Significance

The trace element selenium is essential for human health and is required in a narrow dietary concentration range. Insufficient selenium intake has been estimated to affect up to 1 billion people worldwide. Dietary selenium availability is controlled by soil–plant interactions, but the mechanisms governing its broad-scale soil distributions are largely unknown. Using data-mining techniques, we modeled recent (1980–1999) distributions and identified climate–soil interactions as main controlling factors. Furthermore, using moderate climate change projections, we predicted future (2080–2099) soil selenium losses from 58% of modeled areas (mean loss = 8.4%). Predicted losses from croplands were even higher, with 66% of croplands predicted to lose 8.7% selenium. These losses could increase the worldwide prevalence of selenium deficiency.

Keywords: selenium, soils, global distribution, prediction, climate change

Abstract

Deficiencies of micronutrients, including essential trace elements, affect up to 3 billion people worldwide. The dietary availability of trace elements is determined largely by their soil concentrations. Until now, the mechanisms governing soil concentrations have been evaluated in small-scale studies, which identify soil physicochemical properties as governing variables. However, global concentrations of trace elements and the factors controlling their distributions are virtually unknown. We used 33,241 soil data points to model recent (1980–1999) global distributions of Selenium (Se), an essential trace element that is required for humans. Worldwide, up to one in seven people have been estimated to have low dietary Se intake. Contrary to small-scale studies, soil Se concentrations were dominated by climate–soil interactions. Using moderate climate-change scenarios for 2080–2099, we predicted that changes in climate and soil organic carbon content will lead to overall decreased soil Se concentrations, particularly in agricultural areas; these decreases could increase the prevalence of Se deficiency. The importance of climate–soil interactions to Se distributions suggests that other trace elements with similar retention mechanisms will be similarly affected by climate change.

Micronutrients are essential for maintaining human health, and although they are needed in only trace amounts, deficiencies reportedly affect 3 billion people worldwide (1, 2). One such micronutrient is selenium. Inadequate dietary Se intake affects up to 1 in 7 people and is also known to affect livestock health adversely (3, 4). Because dietary Se intake depends largely on Se content in soil and bioavailability to crops (5–7), understanding the mechanisms driving soil concentrations and predicting global distributions could help prevent Se deficiency (8). However, global soil Se concentrations and the factors affecting Se distributions are largely unknown (9). Apart from soils, Se is present in all other environmental compartments [i.e., the lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and atmosphere (9)], which all play a role in global Se biogeochemical cycling and distribution (7, 10).

The factors driving soil Se concentrations [e.g., increased sorption with decreased pH and soil reduction potential (Eh) and increased clay and soil organic carbon (SOC) content; Table S1 and refs. 7 and 11 for a review of the previously reported drivers of soil Se] have been evaluated primarily through small-scale experimentation (e.g., soil columns; see ref. 12); however, broad-scale distributions cannot be inferred from such studies. For example, soils in small-scale experiments are often manipulated [e.g., by carbon amendments (12)] to achieve desired conditions, obscuring the natural processes that may influence Se retention capacity. Additionally, climate variables, which likely affect soil Se concentrations directly as a source (e.g., deposition; see refs. 8 and 13) or indirectly by affecting soil retention of Se (e.g., sorption), are ignored in small-scale experiments. Therefore, to predict the global distributions, broad-scale analyses of soil Se drivers are essential.

Table S1.

Predictor variables used to summarize mechanisms governing soil Se concentrations

| Variable | Resolution | Reference | Rationale |

| Climate | |||

| Average daily precipitation | 2.5° | (30) | Precipitation can affect soil Se directly (e.g., wet deposition or leaching) or indirectly by affecting soil pH, SOC, or Eh. Arid environments (high AI values) are characterized by high soil pH, low SOC, and oxidizing soils, which reduce soil Se concentrations. Se uptake in plants is positively affected by transpiration, which could decrease soil Se. Conversely, increases in evaporation could increase soil Se by concentrating Se (and other compounds) on the land surface. Leaching occurs when ET << precipitation (i.e., EI << 1). Therefore, ET affects Se concentrations by controlling leaching. PET, temperature, and net radiation are measures of system energetics. Increased energy in soils likely increases plant/microbial respiration (when water is available); increased respiration likely increases Se uptake and/or volatilization in plants and microbes. Conversely, increasing energetics likely increases leaching by increasing Eh, which decreases Se partitioning (6–13). |

| AI | 2.5° | (30) | |

| Average ET | 2.5° | (30) | |

| EI | 2.5° | (30) | |

| Average daily PET | 2.5° | (30) | |

| Average daily air temperature | 2.5° | (30) | |

| Average monthly net radiation | 0.5° | (31) | |

| Soil | |||

| Cation exchange capacity (CEC) | 0.25 km2 | (32) | Soil physicochemical properties affect Se partitioning to soils. Partitioning of anionic Se is known to increase with CEC, likely because of the double-layer theory. Partitioning is known to increase at lower pH, higher clay content, and higher SOC. Other factors (e.g., sesquioxide partitioning) are known to affect soil Se retention, but global data for many datasets do not yet exist. Se is a redox-sensitive element; therefore, soil water can affect speciation and thus control leaching. Microbial activity can affect soil Se retention by affecting redox state and pH (and thus partitioning), precipitating Se, or producing volatile species. Runoff and sedimentation could potentially reduce soil Se concentrations upslope and subsequently deposit Se down-slope. Irrigation could increase soil Se by pumping Se-rich water to the surface (6–13). |

| pH | 0.25 km2 | (32) | |

| % Sand/silt/clay | 0.25 km2 | (32) | |

| Bulk density | 0.25 km2 | (32) | |

| SOC | 1.0° | (33) | |

| Soil water stress | 1 km2 | (34) | |

| Irrigation | 1 km2 | (35) | |

| Runoff/soil erosion | 2.5°/2.0° 9 km2 | (36, 37) | |

| Other | |||

| Soil taxonomy-WRB/USDA | 1° | (32) | Soil classes share similar characteristics that might govern soil concentrations. Similarly, specific geologic types (e.g., organic-rich sedimentary rocks) share characteristics that might control soil Se concentrations. Furthermore, the depth to bedrock could affect soil concentrations. Land use (e.g., agriculture) has differential effects on soil physicochemical properties and could drive concentrations up or down. Plants take up Se from soils, which could limit Se concentrations in soils. Global industrial emissions data are nonexistent for Se, so population density was used as a proxy to estimate emissions (6–13). |

| Lithology | 0.5° | (38) | |

| Land use | 300 m2 | (39) | |

| Bedrock depth | 0.25 km2 | (32) | |

| Vegetation cover/canopy height | 1 km2 | (40, 41) | |

| Population density | 1 km2 | (42) | |

All variables were evaluated; those retained for modeling are in italic type. USDA, US Department of Agriculture; WRB, World Record Base for Soils.

Here we report on the influence of soil and climate variables on worldwide Se distributions in soils 0–30 cm deep. Our objectives were (i) to test hypothesized drivers of soil Se concentrations, (ii) to predict global soil Se concentrations quantitatively, and (iii) to quantify potential changes in soil Se concentrations resulting from climate change. To achieve these objectives, several regional- to continental-scale datasets reporting total soil Se concentrations [n = 33,241 data points (5, 14–29); SI Materials and Methods for dataset details] and 26 environmental variables describing climate, soil physicochemical properties, irrigation, water stress, erosion, runoff, land use, soil type, lithology, bedrock depth, vegetation/canopy characteristics, and population density (30–42) (Table S1 for details of variables) were assessed to make global predictions of soil Se concentrations for recent (1980–1999) and future (2080–2099) periods. Predictions were made using three machine-learning tools: one randomForest (RF) model and two artificial neural network models, herein referred to as “predictive models.” Additionally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate potential mechanisms independently and to quantify complex interactions between Se and the relevant predictor variables.

Results and Discussion

After variable selection, seven variables were retained and were considered the most important factors controlling soil Se concentrations: the aridity index (AI, unitless) [i.e., the ratio of potential evapotranspiration (PET, mm/d) to precipitation (mm/d)]; clay content (%); evapotranspiration (ET, mm/d); lithology; pH; precipitation (mm/d); and SOC (0–30 cm depth, tons of C/ha). With these variables, the accuracy of the predictive model was high (average R2 = 0.67, average cross-validation R2 = 0.49, n = 1,000 iterations for each model) (Fig. S1), and the precision was high [based on a low SD of the modeled prediction (0.032 mg Se/kg) relative to the mean (0.35 mg Se/kg)] (Fig. S2). For the SEM analysis, both the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) (0.043) and the comparative fit index (CFI) (0.962) indicated a good fit between the observed and modeled data (43). All variables retained within the SEM analysis were statistically significant (i.e., P < 0.05) (Fig. S3), and, based on the predictive model sensitivity analyses and the SEM regression weights, the modeling results corroborated each other strongly (see following section), suggesting that processes driving soil Se concentrations were described accurately. Because the data were averaged on a 1° scale, this modeling approach likely captures the broad-scale mechanisms but potentially misses important local-scale factors.

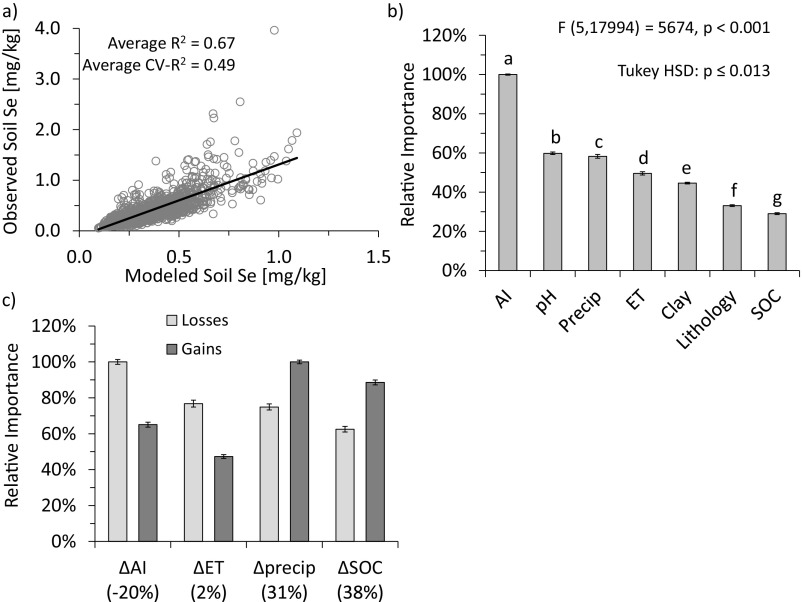

Fig. S1.

Performance and variable importance of the predictive models. (A) Scatter plot of the observed and predicted soil Se concentrations (n = 1,642) based on the predictive models including the average training and cross-validation (CV) performance (n = 1,000 iterations per model). (B) The average variable importance for the recent (1980–1999) predictions was calculated for each model iteration (n = 1,000) for all three predictive models. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine that the mean importance of the variables were statistically different (statistical values are given in the figure). The Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test was used to determine that all variables were statistically different from all others at α = 0.05 (differences are indicated by different letters; P ≤ 0.013 for all variables). (C) Predicted losses and gains in soil Se were modeled between 1980–1999 and 2080–2099 based on changes in climate variables and SOC. The percentages below the variables indicate the average percentage change in each variable for all modeled pixels. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

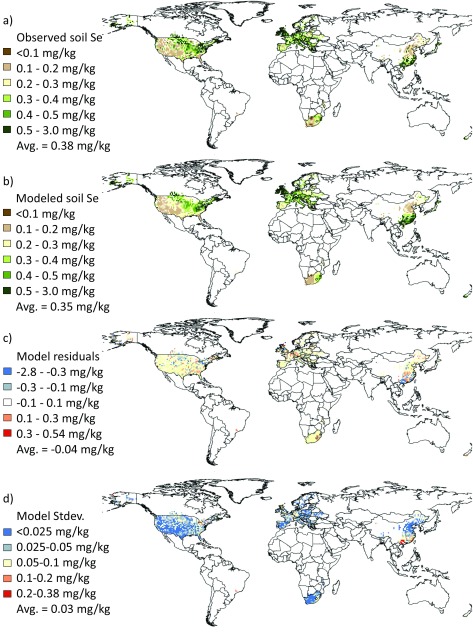

Fig. S2.

Geographical representation of the predictive modeling. Maps illustrate the observed soil Se concentrations (A), modeled soil Se concentrations in known areas (B), averaged residuals (modeled − observed) of the predictive models (C), and SD of the global soil Se predictions (D). Pixels depict the average of the predictive models. The pixel resolution is 1° (n = 1,642).

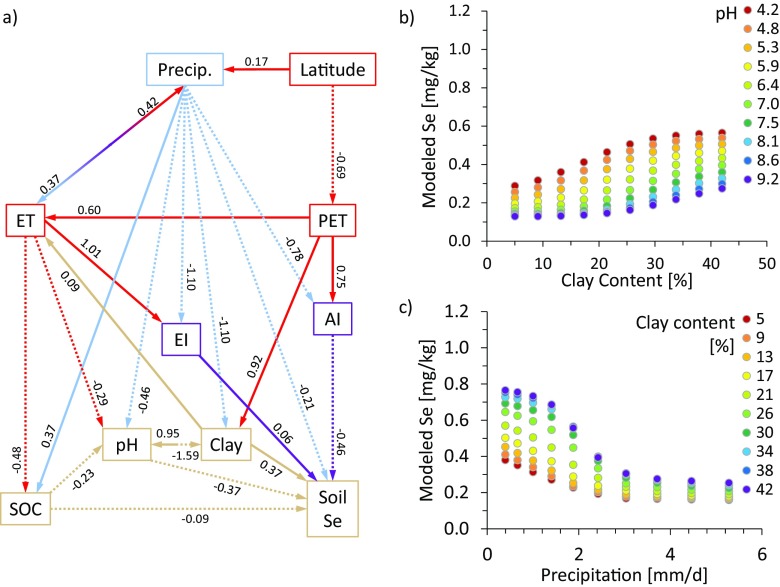

Fig. S3.

Multivariate interactions between predictor variables and soil Se. (A) An hypothesized model of the variables controlling soil Se concentrations was tested using SEM. All aggregated soil Se data points (n = 1,642) were used in the model. The solid lines indicate positive direct relationships and dotted lines indicate negative direct relationships between variables. Variables and lines colored red, blue, purple, and tan correspond to energy, precipitation, energy:precipitation ratios, and soil parameters, respectively. Standardized indirect effects and total effects can be found in Table S2. (B and C) Bivariate interactions between clay content and pH (B) and between precipitation and clay content (C) are illustrated. In bivariate analyses, parameters were allowed to vary between the minimum and maximum observed value with all other variables held constant at the observed mean value of the entire dataset (n = 1,642).

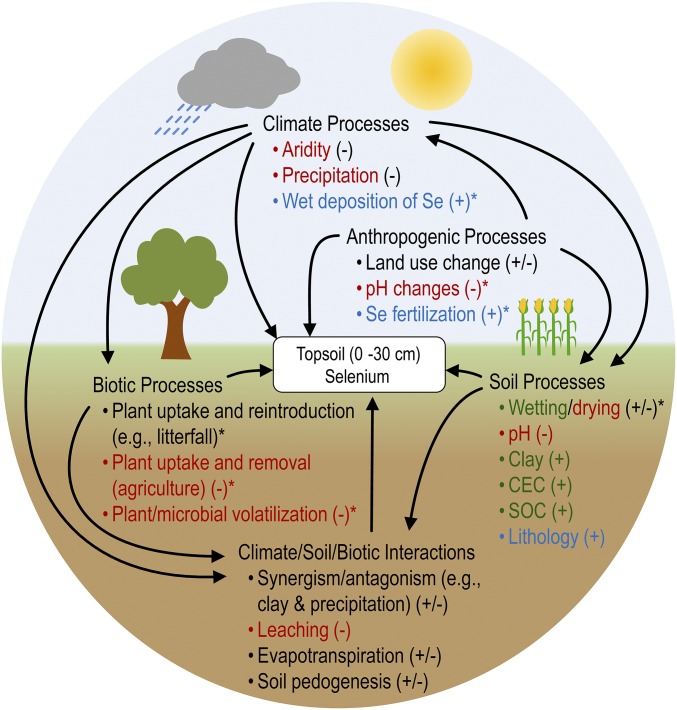

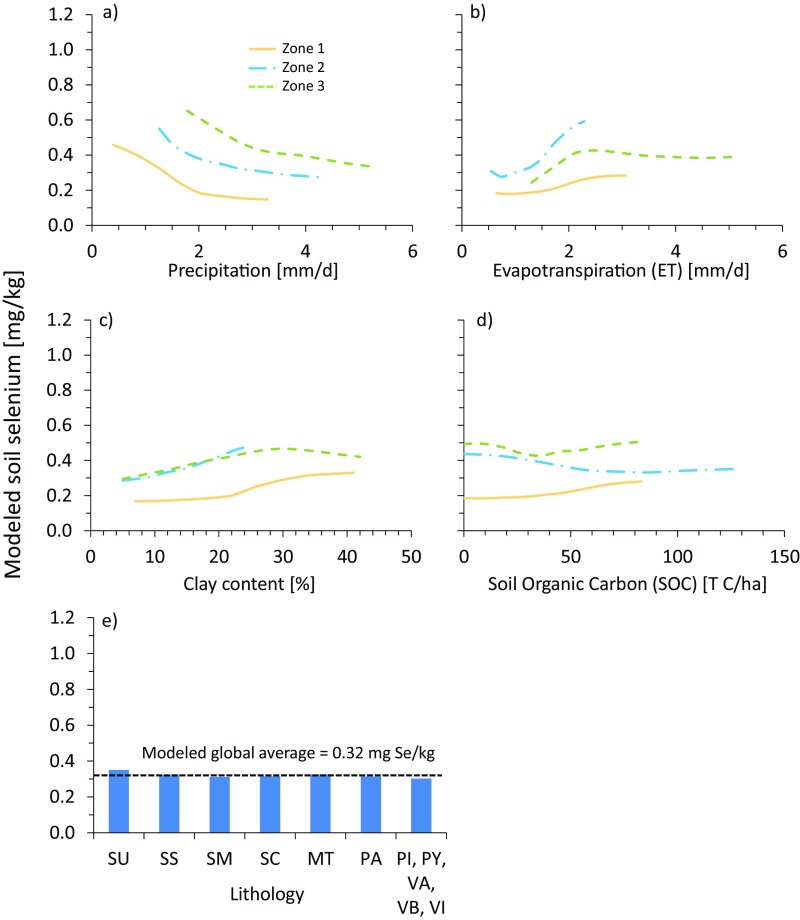

Soil Se concentrations were determined largely by interactions between climate and soil variables (Figs. 1 and 2, Figs. S1, S3, and S4, and Table S2). In the SEM, AI and precipitation had the greatest direct and indirect effect, respectively, on soil Se concentrations (Table S2). Based on averaged relative importance from the predictive models (Fig. S1), AI was the most important predictor (100 ± 0.3%) followed by pH (60 ± 0.7%), precipitation (58 ± 1%), ET (50 ± 0.8%), clay content (45 ± 0.4%), lithology (33 ± 0.5%), and SOC (29 ± 0.5%). Sensitivity analyses were performed on these variables to determine if the mechanisms driving soil Se concentrations changed in different zones represented by different environmental conditions (SI Materials and Methods for a description). The soil Se patterns were similar between different zones, suggesting that Se drivers were consistent regardless of the environment (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). This result suggests that the models can be used to predict soil Se concentrations in other regions of the world. In sensitivity analyses, soil Se increased with increases in clay content and with decreases in soil pH (Fig. 2 and Figs. S3 and S4), both of which are known to increase soil Se sorption (7, 44). Although soil Se is known to partition/complex with organic matter (7), soil Se was affected only weakly by changes in SOC (Figs. S1, S3, and S4 and Table S2). Furthermore, changes in lithological classes resulted in negligible changes in soil Se when other variables were held constant (Fig. S4). Although lithology was of minor importance in this study, we recognize that it can influence soil Se concentrations at local scales (45).

Fig. 1.

Summary of the processes governing soil Se concentrations. Dominant processes (and bulleted examples) governing soil Se concentrations are indicated. Text colored in red, green, and blue indicates processes affecting soil Se losses, retention, and sources/supplies, respectively. Factors responsible for increases (+) and/or decreases (−) in soil Se as well as processes not explicitly examined in our analysis (*) are indicated.

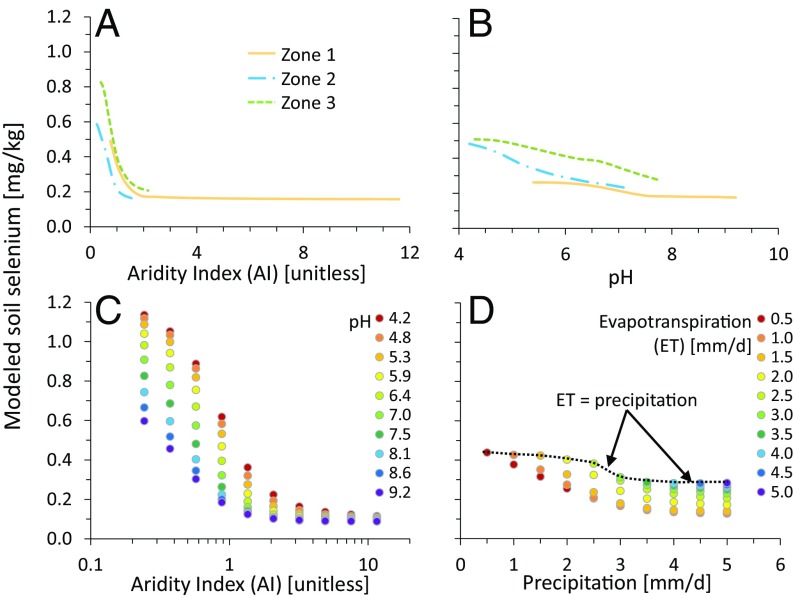

Fig. 2.

Univariate and bivariate sensitivity analyses of the predictive models. (A and B) The independent effects of AI (A) and precipitation (B) were modeled by holding all other variables constant at the zonal averages as defined by the two-step clustering. (C and D) Similarly, bivariate interactions between AI and clay (C) and between precipitation and ET (D) are illustrated. These parameters were allowed to vary between the minimum and maximum observed value while all other variables were held constant at the mean value of the entire dataset (n = 1,642). The dotted line in D indicates the conditions in which ET = precipitation. Other bivariate interactions are presented in Fig. S3.

Fig. S4.

Univariate sensitivity analyses of predictive models for (A) precipitation, (B) evapotranspiration, (C) clay content, (D) soil organic carbon, and (E) lithology. MT, metamorphic rocks; PA, acid plutonic rocks; PI, intermediate plutonic rocks; PY, pyroclastics; SC, carbonate sedimentary rocks; SM, mixed sedimentary rocks; SS, siliciclastic sedimentary rocks; SU, unconsolidated sediments; VA, acid volcanic rocks; VB, basic volcanic rocks; VI, intermediate volcanic rocks. Zones 1–3 correspond to those defined in Fig. S5.

Table S2.

Standardized regression coefficients from the SEM output

| Variable | Latitude | PET | SOC | Clay | pH | Precipitation | ET | EI | AI |

| Standardized total effects | |||||||||

| PET | −0.69 | ||||||||

| SOC | 0.21 | −0.24 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.24 | −0.38 | ||

| Clay | −0.31 | 0.43 | 0.15 | −0.60 | −0.64 | −0.06 | 0.09 | ||

| pH | −0.20 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.36 | −0.58 | −0.78 | −0.40 | ||

| Precipitation | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.18 | 0.50 | ||

| ET | −0.45 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.44 | 0.20 | ||

| EI | −0.44 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.86 | 0.66 | ||

| AI | −0.50 | 0.51 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.92 | −0.39 | ||

| Se | 0.17 | −0.15 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.39 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.06 | −0.50 |

| Standardized direct effects | |||||||||

| PET | −0.69 | ||||||||

| SOC | 0.37 | −0.48 | |||||||

| Clay | 0.92 | −1.59 | −1.10 | ||||||

| pH | −0.23 | 0.95 | −0.46 | −0.30 | |||||

| Precipitation | 0.17 | 0.42 | |||||||

| ET | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.37 | ||||||

| EI | −1.10 | 1.01 | |||||||

| AI | 0.75 | −0.78 | |||||||

| Se | −0.09 | 0.36 | −0.37 | −0.19 | 0.06 | −0.50 | |||

| Standardized indirect effects | |||||||||

| PET | |||||||||

| SOC | 0.21 | −0.24 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.09 | ||

| Clay | −0.31 | −0.50 | 0.15 | −0.60 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.09 | ||

| pH | −0.20 | 0.09 | 0.13 | −0.59 | −0.58 | −0.32 | −0.11 | ||

| Precipitation | −0.19 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.18 | 0.08 | ||

| ET | −0.45 | 0.16 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.20 | ||

| EI | −0.44 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.24 | −0.35 | ||

| AI | −0.50 | −0.25 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.39 | ||

| Se | 0.17 | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.34 | −0.03 | 0.61 | 0.36 | ||

The total effect is the sum of the direct and indirect effects. Standardized coefficients refer to how many SDs a dependent variable (rows) will change, per SD increase in the predictor variable (columns). All aggregated soil Se data points (n = 1,642) were used in the model. The SEM conceptual model is presented in Fig. S3.

Climate Effects on Soil Se.

Climate variables (i.e., AI, precipitation, and ET) were dominant factors driving soil Se concentrations, likely because they control leaching from soils, and observed patterns within the sensitivity and SEM analyses for all climate variables are consistent with this hypothesis. High precipitation and AI negatively affected soil Se concentrations, whereas ET positively affected soil Se concentrations (Fig. 2, Figs. S3 and S4, and Table S2). Although AI (i.e., the ratio of PET to precipitation) and precipitation are inversely related, both variables exerted negative effects on soil Se, suggesting that separate mechanisms drive these patterns. Although precipitation increases the transport of dissolved Se species in soil solution by increasing vadose zone flow, AI likely affects leaching by controlling soil redox conditions and thus Se speciation, sorption, and mobility. It has been reported that as AI increases (i.e., PET increases relative to precipitation), soils become drier (46), resulting in more oxidizing soil conditions (47). Oxidized Se species (e.g., oxyanions) are more soluble and mobile than reduced species (e.g., selenides) (7, 11, 12, 48). Therefore, soil drying likely increases the presence of oxidized/mobile soil Se species, which can be leached during subsequent rain events.

Soil drying likely increases Se mobility but also can reduce soil Se transport (although these processes likely occur at different time scales). Leaching is driven by the ratio of ET to precipitation (also known as the “evaporative index,” EI) (49). As previously mentioned, precipitation increases the transport of Se through the vadose zone, but as ET increases relative to precipitation, more moisture is removed from the soil column. This removal of moisture reduces the vadose zone flow, which in turn reduces Se mass transport. In theory, when ET and precipitation are equal, leaching should be negligible. Although ET clearly dampens the negative effects of precipitation in bivariate sensitivity analyses, a negative relationship existed between precipitation and modeled Se despite an ET:precipitation ratio of 1 (Fig. 2). This trend potentially could be explained by plant Se uptake, which has been reported to increase with ET (6). Therefore, in addition to its positive indirect effect by reducing leaching, ET also may have a direct negative effect on soil Se by increasing plant uptake. This direct negative effect was observed in the SEM analysis, but the relationship was not statistically significant and therefore was removed. Although this negative effect may exist, it appears to be less important than the role ET plays in reducing Se leaching. Given the importance of climate variables in governing soil Se concentrations, the observed patterns between AI, precipitation, ET, and modeled soil Se concentrations strongly suggest that changes in climate will result in changes in soil Se concentrations in time and space.

Climate–Soil Interactions and Soil Se.

Although the direct effects of precipitation (i.e., leaching) were moderate, its indirect effects (i.e., those mediated through other variables) were approximately threefold larger (Table S2). Precipitation is known to affect soil formation (i.e., pedogenesis), and in our analyses it strongly affected AI, pH, ET, and clay content, which subsequently affect soil Se retention (Fig. S3 and Table S2). Although there was a negative direct effect between precipitation and soil Se, the sum of direct and indirect effects resulted in precipitation having a net positive effect (Table S2). Thus it is important to examine both direct and indirect effects, because interpreting only total effects can lead to erroneous conclusions about the mechanisms driving spatial patterns.

In bivariate sensitivity analyses, both synergistic and antagonistic interactions were observed and were strongest between aridity, precipitation, clay content, and pH. In univariate sensitivity analyses, when all other variables were held constant, modeled soil Se concentrations were highest under low AI (0.83 mg Se/kg), low precipitation (0.65 mg Se/kg), low pH (0.51 mg Se/kg), and relatively high clay content (0.47 mg Se/kg) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4). It is important to note that, as long as PET is sufficiently low, environments with low precipitation can have low AI values also. Furthermore, sensitivity and SEM analyses suggest that the direct (i.e., nonmediated) effect of precipitation drives Se leaching from soils (Fig. 2 and Figs. S3 and S4), thus explaining why low values resulted in high soil Se, even though the net effect is positive (Table S2). In bivariate sensitivity analyses, soil Se concentrations exceeded these values when low AI was modeled with low pH (1.12 mg Se/kg), when low precipitation was modeled with high clay content (0.86 mg Se/kg), and when high clay content was modeled with low pH (0.56 mg Se/kg) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3). Although Se concentrations were typically enhanced in low-AI or low-precipitation environments, both variables could suppress the effects of other variables in high-AI or high-precipitation environments (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3). These results demonstrate the dependence of soil Se concentrations on soil–climate interactions. Based on these analyses, low-Se soils are most likely to occur in arid environments and in areas with high pH and low clay content. Conversely, areas with low to moderate precipitation but relatively low aridity (e.g., cool and moist climates) and high clay content are likely to have higher soil Se concentrations.

Predicted Global Soil Se Distributions.

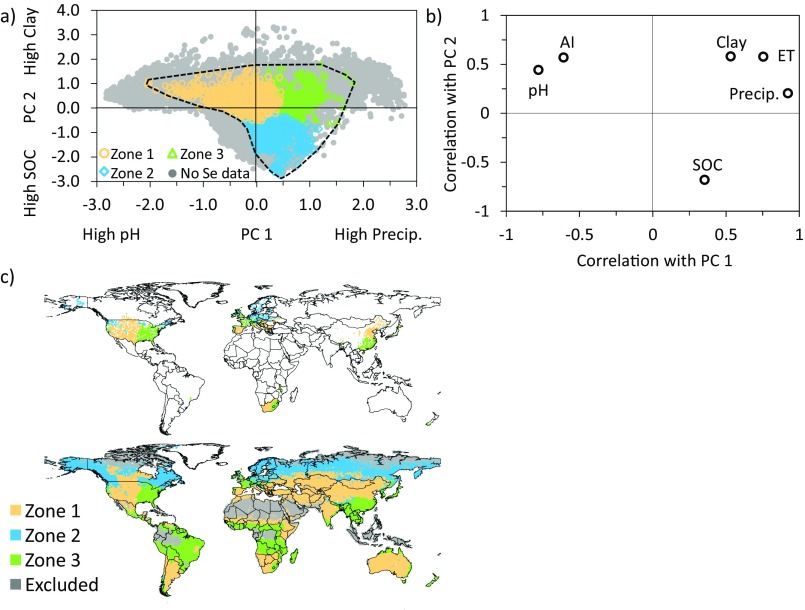

Global predictions were made using models trained largely using temperate/midlatitude datasets (Fig. S2). Although the available data adequately described similar regions, data from tropical, extremely arid, and polar regions were almost entirely absent (to the best of our knowledge, no broad-scale soil geochemical surveys are available from these regions). As a result, predictions that were made for environments that fell outside our dataset’s domain were excluded (Fig. S5). Therefore, Se predictions for 1980–1999 were retained for only 70% of land surfaces. The majority of croplands and rangelands, which are areas of primary interest, given that soil Se concentrations and bioavailability in these regions largely drive the Se status in humans and livestock, fall largely within the retained areas.

Fig. S5.

Multivariate and geographic distributions of the three zones generalizing the soil and climate properties of the 1,642 aggregated data points following two-step clustering. (A) Scatter plot of PCs 1 and 2. Together PCs 1 and 2 account for 75.1% of the variability (46.8% and 28.3%, respectively) within the entire dataset. The variables with the greatest correlation are included along the axis. A polygon was drawn around this distribution, and if the points fell outside this polygon, the predictions were excluded. (B) Correlation matrix between both PCs and each continuous predictor variable. (C) The geographic distribution of each zone for known areas (Upper) and global areas (Lower) and the pixels that were excluded from the analysis (i.e., the pixels outside the polygon in A.

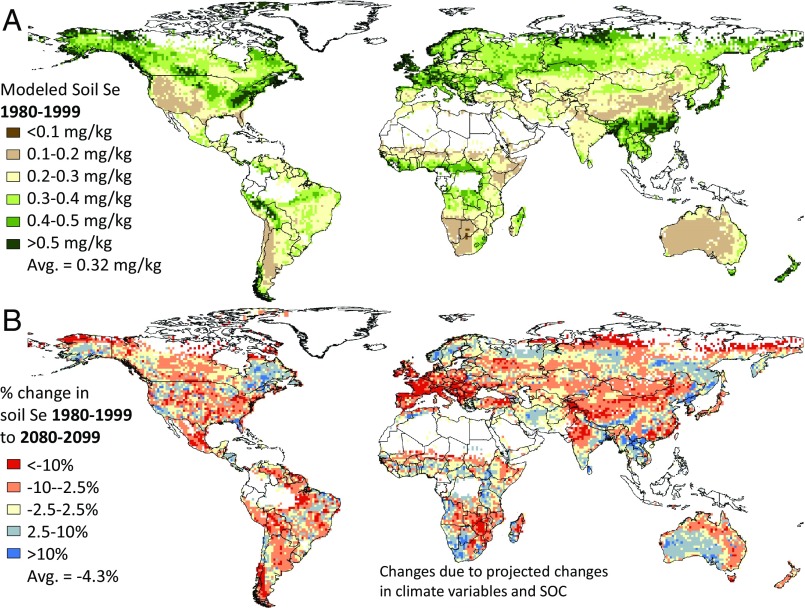

Based on predictive models, the global mean soil Se concentration for 1980–1999 was 0.322 ± 0.002 mg Se/kg (Fig. 3), similar to reported values (mean = 0.4 mg Se/kg; typical range 0.01–2 mg Se/kg) (50). Using this estimate, ∼13.1 million metric tons of Se are stored in the top 30 cm of soil within the predicted area [i.e., ∼70% of world’s land surface (1.04 × 107 km2); SI Materials and Methods for the calculation]. Compared with other regions, predicted soil Se concentrations were generally higher (typically >0.2 mg Se/kg) (Fig. 3) in temperate and northern latitudes. In wet equatorial regions, concentrations were typically 0.3–0.5 mg Se/kg. Relatively low-Se soils (<0.2 mg Se/kg) were predicted for 15% of modeled areas and were restricted primarily to arid and semiarid regions in Argentina, Australia, Chile, China, southern Africa, and the southwestern United States. In some of these countries, low Se content in crops and livestock has been reported (3), but it is important to note that many factors contribute to low Se content in plants (e.g., plant uptake pathways, soil Se speciation, and the abundance of competing ions such as sulfate) (7).

Fig. 3.

Geographical representation of the predictive modeling on a 1° scale. Maps illustrate the modeled soil Se concentrations (1980–1999) (A) and percentage change in soil Se concentrations between recent and future (2080–2099) conditions (B) as a function of projected changes in climate (RCP6.0 scenario) and SOC content (ECHAM5-A1B scenario). Predictions represent the average of the predictive models and were based on the AI, soil clay content, ET, lithology, pH, precipitation, and SOC.

Over- and Underpredictions of the Model.

In an attempt to identify potential missing variables, we examined the residuals of the predictive models. Spatial patterns of any missing variable should match those of the residuals (Fig. S2). Overall, the models underpredicted soil Se concentrations (average residual = −0.036 ± 0.009 mg Se/kg), suggesting that Se sources may be missing from the model. On a localized level, soil Se concentrations appear to be underpredicted in regions adjacent to regions of high marine productivity (e.g., western Alaska, western Ireland, western Norway, western England, and Wales) (Fig. S2) (51). Marine environments are thought to increase soil Se concentrations via wet deposition (10, 13), and atmospheric deposition of Se thus could explain some of the model’s underprediction. However, global spatial data do not exist for Se deposition and thus could not be analyzed. We included population density as a potential proxy for anthropogenic emissions, but this was one of the least important variables in the variable selection procedure. We evaluated a wide variety of qualitative factors [e.g., specific agricultural soil types (e.g., paddy soils), specific sedimentary depositional environments (e.g., glacial deposits), coal power plants, carbonaceous shale deposits, and others] that may affect soil Se distributions; however, we found no consistent discernable link between these variables and the broad-scale distribution of the model residuals.

Despite the underprediction, overall patterns of modeled soil Se distribution match the actual distribution quite closely (Fig. S2), and 71% of predicted values were within ±0.05 mg Se/kg of the observed value, indicating that a majority of the predicted data were relatively accurate. Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis and SEM trends closely match hypothesized mechanisms governing soil Se concentrations reported in the literature (Fig. 2 and Figs. S3 and S4). This finding suggests that the models are largely accurate and capture the dominant processes controlling broad-scale Se distributions. Nevertheless, future studies could include additional predictor variables, especially those that are currently unavailable, to provide better estimates of broad-scale soil Se. Furthermore, to overcome some of this study’s limitations, predictions could be made on more local/regional scales using higher resolution data.

Modeled Losses of Future Soil Se.

The interactions between precipitation and other soil/climate variables strongly suggest that climate changes could drive changes in soil Se concentrations. To assess the influence of changes in climate and SOC, soil Se was modeled for 2080–2099 using moderate climate change scenarios [Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 6.0 for precipitation, AI, and ET (52) and European Centre/Hamburg Model (ECHAM) 5-A1B for SOC (33)]. Other climate scenarios (e.g., RCP 8.5) were not used because SOC data were available only for A1B scenarios, which are most similar to RCP 6.0.

Future predictions were made for the entire globe, but, based on the filtering criteria used (SI Materials and Methods), predictions were retained for ∼48% of the global land area. Based on these pixels alone, soil Se concentrations were predicted to drop by 4.3% on average, from 0.331 ± 0.003 mg Se/kg in 1980–1999 to 0.316 ± 0.002 mg Se/kg in 2080–2099, as a result of changes in climate and SOC concentrations (Fig. 3). For soil at a depth of 0–30 cm, this loss corresponds to ∼403,763 tons of Se over 100 y, or 4,037.6 tons of Se lost per year (SI Materials and Methods for the calculation), an amount that is ∼20–30% of the total estimated Se mass that is cycled yearly through the troposphere [i.e., 13,000–19,000 tons (assumed to be metric tons)/y (10)], although our estimate is only for 48% of the land surface. Our modeling approach is not a mass balance model, so Se fate could not be investigated. Nonetheless, changes in Se concentrations in other environmental compartments are known from the past. For example, marine Se concentrations throughout various periods of the Phanerozoic eon have been 1.5–2 orders of magnitude lower than current oceanic concentrations (53).

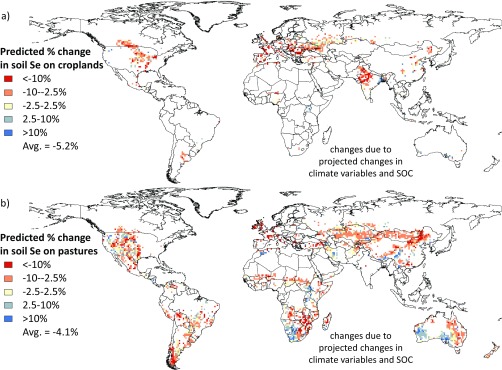

Based on areas with future predictions (7.19 × 107 km2), 58% of lands were predicted to lose soil Se (i.e., ∆Se less than −2.5%; mean change = −8.4%); 20% were predicted to undergo minor changes (i.e., −2.5% < ∆Se < 2.5%; mean change = −0.3%); and 22% were predicted to gain soil Se (i.e., ∆Se > 2.5%; mean change = 5.7%) as a result of changes in climate and SOC (Fig. 3). Predicted soil Se losses were driven largely by changes in AI, whereas soil Se gains were driven largely by changes in precipitation and SOC (Fig. S1). Compared with the total land surface, croplands were expected to lose more soil Se. Based on future predictions for croplands (7.55 × 106 km2), 66% of lands were predicted to lose soil Se (∆Se less than −2.5%; mean change = −8.7%); 15% were predicted to undergo minor changes (–2.5% < ∆Se < 2.5%; mean change = −0.4%); and 19% were predicted to gain soil Se (ΔSe > 2.5%; mean change = 7.3%) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). Global pasture lands also were predicted to lose soil Se, but to a lesser extent than croplands, suggesting that Se deficiency in livestock could increase. Based on future predictions for pasture lands (2.55 × 107 km2), 61% of lands were predicted to lose soil Se (∆Se less than −2.5%; mean change = −8.0%); 19% were predicted to undergo minor changes (−2.5% < ∆Se < 2.5%; mean change = −0.4%); and 21% were predicted to gain soil Se (ΔSe > 2.5% mean change = 8.2%) (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). Areas with notable losses (i.e., ∆Se less than −10%) include croplands of Europe and India, pastures of China, Southern Africa, and southern South America, and the southwestern United States (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). Areas of notable gain (ΔSe > 10%) are scattered across Australia, China, India, and Africa (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

Global predictive maps illustrating the percentage change in soil Se in agricultural lands resulting from changes in climate and SOC. Pixels indicate land use that is dominated (≥25% of land area) by croplands (A) and pastures (B) as defined in ref. 66.

Temporal Changes in Soil Se.

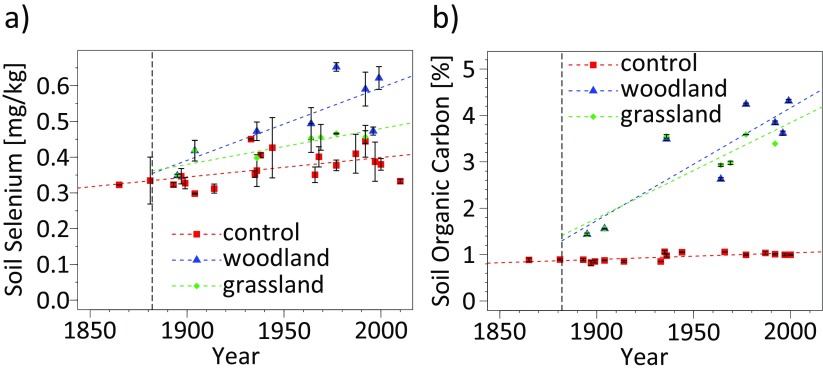

Although our analysis indicates that future climate change will likely result in widespread changes in soil Se, it does not indicate rates of change. To understand the temporal changes in soil Se concentrations better, we analyzed for soil Se and SOC in a subset of agricultural samples collected from the Broadbalk Experiment (Rothamsted, United Kingdom) between 1865 and 2010. Soil samples were taken from a control plot (unfertilized since 1843) and two “wilderness” plots (a maintained grassland and woodland), which were converted from the control plot in 1882 (SI Materials and Methods, and Table S3). The accumulation of Se in soil through time was statistically greater in the wilderness plots than in the control plot [one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA); year: F(1, 31) = 20.7, P < 0.01; plot F(2, 31) = 17.3, P < 0.01]. When controlling for SOC, however, there were no statistical differences between the plots (ANCOVA; SOC: F(1, 30) = 10.7, P < 0.01; year: F(1, 30) = 6.0, P < 0.05; plot: F(2, 30) = 3.2, P > 0.05), indicating that increases in SOC were driving soil Se accumulation in the model (Fig. S7), as is consistent with the results of the future modeling (Fig. S1). Natural changes in soil Se concentrations previously have been hypothesized to occur over longer time scales (e.g., hundreds to thousands of years) (54); however, given that SOC and Se began to accumulate on these plots immediately after conversion, these results suggest that changes in soil Se will follow environmental changes rapidly, perhaps on an annual to decadal time scale. Between ∼1880 and 1980, soil Se concentrations increased by ∼15, 35, and 60% on the control, grassland, and woodland plots, respectively (Fig. S7), indicating that the magnitude of changes predicted to occur by the end of the 21st century is plausible. The rates of change in soil Se concentrations following environmental perturbations is largely unstudied and should be evaluated further to understand soil Se dynamics better.

Table S3.

List of samples analyzed from the Rothamsted Sample Archive

| Plot | Year | Container label | Archive number |

| Control plot | 1856 | F-C-856 | No number |

| 1865 | F-C-865 | P120434 | |

| 1881 | F-C-881 | P116089 | |

| 1893 | K-C-893 | P120907 | |

| 1897 | K-C-897 | P121062 | |

| 1899 | K-C-899 | No number | |

| 1904 | F-C-904 | P120393 | |

| 1914 | F-C-914 | P122613 | |

| 1933 | K-C-933 | P121400 | |

| 1935 | K-C-935 | P121402 | |

| 1936 | K-C-936 | P121420 | |

| 1938 | K-C-938 | P121436 | |

| 1944 | F-C-944 | P122748 | |

| 1966 | F-C-966 | P123400 | |

| 1968 | K-C-968 | P123483 | |

| 1977 | K-C-977 | No number | |

| 1987 | F-C-987 | P123527 | |

| 1992 | F-C-992 | P123836 | |

| 1997 | F-C-997 | P124209 | |

| 2000 | K-C-000 | P122967 | |

| 2010 | F-C-010 | P230130 | |

| Grassland plot | 1936 | F-G-936 | P149593 |

| 1936 | F-M-936 | P168233 | |

| 1938 | F-M-938 | p168235 | |

| 1946 | F-M-946 | P168453 | |

| 1960 | F-M-960 | P168817 | |

| 1964 | F-G-964 | P149449 | |

| 1966 | F-M-966 | P168860 | |

| 1969 | F-G-969 | P208274 | |

| 1975 | F-M-975 | P174255 | |

| 1977 | F-G-977 | P149629 | |

| 1980 | F-M-980 | P174287 | |

| 1985 | F-M-985 | P174340 | |

| 1989 | F-M-989 | P174369 | |

| 1992 | F-G-992 | P149619 | |

| 1997 | F-M-997 | P174394 | |

| 2000 | F-M-000 | P174415 | |

| 2010 | F-M-010 | P230542 | |

| Woodland plot | 1881 | F-W-881 | P149468 |

| 1895 | F-W-895 | P149430 | |

| 1904 | F-W-904 | P149414 | |

| 1936 | F-W-936 | P149594 | |

| 1964 | F-W-964 | P149454 | |

| 1977 | F-W-977 | P149581 | |

| 1992 | F-W-992 | P149616 | |

| 1996 | F-W-996 | No number | |

| 1999 | F-W-999 | P106090 |

Fig. S7.

Temporal trends of analytes in agricultural soils from the Rothamsted Broadbalk experiments. Total soil Se (A) and SOC (B) concentrations were measured in the control, woodland, and grassland plots. Samples were analyzed from soils that were originally collected from 1865–2010. In 1882 (vertical dashed line), part of the control plot was left uncultivated and maintained as grassland and forest (collectively referred to as the “wilderness”). Error bars represent SDs (n = 2–4).

SI Materials and Methods

Geochemical Surveys.

To predict global soil Se concentrations, a wide variety of soil Se datasets were considered, and not all datasets or samples were included within the analysis. For example, several datasets that targeted or included stream sediments were not included in our analysis. Furthermore, we recognize that Se speciation is an important factor controlling bioavailability; however, broad-scale Se data have been reported exclusively as total Se, and Se speciation datasets with similar sample size and geographic breadth do not exist. Therefore predictive models could be made only for total Se concentrations.

In addition, we excluded datasets that we deemed lower in quality. High-quality datasets are essential for generating accurate predictions; however, this standard must be balanced against the need to obtain a sufficient quantity of data to be able to predict as wide a variety of environments as possible. In general, our preference for data (from highest quality to lowest quality) was as follows; we accepted data only from i, ii, and iii.

-

i)

Recent standardized continental or national geochemical surveys (n = 1,000s of samples). Soil Se is difficult to quantify; therefore recent surveys were preferred to older surveys because quantitative analyses have improved greatly during recent decades, and, as a result, the limit of detection is generally lower now than it was in the past. Typically, soil Se concentrations are low, and therefore it is imperative to have datasets that accurately quantify low concentrations of Se in the soil. In addition to recent surveys, we required datasets with large sample sizes that cover heterogeneous environments. This heterogeneity was important to be able to describe soil Se concentrations accurately in as many different environments across the globe as possible. Therefore, continental or national geochemical surveys were the most advantageous datasets, because they have been collected recently, have high sample sizes that cover a broad geographic range, and are collected and analyzed in a standardized way that minimizes the occurrence of error when aggregating datasets. The highest limit of detection for the broad-scale geochemical surveys was 0.2 mg Se/kg.

-

ii)

Recent standardized regional geochemical surveys (n = 100s of samples). To increase the geographic coverage of our dataset, it was important to include regional geochemical surveys. Although these surveys are smaller, they still have the advantage of being able to quantify low soil Se concentrations accurately. Furthermore, these surveys typically collected samples in a standardized manner throughout the covered range and do not focus on particular areas (e.g., Se “hotspots”). The environmental heterogeneity within these datasets is lower than in continental surveys, but these datasets were particularly helpful because we were able to fill particular gaps within our dataset that were not described by larger-scale studies. Because the highest limit of detection for the broad-scale geochemical surveys was 0.2 mg Se/kg, datasets with a limit of detection >0.2 mg Se/kg were not used in the analysis.

-

iii)

Recent local surveys (n = 10s of samples). Several localized surveys have been conducted, and although the data quality may be high, the inclusion several local surveys into the model undoubtedly introduces error resulting from differences in sample handling, processing, and analytics. Therefore, these datasets were used sparingly and only for specific environments where broad-scale standardized surveys have not been conducted (e.g., tropical areas). Because the lowest limit of detection for the broad-scale geochemical surveys was 0.2 mg Se/kg, datasets with a limit of detection >0.2 mg Se/kg were not used within the analysis. Some local surveys were excluded, however, because they were known to come from hotspot areas with elevated soil Se concentrations.

-

iv)

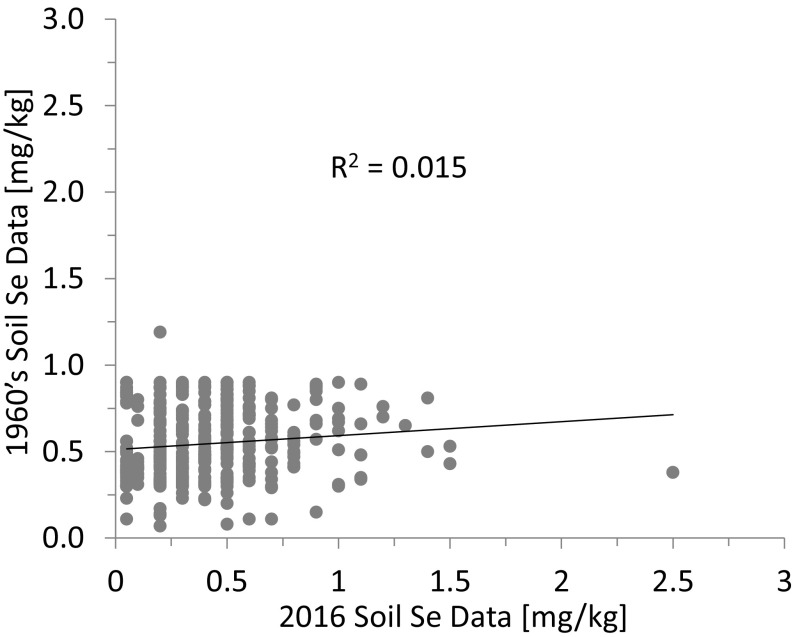

Local/regional surveys displayed as colored paper maps, typically from surveys conducted before the advent of geographic information systems (GIS). Several datasets exist as printed maps that illustrate Se concentrations as contours without any indication of sample point distributions. Lithology has frequently been reported as the dominant factor controlling soil Se concentrations, and as a result many Se concentration maps simply follow the boundaries of geological or soil maps without considering other factors such as SOC, pH, or clay content. Such illustrations are simply incorrect. When comparing soil Se maps from similar regions of southern New Zealand that were published in 2016 (27) and the in mid-1960s (precise date unknown) (59), it is clear that the two maps have no correlation. To illustrate this lack of correlation, the map from the 1960s was digitized, and for each of the 2016 data points (n = 347), the corresponding concentration based on the digitized map was recorded. Because the data of the digitized map were binned (i.e., grouped based on a range of concentrations), the concentration was assigned a random value within the range of the bin. A linear regression was made between the two datasets with a corresponding R2 value of 0.015 (Fig. S8), which is exceedingly low. Assuming that the modern map is an accurate representation of current Se distributions, using the contour map for modeling purposes would result in an entirely inaccurate prediction. The side-by-side comparison of these two datasets is advantageous because we can validate older maps with new data; however, few datasets exist for validation. Because of the inherent limitations of such maps, we deemed such data types unsuitable for our modeling purposes and did not include them in our analysis.

Fig. S8.

Se concentrations for soil samples measured in 2016 vs. Se values extracted for the same location from a 1960s contour map. The data on the x axis were collected from a recent standardized soil geochemical survey (27); the data on the y axis were published as a contour map in the mid-1960s (the exact date is unknown) (59). The map from the 1960s was digitized in ArcGIS 10.2, and for each of the data points from the recent geochemical survey, the corresponding concentration was recorded from the digitized map. Because the data within the map were binned, each point was randomly assigned a concentration value that fell within the range of the bin.

In total, 15 soil Se datasets with a soil sample size (n) of 33,241 were used for predictive modeling. The datasets, including country or region, the sample size, and the relevant citations, included the following: Alaska (n = 2,053) (14); Brazil (n = 70) (15–18); Canada (n = 724) (19–21); England and Wales (n = 5,681) (22); Europe (n = 4,131) (23); Japan (n = 178) (24); Kenya (n = 123) (25); Malawi (n = 276) (5, 26); New Zealand (n = 347) (27); Northern Ireland (n = 6,857) (https://www.bgs.ac.uk/gsni/); People's Republic of China (n = 3,027) (28); Republic of Ireland (n = 1,310) (erc.epa.ie/safer/iso19115/displayISO19115.jsp?isoID=7); South Africa (n = 148) (29), Tellus Border, Republic of Ireland (n = 3,475) (www.tellusborder.eu); and the continental United States (n = 4,841) (https://mrdata.usgs.gov/ds-801/).

Data from South Africa was provided directly from the Agricultural Research Council Institute for Soil, Climate and Water in a raster format without spatial details of the point locations (29). The raster was based on 3,500 data points collected throughout South Africa. The original raster resolution was ∼0.044° but was aggregated on a 1° cell. After aggregation, the total number of points was 148.

Soil Se Data Processing.

All Se data were continuous and georeferenced, with the exception of the Chinese data, which was printed in an atlas. The corresponding Se map of China was georeferenced and digitized in ArcGIS 10.2. In addition, each Se data point was binned into 10 classes within the atlas ranging from 0–3 mg Se/kg. To have a continuous output, each point was randomly assigned an Se concentration that fell within the range of its particular bin. Furthermore, for data points that were below the limit of detection, each value was assigned a concentration of half the limit of detection instead of the data being deleted.

The Alaska data consisted of several smaller datasets of varying quality. For example, the lower limit of detection for some datasets was 10.0 mg Se/kg, whereas for other datasets the concentrations were rounded to the nearest 0.5 mg Se/kg. To match the precision of other datasets, only datasets with a lower limit of detection of 0.2 mg Se/kg were retained. Where the value was below this limit, each value was assigned a concentration of 0.1 mg Se/kg, which is half the reported limit of detection (i.e., 0.2 mg Se/kg).

It was clear that pixels with the highest error occurred when only a few Se data points were available, whereas pixels with many data points typically had low error rates. Therefore, to remove the influence of outliers and errors within the soil Se dataset, pixels that contained fewer than five individual soil Se data measurements were excluded from the analysis.

Categorical Data.

In our modeling, categorical variables (e.g., soil type, land use, lithology) were usually poor predictors of Se and actually led to misleading results. For each category, a separate model is made that restricts the total number of soil Se samples available per model. Machine-learning models are often criticized for overfitting data. We found this overfitting to occur when the sample size was too small and especially when several categories were present with only a few cases per category. This condition resulted in curve fitting and artificially elevated the R2 of the model. For example, we created a variable that was a random integer representing five classes. This random variable was included in the model for testing purposes and, as a result, the perceived performance of the model increased. The artificial increase in model performance resulting from the use of categorical variables could explain why lithology was of moderate relative importance (Fig. S1) but resulted in minimal changes in modeled soil Se concentrations in sensitivity analyses (Fig. S4). To ensure adequate representation of soil Se data within each lithological class, we combined all classes with <200 soil Se data points instead of deleting data that fell into poorly represented classes.

Rescaling Procedures.

Each of datasets had different sampling, preparation, and analytical procedures, and these differences might bias the overall modeling results. To minimize the bias of any particular dataset, the entire dataset was resampled based on equal data representation (all datasets were equally represented based on sample size), equal density (each dataset was represented by the same sample density), equal scale (all points within a 1.0° cell were averaged and represented by a single value), and randomly (all data were sampled at random). For the equal data representation and equal-density resampling schemes, the datasets with the lowest number of points (Republic of Ireland) and lowest sampling density (China) determined the threshold sample size for the other datasets. Once this threshold was set, all points from all other datasets were selected at random to satisfy the selected criteria. For the equal scale and random datasets, all data were used for predictive modeling. The same cross-validation scheme was used to evaluate the performance of each model: 90% of the data were randomly selected for model training, and 10% were selected for cross-validation. Based on the performance of the cross-validation model, the equal-scale resampling performed the best. One drawback of this technique is that information is lost by averaging the data, and this loss could be problematic if small-scale or site-specific processes contribute to soil Se concentrations; however, because the goal was to evaluate the broad-scale processes, this reduction in information was deemed acceptable, especially given that this technique outperformed the other techniques.

The spatial resolution of all predictor variables was variable (∼1 km2 to 2.5°) (Table S1). Because the soil Se concentrations were averaged on a 1° scale, all predictor variables were also averaged on a 1° scale. All data were imported into ArcGIS 10.2 and were resampled using the Resample (Data Management) tool. The bilinear resampling technique was used to interpolate values from the continuous raster linearly. For categorical data (e.g., lithology, land use, and soil type), we used the majority resampling technique, which identified the dominant category within each 1° cell.

Climate and SOC Models.

Projections of changes in climate variables were derived from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) archive (52). The following CMIP5 models were used: ACCESS1-0, ACCESS1-3, bcc-csm1-1, bcc-csm1-1-m, BNU-ESM, CanESM2, CCSM4, CESM1-BGC, CESM1-CAM5, CMCC-CM, CMCC-CESM, CNRM-CM5, CSIRO-aMk3-6-0, FGOALS-s2, GFDL-ESM2M, GFDL-CM3, GISS-E2-R, GISS-E2-H, HadGEM2-CC, HadGEM2-ES, NorESM1-ME, inmcm4, IPSL-CM5A-LR, IPSL-CM5A-MR, IPSL-CM5B-LR, MIROC-ESM-CHEM, MIROC-ESMMIROC5, MPI-ESM-LR, MPI-ESM-MR, MRI-CGCM3, and NorESM1-M. For each model, only the first ensemble member (r1i1p1) was used. The multimode mean was used in the analysis. The RCP6.0 scenario was used for consistency with the SOC projections. SOC data were derived from runs of the RothC model, driven by mean climate variables from the ECHAM5-A1B model runs, because these give climate forcing similar to the other climate-driver datasets used and because the projected SOC values were not very sensitive to the climate model used to drive RothC (33).

Variable Selection.

We used four techniques to evaluate whether each predictor variable should be included in the final model: correlations, PCA, backward elimination with artificial neural network (ANN) models, and RF node-purity analyses. All techniques were used simultaneously. The correlation and PCA analyses assume normality, which was assessed for all variables by examining the skew of the data. Variables were deemed normally distributed if the |skew| <1. Variables that were not normally distributed were either log10 or square-root transformed, which also reduced the influence of outliers.

Pearson’s correlation was used to check for multicollinearity. Predictor variables that were highly correlated (i.e., |r| >0.7) were evaluated further using partial correlations. Partial correlations were used to examine effects of a particular variable on Se while controlling for the effects of a third. Variables that were spuriously correlated with Se were removed from the analysis.

PCA is a commonly used variable-selection technique that summarizes the variability within a dataset into a small number of uncorrelated principal components (PCs). The first two PCs were retained for analysis because they summarize the greatest amount of information within the dataset. Therefore predictor variables that were poorly correlated with PCs 1 and 2 (i.e., variables that contain the least information) were removed from the analysis. In addition to normality, PCA assumes linearity between variables. Therefore, pairwise comparisons between variables were examined for extreme nonlinearities (e.g., horseshoe-shaped relationships); none were detected. Nevertheless, PCA was used with caution in removing variables.

We also used an iterative backward elimination procedure using ANN models (NNET in R and Multilayer Perceptron in SPSS) (60). All variables were added to the ANN model. The ANN model was run and the error was computed using the entire set of inputs. For a given input variable, all values were replaced with the variable mean, and the model was rerun to calculate the new error. For each variable, the difference in error was calculated. More relevant inputs produced higher error differences when removed and thus had greater predictive power in the model. Variables with lower predictive power, and thus low change in error when removed during the elimination procedure, were removed from the analysis. The same analysis was repeated using the variable importance. Variables with the lowest variable importance were removed first. The results of the variable selection when using the error and variable importance were similar.

Finally, we calculated the mean decrease in node impurity of a trained RF analysis (randomForest in R) with 100 trees generated. This test allowed us to determine which variable and covariable contributed strongly to the tree construction (61). Variables that contributed less to the model were removed from the analysis. Overall, there was high agreement among the PCA, ANN, and RF in identifying important variables. All spatial procedures were conducted in ArcGIS 10.2.2 and R.

Soil Se Modeling.

Three machine-learning techniques (two ANN models and one RF model) and SEM were used to investigate independently the mechanisms governing soil Se distributions and to predict soil Se concentrations on a global scale (only ANN and RF models were used for predictions). Following variable selection, seven variables [AI, clay content, ET, lithology, pH, precipitation, and SOC (0–30 cm depth)] were retained for predictive modeling. These variables also were used for the SEM, but because the SEM was not used for predictive modeling, additional variables (i.e., PET, evaporative index, latitude) were used to quantify direct and indirect interactions between all variables and to evaluate independently the probable mechanisms governing broad-scale soil Se concentrations.

The SEM fit was evaluated using the SRMR model and the CFI. The SEM was considered a good fit if SRMR ≤0.8 and CFI ≥0.95 (43). Only statistically significant (α = 0.05) variables were retained in the SEM analysis. SEM analysis was conducted in SPSS 22 AMOS.

Machine-Learning Modeling Approaches.

Known soil Se concentrations were modeled using the Multilayer Perceptron function in SPSS, the NNET package in R, and the randomForest package in R. Machine-learning models were performed in SPSS 22 and R. These three techniques were used to evaluate the relationships between each variable and soil Se independently to avoid predictive biases toward any technique.

SPSS Multilayer Perceptron Parameters.

The Multilayer Perceptron function was used in SPSS to develop a predictive ANN model. The following options were used for all SPSS ANN models.

Variables.

Rescaling covariates were standardized (i.e., standardized z-scores as defined by where S is the variable SD).

Architecture.

-

•

Hidden layers

o Number of hidden layers: 1

o Activation function: hyperbolic tangent

o Number of units: automatically compute

-

•

Output layer

o Identity

Training.

-

•

Type of training: online

-

•

Optimization algorithm: gradient descent

-

•

Training options

o Initial learning rate: 0.4

o Lower boundary of learning rate: 0.001

o Learning rate reduction, in epochs: 10

o Momentum: 0.9

o Interval center: 0

o Interval offset: ± 0.5

Options.

-

•

User-missing values

o Specify how to treat cases with user-missing values on factors and categorical-dependent variables: exclude

-

•

Stopping rules (although all stopping rules were set, the “maximum steps without decrease in error” was always reached first)

o Maximum steps without decrease in error: 10,000

o Maximum training epochs: 100,000

o Minimum relative change in training error: 0.1

o Minimum relative change in training error ratio: 0.1

R RandomForest Parameters.

Information on randomForest is available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForest/index.html.

-

•

All variables were rescaled to standardized z-scores (i.e., where S is the variable SD).

-

•

Tune randomForest for the optimal value (with respect to the out-of-bag error estimate) of the mtry parameter for randomForest. Computed with 100 generated trees.

-

•

Use tuning parameter to generated 100 trees for model building.

-

•

Recommended values from randomForest.

R NNET Parameters.

Information on R NNET parameters is available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nnet/nnet.pdf.

-

•

All variables were rescaled to standardized z-scores (i.e., where S is the variable SD).

-

•

Hidden layers

o Number of hidden layers: 1

o The number of units in the hidden layer and weight decay were optimized to get the smallest root mean square error of the model.

o Number of units in the hidden layer: 15

-

•

Weight decay: 0.01

-

•

The Hessian of the measure of fit at the best set of weights found is returned as component.

o Optimization done by least-squares fitting under the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) method. BGFS is a quasi-Newtonian method (also known as a “variable metric algorithm”) (62) that uses function values and gradients to build up a picture of the surface to be optimized.

-

•

Linear output units

o Maximum steps without decrease in error: 10,000

Sensitivity Analyses.

To determine how each variable independently affected soil Se, we performed uni- and bivariate sensitivity analyses for each predictive model. For univariate sensitivity analyses, we specifically wanted to describe how different environmental conditions affected soil Se concentrations. To obtain these environmental conditions, we first performed a two-step cluster analysis in SPSS 22. The optimal number of clusters was automatically generated (n = 3 zones). In initial cluster analyses, the clusters were dominated by variables that had large domains. Therefore, the standardized z-scores of all variables were used in the cluster analysis. Thus all continuous variables contributed more equally to the data’s classification. Lithology was excluded from the analysis because it is a categorical variable. A PCA was used to describe the physicochemical and climate characteristics of the three zones generated in the cluster analysis (Fig. S5). PCs were retained if their eigenvalue was >1; therefore, only two PCs were retained. No variable rotation was performed. The variables with the highest correlation with PC1 were pH and precipitation. PC2 was most correlated with SOC and clay content: positive values indicate soils with high clay content and low SOC, and negative PC2 values indicate the opposite. Therefore, the three zones can be described as high aridity/high pH/high clay (zone 1), high SOC/low aridity (zone 2), and high precipitation/high clay (zone 3).

Each of the three zones represents a different suite of environmental conditions. To isolate the individual effects of each predictor variable within each zone, each variable was allowed to vary between the observed minimum and maximum for each zone. The observed range of each variable (i.e., the maximum–minimum) was divided into nine equal intervals. For each variable, the sensitivity analysis was based on 10 points that consisted of the following values: minimum, minimum + 1*(range/9), … , minimum +9*(range/9). All other variables were held constant at the mean value for each particular zone. These suites of values then were entered into the predictive models to obtain 10 soil Se predictions. Because lithology is a categorical variable and has no “average” value, the range of values used for the continuous variables was used for each of the lithological classes, and the final results were averaged together to account for any lithological influences. For lithology sensitivity analyses, each continuous variable was held constant at the zonal values, and only the lithological class was allowed to vary. The predicted soil Se then was plotted against each variable (Fig. S4).

In addition to univariate analyses, we also performed bivariate analyses to evaluate how interactions between two variables affected soil Se concentrations. In bivariate analyses, zones were not used. Instead, each variable was allowed to vary between the minimum and maximum observed value of the 1,642 data points. As with the univariate analysis, 10 points were generated for both variables in the bivariate analysis. To determine how soil Se fluctuated in response to changes in both variables, soil Se was predicted for all possible pairwise combinations (n = 100 for all combinations). All other variables were held constant at the average value of the 1,642 data points. The predictive models then were used to predict the results of these inputs. All pairwise comparisons were examined, but only the most influential were included (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3).

Hypothesis Testing.

Based on the predicted response of soil Se within the sensitivity analyses and on the regression weights of the SEM, we tested various hypotheses describing the mechanisms driving soil Se concentrations. For example, precipitation can act as a source of Se via wet deposition but also induces Se removal from soil via leaching and affects many soil physicochemical properties such as pH, OC content, and clay content. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate both the direct and indirect effects of each variable on soil Se. Simple correlation analysis cannot be used to test hypotheses, because the total correlation is the sum of direct and indirect effects. Unlike correlation, however, the results from the sensitivity and SEM analyses allow us to tease apart direct and indirect effects, thereby facilitating hypothesis testing. The predictive model sensitivity analysis and SEM analyses are independent, the results of the two analyses strongly corroborate each other, and the results are consistent with findings from the literature, thus suggesting that the dominant mechanisms have been captured by both techniques and are described accurately.

Filtering Soil Se Predictions.

To be as conservative as possible, recent and future soil Se predictions were filtered. Recent predictions were filtered based on the domain of the dataset using the PCA used to describe the zones (Fig. S5). Based on the scatter plot of PCs 1 and 2, a polygon was drawn around the known soil Se data. If a prediction fell outside this polygon (indicating a unique environment that was not described by one of the locations within the soil Se dataset), that pixel was removed from the analysis.

Future soil Se predictions were filtered using two criteria. First, the SD and the mean of the predictive tools was used to screen the data. If the SD was >10% of the mean (i.e., SD > 0.1*mean) for a particular pixel, that pixel was removed from the analysis. The data that remained were almost exclusively pixels that were predicted to have small changes in soil Se concentrations, because of the variability in the range of the predictive models. For example, the RF model was the most extreme, with predicted changes ranging from −71 to 89%. The NNET model had predicted changes ranging from −52 to 90%, and the Multilayer Perceptron model had predicted changes ranging from −29 to 27%. Therefore, high changes for the RF model corresponded to relatively moderate changes in the Multilayer Perceptron model, leading to a high SD. Although the models corroborated each other in many instances (i.e., all three models predicted change in the same direction), the magnitude of the change resulted in a larger SD relative to the mean. Instead of increasing the SD:mean ratio, we added a second filter that captured pixels where there was good corroboration between the models. If all three models corroborated one other, the pixel was retained regardless of the SD. By increasing only the SD:mean ratio cutoff criteria, more pixels were included where the corroboration between the models was low (i.e., two models predicted loss and the other predicted gain and vice versa). This filtering resulted in pixels predicted to have low change because positive and negative predictions canceled out each other. The estimates resulting from the use of these two filtering approaches were deemed reliable either because there was high precision in the estimate or there was good corroboration between the models.

Estimated Mass Loss of Se from Soils.

The mass of Se lost from the top 30 cm of soil was calculated for the pixels that overlapped in the 1980–1999 and 2080–2099 predictions. Based on these pixels, which represent 48% of the global surface, soil Se concentrations are predicted to drop from 0.331 ± 0.003 mg Se/kg in 1980–1999 to 0.316 ± 0.002 mg Se/kg in 2080–2099 as a result of changes in climate and SOC. Based on the difference, ∼0.0144 mg Se/kg is predicted to be lost, on average, in soils at a depth of 0–30 cm over much of the 21st century. Using the following simple mass balance, we can estimate the total change in soil Se from the top 30 cm of soil:

where A is the modeled land surface area (∼48% of total land surface area) in square centimeters (7.19 × 107 km2 or 7.19 × 1017 cm2), d is the depth in centimeters (30 cm), ρ is the estimated average soil bulk density in kilograms per cubic centimeter (1.3 g/cm3 or 1.3 × 10−3 kg/cm3), ΔSe is the change in average soil Se concentration caused by changes in climate and SOC between 1980–1999 to 2080–2099 in metric tons per kilogram (0.0144 mg Se/kg or 1.44 × 10−11 metric tons of Se). Therefore, the total estimated mass of Se lost from the top 30 cm of soil over a 100-y period is 403,763 tons of Se, which equates to 4,037.6 tons of Se lost per year. This estimate reflects only 48% of the global surface. Based on this estimate, the annual estimated mass of Se lost from soils of 0–30 cm depth is roughly 20–30% of the total estimated mass of Se cycled annually in the atmosphere (13,000–19,000 t); however, it is unknown if this value is expressed in US or metric tons (10). Using this calculation, we roughly estimate that for the recent global prediction [∼70% of the world’s land surface (1.04 × 107 km2), 0.322 mg Se/kg], 13.1 million metric tons of Se are contained within the top 30 cm of soil.

Drivers of Changes in Soil Se Concentration.

Changes in future soil Se concentrations were modeled using changes in climate and SOC data for 2080–2099. To identify the variables driving the changes in soil Se between future and recent periods, changes in climate and soil variables (ΔAI, ΔET, Δprecipitation, and ΔSOC) were used to model changes in soil Se concentrations (ΔSe) on a global scale using the Multilayer Perceptron model in SPSS. Because different variables were responsible for driving losses and gains, separate models were generated that analyzed only pixels with predicted gains and only pixels with predicted losses. The relative variable importance of the predictive models was used to identify the variables in the model driving changes in soil Se concentrations (Fig. S1).

Temporal Changes in Agricultural Soil Se and SOC Concentrations.

Forty-nine soil samples (depth = 0–23 cm) collected in the period 1856–2010 were obtained from the Rothamsted Sample Archive. Soil samples were taken from a control plot (unfertilized since 1843) and two wilderness plots (a maintained grassland and woodland), which were converted from the control plot in 1882 (63). These soil samples were typically air-dried, ground to <2 mm, and stored in sealed containers in the Rothamsted archive. Before samples were taken from these jars, each jar was thoroughly mixed. Under a clean air hood, soil was removed from each sample container and weighed (∼5 g). Between each sample, the spatula was wiped clean and rinsed with ethanol. Table S3 for samples analyzed from the Rothamsted archive.

The samples were microwave-digested based on method 3051A (64, 65). Aliquots of 100–200 mg samples and a ratio of 4 mL HNO3 to 1 mL H2O2 and 1 mL H2O were added to15-mL polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) containers and were digested at high pressure (180 bar) and high temperature (250 °C) in an UltraCLAVE 4 microwave (Milestone Inc.). After digestion, solutions were transferred quantitatively and diluted to 25 mL (or 50 mL) with deionized water. Four solid reference materials were digested to check the digestion quality and element recovery: soil (silty loam soil reference material: CRM044), river sediments [Buffalo river sediment: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) 2704], a stream sediment (Chinese stream sediment: GBW07306), and a loess sediment (Chinese loess sediment: GBW07408).

The solutions were diluted further by a factor of 10 to reduce the concentration of major elements (e.g., iron) before measurement with inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS. The digested samples were allowed to sit in 50-mL tubes for 24 h. Then 1 mL of the supernatant was diluted with deionized water to 10 mL in a plastic tube. The digested reference material CRM044 was diluted by both a factor of 100 and a factor of 1,000 to match the concentrations of major (first dilution, Fe, Mn) and minor (second dilution, e.g., Se) elements, respectively, to the calibration curves.

Total concentrations of Se, As, Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Zn, P, and Pb were analyzed on an ICP-MS instrument (Agilent 7500cx). Calibration curves were checked by measuring three different liquid reference materials: TMDA 51.2 from the Canadian National Water Research Institute, 1643e from the NIST, and ARS-29, an additional internal reference material from the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. The average Se concentration in the procedural blanks was 12.4 ng/L. Recovery rates for Se in the solid reference materials (25–200 mg digested) were 78% for CRM044, 95% for NIST 2704, 101% for GBW07306, and 117% for GBW07408.

OC was measured in a two-step process. Total carbon (TC) was measured by combustion of the samples in a EuroVector EA 3000 Element Analyzer. Inorganic carbon (IC) was measured with a UIC CM5015 CO2 coulometer. The final OC value was obtained by the difference between TC and IC (TC − IC = OC).

Outlook

One of our aims was to identify the broad-scale mechanisms governing soil Se retention. Therefore, at a 1° resolution, the data used are likely too coarse to evaluate or identify the influence of many small- to regional-scale factors (e.g., local sources, specific soil and rock types, and so forth) affecting soil Se retention. To evaluate small-scale soil Se distributions or to test locally relevant hypotheses, scale-appropriate models are necessary.

Although some effects of climate change on global food security are predictable (e.g., decreased food production resulting from increased water stress), the predicted widespread reductions in soil Se caused by climate change were less foreseeable. Changes in other factors (e.g., specific Se sources, soil properties, soil and rock weathering, and others.) will likely have an additional effect on soil Se, but these factors were not analyzed because future projections for soil pH and clay content and spatial information on the contributions of anthropogenic and natural sources of Se are currently unavailable. These variables are likely to have an effect on soil Se concentrations. For example, given changes in industrial SOx and NOx emissions (55), soil pH will likely increase (56). Increases in pH may result in further losses of soil Se concentrations, given that soil Se and soil pH are inversely related. Therefore, updated soil Se predictions are likely to change as additional data become available.

Given the importance of climate–soil interactions on soil Se distributions, it is likely that other trace elements with similar retention mechanisms will experience similar reductions as the result of climatic change. Coupled with micronutrient stripping from agricultural lands (57), predicted losses of total Se in soils indicate that the nutritional quality of food may decrease, thereby increasing the worldwide risk of micronutrient deficiency. However, as stated previously, total soil Se concentrations are not the only factor determining Se levels in plants. Lower Se levels in soils could potentially compound the problems associated with the decrease in the nutritional value of some plants resulting from elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations (58). Potential micronutrient losses from agricultural soils could be offset by implementing agricultural practices that increase their retention [e.g., organic carbon (OC) adjustment]; however, such strategies may not increase soil Se in areas of increasing aridity, given the importance of AI in governing soil Se concentrations. Where soils cannot be manipulated to increase the long-term retention of Se, broad-scale micronutrient fertilization may be necessary to maintain an adequate nutrient content in crops.

Materials and Methods

Total Se concentrations in soils (mg Se/kg soil, reported herein as mg Se/kg; soils were air dried or oven dried) 0–30 cm deep (n = 33,241 samples) were obtained from Brazil, Canada, China, Europe, Japan, Kenya, Malawi, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States (SI Materials and Methods for dataset details and a discussion about which Se datasets were used, Fig. S8). Samples derived from stream sediments were excluded from this analysis. In addition, we obtained 26 variables describing factors hypothesized to control soil Se concentrations and moderate climate change projections (RCP 6.0 for climate and A1B for SOC data; Table S1 for variable descriptions and citations). All data within a 1° cell were averaged and represented by a single value. To minimize the influence of errors and/or outliers within the datasets, pixels containing fewer than five Se data points were removed from the analysis (SI Materials and Methods). The final soil Se dataset consisted of n = 1,642 aggregated points. Four techniques for selecting variables [e.g., correlations, principal components analysis (PCA), backward elimination modeling, and RF node purity analyses; SI Materials and Methods] were used to retain the following variables for predictive analysis: AI, clay content, ET, lithology, pH, precipitation, and SOC at a soil depth of 0–30 cm. Although 16 lithological classes were present within the raster dataset, classes that were represented by too few soil Se data points (n < 200) were grouped together instead of being deleted (Fig. S4 and SI Materials and Methods for further discussion).

Predictive modeling was performed using three machine-learning models (one RF and two artificial neural network models) (SI Materials and Methods). Each model was iterated 1,000 times using 90% of the data for model training and 10% of the data for cross-validation for each iteration. The training and cross-validation data were chosen at random for each iteration. The model predictions were averaged to estimate recent (1980–1999) global soil Se concentrations; however, predictions were considered valid only if the environmental parameters for each pixel fit within the domain of the observed data (Fig. S5).

Sensitivity analyses were performed during each iteration to investigate the independent effect of each variable on modeled soil Se concentrations. Based on all input variables, three environmental zones were identified using a two-step cluster analysis (SI Materials and Methods). Based on the data from each zone, individual parameters were allowed to vary while all other variables were held constant at the zonal averages. By using different zones, we could model the response of soil Se to changes in particular variables under different environmental conditions. These analyses allowed us to identify the most likely mechanism driving soil Se concentrations by comparing the predictions made by various hypotheses (Table S1) with the patterns observed in the sensitivity analysis.