Abstract

The mechanisms by which metazoan origins of DNA replication are defined, regulated, and influenced by chromosomal events remain poorly understood. To gain insights into these mechanisms, we developed a systematic approach using a Drosophila high-resolution genomic microarray to determine replication timing, identify replication origins, and map protein-binding sites along a chromosome arm. We identify a defined temporal pattern of replication that correlates with the density of active transcription. These data indicate that the influence of transcription status on replication timing is exerted over large domains (>100 kb) rather than at the level of individual genes. We identify 62 early activating replication origins across the chromosome by mapping sites of nucleotide incorporation during hydroxyurea arrest. Using genome-wide location analysis, we demonstrate that the origin recognition complex (ORC) is localized to specific chromosomal sites, many of which coincide with early activating origins. The molecular attributes of ORC-binding sites include increased AT-content and association with a subset of RNA Pol II-binding sites. Based on these findings, we suggest that the distribution of transcription along the chromosome acts locally to influence origin selection and globally to regulate origin activation.

Keywords: Origin recognition complex (ORC), origin of DNA replication, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), RNA polymerase II, transcriptone, chromosome organization

Replication initiates at many sites along eukaryotic chromosomes that are marked in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by a multiprotein assembly called the pre-replicative complex (pre-RC) (Bell and Dutta 2002; Mendez and Stillman 2003). As eukaryotic cells enter S phase, a subset of these assemblies are directed to initiate replication in a defined temporal order (Fangman and Brewer 1992). Although the large majority of replication initiation factors are conserved in all eukaryotes, how metazoan origins of replication are defined, regulated, and influenced by other chromosomal events remains unclear.

The nature of replication origins and the sequences that define them are poorly understood in metazoan organisms (Gilbert 2004). Studies of human origins of replication at the lamin B2 and β-globin loci (Aladjem et al. 1995; Abdurashidova et al. 2000) and the Drosophila amplification locus on the third chromosome (Delidakis and Kafatos 1989; Heck and Spradling 1990; Lu et al. 2001) have identified relatively defined sites of replication initiation. In contrast, studies of the Chinese hamster DHFR (Vaughn et al. 1990) and human rDNA loci (Little et al. 1993; Yoon et al. 1995) are consistent with initiation occurring over broad regions (5-50 kb), although there are sites of preferred initiation within these regions (Kobayashi et al. 1998).

The binding of the origin recognition complex (ORC) to origin-proximal DNA is a critical early event in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication (Bell 2002). Once bound to DNA, ORC directs the formation of the pre-RC by coordinating the assembly of other replication factors onto the origin DNA (Mendez and Stillman 2003). In vitro studies of ORC from metazoan organisms suggest that these proteins have only limited DNA sequence specificity (Vashee et al. 2003; Remus et al. 2004). This has led to the suggestion that other DNA-binding proteins or aspects of chromosome structure (e.g., local chromatin modification) are required to direct ORC to sites of replication initiation.

It has long been recognized that in metazoan cells, euchromatic regions of chromatin replicate before heterochromatic regions (Stambrook and Flickinger 1970; Goldman et al. 1984; Taljanidisz et al. 1989; Gilbert 2002). More recently, studies using limited cDNA-based microarrays have demonstrated that there is a correlation between the time of replication and the transcription of nearby DNA within the euchromatin (Schübeler et al. 2002; Woodfine et al. 2004). Consistent with a connection between the transcriptional machinery and replication initiation, the normally nonspecific initiation observed in Xenopus egg extracts can be localized by the assembly of a transcription domain (Danis et al. 2004). In addition, transcription from the DHFR promoter in CHO cells acts to regulate and define the boundaries of initiation zones (Saha et al. 2004). Finally, in Drosophila, several transcriptional regulators, including E2F-, Rb-, and Myb-related proteins have been implicated in the regulation of the chorion locus amplification during oogenesis (Bosco et al. 2001; Beall et al. 2002). Despite these findings, the step(s) in the replication initiation process that are influenced by transcription remain poorly understood. Changes in transcriptional status could influence the initial selection of potential origins of replication during G1 (e.g., pre-RC formation) or the activation of pre-RCs during S phase. Similarly, it is unclear whether the effect of transcription is exerted locally or over large chromosomal domains.

Identification and characterization of metazoan replication origins has been hindered by the complexity of these genomes and the lack of robust assays to comprehensively monitor DNA replication. To address how metazoan sites of replication initiation are selected and regulated, we have developed a systematic approach to study the replication and transcription of a metazoan chromosome arm at high resolution. We found that the density of active transcription (as measured by RNA Pol II binding along the chromosome) correlates with replication timing, and that this correlation is not at the level of individual loci, but rather over extended chromosomal domains. By combining the identification of ORC-binding sites with the mapping of the earliest replicating sequences, we identified >50 new origins of replication, greatly increasing the number of known metazoan origins. Finally, we show that ORC-associated sequences overlap with a subset of RNA Pol II-binding sites, suggesting that transcription acts locally to define sites of pre-RC assembly and globally to regulate the temporal pattern of origin activation.

Results

To address the mechanisms of metazoan origin selection and regulation, we initiated a comprehensive survey of replication dynamics along a Drosophila chromosome. To characterize replication timing, identify origins, and map protein-binding sites along a Drosophila chromosome, we have designed a high-density genomic microarray that covers the left arm of Drosophila chromosome 2 (representing 20% of Drosophila euchromatic sequence) with 11,243 nearly contiguous 1.5-kb PCR products. Because almost 90% of the nonrepetitive euchromatic sequence from chromosome 2L is represented on this array, we were able to investigate replication timing at both inter- and intragenic sequences (∼40% of the fragments on the genomic microarray represent intergenic sequence). In contrast, prior studies using cDNA-based microarrays lacked data from intergenic regions and had only limited resolution (∼25 kb/cDNA) (Schübeler et al. 2002; Woodfine et al. 2004). In addition, the high density of the array allowed us to localize chromatin-associated proteins, including ORC and RNA Pol II, at 1.5-kb resolution.

The temporal pattern of replication is defined by the transcriptional activity of broad chromosomal domains

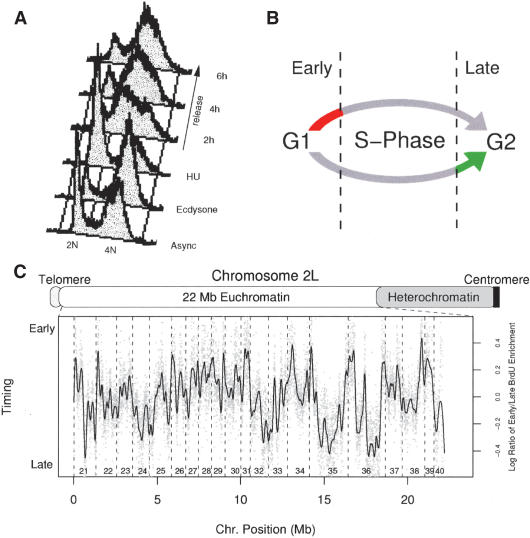

Replication timing data for chromosome 2L was generated by pulse labeling either early or late-replicating sequences from synchronized Kc cells with the nucleotide analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Kc cells were synchronized by treating the cells with the molting hormone ecdysone, resulting in a G2 arrest. The cells were released from the ecdysone block into medium containing hydroxyurea (HU), which resulted in an accumulation of cells at the G1/S transition. Following release from HU, the cells proceeded synchronously through S phase over the next 7 h (Fig. 1A). Early replicating sequences were labeled with a 1-h pulse of BrdU at the beginning of S phase, and late-replicating sequences were labeled with a 1-h pulse near the end of S phase (Fig. 1B). The resulting late or early replicating BrdU containing DNAs were enriched by immunoprecipitation and differentially labeled using either Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated dUTP and hybridized to the genomic microarray.

Figure 1.

Replication timing profile for chromosome 2L. (A) FACS profile of Drosophila Kc cell synchronization. Asynchronous log-phase Kc cells were treated with the molting hormone Ecdysone to arrest the cells at G2. Following 18-20 h, the cells were washed and resuspended in fresh medium containing HU. The cells accumulated at the G1/S transition within 12 h. Following release from HU, the cells proceeded through S phase. (B) Early and late-replicating sequences were specifically labeled using BrdU. Early or late-replicating sequences were labeled with a 1-h pulse at the beginning or end of S phase, respectively. The BrdU containing DNAs were enriched by immunoprecipitation and differentially labeled with Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated dUTP. (C) Replication timing was determined for each of the 11,243 unique euchromatic sites on chromosome 2L (gray dots) as the ratio of early to late BrdU incorporating sequences. The replication timing profile (black line) was generated by applying a smoothing algorithm to the raw timing data. The numbered cytological intervals of the chromosome are indicated at the bottom.

Analysis of the relative replication time of each of the sequences on the array from four independent experiments revealed clear early and late-replicating domains in the raw data (Fig. 1C, gray dots). For replication timing, we expect that adjacent chromosomal regions will have similar replication times. We tested this premise using the autocorrelation function, which calculates the correlation between each data point and its chromosomal neighbors. We observed a strong and significant correlation for up to 100 neighboring data points (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, no correlation was observed for the same data ordered by position on the microarray.

A replication timing profile was created by applying a smoothing algorithm to the data (Fig. 1C, solid line). The peaks and troughs of the curve represent the earliest and latest replicating chromosomal domains, respectively. We found that the size of these timing domains ranged from 18 to 790 kb with a mean of 257 kb. The replication timing profile generated for chromosome 2L was in close agreement with a previous study of replication timing in Drosophila Kc cells using cDNA-based microarrays and a different method of cell synchronization (Schübeler et al. 2002; Supplementary Fig. S2). The earliest replicating domains along the chromosome most likely contain efficient early activating replication origins, whereas the latest replicating domains contain sequences that are replicated in late S phase. However, it is impossible to distinguish whether those sequences that appear to be replicating in mid-S phase are the result of origin activation during mid-S phase, or the result of inefficient origin activation throughout S phase.

The high resolution of the genomic microarray allowed us to investigate how these early and late-replicating domains were connected to the molecular architecture of the chromosome. Specifically, we examined how replication timing correlates with gene density, gene expression, and active transcription. Although prior human (Woodfine et al. 2004) and Drosophila (Schübeler et al. 2002) replication timing studies using incomplete arrays of cDNAs have demonstrated a correlation between time of replication and the probability that a specific gene is expressed, it remained to be determined what step(s) in the replication initiation process are influenced by transcription. Similarly, because the prior studies lacked contiguous intergenic sequences, it was unclear whether the effect of transcription is exerted locally (at the level of individual genes) or over large chromosomal domains.

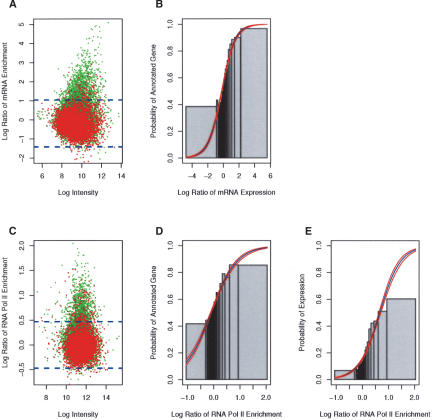

To quantify transcription along the chromosome, we hybridized labeled poly(A)-containing mRNA from asynchronous cells to the genomic microarray, using total genomic DNA as a control. The resulting pattern of expression along the chromosome was in close agreement with the predictions of inter- and intragenic sequences from the Drosophila annotation project. In Figure 2A, we colored each of the individual array DNA fragments green if the fragment had any overlap with an annotated gene. Sequences that did not overlap with annotated genes were colored red. We see enrichment of poly(A)-containing mRNA almost exclusively at fragments that overlap with annotated genes (green). It is important to note that we do not see mRNA enrichment at all of the sequences that overlap with annotated sequences. These nonenriched sites are almost certainly due to the fact that not all annotated genes are being actively transcribed, or that some transcripts contain large introns that overlap with the array fragment.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the transcriptome in Kc cells. (A) mRNA expression along the array matches the chromosome annotation (Celniker and Rubin 2003). A scatter plot of the mean log ratio of mRNA expression versus the average log intensity of each site on the array. The red and green spots indicate intergenic and intragenic sites on the array, respectively. A site was scored intragenic if it had any overlap with an annotated gene. The dashed blue line represents the confidence level (p < 0.01) of the enrichment. Note, that the majority (>85%) of enriched sites overlap with the annotated genes. (B) Probability of an annotated transcript increases with mRNA expression levels. Logistic regression was used to model the probability of a site being annotated as a gene as a function of mRNA expression. The blue and red lines represent the modeled probability and confidence levels, respectively. The Likelihood Ratio (L.R. = 1511) is a “goodness of fit” test statistic comparing the fit of the modeled data to the fit of the null model. The L.R. has a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom. The fitted model is significantly (p < 10-16) different from the null hypothesis. For comparison, the raw data was ordered by mRNA expression and sorted into bins of 200 (gray bars). The height of the gray bars is the fraction of annotated genes in each of the bins. The width of the bar represents the range of mRNA expression for each bin. (C) RNA Pol II enrichment matches the chromosome annotation. See above for details. (D) Same as B, except using RNA Pol II (L.R. = 798, p < 10-16). (E) Logistic regression modeling the probability a site is expressed (determined from mRNA enrichment) as a function of RNA Pol II enrichment (L.R. = 1288, p < 10-16).

Logistic regression was used to model the probability of a site being annotated as a gene as a function of mRNA expression (Fig. 2B). Logistic regression is a statistical technique used to model the probability of a binary outcome (whether or not an array fragment overlaps with an annotated gene) as a function of a continuous predictor variable (e.g., the level of mRNA expression). We found that the modeled probability of a site being annotated as a gene increased markedly with detectable mRNA expression levels. The blue and red lines represent the modeled probability and 95% confidence levels, respectively. For comparison, each sequence on the array was ordered by mRNA expression levels and sorted into bins of 200 (gray bars). The height of the bars is the fraction of annotated genes present in each of the bins. The width of each bar is defined by the range of mRNA expression for those 200 sequences.

Because steady-state mRNA levels may not accurately reflect the rate of active transcription, we also used genome-wide location analysis (Ren et al. 2000) to identify ∼1000 RNA Pol II-binding sites along the chromosome arm that were significantly enriched over the total population (p < 0.01). Briefly, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with antibodies directed against the CTD domain of RNA Pol II was used to enrich for RNA Pol II-associated sequences. These enriched sequences, as well as nonenriched control DNA, were differentially labeled with fluorescent nucleotides and hybridized to the microarray. Thus, the ratio of immunoprecipitated DNA to control DNA is indicative of relative enrichment along the chromosome. It is important to note that the log2 enrichment ratios detected for fragments on the array are dampened by the normalization process, array fragment size, and complexity of the genome, and do not directly translate into the actual fold enrichment for any given target (see below). Thus, the significance of the enrichment over the total population, in this case (p < 0.01) or >2.3 standard deviations, is used as a selection criteria.

RNA Pol II localizes to sites of active transcription. We found that RNA Pol II is primarily associated (80%) with intragenic sequences, consistent with it marking sites of transcription (Fig. 2C). Logistic regression was used to model the probability that a site on the array is annotated as a gene as a function of RNA Pol II enrichment (Fig. 2D). As with the mRNA analysis, we find that sites that are strongly enriched for RNA Pol II have a high probability of coinciding with an annotated gene. Finally, we show that RNA Pol II is specifically associated with expressed sequences as detected by mRNA hybridization (Fig. 2E). These findings strongly support the accuracy of our RNA Pol II localization studies.

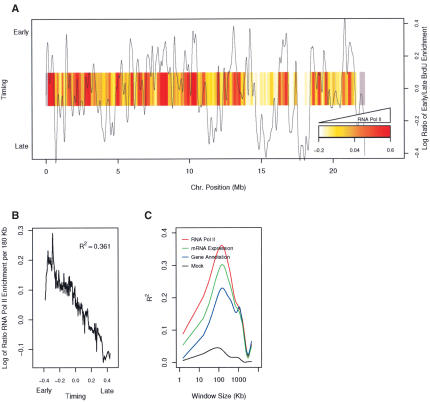

Using this chromosome-wide profile of the transcriptome, we assessed the correlation between replication timing and active transcription. The moving average (n = 100) of RNA Pol II enrichment along the chromosome was plotted as a heat map, with red representing a high density of RNA Pol II, and white representing regions of low RNA Pol II density (Fig. 3A). Comparison of RNA Pol II enrichment along the chromosome to the time of replication for the same sites revealed that early and late-replicating sequences are sharply defined by the transcriptional profile of the chromosome. For example, at 16 Mb, we observe an actively transcribed early replicating domain flanked by later-replicating transcriptionally inactive domains. Although almost every late-replicating domain is marked by low transcriptional activity, we do see some early replicating domains with low transcriptional activity (see the early replicating domain at 14 Mb). However, even in this case, the adjacent later replicating sequences have relatively lower RNA Pol II density. This suggests that the transition from early to late-replicating sequences is defined by changes in the local density of transcription rather than absolute levels.

Figure 3.

Replication timing correlates with the transcription profile of the chromosome. (A) RNA Pol II density delineates early and late-replicating domains. Spatial plot of the moving average (n = 100) of RNA Pol II enrichment along the chromosome, represented as a heat map (red, most dense; white, least dense). The gray regions on either end of the chromosome represent regions with insufficient data for the moving average. The smoothed timing data was plotted as black curve. (B) Actively transcribed regions replicate early. The moving average (n = 100) of RNA Pol II enrichment using windows of 180 Kb plotted as a function of replication timing. An R2-value of 0.361 was calculated for the correlation (without using a moving average). (C) Transcription over large domains influences replication timing. An R2-value was calculated for the correlation between replication timing and the density of either RNA Pol II (red), gene expression (green), annotated genes (blue), or a mock immunoprecipitation (black) using windows of increasing sequence.

The earliest replicating sequences on the chromosome have a higher density of RNA Pol II than the latest replicating sequences (Fig. 3B). A clear correlation between replication timing and RNA Pol II density (R2 = 0.361) was observed. Indeed, the earliest replicating decile of sequences are 10 times more likely to have sites of active transcription (RNA Pol II binding) than the latest replicating decile of sequences. Correlations were also observed for mRNA expression density (R2 = 0.299) and gene density (R2 = 0.228). In contrast, experiments with mock immunoprecipitated material showed no significant correlation (R2 = 0.034).

The high density and nearly contiguous nature of this microarray data allowed us to investigate the size of the transcriptional domains that influenced replication timing. We calculated the correlation coefficient for replication timing and the density of RNA Pol II-binding sites using increasing window sizes of sequence. If individual genes were strongly influencing the local time of replication, then we would expect a strong correlation even with relatively small windows (<15 kb). Instead, the correlation between replication timing and RNA Pol II density shows a dramatic increase with window size, peaking at ∼180 kb (Fig. 3C). Similar results were observed for gene expression and gene density. From these data, we conclude that early replicating domains are defined by the integration of transcriptional status over large domains that include many genes, rather than at the level of individual genes.

Identification of 62 early HU-resistant replication origins

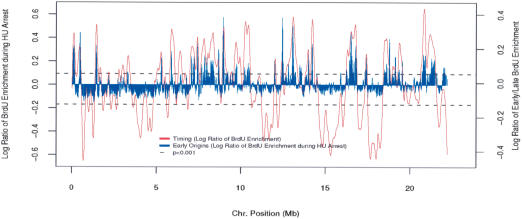

The almost complete coverage of the chromosome arm by the microarray provided an opportunity to determine whether specific sites functioned as origins of replication. To precisely localize replication origins, we exploited the effects of the replication inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU). If HU is present as cells enter S phase, then replication forks derived from early origins arrest after replicating only origin-proximal sequences. Studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe indicate that the resulting fork arrest also prevents late-origin firing through activation of the intra-S-phase checkpoint (Santocanale and Diffley 1998; Shirahige et al. 1998; Kim and Huberman 2001). Thus, if cells enter S phase in the presence of HU, only sequences adjacent to early origins are expected to incorporate nucleotides. Although related checkpoint pathways exist in Drosophila (Garner et al. 2001), their effect on late-origin firing has not been determined. Studies in S. cerevisiae have used HU treatment to successfully map early origins of replication (Yabuki et al. 2002; Katou et al. 2003), and we have taken a similar approach to map these sites in Drosophila Kc cells.

To identify early origins of replication, we released G2-synchronized cells into medium containing HU and BrdU. Only sequences immediately adjacent to early origins are expected to incorporate BrdU. The BrdU enrichment for each site on the array was plotted as a histogram against chromosomal position and overlaid with the replication timing data (Fig. 4). The dashed black line represents the upper and lower boundaries for sites being statistically enriched (p < 0.001). Each of the early replicating domains from the timing data contained at least one peak of BrdU incorporation in the presence of HU. Importantly, almost no BrdU incorporation was detected in the late-replicating domains, consistent with the identified regions acting as early origins of replication and supporting the existence of a Drosophila intra-S-phase checkpoint that inhibits late-origin firing. A noticeable exception to this is at the extreme right end of the euchromatic chromosome, where we see BrdU incorporation in a late-replicating domain. This region of the chromosome is very gene poor and dense in repetitive sequences and likely represents the transition of euchromatin into heterochromatin. Although repetitive sequences and regions of very low complexity were omitted from the microarray, we cannot determine whether this is bona fide early replication, or an artifact due to neighboring repetitive sequences.

Figure 4.

Identification and mapping of HU-resistant early replication origins. Early origins were identified by releasing cells synchronized at G2 into medium containing HU and BrdU. Only those sequences immediately adjacent to replication origins are expected to incorporate BrdU. The blue histogram represents BrdU enrichment along the chromosome. The replication timing profile is overlaid in red. Early BrdU-enriched peaks above the dashed black line (p < 0.001) are significantly enriched.

On the basis of these sites of HU-resistant BrdU incorporation, we identified 62 early replicating origins (Supplementary Table 1). In each case, we defined an early origin as a region having more than six contiguous sites of BrdU incorporation that were significantly enriched (p < 0.001) over the population. We have used quantitative real-time PCR to directly address the enrichment of BrdU incorporation at a small subset of sequences on the array (Supplementary Fig. S3) and see strong enrichment (five- to 20-fold) at sites identified as origins, and little or no enrichment at the multiple non-origin sequences tested. It is important to note that, due to the chromosomal scale of Figure 4, not all 62 of the early origins are clearly resolved (see Supplementary Table 1). Although the mean size of the region of BrdU incorporation for these origins is 32 kb, in each case there is a clear peak of incorporation that is most likely the site of initiation. Taken together with the pattern of replication timing, these results indicate that replication initiation occurs at distinct sites in the Drosophila genome.

To determine whether the sites that we identified included the only two previously identified Drosophila origins of replication, the microarray included sequences surrounding the DNA Pol α locus origin (oriDα) on chromosome 3R and the chorion locus origin (oriβ) on chromosome 3L. Previous studies indicate that the oriDα origin is early replicating and initiates in the presence of HU (Ina et al. 2001). Oriβ was identified due to its involvement in the specific amplification of the chorion locus in follicle cells during oogenesis; however, its use in other tissues is unknown (Spradling and Orr-Weaver 1987; Heck and Spradling 1990; Calvi and Spradling 1999). We detected a zone of HU-resistant BrdU incorporation immediately upstream of the DNA Pol α locus at oriDα (Fig. 5A). The apex of BrdU incorporation coincided with a region previously identified as containing replication intermediates by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and nascent strand analysis (Shinomiya and Ina 1994). In contrast, no BrdU incorporation was detected at oriβ (Fig. 5B), suggesting that this origin is not used or fires late in Kc cells. We did, however, detect multiple peaks of early BrdU incorporation 50 kb upstream of the chorion locus.

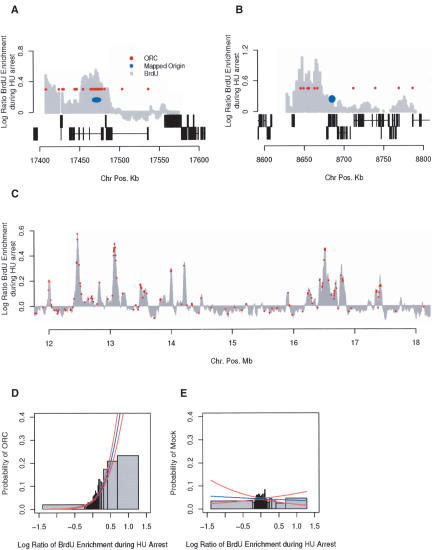

Figure 5.

Identification of ORC-binding sites. (A) Replication of the DNA Pol α locus on chromosome 3R. The gray histogram represents sites of BrdU incorporation during HU arrest (early activating origins), the red circles represent ORC-binding sites, and the blue oval represents a zone of replication initiation previously mapped by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Shinomiya and Ina 1994). The gene structure for both the Watson and Crick strands for 130 kb surrounding the DNA Pol α locus is depicted below the histogram. Exons are indicated as black boxes connected by a horizontal black line. (B) Replication of the chorion locus on chromosome 3L. (C) A total of 491 ORC-binding sites were identified on chromosome 2L by genome-wide location analysis. A subset of ORC-binding sites are shown in red overlaid on a portion (6 Mb) of the early activating origins (gray histogram). The ORC-binding sites represent <5% of the analyzed data points. (D) The probability of finding ORC associated with the DNA increases with BrdU enrichment at early origins. Logistic regression was used to model the probability of a sequence being associated with ORC as a function of BrdU enrichment during HU-arrest (L.R. = 265, p < 10-16). (E) Same as D, but using 491 sites from a mock immunoprecipitation (L.R. = 0.08, p < 0.777).

Identification of 491 ORC-associated sequences by genome-wide location analysis

Studies in a number of eukaryotic organisms indicate that ORC is localized to origins of replication and directs the formation of the pre-RC, a critical intermediate in the initiation process (Bell and Dutta 2002). A previous study in S. cerevisiae indicated that ORC localization could be used to identify potential origins of replication (Wyrick et al. 2001). Thus, we sought to identify ORC-binding sites along the Drosophila chromosome to further refine our mapping of early replication origins as well as to identify potential late-activating or inefficient replication origins.

Using genome-wide location analysis of ORC, we identified 491 ORC-binding sites (p < 0.01) along the chromosome arm (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, 20% of the ORC-binding sites were clustered (immediately adjacent to another ORC-binding site), in some cases spreading over >5 kb. The median distance between nonclustered ORC-binding sites was 25 kb, which likely represents a minimum replicon size and is consistent with earlier estimates of replicon size (Blumenthal et al. 1974). A similar clustering of ORC-binding sites was observed at ectopic sites of amplification under control of the ACE3 element required for chorion amplification (Austin et al. 1999). This distribution of ORC along the chromosome is distinctly different from that of S. cerevisiae, where clustering of ORC is only observed at the telomeres (Wyrick et al. 2001).

Consistent with ORC's role as an essential replication initiator, ORC-binding sites were associated with early replicating origins. We observed that the probability of ORC associating with a sequence on the array increases with BrdU enrichment at early origins during HU arrest (Fig. 5D). In contrast, at sites that are not enriched for BrdU, the probability of finding ORC is similar to its global distribution (4%). Note that we do not expect to find ORC at all BrdU-enriched sites, as the zone of BrdU incorporation at early HU-resistant origins of replication is likely larger than the potential sites of initiation marked by ORC. In contrast, if we randomly select 491 sites along the chromosome, we see no statistical association with early replication origins (Fig. 5E). ORC-binding sites were found within 73% (45) of the regions of HU-resistant BrdU incorporation (Supplementary Table 1). When ORC was localized within these regions, it was most frequently (78% of the time) at or near (<5.25 kb) the apex of BrdU incorporation. These results are comparable to prior results in S. cerevisiae, where pro-ARSes (sequences associated with the MCM complex and/or ORC) (Wyrick et al. 2001) coincide with 90 of 122 (76%) early HU-resistant origins (Yabuki et al. 2002).

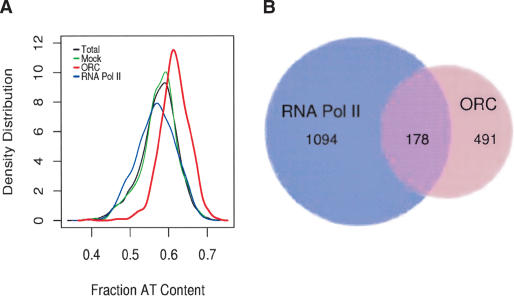

AT-content, intergenic sequence, and RNA Pol II are molecular determinants of ORC binding

The identification of ORC-binding sites along the chromosome provided an opportunity to identify the in vivo determinants for ORC binding. ORC was observed at only 28 sites that were predicted to contain >70% exonic sequences in contrast to the 81 sites expected by chance (p < 10-9). The AT-content of the ORC-bound fragments was also significantly skewed. The mean AT-content of the sequences associated with ORC was 62% compared with 57% for all the sequences on the array (p < 10-16, Fig. 6A). We saw no increase in AT-content when we sampled the sequences identified in other genome-wide location experiments (including RNA Pol II, Fig. 6A). These data suggest that ORC binds preferentially to AT-rich, intergenic, and intronic sequences.

Figure 6.

Molecular predictors of ORC localization. (A) ORC preferentially binds AT-rich regions of the genome. The density distribution of AT-content is shown for ORC-binding sites. The mean AT-ratio of ORC-associated array sequences was 62% compared with 57% for the all of the fragments on the array (t = 24.23, p < 10-16). The frequency distribution of AT-content for a mock ChIP (green), and RNA Pol II (blue) were statistically indistinguishable from that of the entire array (black). (B) ORC-binding sites colocalize with a subset of RNA Pol II sites. A Venn diagram depicting the overlap of RNA Pol II and ORC-binding sites along the chromosome. The degree of overlap was highly significant (χ2 = 357 and p < 10-16).

Given the relationship between transcription and replication timing (Fig. 3), we also investigated whether there was any overlap between ORC and RNA Pol II-binding sites. Interestingly, 178 of the 491 ORC-binding sites (36%) overlap with RNA Pol II-binding sites (Fig. 6B), a proportion significantly (p < 10-16) greater than the 43 sites expected by chance. As described above, the vast majority of RNA Pol II sites are coincident with potentially transcribed sequences. In contrast, the ORC-binding sites, including the 178 sites that colocalize with RNA Pol II, show no preference for transcribed regions. One possible explanation for these findings is that ORC and RNA Pol II are colocalized at transcriptional promoter regions. Indeed, we find that 92 of the 178 sites that interact with both ORC and RNA Pol II overlap with transcription start sites of annotated genes, significantly greater (p < 10-13) than the 48 expected by chance.

Discussion

We have used a Drosophila genomic microarray to identify 45 ORC-associated early origins of replication. We have also examined how the transciptome influences replication timing. We found that early replicating sequences are defined by large actively transcribed chromosomal domains and that the transcriptional status of individual genes has little effect on replication timing. Finally, we show that ORC is localized to specific sites and many of these sites overlap with RNA Pol II-associated sequences, suggesting that origin selection is influenced by transcription.

Our replication timing data revealed clear early and late-replicating domains. These domains were often sharply defined by the density of transcription along the chromosome. The density of RNA Pol II along the chromosome was an order of magnitude greater at the earliest replicating sequences as compared with late-replicating regions. These differences suggest that the molecular architecture of the chromosome may define both the transcription and replication profiles of the chromosome. These transcriptionally active and early replicating domains may be physically marked by a change in chromatin structure that allows for increased access to both replication and transcription factors. It is possible that these domains are defined or restricted by elements of higher order chromosome structure, such as matrix attachment regions, transcriptional insulators, or chromatin loops. However, the state of the chromatin, whether euchromatic or heterochromatic, cannot be the sole determinant for origin activation, as there are examples of efficient heterochromatic origins in S. pombe (Kim et al. 2003). Interestingly, the gene-sparse, late-replicating regions we identified in Kc cells overlap with late and under-replicated regions found in polytene salivary chromosomes (Zhimulev et al. 2003, Supplementary Fig. S4). Taken together, these data suggest that the temporal program of replication is defined by chromatin structure and conserved in different Drosophila cell types.

We have used HU to arrest cells early in S phase and to restrict BrdU incorporation to sites overlapping and immediately adjacent to early origins of replication. Using this approach, we have identified 62 sites along the chromosome arm that are used as early replication origins. A recent study observed a change in the local pattern of origin usage at the adenylate deaminase2 locus in response to HU treatment (Anglana et al. 2003). Although our use of HU could have affected the set of origins we identified, we think that this is unlikely. First, the pattern of early and late-replicating regions we observed using an HU-based protocol is similar to the pattern seen by others using approaches that did not involve replication inhibitors (Schübeler et al. 2002, Supplementary Fig. S2). Secondly, our studies used arresting concentrations of HU, unlike the hamster cell studies, in which lower concentrations of HU that slowed but did not completely arrest replication were used. Given that we find only a limited number of sites of BrdU incorporation under these arresting conditions, it is likely that only the earliest replicating origins are able to initiate before the intra-S-phase checkpoint prevents other origins from initiating. Finally, even if these origins represent only a subset of the origins along the chromosome, they are a valuable new resource, given the paucity of metazoan origins available prior to these studies.

Our findings provide clear evidence that ORC is localized to specific chromosomal regions. Consistent with the role of ORC as an essential initiator, we find this complex is localized to the majority of early replicating origins, most often at or near the apex of BrdU incorporation. Although we do not detect ORC at 27% of the early origins, we do not believe that these represent sites of ORC independent initiation, but rather a limitation of the ChIP technology. We have by no means exhaustively identified all of the ORC-binding sites along the chromosome, as many ORC sites are likely to be occluded from antibody access by additional chromatin-binding complexes. In addition, many ORC-binding sites are likely present in the repetitive and low-complexity sequences (Pak et al. 1997) that are necessarily omitted from the array.

In contrast to S. cerevisiae, where ORC binds discretely to single sites along the chromosome, we see significant clustering of ORC along the chromosome. Almost 20% of the identified ORC-associated sequences were immediately adjacent to other ORC-associated sequences. This clustering of ORC along the chromosome was also observed at extra chromosomal copies of the ACE3 locus in amplifying follicle cells (Austin et al. 1999). Because the ORC-associated sequences often span >3 kb, we can rule out trivial factors such as shear size of the chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA. These clusters of ORC-associated sequence may represent unique chromatin environments favorable to ORC binding, or polymerization of ORC on the DNA following a nucleation event at a specific site.

The type of ORC association may influence the nature of replication initiation at a particular locus. We found that 36% of the early origins contain clusters of three or more ORC-binding sites. For example, at oriDα, ORC was continuously associated with a 10-kb region that overlapped a broad region of BrdU incorporation (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the analysis of replication intermediates by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in this region revealed multiple initiation sites over the entire region (Ina et al. 2001). In contrast, at the origin identified upstream of the chorion locus (see above), three separate peaks of BrdU incorporation were each marked by distinct ORC-binding sites (Fig. 5B). This form of ORC association with origins may be analogous to the human lamin B2 locus, where replication initiates at a discrete site (Abdurashidova et al. 2000). Thus, the origin at oriDα and the origin upstream of the chorion locus may represent two distinct types of origins, those defined by broad domains of ORC binding and those associated with more discrete ORC-binding sites.

Despite finding ORC at specific regions along the chromosome, the exact mechanism that leads to ORC localization remains to be determined. There are multiple molecular characteristics of the sites of ORC localization, including increased AT-content, noncoding DNA, and RNA Pol II association. These molecular predictors of ORC association could be directly involved in ORC DNA binding, could bind to one or more factors that facilitate ORC localization, or could be required for another origin-related function (e.g., DNA unwinding). It is important to note, however, that none of these attributes are individually sufficient to identify ORC-binding sites. For example, high AT-content by itself was insufficient to define an ORC-binding site, as many sequences on the array have AT-content >62%, but are not represented in the ORC-associated sequences. However, ORC was seemingly excluded from sequences with low AT-content (Fig. 6A), suggesting that increased AT-content is necessary, but not sufficient for ORC association. Indeed, we have been unable to identify a consensus sequence within the 491 ORC-bound DNA sequences. The lack of a consensus sequence is consistent with the observation that metazoan ORC has only limited sequence specificity in vitro (Vashee et al. 2003; Remus et al. 2004). We propose that the attributes we have identified cooperate to define sites of ORC localization. It is certain that there are additional determinants that we did not identify in our studies. For example, the topology of DNA can strongly influence Drosophila ORC binding (Remus et al. 2004). Nevertheless, the availability of numerous known Drosophila ORC-binding sites associated with origins of replication will greatly facilitate future studies of ORC localization and origin function.

Because only a small subset of origins are likely to initiate in the presence of HU, it is not surprising that only a subset of ORC-binding sites are associated with the early replicating regions. We anticipate that many of the remaining ORC-binding sites are associated with origins that fire later in S phase. The methods used in this study did not allow the confident identification of late or inefficient origins. However, studies in S. cerevisiae have shown that abrogation of the intra-S-phase checkpoint results in the activation of late-replication origins in the presence of HU (Santocanale and Diffley 1998; Shirahige et al. 1998), suggesting that a similar approach could be useful for identifying late-activating metazoan origins. In addition, it is possible that a subset of the ORC-binding sites that we identified are involved in other functions, such as gene regulation (Bell et al. 1993; Foss et al. 1993) or the establishment of heterochromatin (Pak et al. 1997).

We propose that the frequent colocalization of ORC and RNA Pol II reflects a connection between transcription and ORC localization. Although it is possible that there is a direct interaction between ORC and RNA Pol II, we have not observed such an interaction in coimmunoprecipitation assays (data not shown). In addition, the majority of the sites of RNA Pol II association do not interact with ORC. An alternative hypothesis is that ORC localization is, at least in part, facilitated by a subset of the transcription factors that serve to localize RNA Pol II. Indeed, previous studies have shown that both Drosophila E2F1 and Myb interact with ORC; however, ORC is still localized to the chorion locus during amplification in Myb mutants and mutants of E2F1 that do not interact with ORC (Bosco et al. 2001; Beall et al. 2002). One possible explanation for these findings is that Myb and E2F1 act redundantly to recruit ORC throughout the genome. We propose that ORC, like RNA Pol II, can be recruited by many different transcription factors, which would lead to the frequent colocalization with RNA Pol II, but not any particular transcription factor. These factors could recruit ORC by direct interaction or by establishing a chromatin domain that is conducive to ORC recruitment (Bell 2002).

Our findings support a connection between the molecular architecture of the chromosome and the replication process at two levels. First, the frequent colocalization of ORC and RNA Pol II leads to the hypothesis that nearby transcription factor-binding sites influence the earliest steps of origin selection by facilitating ORC localization and subsequently pre-RC formation. Second, the decision of when each origin initiates replication during S phase (which is mechanistically separate from ORC localization and the assembly of pre-RCs in G1 phase) is connected to transcriptional status in a more global manner. The more transcriptionally active the chromosomal region, the greater the likelihood that replication initiation will occur early in S phase within that domain. Our findings indicate that transcriptional status is integrated over broad regions (>100 kb) of the chromosome (rather than individual genes) to determine the time of replication of each chromosomal locus. Further exploration of the connection between higher order chromosome structure and DNA replication will provide insights into the coordination of the molecular events that must occur to propagate and maintain genomic information.

Materials and methods

Array design

The genomic array used in this study, dros_chrom_array_MIT_120803, was designed in our laboratory. The array contains 13,440 features spotted on glass Gaps II slides (Corning) in 32 meta grids. There are 11,243 1.5-kb amplified PCR products that tile the nonrepetitive sequences of chromosome 2L. In addition, there are 287 1.5-kb features from chromosome 4, 90 features from chromosome 3L, 177 features from chromosome 3R, and finally, 48 features corresponding to telomeric sequences. The features were all amplified from BACs and visually verified. The oligos for amplification were designed from the final release candidate for release 3.0 of the Drosophila genome using custom Perl scripts and Primer3. The primers were synthesized by Operon. A file with all of the coordinates of the array features is available at http://chromosome2L.mit.edu.

Cell synchronization and BrdU labeling

Kc cells were cultured in 15-cm plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in Schneider's Media (Invitrogen 11720034) supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were arrested in G2 by the addition of the hormone Ecdysone (Sigma H5142) at a final concentration of 1.7 μM. To arrest the cells at the G1/S transition, the cells were released from Ecdysone into 1 mM HU. For replication timing, cells were pulsed with 50 μg/mL BrdU (Roche 280 879) for 1 h at either 0 or 6 h following release from HU. For identification of early origins, cells were released from G2 into medium containing both BrdU and HU at the same concentrations as above. Cell cycle progression was monitored by FACS.

Enrichment of BrdU-labeled DNA

DNA was isolated as previously described (MacAlpine et al. 1997). The isolated DNA was sheared to an average size of 1 kb by sonication (Branson Sonifier 250). Approximately 10 μg of the labeled DNA was heat denatured and diluted in 500 μL of ChIP lysis buffer (Austin et al. 1999). BrdU-enriched sequences were immunoprecipitated using magnetic IgG Dynabeads (Dynal M-280 Sheep anti-mouse IgG 112.01) precoupled to anti-BrdU antibody (BD Pharmingen 555627). The samples were washed and eluted as described previously for ChIP samples (Austin et al. 1999). For the identification of HU-resistant early replication origins, DNA recovered after immunoprecipitation from cells that were not treated with BrdU served as a control.

Chromatin isolation

For each experiment, ∼5 × 108 Kc cells were collected from asynchronous cultures. The cells were washed twice in 1× PBS and resuspended in hypotonic buffer (20 mM K-HEPES at pH 7.8, 5 mM KOAc, 0.5 mM MgCl2) for 20 min to induce swelling. The cells were broken by dounce homogenization and the nuclei were collected by low-speed centrifugation. To decrease nonspecific signal, the nuclei were salt extracted for 15 min using hypotonic buffer + 0.5% NP40 and 100 mM NaCl. Following salt extraction, the nuclei were washed and resuspended in hyptonic buffer. The nuclei were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 5 min and quenched with 125 mM glycine. The cross-linked nuclei were pelleted, washed in 1× PBS and resuspended in 500 μL ChIP lysis buffer. The chromatin was sheared by sonication to an average size of 1 kb.

ChIP

The chromatin was immunoprecipitated with either anti-DmORC2 (Austin et al. 1999), pre-immune sera, or anti-RNA Pol II (Upstate 05-623) antibody as described in Austin et al. (1999).

mRNA expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from asynchronous Kc cells using Trizol (Invitrogen) and subsequently purified using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA (10 μg) was directly labeled with either Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated dUTP (Amersham PA55022, PA55302) using oligo d(T)18 primers and Stratascript reverse transcriptase (Stratagene, 600085). For the mRNA expression studies, labeled total DNA (see below) from asynchronous cell cultures was used as the opposite channel control.

Labeling of DNA with fluorescent nucleotides

The immunoprecipiated DNA was labeled with either fluorescent Cy5- or Cy3-conjugated dUTP (Amersham PA55022, PA55302) using Sequenase (US Biochemicals 70775Z) and a random nonamer oligo (IDT). The immunoprecipitated DNA (100-300 ng) was dried in a speed-vac and resuspended in 10 μL of Sequenase primer mix (1× Sequenase buffer, 5 μg of random nonamer, 5 mM dUTP-Cy★). The samples were heat denatured and cooled to 4°C in a thermocycler before adding 5 μL of Sequenase reaction mix (1× Sequenase buffer, 1.5 mM dATP, 1.5 mM dCTP, 1.5 mM dGCTP, 0.75 mM dTTP, 500 ng BSA, 3.5 mM DTT and 13 U Sequenase). The reaction temperature was slowly ramped to 37°C and incubated for 30 min. Following incubation, the sample was heat denatured, cooled to 4°C, and fresh Sequenase (4 U) was added for the second and final round of labeling. Following the labeling, unincorporated nucleotides, oligo, and dye were removed using Microcon filters (Millipore YM-30).

Array hybridization and washing

The slides were hybridized and washed as previously described (Wyrick et al. 2001).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7000 Detection System (Applied Biosystems). PCR reactions were performed using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with 1-5 ng of template per reaction and 500 nM primers. All primer pairs were designed by Primer3 and generated amplicons <100 bp. A detailed list of primer pairs and coordinates is available at: http://chromosome2L.mit.edu.

Data analysis

The slides were scanned using an Arrayworx Auto E scanner (Applied Precision) and initial Tiff images of each channel were acquired using the Arrayworx software. Image quantitation was performed with Spot v2.0 (CSIRO Mathematical and Information Sciences, Image Analysis Group). The nonlinear filter, morphological opening, in the Spot software package was used to assess slide backgroud. The slides were normalized using loess-based normalization in the M/A domain (Yang et al. 2001). Specifically, we used the sma package for R (v1.8.0), a computer language and environment for statistical computing. We also performed scale normalization across slides (experiments), so each experiment had the same median absolute deviation. The average log ratio of enrichment for each spot on the array was calculated for at least three independent experiments. Subsequent statistical measurements were performed using these average values in R. The replication timing data was smoothed using the loess function of R with a span value of 0.016. The early BrdU incorporation data was smoothed using the moving average of 10 adjacent sites. All p-values were calculated from the normal distribution. For mRNA expression, the mean and variance of spots on the array that did not overlap with annotated genes (5068 sites) were used to model the normal distribution. For BrdU enrichment at early HU-resistant origins of replication, we used the mean and variance of those sites that corresponded with late-replicating sequences (5480 sites) as identified in the replication timing profile to model the normal distribution. For RNA Pol II and ORC, we modeled the normal distribution on the mean and variance of the negatively enriched spots and their absolute values (>6000 sites). Logistic regression analysis was performed using the Design and effects packages for R.

R and related software packages are all available at http://www.r-project.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry Orr-Weaver, Julia Zeitlinger, Milan de Vries, Hannah Blitzblau, John Randell, and Cary Lai for critical reading. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. D.M.M. is a fellow of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Cancer Fund.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1246404.

References

- Abdurashidova G., Deganuto, M., Klima, R., Riva, S., Biamonti, G., Giacca, M., and Falaschi, A. 2000. Start sites of bidirectional DNA synthesis at the human lamin B2 origin. Science 287: 2023-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladjem M., Groudine, M., Brody, L., Dieken, E., Fournier, R., Wahl, G., and Epner, E. 1995. Participation of the human β-globin locus control region in initiation of DNA replication. Science 270: 815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglana M., Apiou, F., Bensimon, A., and Debatisse, M. 2003. Dynamics of DNA replication in mammalian somatic cells: Nucleotide pool modulates origin choice and interorigin spacing. Cell 114: 385-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin R., Orr-Weaver, T., and Bell, S. 1999. Drosophila ORC specifically binds to ACE3, an origin of DNA replication control element. Genes & Dev. 13: 2639-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall E., Manak, J., Zhou, S., Bell, M., Lipsick, J., and Botchan, M. 2002. Role for a Drosophila Myb-containing protein complex in site-specific DNA replication. Nature 420: 833-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. 2002. The origin recognition complex: From simple origins to complex functions. Genes & Dev. 16: 659-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. and Dutta, A. 2002. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71: 333-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S., Kobayashi, R., and Stillman, B. 1993. Yeast origin recognition complex functions in transcription silencing and DNA replication. Science 262: 1844-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal A., Kriegstein, H., and Hogness, D. 1974. The units of DNA replication in Drosophila melanogaster chromosomes. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 38: 205-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco G., Du, W., and Orr-Weaver, T. 2001. DNA replication control through interaction of E2F-RB and the origin recognition complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi B. and Spradling, A. 1999. Chorion gene amplification in Drosophila: A model for metazoan origins of DNA replication and S-phase control. Methods 18: 407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker S. and Rubin, G. 2003. The Drosophila melanogaster genome. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 4: 89-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis E., Brodolin, K., Menut, S., Maiorano, D., Girard-Reydet, C., and Mechali, M. 2004. Specification of a DNA replication origin by a transcription complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6: 721-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delidakis C. and Kafatos, F. 1989. Amplification enhancers and replication origins in the autosomal chorion gene cluster of Drosophila. EMBO J. 8: 891-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangman W. and Brewer, B. 1992. A question of time: Replication origins of eukaryotic chromosomes. Cell 71: 363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss M., McNally, F., Laurenson, P., and Rine, J. 1993. Origin recognition complex (ORC) in transcriptional silencing and DNA replication in S. cerevisiae. Science 262: 1838-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner M., van Kreeveld, S., and Su, T. 2001. mei-41 and bub1 block mitosis at two distinct steps in response to incomplete DNA replication in Drosophila embryos. Curr. Biol. 11: 1595-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. 2002. Replication timing and transcriptional control: Beyond cause and effect. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 14: 377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 2004. Timeline: In search of the holy replicator. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5: 848-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M., Holmquist, G., Gray, M., Caston, L., and Nag, A. 1984. Replication timing of genes and middle repetitive sequences. Science 224: 686-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck M. and Spradling, A. 1990. Multiple replication origins are used during Drosophila chorion gene amplification. J. Cell. Biol. 110: 903-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ina S., Sasaki, T., Yokota, Y., and Shinomiya, T. 2001. A broad replication origin of Drosophila melanogaster, oriDalpha, consists of AT-rich multiple discrete initiation sites. Chromosoma 109: 551-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou Y., Kanoh, Y., Bando, M., Noguchi, H., Tanaka, H., Ashikari, T., Sugimoto, K., and Shirahige, K. 2003. S-phase check-point proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature 424: 1078-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. and Huberman, J. 2001. Regulation of replication timing in fission yeast. EMBO J. 20: 6115-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Dubey, D., and Huberman, J. 2003. Early-replicating heterochromatin. Genes & Dev. 17: 330-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Rein, T., and DePamphilis, M. 1998. Identification of primary initiation sites for DNA replication in the hamster dihydrofolate reductase gene initiation zone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 3266-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R., Platt, T., and Schildkraut, C. 1993. Initiation and termination of DNA replication in human rRNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 6600-6613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Zhang, H., and Tower, J. 2001. Functionally distinct, sequence-specific replicator and origin elements are required for Drosophila chorion gene amplification. Genes & Dev. 15: 134-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine D., Zhang, Z., and Kapler, G. 1997. Type I elements mediate replication fork pausing at conserved upstream sites in the Tetrahymena thermophila ribosomal DNA minichromosome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 4517-4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J. and Stillman, B. 2003. Perpetuating the double helix: Molecular machines at eukaryotic DNA replication origins. Bioessays 25: 1158-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak D., Pflumm, M., Chesnokov, I., Huang, D., Kellum, R., Marr, J., Romanowski, P., and Botchan, M. 1997. Association of the origin recognition complex with heterochromatin and HP1 in higher eukaryotes. Cell 91: 311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus D., Beall, E., and Botchan, M. 2004. DNA topology, not DNA sequence, is a critical determinant for Drosophila ORC-DNA binding. EMBO J. 23: 897-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B., Robert, F., Wyrick, J., Aparicio, O., Jennings, E., Simon, I., Zeitlinger, J., Schreiber, J., Hannett, N., Kanin, E., et al. 2000. Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science 290: 2306-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Shan, Y., Mesner, L., and Hamlin, J. 2004. The promoter of the Chinese hamster ovary dihydrofolate reductase gene regulates the activity of the local origin and helps define its boundaries. Genes & Dev. 18: 397-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santocanale C. and Diffley, J. 1998. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature 395: 615-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schübeler D., Scalzo, D., Kooperberg, C., van Steensel, B., Delrow, J., and Groudine, M. 2002. Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophila melanogaster: A link between transcription and replication timing. Nat. Genet. 32: 438-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomiya T. and Ina, S. 1994. Mapping an initiation region of DNA replication at a single-copy chromosomal locus in Drosophila melanogaster cells by two-dimensional gel methods and PCR-mediated nascent-strand analysis: Multiple replication origins in a broad zone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 7394-7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahige K., Hori, Y., Shiraishi, K., Yamashita, M., Takahashi, K., Obuse, C., Tsurimoto, T., and Yoshikawa, H. 1998. Regulation of DNA-replication origins during cell-cycle progression. Nature 395: 618-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. and Orr-Weaver, T. 1987. Regulation of DNA replication during Drosophila development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 21: 373-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambrook P. and Flickinger, R. 1970. Changes in chromosomal DNA replication patterns in developing frog embryos. J. Exp. Zool. 174: 101-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taljanidisz J., Popowski, J., and Sarkar, N. 1989. Temporal order of gene replication in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9: 2881-2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashee S., Cvetic, C., Lu, W., Simancek, P., Kelly, T., and Walter, J. 2003. Sequence-independent DNA binding and replication initiation by the human origin recognition complex. Genes & Dev. 17: 1894-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn J., Dijkwel, P., and Hamlin, J. 1990. Replication initiates in a broad zone in the amplified CHO dihydrofolate reductase domain. Cell 61: 1075-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodfine K., Fiegler, H., Beare, D., Collins, J., McCann, O., Young, B., Debernardi, S., Mott, R., Dunham, I., and Carter, N. 2004. Replication timing of the human genome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13: 191-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrick J., Aparicio, J., Chen, T., Barnett, J., Jennings, E., Young, R., Bell, S., and Aparicio, O. 2001. Genome-wide distribution of ORC and MCM proteins in S. cerevisiae: High-resolution mapping of replication origins. Science 294: 2357-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuki N., Terashima, H., and Kitada, K. 2002. Mapping of early firing origins on a replication profile of budding yeast. Genes Cells 7: 781-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Dudoit, S., Lu, P., and Speed, T. 2001. Normalization for cDNA microarray data. In Microarrays: Optical technologies and informatics., (eds. M. Bittner et al.), 141-152. The International Society for Optical Engineering, Bellingham, WA.

- Yoon Y., Sanchez, J., Brun, C., and Huberman, J. 1995. Mapping of replication initiation sites in human ribosomal DNA by nascent-strand abundance analysis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 2482-2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhimulev I., Belyaeva, E., Makunin, I., Pirrotta, V., Volkova, E., Alekseyenko, A., Andreyeva, E., Makarevich, G., Boldyreva, L., Nanayev, R., et al. 2003. Influence of the SuUR gene on intercalary heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster polytene chromosomes. Chromosoma 111: 377-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]