauma. Imaging of the entire spine, either plain or CT should be considered to rule out a chance fracture.

CONCLUSION

There is a general consensus that the introduction of seat belts has saved many lives and led to a significant reduction in morbidity from RTCs. However, clinicians treating trauma must bear in mind that injuries are still prevalent in restrained passengers and must be vigilant towards the patterns of injury that result from the use of seat belts. There should be a particularly high index of suspicion when there is seatbelt bruising on the trunk. Research has shown many seat belt injuries become apparent several days after the initial accident, in patients initially presenting with the benign abdominal examination. A period of observation or strict instructions as to potential complications should always be given to patients before discharge, especially those with visible bruising. In addition, children and pregnant women represent high-risk groups who are particularly vulnerable to injuries resulting from inappropriate seat belt application and the opportunity for education on seat belt application should not be missed in all healthcare contacts. Measures to introduce greater flexibility for customizing restraint systems to accommodate high-risk groups are likely to reduce the risk of injury. When injuries inevitably do occur, emergency physicians and trauma surgeons must endeavor to exclude or promptly recognize symptoms and signs of blunt trauma and manage injuries according to advanced trauma life support protocols. Finally, seat belts save lives, and their use cannot be over-emphasized under any circumstances. Furthermore, we strongly recommend Emergency Department policies to be modified to consider CT scanning of all patients with seat belt bruising given the strong correlation with abdominal pathology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 14]. Available from: http://www.rospa.com/roadsafety/

- 2.Freeman CP. Isolated pancreatic damage following seat belt injury. Injury. 1985;16:478–80. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(85)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Traffic Safety Facts. Research Notes. DOT HS 8111 036; November, 2006. 2008. Sep, [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/810818 .

- 4.Wallis LA, Greaves I. Injuries associated with airbag deployment. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:490–3. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.6.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulowski J, Rost WB. Intra-abdominal injury from safety belt in auto accident; report of a case. AMA Arch Surg. 1956;73:970–1. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280060070015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes CW, Conway WF, Walsh JW, Coppage L, Gervin AS. Seat belt injuries: Radiologic findings and clinical correlation. Radiographics. 1991;11:23–36. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.1.1996397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simson JN. Seat belts – Six years on. J R Soc Med. 1989;82:125–6. doi: 10.1177/014107688908200301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Audit Office Report. [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/national-audit-office-annual-report-2010/

- 9.Illuminati G, Calio FG, Bertagni A, Mangialardi N, Martinelli V. Seat-belt-related injuries to the supra-aortic arteries. Scand Cardiovasc J. 1999;33:111–5. doi: 10.1080/14017439950141920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wotherspoon S, Chu K, Brown AF. Abdominal injury and the seat-belt sign. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2001;13:61–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2001.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slavin RE, Borzotta AP. The seromuscular tear and other intestinal lesions in the seatbelt syndrome: A clinical and pathologic study of 29 cases. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2002;23:214–22. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson NS, Date R, Charlwood AP, Adair IV, Clements WD. Seat-belt syndrome revisited. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55:573–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stassen NA, Lukan JK, Carrillo EH, Spain DA, Richardson JD. Abdominal seat belt marks in the era of focused abdominal sonography for trauma. Arch Surg. 2002;137:718–22. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen GS, Moore FA, Cox CS, Jr, Wilson JT, Cohn JM, Duke JH. Hollow visceral injury and blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1998;45:69–75. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199807000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler CF, Lane JS, Waxman KS. Seatbelt sign following blunt trauma is associated with increased incidence of abdominal injury. Am Surg. 1997;63:885–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto T, Omura A, Kitade T, Takahashi H, Koyama T, Kurisu S. An abdominal aortic rupture due to seatbelt blunt injury: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:86–8. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison JR, Blackstone MO, Vargish T, Gasparaitis A. Chronic intermittent intestinal obstruction from a seat belt injury. South Med J. 2001;94:499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch JM, Albanese CT, Meza MP, Wiener ES. Intestinal stricture following seat belt injury in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1354–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deambrosis K, Subramanya MS, Memon B, Memon MA. Delayed duodenal hematoma and pancreatitis from a seatbelt injury. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:128–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyde LK, Cook LJ, Olson LM, Weiss HB, Dean JM. Effect of motor vehicle crashes on adverse fetal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunai Y, Nagai A, Nakamura I, Ohya I. Fetal death from abruptio placentae associated with incorrect use of a seatbelt. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:207–9. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ATLS Manual for Doctors. 9th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natarajan B, Gupta PK, Cemaj S, Sorensen M, Hatzoudis GI, Forse RA. FAST scan: Is it worth doing in hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients? Surgery. 2010;148:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]