Abstract

Objectives

To elucidate any potential association between α-synuclein pathology and cognitive impairment, and to determine the profile of cognitive impairment in multiple system atrophy (MSA) patients, we analyzed the clinical and pathologic features in autopsy-confirmed MSA patients.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed medical records, including neuropsychological test data, in 102 patients with autopsy-confirmed MSA in the Mayo Clinic brain bank. The burden of glial cytoplasmic inclusions and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions were semi-quantitatively scored in the limbic regions and middle frontal gyrus. We also assessed concurrent pathologies potentially causing dementia including Alzheimer disease, hippocampal sclerosis, and cerebrovascular pathology.

Results

Of 102 patients, 33 (32%) patients were documented with cognitive impairment. Those that received objective testing, deficits primarily in processing speed and attention/executive functions were identified, which suggests a frontal-subcortical pattern of dysfunction. Of these 33 patients with cognitive impairment, eight patients had concurrent pathologies of dementia. MSA patients with cognitive impairment had a greater burden of neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the dentate gyrus than patients without cognitive impairment, both including and excluding patients with concurrent pathologies of dementia.

Conclusions

The cognitive deficits observed in this study were more evident on neuropsychological assessment compared to cognitive screens. Based on these findings, we recommend that clinicians consider more in-depth neuropsychological assessments if patients with MSA present with cognitive complaints. Although we did not identify the correlation between cognitive deficits and responsible neuroanatomical regions, greater burden of neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the limbic regions was associated with cognitive impairment in MSA.

Introduction

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is an atypical parkinsonian disorder characterized by a variable combination of autonomic failure, parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia, and pyramidal symptoms.1, 2 Pathologically, glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs), the pathologic hallmark of MSA, are found throughout the brain, especially in striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems. Unlike other α-synucleinopathies such as Parkinson disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), dementia (as defined by DSM-IV criteria) is not a feature that supports a clinical diagnosis of MSA. A recent position statement by the Neuropsychology Task Force of the Movement Disorders Society MSA study group indicates that cognitive impairment (CI) may be an under-recognized feature in MSA. The frequency of CI ranges from 22 to 37% in autopsy-confirmed MSA.2, 5–7 These patients showed a wide spectrum of CI; frontal executive function was most frequently affected, while attention, memory, and visuospatial domains are sometimes impaired.4, 8

The neuropathological underpinnings of CI in MSA are not well defined. Asi et al. reported no significant difference in GCIs and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCIs) burden in limbic or cortices regions between MSA with CI (MSA-CI) and those without CI (MSA-NC). Recent studies, however, have shown that NCIs rather than GCIs in neocortex or limbic regions are associated with CI in MSA.5, 7 MSA patients which showed clinical presentations of frontotemporal dementia syndrome had severe limbic NCI.10, 11

The aims of this study were to determine whether the severity of α-synuclein pathology was associated with CI in MSA and to clarify the profile of CI in MSA. To accomplish our aims, we retrospectively reviewed medical records, including neuropsychological evaluations, and semi-quantitatively assessed the burden of GCI and NCI in autopsy-confirmed MSA. To exclude the influence of concurrent pathologies of dementia, we also assessed Alzheimer-related pathology, hippocampal sclerosis (HpScl), and cerebrovascular pathology.

Methods

Subjects

Between 1998 and 2015, 170 patients from the Mayo Clinic brain bank were given a neuropathologic diagnosis of MSA. Of those, 40 patients without any medical records or brain bank questionnaires, 16 patients with only brain bank questionnaires, and 12 patients with medical records evaluated by physicians other than neurologists were excluded from the study. The resulting cohort consisted of 102 patients having medical records with assessments by neurologists or movement disorder specialists. The mean number of medical records available for review was 10.4 (SD = 11.1) in each patient. These cases were received from the following sources: CurePSP: Society for PSP | CBD and Related Disorders (N = 65), Mayo Clinic Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for PD (N = 30), consultation cases (N = 4), Mayo Clinic Jacksonville Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Research Center (N = 1), State of Florida AD Initiative (N = 1), and Mayo Clinic Jacksonville hospital autopsy case (N = 1). Some of the data on these patients have been presented in previous articles.6, 12 All brain autopsies were performed with the consent of the legal next-of-kin or an individual with power-of-attorney for the patients. Studies using these autopsy samples were considered exempt from human subject research by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Clinical Assessment

Pertinent clinical information derived from the available records or brain bank questionnaires that were filled out by a close family member included sex, age at symptomatic onset, assessment, and death, clinical diagnoses, family history of dementia and parkinsonism, clinical symptoms, and results from cognitive screening measures and neuropsychological assessments. The presence of CI was classified using two methods. The first method involved reviewing records for diagnostic impressions of clinicians or patient symptom self-report of impairment. Common subjective indicators of CI included memory loss, forgetfulness, distractibility, word finding difficulty, difficulty with naming, slowed thinking/bradyphrenia, and executive dysfunction. The second method involved reviewing test scores documented in the record from either cognitive screening tests (e.g., the Mini Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status), or test scores from comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations. The presence of impairment on neuropsychological tests was classified utilizing cutoff scores (>1.5 SD below the normative mean) commonly accepted in the neuropsychology literature. Patients were considered to have depression if a diagnosis of depression was documented, and the patient was prescribed an antidepressant medication as a primary treatment of depressive symptoms. Symptom onset was defined as the initial presentation of any motor symptom (i.e. parkinsonism or cerebellar ataxia) or selected autonomic features (i.e. orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence, or urinary retention). Based on clinical information, each patient was assigned a clinical subtype: MSA with predominant parkinsonism (MSA-P) or MSA with predominant cerebellar ataxia (MSA-C).

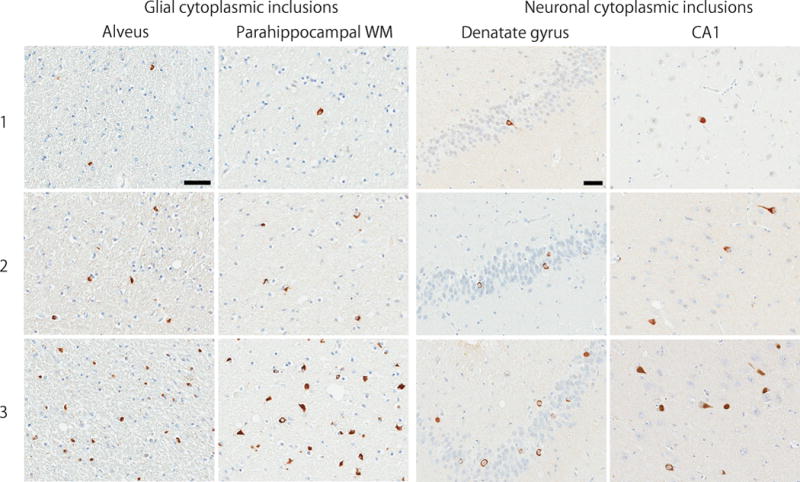

Neuropathological Assessment

All cases underwent a standardized neuropathological assessment for Alzheimer-type and Lewy-related pathologies. A Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage and Thal amyloid phase were assigned to each case with thioflavin S fluorescent microscopy.17, 18 Lewy-related pathology was assessed in the cortex, amygdala, basal forebrain and brainstem and classified as brainstem, transitional or diffuse Lewy body disease. Immunohistochemistry for α‐synuclein (NACP, 1:3000 rabbit polyclonal, Mayo Clinic antibody, FL) was performed on sections of basal forebrain, striatum, midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum to establish neuropathological diagnosis of MSA as described previously. MSA cases were pathologically divided into 3 types: predominant striatonigral involvement (SND), predominant olivopontocerebellar involvement (OPCA), and equally severe involvement of both systems (mixed). A semiquantitative assessment of GCI and NCI was performed in the following regions: the hippocampus and adjacent cortex, amygdala, cingulate gyrus, deep white matter adjacent to the cingulate gyrus, and middle frontal gyrus. The severity of α-synuclein pathology was graded on a four-point scale (0 = absent, 1 = sparse, 2 = moderate, 3 = frequent) as shown in Figure 1. All slides were reviewed simultaneously by two observers (DWD and SK). Neuropathological diagnoses of AD, HpScl, and cerebrovascular diseases were based on the established criteria.

Figure 1.

Semi-quantitative score on a four-point scale of α-synuclein pathology. Representative images of immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein on sections of hippocampus and adjacent cortex. The scores indicate 1 = sparse, 2 = moderate, and 3 = frequent. Bar = 50 μm.

Abbreviation: WM, white matter.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). A chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was performed for group comparisons of categorical data as appropriate. A rank sum test or t-test was used for analyses of continuous variables as appropriate. The point biserial correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between age at symptom onset, assessment, and death, and the presence or absence of objective impairment across the cognitive domains. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Summary of the cohort

This cohort included 102 patients (63 men and 39 women) with autopsy-confirmed MSA. Median age at symptom onset was 57 years and median age at death was 65 years. Thirteen patients (13%) had a family history of dementia and 17 (17%) had a family history of parkinsonism. Of 102 patients, 85 patients (83%) were given an antemortem diagnosis of MSA. The breakdown of the 17 misdiagnosed patients by antemortem diagnosis is as follows: progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) in 10 (59%), PD in 4 (24%), DLB in 1 (6%), primary progressive aphasia (PPA) in 1 (6%), and Meniere disease in 1 (6%). The clinical MSA phenotypes were MSA-P in 78 patients (76%) and MSA-C in 24 patients (24%). Alzheimer-type pathology was minimal, with median Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage of I and a Thal amyloid phase of 0. Four patients (4%) had a concurrent pathologic diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Lewy-related pathology was observed in 10 patients: 6 were brainstem type and 4 were transitional type. Seven patients (7%) had cerebrovascular pathology, and two patients (2%) had HpScl. Thirty-five cases (34%) were pathologically subclassified as MSA-SND, 14 cases (14%) were MSA-OPCA, 51 cases (50%) were MSA-mixed, and 2 cases (2%) could not be classified.

Examination of CI in MSA

Of 102 patients with autopsy-confirmed MSA, 33 (32%) patients had documented evidence of CI. The median duration between the age of symptom onset and age at onset of CI was 2 years, the median duration between the symptom onset and assessment by the clinician was 4 years, and the median duration between the age at assessment and age at death was 3 years. Only three patients (9%) initially presented with CI and motor symptoms simultaneously. One patient developed CI preceding motor symptoms by one year.

Table 1 summarizes the CI profile characteristics in the 33 MSA-CI patients. Domains of CI — processing speed, attention/executive function, memory, language, and visuospatial — were assigned based on reporting of the following objective CI indicators: comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations (N = 9, 27%), or cognitive screening tests (N = 13, 39%), and the reported presence of subjective CI indicators (i.e. clinical judgment, diagnostic impressions, and patient self-report; N = 11, 33%). Cognitive symptoms not reported in the record were designated as a blank (see Table 1). In order to analyze the CI profiles, CI descriptions of the domains noted above were required. Of the 13 patients who received cognitive screening measures, only six patients (46%) had reported total scores with no error scores. Therefore, these patients were analyzed using only the subjective CI indicators. Specific CI domains were not documented for one MSA-CI patient (Patient-22); thus, this patient was excluded from analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cognitive impairment in 33 patients with MSA

| No. | AO | AA | AD | Sex | Test Type |

Objective indicators | Subjective indicators | CP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| PS | Atn/EF | Mem | Lan | VS | PS | Atn/EF | Mem | Lan | VS | |||||||

| Pt-1 | 63 | 65 | 66 | M | NP | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-2 | 62 | 67 | 68 | F | NP | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | AD |

| Pt-3 | 71 | 73 | 74 | F | NP | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | |

| Pt-4 | 66 | 70 | 71 | M | NP | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-5 | 64 | 70 | 76 | M | NP | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-6 | 40 | 57 | 60 | M | NP | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| Pt-7 | 57 | 66 | 70 | F | NP | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| Pt-8 | 51 | 52 | 58 | F | NP | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | |

| Pt-9 | 57 | 60 | 65 | M | NP | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pt-10 | 45 | 54 | 56 | F | CS | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | |

| Pt-11 | 56 | 63 | 65 | M | CS | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | AD, CV |

| Pt-12 | 68 | 69 | 74 | F | CS | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-13 | 54 | 59 | 62 | M | CS | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | |

| Pt-14 | 67 | 68 | 70 | F | CS | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-15 | 51 | 58 | 60 | M | CS | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Pt-16 | 71 | 72 | 76 | F | CS | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | CV |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pt-17* | 60 | 64 | 67 | F | ** CS | + | − | + | − | − | ||||||

| Pt-18* | 44 | 52 | 53 | M | ** CS | + | − | − | − | − | ||||||

| Pt-19* | 59 | 67 | 70 | M | ** CS | + | − | − | − | − | ||||||

| Pt-20* | 56 | 60 | 65 | M | ** CS | − | − | + | − | − | ||||||

| Pt-21* | 86 | 87 | 89 | F | ** CS | − | − | + | − | + | CV | |||||

| Pt-22* | 79 | 81 | 82 | M | ** CS | − | − | − | − | − | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Pt-23* | 72 | 73 | 76 | M | + | − | + | − | − | AD | ||||||

| Pt-24* | 59 | 61 | 63 | M | + | − | + | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-25* | 80 | 80 | 84 | M | − | − | + | − | − | HS | ||||||

| Pt-26* | 66 | 66 | 70 | M | − | − | + | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-27* | 47 | 60 | 60 | F | − | − | + | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-28* | 58 | 68 | 72 | M | + | + | + | − | − | CV | ||||||

| Pt-29* | 48 | 57 | 60 | M | + | − | − | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-30* | 69 | 87 | 88 | F | − | + | + | + | + | AD, HS, CV | ||||||

| Pt-31* | 53 | 57 | 61 | M | − | − | + | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-32* | 34 | 57 | 59 | M | − | − | + | − | − | |||||||

| Pt-33* | 48 | 64 | 66 | F | + | − | − | + | − | |||||||

Abbreviations: AO, age at onset; AA, age at assessment; AD, age at death; PS, Processing speed; Atn, Attention; EF, Executive functions; Mem, Memory; Lan, Language; VS, Visuospatial processing; CP, concurrent pathology; AD, Alzheimer disease; HS, hippocampal sclerosis; CV, cerebrovascular pathology; Pt, patient; NP, Neuropsychological evaluation; CS, Cognitive screening; +, Impairment present; −, Impairment absent.

Cognitive symptoms not reported in the record are designated as blank.

= Cognitive impairments based upon subjective self-report and clinical impression.

= Cognitive screening total scores were available, but errors unavailable for review

The final groups for analyses consisted of objective CI indicators (OBJ; N = 16) and subjective CI indicators (SUB; N = 16). The OBJ and SUB groups did not statistically differ with regards to age at symptom onset (59 vs 59, P = 0.952), age at assessment (64 vs 66, P = 0.463), or age at death (67 vs 69, P = 0.525). The two groups did not statistically differ with regards to frequency of subjective CI indicators in processing speed (4 vs 8, P = 0.144), attention/executive function (2 vs 2, P = 1.000), memory (10 vs 12, P = 0.446), language (4 vs 2, P = 0.365), or visuospatial (0 vs 2, P = 0.144).

Overall, the OBJ group demonstrated deficits primarily in processing speed (N = 12, 75%) and attention/executive function (N = 11, 69%), followed by memory (N = 5, 31%), language (N = 2, 12%), and visuospatial (N = 3, 18%). For the nine patients who received neuropsychological evaluations, impairments were found predominantly in processing speed (N = 8, 89%) and attention/executive function (N = 7, 78%), with less frequent deficits in memory (N = 1, 11%), language (N = 2, 22%), and visuospatial (N = 1, 11%). In the seven patients who received cognitive screening tests (with error scores), impairments in processing speed, attention/executive function, and memory were observed in four patients (44%), respectively. Two patients (22%) exhibited visuospatial deficits. No objective language impairments were noted in patients with cognitive screening. There were no statistically significant correlations (point biserial correlation coefficient) between age of symptom onset (all P values > 0.135), age of assessment (all P values > 0.106), or age of death (all P values > 0.201), and the presence or absence of objective impairment in any of the five cognitive domains.

It is noteworthy that the most common subjective CI identified was in the memory domain. Of the 16 patients in the OBJ group, 10 (63%) had subjective memory impairment. Only one (6%) and four (25%) of the patients in the OBJ had objective memory impairment on neuropsychological assessment and cognitive screening, respectively. Another notable finding is that only three OBJ patients (19%) had deficits in visuospatial, a cognitive domain commonly impacted in α-synucleinopathies. In contrast, of the SUB group, memory impairment (N = 12, 75%) was again the most frequent domain of subjective impairment, followed by processing speed (N = 8, 50%). Only one patient (6%) exhibited attention/executive function subjective impairment. Overall, objective cognitive indicators revealed impairments primarily in processing speed and attention/executive function. Although memory impairments were the most frequently affected subjective cognitive domain in MSA, objective indicators were more likely to identify processing speed and attention/executive function deficits than memory deficits.

Comparison between MSA-CI and MSA-NC

Table 2 compares the demographic and clinical features of the between MSA-CI and MSA-NC. MSA-CI had an older age at onset and death than those of MSA-NC (59 vs 57, P = 0.045; 66 vs 63, P = 0.029, respectively). Median disease duration was 7 years in both groups. The proportion of women and the frequency of family history of dementia and parkinsonism were not different between the two groups. The frequency of having clinical diagnosis of MSA was significantly lower in MSA-CI compared to MSA-NC (71% vs 90%, P = 0.023). Of the 33 patients with MSA-CI, 10 patients were not diagnosed with MSA: PSP in 6, PD in 2, DLB in 1, and PPA in 1 patient. The proportion of clinical MSA phenotypes was not different between MSA-CI and MSA-NC. Patients with MSA-CI more frequently had depression compared to MSA-NC, although it did not reach statistical significance (52% vs 30%, P<0.066).

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical features between MSA-CI and MSA-NC

| Features | MSA-CI (N = 33) | MSA-NC (N = 69) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, no. (%) | 13 (39) | 26 (38) | 0.986 |

| Age at onset, years | 59 (52, 68) | 57 (50, 61) | 0.045 |

| Age at death, years | 66 (60, 74) | 63 (58, 70) | 0.029 |

| Disease duration, years | 7 (4, 9) | 7 (5, 10) | 0.833 |

| Family history of dementia (%) | 6 (18) | 7 (10) | 0.411 |

| Family history of Parkinsonism (%) | 6 (18) | 11 (16) | 1.000 |

| Having clinical diagnosis of MSA (%) | 23 (70) | 62 (90) | 0.023 |

| Clinical phenotype (%) | |||

| Parkinson type | 23 (70) | 55 (80) | 0.387 |

| Cerebellar type | 10 (30) | 14 (20) | |

| Clinical symptom (%) | |||

| Depression | 17 (52) | 21 (30) | 0.066 |

Data are displayed as median (25th, 75th %-tile). Abbreviations: MSA-CI, multiple system atrophy with cognitive impairment; MSA-NC, multiple system atrophy without cognitive impairment;

Pathologic assessment

Table 3 compares pathologic features between MSA-CI and MSA-NC. Median brain weight of MSA-CI was less than that of MSA-NC (1200 grams vs 1300 grams, P = 0.016). The frequency of Lewy-related pathology, median Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage, and median Thal amyloid phase were not different between the two groups. Four patients with pathologically-diagnosed AD, two patients with HpScl and five patients with significant cerebrovascular pathology developed CI. Taken together, eight of 33 patients with MSA-CI (Patient-11 and Patient-30 had multiple pathologies) had at least one concurrent pathology of dementia (see Table 1), although they were not given antemortem diagnoses of these diseases.

Table 3.

Comparison of pathologic features between MSA-CI and MSA-NC

| Features | MSA-CI (N = 33) | MSA-NC (N = 69) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain weight, g | 1200 (1100, 1200) | 1300 (1100, 1400) | 0.016 |

| Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage | I (0, II) | II (I, II) | 0.971 |

| Thal amyloid phase | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.158 |

| Concurrent pathology (%) | |||

| Alzheimer disease | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.016 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.272 |

| Cerebrovascular pathology | 5 (14) | 2 (3) | 0.061 |

| Lewy-related pathology | 2 (5) | 8 (12) | 0.654 |

| Brainstem type | 1 (3) | 5 (8) | |

| Transitional type | 1 (3) | 3 (5) | |

| Pathologic subtype (%) | |||

| SND | 14 (42) | 21 (30) | 0.348 |

| OPCA | 5 (15) | 9 (13) | |

| Mixed | 13 (39) | 38 (55) | |

| Unclassified | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| NCI Score | |||

| Dentate gyrus | 1 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.001 |

| Hippocampal CA1 | 1 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.130 |

| Amygdala | 1 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.217 |

| Cingulate gyrus | 1 (1, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.642 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 1) | 0.237 |

| GCI Score | |||

| Hippocampal alveus | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.286 |

| Parahippocampal white matter | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.591 |

| Amygdala | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.106 |

| Cingulate gyrus | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.718 |

| Deep white matter | 2 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.603 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 2 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.230 |

Data are displayed as median (25th, 75th %-tile). Abbreviations: NCI, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion; GCI, glial cytoplasmic inclusion; SND, MSA with predominant striatonigral involvement; OPCA, MSA with predominant olivopontocerebellar involvement.

To elucidate any potential association between α-synuclein pathology and CI, we compared the burden of NCI and GCI between MSA-CI and MSA-NC. The burden of NCI in the dentate gyrus was greater in MSA-CI than in MSA-NC (1 vs 0, P = 0.001), but it was not significantly different in other regions. The burden of GCI was not different in any regions of interest between the two groups. Since a possible association between neocortical Lewy body-like NCIs and CI has been reported, we also assessed the Lewy body-like NCIs in the middle frontal gyrus. Two patients had this pathology (Supplementary Figure 1), but they were cognitively intact.

Influence of concurrent pathology

As mentioned above, eight patients with MSA-CI had concurrent pathology of dementia (i.e. AD, HpScl, and cerebrovascular pathology); therefore, these pathologies might have contributed to their CI rather than α-synuclein pathology. To exclude the influence of these pathologies of dementia, we also analyzed patients with MSA without these pathologies. As shown in table 4, age at onset and death, disease duration, and median brain weight were not significantly different between the two groups. Even after excluding these patients, the burden of NCI in dentate gyrus was still greater in MSA-CI compared to MSA-NC (1 vs 0, P <0.001). We conclude that greater burden of NCI in dentate gyrus is a correlate of CI in MSA patients.

Table 4.

Pathologic features in MSA patients without concurrent pathologies of dementia

| Features | MSA-CI (N = 25) | MSA-NC (N = 67) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset, years | 57 (52, 66) | 57 (50, 60) | 0.394 |

| Age at death, years | 65 (60, 70) | 63 (57, 69) | 0.375 |

| Disease duration, years | 7 (4, 9) | 7 (5, 10) | 0.892 |

| Brain weight, g | 1200 (1100, 1300) | 1300 (1100, 1400) | 0.125 |

| Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage | I (0, II) | I (I, II) | 0.483 |

| Thal amyloid phase | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.244 |

| NCI Score | |||

| Dentate gyrus | 1 (1, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | <0.001 |

| Hippocampal CA1 | 1 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.073 |

| Amygdala | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | 0.472 |

| Cingulate gyrus | 1 (1, 1) | 0 (1, 1) | 0.896 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 1) | 0.194 |

| GCI Score | |||

| Hippocampal alveus | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.134 |

| Parahippocampal white matter | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 0.237 |

| Amygdala | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.125 |

| Cingulate gyrus | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.964 |

| Deep white matter | 2 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.278 |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.759 |

Data are displayed as median (25th, 75th %-tile).

Discussion

In this autopsy-confirmed MSA series, 32% of the patients with MSA had CI documented in the medical record, which is similar to that of other autopsy series.2, 5–7 The profile of CI identified in this cohort affected a wide range of domains. The objective deficits found were primarily in processing speed and attention/executive functions. Subjective memory impairments were documented in 66% of the cohort; however, memory deficits were objectively characterized in only 15%. In contrast, the patients with scores on cognitive screening tests performed more poorly on memory recall items compared to evidence of memory deficits from neuropsychological assessments. This finding might be explained by the fact that memory problems are a commonly misclassified neurological symptom that is often caused by deficits in cognitive domains unrelated to recall ability (e.g., poor encoding due to inattention).

The severity of CI identified in this cohort was relatively mild compared to impairments often seen in other α-synucleinopathies such as DLB. It is worth noting that 59% (10/17) of patients who were given an antemortem diagnosis of a condition other than MSA had CI. This suggests that patients presenting with parkinsonism and CI tend to be misdiagnosed as other neurodegenerative diseases, namely PSP, PD, and DLB, even when they had MSA pathology. Our results suggest that although dementia is an exclusion criterion of MSA, MSA should not be excluded from the differential diagnoses in patients with mild cognitive deficits.

We found a trend for increased depression in patients with MSA-CI. Although rating scales or other objective data were unavailable for review, 37% of patients with MSA (38/102) had depression, which is almost within the range of other parkinsonian disorders.27, 28 Patients with depression sometimes mimic patients with dementia (depressive pseudo-dementia), which is characterized with frontal-subcortical dementia.29, 30 Thus, MSA-CI in the present study might include some patients with depressive pseudo-dementia. Given the retrospective nature of this study, however, it was challenging to distinguish between depressive pseudo-dementia and genuine CI.

There are conflicting reports concerning the frequency and severity of CI between MSA-P and MSA-C.31, 32 These studies were based on the patients with clinically-diagnosed MSA. Kawai and colleagues reported that patients with MSA-P showed more severe and widespread cognitive dysfunction than patients with MSA-C. In contrast, MSA-C had more pronounced executive and verbal memory decline compared to MSA-P. Results of our study indicate that both MSA clinical phenotypes (i.e. MSA-P and MSA-C) and pathologic subtypes (i.e. SND, OPCA, and mixed) were not related with the frequency of CI; however, to assess the association with severity or ranges of CI, it is necessary to conduct a prospective study.

The neuropathologic analysis revealed that burden of NCI in limbic regions was greater in MSA-CI than in MSA-NC. After excluding patients who have concurrent pathologies of dementia, the burden of NCI in dentate gyrus was still greater in MSA-CI. Taken together, severe NCI pathology in dentate gyrus may correlate with CI in MSA that cannot be explained by AD, HpScl or cerebrovascular pathology. These results are consistent with a recent study, which suggests that frequent globular NCIs in the medial temporal regions is one of the pathologic features of dementia in MSA. Aoki et al. proposed a novel variant of MSA, atypical MSA, which is characterized by abundant Pick body-like NCIs in the limbic regions and severe atrophy of frontal lobe. Patients with atypical MSA show a phenotype of frontotemporal dementia or corticobasal syndrome.10, 11 The MSA-CI brains evaluated in this study did not have significant cortical atrophy. We assume that there is a spectrum of NCI pathology in the limbic regions and that atypical MSA is an extreme variant of the MSA-CI.

Nevertheless, the present study could not identify the regions responsible for specific cognitive deficits. Deficits in processing speed and executive functions are considered to be caused by deep white matter damages including periventricular, cingulate, and frontal white matter. We selected deep white matter under the cingulate gyrus and middle frontal gyrus to assess this pathology, but there was no difference in the burden of GCI. On the other hand, Cykowski et al. reported a significant association between Lewy body-like NCIs in neocortex and CI. We identified Lewy body-like NCIs in only two patients, and they were cognitively intact. The frequency of NCIs was also different between the two studies. We found this pathology in 68% of patients, while all 35 patients had NCIs in the superior frontal gyrus in their study. This discrepancy might be caused by different regions of interest (middle frontal vs superior frontal), technical issues (i.e. α-synuclein immunohistochemistry), and morphologic criteria for NCIs. It is challenging to distinguish between genuine Lewy bodies from Lewy body-like NCIs in MSA,37, 38 but we considered this pathology as NCI, not Lewy body, in these two patients because there was no Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in regions most frequently affected in LBD such as dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve and locus coeruleus. Besides NCIs, overall progression of the underlying pathology including α-synuclein, neuronal loss, and synaptic loss, could be associated with CI. Further studies are necessary to elucidate pathological mechanism of CI in MSA.

A major limitation of our study is its retrospective nature and the fact that not all patients with MSA received cognitive screening tests or neuropsychological evaluations. Only 27% of patients with MSA-CI underwent a formal neuropsychological assessment, and 50% receiving an objective measure of cognitive functioning overall. Diagnosis of cognitively intact patients is another challenge. Sixty-nine patients were considered as cognitively intact based on a review of records involving physician’s examinations. It should be noted that, due to the retrospective record review design of this study, only CI reported in patient records were available for analysis. This inclusion of only explicitly positive or negative findings might cause an underestimation of CI in MSA. Therefore, prospective studies collecting detailed symptom profiles and severity indicators are required to obtain a more accurate understanding of CI in MSA. Another limitation is a method to assess white matter pathology. We only sampled two areas (i.e. deep white matter under the cingulate gyrus and middle frontal gyrus) to assess a correlation between white matter pathology and CI, but it should be evaluated in more regions, including periventricular white matter. In addition, GCI scores might be underestimated due to the ceiling effect; most cases have score 2 or 3 out of the 4-point scale. A notable strength of our study is that the diagnoses of MSA was confirmed at an autopsy, while most of the literature on CI in MSA is based clinical MSA. Because the clinical diagnostic accuracy of MSA is only 62%, it is important to study MSA based on autopsy-confirmed cohorts. Another advantage of this study is the size of the sample with autopsy-confirmed MSA reviewed for CI, which is greater than previously published studies.5, 9

In conclusion, the results of our study showed that a subset of patients with MSA have mild cognitive deficits primarily in processing speed and attention/executive functions, which suggests a predominant frontal-subcortical pattern of cognitive dysfunction. When assessed objectively, these deficits were more evident on neuropsychological assessment compared to cognitive screens, which tend to be limited in the measurement of processing speed and executive functions. Our findings suggest that clinicians should be aware that subjective CI in MSA primarily presents subjectively as memory complaints, which are not substantiated on neuropsychological tests. Furthermore, we recommend that clinicians consider neuropsychological assessment beyond cognitive screening instruments if patients with MSA present with cognitive complaints. Although we did not identify a correlation between the domains of CI and respective functional neuroanatomical regions, a greater burden of NCI in the dentate gyrus was associated with CI in MSA.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Various morphology of neuronal inclusions in the middle frontal gyrus. Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein demonstrates neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion (A), combined intranuclear/cytoplasmic inclusion (B), tangle-like inclusion (C) and Lewy body-like inclusion (D). Bar = 15 μm. All images are the same magnification.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and their families who donated brains to help further the scientific understanding of neurodegeneration. The authors would also like to acknowledge Linda Rousseau (Mayo Clinic) and Virginia Phillips (Mayo Clinic) for histologic support, and Monica Castanedes-Casey (Mayo Clinic) for immunohistochemistry support. Supported by NIH grant P50 NS072187 and a Jaye F. and Betty F. Dyer Foundation Fellowship in progressive supranuclear palsy research.

Financial Disclosures of all authors

Dr. Koga reports no disclosures.

Dr. Parks reports no disclosures.

Dr. Uitti receives research support by the NIH (P50-NS072187, and from Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc./St. Jude Medical, Dr. Uitti is an Associate Editor of Neurology and an editorial board member of Parkinsonism & Related Disorders.

Dr. van Gerpen receives research funds from the Mayo Clinic CR program and NIH (P50-NS072187). This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Dr. Cheshire is consultant for American Academy of Neurology, Neuro SAE examination writer, 2013; and receives support from NIH, Autonomic Rare Diseases Clinical Research Consortium. He is editorial board member of Autonomic Neuroscience.

Dr. Wszolek is partially supported by the NIH/NINDS P50 NS072187, NIH/NIA (primary) and NIH/NINDS (secondary) 1U01AG045390-01A1, Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic Neuroscience Focused Research Team (Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation, and the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Fund for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at Mayo Clinic in Florida), the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch, and The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust. Dr. Wszolek serves as Co-Editor-in-Chief of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, Associate Editor of the European Journal of Neurology, and on the editorial boards of Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska, the Medical Journal of the Rzeszow University, and Clinical and Experimental Medical Letters; holds and has contractual rights for receipt of future royalty payments from patents re: A novel polynucleotide involved in heritable Parkinson’s disease; receives royalties from editing Parkinsonism and Related Disorders (Elsevier, 2015, 2016) and the European Journal of Neurology (Wiley- Blackwell, 2015, 2016).

Dr. Dickson receives support from the NIH (P50-NS072187). Dr. Dickson is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology, and he is editor in chief of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease, and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Shunsuke Koga: Execution of the project; analysis and interpretation of data; execution of the statistical analysis; Writing of the first draft

Adam Parks: Analysis and interpretation of data; Execution of the statistical analysis; review and edit the draft

Ryan J. Uitti: Review and critique; contribution of patients

Jay A. Van Gerpen: Review and critique; contribution of patients

William P. Cheshire: Review and critique; contribution of patients

Zbigniew K. Wszolek: Review and critique; contribution of patients

Dennis W Dickson: Conception and organization of the project; interpretation of data; review and critique

References

- 1.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670–676. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenning GK, Tison F, Ben Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Quinn NP. Multiple system atrophy: a review of 203 pathologically proven cases. Mov Disord. 1997;12(2):133–147. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papp MI, Kahn JE, Lantos PL. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in the CNS of patients with multiple system atrophy (striatonigral degeneration, olivopontocerebellar atrophy and Shy-Drager syndrome) J Neurol Sci. 1989;94(1–3):79–100. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stankovic I, Krismer F, Jesic A, et al. Cognitive impairment in multiple system atrophy: a position statement by the Neuropsychology Task Force of the MDS Multiple System Atrophy (MODIMSA) study group. Mov Disord. 2014;29(7):857–867. doi: 10.1002/mds.25880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cykowski MD, Coon EA, Powell SZ, et al. Expanding the spectrum of neuronal pathology in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 8):2293–2309. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koga S, Aoki N, Uitti RJ, et al. When DLB, PD, and PSP masquerade as MSA: an autopsy study of 134 patients. Neurology. 2015;85(5):404–412. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homma T, Mochizuki Y, Komori T, Isozaki E. Frequent globular neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the medial temporal region as a possible characteristic feature in multiple system atrophy with dementia. Neuropathology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/neup.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siri C, Duerr S, Canesi M, et al. A cross-sectional multicenter study of cognitive and behavioural features in multiple system atrophy patients of the parkinsonian and cerebellar type. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2013;120(4):613–618. doi: 10.1007/s00702-013-0997-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asi YT, Ling H, Ahmed Z, Lees AJ, Revesz T, Holton JL. Neuropathological features of multiple system atrophy with cognitive impairment. Mov Disord. 2014;29(7):884–888. doi: 10.1002/mds.25887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki N, Boyer PJ, Lund C, et al. Atypical multiple system atrophy is a new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated with alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(1):93–105. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1442-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohan Z, Rahimi J, Weis S, et al. Screening for alpha-synuclein immunoreactive neuronal inclusions in the hippocampus allows identification of atypical MSA (FTLD-synuclein) Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(2):299–301. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koga S, Dickson DW, Bieniek KF. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Pathology in Multiple System Atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokmen E, Naessens JM, Offord KP. A short test of mental status: description and preliminary results. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62(4):281–288. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests : administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58(12):1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosaka K, Yoshimura M, Ikeda K, Budka H. Diffuse type of Lewy body disease: progressive dementia with abundant cortical Lewy bodies and senile changes of varying degree–a new disease? Clin Neuropathol. 1984;3(5):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickson DW, Liu W, Hardy J, et al. Widespread alterations of alpha-synuclein in multiple system atrophy. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(4):1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trojanowski JQ, Revesz T. Proposed neuropathological criteria for the post mortem diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33(6):615–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozawa T, Paviour D, Quinn NP, et al. The spectrum of pathological involvement of the striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems in multiple system atrophy: clinicopathological correlations. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 12):2657–2671. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56(10):1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pao WC, Dickson DW, Crook JE, Finch NA, Rademakers R, Graff-Radford NR. Hippocampal sclerosis in the elderly: genetic and pathologic findings, some mimicking Alzheimer disease clinically. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(4):364–368. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31820f8f50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid LM, Maclullich AM. Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5–6):471–485. doi: 10.1159/000096295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrag A, Sheikh S, Quinn NP, et al. A comparison of depression, anxiety, and health status in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2010;25(8):1077–1081. doi: 10.1002/mds.22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benrud-Larson LM, Sandroni P, Schrag A, Low PA. Depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in patients with multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2005;20(8):951–957. doi: 10.1002/mds.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells CE. Pseudodementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(7):895–900. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.7.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonelli RM, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical dementias. Neurologist. 2008;14(2):100–107. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e31815b0de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai Y, Suenaga M, Takeda A, et al. Cognitive impairments in multiple system atrophy: MSA-C vs MSA-P. Neurology. 2008;70(16 Pt 2):1390–1396. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310413.04462.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang CC, Chang YY, Chang WN, et al. Cognitive deficits in multiple system atrophy correlate with frontal atrophy and disease duration. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(10):1144–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang DS, Bennett DA, Mufson EJ, Mattila P, Cochran E, Dickson DW. Contribution of changes in ubiquitin and myelin basic protein to age-related cognitive decline. Neurosci Res. 2004;48(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Brien JT, Wiseman R, Burton EJ, et al. Cognitive associations of subcortical white matter lesions in older people. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:436–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grambaite R, Selnes P, Reinvang I, et al. Executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment is associated with changes in frontal and cingulate white matter tracts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27(2):453–462. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez JA, Emory E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2006;16(1):17–42. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida M. Multiple system atrophy: alpha-synuclein and neuronal degeneration. Neuropathology. 2007;27(5):484–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickson DW, Lin W, Liu WK, Yen SH. Multiple system atrophy: a sporadic synucleinopathy. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(4):721–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Various morphology of neuronal inclusions in the middle frontal gyrus. Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein demonstrates neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion (A), combined intranuclear/cytoplasmic inclusion (B), tangle-like inclusion (C) and Lewy body-like inclusion (D). Bar = 15 μm. All images are the same magnification.