Abstract

A novel kinesin, GhKCH1, has been identified from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fibers. GhKCH1 has a centrally located kinesin catalytic core, a signature neck peptide of minus end-directed kinesins, and a unique calponin homology (CH) domain at its N terminus. GhKCH1 and other CH domain-containing kinesins (KCHs) belong to a distinct branch of the minus end-directed kinesin subfamily. To date the KCH kinesins have been found only in higher plants. Because the CH domain is often found in actin-binding proteins, we proposed that GhKCH1 might play a role in mediating dynamic interaction between microtubules and actin microfilaments in cotton fibers. In an in vitro actin-binding assay, GhKCH1's N-terminal region including the CH domain interacted directly with actin microfilaments. In cotton fibers, GhKCH1 decorated cortical microtubules in a punctate manner. Occasionally GhKCH1 was found to be associated with transverse-cortical actin microfilaments, but never with axial actin cables in cotton fibers. Localization of GhKCH1 on cortical microtubules was independent of the integrity of actin microfilaments. Thus, GhKCH1 may play a role in organizing the actin network in coordination with the cortical microtubule array. These data also suggest that flowering plants may employ unique KCHs to coordinate actin microfilaments and microtubules during cell growth.

Among different plant cell types, microtubules and actin microfilaments are organized into distinct arrays (Cyr and Palevitz, 1995; Wasteneys and Galway, 2003). Various cytoskeletal arrays often correspond to the growth pattern of these cells. The cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber is an extreme example of cell growth in planta. When cotton fibers initiate in the ovule epidermis after flowering, microtubules assume a random-cortical pattern (Seagull, 1992). This is later replaced by a transverse-cortical array and finally by an array that is steeply pitched toward the growth axis (Seagull, 1992). These changes in microtubule organization may correlate with the pattern of fiber growth, starting from simple diffuse elongation at early stages followed by rapid elongation of fibers (Tiwari and Wilkins, 1995). Pharmacological evidence suggests that microtubules are indispensable for cotton fiber growth (Seagull, 1990). Depolymerization of actin microfilaments by cytochalasin D also disrupts fiber growth (Seagull, 1990). However, it is not clear how organized microtubules and actin microfilaments influence cotton fiber growth.

In plant cells, microtubules and actin microfilaments often colocalize or are distributed in close proximity to one another. In root hairs, actin microfilaments often parallel the microtubule distribution (Ridge, 1988). Actin microfilaments sometimes colocalize with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers (Andersland et al., 1998). In cotton fibers, disruption of actin microfilaments causes parallel cortical microtubules to become randomly organized (Seagull, 1990). Therefore, it is clear that microtubules and actin microfilaments directly or indirectly interact, and such an interaction most likely exerts a physiological role in plant cell growth.

The interaction between microtubules and actin microfilaments could be mediated by proteins that interact with both cytoskeletal elements or by two connected proteins that each interact with one element. Considerable evidence from animals and fungi indicates functional cooperation between microtubules and actin microfilaments, and a number of proteins that mediate the interaction between the two have been identified (Goode et al., 2000). In tobacco BY-2 cells, a 190-kD polypeptide interacts with both microtubules and actin microfilaments (Igarashi et al., 2000). It has been suggested that this protein may play a role in the interaction between microtubules and actin microfilaments in vivo.

Among the 61 putative kinesins encoded in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome, 7 are notable for the presence of a unique calponin homology (CH) domain at the N terminus of each polypeptide (Reddy and Day, 2001). Calponin is an actin-binding protein abundantly present in muscle cells, and the conserved CH domain is often found in other actin-binding proteins as well (Gimona et al., 2002; Korenbaum and Rivero, 2002). Although the CH domain itself probably does not bind to actin microfilaments directly, it may contribute to actin-binding indirectly (Gimona et al., 2002). But two tandem CH domains in fimbrins directly bind to actin (Klein et al., 2004). Therefore, plant kinesins containing the CH domain (KCH) may act as dynamic links between microtubules and actin microfilaments.

Because of the interdependence between microtubules and actin microfilaments in highly differentiated cotton fibers (Seagull, 1990), we determined whether the KCHs were expressed in these cells and whether they contributed to the growth and development of cotton fibers. Here, we report the identification of one such KCH from cotton, GhKCH1. We demonstrate that GhKCH1 interacts with actin microfilaments in vitro and is associated with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers.

RESULTS

Analysis of the GhKCH1 Sequence

To identify kinesins expressed in developing cotton fibers, genomic fragments amplified using kinesin degenerate primers were used to screen a cotton fiber-specific cDNA library.

One of the recovered clones contained the full-length coding sequence for a kinesin (GenBank accession no. AY695833). This GhKCH1, or cotton kinesin with CH domain 1, is 1,018 amino acids in length (Fig. 1A) and has a predicted molecular mass of 112 kD and a pI of 6.57.

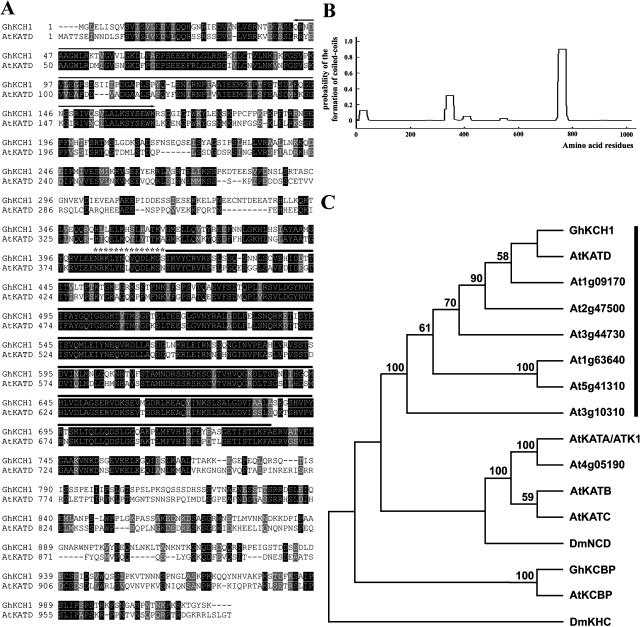

Figure 1.

Sequence of GhKCH1. A, Alignment of GhKCH1 with AtKATD. Identical amino acid residues are shaded in black, and similar residues are shaded in gray. The catalytic core is highlighted by thick line. The neck motif of minus end-directed kinesins is marked with asterisks. The predicted CH domain is highlighted with a thin arrowed line. B, Prediction of coiled coils by the Lupas algorithm. The x axis represents the position of amino acid residues, and the y axis represents the probability of the formation of coiled coils. A probability value greater than 0.5 indicates that the corresponding region most likely forms a coiled coil. C, Phylogenetic analysis of GhKCH1 and representatives of plant minus end-directed kinesins, and two animal kinesins. Phylogenetic analysis of kinesin motor domains was performed in PAUP, version 4.0 using maximum parsimony. The phylogenetic tree shown was obtained by using a heuristic search method with random stepwise addition of sequences. It was rooted arbitrarily by using DmKHC as an outgroup. Boostrap support values were obtained from 100 replicates. Only bootstrap values greater than 50 were shown on the tree. The clade containing the KCH kinesins was highlighted by a vertical line.

GhKCH1 has a kinesin catalytic core located approximately in the middle of the polypeptide (Fig. 1A). At the very N-terminal side of the catalytic core, it contains a sequence of NRKLYNQVQDLKGS, which matches the consensus neck motif found among kinesins that move toward the minus end of microtubules (Fig. 1A; Endow, 1999). Thus, GhKCH1 is probably a microtubule minus end-directed motor.

At the N terminus, there is a CH domain (Fig. 1A). A coiled-coil domain was predicted at the C-terminal side to the motor domain using the Lupas algorithm (Fig. 1B; Lupas et al., 1991). The rest of the C-terminal part of the polypeptide showed no sequence similarity to any other known protein.

We examined the relationship between GhKCH1 and other kinesins in the database. At the amino acid level, GhKRP1 most closely related to the Arabidopsis KATD kinesin with approximately 54% overall sequence identity (Fig. 1A; Tamura et al., 1999). The sequence conservation is most pronounced at the motor region (80% identity) and in the CH domain (66% identity; Fig. 1A). AtKATD forms a predicted coiled coil at a similar region as GhKCH1 (data not shown).

To determine the evolutionary relationship between GhKCH1 and other Arabidopsis kinesins containing the neck motif of minus end-directed kinesins, a phylogenetic analysis was carried out by examining only the catalytic core and the neck sequence. We found that GhKCH1 and other AtKCHs formed a clade (Fig. 1C). The C-terminal motor kinesin AtKATA/ATK1 and three other closely related kinesins formed a branch with the fly NCD kinesin (Fig. 1C). Previously, we have reported another minus end-directed kinesin, GhKCBP, from cotton fibers (Preuss et al., 2003). GhKCBP and its Arabidopsis ortholog AtKCBP, however, were more divergently related to GhKCH1 than other minus end-directed kinesins.

The N-Terminal Portion of GhKCH1 Interacted with Actin Microfilaments in Vitro

Many actin-binding proteins, including plant fimbrins, contain the CH domain, which contributes to their interaction with actin microfilaments (McCurdy and Kim, 1998; Kovar et al., 2000b; Klein et al., 2004). We wished to determine whether the GhKCH1 protein could interact with actin microfilaments through the N-terminal portion that includes its CH domain. Purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-GhKCH1-N fusion protein was used in a high-speed in vitro cosedimentation assay. The Arabidopsis fimbrin (AtFim1) protein was used as a positive control as reported previously (Kovar et al., 2000b). Bacterially expressed GST-GhKCH1-N fusion protein largely remained in the supernatant in the absence of actin microfilaments (Fig. 2A). In the presence of actin microfilaments, however, GST-GhKCH1-N cosedimented with polymerized actin microfilaments and was found in the pellet fraction (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with AtFim1 (Fig. 2A).

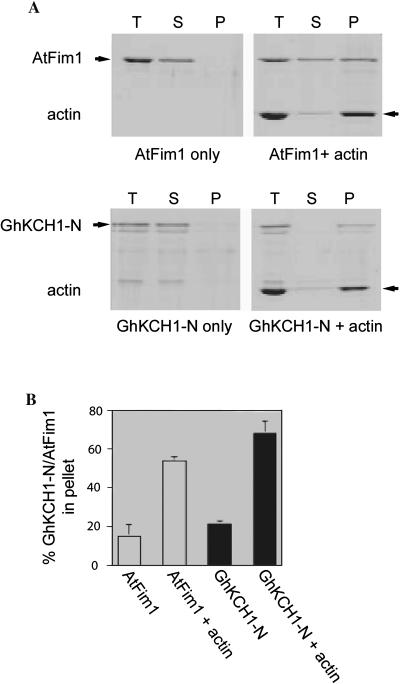

Figure 2.

GhKCH1 binds to maize pollen actin microfilaments. A, AtFim1 or the GhKCH1 fragment GhKCH1-N alone, and AtFim1 or GHKCH-N1 plus actin microfilaments were incubated then centrifuged. Total mixture prior to centrifugation (T), supernatant (S), and pellets (P) were separated by SDS-PAGE. Considerably more GhKCH1-N and AtFim1 sedimented in the presence of actin microfilaments, compared with in the absence of actin. Positions of AtFim1 and GhKCH1-N fusion proteins were marked by arrows on the left at approximately 76 and 100 kD, respectively. The actin position was marked by arrows on the right at approximately 42 kD. B, The experiment shown in A was repeated three times, and the gels were scanned to quantify the percent of total AtFim1 and GhKCH1-N that sedimented in the absence or presence of actin microfilaments, as described in “Materials and Methods.” The percentage of AtFim1 that sedimented in the absence of actin was 15.0 ± 6.0 (mean ± sd). The percentage of AtFim1 that sedimented in the presence of actin was 54.0 ± 2.1. In comparison, the percentage of GhKCH1-N that sedimented in the absence of actin was 21.0 ± 1.5, whereas in the presence of actin it was 68.0 ± 6.2.

The binding activities of GST-GhKCH1-N and AtFim1 were measured by densitometry. In the absence of actin microfilaments, 15% of the AtFim1 was found in the pellet, whereas in the presence of actin microfilaments, 54% of the AtFim1 was found in the pellet (Fig. 2B). By comparison, 21% of the GST-GhKCH1-N was found in the pellet in the absence of actin microfilaments, whereas 68% of the GST-GhKCH1-N was found in the pellet in the presence of actin microfilaments (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that the N-terminal portion of GhKCH1 binds to actin microfilaments.

Expression of GhKCH1 in Cotton Fibers

To detect GhKCH1 in cotton fibers, antibodies were raised against the N terminus of the protein (amino acids 1–489; anti-GhKCH1-N1 and anti-GhKCH1-N2) and the C terminus of the protein (amino acids 885–1,021; anti-GhKCH1-C1 and anti-GhKCH1-C2). Affinity-purified anti-GhKCH1-N1 antibodies recognized a 120-kD band separated by SDS-PAGE, close to the predicted size of GhKRP1 (Fig. 3A). Affinity-purified anti-GhKCH1-N2, anti-GhKCH1-C1, and anti-GhKCH1-C2 antibodies from other three animals all recognized a similar band (data not shown). Because the anti-GhKCH1-N1 antibodies rendered the cleanest result with no additional bands by immunoblotting, they were used for further characterization of GhKCH1 in cotton fibers.

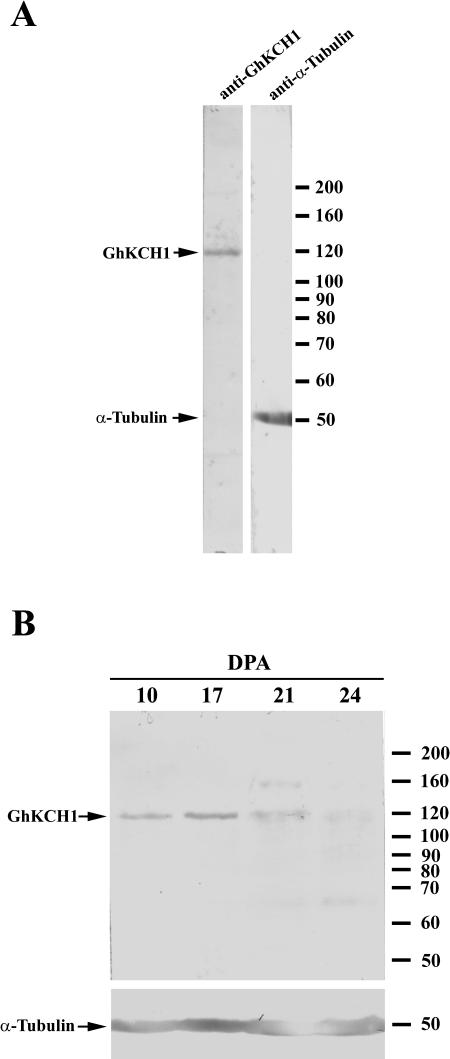

Figure 3.

Immunoblotting analysis of GhKCH1. A, Protein extracts from 10-DPA cotton fibers were probed with the anti-GhKCH1-N1 and the DM1A anti-α-tubulin antibodies. Anti-GhKCH1-N1 detected a single band at a molecular mass of approximately 120 kD. DM1A detected α-tubulin at approximately 50 kD. Positions of molecular mass standards were shown on the right. B, Protein level of GhKCH1 at different stages of cotton fiber development. Equal amount proteins from 10, 17, 21, and 24 DPA were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Duplicate blots were probed with anti-GhKCH1-N1 and DM1A. While the α-tubulin protein level gradually increased following the development of cotton fibers, GhKCH1 peaked at 17 DPA. After 21 DPA, diffuse GhKCH1 signal was detected.

Because cotton fibers have distinct growth stages associated with the primary and secondary cell wall synthesis, we wondered whether GhKCH1 demonstrated a stage-dependent protein abundance. When proteins prepared from 10, 17, 21, and 24 d post anthesis (DPA) were probed with anti-GhKCH1-N1, clear GhKCH1 signal was detected in the 10- and 17-DPA samples (Fig. 3B). The anti-GhKCH1 signal peaked in the 17-DPA sample (Fig. 3B). Diffuse and weaker signals were detected in 21- and 24-DPA samples (Fig. 3B). A weak and diffuse signal was occasionally detected near the 160-kD marker in the 21-DPA sample. It was believed to be a nonspecific one, as it was not consistently seen. When identical samples were probed with the DM1A anti-α-tubulin antibody, a gradual increase of the α-tubulin level was observed (Fig. 3B). An increase of tubulin protein level during fiber development has been reported before (Kloth, 1989; Preuss et al., 2003). The weak signal in 21- and 24-DPA samples was unlikely due to proteolysis during sample preparation because α-tubulin did not show any sign of degradation. Therefore, GhKCH1 showed a stage-dependent variation of its protein level.

GhKCH1 Decorates Cortical Microtubules in Cotton Fibers

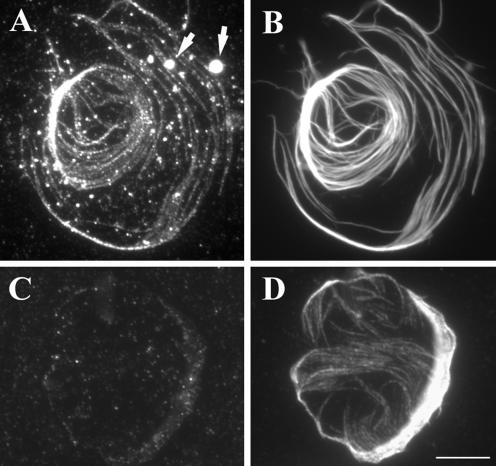

To gain insight into the function of GhKCH1, we determined its intracellular-localization pattern in cotton fibers. Because the anti-GhKCH1-N1 antibodies gave the lowest background on immunoblots, they were used for immunofluorescence experiments. We first used cytoplasts isolated from cotton fibers in the presence of the microtubule-stabilizing agent taxol (Fig. 4). The cytoplasts contained massive microtubule bundles induced by taxol treatment (Fig. 4, B and D). GhKCH1 decorated these microtubule bundles in a punctate manner, and the signal intensity correlated with the size of different bundles (Fig. 4A). In addition, GhKCH1 was also detected in particles near microtubule bundles and associated with organelle-like structures (Fig. 4A). In a control experiment, the antigen GhKCH1-N expressed as a 6XHis-tagged fusion protein was used to compete with endogenous GhKCH1 in the cytoplasts. Signals along cortical microtubules and organelles were largely removed (Fig. 4C). Some random small particles were still stained, indicating that these remaining signals were background ones. Therefore the immunofluorescence signal along microtubules and on organelle-like structures detected by anti-GhKCH1-N reflected the localization of GhKCH1 in cotton fibers.

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescent localization of GhKCH1 in cotton cytoplasts. A and B, Dual localization of GhKCH1 (A) and microtubules (B) in a cytoplast. GhKCH1 appeared in a punctate manner along taxol-stabilized microtubules. GhKCH1 was also detected on large organelle-like structures (arrows in A). C and D, Specificity of GhKCH1 localization. After anti-GhKCH1-N1 antibodies were preabsorbed with His-GhKCH1-N, very little signal was detected for GhKCH1 (C) in a cytoplast, which still contained microtubule network (D). Scale bar = 10 μm.

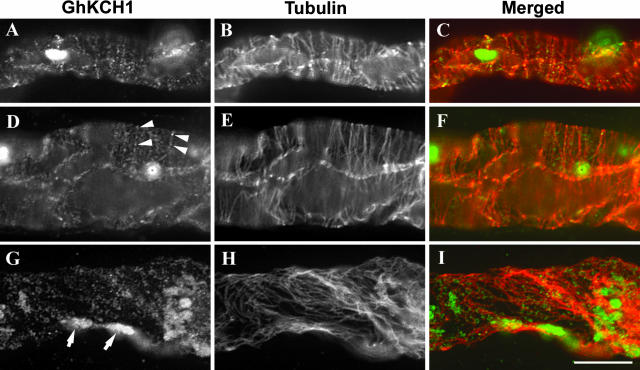

Anti-GhKCH1-N1 was then used to detect GhKCH1 in intact cotton fibers. At early stages of cotton fiber development, microtubules were organized to a parallel cortical array that was perpendicular to the growth axis of cotton fibers (Fig. 5, B and E). GhKCH1 appeared as particles along the cortical microtubules (Fig. 5, A–F). The GhKCH1 signal was present only in the focal plane where cortical microtubules were in focus (Fig. 5, D–F). At later stages of cotton fiber development, cortical microtubules were more bundled and appeared in a steeply pitched manner relative to the axis of growth (Fig. 5H). GhKCH1 signals were still detected along these microtubules (Fig. 5, G–I). It was noted that GhKCH1 signals along cortical microtubules in the intact cotton fibers were weaker and more punctate than those along microtubules in the cytoplasts. The difference was largely caused by microtubule-bundling phenomenon associated with the taxol treatment during cytoplast preparation. Similar to what was observed in cytoplasts, GhKCH1 also decorated organelle-like structures inside cotton fibers (arrows in Fig. 5G). Because the GhKCH1 signal was significantly stronger on these organelles than along microtubules, the organelle-bound signal was saturated to visualize microtubule-bound signal. These organelles often appeared among microtubules, but it was not clear whether they were directly associated with cortical microtubules. When samples of cotton fibers were stained to reveal GhKCH1 and mitochondria by the specific dye MitoTracker Red, these organelles were demonstrated to be mitochondria (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Dual localizations of GhKCH1 and microtubules in cotton fibers. Signals of GhKCH1 (A, D, and G), microtubules (B, E, and H), and superimposed images with GhKCH1 in green and microtubules in red (C, F, and I). A to F, Cotton fibers with parallel transverse cortical microtubules (B and E) had GhKCH1 localized in a punctate manner (A and D) along these microtubules (arrowheads). There is no difference of GhKCH1 in the very young fiber shown in A to C and the expanded fiber in D to F. G to I, A fiber containing steeply pitched cortical microtubules (H) still had GhKCH1 (G) localized along these microtubules (I). Note that GhKCH1 also decorated organelle-like structures (arrows in G). Scale bar = 10 μm.

GhKCH1 May Interact with Transverse Actin Microfilaments But Not Axial Cables

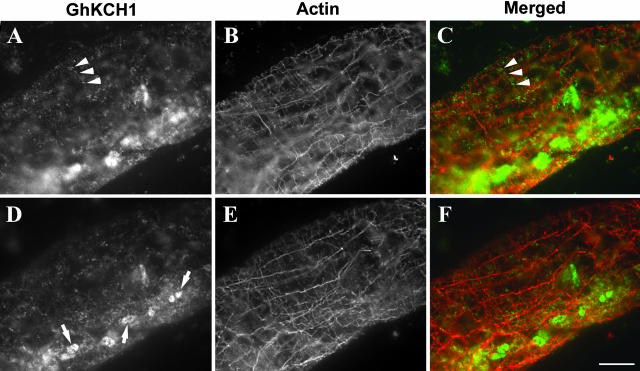

Because the N-terminal domain of GhKCH1 was demonstrated to cosediment with actin microfilaments, we wanted to determine whether it interacted with actin microfilaments in cotton fibers. Dual localization of GhKCH1 and actin was carried out. Two populations of actin microfilaments were revealed in cotton fibers (Fig. 6, B and E). Parallel fine actin microfilaments were found at the cell cortex and were arranged perpendicularly to the growth axis of cotton fibers (Fig. 6B). When the inner area of the cytoplasm was brought into focus, longitudinal cables of actin microfilaments were observed (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Dual localization of GhKCH1 and actin microfilaments. A to C, An optical section through the cortex of a cotton fiber. Fine transverse actin microfilaments were shown (B). GhKCH1 appeared in particles in the cell cortex (A). In a pseudocolored image (C), some GhKCH1 signals were detected along cortical actin microfilaments (arrowheads). D to F, An optical section deeper into the fiber cytoplasm. Axial actin cables were visualized (E). Less GhKCH1 signal was detected in this region (D). No GhKCH1 signal was detected along the axial actin cables in a pseudocolored image (F). Note that organelle-like structures were again decorated by GhKCH1 (arrows in D). To visualize punctate GhKCH1 signals, organelle-bound signals were satuarated. Scale bar = 10 μm.

At the cotton fiber cortex, GhKCH1 signal was detected again in a punctate manner and associated with larger organelle-like structures (Fig. 6, A and D). Although the majority of punctate signal was not associated with cortical actin filaments, some GhKCH1 spots were aligned along a few actin microfilaments (arrows in Fig. 6, A–C). The GhKCH1 signal was never detected along the axial actin cables (Fig. 6, D–F). Our results indicate that GhKCH1 may interact with cortical actin microfilaments in cotton fibers.

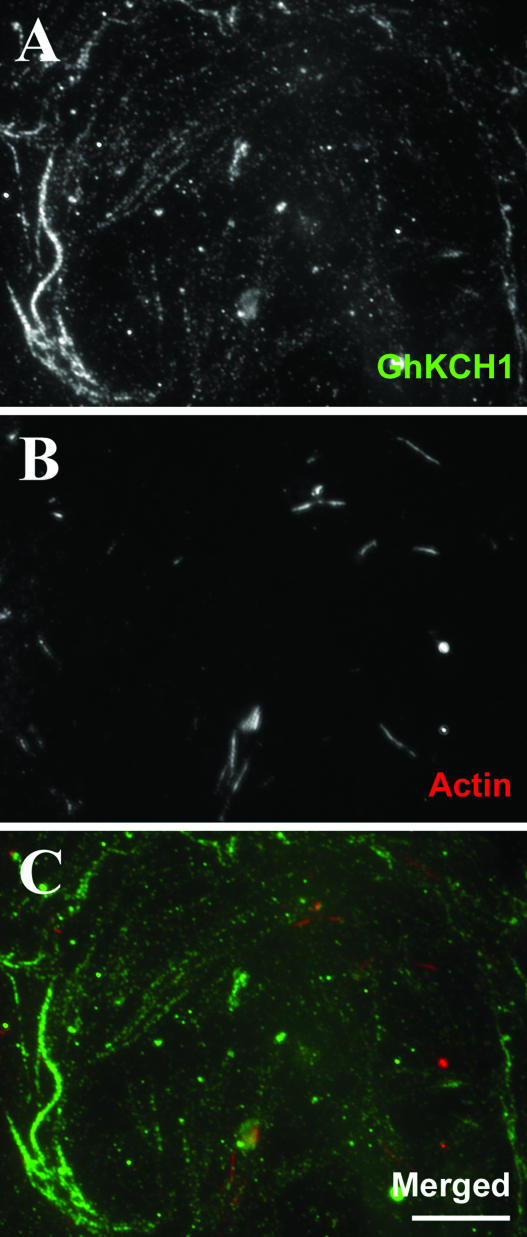

Localization of GhKCH1 along Cortical Microtubules Is Independent of Actin Microfilaments

Because the N-terminal region of GhKCH1 was able to interact with actin microfilaments in vitro, we tested whether the interaction was important for intracellular localization of GhKCH1. The actin polymerization inhibitor Latrunculin A was used to disrupt actin microfilaments in cytoplasts. In all cytoplasts examined, we observed that GhKCH1 still decorated cortical microtubules as in control cells. In a cytoplast in which only a few very short actin microfilaments were present, GhKCH1 was still present in a punctate pattern (Fig. 7, A–C). Such punctate signals were along microtubules when cytoplasts were stained with anti-tubulin at the same time (data not shown). GhKCH1 did not colocalize with the remaining actin stubs (Fig. 7C). Therefore, our results indicated that GhKCH1 localization along cortical microtubules in cotton fibers was independent of actin microfilaments.

Figure 7.

GhKCH1 localization is independent of the integrity of actin microfilaments. A, GhKCH1 localization in a cytoplast which was treated with Latrunculin A. Punctate GhKCH1 signals were still detected along filamentous structures. B, A few stubs of actin microfilaments were left. C, Pseudocolored image showing GhKCH1 was not colocalized with the actin stubs. Scale bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

This article reports the identification and partial characterization of a novel actin-binding kinesin, GhKCH1, from cotton fibers. No other plant kinesins have been reported to interact with actin microfilaments. Our results indicate that GhKCH1 and probably other plant KCHs interact with actin microfilaments. GhKCH1 is associated with cortical microtubules and some cortical actin microfilaments in cotton fibers. This report provides direct evidence on the intracellular localization of a KCH kinesin. Our results provide hints about the potential role of KCHs in plant cells.

KCHs Are Unique Actin-Binding Kinesins

Prior to this report, two kinesins have been reported to interact with actin microfilaments (Kuriyama et al., 2002; Iwai et al., 2004). A variant of the mammalian MKLP1/CHO1 kinesin has an actin-binding domain encoded by an exon, which is spliced in a different variant (Kuriyama et al., 2002). Kinesins in the MKLP1/CHO1 subfamily play critical roles in cell separation during cytokinesis in animal cells (Matuliene and Kuriyama, 2004). This actin-binding variant of MKCP1/CHO1 may interact directly with the contractile ring during cytokinesis to ensure completion of contraction. There was no sequence in the plant database that significantly matches the unique actin-binding site in this MKLP1/CHO1 variant. The other actin-binding kinesin, DdKin5 from Dictyostelium discoideum, contains an actin-binding site in its C-terminal tail region, which has no relationship with any known actin-binding proteins (Iwai et al., 2004). DdKin5 localizes to the protrusion edge of crawling Dictyostelium cells and is proposed to be a potential cross-linker of actin microfilaments and microtubules associated with specific actin-based structures (Iwai et al., 2004). Again, we could not detect any plant sequence that is similar to the actin-binding site in DdKin5.

GhKCH1 and other KCHs differ from these two actin-binding kinesins in several aspects. First, the region responsible for actin binding is located at the N-terminal region of KCHs, which contains the CH domain. To date, this type of kinesins has been found only in plants. Secondly, KCHs are probably microtubule minus end-directed motors as predicted by the signature neck motif juxtaposed to the catalytic core. Their motor domains are located in the middle region of the polypeptides (Reddy and Day, 2001). Both MKLP1/CHO1 kinesins and DdKin5 are plus end-directed motors with the motor domain located at the N terminus (Nislow et al., 1992; Iwai et al., 2004). Finally, KCHs and MKLP1/CHO1 kinesins and DdKin5 appear to have different functions. MKLP1/CHO1 kinesins are essential for the formation of the midbody matrix required for cleavage furrow-mediated cytokinesis (Matuliene and Kuriyama, 2002). DdKin5 probably mediates the interaction between microtubules and actin microfilaments in the protruding edge of actively crawling cells (Iwai et al., 2004). Interphase Dictyostelium cells have microtubules with plus ends pointing toward the cell edge and minus ends at the centrosomes. In interphase plant cells, like cotton fibers, the cortical microtubules have mixed polarities (Shaw et al., 2003). How a minus end-directed kinesin like GhKCH1 is employed to assist cell growth is currently under investigation.

Because the CH domain had often been considered as the actin-binding site, we took efforts to test whether the CH domain of the KCH kinesins was able to bind to actin microfilaments by itself. Our results indicated that the CH domain alone did not constitute an actin-binding site (Y.-R.J. Lee and B. Liu, unpublished data). This result is consistent with recent findings on animal CH domain proteins, which indicate that single CH domains are not actin-binding domains (Gimona and Winder, 1998). Therefore, either a small portion outside the CH domain at the N-terminal region of GhKCH1 or the entire N-terminal region is required for the binding. Ongoing experiments are aimed at addressing this question.

Potential Roles of GhKCH1 in Cotton Fiber Development

There are several potential roles that GhKCH1 may be playing in the growth and development of cotton fibers. GhKCH1 may act as an active transporter of actin microfilaments during the development of cotton fibers. Because GhKCH1 is predicted to be a minus end-directed motor, it would be reasonable to predict that it may be organizing actin microfilaments in reference to minus ends of cortical microtubules. Because cortical microtubules undergo major reorganization during cotton fiber development (Seagull, 1992), actin microfilaments would need to be reorganized according to the newly established microtubule arrays. Although it is known that actin microfilaments are critical for cotton fiber development, how they contribute to fiber growth is still elusive. One could predict that actin microfilaments may act as tracks along which vesicles/organelles are transported at the cell cortex and/or along the cotton fiber cells by yet-to-be-identified myosins. Fiber cells of cotton undergo rapid cell expansion before 21 DPA (Kim and Triplett, 2001). Because our data showed that the GhKCH1 expression peaked around 17 DPA, we could predict that GhKCH1's role(s) could be to organize actin microfilaments in the cell cortex so that myosin-dependent transport can take place.

Conversely, GhKCH1 could function in the organization of microtubules by anchoring them at actin microfilaments. Such an activity could be critical for establishing and/or maintaining the parallel array of cortical microtubules up to 21 DPA. The parallel arrangement of cortical microtubules is critical for the elongation of fiber cells.

We are also inspired by a recent report indicating that a CH domain can inhibit microtubule-stimulated ATPase activity of a minus end-directed motor NCD (Fattoum et al., 2003). Both phylogenetic analysis and organization of the motor domain (i.e. the catalytic core and the signature neck motif) have indicated that GhKCH1 and other KCHs belong to the minus end-directed kinesins including NCD (Fig. 1). It is possible that GhKCH1 and other KCHs are inactive due to intramolecular inhibition of motor activity by the CH domain. However, this inhibitory effect could be released by interacting with actin microfilaments. Therefore, although GhKCH1 may be present widely along microtubules inside cotton fibers, only in regions where actin microfilaments are present in a close proximity would GhKCH1 be activated to carry out its motor activities.

Attempts have been made to determine the function of GhKCH1 by analyzing phenotypes of null mutations of the AtKATD gene, encoding the most similar KCH in Arabidopsis. T-DNA insertions within different exons of the AtKATD gene did not result in a noticeable phenotype under laboratory conditions (L. Lu and B. Liu, unpublished data). This could be due to functional redundancy existing among KCHs in Arabidopsis. Further genetic analyses are needed to elucidate functions of these plant-specific kinesins in Arabidopsis.

In summary, our results provide evidence that GhKCH1 and other plant KCHs are unique plant kinesins that interact with actin microfilaments. They have probably been evolved to take on unique functions that require coordination of microtubules and actin microfilaments in plant cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum cv Coker 130) plants were grown under greenhouse conditions. Flowers were marked at anthesis, and at indicated times the bolls were removed.

Isolation of GhKCH1 cDNA

Genomic DNA was extracted from young cotton leaves using a standard CTAB genomic-DNA isolation method (Doyle and Doyle, 1990). Two degenerate primers, KRP5B (forward), 5′-GATCGGATCCTT(C/T)GC(A/T/G/C)TA(C/T)GGTCA(A/G)AC(A/T/G/C)GG-3′ and KRP3E (reverse), 5′-AGTCGAATTC(A/G)CT(A/T/G/C)CC(A/T/G/C)GC(A/T/G/C)A(A/G)(A/G)TC(A/T/G/C)AC-3′) were designed corresponding to conserved kinesin peptides FAYGQTG and VDLAGS, respectively. The primers allowed us to amplify DNA fragments by PCR encoding a region of the motor domain of kinesins. PCR reaction was carried out using the Taq polymerase by the following procedure: 94°C for 3 min; 5 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 1.5 min at 52°C, and 1 min at 72°C; 30 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and 10 min at 72°C. PCR products of approximately 500 to 700 bp in size were excised and used as a probe to screen a cotton fiber-specific cDNA library as previously described (Preuss et al., 2003). Positive clones were picked up, and corresponding plasmids were rescued and purified. To verify that these plasmids contained kinesin cDNA sequences, they were then tested again by PCR with KRP5B and BKRP3E: 5′-ATGAATTC(A/G)TC(A/T/G/C)C(G/T)(A/G)TA(A/T/G/C)GG(A/T/G/C)A(G/T)(A/G)TG-3′, corresponding to the kinesin peptide H(V/I)PYRD. A clone containing the full-length coding sequence of GhKCH1 was sequenced at a commercial laboratory (Davis Sequencing, Davis, CA).

Sequence Analysis

The accession numbers of kinesins used in the analysis are: GhKCH1, AY695833; GhKCBP, AAP41107; AtKATA/ATK1, Q07970; AtKATB, T06048; AtKATC, S48020; AtKATD, O81635; At1g09170, NP_172389; At1g63640, NP974079; At2g47500, AAO42115; At3g10310, NP_187642; At3g44730, AAK92458; At4g05190, AAQ82843; At5g41310, NP_198947; AtKCBP, AAC49901; DmNCD, CAA40713; and DmKHC, P17210. Alignment of GhKCH1 and AtKATD was performed using the Vector NTI software package (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Prediction of coiled coils was performed according to the Lupas algorithm (Lupas et al., 1991). Sequences of the catalytic core and the neck motifs were used in the phylogenetic analysis in PAUP, version 4.0 (Sinaur Associates, Sunderland, MA) by using maximum parsimony. The phylogeniec tree shown was obtained by using a heuristic search method with random stepwise addition of sequences and was rooted arbitrarily using DmKHC as an outgroup. Boostrap support values were obtained from 100 replicates.

Fusion Protein Preparation and Antibody Production

Constructs for GST fusion proteins were made using the pGEX-KG plasmid (Guan and Dixon, 1991). At first, the full-length GhKCH1 cDNA was amplified by the forward primer, 5′-CATGCCATGGGATTGGAATTGATTTC-3′ and the reverse primer, 5′-ACGCTCGAGCCAGTTCTCTTAACATTG-3′. The NcoI and XhoI sites were introduced in the primers at the 5′ and the 3′ ends, respectively. The PCR reaction was carried out using the Pfu enzyme (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with the following procedure: 2 min at 94°C; 25 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 1 min at 49°C, and 3 min at 72°C; and 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEX-KG plasmid at the NcoI and XhoI sites to give rise to the GST-KCH1 plasmid. The GST-GhKCH1-N (encoding the N-terminal region of GhKCH1) construct was made by excising the NcoI/SacI fragment from the GST-GhKCH1 and religating into the pGEX-KG vector at the NcoI and SacI sites. The GST-GhKCH1-C (C-terminal GhKCH1) construct was made by excising the BamHI/XhoI fragment of GST-GhKCH1 and religating it into the pGEX-KG vector. The GST-fusion proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen, Madison, WI). GST-GhKCH1-N and GST-GhKCH1-C cell lysates were purified over a glutathione affinity column as described by the manufacturer (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Purified GST-fusion proteins were quantified by the Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976) and separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels to check the Mrs and purity of the proteins.

Constructs of His-tagged fusion proteins were made using the pQE plasmids (Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA). For constructing His-GhKCH1-N, a BamHI/SacI fragment was excised from the GST-GhKCH1-N plasmid and ligated into the pQE-31 vector at the corresponding sites. For the construction of His-GhKCH1-C, a BamHI/HindIII fragment was excised from the GST-GhKCH1-C plasmid and ligated into the pQE-30 vector at the corresponding sites. These His-tagged proteins were expressed in M15pREP4 cells (Qiagen USA) and purified over a nickel column following manufacturer's instruction (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA).

Polyclonal anti-GhKCH1-N antibodies were raised in two rabbits (anti-GhKCH1-N1 and anti-GhKCH1-N2) at a University of California-Davis facility (Comparative Pathology Laboratory). Initial immunization was done with 500 μg of GST-GhKCH1-N, and subsequent four-boost injections were done with 250 μg protein for each injection. Polyclonal anti-GhKCH1-C antibodies were raised in two rats (anti-GhKCH1-C1 and anti-GhKCH1-C2) at a commercial facility (Antibodies, Davis, CA). The initial immunization was with 200 μg of purified GST-GhKCH1-C protein, and 100 μg for subsequent injections.

In order to purify GhKCH1-specific antibodies from the anti-sera, GST, GST-GhKCH1-N, and GST-GhKCH1-C were coupled to coupling gels using the AminoLink Plus kit (Pierce Chemical) according to manufacturer's instruction. The GST column was used to remove anti-GST antibodies. Specific antibodies were then purified according to a previous report (Lee et al., 2001).

For immunolocalization controls, antibodies were depleted used in corresponding antigens. Fusion proteins of His-GhKCH1-N and His-GhKCH1-C were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The blots were stained with 0.2% Ponceau S in 1% acetic acid to visualize proteins. The fusion protein bands were cut out and blocked by 5% dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Purified antibodies were then incubated with the protein blots for 3 h on a rocker at room temperature. Depleted antibodies were collected and used for control immunolocalization experiments.

Immunoblotting Experiments

Total proteins from cotton fibers was extracted according to our previous report (Preuss et al., 2003). Proteins were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting experiments.

Nitrocellulose blots were blocked with 5% milk in 1× PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Excess milk was washed off with washing solution (0.05% Tween 20, 1× PBS). Blots were incubated in primary antibodies, anti-GhKCH1-N1 and anti-GhKCH1-N2, anti-GhKCH1-C1 and anti-GhKCH1-C2, and DM1A anti-α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis), from 3 h to overnight in a humid chamber at room temperature. Alkaline-phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, AP anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), AP anti-rat IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and AP anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), were then applied for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were developed using the NBT-BCIP solutions (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Actin Cosedimentation Assay

The GST-GhKCH1-N fusion protein (containing the CH domain of GhKCH1) was expressed and purified as described above. This fusion protein was used in an in vitro actin cosedimentation assay (Kovar et al., 2000b). Maize (Zea mays) pollen actin was purified as described previously (Ren et al., 1997; Kovar et al., 2000a). AtFim1 was prepared as previously described (Kovar et al., 2000b). All proteins were preclarified at 140,000g prior to an experiment. Ten micromolar actin microfilaments were prepared by polymerizing G-actin for 16 h at 4°C in F-buffer (5 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm ATP, 100 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2). In a 200-μL reaction volume either 3 μm actin microfilaments alone, 3 μm GHKCH-N1 alone, or actin microfilaments with GhKCH1-N was incubated in F-buffer in the presence of 1.0 mm EGTA (final free calcium concentration was 4.6 nm). After 1 h at 22°C, samples were centrifuged at 200,000g for 1 h in a TL-100 ultracentrifuge (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA) at 4°C. Equal amounts of the resulting pellets and supernatants were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R (Sigma-Aldrich).

The ability of GhKCH1-N to cosediment with actin microfilaments was quantified in a similar fashion as described in detail previously (Kovar et al., 2000a). Either 1.5 μm AtFim1 with 3.0 μm actin microfilaments, or 1.5 μm GHKCH-N1 with 3.0 μm actin microfilaments, were incubated in F-buffer for 1 h at 22°C. After 80 μL was removed and added to 20 μL of 5× protein sample buffer (total protein; T), the remaining 120 μL was centrifuged for 1 h at 200,000g as described above. Supernatant (80 μL) was removed and added to 20 μL 5× protein sample buffer. The remaining supernatant was removed and the pellets were resuspended in 50 μL 2× protein sample buffer. Equal amounts of total protein, supernatant, and pellet were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R. Gels were scanned, and the intensity of the bands was determined with IMAGEQUANT software (Personal Densitometer, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The percentage of AtFim1 or GHKCH-N1 in the pellet = [(GhKCH1-NP/GhKCH1-NT) + (1 − GhKCH1-NS/GhKCH1-NT)]/2, where T, S, and P refer to the determined intensity of the GhKCH1-N (or AtFim1) in the total, supernatant, and pellet fractions, respectively.

Immunolocalization

Primary antibodies used in immunolocalization were anti-GhKCH1-N1, anti-GhKCH1-N2, anti-GhKCH1-C1, anti-GhKCH1-C2, DM1A, and 3H11 anti-actin (a generous gift from Dr. Richard Cyr at Pennsylvania State University; Andersland et al., 1994). Secondary antibodies were FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat (Sigma-Aldrich), and Texas Red X-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Mitochondria were labeled with MitoTracker Red (Molecular Probes).

Immunolocalization in whole fibers and cytoplasts were carried out according to our previous report (Preuss et al., 2003). Cytoplasts were treated with 0.5 μm Latrunculin A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min to depolymerize actin microfilaments prior to fixation. All samples were observed on an Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with epifluorescence optics. Images were acquired with a CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonic Systems, Bridgewater, NJ) using the ImageProPlus 4.0 software package (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Images were assembled into figure plates using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

The cDNA sequence of GhKCH1 is deposited with the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession number AY695833.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Division of Energy Biosciences (grants to B.L., D.P.D., and C.J.S.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.104.052340.

References

- Andersland JM, Dixon DC, Seagull RW, Triplett BA (1998) Isolation and characterization of cytoskeletons from cotton fiber cytoplasts. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 34: 173–180 [Google Scholar]

- Andersland JM, Fisher DD, Wymer CL, Cyr RJ, Parthasarathy MV (1994) Characterization of a monoclonal antibody prepared against plant actin. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 29: 339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr RJ, Palevitz BA (1995) Organization of cortical microtubules in plant cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol 7: 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12: 13–15 [Google Scholar]

- Endow SA (1999) Determinants of molecular motor directionality. Nat Cell Biol 1: E163–E167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattoum A, Roustan C, Smyczynski C, Der Terrossian E, Kassab R (2003) Mapping the microtubule binding regions of calponin. Biochemistry 42: 1274–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimona M, Djinovic-Carugo K, Kranewitter WJ, Winder SJ (2002) Functional plasticity of CH domains. FEBS Lett 513: 98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimona M, Winder SJ (1998) Single calponin homology domains are not actin-binding domains. Curr Biol 8: R674–R675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode BL, Drubin DG, Barnes G (2000) Functional cooperation between the microtubule and actin cytoskeletons. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Dixon JE (1991) Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal Biochem 192: 262–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi H, Orii H, Mori H, Shimmen T, Sonobe S (2000) Isolation of a novel 190 kDa protein from tobacco BY-2 cells: possible involvement in the interaction between actin filaments and microtubules. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 920–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai S, Ishiji A, Mabuchi I, Sutoh K (2004) A novel actin-bundling kinesin-related protein from Dictyostelium discoideum. J Biol Chem 279: 4696–4704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Triplett BA (2001) Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro: models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol 127: 1361–1366 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MG, Shi W, Ramagopal U, Tseng Y, Wirtz D, Kovar DR, Staiger CJ, Almo SC (2004) Structure of the actin crosslinking core of fimbrin. Structure 12: 999–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloth RH (1989) Changes in the level of tubulin subunits during development of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber. Physiol Plant 76: 37–41 [Google Scholar]

- Korenbaum E, Rivero F (2002) Calponin homology domains at a glance. J Cell Sci 115: 3543–3545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Drobak BK, Staiger CJ (2000. a) Maize profilin isoforms are functionally distinct. Plant Cell 12: 583–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Staiger CJ, Weaver EA, McCurdy DW (2000. b) AtFim1 is an actin filament crosslinking protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 24: 625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama R, Gustus C, Terada Y, Uetake Y, Matuliene J (2002) CHO1, a mammalian kinesin-like protein, interacts with F-actin and is involved in the terminal phase of cytokinesis. J Cell Biol 156: 783–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-RJ, Giang HM, Liu B (2001) A novel plant kinesin-related protein specifically associates with the phragmoplast organelles. Plant Cell 13: 2427–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J (1991) Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252: 1162–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuliene J, Kuriyama R (2002) Kinesin-like protein CHO1 is required for the formation of midbody matrix and the completion of cytokinesis in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 13: 1832–1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuliene J, Kuriyama R (2004) Role of the midbody matrix in cytokinesis: RNAi and genetic rescue analysis of the mammalian motor protein CHO1. Mol Biol Cell 15: 3083–3094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy DW, Kim M (1998) Molecular cloning of a novel fimbrin-like cDNA from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 36: 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nislow C, Lombillo VA, Kuriyama R, McIntosh JR (1992) A plus-end-directed motor enzyme that moves antiparallel microtubules in vitro localizes to the interzone of mitotic spindles. Nature 359: 543–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss ML, Delmer DP, Liu B (2003) The cotton kinesin-like calmodulin-binding protein associates with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol 132: 154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ASN, Day IS (2001) Kinesins in the Arabidopsis genome: a comparative analysis among eukaryotes. BMC Genomics 2: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Gibbon BC, Ashworth SL, Sherman DM, Yuan M, Staiger CJ (1997) Actin purified from maize pollen functions in living plant cells. Plant Cell 9: 1445–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge RW (1988) Freeze-substitution improves the ultrastructural preservation of legume root hairs. Bot Mag Tokyo 101: 427–441 [Google Scholar]

- Seagull RW (1990) The effects of microtubule and microfilament disrupting agents on cytoskeletal arrays and wall deposition in developing cotton fibers. Protoplasma 159: 44–59 [Google Scholar]

- Seagull RW (1992) A quantitative electron microscopic study of changes in microtubule arrays and wall microfibril orientation during in vitro cotton fiber development. J Cell Sci 101: 561–577 [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SL, Kamyar R, Ehrhardt DW (2003) Sustained microtubule treadmilling in Arabidopsis cortical arrays. Science 300: 1715–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Nakatani K, Mitsui H, Ohashi Y, Takahashi H (1999) Characterization of katD, a kinesin-like protein gene specifically expressed in floral tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 230: 23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SC, Wilkins TA (1995) Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) seed trichomes expand via diffuse growing mechanism. Can J Bot 73: 746–757 [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO, Galway ME (2003) Remodeling the cytoskeleton for growth and form: an overview with some new views. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54: 691–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]