Significance

Agrobacterium causes diseases in a wide range of host plants. It has been developed as a genetic tool to transform a variety of plant species and nonplant organisms. It can achieve a transformation efficiency as high as 100%. However, it is not clear how Agrobacterium virulence factors are trafficked through host cytoplasm to achieve such a wide host range and a high efficiency. Here we report that Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 is trafficked inside plant cells via the endoplasmic reticulum and F-actin network. This trafficking is powered by myosin XI-K. As the myosin-powered actin network is well conserved, our data suggest that Agrobacterium hijacks the conserved host network for virulence trafficking to transform a wide range of recipient cells with high efficiency.

Keywords: VirE2, protein trafficking, myosin, endoplasmic reticulum, actin filaments

Abstract

Agrobacterium tumefaciens causes crown gall tumors on various plants by delivering transferred DNA (T-DNA) and virulence proteins into host plant cells. Under laboratory conditions, the bacterium is widely used as a vector to genetically modify a wide range of organisms, including plants, yeasts, fungi, and algae. Various studies suggest that T-DNA is protected inside host cells by VirE2, one of the virulence proteins. However, it is not clear how Agrobacterium-delivered factors are trafficked through the cytoplasm. In this study, we monitored the movement of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 inside plant cells by using a split-GFP approach in real time. Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 trafficked via the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and F-actin network inside plant cells. During this process, VirE2 was aggregated as filamentous structures and was present on the cytosolic side of the ER. VirE2 movement was powered by myosin XI-K. Thus, exogenously produced and delivered VirE2 protein can use the endogenous host ER/actin network for movement inside host cells. The A. tumefaciens pathogen hijacks the conserved host infrastructure for virulence trafficking. Well-conserved infrastructure may be useful for Agrobacterium to target a wide range of recipient cells and achieve a high efficiency of transformation.

The soilborne phytopathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens is capable of the interkingdom transfer of genetic material (1). It can deliver transferred DNA (T-DNA) (2, 3) through a VirB/D4 type IV secretion system (T4SS) (4) into various recipient cells. Although plant species are the natural hosts for this T-DNA transfer, other eukaryotic species can be transformed under laboratory conditions, including yeast (5, 6), fungal (7), and algal cells (8).

The T4SS secretes proteins and nucleoprotein complexes into recipient cells (4). During the transfer process, T-DNA is nicked and processed from the T-region on the Ti-plasmid by VirD1–VirD2 endonuclease inside the bacteria (9–11). Afterward, VirD2 remains covalently attached to the 5′ end of the single-stranded (ss) T-DNA (T-strand) (10, 11). This nucleoprotein complex is then translocated to recipient cells, along with other virulence proteins such as VirD5, VirE2, VirE3, and VirF (12–14).

VirE2 is the most abundant among the bacterium-encoded Vir proteins (15). VirE2 can bind to T-DNA in vitro in a cooperative manner (16, 17); it is hypothesized to play a critical role in protecting T-DNA from nucleolytic degradation during cytoplasmic trafficking inside the host cells (18). This hypothesis is supported by studies showing that VirE2 has the ability to bind to ssDNA and to self-aggregate to form solenoid superstructures (19). VirE2 contains nuclear localization signals (NLSs) that facilitate the nuclear import of VirE2 and potentially the T-DNA (20–22). There is evidence to suggest that VirE2–T-DNA interaction plays a role in targeting the T-DNA into the nucleus independent of the nuclear targeting activity of VirD2 (22). Ectopic expression of VirE2 showed a predominant cytoplasmic localization of VirE2 in various types of plant cells (23). However, with the use of a split-GFP approach, a significant amount of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 was localized inside plant nuclei under natural infection conditions (24). Furthermore, it is important to study the trafficking process of VirE2 in the cytoplasm of host cells to understand the transformation mechanism.

As VirE2 aggregates as a solenoid structure, its large size may prevent the VirE2 complex from reaching the host nucleus through the dense structure of the cytoplasm by Brownian diffusion (25). Hence, there should be an active mechanism for VirE2 trafficking inside plant cells (26). Previous studies have shown that the interaction of VirE2 with the transcription factor VIP1 (27) may facilitate VirE2 nuclear targeting by using the MAPK-targeted VIP1 defense signaling pathway (28). However, the role of VIP1 in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is debatable (23). It is unclear how any of the bacterial effectors and their host partners are trafficked inside host cells to facilitate the transformation.

An in vitro study showed that the presence of “animalized” VirE2 (the VirE2 NLS was modified to become a bipartite NLS similar to nucleoplasmin) invoked active transport along microtubules in a cell-free Xenopus egg extract (29). In animal cells, microtubules are projected radially from the centrosome; thus, this trafficking mechanism would effectively transport nuclear-targeted cargo close to the nuclear envelope for import (29). Ectopically expressed VirE2 in yeast was also reported to colocalize and physically interact with microtubules (30). These lines of evidence implicate microtubules in VirE2 trafficking. However, unlike animals and fungi, flowering plants lack a retrograde transporter, i.e., dyneins (31). Moreover, plant microtubules lack conspicuous organizing centers; their arrangements are fundamentally different from their animal, fungal, and protistan counterparts (32). Hence, microtubules may not be optimal for VirE2 trafficking toward plant nuclei. It is not yet clear whether plant microtubules play any role in this trafficking.

Currently, no natural system has been used to study the trafficking of VirE2 or any of the T-complex components inside plant cells. In vitro experiments that use isolated components may disrupt the host infrastructure that facilitates the trafficking process. Consequently, it is still unknown what kind of host network drives the trafficking of T-complex inside plant cells.

Recently a split-GFP–based method that could directly detect the Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 inside plant cells was developed (24). This split-GFP approach enabled the visualization of VirE2 trafficking in recipient cells in real time in a natural setting and demonstrated that Agrobacterium delivered VirE2 into plant cells at as much as 100% efficiency (based on the number of plant cells in contact with the bacteria) (24). In the present study, the movement of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 was dissected inside plant cells in real time.

Results

Agrobacterium-Delivered VirE2 Moves on a Strand-Like Cellular Structure.

A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells, encoding VirE2-GFP11 fusion, were infiltrated into the leaf tissues of transgenic tobacco (Nb308A) plants, which constitutively expressed GFP1-10 and free DsRed, which labeled the cellular structures and nucleus (24). Upon delivery into plant cells by the bacterium, VirE2-GFP11 complemented GFP1-10. The resulting VirE2-GFPcomp signals were found inside plant cells. At 2 d after agroinfiltration, VirE2-GFPcomp aggregates started to appear (Fig. 1).

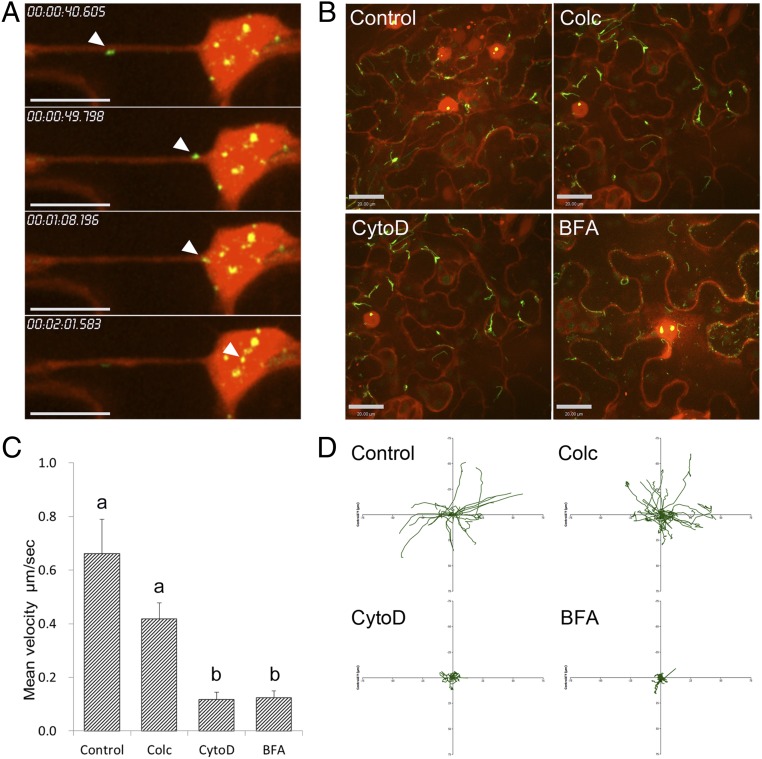

Fig. 1.

Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 trafficking on a cellular structure and entering the nucleus. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells were infiltrated into transgenic tobacco (Nb308A) leaves expressing GFP1-10 and DsRed. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates free DsRed; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. (A) Time-lapse images of VirE2 aggregates trafficking along a linear cellular structure and entering the nucleus. Relative time is shown at top left. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (B) Effects of chemical treatments on VirE2 trafficking. Chemicals were infiltrated into leaf samples 6 h before observation. Control: 0.5% DMSO (Colc, 500 μM; CytoD, 20 μM; BFA, 100 μg/mL). (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (C) Mean velocities of VirE2 aggregate movement after chemical treatments. Data were analyzed with ANOVA and Tukey test (P < 0.05). (D) Plot of the movements of 20 individual VirE2 aggregates relative to a common origin for each treatment.

The free DsRed expressed in the tobacco plants was localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Additionally, the free DsRed could label some cellular structures, presumably because of its association with them. As shown in Fig. 1A and Movie S1, VirE2-GFPcomp signals moved along a strand-like cellular structure labeled with free DsRed. Furthermore, direct entry of VirE2 into the nucleus was visualized. To ensure this observation was not a false colocalization caused by an axial projection, a 3D opacity view of the nucleus was generated based on the same image data set. The 3D rotation showed that the optical slices and VirE2-GFPcomp signals were within the nucleus (Movie S2). This confirmed that the VirE2-GFPcomp signal in Movie S1 entered the nucleus. VirE2 moved at a speed of 1.1 μm/s along the linear track, but it slowed down around the nucleus area. The average velocity was 0.434 μm/s over the entire trafficking event. Generally, VirE2 moved faster along linear tracks, even though the velocities varied on different linear tracks and moved slower along curved tracks.

VirE2 Trafficking Is Sensitive to Cytochalasin D and Brefeldin A.

Subsequently, the cellular structure that facilitated the movement of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 inside plant cells was investigated. Transgenic tobacco (Nb308A) plants were treated at 42 h after agroinfiltration with chemicals known to disrupt cellular structures. The effects were observed 6 h later. As shown in Fig. 1 B–D and Movies S3–S6, cytochalasin D (CytoD) and Brefeldin A (BFA) had a significant effect on the VirE2 trafficking, whereas colchicine (Colc) had only a minor effect. More than 20 independent VirE2 movements for each treatment were measured. CytoD and BFA treatment were found to reduce the average velocities of VirE2 movement to less than 20%, whereas Colc treatment retained more than 60% of the average velocity of the control (Fig. 1C).

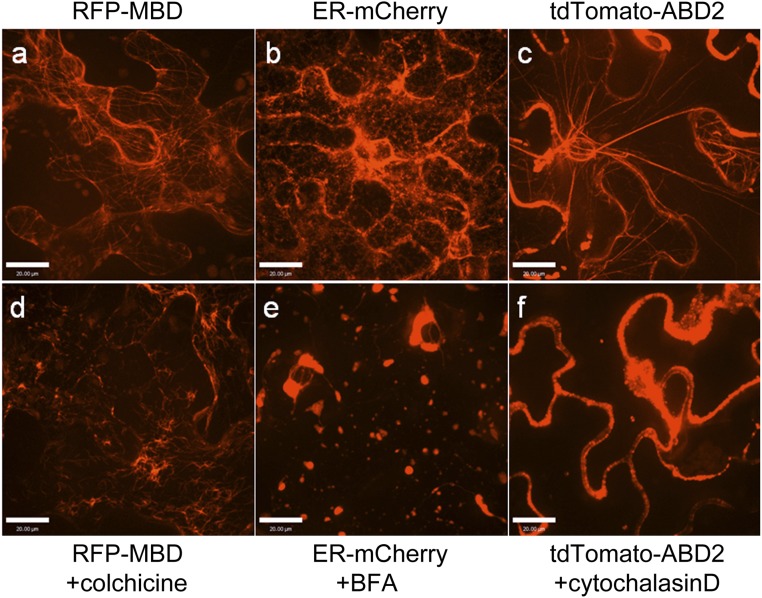

CytoD is a potent inhibitor of actin polymerization (33). BFA inhibits protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi apparatus by dilating the ER (34). Colc inhibits microtubule polymerization (35). The effects of these inhibitors on the corresponding cellular structures were observed in tobacco leaves. Colc, BFA, and CytoD disrupted the microtubules, ER, and actin structures, respectively (Fig. S1). Therefore, we hypothesized that VirE2 trafficking was facilitated by ER/actin structures.

Fig. S1.

Effects of chemicals on cellular structures. WT N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with binary plasmids encoding different fluorescent markers. The epidermal cells were examined at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. (A–C) Leaf samples expressing subcellular markers. (D–F) Chemically treated leaf samples expressing subcellular markers: (A) RFP-microtubule binding domain (MBD), (B) ER-mCherry, and (C) tdTomato-ABD2. ABD, actin binding domain. (D) RFP-MBD: leaf samples were treated with 500 μM Colc at 6 h before imaging. (E) ER-mCherry: leaf samples were treated with 100 μg/mL BFA at 6 h before imaging. (F) tdTomato-ABD. Leaf samples were treated with 20 μM CytoD at 6 h before imaging. (Scale bar: 20 μm.)

VirE2 Movement Is Associated with ER.

To determine if VirE2 movement is associated with the ER, we used an ER-mCherry construct containing an ER targeting sequence at the N terminus and the tetrapeptide retrieval signal HDEL at the C terminus (36). Both GFP1-10 and ER-mCherry constructs were then introduced into a T-DNA harbored on a binary plasmid to generate pQH308ER. The plasmid was introduced into EHA105virE2::GFP11 expressing VirE2-GFP11, which functioned like WT VirE2 (24).

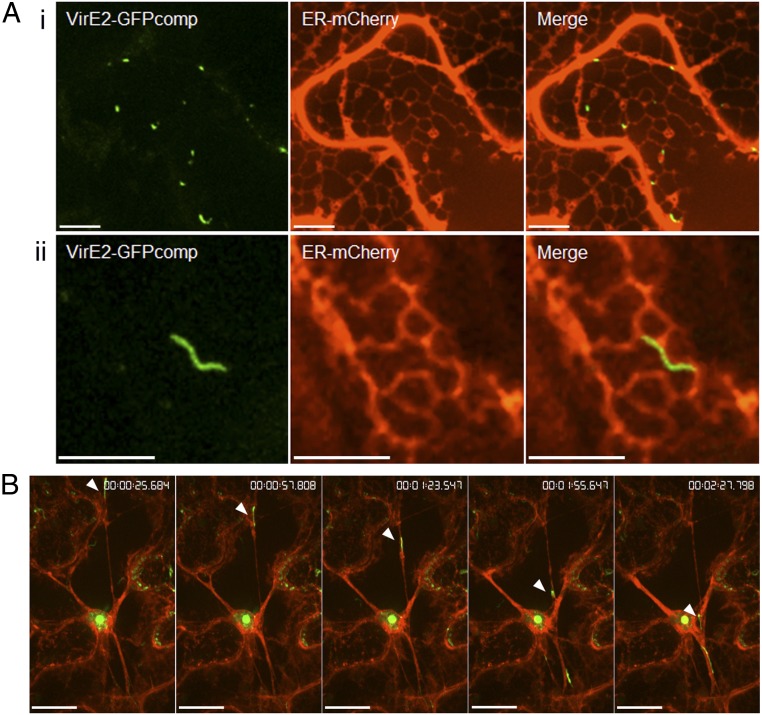

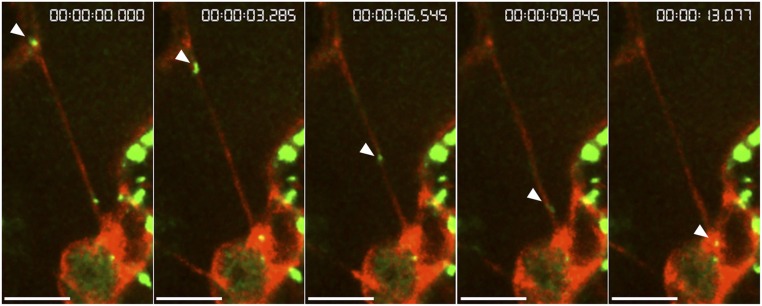

EHA105virE2::GFP11(pQH308ER) cells were infiltrated into WT Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2-GFPcomp signals were observed. As shown in Fig. 2A, VirE2 aggregates appeared as dots (Fig. 2 A, i) and filaments (Fig. 2 A, ii) inside the tobacco cells. Both forms were colocalized with interconnected ER tubules, as shown by ER-mCherry. The VirE2 filaments matched with the ER tubules along most of their lengths except for a small region of mismatching (Fig. 2 A, ii). It is not clear whether the mismatching was real, or the result of a distortion of the images caused by the gap time required to detect the two different colors, during which the ER or VirE2 moved. Time-lapse imaging showed that VirE2 aggregates moved along the ER strands (Fig. 2B and Movie S7). The average velocity was 0.502 μm/s during this linear movement, which is consistent with our earlier observations.

Fig. 2.

Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 colocalizing with and trafficking on the ER network. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells harboring a binary plasmid pQH308ER, which encodes ER-mCherry and GFP1-10, were infiltrated into WT N. benthamiana leaves. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates ER-mCherry; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. (A) VirE2 aggregates colocalizing with interconnected ER tubules. (i) VirE2 aggregates appearing as dots; (ii) VirE2 aggregates appearing as filaments. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (B) Time-lapse images of VirE2 aggregates trafficking on an ER strand. Relative time is shown at top right. (Scale bar: 20 μm.)

VirE2 Is on the Cytosolic Side of ER Inside Plant Cells.

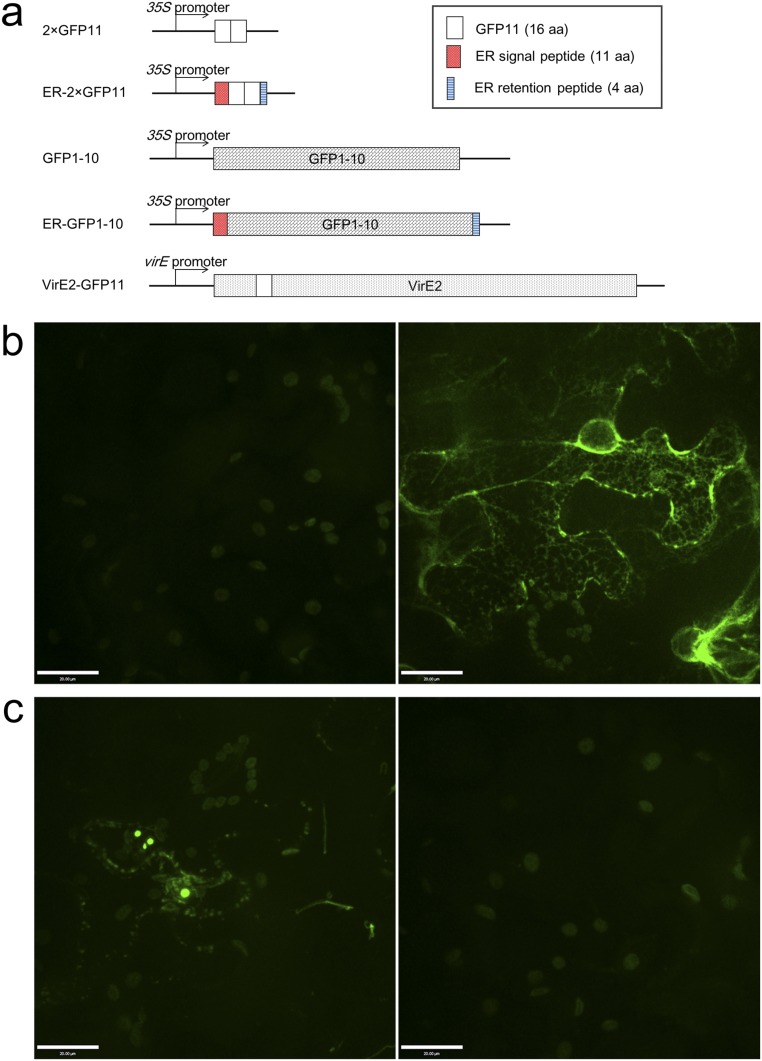

As ER membranes compartmentalize the intracellular space into ER lumen and cytosol, it was necessary to determine whether VirE2 was present on the cytosolic or luminal side. Therefore, an ER–GFP1-10 construct was generated that contained an ER targeting sequence at the N terminus of GFP1-10, so that the fusion could be targeted into the ER, and an ER retention signal HDEL at the C terminus, so that the fusion could be retained inside the ER. A two-tandem GFP11 (2×GFP11) and its ER-localizing construct (ER-2×GFP11) were also generated.

These constructs were expressed in WT N. benthamiana leaves by agroinfiltration. GFPcomp signals were detected when ER–GFP1-10 was coexpressed with ER-2×GFP11, but not with 2×GFP11 (Fig. S2 A and B). This demonstrated that the ER–GFP1-10 construct was localized inside the ER lumen. EHA105virE2::GFP11 containing VirE2-GFP11 was infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves, which transiently expressed GFP1-10 or ER–GFP1-10. As shown in Fig. S2C, Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2-GFP11 complemented GFP1-10, but not ER–GFP1-10. This demonstrated that Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 was on the cytosolic side of the ER after delivery into plant cytoplasm.

Fig. S2.

Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 present on the cytosolic side of ER. WT N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with binary plasmids encoding GFP1-10 or GFP11 with or without ER targeting signals. The epidermal cells were examined at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. (A) Gene constructs introduced into tobacco cells. (B, Left) Coexpression of 2×GFP11 and ER-GFP1-10; (Right) coexpression of ER-2×GFP11 and ER-GFP1-10. (C, Left) Agroinfiltration of EHA105virE2::GFP11 harboring a binary plasmid encoding GFP1-10; (Right) agroinfiltration of EHA105virE2::GFP11 harboring a binary plasmid encoding ER-GFP1-10. (Scale bar: 20 μm.)

VirE2 Moves on F-Actin Filaments.

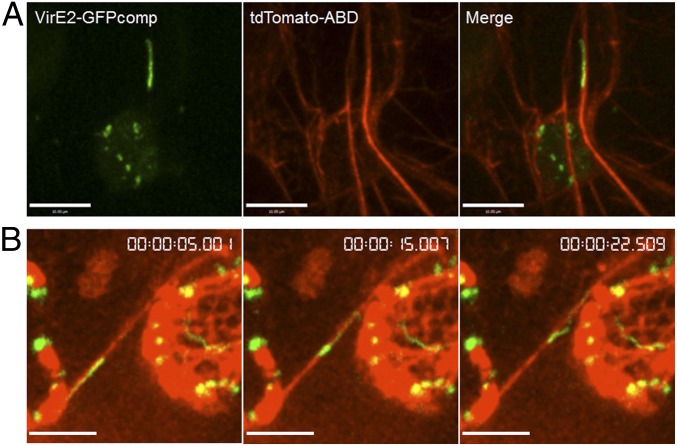

We determined whether VirE2 movement is associated with F-actin filaments. It has been shown that CytoD inhibits VirE2 movement (Fig. 1 B–D) and that CytoD can prevent polymerization of F-actin monomers (33). To visualize F-actin and VirE2, an F-actin marker tdTomato-ABD2 (37) was expressed by agroinfiltrating EHA105virE2::GFP11 into transgenic N. benthamiana Nb307A leaves expressing GFP1-10. As shown in Fig. 3, VirE2-GFPcomp signals colocalized with F-actin filaments. Time-lapse imaging demonstrated that VirE2 moved along an F-actin filament (Movie S8).

Fig. 3.

Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 colocalizing and trafficking on F-actin filaments. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells harboring a binary plasmid pB5tdGW-ABD2, which encodes an actin marker tdTomato-ABD2, were infiltrated into transgenic tobacco (Nb307A) leaves constitutively expressing GFP1-10. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates F-actin; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. (A) VirE2 aggregates colocalizing with F-actin filaments. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (B) Time-lapse images of VirE2 aggregates trafficking on F-actin filaments. Relative time is shown at top right. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

VirE2 Movement Is Myosin-Dependent.

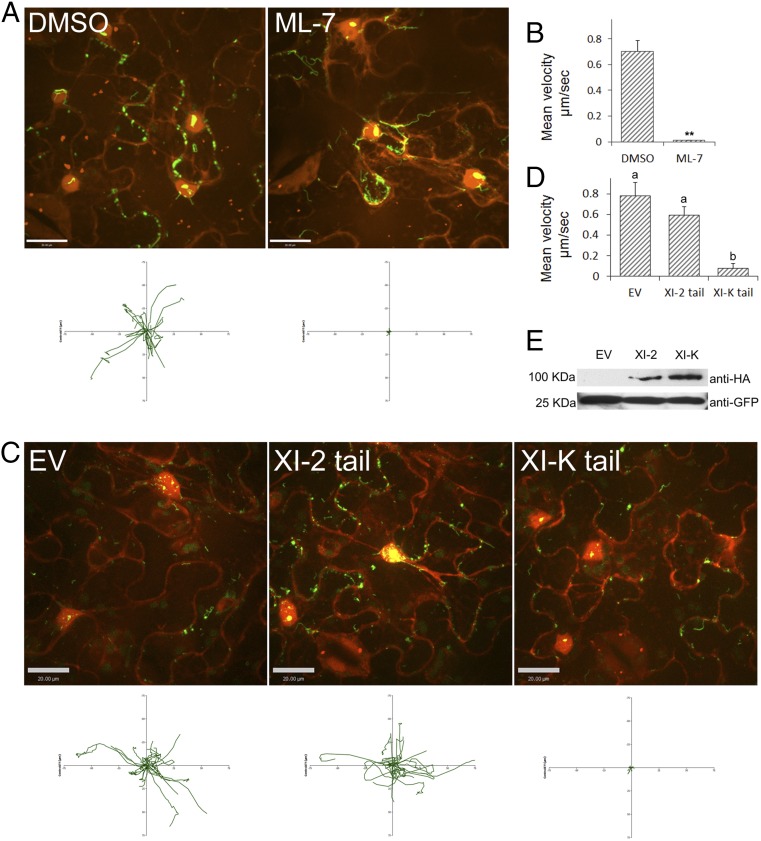

We determined whether myosin plays a role in VirE2 movement inside plant cells, as ER/F-actin/myosins may exhibit a three-way interaction (38). First, a selective myosin light-chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 (39) was used to inhibit the plant myosin activity. As shown in Fig. 4 and Movies S9 and S10, treatment with ML-7 inhibited VirE2 movement, as average velocity was reduced by 95% relative to the control.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ML-7 and myosin-tail overexpression on VirE2 trafficking. (A) Effect of ML-7 on VirE2 trafficking. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells were infiltrated into transgenic tobacco (Nb308A) leaves expressing GFP1-10 and DsRed. The leaves were infiltrated with 100 μM ML-7 or 1% DMSO control 4 h before imaging. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates free DsRed; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. A plot of the movements of 20 individual VirE2 aggregates relative to a common origin is shown below the figure. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (B) Mean velocity of the VirE2 aggregates after ML-7 treatment (**P < 0.01, t test). (C) Effects of myosin-tail overexpression on VirE2 trafficking. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells harboring a binary plasmid that encoded a tail fragment of corresponding myosins were infiltrated into transgenic tobacco (Nb308A) leaves expressing GFP1-10 and DsRed. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates free DsRed; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. A plot of the movements of 20 individual VirE2 aggregates relative to a common origin is shown below the figure. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) (D) Mean velocity of VirE2 aggregate movement under overexpression of myosin tails. EV, empty vector control. Data analyzed with ANOVA and Tukey test (P < 0.01). (E) Western analysis of crude extracts from leaf samples agroinfiltrated with myosin-tail constructs. Myosin tails were HA-tagged. GFP1-10 was detected to assess the amount of sample loaded (Lower).

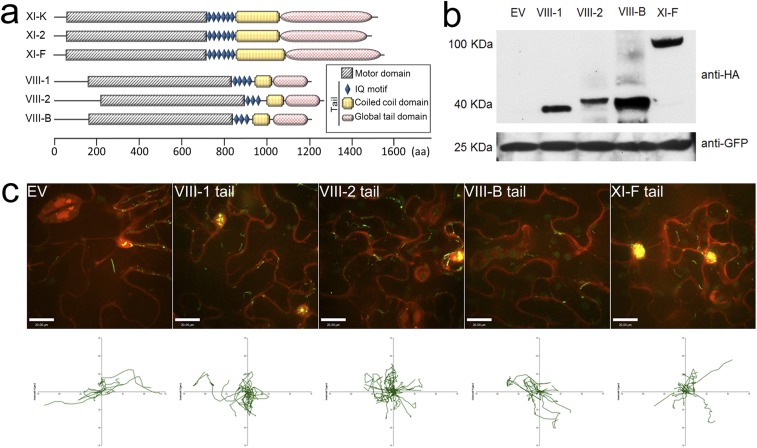

Subsequently, a dominant-negative approach was adopted to identify the specific myosin responsible for VirE2 movement. Several dominant negative mutants of plant myosin genes were overexpressed during Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of VirE2. A. tumefaciens cells containing T-DNA harboring the tail constructs were coinfiltrated with EHA105virE2::GFP11 into tobacco (Nb308A) plants. The myosin tail expression took place later than VirE2 delivery so that the myosin mutant constructs would not affect the VirE2 delivery. Among the myosin mutants tested, only XI-K tail inhibited the VirE2 trafficking (Fig. 4C, Fig. S3C, and Movies S11–S13). The average velocity was reduced to 10% of that of the control (Fig. 4D). In contrast, overexpression of XI-2 and other myosin tails had only minor or insignificant effects (Fig. 4C and Fig. S3C). These data suggest that myosins provided the driving force for VirE2 movement, and that myosin XI-K was the most important contributor.

Fig. S3.

Effects of myosin-tail overexpression on VirE2 trafficking. A. tumefaciens EHA105virE2::GFP11 cells harboring a binary plasmid, which encoded a tail fragment of corresponding myosins downstream of the 35S promoter, were infiltrated into transgenic N. benthamiana (Nb308A) leaves expressing GFP1-10 and DsRed. The leaf epidermal cells were observed at 2 d after agroinfiltration by confocal microscopy using an Olympus UPLSAPO 60× N.A. 1.20 water-immersion objective. Red indicates free DsRed; green indicates VirE2-GFPcomp. (A) Schematic presentations of myosin-tail constructs introduced into tobacco cells. (B) Western analysis of leaf samples agroinfiltrated with myosin-tail constructs. EV, empty vector control. Myosin tails were HA-tagged. GFP1-10 was detected to assess the amount of sample loaded (Lower). (C) Effects of myosin-tail overexpression on VirE2 trafficking. Z-slices were captured in 0.5-μm steps. Extended-focus image is shown. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) A plot of the movements of 20 individual VirE2 aggregates with respect to a common origin is shown below the figure.

It is of particular interest to determine whether VirE2 movement inside the cell is dependent on the NLS. As mutation at NLS1 of VirE2-GFP11 prevented the nuclear localization of VirE2-GFPcomp signals (24), a VirE2 NLS1 mutant strain can be expected to have a reduced ability to deliver any ER marker construct and thus not be suitable for use in a transient expression assay. Introducing a second strain to deliver functional VirE2 would inevitably generate chimeric VirE2 aggregates, which could interfere with the behavior of VirE2ΔNLS1. Therefore, a transgenic tobacco Nb308ER was generated, which constitutively expressed GFP1-10 and ER-mCherry.

EHA105virE2ΔNLS1::GFP11 was infiltrated into the epidermal cells of Nb308ER. As shown in Fig. S4, VirE2ΔNLS1 was colocalized with, and moved along, the ER strands. This demonstrated that VirE2 movement along the ER was independent of NLS, although NLS is required for nuclear targeting (20). VirE2 moved toward the nucleus, presumably because the ER that facilitated VirE2 movement was linked to the nucleus. Nevertheless, the nuclear targeting might have been independent of VirE2 trafficking along the ER.

Fig. S4.

Time-lapse images of NLS1-mutated VirE2 trafficking on ER strands. EHA105virE2Δnls1 (amino acids 221KLR…KYGRR237 were replaced by alanine) cells were infiltrated into transgenic N. benthamiana (Nb308ER) leaves constitutively expressing ER-mCherry and GFP1-10. Relative time is shown at top right. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation Requires Myosin XI-K.

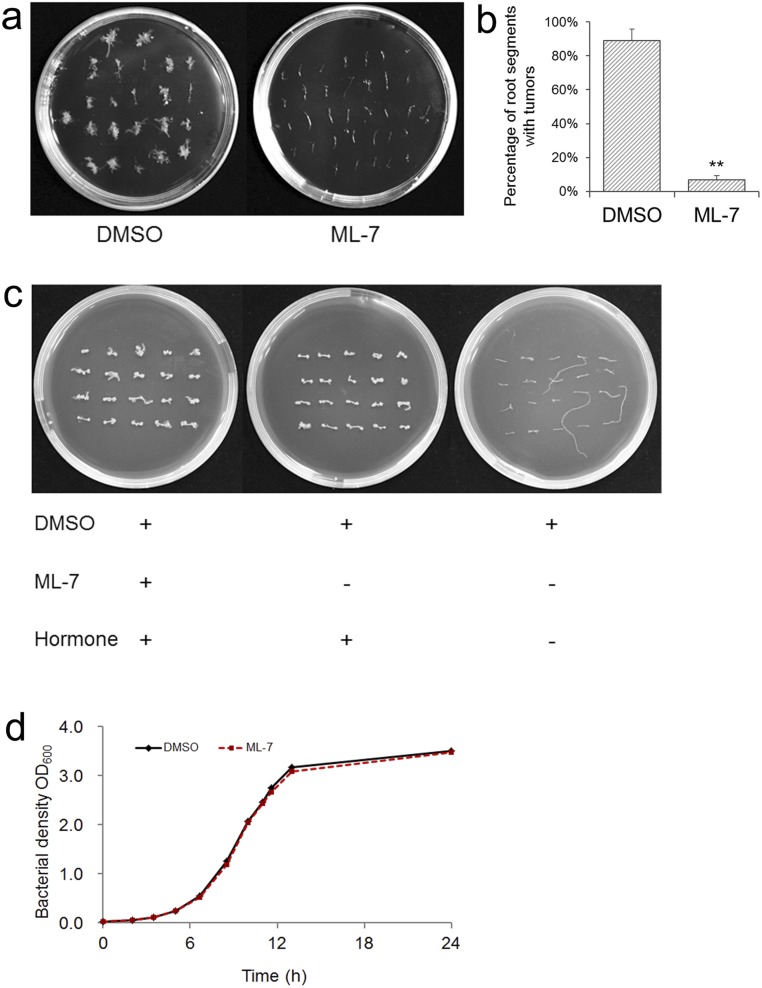

To determine if the VirE2 movement observed during our study was directly related to Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, the effect of the selective myosin light-chain kinase inhibitor ML-7 was tested on Arabidopsis root transformation. Root segments were inoculated with the tumor-inducing strain A348 in the presence of 10 μM ML-7. As shown in Fig. S5, ML-7 significantly reduced the transformation efficiency. The toxicity of ML-7 was tested on the root and Agrobacterium growth at 10 μM. The root segments were exposed to ML-7 for 2 d, which was the time span of the bacterium–Arabidopsis cocultivation. As shown in Fig. S5C, ML-7 did not affect the growth of root segments in the presence of hormones (auxin and cytokinin), nor did ML-7 inhibit Agrobacterium growth (Fig. S5D). These results suggest that the inhibition of myosin activity might have reduced the transformation efficiency.

Fig. S5.

Effects of ML-7 treatment on root transformation assays. Root segments from 10-d-old WT A. thaliana seedlings were infected with the tumor-inducing Agrobacterium strain A348. Tumors were photographed 3 wk later. (A) Tumors formed with or without ML-7 treatment. ML-7 was added (10 μM) into the cocultivation mixture and washed off when the root segments were transferred onto new plates for tumor formation. (B) Transformation efficiency as determined by the percentage of root segments with tumors (**P < 0.01, t test). (C) Effect of ML-7 on root segment viability. Root segments were exposed to 10 μM of ML-7 for 2 d and washed off before being transferred onto new plates for growth. (D) Effect of ML-7 on Agrobacterium viability.

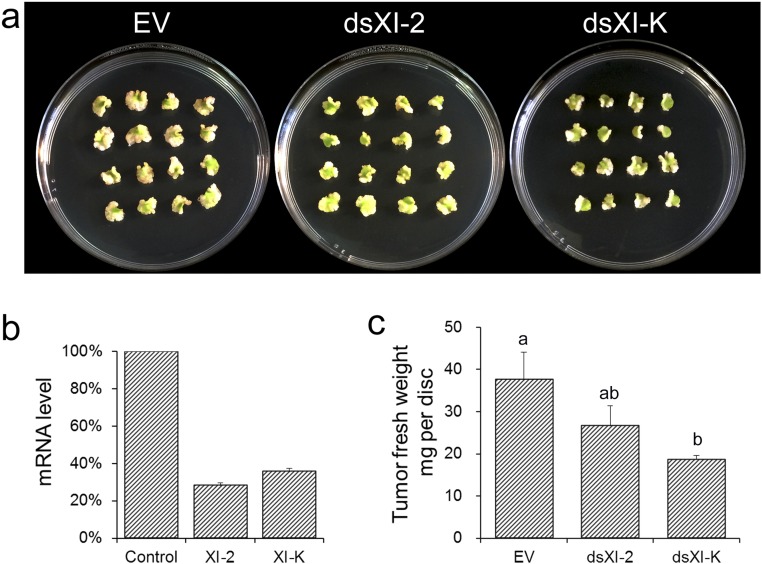

To confirm the specific effect of myosin inhibition on transformation, RNAi constructs containing a partial sequence of XI-2 and XI-K (40) were used to silence the corresponding genes. The RNAi constructs used for the experiments generated specific effects but not off-target effects (40). As shown in Fig. S6, silencing of XI-K attenuated tumor formation. The data clearly indicated that XI-K affected VirE2 movement and thereby Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

Fig. S6.

Effects of RNAi silencing of XI-2 and XI-K on tumor formation. WT N. benthamiana plants were agroinfiltrated with suitable RNAi constructs. The mRNA analysis and agroinfection were conducted 3 wk later. (A) Leaf disk tumors with XI-2 or XI-K gene silenced by RNAi. (B) The mRNA levels of XI-2 or XI-K gene in silenced plants as determined by real-time PCR. (C) Average fresh weight of leaf discs with tumors. Data were analyzed with ANOVA and Tukey test (P < 0.05).

Discussion

A. tumefaciens has the ability to deliver the virulence factor VirE2 into recipient cells (24). The high efficiency of this process enabled us to dissect the movement of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 inside plant cells. As shown here, the bacterium hijacks conserved host network to move virulence factor VirE2 toward the nucleus. This may be important for Agrobacterium to achieve a wide host range and a high efficiency.

To transform plant cells, Agrobacterium must be able to deliver its virulence factors into host cells efficiently. These exogenous factors must be able to move toward suitable locations to exercise their functions inside host cells. It is challenging to study how these proteins are trafficked through the cytoplasm and reach the nucleus, as this is a complex process, and any disturbance to the process in an in vitro system may generate artifacts. We adopted a split-GFP approach to visualize VirE2 in a natural setting (24), which made it possible to monitor intracellular trafficking of the virulence factor VirE2 in real time.

VirE2 affects the fate of T-DNA in many ways (41). Therefore, it is important to determine how VirE2 is trafficked through the cytoplasm and reaches the nucleus. VirE2 contains two bipartite NLS signals (21), which are present on the exterior side of the solenoidal structure (19). This structural arrangement may make the NLS signals available to interact with other host factors. When the NLS of VirE2 was mutated to be recognizable in animal cells, the “animalized” VirE2 was found to migrate along microtubules in cell-free Xenopus oocyte extracts, propelled by dynein motors (29). However, no plant dyneins have been found (31). It remains unknown whether VirE2 moves along microtubules in plant cells. Therefore, the trafficking of “animalized” VirE2 in animal cells may not accurately represent the mechanism of VirE2 trafficking inside plant cells. Moreover, disruption of microtubules by Colc did not affect the VirE2 trafficking significantly (Fig. 1D). This suggests that VirE2 uses a transport system other than microtubules when trafficked inside plant cells. Our study showed that Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 was trafficked via the ER and F-actin network. The VirE2-associated T-complex may also use the same trafficking mode, as VirE2 can coat the surface of the T-complex.

Our study also showed that VirE2 trafficking may require the plant-specific myosin XI family and XI-K in particular. Myosin XI family members are involved in cytoplasmic streaming (42), ER motility (38), and trafficking of organelles and vesicles (40). Despite the conformational similarities with myosin V, myosin XI has a plant-specific binding mechanism (43) and thus recognizes different cargos than myosin V. This study may provide an explanation for the very significant difference in transformation efficiency between yeast and plant recipients (0.2% in Saccharomyces cerevisiae vs. 100.0% in N. benthamiana). The efficiency of protein delivery is comparable between yeasts and plants (50.9% in S. cerevisiae vs. 100.0% in N. benthamiana) (24). The budding yeast S. cerevisiae lacks myosin XI-K, which would render VirE2 immobile in the yeast cells. Thus, the transformation efficiency is significantly reduced. Our study demonstrated that myosin XI-K played a much more critical role in VirE2 trafficking than XI-2. XI-K and XI-2 are highly expressed inside plant cells (44). However, myosin XI-K is the primary contributor to ER streaming (38).

We hypothesize that Agrobacterium has evolved to enable VirE2 to exploit ER streaming, which is part of the cytoplasmic streaming process. Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 was associated with ER (Fig. 2B and Movie S7), probably because of the high affinity of VirE2 for membranes (45). However, it is possible that an unknown factor(s) is responsible for the VirE2–ER association. The VirE2-associated ER is thus driven primarily by the ER-associated myosin XI-K. The myosin-associated ER can move along actin filaments. Therefore, Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 is trafficked through plant cells via the myosin-powered ER/actin network, because of the dynamic three-way interactions among ER, F-actin, and myosin (38). Currently, it is not clear which part of VirE2 is necessary for VirE2 movement. This is an interesting topic for future studies.

The ER stretches through the entire cytoplasm and continues to the outer membrane of the nucleus, which may provide VirE2 with a convenient path to reach the nucleus. Cytosolic facing of VirE2 on the ER seems to make the opening of the nuclear pore complex accessible for nuclear import of VirE2. Moreover, the association of VirE2 with ER also suggests that VirE2 may interact with other factors during the trafficking processes. Indeed, a SNARE-like protein was found to have a strong interaction with VirE2 (46). It has also been reported that reticulon-domain proteins and a Rab GTPase, both involved in trafficking of proteins through endomembranes, are important for transformation (47). These findings suggest that vesicular budding or fusion processes may be involved in VirE2 trafficking inside the cytoplasm.

Currently, it is still not clear whether other bacterial virulence proteins delivered by Agrobacterium are trafficked along with VirE2. It remains to be determined how other bacterial virulence proteins are trafficked inside host cells upon the delivery. These issues should be examined in future studies, which could provide new insights into the transformation process.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Plasmids, Primers, and Growth Conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. A. tumefaciens strains were grown at 28 °C in mannitol glutamate/lysogeny (MG/L) medium. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for plasmid construction and was cultured at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB) medium.

Table S1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain and plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source |

| A. tumefaciens | ||

| EHA105 | C58 strain containing pTiBo542 harboring the vir genes but not T-DNA | Ref. 48 |

| EHA105virE2::GFP11 | EHA105 derivative, with the GFP11-coding sequence inserted into virE2 on pTiBo542 at 162 bp downstream from ATG+1 | Ref. 24 |

| EHA105virE2::GFP11nls1 | EHA105virE2::GFP11 derivative, with the first NLS residues, 221KLR. . .KYGRR237, replaced with alanine | Ref. 24 |

| A348 | A136 (pTiA6NC) (Octopine-type) | Ref. 49 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pQH308A | The GFP1-10 coding sequence was inserted to replace Bar in pDs-Lox. The resulting cassette Pmas:GFP1-10:Tnos was PCR amplified and inserted at ClaI-HindIII site of pBI121; A DsRed ORF was inserted at XbaI-BamHI site of pBI121 downstream of the 35S promoter. | Ref. 24 |

| pER-rk | Binary plasmid that encodes the ER-localized mCherry | Ref. 36 |

| pQH308ER | The coding sequence of DsRed on pQH308A was replaced by a sequence of ER-mCherry cloned from pER-rk | This study |

| pQH307A | The coding sequence of DsRed on pQH308A was removed | This study |

| pCB302 | Mini binary vector with 35S promoter | Ref. 50 |

| pCB302-XIK-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin XI-K tail fragment starting from Ala731. | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-XI2-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin XI-2 tail fragment starting from Val735 | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-XIF-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin XI-F tail fragment starting from Ile740 | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-VIII1-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin VIII1 tail fragment starting from Thr827 | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-VIII2-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin VIII2 tail fragment starting from Glu864 | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-VIIIB-IQC | pCB302 expressing the myosin VIIIB tail fragment starting from Val831 | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-dsXIK | pCB302 expressing the RNAi construct covering nts 3,153–3,357 in the myosin XI-K ORF | Ref. 40 |

| pCB302-dsXI2 | pCB302 expressing the RNAi construct covering nts 3,146–3,375 in the myosin XI-2 ORF | Ref. 40 |

| pB5tdGW-ABD2 | Binary plasmid that encodes a tdTomato-fusion actin binding domain | Ref. 37 |

| pH7WGR2-RFP-MBD | Binary plasmid that encodes a RFP-fusion microtubule binding domain | Ref. 51 |

| pBI121 | Binary vector with 35S promoter and a CDS of Gus-A | Ref. 52 |

| pQH121 | pBI121 that the CDS of Gus-A is replaced by a multiple cloning site | This study |

| pQH121-ER-GFP1-10 | pQH121 that encodes GFP1-10 fused with ER targeting signal at the N terminus and an HDEL ER-retention signal at the C terminus | This study |

| pQH121-2×GFP11 | pQH121 that encodes two tandem GFP11 | This study |

| pQH121-ER-2×GFP11 | pQH121 that encodes two tandem GFP11 fused with ER targeting signal at the N terminus and an HDEL ER-retention signal at the C terminus | This study |

Virulence Assays.

A. thaliana root transformation was performed as described previously (24). In brief, the roots of 10-d-old seedlings were cut into 3–5-mm segments. These segments were infected by tumor-inducing A. tumefaciens A348 for 2 d. They were then transferred onto solid Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates for growth. Tumors were photographed after 4 wk.

N. benthamiana leaves were surface-sterilized with 0.5% NaClO and punctured into discs. The leaf discs were resuspended into 1/2× MS medium containing A348 cells at a concentration of 1 × 108 cells per milliliter. The leaf discs were aligned onto a 1/2× MS plate and incubated at 25 °C for 2 d. The leaf discs were then transferred onto another 1/2× MS plate supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 cefotaxime and kept at 25 °C for 2 wk before photography.

Agroinfiltration.

To visualize Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2, agroinfiltration was performed as described previously (24). In brief, the bacteria were grown overnight; the cultures were diluted 50 times in MG/L and grown for 6 h. The bacteria were collected and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Mes, pH 5.5) at an OD600 of 1.0. The bacterial suspension was infiltrated by using a syringe to the underside of fully expended N. benthamiana leaves. The infiltrated plant was kept in a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark at 25 °C.

mRNA Detection with Quantitative RT-PCR.

The total RNA from plants used in each treatment was extracted and reverse-transcribed by using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in triplicates with KAPA SYBRs on a CFX384 PCR system (Bio-Rad) by using the actin gene as an internal control (5′-CTTGAAACAGCAAAGACCAGC-3′ and 5′-GGAATCTCTCAGCACCAATGG-3′). Gene-specific primers for qRT-PCR are as follows: 5′-TCGTTTCGGTAAGTTTGTGG-3′ and 5′-CATTGCCCTTCTTGTAGCC-3′ for the N. benthamiana myosin XI-2 gene (GenBank accession no. DQ875135.1) and 5′-GAATCAGTGAGGAAGAGCAGG-3′ and 5′-CCGTCATATTGAGATGAAATCG-3′ for the N. benthamiana myosin XI-K gene (GenBank accession no. DQ875137.1).

Confocal Microscopy.

A PerkinElmer UltraVIEW VoX spinning-disk system with EM-CCD camera and an Olympus objective was used for confocal microscopy. To observe leaf epidermises, agroinfiltrated leaf tissues were detached from N. benthamiana plants and placed in 2% (wt/vol) low-melting agarose gel on a glass slide with a coverslip. All images were taken in multiple focal planes (i.e., Z-stacks), and were processed to show the extended focus image or the 3D opacity view by using Volocity 3D Image Analysis software 6.2.1.

SI Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction.

Binary plasmids harboring a T-DNA region that encodes a GFP1-10 expression cassette or a GFP1-10 and ER-mCherry dual cassette were constructed and used to generate transgenic N. benthamiana lines. Plasmid pQH308A (24) was digested with XbaI and SacI to remove the coding sequence for DsRed, and was religated to produce pQH307A. The coding sequence of ER-mCherry from pER-rk (36) was cloned into the XbaI-SacI site of pQH308A, replacing DsRed, resulting in pQH308ER.

Generation of Transgenic N. benthamiana Lines.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of N. benthamiana plants was performed by using leaf sections. Transgenic calli were generated on MS media supplemented with 100 mg L−1 kanamycin, 2 mg L−1 6-benzylaminopurine (BA), and 0.2 mg L−1 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA). Transgenic plantlets were obtained by transferring calli with shoots into 1/2× MS plates supplemented with 0.1 mg L−1 indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). Transgenic lines were named Nb307A and Nb308ER to reflect the corresponding binary plasmids pQH307A and pQH308ER, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Valerian V. Dolja (Oregon State University) for providing N. benthamiana myosin-related constructs, Prof. Ikuko Hara-Nishimura (Kyoto University) for providing the construct of the F-actin marker, and Prof. Danny Geelen (Ghent University) for providing the construct of the microtubule marker, Ms. Yan Tong for technical assistance, and Nadiya Farah for reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by Singapore Ministry of Education Grants R-154-000-588-112 and R-154-000-685-112 and Singapore Millennium Foundation Grant R-154-000-586-592.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612098114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chilton MD, et al. Stable incorporation of plasmid DNA into higher plant cells: The molecular basis of crown gall tumorigenesis. Cell. 1977;11(2):263–271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zambryski P, et al. Tumor DNA structure in plant cells transformed by A. tumefaciens. Science. 1980;209(4463):1385–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.6251546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albright LM, Yanofsky MF, Leroux B, Ma DQ, Nester EW. Processing of the T-DNA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens generates border nicks and linear, single-stranded T-DNA. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(3):1046–1055. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1046-1055.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fronzes R, Christie PJ, Waksman G. The structural biology of type IV secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(10):703–714. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bundock P, den Dulk-Ras A, Beijersbergen A, Hooykaas PJ. Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14(13):3206–3214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piers KL, Heath JD, Liang X, Stephens KM, Nester EW. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(4):1613–1618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Groot MJ, Bundock P, Hooykaas PJ, Beijersbergen AG. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of filamentous fungi. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16(9):839–842. doi: 10.1038/nbt0998-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathiresan S, Chandrashekar A, Ravishankar GA, Sarada R. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis (Chlorophyceae, Volvocales) J Phycol. 2009;45(3):642–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Herrera-Estrella L, Van Montagu M, Zambryski P. Right 25 bp terminus sequence of the nopaline T-DNA is essential for and determines direction of DNA transfer from agrobacterium to the plant genome. Cell. 1984;38(2):455–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanofsky MF, et al. ThevirD operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens encodes a site-specific endonuclease. Cell. 1986;47(3):471–477. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrera-Estrella A, Chen ZM, Van Montagu M, Wang K. VirD proteins of Agrobacterium tumefaciens are required for the formation of a covalent DNA--protein complex at the 5′ terminus of T-strand molecules. EMBO J. 1988;7(13):4055–4062. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergunst AC, et al. VirB/D4-dependent protein translocation from Agrobacterium into plant cells. Science. 2000;290(5493):979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrammeijer B, den Dulk-Ras A, Vergunst AC, Jurado Jácome E, Hooykaas PJ. Analysis of Vir protein translocation from Agrobacterium tumefaciens using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model: Evidence for transport of a novel effector protein VirE3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(3):860–868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vergunst AC, et al. Positive charge is an important feature of the C-terminal transport signal of the VirB/D4-translocated proteins of Agrobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(3):832–837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406241102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engström P, Zambryski P, Van Montagu M, Stachel S. Characterization of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence proteins induced by the plant factor acetosyringone. J Mol Biol. 1987;197(4):635–645. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Citovsky V, DE Vos G, Zambryski P. Single-stranded DNA binding protein encoded by the virE locus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science. 1988;240(4851):501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4851.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen P, Pazour GJ, Anderson D, Das A. Cooperative binding of Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirE2 protein to single-stranded DNA. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(5):2573–2580. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2573-2580.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citovsky V, Wong ML, Zambryski P. Cooperative interaction of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein with single-stranded DNA: Implications for the T-DNA transfer process. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(4):1193–1197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dym O, et al. Crystal structure of the Agrobacterium virulence complex VirE1-VirE2 reveals a flexible protein that can accommodate different partners. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(32):11170–11175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801525105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Citovsky V, Warnick D, Zambryski P. Nuclear import of Agrobacterium VirD2 and VirE2 proteins in maize and tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(8):3210–3214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Citovsky V, Zupan J, Warnick D, Zambryski P. Nuclear localization of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein in plant cells. Science. 1992;256(5065):1802–1805. doi: 10.1126/science.1615325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelvin SB. Agrobacterium VirE2 proteins can form a complex with T strands in the plant cytoplasm. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(16):4300–4302. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4300-4302.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Y, Lee LY, Gelvin SB. Is VIP1 important for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation? Plant J. 2014;79(5):848–860. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Yang Q, Tu H, Lim Z, Pan SQ. Direct visualization of Agrobacterium-delivered VirE2 in recipient cells. Plant J. 2014;77(3):487–495. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luby-Phelps K. Cytoarchitecture and physical properties of cytoplasm: Volume, viscosity, diffusion, intracellular surface area. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;192:189–221. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzfira T. On tracks and locomotives: The long route of DNA to the nucleus. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14(2):61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzfira T, Vaidya M, Citovsky V. VIP1, an Arabidopsis protein that interacts with Agrobacterium VirE2, is involved in VirE2 nuclear import and Agrobacterium infectivity. EMBO J. 2001;20(13):3596–3607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djamei A, Pitzschke A, Nakagami H, Rajh I, Hirt H. Trojan horse strategy in Agrobacterium transformation: Abusing MAPK defense signaling. Science. 2007;318(5849):453–456. doi: 10.1126/science.1148110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salman H, et al. Nuclear localization signal peptides induce molecular delivery along microtubules. Biophys J. 2005;89(3):2134–2145. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakalis PA, van Heusden GP, Hooykaas PJ. Visualization of VirE2 protein translocation by the Agrobacterium type IV secretion system into host cells. Microbiology Open. 2014;3(1):104–117. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence CJ, Morris NR, Meagher RB, Dawe RK. Dyneins have run their course in plant lineage. Traffic. 2001;2(5):362–363. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.25020508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasteneys GO. Microtubule organization in the green kingdom: Chaos or self-order? J Cell Sci. 2002;115(pt 7):1345–1354. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krucker T, Siggins GR, Halpain S. Dynamic actin filaments are required for stable long-term potentiation (LTP) in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6856–6861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100139797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misumi Y, et al. Novel blockade by Brefeldin A of intracellular transport of secretory proteins in cultured rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(24):11398–11403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skoufias DA, Wilson L. Mechanism of inhibition of microtubule polymerization by colchicine: Inhibitory potencies of unliganded colchicine and tubulin-colchicine complexes. Biochemistry. 1992;31(3):738–746. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 2007;51(6):1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakano RT, et al. GNOM-LIKE1/ERMO1 and SEC24a/ERMO2 are required for maintenance of endoplasmic reticulum morphology in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21(11):3672–3685. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ueda H, et al. Myosin-dependent endoplasmic reticulum motility and F-actin organization in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(15):6894–6899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911482107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitoh M, Ishikawa T, Matsushima S, Naka M, Hidaka H. Selective inhibition of catalytic activity of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(16):7796–7801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avisar D, Prokhnevsky AI, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Dolja VV. Myosin XI-K is required for rapid trafficking of Golgi stacks, peroxisomes, and mitochondria in leaf cells of Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(3):1098–1108. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ward DV, Zambrysk iPC. The six functions of Agrobacterium VirE2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(2):385–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokota E, Yukawa C, Muto S, Sonobe S, Shimmen T. Biochemical and immunocytochemical characterization of two types of myosins in cultured tobacco bright yellow-2 cells. Plant Physiol. 1999;121(2):525–534. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li JF, Nebenführ A. Organelle targeting of myosin XI is mediated by two globular tail subdomains with separate cargo binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20593–20602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peremyslov VV, et al. Expression, splicing, and evolution of the myosin gene family in plants. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(3):1191–1204. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.170720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumas F, Duckely M, Pelczar P, Van Gelder P, Hohn B. An Agrobacterium VirE2 channel for transferred-DNA transport into plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(2):485–490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011477898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee LY, et al. Screening a cDNA library for protein-protein interactions directly in planta. Plant Cell. 2012;24(5):1746–1759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.097998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang HH, Gelvin SB. Plant proteins that interact with VirB2, the Agrobacterium tumefaciens pilin protein, mediate plant transformation. Plant Cell. 2004;16(11):3148–3167. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hood EE, Gelvin SB, Melchers LS, Hoekema A. New Agrobacterium helper plasmids for gene transfer to plants. Transgenic Res. 1993;2(4):208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knauf VC, Nester EW. Wide host range cloning vectors: A cosmid clone bank of an Agrobacterium Ti plasmid. Plasmid. 1982;8(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang C, Han P, Lutziger I, Wang K, Oliver DJ. A mini binary vector series for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40(4):711–717. doi: 10.1023/a:1006201910593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Damme D, et al. In vivo dynamics and differential microtubule-binding activities of MAP65 proteins. Plant Physiol. 2004;136(4):3956–3967. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.051623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen PY, Wang CK, Soong SC, To KY. Complete sequence of the binary vector pBI121 and its application in cloning T-DNA insertion from transgenic plants. Mol Breed. 2003;11(4):287–293. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.