Significance

DNA damage-bypass mechanisms that facilitate the resolution of replication blocks in proliferating cells during and after S phase are important for the defense against damage-induced mutations, genome instability, and cancer. Lesion bypass, mediated either by the ubiquitylation of the replication factor proliferating cell nuclear antigen or by homologous recombination, takes place in the context of chromatin. However, the implications of nucleosome dynamics and chromosome packaging in the efficiency of replication-associated damage processing are still largely unknown. Our physical, genetic, and cytological studies suggest that ubiquitylation of histone H2B facilitates the replicative bypass of fork-stalling DNA lesions by contributing to both DNA damage tolerance and homologous recombination during and after replication, thus revealing a direct link between chromatin architecture and lesion bypass.

Keywords: Bre1 E3 ubiquitin ligase, chromatin, H2B ubiquitylation, DNA damage tolerance, homologous recombination

Abstract

DNA lesion bypass is mediated by DNA damage tolerance (DDT) pathways and homologous recombination (HR). The DDT pathways, which involve translesion synthesis and template switching (TS), are activated by the ubiquitylation (ub) of PCNA through components of the RAD6-RAD18 pathway, whereas the HR pathway is independent of RAD18. However, it is unclear how these processes are coordinated within the context of chromatin. Here we show that Bre1, an ubiquitin ligase specific for histone H2B, is recruited to chromatin in a manner coupled to replication of damaged DNA. In the absence of Bre1 or H2Bub, cells exhibit accumulation of unrepaired DNA lesions. Consequently, the damaged forks become unstable and resistant to repair. We provide physical, genetic, and cytological evidence that H2Bub contributes toward both Rad18-dependent TS and replication fork repair by HR. Using an inducible system of DNA damage bypass, we further show that H2Bub is required for the regulation of DDT after genome duplication. We propose that Bre1-H2Bub facilitates fork recovery and gap-filling repair by controlling chromatin dynamics in response to replicative DNA damage.

Lesion bypass mechanisms that allow replicative processes to overcome replication blocks are important for cancer suppression and the maintenance of genome stability. The block of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-associated replication machinery by DNA adducts results in the generation of single-stranded (ss) DNA gaps at the damage site, whereas the replicative helicase continues to unwind ahead of the fork (1, 2). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PCNA is modified by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) Rad6, in cooperation with the E3 ubiquitin ligase Rad18, for the initiation of RAD6-dependent DNA damage tolerance (DDT) pathways (3). The essential ssDNA-binding Replication protein A (RPA) is involved in most DNA transactions; the interaction of RPA with Rad18 is required for PCNA ubiquitylation to activate DDT pathways (4). One of the ubiquitin-dependent DDT pathways involves monoubiquitylation of PCNA at lysine 164, which triggers mutagenic translesion synthesis (TLS) through the recruitment of low-fidelity damage-tolerant DNA polymerases. TLS polymerases lack proofreading activity (i.e., they are error-prone) and contain shallower active sites that allow them to directly replicate across DNA lesions (5–9). A second ubiquitin-dependent DDT pathway involves polyubiquitylation of PCNA by the E2 enzyme Ubc13-Mms2 and the E3 enzyme Rad5 through the addition of a K63-linked polyubiquitin chain onto monoubiquitylated PCNA, which triggers an error-free process named template switching (TS). This pathway likely involves a switch of the stalled primer terminus from the replication-blocked strand to the undamaged sister chromatid, which becomes a temporary replication template for damage bypass (10–13). PCNA SUMOylation prevents unscheduled and potentially toxic recombination by recruiting the Srs2 antirecombinase (14, 15). Rad51-dependent homologous recombination (HR), which is usually repressed by Srs2, serves as an alternative process to the RAD6-dependent DDT pathways (16). The absence of DDT pathways frequently results in the formation of DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) through the collapse of replication forks, and in this scenario HR is required to reinitiate replication (17–19).

The eukaryotic chromosome is tightly packaged into chromatin, and as such, lesion bypass must take place within this context (20–25). Several reports have implicated chromatin regulators in the response to replication-associated DNA damage (26–28). However, it is not clear how chromatin status affects DDT pathways. Intriguingly, Rad6, in cooperation with the E3 enzyme, Bre1, plays a role in regulating ubiquitylation of H2B at lysine 123 in budding yeast, unrelated to its role in ubiquitylating PCNA (29–32). H2Bub has been implicated in transcriptional elongation (33, 34), mRNA processing and export (35), DNA replication (36, 37), and repair of DSBs through relaxing chromatin structure (38, 39). Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism and the mode of action of H2Bub in regulating replicative DNA damage remain largely unknown.

Here, we show that the presence of H2Bub in chromatin is required for the replication fork to traverse lesions that cause fork stalling. In the absence of H2Bub, RPA foci accumulate, which is probably due to the deregulation of the DDT and HR pathways. Importantly, the requirement of H2Bub for template switching and HR appears to be largely related to the recruitment of Rad51 in S phase. Moreover, we found that H2Bub influences lesion bypass not only during S phase, but also during G2/M phase, at which stage H2Bub may be required for restoration of chromatin status after bulk DNA synthesis is completed. Together, our results indicate the importance of H2Bub in lesion bypass during and after genome replication.

Results

Physical Evidence for the Recruitment of Bre1 to DNA Lesions Produced by Alkylating Agents.

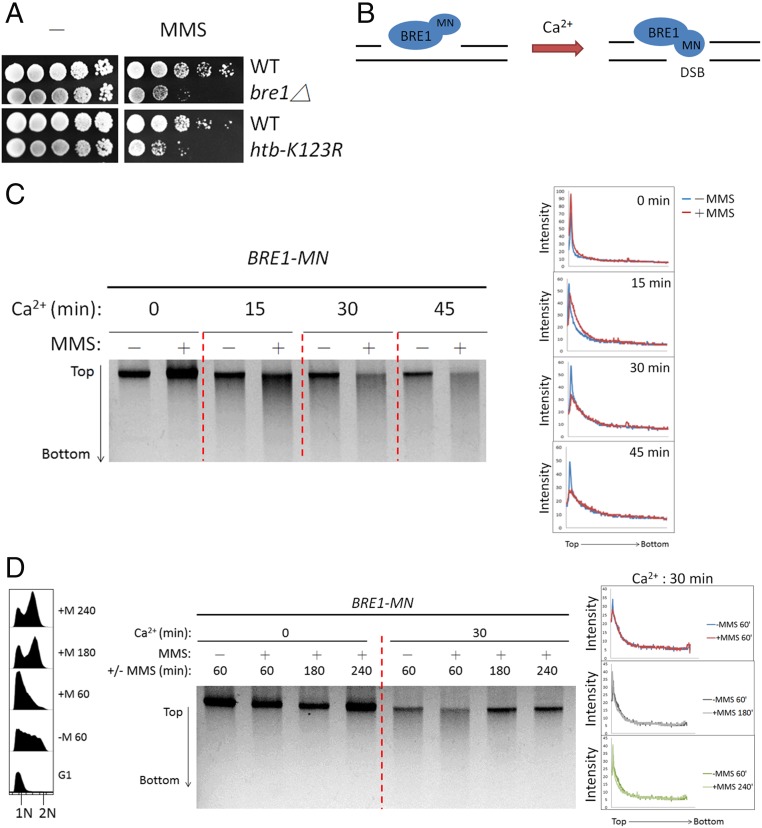

To investigate the functional significance of H2Bub in replication of damaged DNA, we examined the sensitivity of htb-K123R cells (lacking monoubiquitylation of H2B on lysine 123) to agents that trigger replicative DNA damage. We found that htb-K123R mutants and BRE1-deletion cells exhibited growth defects in response to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), which methylates DNA and causes DNA fork stalling (Fig. 1A). To directly address whether Bre1 is targeted to DNA lesions induced by MMS, we used the chromatin endogenous cleavage (ChEC) method (40, 41). This method involves the fusion of the protein of interest to micrococcal nuclease (MN); the recruitment of the MN-fusion protein to any chromatin structure other than a DSB can be detected, as DNA is digested upon MNase activation by Ca2+ (40, 41). We created a yeast strain carrying a chimeric Bre1 with MN fused to its C terminus (Fig. 1B). After 2 h of incubation with or without 0.05% MMS, cells were collected, permeabilized with digitonin, and treated with Ca2+ for different times to activate MNase (Materials and Methods). Total DNA was extracted and resolved on agarose gels. In the absence of Ca2+, a single DNA band of high molecular weight was observed (Fig. 1C, time 0). In the presence of both MMS and Ca2+, DNA was digested over time by Bre1-MN. Notably, a smear below the high-molecular-weight band gradually appeared in the MMS-treated cell lane, whereas the presence of free micrococcal nuclease in nuclei (nlsMN, Fig. S1A) did not lead to significant digestion of genomic DNA. MMS treatment increased both the kinetics and the extent of DNA digestion by Bre1-MN (Fig. 1C; relative to −MMS at 30 and 45 min). Quantification of intensity confirmed that chromatin was digested by Bre1-MN in a manner dependent on MMS treatment (Fig. 1C, Right). Interestingly, we found that DNA digestion by Bre1-MN appeared to require Rad6, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) cognate to Bre1 (Fig. S1B). This was most likely attributable to a stabilizing effect of Rad6 on Bre1 protein levels (Fig. S1C). Next, we investigated whether the MMS-induced recruitment of Bre1 to chromatin is linked to DNA replication. To this end, Bre1-MN cells were synchronized in G1 and released in the presence of 0.033% MMS for different times, and samples were collected for ChEC analysis (Fig. 1D). Such analysis revealed that Bre1-MN was bound to MMS-damaged DNA during S phase and that binding gradually diminished after completion of DNA replication (Fig. 1D, agarose gel; compare +MMS relative to –MMS at 60–240 min; see also the FACS analysis data and the intensity quantification of the top DNA bands). To rule out the possibility that Bre1-MN is recruited in S phase in the absence of DNA damage, we synchronized Bre1-MN cells in G1 and then released them in the absence of DNA damage (Fig. S1D). DNA digestion by Bre1-MN did not change during the cell cycle, indicating that Bre1 recruitment to chromatin is coupled to MMS-induced DNA damage. Fractionation assays on total cell extracts also revealed a measurable increase in the amount of Bre1 associated with chromatin (Fig. S1E). Under nondamage conditions, Bre1 is recruited to promoters and travels with RNA pol II during transcription elongation (34, 42). However, it has been shown recently that DNA damage-induced RNA pol II stalling triggers H2B deubiquitylation, likely at transcribing regions (43). Thus, our results suggest that, in response to DNA damage, Bre1 might dissociate from transcription units and subsequently be redistributed to non-DSB chromatin in the presence of damage, most likely to sites with replication problems.

Fig. 1.

Bre1-mediated H2B ubiquitylation in response to MMS-induced DNA damage is coupled to DNA replication. (A) Loss of Bre1-mediated H2Bub results in MMS sensitivity. Ten-fold serial dilutions of isogenic wild-type (WT), bre1Δ, and htb-K123R cells were spotted onto YPD or YPD containing 0.02% MMS and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. (B) Schematic representation of the recruitment of Bre1-MN fusion protein. The Bre1-MN fusion protein will create a DSB only if it is bound to chromatin in the presence of Ca2+ ions. (C) Bre1 is targeted to MMS-induced DNA lesions. After 2 h in the presence or absence of 0.05% MMS, Bre1-MN cells were collected and analyzed by in vivo ChEC assay. (Right) The quantification of band signal intensity. (D) MMS-induced recruitment of Bre1 to chromatin is linked to DNA replication. Bre1-MN cells were synchronized in G1 and released in the presence or absence of 0.033% MMS before being collected and analyzed by in vivo ChEC assay. (Left) The DNA content profiles. (Right) The quantification of band signal intensity.

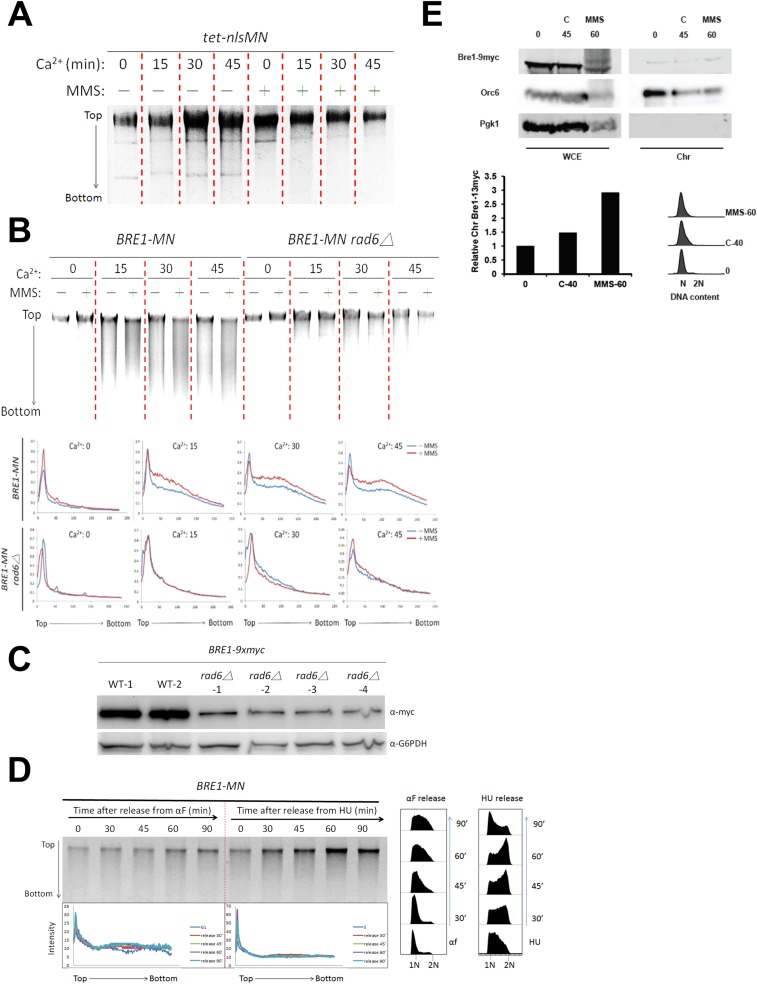

Fig. S1.

(A) The specificity of DNA damage-induced Bre1-MN chromatin cleavage. Wild-type cells transformed with plasmid (pTARtet-nlsMN) were grown in the presence of 5 μg/mL doxycyclin and incubated with or without 0.05% MMS for 2 h. Cells were collected and analyzed by in vivo ChEC assay. (B) Bre1 recruitment to chromatin after DNA damage is Rad6-dependent. Bre1-MN and Bre1-MN rad6Δcells were collected and analyzed by in vivo ChEC assay. (Lower panels) The quantification of band signal intensity. (C) Bre1 protein levels are stabilized by Rad6. Wild-type and rad6Δ cells with 9× myc tag were collected. Western blot was used to analyze the protein level of Bre1 with antibodies against Myc (Bre1-9Xmyc). G6PDH was used as a loading control. The (−) numbers indicate independent clones of wild-type (WT) or rad6Δ strain. (D) The recruitment of Bre1 is not enhanced at any cell-cycle stage. Bre1-MN cells were synchronized in G1 phase by α-factor (αF) or in S phase by HU and released into fresh YPD medium for the indicated times. Cells were collected and analyzed by in vivo ChEC assay. (Bottom) Quantification of band signal intensities. (Right) DNA content profiles. (E) Fractionation assays revealed a measurable increase in the amount of chromatin-associated Bre1 associated upon treatment with MMS. WT and rad6Δ strains expressing 9XMyc-tagged Bre1 were synchronized with α-factor for 3 h and released into fresh medium with or without 0.033% MMS. Cultures were inactivated with 0.1% sodium azide, and chromatin fractionation was performed as described (56). Levels of Bre1-9myc in chromatin were quantified and normalized to Orc6 levels from the same fraction. Cell-cycle profiles were analyzed by FACS.

H2Bub Is Necessary for Maintenance of Replication Fork Stability After MMS Treatment.

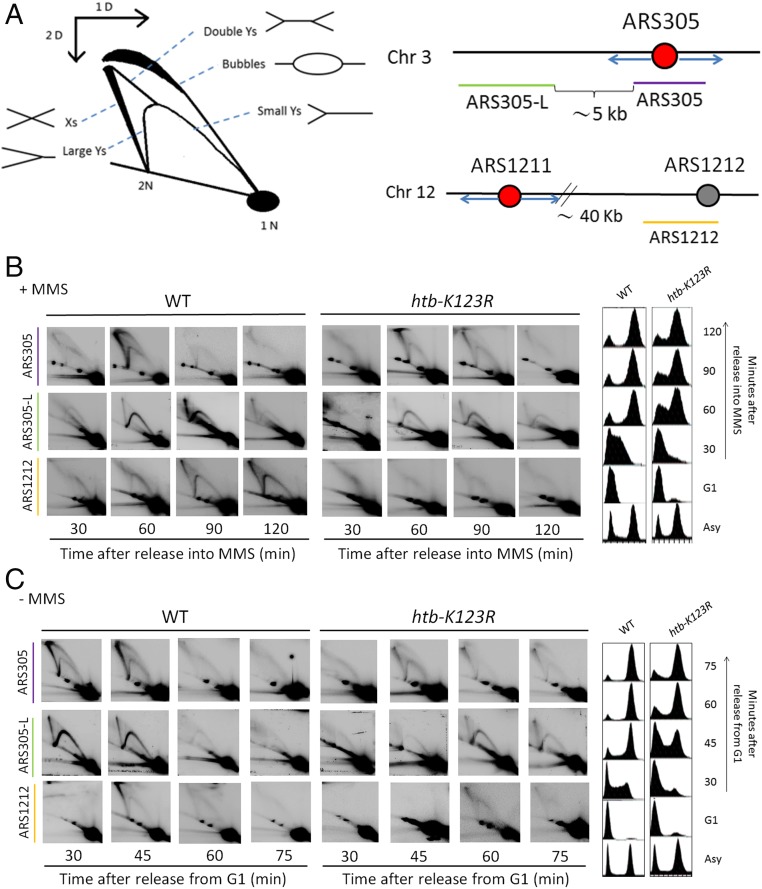

To directly examine the effect of MMS on the initiation and progression of the replication fork, we monitored replication intermediates (RIs) in wild-type and in mutant cells lacking H2Bub (htb-K123R mutant, Fig. S2A) by 2D gel electrophoresis (44). To efficiently detect short- and long-range replication fork progression, we designed three DNA probes (Fig. 2A): the probe ARS305 identifies the firing of an early origin on chromosome III. The probe ARS305L detects a genomic position in the vicinity (5 kb) of ARS305, whereas the probe ARS1212 labels a late origin 40 kb away from the nearest early origin, ARS1211. Cells were synchronized in G1 and released into MMS-containing media, and DNA samples taken at various time points were analyzed by quantitative 2D gel to follow origin firing and replication fork progression at the early origin ARS305 and the late origin ARS1212 (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2D). In both wild-type and htb-K123R mutants, the early origin ARS305 fired at 60 min after release into MMS, giving rise to bubble structures (Fig. 2B, Top); at the same time the migrating replication forks (Y-intermediates) also reached the ARS305-L region (5 kb from the origin) in wild-type and htb-K123R cells (Fig. 2B, Middle). We found that the late origin ARS1212 was efficiently suppressed in both wild-type and htb-K123R cells in the presence of MMS (Fig. 2B, Bottom) based on the absence of replication bubble formation. Instead, we observed the appearance of a large Y-shaped structure at later time points, indicating the migration of the replication fork from ARS1211 and passive replication of the region around ARS1212 in wild type (Fig. 2B, Bottom). Importantly, the large Y signal was significantly diminished in the htb-K123R mutant (Fig. 2B, Bottom), suggesting that replication forks originating at ARS1211 might progress asymmetrically and/or eventually degenerate before reaching the ARS1212 region.

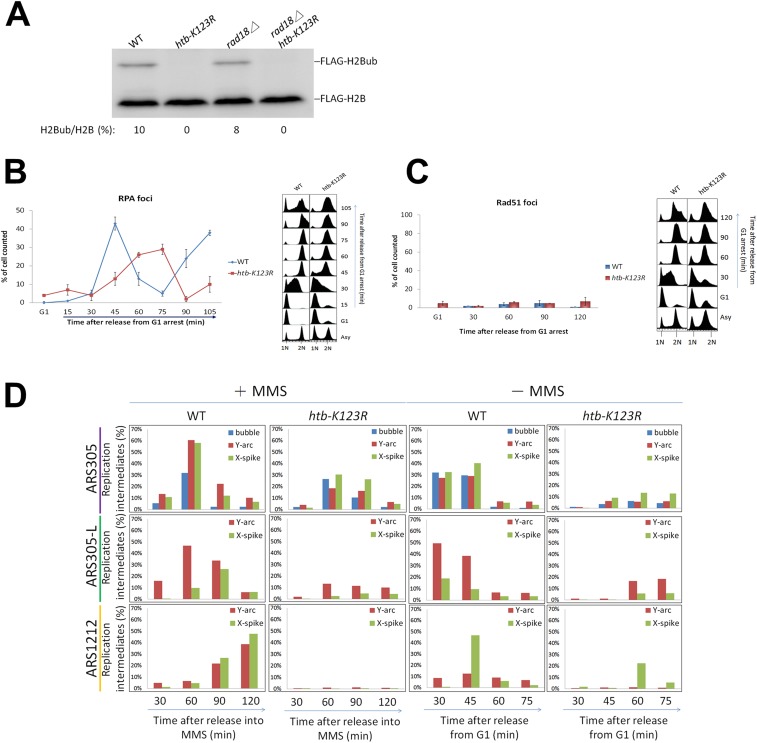

Fig. S2.

(A) RAD18 does not affect monoubiquitylation of H2B. Wild-type, htb-K123R, rad18Δ and rad18Δ htb-K123R cells were collected, and Western blot was used to analyze the ubiquitylation of H2B with antibodies against FLAG (FLAG-H2B). H2B modification levels (%) are shown at the below each lane. They were calculated by dividing FLAG-H2Bub by the total H2B signal (FLAG-H2Bub + FLAG-H2B). (B and C) The kinetics of RPA or Rad51 foci formation in wild-type (WT) and htb-K123R cells under nondamage condition. (Right panels) DNA content profiles. Error bar: SD. (D) Quantification of 2D gel data in Fig. 2 B and C.

Fig. 2.

Two-dimensional gel analysis reveals impaired progression of MMS-damaged forks in the htb-K123R mutant. (A) Schematic representations of probe design and the migration pattern of RIs in 2D gel analysis. (B) htb-K123R cells show defects in replication fork progression in response to MMS. Wild-type and htb-K123R cells were arrested in G1 and released into medium containing 0.033% MMS. Cells were collected at the indicated time points, and DNA was extracted and digested with EcoRV, HindIII, or EcoR1 for ARS305, ARS305-L, or ARS1212 detection, respectively. (C) Two-dimensional gel analysis reveals delayed DNA replication initiation of the htb-K123R mutant under unperturbed conditions. Wild-type and htb-K123R cells were arrested in G1 and released into fresh YPD medium. At the indicated time point, cells were collected and processed as described in B.

Alternatively, it is possible that the progression of the cell cycle is generally altered in the absence of H2Bub. To test this possibility, we examined replication activation by quantitative agarose 2D gel during an unperturbed cell cycle (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2D). Consistent with our previous finding (36), we found that the appearance of replication intermediates (bubbles) at ARS305 was weaker and delayed for ∼15 min after release from G1 (Fig. 2C, Top) in the htb-K123R mutant compared with wild-type cells. By 30 min after release from G1, replication forks had migrated to the ARS305-L as well as the ARS1212 region in wild-type cells, and the migration of replication forks to the same region was delayed until 45 min in the htb-K123R mutant (Fig. 2C, Middle and Bottom). The delayed appearance of migrating forks in the htb-K123R mutant is consistent with the delayed firing of replication origins. The delayed cell-cycle progression in the htb-K123R mutant is possibly caused by a reduction in the expression of several G1 cyclin genes, which leads to slower cell-cycle entry (45). Interestingly, in the presence of DNA damage this delay appears to be partially compensated by an accelerated progression through the cell cycle (Fig. 2B), likely due to a checkpoint defect in the mutant (36).

To further inspect the role of H2Bub during a normal replication cycle, we analyzed the pattern of RPA under nondamage conditions (Fig. S2B). RPA is a complex of ssDNA-binding proteins that plays a central role in DNA replication as well as the activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and various repair pathways (4, 11, 46). Thus, the appearance and disappearance of nuclear RPA foci is indicative of the timing of DNA replication and/or repair. We found that in the htb-K123R mutant RPA foci formation was delayed, consistent with a slower cell-cycle progression of the histone mutant (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2B). However, the numbers of RPA foci were comparable between wild-type and htb-K123R, and we found no evidence of elevated Rad51 foci formation (Fig. S2C) under nondamage conditions, indicating that the RPA foci in htb-K123R cells during a normal cell cycle were not caused by spontaneous DNA damage.

Taken together, although cell-cycle entry is delayed in the absence of H2Bub, the mutation does not significantly compromise origin firing and fork migration during a normal cell cycle. Thus, we conclude that H2Bub is required for maintaining stable fork progression specifically in the presence of DNA damage.

H2Bub Facilitates the Recovery from MMS-Induced Damage Through Rad51-Mediated Repair Pathways.

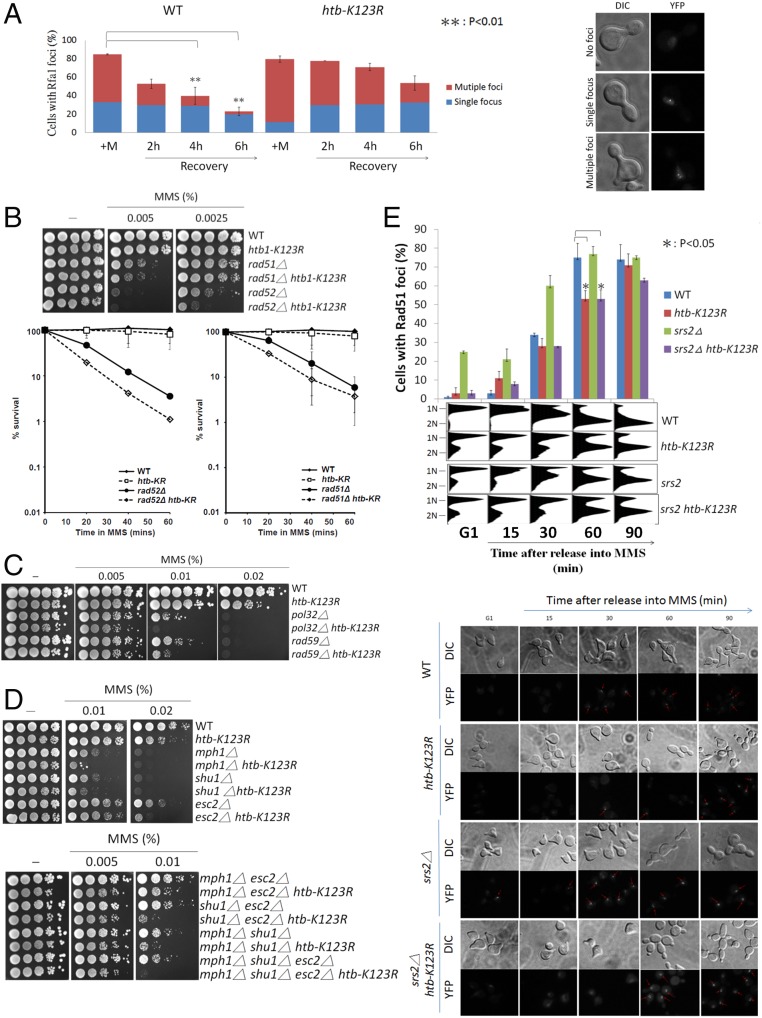

To investigate the consequences of MMS damage for replication fork progression in the htb-K123R mutant, we examined levels of repair intermediates during recovery from an MMS pulse by detecting RPA foci. Indeed, under these conditions htb-K123R cells contained more RPA foci, and these persisted significantly longer than those in wild-type cells (Fig. 3A). This suggests that unrepaired DNA lesions or intermediates containing ssDNA persist in htb-K123R mutants. These findings support the hypothesis that Bre1-mediated H2Bub promotes the processing of MMS-induced DNA damage in S phase.

Fig. 3.

H2Bub contributes to Rad51-mediated repair. (A) Cells lacking H2Bub show increased damage-induced Rfa1 foci and delayed recovery after MMS release. The appearance of ssDNA-binding protein YFP-Rfa1 after transient 0.02% MMS treatment is indicative of MMS-induced DNA damage foci. Cells were sorted into three types: (i) multiple foci—unrepaired DNA with dispersed RPA foci; (ii) single focus—DNA undergoing repair with concentrated RPA foci; and (iii) no foci. The numbers of cells corresponding to each of the three types were scored for 150–200 cells from two independent experiments. Error bars represent SDs of the percentage of cells with RPA foci. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and YFP images are shown on the right. Student t test was done by comparing RPA foci in wild-type cells after recovery for 4 h and 6 h with +M, respectively. **P < 0.01. (B) The htb-K123R mutation enhances MMS sensitivity of rad52Δ, but not rad51Δ cells. (Top) Growth assays on MMS-containing plates. (Bottom) Survival after transient exposure to 0.033% MMS for the indicated times. Data shown are an average of three independent experiments. Error bar: SD. (C) The htb-K123R mutant exhibits an additive relationship with rad59Δ and pol32Δ in response to MMS. (D) The MMS sensitivity of the htb-K123R mutant is enhanced by combination with mph1Δ, shu1Δ, or esc2Δ. (E) H2Bub is involved in the formation of MMS-induced Rad51 foci. Wild-type, htb-K123RΔ, srs2, and htb-K123R srs2Δ cells were transformed with pWJ1278 (YFP-RAD51), arrested in G1, and then released in the presence of 0.02% MMS. The amounts of foci were scored. DIC and YFP images are shown at the bottom of the panel.

The observed sensitivity of the htb-K123R mutant to MMS, as well as its defects in resuming replication fork movement and sustaining fork stability, are phenotypes reminiscent of mutants involved in HR-mediated fork repair (3, 18, 19). We thus examined the genetic interactions of H2Bub with several HR factors. We found that, in response to MMS, the htb-K123R mutant enhanced the sensitivity of rad52Δ, but not that of rad51Δ (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the phenotype of htb-K123R, the relationship between BRE1 and RAD51 deletions was also epistatic (Fig. S3 A and B). In S. cerevisiae, the major Rad51-independent activity of Rad52 is represented by Rad59-dependent single strand annealing (SSA) and Pol32-dependent break-induced replication (BIR) (17, 47). Notably, the htb-K123R mutant showed additive or even synergistic sensitivity to MMS when combined with rad59Δ and pol32Δ (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that H2Bub is epistatic to the Rad51-dependent HR repair process, but appears to act independently of SSA and BIR.

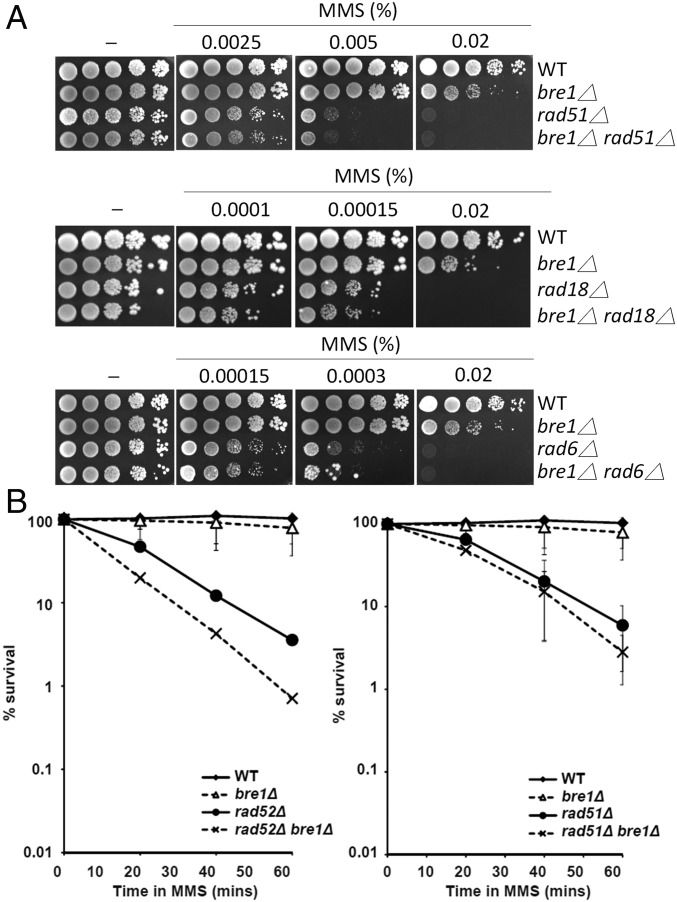

Fig. S3.

(A) Genetic analyses of bre1Δ combined with rad51Δ, rad6Δ and rad18Δ mutants. Viability was determined under conditions of chronic exposure to MMS by spotting 10-fold serial dilutions of each strain onto MMS-containing plates for 3 days. (B) Survival after transient exposure to 0.033% MMS for the indicated times. Data shown is an average of three independent experiments. Error bar: SD.

It has been proposed that the Mph1 DNA helicase and the Shu complex (including Shu1 Psy3, Csm2, and Shu2) facilitate Rad51 functions (48–50). Esc2, a SUMO-like domain-containing factor, has been recently shown to bind replication-associated DNA structures and facilitate local assembly of Rad51 at damaged sites (51). To further define the interaction of H2Bub with these RAD51-dependent pathways, we thus analyzed the genetic interactions of htb-K123R with mph1Δ, shu1Δ, and esc2Δ (Fig. 3D). We found that the deletion of MPH1, SHU1, or ESC2 strongly enhanced the cellular sensitivity of the htb-K123R mutant to MMS. Together, these results imply that H2Bub functions in parallel with SHU1, ESC2, and MPH1 in RAD51-dependent HR.

To address whether H2Bub plays a role in promoting Rad51 recruitment/assembly to damaged sites, we synchronized cells in G1 and released them into S phase with MMS for different periods of time before examining YFP-Rad51 foci. The absence of H2Bub impaired the formation of Rad51 foci in response to MMS (Fig. 3E). In addition, deletion of SRS2, encoding an antirecombinogenic helicase that disrupts Rad51 filaments, did not restore the kinetics of Rad51 recruitment/assembly to wild-type levels in the htb-K123R mutant (Fig. 3E). These results support a role for H2Bub in Rad51-dependent DNA damage processing.

H2Bub Contributes to Both Rad18-Dependent and -Independent Branches of HR-Mediated Damage Tolerance.

DNA damage during S phase can be processed through three pathways, two of which (TS and TLS) are triggered by the ubiquitylation of PCNA and mediated by RAD6-RAD18 (3), and the third of which is a RAD18-independent homologous recombination pathway (Fig. 4A). We found that deletion of RAD18, which encodes the E3 ubiquitin ligase that initiates DDT, increased cell sensitivity of the htb-K123R mutant to MMS in a very subtle manner that became evident only by performing quantitative survival assays, but was not detectable by monitoring growth on MMS-containing plates (Fig. 4B and Fig. S3 A and B). Our finding that htb-K123R did not further sensitize a RAD6 deletion mutant to MMS (Fig. 4C) was consistent with the notion that Rad6 mediates the ubiquitylation of both H2B and PCNA (Fig. 4A). Importantly, the level of H2Bub remained unaffected in rad18Δ cells, indicating that RAD18 deletion did not affect the activity of Rad6 (Fig. S2A). In accordance with the htb-K123R mutant, BRE1 deletion exhibited identical genetic relationships with rad6Δ and rad18Δ (Fig. S3A). Thus, the slight additivity observed here suggests a significant contribution of H2Bub to Rad18-dependent damage processing with some additional, PCNA-Ub–independent functions.

Fig. 4.

H2Bub contributes to PCNA-ub–dependent DNA damage bypass. (A) Schematic representations of DDT pathways. (B) The htb-K123R mutation has minor effects on the MMS sensitivity of rad18Δ mutant. Viability was determined under chronic exposure to MMS by spotting 10-fold serial dilutions of each strain onto MMS-containing plates (Top) or by quantitative survival curves after transient exposure to 0.033% MMS for the indicated times. Data shown are an average of three independent experiments. Error bar: SD. (C–E) The htb-K123R mutation enhances the MMS sensitivity of mutants defective in either TLS or TS. Ten-fold serial dilutions of each mutant were spotted onto YPD containing MMS at the indicated concentrations. (F–H) H2Bub does not affect the modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. (F and G) Wild-type and htb-K123R cells harboring His-tagged Pol30 (PCNA) were treated or untreated (−) with MMS (0.02% or 0.3%) for 90 min. (H) Cells were synchronized at G1 for 3 h with transient exposure to 0.02% MMS for 30 min. Whole-cell extracts were subsequently collected. Ni-NTA affinity chromatography and Western blot analysis using antibodies against ubiquitin, Smt3 (SUMO), and Pol30 were used to analyze PCNA modifications. U1-, U2-, and U3- indicate PCNA modified with mono, di-, and triubiquitin, respectively. S164- and S2127/164 indicate PCNA modified with SUMO at lysine 164 or both lysines 127 and 164, respectively. The asterisk denotes a cross-reactive protein.

Intriguingly, we found that htb-K123R had differential effects on the MMS sensitivity of mutants defective in either TS or TLS (Fig. 4 C–E); whereas the sensitivity of TS mutants (mms2Δ, ubc13Δ) was only mildly affected by htb-K123R, strong synergism was observed in combination with TLS mutants (rev3Δ, rev7Δ). Unlike rev3Δ and rev7Δ, another TLS mutant, rad30Δ, displayed only mild additivity; however, the protein encoded by RAD30, polymerase η, is rather specific for UV damage and does not contribute significantly to the processing of MMS lesions (52). The other exception to the pattern was rad5Δ, which displayed significant synergism with htb-K123R; however, beyond its contribution to TS, the Rad5 protein harbors helicase activity with a function in a poorly described pathway of replicative stress management, which could account for a TS-independent contribution (53). These results indicate that H2Bub likely functions independently of TLS, but appears to contribute to the HR-mediated TS pathway.

We found, however, that damage-induced ubiquitylation and SUMOylation of PCNA were not affected in the htb-K123R mutant during exponential growth (Fig. 4 F and G), which argues against a function of H2Bub upstream of PCNA modifications. To further exclude a direct participation of H2Bub in PCNA-Ub, we observed the appearance of modified PCNA during S phase in a time-course experiment with a strain carrying a His-tagged allele of POL30 (encoding PCNA) in both wild-type and htb-K123R cells (Fig. 4H). Here we noted that the signal of PCNA-Ub in wild-type cells started to decline significantly at 90 min after release from MMS damage, whereas in htb-K123R cells the signal remained high at 90 min and only diminished at 120 min after release from MMS. Consistent with the longer persistence of RPA foci (Fig. 3A), this indicates that DNA damage persists longer in the mutant cells. However, the result also suggests that H2Bub does not affect the initiation of PCNA modification; instead, it may influence damage bypass downstream of PCNA-Ub. Our observation that htb-K123R is synergistic with TLS mutants, but only mildly additive with TS and HR mutants, indicates that H2Bub likely contributes to both branches of HR-mediated damage processing during replication. Taken together, we conclude that H2Bub facilitates Rad18-dependent TS as well as Rad18-independent salvage HR for damage bypass.

Physical Evidence That H2Bub Promotes Recombination-Dependent Bypass of DNA Lesions.

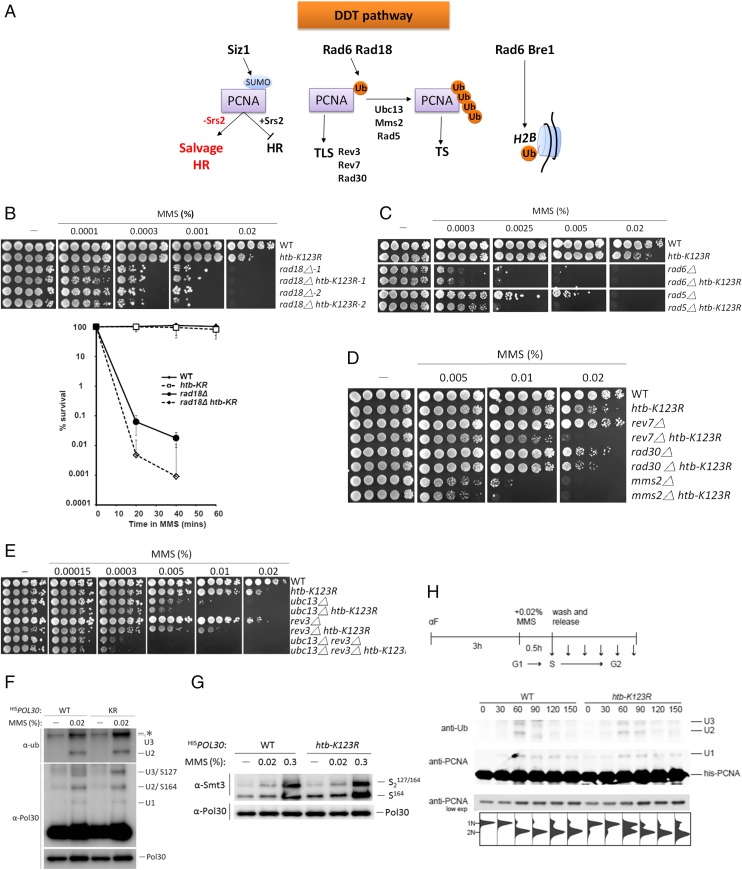

To investigate the role of H2Bub in recombination-mediated damage bypass, we used 2D gel electrophoresis to analyze the profile of replication intermediates formed at ARS305. Synchronized yeast cells were released into S phase in the presence of MMS, and the patterns of replication intermediates were analyzed at different time points during replication. Both the homologous recombination factor Rad51 and the ubiquitin ligase Rad18 promote the formation of X-shaped sister-chromatid junctions (SCJs) at damaged replication forks, which form during replication of damaged templates and accumulate in mutants of the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex due to their impaired resolution (16, 54). We thus compared the amounts of SCJs formed in sgs1Δ and sgs1Δ htb-K123R mutant (Fig. 5A). We found that the level of SCJs, a hallmark of error-free DDT, was significantly reduced in the sgs1Δ htb-K123R double mutant compared with the sgs1Δ single mutant, similar to what has been observed in rad18Δ and rad51Δ mutants (16, 55). This suggests a supportive role for H2Bub in promoting damage tolerance via SCJ formation.

Fig. 5.

H2Bub promotes recombination-mediated bypass of DNA lesions. (A) H2Bub contributes to the formation of MMS-induced recombination-mediated damage bypass. Cells of the indicated mutants were synchronized in G1 and released into medium containing 0.033% MMS. At the indicated time points, cells were collected for 2D gel analysis with a HindIII 5.0-kb fragment (spanning ARS305 and purified from plasmid A6C-110) as probe. FACS analyses and quantification of relative X-molecules (SCJs) of each strain are shown. (B) H2Bub promotes the suppression of rad18Δ MMS hypersensitivity by srs2Δ. Ten-fold serial dilutions of each mutant were spotted onto YPD containing MMS and incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. (C) H2Bub promotes SCJ formation during the salvage HR process. Cells of the indicated mutants were collected and processed for 2D gel and FACS analyses.

During genome replication, HR is inhibited by PCNA SUMOylation, which recruits antirecombinogenic helicase Srs2 (14, 15) to prevent unscheduled and potentially toxic recombination events. It has been demonstrated that this salvage HR pathway, which serves as an alternative to the Rad5-Ubc13-Mms2 pathway, can be released from inhibition by the ablation of SRS2 or SUMO-PCNA (16). When we examined the effects of SRS2 on RAD18 and H2Bub in damage sensitivity assays, we found that deletion of SRS2 alone had additive effects on htb-K123R, thus indicating independent actions. However, although suppression of the MMS sensitivity of rad18Δ cells by srs2Δ was still observable in the htb-K123R background, it was significantly less efficient (Fig. 5B). Thus, we conclude that H2Bub promotes the suppressive effect of enhanced HR on the sensitivity of DDT mutants, although it is not absolutely required. Importantly, the absence of H2Bub suppressed the rescue of SCJ formation by the HR pathway in the sgs1Δ rad18Δ siz1Δ mutant (Fig. 5C). Together, these data lend further support to the notion that, in addition to its contribution to PCNA-Ub–dependent TS, H2Bub also supports HR events independent of the RAD6-RAD18 pathway.

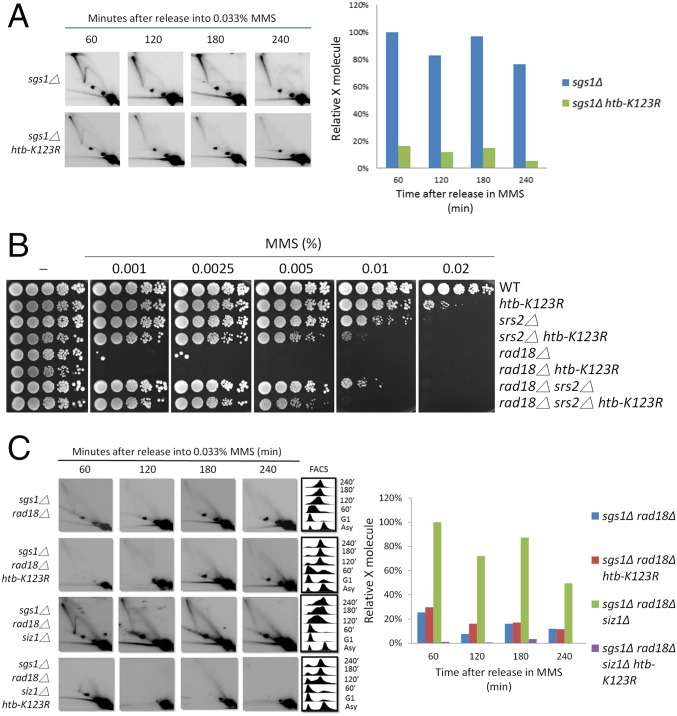

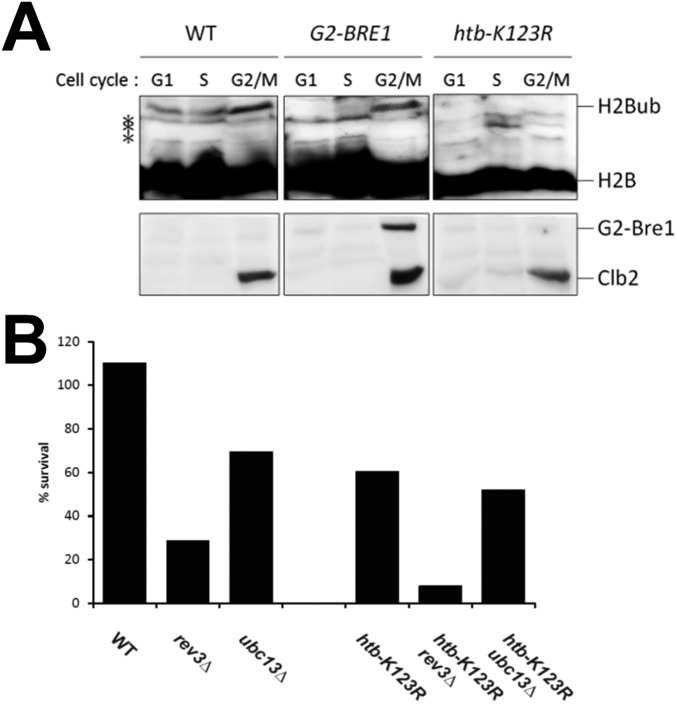

H2Bub Cooperates with DDT to Process Lesions During and After Replication.

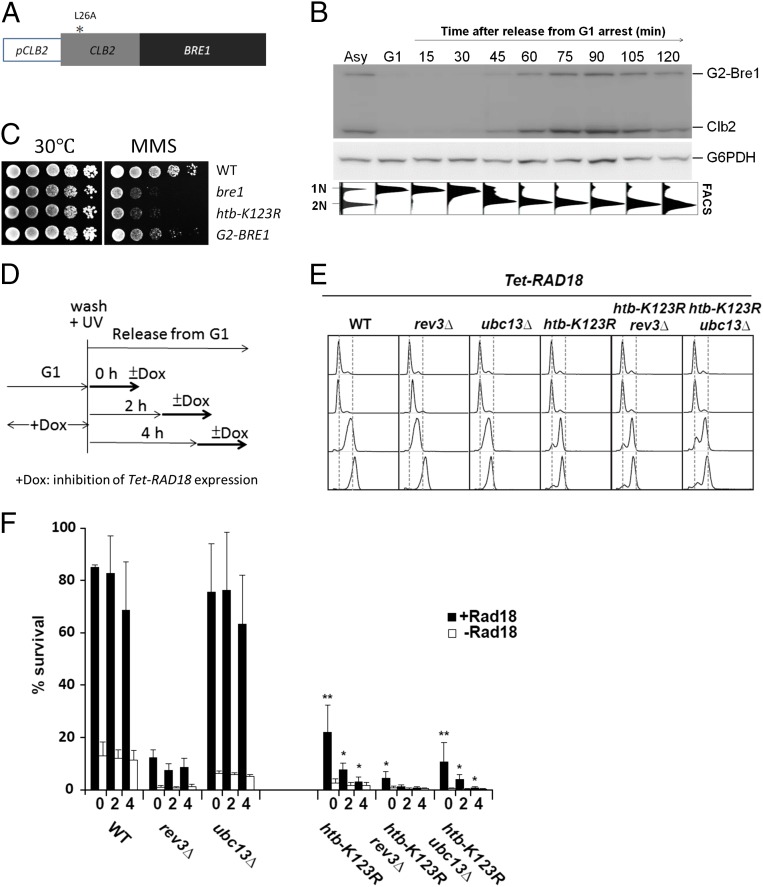

In S. cerevisiae, the RAD6-dependent DNA damage tolerance pathway can be delayed until after genome duplication without any adverse effects (56, 57). To determine at which time during the cell cycle Bre1-mediated H2Bub confers resistance to MMS, we modified BRE1 with a G2-tag (G2-BRE1) (Fig. 6A), which confers the control elements of the mitotic cyclin Clb2 to Bre1 and limits expression of the protein to G2 phase (57). The resulting G2-Bre1 protein and H2Bub were indeed mostly restricted to G2 phase during the cell cycle, as assessed by comparison with Clb2 (Fig. 6B and Fig. S4A). Minute amounts of Bre1 outside of G2 cannot be excluded, but these amounts are likely to be insignificant given its highly selective enrichment in G2. Interestingly, G2-BRE1 cells were sensitive to the replication inhibitor MMS, but their sensitivity was reduced compared with htb-K123R or the bre1 deletion mutant (Fig. 6C), suggesting a role for Bre1 in both S and G2 phase. To further confirm a contribution of H2Bub to postreplicative repair, we introduced the htb-K123R mutation into the Doxycyclin-repressible Tet-RAD18 system, which allows an analysis of DDT independent of genome replication by delaying the expression of RAD18 to the G2 phase (Fig. 6D) (56). As controls for the TLS and TS pathways, respectively, we first analyzed the viability of Tet-RAD18 cells lacking REV3 or UBC13 after UV irradiation (Fig. 6 E and F). Consistent with the published results, deletion of UBC13 had a mild effect on survival during S phase or G2/M, whereas viability was markedly reduced in rev3∆ cells. The viability of htb-K123R cells was significantly diminished even when Rad18 was re-expressed immediately after release from G1 arrest (Fig. 6F), indicating that H2Bub is important for tolerance to UV-induced lesions. Strikingly, the viability of htb-K123R cells was even further reduced when Rad18 re-expression was delayed to late S or G2/M phase (Fig. 6F), whereas in the continuous presence of Rad18 the survival rate of the htb-K123R mutant was ∼50% (Fig. S4B). These results suggest that H2Bub may be required to stabilize the gaps in daughter strands left unrepaired during S phase, and a delay in Rad18 expression renders cells unable to rescue viability via postreplication repair. In this scenario htb-K123R would have a similar impact on cellular survival irrespective of the DDT pathway used. Indeed, we observed that cell viability of the htb-K123R mutant dropped gradually as RAD18 expression was delayed during the cell cycle in both rev3∆ and ubc13∆ backgrounds where only one DDT pathway remains functional (Fig. 6F). These results strongly suggest a protective role of H2Bub for the ssDNA gaps left behind replication and that H2Bub cooperates with the DDT system during and after genome replication.

Fig. 6.

H2Bub facilitates lesions bypass during and after genome replication. (A) Schematic of the G2-BRE1 chimera. The Clb2 promoter (pClb2) and the region encoding 180 amino acids of the N terminus of Clb2 (with an L26A mutation that prevents nuclear export) were fused in front of the ORF of BRE1 at its endogenous locus. (B) G2-BRE1 is expressed specifically at G2/M. G2-BRE1 cells were arrested in G1 and then released into fresh medium. Samples were collected at the indicated time points for Western blot and FACS. Bre1 expression was detected with an antibody against Clb2 (a marker of G2/M phase, which also recognizes G2-Bre1). G6PDH was used as a loading control. (C) Loss of Bre1-mediated H2Bub results in MMS sensitivity. Ten-fold serial dilutions of isogenic wild-type (WT), bre1Δ, htb-K123R, and G2-BRE1 cells were spotted onto YPD or YPD containing 0.02% MMS and then incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. (D) Schematic of Tet-RAD18 induction during and after S phase. Dox: doxycyclin. (E) Cell-cycle profiles of the indicated strains at the time of plating. (F) A protective role of H2Bub for the ssDNA gaps left behind during replication. Cells grown overnight in the absence of Rad18 were synchronized in G1 with α-factor for 3 h, irradiated with 20 J/m2 UV, and released. Rad18 was re-expressed or remained repressed at different times after release from G1. Percentage survival was calculated with number of colonies in irradiated cells over undamaged control. The graph represents averages from three independent experiments. Error bar: SD; t test: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S4.

(A) G2-BRE1 limited H2Bub at G2/M. G2-BRE1 cells were arrested in G1 and then released into fresh medium. Samples were collected at the indicated cell-cycle stages for Western blot. H2Bub was detected with an antibody against FLAG-H2B. The antibody against Clb2 is a marker of G2/M phase, which also recognizes the G2-Bre1 protein. G6PDH was used as a loading control. (B) Survival rate in the continuous presence of Rad18 control strains. Cells grown in the presence of Rad18 were irradiated with 20 J/m2 UV. Percentage of survival was calculated with number of colonies in irradiated cells over undamaged control.

Discussion

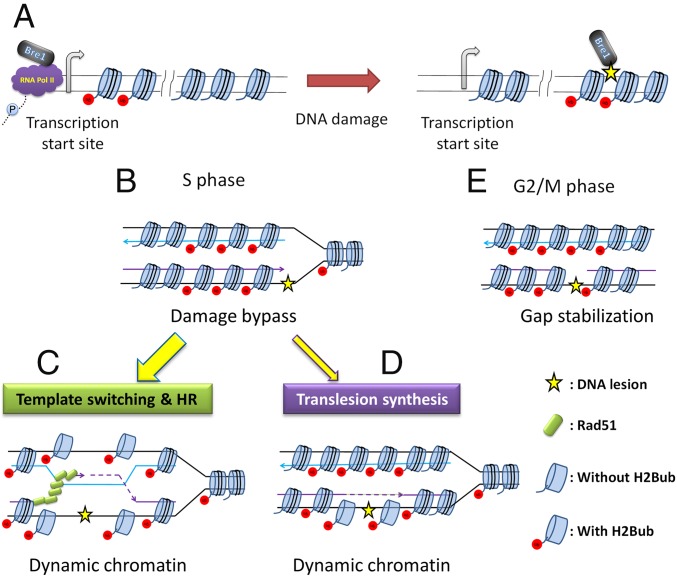

Here, we report that Bre1-mediated monoubiquitylation of histone H2B at lysine 123 (Bre1-H2Bub) contributes to DNA lesion bypass in S. cerevisiae. We demonstrate that Bre1 is recruited to non-DSB chromatin in a replication- and damage-coupled manner. In the absence of Bre1 or H2Bub, cells become sensitive to MMS and accumulate unrepaired DNA lesions and/or replication intermediates enriched with RPA foci indicative of ssDNA gaps. We also found that H2Bub is essential for the bypass of UV-induced lesions during and after bulk genome duplication. These phenotypes appear to arise from a deregulation of the DDT and HR pathways during and after genome duplication. We propose that Bre1-H2Bub facilitates lesion bypass by regulating chromatin dynamics in response to replicative DNA damage (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

A model for how Bre1-H2Bub contributes to lesion bypass in S. cerevisiae. (A) Bre1 is recruited to DNA lesions to modify H2B upon DNA damage. (B) Bre1-H2Bub maintains the stable progression of ongoing replication by promoting HR-mediated damage tolerance (C), whereas its influence on translesion synthesis appears limited (D). At G2/M phase (E), Bre1-H2Bub may mediate the activation of the G2/M checkpoint, thereby setting the stage for dedicated lesion processing in response to replicative DNA damage to fill the ssDNA gaps left from S phase.

The Role of Chromatin Dynamics at Damaged Forks.

In eukaryotes, lesion bypass or DNA repair must take place in the context of chromatin (20–25). Several reports have indicated that certain chromatin regulators contribute to genome stability during DNA replication and repair (26–28, 58), for example, Ino80 complex, an ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzyme. Ino80 family members act during replication to promote recovery of stalled replication forks (59, 60), probably through regulating the activation of the DNA damage checkpoint (61, 62) and resolving transcription-replication fork collision (63). Moreover, Ino80 is also implicated in damage tolerance control and mitotic homologous recombination (61, 64). In addition to chromatin remodelers, nucleosome assembly and reassembly during DNA replication and repair are facilitated by highly conserved histone chaperones, such as the CAF-1 complex. CAF-1 plays a role in maintaining the stability of replication forks (65), as well as in promoting replication restart at stalled forks by mediating Rad51-dependent template switching (66).

The interaction between histone modifications and DDT remains poorly studied. H2Bub has been demonstrated to disrupt higher-order chromatin structure in vitro (67). This effect on higher-order structure is congruent with the suggestion that human H2Bub facilitates DNA DSB repair via relaxation of chromatin structure (38, 39). However, H2B ubiquitylation has also been reported to increase nucleosome stability in vivo, which is consistent with the finding that levels of H2Bub correlate with genome-wide nucleosome occupancy (68, 69). Such enhancement of nucleosome stability may restrict access of replication and repair machinery to the underlying DNA. These seemingly contradictory observations in vitro and in vivo are not necessarily mutually exclusive. We have demonstrated that Bre1 is recruited to promoters and travels with RNA pol II during transcription elongation (34, 42). It has been shown recently that DNA damage-induced RNA pol II stalling triggers H2B de-ubiquitylation, likely at transcribing regions (43). We thus propose that extra- or intracellular signals such as DNA lesions may shift ubiquitylation of H2B away from transcribing nucleosomes toward damaged sites or replication forks (Fig. 7 A and B). Such ubiquitylation could be dynamic and may be predicted to induce fluctuations between permissive and restrictive chromatin structure through cycles of ubiquitylation and de-ubiquitylation (70). In the absence of H2Bub, chromatin may exist as a restrictive and static structure, which is not conducive to the progression of processes on the DNA template.

H2Bub Facilitates DNA Damage Tolerance and Homologous Recombination.

It has been reported that Bre1-H2Bub is maintained on replicating DNA and contributes to stable progression of replication forks in the presence of hydroxyurea (36, 37). In the current study, we demonstrate that replicative DNA damage induces the recruitment of Bre1 to chromatin (Fig. 1). This finding extends our understanding of the role of H2Bub on damaged replication templates. We propose that the role of Bre1-H2Bub at damaged forks is to facilitate the initiation of damage processing by mediating chromatin dynamics (Fig. 7 C and D). This hypothesis is supported by our finding that the levels of MMS-induced Rad51 foci are significantly reduced, especially during S phase, in the absence of H2Bub (Fig. 3E). In addition, deletion of the SRS2 helicase, which disrupts Rad51 filaments, does not restore the kinetics of Rad51 recruitment/assembly to wild-type levels in the htb-K123R mutant. From this result, one could argue that H2Bub may directly affect the recruitment of Rad51 and has no influence on Srs2 directly or indirectly. Overall, we conclude that Bre1-H2Bub may promote the recruitment of Rad51 to damage sites by mediating chromatin dynamics in the context of recombination-mediated damage bypass. Remarkably, H2Bub is also required for the activation of homologous recombination in the absence of the canonical DDT pathways (Fig. 5C). We thus suggest that H2Bub may have a general role in promoting recombination through the regulation of chromatin status.

H2Bub Promotes Postreplication Repair During and After Genome Duplication.

In S. cerevisiae, the RAD6-dependent DNA damage tolerance pathway can be delayed until after genome duplication with no adverse consequences (56, 57). A possible role of chromatin in the DNA damage response was described in the access–repair–restore (ARR) model (71). In the ARR model, the damaged chromatin becomes more accessible to enable DNA repair, and this is followed by the restoration of chromatin organization (23–25). We found that cells in which Bre1-mediated H2Bub was restricted to G2/M phase (G2-BRE1) were sensitive to MMS, indicating that H2Bub may participate in repair processes during genome duplication (Fig. 6C). We also found that H2Bub is essential for lesion bypass during and after genome duplication (Fig. 6F). Hence, we argue that the Bre1-H2Bub–mediated process described here fits with the ARR model and may contribute to DDT for processing base lesions during and after genomic replication.

One of our most surprising findings was that delaying RAD18 expression in the htb-K123R mutant to G2/M phase becomes detrimental (Fig. 6F), raising the possibility that H2Bub plays an additional role specifically during postreplicative action of the DDT system. H2Bub is implicated in DNA damage checkpoint activation (36). Thus, H2Bub may play a further role in post replication repair during G2/M checkpoint activation to maintain the stability of unrepaired ssDNA gaps. Hence, we propose a cell-cycle dependent model for the role of H2Bub in lesion bypass: during S phase, Bre1-H2Bub maintains the stable progression of ongoing replication by promoting recombination-mediated DDT. At G2/M phase, Bre1-H2Bub mediates the activation of the G2/M checkpoint, thereby setting the stage for dedicated repair reactions (Fig. 7E).

In summary, these data have extended the known range of H2Bub cellular functions to include DNA damage tolerance during and after genome duplication. H2Bub in chromatin facilitates the filling of ssDNA gaps by regulating chromatin status, thereby helping to maintain genome integrity.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains and Growth Conditions.

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. For gene disruptions, the indicated gene was replaced with the KanMX gene (deletion library from the Saccharomyces Genome Database) or disrupted through a PCR-based strategy (72). G2-BRE1 strains were constructed by replacing the BRE1 promoter with a fragment containing the CLB2 promoter and the amino terminal end of Clb2. Thus, the resulting Bre1 protein contained the N-terminal 180 amino acids of Clb2 (57). His− PCNA strains were constructed as previously described (73). All yeast cells were supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) dextrose in YPD medium, except cells for microscope experiments, which were grown in SC medium. All analyses were performed during the log phase of growth. Cells were arrested in G1 by the addition of a-factor to a final concentration of 100 ng/mL (bar1Δ strain) for 3 h. Cells were released from G1 arrest by washing with prewarmed medium twice before being resuspended in fresh media containing MMS (Sigma-Aldrich).

MMS Sensitivity Assays.

For drop assays, 10-fold serial dilutions of exponential yeast cultures were dropped onto freshly prepared plates containing the indicated concentrations of MMS and were incubated at 30 °C for 3 d. For quantitative survival curves, exponentially growing yeast cultures with the same density were treated with 0.033% MMS for the indicated times. Cells were then washed once with 2.5% (vol/vol) sodium thiosulfate, resuspended in water, and plated on YPD plates. Colonies were counted 3 d after plating, and survival was normalized to the undamaged condition.

Two-Dimensional Agarose Gel Electrophoresis.

Total genomic DNA was extracted according to the protocol of the QIAGEN Genomic DNA Handbook, using genomic-tip 100/G columns (a detailed protocol is provide in SI Materials and Methods). Two-dimensional gels were prepared and run as previously described (74). The DNA samples were digested by the enzyme indicated in the figures and then transferred to a Nylon Gene Screen Plus membrane (NEN) for Southern blotting analysis with specific probes against the loci. Primers used for amplification of the probes are available upon request. Signals were detected using a PhosphorImager Typhoon FLA 7000 (GE Healthcare) and quantified as previously described (75).

Detection of Yeast PCNA Modification.

His-tagged PCNA was isolated with Ni-NTA agarose under denaturing conditions (a detailed protocol is provided in SI Materials and Methods) and detected by Western blotting as described previously (73).

FACS.

For DNA content analysis, ∼1 × 107 cells were collected at each time point, suspended in ice-cold 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and stored at −80 °C. Cells were washed twice with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), and RNA and proteins were removed by RNaseA (0.4 mg/mL) and proteaseK (1 mg/mL) treatment. Finally, cells were stained with SYBR GREEN I at 4 °C overnight. The cell size and DNA were examined on a FACSCanto II (BD).

Microscopy.

Yeast cells were grown in SC medium, and at each time point, cells were collected and fixed with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde for 5 min at 25 °C, washed twice with PBS, and then stained with DAPI (45 μg/mL). Image of cells were obtained using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped with a Coolsnap HQ Digital Monochrome CCD Camera (Photometrics) under the control of METAMORPH software. All fluorescence signals were imaged with a 100× oil objective.

In Vivo ChEC Analysis.

In vivo ChEC assays were performed as previously reported (40, 41). Yeast cells from 50 mL cultures grown under different conditions were arrested with 0.1% sodium azide. For cleavage induction, digitonin-permeabilized cells were incubated with 2 mM CaCl2 at 30 °C under gentle agitation. Total DNA was isolated (a full version of the protocol is provided in SI Materials and Methods) and resolved on 0.8% agarose gels. Gels were imaged, and the signal profile was quantified using ImageJ. Each ChEC experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Determination of Cell Recovery After UV Irradiation.

Tet-RAD18 cells were pregrown in YPD containing 2 mg/mL doxycyclin to repress RAD18 expression, and cells were then synchronized in G1 with 10 μg/mL α-factor for 3 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in water and UV-irradiated at 254 nm before being released into YPD with doxycyclin to maintain RAD18 repression. At the indicated times, cells were plated directly onto YPD with or without doxycyclin for colony counting.

SI Materials and Methods

Denaturing Ni-NTA Pull-Down Assay.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as reported (73) with the following modifications: Yeast cells (∼109) from a 50-mL culture were collected and placed on ice. Pellets were resuspended in 5 mL ice-cold ddH2O, and then 0.8 mL of NaOH/βME buffer [1.85 M NaOH, 7.5% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol] was added and pellets were put on ice for 20 min. After addition of 0.8 mL of TCA solution [55% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid in ddH2O] and vortexing, the suspension was placed on ice for 20 min. Pellets were collected and washed with ice-cold acetone once. The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were resuspend in 1 mL of buffer A (6 M guanidine HCl, 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0.) with shaking at room temperature (RT) to solubilize precipitates completely. Prewashed 20 μL Ni-NTA agarose was added to the solubilized precipitates with 0.05% Tween-20 and 10 mM imidazole, followed by incubation at RT overnight on a nutator. Ni-NTA agarose beads were collected and washed two times with 1 mL of buffer A (6 M guanidine HCl, 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, with 0.05% Tween-20) and four times with 1 mL of buffer C (8 M urea, 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.3, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.3, with 0.05% Tween-20). The supernatant was removed completely after the final wash. Samples were suspended in 30 μL of HU (high urea) buffer [8 M urea, 200 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 5% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.1% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, 1.5% (wt/vol) DTT] and denatured at 60 °C for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged briefly before analyzing by SDS/PAGE.

Genomic DNA Extraction for ChEC Assay.

ChEC-treated cells from a 50-mL culture were collected, resuspended in 0.75 mL Y1 buffer (1 M sorbitol, 100 mM EDTA, 14 mM β-ME), and incubated with 75 μL Zymoylase 100T (Seikagaku) for 20 min at 30 °C. The spheroplasts were collected, resuspended in 0.37 mL of 50 mM TrisCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM Na2 EDTA, and incubated with 16 μL of 10% (vol/vol) SDS for 30 min at 65 °C. Then the samples were mixed with 85 μL of 5 M potassium acetate and placed on ice for 1 h. After 5 min of centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a fresh microfuge tube and the DNA was precipitated with 2.5 vol of ice-cold 100% ethanol at −20 °C for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in 0.3 mL Tris-EDTA (TE) with 2 μL RNaseA (10 mg/mL) for 30 min at 37 °C and then treated with 1 vol phenol chloroform-isoamilic alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitated with 2.5 vol ethanol at −20 °C overnight. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μL TE buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 1 mM EDTA).

Genomic DNA Extraction for Agarose 2D Gel Analysis.

Yeast cells (∼109) were collected and resuspended in 5 mL of Y1 buffer (1 M sorbitol, 100 mM EDTA, 14 mM β-ME) plus 500 μL Zymoylase 100 T (Seikagaku) and incubated for 20 min at 30 °C. Spheroplasts were collected and resuspeneded in 4 mL of G2 buffer [800 mM guandine HCl, 30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 30 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 5% (vol/vol) Tween-20, 0.5% Triton X-100] with 100 μL RNaseA (10 mg/mL) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. A total of 150 μL of Proteinase K (20 mg/ ml) was then added for 2 h at 50 °C and followed at 30 °C overnight. After centrifugation, supernatant was diluted with an equal volume of QBT buffer [750 mM NaCl, 50 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer, pH 7.0, 15% (vol/vol) isopropanol, 0.15% Triton X-100] and loaded on a genomic-tip 100G column (QIAGEN). Columns were washed twice with 7.5 mL of buffer QC [1 M Nacl, 50 mM Mops, pH 7.0, 15% (vol/vol) isopropanol] and eluted with 5 mL of buffer QF [1.25 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.5, 15% (vol/vol) isopropanol] in glass tubes (Kimble). DNA was precipitated with isopropanol and pelleted by centrifugation at 8,500 × g for 10 min. Pellets were washed twice with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and resuspended in Tris (10 mM, pH 8.0) and stored at 4 °C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Jentsch and Carol Newlon for plasmids; Michael Lisby and Félix Prado for yeast strains; Xiaolan Zhao for the ARS1212 probe sequence; Duncan Wright of the Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology (ICOB) for manuscript editing; Shao-Chun Hsu of Imaging Core, ICOB, and Néstor García-Rodríguez of the Institute of Molecular Biology for technical assistance. This work was supported by an EMBO (European Molecular Biology Organization) short-term fellowship (to C.-F.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612633114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lopes M, Foiani M, Sogo JM. Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol Cell. 2006;21(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashimoto Y, Ray Chaudhuri A, Lopes M, Costanzo V. Rad51 protects nascent DNA from Mre11-dependent degradation and promotes continuous DNA synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(11):1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419(6903):135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies AA, Huttner D, Daigaku Y, Chen S, Ulrich HD. Activation of ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is mediated by replication protein a. Mol Cell. 2008;29(5):625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedberg EC. Suffering in silence: The tolerance of DNA damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(12):943–953. doi: 10.1038/nrm1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haracska L, et al. A single domain in human DNA polymerase iota mediates interaction with PCNA: Implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(3):1183–1190. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1183-1190.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR. Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: A possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2004;14(4):491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehmann AR, et al. Translesion synthesis: Y-family polymerases and the polymerase switch. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(7):891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelter P, Ulrich HD. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature. 2003;425(6954):188–191. doi: 10.1038/nature01965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branzei D. Ubiquitin family modifications and template switching. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(18):2810–2817. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minca EC, Kowalski D. Multiple Rad5 activities mediate sister chromatid recombination to bypass DNA damage at stalled replication forks. Mol Cell. 2010;38(5):649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanoli F, Fumasoni M, Szakal B, Maloisel L, Branzei D. Replication and recombination factors contributing to recombination-dependent bypass of DNA lesions by template switch. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(11):e1001205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papouli E, et al. Crosstalk between SUMO and ubiquitin on PCNA is mediated by recruitment of the helicase Srs2p. Mol Cell. 2005;19(1):123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Sacher M, Hoege C, Jentsch S. SUMO-modified PCNA recruits Srs2 to prevent recombination during S phase. Nature. 2005;436(7049):428–433. doi: 10.1038/nature03665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branzei D, Vanoli F, Foiani M. SUMOylation regulates Rad18-mediated template switch. Nature. 2008;456(7224):915–920. doi: 10.1038/nature07587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lydeard JR, Jain S, Yamaguchi M, Haber JE. Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature. 2007;448(7155):820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature06047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand RP, Lovett ST, Haber JE. Break-induced DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(12):a010397. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krogh BO, Symington LS. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:233–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.House NC, Koch MR, Freudenreich CH. Chromatin modifications and DNA repair: Beyond double-strand breaks. Front Genet. 2014;5:296. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papamichos-Chronakis M, Peterson CL. Chromatin and the genome integrity network. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(1):62–75. doi: 10.1038/nrg3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ransom M, Dennehey BK, Tyler JK. Chaperoning histones during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2010;140(2):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groth A, Rocha W, Verreault A, Almouzni G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell. 2007;128(4):721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soria G, Polo SE, Almouzni G. Prime, repair, restore: The active role of chromatin in the DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2012;46(6):722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polo SE, Almouzni G. Chromatin dynamics after DNA damage: The legacy of the access-repair-restore model. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015;36:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falbo KB, et al. Involvement of a chromatin remodeling complex in damage tolerance during DNA replication. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(11):1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niimi A, Chambers AL, Downs JA, Lehmann AR. A role for chromatin remodellers in replication of damaged DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7393–7403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wurtele H, et al. Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation and the response to DNA replication fork damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(1):154–172. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05415-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang WW, et al. A conserved RING finger protein required for histone H2B monoubiquitination and cell size control. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):261–266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robzyk K, Recht J, Osley MA. Rad6-dependent ubiquitination of histone H2B in yeast. Science. 2000;287(5452):501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song YH, Ahn SH. A Bre1-associated protein, large 1 (Lge1), promotes H2B ubiquitylation during the early stages of transcription elongation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(4):2361–2367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood A, et al. Bre1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for recruitment and substrate selection of Rad6 at a promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11(1):267–274. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00802-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleming AB, Kao CF, Hillyer C, Pikaart M, Osley MA. H2B ubiquitylation plays a role in nucleosome dynamics during transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;31(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao CF, et al. Rad6 plays a role in transcriptional activation through ubiquitylation of histone H2B. Genes Dev. 2004;18(2):184–195. doi: 10.1101/gad.1149604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitaliano-Prunier A, et al. H2B ubiquitylation controls the formation of export-competent mRNP. Mol Cell. 2012;45(1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin CY, et al. H2B mono-ubiquitylation facilitates fork stalling and recovery during replication stress by coordinating Rad53 activation and chromatin assembly. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(10):e1004667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trujillo KM, Osley MA. A role for H2B ubiquitylation in DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2012;48(5):734–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyal L, et al. Requirement of ATM-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2B for timely repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell. 2011;41(5):529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura K, et al. Regulation of homologous recombination by RNF20-dependent H2B ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2011;41(5):515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmid M, Durussel T, Laemmli UK. ChIC and ChEC: Genomic mapping of chromatin proteins. Mol Cell. 2004;16(1):147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González-Prieto R, Muñoz-Cabello AM, Cabello-Lobato MJ, Prado F. Rad51 replication fork recruitment is required for DNA damage tolerance. EMBO J. 2013;32(9):1307–1321. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao T, et al. Histone H2B ubiquitylation is associated with elongating RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(2):637–651. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.637-651.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao P, Meas R, Dorgan KM, Smerdon MJ. UV damage-induced RNA polymerase II stalling stimulates H2B deubiquitylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(35):12811–12816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403901111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. The localization of replication origins on ARS plasmids in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1987;51(3):463–471. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmermann C, et al. A chemical-genetic screen to unravel the genetic network of CDC28/CDK1 links ubiquitin and Rad6-Bre1 to cell cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):18748–18753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115885108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300(5625):1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lydeard JR, et al. Break-induced replication requires all essential DNA replication factors except those specific for pre-RC assembly. Genes Dev. 2010;24(11):1133–1144. doi: 10.1101/gad.1922610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi K, Szakal B, Chen YH, Branzei D, Zhao X. The Smc5/6 complex and Esc2 influence multiple replication-associated recombination processes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(13):2306–2314. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mankouri HW, Ngo HP, Hickson ID. Shu proteins promote the formation of homologous recombination intermediates that are processed by Sgs1-Rmi1-Top3. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(10):4062–4073. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mankouri HW, Ngo HP, Hickson ID. Esc2 and Sgs1 act in functionally distinct branches of the homologous recombination repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(6):1683–1694. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Urulangodi M, et al. Local regulation of the Srs2 helicase by the SUMO-like domain protein Esc2 promotes recombination at sites of stalled replication. Genes Dev. 2015;29(19):2067–2080. doi: 10.1101/gad.265629.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roush AA, Suarez M, Friedberg EC, Radman M, Siede W. Deletion of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene RAD30 encoding an Escherichia coli DinB homolog confers UV radiation sensitivity and altered mutability. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257(6):686–692. doi: 10.1007/s004380050698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi K, et al. Concerted and differential actions of two enzymatic domains underlie Rad5 contributions to DNA damage tolerance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(5):2666–2677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liberi G, et al. Rad51-dependent DNA structures accumulate at damaged replication forks in sgs1 mutants defective in the yeast ortholog of BLM RecQ helicase. Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):339–350. doi: 10.1101/gad.322605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Branzei D, et al. Ubc9- and mms21-mediated sumoylation counteracts recombinogenic events at damaged replication forks. Cell. 2006;127(3):509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daigaku Y, Davies AA, Ulrich HD. Ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass is separable from genome replication. Nature. 2010;465(7300):951–955. doi: 10.1038/nature09097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karras GI, Jentsch S. The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell. 2010;141(2):255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez-Huici V, et al. DNA bending facilitates the error-free DNA damage tolerance pathway and upholds genome integrity. EMBO J. 2014;33(4):327–340. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papamichos-Chronakis M, Peterson CL. The Ino80 chromatin-remodeling enzyme regulates replisome function and stability. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(4):338–345. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shimada K, et al. Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex promotes recovery of stalled replication forks. Curr Biol. 2008;18(8):566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morrison AJ, et al. Mec1/Tel1 phosphorylation of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex influences DNA damage checkpoint responses. Cell. 2007;130(3):499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kapoor P, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent enhancement of Rad53 kinase activity through the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex. Mol Cell. 2015;58(5):863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poli J, et al. Mec1, INO80, and the PAF1 complex cooperate to limit transcription replication conflicts through RNAPII removal during replication stress. Genes Dev. 2016;30(3):337–354. doi: 10.1101/gad.273813.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsukuda T, et al. INO80-dependent chromatin remodeling regulates early and late stages of mitotic homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8(3):360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clemente-Ruiz M, Prado F. Chromatin assembly controls replication fork stability. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(7):790–796. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pietrobon V, et al. The chromatin assembly factor 1 promotes Rad51-dependent template switches at replication forks by counteracting D-loop disassembly by the RecQ-type helicase Rqh1. PLoS Biol. 2014;12(10):e1001968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fierz B, et al. Histone H2B ubiquitylation disrupts local and higher-order chromatin compaction. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(2):113–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Batta K, Zhang Z, Yen K, Goffman DB, Pugh BF. Genome-wide function of H2B ubiquitylation in promoter and genic regions. Genes Dev. 2011;25(21):2254–2265. doi: 10.1101/gad.177238.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chandrasekharan MB, Huang F, Sun ZW. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates chromatin dynamics by enhancing nucleosome stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(39):16686–16691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907862106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wright DE, Kao CF. (Ubi)quitin’ the h2bit: Recent insights into the roles of H2B ubiquitylation in DNA replication and transcription. Epigenetics. 2015;10(2):122–126. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2014.1003750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smerdon MJ. DNA repair and the role of chromatin structure. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991;3(3):422–428. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90069-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Janke C, et al. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: New fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21(11):947–962. doi: 10.1002/yea.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davies AA, Ulrich HD. Detection of PCNA modifications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;920:543–567. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-998-3_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Friedman KL, Brewer BJ. Analysis of replication intermediates by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:613–627. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fumasoni M, Zwicky K, Vanoli F, Lopes M, Branzei D. Error-free DNA damage tolerance and sister chromatid proximity during DNA replication rely on the Polα/Primase/Ctf4 Complex. Mol Cell. 2015;57(5):812–823. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.