Introduction

Chest pain is a frequent childhood complaint that leads to evaluation by healthcare providers.1–4 Chest pain in the adult population is commonly associated with cardiac disorders and sudden death. Children with chest pain are frequently brought to the emergency department (ED) by anxious parents who associated chest pain with cardiac disease.5 Definitively ruling out cardiac disease in children can be more challenging because most young children are not able to accurately describe or localize their pain. This may prompt further testing, leading to high resource utilization for chest pain evaluation.3,6, 7 Despite more testing and consultation, a cardiac etiology is found in only a small minority of cases, reported as 1 to 10% in prior studies.2 Given the low incidence of disease, wide practice variation, and high costs associated with chest pain, there has been significant recent interest in creating practice algorithms to reduce waste for chest pain presentation at the cardiology clinic level.8, 9, 10 We report herein our efforts to streamline patient care and minimize unnecessary testing in the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) ED.

Like most hospitals in the United States, CHOP now devotes substantial resources to increasing the value of care delivered, defined as quality over cost.11 One aspect of the efforts to improve value is CHOP’s emphasis on the development of clinical pathways. Members from the CHOP Divisions of Cardiology and Emergency Medicine jointly created a pathway for the assessment of children with chest pain with no prior cardiac disease, with specific goals of reducing unnecessary testing and cardiology consultation in the ED, without missing cases of severe cardiac disease.

Methods

The CHOP Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the study as a quality improvement activity and that the project did not meet criteria for human subjects’ research.

Study Design, Setting and Population

Using a quasi-experimental design, clinical data were reviewed from patients who presented March 1, 2013 through April 22, 2015 with chest pain.

The pathway was designed to focus on children aged 3 to 18 years old presenting with chest pain to the ED. The CHOP ED has an annual volume of approximately 90,000 patient visits a year. From 2012 through 2014, approximately 1700–2000 visits were due to pediatric chest pain, annually.

Design and Implementation of the clinical pathway

The creation and implementation of this pathway was a collaborative effort between Cardiology and Emergency Medicine, with faculty, nurse practitioner and fellow input (see Figure 1). The stated goal of the pathway was to reduce unnecessary diagnostic testing, cardiology consultation, and reduce ED length of stay (LOS).

Figure 1.

Timeline of Clinical pathway creation

After a literature search on the epidemiology, diagnostic workup and management of pediatric chest pain was performed, a preliminary pathway was drafted in June 2013 by the cardiology fellows and then was modified with the help of the cardiology consult team and ED. The pathway was designed to aid a front line provider in the evaluation of a pediatric patient presenting with chest pain who had no prior cardiac diagnosis. Guidelines for the interpretation of a pediatric electrocardiogram were drafted and approved by the Section of Pediatric Electrophysiology. In addition to making recommendations for specific diagnostic testing (basic metabolic panel, troponins, chest x-ray) when prompted by historical and physical exam findings, recommendations were made for follow-up with the primary care provider or pediatric cardiologist where indicated. An electronic history and physical examination template was created for the evaluation of children with chest pain prompting physicians to check for specific signs and symptoms and document cardiology consultation. A mechanism for follow-up was instituted in computerized order entry system if the emergency department provider felt cardiology follow up was warranted. Discharge instructions for patients discharged from the ED were also drafted, including instructions for families should symptoms persist or require further workup and evaluation. Instructions on exercise restriction were also provided at the discretion of the emergency department until evaluated by a pediatric cardiologist. The most recent iteration of the pathway can be found in Supplementary Material-Pathway.

An electronic orderset was created for the evaluation of patients to streamline orders, maximize use of the pathway, and augment later tracking of orders for QI research purposes.

The pathway was implemented on March 1, 2014, with several weeks of intensive education efforts aimed at ED and cardiology faculty, as well as ED and pediatric housestaff and nurse practitioners. The pathway was presented at a division meeting for the department approximately 2 months prior to implementation. Visiting residents and faculty received an orientation to the CHOP emergency department including educational sessions on the electronic medical record, order-sets and clinical pathways.

Patient identification for pathway eligibility

Patients who met criteria for the pathway and presented to the CHOP ED between March 1, 2013 and April 22, 2015 were extracted from the CHOP Data Warehouse. In order to identify patients who were seen for chest pain, two data sources were used: the chief complaint that was collected upon entry to the ED and the visit reason as recorded during the encounter. If either of the mentioned fields had the words “chest” and “pain” in them, in any order, they were flagged for inclusion.

Patients were flagged for exclusion if they had a known alternative etiology for chest pain, such as sickle cell disease, gastroesophageal reflux (GER) or asthma, prior to the ED encounter. Patients who also had a known cardiac diagnosis or diagnosis that is known to have a high likelihood of presenting with chest pain (i.e. Marfan’s Syndrome) were also excluded using this methodology using a list of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes (see Supplementary material-exclusion diagnoses). Data used to determine exclusion was taken from active diagnoses documented in the electronic health record (EHR) during a prior visit or from medical history noted during the ED encounter.

Search Validation & Chart Abstraction

Two cardiology fellows independently reviewed 20 charts pre-pathway implementation and 20 charts post-pathway implementation. This was to ensure the search strategy was valid and to assess inter-rater reliability for specific information that was not readily apparent in the provider note during a patient’s encounter in the ED. The fellows assessed for the presence of the following variables:

Echocardiogram Performed in Emergency Department

Extent of Cardiology Consultation (none, discussed by phone with Cardiology, bedside Fellow consultation without Faculty staffing, complete Faculty level consultation)

Patient bounce back (<30 days from initial ED visit)

Patient had a formal cardiology follow up in clinic (<4 weeks from initial ED visit)

Patient had a formal follow up visit with primary care provider if within CHOP system

Patient had a final diagnosis

After independent review, there was complete agreement for all the data stated above (κ=1.0). The same two fellows then proceeded with full data collection, abstracting the above data from all patients included in the study. Study data were uploaded and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture),12 a secure web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, hosted internally at CHOP.

The details of each cardiology consultation and patient follow up were only available through October 14, 2014. Data on diagnostic testing, diagnoses, disposition and ED length of stay were obtained through April 22, 2015.

Statistical Analysis

χ2 tests were used to compare the proportion of patients undergoing diagnostic testing as an outcome before and after implementation of the clinical pathway. All tests were two-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted by using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.). Statistical run charts were created to monitor resource utilization over time. For each diagnostic test or resource utilized by month during the study period, the percent of patients undergoing a specific test was calculated.

Results

A total of 3904 patient visits for chest pain occurred between March 1, 2013 and April 22, 2015 using the search strategy described. Using our inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1690 patients met inclusion for the clinical pathway and after review of all those ED encounters and documentation, 1687 were found to be appropriately captured by the search algorithm. The majority of patients were discharged from the emergency department with 111 patients being admitted to the hospital over the study period. Demographics and admissions rates of the patient cohort are described in Table 1. Pre- and post-pathway implementation analysis revealed there was no significant difference in patient gender or age, with just over half the patients being female and between the ages of 12 and 18 years.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of study patients

| Demographic Characteristic |

Pre-Pathway, n=675, (%) | Post-Pathway, n=1012, (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, girls | 381 (56.4) | 584 (57.7) |

| Mean age, y (median, IQR) | 12.1 (12.4, 9.1–15.5) | 12.1 (12.6, 3.0–18.9) |

| Age Ranges | ||

| <6 years old | 53 (7.9) | 89 (8.8) |

| 6 to ≤12 years old | 271 (40.1) | 386(38.1) |

| 12–18 years old | 351 (52) | 537 (53.1) |

| Disposition | ||

| Home | 630 (93.3) | 946 (93.5) |

| Inpatient Unit | 45 (6.7) | 66 (6.5) |

| ICU | 0 | 0 |

No statistical difference for above characteristics, p>0.2 for all.

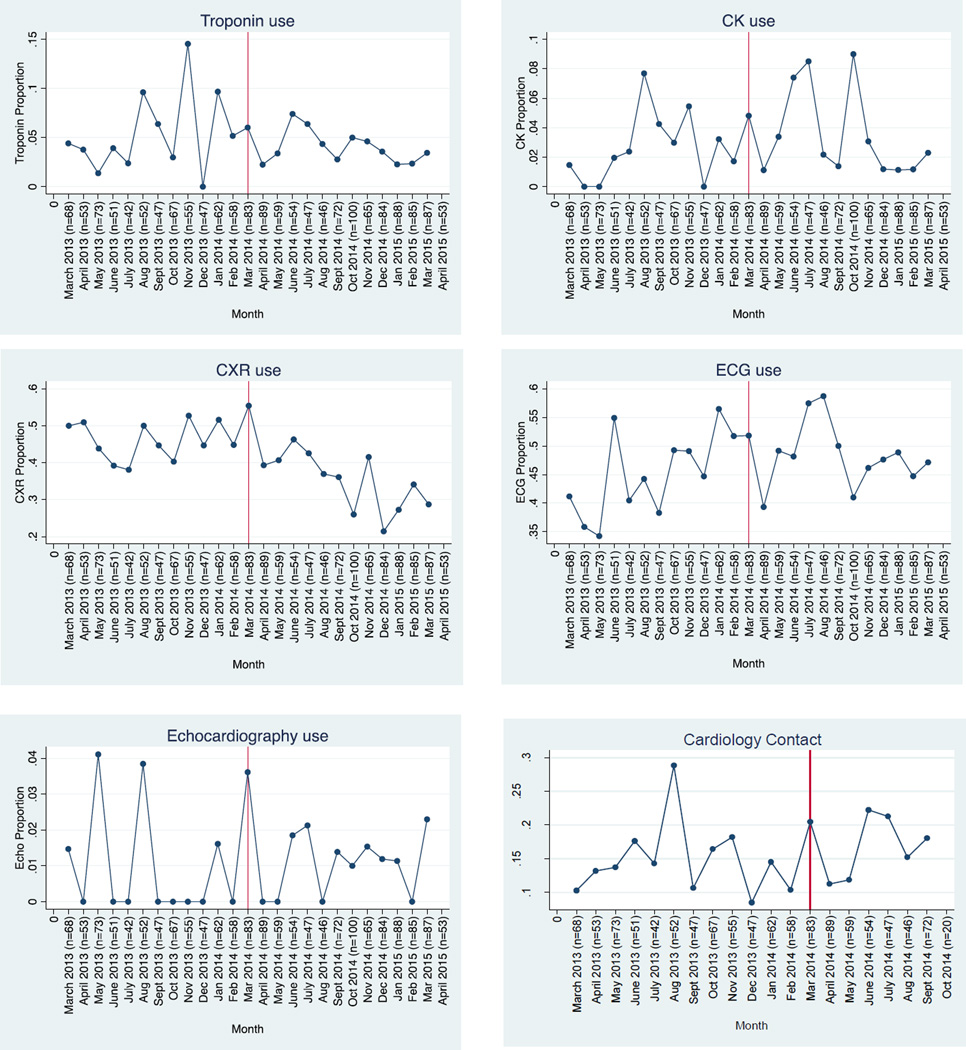

The rates and proportions of diagnostic tests pre- and post-pathway implementation were visualized using run charts and compared statistically by χ2 testing. There were no significant changes in the proportions of diagnostic tests ordered with the exception of chest x-rays (Table 2 and Figure 2). Chest x-ray use declined from 46.1% of pathway-eligible patients to 35.6% (P < 0.01). There was no significant change in requests for cardiology consultation in the emergency department (cardiology involved in 14.7% of cases pre-pathway, and 17.0% post-pathway (P=0.28, Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Testing with Pathway Implementation

| Diagnostic Test | Pre Pathway | Post Pathway | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Troponin | 5.3% | 3.9% | 0.15 |

| CK | 2.5% | 3.4% | 0.32 |

| BNP | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.24 |

| BMP | 5% | 5.1% | 0.93 |

| CXR | 46.1% | 35.6% | <0.01 |

| ECG | 45% | 47.7% | 0.28 |

| CBC | 10.8% | 9.6% | 0.41 |

| UDS | 3.1% | 2.2% | 0.23 |

| CRP | 5% | 4.5% | 0.57 |

| ESR | 0% | 0.1% | 0.41 |

| D-dimer | 1.8% | 1.4% | 0.52 |

| Echo | 1% | 1.2% | 0.78 |

Figure 2.

Run charts displaying the proportions of diagnostic tests and cardiology contact. The vertical red line denotes the pathway implementation date. The horizontal axis is the timeline of the study period and in parentheses is the total number of chest pain patients that presented to the ED who fit the study criteria.

Table 3.

Cardiology Consultation (March 2, 2013-October 14, 2014)

| Cardiology Consultation in ED |

Pre Pathway (n=675) |

Post Pathway (n=470) |

|---|---|---|

| Consultation | 99 | 80 |

| Case discussed with cardiology by phone | 70 | 62 |

| Patient seen by Fellow | 15 | 8 |

| Formal consultation (staffed by attending cardiologist) | 14 | 10 |

P value=0.48

The majority of patients who came to the emergency department were not found to have a clear etiology for their chest pain as evidenced by the final ICD-9 diagnoses upon discharge. The common diagnosis codes are listed in Table 4. A small minority of patients (11 patients) over the entire time period was found to have a cardiac etiology for their chest pain. Of these patients, four had myocarditis/myopericarditis, two had pericarditis, two had supraventricular tachycardia and three presented with premature ventricular contractions (one was after blunt chest trauma from a motor vehicle accident). Five of the eleven patients with cardiac disease presented post-pathway implementation and were all identified by the pathway.

Table 4.

Discharge Diagnoses from the ED for study period

| Main Diagnosis (ICD-9) | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Unspecified Chest Pain (786.50) | 328 |

| Other Chest Pain (786.59) | 295 |

| Tietze’s Disease (733.6) | 190 |

| Unspecified Viral Infection (079.99) | 40 |

| Esophageal reflux (530.81) | 46 |

| Asthma Unspecified with acute exacerbation (493.92) | 26 |

| Acute Upper respiratory infection of unspecified site (465.9) | 33 |

With regard to the level of cardiology consultation (phone call, bedside fellow or attending consultation) in the emergency department for this patient population, there was no significant change for the first six months after implementation of the pathway, by χ2 analysis (p=0.48). For the entire study period, the length of stay in the emergency department reduced from 3.3 pre-pathway to 3.08 hours post-pathway and reached statistic significance by Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p=0.03).

Patient follow-up increased after pathway implementation from 15% to 30% (p < 0.001). Follow up was considered to have taken place if the patient saw their primary care provider or a pediatric cardiologist within the CHOP health care system. In the follow-up of 102 patients pre-pathway and 137 patients post-pathway, with follow-up range of 4 weeks to 2 years, no significant cardiac etiologies of chest pain were missed.

Discussion

Our study suggests that resource utilization in a pediatric emergency department can be influenced by the creation of a clinical pathway for chest pain. Following pathway implementation, there was a statistically significant reduction in chest x-rays ordered. Other tests were noted to decrease but were not found to be statistically significant. There was an increase in ECG ordering, but this is not surprising as it is the first recommended diagnostic test recommended in the pathway when trying to screen for cardiac pathology. There was also less dramatic variation in the proportion of troponins ordered in the emergency department over time since pathway implementation. Most importantly, no cases of cardiac disease were missed with implementation of the pathway and there was an increase in follow-up after the ED visit for the patients followed in the CHOP system. Finally, there was a reduction in ED length of stay that was statistically significant, however this may not be clinically relevant for the individual patient for decrease in length of stay from 3.3 to 3.08 hours in the ED.

One possible explanation for the minimal change in resource utilization was that the providers in the emergency department were low utilizers of resources from the onset. Looking at the common discharge diagnoses of patients who presented to the emergency department (Table 4), the majority of diagnoses were idiopathic (“Unspecified Chest Pain”), musculoskeletal (Tietze’s Disease), gastroesophageal reflux or asthma. Those who were diagnosed with asthma were new diagnoses presenting with a first time exacerbation. This reflects what has been found in previous studies and reviews of pediatric chest pain.2, 3, 13, 14 Low resource utilization may reflect a sophisticated level of understanding of the likely diagnosis for chest pain amongst our ED providers. There were a low proportion of echocardiograms ordered and no change with pathway implementation. In our institution, only those within the division of cardiology can order an echocardiogram. The low incidence of echocardiograms is a reflection of the low incidence of cardiac disease in this population that was targeted by the clinical pathway.

However, the possibility of a failure of pathway implementation also exists.15 There were minimal barriers to feasibility and there were low implementation costs. Educational efforts were sound, and the pathway was well received. Analyzing use of the EHR orderset, as well as post-hoc chart review, could theoretically ascertain pathway use. The EHR orderset was used infrequently, however, due to the pathway’s relative simplicity with only 5% of patients receiving orders in this manner. A post-hoc chart review was performed and twenty patients were randomly chosen pre and post pathway and the adherence to the clinical pathway was evaluated based on the documentation of the clinical note in the ED at the time of chest pain evaluation. The fidelity to the clinical pathway had increased from 65% to 95%, implying successful implementation and acceptance of the pathway by the ED. Post-implementation chart review was notable for marked increase in documentation of more information relative to the clinical pathway, and this improved documentation could potentially be ascribed to the pathway or surrounding educational efforts.

Relying on the veracity of the medical record, we only had follow up for patients followed in the CHOP system. Follow up after the initial ED encounter increased from 15 to 30% from pre- to post-pathway implementation amongst the 20% of patients for whom follow-up data is available. A large majority of patients in both time periods did not have any documented follow up for chest pain leading us to conclude that patients’ chest pain either resolved or follow up was performed outside the CHOP system. No patients discharged from the ED are known to have died from a cardiac cause. To elaborate further on limitation of the medical record, there is also the possibility that patients’ care may have been discussed with cardiology but was not documented in the ED encounter but we feel these incidences would be rare considering the prompt included in the H&P template.

Our study is the first quality improvement intervention aimed at reducing resource utilization (diagnostic tests and cardiology consultations) for chest pain in the emergency department of an academic tertiary care children’s hospital. While there have been studies focused on intervention in the outpatient setting,4, 8–10, 16 our intervention is unique in focus in the emergency department. Furthermore, it does not routinely recommend diagnostic testing on all pediatric patients with a complaint of chest pain in the ED setting.

Our study does have several limitations. Many hospitals do not have an in house pediatric cardiology fellow or a dedicated cardiology consult service, and therefore our results cannot be generalized to all children’s hospitals or emergency departments. It has been difficult to ascertain the penetrance of our educational efforts and fidelity to the use of the pathway. Lastly, because of the geographically diverse population, follow-up within our system is relatively low and there is a possibility of missed pathology.

Overall, there was low incidence of cardiac disease, and to our knowledge, no undiagnosed cardiac or life-threatening diagnoses. We believe this has led to general acceptance of the pathway in the ED and therefore there is opportunity to further improve upon the pathway. As is the case for most pediatric conditions, efforts at improving quality of care will requiring ongoing measurement and modifications to our existing practice.17 Further directions of study include modifications of the clinical pathway to reduce the frequency of unnecessary cardiology consultation and outpatient follow up. These changes will incorporate feedback from the evaluation of pathway acceptance amongst ED and Cardiology faculty as well as front-line providers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty and staff of the Divisions of Emergency Medicine and Cardiology for their support, as well as the CHOP office of Clinical Quality Improvement.

Funding Source: There was no external funding for this study. Dr. Nandi was supported by the National Institutes of Health research grant T32-HL007915. Dr. Bonafide is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL116427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have indicated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

List of Supplementary Digital Content

Supplementary Digital Content 1.pdf

Supplementary Digital Content 2.docx

References

- 1.Brown JL, Hirsh DA, Mahle WT. Use of troponin as a screen for chest pain in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33:337–342. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eslick GD. Epidemiology and risk factors of pediatric chest pain: a systematic review. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1211–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman KG, Alexander ME. Chest pain and syncope in children: a practical approach to the diagnosis of cardiac disease. J Pediatr. 2013;163:896 e3–901 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleeb SF, Li WY, Warren SZ, Lock JE. Effectiveness of screening for life-threatening chest pain in children. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1062–e1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossner DM, Hirsh DA, Sturm JJ, et al. Cardiac disease in pediatric patients presenting to a pediatric ED with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liesemer K, Casper TC, Korgenski K, Menon SC. Use and misuse of serum troponin assays in pediatric practice. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle WB, Macicek SL, Lindle KA, Kim JJ, Cannon BC. Limited utility of exercise stress tests in the evaluation of children with chest pain. Congenit Heart Dis. 2012;7:455–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verghese GR, Friedman KG, Rathod RH, et al. Resource Utilization Reduction for Evaluation of Chest Pain in Pediatrics Using a Novel Standardized Clinical Assessment and Management Plan (SCAMP) J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angoff GH, Kane DA, Giddins N, et al. Regional implementation of a pediatric cardiology chest pain guideline using SCAMPs methodology. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1010–e1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman KG, Kane DA, Rathod RH, et al. Management of pediatric chest pain using a standardized assessment and management plan. Pediatrics. 2011;128:239–245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter ME. What is value in health care? The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:2477–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hambrook JT, Kimball TR, Khoury P, Cnota J. Disparities exist in the emergency department evaluation of pediatric chest pain. Congenit Heart Dis. 2010;5:285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2010.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selbst SM. Approach to the child with chest pain. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1221–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and policy in mental health. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry T, Zha H, Oster ME, Frias PA, Braunstein M. Utility of a clinical support tool for outpatient evaluation of pediatric chest pain. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2012;2012:726–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuster MA. Measuring Quality of Pediatric Care: Where We've Been and Where We're Going. Pediatrics. 2015;135:748–751. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.