ABSTRACT

Human adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) have been shown to differentiate into mature adipocytes and to play an important role in creating the vasculature, necessary for white adipose tissue to function. To study the stimulatory capacity of ASC on endothelial progenitor cells we used a commercially available co-culture system (V2a – assay). ASC, isolated from lipoaspirates of 18 healthy patients, were co-cultured for 13 d on endothelial progenitor cells. Using anti CD31 immunostaining, cells that had undergone endothelial differentiation were quantified after the defined co-cultivation period. Endothelial cell differentiation was observed and demonstrated by an increase in area covered by CD31+ cells compared with less to no endothelial cell differentiation in negative and media-only controls. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in supernatant medium collected during the co-cultivation period revealed elevated VEGF levels in the co-culture samples as compared with ASC cultures alone, whereas no increase in adiponectin was detected by ELISA. These findings help to provide further insights in the complex interplay of adipose derived cells and endothelial cells and to better understand the diversity of ASCs in respect of their stimulatory capacity to promote angiogenesis in vitro.

KEYWORDS: adipose stem cell, angiogenesis, cell-cell interaction, endothelial cell, vasculogenesis

Introduction

White adipose tissue (WAT) has long been recognized as being more than a mere organ of energy storage, as it also has a large number of endocrine functions whose complex interactions have to date not been fully understood. However, WAT is known to have a dense vascular network where every mature adipocyte is in direct contact with at least one capillary in an arrangement that is necessary for physiologic WAT functioning.1 Furthermore, interactions between endothelial cells (EC) and both adipocytes and adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) are crucial for the maintenance of physiologic WAT.2,3 The stromal vascular fraction (SVF) is the anatomic compartment where progenitor cells for both adipocytes and endothelial cells are located. The term SVF is commonly used in the literature and refers to the cellular pellet without fat cells (i.e., mature adipocytes). This fraction can be obtained through an isolation process that uses collagenase secondary to liposuction (i.e., fat harvesting), resulting in a component that contains multiple cells: preadipocytes, endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, cells of the hematopoetic cell lineage and adipose-derived stem/stromal cells (ASCs).4,5 Since their discovery by Zuk and coworkers in 2001, ASC have proven to display multilineage differentiation capabilities such as adipogenic lineage, osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic, and neurogenic lineages, both in vitro and in vivo4-8 and have also been found to be involved in the angiogenesis in WAT during times of WAT expansion and during general WAT remodelling and maintenance.9 Animal experiments have indicated that certain cells within the SVF are recycled pre-existing blood EC when creating new vasculature.9 Some experiments successfully demonstrated that ASC are able directly to differentiate into ECs in vitro and in vivo after prior cultivation.9 Recent research further suggests that the addition or implantation of ASC into wounds or models of ischemia in vivo can significantly improve healing or survival of the lesion-affected tissue.10 These in vivo studies, although providing insights into the complex process of wound healing, were performed on inflamed and hypoxic environments. However, the presence of inflammation and lesion-associated hypoxia, which would invariably trigger the activation or release of pro-inflammatory factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), might represent a shortcoming of these experiments. Inflammatory cytokines not only exhibit indirect pro-angiogenic properties but might also trigger angiogenic responses different from the angiogenic behavior of ASC under non-stress conditions. The secretion of inflammatory cytokines has been linked to the increased release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which has been recognized as the most important proangiogenic factor in WAT.11-14 Thus, pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic factors might stimulate the SVF cells or ASC to respond to a lesion that manifests itself by an increased oxygen demand, as these cells are also the drivers of WAT vasculogenesis under physiologic conditions.14,15

The commercially available V2a Kit allows all aspects of angiogenesis and endothelial cell differentiation to be observed in an in-vitro model, i.e., without the addition of pro- or anti-angiogenic agents. Thus, the co-culturing of isolated ASC with the endothelial progenitor cells contained in the V2a-Kit should allow the observation of the possible intrinsic angiogenic behavior of ASC in contact with endothelial progenitor cells, enabling us to focus on the interactions of these 2 cell-types alone and to compare their individual angiogenic potential. These findings are not presented in the literature so far and help us to better understand the cell-cell interactions for further in vivo studies concerning the vascularisation of Tissue Engineered ASCs.

Results

Characterization of adipose derived stem cells

To fulfil the consensus criteria outlined by Dominici and Zuk for defining adipogenic progenitor cells as adipose derived stem cells (ASCs), cells were as induced by an osteogenic and an adipogenic differentiation regimen. The reagents used were commercially available - ready to use - lineage specific differentiation media from Promocell.

Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation

During the process of adipogenic differentiation, cells undergo a phase of growth arrest, which is induced by components of the induction medium. During the growth phase, immature adipocytes are morphologically similar to fibroblasts. After inducing the differentiation, the cells take on a spheric shape, accumulate lipid droplets, and progressively acquire the morphological and biochemical characteristics of mature white adipocytes. Oil-Red O staining could proof the adipogenic potential of the ASCs by staining intracellular lipid droplets. As shown in Figure 1a, a significant fraction of cells contained multiple intracellular lipid-filled droplets that accumulated Oil Red –O as a proof for adipogenic differentiation.

Figure 1.

Representative light microscopy pictures of adipogenically and osteogenically differentiated ASCs (10xmagnification) a) intracellular oil red stained lipid droplets at day 7 post induction of differentiation. b) Extracellular calcium deposits stained with alizarin red as marker for osteogenic differentiation on day 24 of differentiation c) Undifferentiated cells.

Induction of osteogenesis leads to the process of mineralization and the induced Osteoblasts produce extracellular calcium deposits in vitro. Those deposits can specifically be stained with Alizarin Red S and proof the successful in vitro bone formation (Fig. 1 b).

Immunfluorescence staining

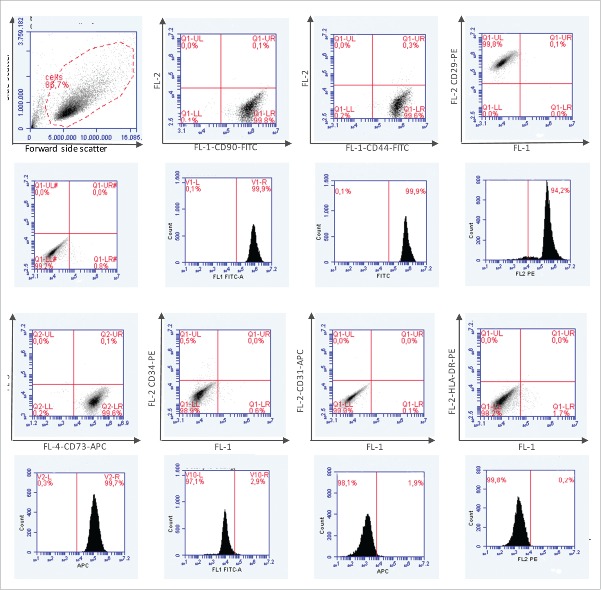

In addition, phenotypic analysis of ASCs was performed by immunofluorescence staining of markers established for mesenchymal stem cells and adipose derived stem cells respectively. To confirm lineage specificity cells were also stained with antibodies directed against the endothelial cell marker CD31, the myelomonocytic specific antigen CD14 and MHC-class II. All ASC population measured (n = 4) were highly positive for the mesenchymal stem cell markers CD44, CD90, CD73 and CD29 and negative for CD31, CD14 and MHC-class II. Figure 2 shows the Dotplots (first row) and the histograms of the respective markers (second row). Figure 3 shows the percentage of cell surface expression of 4 mesenchymal stem cell markers (a) and the mean values of 5 representative experiments (b).

Figure 2.

Phenotypic analysis of ASCs by immunfluorescence staining of markers established for mesenchymal stem cells and adipose derived stem cells (CD44, CD90, CD73 and CD 29). Confirmation of lineage specificity by antibody staining against CD31, CD14 and MHC-class II.

Figure 3.

a) Percentage of Cell surface expression of 4 mesenchymal stem cell markers in addition to lineage specific markers on ASCs (n = 5) cultivated in ECGM-Media at P1 until confluence and evaluated by flow cytometry. b) Mean values and standard deviation of 5 representative experiments.

Co-culturing of V2a-cells with ASC induces inter-individually varying endothelial differentiation of V2a-cells

To quantify the extent of endothelial differentiation, anti-CD31 immunostaining was used in addition to visual inspection. The percentage of the total well surface area covered by CD31+ cells was quantified by using the Image J software. We applied a color threshold to determine the percentage of successfully stained, i.e., CD 31+ cells, as a percentage of total well area. Samples were analyzed in duplicates or triplicates with respective amounts of endothelial differentiation in one set of samples usually being comparable.

Notably, a marked increase occurred in differentiated endothelial CD31+ cells in wells in which V2a cells had been co-cultured with ASC, with the extent of endothelial differentiation varying between individual samples, while in medium-only or suramin / negative-control wells, endothelial differentiation was distinctly lower (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Boxplot showing areas covered by samples, VEGF positive control, and medium only and negative controls. The difference between samples and non-positive control was statistically significant (p < 0, 05).

Co-cultures generally appeared strikingly different from the controls, with a higher extent of CD31+ cells and large branching networks of CD31+ cells. Additionally, samples with high levels of EC differentiation often exhibited a less well defined structure than samples with less absolute EC-differentiation, where tubuli formation was more delicate and organized. We observed that the level of organization of the cells varied, from highly organized, branching networks to more diffuse or randomly staining patterns; several variants were seen (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

(see previous page). Different differentiation patterns of V2a-cells ASC co-cultures. Left: View of entire well after anti-CD31 immunostaining with CD31-positive cells stained dark blue/violet. Middle: Native picture (enlarged from left image, compare yellow rectangle) of the area used for quantitative analysis. Right: 8-bit image created by ImageJ in final quantitative analysis step; the dark area was measured as a percentage of total image area. A, B, and C were co-culture wells with ASC from 3 different patients. D was a representative positive control well with VEGF added to medium. E was medium-only control. F was a negative-control well with Suramin added to medium. Differences in the differentiation patterns both between samples A-C and between samples and controls are obvious. Furthermore, the similar appearance of medium-only (E) and negative control (F) is clear. Percentages of area covered by CD31+ cells: A 43.2%, B 12.7%, C 34.0%, D 23.2%, E 6.4%, F 5,7%.

Compared with the samples, the positive control wells also exhibited networks of CD31-positive cells but these were more delicate. In negative and media-only controls, no organized tubule formation was visible and the percentage of area covered by CD31+ cells was comparatively low. This further served to show that the standard medium, which was also used for the co-culture wells, had no intrinsic pro-angiogenic properties, despite evoking the secretion of VEGF (20pg/ml VEGF in medium-only controls on day 6, 129pg/ml VEGF on day 12 of co-culture).

VEGF levels are elevated during cultivation but actual levels vary inter-individually

To monitor the progress of V2a-cell differentiation, VEGF ELISA was performed. Since medium was changed every other day, the native VEGF concentration measured reflected 2 d of VEGF secretion by the cells. In co-culture wells, VEGF was present in all samples, again with inter-individual variance as some samples exhibited VEGF peaks, whereas others remained static or linearly increasing VEGF secretion rates (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

VEGF levels of 5 representative samples in ng/ml over the course of 12 day cocultivation period.

Compared with the VEGF level of the positive control, the VEGF levels in the samples were generally lower. However, in some samples, endothelial differentiation was comparable with the low levels observed in the positive control. Notably, VEGF was measurable in all wells, including neutral medium-only wells, to which no ASC had been added, and negative control wells, in which V2a cells were cultured in the presence of the anti-angiogenic agent Suramin.

VEGF levels do not correspond with the degree of endothelial differentiation

In the next step of our analysis, we compared the calculated percentage of well surface area covered by CD31+ cells to the VEGF concentration in medium that had been conditioned by the cells for 2 d. VEGF levels were determined in triplicate by using ELISA and were found to be present during the entire course of cultivation, indicating a steady VEGF secretion over time (see above). When the mean surface area was plotted against the mean VEGF concentration over the entire cultivation period calculated for each sample, no correlation was seen (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Mean VEGF levels during the co-cultivation period blotted against percentage of well surface covered by CD31+ cells. No correlation could be found.

As mentioned above, VEGF was also measurable in control wells, including the negative control, and in 2 of the 18 co-cultures in which only minimal endothelial differentiation could be detected. Averaged VEGF levels in cultures that did not exhibit significant endothelial differentiation and tubule formation were no lower than those in cultures with higher endothelial differentiation.

Adipogenic differentiation was not detectable

To investigate the possible adipogenic differentiation of ASC, an adiponectin ELISA on media supernatants was performed, in addition to visual inspection, where no lipid droplet formation within the cells was observed, Adiponectin was not detectable during the entire co-cultivation period, confirming the absence of adipogenic stimuli and adipogenic differentiation of ASC.

Discussion

Besides numerous models of angiogenesis established in vivo in the literature (such as the chick chorioallantoic membrane assay16 or the rabbit cornea model17), the setting in an animal model invariably brings external, uncontrollable, and possibly confounding factors into an experiment. Potential distortions of measurements and the effort of performing an in-vivo trial led us to the conclusion that to us such an approach was both undesirable and impractical. In contrast, an in-vitro approach using the V2a assay appeared more feasible to us, in addition to being more cost effective and easier to conduct. It allowed a standardised procedure to be performed and, thus, a reliable quantification of possible differences in EC differentiation. Our results confirmed that an intrinsic angiogenic response or crosstalk could be provoked solely by co-culturing ASC with endothelial progenitor cells. This was interesting, since neither hypoxia nor nutritional stress were present at any time-point during the culturing of the ASC before their addition to the pre-cultured V2a-cells or during the actual co-cultivating process. With respect to the differences observed regarding the general aspect of co-culture samples compared with each other and with controls, we propose that coordinated expansion of endothelial progenitor cells might have been prevented by fast adipose derived stem cells expanding at various rates. Consequently, relatively slower ASC expansion rates would have allowed an undisturbed growth of endothelial progenitor cells causing a smoother macroscopical aspect. The multipotency of the applied ASCs was determined according to the consensus criteria for mesenchymal stem cells18-20 by analysis of distinct surface markers in flow cytometry and analysis of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation with Oil Red and alizarin red staining, respectively. The mineralization and the increase in osteonectin, osteopontin and collagen type I protein expression is well characterized by Hutmacher et al in the literature.21 The high presence of mesenchymal stem cell markers such as CD44, CD90, CD73 and CD29 and the absence of cell markers such as the endothelial cell specific protein CD31, the myelomonocytic specific antigen CD14 and MHC-class II, as assessed by flow cytometry, clearly demonstrated the purity of the cell populations used.

As a fringed aspect of CD31+ cell networks were often correlated with a high rate of endothelial differentiation, ASC might also have transformed into EC during the co-cultivation period of 13 d. Obviously, this experiment does not clarify whether the markedly increased VEGF levels are a result of ASC secretion, V2a-cell secretion or both, although we can confirm that human ASC stimulate angiogenesis in vitro even without specific external pro-angiogenic stimuli. Since VEGF levels did not correlate with EC differentiation or tubule formation, VEGF does not seem to be the main promoter of angiogenic differentiation and cell-cell interactions in this setting. VEGF has been shown by us and others20,22 to be secreted by undifferentiated ASCs and levels increase during induction of adipogenesis. However, in our experimental approach we were not able to differentiate the level of VEGF secreted by ASC or by the endothelial cells. Vascularization could only be detected by elevated expression of CD31, which was clearly mediated by the endothelial cells as ASCs did not express CD31 in FACS-analysis. Interestingly, the amount of angiogenesis varies greatly between individual samples but we can only speculate on possible reasons for this. Studies indicate that widespread diseases such as metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes or morbid obesity, which are known to manifest themselves as pathologies of WAT, might affect ASC on a fundamental level. Also, maternal obesity was shown to cause epigenetic changes in the gene expression of the adipose tissue of their offspring and findings in obese patients show histone methylation patterns that deviate from those of a lean control group.23,24 In metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, WAT has been shown to enter a state of chronic low-grade inflammation, marked by a change of WAT-resident macrophages from the “anti-inflammatory” M2 type to the “pro-inflammatory” M1 type and by the immigration of circulating M1 macrophages and elevated activation levels of NK-cells, all of which lead to the remodelling of WAT extracellular matrix into a more rigid type and to a higher cell turnover.25 This, in turn leads to hypoxia through the increased distance between the capillaries and adipocytes, whereas neo angiogenesis is concomitantly impaired by the aforementioned more rigid extracellular matrix structure, eventually leading to a self-maintaining vicious circle of chronic inflammation, hypoxia, adipose tissue fibrosis and curbed neoangiogenesis.26 Sustained inflammation might in turn eventually evoke epigenetic changes in ASC populations leading to the altered behavior of these cells even under non-hypoxic, nutritionally optimal conditions as in our experiment. Prolonged inflammatory states have previously been shown to induce epigenetic changes in cells.27,28 One can also hypothesize that, since ASC are subjected to stress and hypoxia during the liposuction process, which has been shown to impair their viability, even the surviving cells might be permanently damaged, resulting in altered behavior through epigenetic changes.29 The demonstration as early as 2004 that ASC secrete VEGF spontaneously and that creating hypoxic conditions enhances their VEGF release does not suffice to explain the differences in EC differentiation observed, as cultivation took place under non-hypoxic/non-inflamed conditions.13 Obviously, these proposed mechanisms might have interacted. Whatever the reason for the variable endothelial differentiation, VEGF secretion by either ASC or V2a only appears to be remotely correlated with it. Additionally, VEGF is present when, as demonstrated with assays performed on controls, endothelial differentiation is random and minimal, implying that the VEGF release by undifferentiated endothelial cells fails to cause endothelial differentiation. With Suramin being a highly potent inhibitor of angiogenesis,30 the absence of EC differentiation is obviously expected, but the presence of elevated VEGF level in the media-only control group in combination with the equally low level of EC differentiation compared with the negative control group is surprising.31 As VEGF is also a survival factor for EC and their progenitor cells, the measured levels might represent a baseline value that is necessary for survival but not sufficient for differentiation.32

We conclude that, while further and more detailed research will be necessary to clarify the causes of our findings, ASC do exhibit an inter-individually varying degree of activity in standardized environments. These differences may contribute to the frequently reported problem of unpredictable resorption rates of the transplant after autologous transplantation of adipose tissue and deeper insight into the mechanisms behind this behavior may eventually allow more predictable outcomes when soft tissue defects are treated using adipose tissue with its otherwise very favorable properties (readily available and easily obtainable, autologous nature, malleable, and re-growing) as a filler.33

Materials and methods

Isolation of ASC from female patients

ASC were isolated from lipoaspirates from the abdominal region of 18 healthy female patients (age range 40y–70y, median 55y, mean 53.1y) undergoing aesthetic liposuctions at the Clinic for Plastic Surgery at the Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Germany. All research has been approved by the authors' ethic committee of the Technical University of Munich, and all clinical investigations have been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their written consent, which was approved by the ethic committee of the Technical University of Munich (Permit Number: 5623/12). Aliquots of 10 ml lipoaspirate from each patient were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 with a collagenase solution at a final concentration of 0.2U/ml (collagenase NB4; Serva Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany) dissolved in collagenase buffer prepared by our in-house pharmacy: 23.8 g/l HEPES (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 7 g/l NaCl Ph.Eur, 3.6 gl KCl Ph.Eur, 0.15 g/l CaCl2.2H2O Ph.Eur, 1 g/l D-glucose Ph.Eur in distilled water, supplemented with 1.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany)). Samples were incubated in a water bath for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle agitation. The digestion was stopped by adding twice the volume of DMEM + 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). After fractionation of the mixture by sedimentation centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 20°C, the upper layer was removed and the cells from the cell pellet were aspirated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and filtered through a 70-µm mesh cell strainer by BD Bioscience (California, USA) to remove debris. This cleaning step was then repeated. Following the second wash step, PBS was removed, the pellet was resuspended with 20ml DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, 12634) supplemented with 15 mM Hepes (Merck, 391340), NaHCO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, 88975), pyridoxine (Sigma-Aldrich, P9755) and 0.365 g/l L-Glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, G6392), Insulin (8 mM/ (10 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, I3536), 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Invitrogen, 15240–096), 10 mg/ml apo-transferrin (Sigma, T1428), 33 mM biotin (Sigma-Aldrich, B4639), 17 mM D-pantothenic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, P5155), and 10% FBS (Invitrogen, 10270) and seeded into 75-cm2 flasks without the cells being counted. After 24 hours, the medium was removed and the flask was carefully washed with pre-warmed PBS to remove erythrocytes, debris and non-adherent cells. Fresh ECGM (20 ml) was added or renewed every 3–4 days, if necessary.

After reaching confluence at >75%, cells were harvested by trypsinisation (0.05% trypsin in EDTA; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Following a wash with PBS, cells were counted by using disposable haemocytometers (C-Chip disposable haemocytometer, Biochrom, Merk Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and trypan blue (trypan blue 0,4%, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) exclusion. All cells were used after the first passage and were cryopreserved in dimethylsulphoxide-free biofreeze solution (Biochrom, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and prepared for long-term storage in liquid nitrogen.

Proof of multipotency and stem cell characteristics of the ASCs

Adipocyte differentiation

To induce adipocyte differentiation, basal medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS before the addition of an induction medium based on a-MEM (Minimum Essential Medium Eagle, Sigma-Aldrich, M 2279) and supplemented with 5% FBS (Invitrogen, 10270), 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Invitrogen, 15240–096), Insulin 16 mM (10 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, I3536), 0.1 mM Hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich, H0888), 0.5 mM IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine) (Sigma-Aldrich, I7018), 60 mM Indomethacin (Sigma-Aldich, I8280). After 48 hours, induction medium was replaced with a differentiation medium (a-MEM (Minimum Essential Medium Eagle, Sigma-Aldrich, M 2279) supplemented with 5% FBS (Invitrogen, 10270), 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Invitro- gen, 15240–096), Insulin 16 mM (10 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, I3536). Differentiating cultures were kept for 14 d with differentiation medium being changed every 3 d. The cells were monitored by light microscopy for lipid droplet formation and finally stained with oil-red to confirm differentiation.

Oil Red-O staining

Medium was completely removed from tissue culture plates, and plates were rinsed with PBS After removal of PBS, 10 ml of 10% formalin (in house pharmacy preparation) solution was added, and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Formalin was removed from each plate. Subsequently, each plate was gently rinsed with 5 ml purified water followed by the addition of 5 ml 60% isopropanol (in house pharmacy preparation) for 5 minutes before being discarded. Aliquots of 6 ml of oil-red O (0.5% in isopropanol (isopropyl alcohol) (Sigma-Aldrich, O1391) working solution was added to cover the entire monolayer. The plates were then incubated for 2 hours in the refrigerator at 4_C before the Oil-red O solution was discarded. In a last step, the cultures were washed several times with PBS. Cells were finally monitored for lipid droplet formation by using an inverted optical microscope.

Osteoblast differentiation (Detection of Calcium deposits)

ASCs were plated at a concentration of 1×105 cells into 24 well plates in duplicates using ECGM Media. After reaching confluency the media was replaced by MSC Osteogenic Differentiation Media (Promocell). Cells were incubated for 21 to 28 d and changes of media were performed every third day. After this time period cells were submitted to a standard Alizarin red staining protocol.

After removal of tissue culture medium, cells were washed with PBS. Then PBS-buffered formalin was added and cells were incubated for 30 minutes. After removal of the formalin, cells were carefully washed with distilled water and subsequently stained with Alizarin Red S solution (Alizarin Red S (C. I. 58005), 2%, pH to 4.1–4.3) for 45 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After aspiration of the staining solution, cells were thoroughly washed with distilled water and subsequently analyzed for mineralized osteoblasts (with extracellular calcium deposits) appearing in bright orange to red using an inverted optical microscope with a phase-contrast unit.

Phenotypic analysis of ASCs cultured in ECGM Media

ASCs expanded to passage 2 were examined for surface marker expression using flow cytometry. The following mouse- anti-human monoclonal antibodies conjugated to fluorochromes were used: CD90-FITC (clone 5E10, IgG1), CD44-FITC (clone MEM85 IgG2a), CD29-PE (clone MEM-101A, IgG1), CD73-APC (clone AD2, IgG1), CD31-APC (clone WM59, IgG1), CD34-PE (clone 4H11, IgG1), CD14-FITC (clone Tük4, IgG2a) (all from Life technologies GmbH, Darmstadt) and HLA-DR-PE (clone L243, IgG2a, Santa Cruz- Biotechnology, Inc. Heidelberg, Germany). Unstained cells were used as negative controls.

ASCs were harvested and brought into suspension. Cells were washed once with PBS. After centrifugation and removal of the PBS, the cell pellet was aspirated in 2 ml of FACS-buffer (PBS, supplemented with 2% FCS). Cells were counted and for each staining formulated to an amount of 100.000 cells in a volume of 100µl in 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Then 5 µl of specific antibodies was added to each sample. The tubes were gently vortexed and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. After the incubation period the cells were washed 2 times with PBS and after the final washing step the cells were aspirated in 500 µl of FACS buffer and subsequently analyzed with BD FACS-Accuri cell analyzer and Accuri Software.

Co-culturing of V2a-endothelial cells with ASC

The V2a Vasculogenesis to Angiogenesis Kit® (TCS Cellworks, Buckingham, United Kingdom) included primary EC progenitor cells, seeding and growth media (with associated supplements), validated antibodies and reagents for tubule vizualization, validated positive control (VEGF) medium additive and validated negative control (Suramin) medium additive. A detailed description of all working steps was provided with the kit. The assay was performed following the manufacturer's guidelines, as explained here briefly. Cells were added to the growth medium on the second day instead of soluble additives or otherwise conditioned media as suggested in the protocol (the addition of cells for co-culture was not mentioned or suggested in the manufacturer's protocol).

On the first day, V2a seeding medium was pre-equilibrated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere and a CO2 content of 5%. Endothelial progenitor cells were thawed and added to a tube with seeding medium. Cells were thoroughly mixed, seeded into a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 hours before co-culture with ASC. After 24 hours (on the second day), ASC that had been pre-cultivated by using the above-mentioned protocol were harvested by trypsinisation and counted by using trypan blue staining and a disposable haemocytometer. Samples containing 1000 cells were transferred into 2-ml Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 2000 rpm on a micro-centrifuge. During the preparation of the samples, growth medium was prepared and equilibrated according to the manufacturer's protocol. Following centrifugation, supernatants were carefully removed and the cell pellets were aspirated in 500µl pre-equilibrated V2A growth medium. Endothelial progenitor cell seeding medium was discarded and replaced by 500µl growth medium with added ASC. On the first run, samples and controls were assayed in triplicate, whereas for the second and third runs, we decided to use duplicates (since the results of triplicate assays were comparable) to obtain a higher number of analyzed samples. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator (Heracell 150i; 37°C, 5% CO2, Thermo fisher scientific, Waltham, USA) for a total of 14 d with 13 d of co-cultivation. Growth and control medium was exchanged and collected every other day. The collected supernatants were immediately frozen at −20°C and used for later enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of VEGF and adiponectin.

After 14 d in culture, the experiment was terminated. To visualize tubule formation, cultures were fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol and subsequently stained with mouse-anti-human CD31 antibody (PECAM1) and BCIP/NBT substrate. Imaging was performed by using a Leica Microscope DMI 600B and Leica Software DFC 425 C Application Suite 357 (Wetzlar, Germany).

VEGF and adiponectin ELISA

Undifferentiated ASCs were seeded at a density of of 1×105 cells in 24 well plates and incubated to a confluency of 80%. Supernatants were collected and frozen in aliquots at −20°C until further use. To detect VEGF secretion by the co-cultures, supernatants were collected at every change of medium and immediately frozen at −20°C. Quantitative analysis of VEGF and adiponectin content was then performed by using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems human adiponectin or VEGF DuoSet ELISA development kit, Minneapolis, USA) with a standardised protocol. Following the manufacturer's protocol, samples were read at a wavelength of 450 nm by using a spectral photometer (Multiskan SC, Thermo scientific, Waltham, USA) [http://www.rndsystems.com/pdf/dy1065.pdf; http://www.rndsystems.com/pdf/dy293b.pdf; R&D Systems, Inc. 614 McKinley Place NE, Minneapolis, MN 55413, USA] VEGF and adiponectin were assayed undiluted. Data was analyzed using SPSS Software for standard boxplot, confidence intervals, and outlier calculation and drawing of diagrams.

Quantification of well surface area covered by CD31± cells by using Image J and Threshold_Color

Following anti-CD31 immunostaining (as described above), wells were photographed at 5x magnification by using the bright field mode of the Leica Microscope DMI 600B and Leica Software DFC 425 C Application Suite 357 to create a composite image of the entire well. In addition to visual analysis, the ImageJ program (open source, created by Wayne Rasband ( wayne@codon.nih.gov) at the Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health) with the Threshold_Color Plugin (open source, created by Gabriel Landini (G.L andini@bham.ac.uk), University of Birmingham, available at www.dentistry.bham.ac.uk/landinig/software/software.html) was used to quantify the percentage of darker shaded (CD31-positive) well surface area. A rectangular area (as representative and as large as possible) was selected from the native image and duplicated into a secondary image and, by using the Threshold Color Plugin (brightness threshold pass filter set to 125), a black and white picture was created from it with the to-be analyzed area remaining white. The picture was than color -inverted and converted into 8-bit format. A threshold was applied and the percentage of image area passing that threshold was analyzed and quantified by using the Analyze-Particles function of ImageJ.

Abbreviations

- ASC

adipose stem cell

- EC

endothelial cell

- HIF1-α

hypoxia inducible factor 1-α

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support by the Legerlotz foundation.

References

- [1].Cao Y. Adipose tissue angiogenesis as a therapeutic target for obesity and metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9:107-15; PMID:20118961; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd3055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jannson PA. Endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Intern Med 2007; 262:173-83; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Strassburg S, Nienhueser H, Stark GB, Finkenzeller G, Torio-Padron N. Human adipose-derived stem cells enhance the angiogenic potential of endothelial progenitor cells, but not of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2013; 19:166-74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alharbi Z, Almakadi S, Opländer C, Vogt M, Rennekampff HO, Pallua N, Intraoperative use of enriched collagen and elastin matrices with freshly isolated adipose-derived stem/stromal cells: a potential clinical approach for soft tissue reconstruction. 2014, BMC Surgery, 14:10; PMID:24555437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2482-14-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tholpady SS, Llull R, Ogle RC, Rubin JP, Futrell JW, Katz AJ: Adipose tissue: stem cells and beyond. Clin Plast Surg 2006, 33(1):55-62; PMID:16427974; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cps.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gupta A, Leong DT, Bai HF, Singh SB, Lm TC, Hutmacher DW. Osteo-Maturation of adipose-derived stem cells required the combined action of vitamin D3, beta-gylcerophophate, and ascorbic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 362:17-24; PMID:17692823; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rider DA, Dombrowski C, Sawyer AA, Ng GH, Leong D, Hutmacher DW, Nurcombe V, Cool SM. Autocrine fibroblast growth factor 2 increases the multipotentiality of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2008; 26:1598-608; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, Benhaim P, Lorenz HP, Hedrick MH. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng 2001; 7:211-28; PMID:11304456; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/107632701300062859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Planat-Benard V, Silvestre JS, Cousin B, André M, Nibbelink M, Tamarat R, Clergue M, Manneville C, Saillan-Barreau C, Duriez M, et al.. Plasticity of human adipose lineage cells toward endothelial cells: physiological and therapeutic perspectives. Circulation 2004; 109:656-63; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114522.38265.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Huang SP, Huang CH, Shyu JF, Lee HS, Chen SG, Chan JY, Huang SM. Promotion of wound healing using adipose-derived stem cells in radiation ulcer of a rat model. J Biomed Sci 2013; 20:51; PMID:23876213; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1423-0127-20-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Thematic review series: Adipocyte biology, adipocyte stress: the endoplasmic reticulum and metabolic disease. J Lipid Res 2007; 48:1905-14; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1194/jlr.R700007-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nakao S, Kuwano T, Ishibashi T, Kuwano M, Ono M. Synergistic effect of TNF-alpha in soluble VCAM-1-induced angiogenesis through alpha 4 integrins. J Immunol 2003; 170:5704-11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, Pell CL, Johnstone BH, Considine RV, March KL. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation 2004; 9:1292-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schenk S, Saberi M, Olefsky JM. Insulin sensitivity: modulation by nutrients and inflammation. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:2992-3002; PMID:18769626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI34260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Halberg N, Khan T, Trujillo ME, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Attie AD, Sherwani S, Wang ZV, Landskroner-Eiger S, Dineen S, Magalang UJ, et al.. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:4467-83; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.00192-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vu MT, Smith CF, Burger PC, Klintworth GK. An evaluation of methods to quantitate the chick chorioallantoic membrane assay in angiogenesis. Lab Invest 1985; 53:499-508; PMID:2413278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gimbrone MA, Leapman SB, Cotran RS, Folkman J. Tumor dormancy in vivo by prevention of neovascularization. J Exp Med 1972; 136:261-76; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.136.2.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop D, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006; 8:315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koellensperger E, Gramley F, Preisner F, Leimer U, Germann G, Dexheimer V. Alterations of gene expression and protein synthesis in co-cultured adipose tissue-derived stem cells and squamous cell-carcinoma cells: consequences for clinical applications. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014; 5:65; PMID:24887580; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/scrt454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mitchell J, McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, Floyd ZE, Kloster A, Di Halvorsen Y, Storms RW, Goh B, Kilroy G, et al.. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells 2006; 24:376-385; PMID:16322640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Leong DT, Abraham MC, Rath SN, Lim TC, Chew FT, Hutmacher DW. Investigating the effects of preinduction on human adipose-derived precursor cells in an athymic rat model. Differentiation 2006; 74:519-29; PMID:17177849; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA. Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine. Circ Res 2007; 100:1249-60; PMID:17495232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Attig L, Vigé A, Gabory A, Karimi M, Beauger A, Gross MS, Athias A, Gallou-Kabani C, Gambert P, Ekstrom TJ, et al.. Dietary alleviation of maternal obesity and diabetes: increased resistance to diet-induced obesity transcriptional and epigenetic signatures. PLoS One 2013; 8:e66816; PMID:23826145; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0066816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jufvas A, Sjödin S, Lundqvist K, Amin R, Vener AV, Strålfors P. Global differences in specific histone H3 methylation are associated with overweight and type 2 diabetes. Clin Epigenetics 2013; 5:15; PMID:24004477; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1868-7083-5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].O'Rourke RW, Gaston GD, Meyer KA, White AE, Marks DL. Adipose tissue NK cells manifest an activated phenotype in human obesity. Metabolism 2013; 62:1557-61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khan T, Muise ES, Iyengar P, Wang ZV, Chandalia M, Abate N, Zhang BB, Bonaldo P P., Chua S, Scherer PE. Metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue fibrosis: role of collagen VI. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:1575-91; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01300-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 2009; 139:693-706; PMID:19878981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stenvinkel P, Karimi M, Johansson S, Axelsson J, Suliman M, Lindholm B, Heimbürger O, Barany P, Alvestrand A, Nordfors L, et al.. Impact of inflammation on epigenetic DNA methylation – a novel risk factor for cardiovascular disease? J Intern Med 2007; 261:488-99; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01777.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Keck M, Zeyda M, Gollinger K, Burjak S, Kamolz LP, Frey M, Stulnig TM. Local anaesthetics have a major impact on viability of preadipocytes and their differentiation into adipocytes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126:1500-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8beb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Waltenberger J, Mayr U, Frank H, Hombach V. Suramin is a potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor. A contribution to the molecular basis of its antiangiogenc action. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1996; 28:1523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bahramsoltani M, Plendl J. Different ways to antiangiogenesis by angiostatin and suramin, and quantitation of angiostatin-induced antiangiogenesis. APMIS 2007; 115:30-46; PMID:17223849; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Saharinen P, Eklund L, Pulkki K, Bono P, Alitalo K. VEGF and angiopoietin signaling in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Trends Mol Med 2011; 17:347-62; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].de Blacam C, Momoh AO, Colakoglu S, Tobias AM, Lee BT. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and aesthetic results after autologous fat grafting for contour deformities of the reconstructed breast. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 128:411e-8e; PMID:22030501; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b669f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]