Abstract

Nuclear export receptor CRM1 binds highly variable nuclear export signals (NESs) in hundreds of different cargoes. Previously we have shown that CRM1 binds NESs in both polypeptide orientations (Fung et al., 2015). Here, we show crystal structures of CRM1 bound to eight additional NESs which reveal diverse conformations that range from loop-like to all-helix, which occupy different extents of the invariant NES-binding groove. Analysis of all NES structures show 5-6 distinct backbone conformations where the only conserved secondary structural element is one turn of helix that binds the central portion of the CRM1 groove. All NESs also participate in main chain hydrogen bonding with human CRM1 Lys568 side chain, which acts as a specificity filter that prevents binding of non-NES peptides. The large conformational range of NES backbones explains the lack of a fixed pattern for its 3-5 hydrophobic anchor residues, which in turn explains the large array of peptide sequences that can function as NESs.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.23961.001

Research Organism: S. cerevisiae, Human, Virus

Introduction

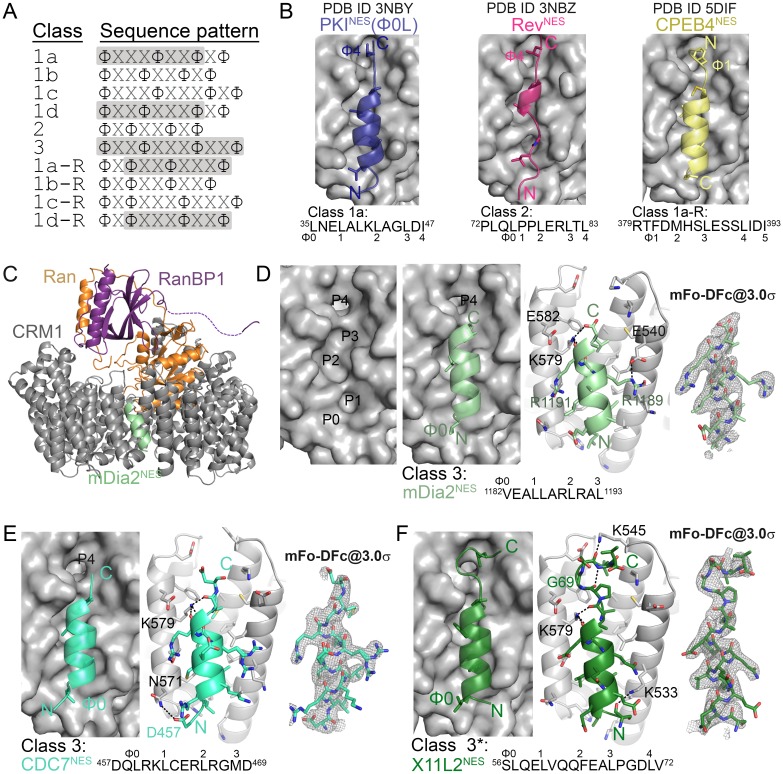

The chromosome region maintenance 1 protein (CRM1) or Exportin-1 (XPO1) binds 8–15 residues-long nuclear export signals (NESs) in hundreds of different protein cargoes (Fornerod et al., 1997; Fukuda et al., 1997; Stade et al., 1997; Ossareh-Nazari et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2012a; Kırlı et al., 2015; Thakar et al., 2013). NES sequences are very diverse but each usually has 4–5 hydrophobic residues (often Leu/Val/Ile/Phe/Met; labeled Ф0–5) that bind hydrophobic pockets (labeled P0–P4) in a hydrophobic groove formed by HEAT repeats 11 and 12 of CRM1 (9–16). The hydrophobic anchor residues are arranged in many ways, currently described by ten consensus patterns for corresponding NES classes 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 2, 3, 1a-R, 1b-R, 1c-R and 1d-R (Figure 1A) (Fung et al., 2015).

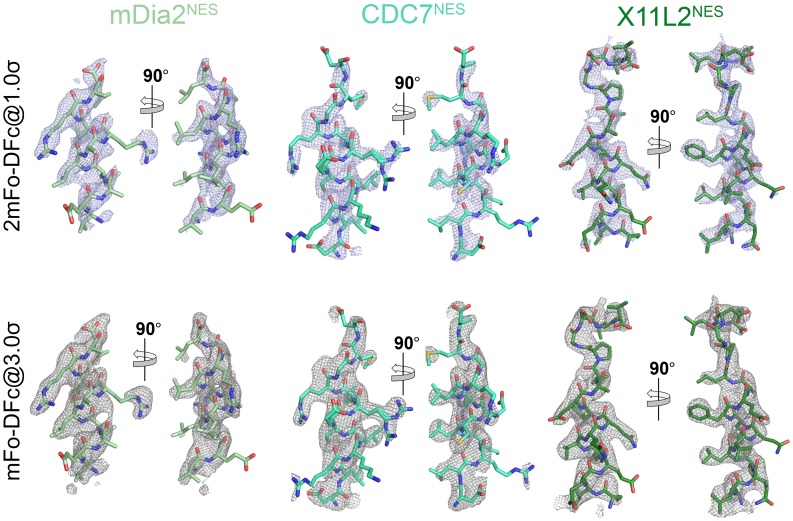

Figure 1. Structures of CRM1-bound NESs that match the potentially all-helical class 3 pattern.

(A) Current NES sequence patterns (Φ is Leu, Val, Ile, Phe or Met and X is any amino acid). Potential amphipathic α-helices, predicted with hydrophobic patterns of i, i + 4, i + 7 or i, i + 3, i + 7 or i, i + 3, i + 7, i + 10, are shaded grey. (B) Structure of PKINES(Ф0L) (dark blue, PDB ID: 3NBY), RevNES (pink, 3NBZ) and CPEB4NES (yellow, 5DIF) bound to the NES-binding groove of CRM1 (grey surface). NESs are shown in cartoon representations with their Φ side chains shown as sticks. (C) The overall structure of the engineered ScCRM1 (grey)-Ran•GTP (orange)-RanBP1 (purple)-mDia2NES (pale green) complex. The structure of (D) mDia2NES (pale green), (E) CDC7NES (green-cyan) and (F) X11L2NES (forest) bound to the NES-binding groove of ScCRM1 in the engineered ScCRM1-Ran-RanBP1 complex. *The X11L2NES sequence matches the class 3 pattern, but binds CRM1 according to the new hydrophobic pattern Φ0XXΦ1XXXΦ2XXΦ3XXXΦ4 that we termed the class 4 pattern. mDia2NES is not shown in the leftmost panel of (D) to view the five hydrophobic pockets (P0–P4) of the CRM1 groove. Rightmost panels of (D–F): overlays of 3.0σ positive densities of kick OMIT mFo-DFc maps (calculated with peptides omitted) and final coordinates of the NES peptides. Middle panels of (D–F): black dashes show CRM1-NES hydrogen bonds and polar contacts.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.23961.002

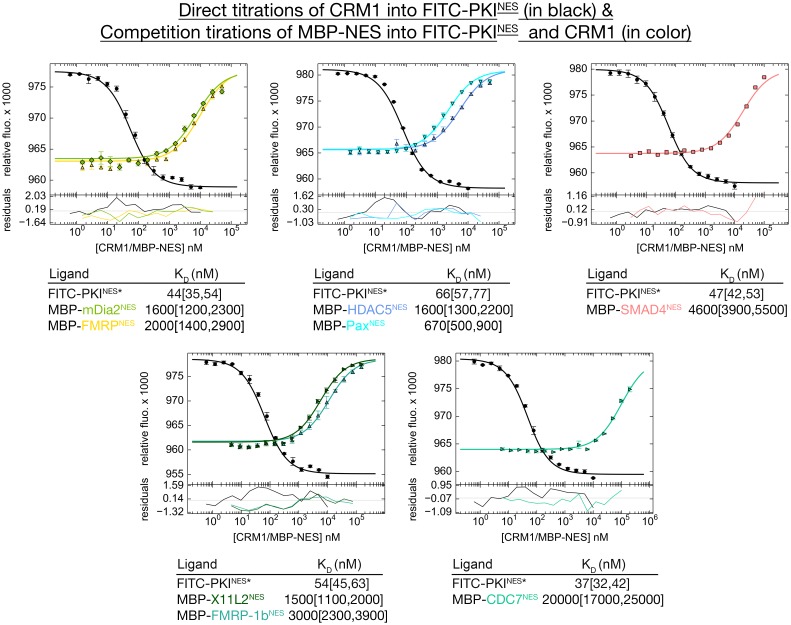

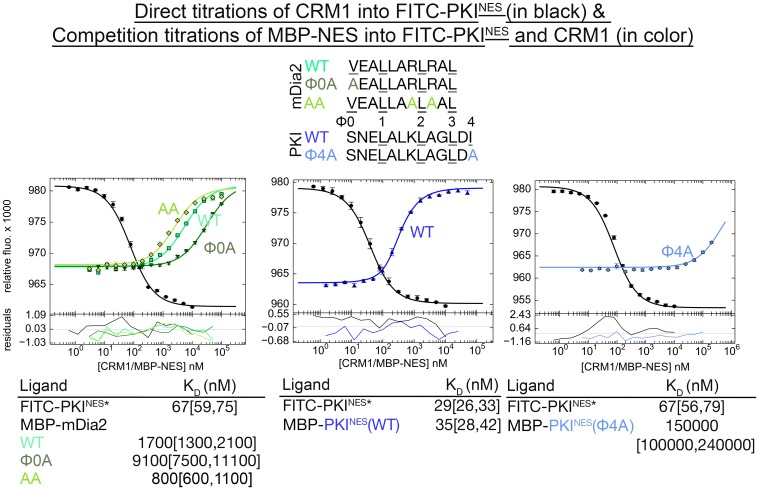

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Binding affinities of NES to CRM1 measured by differential bleaching experiments.

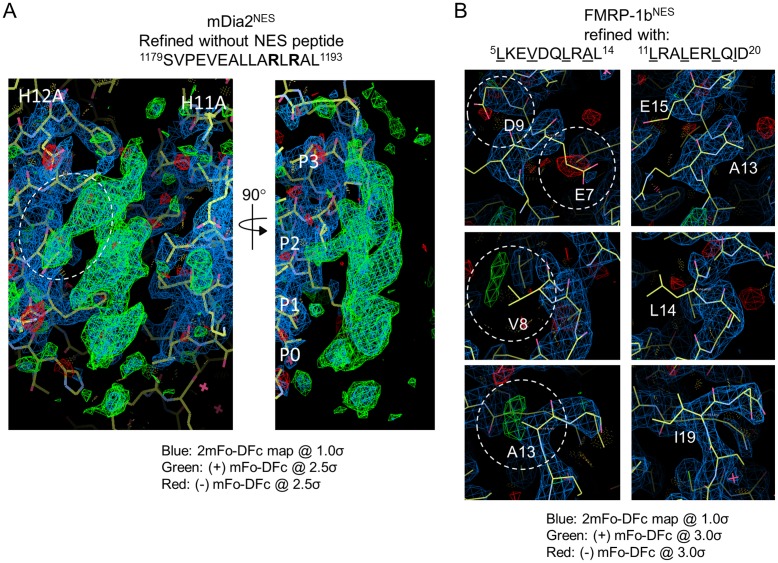

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Modeling strategy for NESs with weak Φ side chain densities.

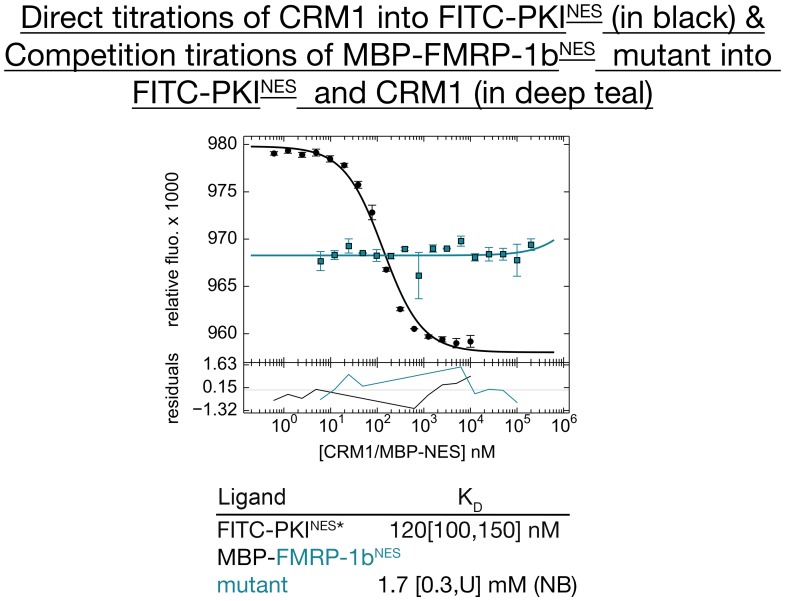

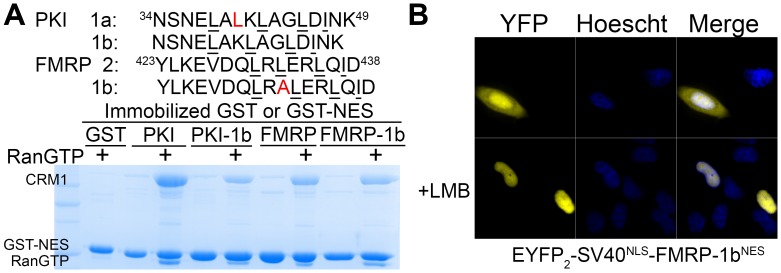

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Mutagenesis of FMRP-1bNES to validate the sequence assignment of the NES.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Electron densities of the NES peptides.

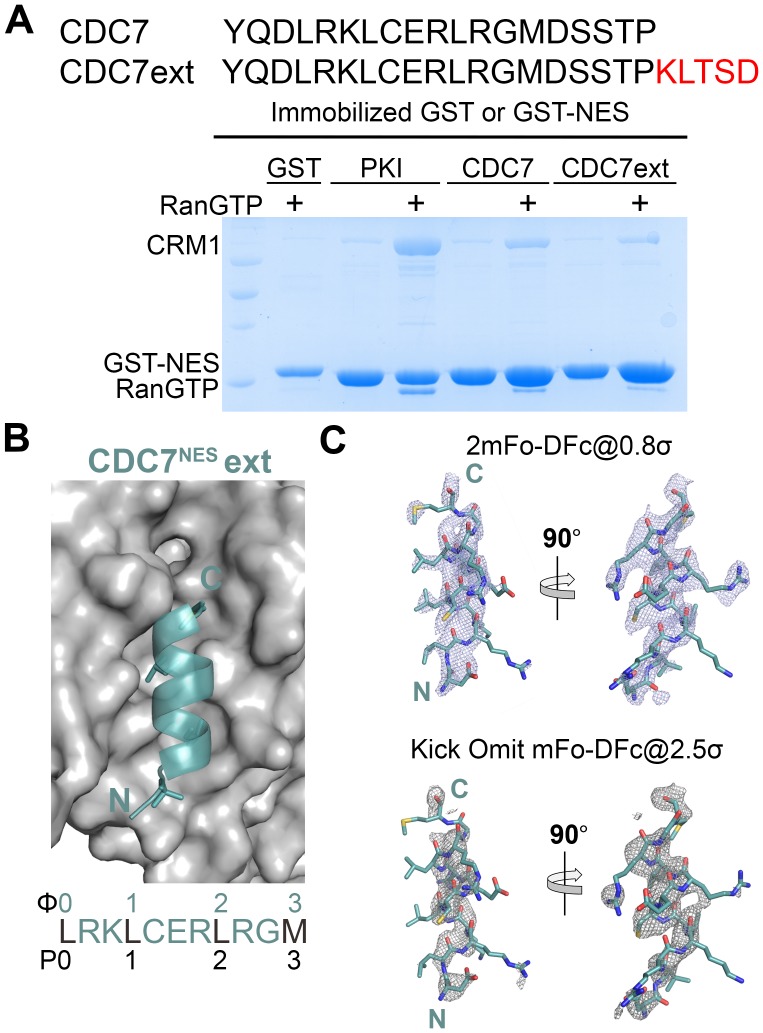

Figure 1—figure supplement 5. A longer CDC7NES peptide binds the CRM1 groove without interacting with the P4 pocket.

Figure 1—figure supplement 6. Variable number of Ф side chains are needed to have an active NES.

Previous structures of CRM1 bound to five different NESs showed virtually identical NES-binding grooves (Fung et al., 2015; Monecke et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2009; Güttler et al., 2010). NESs from Snurportin-1 (SNUPNNES; class 1c) and Protein Kinase A Inhibitor (PKINES; class 1a) bind CRM1 as α-helix followed by a short β-strand, while the proline-rich NES from HIV-1 REV (RevNES; class 2) adopts mostly extended conformation (Figure 1B) (Güttler et al., 2010). The majority of CRM1-NES interactions involve NES hydrophobic anchor side chains, with very few polar and main chain interactions. Previously, we studied NESs with the Φ1XXΦ2XXXΦ3XXΦ4 (class 3) pattern where the i, i + 3, i + 7, i + 10 Φ positions suggested a single long amphipathic helix. However, it is perplexing that a long all-helical peptide could fit in the narrow tapering CRM1 groove. Structures of such NESs from kinase RIO2 and cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein 4 (hRio2NES, CPEB4NES) showed that they do not adopt all-helical conformations but unexpectedly adopt helix-strand conformations that bind CRM1 in the opposite or minus (−) polypeptide direction to that of SNUPNNES, PKINES and RevNES ((+) NESs) (Fung et al., 2015). hRio2NES and CPEB4NES were hence reclassified as class 1a-R NESs (Figure 1A).

We do not understand the extent of NES structural diversity nor how NESs with different hydrophobic patterns that presumably reflect different secondary structures all bind to the seemingly invariant and three-dimensionally constrained CRM1 groove. Here, eight new structures of CRM1 bound to diverse NESs show several different and unexpected NES backbone conformations that share only a common one-turn helix element. All NESs also participate in hydrogen bonding with Lys568 of HsCRM1, and mutagenic/structural analysis identifies Lys568 as a selectivity filter that blocks binding of non-NES peptides.

Results

CRM1-bound NESs adopt diverse conformations

We study three NESs that uniquely match the all-helical class 3 pattern (Ф1XXФ2XXXФ3XXФ4). Because most previously studied NESs have substantial helical content, we also study five NESs that match class 2 (Ф1XФ2XXФ3XФ4) and class 1b (Ф1XXФ2XXФ3XФ4) patterns, where the hydrophobic residue positions do not suggest an amphipathic helix (Figure 1A). All eight NESs bind HsCRM1 in the presence of RanGTP with dissociation constants (KDs) of 670 nM-20 μM, and were crystallized bound to the previously described engineered ScCRM1-RanGppNHp-Yrb1p complex (Figure 1—figure supplement 1, Figure 1—source data 1, 2 and 3) (Fung et al., 2015). Details of how the NES peptides were modelled can be found in methods section and in Figure 1—figure supplements 2 and 3. NES-bound CRM1 grooves in the structures (2.1–2.4 Å resolution) resemble the PKINES-bound MmCRM1 groove (Cα/all-atom rmsds 0.5 Å/1.1 Å for 85 groove residues), and all NESs use 4–5 hydrophobic anchor residues to bind P0-P4 hydrophobic pockets of CRM1 (Figures 1D–F and 2) (Güttler et al., 2010).

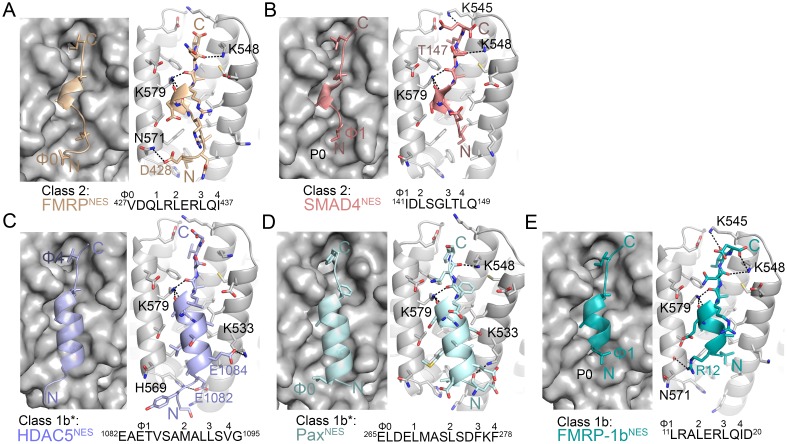

Figure 2. Structures of NESs with non-helical sequence patterns.

(A–E) FMRPNES (light orange), SMAD4NES (salmon), HDACNES (slate), PaxNES (pale cyan) and FMRP-1bNES (deep teal) bound to the ScCRM1 groove. Black dashes show CRM1-NES hydrogen bonds and polar contacts, and unoccupied CRM1 hydrophobic pockets are labeled. *HDAC5NES and PaxNES sequences match the class 1b pattern, but both peptides bind CRM1 using Ф residues that match class 1a pattern. Average displacements of each Φ Cα in the eight NESs (including mDia2NES, CDC7NES, X11L2NES in Figure 1) from the equivalent Φ Cα of PKINES(Ф0L) are 1.3 ± 0.6 (Φ4), 0.8 ± 0.5 (Φ3), 0.7 ± 0.4 (Φ2), 0.9 ± 0.3 (Φ1) and 1.8 ± 0.9 (Φ0) Å.

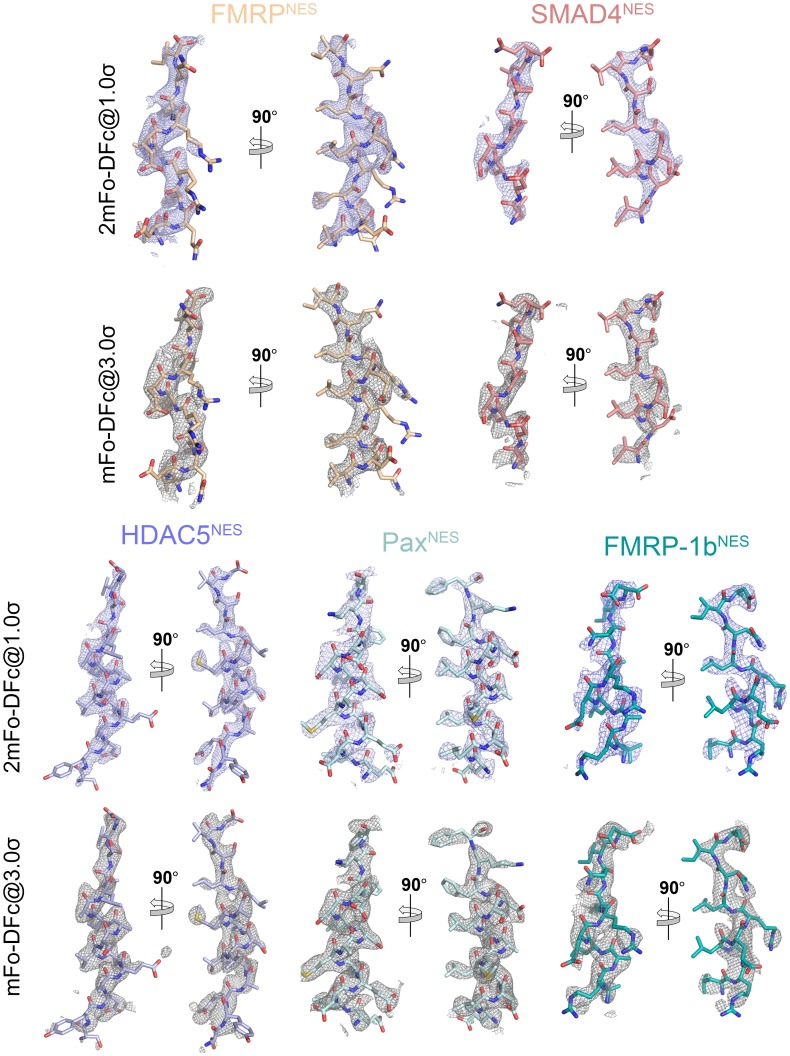

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Electron densities of the NES peptides.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Engineering class 1b NESs.

Class 3 NESs from mouse diaphanous homolog 3 (mDia2NES: 1179SVPEVEALLARLRAL1193) and the cell division cycle 7-related protein kinase (CDC7NES: 456QDLRKLCERLRGMDSSTP473) are indeed all-helix peptides, both forming 3-turn α-helices that occupy only the wide part of the CRM1 groove (Figure 1D,E, Figure 1—figure supplement 4). The last residue of the mDia2 protein (Leu1193) binds the CRM1 P3 pocket leaving the P4 pocket empty. CDC7NES is far from the protein C-terminus but structures of longer peptides suggest that CDC7NESexits the groove after Met468 or Φ3 (Figure 1—figure supplement 5). The mDia2NES and CDC7NESsequence patterns should thus be Φ0XXΦ1XXXΦ2XXΦ3. The Φ4 anchor position is clearly not used in mDia2NES and CDC7NES even though Φ4 is key for activities of several other NESs (Wen et al., 1995; Meyer et al., 1996; Richards et al., 1996; Scott et al., 2002; Tsukahara and Maru, 2004). The number of Φ anchor residues necessary for CRM1 binding can vary between 3–5 (Figure 1—figure supplement 6). A third class 3-matching NES from beta-amyloid binding protein X11L2 (X11L2NES: 55SSLQELVQQFEALPGDLV72) binds differently (Figure 1F, Figure 1—figure supplement 4). 57LQELVQQFEAL67 forms a 3-turn α-helix, 68PGDL71 forms a type I β-turn, and X11L2NES therefore exhibits a new Φ0XXΦ1XXXΦ2XXΦ3XXXΦ4 (class 4) pattern.

Structures of NESs with non-helical patterns are also informative. The previous structure of RevNES (class 2) suggested that its three prolines may constrain against a helical conformation (Figure 1B) (Güttler et al., 2010). Class 2 NESs in the Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 protein (SMAD4NES: 133YERVVSPGIDLSGLTLQ149) and the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRPNES: 423YLKEVDQLRLERLQI437) have few to no prolines but still bind CRM1 with mostly loop-like structures (Figure 2A,B, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC5NES: 1082EAETVSAMALLSVG1095) and Paxillin (PaxNES: 264RELDELMASLSDFKFMAQ281) have NESs with non-α-helical class 1b pattern (Ф1XXФ2XXФ3XФ4), but the peptides bind according to the class 1a pattern instead (Figure 2C,D, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). This left no other experimentally verified NES in the databases that unambiguously match class 1b pattern (Kosugi et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2012c). We engineered a class 1b NES by adding an alanine to FMRPNES (FMRP-1bNES; YLKEVDQLRALERLQID), which forms a short 1.5-turn 310 helix followed by a 3-residue β-strand (Figure 2E, Figure 2—figure supplements 1 and 2). The 310 helix favorably presents Φ1 and Φ2 into the CRM1 groove and natural class 1b NESs are likely to bind similarly.

Structural requirements for an NES

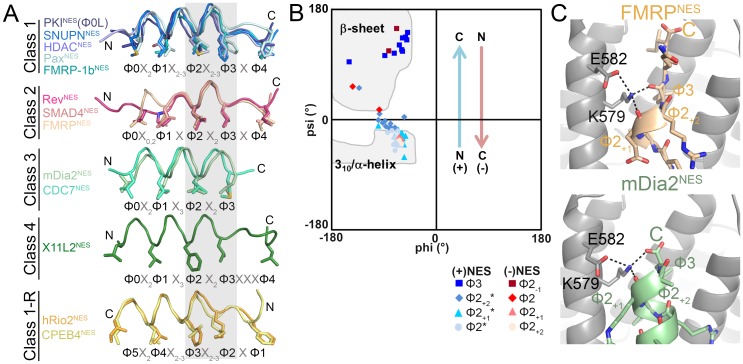

Structures of >13 different CRM1-bound NESs are now available, and may be sorted into five or six groups according to peptide backbone conformations (Figure 3A). Class 1 NESs are helix-strand peptides with either α-helices (class 1a, 1c) or 310 helices (class 1b). Class 1-R NESs are strand-helix peptides, class 2 NESs are mostly loop-like and class 3 NESs are all-helix peptides. The helix-β-turn X11L2NES structure revealed a new Φ0XXΦ1XXXΦ2XXΦ3XXXΦ4 (class 4) pattern.

Figure 3. NESs adopt diverse conformations to bind CRM1, sharing only a small one turn of the helix structural element.

(A) Overlay of 13 different CRM1-bound NESs: mDia2NES, CDC7NES, X11L2NES, FMRPNES, SMAD4NES, HDACNES, PaxNES and FMRP-1bNES, SNUPNNES (3GB8), PKINES(Φ0L) (3NBY), RevNES (3NBZ), hRio2NES (5DHF), CPEB4NES (5DIF) (shown as ribbons with Φ residues in sticks; their CRM1 H12A helices were superimposed). A grey rectangle highlights the only secondary structural element shared by all 13 NESs: a single turn of helix. (B) Ramachandran plot of phi/psi angles of the four residues in each of the conserved one-turn of helix. Arrows indicate changes in psi angles along the polypeptide direction. For example, (+) HDAC5NES: Φ2 Ψ = −43.5°, Φ2+1Ψ = −21.7°, Φ2+2Ψ = −1.3°, Φ3 Ψ = 133.8° and (−) CPEB4NES: Φ2+2Ψ = −40.2°, Φ2+1Ψ = −31.0°, Φ2 Ψ = 16.5°, Φ2-1Ψ = 111.5°. *Residues in SNUPNNES plotted are Φ2+1, Φ2+2, Φ2+3 and Φ3. (C) Detailed view of niche motifs in (+) NESs, FMRPNES and mDia2NES.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. NES main chain hydrogen bonds with ScCRM1 Lys579 in (−) NESs.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. The Lys568 of HsCRM1 is important for NES binding.

The only common secondary structural element in the NES structures is one turn of NES helix at Φ2X2-3Φ3 (grey box, Figure 3A). This conserved turn of helix is flanked on one side by additional turns of helix (classes 1, 1-R) or by loops (class 2), and on the other side by β-strands (classes 1, 1-R, 2) or β-turn (class 4), or the helix ends as the chain terminates or exits the groove (class 3) (Figure 3A). Dihedral (psi) angles in the 1-turn of helix gradually increase in progression from helical to β-strand conformations (Figure 3B).

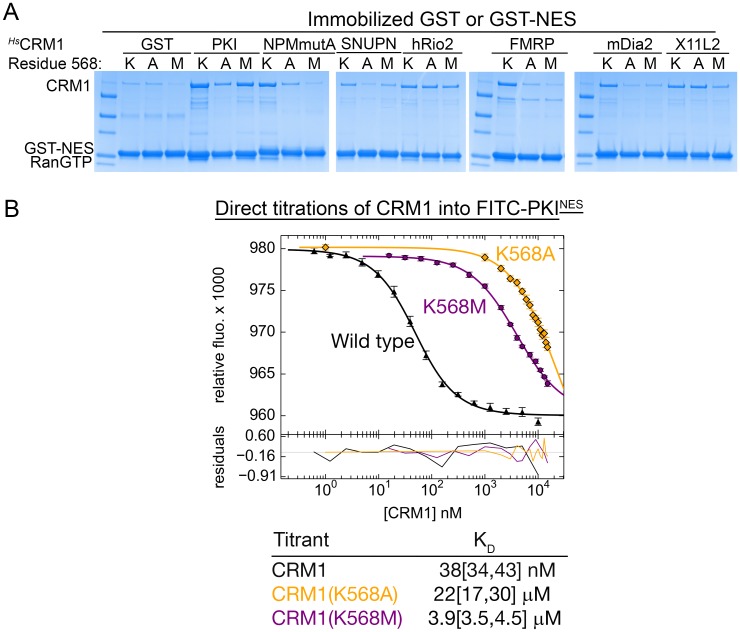

In all (+) NESs, main chain carbonyls of Φ2+1 and Φ3 residues in the 1-turn helix element hydrogen bonds with the ScCRM1 Lys579 (or MmCRM1/HsCRM1 Lys568) side chain, much like niche3/4 motifs where carbonyls of residues i and i + 2 or i + 3 coordinate a cationic group (Torrance et al., 2009). The Φ3-Lys579 hydrogen bond is possible only because the β-strand psi angle turns Φ3 carbonyl towards Lys579 (Figure 3C). NES helix-Lys579 hydrogen bonds are absent in (−) NESs as backbone carbonyls point in the opposite direction. Here, carbonyls of the N-terminal β-strand hydrogen bond with Lys579 (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Therefore, another common structural feature of NESs is hydrogen bonding between NES backbone and ScCRM1 Lys579 (HsCRM1 Lys568). Mutations of HsCRM1 Lys568 impair NES binding. Mutants HsCRM1(K568A) and HsCRM1(K568M) bind FITC-PKINES two to three orders of magnitude weaker than wild type HsCRM1, supporting the importance of Lys568-NES interactions (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

In summary, an active NES (1) can use many different backbone conformations to present 3–5 hydrophobic anchor residues into 3–5 CRM1 hydrophobic pockets (P0 and/or P4 are sometimes not used), (2) has one turn of helix with helix-strand transition that binds the central portion of the CRM1 groove and (3) has backbone conformation that can hydrogen bond with Lys568 of HsCRM1.

HsCRM1 Lys568 is a selectivity filter for NES recognition

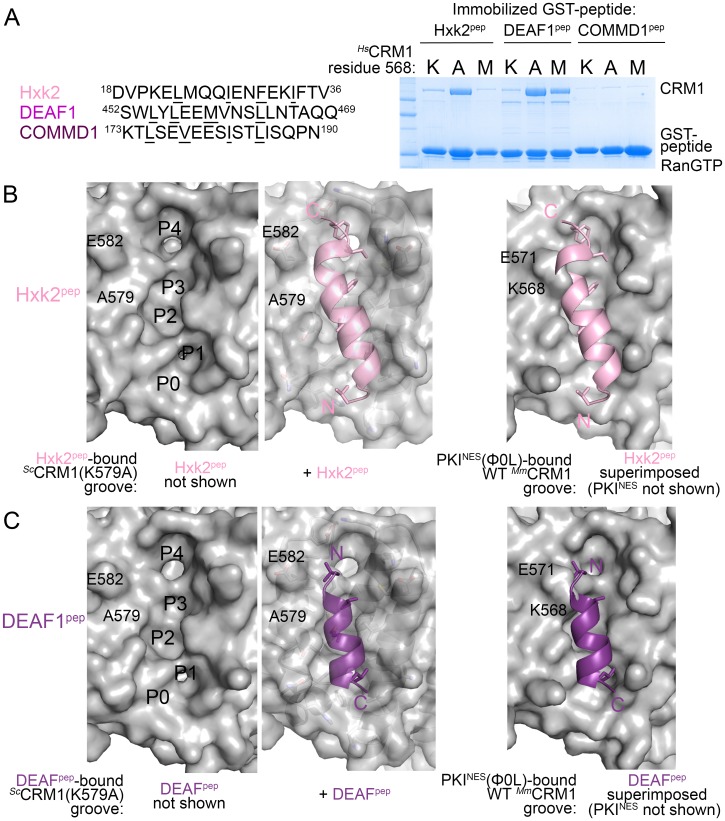

What then are CRM1 groove features that selectively recognize the key NES features? Arrangement of hydrophobic pockets in the groove likely selects NESs with suitably placed Φ residues. Groove shape, tapering and most constricted at ScCRM1 Lys579 (HsCRM1 Lys568), likely selects for NES helices that transition to strands or NES helices that end (Figure 3C). Is groove-constricting HsCRM1 Lys568 perhaps key for differentiating active from false positive NES sequences? We tested mutants HsCRM1(K568A) and HsCRM1(K568M) for interactions with three previously identified false positive NESs that match NES consensus but do not bind CRM1: peptides from Hexokinase-2 (Hxk2pep: 18DVPKELMQQIENFEKIFTV36, class 3 match), Deformed Epidermal Autoregulatory Factor 1 homolog (DEAF1pep:452SWLYLEEMVNSLLNTAQQ469; class 1a-R match) and COMM domain-containing protein 1 (COMMD1pep; 173KTLSEVEESISTLISQPN190; class 3 match) (Figure 4A) (Xu et al., 2012c, 2015). Wild type HsCRM1 does not bind the peptides but HsCRM1(K568A) binds Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep, and HsCRM1(K568M) binds DEAF1pep but not Hxk2pep, suggesting that Lys568 is important in filtering out false positive NESs (Figure 4A).

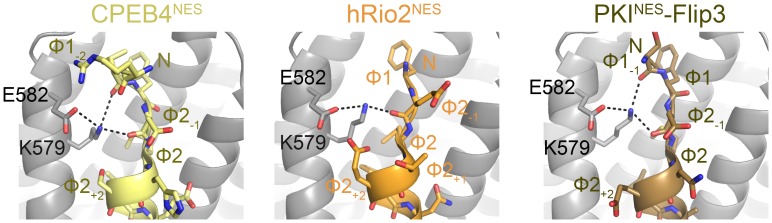

Figure 4. HsCRM1 Lys568 is a selectivity filter.

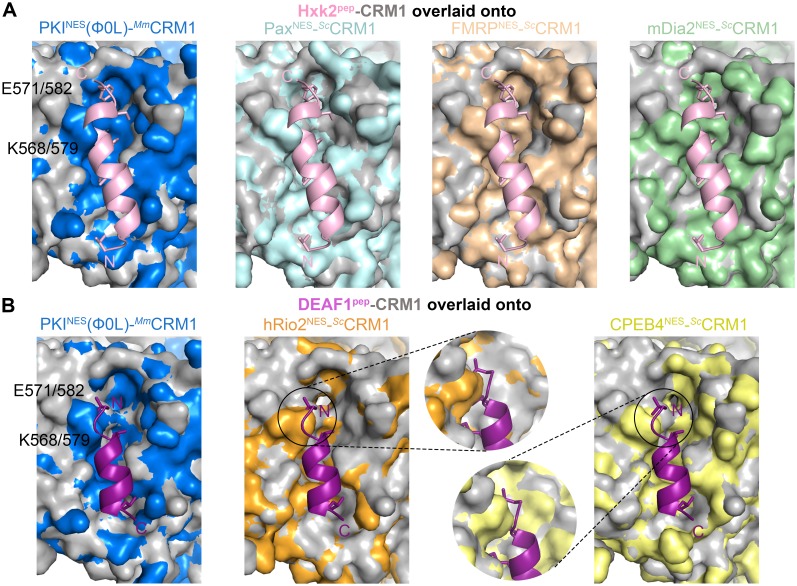

(A) False positive NES sequences with Φ residues of consensus matches underlined. Pull-down binding assay of ~5 µg immobilized GST-NESs and 7.5 µM ScRanGTP with 2.5 µM of either wild type HsCRM1 or mutant HsCRM1(K568A) or HsCRM1(K568M) in 200 µL reactions. (C–D) Structures of Hxk2pep (pink) (C) and DEAF1pep (purple) (D) bound to ScCRM1(K579A). Left panels, peptides were removed to show the surface of the mutant ScCRM1(K579A) groove. Middle panels, peptides bound to the mutant ScCRM1(K579A). Right panels, CRM1(K579A)-bound Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep superimposed onto the PKINES(Ф0L)-bound MmCRM1 groove (3NBY; CRM1 H12A helices were aligned; PKINES not shown) to show steric clash of the Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep peptides with the MmCRM1 Lys568 side chain.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.23961.018

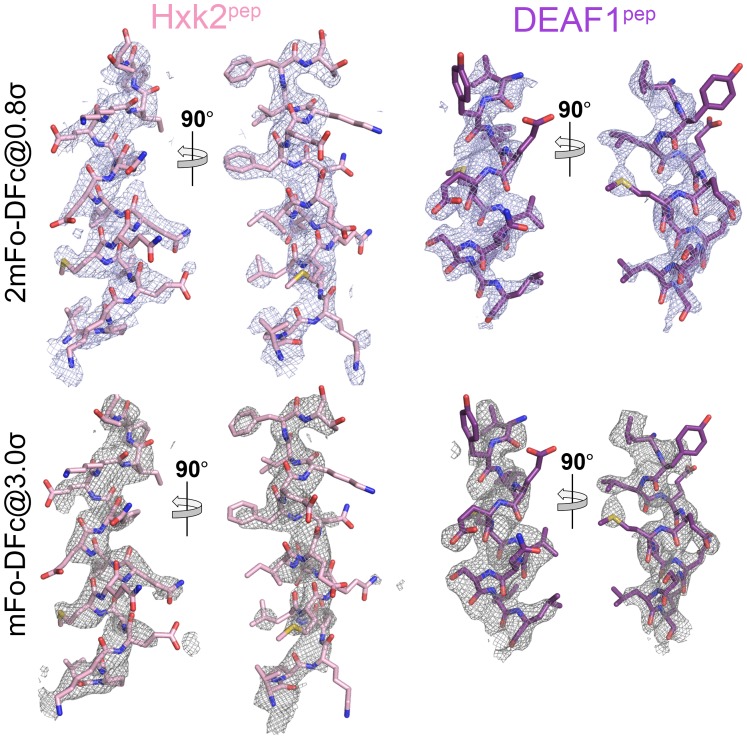

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Electron densities of the HXK2pep and DEAFpep false positive NES peptides bound to the ScCRM1(K579A) mutant.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. Additional overlays of Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep onto NES-bound wild type CRM1 grooves.

Both ScCRM1(K579A)-bound Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep are all-helix peptides (Figure 4B,C, Figure 4—figure supplement 1, Figure 4—source data 1). The fourth turn of the Hxk2pep helix packs into hydrophobic space widened by removal and rearrangement of the Lys579 and Glu582 side chains, respectively (Figure 4B). The 2.5-turn α-helix of DEAF1pepbinds in the (−) direction and is slightly longer than helices in true (−) NESs (Figure 4C). Superpositions of Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep onto wild type CRM1 grooves show the fourth turn of the Hxk2pep helix and the N-terminus of the DEAF1pep helix clashing with ScCRM1 Lys579/MmCRM1 Lys568 side chains (Figure 4B,C, Figure 4—figure supplement 2). The rest of the mutant ScCRM1(K579A) groove is highly similar to the wild type groove. Therefore, the key feature of the wild type groove that prevents Hxk2pep and DEAF1pep binding is Lys568, which is not only a critical hydrogen bond donor for binding NESs, but its long side chain also blocks binding of sequences that do not meet NES structural requirements.

Discussions

Class 1a, 1b, 1c, 2, 3, 4 and 1a-R NES structures show 5–6 distinct backbone conformations that match their respective hydrophobic sequence patterns. We can infer structures of remaining NES classes: class 1d NESs (Ф1XXФ2XXXФ3XФ4) are likely α-helix-strand and other (−) NES classes are likely the reverse of their (+) counterparts. Symmetrical class 2, 3 and 4 patterns are identical in both (+)/(−) directions but (−) class 3 and 4 NESs, lacking β-strands to hydrogen bond with HsCRM1 Lys568, may not be ideal NESs.

Structures of many diverse NES sequences suggest how one unchanging peptide-bound CRM1 groove can recognize up to a thousand different peptides. Dependence of 3–5 hydrophobic residues in 8–15 residues-long NES arises from the substantial binding energy of anchor hydrophobic side chains interacting with 3–5 CRM1 hydrophobic pockets. However, lack of contact with NES backbone allows anchor side chains to be presented in many conformations including both N- to C-terminal orientations, explaining broad specificity defined by highly variable spacings between anchors. Interestingly, NES conformation is not entirely unrestrained, as CRM1 groove constriction imposes either exit/termination of the NES chain or its continuation in extended configuration. Solutions for the broadly specific NES recognition contrast with those of analogous systems. MHC I and II proteins, each recognizing at least hundreds of different peptide antigens, use many peptide main chain contacts for affinity with only a few supplementary peptide side chain interactions (Zhang et al., 1998; Madden, 1995). The result here is a conformational selection of particular lengths of extended peptides binding in conserved N- to C-terminal orientation, with little sequence restriction. The Calmodulin-helical peptide system is yet another contrast, as the binding domain uses its flexible fold to adapt to various helical ligands (Tidow and Nissen, 2013; Hoeflich and Ikura, 2002).

CRM1-NES structures expanded the six NES patterns derived from peptide library studies to the eleven patterns shown in Figures 1A and 3A. The ever-expanding set of NES patterns suggests that no fixed hydrophobic pattern likely describes the NES. Furthermore, only ~50% of consensus-matching previously reported NESs that were tested actually bound CRM1, contributing to the inefficiency of available NES predictors (with precision of 50% at 20% recall rate) (Xu et al., 2012b, 2015; Kosugi et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2011). The many available NES structures, diversity of NES conformations and the structurally conserved one-turn helix NES element revealed here will enable development of structure- rather than sequence-based NES predictors (Raveh et al., 2011; Schindler et al., 2015; Trellet et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2016). There is a need to identify many more CRM1 cargoes as apoptosis of different cancer cells upon CRM1 inhibition by the drug Selinexor (in clinical trials for a variety of cancers) and other inhibitors (Parikh et al., 2014; Mendonca et al., 2014; Das et al., 2015; Alexander et al., 2016; Gounder et al., 2016; Abdul Razak et al., 2016; Lapalombella et al., 2012; Inoue et al., 2013; Etchin et al., 2013; Tai et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016; Hing et al., 2016; Vercruysse et al., 2016) appears to be driven by nuclear accumulation of different sets of NES-containing cargoes, but identities of most of these apoptosis-causing cargoes are still unknown.

Finally, we find that the HsCRM1 Lys568 side chain acts as a filter that physically selects for NESs with helices that transition to strands or end at the narrow part of the CRM1 groove. Interestingly, Lys568 interacts electrostatically with HsCRM1 Glu571, which is mutated to glycine or lysine in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphomas with poor prognosis (Puente et al., 2011; Jardin et al., 2016; Camus et al., 2016). Disease mutations will abolish Glu571-Lys568 contacts and possibly affect NES binding and selectivity.

Materials and methods

Crystallization of CRM1-Ran-RanBP1-NES complexes

CRM1 (ScCRM1 residues 1–1058, △377–413, 537DLTVK541 to GLCEQ, V441D), Yrb1p (yeast RanBP1 residues 62–201), human Ran full length and various NESs were expressed and purified as described in Fung et al. (Fung et al., 2015). CRM1 (K579A) mutant was expressed in pGex-TEV and purified like CRM1. Crystallization, data collection and processing, and solving of the structures were also performed in the same manner as previously described. X-ray/stereochemistry weight and X-ray/ADP weight were both optimized by phenix.refine in PHENIX (RRID:SCR_014224).

NES peptides are modeled according to the positive difference density (2mFo-DFc map) at the binding groove after refinement of the CRM1-Ran-RanBP1 model. In all structures, there are good electron densities for the NES main chain and directions of side chain density in the helical portion of the peptides allow unambiguous determination that they are all oriented in the positive (+) NES orientation. Side chain assignments of the NES peptides are guided by (1) densities of Ф side chains that point into the binding groove, (2) densities for long non-Ф side chains such as arginine, phenylalanine and methionine and (3) physical considerations such as steric clashes.

For example, to model the bound mDia2NES peptide (sequence: GGSY-1179SVPEVEALLARLRAL1193), we made use of the obvious electron densities (mFo-DFc map) for long side chains to guide sequence assignment. There is a strong side chain density suitable for an arginine side chain on the peptide (white dashed circle in Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). There are only two arginine residues in the mDia2NES peptide, Arg1189 and Arg1191. If the long side chain density is assigned to Arg1189, then Arg1191 would end up pointing into the binding groove – a very energetically unfavorable and unlikely situation. Furthermore, Ala1188 would end up in the P2 pocket of CRM1 where there is an obvious density for a longer hydrophobic side chain (left panel, Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). On the other hand, when Arg1191 is assigned to the long and continuous side chain density (adjacent to helix H12A of CRM1), the remaining side chains in the NES end up in positions that are consistent the electron densities.

For the FMRP-1bNES (sequence: 1GGS-YLKEVDQLRALERLQID20), there are no obvious long side chain densities that could help with modeling. There are however obvious densities for several side chains in the first two turn of the NES helix. These side chain densities are consistent with two possible sequence assignments: 5LKEVDQLRAL14 or the more C-terminal 11LRALERLQID20. We tested modeling of FMRP-1bNES by refining both peptide models and by testing a mutant peptide that should distinguish between the two models. Ten cycles of PHENIX refinement of the 5LKEVDQLRAL14 model resulted in positive and negative difference densities (mFo-DFc map) at several NES side chains, which suggested an incorrect assignment (left panels, Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). In contrast, different densities are absent when the 11LRALERLQID20 model is refined (right panels, Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). The final FMRP-1bNES structure was therefore modelled as 11LRALERLQID20. The sequence assignment of FMRP-1bNES was also tested using a mutant FMRP-1bNES that has the sequence YLKEVDQLRALER. If the NES is 5LKEVDQLRAL14, FMRP-1bNES mutant YLKEVDQLRALER should bind well to CRM1. However, if 11LRALERLQID20 is the FMRP-1bNES, mutant YLKEVDQLRALER should not bind CRM1 as the C-terminal half of the NES or 17LQID20 which includes Ф3 and Ф4 is missing. Results in Figure 1—figure supplement 3 show that FMRP-1bNES mutant YLKEVDQLRALER does not bind CRM1, providing further support that the NES is indeed 11LRALERLQID20 as currently assigned.

NES activity assays

Pull-down binding assays, in vivo NES activity assay and differential bleaching experiments for determining binding affinities were all performed the same way as described in Fung et al. (2015). The data were analyzed in PALMIST (Scheuermann et al., 2016) and plotted with GUSSI (Brautigam, 2015).

Accession codes

Structures and crystallographic data have been deposited at the PDB: 5UWI (CRM1-HDAC5NES), 5UWH (CRM1-PaxNES), 5UWO (CRM1-FMRP-1bNES), 5UWJ (CRM1-FMRPNES), 5UWU (CRM1-SMAD4NES) 5UWP (CRM1-mDia2NES), 5UWQ (CRM1-CDC7NES), 5UWR (CRM1-CDC7NES ext), 5UWS (CRM1-X11L2NES), 5UWT (CRM1(K579A)-Hxk2pep), 5UWW (CRM1(K579A)-DEAF1pep).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Structural Biology Laboratory and Macromolecular Biophysics Resource at UTSW for their assistance with crystallographic and biophysical data collection. Results shown in this report are derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. Ho Yee Joyce Fung is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow. This work was funded by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Grants RP120352 and RP150053 (YMC), R01 GM069909 (YMC), the Welch Foundation Grant I-1532 (YMC), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar Award (YMC), the University of Texas Southwestern Endowed Scholars Program (YMC), and a Croucher Foundation Scholarship (HYJF).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow to Ho Yee Joyce Fung.

Croucher Foundation Graduate Student Scholarship to Ho Yee Joyce Fung.

Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas RP120352 to Yuh Min Chook.

Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas RP150053 to Yuh Min Chook.

National Institutes of Health R01 GM069909 to Yuh Min Chook.

Welch Foundation I-1532 to Yuh Min Chook.

Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar Award to Yuh Min Chook.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Endowed Scholars Program to Yuh Min Chook.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

HYJF, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

S-CF, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology.

YMC, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Additional files

Major datasets

The following datasets were generated:

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of HDAC5 NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWI,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWI)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of Paxillin NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWH,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWH)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of Engineered FMRP-1b NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWO,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWO)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of FMRP NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWJ,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWJ)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of SMAD4 NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWU,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWU)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of mDia2 NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWP,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWP)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of CDC7 NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWQ,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWQ)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of CDC7 NES Peptide (extended) in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWR,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWR)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of X11L2 NES Peptide in complex with CRM1-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWS,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWS)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of Hxk2 Peptide in complex with CRM1 K579A mutant-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWT,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWT)

Ho Yee Joyce Fung,Yuh Min Chook,2017,Crystal Structure of DEAF1 Peptide in complex with CRM1 K579A mutant-Ran-RanBP1,www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=5UWW,Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5UWW)

References

- Abdul Razak AR, Mau-Soerensen M, Gabrail NY, Gerecitano JF, Shields AF, Unger TJ, Saint-Martin JR, Carlson R, Landesman Y, McCauley D, Rashal T, Lassen U, Kim R, Stayner LA, Mirza MR, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Mahipal A. First-in-class, first-in-human phase I study of Selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear export, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:4142–4150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander TB, Lacayo NJ, Choi JK, Ribeiro RC, Pui CH, Rubnitz JE. Phase I study of selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear export, in combination with fludarabine and cytarabine, in pediatric relapsed or refractory acute leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:4094–4101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd HP, Fridell RA, Benson RE, Hua J, Cullen BR. Protein sequence requirements for function of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 rex nuclear export signal delineated by a novel in vivo randomization-selection assay. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1996;16:4207–4214. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.8.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam CA. Calculations and Publication-Quality illustrations for analytical ultracentrifugation data. Methods in Enzymology. 2015;562:109–133. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus V, Stamatoullas A, Mareschal S, Viailly PJ, Sarafan-Vasseur N, Bohers E, Dubois S, Picquenot JM, Ruminy P, Maingonnat C, Bertrand P, Cornic M, Tallon-Simon V, Becker S, Veresezan L, Frebourg T, Vera P, Bastard C, Tilly H, Jardin F. Detection and prognostic value of recurrent exportin 1 mutations in tumor and cell-free circulating DNA of patients with classical hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica. 2016;101:1094–1101. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Holloway MP, Nguyen K, McCauley D, Landesman Y, Kauffman MG, Shacham S, Altura RA. XPO1 (CRM1) inhibition represses STAT3 activation to drive a survivin-dependent oncogenic switch in triple-negative breast Cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2014;13:675–686. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Wei G, Parikh K, Liu D. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINE) in hematological malignancies. Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s40164-015-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Biswas A, Süel KE, Jackson LK, Martinez R, Gu H, Chook YM. Structural basis for leucine-rich nuclear export signal recognition by CRM1. Nature. 2009;458:1136–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchin J, Sanda T, Mansour MR, Kentsis A, Montero J, Le BT, Christie AL, McCauley D, Rodig SJ, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Stone R, Letai A, Kung AL, Thomas Look A. KPT-330 inhibitor of CRM1 (XPO1)-mediated nuclear export has selective anti-leukaemic activity in preclinical models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2013;161:117–127. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj IW. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SC, Imai K, Horton P. Prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signal containing proteins with NESsential. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:e111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Asano S, Nakamura T, Adachi M, Yoshida M, Yanagida M, Nishida E. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997;390:308–311. doi: 10.1038/36894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung HY, Fu SC, Brautigam CA, Chook YM. Structural determinants of nuclear export signal orientation in binding to exportin CRM1. eLife. 2015;4:10034. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounder MM, Zer A, Tap WD, Salah S, Dickson MA, Gupta AA, Keohan ML, Loong HH, D'Angelo SP, Baker S, Condy M, Nyquist-Schultz K, Tanner L, Erinjeri JP, Jasmine FH, Friedlander S, Carlson R, Unger TJ, Saint-Martin JR, Rashal T, Ellis J, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Schwartz GK, Abdul Razak AR. Phase IB study of selinexor, a First-in-Class inhibitor of nuclear export, in patients with advanced refractory bone or soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:3166–3174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güttler T, Madl T, Neumann P, Deichsel D, Corsini L, Monecke T, Ficner R, Sattler M, Görlich D. NES consensus redefined by structures of PKI-type and Rev-type nuclear export signals bound to CRM1. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2010;17:1367–1376. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing ZA, Fung HY, Ranganathan P, Mitchell S, El-Gamal D, Woyach JA, Williams K, Goettl VM, Smith J, Yu X, Meng X, Sun Q, Cagatay T, Lehman AM, Lucas DM, Baloglu E, Shacham S, Kauffman MG, Byrd JC, Chook YM, Garzon R, Lapalombella R. Next-generation XPO1 inhibitor shows improved efficacy and in vivo tolerability in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2016;30:2364–2372. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich KP, Ikura M. Calmodulin in action: diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell. 2002;108:739–742. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Landesman Y, Yang J, Evans CP, Weiss RH. CRM1 blockade by selective inhibitors of nuclear export attenuates kidney Cancer growth. The Journal of Urology. 2013;189:2317–2326. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin F, Pujals A, Pelletier L, Bohers E, Camus V, Mareschal S, Dubois S, Sola B, Ochmann M, Lemonnier F, Viailly PJ, Bertrand P, Maingonnat C, Traverse-Glehen A, Gaulard P, Damotte D, Delarue R, Haioun C, Argueta C, Landesman Y, Salles G, Jais JP, Figeac M, Copie-Bergman C, Molina TJ, Picquenot JM, Cornic M, Fest T, Milpied N, Lemasle E, Stamatoullas A, Moeller P, Dyer MJ, Sundstrom C, Bastard C, Tilly H, Leroy K. Recurrent mutations of the exportin 1 gene (XPO1) and their impact on selective inhibitor of nuclear export compounds sensitivity in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. American Journal of Hematology. 2016;91:923–930. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kırlı K, Karaca S, Dehne HJ, Samwer M, Pan KT, Lenz C, Urlaub H, Görlich D. A deep proteomics perspective on CRM1-mediated nuclear export and nucleocytoplasmic partitioning. eLife. 2015;4:11466. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, McMillan E, Kim HS, Venkateswaran N, Makkar G, Rodriguez-Canales J, Villalobos P, Neggers JE, Mendiratta S, Wei S, Landesman Y, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Chow CB, Frink RE, Gao B, Roth M, Minna JD, Daelemans D, Wistuba II, Posner BA, Scaglioni PP, White MA. XPO1-dependent nuclear export is a druggable vulnerability in KRAS-mutant lung Cancer. Nature. 2016;538:114–117. doi: 10.1038/nature19771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H. Nuclear export signal consensus sequences defined using a localization-based yeast selection system. Traffic. 2008;9:2053–2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S, Yanagawa H, Terauchi R, Tabata S. NESmapper: accurate prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals using activity-based profiles. PLoS Computational Biology. 2014;10:e1003841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- la Cour T, Kiemer L, Mølgaard A, Gupta R, Skriver K, Brunak S. Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2004;17:527–536. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapalombella R, Sun Q, Williams K, Tangeman L, Jha S, Zhong Y, Goettl V, Mahoney E, Berglund C, Gupta S, Farmer A, Mani R, Johnson AJ, Lucas D, Mo X, Daelemans D, Sandanayaka V, Shechter S, McCauley D, Shacham S, Kauffman M, Chook YM, Byrd JC. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export show that CRM1/XPO1 is a target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:4621–4634. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-429506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DR. The three-dimensional structure of peptide-MHC complexes. Annual Review of Immunology. 1995;13:587–622. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca J, Sharma A, Kim HS, Hammers H, Meeker A, De Marzo A, Carducci M, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Kachhap S. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINE) as novel therapeutics for prostate Cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:6102–6112. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BE, Meinkoth JL, Malim MH. Nuclear transport of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, visna virus, and equine infectious Anemia virus rev proteins: identification of a family of transferable nuclear export signals. Journal of Virology. 1996;70:2350–2359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2350-2359.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monecke T, Güttler T, Neumann P, Dickmanns A, Görlich D, Ficner R. Crystal structure of the nuclear export receptor CRM1 in complex with Snurportin1 and RanGTP. Science. 2009;324:1087–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.1173388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossareh-Nazari B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh K, Cang S, Sekhri A, Liu D. Selective inhibitors of nuclear export (SINE)--a novel class of anti-cancer agents. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2014;7:78. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, Conde L, Ordóñez GR, Villamor N, Escaramis G, Jares P, Beà S, González-Díaz M, Bassaganyas L, Baumann T, Juan M, López-Guerra M, Colomer D, Tubío JM, López C, Navarro A, Tornador C, Aymerich M, Rozman M, Hernández JM, Puente DA, Freije JM, Velasco G, Gutiérrez-Fernández A, Costa D, Carrió A, Guijarro S, Enjuanes A, Hernández L, Yagüe J, Nicolás P, Romeo-Casabona CM, Himmelbauer H, Castillo E, Dohm JC, de Sanjosé S, Piris MA, de Alava E, San Miguel J, Royo R, Gelpí JL, Torrents D, Orozco M, Pisano DG, Valencia A, Guigó R, Bayés M, Heath S, Gut M, Klatt P, Marshall J, Raine K, Stebbings LA, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Gut I, López-Guillermo A, Estivill X, Montserrat E, López-Otín C, Campo E. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveh B, London N, Zimmerman L, Schueler-Furman O. Rosetta flexpepdock ab-initio: simultaneous folding, docking and refinement of peptides onto their receptors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SA, Lounsbury KM, Carey KL, Macara IG. A nuclear export signal is essential for the cytosolic localization of the ran binding protein, RanBP1. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:1157–1168. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann TH, Padrick SB, Gardner KH, Brautigam CA. On the acquisition and analysis of microscale thermophoresis data. Analytical Biochemistry. 2016;496:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CE, de Vries SJ, Zacharias M. Fully blind Peptide-Protein docking with pepATTRACT. Structure. 2015;23:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MG, Le Rouzic E, Périanin A, Pierotti V, Enslen H, Benichou S, Marullo S, Benmerah A. Differential nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of beta-arrestins. characterization of a leucine-rich nuclear export signal in beta-arrestin2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:37693–37701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stade K, Ford CS, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YT, Landesman Y, Acharya C, Calle Y, Zhong MY, Cea M, Tannenbaum D, Cagnetta A, Reagan M, Munshi AA, Senapedis W, Saint-Martin JR, Kashyap T, Shacham S, Kauffman M, Gu Y, Wu L, Ghobrial I, Zhan F, Kung AL, Schey SA, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Anderson KC. CRM1 inhibition induces tumor cell cytotoxicity and impairs osteoclastogenesis in multiple myeloma: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Leukemia. 2014;28:155–165. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakar K, Karaca S, Port SA, Urlaub H, Kehlenbach RH. Identification of CRM1-dependent nuclear export cargos using quantitative mass spectrometry. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2013;12:664–678. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidow H, Nissen P. Structural diversity of calmodulin binding to its target sites. FEBS Journal. 2013;280:5551–5565. doi: 10.1111/febs.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrance GM, Leader DP, Gilbert DR, Milner-White EJ. A novel main chain motif in proteins bridged by cationic groups: the niche. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;385:1076–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trellet M, Melquiond AS, Bonvin AM. A unified conformational selection and induced fit approach to protein-peptide docking. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara F, Maru Y. Identification of novel nuclear export and nuclear localization-related signals in human heat shock cognate protein 70. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:8867–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse T, De Bie J, Neggers JE, Jacquemyn M, Vanstreels E, Schmid-Burgk JL, Hornung V, Baloglu E, Landesman Y, Senapedis W, Shacham S, Dagklis A, Cools J, Daelemans D. The second-generation exportin-1 inhibitor KPT-8602 demonstrates potent activity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W, Meinkoth JL, Tsien RY, Taylor SS. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell. 1995;82:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Farmer A, Collett G, Grishin NV, Chook YM. Sequence and structural analyses of nuclear export signals in the NESdb database. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012b;23:3677–3693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-01-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Farmer A, Collett G, Grishin NV, Chook YM. Sequence and structural analyses of nuclear export signals in the NESdb database. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012c;23:3677–3693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-01-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Grishin NV, Chook YM. NESdb: a database of NES-containing CRM1 cargoes. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012a;23:3673–3676. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-01-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Marquis K, Pei J, Fu SC, Cağatay T, Grishin NV, Chook YM. LocNES: a computational tool for locating classical NESs in CRM1 cargo proteins. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1357–1365. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C, Xu X, Zou X. Fully blind docking at the atomic level for Protein-Peptide complex structure prediction. Structure. 2016;24:1842–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Anderson A, DeLisi C. Structural principles that govern the peptide-binding motifs of class I MHC molecules. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998;281:929–947. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]