Abstract

As results from single center (mostly kidney) donor studies demonstrate interpersonal relationship and financial strains for some donors, we conducted a liver donor study involving nine centers within the A2ALL-2 Consortium. Among other initiatives A2ALL-2 examined the nature of these outcomes following donation. Using validated measures, donors were prospectively surveyed pre-donation, and 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-donation. Repeated measures regression models were used to examine social relationship and financial outcomes over time and identify relevant predictors. Of 297 eligible donors, 271 (91%) consented and were interviewed at least once. Relationship changes were overall positive across post-donation time points, with nearly one-third reporting improved donor family and spousal/partner relationships and >50% reporting improved recipient relationships. However, the majority of donors reported cumulative out-of-pocket medical and non-medical expenses, which were judged burdensome by 44% of donors. Lower income predicted burdensome donation costs. Those who anticipated financial concerns and who held non-professional positions before donation were more likely to experience adverse financial outcomes. These data support the need for initiatives to reduce financial burden.

Introduction

The increasing need to consider living liver donation as a more expeditious and certain alternative to deceased donor transplantation necessitates ongoing efforts to maximize donor well-being. Beyond commonly considered generic quality of life (often focused on donors’ physical and psychological well-being), the impact of donation on the larger context of donors’ interpersonal life, their relationships and need for adequate social and financial resources before donation, has been considered less often. Social and financial circumstances are important interrelated areas, especially given their potential for reciprocal influence. For example, donation-related financial strains may cause family, spouse/partner, and/or recipient relationship strains within a donor’s social support network. Alternatively, interpersonal relationships may provide a buffer against financial hardship. These issues are especially pertinent to donors who are less financially or socially prepared to handle such strains.

While an increasing body of literature from small, retrospectively studied, single-center, mostly kidney donor cohorts suggests that living donors can experience significant problems related to interpersonal relationships, work and finances, it remains largely unknown whether liver donors are at similar risk.1 To date, the slim literature indicates liver donors’ relationships with recipients or family members can be strained or worsen after donation.2–4 Liver donors may experience more family conflicts related to the decision to donate compared to kidney donors5 and can encounter burdensome donation-related expenses.1,4,6,7

Studies also suggest how donation-related social and financial outcomes may be mutually impactful. Kidney donors can experience financial stresses that could affect their families/spousal relationships due to lost work and wages for both donors and their family caregivers, decreased home productivity, costs for dependent care, transportation, and housing.8–10 A single center study of liver donors demonstrated the potential financial impact on the donor’s social relationships due to the donor using personal/family savings or retirement funds, asking for family/friend loans, declaring bankruptcy, or having a family member get a second job to pay uncovered donation-related medical expenses.7 Insurability is another financial issue potentially impacting donor relationships. Prior reports demonstrate that some donors have difficulties keeping or obtaining health and life insurance.11–13 On the one hand, studies of liver donors could be expected to reveal more frequent and extensive issues given the greater magnitude of their donation surgery compared to kidney donation.5 Alternatively, the higher risks associated with liver donation surgery and the potential for complications may lead to more stringent social and financial selection criteria.

These initial studies led to recommendations for further research7,12–14 to delineate the scope of these issues in liver donors. Thus, it was in part with these intents that we sought to prospectively survey liver donors enrolled in the nine-center Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplant Cohort Study-2 (A2ALL-2). The prospective, repeated measures design facilitated the examination of whether social or financial difficulties arose and persisted during the first two years post-donation. Mutually considering donors’ perceptions of poorer social and financial outcomes allowed identification of their coincidence and examination of shared predictors.

Methods

Study design and cohort

The A2ALL-2 consortium consists of nine North American transplant centers (see Acknowledgements). All centers followed the medical/psychosocial evaluation and exclusion criteria for living liver donor selection now included in current US national policy.15 Centers began prospective study enrollment between February and July 2011 and ended enrollment on January 31, 2014. Individuals were eligible for the present study if they were English-speaking and were scheduled for but had not yet undergone liver donation.

Procedure

Potential liver donors were approached by center clinical staff and informed consent was obtained by center study coordinators before scheduled donation. Centralized data collection survey centers subsequently contacted donors to complete 30–45 minute telephone surveys before (i.e., within 1 month) donation, and 3, 6, 12, and 24 months post-donation. Donors who did not reach an interview time period by the end of study follow-up on July 15, 2014 were administratively censored at that time point (n=29 censored at 1 year and n=66 additionally at 2 years post-donation). Participants were offered $20 for each interview completed. Interviewers used computer-assisted phone interviews for data collection, which ensures interviewers use consistent wording, eliminates independent data entry, and minimizes transcription and coding errors. After initial training, interviewers were monitored for quality assurance and underwent periodic retraining.

The study was approved by the institutional review and privacy boards of the University of Michigan Data Coordinating Center and all participating centers.

Measures

Social relationship outcomes following donation

We chose key items related to donors’ perceptions of interpersonal relationship experiences from donation-specific instruments created and validated previously16 and used extensively in kidney, liver, and bone marrow donation research17–24 (see Table 1 for descriptors and item scales).

Table 1.

Instruments used to assess post-donation relationship and financial domains and their pre-donation predictors

| Measure | Instrument and Scoring | Scoring of instrument or items | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-donation donor family relationships outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| Family relationship quality* | Single item asked about change compared to before donation, rated on 5-point scale from gotten much worse to improved greatly | Improved (scores of 4 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Family relationship more difficult * | Single item asked about change compared to before donation, rated on 10-point scale from not at all true to very true | Agree (scores of 6 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Family expressed gratitude* | Single item asked about gratitude expressed since donation, rated on 10-point scale from not at all true to very true | Agree (scores of 6 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Family holds me in higher esteem* | Single item asked about being held in higher esteem by family since donation, rated on 10-point scale from not at all true to very true | Agree (scores of 6 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

|

| |||

| Post-donation spouse/partner relationships outcome | |||

| Relationship with spouse/partner changed* | Single item asked about change compared to before donation, rated on 5-point scale from gotten much worse to improved greatly | Improved (scores of 4 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

|

| |||

| Post-donation recipient relationships outcomes | |||

| Relationship with recipient* | Single item asked about change compared to before donation, rated on 5-point scale from gotten much worse to improved greatly | Improved (scores of 4 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Donor recipient relationship quality* | Single item asked about overall quality of the relationship with the recipient since donation, rated 5-point scale from poor to excellent | Very good to excellent (scores of 4 or higher) vs. all other responses | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Feel closer to the recipient * | Single item asked about feeling closer to the recipient than before donation, rated on 4-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree | Agree vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Worried about your recipient* | Single item asked about degree of worry, rated on 4-point scale | Worried vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Want more contact with recipient | Single item asked about contact preferences, rated as yes, would like a lot more communication; yes, would like a little more communication, no, would not like more communication | Yes vs. no | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Interactions with recipient* | 7 items asked about qualities of their interactions with recipient as positive or negative on a seven point semantic differential scale (e.g. close vs. distant). | Positive interactions (scores of 5 or higher) vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

|

| |||

| Post-donation financial outcomes | |||

| Cost questions were asked about out of pocket costs not covered by insurance and “Since we last spoke with you …” | |||

| Donation related costs were a burden* | Single item about whether costs were significant financial burden 4 point scale from 1=no, to 2=yes, mild burden, 3=yes, moderate burden or 4=yes severe burden | Yes vs. no | Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Nonreimbursed medical costs | 2 items asked about whether the donor had had medical bills and medication costs | Yes (if either endorsed) vs. no | DiMartini et al. (2007), Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Nonreimbursed non-medical costs | 5 items asked about whether the donor had had lost wages, family/child care, transportation/parking, housing, food | Yes (if any endorsed) vs. no | DiMartini et al. (2007), Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Costs compared to expectations* | Single item, rated as less than expected, more than expected, or about as expected | More than expected vs. not | Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Job and income questions asked “Since we last spoke with you…because of your donation” | |||

| Change in income due to donation | Single item | Decreased vs. not | Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Change or modify your job due to donation | Single item | Yes vs. no | Holtzman et al. (2009) |

| Insurance questions were asked ”Since we last spoke with you… because of the donation” | |||

| Had post-donation problems getting or keeping health insurance | 2 items asked whether donor had trouble getting or keeping health insurance | Yes vs. no (no includes “tried to get/keep insurance; had no problems,” as well as “did not try to get new insurance”) | Adapted from Smith 1986 |

| Had post-donation problems getting or keeping life insurance | 2 items asked whether donor had trouble getting or keeping life insurance | Yes vs. no (no includes “tried to get/keep insurance; had no problems,” as well as “did not try to get new insurance”) | Adapted from Smith 1986 |

| Currently have health insurance | Single item asking about whether donor had medical insurance at the time of interview | Yes have insurance vs. no do not have insurance | Adapted from Smith 1986 |

|

| |||

| Pre-donation predictor variables | |||

| Black Sheep | 2 items asked about whether family generally approving and accepting of donor’s life and if donor had done anything major in their life that family didn’t approve of | Family disapproval present vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Anyone encouraged donor to donate | 9 items asked about whether the recipient, family and extended family or friends had encouraged donation | Anyone encouraged vs. no one encouraged donor | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Anyone discouraged donor to donate | 9 items asked about whether the recipient, family and extended family or friends had discouraged donation | Anyone discouraged vs. no one discouraged donor | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Ambivalence | 7 items asked about whether the donor had lingering feelings of hesitation and uncertainly about whether to donate, rated on 8-point scale, higher scores reflect greater ambivalence | Continuous summary score from 0 (no ambivalence) to 7 (highest ambivalence) | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Positive relationship with recipient | 3 items asked about quality of relationship with recipient, rated on 7-point scale from not at all accurate to very accurate about whether donor feels recipient see eye to eye on most issues, have a warm and close relationship, and generally enjoy each other’s company (excludes those with no relationship with recipient) | Average of items | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Spouse/partner or parents disagree with donation decision | 2 items asked about whether the donor’s spouse/partner or parents supported/disagreed with the donation decision | Yes, disagreed vs. not | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Depression | 9 items asked about severity of symptoms of depression each rated on a scale from 0 to 3 | Continuous summary score from 0 (no depressive symptoms) to 27 (maximal depressive symptoms) | Kroenke et al. 2001 |

| Occupation classification | 1 item asked about pre-donation occupation | Classified as semi-professional/professional vs. technical/clerical or lower position based on the Hollingshead Index of Social Position | Hollingshead 1975 |

| Days donor anticipated being in hospital | 1 item asked about how many days the donor expected to be in the hospital following donation | Number of days | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| How long donor thinks will be off work | 1 item asked about how many months the donor expected to be off work if employed | Less than 1 month, 1–3 months, greater than 3 months and not employed | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| How long donor thinks it will take until feels back to normal | 1 item asked about how long the donor expected to feel back to normal | Less than 1 month, 1–3 months and greater than 3 months | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Concerns over missing work | 1 item asked whether donor had concerns about missing time from work | Yes vs. no | Simmons et al. (1987) |

| Concerns over who will pay for procedure | 1 item asked whether donor had concerns about who will pay | Yes vs. no | Simmons et al. (1987) |

These outcomes were dichotomized in the analyses due to their highly skewed distributions and also because we were interested in identifying subgroups of patients having bad (or good) social and financial outcomes and predictors of those subgroups.

Financial outcomes following donation

Donors’ experiences of financial difficulties from health-related expenses and changes in employment and health- or life-insurance benefits were obtained using the Financial Burden of Donation measure2,3,25,26 (Table 1).

Predictors of social relationship and financial outcomes

Potential predictors included donor demographics, clinical characteristics, donor-recipient relationship, and whether the donor was aware of recipient death before each survey (Table 1). We also tested whether early recipient death (within 3 months after donation) was associated with outcomes.

Additional predictors included pre-donation survey items assessing donor relationship and financial perceptions, expectations, and concerns about post-donation experiences16, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression score (Table 1), pre-donation household income, employment status, and occupation.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics of survey respondents and non-respondents were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Among respondents, we similarly compared completers, those who withdrew consent during the study period (permanent refusers/study dropouts), intermittent refusers (refused one or more interviews but were willing to be called again), and administratively censored donors.

Descriptive statistics were used to examine social and financial outcomes at each time point. Correlation coefficients were calculated between each pair of outcomes at three months and two years post-donation to assess relationships among outcomes shortly after donation and at longest follow-up, respectively.

Outcomes with 10% to 90% prevalence at any time point were chosen for modeling to avoid limited generalizability with sparse outcomes. To investigate changes in social and financial outcomes and identify pre-donation predictors, repeated measures logistic regression models were fit among donors who completed the pre-donation survey and at least one post-donation survey. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with sandwich standard error estimators were used. We started with unstructured covariance structure and then simplified to exchangeable correlation structure if variances and covariances were homogenous. Post-donation time point was retained in the models whether it was statistically significant or not and was used as a categorical variable because many outcomes did not change linearly over time. Overall tests across all time points as well as pairwise tests were conducted to test for significant differences in outcomes over time.

Variable selection was guided by the method of best subsets.27 Final models included predictors that were statistically significant at level 0.05. Categorical variables were included if overall tests were statistically significant or if any pairwise test was statistically significant after using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.28

We also examined whether outcomes differed across centers by conducting overall significance tests for center in the final models. To assess whether adjusting for centers impacted the effect sizes of other predictors, we compared the model results before and after controlling for centers in sensitivity analyses. In financial outcome models, we compared the Canadian center with all U.S. sites combined due to differences in health insurance.

Because 12 donors (5%) included in models were missing pre-donation income, we also conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses by replacing all missing incomes with either the lowest or highest income category.

A prior A2ALL report showed that the majority of donor complications occur in the first weeks following donation29, but to test whether donor complications that occurred beyond one month influenced responses at later time points, we performed sensitivity analyses using complications or re-hospitalization within three months post-donation among those who had clinical data available at three months.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

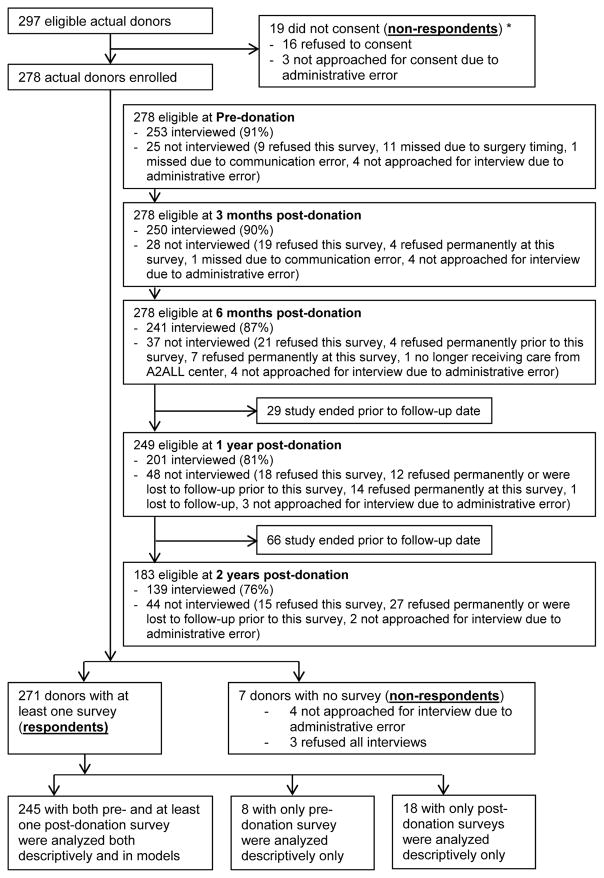

Overall, 91.2% (271/297) of eligible donors were consented and interviewed at least once during the study, with 245 interviewed at both pre- and post-donation, 8 at only pre-donation, and 18 at only post-donation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subject Flow Diagram. This diagram shows the number of eligible actual donors who consented to the study, were interviewed by the survey center, and were included in descriptive analyses and models. Donors were eligible at each time point if they had reached that time point before being administratively censored at the end of study on July 15, 2014. †

Note: There were 30 potential donors consented to the study but did not donate. These 30 subjects were not included in this flow chart.

†The last subject was enrolled January 17, 2014 and the last surgery was performed January 28, 2014 for the same subject.

* The donation statuses for these 19 donor candidates were unknown as they didn’t consent to this study.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 2. We compared available demographics between non-respondents (n=26) and respondents (n=271), and no significant differences were found (p= 0.74, 0.36 and 0.11 for gender, age and race/ethnicity, respectively). Non-respondents were 54% female, 69% non-Hispanic white, 15% Hispanic, and 16% other race/ethnicity, and had a mean age of 34.70 (SD=9.28). Among respondents, there were little differences in demographics and clinical characteristics across completers, permanent refusers, intermittent refusers, and administratively censored donors (all p values ≥ 0.12).

Table 2.

Demographic and donation-related characteristics of respondents (n=271).

| Characteristic | % (n) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Female | 57.2% (155) |

| Age at donation | 36.79 (10.51) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 80.4% (218) |

| Hispanic | 9.2% (25) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 1.8% (5) |

| Asian | 3.0% (8) |

| Black or African American | 2.6% (7) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2.6% (7) |

| Other | 0.4% (1) |

| Education at survey | |

| ≤ high school | 17.3% (47) |

| Vocational or some college | 29.2% (79) |

| College graduate | 28.8% (78) |

| Postgraduate | 18.1% (49) |

| Unknown | 6.6% (18) |

| Married or have long-term partner | 63.1% (171) |

|

| |

| Relation to transplant recipient | |

| First degree relative | 53.1% (144) |

| Parent | 2.2% (6) |

| Child | 36.2% (98) |

| Sibling | 14.8% (40) |

| Spouse/partner | 6.3% (17) |

| Other biological or non-biological relative | 19.2% (52) |

| Unrelated e | 21.4% (58) |

| BMI at donation (kg/m2) | |

| < 18.5 | 1.1% (3) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 35.4% (96) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 46.5% (126) |

| >= 30 | 17.0% (46) |

| Post-donation length of hospital stay (days), Mean (SD) | 5.50 (1.99) |

| Range | 1–24 |

| Donating right lobe vs. left lobe or left lateral segment | 84.1% (228) |

| Number of post-operative complications during the first month post-donation a | |

| 0 | 80.4% (218) |

| ≥ 1 | 19.2% (52) |

| Number of re-hospitalizations during the first month post-donation a | |

| 0 | 91.5% (248) |

| ≥ 1 | 7.7% (21) |

|

| |

| Post-donation recipient vital status from donor reported survey data (n=263) | |

|

| |

| Donor ever aware of recipient death c | 10.3% (27) |

| How long after donation surgery did the recipient die | |

| 0–2.9 months | 5.7% (15) |

| 3–5.9 months | 2.3% (6) |

| 6–11.9 months | 1.5% (4) |

| 12–24 months | 0.8% (2) |

| Weeks post-donation that recipient death occurred (n=27) | 16.11 (18.22) |

|

| |

| Pre-donation predictors from survey data (n=253) | |

|

| |

| Black sheep donor | 28.5% (72) |

| Anyone encouraged donor to donate d | 13.4% (34) |

| Anyone discouraged donor to donate d | 46.6% (118) |

| Ambivalence scale (0=no ambivalence to 7= highest ambivalence) | 1.97 (1.58) |

| Positive relationship with recipient (1=not at all accurate to 7=very accurate) (n=240) | 6.03 (0.97) |

| Spouse/Partner or parents disagree with donor’s decision to donate | 7.5% (19) |

| PHQ-9 Depression (scale of 0= no depressive symptoms to 27=maximal symptoms), Mean (SD) | 1.45 (2.30) |

| Range | 0–16 |

| Employed a | |

| Full time | 65.1% (164) |

| Part time | 15.9% (40) |

| Unemployed or retired | 19.0% (48) |

| Household income b | |

| ≤ $40,000 | 22.8% (55) |

| $40,001 to $80,000 | 27.4% (66) |

| $80,001 to $120,000 | 26.1% (63) |

| > $120,000 | 23.7% (57) |

| Household size, Mean (SD) | 3.28 (1.54) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (2 – 4) |

| Hollingshead categories | |

| semiprofessional/professional | 56.1% (142) |

| technical/clerical or lower position | 43.9% (111) |

| Days donor expects to be in hospital after donation | 5.77 (1.43) |

| How long donor expects to be off work a | |

| less than 1 month | 26.1% (66) |

| 1–3 months | 35.6% (90) |

| greater than 3 months | 21.0% (53) |

| not employed | 16.6% (42) |

| How long donor thinks it will be until he/she feels back to normal a | |

| less than 1 month | 9.5% (24) |

| 1–3 months | 77.9% (197) |

| greater than 3 months | 11.9% (30) |

| Concerns about missing work | 39.5% (100) |

| Concerns about who will pay donation costs | 13.0% (33) |

Missing < 1%;

Missing = 5% (n=12). All other variables had no missing data.

n=5 reported that they did not know recipient vital status at at least one time point.

Among 34 donors encouraged to donate, 27 (79%) were encouraged by first degree relatives, 16 (47%) by spouses or partners, 14 (41%) by other relatives, and 22 (65%) by unrelated people. Among 118 donors discouraged, 55 (47%) were discouraged by first degree relatives, 21 (18%) by spouses or partners, 27 (23%) by other relatives, and 70 (59%) by unrelated people. There were 22 (65% of 34) encouraged and 38 (32% of 118) discouraged by more than one types of people.

There were 5 anonymous donors in this unrelated donor-recipient relationship group.

Prevalence of post-donation social relationship outcomes

At each post-donation time point, 25%–34% of donors indicated their family and spouse/partner (if applicable) relationships improved (Table 3), while the majority (>60%) reported relationships stayed the same compared to pre-donation. Among donors who had interactions with their recipients before the post-donation interview (n=239), a greater proportion, ≥ 54% at every time point, reported improved recipient relationships. Less than 3% reported their relationships with their recipients got worse at any time point. The vast majority of donors reported higher quality recipient relationships post-donation (86%–93% across time points), as well as feeling closer to their recipients (77%–84%). More than 90% reported their interactions with recipients were rewarding, comfortable, easy, positive, relaxed, close, and natural (Table S1).

Table 3.

Social Relationship Outcomes over Time.

| Outcome |

3 Months Post-donation (n=250) % (n) or Mean (SD) |

6 Months Post-donation (n=241) % (n) or Mean (SD) |

1 Year Post-donation (n=201) % (n) or Mean (SD) |

2 Years Post-donation (n=139) % (n) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All donors (n=263; 100%) | ||||

| Family relationship quality a | ||||

| Improved | 33.2% (83) | 31.3% (75) | 29.9% (60) | 25.9% (36) |

| Stayed the same | 63.2% (158) | 66.3% (159) | 64.2% (129) | 71.9% (100) |

| Got worse | 3.6% (9) | 2.5% (6) | 6.0% (12) | 2.2% (3) |

| Family expressed gratitude, % agree b | 82.4% (206) | 82.0% (196) | 77.1% (155) | 74.6% (103) |

| Family holds me in higher esteem, % agree c | 54.4% (136) | 53.3% (128) | 48.8% (98) | 44.9% (62) |

| Family relationship more difficult, % agree d | 7.2% (18) | 4.6% (11) | 7.0% (14) | 7.2% (10) |

|

| ||||

| Donors who are married or live with a long-term partner and spouse/partner is not the recipient (n=162; 61.6%) | n=148 | n=132 | n=106 | n=74 |

| Relationship with spouse/partner, quality a | ||||

| Improved | 33.8% (50) | 29.0% (38) | 29.2% (31) | 33.8% (25) |

| Stayed the same | 61.5% (91) | 62.6% (82) | 65.1% (69) | 62.2% (46) |

| Got worse | 4.7% (7) | 8.4% (11) | 5.7% (6) | 4.1% (3) |

|

| ||||

| Donors whose recipients are alive and donor had interactions with their recipients (n=239; 90.9%)a, * | n=229 | n=213 | n=181 | n=120 |

| Relationship with recipient, quality | ||||

| Improved | 53.7% (123) | 56.8% (121) | 54.1% (98) | 55.8% (67) |

| Stayed the same | 43.7% (100) | 40.4% (86) | 43.1% (78) | 42.5% (51) |

| Got worse | 2.6% (6) | 2.8% (6) | 2.8% (5) | 1.7% (2) |

| Donor recipient relationship quality, % very good to excellent | 92.6% (212) | 88.3% (188) | 86.2% (156) | 88.3% (106) |

| Closer to recipient, % agree | 84.3% (193) | 78.9% (168) | 77.3% (140) | 84.2% (101) |

|

| ||||

| Donors whose recipients are alive (n=247; 93.9%) | n=234 | n=220 | n=184 | n=122 |

| Worried about recipient, % worried | 41.9% (98) | 35.5% (78) | 25.0% (46) | 28.7% (35) |

| Want more contact, % yes d | 33.8% (79) | 32.4% (71) | 31.1% (57) | 32.8% (40) |

Note: sensitivity analyses among only donors who completed all surveys (n=119) showed similar results to those who completed at least one post-donation survey (n=263).

Donors whose recipients died or who were not aware of recipient vital status, or donors who had no interactions with their recipients responded not applicable to these recipient relationship questions.

Missing n=1 at 6 months.

Missing n=2 at 6 months and n=1 at 2 years.

Missing n=1 at 6 months and n=1 at 2 years.

Missing n=1 at 6 months and n=1 at 1 year.

Nearly 42% of donors reported they worried about their recipients at three months after donation, but this proportion was 25%–29% by one to two years post-donation (Table 3). Similarly, the percentages of donors reporting their families expressed gratitude and held them in higher esteem were both highest at three months (82% and 54%, respectively) and were 10% lower at two years post-donation.

Prevalence of post-donation financial outcomes

Endorsement of donation-related adverse financial outcomes was highest at three months post-donation and lowest at one or two years (Table 4). Although health insurance was not required by half of the US centers or the Canadian center, >92% of donors reported having health insurance after donation. Nevertheless, in total, 37% incurred out-of-pocket donation-related medical expenses not covered by insurance including medical bills and medication costs. Some donors continued to experience medical expenses as long as one to two years after donation (12.4% and 9.4%, respectively). Cumulatively, 75% of donors endorsed some non-medical out-of-pocket expenses (i.e., 45% lost wages, 60% transportation, 27% housing, 41% food expenses, and 7% child/family care costs) (Table S2). The proportions of donors who reported donation-related costs were a burden were 40% at three months and 19% at two years post-donation, although cumulatively 44% endorsed this. Almost 12% to 16% of donors, 24% cumulatively, reported donation costs were more than expected, and percentages were similar over the follow-up period.

Table 4.

Financial Outcome Characteristics over Time

| Outcome |

3 Months Post-donation (n=250) % (n) |

6 Months Post-donation (n=241) % (n) |

1 Year Post-donation (n=201) % (n) |

2 Years Post-donation (n=139) % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donation costs were a burden a | 39.6% (99) | 28.4% (67) | 25.4% (51) | 19.4% (27) |

| Incurred medical costs related to donation a,+ | 26.4% (66) | 16.5% (39) | 12.4% (25) | 9.4% (13) |

| Incurred nonmedical costs related to donation a | 73.2% (183) | 36.9% (87) | 20.4% (41) | 13.7% (19) |

| Costs compared to expectations b | ||||

| Less than expected | 8.1% (20) | 13.2% (31) | 11.0% (22) | 14.4% (20) |

| About what was expected | 75.7% (187) | 71.8% (168) | 77.5% (155) | 73.4% (102) |

| More than expected | 16.2% (40) | 15.0% (35) | 11.5% (23) | 12.2% (17) |

| Changed jobs or modified work due to donation c, * | 34.2% (63) | 12.6% (22) | 2.1% (3) | 1.0% (1) |

| Personal income affected by donation d, * | ||||

| Decreased | 41.1% (76) | 8.4% (15) | 4.1% (6) | 1.0% (1) |

| No change | 58.4% (108) | 87.7% (157) | 92.5% (135) | 98.1% (101) |

| Increased | 0.5% (1) | 3.9% (7) | 3.4% (5) | 1.0% (1) |

| Problems getting or keeping health insurance †, e | 2.4% (6) | 2.1% (5) | 1.0% (2) | 3.6% (5) |

| Problems getting or keeping life insurance †, e | 1.2% (3) | 0.8% (2) | 1.0% (2) | 1.4% (2) |

| Currently have no health insurance d | 7.2% (18) | 6.3% (15) | 6.5% (13) | 2.2% (3) |

Note: Note: sensitivity analyses among only donors who completed all surveys (n=119) showed similar results to those who completed at least one post-donation survey (n=263).

Applicable to n=196 donors who were employed at least part-time pre-donation (n=185 at 3 months, n=182 at 6 months, n=146 at 1 year, and n=103 at 2 years post-donation).

Although all Canadian donors are provided with health insurance, Canadian donors were also included in these percentages along with all other (US) donors in the cohort. Donors who did not have health/life insurance and did not try to get new health/life insurance were counted as having no problems (n=17, 14, 12 and 2 for health insurance; n=71, 68, 62 and 41 for life insurance at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years post-donation).

In the US the donation surgery is primarily paid for by the recipients insurance although the donor’s insurance may be changed for some portion. In Canada the governmental insurance pays for the donation surgery.

Missing n=5 at 6 months.

Missing n=3 at 3 months, n=7 at 6 months, and n=1 at 1 year.

Missing n=1 at 3 months, n=8 at 6 months, and n=4 at 1 year.

Missing n=3 at 6 months.

Missing n=4 at 6 months.

Among donors employed at least part time before donation (n=196), 34% reported changing jobs or modifying work because of donation at three months post-donation, but only 1% reported this at two years; however, cumulatively 40% endorsed this. While cumulatively 7% changed to jobs with less manual labor, the majority of donors who endorsed other changes—30% total across all time points—reported changes due to reduced working hours. The proportion reporting decreased income due to donation was 41% at three months and 1% at two years.

Difficulties getting or keeping health or life insurance ranged from 1% to 4% across all time points. Cumulatively, 5% reported difficulties with health insurance and 3% with life insurance. Across the time points, 2% to 7%, and 12% cumulatively, reported no current health insurance. Although Canadian donors have access to governmental health insurance, which covers medical services, they may also have additional insurance through an employer or purchase private insurance to pay for costs not covered by their universal health care such as prescription medications (see Table S3 for separate US and Canadian data).

Correlations between social and financial outcomes

The financial outcomes were significantly correlated with each other at three months post-donation (rφ between 0.23 and 0.41) (Table 5), but had little inter-correlation at two years. Several social relationship outcomes were significantly correlated with each other at both three months and two years post-donation. Improved relationships were inter-correlated among all relationship outcomes; family, spousal/partner and recipient relationships (rφ between 0.21 and 0.56). Donors who reported improved family, spousal, or recipient relationships were also more likely to report their families held them in higher esteem (rφ between 0.16 and 0.39). Those whose families expressed gratitude were also more likely to report their families held them in higher esteem (rφ=0.38 at 3 months and 0.49 at 2 years). However, there was little correlation between financial and relationship outcomes at three months or two years.

Table 5.

Correlations Between Selected Social Relationship and Financial Outcomes at 3 Months and 2 Years Post-Donation

| Financial | Social | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs were a burden | Decreased income due to donation |

Changed/Modified jobs due to donation |

Family relationship improved |

Spousal relationship improved |

Recipient relationship improved |

Worried about recipient | Family holds me in higher esteem |

Family expressed gratitude |

|||

| Financial | Costs were a burden | 1 | 0.417 | 0.234 | 0.089 | 0.081 | 0.037 | −0.056 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 3 Months Post-Donation |

| Decreased income due to donation | −0.052 | 1 | 0.310 | 0.092 | 0.070 | 0.050 | −0.021 | 0.029 | −0.096 | ||

| Changed/Modified jobs due to donation | −0.052 | −0.010 | 1 | 0.027 | −0.060 | −0.030 | −0.016 | 0.079 | 0.019 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Social | Family relationship improved | 0.125 | −0.059 | −0.059 | 1 | 0.428 | 0.420 | −0.020 | 0.390 | 0.192 | |

| Spousal relationship improved | 0.180 | n/a | n/a | 0.561 | 1 | 0.216 | −0.012 | 0.247 | 0.115 | ||

| Recipient relationship improved | 0.049 | −0.113 | −0.113 | 0.422 | 0.421 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.162 | 0.043 | ||

| Worried about recipient | 0.233 | 0.167 | −0.066 | 0.022 | −0.030 | −0.057 | 1 | −0.050 | 0.012 | ||

| Family holds me in higher esteem | 0.161 | −0.087 | −0.087 | 0.359 | 0.347 | 0.304 | 0.111 | 1 | 0.378 | ||

| Family expressed gratitude | 0.025 | −0.175 | −0.175 | 0.233 | 0.078 | 0.227 | 0.098 | 0.493 | 1 | ||

|

|

|||||||||||

| 2 Years Post-Donation | |||||||||||

Correlation coefficients that were significantly different (p<.05) from 0 are bolded. Because some outcomes are only applicable to subgroups of the cohort and because of participant drop-out, each correlation was calculated based on different numbers of observations, which ranged from N=118 to 250 at 3 months and N=64 to 139 at 2 years post-donation. Two correlation coefficients are missing because no donors with a spouse and a job pre-donation (N=57) indicated that they decreased income or changed/modified jobs due to donation at 2 years.

Predictors of social relationship outcomes

Table 6 shows results from repeated measures regression models for social relationship outcomes. The only outcome that showed significant differences across time was whether donors were worried about recipients (overall p<0.001), which was double the odds at three months compared to two years (p=0.002).

Table 6.

Predictors of Social Relationship Outcomes from Repeated Measures Logistic Regression Models.

| Family Relationship Improved (n=245) |

Spouse Relationship Improved b (n=141) |

Recipient Relationship Improved c (n=224) |

Worried about Recipient d (n=231) |

Family Holds me in Higher Esteem (n=245) |

Family Expressed Gratitude (n=245) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Predictors a | OR (95% CI) | P value |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Post-donation time point * | .17 | .20 | .82 | <.001 | .12 | .14 | ||||||

| 3M vs. 2Y | 1.41 (0.98, 2.02) | .06 | 1.40 (0.90, 2.16) | .12 | 1.03 (0.73, 1.46) | .86 | 2.01 (1.27, 3.19) | .002 | 1.49 (1.04, 2.15) | .03 | 1.65 (1.06, 2.57) | .03 |

| 6M vs. 2Y | 1.32 (0.94, 1.87) | .11 | 1.18 (0.73, 1.89) | .47 | 1.14 (0.82, 1.57) | .44 | 1.43 (0.89, 2.28) | .13 | 1.43 (1.04, 1.98) | .03 | 1.50 (0.98, 2.29) | .08 |

| 1Y vs. 2Y | 1.08 (0.76, 1.53) | .67 | 0.89 (0.59, 1.34) | .55 | 1.10 (0.83, 1.47) | .50 | 0.79 (0.48, 1.29) | .35 | 1.16 (0.85, 1.59) | .35 | 1.13 (0.75, 1.72) | .56 |

| Pre-donation psychosocial predictors | ||||||||||||

| Anyone encouraged donor to donate | 2.25 (1.24, 4.07) | .02 | 2.77 (1.19, 6.45) | .008 | ||||||||

| Ambivalence to donate (1 unit increase on scale of 0-no ambivalence to 7-highest ambivalence) | 1.27 (1.09, 1.49) | .003 | ||||||||||

| Positive relationship with recipient | 1.37 (1.00, 1.88) | .049 | ||||||||||

| Demographic/clinical predictors | ||||||||||||

| Donor recipient relationship | .003 | .02 | <.001 | |||||||||

| First degree relative vs. Unrelated | 2.62 (1.28, 5.33) | .007 | 2.09 (1.25, 3.50) | .005 | 5.74 (3.12, 10.57) | <.001 | ||||||

| Spouse/partner vs. Unrelated | 7.15 (2.66, 19.22) | .001 | 1.45 (0.51, 4.15) | .48 | 3.35 (1.10, 10.22) | .03 | ||||||

| Other biological or non-biological relative vs. Unrelated | 1.73 (0.73, 4.06) | .22 | 2.43 (1.29, 4.56) | .006 | 7.90 (3.32, 18.78) | <.001 | ||||||

| Recipient death (time dependent) | na | na | na | na | 0.45 (0.21, 0.92) | .03 | 0.32 (0.14, 0.76) | .04 | ||||

| Female vs. Male | 1.99 (1.23, 3.22) | .005 | ||||||||||

| Age at donation (per 10yrs increase) | 1.34 (1.09, 1.65) | .005 | ||||||||||

| BMI obese vs. not obese | 0.40 (0.21, 0.76) | .003 | ||||||||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; PRIME-MD, primary care evaluation of mental disorders.

For the pairwise tests, 2 year post-donation was chosen as the reference group because we expected donor outcomes at this time point to be closest to pre-donation levels.

Variables tested but not significant: education, race/ethnicity, marital status, hospitalized within 1st month post-donation, donation complications within 1st month, length of hospital stay, anyone discouraged to donate, parents or spouse/partner disagreement with donation decision, PHQ9 score, black sheep donor, days donor thinks he/she will be in hospital, how long donor thinks will be off work or will it take until feels back to normal, concerns over missing work and paying for procedure, employment status, household income, Hollingshead occupation classification.

Spouse relationship improved was modeled among donors who were married or had long-time partner at pre-donation.

Recipient relationship improved was modeled among donors who had interactions with the recipient and whose recipients didn’t die at the interview time point.

Worried about recipient was modeled among donors whose recipients didn’t die at the interview time point.

We modeled improved donor family, spousal and recipient relationships (vs. no improvement) because the percentages of donors expressing poorer relationships were too small for modeling. Donors encouraged by someone to donate were more likely to report improved family relationships, and older donor age was associated with an improved recipient relationship. There were no significant predictors of improved spousal relationship. For each outcome, when donors whose relationship worsened were excluded, the results were unchanged; therefore, these results are mainly driven by the comparison between donors whose relationships improved to those whose relationships stayed the same.

Donors donating to first degree relatives or to their spouses/partners were more worried about their recipients relative to those donating to unrelated recipients (Table 6). Female gender, BMI ≤30, pre-donation ambivalence about donation, and positive recipient relationship were also associated with higher odds of being worried. Donors donating to first degree or other relatives were more likely to report being held in higher esteem and having gratitude expressed by their families, whereas donors whose recipients died were less likely to report such outcomes. An additional predictor of family expressed gratitude was whether anyone had encouraged them to donate.

Early vs. late recipient death and pre-donation financial predictors were not significant in any models.

Predictors of poor financial outcomes

Model results for post-donation financial outcomes are presented in Table 7. Each financial outcome was significantly different across time (overall p<0.001 for each outcome). The odds that costs were a burden at three months were almost three times the odds at two years (p<0.001) and the odds at six months were 1.75 times the odds at two years (p=0.01). Similarly, the odds of decreased income or of job changes or modifications due to donation were large and statistically significantly different at three and six months compared to two years (Table 4).

Table 7.

Predictors of Financial Outcomes from Repeated Measures Logistic Regression Models.

| Costs Were a Burden (n=245) | Decreased Income due to Donation b (n=196) | Changed or Modified Jobs due to Donation b, c (n=196) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Predictors a | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Post-donation time point * | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 3M vs. 2Y | 2.96 (1.96, 4.47) | <.001 | 86.23 (12.82, 580.17) | <.001 | 57.94 (6.83, 491.42) | <.001 |

| 6M vs. 2Y | 1.75 (1.12, 2.72) | .01 | 7.87 (1.05, 58.96) | .01 | 16.07 (1.87, 138.29) | <.001 |

| 1Y vs. 2Y | 1.33 (0.87, 2.04) | .18 | 3.23 (0.38, 27.14) | .21 | 2.30 (0.22, 24.36) | .43 |

| Length of Hospital Stay (per day) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45) | .02 | 1.54 (1.24, 1.91) | <.001 | ||

| Pre-donation predictors | ||||||

| Time you think you will be off work | .02 | .02 | .004 | |||

| 1–3 months vs. < 1 month (and not employed b) | 1.24 (0.69, 2.22) | .46 | 1.13 (0.50, 2.56) | .76 | 0.56 (0.30, 1.07) | .09 |

| > 3 months vs. < 1 month (and not employed b) | 2.77 (1.45, 5.31) | .004 | 2.85 (1.24, 6.56) | .02 | 1.76 (0.88, 3.49) | .13 |

| Concern about who will pay donation costs | 3.00 (1.53, 5.86) | .007 | ||||

| Concern about missing work | 3.05 (1.62, 5.73) | <.001 | ||||

| Household income (per $10,000 increase) | 0.93 (0.87, 0.98) | .009 | ||||

| Hollingshead scale semiprofessional/professional vs. technical/clerical or lower position | 0.53 (0.29, 0.97) | .046 | 0.51 (0.29, 0.88) | .02 | ||

| Ambivalence to donate (1 unit increase on scale of 0-no ambivalence to 7-highest ambivalence) | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) | .008 | ||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

For the pairwise tests, 2 year post-donation was chosen as the reference group because we expected donor outcomes at this time point to be closest to the pre-donation levels.

Variables tested but not significant: donor age at donation, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, BMI (obese vs. not obese), hospitalized within 1st month post-donation, donation complications within 1st month, donor recipient relationship, donor employment status, recipient death (time dependent), days donor think will be in hospital (days), how long donor thinks it will take until feel back to normal, black sheep donor, anyone discouraged or encouraged donor to donate, positive relationship with recipient, spouse/partner or parents disagreement with donation decision, and PHQ-9 score.

Donors who were not employed at pre-donation were excluded from modeling of decreased income and changed/modified jobs due to donation.

Household income was also found significant in predicting jobs changes or modifications (OR=0.94 for every $10,000 increase in income; CI 0.88–1.00); however, it was collinear with Hollingshead categories and thus was not included in Table 5

Donors with longer hospital stay and those who, before donation, anticipated being off work for more than three months were more likely to report post-donation costs were burdensome and that their incomes decreased due to donation. Expected time off work was also associated with donors reporting that they changed or modified jobs due to donation. However, donors expecting time off work for 1–3 months, as compared to <1 month or >3 months, were the least likely to change or modify jobs.

Additional predictors associated with higher odds of adverse financial outcomes were pre-donation concerns about who will pay donation costs, concern about missing work, lower household income, a technical/clerical or lower position as compared to a semi-professional/professional position, and lower level of ambivalence about donating.

Models’ results that assessed complications and re-hospitalizations within three months post-donation rather than one month remained largely the same for all study outcomes, with same direction and similar effects sizes. The sensitivity analyses evaluating the impact of missing incomes (n=12, 5%) showed that all results were unchanged when all missing incomes were replaced with either the lowest or highest income category.

Results were also unchanged when controlling for transplant centers, and the center effect was not significant in any social or financial model. The Canadian center was not significant in any financial models and other covariate effects were similar.

Discussion

Our large multisite study of 271 prospectively surveyed living liver donors establishes the scope and persistence of relationship changes and financial issues following donation. Notably, in contrast to some single center studies of kidney and liver donors which identified worsening of family, spouse, or recipient relationships for up to 10%–20%4,14,30, only a small minority (2%–8%) of our donors endorsed such worsening relationships at any time point. More importantly, in comparison to family/spouse relationships which stayed the same for the majority of donors, more than half reported improved recipient relationships – these changes did not diminish over the two year follow-up period. This is similar to a cross-sectional single center report with 51% of donors endorsing improved recipient relationships following donation.2 Even larger percentages, 77%–93%, reported closer and higher quality relationships with their recipients. Older donors were more likely to experience positive relationship changes with their recipients, perhaps reflecting greater maturity or longer-term relationships.

Positive relationship experiences, such as being held in higher esteem or feeling gratitude from the family, were not sustained over time and decreased by six months post-donation, suggesting that donors may experience less positive affirmation over time. More worrisome were the findings that donors whose recipients died were less likely to report experiencing being held in higher esteem or gratitude from their families—perhaps as the families grieved, the generosity and sacrifice of the donor lost prominence or families were less capable of expressing such feelings in their grief. Although transplant programs are typically attentive to the emotional well-being of donors who have lost their recipients, paying additional attention to the family dynamics may guide the care of donors at this vulnerable time. While a donor’s own recovery is typically the focus of their post-donation clinical visits, inquiring about how their recipient is recovering may identify specific concerns, especially for female and ambivalent donors, that can be addressed in post-donation counseling.

Whereas donors perceived positive experiences in their relationships related to donation, nearly half reported experiencing negative financial outcomes (e.g. burdensome costs, medical expenses, lost wages). Although we believed poorer relationship and financial outcomes might coincide, few endorsed worsening relationships. We also did not find the converse that perceived relationship improvements were associated with less financial stress. While removing financial disincentives is widely supported, donation should at least be “cost neutral”31 so that the most financially vulnerable are not exploited or excluded from donation. However, we found that rather than being cost neutral, the majority of donors reported some out-of-pocket expenses. For 44% of donors, these costs were a significant financial burden at at least one assessment points despite the relatively high average household income of our donors. Not surprisingly those with lower household income were at higher risk for poorer financial outcomes. Many donors were concerned even before donating about missing work (40%) and who would pay for the procedure (13%) and 21% anticipated being off work for >3 months. These donors were subsequently more likely to experience poorer financial outcomes, suggesting they accurately anticipated post-donation financial stresses before donation. Conversely, donors who expected to be off work <1 month were also more likely to experience financial issues, perhaps related to the unrealistic expectations of their return to work time frame. That length of hospital stay was associated with burdensome costs and decreased income further demonstrates the uncertainty of predicting future costs related to donation. Donors in non-professional positions were also more likely to change or modify jobs, perhaps representing the greater physical demands of those positions. Thus, those who are most financially vulnerable were most likely to experience poor financial outcomes.

In an earlier survey, a substantial number of transplant centers reported having donors decline donation due to concerns over lack of health insurance.13 Nevertheless, while most of our donors were insured, 37% reported donation-related medical expenses uncovered by insurance. In January 2014, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act mandated health care coverage for all US residents and made discrimination in the provision of health insurance based on preexisting conditions illegal32, potentially eliminating some insurance barriers. However, complete coverage for all donation services (e.g., no copays or deductibles) still must be addressed. That approximately 10% of our donors were still incurring medical expenses at one and two years post-donation emphasizes that time-limited recipient insurance coverage post-donation is inadequate. A prior study of Canadian donors found 39% had medical expenses not covered by their governmental insurance.2 Additionally, an earlier study using hypothetical liver donor cases found on telephone inquiries that life insurance companies were 50% less likely to offer premium rates to donors compared to other individuals, or were unwilling to underwrite donors.11

We recognize several study limitations. A longer follow-up period may have identified higher rates of health and life insurance problems as was discovered in a study of kidney donors with mean follow-up of eight to nine years.32 In our sample, financial outcomes were self-reported and not verified with actual costs, out-of-pocket expenses, income changes or job modifications. We did not ask specifically about pre-donation costs related to the evaluation which have been demonstrated to be significant.9 The prospective nature of the study allows examination of relationship and financial changes following donation; however, given our naturalistic design, we cannot know that those factors caused changes in the outcome. Too few donors endorsed worsened relationships to explore predictors of these outcomes. Half of enrolled donors did not have 2 year data. Most did not reach that time point by study end and were administratively censored, implying missingness completely at random. Although some did refuse the survey, the similar findings from sensitivity analyses among only completers indicates selection biases are likely minimal. We also note high participant retention through the study.

Future Directions

Gill et al. found the rate of kidney donation declined in the last five years specifically in the three lowest quintiles of US incomes33 reflecting the economic recession. In the two lowest quintiles, spousal donation also declined, perhaps reflecting the economic strain on the household.33 Because financial resources may influence decision to donate, financial initiatives will need to include coverage for expenses beyond donation-related medical costs.31 National Living Donor Assistance Center (NLDAC) support is limited to travel and subsistence expenses and subject to US poverty definitions for donor and recipient household incomes. Transplant programs should emphasize the duration of recovery so donors have a realistic appreciation of potential donation-related costs. Donors may require more assistance with fundraising or other strategies to obtain pre-donation financial support. Donors should be prepared for unexpected financial burdens that can strain finances especially for those who travel greater distances to the transplant program and those with lower household incomes who may also miss work.10 Pilot projects to educate donors, remove disincentives, and possibly expand resources such as NLDAC are suggested as important first steps.34 Projects targeting those most financially vulnerable are needed.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Donor Recipient Interactions over Time

Table S2: Types of Non-Medical Costs over Time

Table S3: Financial Outcomes Characteristics over Time by Canadian vs. USA Donors

Acknowledgments

This is publication number #36 of the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants U01-DK62444, U01-DK62467, U01-DK62483, U01-DK62494, U01-DK62498, U01-DK62531, U01-DK62536, U01-DK85515, U01-DK85563, and U01-DK85587).

Abbreviations

- A2ALL-2

Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplant Cohort Study-2

- NLDAC

National Living Donor Assistance Center

Footnotes

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY (DK62483): PI: Jean C. Emond, MD; Co-Is: Robert S. Brown, Jr., MD, MPH, James Guarrera, MD, FACS, Benjamin Samstein, MD, Elizabeth Verna, MD, MS; Study Coordinators: Theresa Lukose, PharmD, Connie Kim, BS, Tarek Mansour, MB BCH, Joseph Pisa, BA, Jonah Zaretsky, BS.

Lahey Hospital & Medical Center, Burlington, MA (DK85515): PI: Elizabeth A. Pomfret, MD, PhD, FACS; Co-Is: Christiane Ferran, MD, PhD, Fredric Gordon, MD, James J. Pomposelli, MD, PhD, FACS, Mary Ann Simpson, PhD; Study Coordinators: Erick Marangos, Agnes Trabucco, BS, MTASCP.

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK62467): PI: Michael M.I. Abecassis, MD, MBA; Co-Is: Talia B. Baker, MD, Zeeshan Butt, PhD, Laura M. Kulik, MD, Daniela P. Ladner, MD, Donna M. Woods, PhD; Study Coordinators: Patrice Al-Saden, RN, CCRC, Tija Berzins, Amna Daud, MD, MPH, Elizabeth Rauch, BS, Teri Strenski, PhD, Jessica Thurk, BA, MA, Erin Wymore, BA, MS, CHES.

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA (DK62444): PI: Chris E. Freise, MD, FACS; Co-I: Norah A. Terrault, MD, MPH; Study Coordinators: Alexandra Birch, BS, Dulce MacLeod, RN.

University of Colorado, Aurora, CO (DK62536): PI: James R. Burton, Jr., MD; Co-Is: Gregory T. Everson, MD, FACP, Michael A. Zimmerman, MD; Study Coordinator: Jessica Fontenot, BS.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK62498): PI: Robert M. Merion, MD, FACS; DCC Staff: Yevgeniya Abramovich, BA, Charlotte A. Beil, MPH, Carl L. Berg, MD, Abby Brithinee, BA, Tania C. Ghani, MS, Brenda W. Gillespie, PhD, Beth Golden, BScN, Margaret Hill-Callahan, BS, LSW, Lisa Holloway, BS, CCRC, Terese A. Howell, BS, CCRC, Anna S.F. Lok, MD, Monique Lowe, MSI, Anna Nattie, BA, Gary Xia, BA.

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (DK62494): PI: Kim M. Olthoff, MD; Co-Is: Abraham Shaked, MD, PhD, David S. Goldberg, MD, Karen L. Krok, MD, Mark A. Rosen, MD, PhD, Robert M. Weinrieb, MD; Study Coordinators: Debra McCorriston, RN, Mary Shaw, RN, BBA.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA (DK85587): PI: Abhinav Humar, MD; Co-Is: Andrea F. DiMartini, MD, Mary Amanda Dew, PhD, Mark Sturdevent, MD; Study Coordinators: Megan Basch, RN, Sheila Fedorek, RN, CCRC, Leslie Mitrik, BS.

University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, CA (DK85563): PI: David Grant, MD, FRCSC; Co-Is: Oyedele Adeyi, MD, FCAP, FRCPC, Susan Abbey, MD, FRCPC, Hance Clarke, MSc, MD, FRCPC, Susan Holtzman, PhD, Joel Katz, CRC, PhD, Gary Levy, BSc, FRCPC, MD, Nazia Selzner, MD, PhD; Study Coordinators: Kimberly Castellano, BSc, Andrea Morillo, BM, BCh, Erin Winter, BSc.

Virginia Commonwealth University - Medical College of Virginia Campus, Richmond, VA (DK62531): PI: Adrian H. Cotterell, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Robert A. Fisher, MD, FACS, Ann S. Fulcher, MD, Mary E. Olbrisch, PhD, ABPP, R. Todd Stravitz, MD, FACP; Study Coordinators: April Ashworth, RN, BSN, Joanne Davis, RN, Sarah Hubbard, Andrea Lassiter, BS, Luke Wolfe, MS.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition, Bethesda, MD: Edward Doo, MD, James E. Everhart, MD, MPH, Jay H. Hoofnagle, MD, Stephen James, MD, Patricia R. Robuck, PhD, Averell H. Sherker, MD, FRCPC, Rebecca J. Torrance, RN, MS.

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, Steel JL, DiMartini A. Managing the Psychosocial and Financial Consequences of Living Donation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2014;1:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s40472-013-0003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtzman S, Adcock L, Dubay D, Therapondos G, Kashfi A, Greenwood S, et al. Financial, vocational, and interpersonal impact of living liver donation. Liver Transplant. 2009;5:1435–42. doi: 10.1002/lt.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMartini A, Porterfield K, Fitzgerald MG, Dew MA, Switzer G, Marcos A, Tom K. Psychological Profile of Living Liver Donors and Post-Donation Outcomes. In: Weimar W, Bos MA, van Busschbach JJ, editors. Organ Transplantation: Ethical, Legal and Psychosocial Aspects. Towards a Common European Policy. Pabst Science Publishers; Lengerich, Germany: Jan, 2007. pp. 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karliova M, Malagó M, Valentin-Gamazo V, Reimer J, Treichel U, Franke GH, et al. Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: A 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation. 2002;73:1799–804. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudow DL, Chariton M, Sanchez C, Chang S, Serur D, Brown RS., Jr Kidney and liver living donors: a comparison of experiences. Prog Transplant. 2005;15:185–191. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim-Schluger L, Florman SS, Schiano T, O’Rourke M, Gagliardi R, Drooker M, et al. Quality of life after lobectomy for adult liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1593–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigue JR, Reed AI, Nelson DR, Jamieson I, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. The financial burden of transplantation: a single-center survey of liver and kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007;84:295–300. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269797.41202.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, Caulfield T, Boudville N, Prasad GVR, et al. Economic Consequences Incurred by Living Kidney Donors: A Canadian Multi-Center Prospective Study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916–922. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Predonation Direct and Indirect Costs Incurred by Adults Who Donated a Kidney: Findings From the KDOC Study. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2387–2393. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Direct and Indirect Costs Following Living Kidney Donation: Findings From the KDOC Study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:869–76. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nissing MH, Hayashi PH. Right hepatic lobe donation adversely affects donor life insurability up to one year after donation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:843–847. doi: 10.1002/lt.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pomfret EA. Life Insurability of the Right Lobe Live Liver Donor. Liver Transplant. 2005;11:739–40. doi: 10.1002/lt.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang RC, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Garg AX. Insurability of living organ donors: A systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1542–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buer LC, Hofmann BM. How does kidney transplantation affect the relationship between donor and recipient? Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2012;132:41–3. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.10.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) [Last accessed 2/9/16];OPTN Policies, Policy 14: Living donation. Updated 12/1/15. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/

- 16.Simmons RG, Simmons RL, Marine SK. Transaction Books. New Brunswick, N.J., USA: 1987. Gift of Life: The Effect of Organ Transplantation on Individual, Family, and Societal Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dew MA, Switzer GE, DiMartini AF, et al. Psychosocial aspects of living organ donation. In: Tan HP, Marcos A, Shapiro R, editors. Living Donor Organ Transplantation. NY: Taylor and Francis; 2007. pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Switzer GE, Dew MA, Butterworth VA, Simmons RG, Schimmel M. Understanding donors’ motivations: A study of unrelated bone marrow donors. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Switzer GE, Dew MA, Simmons RG. Donor ambivalence and postdonation outcomes: Implications for living donation. Transpl Proc. 1997;29:1476. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Switzer GE, Myaskovsky L, Goycoolea JM, Dew MA, Confer DL, King R. Factors associated with ambivalence about bone marrow donation among newly recruited unrelated potential donors. Transplantation. 2003;75:1517–1523. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000060251.40758.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Switzer GE, Dew MA, Goycoolea JM, Myaskovsky L, Abress L, Confer DL. Attrition of potential bone marrow donors at two key decision points leading to donation. Transplantation. 2004;77:1529–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000122219.35928.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myaskovsky, Dew MA, Crowley-Matoka M, Unruh M, DeVito Dabbs A, Shapiro R, et al. Is donating a kidney associated with changes in health habits? Am J Transplant. 2010;10(S4):536. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corley MC, Elswick RK, Sargeant CC, Scott S. Attitude, self-image, and quality of life of living kidney donors. Nephrol Nurs J. 2000;27:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, DeVito Dabbs AJ, Zuckoff A, Tan HP, McNulty ML, et al. Preventive intervention for living donor psychosocial outcomes: Feasibility and efficacy in a randomized controlled trial. Am J Transplant. 2013;10:2672–84. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMartini A, Cruz R, Dew MA, Fitzgerald MG, Chiapetta L, Myaskovsky L, et al. Motives and decision making of potential living liver donors: Comparisons between gender, relationships and ambivalence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:136–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith MD, Kappell DF, Province MA, et al. Living-related kidney donors: a multicenter study of donor education, socioeconomic adjustment, and rehabilitation. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;8:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(86)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrell FE. Springer Series in Statistics. New York, NY: Springer; 2001. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3. Sparky House Publishing; Baltimore, Maryland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abecassis MM, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Freise CE, Rodrigo DR, Samstein B, et al. Complications of Living Donor Hepatic Lobectomy—A Comprehensive Report. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reimer J, Rensing A, Haasen C, Philipp T, Pietruck F, Franke GH. The impact of living-related kidney transplantation on the donor’s life. Transplantation. 2006;81:1268–73. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000210009.96816.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delmonico FL, Martin D, Domínguez-Gil B, Muller E, Jha V, Levin A, et al. Living and Deceased Organ Donation Should Be Financially Neutral Acts. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1187–1191. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyarsky BJ, Massie AB, Alejo LJ, Van Arendonk KJ, Wildonger S, Garonzik-Wang JM, et al. Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2168–2172. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill J, Dong J, Gill J. Population income and longitudinal trends in living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:201–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salomon DR, Langnas AN, Reed AI, Bloom RD, Magee JC, Gaston RS for the AST/ASTS Incentives Workshop Group (IWG) AST/ASTS Workshop on Increasing Organ Donationin the United States: Creating an “Arc of Change” From Removing Disincentives to Testing Incentives. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1173–1179. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9 Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollingshead AA. Unpublished manuscript. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Four-factor index of social status. Available online at : http://www.yale.edu/sociology/yjs/yjs_fall_2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Donor Recipient Interactions over Time

Table S2: Types of Non-Medical Costs over Time

Table S3: Financial Outcomes Characteristics over Time by Canadian vs. USA Donors