Abstract

Background

The lifetime prevalence of Social Phobia (SP) in European countries other than Italy has been estimated to range from 3.5% to 16.0%. The aim of this study was to assess the frequency of SP in Sardinia (Italy) in order to verify the evidence of a lower frequency of SP in Italy observed in previous studies (from 1.0% to 3.1%).

Methods

A randomised cross sample of 1040 subjects, living in Cagliari, in rural areas, and in a mining district in Sardinia were interviewed using a Simplified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDIS). Diagnoses were made according to the 10th International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

Results

Lifetime prevalence of SP was 2.2% (males: 1.5%, females: 2.8%) whereas 6-month prevalence resulted in 1.5% (males: 0.9%, females: 2.1%). Mean age at onset was 16.2 ± 9.3 years. A statistically significant association was found with Depressive Episode, Dysthymia and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Conclusions

The study is consistent with findings reported in several previous studies of a lower prevalence of SP in Italy. Furthermore, the results confirm the fact that SP, due to its early onset, might constitute an ideal target for early treatment aimed at preventing both the accumulation of social disabilities and impairments caused by anxiety and avoidance behaviour, as well as the onset of more serious, associated complications in later stages of the illness.

Background

Several epidemiological studies have attempted to describe the prevalence, socio-demographic characteristics, comorbidity, and severity of clinical manifestations of Social Phobia (SP). Quality of life and functional status of affected individuals have also been investigated [1]. Lifetime prevalence of SP in European societies other than Italy ranges from 3.5% to 16.0% [2]. As discussed in several excellent review papers, these rate differences were partly attributed to probable genetic or cultural factors [3]. Furthermore, major methodological differences (type of diagnostic criteria used, assessment tools, age of the sample) affecting the estimates have been demonstrated [1].

This study, part of an extended epidemiological investigation "Health in Sardinia," aimed to assess the prevalence rates of SP in Sardinia (Italy) in order to confirm the evidence of low SP prevalence rates ranging from 1.0% to 3.1% observed in previous research projects in Italy [4-6]. The study also intended to evaluate the treatments and to verify the comorbid psychiatric disorders in the identified people with Social Phobia.

Methods

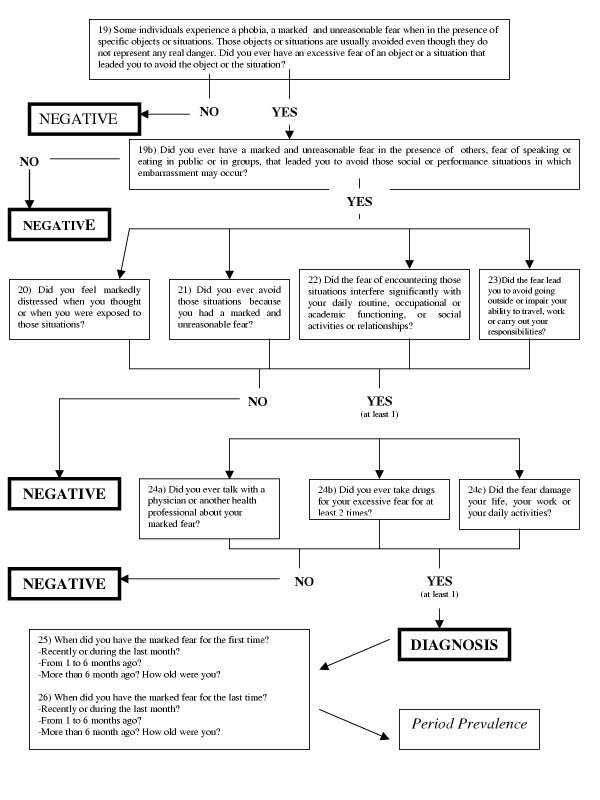

The sample, which had already been examined and described in greater detail in a previously published study [7], consisted of 1040 subjects recruited throughout the island of Sardinia, Italy. 393 subjects came from the city of Cagliari, 344 from rural areas, and 303 from an industrial mining district, thus representing fairly well all socio-economic strata present on the island. The age distribution of the sample is shown in table 1, with age range from 18 to 89 years. 79.2% out of a total of 1313 subjects approached, agreed to take part in the study, 12.5% refused to participate, and 8.3% could not be traced; the final sample did not differ respect to the population of origin with reference to the variables applied in stratification (Table 1). All subjects were interviewed "face to face" by trained physicians using a Simplified version of Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [8], hence the acronym CIDI "Simplified" (CIDIS) [9,10]. The version used in this study had been translated into Italian and back-translated into the original French language under blind conditions respect to the first translation, by a bilingual researcher; approval of the final version was obtained from the original authors [11]. The CIDI structured interview in its various versions currently represents the most widely used diagnostic tool in psychiatric epidemiological studies conducted on the general population [12]. The CIDIS is a highly structured tool made up of 5 sections which investigate respectively: Somatoform Disorders and General Medical Conditions, Anxiety Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Substance-Related Disorders (Alcohol-Related Disorders and Substance-Related Disorders) and Eating Disorders. The computer elaboration of data obtained through application of the CIDIS enables calculation of both "lifetime prevalence" and, for the preceding six months, a series of psychiatric disorders (those more frequently observed in the general population) according to the ICD-10 diagnostic system [13]. This interview moreover enhances identification of both the type of therapist referred to and treatment already used by each patient for his or her specific problem and definition of degree of impact of the problem on the subject's daily routine. An ad hoc computer algorithm ascertained the presence of the disorders according to ICD-10 criteria [13], both in the past six months and in the lifetime. The items of the CIDIS concerning Social Phobia and the related algorithm is reported in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of subdivision according to age, sex, and marital status of the sample.

| N (1040) | |

| MALES | 461 (44.3%) |

| FEMALES | 579 (55.7%) |

| AGE 18–24 | 146 (14.0%) |

| AGE 25–44 | 353 (33.9%) |

| AGE 45–64 | 310 (29.8%) |

| AGE >64 | 231 (22.2%) |

| UNMARRIED | 370 (35.6%) |

| MARRIED | 571 (54.9%) |

| WIDOWED/SEPARATED/DIVORCED | 99 (9.5%) |

Figure 1.

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview Simplified (CIDIS) [9, 10] algorithm for the diagnosis of Social Phobia.

Results

Estimates of lifetime SP prevalence of 2.2% were found (males: 1.5%, females: 2.8%), with no statistically significant difference between the sexes (χ2 = 1.2, 1DF, P = 0.25). 6-month prevalence rates were lower (total: 1.5%, males: 0.9%; females: 1%; no significant difference between the sexes, χ2 = 1.6, 1DF, P = 0.13). Table 2 compares results obtained in this study with those of the major research projects carried out in Europe and the USA [4,5,14-23]. Table 3 illustrates the lifetime prevalence according to age and sex, and Table 4 shows the 6-month prevalence according to age and sex. An increased frequency of SP among the younger age groups was observed, although distribution in males resulted as being less homogeneous. In no case statistical significance was reached. Lifetime prevalence rates of SP respect to marital status of subjects studied were as follows: 3.0% among the unmarried; 1.2% among married subjects; and 3.5% among the divorced, separated and widowed (χ2 = 5.8, 1DF, P = 0.06). Mean age at onset was 16.2 ± 9.3 years.

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence of Social Phobia in the general population of Europe and USA.

| Country | Reference | Diagnostic criteria | N | Male | Female | Total |

| Italy | Faravelli et al., 1989 [4] | DSM-III-R | 1110 | 1.0 | ||

| Switzerland | Wacker et al., 1992 [16] | DSM-III-R | 470 | 16.0 | ||

| ICD-10 | 9.6 | |||||

| ECA (USA) | Schneier et al., 1992 [15] | DIS | 18571 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 2.4 |

| Iceland | Lindal and Stefansson, 1993 [32] | DSM-III | 862 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| Switzerland | Degonda and Angst, 1993 [21] | DSM-III | 591 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 4.4 |

| NCS (USA) | Kessler et al., 1994 [17] | CIDI | 8098 | 11.1 | 15.5 | 13.3 |

| France | Lepine and Lellouch, 1995 [19] | 2.1 | 5.4 | 4.1 | ||

| Germany | Wittchen et al., 1998 [23] | DSM-IV | 3021 | 2.2 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| Italy | Carta and Rudas, 1998 [6] | CIDI | 783 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 3.1 |

| Spain | Arillo et al., 1998 [cited in 33] | DIS | 237 | 8.9 | ||

| Netherlands | Bijl et al., 1998 [20] | DSM-III-R | 7076 | 5.9 | 9.7 | 7.8 |

| France | Lépine and Pélissolo, 1999 [22] | DSM-IV | 7.3 | |||

| Italy | Faravelli et al., 2000 [5] | FPI/CIDI | 2355 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 3.1 |

| Italy | Carta et al., 2002 [7] | CIDI | 1040 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 |

Table 3.

Lifetime prevalence N (%) of Social Phobia according to age and sex.

| Age | Male | OR | Female | OR | Total | OR |

| <25 | 1 (1.3) | 0.9 | 4 (5.0) | 2.3 | 5 (3.4) | 1.7 |

| 25–44 | 4 (2.5) | 2.5 | 4 (2.1) | 0.7 | 8 (2.2) | 1.1 |

| 45–64 | 1 (0.7) | 0.4 | 4 (2.4) | 0.8 | 5 (1.6) | 0.6 |

| >65 | 1 (1.1) | 0.7 | 4 (2.8) | 1.1 | 5 (2.2) | 0.9 |

Male according to age χ2 with Yathes correction = 1.6, 3 df, p = 0.89; female according to age χ2 with Yathes correction = 2.2, 3 df, p < 0.71; total sample according to age χ2 with Yathes correction = 1.8, 3 df, p = 0.82

Table 4.

Six month prevalence N (%) of Social Phobia according to age and sex.

| Age | Male | OR | Female | OR | Total | OR |

| <25 | 1 (1.5) | 1.8 | 3 (3.7) | 2.0 | 4 (2.7) | 2.1 |

| 25–44 | 1 (0.6) | 0.6 | 3 (0.7) | 0.5 | 4 (1.1) | 0.6 |

| 45–64 | 1 (0.7) | 0.7 | 2 (1.1) | 0.5 | 3 (0.9) | 0.5 |

| >65 | 1 (1.1) | 1.4 | 4 (2.8) | 1.4 | 5 (2.1) | 1.6 |

Male according to age χ2 = 0.6, 3 df, p = 0.98; female according to age χ2 with Yathes correction = 3.4, 3 df, p = 0.44; total sample according to age χ2 with Yathes correction = 3.4, 3 df, p = 0.44

During the week prior to the study, 8 (50.0%) out of the 16 subjects who had been diagnosed with SP over the past six months had been taking low doses of anxiolytics (less than the equivalent of 2 mg of Lorazepam). 3 (18.7%) were on antidepressants, one of whom (6.2%) at non-therapeutic doses, and 1 subject (6.2%) was undergoing cognitive behavioural psychotherapy. The remaining 6 subjects (37.5%) were not on any treatment.

Six out of the 10 treated subjects (60%) were being supervised by their general practitioners (GP), 1 (10%) by a neurologist and 2 (20%) by psychiatrists. All subjects presented some degree of comorbidity with Depressive Episodes (DE), Panic Attack Disorder (PAD), and agoraphobia (AP). Only 1 subject (10%) was undergoing cognitive behavioural therapy with a psychologist/psychotherapist.

Table 5 illustrates the rate of comorbidity with major psychiatric disorders observed in the general population, as well as the degree (OR) of associated disorders observed with regard to frequency reported for the latter in populations not affected by SP. A statistically significant difference was revealed for association with DE, Dysthymia (DD), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). In spite of their increased frequency among patients affected by SP, disorders such as PAD and Specific Phobia do not represent a statistically significant association. The mean age at onset of comorbid DE was 6.5 ± 6.6 years subsequent to onset of SP, whereas GAD was manifested at a mean of 4.3 ± 7.8 years later.

Table 5.

Lifetime comorbidity of Social Phobia.

| N (%) | OR | χ2 | |

| Depressive Episode (DE) | 9 (39.1) | 4.3 | 11.1* |

| Dysthymia (DD) | 5 (21.7) | 7.1 | 14.1* |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | 10 (43.4) | 6.5 | 20.9* |

| Panic Attack Disorder (PAD) | 2 (8.7) | 3.3 | 1.1 |

| Specific Phobia | 1 (4.3) | 8.6 | 1.6 |

*p < 0.001

Discussion

Several epidemiological studies carried out in Europe (Switzerland [16,21], France [19,22], Germany [23]) and in the USA [15,17], recently reviewed by Furmark [2], suggest that SP is one of the more frequently observed anxiety disorders in the general population in Western countries. However, frequency rates reported in the various studies differ from country to country and according to time and evaluation methods used. Indeed, the two American studies [15,17] carried out at an interval of approximately 15 years, illustrate distinctly contrasting results, and it is hard to establish what factors really determine variance in findings.

The present study is consistent with the tendency towards rather low lifetime prevalence rates of SP observed in other Italian research projects. If we take into account only those European researches that adopted ICD-10 diagnosis, our results seem to indicate a lower frequency than a study carried out in Formentera, Spain (lifetime prevalence of 2.8% against 8.9% in females [cited in [33]]) and Basel, Switzerland (lifetime prevalence in the total sample 2.2 against 9.6% [16]). However, lower frequencies emerged also in Italian surveys conducted using different methods [5,7]. The Italian studies were carried out over a considerable period of time and in two distinct areas: the Florence area [4,5] and Sardinia [[6], the present study]. It is therefore quite likely that the lower frequencies observed may be the result of an effectively reduced vulnerability of Italians to SP. The results of this study can indeed be assumed as being influenced by several cultural variables – the genetic diversity of the two populations examined, as well as the considerable genetic variance of the Sardinian population respect to other European populations [24,25].

Findings for six-month prevalence show lower frequencies than those evidenced in the recent studies: 1.5% against 4.0% in Iceland [26] and against 4.0% in Munich [14]. Our rates are lower than E.C.A. findings: 2.7% in Duke [27] and 2.2% in Baltimore, New Haven, and Saint Louis [28]. The 6-month prevalence rates obtained in Sardinia are similar only to data reported for Edmonton (1.2%) from a survey carried out more than 15 years ago [29] and published in 1994 [30]. However, the prevalence data emerging from this study further justify the considerable interest shown in this disorder from both a medical and a social point of view. This research confirms the fact that onset of the illness occurs primarily during childhood and adolescence [31], thus underlining the suitability of the condition as a candidate for early treatment aimed at preventing both the slow accumulation of social disabilities and impairment caused by anxiety and by avoidance behaviour, as well as the onset of more serious complications (e.g., DE or GAD), which may be manifested many years after onset of SP. Indeed, subjects affected by social phobia presented a high risk of comorbidity with both the latter disorders and DD [1] .

It should be underlined that 60% of subjects undergoing treatment (not all affected subjects) chose their general practitioner (GP). This view is corroborated by the fact that those patients treated by a psychiatrist invariably presented comorbidity with DE, PAD, and AP, thereby representing the more severely affected from a psychopathological point of view. Overall however, the low rate of patients with SP treated with first line-treatments is alarmingly low.

In the future, serious attempts should be made to improve the GPs' abilities to recognise SP in order to prevent the use of inappropriate treatments, such as insufficient doses of benzodiazepines, which may be linked to the physician's incorrect diagnosing of the disorder. Due to the fact that subjects affected by SP most frequently refer to their GP, the importance of preventing SP as opposed to other types of disorders, as well as the markedly incapacitating nature of SP reinforce this necessity for a better training of GPs.

It is however mandatory to briefly acknowledge some potential limitations of this study. First, the number of cases and the sample size is too small to allow firm conclusions to be drawn concerning the true rate and the degree to which they might actually differ from previous studies with higher estimates. Secondly, differences in the assessment strategy might have resulted in a diminished comparability.

Conclusions

The study is consistent with findings reported in several previous studies of a lower prevalence of Social Phobia in Italy and confirms the fact that onset of the illness occurs primarily during childhood and adolescence. Furthermore, the results confirm the fact that SP, due to its early onset, might constitute an ideal target for early treatment aimed at preventing both the accumulation of social disabilities and impairments caused by anxiety and avoidance behaviour, as well as the onset of more serious, associated complications in later stages of the illness, or many years after onset of SP.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MGC participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. UHW participated in the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MCH, MC, BC, LDO, MAR conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Mauro Giovanni Carta, Email: mgcarta@tiscali.it.

Maria Carolina Hardoy, Email: mgcarta@tiscali.it.

Mariangela Cadeddu, Email: mgcarta@tiscali.it.

Bernardo Carpiniello, Email: bcarpini@iol.it.

Liliana Dell'Osso, Email: ldelloss@psico.med.unipi.it.

Mario Antonio Reda, Email: Reda@unisi.it.

Hans-Ulrich Wittchen, Email: wittchen@psychologie.tu-dresden.de.

References

- Wittchen HU. Social phobia: new perspectives on a neglected mental disorder. Psychiatric Networks. 2000;3:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Furmark T. Social Phobia: overview of community surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:84–93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Fehm Epidemiology and natural course of social fears and social phobia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:4–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Guerrini Degl'Innocenti B, Giardinelli L. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in Florence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79:308–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Zucchi T, Viviani B, Salmoria R, Perone A, Paionni A, Scarpato A, Vigliaturo D, Rossi S, D'adamo D, Bartolozzi D, Cecchi C, Abrardi L. Epidemiology of social phobia: a clinical approach. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta MG, Rudas N. Psichiatria transculturale. Cagliari: CUEC; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carta MG, Kovess V, Hardoy MC, Morosini PL, Murgia S, Carpiniello B. Psychiatric disorders in Sardinian immmigrants in Paris: a comparison with Parisians and Sardinians resident in Sardinia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37:112–117. doi: 10.1007/s001270200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovess V. Epidemiologie et santè mentale. Paris: Flammarion; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kovess V, Fournier L, Lesage AD, Lebigre FA, Caria A. Two validation studies of the CIDIS: a Simplified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Psychiatric Networks. 2001;4:10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carta MG, Carpiniello B, Kovess V, Porcedda R, Zedda A, Rudas N. Lifetime prevalence of major depression and dysthymia: results of a community survey in Sardinia. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;5:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0924-977X(95)00036-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwath E, Weissman MM. Epidemiology of depression and anxiety disorders. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GEP, editor. In Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1995. pp. 317–344. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . The 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO, Division of Mental Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Essau CA, Zerssen D, Von Krieg D, Zaudig M. Lifetime and six-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Munich follow-up study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;241:247–258. doi: 10.1007/BF02190261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Libowitz MR, Weissman MM. Social phobia. Comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiological sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:282–288. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker HR, Mulleians R, Klein KH, Battegay R. Identification of cases of anxiety disorders and affective disorders in the community according to ICD-10 and DSM-III-R by using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Meth Psychiat Research. 1992;2:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Dobler-Mikola A. The Zurich study: V anxiety and phobia in young adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1985;235:171–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00380989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepine JP, Lellouch J. Diagnosis and epidemiology of agoraphobia and social phobia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1995;18:S15–S26. [Google Scholar]

- Bijl RV, Ravellii A, van Zessen G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and incidence study (NEMESIS) Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol. 1998;33:587–595. doi: 10.1007/s001270050098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degonda M, Angst J. The Zurich study. XX. Social phobia and agoraphobia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;243:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02191571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lépine JP, Pélissolo A. Epidemiology and co-morbidity of social anxiety disorder. In: Westenberg HGM, den Boer JA, editor. In Focus on Psychiatry Social Anxiety Disorder. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Syn-Thesis Publishers; 1999. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Nelson CB, Lachner G. Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 1998;28:109–126. doi: 10.1017/S0033291797005928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza A, Cappello N, Olivetti E, Rendine S. A genetic history of Italy. Annals of Human Genetics. 1988;52:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1988.tb01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A. The history and geography of human genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason EO, Gudmundsdottir A, Boyle GJ. Six month prevalence of phobic symptoms in Iceland: an epidemiological postal survey. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:257–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199802)54:2<257::AID-JCLP15>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Hughes DC, Blazer DG. Urban /Rural differences in the prevalence of anxiety disorders. Am J Soc Psychiatry. 1986;6:249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JK, Weissman MM, Tischler GL, Holzer CE, Leaf PJ, Orvaschel H, Antony JC, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Kramer M. Six month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in three communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:959–967. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland RC, Orn H, Newman SC. Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1988;338:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb08544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick CL, Sowa B, Bland RC, Newman SC. Epidemilogy of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton: Phobic disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;376:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash KL, Klein DN. The relationship between age at onset and comorbidity in psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:703–707. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindal E, Stefansson JG. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in Iceland as estimated by the US National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU, Faravelli C, Bobes J, Patel A, Knapp M. A European perspective on social anxiety disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:5–16. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]