Significance

Cancers appear as disordered mixtures of different cells, which is partly why they are hard to treat. We show here that despite this chaos, tumors show local organization that emerges from cellular processes common to most cancers: the altered metabolism of cancer cells and the interactions with stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. With a multidisciplinary approach combining experiments and computer simulations we revealed that the metabolic activity of cancer cells produces gradients of nutrients and metabolic waste products that act as signals that cells use to know their position with respect to blood vessels. This positional information orchestrates a modular organization of tumor and stromal cells that resembles embryonic organization, which we could exploit as a therapeutic target.

Keywords: cancer metabolism, tumor microenvironment, morphogens, positional information, tumor-associated macrophages

Abstract

The genetic and phenotypic diversity of cells within tumors is a major obstacle for cancer treatment. Because of the stochastic nature of genetic alterations, this intratumoral heterogeneity is often viewed as chaotic. Here we show that the altered metabolism of cancer cells creates predictable gradients of extracellular metabolites that orchestrate the phenotypic diversity of cells in the tumor microenvironment. Combining experiments and mathematical modeling, we show that metabolites consumed and secreted within the tumor microenvironment induce tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to differentiate into distinct subpopulations according to local levels of ischemia and their position relative to the vasculature. TAMs integrate levels of hypoxia and lactate into progressive activation of MAPK signaling that induce predictable spatial patterns of gene expression, such as stripes of macrophages expressing arginase 1 (ARG1) and mannose receptor, C type 1 (MRC1). These phenotypic changes are functionally relevant as ischemic macrophages triggered tube-like morphogenesis in neighboring endothelial cells that could restore blood perfusion in nutrient-deprived regions where angiogenic resources are most needed. We propose that gradients of extracellular metabolites act as tumor morphogens that impose order within the microenvironment, much like signaling molecules convey positional information to organize embryonic tissues. Unearthing embryology-like processes in tumors may allow us to control organ-like tumor features such as tissue repair and revascularization and treat intratumoral heterogeneity.

Tumors display a large degree of genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity that hampers diagnosis and treatment (1–8). However, tumors are capable of local organization and respond collectively to signals from their microenvironment (9, 10). Examples include the formation of multicellular structures such as blood vessels (11, 12), coordinated collective invasion (13), noncell autonomous paracrine effects (14), and “division of labor” between different tumor cells (15). How can multicellular organization emerge within heterogeneous and genetically diverse tumors?

Here we reveal that gradients of metabolites, formed by the altered metabolism of cancer cells (16–18) and accentuated by aberrant vascularization (11, 19–21), lead to predictable phenotypic diversity in the tumor microenvironment. This drives temporal and spatial coordination of multiple cell types, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) that are known to respond to extracellular metabolite levels (21–24). We propose that the topology of the vasculature leads to local differences in metabolite concentrations that provide spatial information that can modulate the phenotypes of different cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Results

Extracellular Metabolites Form Gradients That Convey Positional Information in Tumors.

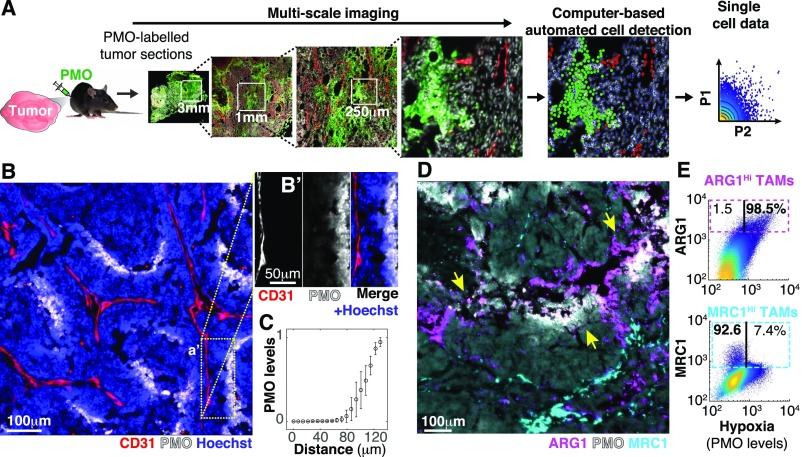

To measure intratumoral cellular heterogeneity, while preserving information regarding tissue microarchitecture, we developed an image cytometry approach that combines multiscale microscopy and image processing to extract single-cell data, including spatial features such as distance to the vasculature, for thousands of cells in tumor tissue cryosections (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1 A–D). In a mouse model of breast tumor [mouse mammary tumor virus–polyoma virus middle T-antigen (MMTV-PyMT)] we found that gradients of hypoxia [labeled with pimonidazole (PMO)] closely mirrored the topology of the vasculature and, consistent with previous reports (12, 19–21), saturated at ∼100 μm from the closest blood vessel (Fig. 1 B and C).

Fig. 1.

Spatial diversity in TAM phenotypes correlates with metabolic gradients within tumors. (A) Experimental approach to study metabolic and cellular intratumoral heterogeneity. PMO (a hypoxia marker) was injected into tumor-bearing mice to label hypoxic tumor regions. Tumor cryosections were then imaged at high magnification (typically at 200×), achieving multiscale images. This enabled image processing to obtain single-cell features for hundreds of thousands of cells per section while maintaining their spatial information. (B and C) The spatial distribution of hypoxia mirrored the structure of the tumor vasculature from a distance. (B) Cryosections of MMTV-PyMT tumors were stained with antibodies against endothelial vascular cells (CD31) and hypoxic regions (PMO). (B′) Image channels were split in a selected field of interest to reveal the correlation between hypoxia and distance from the vessel. This was quantified in C (bars indicate SD, n = 6). (D and E) Phenotypic diversity of TAMs correlates with the topology of the vascular system. (D) Similar tissue sections were stained with antibodies against TAM markers (MRC1 and ARG1) and PMO (colocalization of ARG1 and PMO indicated by yellow arrows). (E) Image quantification of individual cells within tumor sections showed that ARG1 levels in TAMs were correlated with hypoxic regions (r = 0.6, ) whereas MRC1-expressing TAMs were inversely correlated with local hypoxic levels (r = -0.2, ). Three sections of three tumors extracted from different animals were analyzed for each marker.

Fig. S1.

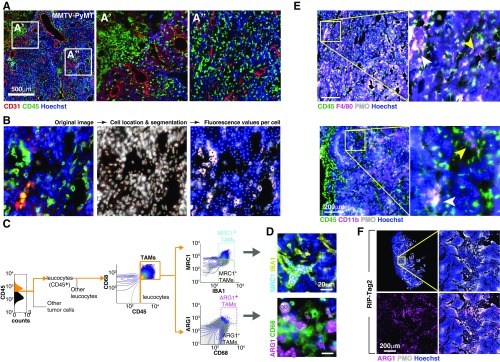

Image-based analysis of cellular diversity in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Tumor cryosection (MMTV-PyMT, breast) showing the diversity in the distribution of white blood cells with respect to different tumor regions. (B) By imaging an array of adjacent fields at high magnification (200×) we achieved multiscale images where we could measure individual cell features for hundreds of thousands of cells per section. Here we show an example of the image analysis procedure. More details are in SI Materials and Methods. (C) Image analysis-based gating algorithm used to digitally isolate MRC1HI and ARG1HI TAM subpopulations. (D) Representative images showing MRC1HI (Upper) and ARG1HI (Lower) TAMs. Cyan and magenta circles are located where the computer detected MRC1HI and ARG1HI TAMs, respectively. (E) TAM markers such as CD11b F4/80 were widely distributed and could be found in hypoxic (white arrowhead) and nonhypoxic (yellow arrowhead) tumor regions. (F) Spatial patterns of ARG1 expression correlated with local hypoxia in a pancreatic tumor model (RIP-Tag2). Images in A, B, and D–F are composites of multiple adjacent pictures.

We asked whether these gradients of metabolites could impose patterned phenotypic changes in cells experiencing different local conditions. We focused on TAMs, a major protumoral stromal infiltrate (25–27) whose phenotypic state and viability can be altered by metabolic stimuli (21–23). We measured levels of selected markers associated with different TAM states and investigated their relationship to local hypoxia levels and distance to the nearest vessel. Whereas some macrophage markers were expressed homogenously (Fig. S1E), the TAM markers arginase 1 (ARG1) and mannose receptor, C type 1 (MRC1) were expressed in distinct and spatially restricted subpopulations (Fig. 1D). TAMs located in well-nourished regions, such as cortical and perivascular areas, expressed MRC1 whereas macrophages within hypoxic regions, far from the vasculature, showed high ARG1 protein levels (Fig. 1 D and E).The spatial segregation between ARG1HI and MRC1HI TAMs was somewhat surprising because these markers are often coexpressed by antiinflammatory macrophages that respond to type 2 helper T-cell (Th2) signals and have been proposed to share features with TAMs (26–29). We confirmed the correlation between hypoxia and the location of ARG1HI TAMs in a mouse model of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [rat insulin promoter 1–T-antigen (RIP1-TAg2)] (Fig. S1F), indicating that spatial patterning of TAM phenotypes is a common feature of the tumor microenvironment.

Gradients of Oxygen and Lactate Orchestrate Spatial Patterns of Cell Phenotypes.

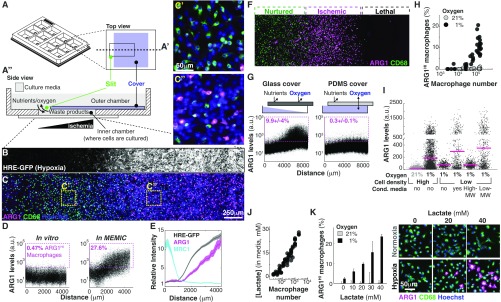

Our in vivo observations suggest a model where extracellular metabolites specify different TAM subpopulations across concentration gradients, similar to how morphogen gradients specify stripes of gene expression during embryonic development (30–32). We then sought to investigate whether metabolite gradients were sufficient to produce gene expression patterns in TAMs. Traditional in vitro systems are spatially homogeneous without major changes in metabolite distribution. To overcome this, we developed an in vitro microphysiological system named the metabolic microenvironment chamber (MEMIC) (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2 A and B). MEMIC allows gradients of ischemia to emerge spontaneously as a result of cellular activities such as nutrient consumption and secretion of waste products. As a proof of principle, we used MEMIC to generate and visualize oxygen gradients in the hypoxic response of C6 glioma cells engineered to express GFP under an HIF1-responsive element (C6-GFP-HRE) (21) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

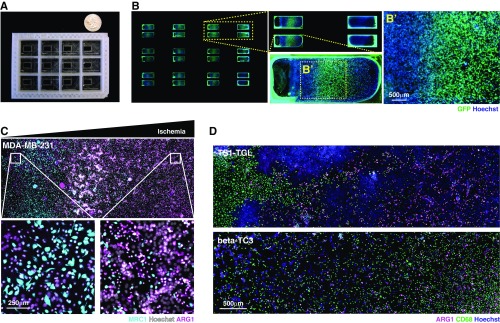

Extracellular metabolic gradients are necessary and sufficient to produce striped expression domains and spatial patterning of macrophages. (A) Schematic representation of the MEMIC chamber fabricated with 3D printing. This 12-well format contains an independent MEMIC replicate in each well. (A′) Top view of one of those wells. (A′′) Detailed side view of a MEMIC where cells are cultured in a small chamber that connects to a large volume of fresh media through a slit. Cell activities such as nutrient consumption and waste product secretion change the local nutrient composition within the small chamber and generate spatial gradients; diffusion via the slit allows a constant exchange with the fresh media reservoir. Thus, cells proximal to this slit remain well nurtured, whereas distal cells become progressively more ischemic. (B and C) Coculture of macrophages and a cancer cell line engineered to express GFP under hypoxia (C6-HRE-GFP). (B) GFP hypoxia at 24 h reveals a spatial gradient. (C) In the same culture, spatial patterns of ARG1 in macrophages mirrored hypoxia gradients (compare Insets C′ and C′′). (D) Image analysis at the single-cell level of macrophages cocultured with C6-HRE-GFP glioma cells in a conventional in vitro system (without metabolite gradients, Left) or in the MEMIC (Right). ARG1HI macrophages are defined as expressing levels fivefold higher than the median. (E) ARG1 levels increased with hypoxia whereas MRC1 levels decreased with hypoxia. (F–H) Hypoxia was necessary but not sufficient to trigger ARG1 expression. (F) Cancer cells were not required for the emergence of phenotypic patterns as macrophages cultured in the MEMIC alone displayed stripes of ARG1 expression in sublethal levels of ischemia. (G) Spatial patterns of ARG1 expression in macrophage monocultures (Left). This effect required hypoxia as it disappeared when concentration was restored to environmental levels using a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane (Right) that is permeable to gases. (H) Hypoxia can induce the expression of ARG1 but only in high-density cultures, showing that it is necessary but not sufficient. (I) Low molecular weight fraction of conditioned media collected from macrophages cultured under hypoxia can trigger ARG1 expression in sparse macrophage cultures. Conditioned media were fractioned according to molecular weight (MW) with a 3-kDa cutoff. Note change of scale in y axis. (J) Lactate, which accumulated in the cell culture media of hypoxic macrophages, increases with macrophage density (24 h culture at 1% ). (K) Lactate showed a dose-dependent synergy in inducing ARG1 levels with low . Lactate doses were chosen to cover the range between no lactate and high lactate doses typically used to study cellular response to this molecule (21, 22, 48). Bars indicate SD from three biological replicates. Images are representative of selected lactate doses.

Fig. S2.

Design of the MEMIC and effect of metabolites in the patterning of macrophages. (A) Photograph of the MEMIC. A quarter of a US dollar was placed as a scale bar. (B) Multiscale imaging of the entire MEMIC, zooming into one of the chambers. (C) Reverse spatial patterns of ARG1 and MRC1 expression in macrophages cocultured with human breast tumor cells (MDA-MB-231). (D) Spatial patterns of ARG1 expression emerged in macrophages, regardless of which cancer line they were cocultured with, including cells derived from our murine tumor models, TS1-TGL (from MMTV-PyMT) and -TC3 (from RIP-Tag2). Images in B–D are composites of multiple adjacent pictures.

To assess whether gradients of metabolites can pattern macrophages in the MEMIC, we cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages (hereafter referred to simply as macrophages) (SI Materials and Methods) with C6-GFP-HRE cells. After 24 h, macrophages showed spatial patterns of ARG1 protein levels that correlated with GFP (hypoxia) and increased with the distance to the normoxic region (Fig. 2 C and D). In control experiments lacking metabolite gradients, we did not observe induction of ARG1 expression (Fig. 2D). Consistent with our in vivo observations, MRC1 protein levels were inversely correlated with hypoxia and were higher in normoxic regions (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2C). These spontaneous expression patterns were not dependent on the cancer cell type as MEMIC experiments with macrophages cocultured with cell lines derived from the PyMT and Rip-Tag2 tumor models used above, human cancer cell lines (Fig. S2 C and D), or even macrophages cultured alone (Fig. 2F) showed the same trend. We have recently shown that extreme levels of ischemia are lethal for macrophages (21). Consistently, ARG1 expression emerges as a stripe between well-nurtured macrophages and the region where ischemic levels become lethal (Fig. 2F). Together, these results demonstrate that MEMIC experiments suggest that extracellular metabolite gradients play a key role in the phenotypic diversity of TAMs.

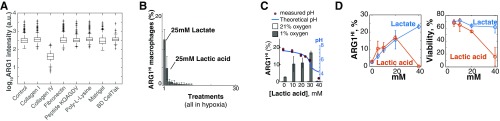

Gradual changes in metabolite concentration are somehow translated into discrete stripes of gene expression patterns with clear boundaries (Fig. 2F and Fig. S2C). To identify which metabolites are setting these phenotypic boundaries, we focused on the ischemic ARG1HI/MRC1LO macrophage subpopulation. First, we wanted to separate the effect of hypoxia from other ischemic conditions such as nutrient deprivation. To do this, we cultured macrophages within a modified MEMIC where the top cover was made permeable to oxygen but not to soluble metabolites. In this scenario, ARG1 protein levels remained low across the entire MEMIC, showing that hypoxia is necessary to produce ARG1 patterns (Fig. 2G). To test whether hypoxia was sufficient to induce ARG1, we cultured macrophages in regular culture plates within a hypoxic chamber (1% oxygen) or under normal cell culture conditions (21% oxygen). Surprisingly, we found no effect of hypoxia in ARG1 levels, unless macrophages were cultured at high cell densities (Fig. 2H), indicating that hypoxia was necessary but not sufficient to pattern macrophages. This cell density effect was not mediated by cell–cell contact because stimulation of cell contact-sensing molecules (33) did not increase ARG1 levels (Fig. S3A).

Fig. S3.

A combination of oxygen and lactate was necessary and sufficient to trigger striped patterns of ARG1 expression. (A) Cell culture plates were coated with the molecules shown in the x axis and then macrophages were seeded and cultured in hypoxia for 24 h. The combination of hypoxia and stimulation of cell adhesion molecules that could mediate the sensing of cell density did not increase ARG1 levels in sparse macrophage cultures relative to control. (B) Macrophages were cultured in hypoxia for 24 h in DMEM, supplemented with (or lacking) nutrients according to Table S1. Lactate and lactic acid produced a significant increase in ARG1 levels in sparse macrophage cultures. (C) Lactic acid had the same effect on hypoxic macrophages as lactate. However, at high concentrations (30 mM) the effect of lactic acid disappeared. This coincided with the point at which the buffering capacity of the media is predicted to be broken. (D) We have published that at high lactic acid concentrations (low pH; ref. 21), macrophages lose their viability. Consistently, high concentrations of lactic acid did not trigger ARG1 expression but lead to macrophage death. In B–D, error bars correspond to SD from three biological replicates.

Consistent with previous evidence (22), we found extensive evidence for the synergistic role of hypoxia and lactate. First, the treatment of sparse macrophage populations with a combination of hypoxia and culture media previously conditioned by dense macrophage populations (cultured under hypoxia) increased ARG1 levels (Fig. 2I). To determine the molecular weight of the secreted signal, we fractionated the conditioned media (3-kDa cutoff columns). This revealed that the low, but not the high, molecular weight fraction of the conditioned media increased ARG1 levels in sparse macrophage cultures, indicating that the sensed factor was a small molecule (Fig. 2I). We therefore screened for different small molecules that could synergize with hypoxia to increase ARG1 levels (Table S1). We found that the most potent inducer was lactate (Fig. S3B). Hypoxic macrophages secreted lactate, which accumulated in the cell culture media proportionally to the density of macrophages (Fig. 2J). When we treated normoxic and hypoxic macrophages with a wide range of lactate doses, we saw a concomitant increase of ARG1 protein levels in hypoxic macrophages but not in normoxic ones, showing that lactate and hypoxia act as synergistic cues to induce ARG1 expression (Fig. 2K). This effect is consistent with recent evidence showing a similar effect of lactate in transcription levels of Arg1 mRNA in TAMs (22). However, in our experiments, lactate alone was not sufficient to trigger a maximal Arg1 response at the protein level (Fig. 2K).

Table S1.

Metabolites used to condition growth media

| Rank | Molecule | Concentration | Relevance |

| 1 | NaLactate | 20 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 2 | Lactic acid | 20 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 3 | Glutamate | 3 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 4 | Malate | 1 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 5 | Low glutamine | 0.2 mM | 1:10 diminished glutamine supplementation |

| 6 | Pyruvate | 20 mM | Substrate for lactate production by LDHA |

| 7 | Na oxamate | 10 m | LDHA inhibitor |

| 8 | Phosphocholine | 1 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 9 | Control media | NA | Control media (DMEM) |

| 10 | Low glucose | 2.5 mM | 1:10 diminished glucose supplementation |

| 11 | 1/10 media | Diluted in PBS | 10% of full media |

| 12 | 1/10 media + lactate | Diluted in PBS + 20 mM (Lac) | 10% of full media + 20 mM Lactate |

| 13 | Low FBS | 1% | 1:10 diminished FBS supplementation |

| 14 | Oxamate + lactate | 10 mM (Oxa) + 20 mM (Lac) | Interference with LDHA function |

| 15 | KG | 10 mM | Substrate for 2-HG generation by LDHA in hypoxia (62) |

| 16 | 2-HG | 10 mM | Secreted by hypoxic cells (62) |

| 17 | KG + 2-HG | 10 mM | Substrate and products for LDHA in hypoxia (62) |

| 18 | Alanine | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 19 | Citrate | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 20 | Glycerol | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 21 | Fumarate | 10 mM | Part of the urea cycle (where ARG1 has its catalytic activity) |

| 22 | Putrescine | 10 mM | Part of the urea cycle (where ARG1 has its catalytic activity) |

| 23 | Spermine | 10 mM | Part of the urea cycle (where ARG1 has its catalytic activity) |

| 24 | Spermidine | 10 mM | Part of the urea cycle (where ARG1 has its catalytic activity) |

| 25 | Succinate | 10 mM | Related to ischemic response in macrophages (63) |

| 26 | Ammonia | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 27 | Ammonia + glutamate | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 28 | Proline | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) |

| 29 | HCl | 10 mM | Acidic pH |

| 30 | Urea | 10 mM | Secreted by most cells in culture (61) and part of the urea cycle |

Lactic acid had similar effects to those of lactate but at high concentrations it also affected macrophage viability due to media acidification (21) (Fig. S3 C–E). Overall, our results showed that a combination of low oxygen and high lactate was necessary and sufficient to trigger the expression of ARG1 in macrophages. These data suggest that opposing gradients of lactate and oxygen, which are ubiquitous in solid tumors (19–21), create predictable phenotypic patterns among TAMs. Because these gradients follow the topology of the tumor vascular system (Fig. 1), it is possible that they convey positional information about the distance to blood vessels.

Positional Information Is Interpreted via MAPK/ERK Signaling.

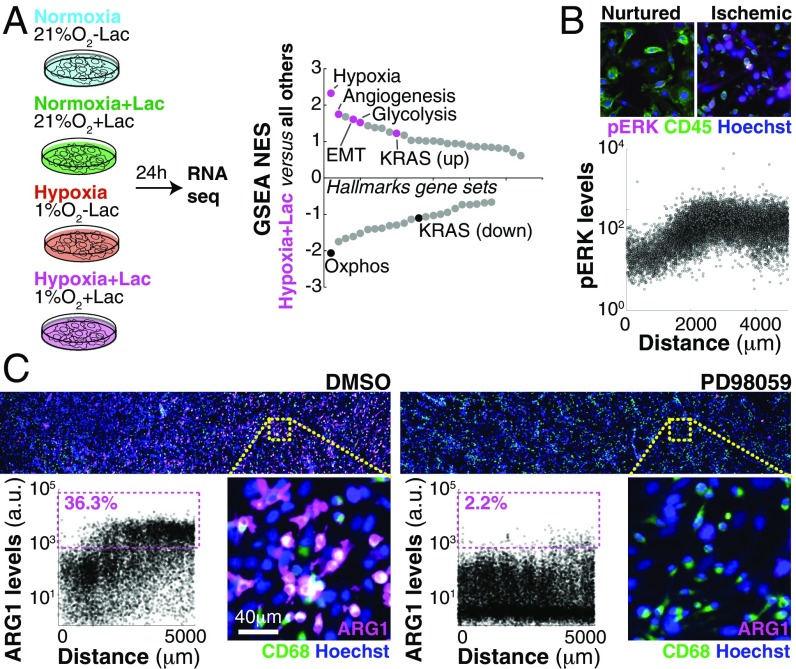

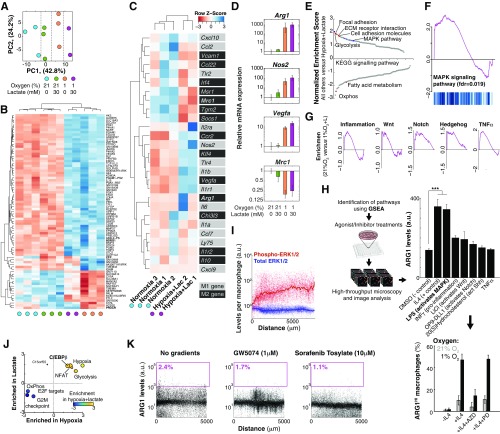

We then investigated how macrophages sensed the combination of low oxygen and high lactate and integrated those signals into phenotypic responses. We used RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to identify transcriptional differences between macrophages treated with different levels of oxygen and/or high lactate (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3 A–C). We first observed that transcriptional changes in macrophages treated by oxygen/lactate did not display a consistent change in gene expression of markers commonly used to characterize macrophages as pro- or antiinflammatory (26–29) in a consistent manner (Fig. S4C). The effect of metabolites, however, did induce features of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-induced macrophage response to LPS that signals via the MAPK pathway (Fig. S4 C and D), such as Arg1 and Nos2 coexpression (34). Reinforcing this observation, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNA-seq data revealed that macrophages cultured in low oxygen and high lactate showed an enriched signature of KRAS/MAPK signaling activation (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4F). Pharmacological perturbations further supported a role for the MAPK pathway by showing that LPS increased ARG1 levels in hypoxic macrophages specifically through this pathway (Fig. S4 E–H).

Fig. 3.

Macrophages respond to gradients of extracellular metabolites, using MAPK signaling. (A) RNA-seq revealed transcriptional changes of macrophages cultured under different levels of metabolites. GSEA suggested a strong enrichment of the KRAS/MAPK pathway. (B) KRAS signals via the MAPK pathway and macrophages cultured in the MEMIC showed spatial patterns of MAPK activation (ERK1/2 phosphorylation) correlated with ischemia. (C) Representative images and single-cell–level quantification showing that MAPK inhibition abrogates macrophage spatial patterns in the MEMIC.

Fig. S4.

Oxygen and lactate trigger a genome-wide response driven by MAPK. (A–C) Transcriptional response of macrophages treated with different levels of lactate and/or oxygen. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-seq data showed that different treatments are the main source of variability in gene expression. (B) Supervised hierarchical clustering of significantly changed genes. (C) Levels of genes typically used to distinguish M1 from M2 macrophages. Note that M1/M2 genes did not cluster well with the metabolic treatments. (D) Validation of RNA-seq data for selected markers from C, using qPCR. (E) Normalized enrichment scores of GSEA analysis. (F) GSEA plot showing enrichment for MAPK. (G) GSEA plots showing enrichment for other pathways significantly enriched by lactate and hypoxia treatment. (H) Pharmacological screening. Hypoxic macrophages were treated with chemical agonists for the pathways shown in G. IL4 treatment was used as a positive control. LPS treatment significantly increased ARG1 levels in hypoxic macrophages (P 0.001) and this effect was inhibited by the MEK inhibitor PD98059, showing that its effect is via MAPK. IL4 signals via the Jak/Stat pathway as its effect was inhibited by AZD1480 (AZD) but not by PD98059 (PD). Error bars correspond to SD from three biological replicates. (I) Image analysis showing constant levels of total ERK1/2 but increasing levels of phospho-ERK1/2 in the MEMIC. (J) Quantification of hypoxia and lactate synergy. x axis, effect of hypoxia; y axis, effect of lactate; z axis (color), effect of both. (K) c-Raf antagonists GW5074 and the FDA-approved Sorafenib Tosylate inhibited the patterned expression of ARG1, showing that lactate and oxygen are integrated upstream of c-Raf.

If the MAPK pathway is interpreting positional information brought by oxygen and lactate gradients, it should (i) be activated in a gradual manner and (ii) be required for the phenotypic switch we observed in macrophages (35, 36). First, we observed a strong correlation between phospho-ERK1/2 levels and the distance from the normoxic region (Fig. 3B) whereas total MAPK (ERK1/2) levels remained constant (Fig. S4I). Inhibition of MEK, a key member of this pathway, completely abrogated ARG1 patterning (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained by inhibiting the upstream MAPK component c-Raf with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved inhibitor Sorafenib as well as with the more selective GW5074 (Fig. S4K). Altogether our data show that, by sensing lactate and oxygen levels, TAMs can determine their position with respect to the vasculature (or to the slit in the MEMIC). This positional information required MAPK signaling and led to a predictable emergence of spatial phenotypic diversity in macrophages.

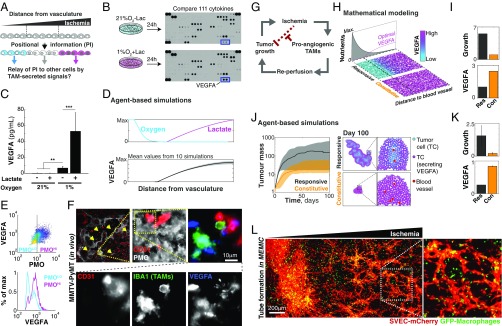

Macrophages Relay Positional Information and Organize Morphogenetic Changes in Neighboring Cells.

During embryogenesis, patterned cells can elaborate and refine developmental programs by relaying their positional information via the secretion of cell signals that are sensed by adjacent cells (30–32). We thus hypothesized that macrophages, conditioned by metabolic cues, can relay their positional information to neighboring cells (Fig. 4A). We thus compared cytokine secretion profiles of macrophages treated with hypoxia and/or high levels of lactate. The combination of hypoxia and lactate increased secretion of the proangiogenic cytokine VEGFA above all other 111 screened cytokines (Fig. 4B). Quantification of secreted VEGFA, using a bead-based ELISA (Fig. 4C), and of Vegfa mRNA levels, using quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. S4D), showed that hypoxia increased VEGFA secretion and that this effect was boosted by lactate, indicating that hypoxia and lactate regulate macrophage cytokine production in a synergistic manner (Fig. S4J).

Fig. 4.

Macrophages relay their positional information to endothelial cells and orchestrate efficient tube morphogenesis. (A) Our data suggest that, in a process resembling embryological organization, gradients of extracellular metabolites convey positional information that modifies TAM phenotypes. We asked whether additional signaling molecules, secreted by patterned macrophages, could relay positional information to other tumor cells. (B) Screening of 111 secreted chemokines revealed that ischemic macrophages express VEGFA. (C) Quantification of secreted chemokines confirmed this finding and the synergy between lactate and hypoxia (bars indicate SD from six biological replicates; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (D) Mathematical modeling predicted spatial patterns of VEGFA levels. (E) Quantification in a representative PyMT-MMTV tumor section showing that ischemic TAMs express higher VEGFA levels. (F) Images showing small groups of endothelial cells in hypoxic regions (yellow arrows). One of these regions was magnified to show that these endothelial cells are adjacent to VEGFA-expressing TAMs. For clarity, F, Lower shows isolated channels. (G) Our data suggest that whereas tumor growth leads to ischemic regions, the response of the stroma is to revascularize these regions, thus allowing tumor growth to resume. (H and I) Analytical solution of our theoretical model showed that a proangiogenic strategy that responds to ischemia (Res, responsive) led to faster-growing and larger tumors than homogeneous (Con, constitutive) angiogenesis. (H) Spatial patterns of predicted levels of VEGFA secretion for responsive and constitutive strategies. (I) Growth rates and cost of secreting VEGFA for the two strategies. (J and K) Simulation results from an agent-based model. (J) Growth curves of tumors using different proangiogenic strategies confirmed that the responsive strategy leads to enhanced tumor growth compared with the constitutive strategy. J, Right shows representative images of model outcomes. The responsive strategy not only allowed for faster tumor growth, but also required less total VEGFA. (K) Bars indicate SD from 10 simulations. (L) Localized tube morphogenesis emerges within the MEMIC from a triple coculture of macrophages, endothelial cells (SVECs), and tumor cells (TS1, unlabeled). L, Inset shows a representative magnified region.

To test whether these changes were functionally relevant, we cocultured GFP-expressing macrophages with mCherry-labeled SVEC4-10 endothelial (SVEC) cells embedded in a matrigel/collagen I matrix layer (Fig. S5B). Under normal conditions, these cocultures did not result in any evidence of vasculogenesis. In contrast, macrophages previously cultured under low oxygen and high lactate levels were able to induce tube-like morphogenesis in SVEC cells (Fig. S5B and Movie S1). Control experiments using hypoxia and lactate in the absence of macrophages or in the presence of macrophages treated with MAPK or VEGF inhibitors showed no vascular morphogenesis, indicating that VEGFA, secreted by ischemic macrophages, was required for the response of endothelial cells (Fig. S5C). These data show that macrophages were able to relay information about microenvironmental conditions to endothelial cells and to trigger a modular and noncell autonomous process of tube-like morphogenesis in response to oxygen and lactate levels.

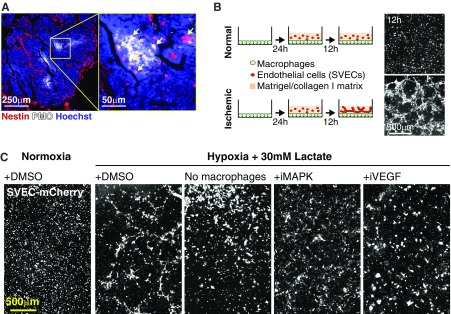

Fig. S5.

Spatial vascular morphogenesis induced by ischemic macrophages leads to an optimal angiogenic strategy. (A) Endothelial cells within ischemic regions in tumors express the nascent vessel marker Nestin. (B) Tube formation in vitro. Macrophages were cultured in vitro under normal (Upper) or ischemic (Lower) (1% oxygen and 30 mM lactate) conditions for 24 h. Then, endothelial cells (SVECs) embedded in a protein matrix (collagen/matrigel) were added. After 12 h, SVEC cells formed tube-like structures but only under low-oxygen/high-lactate conditions. (C) This tube morphogenesis did not occur in normoxia or in the absence of macrophages and was inhibited by PD98059 (iMAPK) or +Linifanib (iVEGF). Images in A and C are composites of multiple adjacent pictures.

Positional Information Optimizes Angiogenesis and Leads to Faster-Growing Tumors.

Lactate and hypoxia increase with the distance from the vasculature, suggesting that VEGFA levels should also increase within ischemic regions. Using an agent-based model that we developed to study this type of question (21), we predicted that VEGFA levels should indeed increase in ischemic regions (Fig. 4D). Consistent with this, analysis of tumor sections in the MMTV-PyMT model revealed that hypoxic TAMs expressed higher VEGFA levels than TAMs located in other tumor regions (Fig. 4E). We also observed that within hypoxic tumor regions, VEGFA-expressing TAMs were associated with small groups of CD31+ endothelial cells that have not yet formed into vessels (Fig. 4F). These endothelial cells stained positive for the nascent capillary marker nestin (NES) (Fig. S5A). A similar scenario has been reported during nerve regeneration where hypoxia triggers VEGFA secretion by resident macrophages that then recruit endothelial cells required for revascularization and repair (23, 37). Our data suggest that ischemic TAM subpopulations secrete VEGFA to induce endothelial cells to initiate the revascularization of nutrient-deprived tumor regions, which in turn would promote tumor growth (Fig. 4G). In fact, the metabolism of TAMs has been recently shown to control tumor blood vessel morphogenesis and metastasis (24).

Is there any advantage for the tumor to maintain a spatially regulated vascularization mechanism? How does it compare, for example, to constitutive secretion of VEGFA that would promote angiogenesis throughout the tumor? With the help of mathematical modeling, we first simulated the growth of tumors with a responsive angiogenic strategy, where the secretion of proangiogenic factors (e.g., VEGFA) is modulated by extracellular metabolites, which we compared with simulated tumors that used a constitutive proangiogenic strategy. We assumed that (i) the benefits of vascularization (i.e., nutrients, oxygen) have diminishing returns on cell growth (i.e., excessive nutrients no longer increase cell growth rate) and (ii) the formation of new vessels is a costly process. We implemented this as an explicit cost, but it can also result from the increasing resistance to flow in a dense vascular network (38). The analytical solution to this model revealed that the responsive strategy always led to faster tumor growth rates even though the total levels of VEGFA were higher in the constitutive model (Fig. 4 H and I and Fig. S6A). More detailed agent-based models confirmed these conclusions (Fig. S6 B–E, Movie S2, and Fig. 4 J and K; model details in Supporting Information, Mathematical Modeling). This result highlights that the spatial distribution of signals can be more relevant for the progression of the disease than its total levels, which could explain conflicting outcomes in anti-VEGFA therapies (12, 39). Our model also shows that tumors, by engaging with infiltrated macrophages, can activate a mechanism of revascularization that allows the delivery of nutrients where they are most needed without wasting resources in well-perfused tumor regions.

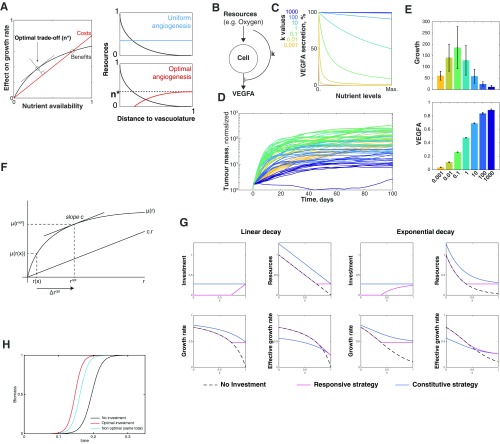

Fig. S6.

Spatial vascular morphogenesis induced by ischemic macrophages leads to an optimal angiogenic strategy. (A) Analytic solution to our theoretical model. The effects of nutrients in cell growth have diminishing returns. We assumed that increasing the access to these nutrients (the process of angiogenesis) has a linear cost that creates a trade-off between benefit and cost. We showed that growth is optimized when cells try to get more nutrients only if they are exposed to low levels of nutrients (n* or less). n* is defined by the slope of the cost. More details are in Mathematical Modeling. (B–D) Numerical simulations implemented in an agent-based modeling framework (59, 60). (B) Schematic representation of the model. Resources allow for tumor growth but also inhibited secretion of proangiogenic molecules. The strength of this inhibition is dictated by . (C) Secretion of proangiogenic molecules (e.g., VEGFA) according to different nutrient levels for different values of k. At high k values cells secrete VEGFA constitutively. (D) Growth curves of tumors with different k. Each line represents the temporal trajectory of an individual tumor and is colored according its k value. We did 10 simulations with different random seeds for each k value. (E) Bars in Upper plot show that there is an optimal level of response to nutrients that leads to greater tumor growth. If k is too high, tumors secrete VEGFA in a constitutive manner that leads to an increase in total VEGFA levels (E, Lower) but a decrease in growth rate. On the other extreme, if k values are too low, there is not enough VEGFA to sustain rapid tumor growth. The two strategies shown in main text Fig. 4 correspond to k of 0.1 (for the responsive strategy) and 100 (for the constitutive strategy). Error bars correspond to SD from 10 simulations. More details are in Mathematical Modeling. (F) Optimal investment under growth with diminishing returns. The growth rate is a function of the resource density and exhibits diminishing returns. Profit is maximized when . (G) Responsive investment is a better strategy than constitutive investment. In G, Left we consider a linear resource decay from the left side, as described in the text. G, Right displays similar results from an exponential distribution of resources. In both cases, the model is implemented the same way. (Upper Left) The constitutive strategy consists of investing everywhere the same amount (blue line). The responsive strategy localizes investment only where resources are limited (red line). (Upper Right) Level of resources after investment. The dashed black line represents the spatial distribution of resources without investment. (Lower Left) Growth rate given by the saturation kinetics. Because the constitutive strategy invests everywhere, its growth rate is greater as well. (Lower Right) When cost of investment is included in the effective growth rate, then the responsive strategy appears to be better than the constitutive strategy. In the two cases, and . (H) Logistic growth using the three strategies described above.

Our data and mathematical models suggest that proangiogenic conditions are restricted to ischemic regions, which would lead to local and responsive angiogenic strategies. To test this, we took advantage of the MEMIC system to generate regions of hypoxia in a triple coculture of PyMT-derived tumor cells, macrophages, and SVEC endothelial cells. After 3 d of culture, SVEC cells formed well-structured tubes but only within ischemic regions of the MEMIC (Fig. 4L). These data indicate that macrophages indeed orchestrate tube-like morphogenesis in regions where revascularization is most needed. More broadly, this suggests that macrophages conditioned by metabolic gradients can relay spatial information to neighboring cells, triggering functional adaptations to their local environment.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophage Extraction.

C6-HRE-GFP (49) cells were kindly provided by Inna Serganova, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York. MDA-MB-231 and SVEC-4-10 cells were purchased from ATCC. All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma and authenticated using MSKCC core facilities. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and a combination of antibiotic and antimycotic (Gibco 15240). For the extraction of bone-marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), standard protocols were used that ensure a virtually 100% pure population of CD68+/IBA1-positive cells (50). Briefly, femurs and tibiae from C57BL/6 mice were harvested under sterile conditions from both legs and flushed using a 25-gauge needle. The marrow was passed through a 40-μm strainer and cultured in 30-mL Teflon bags (PermaLife) with 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse CSF-1 (R&D Systems). Bone marrow cells were cultured in Teflon bags for 7 d, with fresh CSF-1–containing medium replacing old medium every other day to induce macrophage differentiation.

Typical cell culture conditions [37 C, 5% CO2, and environmental (21%) oxygen] were normally used and were the conditions referred to as normoxia. Hypoxia was generated with an Oxygen/CO2 controller (Proox C21; BioSpherix) connected to a sealed chamber (C-Chamber; BioSpherix). Normally it was set at 1% oxygen and 5% . Lower oxygen levels (0.1–0.5%) were also tested but showed no significant difference with 1%. Lactate (Sigma; L7022) or lactic acid (Sigma; 46937 or 27715) was freshly prepared before adding to the culture media. In our screen we used lactate levels that are often achieved when cells are cultured in vitro (Fig. 2J). Typically we observe a 1:1 glucose to lactate conversion, which means that when using DMEM HG with 25 mM glucose, we can expect 25 mM of lactate in the spent media, which is consistent with levels secreted by hypoxic macrophages (Fig. 2J).

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence was performed by fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min followed by permeabilization in 0.1% tween or methanol. Then, cells were washed with PBS after which they were blocked for 1 h in 2.5% BSA (in PBS). After blocking, cells were incubated overnight with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. We used antibodies against ARG1 (GeneTex; GTX109242 for cell culture), ARG1 (Novus; NB100-59740 for tumor sections), CD68 (Serotec; MCA1957), CD11B (BD; 550282), F4/80 (Serotec; 0803), MRC1 (Serotec; MCA2235), GFP (Invitrogen; A10262), CD31 (BD; 550274), PMO (Hpi; MAb1), IBA1 (Wako; LAH0501), ERK (CST; 4695), phospho-ERK (CST; 4370), VEGFA (Abcam; ab46154), CD45 (R&D; AF114), and Nestin (Biolegend; 839801). After washing the primary antibody with PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (AlexaFluor 488 or 594 or 647; Molecular Probes) diluted 1:500 in blocking solution for 1 h. For nuclear counterstaining, Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes; H3570 at 1 g/mL) was added to the same secondary solution. After washing with PBS, cells were stored in the dark and imaged within 1 d or 2 d.

Microscopy.

We used an AxioObserver.Z1 epifluorescence inverted microscope with a motorized stage and environmental (CO2, humidity, and temperature) control. A CCD camera allowed digital image acquisition (Hammamatsu; Orca II). For multiwell and multidimensional microscopy a definite focus was used and the microscope was programed to image consecutive image fields (typically 60 per condition). These fields were stitched together using the built-in Axiovision function and exported as raw 16-bit TIFF files without further processing. We typically imaged at least 10,000 cells per well at 200× magnification.

Preparation of Tumor Samples.

PMO (Hydroxyprobe) was injected intraperitoneally (60 mg/kg mouse body weight, i.e., 1.5 mg per mouse) diluted into PBS at 2 mg/mL. After 1 h, mice were killed and processed further. For preparation of PyMT-MMTV and RIP-Tag tumor sections, mammary or pancreatic tissues were prepared as previously described (51) for frozen embedding. Using a cryostat (Zeiss), 10-μm-thick frozen tumor sections were obtained and affixed to glass slides. Slides were stored at −20 C until staining. The same immunofluorescent and imaging methods were used as for in vitro cultures.

Image Analysis.

Image analysis essentially required three steps: cell detection, nuclear segmentation, and fluorescence detection in a per cell basis. These steps were implemented on custom-made Matlab (MathWorks) scripts. First, cells were detected by adapting a Matlab implementation of the IDL particle tracking code developed by David Grier, John Crocker, and Eric Weeks (physics.georgetown.edu/matlab/). This algorithm finds cells as peaks in a Fourier space rather than by thresholding. This is a much more robust approach and it is almost insensitive to problems that typically arise when segmenting large images such as autofluorescent and bright speckles or day-to-day variability in imaging conditions. Cell detection allowed us to count, identify, and get the spatial coordinates (centroid) for each cell. Second, nuclear or cytoplasmic segmentation was achieved by a combination of regular thresholding of a nuclear or cytoplasmic marker together with a watershed process based on the distance of cell centroids determined in the previous step. Obtained regions were then used as masks to quantify pixel intensities for all of the fluorescent channels (that reported levels of different proteins) on a per cell basis. We used cumulative values, which were then normalized to the nuclear staining (e.g., Hoechst or DAPI) or to a cytoplasmic marker (e.g., a macrophage marker such as CD68). After image analysis, data were processed and plotted also with Matlab. Raw data, image analysis, and data processing routines are available upon request.

Fabrication of MEMIC.

The main structure of the MEMIC was fabricated in house with an Ultimaker2 3D printer (Ultimaker BV), using polylactide (PLA), a biodegradable thermoplastic aliphatic polyester. This structure comprised the multiwells with the little chambers for individual MEMICs. The MEMIC was designed to have the same size as microtiter plates, which allowed it to be mounted on conventional microscope stages. It also allowed us to use commercial lids for our MEMIC. The bottom glass coverslip (FisherBrand; 12-541A) and the top membrane (made of glass or PDMS) were glued with a small amount of NOA81 (Norland Optical Adhesive), a biocompatible and oxygen-impermeable (52) UV-curable glue. This top membrane was offset about 300 m in one side from the border of the MEMIC to create a slit (main text Fig. 2). Thus, the internal chamber is the small volume confined between the two glass surfaces. In experiments using PDMS membranes [a glass-permeable polymer (53)] the procedure was similar but the top coverslip was replaced by an 1-mm-thick layer of PDMS (prepared fresh Sylgard 184; Dow Corning). To curate the NOA81 and secure the glass or PDMS cover, we exposed the dish to the UV for about 20 s, using a UV gun (at 344 nm; Spectroline, ENF-240C). Further guidance can be requested and all of the files required to 3D print MEMICs can be downloaded at www.carmofon.org.

Lactate Quantification.

Typically – cells were seeded on each well of a 96-well plate in 1 mL media. After 24 h of culture, media were collected and centrifuged to decant cell debris, and the supernatant was used for measurements. Extracellular lactate was measured using colorimetric tests (Trinity Biosciences 826-10, 735-10, and 735-11).

Tube Formation Assay.

Macrophages alone or cocultured with tumor cell lines were cultured in glass bottom 96-well plates (Cellvis; P96-1-N) or within MEMICs for 24 h under 1% oxygen and 30 mM NaLactate or under 21% oxygen and 30 mM NaCl. On the next day, a 2:1 vol/vol Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel:Collagen I (Corning 356231 and BD354236, respectively) was mixed at 1:3 vol/vol with fresh media without FBS. This mix was kept on ice. SVEC cells were trypsinized and resuspended in cold media (at cells/mL) and then mixed at 1:1 with the matrix mix. Then the media were aspirated from the macrophage container and 50 μL of the SVEC/matrix mix was added per well (in a 96-well plate) or 100 μL per MEMIC. SVEC cells were allowed to decant by keeping the plate on ice for 10 min and then the matrix was allowed to gelate by incubation for 30 min at 37 C. Finally, fresh media were added and the cells were incubated overnight (for 96-well plates) under the same conditions as mentioned above or for 2–5 d if in the MEMIC.

Conditioned Media Analysis and Chemokine Screening.

Macrophages were cultured for 24 h under normal (21%) or low (1%) oxygen levels and with 30 mM NaLactate or NaCl. Then, growth media were filtered using Syringe filters (Fisherbrand; 09-719B) and concentrated for large molecules (3 kDa), using Amicon Ultra filters (UFC900324). For experiments involving treatments with conditioned media, the concentrated high molecular-weight fraction was rediluted in fresh media without FBS. Conversely, the flow-through media from the columns (3 kDa) were used as the low molecular-weight fraction after addition of fresh FBS. Semiquantitative chemokine detection was performed using Proteome Profiler Antibody Arrays for 111 different analytes (R&D; ARY028) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitative chemokine measurements, a 32-plex Luminex kit (Millipore; MCYTMAG-70K-PX32) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Chemical Inhibitors and Activators.

Different pathway agonists were used by diluting them in cell culture media. We used four to five different concentrations to obtain a dose–response curve. Chemicals used were 20(S)-hydroxycholesterol (Shh agonist; Tocris 4474), LiCl (Wnt agonist; Sigma L7026), IL4 (R&D 04-ML), LPS (from Salmonella typhimurium; Sigma L6143), INF (R&D 485-MI), and TNF (410-MT). Notch signaling was activated by coculturing macrophages with OP9 cells engineered to express DLL1 (54). Inhibitors against different pathway were also used. The MAPK/ERK pathway was inhibited using MEK inhibitors U0126 (CST 9903) or PD98059 (CST 9900) or by inhibiting c-Raf via Sorafenib tosylate (Selleck S1040) or GW5074 (Selleck S2872). VEGF signaling was inhibited using Axitinib (Selleck S1005) or Linifanib (Selleck S1003). Inhibitors for other pathways included Cyclopamine-KAAD (Shh inhibitor; Calbiochem 239804), Celastrol (TNF inhibitor; Tocris 3203), FH 535 (Wnt inhibitor; Tocris 4344), AZD1480 (pan-Jak inhibitor; Selleck S2162), and the Notch (gamma-secretase) inhibitors DAPT (Tocris 2634) and LY411575 (Selleck S2714).

Extraction of Total mRNA.

Macrophages were cultured for 24 h under normal (21%) or low (1%) oxygen levels and with 30 mM of NaLactate or NaCl. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen; 15596026).

qPCR.

Real-time qPCR analysis of transcripts was performed using TaqMan probes according to manufacturer’s instructions. Probes used were Arg1 (Mm00475988_m1), Vegfa (Mm00437306_m1), Nos2 (Mm00440502_m1), and Mrc1 (Mm01329362_m1).

Whole-Transcriptome Sequencing.

After ribogreen quantification and quality control of Agilent BioAnalyzer (RIN8), poly(A) RNA was isolated using a Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Micro Kit (Life Technologies) from 1 g of total RNA. mRNA was then fragmented using RNaseIII and purified. The fragmented samples quality and yield were evaluated using Agilent BioAnalyzer. Subsequently, the fragmented material underwent whole-transcriptome library preparation according to the Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 protocol (Life Technologies), with 16 cycles of PCR. Samples were barcoded, and template-positive Ion PI ion sphere particles (ISPs) were prepared using the ion one-touch system II and Ion PI Template OT2 200kit v2 Kit (Life Technologies). Enriched particles were sequenced on a Proton sequencing system, using 200-bp version II chemistry. An average of 40 million reads per sample were generated.

Analysis of RNA-seq Data.

Sequences obtained from the RNA-seq platform were aligned with a hybrid 2-pass method (using first rnaStar and then BWA). Merged BAM files were processed with HTSeq counts to generate the counts matrices. The processed data were then analyzed using the DESeq2 (55) package for R. GSEA analysis was also performed in R, using the gsea function of the phenoTest package.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Matlab. Student’s t test was used to compare pairs of data. Groups of data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA if data were normally distributed or a Kruskal–Wallis test if the data were not normally distributed. Error bars, P values, and statistical tests are reported in corresponding figure legends.

Data and Software Availability.

RNA-seq datasets are deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus.

Discussion

Tumor progression is commonly seen as a deregulated, chaotic process, yet our data suggest that gradients of metabolites act as tumor morphogens and provide a local source of organization by inducing phenotypic patterns in macrophages. This process requires three simple conditions that are common in all solid tumors: alterations in cell metabolism, aberrant vascularization, and the presence of responsive stroma. These features lead to gradients of metabolites that orchestrate a coordinated and spatially organized angiogenic response.

It is possible that metabolite gradients also organize other cell types within the tumor microenvironment, including other immune cells (40–45) and malignant cells themselves. For example, low glutamine levels found in blood-deprived necrotic tumor cores lead to histone hypermethylation and dedifferentiation of cancer cells (46). Extracellular metabolite sensing is at the core of biological organization and is conserved from bacteria to mammals (47). Thus, we speculate that metabolites represented the primal cues for positional information, which was then coopted by signaling molecules during metazoan evolution. Understanding the processes required for multicellular self-organization in tumors may allow identification of targetable features that are independent of specific genetic mutations and thus less prone to therapeutic resistance.

Materials and Methods

Cells were cultured under standard conditions, using DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Images were acquired using an inverted wide-field fluorescent microscope (Zeiss AxioObserver.Z1) and the images were processed in Matlab, using custom-made analysis routines that are available upon request. All animal studies were performed using protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Details about the analytical solution to the theoretical model can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Mathematical Modeling

Rationale.

We wanted to know the relevance of spatial structure in local angiogenesis. This model explores whether a strategy of responsive angiogenesis is more efficient than a constitutive (or uniform) one. By responsive angiogenesis we mean a cellular system that would restrict the production of proangiogenic factors only to regions where resources are limiting. The intuition behind this model is that although new vessels are beneficial for neighboring cells, their impact on cell growth has diminishing returns. At the same time, making new vessels is a costly process so to grow faster, a tumor may need to optimize the allocation of its new vessels. Our experimental evidence supports the idea of a responsive angiogenesis strategy as only ischemic macrophages secrete high levels of VEGFA that leads to local tube-like morphogenesis in experiments performed in the MEMIC. Two models are presented here. First, we present a hybrid continuous-discrete agent-based simulation that expands our previously developed model (21) where ischemic cells secrete a costly angiogenic factor. Here as well, the responsive strategy leads to increased tumor growth. Second, an analytical solution to the question of local investment vs. return shows that—if resources are not homogeneously distributed—responsive angiogenesis is always better than constitutive or indiscriminate vascularization. For simplicity, both models consider tumor cells in general and blood vessels. Yet the same results are expected if a more complicated model, considering multiple cell compartments, is used.

Agent-Based Model.

To determine the importance of the responsive strategy of TAM-infiltrated tumors and to emphasize the role of spatial structure rather than the specifics of particular cell types, we modeled the tumor mass as a population of cells (representing both cancer cells and TAMs) that stimulated local blood vessels in a constitutive manner or in response to local levels of nutrient deprivation. Our simulations predicted that TAM-infiltrated tumors using a responsive strategy grew faster while producing lower levels of costly stroma-stimulating molecules. This is a hybrid agent-based model where cells are modeled in a discrete manner (as agents) and solutes such as nutrients and oxygen are modeled in a continuum space. Their local concentrations are determined using partial differential equations used in typical diffusion and reaction models. This approach has been successfully applied previously to model different aspects of tumor biology (e.g., refs. 55–58). Our model was implemented in a Java package designed to study complex interactions between many agents in a spatial environment. It was specifically designed to study interactions among cell groups and it has been used extensively in modeling bacterial biofilms (59, 60). The computational framework allows implementing multiple species and different metabolites and in an intrinsically spatial model.

The framework we use is detailed extensively elsewhere (59, 60). Briefly, the software allows multiple-system geometries and boundary conditions that in our present model were cyclic boundaries. In this off-grid system, particles (agents or cells) are modeled as hard spheres whereas the concentrations of solutes are approximated using a multigrid numerical solver. This assumes a (pseudo)steady state for reaction–diffusion that is reasonable because the processes governing solute dynamics (e.g., consumption, secretion, and diffusion) are orders of magnitude faster than cellular dynamics (growth, death, mitosis, and so on).

We initiate our model by randomly seeding blood vessels (these agents cannot be pushed) and they are inactive (do not provide resources ). Then in the center of the modeled region we placed a few agents (5–10) aimed at representing a TAM-infiltrated tumor (). Initially agents are deprived of resources because initial levels are set to zero. When the simulation starts, agents start secreting an angiogenic factor because they are starved.

For simplicity, we did not model oxygen or lactate explicitly, but we considered a more general case where cells consume “resources” () that diffuse from blood vessels. stimulates blood vessels to release resources that agents consume to grow and divide. If resources accumulate, agents stop secreting the factor and vessels diminish the release of resources. To model constitutive and responsive angiogenic strategies, we simply tuned the rate at which inhibits the secretion of with the parameter (equations below and in Table S2).

Table S2.

Stoichiometric table used in agent-based model

| Process | C | Rate | ||

| Tumor growth | 1 | |||

| Resource perfusion | 1 | |||

| f secretion (responsive) | 1 | |||

| f secretion (constitutive ) | 1 |

Italics denote the implementation of alternative angiogenic strategies. Units are relative to cell biomass.

Dynamic equations.

Tumor growth.

Tumor growth follows saturation kinetics whereas the secretion of has a linear cost (). In the responsive angiogenesis case, this cost is restricted to ischemic regions as high resource levels inhibit the secretion of .

-

•Responsive angiogenesis:

[S1] -

•Constitutive angiogenesis (when ):

[S2]

Resource dynamics.

Local levels are given by a balance of diffusion, production by , and consumption by :

| [S3] |

Angiogenic factor dynamics.

Local levels are given by a balance of diffusion and production by . The maximum level of production is () but in the responsive angiogenic strategy, resources can reduce its production.

-

•Responsive angiogenesis:

[S4] -

•Constitutive angiogenesis ():

[S5]

Theoretical Model and Its Analytical Solution.

We wanted to obtain a more general answer to the question whether a responsive angiogenic strategy is better than a constitutive strategy. We thus created a simple model where cells need to “decide” whether an investment in acquiring more resources (in angiogenesis) would provide an increase in growth rate that would pay off the investment. The trade-off emerges from the diminishing returns of nutrients in the growth model (Fig. S6F).

Cells lie along the x axis () (Fig. S6F). The spatial profile of resources is imposed. It is generated by competition between consumption and diffusion, with a source on one side (a blood vessel). For simplicity, we assume a linear gradient of resources:

| [S6] |

We assume that the growth rate dependence on resources has diminishing returns: The growth rate increases with resources, but levels off at high levels that we model with saturation kinetics (see below).

Cells invest in secreting cytokines that increase the local resource density: .

The cost of this investment is linearly proportional to the resource increase: .

The benefit of this investment is a better growth rate: .

The optimal investment depends on location.

The optimal investment is reached when the Profit, defined as , is maximized:

| [S7] |

The uniqueness of the solution of [S7] is ensured by the concavity of the growth rate. The optimal investment is reached when the slope of in is . Let us call this point (Fig. S6F). Then

| [S8] |

Note that depends only on the detail of the curve and . It does not depend on the position . Therefore, the spatial variation of is directly dictated by that of (Fig. S6G).

By definition, is positive. Therefore, Eq. S7 admits a solution only if . If , it is not possible to find a for which the slope of is .

Saturating kinetics.

If follows saturating kinetics in the form ( is the half-saturation resource density, and is the maximum growth rate), then can be derived exactly:

| [S9] |

And therefore

| [S10] |

In the following, we set , for instance by rescaling time. We also rescale space and resource density so that and .

A responsive strategy performs better than a constitutive strategy.

At any location of the system, the optimal investment is given by . In particular, a strategy where the investment is constitutive is suboptimal. To illustrate this point, we compare three investment strategies:

-

•

Responsive investment: Resources density is raised to the optimal level across the entire space. Cells invest more in poorly fed areas ().

-

•

Constitutive investment: Resources density is raised uniformly. The investment level is equal to the maximal investment in the responsive strategy ().

-

•

No investment: Cells do not invest at all ().

We compare the three strategies in the case of a linear gradient of resources. Specifically, the total growth rates and total cost of investment can be calculated analytically as a function of the half-saturation constant and , unit cost of investment:

| [S11] |

We define the effective growth rate as

| [S12] |

We define also the return on investment (ROI) as

| [S13] |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the entire J.B.X., J.A.J., and C.B.T. laboratories for useful discussions and feedback during the development of this project and on the manuscript. We specially thank Guillermina Altomonte, Ben Steventon, Wilhelm Palm, and Lydia Finley for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R00CA191021 (to C.C.-F.), U54 CA209975 (to J.B.X.), and P30 CA008748 (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant) and by a grant from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center (to J.B.X. and J.A.J.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: C.B.T. is a founder of Agios Pharmaceuticals and a member of its scientific advisory board. He also serves on the board of directors of Merck and Charles River Laboratories.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE93702).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1700600114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396(6712):643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: Causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Canc. 2010;1805(1):105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens PJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501(7467):338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laughney Ashley M, Elizalde S, Genovese G, Bakhoum SF. Dynamics of tumor heterogeneity derived from clonal karyotypic evolution. Cell Rep. 2015;12(5):809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gundem G, et al. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;520(7547):353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C-Z, et al. Chromothripsis from DNA damage in micronuclei. Nature. 2015;522(7555):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature14493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabassum DP, Polyak K. Tumorigenesis: It takes a village. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(8):473–483. doi: 10.1038/nrc3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, Werb Z. Tumors as organs: Complex tissues that interface with the entire organism. Dev Cell. 2010;18(6):884–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407(6801):249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(6):417–427. doi: 10.1038/nrd3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedl P, Alexander S. Cancer invasion and the microenvironment: Plasticity and reciprocity. Cell. 2011;147(5):992–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marusyk A, et al. Non-cell-autonomous driving of tumour growth supports sub-clonal heterogeneity. Nature. 2014;514(7520):54–58. doi: 10.1038/nature13556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleary AS, Leonard TL, Gestl SA, Gunther EJ. Tumour cell heterogeneity maintained by cooperating subclones in Wnt-driven mammary cancers. Nature. 2014;508(7494):113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):325–337. doi: 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(1):27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1955;9(4):539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(11):891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmona-Fontaine C, et al. Emergence of spatial structure in the tumor microenvironment due to the Warburg effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(48):19402–19407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311939110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colegio OR, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513(7519):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis C, Murdoch C. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: Implications for tumor progression and anti-cancer therapies. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(3):627–635. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenes M, et al. Macrophage metabolism controls tumor blood vessel morphogenesis and metastasis. Cell Metab. 2016;24(5):701–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: Enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolpert L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J Theor Biol. 1969;25(1):1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(69)80016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green JB, Sharpe J. Positional information and reaction-diffusion: Two big ideas in developmental biology combine. Development. 2015;142(7):1203–1211. doi: 10.1242/dev.114991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briscoe J, Small S. Morphogen rules: Design principles of gradient-mediated embryo patterning. Development. 2015;142(23):3996–4009. doi: 10.1242/dev.129452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayor R, Carmona-Fontaine C. Keeping in touch with contact inhibition of locomotion. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(6):319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Kasmi KC, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(12):1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashe HL, Briscoe J. The interpretation of morphogen gradients. Development. 2006;133(3):385–394. doi: 10.1242/dev.02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers KW, Schier AF. Morphogen gradients: From generation to interpretation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27(1):377–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cattin AL, et al. Macrophage-induced blood vessels guide Schwann cell-mediated regeneration of peripheral nerves. Cell. 2015;162(5):1127–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Secomb TW, Alberding JP, Hsu R, Dewhirst MW, Pries AR. Angiogenesis: An adaptive dynamic biological patterning problem. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):e1002983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu-Emerson C, et al. Lessons from anti-vascular endothelial growth factor and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor trials in patients with glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(10):1197–1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Neill LAJ, Hardie DG. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 2013;493(7432):346–355. doi: 10.1038/nature11862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearce EL, Poffenberger MC, Chang CH, Jones RG. Fueling immunity: Insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science. 2013;342(6155):1242454. doi: 10.1126/science.1242454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neill LAJ, Pearce EJ. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J Exp Med. 2016;213(1):15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siska PJ, Rathmell JC. T cell metabolic fitness in antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang C-H, Pearce EL. Emerging concepts of T cell metabolism as a target of immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(4):364–368. doi: 10.1038/ni.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brand A, et al. LDHA-associated lactic acid production blunts tumor immunosurveillance by T and NK cells. Cell Metab. 2016;24(5):657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan M, et al. Regional glutamine deficiency in tumours promotes dedifferentiation through inhibition of histone demethylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(10):1090–1101. doi: 10.1038/ncb3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chantranupong L, Wolfson RL, Sabatini DM. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms across evolution. Cell. 2015;161(1):67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee Dong C, et al. A lactate-induced response to hypoxia. Cell. 2015;161(3):595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brader P, et al. Imaging of hypoxia-driven gene expression in an orthotopic liver tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2900–2908. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gocheva V, et al. IL-4 induces cathepsin protease activity in tumor-associated macrophages to promote cancer growth and invasion. Genes Dev. 2010;24:241–255. doi: 10.1101/gad.1874010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez T, Hanahan D. Elevated levels of IGF-1 receptor convey invasive and metastatic capability in a mouse model of pancreatic islet tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:339–353. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bong KW, et al. Non-polydimethylsiloxane devices for oxygen-free flow lithography. Nat Commun. 2012;3:805. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cox ME, Dunn B. Oxygen diffusion in poly(dimethyl siloxane) using fluorescence quenching. I. Measurement technique and analysis. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem. 1986;24:621–636. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Induction of T cell development from hematopoietic progenitor cells by delta-like-1 in vitro. Immunity. 2002;17:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson AR, Weaver AM, Cummings PT, Quaranta V. Tumor morphology and phenotypic evolution driven by selective pressure from the microenvironment. Cell. 2006;127:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Enderling H, Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P. Tumor morphological evolution: Directed migration and gain and loss of the self-metastatic phenotype. Biol Direct. 2010;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basanta D, Anderson AR. Exploiting ecological principles to better understand cancer progression and treatment. Interface Focus. 2013;3(4):20130020. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xavier JB, Picioreanu C, Van Loosdrecht MCM. A framework for multidimensional modelling of activity and structure of multispecies biofilms. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1085–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xavier JB, de Kreuk MK, Picioreanu C, van Loosdrecht MCM. Multi-scale individual-based model of microbial and bioconversion dynamics in aerobic granular sludge. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:6410–6417. doi: 10.1021/es070264m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jain M, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies a key role for glycine in rapid cancer cell proliferation. Science. 2012;336:1040–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1218595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Intlekofer A, et al. Hypoxia induces production of L-2-hydroxyglutarate. Cell Metab. 2015;22:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chouchani ET, et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2014;515:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.