Abstract

We investigated the feasibility of the clinical application of novice-practitioner-performed/offsite-mentor-guided ultrasonography for identifying the appendix. A randomized crossover study was conducted using a telesonography system that can transmit the ultrasound images displayed on the ultrasound monitor (ultrasound sequence video) and images showing the practitioner’s operations (background video) to a smartphone without any interruption in motion over a Long-Term Evolution (LTE) network. Thirty novice practitioners were randomly assigned to two groups. The subjects in group A (n = 15) performed ultrasonography for the identification of the appendix under mentoring by an onsite expert, whereas those in group B (n = 15) performed the same procedure under mentoring by an offsite expert. Each subject performed the procedure on three simulated patients. After a 4-week interval, they performed the procedure again under the other type of mentoring. A total of 90 ultrasound examinations were performed in each scenario. The primary outcomes were the success rate for identifying the appendix and the time required to identify the appendix. The success rates for identifying the appendix were 91.1 % (82/90) in onsite-mentored ultrasonography and 87.8 % (79/90) in offsite-mentored ultrasonography; both rates were high, and there was no significant difference (p = 0.468) between them. The time required in the case of offsite mentoring (median, 242.9 s; interquartile range (IQR), 238.2) was longer than that for onsite mentoring (median, 291.4 s; IQR, 200.9); however, the difference was not significant (p = 0.051). It appears that offsite mentoring can allow novice onsite practitioners to perform ultrasonography as effectively as they can under onsite mentoring, even for examinations that require proficiency in rather complex practices, such as identifying the appendix.

Keywords: Telesonography, Viewing of clinical imaging, Smartphone

Introduction

It has previously been demonstrated that it is feasible for a remote expert to perform tele-interpretation of lossy transmitted radiologic images [1–7]. Thus, computed tomography (CT)-based or X-ray-based teleradiology has already been widely adopted in various clinical settings. Although we have already reported that the remote interpretation for transmitted ultrasound videos using the telesonography system in evaluating cardiac dynamic function and diagnosing acute appendicitis was also feasible [8], ultrasonography-based teleradiology (telesonography) is more complex than other types of teleradiology. Unlike CT scans or X-rays, ultrasonography requires a sonographer who can acquire images of sufficiently high quality at the bedside. However, an experienced sonographer is not always available 24 h a day, even in tertiary hospitals in Korea, and the situation may be similar worldwide. Several previous studies have revealed that a novice onsite ultrasound user can acquire interpretative images with the guidance of a remote expert [9–11]. However, these studies have been confined to certain simple clinical settings, such as pneumothorax and intraperitoneal fluid collection in trauma patients. These examinations are usually simple, and the key finding can be easily identified in a broad, fixed location in the body; therefore, even a novice sonographer can complete such an examination with minimal guidance from a mentor. By contrast, we consider the identification of acute appendicitis to be highly complex and thus to require more specific and detailed guidance during telementored ultrasonography. We have previously reported the clinical application of real-time telesonography in diagnosing pediatric acute appendicitis in the emergency department (ED) and have verified that telesonography performed by a less experienced onsite sonographer under the guidance of a remote expert can be effectively used for diagnosis even in such complicated cases [12]. However, in that study, emergency medicine residents with some experience in ultrasonography (rather than novice examiners) acted as the onsite sonographers. Therefore, that study could not demonstrate the effectiveness of telesonography between a remote expert and a novice sonographer with no previous experience in diagnosing acute appendicitis.

We wished to investigate whether a novice sonographer can effectively perform ultrasonography under mentoring by a remote expert for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. In this study, as a first step, we investigated whether such practitioners could find a normal appendix, which is considered to be one of the most difficult tasks involved in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, as effectively under remote mentoring as they could under onsite mentoring.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

A randomized crossover study was conducted to compare the novice practitioners’ performance in identifying a normal appendix when guided by an onsite expert and when guided by a remote expert using a mobile device. The study was performed in the academic ED of a tertiary urban hospital from April to May 2015.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution.

Study Participants

The sample size was calculated based on a pilot study regarding the time required to identify the appendix. The required times (mean ± standard deviation (SD)) were as follows: under onsite mentoring (251.3 ± 17.1 s) and under remote mentoring (292.5 ± 88.3 s). The sample size was analyzed using G-power 3.1.2®(Heine Heinrich University, Düsseldorf, Germany) with 0.05 of α error and 0.8 of power, we estimated that 30 examiners would be adequate for each mentoring site with a 10 % dropout rate. Thirty volunteers without any experience in ultrasonography were recruited as examiners, and 10 volunteers with normal appendix, aged 19 to 35, were also recruited as simulated patients (SPs). In addition, three emergency physicians certified as trained abdominal ultrasonographers by the Korean Society of Ultrasound in Medicine (KSUM) participated in the study. The 30 novice examiners participated in a pre-education program consisting of a 2-h lecture and a hands-on workshop. SPs who were obese or whose appendix could not be identified by an expert within 5 min were excluded. All study participants agreed to participate in the study and completed a predesigned written consent form prior to participating in the study.

Tele-ultrasonography System

Tele-ultrasonography

An image capture and transmission system (CubeView, Alpinion Medical Systems, Seoul, Korea) was installed on the ultrasound machine (E-Cube 15, Alpinion Medical Systems, Seoul, Korea) in our ED. This system sequentially captures the images displayed on the monitor of an ultrasound machine and transmits them to a server computer at a rate of more than 25 frames per second (FPS) over a broadband internet network (with an internet speed of greater than 100 megabit per second (Mbps)). An internet protocol (IP) network camera was also set up above the ultrasonography machine and used to capture video of the ultrasound practice (background video). These background videos were simultaneously transmitted to the server along with the ultrasound sequence videos (Fig. 1). These combined videos (ultrasound sequence videos with background videos) were subsequently transferred from the server to a remote smartphone over an LTE network.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound sequence video and background video on the smartphone display

Remote Viewer: Smartphone

The smartphone used as the remote viewing display was the iPhone 5 (iPhone 5S, Apple Inc., USA), which is one of the most widely used and smallest smartphones on the market (dimensions of 123.8 × 58.6 × 7.4 mm, with a weight of 112 g). It has a small but high-resolution display screen with a diagonal dimension of 10.2 cm, a number of pixels of 1136 × 640 (326 PPI), a contrast ratio of 800:1, and a maximum luminance of 556 cd/m2. For this study, the luminance was set to 400 cd/m2 and the auto-brightness function was turned off, as recommended by the American College of Radiology (ACR). The CubeView smartphone application was downloaded to the iPhone to be used in the study [13]. The expert mentors were able to remotely guide the practice of the inexperienced practitioners while watching the full-motion sonographic examination videos and accompanying background videos transferred to the iPhone (Fig. 1).

Intervention

Of the three experts, one independent, blinded expert always acted as a supervisor, whereas the remaining two acted as the mentors (onsite and remote mentors). The supervisor observed the onsite examiners’ practice from behind and determined whether they had correctly located the normal appendix. If he was not certain whether their practice had succeeded or failed after its completion, he directly performed an additional ultrasonographic examination for confirmation. The onsite mentors directly guided the novice examiners in their ultrasound practice from beside them (onsite mentoring), whereas the remote mentors remotely guided them while watching their practice on the smartphone display (remote mentoring).

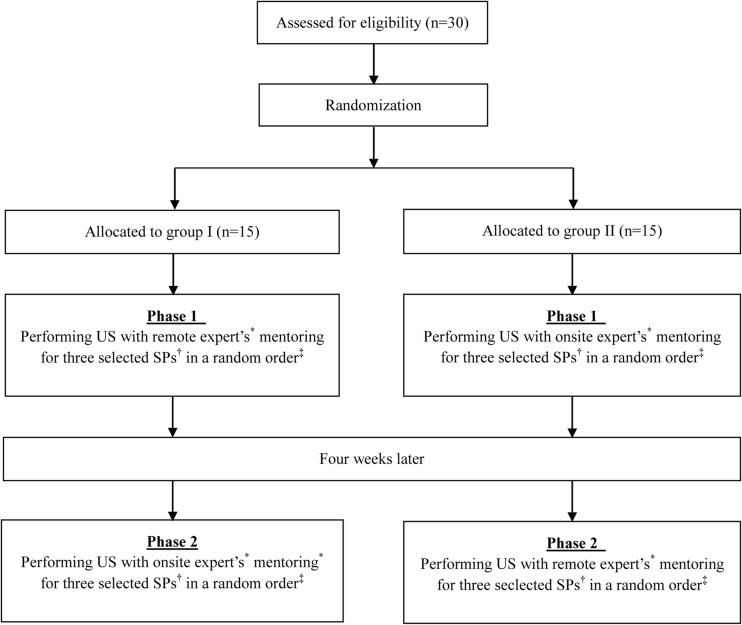

The 30 participating examiners were randomly divided into two groups. In phase 1, group A performed ultrasonography under onsite mentoring and group B performed the same procedure under remote mentoring (Fig. 2). Each examiner was randomly assigned one expert and three SPs for phase 1. Four weeks later, they were partnered with the same expert and SPs to whom they had been assigned in phase 1 and performed the procedure under the other type of mentoring (phase 2). The examination order of the SPs was randomly assigned by choosing a number between 1 and 6 (1—A-B-C, 2—A-C-B, 3—B-A-C, 4—B-C-A, 5—C-A-B, 6—C-B-A) in each phase (Table 1). The selection frequencies of the SPs and experts are shown in Table 2. The examiners were blinded to the identifying information of the SPs (their faces were shielded) as they performed the ultrasonographic examinations.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram. Asterisk, one of the two experts was randomly selected for each examiner in phase 1, and each examiner then worked with the same expert in phase 2. Dagger, three of the ten simulated patients were randomly selected for each examiner in phase 1, and each examiner then worked with the same simulated patients in phase 2. Double dagger, the examination order of the simulated patients was randomly assigned by choosing a number between 1 and 6 (1—A-B-C, 2—A-C-B, 3—B-A-C, 4—B-C-A, 5—C-A-B, 6—C-B-A) in each phase. US ultrasonography, SP simulated patient

Table 1.

Experts and simulated patients randomly assigned to each examiner for each examination session

| User | Onsite-expert-mentored US | Remote-expert-mentored US | Subjective image quality, mean (SD) | Mobile internet speed, Mbps, mean (SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPs in random order | Expert | SPs in random order | Expert | |||||||

| 1 | F | G | H | α | H | G | F | α | 4.7 | 41.1 |

| 2 | A | B | H | α | A | H | B | α | 4.7 | 57.5 |

| 3 | B | I | J | α | B | J | I | α | 4 | 50.1 |

| 4 | B | C | G | β | C | G | B | β | 5 | 57.9 |

| 5 | A | F | I | α | A | F | I | α | 4 | 66.2 |

| 6 | E | H | J | β | J | H | E | β | 4.7 | 55.4 |

| 7 | B | C | G | β | C | B | G | β | 4 | 55.8 |

| 8 | D | F | J | β | F | D | J | β | 4 | 58.1 |

| 9 | B | F | H | α | H | F | B | α | 4.3 | 45.2 |

| 10 | A | E | J | β | A | J | E | β | 5 | 41.1 |

| 11 | D | G | H | α | G | D | H | α | 4.7 | 57.5 |

| 12 | B | F | I | β | B | F | I | β | 4.3 | 50.1 |

| 13 | B | C | D | β | B | D | C | β | 4.3 | 57.9 |

| 14 | B | E | J | α | E | B | J | α | 4 | 66.2 |

| 15 | A | C | I | β | I | A | C | β | 4.3 | 55.4 |

| 16 | A | G | J | β | G | J | A | β | 4.7 | 55.8 |

| 17 | B | E | H | β | B | E | H | β | 4.3 | 58.1 |

| 18 | A | C | G | β | A | C | G | β | 4.3 | 45.2 |

| 19 | B | F | I | α | I | B | F | α | 4.7 | 41.1 |

| 20 | A | C | E | α | A | E | C | α | 5 | 57.5 |

| 21 | B | I | J | β | I | J | B | β | 4.3 | 50.1 |

| 22 | E | G | H | α | H | E | G | α | 4.3 | 57.9 |

| 23 | D | E | J | β | D | J | E | β | 4.7 | 66.2 |

| 24 | A | C | D | α | C | A | D | α | 4.3 | 55.4 |

| 25 | A | C | D | β | D | C | A | β | 5 | 55.8 |

| 26 | B | F | J | α | B | F | J | α | 4 | 58.1 |

| 27 | C | F | J | β | F | C | J | β | 5 | 45.2 |

| 28 | A | G | J | β | G | J | A | β | 4.3 | 74.8 |

| 29 | A | F | J | α | A | J | F | α | 5 | 74.3 |

| 30 | B | E | G | α | G | B | E | α | 4.7 | 54.6 |

| Total | 4.5 (0.4) | 55.5 (8.6) | ||||||||

US ultrasonography, SP simulated patient, SD standard deviation

Table 2.

Selection frequencies of the simulated patients, overall and for each expert

| Simulated patients | Frequency, n (%) | Expert α | Expert β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, n (%) | Frequency, n (%) | ||

| A | 22 (12.2) | 10 (11.9) | 12 (12.5) |

| B | 26 (14.4) | 14 (16.7) | 12 (12.5) |

| C | 18 (10.0) | 4 (4.8) | 14 (14.6) |

| D | 12 (6.7) | 4 (4.8) | 8 (8.3) |

| E | 16 (8.9) | 8 (9.5) | 8 (8.3) |

| F | 18 (10.0) | 12 (14.3) | 6 (6.3) |

| G | 18 (10.0) | 8 (9.5) | 10 (10.4) |

| H | 14 (7.8) | 10 (11.9) | 4 (4.2) |

| I | 12 (6.7) | 6 (7.1) | 6 (6.3) |

| J | 24 (13.3) | 8 (9.5) | 16 (16.7) |

| Total | 180 (100) | 84 (100) | 96 (100) |

The remote experts recorded their subjective image quality assessment scores for the transmitted images displayed on the smartphone using a five-point Likert scale (single-stimulus method: 1 = bad, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = excellent) and gauged the connection speed of the LTE network using the smartphone application BENCHBEE at the end of each telementoring session [13].

Main Results

The primary outcomes were the success rate for identifying the normal appendix and the time elapsed before the practitioner located the appendix.

The success of appendix identification for each session was determined by the supervisor, who observed the onsite examiners’ practice from behind. He recorded whether the examiner had successfully located the appendix. The time was measured from the beginning of the examination to the detection of the suspected appendix. When 10 min of time had passed without successful detection, the session was defined as a failure and the time was recorded as 10 min.

Statistical Analysis

The difference between the success rates for identifying the appendix under remotely guided mentoring and onsite-guided mentoring was analyzed using the chi-square test. The difference in the time required for the detection of the appendix between the two methods was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

The mean scores for subjective image quality assessment were calculated, and a score greater than 4 was regarded as indicative of high quality [14–17].

Results

Participants

Of the 30 novice examiners, none was excluded or eliminated from the study. The mean age of the participants was 27.8 years old (SD, 2.4), and 18 were male (Table 3). Of the ten SPs, six were male, and their mean age was 28.4 years old (SD, 1.4). Their heights, weights, and BMIs are shown in Table 4. No obese SP was included in the study. The maximal diameters of their appendices are also shown in Table 4. For seven SPs, the position of the appendiceal base was retrocecal, and the remaining three had subileal appendices. Each examiner performed ultrasonographic examinations of three SPs; thus, a total of 90 examinations were performed in each scenario.

Table 3.

General characteristics of the novice examiners

| Characteristic | Group A n = 15 |

Group B n = 15 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 8 (53.3) | 10 (66.7) | 18 (60.0) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 28.1 (2.3) | 27.6 (2.4) | 27.8 (2.4) |

Table 4.

General characteristics of each simulated patient

| Simulated patient | Sex | Age, years | Height, cm | Weight, kg | BMI, kg/m2 | Maximal diameter of the appendix, mm | Position of the appendiceal base |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | 29 | 175 | 63 | 21 | 3.5 | Retrocecal |

| B | M | 27 | 171 | 55 | 19 | 4.1 | Retrocecal |

| V | M | 28 | 178 | 71 | 22 | 3.6 | Retrocecal |

| D | F | 30 | 165 | 59 | 22 | 4.6 | Subileal |

| E | F | 28 | 155 | 52 | 22 | 4.1 | Subileal |

| F | M | 27 | 170 | 60 | 21 | 3.7 | Retrocecal |

| G | F | 28 | 168 | 61 | 22 | 4 | Retrocecal |

| H | M | 31 | 173 | 65 | 22 | 3.5 | Subileal |

| I | F | 29 | 161 | 54 | 21 | 3.2 | Retrocecal |

| J | M | 27 | 176 | 68 | 22 | 4.2 | Retrocecal |

| Mean (SD) | 28.4 (1.4) | 169.2 (7.2) | 60.8 (6.1) | 21.4 (1.0) | 3.9 (0.4) |

BMI body mass index, SD standard deviation

Success Rate for Finding the Appendix

Of the 90 examinations, 82 (91.1 %) were completed with successful identification of the normal appendix within 10 min when the novice examiners were performing ultrasonography with an onsite expert’s guidance (Table 5). With a remote expert’s guidance, they were able to succeed in finding the appendix in 79 of the 90 examinations (87.8 %). The difference in success rate between the two groups was not significant (p = 0.468). In the case of onsite guidance, in all eight cases of failure, the appendix was missed because the novice examiner could not find the appendix within 10 min, and in 10 of the 11 cases of failure under remote guidance, the appendix was missed for the same reason. In only one case, although the examination was completed within 10 min, it was a failure because the remote expert misinterpreted the terminal ileum as the appendix.

Table 5.

Comparison of sonographic performance between the onsite and remote mentoring settings

| Onsite-expert-mentored US, n = 90 | Remote-expert-mentored US, n = 90 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time required to identify the appendix, s, mean (SD) or median (IQR) | 242.9 (238.2) | 291.4 (200.9) | 0.051a |

| Success, n (%) | 82 (91.1) | 79 (87.8) | 0.468b |

aCalculated using the Mann–Whitney U test

bCalculated using the chi-square test

US ultrasonography, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

Time Required to Identify the Appendix

The mean time required to locate the appendix was 242.9 s (interquartile range (IQR), 238.2) when the novice examiners were performing ultrasonography with the guidance of an onsite expert, and it was 291.4 s (IQR, 200.9) when they were performing ultrasonography with a remote expert’s guidance (Table 5). The time required during offsite mentoring was longer than that during onsite mentoring; however, it was not significantly different (p = 0.051).

Subjective Assessments of Image Quality and Mobile Internet Speed

The mean subjective image quality assessment score for all physicians’ examinations using the smartphone display was 4.5 (SD, 0.6), and none of the mean scores for any physician was less than 4 (Table 1).

The mean mobile internet speed at the end of a remote mentoring session was 55.5 Mbps (SD, 8.6).

Discussion

The first step in ultrasonography for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis is identifying the appendix. Although the most common position for the base of the appendix is retrocecal, it varies in each patient. The appendix often cannot be visualized even when a trained sonographer performs the ultrasonographic imaging. Certain patients may have an ambiguous appendix that is difficult to differentiate from other intraperitoneal organs, especially the terminal ileum. In this study, we verified that this complex process of identifying the appendix could be guided by a remote expert using smartphone-based telesonography as effectively as by an onsite expert, even though the practitioners were novice examiners. The success rate for identifying the appendix was high in both groups and did not significantly differ between them. This suggests that telesonography can be used to acquire the necessary images for diagnosis, a task that requires relatively high proficiency in ultrasonography, even when no experienced sonographer is available onsite. The high observed success rate may be partially attributable to the fact that cases in which the appendix could not be identified by an expert were excluded in this study. Moreover, in most cases addressed in this study, the appendix was in the typical position. The rate of normal appendix identification could be lower in a real clinical situation as a result of various adverse conditions, such as an atypical position of the appendix, an obese abdomen, or a large amount of gas. However, the rates of decrease might not significantly differ between the two methods. Moreover, the likelihood of successfully identifying the appendix might be higher in pediatric patients than in the study group considered here because the resolution of images of the appendix produced by ultrasound probes in children, who are more vulnerable to appendicitis, is higher than that in adults because of their small size [18]. In addition, the sensitivity for identifying the appendix should be increased in the case of acute appendicitis because the swollen appendix that is characteristic of acute appendicitis is likely to be more easily found in an ultrasound examination than the smaller normal appendix.

In most cases of failure, the appendix was missed because the novice examiner could not find it within 10 min despite being guided by an expert. This failure can likely be attributed to the novice examiners’ inability to dexterously operate the probe in precise accordance with the expert’s direction. However, this lack of coordination between the expert’s direction and the examiner’s hand was not significantly different between onsite and remote mentoring. We were initially concerned that offsite mentoring might be disadvantageous in comparison with onsite face-to-face mentoring because it must be performed using a small display, with additional limitations posed by the lack of proximity. Indeed, the mean time required to finish the examination was longer in the case of remote mentoring than that for onsite mentoring, although the time difference was not statistically significant. An additional 50 s may not pose a significant problem in an ultrasound examination for identifying the appendix. However, such a delay could be critical in certain types of emergency ultrasonography for unstable patients.

Once the structure that was believed to be the appendix was found, all except 1 of the 90 cases of remotely guided ultrasonography were correctly interpreted. In other words, there was almost no case in which remote interpretation was disrupted by the attenuated quality of the transmitted images, even though the process of identifying the appendix sometimes requires the ability to perceive subtle findings. In fact, the human perception of the image quality of the transmitted images displayed on the smartphone was very good, as indicated by the mean subjective image quality assessment score of greater than 4 reported in this study, which is consistent with that in a previous study [12]. The single-stimulus method for subjective quality assessment is known to be the most accurate method of evaluating the human perception of image quality [12, 16, 17]. The typical image size of a single frame captured by the CubeView image capture and transmission system is approximately 150 kilobytes (kB) in PNG format, as mentioned in previous studies [8, 12]. These frames can theoretically be transmitted at more than 15 FPS if the internet connection speed is greater than 18 Mbps, thereby allowing them to be perceived by the human eye as continuous images without any interruption in motion [15]. Because the average connection speed of the LTE mobile network in South Korea was 67.4 Mbps during the 4th quarter of 2015, as reported by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of South Korea [19], and that measured by BENCHBEE in this study was 55.5 Mbps, high-quality lossless images could be continuously transmitted from the ultrasound machine to the smartphone display without any interruption in motion (without lag, pixilation, or any other degradation) during this study. Given that 3rd generation (3G) networks are more widely used than LTE networks worldwide, even though LTE networks have been established in many countries, the ability to use telementored ultrasonography in under-resourced countries would be limited. However, the telesonography system used in this study allows the modification of the image quality of the transmitted videos. If the spatial resolution of a single frame is reduced to 80 % of the initial resolution, the file size decreases from approximately 150 to 40 kB [8]. Images with a file size of 40 kB can be continuously transmitted at a frame rate of 15 FPS even with a connection speed of approximately 5 Mbps. We believe that 80 % of the quality of the original image is sufficient to enable effective evaluation in several clinical settings. In fact, a previous study verified that echocardiography videos of this reduced image quality (80 % of the quality of the original image) transmitted to a smartphone over a 3G mobile network could be effectively interpreted for the evaluation of cardiac dynamic function [8]. Thus, this type of smartphone-based telesonography can be applied in certain clinical situations over a 3G mobile network.

We used a smartphone rather than a workstation as the remote display in this study because of its accessibility for immediate use. In real clinical settings, most expert physicians will typically guide a remote novice examiner in performing ultrasonography by using the workstations in their offices rather than smartphones with small displays. However, these experts are sometimes out of their offices and unable to immediately access a workstation when they are requested to direct remote ultrasonography. Based on the results of this study, we believe that workstation-based telesonography will certainly be feasible as well.

The three experts who participated in this study each possess at least 5 years of experience with abdominal ultrasonography in the ED and are especially skillful at diagnosing acute appendicitis. All are certified as trained abdominal ultrasonographers by KSUM, and the expert who acted as the supervisor (with 10 years of ultrasonography experience) is also certified as an instructor of abdominal ultrasonography by that society. In fact, these practitioners performed zero negative appendectomies and had zero cases of missed appendicitis between September 2011 and February 2013, although the study populations were somewhat selective [20]. We believe that they are as proficient as radiologists in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. The two mentors had gained previous experience with telemedicine from participating in previous studies over the past 3 years [3, 4, 8, 12]; thus, they were already somewhat proficient at interpreting transmitted images using a smartphone with a small display. However, we are certain that a user without any previous experience with telemedicine could easily become accustomed to the necessary procedures with a small amount of practice prior to use.

To ensure well-coordinated manipulation of the probe by an inexperienced examiner, careful and detailed instructions must be provided. For this purpose, the mentor must know how to operate the probe for concrete identification of the relevant findings. Additionally, he or she must know the spatial relationship among the intraperitoneal organ structures around the appendix. In the process of mentoring, the mentors directed the novice examiners to mark the corresponding positions on the patient’s abdomen when they found the main structures needed to identify the appendix, such as the cecum, ileocecal valve, psoas muscle, and iliac vessels. If they became lost on the way to the appendix, the mentor instructed the examiner to move the probe to an indicated point. They often used these points as landmarks for controlling the examiner’s probe. For example, supposing that the ileocecal valve was shown on the monitor, the mentor informed the examiner of what the structure was and asked him/her to move the probe to the point indicating the psoas muscle. This process facilitated clear communication between the mentor and examiner.

In conclusion, it appears that offsite mentoring can allow novice onsite practitioners to perform ultrasonography as effectively as they could under onsite mentoring, even for examinations that require proficiency in rather complex practices, such as identifying the appendix. This type of telesonography could be applied in under-resourced regions and hospitals to overcome a lack of human resources. It could also be used in a prehospital setting. Telesonography performed by an emergency medical technician under the guidance of a remote expert could play an important role in the management of patients before hospital arrival or in decision-making regarding the level of the referred hospital. In addition, this telesonographic approach could serve as the basis of an educational model for inexperienced practitioners and could provide possibilities for expanding the use of ultrasonography in war and disaster situations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alpinion Medical Systems, which developed the tele-ultrasonography system in collaboration with us and provided this system to us free of charge for this study.

Abbreviations

- LTE

Long-Term Evolution

- IQR

Interquartile range

- CT

Computed tomography

- ED

Emergency department

- SD

Standard deviation

- SP

Simulated patient

- KSUM

Korean Society of Ultrasound in Medicine

- FPS

Frames per second

- Mbps

Megabit per second

- IP

Internet protocol

- ACR

American College of Radiology

- KB

Kilobytes

- 3G

3rd generation

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding Source

No external funding was secured for this study.

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Park JB, Choi HJ, Lee JH, Kang BS. An assessment of the iPad 2 as a CT teleradiology tool using brain CT with subtle intracranial hemorrhage under conventional illumination. J Digit Imaging. 2013;26:683–690. doi: 10.1007/s10278-013-9580-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi HJ, Lee JH, Kang BS. Remote CT reading using an ultramobile PC and web-based remote viewing over a wireless network. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:26–31. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.110412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim C, Kang BS, Choi HJ, et al. Nationwide online social networking for cardiovascular care in Korea using Facebook. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:17–22. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim C, Kang B, Choi HJ, Park JB. A feasibility study of real-time remote CT reading for suspected acute appendicitis using an iPhone. J Digit Imaging. 2015;28:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s10278-015-9775-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlechtweg PM, Kammerer FJ, Seuss H, Uder M, Hammon M: Mobile image interpretation: diagnostic performance of CT exams displayed on a tablet computer in detecting abdominopelvic hemorrhage. J Digit Imaging 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Seong NJ, Kim B, Lee S, et al. Off-site smartphone reading of CT images for patients with inconclusive diagnoses of appendicitis from on-call radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:3–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz AB, Siddiqui G, Barbieri JS, et al. The accuracy of mobile teleradiology in the evaluation of chest X-rays. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20:460–463. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14555639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim C, Cha H, Kang BS, Choi HJ, Lim TH, Oh J: A feasibility study of smartphone-based telesonography for evaluating cardiac dynamic function and diagnosing acute appendicitis with control of the image quality of the transmitted videos. J Digit Imaging 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ogedegbe C, Morchel H, Hazelwood V, Chaplin WF, Feldman J. Development and evaluation of a novel, real time mobile telesonography system in management of patients with abdominal trauma: study protocol. BMC Emerg Med. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBeth P, Crawford I, Tiruta C, et al. Help is in your pocket: the potential accuracy of smartphone- and laptop-based remotely guided resuscitative telesonography. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:924–30. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biegler N, McBeth PB, Tiruta C, et al. The feasibility of nurse practitioner-performed, telementored lung telesonography with remote physician guidance—‘a remote virtual mentor.’. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5:5. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim C, Kang BS, Choi HJ, Lim TH, Oh J, Chee Y. Clinical application of real-time tele-ultrasonography in diagnosing pediatric acute appendicitis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:1354–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.iTunes. Accessed January 5 2016. Available at http://www.apple.com/itunes

- 14.Huynh-Thu Q, Ghanbari M. Temporal aspect of perceived quality in mobile video broadcasting. IEEE Trans on Broadcast. 2008;54:641–651. doi: 10.1109/TBC.2008.2001246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agboma F, Liotta A. Quality of experience management in mobile content delivery systems. Telecommun. Syst. 2012;49:85–98. doi: 10.1007/s11235-010-9355-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assembly ITU Radiocommunication. BT-500.13. Methodology for the subjective assessment of the quality of television pictures. International Telecommunication Union 2012

- 17.Kim SC, Kim BI. Analysis on subjective image quality assessments for smart phone/pad environments. Electronics and Telecommunications Trends. 2013;28:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puylaert JB. Ultrasonography of the acute abdomen: gastrointestinal conditions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:1227–1242. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of South Korea: The result of the quality of wireless communication services in Korea in 2015. Accessed on January 5 2016. Available at http://www.msip.go.kr/web/msipContents/contentsView.do?cateId=mssw311&artId=1233890&snsMId=NzM%3D&getServerPort=80&snsLinkUrl=%2Fweb%2FmsipContents%2FsnsView.do&getServerName=www.msip.go.kr Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6eKM8BPbZ

- 20.Kim C, Kang B, Park JB, Ha YR. The use of clinician-performed ultrasonography to determine the treatment method for suspected paediatric appendicitis. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2015;22:31–40. [Google Scholar]