Empirical research has clearly demonstrated that effective and emotionally nurturing parenting practices constitute salient protective factors in the lives of children and youth (Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003). In contrast, neglectful and punitive parenting practices have been linked to a wide range of internalizing and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents, as well as increased risk for new parents to continue previous patterns of abuse and neglect (Wiggins, Mitchell, Hyde, & Monk, 2015). Low income Latino/a immigrants are unlikely to benefit from evidence-based parenting interventions due to multiple access barriers such as low SES, language difficulties, immigration status, limited insurance coverage, exploitative work environments, and anti-immigration climates (Montalvo, 2009). The consequences for low-income Latinos/as not being able to access mental health services aimed at enhancing their parenting practices are deleterious. For example, disrupted parenting practices have been associated with increased risk for drug use, delinquency, and school dropout among Latino/a youth (Estrada-Martínez, Padilla, Caldwell, & Schulz, 2011).

Historically, social workers have been at the forefront of serving individuals and families impacted by contextual adversity and inequalities (Fong & Pomeroy, 2011; McLaughlin, 2002; Palinkas, 2010; Zayas & Bradlee, 2014). Social workers have also influenced in important ways the development and dissemination of culturally relevant evidence-based parenting interventions for diverse populations (Holleran Steiker, 2008; Marsiglia & Booth, 2014; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2008). Despite these advances, there continues to be a high need for clinical social work practice aimed at addressing the mental health needs experienced by the most vulnerable and underserved populations throughout the US (Heller & Gitterman, 2011).

The purpose of this paper is to reflect on the process of change that we documented as a group of underserved Latino/a immigrant parents were exposed to a culturally adapted evidence-based parenting intervention. We have pursued our applied program of research informed by a cultural adaptation framework, in an effort to increase the cultural relevance of the parenting interventions offered to the target Latino/a population.

Background

Identifying the needs of Latino/a parents

Our program of prevention parenting research is based in an urban setting in the Midwestern United States (US), characterized by intense contextual challenges such as high levels of crime, community violence, poverty, and racial/ethnic segregation. Back in 2005, we established a collaboration with key community leaders to explore alternatives to support the local Latino/a community. Community representatives uniformly expressed a high need to disseminate evidence-based prevention parenting interventions, aimed at benefiting families with children experiencing mild to moderate behavioral problems.

In response, we implemented a qualitative investigation with Latino/a immigrant parents (n = 83), aimed at learning about their life experiences and parenting needs (Author, 2009). Parents provided detailed narratives describing common challenging backgrounds such as being exposed to harsh and neglectful parenting as children, chronic poverty, and community violence. Participants also reflected on the contextual adversity that they have experienced in the US such as work exploitation, language barriers, and racial/ethnic discrimination (Author, 2009). In addition, parents expressed a strong desire to participate in an intervention aimed at improving their parenting practices, provided that such an intervention was culturally relevant (Author, 2009). The qualitative study became a cornerstone of our applied program of research aimed at comparing the differential impact of two culturally adapted versions of an evidence-based parenting intervention. Below, we describe this process in detail.

Differential adaptation of an efficacious parenting intervention

Empirical research has demonstrated that Latino/a populations can benefit from culturally adapted versions of efficacious interventions originally developed with a majority of Euro-American populations (Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, & Schwartz, 2011). Thus, after completion of the qualitative study, we obtained funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to empirically test the differential impact of two culturally adapted versions of the efficacious parenting intervention known as Parent Management Training, the Oregon Model (PMTOR). We selected PMTO as the foundation of our program of prevention parenting research because it is an intervention with demonstrated long-term effectiveness in large-scale prevention and clinical trials (Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2009). PMTO also has a close cultural fit with salient Latino/a cultural values, traditions, and parenting expectations (Author, 2012; Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011).

CAPAS intervention

The first cultural adaptation of the PMTO intervention for Latinos/as was conducted by Domenech Rodríguez and colleagues with funding support provided by NIMH. The Spanish version of the PMTO intervention was titled “CAPAS: Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación” (Raising Children with Love, Promoting Harmony and Self-Improvement; see Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011). Two core PMTO components (i.e., monitoring and supervision, family problem solving) were translated and adapted by researchers conducting PMTO implementation in México (Baumann, Domenech Rodríguez, Amador Buenabad, Forgatch, & Parra-Cardona, 2014).

The sessions covered in the CAPAS intervention include all the core components of the original PMTO intervention: (a) positive involvement, (b) skills encouragement, (c) limit setting, (d) monitoring and supervision, and (e) family problem solving. The CAPAS intervention was developed according to the guidelines of a well-defined cultural adaptation framework, known as the Ecological Validity Model (EVM; Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 2006). Briefly, the EVM specifies the need to conduct content and intervention delivery adaptations by considering the dimensions of language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context. To illustrate, the dimension of language was addressed by ensuring the linguistic appropriateness of the translated PMTO manual and all intervention delivery materials. Further, Latino/a cultural experts from the US and Latin America reviewed the culturally adapted manual and supportive materials and offered detailed feedback to ensure linguistic appropriateness of translated materials. The dimension of persons was addressed by carefully selecting recruiters, data collectors, and interventionists who were fully bilingual and shared the ethnic heritage of participants. We refer the reader to the original source, which clearly describes the process of adaptation of the CAPAS intervention (see Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011).

CAPAS-enhanced intervention

Our research group expanded the CAPAS intervention by adding two culture-specific sessions. These sessions offered a cultural framework to the intervention centered on immigration and biculturalism issues. For example, parents were prompted to discuss in these sessions how specific immigration challenges such as work exploitation or racial discrimination have impacted their parenting practices. Reflections were also promoted and focused on discussing the impact of biculturalism on family relations (e.g., conflicts between parents and children resulting from contrasting cultural preferences). In addition, each core component of the PMTO intervention was introduced to parents according to relevant cultural frameworks illustrated by Latino/a parents’ qualitative quotes collected in the exploratory study. Finally, because role plays constitute a key intervention delivery tool of the PMTO intervention, role plays of challenging parenting situations were crafted to reflect contextual issues that deeply impact Latino/a immigrant parents. For instance, limit setting role plays were set up by asking parents to imagine the challenge that would represent to them having to implement discipline with their children after experiencing racial discrimination at work. Table 1 provides a comparison between the CAPAS and CAPAS-enhanced interventions according to presentation approach and content.

Table 1.

Presentation Approach and Content of CAPAS and CAPAS-enhanced Interventions.

| CAPAS | CAPAS-Enhanced | |

|---|---|---|

| Presentation Approach | 1. One introductory session provided an overview of the PMTO intervention, including its guiding principles. 2. Intervention materials are linguistically and culturally appropriate. Content is limited to core PMTO components. 3. Role plays focus exclusively on PMTO parenting practices. 4. Interventionists were Latino/a bilingual professionals, members of the Detroit community. |

1. One introductory session provided an overview of the PMTO intervention. Relevant qualitative quotes were used to introduce each core PMTO component according to frameworks focused on immigration and biculturalism. 2. Intervention materials are linguistically and culturally appropriate. Two culture-specific sessions are included in the intervention. 3. Role plays are set up by integrating immigration challenges experienced by parents. For example, implementing discipline with children after experiencing racial discrimination at work. 4. Interventionists were Latino/a bilingual professionals, members of the Detroit community. |

| Content | 1. Participants were exposed to the core components of the PMTO intervention (i.e., Giving Good Directions, Teaching Children Through Encouragement, Setting Limits, Problem Solving, and Monitoring) 2. Two booster sessions were included to refine previously learned parenting skills. The content of these sessions was focused on parenting skills and determined by participants based on the specific skills they wanted to enhance. |

1. In addition to exposure to the core PMTO components, two culture-specific sessions focused on: (a) Being a Latino immigrant parent and coping with immigration stressors (e.g., racism), and (b) biculturalism and developing an identity as a bicultural family. 2. Each core component of the PMTO intervention was introduced by using qualitative quotes that illustrated the relevance of specific parenting skills, within frameworks of immigration and biculturalism. 3. One booster session was included to refine previously learned parenting skills. Only one booster session was offered to CE parents to maintain equivalent dosage of total number of sessions between interventions. |

The Process of Enhancing Parenting Practices

Our reflections center on describing the process of change that we documented after Latino/a immigrant parents were exposed to the CAPAS and CAPAS-enhanced interventions. Whereas our program of applied research has focused on low-income Latino/a immigrants, we expect that many of the insights described below can be applicable to the dissemination of alternative parenting prevention interventions with other underserved ethnic minority populations.

Design and target population

We delivered the PMTO adapted interventions to 130 parents over a period of 2 years. Specifically, 66 parents were exposed to the CAPAS-original intervention (36 mothers, 30 fathers) and 64 parents participated in the CAPAS-enhanced intervention (35 mothers, 29 fathers). Both adapted interventions were delivered in a group format integrated by no more than 20 individual parents per group. Both interventions were delivered over a period of 12 weeks and each weekly parenting session lasted 2 hours. Based on the PMTO model, only parents participated in intervention sessions to facilitate open discussion of parenting challenges as well as to practice new parenting skills. Parents were expected to implement these skills with their children at home between sessions. In each subsequent session, parents reported back on their success or challenges at implementing new parenting skills. Sessions heavily relied on role plays to help parents both learn and master the skills under a variety of circumstances by targeting areas of difficulty identified by them. Two interventionists (one female, one male) delivered each of the interventions. All parents were Spanish-speaking and first generation Latino/a immigrants. Approximately 75% of parents reported an annual combined family income lower than $40,000 and the average number of children in the household was three, with children's ages ranging from 4 to 12 years old. Additional participant and research design characteristics are reported elsewhere (Author, 2015a).

The documentation guiding our reflections consisted of videos from parenting sessions that were analyzed to ensure fidelity of implementation, notes from live supervision of parenting sessions, selective qualitative quotes provided by participants, and journaling from coaching sessions aimed at supporting group facilitators throughout the various phases of intervention delivery. These reflections go in line with our research findings, indicating that the process of change reported by participants in both interventions was similar with regards to the core PMTO parenting practices. However, parents exposed to the CAPAS-enhanced intervention reported an additional benefit by addressing parenting topics within frameworks of immigration and biculturalism (Author, 2015b). Immigration and biculturalism issues were discussed in the CAPAS-original intervention only to the extent that these topics were addressed by parents.

Guiding theories

The Social Interaction Learning Theory (SIL; Patterson & Yoerger, 2002) is the foundational theory of PMTO. SIL combines Social Interaction Learning Theory (ref; bandura) and Coercion Theory. Briefly, SIL specifies that parenting practices are a key mediating mechanism between family contexts and child adjustment. Social Interaction Theory informs components of the model targeting parenting practices aimed at improving child outcomes. For example, the component of skills encouragement in the PMTO intervention focuses on the importance for parents to facilitate their children's new behaviors by way of setting clear expectations that are developmentally appropriate and also by modeling appropriate behavior. Thus, if the goal is for an 8-year-old to be able to clean her room independently, parents should engage in gradual behavior modeling of small behaviors that are necessary to help her accomplish the selected task (e.g., picking up dirty clothes, collecting trash). In addition, parents are coached on strategies aimed at creating an environment of motivation and recognition of children's accomplishments (e.g., incentives and rewards).

Coercion Theory is integrated within SIL and provides a description of interactional patterns and processes associated with ineffective parenting (Patterson & Yoerger, 2002; DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2004). Brief concepts of coercion theory are presented to parents when introducing limit setting skills to help them understand how a negative interaction (e.g., child non-compliance) can lead to escalation (e.g., children not following a command, parents yelling). Escalation can lead parents to relinquish their attempts to implement discipline, as a way to avoid escalation and conflict with children. These well-intentioned attempts to maintain peace result in strengthening the child's misbehaviors through negative reinforcement.

A family resilience framework informs our intervention delivery activities as we strive to focus on enhancing existing family strengths and the acquisition of new resources (Walsh, 2015). An advocacy framework (Faust, 2008) also informs our work with families. Thus, we collaborate with local agencies and institutions to help each family obtain the resources they need to address a variety of family challenges (e.g., referrals to immigration services or English as a second language classes, assistance with food stamps applications).

The process of change

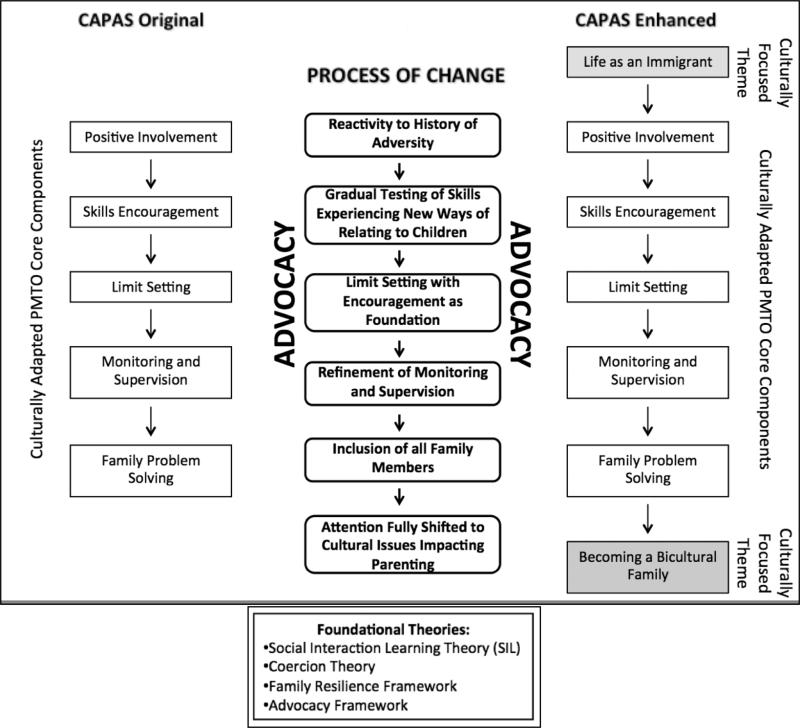

Figure 1 illustrates the intervention components to which parents were sequentially exposed in both adapted interventions. In the figure, core culturally adapted PMTO components are differentiated from culturally-focused components consistent with the literature on cultural adaptations that distinguish transformative from additive adaptations (Bernal & Domenech Rodríguez, 2012). In the center of the figure, we present key characteristics of the process of change that we have documented parents are likely to experience as they progress through the intervention.

Figure 1.

Process of Change Associated with Both Culturally Adapted Parenting Interventions.

Engagement

Successful engagement of parents in the first session is essential, particularly if parents are not mandated to participate in a parenting intervention. Research indicates that non-mandatory parenting programs are at risk for higher drop out rates compared to programs in which participation is required (Baker, Arnold, & Meagher, 2011).

Safety

We implement parenting groups in an urban setting impacted by poverty, community violence, and racial segregation. The availability of high quality prevention mental health services for Latinos/as continues to be limited and agencies offering these services are usually overwhelmed with high client loads and limited bilingual staff. Because families in the community are affected by a variety of contextual stressors, the rapport and joining skills of the intervention delivery team are essential. To this end, we implement each parenting group with two interventionists. One interventionist (third author) is a Latina (female) clinical social worker, affiliated with the largest provider of mental health services for ethnic minority populations in the area. The second interventionist (fourth author) is a Latino (male) professional and community leader with an extensive history of service in the community. We offered the intervention at a local church known for its long history of advocacy in the Latino/a community. Specifically, parents have consistently identified this setting as the ideal site for implementation based on the level of safety that the Latino community associates with this location. We did not advertise our groups as religious-based.

Initial motivation

We relied on a variety of activities to promote an initial sense of group cohesion. For example, we welcomed participants by offering dinner, ice breaking activities, and brief group exercises to facilitate interactions among group members. Having established initial rapport, we implement a guided imagery exercise. Briefly, this exercise is informed by motivational interviewing principles (Miller & Rollnick, 2013), and it was aimed at enhancing the parents’ commitment to embrace nurturing and safe parenting practices. Specifically, we asked participants to visualize themselves and their children over time, witnessing how their children become adolescents. At this point, we asked parents to see the many successes of their children as well as risk situations to which youth are likely to be exposed and that parents will have no direct control over (e.g., exposure to drugs). We also asked parents to visualize how their parenting practices constituted a powerful protective factor in the lives of their children.

Consistently, we have received feedback from parents reporting that this guided imagery exercise was an important motivator for their initial engagement in the parenting group. After conducting post-intervention interviews to identify factors associated with the high rates of retention of parents (86%) in the parenting program, including retention of fathers (85%) (Author, 2015b), a consistent theme reported by participants referred to the identification in the initial session of a sense of purpose associated with the importance of enhancing their parenting skills. For parents already committed to improving their parenting practices, this exercise reinforced their existing motivation. For parents, particularly fathers, who felt pressured by their spouses to attend the first session, this exercise provided them with an opportunity to reflect on the future life challenges that their children will face and their critical role as parents.

Exposure to the core parenting components and associated impact

Adherence to the PMTO model requires a sequential exposure to the core components of the intervention. This premise is rooted in empirical data from extensive clinical trials describing effective mechanisms of change associated with the PMTO intervention (Forgatch et al., 2009). We have followed this premise in our program of research with encouraging results. Specifically, quantitative findings from a randomized controlled trial aimed at examining the differential impact between the CAPAS and the CAPAS-enhanced intervention, indicated high participant satisfaction with both adapted interventions. No significant differences on participant satisfaction were observed between the adapted interventions. With regards to parenting outcomes, statistically significant improvements of the participants’ parenting skills were observed in the two adapted interventions when compared to a wait-list control group at 6-month follow-up. With regards to child outcomes, parents exposed to the CAPAS-enhanced intervention reported the most significant improvements when compared to CAPAS and the wait-list control group. We hypothesize that the incremental effect of the CAPAS-enhanced intervention may be associated with the fact that parenting examples, role plays, and discussions were fully informed by key immigration and cultural experiences that impact the parenting practices of Latino/a immigrant families (e.g., parenting while managing biculturalism conflicts). A detailed presentation of these findings is beyond the scope of this paper and we refer the reader to the original source (Author, 2015b).

Next, we present the sequence of exposure to the core PMTO components. We have included selective quotes to illustrate the participants’ perceived relevance of each component. We refer the reader to the original source for a full description of the qualitative findings for both adapted interventions (see Author, 2015a).

Positive involvement and encouragement

Positive involvement refers to coaching parents about new ways of providing loving attention to their children. Encouragement consists of assisting parents with specific skills grounded in incentives and motivation, with the ultimate goal of promoting pro-social behaviors in children and youth (Forgatch et al., 2009). These PMTO components are introduced to parents by making reference to the cultural value of familismo, which highlights the importance of family life and harmony (Falicov, 2014). Specifically, we highlighted to parents how the promotion of these parenting practices can increase harmonious family relations, particularly as children become more self-sufficient with regards to daily routines and other responsibilities that are expected from them. In addition, familismo refers to open expression of nurturance in the parent-child relationship, which is an outcome that is targeted as we coach parents how to model desired behaviors to children.

Gradual behavior modeling of parenting behaviors constitutes a cornerstone of the PMTO intervention. Thus, interventionists heavily rely on role plays focused on practicing with parents how to give good directions to children and how to set up structures aimed at helping children achieve mastery of a variety of behaviors that are relevant to their development (e.g., brushing their teeth, cleaning their room). Specific tools such as tokens and incentive charts are used to promote gradual behavior change within a framework of motivation for children.

It is important to note that parents who experienced nurturing parenting as children, are likely to resonate with the core principles of these components, which highlight the importance of motivating children as they are supported to master the various skills that will allow them to achieve independence in life (e.g., completing personal hygiene routines on their own). However, we have repeatedly confirmed that for parents who have experienced adversity and harsh parenting as children, exposure to these components may trigger a sense of loss for what they did not experience in their childhood. Parents have also reported how they learned to minimize recognition in their own lives in order to survive adverse contexts. Common phrases that parents with challenging backgrounds may express when presented with encouragement topics are: “Why are we supposed to reward our children for behaviors they are expected to do?” “The world is a very challenging place. If we reward our children for what they do right, we are setting them up for failure. The world does not work like that.” When facing these reactions from parents, it is essential to embrace a social justice perspective. That is, for parents who experienced frequent physical punishment as children, it can be particularly challenging and painful to realize that children and human beings are entitled to protective and nurturing environments. In the CAPAS-enhanced intervention, we presented relevant qualitative quotes from parents describing how experiences in their countries of origin (e.g., extreme poverty), as well as socio-cultural norms (e.g., children should always obey without expecting parental recognition), influenced their decision to adopt parenting expectations characterized by an emphasis on children’ obedience and limited recognition of children's good behaviors.

We considered that the challenges associated with implementing positive involvement and encouragement were also likely to resemble those experienced by parents from non-Latino/a racial/ethnic backgrounds, particularly if they have experienced cumulative trauma, oppression, and lack of nurturing parenting experiences as children. We utilized a double approach to address this issue, which may also be useful when delivering alternative parenting interventions to non-Latino/a target populations.

First, we presented parallels of the concept of encouragement to the lives of parents as adults. For example, we asked parents to reflect on how they felt when employers praised their productivity and offered them raises or monetary incentives for their good performance. We have consistently confirmed how parents positively react to these reflections and openly discuss the importance of appropriate recognition in the lives of human beings. In addition, a key premise of the PMTO intervention refers to the need to emphasize “doing rather than talking.” Thus, we asked parents to start experimenting with rewards and incentives even if they had doubts about their impact. It was critical for interventionists to encourage participants to practice these skills prior to parents making a determination whether to adopt them or not in their everyday parenting practices. For many participants who were skeptical in the initial sessions about the impact of these practices, they gradually reported important improvements of their children's behaviors as they implemented the PMTO practices. Parents also reported how emotionally rewarding it was for them not having to quarrel with their children over compliance of specific tasks, as well as witnessing their children's enthusiasm for receiving consistent rewards for appropriate behavior (Author, 2015a).

We followed the PMTO model wherein a collaborative stance with parents is critical; interventionists do not confront parents with their deficiencies at any point in time. Instead, we highlighted the risks of certain parenting practices (e.g., spanking), described the benefits of alternative practices (e.g., implementing reward systems), and promoted active coaching of new parenting skills. As a result, we have consistently witnessed how even parents who relied on harsh practices, gradually experienced an important shift in their preferred parenting practices and adopted a more nurturing parenting approach (Author, 2015a).

The major impact of these components can be summarized as follows. First, parents tend to report a change in perception after becoming aware of how critical is for them to actively focus on promoting positive involvement with their children. One parent's reflection summarized a reaction commonly shared by parents, “I was the one who had to change, rather than expecting my child to change. Before, my son would approach me and I would evade him. Now, he approaches me and I express my love to him” (Author, 2015a, p. 7). With regards to encouragement, parents also recognized the importance of promoting children's compliance by relying on parental encouragement. The following statement by one participant captured an insight commonly shared by participants:

I was not close to my children and would not ask for things with good manners. I'd only yell at them, ‘Do this!’ I learned that one thing is respect and another fear. They were afraid of me. I am much closer to them now (Author, 2015a, p. 9).

Similar quotes are presented to parents in the CAPAS-enhanced intervention to describe the process of change reported by parents as they were exposed to this parenting component.

Limit setting

The transition to limit setting skills is generally smooth as improving discipline was frequently the primary reason families enrolled in the parenting program. We concur with researchers who affirm that establishing a strong foundation with positive involvement and encouragement is critical for any type of parenting intervention being delivered to populations from various backgrounds. The quality of the parent-child relationship is primarily influenced by a strong focus on positive involvement and nurturance, rather than an emphasis of punitive parenting (Patterson & Yoerger, 2002).

Overall, it is our experience that parents were highly motivated to engage in limit setting strategies that were effective, mild, and protective of children. We framed limit-setting practices by reflecting on the cultural value of respeto (i.e., respect), which highlights the importance of appropriate deference in social interactions. This cultural framing strongly resonates with parents as several studies have consistently documented the many ways in which Latino/a parents strive to instill in their children a deep appreciation for the value of respeto in family relations (Falicov, 2014).

A key component of parents’ success with effective limit setting is their ability to maintain their emotions regulated. Thus, we coached parents on basic emotion regulation techniques such as regulated breathing and control of negative internal thought processes (e.g., “my kid is just relentless”). We also practiced time-limited and mild behavioral techniques such as brief time outs or privilege removal as consequences for misbehavior (e.g., not allowing children for one evening to watch their favorite TV show).

Participants have consistently expressed satisfaction for being able to practice mild but effective limit setting practices (Author, 2015a). In the CAPAS-enhanced intervention, we provided illustrative quotes of parents’ reflections on their mastery of enhanced limit setting that was consistent with cultural expectations for promoting respeto among children. One parent in the enhanced intervention provided a reflection that echoed common reactions shared by participants in our groups:

The way I was educating my children was wrong. It's the behaviors you learned as a kid and the domestic violence and hitting that you experienced with your parents ... I have tried very hard not to spank my kids, but you grow up with how your parents treated you. I learned about discipline here and I will offer my kids something that is much better ... I'm learning how to control myself now. It's hard but I'm changing. (Author, 2012, p. 67)

Monitoring and supervision

Parental monitoring and supervision tend to be highly valued among Latinos/as because these parenting skills are aimed at protecting children, as well as enhancing quality of family relations (Falicov, 2014). In addition, these practices can strengthen a bonding relationship with other parents if families collaborate on monitoring practices. For example, parents can exchange information about safe play areas in the neighborhood and presence of foreigners who may pose a risk to children (e.g., drug sellers targeting children and youth). A promotion of a strong sense of community is a cultural value that has been reported as highly desirable by various Latino/a immigrant populations and other diverse populations exposed to historical oppression and discrimination (Falicov, 2014).

In our experience with Latino/a families, monitoring and supervision constitutes a skill that parents highly value and are committed to implement on a daily basis. In the CAPAS-enhanced intervention, parents were presented with qualitative quotes of parents reflecting about the benefits of this parenting skill, as one mother expressed, “Now, I am checking on my kid every half an hour. I'm always asking myself, ‘Where are they?’ ‘Who are they with?’ ‘What are they doing?’ I learned that I need to supervise them at all times” (Author, 2015a, p.9).

After discussing many potential monitoring situations, parents in our groups have reported lack of consistent supervision of situations that may constitute a risk for child sexual abuse. For example, parents have commonly reported not supervising children's play with older friends or adult neighbors, as they are “known to the family.” Thus, we have enhanced this parenting component by promoting conversations focused on the nature of child sexual abuse, including the fact that the majority of child sexual abusers are known to the victims (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Additional areas that parents have commonly identified in need of additional support refer to supervisory skills related to technology, and monitoring situations that constitute a challenge to parents due to language barriers, such as not being able to effectively supervise their children's behavior at school due to limited access to bilingual staff.

Family problem solving

Family problem solving is a component that provides families with new skills to help them address family challenges by integrating feedback from all family members (DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2004). We have learned that it is particularly important to remain attentive to two issues when introducing parents to this parenting skill. First, because families are exposed to considerable stressors, it is important for them to start practicing problem solving skills by focusing on mild problems (e.g., organizing a family fun time). Otherwise, if parents choose a contentious family conflict, the risk for harm is high given that focusing on an intense problem without coaching can result in increased family conflict. In addition, there is a need to ensure active involvement of all family members in family problem solving.

Based on consistent reports by parents, we have framed this component according to the value of familismo (Author, 2012). Specifically, parents have reported how this parenting skill promotes family cohesion as all family members are expected to be involved in the process of problem solving. In the CAPAS-enhanced group, we introduced this component by reflecting on how past participants have used problem solving skills to promote family cohesion, as one mother affirmed, “This is a very useful tool because we let children know that their opinion matters and that they are important when we make decisions as a family. This promotes family unity a lot” (Author, 2015a, p. 10). Based on the impact on family cohesion as reported by participants, we consider that family problem solving has the potential to have similar effects when implemented with additional diverse groups, particularly if cultural values and traditions of target populations emphasize the importance of family cohesion.

Advocacy Approach

The high rates of engagement and retention in our parenting groups were strongly influenced by the active advocacy component that began with recruitment activities and extended throughout the implementation of the parenting intervention. Specifically, an individual assessment at the beginning of each parenting cohort helped us identify which type of advocacy support each family needed. The resources requested from families usually ranged from access to food banks and referrals to culturally sensitive immigration services, to repatriation of human remains for families who desired to bury a deceased family member in their country of origin. The roles of clinical social workers and the community organizer in our team were essential as these professionals managed advocacy tasks and a variety of clinical crises that were beyond the scope of the parenting program (e.g., domestic violence). We believe that an active advocacy approach should be a central component of parenting interventions targeting underserved ethnic minority populations exposed to considerable contextual adversity. Otherwise, the challenges experienced by these families may prevent them from engaging in non-mandatory parenting programs due to the prominence that coping with adversity is likely to have in their lives.

Culture-specific Components (CAPAS-enhanced intervention)

According to qualitative and quantitative data from our prevention study, parents exposed to the CAPAS-enhanced intervention reported high satisfaction with the culture-specific components (Author, 2015a). The opportunity to reflect on how their parenting practices were influenced by issues of immigration and biculturalism offered parents an additional cultural grounding of their parenting skills. Specifically, participants reflected on the importance of discussing common challenges such as experiencing prejudice and discrimination in various contexts, lacking basic services and health insurance, and having limited access to culturally relevant mental health services. In addition, parents reported the importance of addressing culture-specific challenges such as learning how to become a bicultural family.

These findings correspond with the content and approach of efficacious interventions that have documented the relevance of addressing the ways in which immigration and biculturalism influence parenting experiences (Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2005; Smokowski et al., 2008; Martinez, 2006). A quote from a Mexican-origin parent illustrates this issue:

I thought that my children were going to grow and think like I do. But then I realized that they are growing up here. Their minds are different. If I only teach them what I learned in Mexico, I will not offer them a good education. I need to learn how to raise them in a new way by also adapting to this culture (Author, 2015a, p. 13)

Conclusion

Social work practice is rooted in a strong commitment to social justice and service to the most underprivileged populations. A key alternative to enhancing the lives of underserved and diverse families in the US refers to facilitating their access to efficacious and culturally relevant parenting interventions. Thus, it is imperative for clinical social workers and mental health professionals to have a clear understanding of the process of change that parents experience as they enhance their parenting skills and incorporate new practices. Ultimately, the ability to grow in the midst of adversity is about embracing existing strengths and nurturing the human experience that impacts everyone involved in the journey.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number R34MH087678 from the National Institute of Mental Health and Award Number 1K01DA036747 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health. Supplementary funding was provided by the MSU Office of the Vice-President for Research and Graduate Studies (OVPRGS), the MSU College of Social Science, and the MSU Department of Health and Human Development. We would like to express our deep gratitude to Marion Forgatch, ISII Executive Director and Laura Rains, ISII Director of Implementation and Training, for their resolved and continuous support as we have engaged in dissemination efforts with underserved populations in the U.S.

Footnotes

Dr. Parra-Cardona's clinical experience has included the provision of services to Mexican children living in the streets, child and adult victims of sexual abuse and violence, federal adult probationers convicted for drug trafficking, low-income Latino parents, Latino youth involved in the U.S. justice system, and perpetrators of intimate partner violence.

Contributor Information

J. Rubén Parra-Cardona, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University (MSU)..

Gabriela López Zerón, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University (MSU)..

Monica Villa, Holy Redeemer Church (Address: 1721 Junction St., Detroit, Michigan, 48209)..

Efraín Zamudio, Holy Redeemer Church (Address: 1721 Junction St., Detroit, Michigan, 48209)..

Ana Rocío Escobar-Chew, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University (MSU)..

Melanie M. Domenech Rodríguez, Utah State University.

References

- 2009. Author.

- 2012. Author.

- 2015a. Author.

- 2015b. Author.

- Baker CN, Arnold DH, Meagher S. Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science. 2011;12:126–138. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Domenech Rodriguez MM. Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence- based practice with diverse populations. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Amador Buenabad NG, Forgatch MS, Parra-Cardona JR. Parent Management Training-Oregon model in Mexico City. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21:32–47. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12059. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Sáenz-Santiago E. Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:121–132. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20096. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33(2):157–174. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20046. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Putting problem solving to the test: Replicating experimental interventions for preventing youngsters’ problem behaviors. R. D. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Conger FO, Lorenz, Wickrama KAS, editors. Continuity and change in family relations. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: pp. 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, Schwartz AL. Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Martínez LM, Padilla MB, Caldwell CH, Schulz AJ. Examining the influence of family environments on youth violence: A Comparison of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, non-Latino Black, and non-Latino White adolescents. Journal of Youthand Adolescence. 2011;40:1039–1051. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9624-4. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Latino Families in Therapy. 2nd ed. The Guildford Press; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Faust JR. Clinical social worker as patient advocate in a community mental health center. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2008;36:293–300. Doi: 10.1007/s10615-007-0118-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fong R, Pomeroy E. Translating research to practice. Guest Editorial. Social Work. 2011;56:5–7. doi: 10.1093/sw/56.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon divorce study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller HR, Gitterman A, editors. Mental health and social problems: A social work perspective. Routlege; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children's mental health: Low-income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74(1):189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleran Steiker LK. Making Drug and Alcohol Prevention Relevant: Adapting evidence-based curricula to unique adolescent cultures. Family & Community Health. 2008;31(1S):S52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000304018.13255.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Booth JM. Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Research on Social Work Practice, Advanced online publication. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1049731514535989. doi: 10.1177/1049731514535989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR. Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations. 2006;55(3):306–317. doi: 0.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00404. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin AM. Social Work's legacy: Irreconcilable differences? Clinical Social Work Journal. 2002;30:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. The Guildford Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabito DM. Educating a new generation of social workers: Challenges and skills needed for contemporary agency-based practice. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2012;40:245–254. doi: 10.1007/s10615-011-0378-6. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo FF. Ethnoracial gap in clinical practice with Latinos. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2009;37:277–286. 10.1007/s10615-009-0241-1. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA. Commentary: Cultural adaptation, collaboration, and exchange. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:544–546. doi: 10.1177/1049731510366145. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Yoerger K. A developmental model for early-and late-onset of delinquency. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder JJ, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose R, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations. 2008;57(3):295–308. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Preventing Child Sexual Abuse. Washington, D.C.: 2010. [March 4, 2016]. from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/programs/sexualabuse/ [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Strengthening Family Resilience. 3rd ed. The Guildford Press; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Mitchell C, Hyde LW, Monk CS. Identifying early pathways of risk and resilience: The Ecodevelopment of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and the role of harsh parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S0954579414001412. Advanced online publication. doi:10.1017/S0954579414001412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Bradlee M. Exiling children, creating orphans: When immigration policies hurt citizens. Social Work. 2014;59:167–175. doi: 10.1093/sw/swu004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]