Abstract

Background

People with serious mental illness have high rates of obesity and related medical problems, and die years prematurely, most commonly from cardiovascular disease. Specialized, in-person weight management interventions result in weight loss in efficacy trials with highly motivated patients. In usual care, patient enrollment and retention are low with these interventions, and effectiveness has been inconsistent.

Objective

To determine whether computerized provision of weight management with peer coaching is feasible to deliver, is acceptable to patients, and is more effective than in-person delivery or usual care.

Design

Mixed-methods randomized controlled trial.

Participants

Two hundred seventy-six overweight patients with serious mental illness receiving care at a Veterans Administration medical center.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to 1) computerized weight management with peer coaching (WebMOVE), 2) in-person clinician-led weight services, or 3) usual care. Both active interventions offered the same educational content.

Main Measures

Body mass index; and feasibility and acceptability of the intervention.

Key Results

At 6 months, in obese patients (n = 200), there was a significant condition by visit effect (F = 4.02, p = 0.02). The WebMOVE group had an average estimated BMI change from baseline to 6 months of 34.9 ± 0.4 to 34.1 ± 0.4. This corresponds to 2.8 kg (6.2 lbs) weight loss (t = 3.2, p = 0.001). No significant change in BMI was seen with either in-person services (t = 0.10, p = 0.92), or usual care (t = −0.25, p = 0.80). The average percentage of modules completed in the WebMOVE group was 49% and in the in-person group was 41% (t = 1.4, p = 0.17). When non-obese patients were included in the analyses, there was a trend towards a condition by visit effect (F = 2.8, p = 0.06). WebMOVE was well received, while the acceptability of in-person services was mixed.

Conclusions

Computerized weight management with peer support results in lower weight, and can have greater effectiveness than clinician-led in-person services. This intervention is well received, and could be feasible to disseminate.

KEY WORDS: mental illness, obesity, counseling, information technology, comparative effectiveness

INTRODUCTION

Serious mental illness (SMI) includes common disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that often result in substantial disability and very high healthcare costs. Between 40% and 60% of individuals with SMI are obese, compared to about 30% of the general population.1,2 Obesity has detrimental health consequences, including cardiovascular morbidity and reduced life expectancy.3 Fortunately, the harmful effects of obesity are reversible with even modest weight loss. Treatment guidelines recommend that individuals with SMI who are overweight should be offered evidence-based weight loss interventions, including psychosocial interventions.4 In 2014, a call to action was published by leading international experts and patient stakeholders asking for policies mandating treatments that addressed obesity in this population.5

The Veterans Administration (VA) has disseminated an in-person weight management program, the MOVE Weight Management Program for Veterans (MOVE). Participation is less than 5% of eligible veterans,6 average weight loss is minimal, 1–2 pounds,6 and MOVE is more likely to be utilized by those with a body mass index (BMI) above 30, indicating obesity.6–8 Since people with SMI often have cognitive deficits, limited literacy, and challenging social situations, interventions need to be tailored for this population. Individual- and group-based behavioral interventions tailored for SMI have repeatedly been shown to result in weight reduction,9–15 though a recent study showed no benefit of intervention.16 Successful interventions for weight include psychoeducation focused on nutritional counseling, behavioral self-management including goal-setting and self-monitoring of food and activity levels, and regular weigh-ins.4 Although weight loss with these interventions is often modest, without interventions the average person continues to gain weight. Even weight loss of a few pounds has been associated with health benefits, including improved cardiovascular health. 17–25

Despite widespread recognition of the importance of weight loss in individuals with SMI, the availability and use of tailored evidence-based weight loss interventions is very low. Barriers include patient issues (e.g., reluctance to participate in groups, limited transportation to the clinic) and organizational issues (e.g., shortage of clinician time).26 Internet and computer technology has the potential to overcome these barriers and increase the feasibility, effectiveness, and reach of weight services. While people with SMI can have difficulty using standard internet and computer applications,27 there has been proven success with specialized audio-assisted interfaces that meet their needs.28,29 One approach that has strengthened the ongoing use of technology-delivered interventions has been to combine technology with human interaction and social connection.30,31

The purpose of this study was to determine whether computerized provision of weight management with peer coaching could be more effective than in-person delivery or usual care, and would be feasible to deliver and acceptable to patients. Both computerized (WebMOVE) and in-person programs (MOVE SMI) were tailored to SMI. Due to barriers to utilization of in-person services, we hypothesized that WebMOVE would result in lower patient weight, compared with in-person delivery or usual care, and would be feasible to deliver and acceptable to patients.

METHODS

Participants

Data were collected at mental health clinics within the Greater Los Angeles VA medical center. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with psychosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder; were 18 years or older; were prescribed an antipsychotic medication; had either a BMI above 30 (obese) or a BMI of 28–30 (overweight) with self-reported weight gain of at least 10 pounds in the last 3 months; and received medical clearance to participate from a physician if they received a score ≥ 1 on the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q).32 Exclusion criteria included a history of bariatric surgery; pregnant or nursing mothers; dementia; current participation in weight loss groups; psychiatric hospitalization during the prior month; or very limited control over food preparation. Limited control was defined as more than 50% of an individual’s lunches or dinners being eaten at a place where they had no choice in what or how much was served.

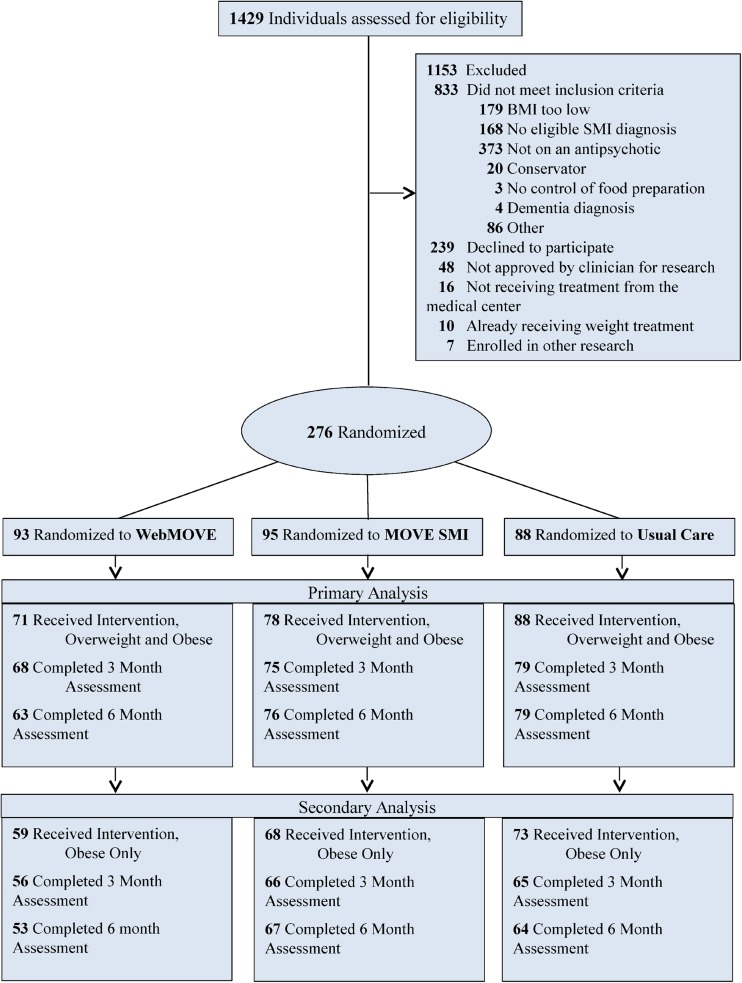

For recruitment, we obtained a list of patients who met inclusion criteria for psychiatric diagnosis, age, and psychotropic medication. Study flyers were also posted in mental health clinics. A total of 1429 individuals were screened for eligibility, and 19% were eligible, interested, enrolled, and randomized (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the VA Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for randomized controlled trials depicting the flow of patients through eligibility, assessment, randomization, intervention, and outcome analyses. CONSORT Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Intervention Conditions

Following baseline assessment, patients were randomized to one of three intervention conditions: WebMOVE, MOVE SMI, or usual care. Randomization was stratified by the weight gain liability of prescribed antipsychotic medications (low, medium, high). Clozapine and olanzapine were classified as high weight gain liability medications. Chlorpromazine, iloperidone, paliperidone, risperidone, quetiapine, sertindole, and thioridazine were moderate weight liability medications. Although not an antipsychotic, valproic acid was also considered in the moderate category. All other available antipsychotic medications were low/no weight liability medications. Once randomized, participants were given instructions for how to begin their intervention. The two active intervention conditions were available for 6 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intervention Schedule by Treatment Condition

| WebMOVE | MOVE SMI | Usual care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 Online modules + weekly peer coaching | 8 In-person individual sessions | 16 In-person group sessions | 1 Educational handout on weight loss | |

| Study month 1 | Recommended 2 modules per week (1 nutritional focus, 1 physical exercise focus); weekly telephonic coaching | 4 Weekly sessions: review diet and exercise habits and introduce behavioral goal setting | No sessions | |

| Study months 2–4 | 3 Monthly sessions: provide ongoing support and motivational assistance in addressing goals and review of material/skills presented in group sessions. | 12 Weekly sessions: didactic review of nutritional and physical activity topics. Assistance in setting weekly goals for weight loss and physical activity. Weigh-in and discussion of successes and challenges. | ||

| Study months 5–6 | 1 Monthly session (month 5): provide ongoing support and motivational assistance in addressing goals and review of material/skills presented in group sessions. | 4 Bi-weekly review sessions: review major concepts and strategies. | ||

WebMOVE is a weight management program developed for this study, and includes 1) internet browser-based provision of 30 interactive educational modules, tracking of activity and weight, and individualized homework, plus 2) weekly telephonic peer coaching. The computerized program is based on the in-person MOVE SMI program developed by Goldberg and colleagues (Table 2). Participants were provided a pedometer and instructed on how to use the online system. Participants were encouraged to complete two online modules per week; each module could be completed in 30 min. The online program was tailored for cognitive deficits seen in this population. This included minimal text, all text read aloud, a fifth grade reading level, explicit navigational aids, and simple presentation of information. The program included audio- and text-based education, video, pedometer tracking, goal setting, homework, automated diet plans, and quizzes. The online system was accessible from kiosks at VA clinics (touchscreen computers with headphones) or anywhere there was internet access. A peer wellness coach (i.e., individuals with lived experience with mental illness) was assigned to each WebMOVE participant. Weekly manualized peer coaching was delivered by phone and emphasized a strengths-based approach with motivational interviewing. The peer coaching manual was designed to support consistent delivery of services across coaches.30 Coaches received didactic training in the manual, experiential training in coaching, and weekly individual supervision from a psychologist.

Table 2.

Nutrition and Physical Activity Topics Covered in WebMOVE and MOVE SMI

| Nutritional focus | Physical activity focus |

|---|---|

| Introduction to good nutrition | Introduction to physical activity |

| Portion control and serving sizes | Basics of becoming physically active: how to get started |

| Water and liquid calories | Benefits of walking |

| Reading food labels | Stretching |

| Fruits and vegetables | Barriers to exercise |

| Sodium and fats | Benefits of exercise |

| Making healthy choices | Exercising safely |

| Stop & Think About What You’re Eating: Using the traffic light method | Warming up and cooling down |

| Grains and carbohydrates | Exercising on a budget |

| Fast food | Making time to exercise |

| Effective tips for eating at home and away | Medical conditions, pain, and exercise |

| Eating control techniques | Medications and exercise |

MOVE SMI is an in-person weight management program led by a master’s level mental health clinician.16 The program includes 24 sessions (8 individual and 16 group), each lasting 60 min. The in-person program utilizes handouts, motivational techniques, visual learning aids, behavioral rehearsal, repetition, goal setting, homework, and diet plans. The MOVE SMI group leaders received weekly group supervision from a psychologist.

Usual care consisted of one educational handout on the benefits of weight loss, given to participants after randomization. Participants were allowed to take advantage of standard services available at the medical center, which included MOVE weight management (not tailored for people with SMI).

Assessments and Outcome Measurements

Participants completed three in-person quantitative assessments (baseline, 3 and 6 months) conducted by an assessor blind to randomization assignment. The effectiveness of interventions was assessed at 6 months using baseline demographics, weight, height, and calculated body mass index (BMI). Participants also self-reported their weight 6 months prior to baseline. WebMOVE module completion was electronically recorded, peer coaching calls were documented, and MOVE SMI session attendance was collected.

At 6 months, participants randomized to WebMOVE or MOVE SMI were invited to complete a brief qualitative interview, which provided data on intervention feasibility and acceptability. Invitations were stratified by intervention condition. Participants were invited to participate until data saturation was achieved.33 Participants were paid $15 for each research assessment. Mid-study, it came to our attention that many subjects were traveling an hour or more to complete research assessments. Given that, payments to participants were increased to $20 for the 3-month and $35 for the 6-month assessment to compensate them for their time. Participants were paid $10 for the qualitative interview. To increase the generalizability of results, no compensation was provided for receiving interventions.

Statistical Analyses

Quantitative analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All randomized participants who received the intervention as randomized were included in the primary analyses, regardless of the number of assessments completed. Receiving the intervention as randomized was defined as participation in one or more modules/sessions (WebMOVE or MOVE SMI) or receipt of the educational handout (usual care). Receipt of any intervention was critical, as we did not want to include individuals who enrolled solely for the baseline assessment incentive but had no intention of taking part in any weight intervention. We compared baseline characteristics between intervention groups using F-tests for continuous and χ2 analysis for categorical variables. A mixed effects repeated measures model was used to compare BMI outcomes between intervention conditions over time, with treatment condition, assessment visit, and condition by visit as independent variables. The model also included BMI 6 months prior to baseline as a covariate to take into account the weight trajectory a participant was on when entering the study. Secondary analyses excluded participants with BMI of 28–30 (overweight), leaving only those with BMI > 30 who received the intervention as randomized. This secondary analysis addressed the question of intervention effectiveness for obese participants. Intervention effectiveness for obese patients was further examined by calculating the change in weight from baseline to 6 months. A χ2 analysis compared the number of participants who lost 5% or more of baseline weight by 6 months by condition.

All qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed. ATLAS.ti was used for management and analysis. Following completion of interviews and review of transcripts, a preliminary codebook was developed collaboratively, focused on feasibility and acceptability of the treatments. Using the codebook, transcripts were independently coded by research assistants trained in ATLAS.ti. During coding, research assistants and an expert in ATLAS.ti met regularly to elaborate and adjust the codebook, using the constant comparison analytic approach,34 involving an iterative process of comparison and categorization, facilitated by tools available in the software.

RESULTS

Participants

Enrollment began in March 2012, and 6-month follow-up data collection ended in July 2014; 276 participants were randomized. In the WebMOVE group, 22 participants did not attempt any online modules, and in the MOVE SMI group, 17 did not attend any sessions. This left 237 participants who received an intervention as randomized and who formed the analytic sample for primary analysis of intervention effectiveness.

Eighty-four percent of the sample (200/237) had BMI > 30 (obese) at baseline and received the intervention as randomized. There was no significant difference among the three intervention conditions in the number of obese participants (χ2 = 0.7; p = 0.70). The group of 200 obese participants who received the intervention as randomized formed the analytic sample for the secondary analysis of intervention effectiveness. The sample demographics are presented in Table 3. A total of 24 randomized to WebMOVE and 24 randomized to MOVE SMI completed the qualitative interview at 6 months.

Table 3.

Demographics of Participants Who Received the Intervention by Weight Category and Treatment Condition

| Received intervention, overweight and obese (n = 237) | Received intervention, obese only (n = 200) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WebMOVE | MOVE SMI | Usual care | Test of difference | WebMOVE | MOVE SMI | Usual care | Test of difference | ||

| n = 71 | n = 78 | n = 88 | n = 59 | n = 68 | n = 73 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Age, years | 55.5 ± 9.2 | 53.8 ± 10.1 | 54.2 ± 9.9 | F = 0.61; p = 0.55 | 55.8 ± 9.0 | 54.2 ± 10.0 | 53.7 ± 9.8 | F = 0.87; p = 0.42 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Gender (male) | 68 (95.8%) | 72 (92.3%) | 86 (97.7%) | Fisher’s; p = 0.29 | 56 (94.9%) | 63 (92.7%) | 71 (97.3%) | Fisher’s; p = 0.47 | |

| Race | χ2 = 16.1; p < 0.19 | χ2 = 27.00; p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 31 (43.7%) | 30 (38.5%) | 33 (37.5%) | 25 (42.4%) | 28 (41.2%) | 25 (34.3%) | χ2 = 2.6; p = 0.3 | ||

| African-American | 30 (42.3%) | 32 (41.0%) | 45 (51.1%) | 25 (42.4%) | 26 (38.3%) | 42 (57.5%) | χ2 = 3.4; p = 0.2 | ||

| American Indian | 4 (5.6%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (6.8%) | 0 | 0 | χ2 = 9.7; p < 0.01 | ||

| Asian | 0 | 6 (6.8%) | 2 (2.3%) | 0 | 3 (4.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | χ2 = 3.9; p = 0.1 | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.7%) | χ2 = 3.2; p = 0.2 | ||

| Multiple races | 3 (4.2%) | 5 (6.4%) | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (3.4%) | 5 (7.4%) | 0 | χ2 = 5.9; p = 0.05 | ||

| No response | 3 (4.2%) | 7 (9.0%) | 2 (2.3%) | 3 (5.1%) | 6 (8.9%) | 3 (4.1%) | χ2 = 1.5; p = 0.5 | ||

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 8 (11.3%) | 14 (18.0%) | 9 (10.2%) | χ2 = 2.5 p = 0.29 | 8 (13.6%) | 12 (17.7%) | 9 (12.3%) | χ2 = 0.86; p = 0.65 | |

| Education (highest degree) | Fisher’s; p = 0.63 | Fisher’s; p = 0.33 | |||||||

| Less than high school | 1 (1.4%) | 5 (6.4%) | 4 (5.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (5.9%) | 4 (5.5%) | |||

| High school or some college | 46 (64.8%) | 46 (59.0%) | 56 (63.6%) | 40 (67.8%) | 39 (57.4%) | 52 (71.2%) | |||

| College 2- or 4-year degree | 21 (29.6%) | 25 (32.1%) | 22 (25.0%) | 15 (25.4%) | 24 (35.3%) | 15 (20.6%) | |||

| Some grad school or grad degree | 3 (4.2%) | 2 (2.6%) | 4 (4.6%) | 3 (5.1%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (2.7%) | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Body mass index | 33.9 ± 4.5 | 35.0 ± 5.2 | 34.4 ± 5.6 | F = 0.91; p = 0.40 | 35.0 ± 4.9 | 35.8 ± 4.95 | 35.5 ± 5.0 | F = 0.47; p = 0.6 | |

Intervention Effectiveness

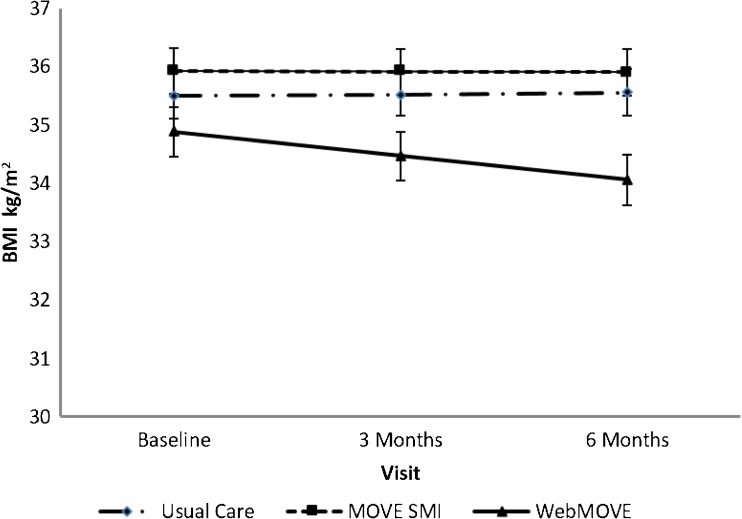

Primary analyses indicated that between baseline and 6 months, in overweight and obese patients, there was a trend towards a condition by visit effect (F = 2.8, p = 0.06). Secondary analyses indicated that between baseline and 6 months, in obese patients only, there was a condition by visit effect (F = 4.0, p = 0.02; Fig. 2). In the WebMOVE group, the model estimated an average BMI change from baseline to 6 months of 34.9 ± 0.43 to 34.1 ± 0.43. This corresponds to a 2.8-kg (6.2 lbs) weight loss (t = 3.3, p = 0.001) in the WebMOVE group. No substantial change in BMI was seen in the MOVE SMI group, for which the average BMI change from baseline to 6 months was 35.9 ± 0.40 to 35.9 ± 0.40 (t = 0.10, p = 0.92), which corresponds to no change in weight. There was also no substantial change in the usual care group, where the average BMI change from baseline to 6 months was 35.5 ± 0.38 to 35.6 ± 0.40, which corresponds to a 0.30-kg (2.20 lbs) weight gain (t = −0.25, p = 0.80).

Figure 2.

Change in body mass index over 6 months by treatment condition.

In obese patients, 52/200 (26%) lost 5% or more of baseline weight by 6 months. The probability of losing 5% or more of weight was significantly different among the three treatment conditions (χ2 = 6.4; p = 0.04). In the WebMOVE group, 22/59 (37%) lost 5% or more of body weight, while 12/68 (18%) of the MOVE SMI group and 18/73 (25%) of the usual care group lost 5% of weight by 6 months. Patients were significantly more likely to lose 5% or more of body weight in the WebMOVE group than in the MOVE SMI group (χ2 = 6.2; p = 0.01). Other pairwise comparisons of conditions were non-significant.

In terms of retention in treatment, the average number of modules completed in WebMOVE was 14.7 (SD = 12.2), which is 49% of 30 modules, and the average number of sessions completed in MOVE SMI was 9.7 (SD = 6.2), which is 41% of the 24 sessions (t = 1.36 p = 0.17). There was a significant difference in the number of participants who completed 100% of the intervention sessions/modules: in WebMOVE, 18 participants (31%) completed the intervention, while in MOVE SMI, no participants (0%) completed the intervention (χ2 = 24.2; p < 0.0001). WebMOVE participants received, on average, 7.9 (SD = 6.8) peer coaching calls. Patients who were obese completed more modules than patients who were less than obese, in both the WebMOVE (14.7 ± 12.2 vs. 9.8 ± 11.3, p = 0.004) and MOVE SMI groups (9.7 ± 6.2 vs. 5.5 ± 6.2, p = 0.18).

Intervention feasibility and acceptability

Qualitative analysis revealed several main themes. Overall, the WebMOVE intervention was well received. One category of themes centered on the helpfulness of educational modules and pedometers. Speaking about modules, participants stated, “They kept me mindful” and “I liked what I was learning, I got a lot out of it.” Another main theme was positive reaction to the peer coaches. One participant said, “Without one-on-one coaching, the web program would not have been as good.” Another said, “[The coach] would explain things differently to me … that was the most helpful.” Less prevalent themes were difficulty in accessing a computer and the desire for a walking group.

The MOVE SMI intervention received a mixed response. One major theme was participants’ discomfort with a group format. Participants stated, “It’s just I don’t like to be around people” and “I get sluggish and I’d rather not be in a group.” Others recommended individual sessions instead of groups. Another main theme was transportation as a barrier. Participants stated, “Bus fare makes it hard” and “It’s kind of hard for me [to get to appointments], to come every week and commute, travel.” These themes provided potential explanation for results. For example, there was significantly higher retention in treatment for the WebMOVE group compared to MOVE SMI. The themes around discomfort with a group setting and transportation as a barrier may provide an explanation for this finding.

DISCUSSION

In this study, computerized provision of individualized diet and exercise education, combined with telephonic peer coaching, resulted in lower weight in obese patients with serious mental illness. Consistent with prevailing care, the usual care group received few services and had no weight loss. Somewhat surprisingly, in-person weight services also produced no substantial change in weight. While some effectiveness trials of in-person interventions in people with SMI have found weight loss, others have not. Similar to prior research,35 this study found substantial barriers to patients’ use of in-person services. Group participation and transportation were both challenges, and people assigned to in-person services had lower rates of service use than those assigned to computerized or peer services. To our knowledge, this randomized controlled trial is the first study of the effectiveness of computerized tools and telephonic coaching on weight in people with SMI. Although the mean weight loss at 6 months was modest, more than a third of those in WebMOVE lost 5% or more of baseline weight. This modest weight loss can produce significant health benefits.17–25

There has been very little research in populations with SMI regarding factors associated with success of weight loss interventions. In this study, the intervention was most effective within the population of patients who were obese at baseline. Motivation for change is believed to be critical for weight loss, and we found this to be true within this population. Being overweight is now normative status in the United States, particularly in populations within lower socioeconomic status. It can be difficult for people who are not obese to see the importance of changing behavior and losing weight. While there are positive health effects from weight loss in a non-obese population, implementing services in this population may require substantial effort to increase readiness to change.

There have been concerns that people with SMI cannot make productive use of technology or computerized interventions because of cognitive deficits, socioeconomic factors, limited literacy, or just a general belief that they are too disabled. In this study, this was not the case. Patients enjoyed the computer interaction and the opportunity to engage with this program, and lost weight. Notably, the computer interfaces in this study were specifically designed to meet human factors needs of this population, and the interface placed a priority on being individually tailored and engaging. While we cannot disentangle the effects of computerized service delivery and peer support, both were viewed positively by participants.

This study has limitations. First, it was conducted at one VA medical center in an urban metropolitan area. Although the clinical status of patients with SMI does not vary substantially across clinical sites, sites do vary markedly in contextual factors, such as rural–urban differences, disability compensation, insurance generosity, and access to healthcare. A computerized and peer coaching intervention might be feasible across varying health services contexts, but this needs to be the focus of further research. Second, although the computer and peer coaching intervention was successful in recruiting patients, lowering barriers to participation, and maintaining patient engagement, there was a large proportion of overweight patients with SMI who declined to participate. Future interventions should also focus “upstream” in an effort to increase routine screening and enhance readiness for change.

In summary, online weight management with peer coaching provided educational content and decision support that was tailored to individuals with mental illness or cognitive deficits, and was convenient and patient-centered. Patients who were obese and who were willing to participate in a weight loss program lost more weight with this online program than with in-person clinician-led groups or usual care. Integration of peers and technology into care was well received. It has proven very difficult or impossible to broadly disseminate in-person interventions for weight in people with serious mental illness, in part because of high levels of expensive clinician time required for interventions and transportation barriers when patients need frequent clinic visits. An intervention delivered by computer with telephonic peer coaching should be much more feasible for dissemination to patients. The program could be readily disseminated for use by kiosk, computer browser, or mobile device. Currently, the VA has plans to include WebMOVE in the VA Virtual Medical Center, and has funded a project to optimize WebMOVE for delivery via smartphone. Online and mobile delivery, tailored for this population, has the potential to enhance access to services that help patients improve their diet and activity, lead to lower weight, and thereby reduce morbidity and mortality. While this study’s approach is designed for a population with serious mental illness, it is possible that it could be effective in other populations with cognitive disabilities, inconsistent literacy, or socioeconomic challenges.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 09–083; PI: Young), the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH090207; PI: Young), the VA Desert Pacific MIRECC, the VA Capitol Healthcare Network MIRECC, and the VA HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation and Policy. We acknowledge Jim O’Halloran, PhD, at NeuroComp Systems for his contributions to the development of the WebMOVE system. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government, or other affiliated institutions.

Earlier versions of these results were presented in concurrent research sessions at the Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting in Washington DC in 2016, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research Conference in Philadelphia PA in 2015, and a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research webinar in 2016.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickerson FB, Brown CH, Kreyenbuhl JA, Fang L, Goldberg RW, Wohlheiter K, Dixon LB. Obesity among individuals with serious mental illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(4):306–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Overweight Atlanta, Gerogia: CDC / National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. Accessed May 20, 2016.

- 3.Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, Buchanan RW, Casey DE, Davis JM, Kane JM, Lieberman JA, Schooler NR, Covell N, Stroup S, Weissman EM, Wirshing DA, Hall CS, Pogach L, Pi-Sunyer X, Bigger JT, Jr, Friedman A, Kleinberg D, Yevich SJ, Davis B, Shon S. Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1334–1349. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, Lehman A, Tenhula WN, Calmes C, Pasillas RM, Peer J, Kreyenbuhl J. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischhacker WW, Arango C, Arteel P, Barnes TR, Carpenter W, Duckworth K, Galderisi S, Halpern L, Knapp M, Marder SR, Moller M, Sartorius N, Woodruff P. Schizophrenia—time to commit to policy change. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl 3):S165–S194. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littman AJ, Boyko EJ, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Evaluation of a weight management program for veterans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E99. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funderburk JS, Arigo D, Kenneson A. Initial engagement and attrition in a national weight management program: demographic and health predictors. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2015:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Del Re AC, Maciejewski ML, Harris AH. MOVE: weight management program across the Veterans Health Administration: patient- and facility-level predictors of utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:511. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Berry S, Mahmoud R. Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):205–212. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamali M, Kelly BD, Clarke M, Browne S, Gervin M, Kinsella A, Lane A, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E. A prospective evaluation of adherence to medication in first episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jean-Baptiste M, Tek C, Liskov E, Chakunta UR, Nicholls S, Hassan AQ, Brownell KD, Wexler BE. A pilot study of a weight management program with food provision in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;96(1–3):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon JS, Choi JS, Bahk WM, Yoon Kim C, Hyung Kim C, Chul Shin Y, Park BJ, Geun OC. Weight management program for treatment-emergent weight gain in olanzapine-treated patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: A 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):547–553. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber M, Wyne K. A cognitive/behavioral group intervention for weight loss in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu MK, Wang CK, Bai YM, Huang CY, Lee SD. Outcomes of obese, clozapine-treated inpatients with schizophrenia placed on a six-month diet and physical activity program. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(4):544–550. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang N-Y, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, Young DR, Frick KD, Yu A, Gennusa JV., III A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg RW, Reeves G, Tapscott S, Medoff D, Dickerson F, Goldberg AP, Ryan AS, Fang LJ, Dixon LB. “MOVE!”: Outcomes of a Weight Loss Program Modified for Veterans With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):737-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.National Institutes of Health (US). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report National Institutes of Health (US); 1998. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/ob_gdlns.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2014. [PubMed]

- 18.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmer PJ, Grimm R, Jr, Laing B, Grandits G, Svendsen K, Van Heel N, Betz E, Raines J, Link M, Stamler J, et al. Lifestyle intervention: results of the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS) Prev Med. 1995;24(4):378–388. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler J. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure: The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase II. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:657–667. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440430148027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliahou HE, Iaina A, Gaon T, Shochat J, Modan M. Body weight reduction necessary to attain normotension in the overweight hypertensive patient. Int J Obes. 1981;5(suppl 1):157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanik S, Marcus R. Insulin secretion improves following dietary control of plasma glucose in severely hyperglycemic obese patients. Metabolism. 1980;29(4):346–350. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lean ME, Powrie JK, Anderson AS, Garthwaite PH. Obesity, weight loss and prognosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 1990;7(3):228–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonne-Holm S, Sorensen T, Jensen G, Schnohr P. Independent effects of weight change and attained body weight on prevalence of arterial hypertension in obese and non-obese men. BMJ. 1989;299:767–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6702.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niv N, Cohen AN, Hamilton A, Reist C, Young AS. Effectiveness of a Psychosocial Weight Management Program for Individuals with Schizophrenia. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;41(3):370–380. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9273-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotondi AJ, Eack SM, Hanusa BH, Spring MB, Haas GL. Critical design elements of e-health applications for users with severe mental illness: singular focus, simple architecture, prominent contents, explicit navigation, and inclusive hyperlinks. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):440–448. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinman M, Young AS, Schell T, Hassell J, Mintz J. Computer-assisted self-assessment in persons with severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1343–1351. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinman M, Hassell J, Magnabosco J, Nowlin-Finch N, Marusak S, Young AS. The feasibility of computerized patient self-assessment at mental health clinics. Admin Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(4):401–409. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen AN, Golden JF, Young AS. Peer Wellness Coaches for Adults with Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(1):129–130. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.650101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Swift A, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(4):429–441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) Can J Sport Sci. 1992;17(4):338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International journal of qualitative methods. 2002;1(2):13–22. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

- 35.Ward MC, White DT, Druss BG. A meta-review of lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk factors in the general medical population: lessons for individuals with serious mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):477–486. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]