Significance

Cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes a chloride channel located in the apical membrane of epithelia cells. The cAMP signaling pathway and protein phosphorylation are known to be primary controlling mechanisms for channel function. In this study, we present an alternative activation pathway that involves calcium-activated calmodulin binding of the intrinsically disordered regulatory (R) region of CFTR. Beyond their potential therapeutic value, these data provide insights into the intersection of calcium signaling with control of ion homeostasis and the ways in which the local CFTR microdomain organizes itself.

Keywords: calmodulin, cystic fibrosis, NMR, phosphorylation, membrane potential assay

Abstract

Cystic fibrosis results from mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel, leading to defective apical chloride transport. Patients also experience overactivation of inflammatory processes, including increased calcium signaling. Many investigations have described indirect effects of calcium signaling on CFTR or other calcium-activated chloride channels; here, we investigate the direct response of CFTR to calmodulin-mediated calcium signaling. We characterize an interaction between the regulatory region of CFTR and calmodulin, the major calcium signaling molecule, and report protein kinase A (PKA)-independent CFTR activation by calmodulin. We describe the competition between calmodulin binding and PKA phosphorylation and the differential effects of this competition for wild-type CFTR and the major F508del mutant, hinting at potential therapeutic strategies. Evidence of CFTR binding to isolated calmodulin domains/lobes suggests a mechanism for the role of CFTR as a molecular hub. Together, these data provide insights into how loss of active CFTR at the membrane can have additional consequences besides impaired chloride transport.

In airway epithelia, transport of chloride into the lumen of the airways is followed by water movement and allows normal clearance of the respiratory system to prevent lung infections. This chloride flux is maintained by cAMP-activated cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (1) and calcium ion-activated chloride channels (CaCCs); the separation between activation pathways of these channels was recently questioned, however (2, 3). In cystic fibrosis (CF), a disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, lack of normal fluid transport results in a dehydrated airway surface liquid (ASL) layer that leads to mucus accumulation and frequent lung infections. Calcium signaling is the major regulatory pathway of airway physiology because increased intracellular calcium is the primary signal for fluid secretion (4). Despite early investigations finding no evidence for calcium signaling directly activating CFTR (5), recent studies have focused on the interplay between the cAMP and calcium pathways in CFTR activation and function (6, 7), including the role of protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation on CFTR activation and PKA activation by calcium-activated adenylate cyclases (8).

CFTR activation by the cAMP pathway is well established in the literature (9–11). Together with ATP binding by the nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), phosphorylation of NBD1 and the 200-residue regulatory (R) region facilitates CFTR trafficking and channel opening (1, 2, 12, 13). R region is an intrinsically disordered segment of the CFTR that samples multiple conformations under physiological conditions. It is responsible for most of CFTR’s regulatory intramolecular and intermolecular protein–protein interactions (14). Diverse binding elements of R region for various partners are conserved and controlled by phosphorylation. Nonphosphorylated R region interacts with NBD1 via helical elements, whereas PKA-phosphorylated R region loses helical propensity and binds to 14-3-3 via shorter extended segments. Because these binding segments are accessible and largely independent from each other, R region can interact with more than one partner at a time. Consequently, it can integrate different regulatory inputs via transient, dynamic interactions (14).

CFTR is located on the apical surface of epithelial cells and is a key component of a macromolecular signaling complex that involves sodium and potassium channels, anion exchangers, transporters, and other regulator proteins and molecules (11). Store operated calcium channel Orai1 was also found in the same microdomain (15); because mutations in CFTR affect Orai1 channel function (15), Orai1 is likely to be part of the same complex. Interaction between endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) and Orai1 form a membrane contact site, a critical junction between the ER and plasma membrane. This STIM1:Orai1 interaction activates the store operated calcium entry (16) and localizes ER and plasma membrane calcium channels in close proximity to CFTR, resulting in local elevation of calcium levels. Calcium-regulated interaction between CFTR and other membrane proteins is thus very likely. One recent example demonstrates that the potassium channel KCa3.1 interacts with CFTR in a calcium-dependent manner (17).

Calcium signaling is tightly coupled to calmodulin, a multifunctional intermediate messenger that translates calcium signals to regulatory calcium-dependent protein–protein interactions with various targets (18, 19). It consists of two lobes, each with two calcium-binding EF-hand motifs, and a connecting linker region (20). Calmodulin recognizes very diverse substrate sequences categorized (e.g., IQ, 1–10, 1–14, and 1–16 motif classes) based on key residues of the interaction (21, 22). Moreover, it can interact with its partners in two different binding conformations (23). In the canonical binding mode, calmodulin wraps around the substrate with high (nanomolar) affinity (24), whereas in the alternative binding conformation the two lobes can bind to two separate sequences independently and bridge over larger distances, usually with weaker (micromolar) affinity (25–27). Most calmodulin substrates use the canonical interaction mode, but, interestingly, membrane channels such as the calcium channel Orai1 (25), the sodium channel NaV1.5 (26), and the potassium channel Kv7.1 (27) use the alternative calmodulin-binding mode.

In this study, we investigated the direct effect of calcium signaling on CFTR, focusing on the consequences of calmodulin binding for CFTR activation and function. We demonstrate that calmodulin interacts directly with the R region of CFTR in a calcium- and phosphorylation-dependent manner with ∼25 µM affinity. Calcium-loaded calmodulin binding and PKA phosphorylation at three phosphorylation sites are mutually exclusive processes. Imaging on both primary tissue and cells overexpressing CFTR and calmodulin shows that the two proteins colocalize at the apical membrane. Patch-clamp experiments provide evidence that calcium-loaded calmodulin triggers an open probability similar to that observed for PKA phosphorylation, suggesting that calmodulin binds directly to full-length CFTR. We found that both wild-type and F508del CFTR can be activated by increased intracellular calcium level in a cellular context in the absence of PKA stimulation. Interestingly, following PKA stimulation, intracellular calcium release decreases the activity of wild-type CFTR, whereas F508del CFTR function can be further activated by elevated level of calcium, a difference that we attribute to the likely different phosphorylation states of the two proteins. Calmodulin-binding–deficient R-region mutant CFTR displayed a decreased response to calmodulin. Results of single-lobe calmodulin experiments and measured binding affinities are consistent with calmodulin acting as a binding bridge to other components of calcium signaling pathways. Thus, CFTR activity may also be regulated by large calmodulin-containing macromolecular complexes involved in cellular ion homeostasis. Together, these results open avenues for treatment of CF, synergize the cAMP and calcium signaling regulatory pathways for CFTR, and deepen our understanding of how CFTR activation is tuned by different internal and external stimuli.

Results

The R Region of CFTR Binds to Calmodulin.

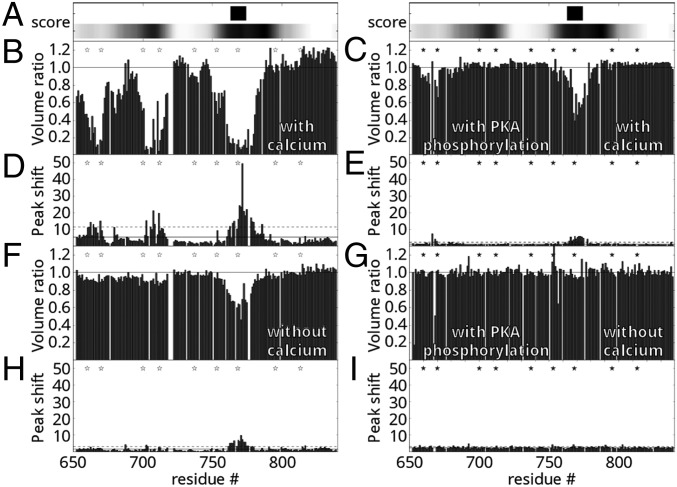

Given the roles of CFTR in regulation of multiple channels and the known importance of the R region as a protein interaction hub, we used a variety of computational approaches to predict protein-binding sites within the R region and to identify partners for experimental studies. Prediction of calmodulin-binding sites using CaMBTPredictor (28) identified a minor and a major binding segment centered at residues 705 and 780, respectively, and recognition motif search using Calmodulin Target Database (22) found an IQ-like motif (with a conservative I/L substitution in the IQ motif: IQXXXR) between residues 763 and 774, which contains the S768 phosphorylation site (29, 30) (Fig. 1A). To experimentally characterize the R-region–calmodulin interaction, we performed nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) proton–nitrogen–carbonyl triple resonance (HNCO) experiments on isolated human R region (amino acids 654–838; F833L, a polymorphism with enhanced solubility, 13C15N-labeled) in the presence and absence of unlabeled human calmodulin (amino acids 1–149; Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Many known IQ motifs are calcium-independent binding motifs (21). Thus, we compared spectra with and without 40 μM free calcium ions (Materials and Methods). Because the predictions included phosphorylation sites, we also investigated the phosphorylation dependence of the interaction. Comparison of R-region HNCO spectra shows that calmodulin addition leads to significant changes of NMR resonance intensities and chemical shifts, providing evidence for R-region–calmodulin interactions. Furthermore, the interaction strength is modulated by both calcium and R-region phosphorylation. Three segments of the nonphosphorylated R region (amino acids 659–671, 700–715, and 760–780) display significant decrease in signal intensity in the presence of calcium-loaded calmodulin (Fig. 1 B and D). In the absence of added calcium (Fig. 1 F and H) or when R region is PKA-phosphorylated (Fig. 1 C and E), primarily one of these sites (amino acids 760–780) has reduced signal upon calmodulin addition. Furthermore, the signal loss is decreased, indicative of significantly weaker interaction. Based on chemical shift changes, the binding affinity of the amino acids 760–780 site is the strongest among the three segments. These chemical shifts decrease by over an order of magnitude in the absence of calcium or with PKA phosphorylation. No signal loss is observed upon addition of calmodulin to PKA-phosphorylated R region in the absence of calcium (Fig. 1 G and I). The intrinsically disordered R region samples various conformations, but published NMR chemical shift data indicate that the three calmodulin-binding segments have a significant amount of helical character, even without a partner (31). Binding of calcium-loaded calmodulin to nonphosphorylated R region causes the chemical shifts of these segments to move closer to values consistent with α-helical structure (Fig. S2), indicating a coil-to-helix transition. This evidence that the segments assume a helical conformation when bound to calmodulin is in good agreement with previous structural studies showing that calmodulin recognizes most of its partners in a helical conformation.

Fig. 1.

Predicted and experimental calmodulin interaction profile of human R region of CFTR. (A) Calmodulin-binding site prediction using (Top) the motif search algorithm of the calmodulin target database (22) identifying an IQ-like motif at residues 736–773 and (Bottom) the residue-specific interaction prediction of CaMBTPredictor (28). Shading correlates with higher predicted value. (B–I) NMR evidence for direct calmodulin binding to the CFTR R region. (B, C, F, and G) Peak volume ratios and (D, E, H, and I) combined 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shift changes (in hertz) with and without calmodulin in the (B–E) presence and (F–I) absence of free calcium ions. Peak volume ratios lower than 1 represent R-region segments that experience direct or indirect effects of the interaction. Stars represent PKA phosphorylation sites on R region in the nonphosphorylated (empty stars; B, D, F, and H) and PKA-phosphorylated state (solid stars; C, E, G, and I).

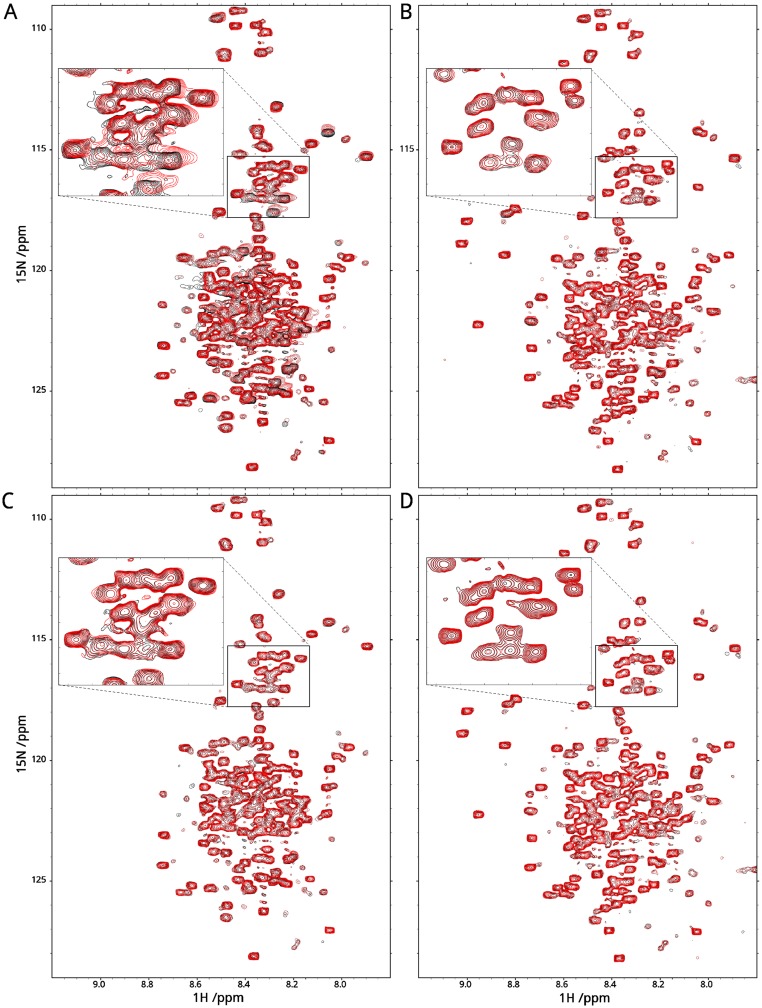

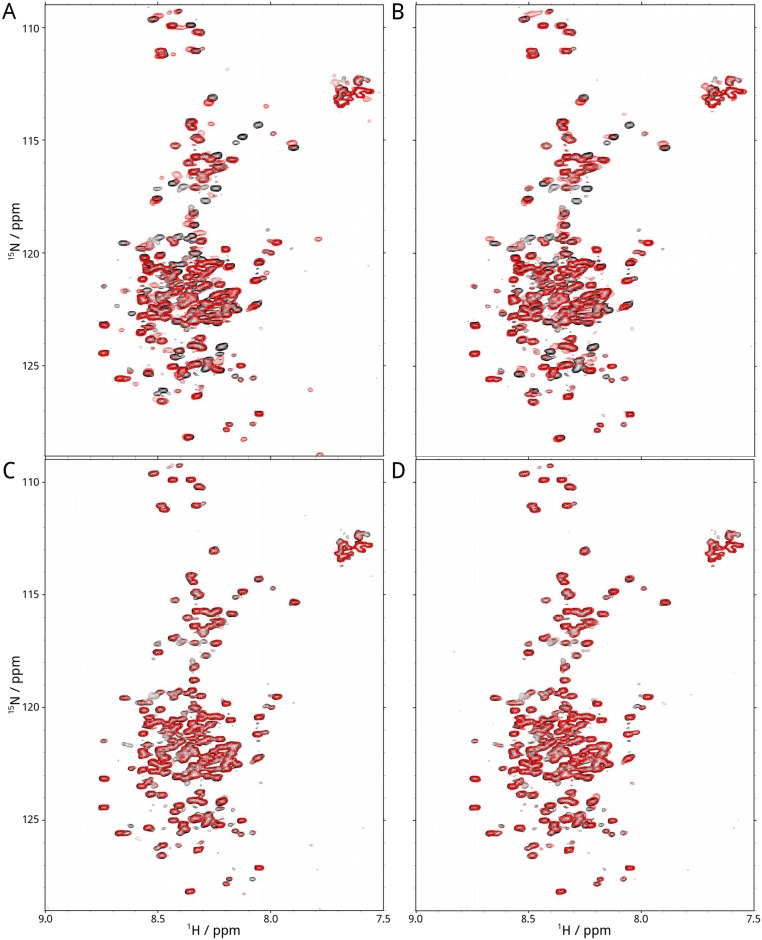

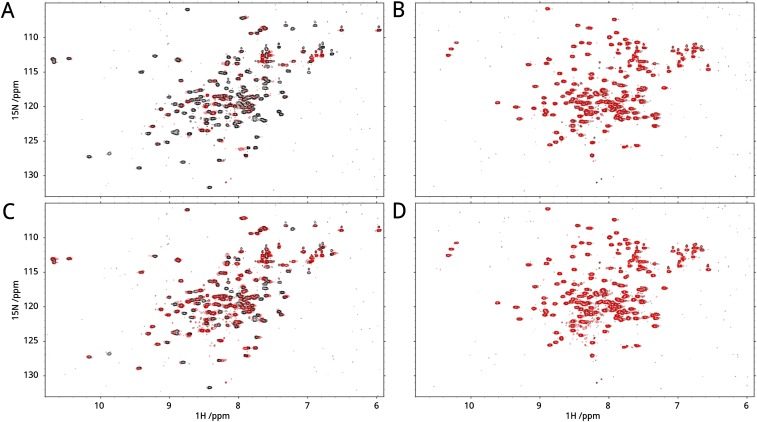

Fig. S1.

NMR spectra of R region in complex with calmodulin. Overlay of proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) of 15N-labeled nonphosphorylated (A and B) and PKA-phosphorylated (C and D) R region with (red) and without (black) calmodulin in the presence (A and C) or absence (B and D) of free calcium ions.

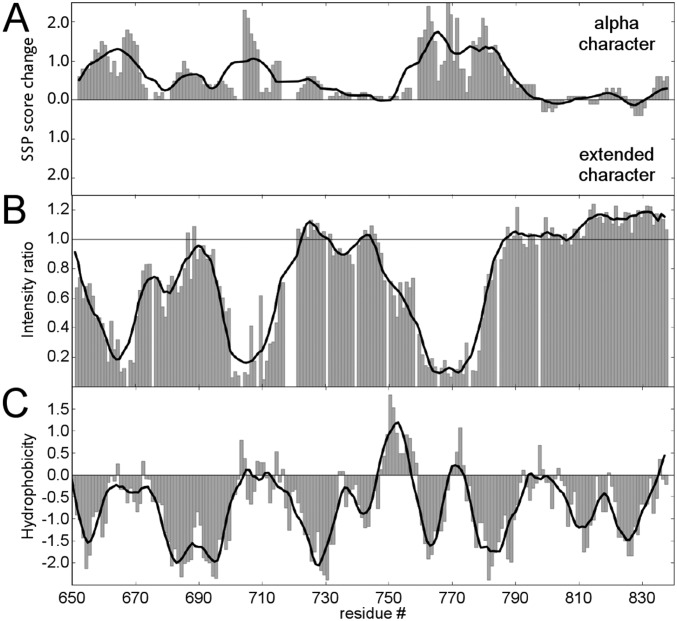

Fig. S2.

R-region chemical shifts move toward more α character upon binding. (A) Percent increase of R-region secondary structure propensity (SSP) (calculated from 13CO and 15N chemical shifts) upon binding to calmodulin (bar graph). Positive values correspond to increased α-helical character and negative values correlate with more extended conformations in the complex. Trend line (black) is calculated using a Savitzky–Golay noise filter with a window size of 21 residues. (B) R-region–binding profile as shown in Fig. 1B (bar graph). Trend line is calculated the same way as in A. (C) Hydrophobicity plot calculated based on Kyte and Doolittle (50).

R Region Prefers Alternative Calmodulin-Binding Mode.

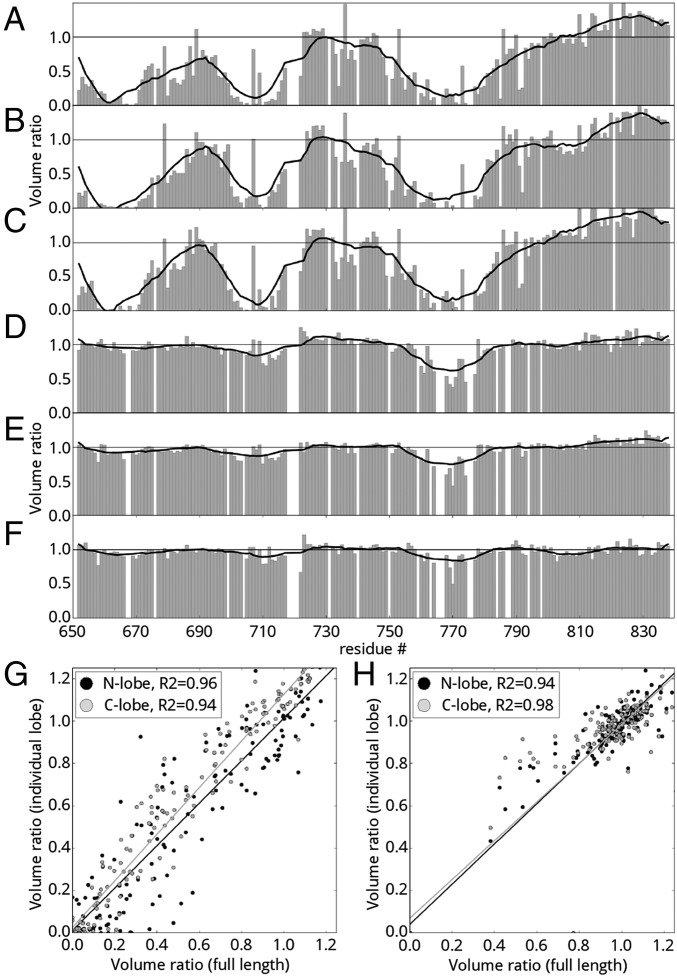

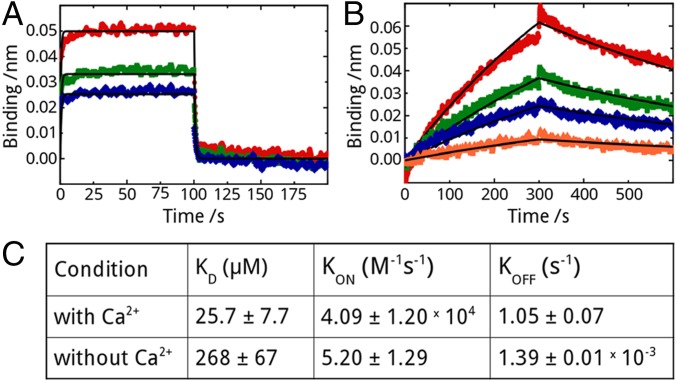

Because calmodulin interacts with its substrates in two major modes, the canonical clamping mode and the alternative bridging mode (Fig. S3A), we investigated binding of R region to isolated calmodulin lobes using NMR. R-region HNCO spectra were measured with and without full-length, N-terminal or C-terminal lobes of calmodulin in the presence (Fig. 2 A–C and Fig. S4 A and B) or absence (Fig. 2 D–F and Fig. S4 C and D) of calcium ions. Interactions of full-length calmodulin and individual lobes display very similar peak intensity change trends and the degree of intensity change with full-length versus N or C lobe are positively correlated with correlation coefficients higher than 0.94 (Fig. 2 G and H) under conditions expected to saturate binding. Because the canonical binding mode requires simultaneous binding of both lobes, these data indicate that individual lobes are sufficient for the interaction and that the alternative binding mode is operative. We used biolayer interferometry (BLI) to measure the kinetic parameters and the binding constants of the calmodulin–R-region interaction in the presence and absence of calcium (Fig. 3). R region has a binding affinity of 25.7 ± 7.7 µM for calcium-loaded calmodulin, whereas lack of calcium weakens this interaction by more than an order of magnitude. The micromolar affinity is consistent with other partners binding calmodulin in the alternative mode (25, 26).

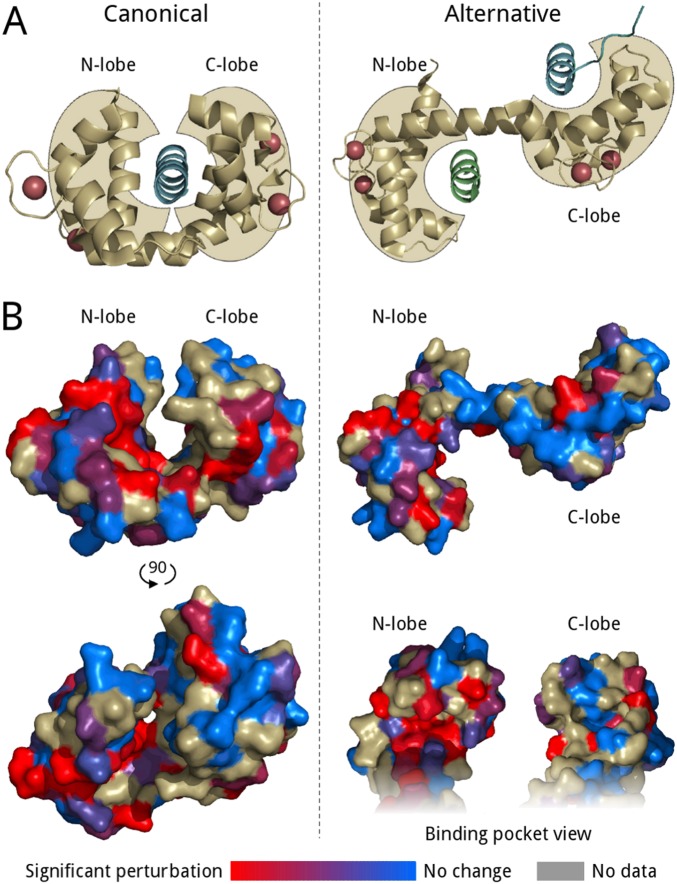

Fig. S3.

Calmodulin-binding modes. (A) Cartoon representation of ligand-bound calcium-loaded calmodulin in canonical (PDB ID code 1CDM; complex with calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II) and alternative (PDB ID code 4EHQ; complex with Orai1) binding modes, with calmodulin in gold and the original ligands in blue. An extra Orai1 helix (green) was modeled into the N-lobe–binding packet to demonstrate the bivalent interaction capability of the alternative binding mode. Calcium ions are shown as red spheres. (B) Surface representation of calmodulin is colored as a red-to-blue gradient according to the response to the interaction calculated from the fit of the proton–nitrogen combined chemical shift perturbations of the titration (Fig. S6). Residues with unresolved HSQC peaks or with significant fitting errors are colored gray.

Fig. 2.

R-region binding to N and C lobes of calmodulin. NMR peak volume ratios (bar graph) for the interaction of the nonphosphorylated R region with full-length (A and D), N lobe (B and E), or C lobe of calmodulin (C and F) in the presence (A–C) and absence (D–F) of calcium. Trend lines (black) are calculated using a Savitzky–Golay smoothing filter with a window size of 25 residues and a third-order fitting polynomial. (G and H) Correlation between the peak volume ratios for binding of full-length calmodulin and individual lobes in the presence (G) and absence (H) of calcium. Linear fit of each dataset and the corresponding Pearson correlation coefficient are presented.

Fig. S4.

R-region NMR spectral changes upon binding of calmodulin lobes. Overlay of proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) using 13C15N-labeled R region without (black) and with (red) N-lobe (A and C) and C-lobe (B and D) calmodulin in the presence (A and B) and absence (C and D) of calcium ions. R-region samples were saturated with twofold excess of calmodulin lobes.

Fig. 3.

R-region–calmodulin kinetic parameters and binding constants. (A) Biolayer interferometry (BLI) data in the presence of calcium using 4.38 μM (blue), 8.75 μM (green), and 17.5 μM (red) calmodulin. (B) BLI data using 8.75 μM (orange), 17.5 μM (blue), 35 μM (green), and 70 μM (red) calmodulin in the absence of calcium. Curve fitting was performed using global fitting, and the best-fitted curves are displayed as a line graph (black). (C) Fitted parameters for dissociation constants (KD values) and on and off rates (KON, KOFF) for both experiments.

Interestingly, all three of the R-region segments identified above are involved in interactions with all three calmodulin constructs (Fig. 2 A–C and Fig. S4 A and B). Together, the results are consistent with the segments being direct binding motifs and with the two lobes being able to substitute for each other. Calmodulin lobes are not identical; therefore, to further characterize the calmodulin-binding mode and get residue-specific binding information, we performed NMR heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) titration experiments on full-length calmodulin (amino acids 1–149, 13C15N-labeled) in the presence of increasing amount of R region (Figs. S5 and S6). Comparison of chemical shifts revealed that hydrophobic residues in the canonical binding pocket are the most sensitive to R region. Notably, the two lobes have different binding behaviors. Residues in the N-terminal lobe have more significant chemical shift changes and respond to lower R-region concentration (Fig. S3B), suggesting a slightly higher affinity. We also performed NMR experiments using 15N-labeled calmodulin and unlabeled R region. These experiments demonstrate that calcium enhances the interaction (Fig. S7B) and that R-region phosphorylation (Fig. S7C) significantly decreases the interaction, such that calmodulin shows no binding to PKA-phosphorylated R region in the absence of added calcium (Fig. S7D).

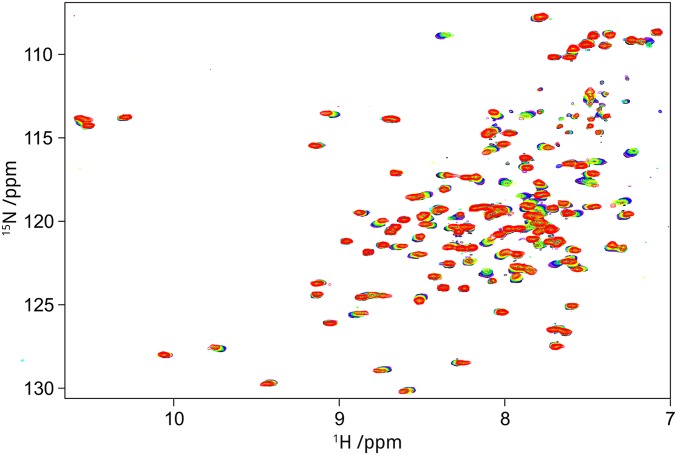

Fig. S5.

NMR spectra of calcium-loaded calmodulin in the presence of various R-region concentrations. Overlay of proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) of 15N-labeled calcium-loaded calmodulin (92 μM) supplemented with 0.00, 0.10, 0.20, 0.45, 0.55, 0.70, and 1.25 molar ratio of R region in black, purple, blue, cyan, green, yellow, and red, respectively.

Fig. S6.

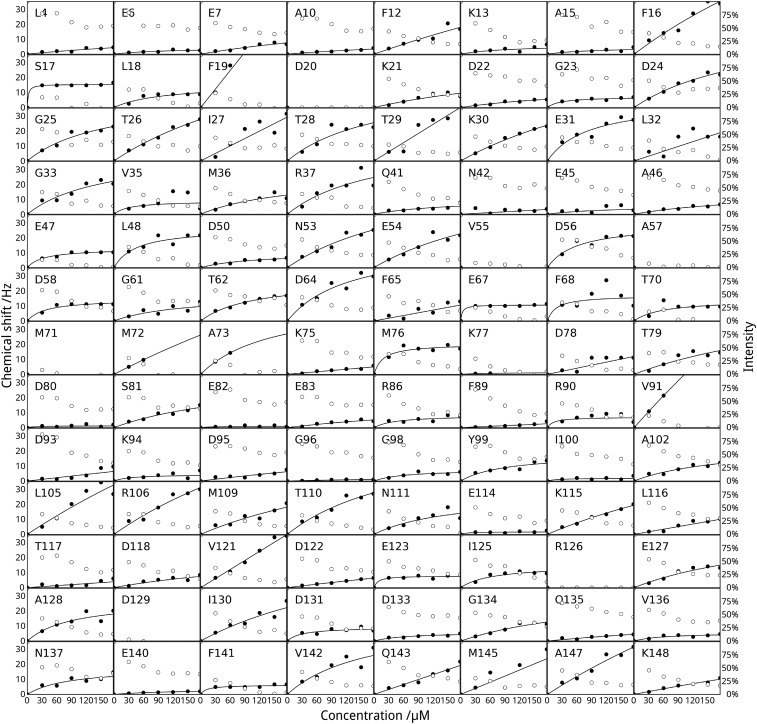

Chemical shift and intensity changes of 13C15N calmodulin HSQC signal upon titration with unlabeled R region. Chemical shifts were calculated as a combined difference of the proton and nitrogen dimensions in hertz (filled circle) and were fitted to calculate the apparent Kd (black line). Signal intensity is shown as a percentage of the original intensity (open circle). Chemical shifts are only presented for the reliable data, that is, for peaks having signal intensities above the noise level.

Fig. S7.

NMR spectra of calmodulin in the presence of R region. Overlay of proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) recorded using 15N-labeled calmodulin without (black) and with (red) nonphosphorylated (A and B) or PKA phosphorylated (C and D) R region in the presence (A and C) and absence (B and D) of calcium ions. Calmodulin samples were saturated with twofold excess of R region.

Calmodulin Modulates R-region Phosphorylation.

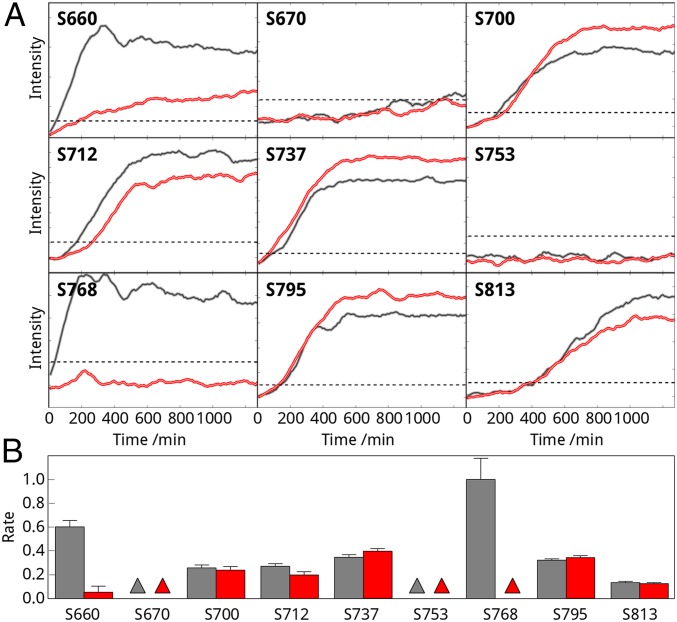

To examine whether calmodulin binding to CFTR affects the ability of PKA to phosphorylate R region, we compared the phosphorylation kinetics of isolated R region in the absence and presence of calcium-loaded calmodulin. We used short HSQC experiments and followed phosphorylation by monitoring peaks corresponding to the phosphorylated S660, S670, S700, S712, S737, S753, S768, S795, and S813 amide groups. Comparison of the kinetic curves (Fig. 4A) for isolated R region revealed that the phosphorylation rate at each site depends only on the correspondence between the primary sequence and the PKA consensus recognition motif. This confirms that the R region is intrinsically disordered without significant stably formed structural elements that might sterically impede PKA phosphorylation. S768 is phosphorylated most quickly, with the best match for the PKA recognition sequence. The phosphorylation rate decreased according to the following order: S768, S660, S737, S795, S712, S700, and S813 (Fig. 4B). No phosphorylation was detected on the two monobasic sites (S670 and S753) during the measurement time (Fig. 4B). Addition of calmodulin and calcium drastically reduces the phosphorylation rate (Fig. 4A) at sites that interact with calmodulin. Consequently, S768 phosphorylation was completely, S660 phosphorylation was largely (8.9-fold), and S712 was significantly (1.2-fold) inhibited by calmodulin (Fig. 4B). The PKA phosphorylation rates at other sites were unchanged or slightly increased (Fig. 4 A and B), probably due to the lower number of accessible substrates for the kinase in this closed system. Interestingly, the similar phosphorylation rate of S700 in the apo and complex form argues that the interaction is dynamic and the second site has the smallest contribution to the complex formation that was compensated by the higher PKA activity. Because PKA phosphorylation of R region directly activates the channel (32), these data imply that calmodulin binding should also have a direct effect on CFTR activity, either inhibiting it or mimicking the effect of phosphorylation and enhancing it.

Fig. 4.

Calmodulin effect on PKA phosphorylation of R region. (A) Individual PKA phosphorylation sites of R region (660, 670, 700, 712, 737, 753, 768, 795, and 813) were followed on proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) upon addition of catalytic subunit of PKA in the presence (red) and absence (gray) of calmodulin. HSCQ spectra were collected every 10 min for 1,260 min consecutively. Therefore, each point represents the phosphorylation level at the start of the 10-min data point. Experimental noise level is indicated by dashed line. (B) Relative phosphorylation rates were calculated from the NMR experiments as a reciprocal of time needed to achieve 50% phosphorylation relative to the maximum reached in the reaction. Rates were normalized to the fastest site (S768) in the absence (gray) and presence (red) of calmodulin. Triangles indicate sites that were not phosphorylated under the experimental conditions during the measurement length. Error bars correspond to the experimental uncertainty.

Increased Intracellular Calcium Enhances CFTR Activity.

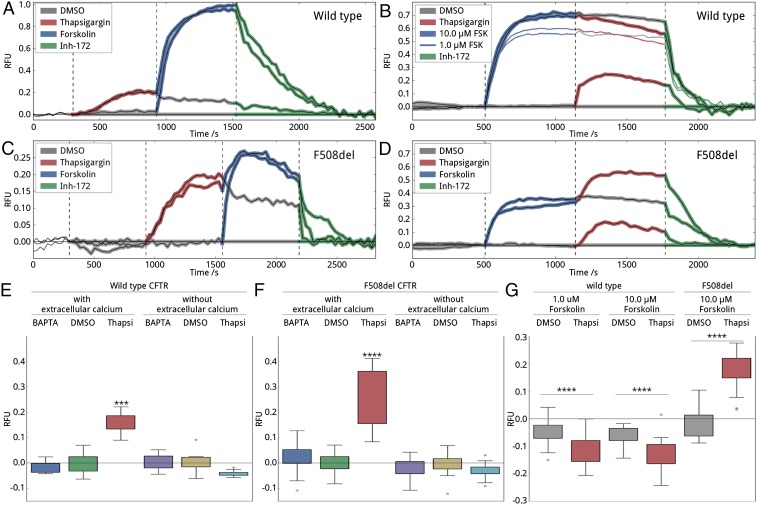

To test these alternative hypotheses and characterize the effect of calcium-loaded calmodulin on full-length CFTR activity, we manipulated the intracellular calcium and cAMP level in HEK-293 cells stably expressing CFTR. Cells with either wild-type or F508del mutant CFTR were used, both pretreated with VX-809 for 24 h to increase cell surface CFTR (33, 34). Channel activity was followed using a membrane potential-sensitive fluorescence dye (FLIPR) developed to monitor ion channel activity (35). Specificity was ensured by testing CFTR inhibitor-172 response. Intracellular calcium concentration and tightly related calmodulin activity were modulated by addition of thapsigargin (a SERCA pump antagonist that causes calcium release from the ER) or 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetra(acetoxymethyl) ester (BAPTA-AM) (a calcium chelator). PKA phosphorylation was initiated using the cAMP agonist, forskolin. This assay was proven to accurately measure CFTR function in previous studies using HEK-293 cells (35) and in our control experiments.

Our in vitro results show that calcium-loaded calmodulin binding and PKA phosphorylation at S660, S712, and S768 are mutually exclusive processes, suggesting that the order of calcium and cAMP signaling may determine which process defines CFTR activity in cells. Thus, in cells, we first tested the effect of sequential addition of thapsigargin followed by forskolin (Fig. 5 A, C, E, and F). Elevation in cytosolic calcium significantly stimulated channel activity in both wild-type and F508del mutant CFTR-expressing cells (Fig. 5 E and F). Addition of the DMSO control or BAPTA-AM had no effect on CFTR function. Following calcium pathway activation by thapsigargin, subsequent forskolin addition further increased CFTR activity. Maximal CFTR activity for both wild-type and F508del CFTR was the same whether or not thapsigargin was applied first (Fig. 5 A and C). More significantly, fully PKA-stimulated or partially PKA- and calcium-stimulated CFTR has the same magnitude of channel activity. Based on our in vitro results and the expectation that calcium release leads to calmodulin binding to the R region, our interpretation of these exciting data is that calmodulin binding mimics R-region phosphorylation in this context and that both have a direct stimulatory effect on CFTR activity with the two processes being roughly additive. Removal of the calcium ions from the extracellular bath eliminates CFTR responses to any treatments affecting intracellular calcium concentration (Fig. 5 E and F), reflecting diminished calcium signaling.

Fig. 5.

CFTR response to calcium. (A–D) Representative traces of wild-type (A and B) and F508del (C and D) CFTR activity in response to addition of DMSO, thapsigargin, and forskolin in various orders, monitored by the FLIPR membrane potential assay. To verify the CFTR-specific response, each experiment included a final treatment with CFTR inhibitor-172. Fluorescence intensities were normalized to the average of four parallel samples receiving only DMSO treatment. Times for the addition of DMSO (gray), thapsigargin (red), forskolin (blue), and CFTR inhibitor-172 (green) are marked by dashed lines. Traces were recorded in a bath containing extracellular calcium ions. (E and F) Box plot representation of wild-type (E) and F508del mutant (F) CFTR peak responses before forskolin treatment as shown in A and C. Cells were incubated in an environment of decreased (BAPTA-AM), basal (DMSO), or increased (thapsigargin) intracellular calcium concentration in the presence or absence of extracellular calcium ions. Each peak response was normalized to the corresponding DMSO peak response. In total, five biological with four technical replicates were measured, and significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. (G) Box plot representation of wild-type and F508del mutant CFTR response after forskolin treatment as presented in B and D. Response was calculated as a difference between the last point of the previous block (forskolin) and the first point of the following block (inhibitor). The results of two forskolin concentrations are displayed for wild-type CFTR to demonstrate that the lack of thapsigargin peak is not due to reaching the fluorescent limit of the assay. Four biological with four technical replicates were measured in each case.

Second, we tested the reverse-order stimulation, enhancement of PKA phosphorylation followed by activation of calcium signaling (Fig. 5 B, D, and G). Interestingly, elevated intracellular calcium levels modestly reduced wild-type but increased F508del CFTR activity (Fig. 5 B and D). Assuming that the activation of channel function by calcium is mediated by calmodulin binding of R region, these data suggest that crucial phosphorylation sites are not fully phosphorylated in F508del CFTR. In contrast, we speculate that, in wild-type CFTR, full phosphorylation at the three critical phosphorylation sites totally abolishes calmodulin-related CFTR activation (Fig. 5B). The modest reduction observed for wild-type CFTR could be explained by internalization of the calcium-activated CFTR. Recent studies have found that calcium-loaded calmodulin initiates endocytosis (36) and cigarette smoke-induced elevation in intracellular calcium levels triggers membrane turnover and therefore decreased CFTR activity (7). We also confirmed the findings using a lower forskolin concentration, to show that the absence of a calcium response is not because the assay has reached saturation (Fig. 5B). In contrast, F508del mutant CFTR is known to have defective forskolin-mediated phosphorylation on S660 (37) and possibly on other PKA sites; thus, it is still able to bind calmodulin at elevated calcium levels, resulting in stimulation of activity (Fig. 5 D and G).

R-region Mutant CFTR Shows Altered Calmodulin Activation.

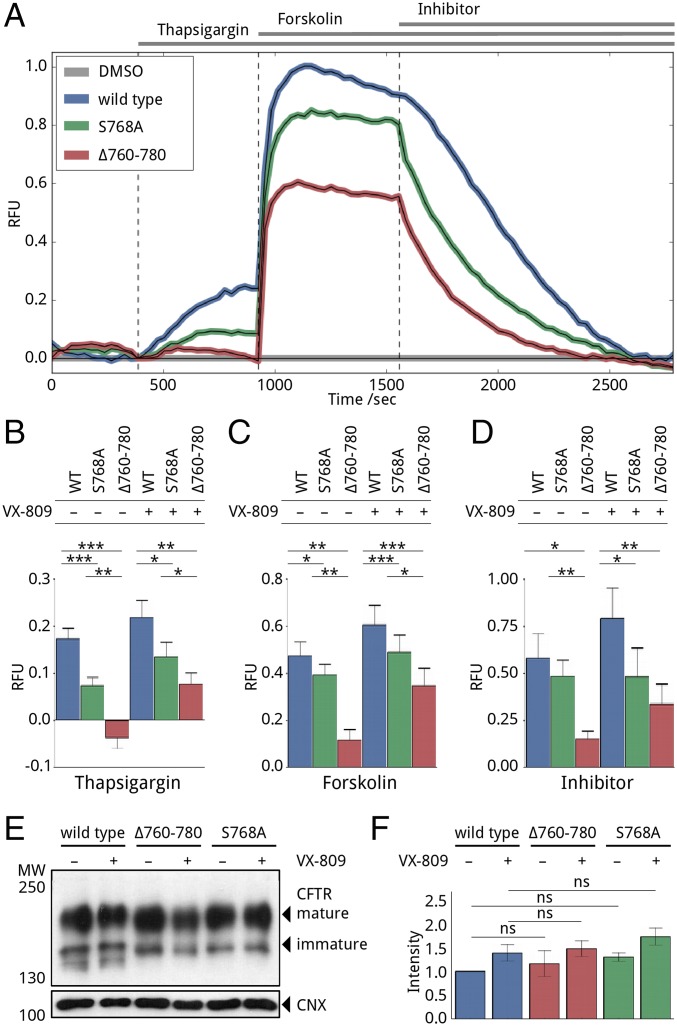

We interpreted the results of our FLIPR membrane potential assays in terms of direct binding of calcium-loaded calmodulin to CFTR R-region activating nonphosphorylated full-length wild-type and F508del CFTR. Because knocking down or silencing calmodulin perturbs many important biological processes with serious viability issues, to provide evidence for this hypothesized direct interaction between CFTR and calmodulin in cells and validate our in vitro results and the computational prediction, we introduced mutations in R region designed to modify calmodulin binding around the most prominent binding site, S768. We exchanged S768 to alanine (S768A) or deleted 21 residues between 760 and 780 (Δ760–780) in both wild type and F508del full-length CFTR backgrounds. Our NMR data show that the region 760–780 is most affected by calmodulin binding; thus, we predicted the deletion of this region would inhibit calmodulin binding. CFTR trafficking is phosphorylation dependent (1, 12); therefore, to avoid reduced trafficking caused by these mutations and to test the effect of increased surface presence of CFTR, cells transfected with these constructs were treated with VX-809, a CFTR corrector (33, 34), or DMSO control. Both S768A and Δ760–780 mutants in the wild-type background showed reduced activity (Fig. 6) upon activation with thapsigargin (Fig. 6B) or forskolin (Fig. 6C). The forskolin response is significantly less affected than the thapsigargin response, especially for Δ760–780, which has almost no thapsigargin response. The amounts of surface expression (band C) were not significantly different for wild type and S768A and Δ760–780 in the wild-type background in VX-809–treated and untreated cells (Fig. 6 E and F).

Fig. 6.

FLIPR membrane potential assay on wild-type and R-region mutant CFTR. (A) Representative traces of wild-type (blue), S768A (green), and Δ760–780 (red) mutant CFTR response to thapsigargin, forskolin, and CFTR inhibitor-172. Each curve is normalized to the average of four corresponding DMSO-treated traces. (B–D) Bar graph representation of the absolute value of thapsigargin (B), forskolin (C), and inhibitor (D) responses. Wild-type (blue), S768A (green), and Δ760–780 (red) mutant CFTR-expressing cells were pretreated with DMSO or VX-809 for 24 h before the experiment to investigate the effect of increased surface representations. Three biological with four technical replicates were measured in each case. Asterisks indicate significance differences with P values smaller than 0.05 (*), 0.01 (**), and 0.001 (***), respectively. (E) Representative Western blot developed against CFTR and loading control calnexin (CNX) to demonstrate evidence of expression and maturation of wild-type and R-region mutant CFTR. Samples were collected after experiments from DMSO-treated control wells. (F) Analysis of mature CFTR (band C) intensities presented on E. Intensities were normalized to the average of DMSO-treated wild-type samples. Statistical analysis of the corresponding bands of the three biological replicates show no significant (ns) differences between wild-type, S768A, and Δ760–780 mutant CFTR expression levels.

Previously, S768A has been shown to have higher activity than wild-type CFTR upon stimulation by only PKA (38); however, in our assay after thapsigargin treatment, S768A CFTR has a 15–20% reduction in forskolin response, but a 40–50% decrease in thapsigargin response. We attribute the reduction in forskolin response to the loss of one of the activating phosphorylation sites and the reduction in the thapsigargin response to perturbation of the calmodulin-binding site. The Δ760–780 mutant has 0–40 and 20–60% remaining activity upon thapsigargin and forskolin activation, respectively, compared with wild type. Based on its central role in calmodulin binding, it is not surprising that the deletion caused a significant effect on the thapsigargin response, and these results provide in-cell validation of the direct binding of calmodulin to CFTR. The reduction of forskolin response is probably due to a combination of the missing phosphorylation site, the loss of activation properties of this segment in proper CFTR function, and the altered intramolecular and intermolecular interaction network.

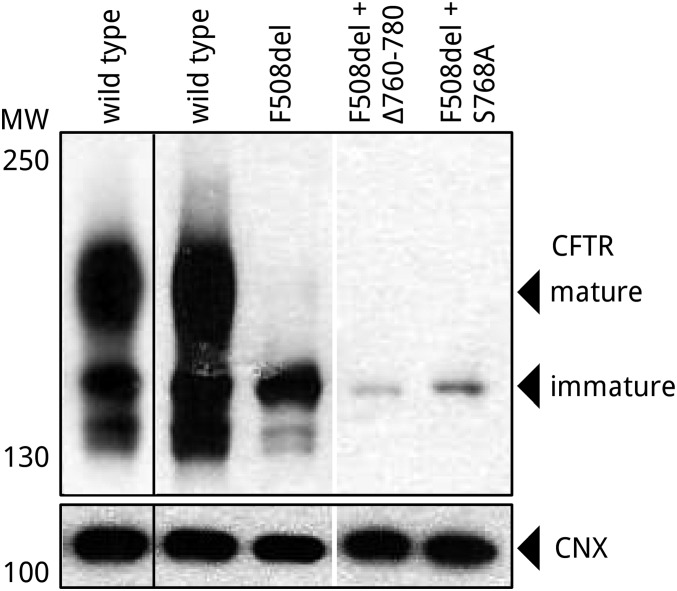

All of these in-cell experiments support the importance of the functional interaction between calmodulin and CFTR. Comparison of differences between wild-type and F508del behavior in response to sequential activation of the cAMP pathway and calcium signaling using the same R-region mutants in the F508del background would also have been valuable. Unfortunately, in combination with F508del, these R-region mutants had severe trafficking defects (Fig. S8); the measured signal was below the sensitivity of the assay. CFTR trafficking is a phosphorylation-dependent process (1, 12) with binding of phosphorylated R region to 14-3-3 contributing to forward trafficking. This provides a potential explanation for the loss of cell surface CFTR upon elimination of the S768 site through S768A substitution or 760–780 deletion in the F508del context.

Fig. S8.

Representative Western blot of R-region mutants in F508del CFTR background. Representative Western blot developed against CFTR and loading control calnexin (CNX) to demonstrate the lack of expression and maturation of S768A and Δ760–780 mutants in F508del CFTR background. To provide better band visibility, wild-type sample was also developed using a shorter exposure time (first column). Samples were collected similarly to Fig. 6.

Calmodulin and CFTR Colocalize Under the Apical Membrane.

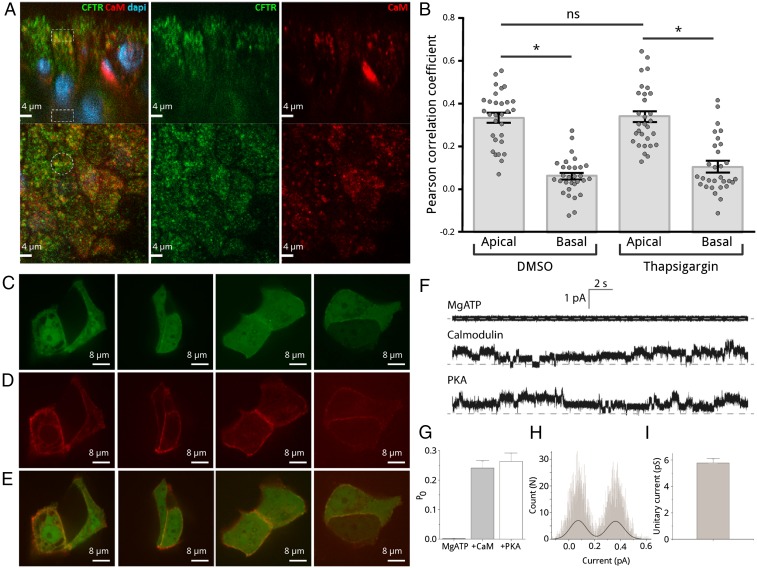

Antibody binding was used to compare the calmodulin and CFTR distributions at apical and basal membrane regions in fixed samples of fully polarized bronchial primary tissue from three different non-CF patients (Fig. 7 A and B). Although calmodulin is a ubiquitous cellular calcium sensor and is present throughout the cell, the Pearson correlation coefficient for calmodulin and CFTR distributions under the apical membrane is 0.33 ± 0.13, indicating that some calmodulin is near CFTR, whereas the correlation coefficient decreases to 0.05 ± 0.08 at the opposite side of the cell showing no colocalization. To investigate whether activating the calcium signal has any effect on the local calmodulin concentration, we pretreated the cells with thapsigargin (Fig. 7B). We found no evidence during the incubation time for a major effect on the local calmodulin concentration as correlation coefficients for thapsigargin and vehicle-treated cells were not significantly different. This finding is consistent with our developing understanding of the role of calmodulin with the interaction being regulated by both calcium and the phosphorylation state of R region but not modulated by localization changes requiring protein transport. In addition to the imaging on primary tissue, we performed live-cell imaging using bronchial cells with cotransfected, fluorescently labeled mCherry-CFTR and eGFP-calmodulin. Results clearly demonstrate plasma membrane colocalization (Fig. 7 C–E).

Fig. 7.

Colocalization studies and single-channel recordings of CFTR currents. (A) A representative image of fully polarized primary bronchial cultures from three different non-CF donors stained for CFTR, calmodulin (both via relevant antibodies), and nuclei (with DAPI) in two different orientations, side view (top row) and apical view (bottom row). Apical and basal regions (in 5-μm depths from the membrane) analyzed for comparison are marked by white dashed line. (B) Pearson correlation coefficients of the fitting of CFTR and calmodulin intensities in apical and basal regions with and without thapsigargin pretreatment. Apical and basal colocalizations are significantly different (P < 0.0001), but there is no significant difference between vehicle and thapsigargin treatment. On average, 10 cells per culture have been analyzed. (C–E) Live-cell imaging of human bronchial epithelial (16HBE14o−) cells overexpressing eGFP-human calmodulin (C, green) and mCherry-CFTR (D, red) with (E) the overlay of the calmodulin and the CFTR channels. Regions where the two proteins colocalize appear in yellow in (A) the apical membrane of the polarized primary cells and (E) the plasma membrane of the unpolarized 16HBE14o− cells. (F) Representative traces of CFTR channel currents from excised inside-out patches recorded in the presence of basic bath solution sequentially supplemented with Mg-ATP, calmodulin, and catalytic subunit of PKA. Traces were recorded from the same patch estimated to contain six CFTR channels. Dashed line represents zero current or all-channel closed state. (G) Normalized open probability for the recorded CFTR channels. The error bars represent the SDs of data collected for three independent excised patch recording sessions. (H) Representative histogram of unitary-current event. The black line is a fit with two-term Gaussian function. (I) Mean unitary current calculated based on fits of data such as in F; n = 24.

Calcium-Loaded Calmodulin Directly Activates CFTR.

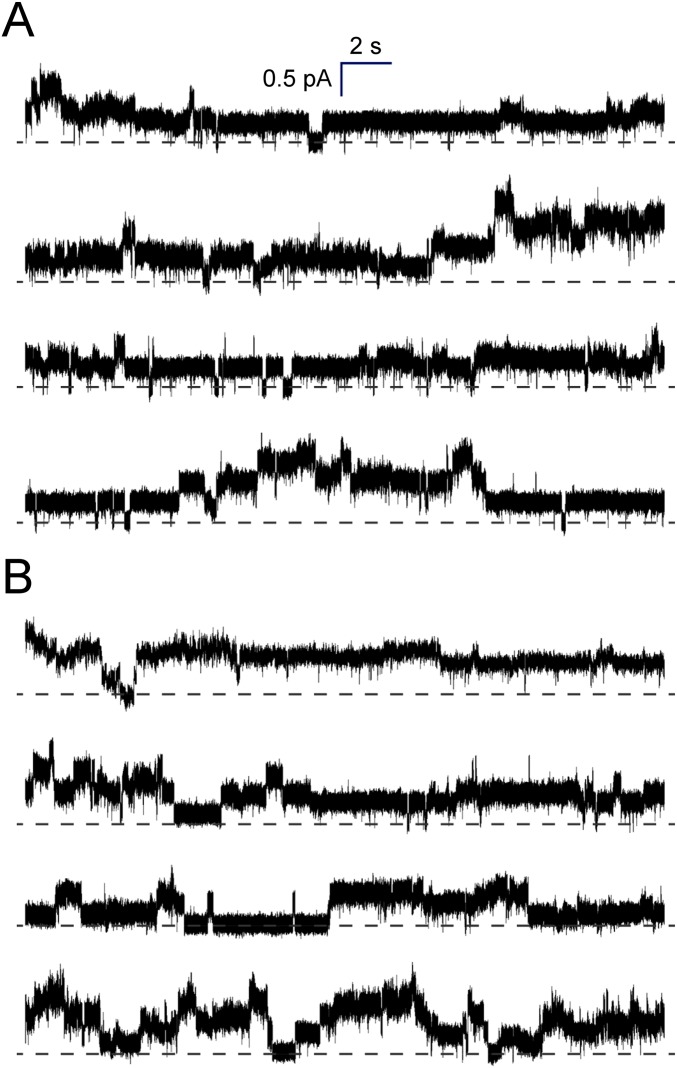

To provide further evidence for direct interaction between calmodulin and R region of full-length CFTR and to confirm that calcium-loaded calmodulin can directly activate CFTR, we measured CFTR activity in a patch-clamp experiment (Fig. 7 and Fig. S9). An excised “inside-out” patch with no or basal CFTR phosphorylation was treated sequentially with Mg-ATP, calcium-loaded calmodulin, and catalytic subunit of PKA (Fig. 7F and Fig. S9). Data were recorded on three independent patches excised on different days, yielding virtually identical results. Only patches that contained six or fewer CFTR channels were used for further analysis. Addition of ATP alone to buffers containing ∼1 μM free calcium did not result in any significant channel openings, consistent with it being required but insufficient for activation of CFTR. In contrast, calcium-calmodulin treatment gave an open probability of 0.24 ± 0.02, which was very similar to the open probability of 0.26 ± 0.03 measured following the subsequent addition of PKA. The results indicate that CFTR channel function can be triggered by calmodulin in the absence of R-region phosphorylation. The subsequent addition of PKA following calmodulin treatment did not significantly increase activity of the channel (Fig. 7G). CFTR specificity was ensured by calculating unitary current (5.32 ± 0.32 pS), in good agreement with previously reported values (6–10 pS) (Fig. 7 H and I).

Fig. S9.

Representative traces of CFTR single-channel currents. Traces were recorded in the presence of basic bath solution sequentially supplemented with (A) 0.4 mM MgATP and 10 μM calmodulin and (B) 5,000 U/mL PKA. Dashed line represents 0 current with all channels closed. The traces included in the same panel were recorded at different days and included four to six CFTR channels. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

Discussion

Cross-Talk Between Calcium and PKA Signaling for Activation of CFTR.

In this study, we present data supporting an interaction between calmodulin and the R region of CFTR that is phosphorylation and calcium concentration dependent. We performed NMR experiments on purified proteins and observed chemical shift changes indicative of a phosphorylation- and calcium-regulated interaction between R region and calmodulin. Inhibition of PKA phosphorylation in the presence of calmodulin, at the sites we identified as calmodulin binding, demonstrates that the interaction not only is direct but can interfere with other protein interaction and enzymatic activity. The micromolar affinity measured using BLI is consistent with an alternative binding mode for calmodulin, and the affinity and fast kon and koff rates are in line with expectations for interactions of the disordered CFTR R region that are transient and dynamic, as we previously demonstrated for a number of other R-region targets (14).

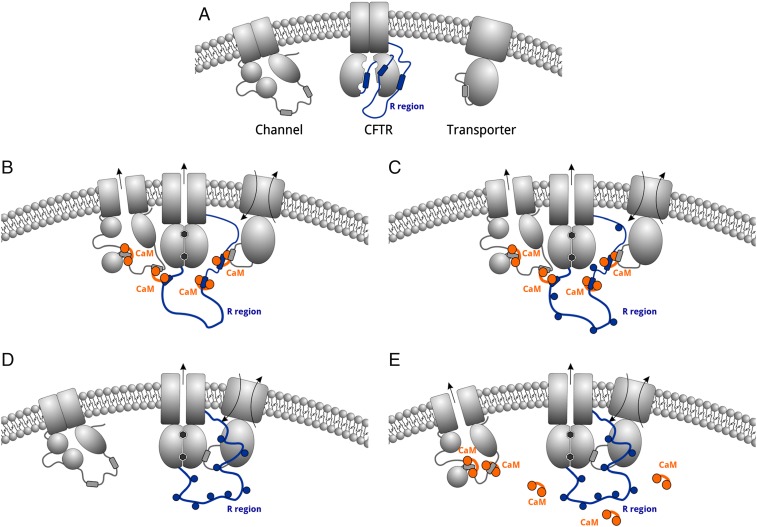

The biological significance of this dynamic interaction was supported by imaging experiments in both primary tissue and cotransfected cells that clearly show colocalization between the two proteins at the apical membrane. We demonstrated the contribution of this interaction to regulated CFTR channel activity at the single-channel level by patch-clamp (ex vivo) studies using CFTR-containing cell membranes, with activation of channel function upon addition of purified calcium-loaded calmodulin. PKA addition slightly activates further the chloride flux, indicating that calmodulin activates a PKA-sensitive chloride channel, such as CFTR. The anion selectivity and unitary conductance of ∼6 pS clearly identify the channel to be CFTR (39). Our FLIPR fluorescence-based membrane potential assay results using wild-type CFTR showed that activating the calcium pathway leads to chloride-ion flux that depends on the presence of CFTR and the phosphorylation state of the channel. Activating the cAMP–PKA–CFTR phosphorylation pathway alone or after a preceding calcium pathway stimulation displayed the same total change in membrane potential that was used as a measure of the chloride-ion flux (Figs. 5 and 8), suggesting that the two pathways are converging on the same function.

Fig. 8.

Synergistic effect of calcium and cAMP signaling on CFTR. Schematic model of CFTR and nonspecified transporter and membrane channel under various conditions. (A) Resting condition without any active signaling pathway. (B) Activated calcium pathway causes CFTR channel opening and membrane protein association. (C) Calcium signal followed by cAMP signaling results in additional CFTR activation. (D) cAMP signal stimulates CFTR channel function. (E) Calcium signal following cAMP activation has no additional effect on CFTR channel function, but can activate other membrane proteins. R region is colored in blue, and calmodulin is colored in orange. Blue circles indicate PKA phosphorylation sites.

In contrast, PKA-phosphorylated F508del mutant CFTR displayed additional calmodulin activation, indicating that its phosphorylation state is different from wild type. Although the difference in phosphorylation between wild-type and F508del CFTR was reported previously (37), the functional consequences have not been fully explored. Our FLIPR membrane potential assay data suggest that F508del CFTR does not reach full phosphorylation upon cAMP signaling probably because R-region accessibility is reduced. The reduction is most likely due to altered intramolecular interactions that result in higher R-region binding affinity to other CFTR domains. In other words, F508del mutant CFTR is locked in a phosphorylation-deficient conformation. The unexpected observation of calmodulin activation not being strongly influenced by reduced accessibility of R region requires further exploration.

Because knocking down or silencing calmodulin perturbs many important biological processes with serious viability issues, the specificity of calmodulin regulation of CFTR was confirmed using CFTR mutants in the calmodulin-binding site. CFTR constructs with calmodulin-binding site mutations display significantly reduced response to calcium signaling, strongly indicative of a direct interaction. These findings suggest that, upon a calcium signal, calmodulin can activate CFTR immediately, but the long-term stimulation can be further supported by phosphorylation activated by calcium-dependent adenylate cyclases (8) or other processes (6). As a consequence, depending on the duration of the calcium signal, wild-type CFTR can be either just briefly activated by calmodulin or activated for a longer period by initial calmodulin binding followed by PKA phosphorylation beyond the time of the calcium signal. Addition of purified calmodulin to CFTR-containing membranes and activating calmodulin in cells both result in CFTR activation, with the total CFTR activity being the same in samples exposed to just PKA or calmodulin followed by PKA, indicative of calmodulin directly interacting with CFTR in cells. Together, these data reveal the molecular basis underlying a calcium-dependent regulatory mechanism for the normal and major CF-causing mutant.

The site-specific NMR phosphorylation kinetics experiment (Fig. 4) revealed an important aspect of the cross-talk between cAMP and calcium signals on CFTR. Namely, the two most rapidly phosphorylated PKA sites (S768 and S660) are also found within calmodulin-binding sites, indicating that the two signaling pathways are segregated at a very early stage of the signaling process. In other words, mild PKA phosphorylation that does not necessary activate the channel disconnects CFTR from the calcium pathway. This layer of regulation by PKA may be why CFTR is basally phosphorylated in many cases (29, 38) and, depending on local conditions, why different basal phosphorylation patterns of CFTR exist (38). Since the early work of Wilkinson et al. (29), there has been debate regarding the role of different phosphorylation sites in CFTR channel function. Residues S737 and S768 were reported to be inhibitory sites because changing them to alanine lowers the 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) requirement for channel activation (29); however, later work questioned these findings (30). In our FLIPR membrane potential assay setup, the forskolin concentration (10 μM) used to achieve full activation and the lag time between drug addition and the next time point read did not allow us to comment on the kinetics of activation, but we observed a significantly decreased total membrane potential change after forskolin stimulation for both S768A and Δ760–780 mutants lacking the possibility of phosphorylation at residue 768, strongly indicative of a direct interaction. Interestingly, the rank order of reported IBMX dose-dependent data on serine-to-alanine mutants (29) matches within error to our R-region phosphorylation kinetic results (Fig. 4), with the exception of phosphorylation at 660 that was reported to have a small effect but for which we see rapid phosphorylation. This difference may be due to NBD1 in full-length CFTR restricting access to the 660 site for PKA. The interpretation of the negative correlation between the rate of phosphorylation of a given residue (S768 > S660 > S737 > S700, S712, S795 > S813) and the importance in IBMX dose-dependent activation of the same residue (S768 < S737 < S700 < S660, S795 < S813) (29) is not obvious based on the current knowledge that exists on the role of R region in CFTR channel regulation (10, 11, 14) and requires further investigation.

Considering the importance of calcium signaling in the regulation of airway fluid secretion (4) and the fact that CF patients with impaired CFTR function have altered calcium concentration regulation (40), it is not surprising that calcium signal-activated CFTR and CFTR-regulated calcium signaling were recently the targets of many studies (6, 8, 41). No publication, however, has reported this direct calmodulin–CFTR interaction previously. Inactive, but basally phosphorylated, CFTR that is incompatible with calmodulin binding may dominate in other cellular systems, preventing observation of a direct effect of calcium signaling on CFTR activation. However, in BHK cells, CFTR was shown to be activated by carbachol, an agonist of M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor causing elevated calcium levels, even after the removal of 15 PKA and 9 PKC sites (6). Although the data presented in that study support tyrosine phosphorylation as a major player in CFTR activation, wild-type CFTR displayed only a 30% decrease in activity upon exposure of PP2A and Src inhibitors. Interestingly, the 15SA-CFTR mutant lacking the ability to be PKA-phosphorylated demonstrated no residual activity under the same conditions (6). In the present study, we showed that serine-to-alanine mutation at residue 768 results in decreased calmodulin binding, suggesting that the absence of 15SA-CFTR activity could be also explained by reduced calmodulin binding.

Calmodulin Regulates Microdomain Assembly.

A fascinating aspect of the interaction between calmodulin and its substrates is the different consequences of its two distinct binding modes. A number of membrane channels and transporters in close proximity to CFTR have been reported to interact with calmodulin using the alternative binding mode in which calmodulin reversibly cross-links two protein ligands (18, 23). These include Orai1 (25), the sodium channel NaV1.5 (26), and the potassium channel Kv7.1 (27). This cross-linking is expected to play a significant role in functional regulation and in macromolecular complex assembly (23). The finding that individual lobes give rise to identical NMR signal perturbation as full-length calmodulin indicates that a single lobe of calmodulin is sufficient to regulate CFTR and provides evidence for CFTR using the alternative calmodulin-binding mode. Moreover, the measured binding affinity for this interaction is in good agreement with other alternative binding mode substrates, but not with canonical ligands (25). As a consequence, calcium signaling is predicted to have a significant role in the regulation of CFTR microdomain assembly by physically cross-linking channels and transporters to CFTR (Fig. 8). In a recent study, KCa3.1 has been shown to interact with CFTR in a calcium-dependent manner involving calmodulin, supporting this model (17). These interactions are likely part of a network among the membrane proteins within the microdomain, either involving direct calmodulin interactions or increased contacts due to the close and fixed proximity. A central component of this network is the intrinsically disordered R region of CFTR responsible for almost all of the regulatory intermolecular protein interactions of CFTR (Fig. 8). Regulatory signals from various sources converge on R region (1) and calmodulin interaction may be one of the ways this information is distributed within the macromolecular complex to control and synchronize ion channel and transport functions. Although activation of nonphosphorylated F508del mutant CFTR by calmodulin was similar to wild type, phosphorylated channels displayed completely opposite responses in our VX-809–treated HEK-293 overexpressing cell system. These results indicate altered phosphorylation and accessibility and therefore different interactions of R region in the mutant protein. PKA phosphorylation completely decouples calcium signaling from wild-type CFTR, but not the F508del mutant, potentially enabling stimulation of other membrane protein channels. For instance, this additional stimulus can increase activity of the apical calcium channels, leading to an elevated local calcium concentration (23) that is associated with the constant inflammation seen in CF patients (42, 43).

In conclusion, the results we described on the cross-talk between calcium and cAMP signaling in CFTR channel function and regulation provide a detailed view of this interaction. Although no evidence of the direct interaction between calmodulin and CFTR has been described previously, differences in basal phosphorylation patterns at the three interaction segments in various cell types and under various conditions may provide an explanation. Importantly, differences in phosphorylation patterns between wild type and F508del may enable targeting of this interaction with small molecules that prevent mutant CFTR from calmodulin binding. Based on the ability of calmodulin to couple CFTR to other membrane channels and transporters, including those in the ER accessible even to CFTR that does not reach the plasma membrane, this could modulate calcium signaling to reduce inflammation and provide significant therapeutic benefits for patients.

Materials and Methods

A summary of the methods is provided here. Details are found in SI Materials and Methods.

Protein Expression and Purification.

Human CFTR R region (654–838, F833L) was expressed and purified as in ref. 31. Calmodulin full-length (149 residues) and N-terminal (1–80) and C-terminal (81–149) calmodulin lobes were expressed in DB21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIL cells.

R-region Phosphorylation by PKA.

Phosphorylation by the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase was monitored by mass spectrometry.

NMR Binding Experiments.

R-region interaction measurements in the presence or absence of full-length, N-lobe, and C-lobe calmodulin were carried out using 1H13C15N-labeled R region and unlabeled partner at 1:2 molar ratio with HSQC and HNCO spectra. Calmodulin interaction measurements in the presence or absence of nonphosphorylated and PKA-phosphorylated R region were carried out using 1H15N-labeled calmodulin and unlabeled partner at 1:2 molar ratio using HSQC spectra.

Affinity Measurements.

The Octet RED 96 system to obtain BLI data was used for measuring kon and koff rates between calmodulin and the R region of CFTR.

Phosphorylation Kinetics Measurements.

R-region phosphorylation by PKA in the presence and absence of calmodulin was followed using 1H13C15N-labeled R region at 10 °C by measuring 10-min HSQC spectra.

FLIPR Membrane Potential Assay.

CFTR functional studies were executed on 96-well plates according to Molinski et al. (35).

Multilayer Confocal Imaging.

Primary bronchial epithelial cells as air–liquid interface cultures were obtained from the Iowa CF culture facility (44). Mouse monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody and rabbit polyclonal anti-calmodulin antibody were used to probe the cells following fixing. Multilayer confocal scan imaging (0.1 μm per layer) was performed using an Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescence microscope.

Live-Cell Imaging.

CFTR knockout human bronchial epithelial cells 16HBE14o− (45) were transfected with eGFP-human calmodulin (46) and mCherry-CFTR (47). Images were acquired using a Zeiss AxioVert 200M spinning disk confocal microscope.

Patch Clamp.

Electrophysiological recordings were made on 16HBE14o− cells using Axopatch 200B amplifier and Digidata 1440A digitizer (Molecular Devices).

SI Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Human CFTR R region from position 654–838, F833L, was expressed and purified according to Baker et al. (31). The F833L polymorphism was introduced to enhance solubility for biophysical experiments. Calmodulin (National Center for Biotechnology Information Protein P62158) was expressed in BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIL cells from a plasmid encoding full-length (149 residues) protein. N-terminal and C-terminal calmodulin lobe constructs contained calmodulin sequence amino acids 1–80 and 81–149, respectively. Calmodulin expression was induced with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (1 mM) in LB media for 16 h at 16 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Five milliliters per gram lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.50; 1 mM CaCl2; 5 mM DTT) were added to resuspend the pellet, and the cell lysis were performed by sonication (300 s, 40% pulsing). A second spin (20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C) was used to separate the insoluble fraction, and the supernatant was loaded on a HiTrap anion exchange column (GE; Q HP). After a 10-column volume (CV) wash with low-salt buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.50; 50 mM NaCl; 2 mM DTT), a 20-CV linear gradient was applied going from 0 to 100% into a high-salt buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.50; 500 mM NaCl; 2 mM DTT). Calmodulin-containing fractions were collected and further separated on a size exclusion column (GE; HiLoad Superdex 75), using 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.50; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM DTT buffer.

R-region Phosphorylation by PKA.

We used 2,500 units of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (NEB; P6000S) to phosphorylate 1-mmol R region in a buffer of 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.50, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, and 2 mM DTT at 37 °C for 16 h. The progress of the phosphorylation reaction was monitored by mass spectrometry. PKA was removed by reverse-phase HPLC chromatography on a C4 preparative column.

R-region–Binding NMR Experiments.

R-region interaction measurements in the presence or absence of full-length, N-lobe and C-lobe calmodulin were carried out using 1H13C15N-labeled R region and unlabeled partner at 1:2 molar ratio (150 and 300 μM, respectively) by recording proton–nitrogen (HSQC) and proton–nitrogen–carbon (HNCO) correlation spectra (128 indirect points, 16 transients, and 48, 40 indirect points, eight transients, respectively) on an 800-MHz Varian NMR spectrometer at 10 °C in a buffer of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 10% (vol/vol) D2O supplemented with either 20 mM CaCl2 or 0 mM CaCl2 to buffer free calcium concentration to 40 μM (see details in the Calmodulin-Binding NMR Experiments section below). To equilibrate calcium concentrations, all proteins were dialyzed against 2 L of buffer before experiments. Peak volumes were analyzed using FuDA (www.biochem.ucl.ac.uk/hansen/fuda/).

Calmodulin-Binding NMR Experiments.

Calmodulin interaction measurements in the presence or absence of nonphosphorylated and PKA-phosphorylated R region were carried out using 1H15N-labeled calmodulin and unlabeled partner at 1:2 molar ratio (200 and 400 μM, respectively) by recording proton–nitrogen (HSQC) correlation spectra (72 indirect points, 16 transients) on an 800-MHz Varian NMR spectrometer at 10 °C in a buffer of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 10% (vol/vol) D2O supplemented with either 20 mM CaCl2 or 0 mM CaCl2 to bring the free calcium concentration to 40 or 0 μM, respectively. The 20 mM EGTA/20 mM CaCl2 mixture served as a calcium buffer that kept the free calcium concentration constant, which means that in addition to full saturation of calmodulin with calcium, there is 40 μM additional available calcium-ion concentration at all time. We selected the 40 μM free calcium concentration to be confidently beyond the calmodulin:calcium dissociation constant, but still close to the physiological calcium level. Calmodulin titration with R region was done using 150 μM 1H15N-labeled calmodulin and unlabeled R region at 0.10, 0.20, 0.45, 0.55, 0.70, and 1.25 molar access (15, 30, 70, 85, 105, and 190 μM, respectively) in a buffer of 15 mM Bis-Tris·HCl, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 10% (vol/vol) D2O. Proton–nitrogen (HSQC) correlation spectra (72 indirect points, eight transients) were recorded on 500-MHz Varian NMR spectrometer at 25 °C.

Affinity Measurements.

The Octet RED 96 system to obtain biolayer interferometry (BLI) data (Fortebio) was used for measuring kon and koff rates between calmodulin and the R region of CFTR in calcium buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 12 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA) or calcium-free buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM EGTA). Calmodulin was prepared as described in the method above. The R region was prepared according to Baker et al. (31) but without TEV protease treatment and the subsequent Ni2+ affinity chromatography to retain the hexahistidine tag for immobilization purpose. Ni-NTA biosensors (Fortebio) were prewetted with the corresponding buffer for 15 min before the biosensors were used in the assay. The assay was performed in 96-well plates at a volume of 180 μL per well while shaking the plate at 1,000 rpm. For the initial step, the biosensors were washed with buffer for 60 s. As a second step, the biosensors were loaded with the hexahistidine-tagged R-region sample (75 nM) for 600 s. After another washing period of 180 s with the corresponding buffer, the biosensors were moved into calmodulin solutions with varying concentrations between 70 and 4.38 μM for 100 s (with calcium) or 300 s (without calcium). Subsequently, the biosensors were moved back to the corresponding buffer. The response profiles were globally fitted using a 1:1 complex model after baseline subtractions.

Phosphorylation Kinetics Measurements.

R-region phosphorylation in the presence and absence of calmodulin was followed using a 115 μM 1H13C15N-labeled R-region concentration supplemented with 300 or 0 μM calmodulin in a buffer of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.20, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM EGTA, 30 mM MgCl2, and 19.8 mM CaCl2; ATP, EGTA, MgCl2, and CaCl2 concentrations were selected such that free metal concentrations were 20 mM and 40 μM, respectively. Proteins were dialyzed against the same buffer for 24 h to fully equilibrate calmodulin with (or without) calcium. The reaction was started by adding 2,500 units of PKA catalytic subunit into the sample and followed at 10 °C by measuring 10-min proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) with four transients and 64 indirect points on a 500-MHz Varian spectrometer. In total, 1 spectrum without the PKA and 125 spectra with the kinase were recorded for both the apo and complex cases.

FLIPR Membrane Potential Assay.

CFTR functional studies were executed on a 96-well plate according to Molinski et al. (35) using the following compound concentrations: FLIPR membrane potential dye (0.5 mg/mL; Molecular Devices), VX-809 (3 μM; Selleck Chemicals), forskolin (0.1, 1.0, or 10.0 μM; Sigma), thapsigargin (2 μM; Sigma), CFTR inh-172 (10 μM; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics), and BAPTA-AM (50 μM; Sigma). The extracellular calcium concentration (1.3 mM) was set using calcium gluconate (Sigma). In all cases, DMSO was used as a vehicle control. Python scripts were used for data analysis, and statistical tests were performed using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software).

Western Blotting.

Following transfection and chemical correction, cells were lysed using a buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, containing 0.1% (vol/vol) SDS, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and 1% (vol/vol) protease inhibitor mixture (Amresco), and then incubated at 4 °C for 15 min. Following incubation, lysates were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected from each cell sample and solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer (at a 1:5 dilution) and run on an SDS/PAGE gel. Protein was then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk. Following blocking, the membrane was probed with either an antibody against human CFTR 596 (1:10,000; CFFT and UNC-CH) or human calnexin (1:10,000; Sigma), and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, which was raised in goat, against rabbit or mouse (added in a 1:5,000 dilution). The membrane was then washed, and chemiluminescence was used to detect signals from the respective antigens. The images were analyzed using ImageJ 1.42 Q software (National Institutes of Health).

Multilayer Confocal Imaging.

Primary bronchial epithelial cells as air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures were obtained from the Iowa CF culture facility (44). Mouse monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody, clones 13-1 and 24-1, are both from R&D Systems. Rabbit polyclonal anti-calmodulin antibody was provided by Abcam. Human bronchial epithelial cultures grown on ALI membrane were fixed in a mixture of 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde, 0.01% glutaraldehyde, in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 1 h. Cell patches were neutralized in 150 mM glycine, 80 mM NH4Cl, 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 10 min, washed three times with 150 mM glycine in phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 5 min, and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, in 150 mM glycine, 0.5% BSA, and 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 20 min, with solution changing every 4 min. To block nonspecific staining, the samples were incubated in 4% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS for 30 min. Incubation with primary and secondary antibodies was done in the same blocking solution. DAPI was used as a nuclear stain. Multilayer confocal scan imaging (0.1 μm per layer) was performed in the Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C9100-13 back-thinned EM-CCD camera and Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk confocal scan head. Data were processed with Volocity software suite (PerkinElmer). CFTR and calmodulin colocalization was quantified as Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC), using Costes method (48) for automatic thresholds setting. Regions of interest (ROIs) were hand-drawn at both apical and basal areas of randomly picked single cells. PCC values for apical and basal ROIs from 10 cells of each donor samples were compared and plotted. Samples from three different donors were analyzed.

Live-Cell Imaging.

CFTR knockout human bronchial epithelial cells, 16HBE14o− (from Dieter Gruenert, UCSF School of Medicine and Medical Center, University of California, San Francisco) (45), were grown in Eagle’s minimal essential medium, 10% (vol/vol) FBS, and penicillin and streptomycin (1%) at 37 °C and 5% (vol/vol) CO2. The cells were transfected with plasmids encoding eGFP-human calmodulin (from Emanuel E. Strehler, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Addgene plasmid no. 47602) (46) and mCherry-CFTR (from Margarida D. Amaral, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal) (47) using PolyFect (Qiagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. For optimal expression level of the proteins, images were obtained after 24 and 48 h after transfection of eGFP-human calmodulin and mCherry-CFTR plasmids, respectively. All images were acquired using a Zeiss AxioVert 200M spinning disk confocal microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C9100-13 EM-CCD and a 63× objective (oil) with a numerical aperture of 1.4. eGFP-human calmodulin and mCherry-CFTR fluorophores were excited with 491 nm (50 mW) and 561 nm (50 mW) lasers, respectively. Temperature, humidity, and CO2 level were maintained with a live-cell chamber (Live Cell Instrument) during image acquisition. All images were processed with Volocity software (PerkinElmer).

Patch Clamp Experiments.

Human bronchial epithelial cell line 16HBE14o− (45) was used for data recordings. All electrophysiological recordings were made at room temperature using Axopatch 200B amplifier and Digidata 1440A digitizer (Molecular Devices). The data were collected at 5-kHz sampling rate with the amplifier low-path Bessel filter (80 dB/DECADE) set at 1 kHz. To achieve reliable excised inside-out patch configurations, tight sealed patches (>50 GΩ) were excised by prompt pipette lifting and short exposure to air (∼1 s) to ensure that no closed membrane bubbles were formed at the pipette tip. Basic bath solution (intracellular) and pipette solution (extracellular) were identical and contain 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 150 mM NMDG·Cl, 2 mM MgCl2, as well as about 1 μM free calcium (49). The basic bath solution was sequentially supplemented with 0.4 mM MgATP, 10 μM calmodulin (with 41 μM total calcium buffered by the calmodulin), and 5,000 U/mL PKA. Two- to 3-MΩ pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass with filament (BF150-110-10) using a P-97 puller (Sutter Instrument). The pipettes were coated with Sylgard to reduce noise and polished to 3.5- to 5.5-MW resistance, when measured in pipette solution. Recordings were made at −50-mV voltage potential using a no-gap voltage-clamp protocol. Data were analyzed using the Clampfit 10.3 program (Molecular Devices) and further filtered with a low-path Bessel (eight-pole) filter using a cutoff at 100 Hz. Idealization was done at Qub suit (www.qub.buffalo.edu) using a model with a single closed state sequentially connected to open states. The number of channels was identified as most channels open during the entire experiment (>25 min of uninterrupted recording). To ensure that the number of channels is not underestimated, only recordings with six or fewer channels, which exhibit all-channel–open events three or more times during experiment, were used. Open probability was calculated as follows:

where Po is open probability, n is number of channels in the patch, i is number of channels open for corresponding level of current in idealized data, and Oi is the occupancy of the corresponding open state.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dieter Gruenert for the 16HBE14o− cell line, Emanuel E. Strehler for the eGFP-calmodulin plasmid, Margarida Amaral for the mCherry-CFTR plasmid, Mitsu Ikura for the individual calmodulin lobe constructs, Shaf Keshavjee and Thoracic Surgery Research Laboratory (University Health Network) and the Iowa Cell Culture Facility (directed by Michael J. Welsh and managed by Philip Karp) for the primary lung cultures, Lewis Kay and Ranjith Muhandiram for assistance with NMR data collection, and Mitsu Ikura, Veronika Csizmok, and Andrew Chong for stimulating and helpful discussions. The work was funded by Cystic Fibrosis Canada Grants 3175 (to J.D.F.-K.) and 3172 (to C.E.B.), Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Grant FORMAN13XX0 (to J.D.F.-K.), and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP125855 (to C.E.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1613546114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Farinha CM, Swiatecka-Urban A, Brautigan DL, Jordan P. Regulatory crosstalk by protein kinases on CFTR trafficking and activity. Front Chem. 2016;4(January):1. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2016.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunzelmann K, Mehta A. CFTR: A hub for kinases and crosstalk of cAMP and Ca2+ FEBS J. 2013;280(18):4417–4429. doi: 10.1111/febs.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billet A, Hanrahan JW. The secret life of CFTR as a calcium-activated chloride channel. J Physiol. 2013;591(21):5273–5278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee RJ, Foskett JK. Ca2+ signaling and fluid secretion by secretory cells of the airway epithelium. Cell Calcium. 2014;55(6):325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans MG, Marty A. Calcium-dependent chloride currents in isolated cells from rat lacrimal glands. J Physiol. 1986;378:437–460. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billet A, Luo Y, Balghi H, Hanrahan JW. Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in the muscarinic activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) J Biol Chem. 2013;288(30):21815–21823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.479360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen JE, Sheridan JT, Polk W, Davies CM, Tarran R. Cigarette smoke-induced Ca2+ release leads to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(11):7671–7681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.545137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shan J, et al. Bicarbonate-dependent chloride transport drives fluid secretion by the human airway epithelial cell line Calu-3. J Physiol. 2012;590(21):5273–5297. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.236893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moran O. Model of the cAMP activation of chloride transport by CFTR channel and the mechanism of potentiators. J Theor Biol. 2010;262(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(1) Suppl:S77–S107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guggino WB, Stanton BA. New insights into cystic fibrosis: Molecular switches that regulate CFTR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(6):426–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang X, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 protein interactions regulate CFTR biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(6):996–1009. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khushoo A, Yang Z, Johnson AE, Skach WR. Ligand-driven vectorial folding of ribosome-bound human CFTR NBD1. Mol Cell. 2011;41(6):682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozoky Z, et al. Regulatory R region of the CFTR chloride channel is a dynamic integrator of phospho-dependent intra- and intermolecular interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(47):E4427–E4436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315104110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balghi H, et al. Enhanced Ca2+ entry due to Orai1 plasma membrane insertion increases IL-8 secretion by cystic fibrosis airways. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4274–4291. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Son A, Park S, Shin DM, Muallem S. Orai1 and STIM1 in ER/PM junctions: Roles in pancreatic cell function and dysfunction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310(6):C414–C422. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00349.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein H, et al. Investigating CFTR and KCa3.1 protein/protein interactions. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tidow H, Nissen P. Structural diversity of calmodulin binding to its target sites. FEBS J. 2013;280(21):5551–5565. doi: 10.1111/febs.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kursula P. The many structural faces of calmodulin: A multitasking molecular jackknife. Amino Acids. 2014;46(10):2295–2304. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1795-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James P, Vorherr T, Carafoli E. Calmodulin-binding domains: Just two faced or multi-faceted? Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88949-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bähler M, Rhoads A. Calmodulin signaling via the IQ motif. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(1):107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yap KL, et al. Calmodulin target database. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2000;1(1):8–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1011320027914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovalevskaya NV, et al. Structural analysis of calmodulin binding to ion channels demonstrates the role of its plasticity in regulation. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465(11):1507–1519. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meador WE, Means AR, Quiocho FA. Modulation of calmodulin plasticity in molecular recognition on the basis of X-ray structures. Science. 1993;262(5140):1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.8259515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, et al. Crystal structure of calmodulin binding domain of orai1 in complex with Ca2+ calmodulin displays a unique binding mode. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):43030–43041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarhan MF, Tung CC, Van Petegem F, Ahern CA. Crystallographic basis for calcium regulation of sodium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(9):3558–3563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114748109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sachyani D, et al. Structural basis of a Kv7.1 potassium channel gating module: Studies of the intracellular c-terminal domain in complex with calmodulin. Structure. 2014;22(11):1582–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radivojac P, et al. Calmodulin signaling: Analysis and prediction of a disorder-dependent molecular recognition. Proteins. 2006;63(2):398–410. doi: 10.1002/prot.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkinson DJ, et al. CFTR activation: Additive effects of stimulatory and inhibitory phosphorylation sites in the R domain. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):L127–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hegedus T, et al. Role of individual R domain phosphorylation sites in CFTR regulation by protein kinase A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788(6):1341–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker JMR, et al. CFTR regulatory region interacts with NBD1 predominantly via multiple transient helices. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(8):738–745. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alzamora R, King JD, Jr, Hallows KR. CFTR regulation by phosphorylation. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;741:471–488. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-117-8_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren HY, et al. VX-809 corrects folding defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein through action on membrane-spanning domain 1. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(19):3016–3024. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuk K, Taylor-Cousar JL. Lumacaftor and ivacaftor in the management of patients with cystic fibrosis: Current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2015;9(6):313–326. doi: 10.1177/1753465815601934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molinski SV, Ahmadi S, Hung M, Bear CE. Facilitating structure-function studies of CFTR modulator sites with efficiencies in mutagenesis and functional screening. J Biomol Screen. 2015;20(10):1204–1217. doi: 10.1177/1087057115605834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X-S, et al. Ca2+ and calmodulin initiate all forms of endocytosis during depolarization at a nerve terminal. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(8):1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nn.2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasyk S, et al. The major cystic fibrosis causing mutation exhibits defective propensity for phosphorylation. Proteomics. 2015;15(2-3):447–461. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Csanády L, et al. Preferential phosphorylation of R-domain serine 768 dampens activation of CFTR channels by PKA. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125(2):171–186. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]