Summary

Objective

Local field potentials (LFP) arise from synchronous activation of millions of neurons, producing seemingly consistent waveform shapes and relative synchrony across electrodes. Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) are LFP associated with epilepsy that are commonly used to guide surgical resection. Recently, changes in neuronal firing patterns observed in the minutes preceding seizure onset were found to be reactivated during post-seizure sleep, a process called Seizure-Related Consolidation (SRC) due to similarities with learning-related consolidation. Because IIS arise from summed neural activity, we hypothesized that changes in IIS shape and relative synchrony would be observed in the minutes preceding seizure onset and would be reactivated preferentially during post-seizure slow-wave sleep (SWS).

Methods

Scalp and intracranial recordings were obtained continuously across multiple days from clinical macroelectrodes implanted in patients undergoing treatment for intractable epilepsy. Data from scalp electrodes were used to stage sleep. Data from intracranial electrodes were used to detect IIS using a previously established algorithm. Partial correlations were computed for sleep and wake periods before and after seizures as a function of correlations observed in the minutes preceding seizures. MRI and CT scans were co-registered with EEG to determine the location of the seizure onset zone (SOZ).

Results

Changes in IIS shape and relative synchrony were observed on a subset of macroelectrodes minutes prior to seizure onset and these changes were reactivated preferentially during post-seizure SWS. Changes in synchrony were greatest for pairs of electrodes where at least one electrode was located in SOZ.

Significance

These data suggest pre-seizure changes in neural activity and their subsequent reactivation occur across a broad spatio-temporal scale: from single neurons to LFP, both within and outside SOZ. The preferential reactivation of seizure-related changes in IIS during post-seizure SWS adds to a growing body of literature suggesting pathological neural processes may utilize physiological mechanisms of synaptic plasticity.

Keywords: seizure, inter-ictal spike, EEG, neural plasticity

Introduction

Local field potentials (LFP) display seemingly stereotyped waveform shapes (e.g., sharp-wave/ripples or K-complexes) that may be involved in different aspects of neural computation1. LFP arise from the summed synaptic and axonal activity of large numbers of neurons, and are known to organize neural activity2,3 and other LFP4. Physiological LFP have been shown to undergo subtle changes following spatial learning, such that spatial location can be decoded from changes in hippocampal theta5 and sharp-wave/ripples6, but is unclear whether these changes are associated with permanent changes to neural circuitry.

Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) are pathological LFP associated with epilepsy7. While mechanisms underlying IIS generation remain unclear, generation of IIS is thought to involve a paroxysmal depolarizing shift (PDS) during the initial, rapid rise of the spike, followed by a longer hyper-polarization phase8,9. This theory has been augmented to include observation of changes in neural activity preceding IIS onset by hundreds of msec10–13, but mechanisms by which single neuron activity generated locally or propagated through brain tissue contributes to IIS shape remain unclear14,15. Though a rich literature has established a correlation between IIS and seizure-generating brain regions10,16–18 and IIS often serve as biomarkers for tissue resection7,19, little is known about how various shapes of IIS arise. IIS recorded from individual electrodes may display multiple clusters of shapes that could arise from dynamic changes in local circuitry20, but within each cluster the shape and relative synchrony of IIS remain fixed during inter-ictal epochs.

Recently, seizures have been shown to activate sparse, specific neuronal populations, including regions outside seizure onset zone (SOZ) in rodents21 and humans22. Seizure-related activity changes have been observed again during post-seizure Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS), even when seizure and sleep epochs are separated by hours23, suggesting persistent alteration of neural circuitry. This phenomenon has been labeled Seizure-Related Consolidation (SRC), because of similarities to Cellular Consolidation24,25 observed through ensemble reactivation during post-behavioral SWS. Reactivation describes the re-emergence of coordinated activity first observed during a behavioral task (e.g., running a maze). Reactivation is measured by the use of partial correlation analysis, which describes changes in correlation following a behavioral event given pre-existing correlations. Reactivation is a population phenomenon; changes observed in individual neurons can be subtle, while effects across a population can be substantial24. Because these changes persist after cessation of the original behavior, Cellular Consolidation is thought to be involved in the formation of long-term memories24–26.

Because IIS arise from summed synaptic and axonal currents27,28, seizure-related changes in neuronal activity could alter IIS. While learning has been shown to change spectral power in theta29, persistent changes in in vivo waveform morphology or synchrony of temporally discrete LFP associated with prior experience have not been reported. While changes in the relative rates of different types of IIS have been linked to epileptogenesis30,31, seizure-dependent changes in IIS shape and synchrony have not. Seizure-related changes in single neuron activity prior to and following seizures (SRC) provide a plausible mechanism by which such changes could occur; namely, by “hijacking” learning-related neural mechanisms32. We therefore hypothesized that changes in IIS shape and synchrony should be observable prior to seizures and reactivated during post-seizure SWS.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Informed consent was obtained from patients undergoing intracranial EEG (iEEG) monitoring for drug-resistant Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (MTLE) in this Mayo Clinic Internal Review Board approved research protocol. Hybrid, polyurethane depth electrodes (diameter 1.3 mm, AD-Tech Medical Instrument Corp., Racine, WI) containing platinum-iridium clinical macroelectrodes (4 or 8 contact, 2.3 mm long, 5 or 10 mm spacing, 200–500 Ω) and research microelectrodes (9 or 18 oriented radially along the shaft between macro contacts and a bundle of 9 extending from the tip, 40 µm diameter, 500–1000 kΩ) were placed stereotactically into the mesial temporal lobe using an occipital or lateral approach. For both posterior and lateral approaches, the number, location, trajectory and depth of electrodes placed was similar across patients (one per hippocampus for posterior approach; three per hippocampus for lateral approach). Longitudinal electrodes were placed under imaging guidance (Stealth, Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) to avoid vasculature. Following surgery, scalp electrodes were placed in a modified configuration (described below) to avoid the craniotomy used for intracranial electrodes.

Data Acquisition

Scalp and intracranial macroelectrodes were sampled at 32 kHz by a Neuralynx (Bozeman, MT) Cheetah recording system and then filtered offline (10 kHz lowpass digital filter) and down-sampled to 5 kHz for analysis. Unlike the previous study23, only continuous EEG obtained from clinical macroelectrodes were analyzed. In all cases, a referential montage was used, with reference to a subgaleal strip macroelectrode.

Sleep Scoring and Identification of Seizures and Behavioral epochs

Scalp recordings were obtained from all patients for use in sleep scoring. Visual, manual sleep scoring was performed by a neurologist (EKS) board certified in sleep medicine (ABSM and ABMS/ABPN) and electroencephalography (ABCN and ABMS/ABPN CNP) in accordance with standard methods33,34, with modification for omission of electrooculogram (EOG) recording in some patients. Stage W (Wake) was determined by the presence of eye blinks and rapid eye movements visualized in EOG on frontal scalp electrodes, FP1 and FP2, accompanied by posteriorly dominant alpha (8–13 Hz) frequency rhythms with eyes closed, and comprising over 50% of the epoch (i.e., 16 or more seconds within a 30 second epoch). N3 (slow wave) sleep was scored when high voltage (>75 uV) delta (0.5–2.0 hertz) frequency EEG activity was seen in at least 20% of the epoch (i.e., at least 6 seconds within a 30 second epoch) in the frontal scalp derivations, using conventional International 10–20 System scalp electrode placements at FP1, FP2, FZ, F3, F4, CZ, C3, C4, O1, O2, and Oz, referenced to a subgaleal strip electrode. Behavioral epochs were the same as identified previously23 as continuous epochs of either SWS or Wake lasting at least 3 min within 2 hours before a seizure (the "Pre" epoch) or within 6 hours after a seizure (the "Post" epoch) (Figure 1.A & B), as well as the five minutes preceding seizure onset, called the “Near-Onset" epoch. Control epochs were identified according to the same criteria as above, but for a time-shifted centering point four hours before each seizure.

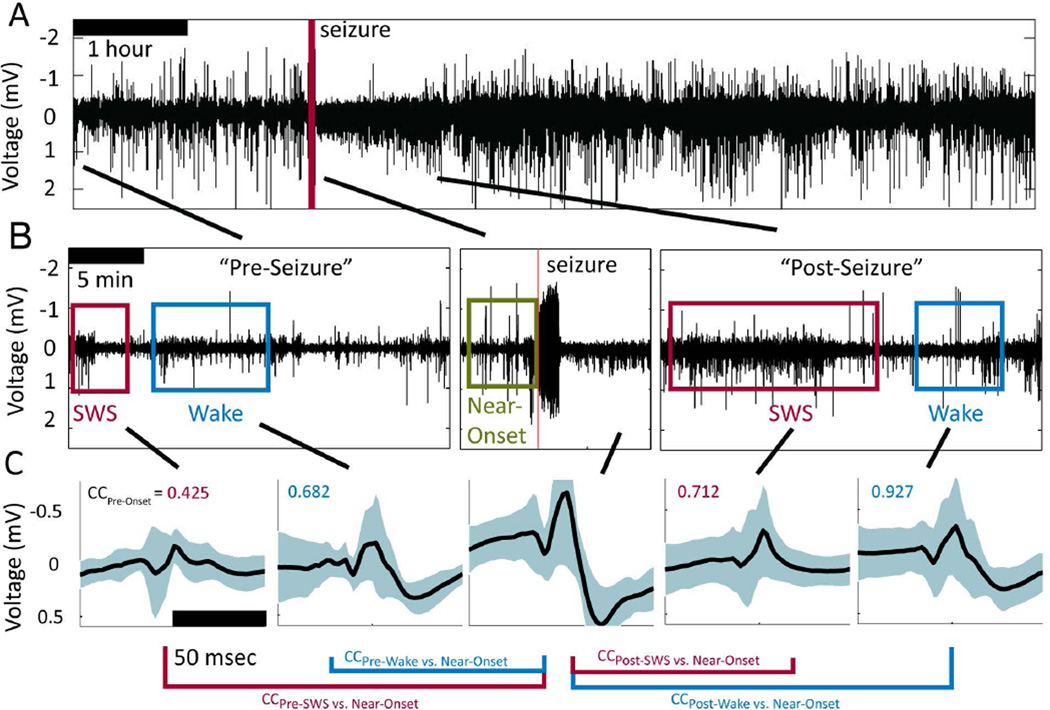

Figure 1.

Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) within identified behavioral epochs during long-duration, continuous recordings around a spontaneous seizure. A. Low-pass filtered intracranial EEG (iEEG) data from −2 hours to +6 hours around a seizure. B. Behavioral epochs identified from scalp EEG ("Wake" (blue box) and "SWS", Slow-Wave Sleep (red box)) that occurred close to one another in time, along with the Near-Onset behavioral window (green box). C. Average Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) identified objectively by an established algorithm35 for each of the five epochs for an electrode located in the SOZ. Solid black line shows the mean waveform and cyan bands show one standard deviation from the mean. Text in upper-left corner of each panel shows the correlation coefficient (CC) for the average waveform during that behavioral epoch with respect to that observed on the same macroelectrode during the Near-Onset epoch.

Identification of Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) Detection and Preprocessing

All data used for analysis other than sleep scoring were obtained from intracranial macroelectrodes. All pre-processing was done using Matlab. Inter-Ictal Spikes (IIS) were detected objectively using an automated detection described previously35. Continuous, iEEG data were low-pass filtered (200 Hz), windowed and centered on the peak energy of identified IIS. The window for IIS extended ±50 msec around the peak energy time (Figure 1C). For each IIS detection, the following parameters describing waveform morphology were computed: Peak Amplitude (the most negative voltage value in the 100 msec window), Valley Amplitude (the most positive voltage value in the 100 msec event), Energy (square root of the sum of the squared amplitude) and Absolute Peak Amplitude (the maximum absolute value). For each IIS detection, the correlation coefficient (Matlab 'corrcoef', Eqn. 1) was computed across all macroelectrodes, regardless of whether an IIS was detected on the other macroelectrodes, and the results stored to a MySQL database:

| [1] |

where n is the number of IIS and x and y are the mean waveforms on each macroelectrode. As an additional measure of wave shape similarity, the Mahalanobis distance (Matlab Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox 'mahal' Eqn. 2) was computed between IIS across behavioral epochs:

| [2] |

where x is the matrix of all waveforms, μ is the mean waveform, and S is the covariance of x. The Mahalanobis distance is a unitless quantity (similar to a z-score) describing the number of standard deviations between two waveforms, weighted by the variance in each dimension; decreasing distance is associated with increasing similarity between waveforms.

Data Analysis

All data analysis, statistics and figure generation was done in R (http://www.R-project.org/) and Matlab (Matlab R2011b, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). Because correlation coefficients (CC) from macroelectrode pairs are bounded on [−1 1], partial correlations were computed using beta (or standardized) regression to determine statistical significance when comparing CC from different behavioral epochs ('betareg' in R)36. The result is an estimate of the strength of the predictor variable on the dependent variable, which is measured as a z-score (i.e., in terms of standard deviations).

Results

Data were acquired from nine seizures in six patients (one seizure in three patients, two seizures in the remaining three patients). Using data obtained from scalp electrodes, a total of 279 minutes of behaviorally consistent windows were identified for 5 conditions: before seizures (the “Pre” epoch) for SWS (57 min) and Wake (64 min), after seizures (the “Post” epoch) for SWS (75 min) and Wake (83 min) and for 30 min prior to each seizure onset (the “Near Onset” epoch). Using data obtained from intracranial macroelectrodes, 14,407 IIS were detected during the identified epochs (for individual patients: N=2751, 5429, 631, 535, 1381, 3680).

Changes in IIS Shape are Sparse and Subtle

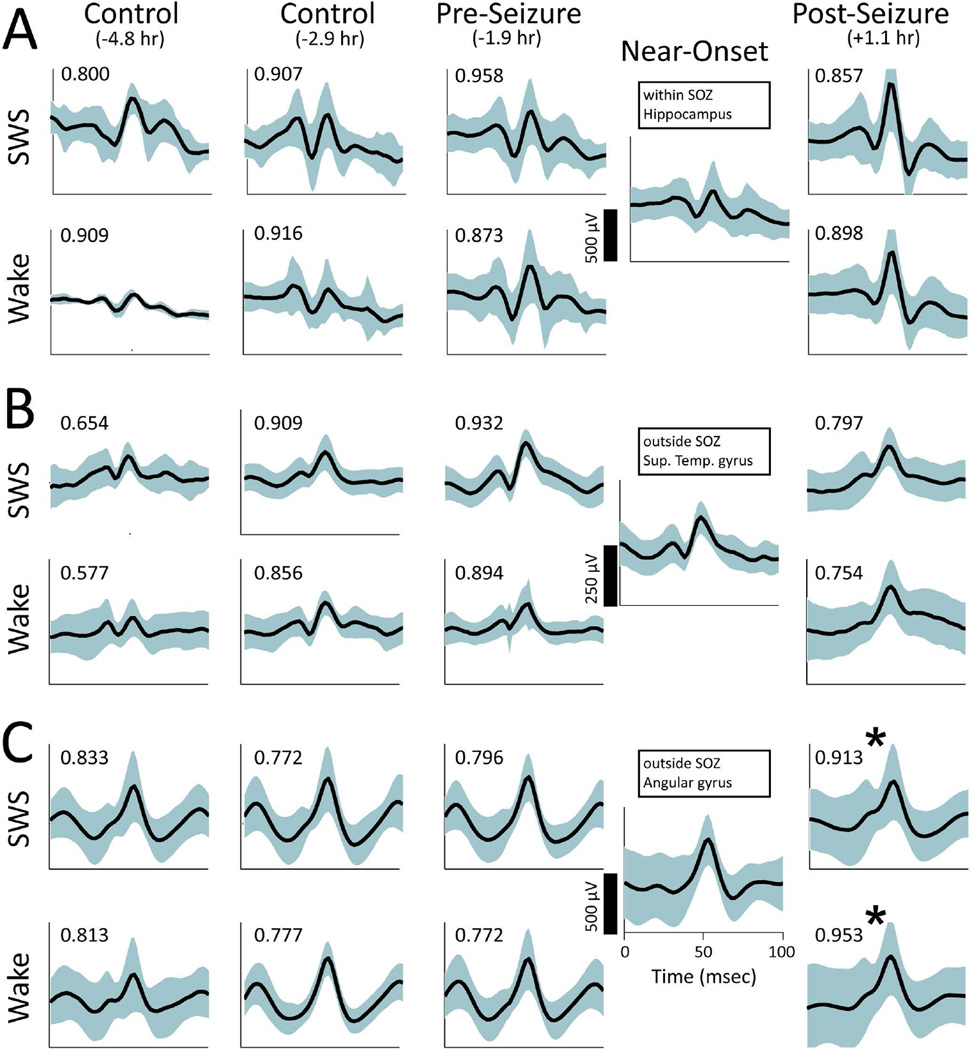

IIS shapes during the Near-Onset and Post epochs on some electrodes often appeared to be more similar to one another than those observed before the seizure, even though hours often intervened between the seizure and the subsequent behavioral epoch (Figure 1.C). Changes in IIS shape were subtle and only observed on a subset of macroelectrodes following a given seizure and appeared to be continuous, as opposed to all-or-none. Even in the SOZ, examples could be found where IIS shape was unchanged during Near-Onset and Post epochs compared to IIS during the Pre epochs (Figure 2.A). Consistent IIS shape following seizures was observed for macroelectrodes both within hippocampus (Figure 2.A) and outside hippocampus (Figure 2.B). Yet, when changes in IIS shape across epochs were observed during the Near-Onset epoch (Figure 2.C, SWS p=0.024, t-test, Wake p=0.006, t-test), similar changes in IIS shape were observed during the Post epoch. When changes in IIS shape were observed during Near-Onset and Post epochs on one macroelectrode (Figure 2.C), changes were not necessarily observed on neighboring macroelectrodes (Figure 2.B), suggesting the observed changes in IIS shape did not arise from electrode movement or extra-cerebral artifacts.

Figure 2.

Comparison of post-seizure changes in IIS from macroelectrodes on a single depth electrode. In each panel, IIS are shown for slow-wave sleep (SWS) on the top row and Wake on the bottom row. Each column shows data from a specific behavioral epoch (left-to-right: Control epoch before a time-shifted seizure, Control epoch after a time-shifted seizure, Pre epoch before the actual seizure, Near-Onset before the seizure, and Post epoch after the actual seizure. The average time relative to seizure onset in each case is shown in parentheses.) The black line shows the mean IIS waveform. Cyan bands show one standard deviation above and below the mean. Text in the upper left of each panel shows the CC for that behavioral epoch relative to the Near-Onset waveform. A. The most distal macroelectrode, which was located in hippocampus and within the seizure onset zone. B. Macroelectrode located in the Superior Temporal gyrus and outside the seizure onset zone. C. Macroelectrode adjacent to that shown in B, but located in Angular gyrus and outside the seizure onset zone. IIS during Near-Onset and both SWS and Wake following the seizure differ from those preceding the seizure. ('*' signifies p<.05, t-test).

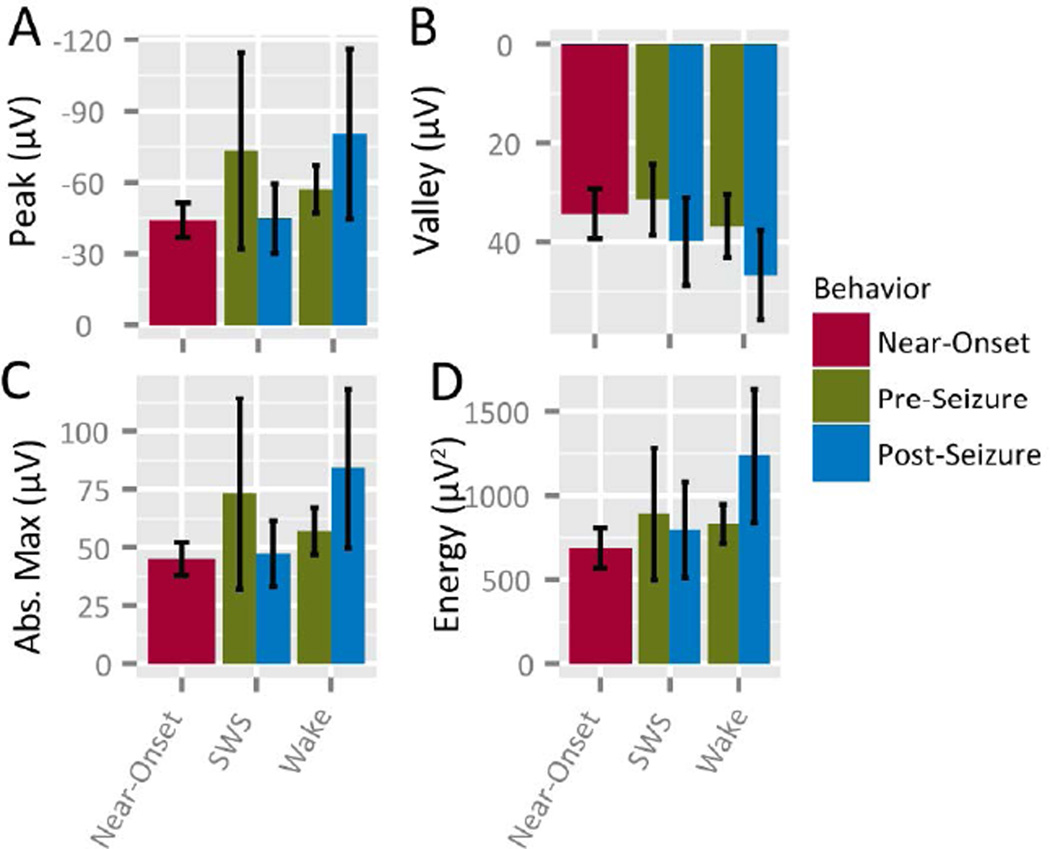

To determine whether average IIS parameters were changed across all electrodes during time epochs (Pre vs. Post seizures) or behavioral epochs (Sleep vs. Wake), IIS shape parameters (waveform peak amplitude, energy, valley amplitude and maximum absolute amplitude) and rates were computed for each channel and within-subject means were compared. No changes in average parameters were observed in any parameters for Pre and Post epochs relative to the Near-Onset epoch (Figure 3). No change was observed in rate or absolute maximum amplitude, nor was a change observed in mean waveform CC for a multi-factor comparison (Wake vs. Sleep p=0.641; Pre vs. Post p=0.495; interaction p=0.370; ANOVA). These results suggest that, though specific instances of seizure-related changes in IIS were observed (Fig. 2.C), little change was observed across the population of observed IIS; i.e., IIS changed on only a subset of macroelectrodes.

Figure 3.

IIS parameters do not change following seizures. A. Peak voltage, B. Valley voltage of IIS, C. Absolute Peak voltage (both positive- and negative-going voltage peaks), D. Energy (amplitude squared) of IIS and E. IIS Rate.

Changes in and Reactivation of IIS Relative Synchrony

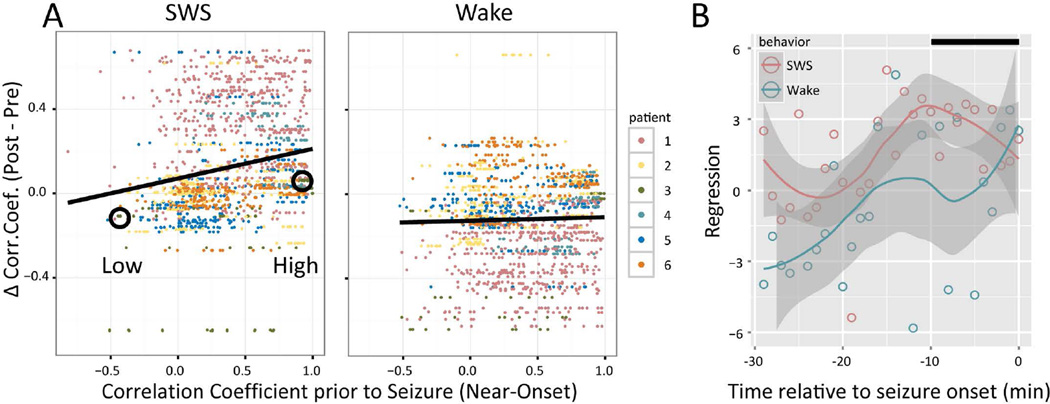

The observation of sparse, subtle changes in IIS shape during Near-Onset that persisted into Post-SWS even hours following a seizure was reminiscent of changes that were previously observed on a similar timescale and spatial distribution: seizure-related changes in single neuron activity23. Because IIS arise from the summed activation of single neurons, we hypothesized that increased single neuron correlations during the Near-Onset and Post SWS epochs23 alter IIS in a manner consistent with reactivation observed in single neuron activity23,24. To determine whether behavior-specific changes in IIS synchrony occurred, differences in correlation coefficients (CC) were computed for Post compared to Pre epochs and found to differ for SWS (0.036 ± 0.011; p=0.0486; paired t-test), but not for Wake (−0.053 ± 0.084; p=0.559; paired t-test). To determine whether these changes were consistent with Reactivation, CC were also computed for the Near-Onset epoch and partial regression computed for the Pre/Post epochs. After accounting for Pre-Seizure CC, Post-seizure CC changes were correlated to Near-Onset CC, but only during SWS and not Wake (Figure 4.A, SWS: p=0.027; Wake: p=0.159; beta regression), consistent with Reactivation. Beginning 30 min prior to seizure onset and separating the data into 1 min time bins, post-seizure increases in correlation increased for SWS roughly 10 min prior to onset, while changes in CC during Wake were never significant (Figure 4.B). For the control period shifted 4 hours prior to seizure onset, differences in CC for Post-seizure compared to Pre-seizure were not different from zero (SWS: 0.093 ± 0.084, p=0.306; Wake: 0.047 ± 0.091, p=0.611; beta regression). To determine whether selecting high/low Pre-Onset CC pairs biased these results, the same analysis was repeated for an alternate measure of waveform separation (Mahalanobis distance) for these same epochs, which produced a similar result: decreases in Mahalanobis distance (i.e., increased similarity) were significant during SWS for pairs with high Pre-Onset correlations (rho=0.5591, N=18, p=0.0196), while changes were not significant during SWS for pairs with low Pre-Onset correlations (rho=0.4459, p=0.0728), nor were changes in Mahalanobis distance significant during Wake for either high (rho=0.0751, p=0.7745) or low (rho=−0.0029, p=0.9911) Near-Onset correlation pairs.

Figure 4.

Correlation coefficient of IIS show Seizure-Related Consolidation (SRC) specific to Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS). A. Each dot shows the difference (during Post epoch minus during Pre epoch) in correlation coefficient (CC) between two macroelectrodes as a function of the CC in the 10 min preceding seizures. Differences in CCs increased during SWS as function of the magnitude of CC prior to the seizure, but not during Wake ('*' p<.05, beta regression). Dot color denotes patient, as shown in the legend at right. B. Beta regression coefficients during SWS and Wake for 1 min "seizure" time bins relative to seizure onset. The Loess confidence interval (gray band) for Wake (cyan) never differs from zero for the entire 30 min window prior to seizure onset. The confidence interval for SWS (magenta), however, is greater than both zero and the Wake confidence interval for most of the 30 min prior to seizure onset, except for the last few minutes prior to onset, when the confidence intervals overlap. The black bar at upper right denotes the 10 min time window used to compute the values shown in panel A. Circles denote macroelectrode pairs that are used as examples in Figure 5.

Changes in IIS relative synchrony during the Near-Onset epoch and their preservation in the Post epoch could be observed in the raw data obtained from specific pairs of electrodes. The analysis described above provided a means for identifying electrode pairs that showed observable changes. Macroelectrode pairs were selected that had "Low" and "High" Near-Onset cross-correlations where both pairs shared a common electrode. That is, for one electrode, a different electrode was identified that displayed “Low” Near-Onset CC with the first electrode, while a third electrode was identified that displayed “High” Near-Onset CC with the first electrode. For the pair whose Near-Onset IIS cross-correlation was “Low” (actually anti-correlated; Figure 5.A.1), the CC between IIS on these electrodes decreased following the seizure both during SWS (Pre: 0.9077; Post: −0.6313) and Wake (Pre: 0.6111, Post: −0.5926). Conversely, for the pair whose IIS cross-correlation was “High” during Near-Onset (Figure 5.B.2), the CC between IIS on these electrodes increased following the seizure during SWS (Pre: 0.9906; Post: 0.9957) and during Wake (Pre: 0.9908, Post: 0.9940). Investigating these particular examples more fully, changes in IIS could be observed as changes both in the shape of IIS on each macroelectrode and the relative timing of IIS between the two macroelectrodes. For the pair with “Low” Near-Onset CC (Figure 5.A.2), the peaks of the two average IIS waveforms shifted during Near-Onset and this shift persisted for more than 2 hours until the shift was reactivated following the seizure (Figure 5.A.2. "a"). For the pair with “High” Near-Onset CC, the peaks and valleys of the two average IIS waveforms shifted towards one another and this shift persisted for more than 2 hours following the seizure (Figure 5.B.2 "b" and "c"). Such changes in average IIS shape and synchrony were not observed between inter-ictal control periods, regardless of behavior or time epoch (Figure 4), suggesting that these changes in IIS shape arose from a different mechanism than that underlying normal, inter-ictal variation in IIS generation.

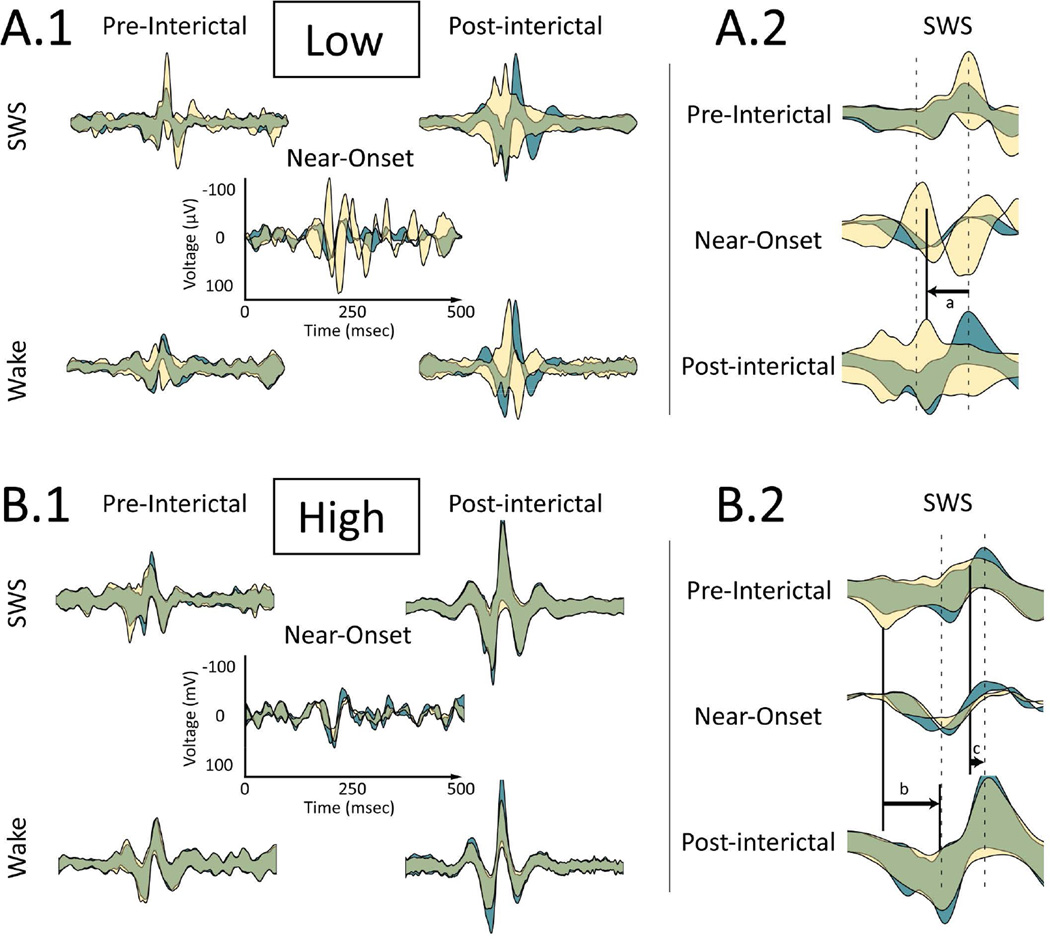

Figure 5.

Examples of IIS synchrony changes following a seizure based on correlation during Near-Onset. A. "Low" Near-Onset correlation pair circled in Figure 4. A.1 Average IIS ± one standard deviation for two macroelectrodes shown in cyan and yellow. IIS on the two macroelectrodes are centered to the peak of IIS recorded on the cyan waveform. Areas of overlap between the two appear as green. top row: Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS), bottom row: Wake, left column: Pre epoch before the seizure; right column: Post epoch after the seizure, middle: Near-Onset epoch. Time and voltage scales are shown on the Near-Onset panel and are consistent across all panels. The low Near-Onset correlation persists into post-seizure SWS and Wake, where the overlap between IIS recorded from the two macroelectrodes decreases (i.e., the yellow and cyan areas are more visible). A.2 Expanded time view around the IIS peak during SWS (top) Pre epoch before the seizure, (middle) Near-Onset and (bottom) Post epoch after the seizure. Dotted lines show the peak and trough of the Near-Onset average waveform for IIS from the cyan waveform. Changes to IIS synchrony for the yellow waveform after the seizure reflect changes during the Near-Onset: (a) The peak of IIS recorded for the yellow waveforms shifts backwards relative to IIS recorded from the cyan waveforms. B. "High" Near-Onset correlation pair circled in Figure 4. B.1 Panel arrangement is the same as in A.1. The high Near-Onset correlation persists into Post-seizure SWS and Wake, where the overlap between IIS recorded from the two macroelectrodes increases (i.e., the green area signifying overlap increases). B.2 Expanded time view around IIS during SWS, as described in A.2. The (b) valley and (c) peak of IIS recorded for the yellow waveforms shifts forward in time during Near-Onset and Post epoch after the seizure with respect to the cyan IIS waveform.

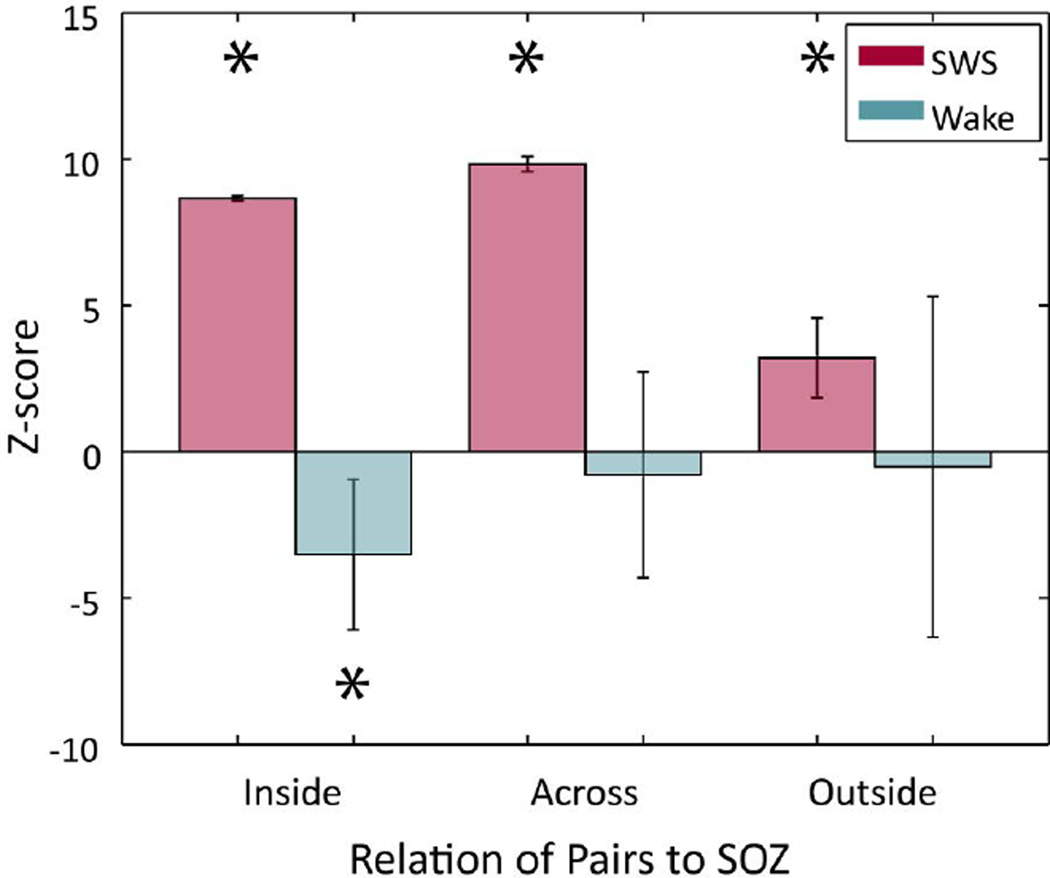

To determine whether observed changes in IIS were related to the seizure onset zone (SOZ), the location relative to SOZ of each macroelectrode was established (see Methods) and CC values were grouped according to whether both macroelectrodes were "Inside" or "Outside" the SOZ, or whether the two electrodes were located "Across" the SOZ boundary. Partial regressions were computed for these post-hoc groupings. For SWS, all groups showed significant, positive z-scores (Inside z=8.66, p<1E-6; Across z=9.83, p<1E-6; Outside z=3.21, p=0.00131, beta regression), while for Wake, all groups showed negative z-scores, but only the Inside group was significant (Inside z=−3.50, p=0.00046, Across z=−0.788, p=0.431, Outside z=−0.513, p=0.608, beta regression) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Seizure-Related Consolidation of IIS is strongest when at least one electrode is within the seizure onset zone. Across-subject beta regression scores grouped by electrode location relative to seizure onset zone (SOZ) were positive for all groups during SWS (magenta), but were largest for the "Inside" and "Across" groups. Scores during Wake (cyan) only differed from zero when both macroelectrodes were "Inside" SOZ, but then the changes were anti-correlated with Near-Onset activity.

Discussion

These results show that the shape and relative synchrony of IIS recorded on intracranial macroelectrodes change on a subset of macroelectrodes in the minutes preceding a seizure and that these changes are reactivated hours later. Post-seizure changes in IIS shape and synchrony were behaviorally specific, being greatest during SWS. The magnitude of these modifications was continuous, rather than all-or-none; IIS waveforms on many channels (both within the SOZ and outside of it) changed only slightly or not at all. The changes could differ on a small spatial scale; both increased and decreased correlation changes relative to the same macroelectrode were observed for macro-contacts located on the same physical electrode (Figures 2 & 5), consistent with the "fractured" spatial distribution of changes in multiunit22 and single neuron activity23 observed prior to seizures. The largest changes in IIS synchrony were observed when at least one electrode was located in the seizure onset zone, suggesting these changes may be related to the spread of the epileptogenic zone.

Alternative Explanations

Increased IIS rates could lead to spurious increases in correlation coefficients37,38, but while Post-seizure CC increased for SWS, Post-seizure IIS rates increased more during Wake than SWS. It is also possible that, following seizures, there is a general increase in IIS correlations, but then it is not clear why IIS during Wake would not be affected (Figure 3.A). Even if such a general increase in overall IIS correlation following seizures were limited to post-seizure SWS, it is not clear why changes to IIS shape and synchrony that appeared specifically during the Near-Onset epoch would reappear during sleep (Figure 2.C). Another possibility is that seizure-related movement shifted electrode positions, but this would not explain why the changes in IIS were largest during sleep or why those changes were recorded only on some contacts of a given, physical electrode, but not others (Figure 2).

Synchronization of both neural activity and field potentials may play multiple roles in epilepsy, including the possibility that increased synchronization of field potentials reflects seizure inhibiting mechanisms39. Pre-ictal and ictal states also activate seizure inhibiting mechanisms (e.g., inhibitory surround) and seizures are thought to terminate when long-range synchronization is established across brain structures40,42. Synchronous activity arising from these mechanisms could also be reactivated as part of the consolidation process during post-seizure sleep, possibly interfering with the consolidation of synchronous activity associated with the seizure itself. The relationship between possibly pro- and anti-epileptogenic consequences of seizure-related synchrony following seizures could also relate to other observations relating interictal spikes to epileptogenesis. Many (but not all) of the changes observed in IIS shape preceding seizures produced increasingly temporally asymmetric waveform shapes (Figure 1C). Asymmetric IIS shape has been associated with epilepsy pathology43. Temporal asymmetry implies underlying nonlinear generators44, which in turn have been shown to characterize epileptogenic brain areas45,46. One test of whether SRC overall favors pro- or anti-epileptogenic mechanisms would involve experiments that interrupt or enhance post-seizure sleep. Our observed associations between SWS and reactivated seizure-related interictal spike characteristics imply that state-dependent synaptic homeostatic mechanisms may reactivate and reinforce seizure engrams. Theoretical analyses have shown the importance of preventing saturation of synapses to maximize information storage via neural plasticity mechanisms47. The synaptic homeostasis hypothesis holds that an essential function of sleep is the downscaling of synaptic strength to energetically sustainable levels, thereby preventing saturation and impaired information processing and facilitating future learning and space conservation65. Targeted disruption of SWS48,49 provides one approach for testing whether seizure-related consolidation is governed by similar mechanisms.

Mechanisms of IIS modification

The change in IIS shapes following seizures was much larger than the variability of the shape of IIS observed during inter-ictal periods, suggesting a permanent alteration in the underlying neural circuitry generating the IIS (Figure 4). The finding that changes in partial correlation were strongest for electrode pairs across SOZ boundaries raises the possibility that these alterations play a role in epileptogenesis, recruiting neural circuits during seizures and then capturing them via physiological, learning-related mechanisms during post-seizure SWS32. Changes in shape and synchrony of IIS from only some macroelectrodes following a single seizure suggests either the emergence of new IIS generators or the introduction of a relative temporal shift between different generators. The observation that changes in single neuron activity can precede IIS by hundreds of msec suggests the existence of a broad repertoire of neural mechanisms that could be altered following a single seizure11,12. This is supported by the observation of more than a dozen types or classes of IIS waveform shapes10,12,14, suggesting that IIS waveforms reflect a diversity of neural generators. This would also be consistent with the development of Pathological Interconnected Networks (“PINs”) of neurons being strengthened over repeated seizures50, particularly if only specific sub-assemblies of those PINs were selectively activated during any given seizure23. Because IIS can activate different specific neural circuits on each spike20, the parallel development of multiple PINs in the same tissue could provide the necessary variability in underlying neural generators to produce modified IIS shapes following individual seizures.

Comparison to Multiple, Single Neuron Studies

The temporal and spatial dimensions IIS changes during Near-Onset and Post-SWS were similar to seizure-related changes observed in patterned, single neuron activity. Changes in the firing rates of individual neurons in the minutes preceding seizure onset are reactivated during post-seizure SWS23. Changes occur for some neurons recorded on a single microwire, but not for other neurons recorded on the same microwire (i.e., the network activated by the seizure is sparse) and changes can occur for neurons located outside the SOZ and even the opposite hemisphere (i.e., the network is distributed). Not all microwires within the SOZ record changes in seizure-related neural activity, giving the appearance of a spatially fragmented or "fractured" pattern of activation22. In animals, seizure-related changes in neural activity show a similar sparse, distributed and fractured pattern21, which shares similarities to neuronal activity patterns observed during physiological behaviors24. Patterned neural activity observed during behavior is reactivated during SWS, which is required for both permanent modification of neural activity patterns and behavioral learning24,51,56, a process known as Cellular Consolidation57. Whether epilepsy "hijacks" cellular machinery related to physiological learning to promote epileptogenesis is unclear32, but seizures do activate learning-related immediate early genes58 and many genes linked to epilepsy are also linked to pathways involving neuronal synchrony59. The activation of sparse neuronal circuits during seizures shows that the reactivation of seizure-related activity can occur hours after the seizure and occurs selectively during SWS, similar to the environment-specific activation of sparse, neural assemblies24 and immediate-early genes60 following spatial learning tasks. Spatially, just as neuronal activation during the Pre-Onset epoch reveals a "fractured" geometry in the seizure onset zone containing spatial gaps in seizure-related activity22,61, alterations in IIS were observed on macroelectrodes outside the SOZ and on macroelectrodes that were adjacent to macroelectrodes where no changes were observed (see Figure 2.B&C). These similarities between changes to neuronal and field potential activity suggest that seizure-related modifications to brain function span multiple spatiotemporal scales61.

The importance of post-seizure sleep

The central role of sleep in epilepsy has a rich history62,63, but the study of continuing pathology during sleep (when plasticity mechanisms are known to be activated) following seizures has received less attention. Because animal studies have shown that interference with consolidation disrupts previously learned tasks, a similar therapeutic benefit may be derived from interfering with post-seizure sleep64. Current epilepsy drug and stimulation therapies target the prevention of seizure initiation, but do not address effects following a seizure that may make future seizures more likely; i.e., there are currently no epilepsy therapies that are anti-epileptogenic. It is not clear whether the reactivation of seizure-related neuronal activity during post-seizure sleep makes future seizures more likely to emulate past seizures, but it is reasonable to hypothesize that strengthening connections across the SOZ border could play a role in expanding the SOZ. If seizure-related, sleep-dependent, patterned reactivation (i.e., cellular consolidation) does play a role in expanding the SOZ, then it is also reasonable to hypothesize that interference with reactivation of seizure-related activity during SWS following seizures could produce a new class of therapies that would be "anti-epileptogenic".

Key Points.

-

–

The shape and relative synchrony of IIS change in the minutes preceding seizure onset.

-

–

These changes are reactivated during post-seizure SWS, consistent with Consolidation theory.

-

–

Reactivation of correlations is strongest when at least one macroelectrode is located within the SOZ.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the technical support provided by Cindy Nelson and Karla Crockett. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01-NS063039 (GW) and R01-NS078136 (MS), Mayo Clinic Discovery Translation Grant, and the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents — EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Wilson MA, et al. Theta phase precession in hippocampal neuronal populations and the compression of temporal sequences. Hippocampus. 1996;6:149–172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou J-L, Lenck-Santini P-P, Zhao Q, et al. Effect of interictal spikes on single-cell firing patterns in the hippocampus. Epilepsia. 2007;48:720–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staresina BP, Bergmann TO, Bonnefond M, et al. Hierarchical nesting of slow oscillations, spindles and ripples in the human hippocampus during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1679–1686. doi: 10.1038/nn.4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal G, Stevenson IH, Berényi A, et al. Spatially Distributed Local Fields in the Hippocampus Encode Rat Position. Science. 2014;344:626–630. doi: 10.1126/science.1250444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taxidis J, Anastassiou CA, Diba K, et al. Local Field Potentials Encode Place Cell Ensemble Activation during Hippocampal Sharp Wave Ripples. Neuron. 2015;87:590–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staba RJ, Stead M, Worrell GA. Electrophysiological Biomarkers of Epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11:334–346. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto H, Marsan CA. Cortical cellular phenomena in experimental epilepsy: interictal manifestations. Exp Neurol. 1964;9:286–304. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(64)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prince DA. Inhibition in “epileptic” neurons. Exp Neurol. 1968;21:307–321. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyler AR, Ojemann GA, Ward AA., Jr Neurons in human epileptic cortex: correlation between unit and EEG activity. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:301–308. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller CJ, Truccolo W, Gale JT, et al. Heterogeneous neuronal firing patterns during interictal epileptiform discharges in the human cortex. Brain. 2010;133:1668–1681. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarado-Rojas C, Lehongre K, Bagdasaryan J, et al. Single-unit activities during epileptic discharges in the human hippocampal formation. Front Comput Neurosci. 2013;7:140. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2013.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frauscher B, von Ellenrieder N, Ferrari-Marinho T, et al. Facilitation of epileptic activity during sleep is mediated by high amplitude slow waves. Brain. 2015;138:1629–1641. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alarcon G, Guy CN, Binnie CD, et al. Intracerebral propagation of interictal activity in partial epilepsy: implications for source localisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:435–449. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grouiller F, Thornton RC, Groening K, et al. With or without spikes: localization of focal epileptic activity by simultaneous electroencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Brain. 2011;134:2867–2886. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penfield W, Jasper HH. Epilepsy and the functional anatomy of the human brain. Little, Brown. 1954:932. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sammaritano M, Gigli GL, Gotman J. Interictal spiking during wakefulness and sleep and the localization of foci in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1991;41:290–297. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.2_part_1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Curtis M, Avanzini G. Interictal spikes in focal epileptogenesis. Progress in Neurobiology. 2001;63:541–567. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel J. Biomarkers in epilepsy: introduction. Biomark Med. 2011;5:537–544. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabolek HR, Swiercz WB, Lillis KP, et al. A Candidate Mechanism Underlying the Variance of Interictal Spike Propagation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3009–3021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5853-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bower MR, Buckmaster PS. Changes in Granule Cell Firing Rates Precede Locally Recorded Spontaneous Seizures by Minutes in an Animal Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2431–2442. doi: 10.1152/jn.01369.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bower MR, Stead M, Meyer FB, et al. Spatiotemporal neuronal correlates of seizure generation in focal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:807–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bower MR, Stead M, Bower RS, et al. Evidence for Consolidation of Neuronal Assemblies after Seizures in Humans. J Neurosci. 2015;35:999–1010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3019-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of Hippocampal Ensemble Memories During Sleep. Science. 1994;265:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudai Y, Morris RGM. Memorable Trends. Neuron. 2013;80:742–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buzsaki G. Two-stage model of memory trace formation: A role for “noisy” brain states. Neuroscience. 1989;31:551–570. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katzner S, Nauhaus I, Benucci A, et al. Local Origin of Field Potentials in Visual Cortex. Neuron. 2009;61:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Curtis M, Jefferys JGR, Avoli M. Interictal Epileptiform Discharges in Partial Epilepsy: Complex Neurobiological Mechanisms Based on Experimental and Clinical Evidence. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet] 4th. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [cited 2015 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK98179/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendrick KM, Zhan Y, Fischer H, et al. Learning alters theta amplitude, theta-gamma coupling and neuronal synchronization in inferotemporal cortex. BMC Neuroscience. 2011;12:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chauvière L, Doublet T, Ghestem A, et al. Changes in interictal spike features precede the onset of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:805–814. doi: 10.1002/ana.23549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huneau C, Benquet P, Dieuset G, et al. Shape features of epileptic spikes are a marker of epileptogenesis in mice. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2219–2227. doi: 10.1111/epi.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beenhakker MP, Huguenard JR. Neurons that Fire Together Also Conspire Together: Is Normal Sleep Circuitry Hijacked to Generate Epilepsy? Neuron. 2009;62:612–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel A, Chesson A, et al. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. First. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications [Internet] 2012 Available from: www.aasmnet.org. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barkmeier DT, Shah AK, Flanagan D, et al. High inter-reviewer variability of spike detection on intracranial EEG addressed by an automated multi-channel algorithm. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2012;123:1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuart A, Ord K, Arnold S. Kendall's Advanced Theory of Statistics, Classical Inference and the Linear Model. Chichester: Wiley; 2010. p. 912. Volume 2A edition. [Google Scholar]

- 37.De la Rocha J, Doiron B, Shea-Brown E, et al. Correlation between neural spike trains increases with firing rate. Nature. 2007;448:802–806. doi: 10.1038/nature06028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kucewicz MT, Cimbalnik J, Matsumoto JY, et al. High frequency oscillations are associated with cognitive processing in human recognition memory. Brain. 2014;137:2231–2244. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiruska P, de Curtis M, Jefferys JGR, et al. Synchronization and desynchronization in epilepsy: controversies and hypotheses. The Journal of Physiology. 2013;591:787–797. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiff SJ, Sauer T, Kumar R, et al. Neuronal spatiotemporal pattern discrimination: The dynamical evolution of seizures. NeuroImage. 2005;28:1043–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schindler K, Elger CE, Lehnertz K. Increasing synchronization may promote seizure termination: Evidence from status epilepticus. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118:1955–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer MA, Eden UT, Kolaczyk ED, et al. Coalescence and Fragmentation of Cortical Networks during Focal Seizures. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10076–10085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6309-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gloor P. The EEG and differential diagnosis of epilepsy. In: Van Duyn HDD, Van Huffelen AC, editors. Current concepts in clinical neurophysiology. 1977. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss G. Time-Reversibility of Linear Stochastic Processes. Journal of Applied Probability. 1975;12:831–836. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van der Heyden MJ, Diks C, Pijn JPM, et al. Time reversibility of intracranial human EEG recordings in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Physics Letters A. 1996;216:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrzejak RG, Widman G, Lehnertz K, et al. The epileptic process as nonlinear deterministic dynamics in a stochastic environment: an evaluation on mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2001;44:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNaughton BL, Morris R. Hippocampal synaptic enhancement and information storage within a distributed memory system. Trends in Neurosciences. 1987;10:408–415. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellesi M, Riedner BA, Garcia-Molina GN, et al. Enhancement of sleep slow waves: underlying mechanisms and practical consequences. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:208. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhn M, Wolf E, Maier JG, et al. Sleep recalibrates homeostatic and associative synaptic plasticity in the human cortex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12455. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bragin A, Wilson CL, Engel J. Chronic Epileptogenesis Requires Development of a Network of Pathologically Interconnected Neuron Clusters: A Hypothesis. Epilepsia. 2000;41:S144–S152. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nader K, Schafe GE, Le Doux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406:722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pastalkova E, Serrano P, Pinkhasova D, et al. Storage of Spatial Information by the Maintenance Mechanism of LTP. Science. 2006;313:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1128657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Girardeau G, Benchenane K, Wiener SI, et al. Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1222–1223. doi: 10.1038/nn.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ego-Stengel V, Wilson MA. Disruption of ripple-associated hippocampal activity during rest impairs spatial learning in the rat. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1–10. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Lavilléon G, Lacroix MM, Rondi-Reig L, et al. Explicit memory creation during sleep demonstrates a causal role of place cells in navigation. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:493–495. doi: 10.1038/nn.3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bonin RP, De Koninck Y. Reconsolidation and the regulation of plasticity: moving beyond memory. Trends in Neurosciences. 2015;38:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dudai Y, Morris RGM. To consolidate or not to consolidate: what are the questions? In: Bolhuis JJ, editor. Brain, Perception, Memory Advances in Cognitive Neuroscience [Internet] Oxford University Press; 2000. [[cited 2015 Jul 31]]. pp. 149–162. Available from: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198524823.001.0001/acprof-9780198524823. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rakhade SN, Jensen FE. Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:380–391. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noebels JL. The Biology of Epilepsy Genes. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2003;26:599–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, et al. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:1120. doi: 10.1038/16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stead M, Bower M, Brinkmann BH, et al. Microseizures and the spatiotemporal scales of human partial epilepsy. Brain. 2010;133:2789–2797. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kellaway P. Sleep and Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1985;26:S15–S30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1985.tb05720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eriksson SH. Epilepsy and sleep. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:171–176. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283445355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alberini CM, LeDoux JE. Memory reconsolidation. Current Biology. 2013;23:R746–R750. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]