Abstract

MAP kinases (mitogen-activated protein kinases) are activated by dual phosphorylation on specific threonine and specific tyrosine residues that are separated by a single residue, and the TXY activation motif is a hallmark of MAP kinases. In the fungus Ustilago maydis, which causes corn smut disease, the Crk1 protein, a kinase previously described to have roles in morphogenesis, carries a TXY motif that aligns with the TXY of MAP kinases. In this work, we demonstrate that Crk1 is activated through a mechanism that requires the phosphorylation of this motif. Our data show that Fuz7, a MAPK kinase involved in mating and pathogenesis in U. maydis, is required to activate Crk1, most likely through phosphorylation of the TXY motif. Consistently, we found that Crk1 is also required for mating and virulence. We investigated the reasons for sterility and avirulence of crk1-deficient cells, and we found that Crk1 is required for transcription of prf1, a central regulator of mating and pathogenicity in U. maydis. Crk1 belongs to a wide conserved protein group, whose members have not been previously defined as MAP kinases, although they carry TXY motifs. On the basis of our data, we propose that all of these proteins constitute a new family of MAP kinases.

Keywords: Crk1, Ustilago maydis, MAP kinase, signal transduction, fungal virulence, sexual development

Protein kinase cascades regulate cellular events in response to many types of external and internal stimuli. MAP kinase (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascades are ancient and conserved signaling cassettes found in unicellular and multicellular eukaryotes (Widmann et al. 1999). Each MAP kinase module comprises a series of three or more kinases, each phosphorylating, and thereby activating the next in line. The last kinase of the series (the MAP kinase or MAPK) is activated by dual phosphorylation on a specific threonine and a specific tyrosine residue. The two activating phosphorylation sites are separated by a single residue, and the TXY activation motif is a hallmark of MAP kinases (Kültz 1998). Both residues are phosphorylated by a dual-specific kinase, the MAPK kinase (MAPKK), which is activated in turn by phosphorylation on one or more serine or threonine residues by a MAPKK kinase (MAPKKK). Different MAP kinase cascades are present in a single cell and often share common components. There is some cross-talk between pathways, but MAP kinase cassettes appear to be insulated from each other by the intrinsic specificity of the MAPKKs and MAPKKKs, and by binding interactions that are thought to organize the cassettes into multienzyme complexes (Cano and Mahadevan 1995; Whitmarsh and Davis 1998; Sabbagh et al. 2001). The physiological significance of this modular arrangement of kinases cascades is not entirely understood, but it is speculated that it may serve for amplification and integration of external signals at the cellular level (Herskowitz 1995).

In pathogenic fungi, conserved signaling cascades control distinct stages of the diseases process (Xu 2000). In the fungus Ustilago maydis, which causes corn smut disease, a MAPK cascade consisting of MAPKKK Kpp4/Ubc4 (Andrews et al. 2000; Müller et al. 2003), MAPKK Fuz7 (Banuett and Herskowitz 1994), and MAPK Kpp2/Ubc3 (Mayorga and Gold 1999; Müller et al. 1999) regulates mating and pathogenic development. Mutant cells in any of these genes are severely impaired in mating and pathogenicity (Banuett and Herskowitz 1994; Mayorga and Gold 1999; Müller et al. 1999, 2003). The Kpp4/Fuz7/Kpp2 MAPK cascade is also required to respond to environmental cues, such as the presence of lipids or acid pH (Klose et al. 2004; Martinez-Espinoza et al. 2004). In addition, this MAPK module has roles in morphogenesis. Mutations in ubc4/kpp4, fuz7/ubc5, or ubc3/kpp2 were shown to suppress the filamentous phenotype of mutants in the adenylate cyclase gene uac1 or in the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A adr1 (Gold et al. 1994; Mayorga and Gold 1998, 1999; Andrews et al. 2000; Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). The dual role of a MAPK cascade in morphogenesis and mating is reminiscent of the situation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where elements of the MAP kinase cascade involved in mating response are also involved in filamentation and invasive growth (Roberts and Fink 1994). However, in contrast to the S. cerevisiae situation, where the MAP kinases Fus3 and Kss1 control mating response and filamentation, respectively (Madhani and Fink 1998), in U. maydis a single MAP kinase, Ubc3/Kpp2, appears to be involved both in pheromone transmission and filamentation (Mayorga and Gold 1999; Müller et al. 1999). Pheromone transmission appears to act by feeding the transcriptional activator Prf1 (Kaffarnik et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2003). Prf1 is an HMG class transcription factor, which is required for the expression of mating-type genes (Hartmann et al. 1996). A crucial element in filamentation is the Crk1 protein kinase (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). Overexpression of the crk1 gene resulted in a hyperpolarized growth, and deletion of the crk1 gene abolished the filamentous phenotype of adr1 mutants (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). Crk1 is connected to the MAPK cascade, since the Kpp2/Ubc3 MAPK is required for high levels of crk1 expression (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). Crk1 belongs to a conserved family of protein kinases, with predicted members in all eukaryotic taxa analyzed. Interestingly, all members whose functions are known play roles in the sexual cycle in their respective organisms; the S. cerevisiae Ime2 is involved in meiosis induction (Mitchell 1994); two Ime2 orthologs in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Mde3 and Pit1 are important for timing of the meiotic division and are essential for spore morphogenesis (Abe and Shimoda 2000) and in mammals a “male germ cell-associated kinase” Mak, has an expression pattern that links this factor with sexual development (Jinno et al. 1993; Shinkai et al. 2002). Here, we describe a role of Crk1 in the induction of sexual as well as pathogenic development in U. maydis. Moreover, we provide evidence that Crk1 is activated by the same MAPK kinase that is required for pheromone signaling. Our results support the view that Crk1, as well as other kinase proteins belonging to the same group, constitute a new MAPK family with roles in sexual development in eukaryotes.

Results

Crk1 is required for mating and pathogenicity

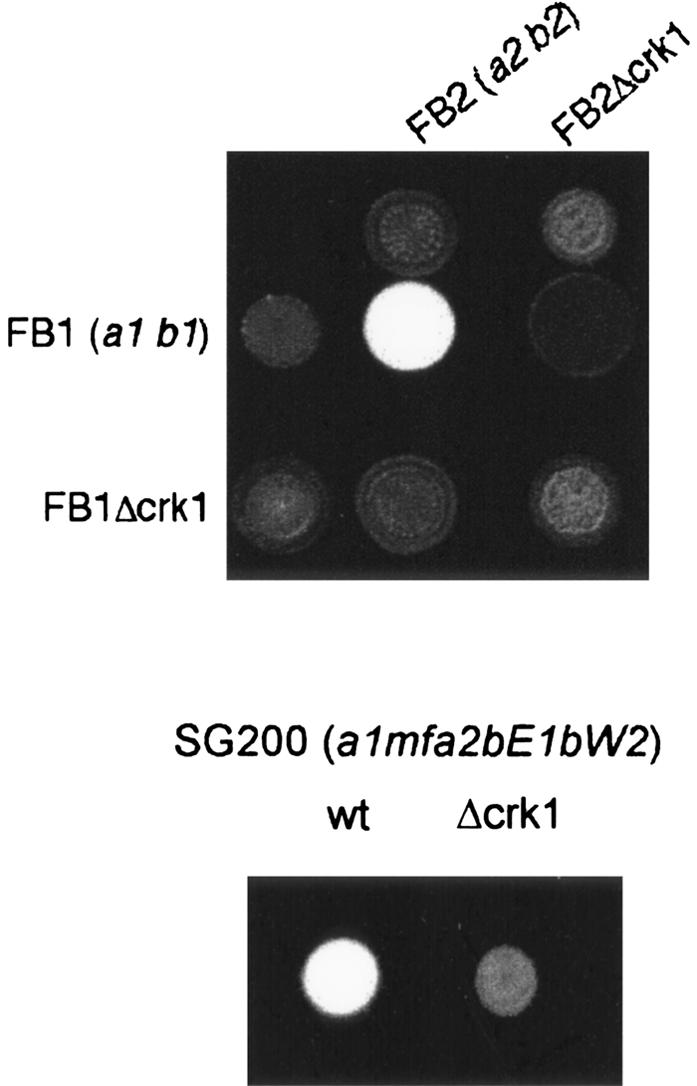

In U. maydis, the mating reaction can be easily scored by cospotting compatible strains on solid medium containing charcoal. On these plates, successful fusion of compatible strains results in the formation of the filamentous dikaryon, which appears as a white fuzzy layer on the surface of the growing colony (Fuz+ phenotype) (Holliday 1974). We observed that a mixture of two compatible Δcrk1 strains failed to develop the Fuz+ phenotype (Fig. 1, cf. the control mating reactions between compatible wild-type strains producing a clear Fuz+ phenotype). Furthermore, wild-type strains, when crossed with compatible Δcrk1 strains, were also unable to produce the Fuz+ phenotype, which indicated that Crk1 was required for cell fusion. To address the question of whether crk1 has additional functions after cell fusion, we took advantage of the solopathogenic SG200 strain, which is a haploid strain that carries the genetic information from the two different mating types, and as a consequence, does not require cell fusion to produce the infective hypha (Bölker et al. 1995). Deletion of the crk1 gene in SG200 resulted in strongly attenuated filament formation (Fig. 1). This result illustrated that crk1 is required on preand post-fusion levels.

Figure 1.

Crk1 is required for successful mating in U. maydis. Mating assays on plates containing activated charcoal. Dikaryotic filaments resulting from a successful mating appears as white fuzziness. The strains indicated on the top were spotted alone and in combination with the strains indicated on the left on charcoal-containing PD plates. SG200 is a solopathogenic strain that does not require cell fusion to develop infective filaments.

Since mating and pathogenicity are linked, we also examined the pathogenicity of Δcrk1 cells. Corn plants were infected with mixtures of compatible Δcrk1 mutants, with the solopathogenic SG200Δcrk1 strain, or with the respective wild-type strains as controls (Table 1). We observed tumor formation in >75% and 80% of plants infected with compatible wild-type strains or SG200, respectively, while infection with Δcrk1 mutants resulted in a dramatic reduction in the ability to induce symptoms. Tumor formation was observed in only nine of 112 plants infected with compatible Δcrk1 mixtures (Table 1). These infected plants showed only a small number of tumors (one or two at best), they were quite small in size, and closer inspection of the observed tumors revealed an absence of the melanized teliospores typically found in tumor tissue infected with wild-type cells (data not shown). In addition, none of the 94 plants infected with SG200Δcrk1 developed tumors. These data indicated that crk1 was required for pathogenicity, even when cell-cell fusion was not required.

Table 1.

Plant infection assays

| Anthocyanin formation

|

Tumor formation

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculum | Infected plants | Total | Percentage | Total | Percentage |

| FB1 × FB2 | 66 | 55 | 83.3 | 50 | 75.8 |

| FB1 × FB2Δcrk1 | 73 | 54 | 73.9 | 35 | 47.9 |

| FB1Δcrk1 × FB2Δcrk1 | 112 | 14 | 12.5 | 9a | 8 |

| FB1Δcrk1 × FB2pra2con | 70 | 51 | 72.8 | 33 | 47.1 |

| FB1Δcrk1 × FB2Δcrk1 pra2con | 76 | 50 | 65.8 | 35a | 46.1 |

| SG200 | 70 | 62 | 88.6 | 66 | 80 |

| SG200 Δcrk1 | 94 | 6 | 6.4 | 0 | 0 |

| SG200prf1con | 34 | 32 | 94.1 | 30 | 88.2 |

| SG200 Δcrk1prf1con | 31 | 29 | 93.5 | 27 | 87.1 |

| HA103 | 37 | 31 | 83.8 | 31 | 83.8 |

| HA103 Δcrk1 | 73 | 59 | 80.8 | 50 | 68.5 |

Formation of teliospores could not be observed.

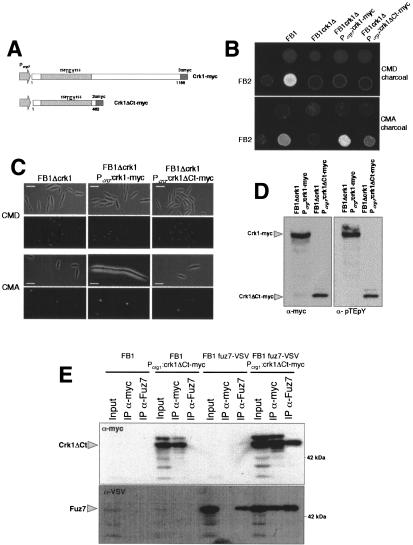

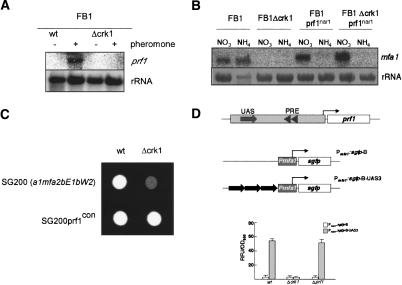

The Crk1 protein is activated by phosphorylation at the T-loop

MAP kinases are activated by dual phosphorylation of a T-loop TXY motif located 10 residues upstream of the catalytic APE motif in subdomain VIII. Crk1 contains a TEY motif that aligns with the TXY of MAP kinases (Fig. 2A), suggesting that this motif could be a target of phosphorylation. To examine Crk1 phosphorylation directly, we used an antibody raised against the phosphoepitope found in mammalian ERK1 and ERK2 that specifically recognizes the dually phosphorylated isoforms of MAPKs (Khokhlatchev et al. 1997). Because Western blots did not allow the detection of endogenous myc-tagged Crk1 protein (data not shown), we used an epitope myc-tagged version of the crk1 gene under the control of the crg1 promoter (which is repressed by glucose and induced by arabinose) (Bottin et al. 1996). This epitope-tagged version of Crk1 was fully functional, and complements the defects in mating and morphogenesis of a Δcrk1 strain (data not shown). After induction, the phosphoepitope-specific MAPK antibody was able to detect a band around the predicted size of Crk1 that was also recognized by the anti-myc antibody (Fig. 2B). This positive reaction with the anti-activated MAPK was lost if cell extracts were treated with λ phosphatase prior to Western blot assay (data not shown). These results indicated that Crk1 was phosphorylated at the T-loop.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of Crk1 T-loop is required for in vivo activity. (A) crk1 and crk1AEF both fused to myc epitope under the control of Pcrg1 and are shown schematically. (Top) Sequences surrounding the TEY motif and the WYRAPE motif found in kinase subdomain VIII from Crk1 are shown. (B) Phosphorylation of T-loop of Crk1. Extracts were prepared from UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc) and UME62 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AEF-myc) cultures grown in inducing conditions (CMA, complete medium with 1% arabinose) or repressive conditions (CMD, complete medium with 1% glucose) at OD600 of 0.5. The same blot, after stripping steps, was incubated with anti-pTEpY to detect T-loop phosphorylation and with anti-myc to detect myc-tagged proteins. As an internal loading control, we used anti-PSTAIRE to detect Cdk1. (C) The T-loop phosphorylation is required for successful mating on charcoal plates. FB1, UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), and UME62 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AEF-myc) cells were cospotted with FB2 cells in charcoal-complete medium plates with glucose (CMD charcoal) or arabinose (CMA charcoal) as carbon source. (D) Requirement of T-loop phosphorylation for Crk1-mediated hyperpolarized growth. UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), and UME62 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AEF-myc) cells were incubated in CMD and CMA for 6 h. Bar, 10 μm.

To determine whether Crk1 phosphorylation was required for in vivo activity, a mutant of Crk1 (Crk1AEF) was expressed in a strain lacking endogenous Crk1. Crk1AEF contains mutations (T253A, Y255F) in the conserved phosphoaceptor site and should therefore be unable to accept phosphates at the conserved TEY motif. We found no reaction using the phosphoepitope-specific MAPK antibody with proteins extracted from the strain expressing the Crk1AEF variant (Fig. 2B). In addition, cells expressing the Crk1AEF protein were unable to develop dikaryotic hyphae on charcoal plates containing arabinose (Fig. 2C) and were unable to induce hyperpolarized growth, a phenotype that associates Crk1 with a morphogenetic activity (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003) (Fig. 2D). These results are consistent with a requirement of T-loop phosphorylation for in vivo activity.

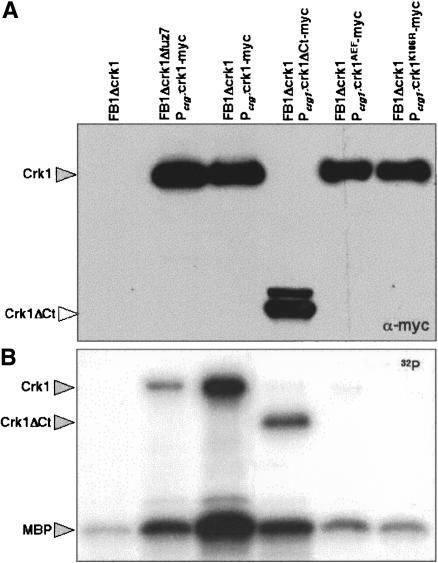

As a final means to verify the phosphorylation-dependent activation of Crk1, the catalytic activity of Crk1 was directly monitored in an immunoprecipitation-kinase assay. First, as a negative control, we constructed a strain carrying a catalytically inactive Crk1 variant, Crk1K106R, which should encode a kinase-dead mutant protein, due to a defect in ATP-binding capacity. This mutant version was phosphorylatable, but displayed no activity in mating assays and was unable to induce hyperpolarized growth in strains deleted for crk1 (data not shown). Cell extracts were prepared, epitope-tagged Crk1 proteins were immunoprecipitated, and their ability to phosphorylate Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) was determined (Fig. 3). Wild-type Crk1 protein phosphorylated MBP at significant levels. In contrast, immunoprecipitated Crk1K106R and Crk1AEF showed strongly reduced phosphorylation of MBP. In this assay, phosphorylation of a protein around the size of Crk1 was also detected. As the appearance of this phosphorylated species depended on the presence of a catalytically active version of a Crk1 allele, it suggests that Crk1 displays autophosphorylation activity, as has been reported in other MAP kinases (Brill et al. 1994; Zaitsevskaya-Carter and Cooper 1997). Taken together, these results support the notion that kinase activity of Crk1 was dependent on T-loop phosphorylation.

Figure 3.

Catalytic activity of Crk1 and derivates. Myc-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cells extracts prepared from UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME63 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc Δfuz7), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), UME66 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1ΔCt-myc), UME62 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AEF-myc), and UME69 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crkK106R-myc) cells grown to OD600 of 0.5 in CMA. Protein kinase activity was measured by incubation of immunoprecipitates with purified Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) as substrate and [γ-32P]ATP. (Top) An 8% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with anti-myc was used to show comparable levels of Crk1 proteins in the reaction mixtures. (Bottom) A 12.5% SDS-PAGE and autoradiography was used to detect in vitro phosphorylated MBP. We also found bands corresponding to autophosphorylated Crk1 and derivates.

The MAPKK Fuz7 is required for Crk1 activity

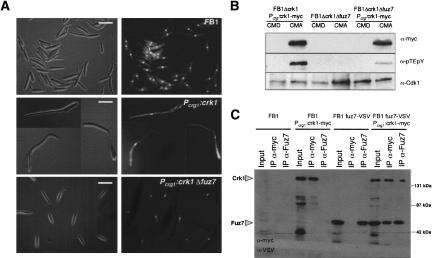

MAPK kinases activate MAPK by dual phosphorylation at the TXY motif. In the previous sections, we showed that Crk1 has to be phosphorylated at the TXY motif to be active in vitro and in vivo. We also showed that Crk1 is required for mating and pathogenicity. In U. maydis, mating and pathogenicity is dependent on fuz7, which encodes a MAPK kinase (Banuett and Herskowitz 1994; Müller et al. 2003). Therefore, we wondered whether Fuz7 was required for Crk1 activity. We examined whether deletion of fuz7 affected the ability of Crk1 to induce hyperpolarized growth when expressed at high levels. Wild-type cells overproducing the tagged Crk1 protein displayed strong hyperpolarized growth. In contrast, when crk1 was overexpressed in cells deficient in fuz7, no alterations of cell morphology were apparent (Fig. 4A). In these strains, the level of Crk1-myc protein in induced conditions was similar (data not shown). These results indicate that Fuz7 affects Crk1 in vivo activity.

Figure 4.

Fuz7 is required for Crk1 T-loop phosphorylation. (A) Requirement of Fuz7 for Crk1-mediated hyperpolarized growth. FB1, UME61 (FB1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc), and UME63 (FB1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc Δfuz7) cells were incubated in CM-arabinose for 6 h. (Right) DAPI staining of the same cell field. Bar, 10 μm. (B) T-loop phosphorylation of Crk1 in vivo is dependent on Fuz7. Cell extracts were prepared from UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), UME60 (FB1 Δcrk1 Δfuz7), and UME63 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc Δfuz7) cells and analyzed as described in Figure 2. (C) Crk1 and Fuz7 coprecipitate. Cultures of FB1, UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), UMS19 (FB1 fuz7-VSV), and UMS20 (FB1 fuz7-VSV Pcrg1:crk1-myc) strains grown in CMA until OD600 of 0.5 were used to prepare whole-cell extracts (WCE). Immuno precipitants obtained with anti-myc and anti-Fuz7 were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-VSV-peroxidase and anti-myc-peroxidase antibodies.

Next, we wondered whether phosphorylation of Crk1 at the T-loop was dependent on Fuz7. To address this question, we analyzed the T-loop phosphorylation level of Crk1 in a Δfuz7 strain, and we found that it was severely reduced (Fig. 4B). Consistently, Crk1 immunoprecipitated from a strain lacking Fuz7 displayed an impaired ability to phosphorylate MBP as well as itself (Fig. 3). These results indicated that phosphorylation of the T-loop, and hence, catalytic activity of Crk1, were dependent on the Fuz7 MAPK kinase.

To further support the relationships between Fuz7 and Crk1, we examined whether these two proteins physically associate. We expressed the myc-tagged Crk1 protein in a U. maydis strain carrying a functional version of the Fuz7 kinase tagged at its C-terminal end with the VSV epitope. Immunoprecipitants from cell extracts were obtained using anti-myc antibody (directed against myc-tagged Crk1) or antibodies directed against Fuz7, and the presence of Fuz7 or Crk1, respectively, was analyzed. We detected a positive association, irrespective of whether Crk1 or Fuz7 were precipitated (Fig. 4C), indicating that Crk1 and Fuz7 physically associate in U. maydis cells.

The C-terminal domain of Crk1 is important for function

When compared with different fungal MAPK, the sequence similarities of Crk1 were restricted to the N-terminal half, where the catalytic domain is located (Supplementary Fig. 1). The long (>700 amino acids) C-terminal region does not display any similarities with databank entries. Since such a long C-terminal region might provide binding sites for other proteins, localization signals, or sites for post-translational modifications, we investigated whether the C-terminal half of Crk1 has any catalytic or regulatory function. To this end, a Crk1 derivative lacking the C-terminal half of the protein, Crk1ΔCt (Fig. 5A), was expressed in cells lacking endogenous Crk1. We found that such cells were partially active in mating assays (Fig. 5B), while they were unable to induce the hyperpolarized response (Fig. 5C). The deletion of the C-terminal half of the protein did not affect the T-loop phosphorylation (Fig. 5D), nor did it abolish the ability to be coprecipitated with Fuz7 (Fig. 5E). Immunoprecipitated Crk1ΔCt protein was able to phosphorylate MBP, and displayed autophosphorylation activity in an in vitro kinase assay, although less efficiently than full-length protein (Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

The C-terminal domain of Crk1 is required for in vivo activity. (A) Scheme of the crk1 and the crk1ΔCt alleles fused to myc epitope under the control of Pcrg1. (B) The C-terminal domain is partially dispensable for mating. FB1, UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), and UME66 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1ΔCt-myc) cells were cospotted with FB2 cells in charcoal-complete medium plates with glucose (CMD charcoal) or arabinose (CMA charcoal) as carbon source. (C) The C-terminal domain is required for Crk1-mediated hyperpolarized growth. UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), and UME66 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1ΔCtmyc) cells were incubated in CMD and CMA for 6 h. Bar, 10 μm. (D) The C-terminal domain of Crk1 does not affect the T-loop phosphorylation. Extracts were prepared from UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc) UME66 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1ΔCt-myc) cells and analyzed as described in Figure 2. (E) Crk1ΔCt and Fuz7 coprecipitate. Cultures of FB1, UME66 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1ΔCt-myc), UMS19 (FB1 fuz7-VSV), and UMS21 (FB1 fuz7-VSV Pcrg1:crk1ΔCt-myc) strains grown in CMA until OD600 of 0.5 were used to prepare whole-cell extracts (WCE). Immunoprecipitants obtained with anti-myc and anti-Fuz7 were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-VSV-peroxidase and anti-myc-peroxidase antibodies.

These results ascribe the catalytic activity to the N-terminal domain of Crk1, while stressing the importance of the long C-terminal end for the morphogenetic roles.

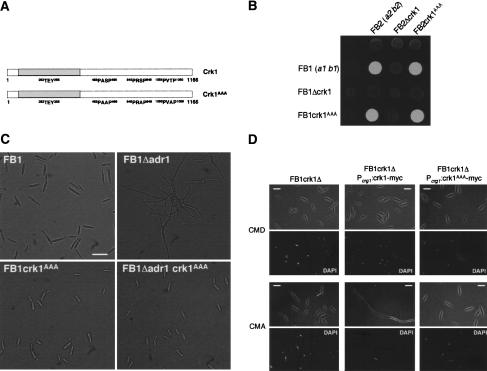

Putative MAPK phosphorylation sites in the C-terminal part of Crk1 are required for the morphogenetic role of Crk1

In its long C-terminal tail, the Crk1 protein contains three sequence motifs fitting the consensus L/PXS/TP of MAP kinase sites (Clark-Lewis et al. 1991; Fig. 6A). To elucidate whether these sites are functionally important for Crk1 in vivo activity, we changed, in the respective consensus sites, the serine or threonine residues at position 3 to alanine, and we exchanged the crk1 endogenous locus with the mutant crk1AAA allele. We found that elimination of the putative MAP kinase sites did not affect the mating ability (Fig. 6B). However, this mutant allele was able to suppress the filamentous phenotype of a strain lacking adr1 (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the putative MAPK sites are required for filamentation in U. maydis. Supporting this view, we found that the overexpression of Crk1AAA protein was unable to trigger polarized growth (Fig. 6D). Additionally, we observed that the mutation of the MAPK consensus sites did not affect the levels of T-loop phosphorylation of Crk1 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

The MAPK consensus sites of Crk1 are required for in vivo activity. (A) Scheme of crk1 as well as crk1AAA alelles. The MAPK consensus sequences are shown. (B) The MAPK consensus sites are dispensable for mating. FB1, FB2, UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UMP14 (FB2 Δcrk1), UMS13 (FB1 crk1AAA), and UMS15 (FB2 crk1AAA) cells were cospotted in charcoal-containing PD plates. (C) The MAPK consensus sites are required for filamentation induced by defects in cAMP pathway. FB1, SONU24 (FB1 Δadr1), UMS13 (FB1 crk1AAA), and UMS14 (FB1 Δadr1 crk1AAA) were incubated in liquid YPD medium until exponential growth. Bar, 20 μm. (D) The MAPK sites are required for Crk1-mediated hyperpolarized growth. UMP12 (FB1 Δcrk1), UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), and UMS12 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AAA-myc) cells were incubated in CMD and CMA for 6 h. Bar, 10 μm.

The MAPK Kpp2 is required for Crk1 activity

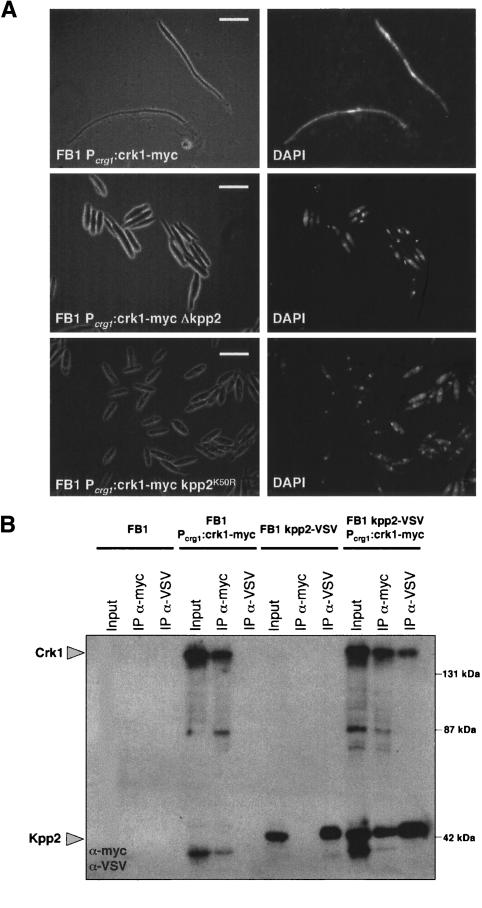

The elimination of the putative MAPK sites affected the function of Crk1 in filamentation. Since the Kpp2/Ubc3 MAPK is required for filamentation in U. maydis (Mayorga and Gold 1999; Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003), we analyzed the ability of high levels of Crk1 to induce the hyperpolarized growth in cells deficient in Kpp2 protein, and we found that this response was severely attenuated (Fig. 7A). To ascribe the requirement of Kpp2 to its catalytic activity, we expressed Crk1 in U. maydis cells carrying the kpp2K50R allele that encodes a kinase-dead mutant protein. We observed that in these mutant cells, the response was totally abolished (Fig. 7A). The differences observed between the null allele and the catalytically inactive allele suggest that in the absence of Kpp2, other proteins, most likely another MAPK, could substitute Kpp2 as has been demonstrated in other systems as well as in U. maydis (Breitkreutz et al. 2001; Brachmann et al. 2003). We also analyzed the ability of Crk1 and Kpp2 to associate. Lysates from U. maydis cells expressing Crk1 and Kpp2 as myc- and VSV-tagged proteins, respectively, were used to obtain immunoprecipitants using anti-myc (directed against Crk1) or anti-VSV (directed against Kpp2) antibodies, and the presence of Kpp2 or Crk1, respectively, was analyzed. We detected association of Kpp2 with Crk1 (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the Kpp2 requirement in filamentation involves physical interaction with Crk1, rather than an indirect mechanism.

Figure 7.

The Kpp2 MAPK is required for Crk1-mediated hyperpolarized growth. (A) UME61 (FB1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc), UME64 (FB1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc Δkpp2), and UMS17 (FB1 Pcrg1:crk1-myc kpp2K50R) cells were incubated in CM-arabinose for 6 h. (Right) DAPI staining of the same cell field. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Crk1 and Kpp2 associate. Cultures of FB1, UME61 (FB1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc), UMS22 (FB1 kpp2-VSV), and UMS23 (FB1 kpp2-VSV Pcrg1:crk1-myc) strains grown in CMA until OD600 of 0.5 were used to prepare whole-cell extracts (WCE). Immunoprecipitants obtained with anti-myc and anti-VSV were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-VSV-peroxidase and anti-myc-peroxidase antibodies.

Crk1 is required for the expression of genes in the a locus

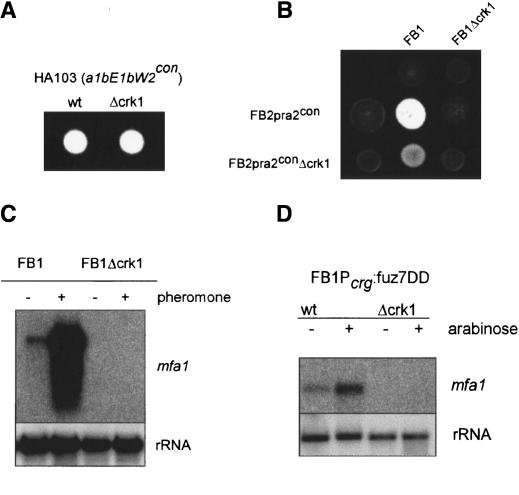

The interactions between Crk1 and components of the MAPK pathway controlling mating prompted a more extensive analysis of the roles Crk1 during mating. Filament formation, a post-fusion process, depends on the presence of compatible b proteins. We found that the mating and virulence defects of Δcrk1 cells can be completely overcome by expressing the compatible bE1 and bW2 genes from constitutive promoters (Fig. 8A; Table 1). These results limited the requirement of Crk1 to steps before the expression of the b mating-type locus. The expression of the b locus genes depends on the successful transmission of the pheromone signal. To determine whether Crk1 was required for the expression of the a mating-type locus genes (which include the pheromone and receptor encoding genes), or for the transmission of the pheromone signal itself, we overexpressed the pheromone receptor pra2 in FB2Δcrk1 cells. When such strains were crossed with a compatible wild-type strain, mating and pathogenicity were partially restored (Fig. 8B), strongly suggesting that the mating and virulence defects observed in Δcrk1 mutants could be due to insufficient expression of the a mating-type locus genes. To support this assertion, we investigated the crk1 requirement for the expression of the pheromone gene mfa1 by Northern analysis and observed that crk1 was essential for mfa1 expression in conditions of pheromone stimulation (Fig. 8C). To rule out defects in the perception of the pheromone signal (i.e., low level of pheromone receptor) we analyzed pheromone gene transcription in Δcrk1 cells harboring the fuz7DD allele, encoding a constitutively active MAPK kinase, and we found that even in these conditions, no pheromone expression was detectable (Fig. 8D). These results indicate that crk1 is required for the expression of mfa1 in response to pheromone stimulation.

Figure 8.

Crk1 is required for the induction of the sexual program. (A) Constitutive expression of b locus bypassed the requirement of Crk1 for infective filament formation. The strains indicated at top were spotted on charcoal-containing PD plates. HA103 carries b-compatible alleles expressed under a constitutive promoter. (B) Constitutive expression of the pheromone receptor gene partially suppresses the mating defect of Δcrk1 cells. The strains indicated at top, left were cospotted on charcoal-containing PD plates. (C) Crk1 is required for the trigging of pheromone expression after pheromone stimulation. The strains indicated at top were treated for 5 h with synthetic a2 pheromone dissolved in DMSO (+) or with the same volume of DMSO (-). RNA was isolated, and 10 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane. The blot was probed with mfa1 and with rRNA as loading control. (D) Requirement of Crk1 in pheromone induction is located downstream of Fuz7. The strains indicated at top were grown with glucose (-) or with arabinose (+) as a carbon source. RNA was isolated, and 10 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane. The blot was probed with mfa1 and with rRNA as loading control.

Crk1 is required for the expression of prf1

Expression of the a mating-type locus genes is dependent on the transcription factor Prf1, which itself is a target of the pheromone response cascade (Hartmann et al. 1996; Kaffarnik et al. 2003). Therefore, we analyzed the level of expression of the prf1 gene in Δcrk1 and wild-type cells after pheromone stimulation. We observed that prf1 mRNA was not detectable in mutant cells, while prf1 transcription was strongly up-regulated in wild-type cells (Fig. 9A). This result suggests that the absence of prf1 transcription might be the responsible for the mating and virulence defects observed in Δcrk1 cells. To support this interpretation, we expressed the prf1 gene under the control of the regulatable nar1 promoter (which is induced by the presence of NO3, and repressed by NH4) (Brachmann et al. 2001). We observed mfa1 expression in Δcrk1 when transcription of the prf1 gene was induced (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, SG200Δcrk1 cells carrying a constitutively expressed allele of prf1 were able to form filaments (Fig. 9C) and were fully virulent (Table 1). These results support the notion that Crk1 is required for the expression of prf1 gene.

Figure 9.

Crk1 controls the expression of prf1. (A) Crk1 is required for the trigging of prf1 expression after pheromone stimulation. The strains indicated at top were treated for 5 h with synthetic a2 pheromone dissolved in DMSO (+) or with the same volume of DMSO (-). RNA was isolated, and 10 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane. The blot was probed with mfa1 and with rRNA as loading control. (B) Heterologous expression of prf1 bypassed the requirement of Crk1 for pheromone gene expression. The strains indicated at top were grown in minimal medium with NH4 or NO3 as the nitrogen source. The prf1nar allele is transcribed in the presence of NO3 and is repressed in the presence of NH4. RNA was isolated, and 10 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane. The blot was probed with mfa1 and with rRNA as loading control. (C) Constitutive expression of prf1 bypassed the requirement of Crk1 for infective filament formation. The strains indicated were spotted on charcoal-containing PD plates. (D) The UAS confers crk1-dependent expression to a reporter gene. (Top) Scheme of the prf1 promoter regulatory region. Prf1-binding sites (PRE, triangles) as well as the UAS region (filled arrow) are indicated. The reporter gene constructs indicated at right, consisting of a minimal promoter (Pmfa1) fused to the green fluorescent protein (sgfp) gene with and without three 85-bp fragments containing the UAS cloned in tandem. The bent arrows represent the transcription initiation points of the reporter gene. (Bottom) Results of fluorimetric measurements using strains harboring the constructs described above, carrying deletions in the genes indicated below. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) were measured and normalized to optical density.

At the transcriptional level, prf1 expression depends on at least two different cis-acting promoter regions. The more proximal region consists of two pheromone response elements (PRE), where Prf1 binds and has an autoregulatory function (Hartmann et al. 1996). The second region, called upstream-activating sequence (UAS), is crucial for transcription of prf1, and responds to nutrient and cAMP signaling (Hartmann et al. 1999). Because the previously described connections between Crk1 and the cAMP/PKA pathway (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003), we wondered whether Crk1 controls prf1 transcription through the UAS. To address this question, we introduced in wild-type, Δcrk1, as well as Δprf1 strains, a UAS-dependent reporter gene, containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding gene behind a U. maydis minimal promoter fused to three copies of the UAS (Hartmann et al. 1999). As control, we used the GFP-minimal promoter fusion alone. We found that wild-type and Δprf1 cells carrying the UAS-containing reporter showed green fluorescence, while Δcrk1 cells did not (Fig. 9D). These results illustrated that Crk1 was required for UAS-dependent transcriptional activity of the prf1 promoter.

Discussion

Crk1, a new class of MAP kinase

Although Crk1 shares with other fungal MAPK only around 30% sequence similarity in the catalytic domain, Crk1 kinase appears to have features typical for MAP kinases. Crk1 contains the TXY dual phosphorylation motif that is a hallmark of MAP kinases (Kültz 1998), and in this study we have provided evidence that this motif is phosphorylated in vivo and that this phosphorylation is necessary for in vivo activity of Crk1. Our data also indicate that Fuz7 is the activating kinase involved in the phosphorylation of Crk1 T-loop. Fuz7 is required for in vivo activity, as well as for high levels of T-loop phosphorylation, and both proteins interact physically. As the downstream kinase substrates described so far for MAPKKs are MAPKs, we take these data collectively to support the inclusion of Crk1 as a new member of the MAPK family. However, we found that in a Δfuz7 strain, residual T-loop phosphorylation remained, indicating that phosphorylation of Crk1 may not exclusively depend on Fuz7. The U. maydis genome contains at least two additional MAPKK genes that code for homologs of Mkk1 and Pbs2 of S. cerevisiae, respectively. Whether these putative MAPKK are responsible for the residual phosphorylation of Crk1 will require additional investigation. We also found that activation of Crk1 promotes autophosphorylation. This feature has been noted in several MAP kinases, and in a few cases, like the S. cerevisiae MAPK Fus3, autophosphorylation has been shown to enhance the sensitivity to upstream signals (Brill et al. 1994).

Crk1 belongs to a widely conserved protein family with members found in all eukaryotic taxa analyzed. One of the members of this family, the S. cerevisiae Ime2 protein, must be dually phosphorylated at the TXY motif located in its activation loop for full activity (Schindler et al. 2003). The kinase responsible for this phosphorylation is currently unknown. The two Ime2/Crk1 orthologs in S. pombe, Mde3 and Pit1, as well as the mouse Mak protein carry TXY motifs; and this motif is also found in putative proteins showing high-sequence similarity with Ime2 and Crk1 from different organisms like Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Arabidopsis thaliana. We propose that all of these proteins constitute a new family of MAP kinases.

Function of Crk1 in sexual development

In this study, we have demonstrated that U. maydis cells defective in Crk1 are nonpathogenic. The pathogenic development in U. maydis is linked to sexual development. The avirulence phenotype was a consequence of the lack of expression of prf1, the factor responsible for the induction of the mating program. Transcriptional activation of the prf1 gene depends on at least two different activating promoter regions, a proximal region, containing two PRE elements that is recognized by Prf1 itself, and a distal one called UAS, that is recognized by unknown activators. The UAS region is essential and its deletion resulted in the absence of transcriptional activity (Hartmann et al. 1999). We found that Crk1 signals through the UAS region, explaining the requirement of this kinase for the expression of prf1. The UAS region accounts for the differential expression of prf1 in response to nutritional conditions; reporter gene analysis concluded that UAS-mediated activation was higher in minimal medium than in rich medium (Hartmann et al. 1999). Another signal that acts on the UAS is transmitted via the cAMP pathway; UAS activity decreases at high cAMP concentrations (Hartmann et al. 1999). This response mirrors the already described expression pattern of crk1, which is higher in minimal medium than in rich medium, and is repressed by high levels of PKA activity (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). A simple model in which Prf1 autoactivation is insufficient to maintain prf1 mRNA levels without the assistance from a parallel Crk1-dependent activation pathway could account for these results. The putative factor responsible for transcriptional activation via the UAS is currently unknown. A protein called Ncp1 has been identified that binds to the UAS, but appears not to be involved in the regulation of prf1 (Hartmann et al. 1999). In S. cerevisiae, the Crk1 homolog Ime2 induces the meiotic program by phosphorylating Ndt80, which in turn stimulates the transcription of genes required for the induction of the meiotic program. Phosphorylated Ndt80 also stimulates transcription of its own gene (Hepworth et al. 1998; Pak and Segall 2002; Sopko et al. 2002; Benjamin et al. 2003). Such a scenario, in which Crk1 modifies Prf1 post-transcriptionally, is unlikely in U. maydis, because the virulence defects of a Δcrk1 strain is completely suppressed by constitutive expression of prf1. We would therefore suggest the existence of a transcription regulator that acts via the UAS and is modified in its activity by Crk1. This factor is expected to have an essential role in regulating prf1 transcription during pathogenesis.

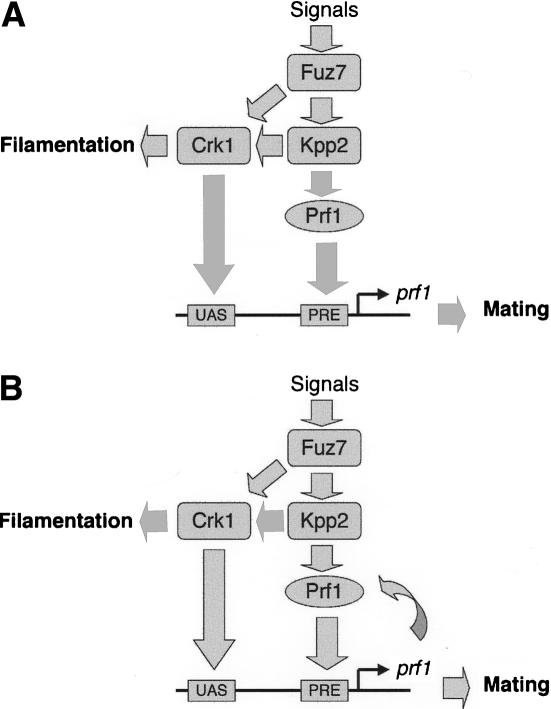

A working hypothesis for Crk1 function in signaling processes in U. maydis

Crk1 plays some role in morphogenesis in U. maydis. The overexpression of the crk1 gene induces hyperpolarized growth, and its deletion suppresses the filamentous growth associated with mutations in adr1, encoding the catalytic subunit of PKA (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). Our genetic results indicate that the long C-terminal tail of Crk1 appears to be required for these morphogenetic effects. Moreover, this function can be attributed to the consensus MAPK sites located in the C-terminal end. The morphogenetic role of Crk1 also seems to require the activity of the MAPK Kpp2/Ubc3. Overexpression of crk1 either in a Δkpp2 strain or in a strain carrying the kinase-dead allele kpp2K50R did not result in hyperpolarized growth. We also detected physical interaction between Crk1 and Kpp2. The simplest hypothesis is to assume that Kpp2 could directly phosphorylate the C-terminal end of Crk1. However, since we have not yet demonstrated phosphorylation of the consensus MAPK sites in the C-terminal end of Crk1 by Kpp2 kinase, we cannot rule out the involvement of additional proteins.

Crk1 has an important role as a regulator of sexual development via prf1 activation. Interestingly, the putative MAPK phosphorylation sites of Crk1 seem to be dispensable for this role. In contrast, Kpp2/Ubc3 is required both for sexual development and morphogenesis (Mayorga and Gold 1999; Müller et al. 1999). Therefore, we propose that the morphogenetic pathway separates from the sexual pathway at the level of the Kpp2 and Crk1, and that the putative differences in the phosphorylation status of the C-terminal end of Crk1 could trigger the distinct responses. Following this hypothetical model, conditions in which the C-terminal end is phosphorylated may direct the signal to hyperpolarized growth (Fig. 10A), while absence of C-terminal phosphorylation may direct Crk1 toward prf1 activation (Fig. 10B). Important questions remaining about this working model refer to the putative input signals and how the signal is discriminated. The MAPK module is required to respond to at least three different environmental cues, pH, presence of lipids, and presence of pheromone (Müller et al. 2003; Klose et al. 2004; Martinez-Espinoza et al. 2004) and the outcomes produced by each signal are different; pH and lipids induce filamentation, while pheromone signaling induces mating. One appealing possibility refers to differences by the magnitude, duration, or frequency of the signal as it has been proposed for signal identity in S. cerevisiae (Sabbagh et al. 2001).

Figure 10.

Proposed model for signaling processes involving Crk1 and the MAPK pathway. See text for a detailed discussion.

It will be interesting to elucidate whether such a scenario is unique to Crk1 or whether Crk1 homologs in other organisms use similar mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

For cloning purposes, the Escherichia coli K-12 derivative DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) was used. The U. maydis strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Strains were grown at 28°C in YPD (Kaiser et al. 1994), YEPS (modified after Tsukuda et al. 1988), potato dextrose broth (PD, Difco), complete medium (CM), or minimal medium (MM) (Holliday 1974). Induction conditions for crg1 and nar1 promoters were already described (Brachmann et al. 2001). All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were obtained from Sigma or Merck.

Table 2.

U. maydis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| FB1 | a1 b1 | Banuett and Herskowitz 1989 |

| FB2 | a2 b2 | Banuett and Herskowitz 1989 |

| FB1 Δfuz7 | a1 b1 Δfuz7 | Müller et al. 2003 |

| PM50 | a1 b1 kpp2K50R | Müller et al. 2003 |

| UMP12 | a1 b1 Δcrk1 | Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003 |

| UMP14 | a2 b2 Δcrk1 | Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003 |

| SG200 | a1 :: mfa2 bW2bE1 | Bölker et al. 1995 |

| SG200 Δcrk1 | a1 :: mfa2 bW2bE1 Δcrk1 | This study |

| SG200 prf1con | a1 :: mfa2 bW2bE1 prf1tef | This study |

| SG200 Δcrk1 prf1con | a1 :: mfa2 bW2bE1 prf1tef Δcrk1 | This study |

| HA103 | a1 bW2bE1con | Hartmann et al. 1996 |

| HA103 Δcrk1 | a1 bW2bE1con Δcrk1 | This study |

| FB2pra2con | mfa2 pra2tefb2 | Müller et al. 2003 |

| FB2pra2con Δcrk1 | mfa2 pra2tefb2 Δcrk1 | This study |

| FB1Perg:Fuz7DD | a1 b1 Pcrg:Fuz7DD | Müller et al. 2003 |

| FB1Perg:Fuz7DD Δcrk1 | a1 b1 Pcrg:Fuz7DD Δcrk1 | This study |

| SONU4 | a1 b1 Δkpp2 | Garrido and Pérez-Martin 2003 |

| SONU24 | a1 b1 Δadr1 | Garrido and Pérez-Martin 2003 |

| SONU27 | a1 b1 prf1nar | This study |

| UME41 | a1 b1 prf1nar Δcrk1 | This study |

| UME56 | a1 b1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B | This study |

| UME57 | a1 b1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B-UAS3 | This study |

| UME58 | a1 b1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B Δcrk1 | This study |

| UME59 | a1 b1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B-UAS3 Δcrk1 | This study |

| UME60 | a1 b1 Δfuz7 Δcrk1 | This study |

| UME61 | a1 b1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc | This study |

| UME62 | a1 b1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1AEF-myc | This study |

| UME63 | a1 b1 Δfuz7 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc | This study |

| UME64 | a1 b1 Δkpp2 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1-myc | This study |

| UME66 | a1 b1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1 ΔCt-myc | This study |

| UME67 | a1 b1 Δkpp2 Δcrk1 | This study |

| UME69 | a1 b1 a1 b1 Δcrk1 Pcrg:crk1K106R-myc | This study |

| UME70 | a1 b1 Δprf1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B | This study |

| UME71 | a1 b1 Δprf1 Pmfa1:sgfp-B-UAS3 | This study |

| UMS13 | a1 b1 crk1AAA | This study |

| UMS14 | a1 b1 Δadr1 crk1AAA | This study |

| UMS15 | a2 b2 crk1AAA | This study |

| UMS17 | a1 b1 Pcrg:crk1-myc kpp2K50R | This study |

| UMS19 | a1 b1 fuz7-VSV | This study |

| UMS20 | a1 b1 fuz7-VSV Pcrg:crk1-myc | This study |

| UMS21 | a1 b1 fuz7-VSV Pcrg:crk1ΔCt-myc | This study |

| UMS22 | a1 b1 kpp2-VSV | This study |

| UMS23 | a1 b1 kpp2-VSV Pcrg:crk1-myc | This study |

DNA and RNA procedures

Standard molecular techniques were followed (Sambrook et al. 1989). U. maydis DNA isolation and transformation was performed as previously described (Tsukuda et al. 1988). RNA isolation and Northern analysis was performed as described previously (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003). For mfa1 probe, a 0.67-kb EcoRV fragment was used as described previously (Bölker et al. 1992). For the prf1 probe, a 1.6-kb EcoRV fragment from pRF-6.0B was used as described previously (Hartmann et al. 1999). To standardize loading, we used a 5′-end-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to the U. maydis 18s rRNA (Bottin et al. 1996). Detection and quantification of the signals were performed with the help of a PhosphorImager and the suitable program.

Plasmid and plasmids constructions

Plasmids pGEM-T easy (Promega), and pBS-SK(-) (Stratagene) were used for cloning, subcloning, and sequencing of genomic fragments and fragments generated by PCR. Sequence analysis of fragments generated by PCR was performed with an automated sequencer (ABI 373A) and standard bioinformatic tools.

To construct the plasmids to express the different crk1 alleles tagged with three copies of the myc epitope, a general procedure was followed consisting firstly in the generation by PCR of a DNA fragment encompassing the respective allele. The resulting fragments were cloned into the plasmid pGNB-myc, which is a pGEX-2T (Pharmacia Biosciences) derivate that carries three copies of the myc epitope (J. Pérez-Martín, unpubl.) and allows the expression of the tagged fusion in bacteria. From the resulting plasmid (pGNB-crk1derivate), the crk1-myc fusion was excised as an NdeI-AflII fragment, and was cloned into the pRU11 plasmid (Brachmann et al. 2001) digested with NdeI and AflII restriction enzymes. The pRU11 plasmid is an integrative U. maydis vector that contains the crg1 promoter (Brachmann et al. 2001). The resulting plasmid (pRU11-crk1 derivate) was linearized after SspI digestion, and was integrated by homologous recombination in the ip locus. Integration of the plasmids into the corresponding loci was verified in each case by diagnostic PCR and subsequent Southern blot analysis.

The full-length wild-type crk1 gene was obtained after amplification of U. maydis genomic DNA with the primer pairs N-CRK1 (5′-CATATGCAAGCTGTCACCGCTTCGAGGCCC-3′)/CT-7 (5′-GCAATTGGCTTTGCGGCAATGGACCGGG-3′). The 3.5-kb fragment was used to construct the pGNB-Crk1 and pRU11-Crk1 plasmids.

The mutant crk1AEF allele was constructed by the assembly of two fragments carrying the T253A and Y255F mutations generated by PCR with the primer pairs N-CRK1/CRK1-F2 (5′-ACGCGTCGAGACGAATTCTGCGTAAGGTGGTTT-3′) and CT-7/CRK1-F2 (5′-AAACCACCTTACGCAGAATTCGTCTCGACGCGT-3′). The 3.5-kb fragment was used to construct the pGNBCrk1AEF and pRU11-Crk1AEF plasmids.

The mutant crk1K106R allele was constructed by the assembly of two fragments carrying the K106R mutation generated by PCR with the primer pairs N-CRK1/CRK1-KR2 (5′-GGGCTTTTTCATCTTCCGGATGGCGACAAGTCG-3′) and CT-7/CRK1-KR1 (5′-CGTCTTGTCGCCATCCGGAAGATGAAAAAGCCC-3′). The 3.5-kb fragment was used to construct the pGNB-Crk1KR and pRU11-Crk1KR plasmids.

The mutant crk1AAA allele was constructed in two steps. First, we constructed an allele crk1AA carrying two mutations by the assembly of three fragments carrying the S485A and S847A mutations generated by PCR with the primer pairs N-CRK1/C-CRK1-S1 (5′-ATCCTCTTGCATGGGCGCCGCGGGGGTTGTGCC-3′), N-CRK1-S1 (5′-GGCACAACCCCCGCGGCGCCCATGCAAGAGGAT-3′)/C-CRK1-S2 (5′-GGGTTGCTGGAGAGGCGCTCGAGGAAATTCGCC-3′) and CT-7/N-CRK1-S2 (5′-GGCGAATTTCCTCGAGCGCCTCTCCAGCAACCC-3′). The resulting 3.5-kb fragment was used as template to introduce the third mutation (T1058A). Two fragments generated by PCR with the primers N-CRK1/C-CRK1-T3 (5′3′), and CT-7/N-CRK1-T3 (5′3′) were assembled and cloned into the pGEM-T plasmid. This fragment was flanked by a carboxine resistance using the PCR-tagging technique described in Kamper (2004) to be exchanged with the endogenous crk1 locus. The same fragment was also used to construct the pRU11-Crk1AAA plasmid.

The mutant crk1ΔCt allele was obtained after amplification of U. maydis genomic DNA with the primer pairs N-CRK1/CRK1-2 (5′-GCAATTGGTCGGGCTGACGTAGCACG-3′). The 1.38-kb fragment was used to construct the pGNBCrk1ΔCt and pRU11-Crk1ΔCt plasmids.

The C terminus end-tagged versions of Fuz7 and Kpp2 were obtained by PCR amplification of U. maydis genomic DNA with the primers FUZ7TAG1 (5′-CGGGATCCTGCACGAGTGCAATTCGCC-3′)/FUZTAG2 (5′-CGCAATTGCTTCATCCCATCGGCCCAT-3′) and UBC3TAG1 (5′-CGGGATCCTCGACATTGTCAAGCCCGA-3′)/UBC3TAG2 (5′-CGGAATTCACGCATGATCTCGTTATAA-3′), respectively. The 0.8-kb fragments were cloned into pBS-VSV-HYG (J. Pérez-Martín, unpubl.), and the resulting plasmids (pBS-Fuz7VSV and pBSKpp2VSV) were digested with ClaI and EcoRI and transformed into U. maydis cells.

The reporter plasmids pmfa1-sgfpB and pB-UAS3 have already been described (Hartmann et al. 1999).

Protein procedures

U. maydis protein extracts, coimmunoprecipitation assays, and Western analysis were performed as described previously (García-Muse et al. 2004). Anti-PSTAIRE (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-myc 9E10, anti-myc-peroxidase, anti-VSV-peroxidase (Roche Diagnostics Gmb), anti-Fuz7 (Eurogentec custom-made antibodies raised against Fuz7 peptides KNGLDTEPNSGANYHC and EDDDSDADNNYTNEDL, partially purified), and anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Cell Signaling) antibodies were used in phosphate-buffered saline/0.1% TWEEN/10% dry milk. Anti-mouse-Ig-horseradish peroxidase and anti-rabbit-Ighorseradish peroxidase (Roche Diagnostics Gmb) were used as a secondary antibody at 1:10000 dilution. All Western analyses were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Renaissance, Perkin Elmer).

For the kinase reaction, protein precipitates were incubated at 28°C for 20 min in KB buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 15 mM Cl2Mg, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 50 μM ATP, 160 μCi/mL [γ-32P]ATP, 0.5 mg/mL Myelin Basic Protein [MBP]). The reaction was terminated by adding 5 μL of 5× Laemli buffer, and then boiled for 3 min and loaded onto a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Phosphorylated MBP was visualized by autoradiography.

Fluorimetric measurements

Cultures of the respective strains in complete medium were grown until OD600 of 0.5 and 0.5 mL were transferred to quartz cuvettes and fluorescence was measured in a fluorometer Hitachi F-2500. GFP fluorescence was measured at a wavelength of 485 nm for excitation and 520 nm for emission, with a bandwidth of 7.5 nm in both cases. Optical density was measured as absorbance at 600 nm. Fluorescence was normalized to OD600. Two cultures for each strain were measured in triplicate.

Microscopic observations

For microscopic observation, we used a Leika DMLB microscope with phase contrast. Frames were taken with a Leika 100 camera. Epifluorescence was observed using standard DAPI filter sets. Image processing was performed with Photoshop (Adobe). Nuclear staining was done using DAPI staining as described previously (Garrido and Pérez-Martín 2003).

Mating, pheromone stimulation, and plant infection

To test for mating, compatible strains were cospotted on charcoal-containing PD plates (Holliday 1974), which were sealed with parafilm and incubated at 21°C for 48 h. Pheromone stimulation assays were performed after Müller et al. (2003). Plant infections were performed as described previously (Gillissen et al. 1992) with the maize cultivar Early Golden Bantam (Old Seeds).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Perez-Martin lab for materials. We thank Professor Maria Molina (UCM, Madrid) for advice on Western blots. Sonia Castillo-Lluva is supported by a FPI fellowship. Work in Madrid was supported by grant BIO2002-03503 from MCyT and grant 07B/0040/2002 from CAM. Work in Marburg was supported through SFB369 and by Bayer Crop-Science.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.314904.

References

- Abe H. and Shimoda, C. 2000. Autoregulated expression of Schizosaccharomyces pombe meiosis-specific transcription factor Mei-4 and a genome-wide search for its target genes. Genetics 154: 1497-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews D.L., Egan, J.D., Mayorga, M.E., and Gold, S.E. 2000. The Ustilago maydis ubc4 and ubc5 genes encode members of a MAP kinase cascade required for filamentous growth. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13: 781-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuett F. and Herskowitz, I. 1989. Different a alleles are necessary for maintenance of filamentous growth but not for meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86: 5878-5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1994. Identification of fuz7, a Ustilago maydis MEK/MAPKK homolog required for a-locus-dependent and -independent steps in the fungal life cycle. Genes & Dev. 8: 1367-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin K.R., Zhang, C., Shokat, K.M., and Herskowitz, I. 2003. Control of landmark events in meiosis by the CDK Cdc28 and the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2. Genes & Dev. 17: 1524-1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bölker M., Urban, M., and Kahmann, R. 1992. The a mating type locus of U. maydis specifies cell signaling components. Cell 68: 441-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bölker M., Genin, S., Lehmler, C., and Kahmann, R. 1995. Genetic regulation of mating and dimorphism in Ustilago maydis. Can. J. Bot. 73: 320-325. [Google Scholar]

- Bottin A., Kämper, J., and Kahmann, R. 1996. Isolation of a carbon source-regulated gene from Ustilago maydis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253: 342-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann A., Weinzierl, G., Kämper, J., and Kahmann, R. 2001. The bW/bE heterodimer regulates a distinct set of genes in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 42: 1047-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann A., Schirawski, J., Müller, P. and Kahmann, R. 2003. An unusual MAP kinase is required for efficient penetration of the plant surface by Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 22: 2199-2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz A., Boucher, L., and Tyers, M. 2001. MAPK specificity in the yeast pheromone response independent of transcriptional activation. Curr. Biol. 11: 1266-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill J.A., Elion, E.A., and Fink, G.R. 1994. A role for autophosphorylation revealed by activated alleles of FUS3, the yeast MAP kinase homolog. Mol. Biol. Cell 5: 297-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano E. and Mahadevan, L.C. 1995. Parallel signal processing among mammalian MAPKs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20: 117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Lewis I., Sanghera, J.S., and Pelech, S.L. 1991. Definition of a consensus sequence for peptide substrate recognition by p44mpk, the meiosis-activated myelin basic protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 15180-15184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Muse T., Steinberg, G., and Pérez-Martín, J. 2004. Characterization of B-type cyclins in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis: Roles in morphogenesis and pathogenicity. J. Cell Sci. 117: 487-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido E. and Pérez-Martín, J. 2003. The crk1 gene encodes an Ime2-related protein that is required for morphogenesis in the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 47: 729-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillissen B., Bergemann, J., Sandmann, C., Schrör, B., Bölker, M., and Kahmann, R. 1992. A two-component regulatory system for self/non-self recognition in Ustilago maydis. Cell 68: 647-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold S.E., Duncan, G., Barrett, K., and Kronstad, J. 1994. cAMP regulates morphogenesis in the fungal pathogen Ustilago maydis. Genes & Dev. 8: 2805-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann H.A., Kahmann, R., and Bölker, M. 1996. The pheromone response factor coordinates filamentous growth and pathogenic development in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 15: 1632-1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann H.A., Krüger, J., Lottspeich, F., and Kahmann, R. 1999. Environmental signals controlling sexual development of the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis through the transcriptional regulator Prf1. Plant Cell 11: 1293-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth S.R., Friesen, H., and Segall, J. 1998. NDT80 and the meiotic recombination checkpoint regulate expression of middle sporulation-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 5750-5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz I. 1995. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: For mating and for more. Cell 80: 187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R. 1974. Ustilago maydis. In Handbook of genetics Vol.1, (ed. R.C. King), pp. 575-595. Plenum Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Jinno A., Tanaka, K., Matsushime, H., Haneji, T., and Shibuya, M. 1993. Testis-specific mak protein kinase is expressed specifically in the meiotic phase in spermatogenesis and is associated with a 210-kilodalton cellular phosphoprotein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 4146-4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffarnik F., Müller, P., Leibungut, M., Kahmann, R., and Feldbrüdgge, M. 2003. PKA and MAPK phosphorylation of Prf1 allows promoter discrimination in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 22: 5817-5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C., Michaelis, S., and Mitchell, A. 1994. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Kamper J. 2004. A PCR-based system for highly efficient generation of gene replacement mutants in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271: 103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlatchev A., Xu, S., English, J., Wu, P., Schaefer, E., and Cobb, M.H. 1997. Reconstitution of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation cascades in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 11057-11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose J., Moniz de Sá, M., and Kronstad, J.W. 2004. Lipid-induced filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 52: 823-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kültz D. 1998. Phylogenetic and functional classification of mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases. J. Mol. Evol. 46: 571-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani H.D. and Fink, G.R. 1998. The control of filamentous differentiation and virulence in fungi. Trends Cell. Biol. 8: 348-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Espinoza A.D., Ruiz-Herrera, J., Leon-Ramirez, C.G., and Gold, S.E. 2004. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling pathways modulate the pH-induced yeast-to-mycelium dimorphic transition in the corn smut fungus ustilago maydis. Curr. Microbiol. 49: 274-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga M.E. and Gold, S.E. 1998. Characterization and molecular genetic complementation of mutants affecting dimorphism in the fungus Ustilago maydis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 24: 364-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1999. A MAP kinase encoded by the ubc3 gene of Ustilago maydis is required for filamentous growth and full virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 34: 485-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A.P. 1994. Control of meiotic gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 58: 56-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Aichinger, C., Feldbrugge, M., and Kahmann, R. 1999. The MAP kinase kpp2 regulates mating and pathogenic development in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 34: 1007-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Weinzierl, G., Brachmann, A., Feldbrugge, M., and Kahmann, R. 2003. Mating and pathogenic development of the smut fungus Ustilago maydis are regulated by one mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Euk. Cell 2: 1187-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R.L. and Fink, G.R. 1994. Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: Mating and invasive growth. Genes & Dev. 8: 2974-2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak J. and Segall, J. 2002. Regulation of the premiddle and middle phases of expression of the NDT80 gene during sporulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 6417-6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh W., Flatauter, L.J., Bardwell, A.J., and Bardwell, L. 2001. Specificity of MAP kinase signaling in yeast differentiation involves transient versus sustained MAPK activation. Mol. Cell 8: 683-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. 1989. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Schindler K., Benjamin, K.R., Martin, A., Boglioli, A., Herrskowitz, I., and Winter, E. 2003. The Cdk-activating kinase Cak1p promotes meiotic S phase through Ime2p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 8718-8728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y., Satoh, H., Takeda, N., Fukuda, M., Chiba, E., Kato, T., Kuramochi, T., and Araki, Y. 2002. A testicular germ cell-associated serine-threonine kinase, MAK, is dispensable for sperm formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 3276-3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopko R., Raithatha, S., and Stuart, D. 2002. Phosphorylation and maximalactivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80 is dependent on Ime2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 7024-7040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuda T., Carleton, S., Fotheringham, S., and Holloman, W.K. 1988. Isolation and characterization of an autonomously replicating sequence from Ustilago maydis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 3703-3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh A.J. and Davis, R.J. 1998. Structural organization of MAP-kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in yeast and mammals. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23: 481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmann C., Gibson, S., Jarpe, M.B., and Johnson, G.L. 1999. Mitogen-activated protein kinase: Conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol. Rev. 79: 143-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.R. 2000. MAP kinases in fungal pathogens. Fungal Genet. Biol. 31: 137-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsevskaya-Carter T. and Cooper, J.A. 1997. Spm1, a stress-activated MAP kinase that regulates morphogenesis in S. pombe. EMBO J. 16: 1318-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]