ABSTRACT

A self-organizing organoid model provides a new approach to study the mechanism of human liver organogenesis. Previous animal models documented that simultaneous paracrine signaling and cell-to-cell surface contact regulate hepatocyte differentiation. To dissect the relative contributions of the paracrine effects, we first established a liver organoid using human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) as previously reported. Time-lapse imaging showed that hepatic-specified endoderm iPSCs (HE-iPSCs) self-assembled into three-dimensional organoids, resulting in hepatic gene induction. Progressive differentiation was demonstrated by hepatic protein production after in vivo organoid transplantation. To assess the paracrine contributions, we employed a Transwell system in which HE-iPSCs were separately co-cultured with MSCs and/or HUVECs. Although the three-dimensional structure did not form, their soluble factors induced a hepatocyte-like phenotype in HE-iPSCs, resulting in the expression of bile salt export pump. In conclusion, the mesoderm-derived paracrine signals promote hepatocyte maturation in liver organoids, but organoid self-organization requires cell-to-cell surface contact. Our in vitro model demonstrates a novel approach to identify developmental paracrine signals regulating the differentiation of human hepatocytes.

KEY WORDS: Hepatocyte differentiation, Liver development, Regeneration, Tissue engineering, ABCB11

Summary: Paracrine signals from MSCs or HUVECs are able to promote hepatocyte differentiation independently, but both must co-exist to allow for the cell-cell contact and organization into a 3D liver organoid.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to produce differentiated functional hepatocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) presents a major opportunity to directly study mechanisms of human liver disease, to perform high-throughput drug screening for new therapies, and to facilitate hepatocyte transplantation (Baxter et al., 2010; Colman and Dreesen, 2009; Forbes et al., 2015; Haridass et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2012). Functional hepatocytes derived from iPSCs are in a relatively immature state, with a gene expression pattern similar to that of the embryonic liver (Si-Tayeb et al., 2010). Recent embryology studies have discovered the crucial roles of the surrounding mesenchymal and endothelial cells in the formation of the liver primordium from the endoderm (Matsumoto et al., 2001). These mesodermal cells govern the specification of liver progenitors and control their fate by creating an embryonic niche that promotes liver development. Recapitulating this embryonic niche presents a novel approach to guide hepatic differentiation and liver organoid morphogenesis from iPSCs (Takebe et al., 2013).

iPSCs cultured in the presence of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; from human bone marrow) form a three-dimensional (3D) liver organoid that enables further hepatic differentiation (Takebe et al., 2013). Direct cell-cell contact of MSCs with the other cells appears to be required to induce liver organoid morphogenesis (Takebe et al., 2015). However, the contact-dependent or paracrine factors regulating hepatic differentiation remain unknown. We hypothesized that soluble factors, independent of cell-cell contact, regulate hepatic differentiation of iPSCs. To test this hypothesis, we first documented the transcriptional profile of the organoid and individual cell types, and molecularly defined the different stages of organoid development. Then, we created a two-chamber culture system that prevents iPSC contact with HUVECs and MSCs while maintaining exposure to their soluble factors. We found that organoid morphogenesis requires direct cell-cell contact. Furthermore, we found that iPSCs cultured in the presence of, but without contact with, HUVECs or MSCs manifest the epithelial phenotype of hepatocyte differentiation, including high levels of albumin secretion, canalicular proteins, tight junctions and other functional markers.

RESULTS

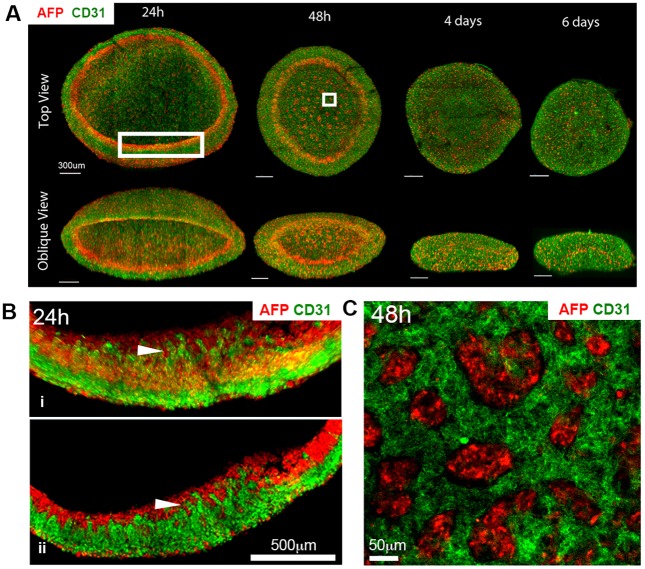

iPSCs directly interact with HUVECs and MSCs during liver organoid formation

We first investigated morphogenesis of the liver organoid and focused on the behavior of HUVECs. To examine positional relationships of hepatic-specified endoderm iPSCs (HE-iPSCs) to HUVECs and the morphological dynamics of organoid formation, we precisely mapped the spatial distribution of HE-iPSCs and HUVECs by whole-mount staining with antibodies against alpha fetoprotein (AFP; hepatoblast marker) and CD31 (also known as PECAM1; HUVEC marker) followed by fluorescence confocal microscopy. We examined cellular distribution at 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, day 4 and day 6 after starting co-culture (Fig. 1A). At 6 h of co-culture, AFP+ and CD31+ cells began to self-cluster while forming a disc-like structure (Fig. S1). At 24 h, confocal image analysis revealed spatial proximity of AFP+ cells to HUVECs at the inner surface of the organoid disc margin, where HUVEC tubular structures extended into an AFP+ band-like layer (Fig. 1B). At 48 h, the AFP+ cells formed small clusters in a HUVEC web-like structure in addition to a circular band-like layer at the periphery of the organoid (Fig. 1C). At days 4 and 6, as the organoid condensed in size, the HUVEC network extended. These observations suggested that the HE-iPSCs and HUVECs maintain spatial proximity during dynamic liver organoid morphogenesis, raising the possibility that they might exert paracrine effects.

Fig. 1.

Liver organoid morphogenesis. (A) Three-dimensional reconstruction of liver organoid shows the distribution of AFP+ cells (red) and CD31+ HUVECs (green) in a time series. (B) High-magnification images of the larger boxed region in A. Arrowhead points to the interface between differentiating HE-iPSCs (red) and HUVECs (green) after 24 h of culture. (i) 3D reconstruction; (ii) single z-plane. (C) High magnification of the smaller boxed region in A. Clusters of AFP+ cells (red) are surrounded by HUVECs (green) at 48 h of culture.

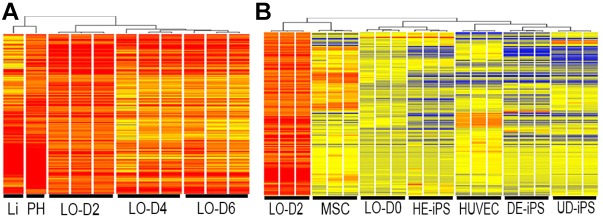

To quantify the extent of hepatic differentiation induced by cell-cell interaction during liver organoid formation, we measured changes in the organoid transcriptome at time points corresponding to the self-organization and condensation of the organoid (days 2, 4, 6; n=3 each). We determined gene expression profiles by RNA-seq, as compared with additional samples obtained from human liver tissue and primary cultured human hepatocytes. First, to select liver-related genes, we identified 3146 that were enriched in expression in the primary hepatocytes (≥2-fold). Next, an analysis of the most significantly altered group of genes in the liver organoids (expression levels ≥2-fold) showed enrichment of 442 genes in day 2 liver organoids (LO-D2). Applying hierarchical clustering and phylogenetic tree analysis, these LO-D2 genes clustered into one subgroup and day 4 (LO-D4) and day 6 (LO-D6) into another, with distinct patterns of differentially expressed genes between the two subgroups (Fig. 2A). Gene expression profiles of LO-D2 were similar to that of primary cultured human hepatocytes. Notably, although a substantial number of gene transcripts maintained a similar level of expression in LO-D4 and LO-D6, the lower expression of some genes suggests that prolonged culture of liver organoids in the current culture conditions might not be suitable for the maintenance of hepatocyte differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Liver organoid differentiation in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cluster analysis of gene expression profiles of liver organoids (n=3) at days 2, 4 and 6 of culture (LO-D2, LO-D4 and LO-D6, respectively). The expression profile of LO-D2 shows closest similarity with that of primary hepatocytes (PH) and liver tissue (Li). (B) Heatmap showing 442 genes (Tables S1 and S2) in the profile of LO-D2 that are shared with the PH and Li profiles (in A) and their expression in MSCs cultured alone, in HUVECs alone, in cell mixture at the time of plating of iPSCs+MSCs+HUVECs (liver organoid day 0, LO-D0), in hepatic-specified endoderm iPSCs (HE-iPS), in definitive endoderm iPSCs (DE-iPS) and in undifferentiated iPSCs (UD-iPS).

To further examine whether these genes were induced de novo by cell-cell interaction during organoid formation, we compared the LO-D2 gene expression profiles with that of individual cells cultured alone (Fig. 2B). We found that most of the genes are not expressed before co-culture, indicating that co-culturing different cell types induced new genes that are important for hepatocyte differentiation. Collectively, these results indicate that spatial proximity of HE-iPSCs to HUVECs (and MSCs) at complex interfaces correlates with the peak expression of genes important for hepatic differentiation during the first 48 h of organoid morphogenesis, suggesting a crucial role for cell-cell interaction during liver organoid development.

To determine whether liver organoids are capable of functioning as mature liver tissue, organoids at day 2 culture were implanted under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice. Three weeks after implantation, serum levels of human albumin (increasing up to 284 ng/ml at 8 weeks) and alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) (increasing up to 206 ng/ml at 8 weeks) were detected, further suggesting hepatic maturation of the liver organoid in vivo (Fig. S2). The albumin concentration was lower than that found in human serum, which contains 40 mg/ml, but the concentration of A1AT was closer to that of human serum (2 μg/ml). Neither human albumin nor A1AT was detected in the serum of mice that were implanted with human MSCs under the kidney capsule.

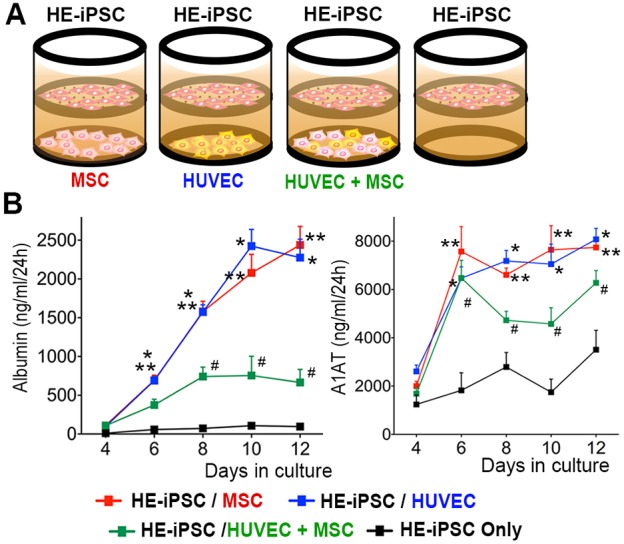

Direct surface contact of stem cells is required for the 3D formation of liver organoids

Based on the finding that spatial proximity of HE-iPSCs with HUVECs correlates with hepatic differentiation of the organoid, we examined whether direct surface contact is required for liver organoid morphogenesis by applying a two-chamber culture system for multicellular co-culture. In this two-chamber culture system, cell surface contact was prohibited by a permeable membrane interposed between HE-iPSCs and HUVECs and/or MSCs. In the two-story well, HE-iPSCs were cultured on a Matrigel-coated micropore membrane in the upper chamber, and HUVECs and/or MSCs were cultured in the lower chamber in the same medium used for the liver organoid culture (Fig. 3A). When cultured with HUVECs and/or MSCs, the HE-iPSCs in the upper chamber did not undergo induced 3D morphogenesis; instead, they formed a monolayer on the membrane. This indicates that surface contact of HE-iPSCs with non-parenchymal cells (HUVECs and MSCs) is required for organoid morphogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs induced by paracrine signals of MSCs and/or HUVECs. (A) Two-chamber culture system using a Transwell micropore membrane insert to separate the upper and lower chambers. Hepatic-specified endoderm iPSCs (HE-iPSCs) were plated in the upper chamber and HUVECs and/or MSCs were plated in the lower chamber, while maintaining fluid communication. (B) Timecourse monitoring of albumin and A1AT production from HE-iPSCs in the culture supernatant, as quantified by ELISA (n=8). Culture conditions include HE-iPSCs plated in the upper chamber and the other cell types in the lower chamber. *P<0.01, HE-iPSCs/HUVECs versus HE-iPSCs only; **P<0.01, HE-iPSCs/MSCs versus HE-iPSCs only; #P<0.05, HE-iPSCs/MSCs+HUVECs versus HE-iPSCs only.

To quantify hepatic differentiation of the HE-iPSC monolayer, we serially monitored the albumin concentration in the culture supernatant by ELISA in various two-chamber co-culture combinations (Fig. 3B; n=8 at each time point and co-culture condition). At day 12 of culture, HE-iPSCs/MSCs produced albumin at a rate of 2.44±0.24 μg/ml per 24 h and HE-iPSCs/HUVECs at a rate of 2.28±0.24 μg/ml per 24 h; this is a 25-fold and 24-fold increase, respectively, in albumin production over that of HE-iPSCs without co-culture (95.8±32.7 ng/ml per 24 h; P<0.001). This indicates that paracrine signals produced by HUVECs or MSCs induce hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs. Contrary to our expectation, when co-cultured with MSCs and HUVECs together in the lower chamber, HE-iPSCs produced albumin at a lower rate than HE-iPSCs/MSCs or HE-iPSCs/HUVECs (741±122, 757±247 and 665±169 ng/ml per 24 h at day 8, 10 and 12; all P<0.001). To confirm the source of albumin, we measured mRNA expression of ALB in MSCs, HUVECs and MSCs+HUVECs, which were co-cultured with HE-iPSCs for 12 days. ALB mRNA was not detected in MSCs, HUVECs or MSCs+HUVECs (Fig. S3). We also quantified A1AT production in the same set of culture supernatants and found a pattern of production similar to that of albumin. Neither albumin nor A1AT was produced by HUVECs or MSCs when cultured by themselves in the same culture medium. In each co-culture condition, viable cell numbers of HE-iPSCs were comparable at day 8 and 12. These results indicate that paracrine signals produced by MSCs or HUVECs induce hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs. In addition, the different albumin and A1AT production rates under differing culture conditions (MSCs alone or HUVECs alone versus MSCs+HUVECs) suggested that the co-culturing interaction of MSCs and HUVECs in the lower chamber altered the differentiation of HE-iPSCs.

Because of the noted difference in albumin and A1AT production in the co-culture of HE-iPSCs with both MSCs and HUVECs in the lower chamber (HE-iPSC/MSC+HUVEC triple culture), we monitored morphological changes in the lower chamber during the mixed culture of MSCs and HUVECs, as compared with MSCs alone or HUVECs alone in the lower chamber (Fig. S4). When cultured together, MSCs and HUVECs formed cell clusters and showed distinct cellular morphology by day 4. Viable cell numbers of co-cultured MSCs and HUVECs in the lower chamber were comparable to those of MSCs alone or HUVECs alone, indicating that co-culture did not compromise cell survival. These results raised the possibility that MSC-HUVEC cell-cell interaction triggers changes in the production of paracrine soluble factors, which might lead to the modified differentiation of HE-iPSCs.

The morphology, gene expression and function of the HE-iPSC monolayer

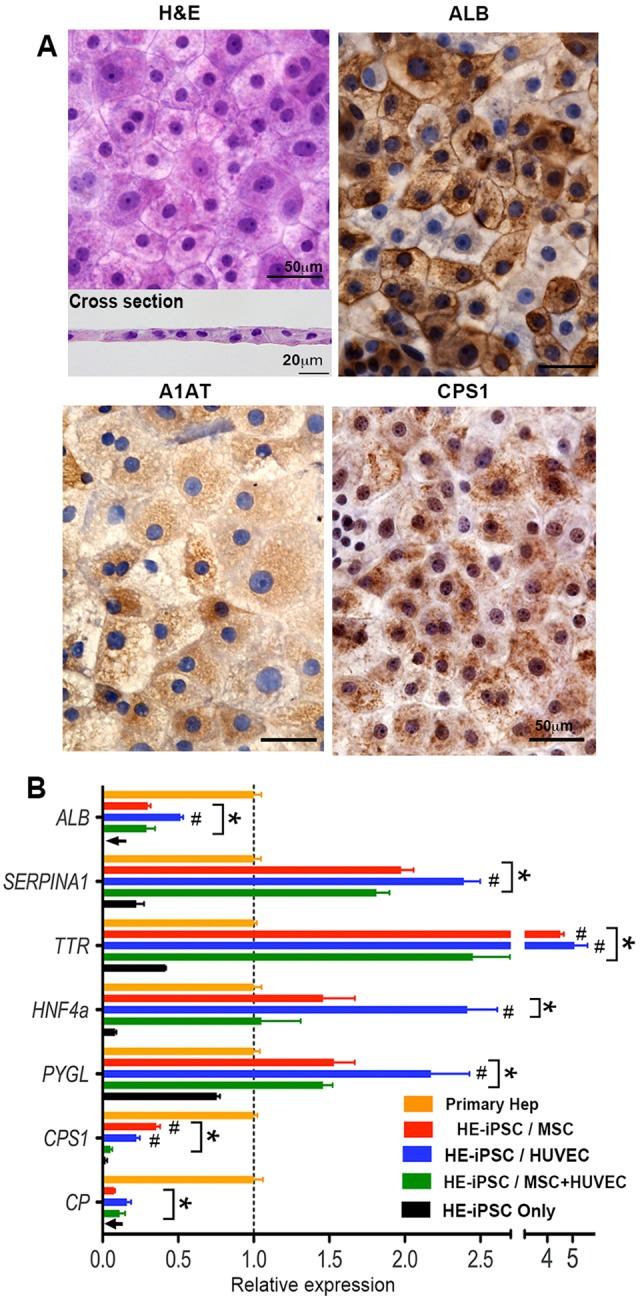

The HE-iPSCs in the upper chamber exhibited a polygonal cellular morphology with occasional diploidic nuclei, resembling mature hepatocytes (Fig. 4A). When cultured without cells in the lower chamber, HE-iPSCs exhibited a morphology similar to that of immature endoderm cells, and unlike epithelial cells (Fig. S5). We characterized the expression pattern of hepatic proteins in HE-iPSCs to examine whether the polygonal monolayer cells differentiated to hepatocytes. Immunohistochemical staining with Hematoxylin counterstaining revealed that the large polygonal cells expressed albumin, A1AT, and the hepatic functional marker carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1 (CPS1) (Fig. 4A). The cholangiocyte markers keratin 7 (CK7) and keratin 19 (CK19) were not expressed.

Fig. 4.

Paracrine signals induce expression of hepatic differentiation markers by HE-iPSCs. (A) Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining of fixed HE-iPSCs, 8 days after two-chamber culture with MSCs in the lower chamber. Large polygonal cells are seen in the monolayer (top), as confirmed in the cross-section (bottom). The remaining panels show immunohistochemical staining of hepatic marker proteins (ALB, A1AT and CPS1) in the hepatocyte-like cells. (B) Hepatic marker gene expression in hepatocyte-like cells at day 8 as measured by quantitative real-time PCR (n=4). After normalization to GAPDH, each gene expression level is shown relative to that in primary hepatocytes (Primary Hep). When compared with primary hepatocytes (*P<0.05), the hepatocyte-like cells in co-cultures expressed more A1AT (SERPINA1), TTR, HNF4a and PYGL, with lower expression for ALB, CPS1 and CP. Comparison among co-culture combinations showed that most genes had higher expression in HE-iPSCs/MSCs and HE-iPSCs/HUVECs when compared with HE-iPSCs/MSCs+HUVECs (#P<0.05). GAPDH expression did not differ among cell types and culture conditions (P>0.05).

To investigate the protein expression pattern of the monolayer cells in the upper chamber induced from HE-iPSCs, we double stained the monolayer with antibodies against albumin and A1AT and found double and single expressing cells (Fig. S6). Double staining for A1AT and CPS1 showed that they had similar expression patterns. These co-expression/single-expression patterns of hepatic proteins resemble that seen in mature hepatocytes in liver tissue.

Next, we measured the expression levels of liver-specific genes in the hepatocyte-like cells at day 8 (Fig. 4B; n=4 for each combination of two-chamber culture). In addition to ALB and A1AT, transthyretin (TTR), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4a), glycogen phosphorylase L (PYGL; an enzyme involved in glycogen metabolism), CPS1 and ceruloplasmin (CP) were quantified. Most of these genes were upregulated after 8 days of two-chamber co-culture as compared with the culture of HE-iPSCs only. When compared with primary hepatocytes in order to measure the degree of hepatic differentiation, the hepatocyte-like cells (with MSCs or HUVECs) expressed more A1AT (SERPINA1), TTR, HNF4a and PYGL, but less ALB, CPS1 and CP. Comparison among co-culture combinations revealed significant variations in each gene expression level. The HE-iPSC/HUVEC and HE-iPSC/MSC cultures showed higher expression levels of most liver-specific genes than that found in the HE-iPSC/MSC+HUVEC culture. Collectively, our results demonstrated that paracrine signals produced by MSCs or HUVECs are sufficient to induce hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs, yet some liver genes were not fully upregulated.

To further examine hepatic function, we measured urea production and glycogen accumulation of the hepatocyte-like cells (Fig. S7). After 8 days of co-culture with HUVECs and/or MSCs in the two-chamber system, the culture supernatants of hepatocyte-like cells were collected after 48 h of culture and the urea concentrations measured. The hepatocyte-like cells released urea into the culture supernatant at similar levels for the co-culture combinations, whereas little urea was produced by HE-iPSCs alone. Glycogen accumulation in the cytoplasm was demonstrated by PAS staining of the hepatocyte-like cells after 8 days of co-culture with HUVECs in the lower chamber. A similar staining pattern was seen in hepatocyte-like cells in the co-culture of MSCs, HUVECs and MSCs+HUVECs.

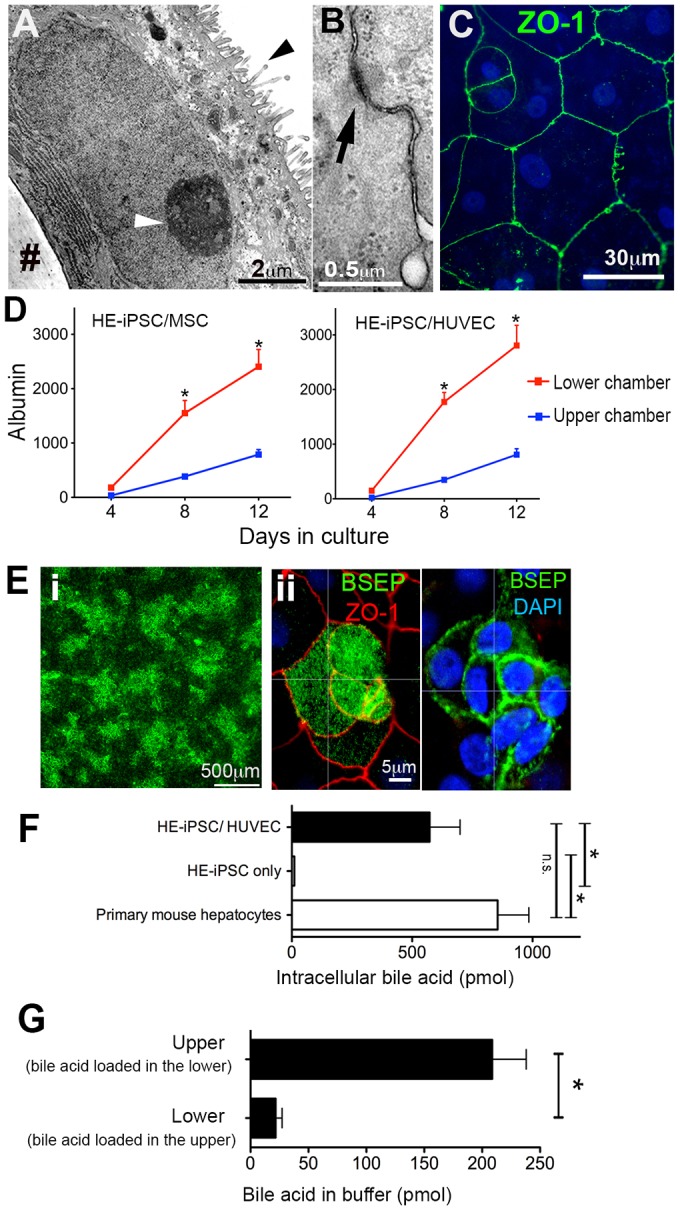

Cellular polarity and bile acid transport of hepatocyte-like cells

To demonstrate other functional features of hepatocyte-like cells, we investigated their polarity by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 5A). The hepatocyte-like cells exhibited microvilli on the surface opposite the monolayer. Each cell was connected to adjacent cells with a desmosome-like structure (Fig. 5B), suggesting the formation of tight junctions. This was confirmed by immunostaining of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (TJP1) (Fig. 5C), with signals on the polygonal border of every hepatocyte-like cell. A z-stack analysis of 3D-reconstructed confocal images revealed focal localization of ZO-1 on the lateral membrane, consistent with the tight junction pattern of typical epithelial tissues. In keeping with polarization, the albumin concentration in the lower chamber was ∼3- to 5-fold higher than that of the upper chamber when HE-iPSCs were co-cultured with MSCs or HUVECs (Fig. 5D; P<0.001).

Fig. 5.

Paracrine signals induce functional polarity in hepatocyte-like cells. (A) Transmission electron micrograph of hepatocyte-like cells showing microvilli on the apical surface (black arrowhead); the white arrowhead points to nucleolus. (B) Each cell is connected to adjacent cells via a desmosome-like structure (arrow). (C) Immunofluorescent staining and confocal imaging of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (green). (D) Albumin gradient between upper and lower chambers at days 4, 8 and 12 of culture (n=6, *P<0.001). (E) (i) Immunofluorescent confocal microscopy imaging at low magnification of hepatocyte-like cells showing BSEP (green). (ii) Higher magnification and z-level analysis showing BSEP (green) and ZO-1 (red). (F) Bile acid uptake by hepatocyte-like cells after 60 min of culture in the two-chamber system in the presence of fluorescent bile acid (CGamF). Intracellular fluorescent bile acid was measured, normalized to cellular protein and compared with controls. The hepatocyte-like cells showed uptake comparable to that of primary mouse hepatocytes (n=5, *P<0.01; n.s., not significant). (G) Bile acid transport by hepatocyte-like cells, with CGamF loaded in the lower chamber and buffer only in the upper chamber. After 60 min of incubation, CGamF concentration in the upper chamber was measured. In control experiments, CGamF was loaded in the upper chamber and measured in the lower chamber after 60 min of incubation.

We also found that the bile salt export pump (BSEP) was expressed in monolayer cells (Fig. 5E). To determine its precise cellular location, we performed immunofluorescent confocal microscopy imaging and determined that BSEP was localized on the apical and lateral membranes. On the apical membrane at the level of ZO-1-positive tight junctions, BSEP was visualized in a fine granular pattern, suggesting that it is expressed on the microvilli, which is seen in the electron microscopy images. We further measured the gene expression of BSEP (ABCB11) in hepatocyte-like cells in co-culture with MSCs and/or HUVECs as compared with HE-iPSCs only (Fig. S8A). The hepatocyte-like cells with MSCs and/or HUVECs expressed more BSEP than cells from HE-iPSCs only. In the HE-iPSC-only culture, rare cells expressed BSEP, as shown by immunofluorescent staining (Fig. S8B).

Further, we tested the ability of the hepatocyte-like cells to transport bile acids from the basolateral membrane (lower chamber) to the apical membrane (upper chamber). First, by quantifying transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), we demonstrated an epithelial barrier function of the hepatocyte-like cells. In all co-culture conditions, the TEER was >400 mΩ cm2; HE-iPSCs cultured alone had no significant TEER. Second, we measured the uptake of the fluorescently labeled bile acid cholylglycylamidofluorescein (CGamF) into the intracellular compartment. After 60 min of CGamF incubation, cells were lysed by NaOH and fluorescence intensities of the lysates were quantified. Hepatocyte-like cells co-cultured with HUVECs showed comparable bile acid uptake to primary adult mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 5F) and significantly higher uptake than that of HE-iPSCs only. To test bile acid transport, we measured the concentration of CGamF in the upper chamber when it was initially loaded in the lower chamber and compared it with the bile acid concentration measured in the lower chamber when loaded in the upper (Fig. 5G). The hepatocyte-like cells co-cultured with HUVECs showed a significantly higher ability to transport bile acid (208.7±29.4 pmol per mg cellular protein) as compared with the reverse (21.7±5.6 pmol per mg cellular protein). The hepatocyte-like cells co-cultured with MSCs and MSCs+HUVECs showed comparable results. These results demonstrated directional (basolateral to apical) bile acid transport in the hepatocyte-like cells.

These results indicate that soluble factors from MSCs and HUVECs are sufficient to induce hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs with a potential canalicular function.

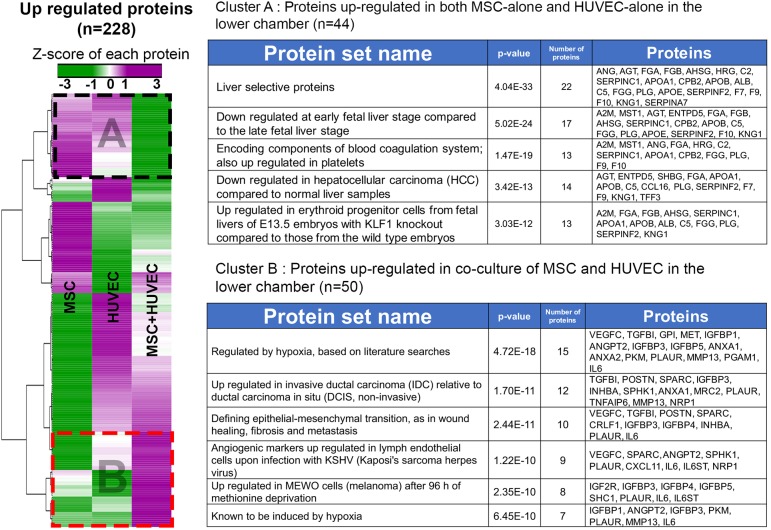

Protein analysis of MSC, HUVEC and MSC+HUVEC co-culture in the two-chamber system

To characterize growth factors and differentiation signals produced by MSCs and HUVECs, we performed a high-throughput proteomic analysis of the culture supernatant. The supernatants from each co-culture combination (HE-iPSC/MSC, HE-iPSC/HUVEC, HE-iPSC/MSC+HUVEC, HE-iPSC only) were collected and subjected to a SOMAscan assay, which captures specific proteins by pre-designed aptamers. The assay quantified 1180 proteins simultaneously in each supernatant; 228 proteins that changed by ≥3-fold compared with the levels seen in HE-iPSCs only were selected for further analysis (Fig. 6). Detailed results of the SOMAscan are listed in Tables S5 and S6. Z-scores of protein expression were used to generate a heatmap for comparison among HE-iPSC/MSC, HE-iPSC/HUVEC, and HE-iPSC/MSC+HUVEC cultures. Cluster analysis of the 228 proteins identified two main groups (Table S7). The first group (cluster A) contained 44 proteins upregulated in the lower chamber when HE-iPSCs were cultured with MSCs or HUVECs, whereas the second group (cluster B) comprises 50 proteins upregulated in co-culture of MSCs+HUVECs in the lower chamber. Results of enrichment analysis of each cluster are provided in Fig. 6 (a full result in Table S8). In cluster A, enrichment analysis revealed that the proteins that are abundantly expressed in both HE-iPSC/MSC and HE-iPSC/HUVEC cultures are typically expressed at the late stage of liver development. Paracrine factors that potentially play roles in hepatic differentiation were identified, including angiotensinogen (ANG), α-2 macroglobulin (A2M) and plasminogen (PLG). In cluster B, we found that the co-culture of MSCs+HUVECs induced a signature in which proteins related to TGFβ and hypoxic response were the most abundantly expressed, indicating that direct cell-cell contact of MSCs and HUVECs induced a distinct secretome signature in the two-chamber culture environment.

Fig. 6.

Protein analysis of the culture supernatants. At day 12 of culture, the supernatants of the lower chambers from HE-iPSCs/MSCs, HE-iPSCs/HUVECs, HE-iPSCs/MSCs+HUVECs, and HE-iPSCs were harvested and subjected to a SOMAscan assay in three biological replicates. The relative fluorescence unit (RFU) of each cell co-culture combination was normalized to the RFU of HE-iPSCs cultured alone. Of 1180 tested proteins, 228 showed an at least 3-fold increase. Cluster analysis using Pearson correlation clustered the proteins in two groups (dashed boxes): (1) cluster A with 44 proteins abundantly produced by MSCs and HUVECs, but downregulated in co-culture of MSCs+HUVECs; and (2) cluster B with 50 proteins abundantly produced by the co-culture of MSCs+HUVECs, but downregulated in MSCs and HUVECs cultured alone. The enrichment analysis by GSEA/MSigDB of each cluster showed that protein sets relate to late liver differentiation in cluster A and to hypoxic responses in cluster B. Each row represents a protein, with expression indicated by the color scale.

DISCUSSION

Our finding that HE-iPSCs differentiate into large polygonal cells with hepatic marker expression and hepatocyte-specific functions provides evidence that paracrine soluble factors secreted by MSCs or HUVECs, without cell-cell surface contact, are sufficient to induce hepatic differentiation. We also demonstrated that co-culture of HE-iPSCs, MSCs and HUVECs induces liver organoid formation and hepatic differentiation simultaneously, with further hepatic maturation after implantation in vivo. In addition to the finding that direct cell-cell surface contact is necessary for 3D liver organoid morphogenesis, our results indicate that paracrine signals from MSCs or HUVECs are able to promote hepatocyte differentiation independently, but both must co-exist to allow for the cell-cell contact and organization into a 3D liver organoid.

It is important to carefully determine the extent of hepatic differentiation during the establishment of methods to induce ʻhepatocytes' from iPSCs since the degree of induction varies widely from fully functional hepatocytes to hepatocyte-like cells with limited hepatic function (Schwartz et al., 2014). To develop an in vitro system that allows for further functional differentiation of hepatocytes from iPSCs, we used human hepatocytes in primary culture to determine the relative extent of hepatic maturation in our liver organoids and induced hepatocyte-like cells. When both cell-cell surface contact and paracrine signals were engaged, the liver organoids showed an expression profile of hepatocyte-enriched genes similar to that of primary hepatocytes, as previously reported (Takebe et al., 2013). When cell-cell surface contact was prevented, the paracrine signals alone could induce hepatic differentiation in HE-iPSCs, as was evident by the changes in the gene expression profiles for albumin and A1AT.

When cultured with MSCs or HUVECs, several hepatic marker genes were highly expressed in the hepatocyte-like cells. Although the mRNA levels were lower than those detected in primary hepatocytes, the degree of albumin production of the hepatocyte-like cells in our two-chamber system was ∼2.5-fold higher than that previously reported in hepatocyte-like cells induced from iPSCs by Si-Tayeb et al. (2010). Their method, which consists of the addition of several growth factors in a stepwise fashion into the culture medium, achieved ∼1.5 μg/ml albumin in the supernatant of the 3 day culture. When cultured for 3 days (from day 7 to day 10), our two-chamber culture of HE-iPSCs/MSCs and iPSCs/HUVECs produced albumin concentrations of 4.3±0.13 and 4.4±0.3 μg/ml, respectively, in the culture supernatant. Additionally, CPS1, a liver-specific enzyme of the urea cycle that is exclusively expressed in mature hepatocytes (Butler et al., 2008), is expressed in our hepatocyte-like cells. We also quantified their function by measuring urea production. Furthermore, we observed morphological features of cellular polarity and tight junctions in the monolayer hepatocyte-like cells. Collectively, the expression pattern of hepatic markers and morphological features provide evidence for additional maturation of hepatocyte-like cells. However, the low expression levels of a few functional genes suggest that the hepatocyte-like cells are less mature than the liver organoids in vivo.

Prior studies support the concept that soluble factors from mesenchymal and endothelial cells induce hepatic differentiation of fetal hepatic progenitors (Tsuruya et al., 2015). Among the paracrine soluble factors known to induce hepatic differentiation is hepatic growth factor (HGF), which is produced by MSCs and HUVECs (Ehashi et al., 2007; Kamiya et al., 2001, 2002). Our proteomic analysis revealed increased expression of HGF in the media from MSCs, HUVECs and MSCs+HUVECs, suggesting that it might serve to induce hepatocyte differentiation of HE-iPSCs. Other growth factors, which are related to late stage liver development, are also found in the secretome of their supernatant, indicating that these paracrine factors from MSCs or HUVECs promote hepatic differentiation in the two-chamber culture. ANG, A2M and PLG, which have been associated with hepatocyte differentiation (or regeneration) in previous studies, are also increased in these cells (Clotman et al., 2005; Gelly et al., 1991; Shanmukhappa et al., 2009; Tiggelman et al., 1997). Future investigations will directly uncover whether these or other molecules produced by the MSCs and/or HUVECs are mechanistically linked to hepatocyte differentiation. Notably, when MSCs and HUVECs are cultured together, they specifically expressed a protein signature of hypoxic responses, including TGFβ-related factors (TGFBI, INHBA). TGFβ stimulation of human hepatocytes has been reported to reduce albumin production (Busso et al., 1990) and to interfere with hepatocyte maturation (Clotman and Lemaigre, 2006; Touboul et al., 2016). Based on this finding, it is possible that hypoxia response proteins may play a role in decreasing albumin production and interfering with hepatic maturation of HE-iPSCs when MSCs and HUVECs are co-cultured in the lower chamber. Further investigation will determine whether these hypoxic response pathways play a regulatory role in cell maturation in co-culture of HE-iPSCs, MSCs and HUVECs, as well as in liver organoids.

Bile acid transporters, especially BSEP, have not been reported as being upregulated in hepatocyte-like cells induced in vitro from iPSCs in prior studies (Schwartz et al., 2014). That co-culture in the two-chamber system promoted the differentiation of cells with BSEP expression, along with their ability to uptake and transport bile acids, adds important biological features to our system. With these functional properties, the system can be used to study the mechanisms of disease due to canalicular dysfunction, as well as for drug screening. However, the full extent of differentiation remains unclear, as we have not yet tested the complete functional repertoire of the hepatocyte canaliculus, which is key for appropriate drug metabolism and bile acid synthesis. If needed, further improvement in the co-culture system, perhaps by the use of a matrix sandwich or changes in oxygenation, could foster further cellular maturation (Deharde et al., 2016; Noel et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2014).

The two-chamber culture system described here provides a simplified approach that might be particularly useful for studies of drug metabolism or to model human diseases at the cellular level. Using iPSCs, Takayama et al. (2014) reported the application of induced hepatocyte-like cells in drug metabolism assays. Our study supports the potential for human hepatocyte-like cells to be used in drug screening and toxicological assays. Examples include the use of the two-chamber culture system to dynamically measure bile acid transport between chambers, thus enabling pharmacokinetic studies of bile acid transporters (Araki et al., 2005; Ghatak et al., 2015; Mita et al., 2006). Based on the comparable functional profiles of HE-iPSCs with MSCs or HUVECs (for example, secretion of albumin and A1AT and bile acid uptake/transport), both experimental conditions might be similarly useful for drug screening. When taking into account the higher expression of HNF4a and PYGL mRNA in the HE-iPSC/HUVEC combination, one might argue that this particular cell co-culture system fosters better maturation and might be preferable.

In summary, by dissecting the mechanism of organoid formation, our study shows that paracrine signals produced by MSCs or HUVECs promote hepatic differentiation in HE-iPSCs without direct surface contact of cells. Our demonstration that the induced hepatocyte-like cells show epithelial polarity and tight junctions provides a foundation for experimental studies, including drug screening and bile acid transport assays. With this methodology, it will be possible to undertake personalized studies using patient-derived iPSCs for therapeutic drug screening for liver diseases and for toxicology experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human liver and primary cultured human hepatocytes

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Human primary hepatocytes were purchased from Gibco Fresh Hepatocytes Service (Thermo). After shipment on ice, plated hepatocytes were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 environment in Williams Medium E (Thermo) supplemented with Primary Hepatocyte Thawing and Plating Supplements (Thermo) for 48 h before being subjected to RNA extraction.

Generation of liver organoids

All cell types were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 environment. iPSCs (clone code TkDA3) were kindly provided by K. Eto and H. Nakauchi (Tokyo University). Undifferentiated human iPSCs were maintained in mTeSR medium (Stemcell Technologies) on Matrigel (Corning)-coated feeder-free plates. HUVECs and MSCs were purchased from Lonza and maintained in Endothelial Growth Medium (EGM) or MSC Growth Medium (Lonza). Protocols for endoderm differentiation, hepatic specification, and liver organoid formation were as described previously (Takebe et al., 2014). Briefly, for definitive endoderm differentiation, iPSCs were dissociated by Accutase (Stemcell Technologies) and plated onto a Matrigel-coated dish. Medium was replaced with RPMI1640 containing 1% B27 without insulin (Life Technologies), 1 mM sodium butyrate (for the first 3 days), recombinant Wnt3a (R&D Systems; 50 ng/ml) and activin (R&D Systems; 100 ng/ml) for 5 to 6 days. For hepatic specification, definitive endoderm iPSCs (DE-iPSCs) were further treated with KnockOut DMEM (KO-DMEM) containing 20% knockout serum replacement, 1 mM L-glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen) and 1% DMSO (Sigma) for 3 days. Hepatic-specified endoderm iPSCs (HE-iPSCs) were then dissociated with TrypLE (Gibco) and mixed with dissociated MSCs and HUVECs at a ratio of 10:2:7. The cell mixture was plated on Matrigel bed (50% dilution of neat Matrigel, solidified at 37°C for 15 min) with medium for the liver organoid self-organization culture (LO medium). The LO medium consisted of 50% Hepatocyte Culture Medium (HCM, Lonza) and 50% EGM (Lonza). HCM was supplemented with HCM BulletKit (Lonza): transferrin, hydrocortisone, BSA fatty acid free, ascorbic acid, insulin, GA-1000, omitting human epidermal growth factor. EGM was supplemented with EGM BulletKit (Lonza): bovine brain extract, hEGF, hydrocortisone, fetal bovine serum (FBS), GA-1000 and ascorbic acid. After mixing HCM and EGM, 10 ng/ml recombinant hepatocyte growth factor (Sigma), 20 ng/ml recombinant oncostatin M (R&D Systems), 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), and 2.5% FBS (CELLect Gold, MP Biomedicals) were added to complete LO medium.

RNA-seq of liver organoids in hepatic differentiation

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and sequencing on Illumina HiSeq 2000 are described in the supplementary Materials and Methods. The RNA-seq reads were aligned to the human genome (GRCh37/hg19) using TopHat (version 2.0.13). The alignment data from TopHat were fed to an assembler, Cufflinks (version 2.2.1), to assemble aligned RNA-seq reads into transcripts. Annotated transcripts were obtained from the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and the Ensembl database. Transcript abundances were measured in fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM). The FPKM for each condition was normalized to the median of all samples, which is described as ʻrelative gene expression' on a log scale. First, to focus on genes related to the liver, we identified 3146 significantly overexpressed genes in primary hepatocytes by selecting ≥2-fold relative gene expression, using one-way ANOVA test, P<0.01 and Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing correction (see Table S1 for a full gene list). From the 3146 genes, a set of 442 genes was generated by selecting ≥2-fold relative gene expression in the day 2 liver organoid. A heatmap of the 442 genes in all conditions was produced (red, upregulated genes; blue, downregulated genes; see Table S2 for a full gene list). Hierarchical clustering analysis of the 442 gene expression profile was generated using GeneSpring 13.0-GX.

Liver organoid implantation into mice

Immunodeficient NOD scid gamma or NSG mice (8-12 weeks old, male; Jackson Laboratories) were kept according to protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee standards at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. NSG mice were fed Bactrim Chow (Test Diet). The liver organoids at day 2 of culture were implanted under the kidney capsule, as previously described (Takebe et al., 2013) and detailed in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Two-chamber culture

Twelve-well Transwell plates (Corning) with 0.4 μm-pore membrane insert were used. The membrane was coated with 7% Matrigel at room temperature for 15 min before use. After dissociation with TrypLE at 37°C for 5 min, washed 2.5×105 HE-iPSCs were plated in the upper chamber (2.23×105 cells per cm2); 2.5×105 HUVECs or 7.5×104 MSCs, or both together were plated in the lower chamber. As a reference, HE-iPSCs without cells in the lower chamber were cultured. The cells were cultured with LO medium in both chambers, with daily change of medium. We omitted HGF and oncostatin M (R&D Systems) from the LO medium in order to limit extrinsic growth factors.

Bile acid uptake assay and transcellular transport assay

The transcellular transport of bile acids was measured by the translocation of fluorescently labeled bile acid (CGamF; a kind gift from Dr Hofmann) between the culture chambers as previously described in the two-chamber Transwell system (Hofmann et al., 2010; Mita et al., 2005, 2006). Briefly, after hepatic differentiation of HE-iPSCs in the two-chamber culture, hepatocyte-like cells on the Transwell membrane were pre-incubated with a transport buffer (118 mM NaCl, 23.8 mM NaHCO3, 4.83 mM KCl, 0.96 mM KH2PO4, 1.20 mM MgSO4, 12.5 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, 1.53 mM CaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.4) for 20 min. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured with an EVOM2 probe (WPI). For the uptake assay, the cells were incubated with 10 µM CGamF for 60 min and supernatants were washed three times with PBS. Then cells were lysed with NaOH and the fluorescence intensity of the cell lysates measured at 490 nm. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to the protein amount in the cells, as measured by Bradford assay. For the basolateral to apical transport assay, 10 µM CGamF was added to the lower chamber and the transport buffer only to the upper chamber. Sixty minutes later, the transport buffer in the upper chamber was collected and fluorescence intensity measured at 490 nm. The fluorescent intensity was normalized to protein amounts of the hepatocyte-like cells. For apical-basolateral transport, CGamF was added to the upper chamber and fluorescence measured in the lower buffer.

Protein analysis by SOMAscan

The culture supernatants of the two-chamber system were collected after 24 h incubation at day 12. Three biological replicates were collected and combined as equal volumes, then submitted to the high-throughput SOMAscan assay in the laboratories of SOMALogic to quantify proteins as previously described (Hathout et al., 2015; Loffredo et al., 2013; Nahid et al., 2014). In brief, SOMAscan uses aptamers to precisely quantify 1180 proteins simultaneously in small fluid aliquots, at three different concentrations (5%, 0.3%, 0.01%) to measure proteins within the dynamic range of detection. The assay uses an equilibrium binding in solution of fluorophore-tagged SOMAmers and proteins, with a final capture of the nucleic acid, which is hybridized to a high-density antisense probe array to generate fluorescent signals that are directly related to the abundance of proteins in the original conditioned medium. After signal filtering (signal curating, normalization, fold change, cluster analysis), we obtained heatmap images with cluster analysis with GENE-E software (version 3.0.215, Broad Institute). Of the 1180 proteins tested, 228 in the supernatants of MSCs, HUVECs or MSCs+HUVECs were upregulated 3-fold or higher compared with iPSC-only culture supernatant. The proteins in the cluster were analyzed by the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis/Molecular Signature Database (GSEA/MSigDB, Broad Institute). We performed data validation of the assay by testing the albumin concentration using both ELISA and SOMAscan in aliquots from the same culture supernatant (Fig. S9).

Mouse primary hepatocyte isolation

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from male wild-type mice by collagenase perfusion through the portal vein (see the supplementary Materials and Methods).

Measurement of albumin, A1AT and urea

Human albumin and A1AT in the culture supernatant were quantified using ELISA kits (Bethyl Laboratories). Urea was measured using the QuantiChrom Urea Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems). For details, see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Quantitative PCR

The Brilliant III SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix Gene Expression Assay Kit and Mx3005p system (Stratagene) were used to quantify mRNA of target genes by real-time PCR as described in the supplementary Materials and Methods and Table S3.

Immunostaining of cultured cells

Protocols for immunostaining of monolayer cells on the Transwell membrane and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded liver organoids were modified from previous reports (Shivakumar et al., 2004). For details, see the supplementary Materials and Methods and Table S4.

Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining

Cells were incubated with periodic acid for 5 min, washed with distilled water, and incubated with freshly prepared Schiff's solution; nuclei were then stained with Hematoxylin. For details, see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Whole-mount staining of liver organoids

At 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 4 days and 6 days of co-culturing, liver organoids were fixed and stained using a protocol (supplementary Materials and Methods) modified from a previous study (Dipaola et al., 2013).

Transmission electron microscopy

Monolayer hepatocyte-like cells on the Transwell membrane were fixed and embedded in LX-112 (Ladd Research Industries). The monolayer was ultra-thin sectioned and viewed using a Hitachi H7650 electron microscope. For details, see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Statistics

All in vitro experiments were performed at least in triplicate. The numbers of mice or tissues used in each experiment are presented in the text or figure legends. Experimental values are expressed as mean±s.e.m., and statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student's t-test or by one-way or two-way ANOVA for comparison between three or more groups, followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison post-hoc test with significance set at P<0.05. Statistical analysis and graphic description were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr William Balistreri for advice on manuscript preparation, and Drs K. Eto, M. Otsu and H. Nakauchi at Tokyo University for providing iPSCs.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.A., J.W., J.A.B.; Methodology: A.A., E.A., C.W., P.S., C.M., M.H., T.T., J.W., J.A.B.; Formal analysis and investigation: A.A., E.A., R.M., T.M., K.P., C.M.; Data curation: A.A., R.M.; Writing – original draft preparation: A.A., J.A.B.; Writing – review and editing: A.A., E.A., P.S., K.P., T.T., J.W., J.A.B.; Funding acquisition: A.A., J.A.B.; Resources: A.A., E.A., C.M., T.T., J.A.B. Supervision: J.W. and J.A.B.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Foundation (Advanced/Transplant Hepatology Fellowship to A.A.) and in part by the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK078392; Bioinformatics Core of the Digestive Disease Research Core Center in Cincinnati). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

RNA-seq data are available at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE85223.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.142794.supplemental

References

- Araki Y., Katoh T., Ogawa A., Bamba S., Andoh A., Koyama S., Fujiyama Y. and Bamba T. (2005). Bile acid modulates transepithelial permeability via the generation of reactive oxygen species in the Caco-2 cell line. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 39, 769-780. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter M. A., Rowe C., Alder J., Harrison S., Hanley K. P., Park B. K., Kitteringham N. R., Goldring C. E. and Hanley N. A. (2010). Generating hepatic cell lineages from pluripotent stem cells for drug toxicity screening. Stem Cell Res. 5, 4-22. 10.1016/j.scr.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busso N., Chesne C., Delers F., Morel F. and Guillouzo A. (1990). Transforming growth-factor-beta (TGF-beta) inhibits albumin synthesis in normal human hepatocytes and in hepatoma HepG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 171, 647-654. 10.1016/0006-291X(90)91195-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler S. L., Dong H., Cardona D., Jia M., Zheng R., Zhu H., Crawford J. M. and Liu C. (2008). The antigen for Hep Par 1 antibody is the urea cycle enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1. Lab. Invest. 88, 78-88. 10.1038/labinvest.3700699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotman F. and Lemaigre F. P. (2006). Control of hepatic differentiation by activin/TGFbeta signaling. Cell Cycle 5, 168-171. 10.4161/cc.5.2.2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotman F., Jacquemin P., Plumb-Rudewiez N., Pierreux C. E., Van der Smissen P., Dietz H. C., Courtoy P. J., Rousseau G. G. and Lemaigre F. P. (2005). Control of liver cell fate decision by a gradient of TGF beta signaling modulated by Onecut transcription factors. Genes Dev. 19, 1849-1854. 10.1101/gad.340305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman A. and Dreesen O. (2009). Pluripotent stem cells and disease modeling. Cell Stem Cell 5, 244-247. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deharde D., Schneider C., Hiller T., Fischer N., Kegel V., Lubberstedt M., Freyer N., Hengstler J. G., Andersson T. B., Seehofer D. et al. (2016). Bile canaliculi formation and biliary transport in 3D sandwich-cultured hepatocytes in dependence of the extracellular matrix composition. Arch. Toxicol. 90, 2497-2511. 10.1007/s00204-016-1758-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipaola F., Shivakumar P., Pfister J., Walters S., Sabla G. and Bezerra J. A. (2013). Identification of intramural epithelial networks linked to peribiliary glands that express progenitor cell markers and proliferate after injury in mice. Hepatology 58, 1486-1496. 10.1002/hep.26485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehashi T., Koyama T., Ookawa K., Ohshima N. and Miyoshi H. (2007). Effects of oncostatin M on secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor and reconstruction of liver-like structure by fetal liver cells in monolayer and three-dimensional cultures. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 82, 73-79. 10.1002/jbm.a.31027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S. J., Gupta S. and Dhawan A. (2015). Cell therapy for liver disease: from liver transplantation to cell factory. J. Hepatol. 62, S157-S169. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelly J. L., Richoux J. P., Grignon G., Bouhnik J., Baussant T., Alhenc-Gelas F. and Corvol P. (1991). Immunocytochemical localization of albumin, transferrin, angiotensinogen and kininogens during the initial stages of the rat liver differentiation. Histochemistry 96, 7-12. 10.1007/BF00266754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak S., Reveiller M., Toia L., Ivanov A. I., Zhou Z., Redmond E. M., Godfrey T. E. and Peters J. H. (2015). Bile salts at low pH cause dilation of intercellular spaces in in vitro stratified primary esophageal cells, possibly by modulating Wnt signaling. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 20, 500-509. 10.1007/s11605-015-3062-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haridass D., Narain N. and Ott M. (2008). Hepatocyte transplantation: waiting for stem cells. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 13, 627-632. 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328317a44f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout Y., Brody E., Clemens P. R., Cripe L., DeLisle R. K., Furlong P., Gordish-Dressman H., Hache L., Henricson E., Hoffman E. P. et al. (2015). Large-scale serum protein biomarker discovery in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7153-7158. 10.1073/pnas.1507719112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann A. F., Hagey L. R. and Krasowski M. D. (2010). Bile salts of vertebrates: structural variation and possible evolutionary significance. J. Lipid Res. 51, 226-246. 10.1194/jlr.R000042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A., Kinoshita T. and Miyajima A. (2001). Oncostatin M and hepatocyte growth factor induce hepatic maturation via distinct signaling pathways. FEBS Lett. 492, 90-94. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02140-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A., Kojima N., Kinoshita T., Sakai Y. and Miyaijma A. (2002). Maturation of fetal hepatocytes in vitro by extracellular matrices and oncostatin M: induction of tryptophan oxygenase. Hepatology 35, 1351-1359. 10.1053/jhep.2002.33331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffredo F. S., Steinhauser M. L., Jay S. M., Gannon J., Pancoast J. R., Yalamanchi P., Sinha M., Dall'Osso C., Khong D., Shadrach J. L. et al. (2013). Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell 153, 828-839. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Yoshitomi H., Rossant J. and Zaret K. S. (2001). Liver organogenesis promoted by endothelial cells prior to vascular function. Science 294, 559-563. 10.1126/science.1063889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita S., Suzuki H., Akita H., Stieger B., Meier P. J., Hofmann A. F. and Sugiyama Y. (2005). Vectorial transport of bile salts across MDCK cells expressing both rat Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide and rat bile salt export pump. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 288, G159-G167. 10.1152/ajpgi.00360.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita S., Suzuki H., Akita H., Hayashi H., Onuki R., Hofmann A. F. and Sugiyama Y. (2006). Vectorial transport of unconjugated and conjugated bile salts by monolayers of LLC-PK1 cells doubly transfected with human NTCP and BSEP or with rat Ntcp and Bsep. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 290, G550-G556. 10.1152/ajpgi.00364.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahid P., Bliven-Sizemore E., Jarlsberg L. G., De Groote M. A., Johnson J. L., Muzanyi G., Engle M., Weiner M., Janjic N., Sterling D. G. et al. (2014). Aptamer-based proteomic signature of intensive phase treatment response in pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 94, 187-196. 10.1016/j.tube.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel G., Le Vee M., Moreau A., Stieger B., Parmentier Y. and Fardel O (2013). Functional expression and regulation of drug transporters in monolayer- and sandwich-cultured mouse hepatocytes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 49, 39-50. 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. E., Fleming H. E., Khetani S. R. and Bhatia S. N. (2014). Pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 504-513. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmukhappa K., Matte U., Degen J. L. and Bezerra J. A. (2009). Plasmin-mediated proteolysis is required for hepatocyte growth factor activation during liver repair. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12917-12923. 10.1074/jbc.M807313200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivakumar P., Campbell K. M., Sabla G. E., Miethke A., Tiao G., McNeal M. M., Ward R. L. and Bezerra J. A. (2004). Obstruction of extrahepatic bile ducts by lymphocytes is regulated by IFN-γ in experimental biliary atresia. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 322-329. 10.1172/JCI200421153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si-Tayeb K., Noto F. K., Nagaoka M., Li J., Battle M. A., Duris C., North P. E., Dalton S. and Duncan S. A. (2010). Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology 51, 297-305. 10.1002/hep.23354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K., Morisaki Y., Kuno S., Nagamoto Y., Harada K., Furukawa N., Ohtaka M., Nishimura K., Imagawa K., Sakurai F. et al. (2014). Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16772-16777. 10.1073/pnas.1413481111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe T., Sekine K., Enomura M., Koike H., Kimura M., Ogaeri T., Zhang R. R., Ueno Y., Zheng Y. W., Koike N. et al. (2013). Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature 499, 481-484. 10.1038/nature12271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe T., Zhang R.-R., Koike H., Kimura M., Yoshizawa E., Enomura M., Koike N., Sekine K. and Taniguchi H. (2014). Generation of a vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nat. Protoc. 9, 396-409. 10.1038/nprot.2014.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe T., Enomura M., Yoshizawa E., Kimura M., Koike H., Ueno Y., Matsuzaki T., Yamazaki T., Toyohara T., Osafune K. et al. (2015). Vascularized and complex organ buds from diverse tissues via mesenchymal cell-driven condensation. Cell Stem Cell 16, 556-565. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggelman A. M., Linthorst C., Boers W., Brand H. S. and Chamuleau R. A (1997). Transforming growth factor-beta-induced collagen synthesis by human liver myofibroblasts is inhibited by alpha2-macroglobulin. J. Hepatol. 26, 1220-1228. 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80455-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touboul T., Chen S., To C. C., Mora-Castilla S., Sabatini K., Tukey R. H. and Laurent L. C. (2016). Stage-specific regulation of the WNT/beta-catenin pathway enhances differentiation of hESCs into hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 64, 1315-1326. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruya K., Chikada H., Ida K., Anzai K., Kagawa T., Inagaki Y., Mine T. and Kamiya A. (2015). A paracrine mechanism accelerating expansion of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatic progenitor-like cells. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 1691-1702. 10.1089/scd.2014.0479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Shinohara M., Komori K., Sakai Y., Matsui H. and Osada T. (2014). The importance of physiological oxygen concentrations in the sandwich cultures of rat hepatocytes on gas-permeable membranes. Biotechnol. Prog. 30, 1401-1410. 10.1002/btpr.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi F., Liu G.-H. and Izpisua Belmonte J. C. I. (2012). Human induced pluripotent stem cells derived hepatocytes: rising promise for disease modeling, drug development and cell therapy. Protein Cell 3, 246-250. 10.1007/s13238-012-2918-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]