Abstract

The practice of sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia began in the mid to late 1990s. Since its establishment, this specialty has grown, and the number of specialists has increased. Based on the available data, sleep disorders are prevalent among the Saudi population, and the demand for sleep medicine services is expected to increase significantly. Currently, two training programs are providing structured training and certification in sleep medicine in this country. Recently, clear guidelines for accrediting sleep medicine specialists and technologists were approved. Nevertheless, numerous obstacles hamper the progress of this specialty, including the lack of trained technicians, specialists, and funding. Increasing the awareness of sleep disorders and their serious consequences among health care workers, health care authorities, and insurance companies is another challenge. Future plans should address the medical educational system at all levels to demonstrate the importance of early detection and the treatment of sleep disorders. This review discusses the current position of and barriers to sleep medicine practice and education in Saudi Arabia.

Citation:

Almeneessier AS, BaHammam AS. Sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(4):641–645.

Keywords: barriers, developing countries, education, polysomnography, Saudi Arabia, sleep medicine

INTRODUCTION

Saudi Arabia has a land area of approximately 2,150,000 km2 (830,000 mi2). Geographically, it is the fifth-largest country in Asia and the second-largest country in the Arab world. The last official census in 2015 estimated the population of Saudi Arabia at 31 million people; approximately two-thirds of the population are younger than 30 years, and one-third is younger than 15 years.1 Currently, the government is the major health care provider (79%), and the Ministry of Health is the major government-owned provider of health care services in Saudi Arabia.2,3 The private sector also contributes to the delivery of health care services (21%), particularly in cities and large towns.4 In government-owned hospitals, the government pays for all health care costs. However, in the private sector, the health care costs are paid by insurance companies or patients themselves. In 2010, the number of physicians and nurses in Saudi Arabia per 10,000 population was 16 and 36, respectively; these numbers are lower than those in developed countries.2

SLEEP DISORDERS IN SAUDI AR ABIA

According to the current evidence, sleep disorders are prevalent among the Saudi population.3,5 Two previous studies used the Berlin questionnaire to assess the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) risk and symptoms among middle-aged Saudi men and women and found that 3 of every 10 Saudi men and 4 of every 10 Saudi women are at high risk for OSA.6,7 A recent study that used polysomnography (PSG) to assess OSA in a random sample of Saudi school employees aged 30 to 60 years (n = 346) revealed that the rates of OSA (an apneahypopnea index) ≥ 5) were 11.2% and 4.0% in men and women, respectively, and the rates of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) (apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5 plus daytime sleepiness) were 2.8% (4.0% in men and 1.8% in women).8 In Western countries, the prevalence of OSAS is 3% to 7% in men and 2% to 5% in women.9,10 Parent-reported snoring has been described in 17.9% of elementary Saudi school children.11 A meta-analysis that included studies from all continents estimated the prevalence of parent-reported snoring in children to be 7.45% (95% confidence interval, 5.75–9.61).12 Wide variations in the reported prevalence of snoring in children have been shown in previously published studies in different parts of the world, ranging from 1.5% to 34.5%.11,13 Observed differences in reported snoring prevalence may be due to variations in snoring definitions, questionnaires used to elicit the results, and prevalence of obesity in Saudi elementary school children.11,12,14

The estimated prevalence of narcolepsy with cataplexy in Saudis is 40 per 100,000 people,15,16 which is within the range reported in other studies that showed the prevalence of narcolepsy with cataplexy to fall between 25 and 50 per 100,000 people.17 A national study reported the prevalence of restless leg syndrome among Saudis as 5.2%.18 This prevalence falls within previously reported ranges of restless leg syndrome prevalence (ie, 3.2% to 12%) in other countries.18,19

PR ACTICE AND STRUCTURE OF SLEEP MEDICINE

The practice of sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia began in the mid to late 1990s, and it has been rapidly expanding since its inception. Two national surveys have been conducted to quantitatively assess sleep medicine services in Saudi Arabia in 2005 and 2013.3,5 Despite the great progress made in sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia, service shortages continue to exist compared with services in developed countries. Sleep medicine facilities exist in 3 major cities: Riyadh (6 sleep facilities), Jeddah (7 sleep facilities), and Dammam (5 sleep facilities).3

Prior to 2009, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine accredited both sleep disorders centers and sleep-related breathing laboratories. According to these former standards, a facility considered a sleep-related breathing laboratory did not have a staff person who was a Diplomate of the American Board of Sleep Medicine or was board eligible, and these facilities could only promote the evaluation and treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep disorders centers, on the other hand, were required to promote the evaluation and treatment of all sleep disorders. Current American Academy of Sleep Medicine accreditation standards no longer draws this distinction, and they now use the term “sleep facility” to refer to all facilities eligible for accreditation.20 Using the former American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria, 15 facilities were defined as sleep disorders centers, and 3 were classified as sleep-disordered breathing laboratories. Only 7 facilities perform pediatric sleep studies.3 All sleep disorder facilities are hospital based.

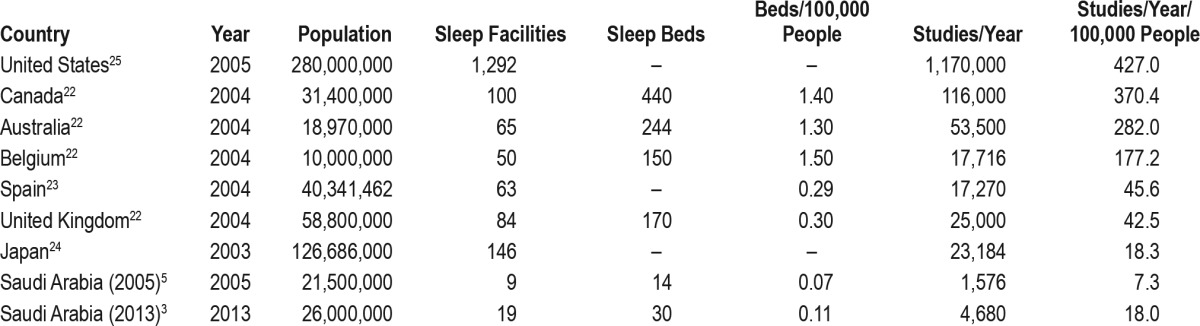

Table 1 shows the current number of sleep facilities, the number of beds designated for sleep studies, the number of beds per 100,000 people, and the number of sleep studies per 100,000 people in Saudi Arabia compared with data taken from developed countries.3,5,21–24 The number of beds per 100,000 people increased from 0.07 in 2005 to 0.11 in 2013, and the number of studies per 100,000 people increased from 7.3 in 2005 to 18.0 in 2013.3 Seven sleep facilities reported having pediatric sleep medicine specialists, and only 5 sleep facilities had accredited and certified sleep technologists.3 Of all of the sleep studies performed, 80.5% addressed patients with sleep-disordered breathing, 7.2% examined movement disorders, 4.8% studied narcolepsy, 6.8% investigated insomnia, and 0.7% explored other reasons.3 Administratively, 89.5% of all sleep facilities were under pulmonary medicine services.3 Most of the practicing sleep medicine specialists in Saudi Arabia have completed their specialty training in North America. Therefore, they strictly follow the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of different sleep disorders. The number of sleep medicine specialists (defined as doctors who completed a minimum of 6 months of formal full-time fellowship training in sleep medicine) in the 2013 national survey was 37.3 However, 5 sleep facilities have certified sleep technologists.3

Table 1.

Sleep medicine services in Saudi Arabia compared with other countries.

Saudi Arabia has many otolaryngologists who are interested in different surgical procedures that treat OSA. Recently, surgeons who have received training in special procedures, such as hypoglossal nerve stimulation, have begun practicing in Saudi Arabia. A few dentists with a special training in the management of OSA are also practicing in Saudi Arabia. Sleep medicine physicians provide cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, because there are no specialized psychologists in sleep facilities.

The Saudi Sleep Medicine group, which includes sleep medicine specialists throughout the country, was established in 2009. Since then, the group has held an annual congress that is well attended by practicing specialists and technologists in the region.

SLEEP MEDICINE AND TECHNOLOGY EDUCATION

Not enough qualified sleep medicine specialists and technicians exist in Saudi Arabia to meet the increasing demand for their services.5 To overcome this problem, sleep medicine fellowship programs have been established. King Saud University (KSU) took a major step forward by establishing the first structured fellowship program in sleep medicine in 2009. This program focuses on the clinical sciences of sleep medicine, the research skills needed for sleep medicine, and sleep disorders center management.25 The program is a 2-year fellowship. The first year provides combined pulmonary medicine and sleep medicine training, and the second year focuses on sleep medicine training. The first year is waived for those who have completed a pulmonary medicine fellowship, making the program only 1 year. The fellowship program can accommodate 2–3 fellows per year. As of December 2016, 7 fellows from 5 countries have graduated from the program. A second fellowship program was established in 2016 at King Abdulaziz University. Moreover, plans are ongoing to establish a national interdisciplinary training program that serves the entire country (Saudi Board of Sleep Medicine).

The lack of trained sleep technicians is a major obstacle that faces sleep medicine programs in Saudi Arabia.3,5 Currently, no national training program for sleep technology exists in this country. To overcome this problem, intensive courses and workshops are conducted 2–3 times per year to train sleep technologists. Moreover, 3-month and 6-month structured training programs are conducted for sleep technologists at KSU.

SLEEP MEDICINE AND TECHNOLOGY ACCREDITATION

In 2012, Saudi Arabia published clear guidelines for accrediting sleep medicine specialists and technologists.26–28 To ascertain the quality of medical care provided to patients with sleep disorders, the institution of national regulations and policies is essential to verify the competency of practicing sleep medicine physicians and technologists. The licensing of sleep medicine practitioners and technicians implies that the local health authorities recognize sleep medicine as a distinct medical specialty. In turn, this recognition will result in the expansion of provided services while maintaining a high standard of care. Therefore, the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCHS) formed the National Committee for the Accreditation of Sleep Medicine Practice, which developed national accreditation criteria for physicians and technologists in 2012.26 The accreditation guidelines considered the diversity of training programs previously available to current sleep medicine physicians. The guidelines define a sleep medicine physician as a medical doctor (MD) who is trained in the subspecialty of sleep medicine and has competence in the clinical assessment, physiological testing, diagnosis, management, and prevention of sleep and circa-dian rhythm disorders.26 The committee developed 2 pathways for accreditation of sleep medicine specialists. The first pathway includes physicians with board certification in sleep medicine from a body accredited by the SCHS, such as the American Board of Health Specialties or an SCHS-accredited local training program. The second pathway includes physicians with a certificate indicating the successful completion of a minimum of 6 months of full-time, structured, hands-on clinical training and patient care in a university or medical center accredited by the SCHS. Applicants using this pathway are required to meet more criteria to ascertain the number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures completed during training.26

BARRIERS TO THE PR ACTICE OF SLEEP MEDICINE

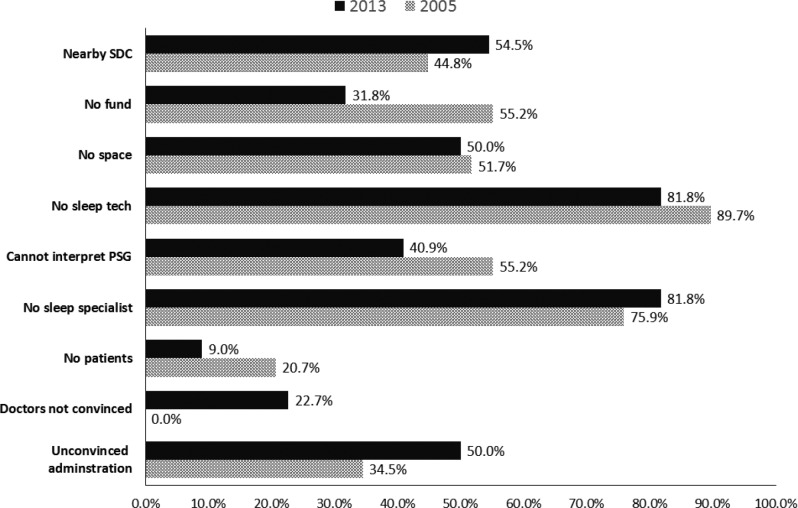

Although sleep medicine practice and training in Saudi Arabia has advanced greatly over the past decade, major obstacles continue to face this specialty and its practitioners. Figure 1 shows the barriers to the practice of sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia according to 2 national surveys.3,5 A discussion of the key barriers follows below.

Figure 1. The most important obstacles facing the establishment of sleep medicine facilities in hospitals that did not have sleep medicine services according to the 2013 and 2005 surveys.

2013 survey from Bahammam et al.3 2005 survey from Bahammam and Aljafen.5 PSG = polysomnography, SDC = sleep disorders center.

Shortage of Qualified Specialists

The number of trained qualified sleep medicine specialists in Saudi Arabia is relatively low: reportedly 37 physicians located at a few hospitals across 3 major cities.3 Another problem facing practicing physicians is that specialists often practice sleep medicine as a small part of a larger medical practice (eg, pulmonology, neurology, or psychiatry). Establishing sleep medicine practice requires a dedicated sleep medicine physician who has protected time for practicing sleep medicine.

Shortage of Trained Sleep Technologists

The shortage of trained sleep technologists is the main obstacle facing sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia.3,5 According to 2 surveys, more than 80% of the surveyed hospitals stated that a lack of trained sleep technologists was a major obstacle preventing the establishment of a sleep medicine service.3,5

Knowledge of Medical Students and Health Care Workers Regarding Sleep Medicine

In general, medical students in Saudi Arabia rarely have the chance to learn sleep medicine as part of their curriculum. According to a national survey of medical schools in Saudi Arabia that applied the Assessment of Sleep Knowledge in Medical Education survey, only 4.6% of respondents correctly answered at least 60% of the questions.29 The mean time spent teaching sleep medicine according to the surveyed medical schools was 2.6 hours.29 Likewise, the postgraduate teaching of sleep disorders during residency training is limited.30 The health care system in Saudi Arabia relies on a referral system in which the patient first meets with a primary care physician who assesses and decides on the patient's treatment plan. Two surveys have shown that primary care physicians' knowledge regarding sleep disorders is limited.31,32 The lack of education regarding sleep medicine has resulted in a culture of physicians who have a limited knowledge about sleep disorders; therefore, they are likely to underdiagnose and undertreat sleep disorders. Several local studies highlighted the underrecognition of sleep disorders among Saudi health care providers. One study reported that 53.2% of patient referrals to the sleep disorders clinic for narcolepsy were patient initiated.15 Moreover, the interval between the onset of narcolepsy symptoms and diagnosis was more than 8 years.15 Other studies have suggested a more than 10-year delay between symptom onset and referral to sleep disorders centers among Saudi patients with OSA.33,34 One study assessed the referral pattern among patients with insomnia and reported that only 19.4% of patients were referred to the sleep disorders center by their primary care physicians; the remaining referrals were patient initiated.35 Another study reported that referrals by otolaryngologists represented 8% of patients with OSA compared with 17.4% in the United States.36,37

Health Care Authorities and Insurance Companies

Some hospital decision makers do not consider sleep medicine services as a priority or core competency. A 2013 national survey revealed that “unconvinced administration” was one of the major obstacles facing the establishment of sleep disorder facilities in certain hospitals (50%) (Figure 1).3 Another barrier to the development of sleep medicine practice in the private sector is that most insurance companies do not cover the cost of sleep studies for patients with nonrespiratory sleep disorders, nor do they cover the cost to treat OSA with positive airway pressure therapy devices. However, some government-owned hospitals provide patients with sleep-related breathing disorders with positive airway pressure devices free of charge.

Lack of Outpatient/Freestanding Sleep Laboratories and Clinics

Another barrier to the expansion of the service provided to patients with sleep-related disorders is the fact that all sleep facilities are hospital based, and there is no effort or support for outpatient/freestanding sleep laboratories and clinics.

Diagnostic Equipment and After-Sale Service

As in most developing countries, some major obstacles that face practitioners include after-sale service, education, and technical support of diagnostic equipment.38 Frequently, local suppliers do not provide efficient after-sale services nor do they actively participate in hands-on training.

Unavailability of Medication

Sleep medicine specialists have difficulty obtaining commonly used medications to treat insomnia and narcolepsy (eg, Modafinil, Eszopiclone) because the manufacturers of these medications do not have distributers in Saudi Arabia. These medications can only be obtained through a special request from the hospital. Therefore, patients with sleep disorders might experience periods without treatment because of drug unavailability.

CONCLUSIONS

Sleep medicine practice and training is well established in Saudi Arabia. However, numerous obstacles exist that hinder its progress, including a lack of adequate specialized medical and technical staff as well as a lack of awareness about sleep disorders and their consequences among health care workers, health care authorities, and insurance companies.

One major challenge for the future is educating students and physicians about the high prevalence and serious consequences of sleep disorders. Population and strategic planning studies are needed to help policy makers estimate the number of sleep specialist and sleep facilities needed to meet the increasing demands of the growing population.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. This work was supported by the Strategic Technologies Program of the National Plan for Sciences and Technology and Innovation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (08-MED511-02).

REFERENCES

- 1.General Authority for Statistics: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia website. [Accessed October 11, 2016]. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en.

- 2.Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(10):784–793. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahammam AS, Alsaeed M, Alahmari M, Albalawi I, Sharif MM. Sleep medicine services in Saudi Arabia: the 2013 national survey. Ann Thorac Med. 2014;9(1):45–47. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.124444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health. Health Statistical Year Book. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahammam AS, Aljafen B. Sleep medicine service in Saudi Arabia. A quantitative assessment. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(6):917–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahammam AS, Al-Rajeh MS, Al-Ibrahim FS, Arafah MA, Sharif MM. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in middle-aged Saudi women in primary care. Saudi Med J. 2009;30(12):1572–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.BaHammam AS, Alrajeh MS, Al-Jahdali HH, BinSaeed AA. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in middle-aged Saudi males in primary care. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(3):423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wali SO, Abalkhail B, Alotaibi M, Krayem A. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in a Saudi population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A2555. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population-a review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(8):1311–1322. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–143. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BaHammam A, AlFaris E, Shaikh S, Bin Saeed A. Prevalence of sleep problems and habits in a sample of Saudi primary school children. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26(1):7–13. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2006.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):242–252. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-135MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R. Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):E60. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Shehri A, Al Fattani A, Al Alwan I. Obesity among Saudi children. Saudi J Obesity. 2013;1:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.BaHammam AS, Alenezi AM. Narcolepsy in Saudi Arabia. Demographic and clinical perspective of an under-recognized disorder. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(9):1352–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.al Rajeh S, Bademosi O, Ismail H, et al. A community survey of neurological disorders in Saudi Arabia: the Thugbah study. Neuroepidemiology. 1993;12(3):164–178. doi: 10.1159/000110316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longstreth WT, Jr, Koepsell TD, Ton TG, Hendrickson AF, van Belle G. The epidemiology of narcolepsy. Sleep. 2007;30(1):13–26. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BaHammam A, Al-shahrani K, Al-zahrani S, Al-shammari A, Al-amri N, Sharif M. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome in adult Saudis attending primary health care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(2):102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohayon MM, O'Hara R, Vitiello MV. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(4):283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Standards for Accreditation. American Academy of Sleep Medicine website. [Accessed February 20, 2017]. http://aasmnet.org/accreditation.aspx. Published November 2016.

- 21.Flemons WW DN, Kuna ST, Rodenstein DO, Wheatley J. Access to diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:668–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1124PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masa JF, Montserrat JM, Duran J. Diagnostic access for sleep apnea in Spain. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(2):195. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.170.2.950. author reply 195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tachibana N, Ayas NT, White DP. Japanese versus USA clinical services for sleep medicine. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2003;1(3):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tachibana N, Ayas NT, White DP. A quantitative assessment of sleep laboratory activity in the United States. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1(1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.University Sleep Disorders Center. Sleep Medicine Fellowship. King Saud University website. [Accessed October 9, 2016]. http://sleep.ksu.edu.sa/en/FellowshipProgram.

- 26.Bahammam AS, Al-Jahdali H, Alharbi AS, Alotaibi G, Asiri SM, Alsayegh A. Saudi regulations for the accreditation of sleep medicine physicians and technologists. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8(1):3–7. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.105710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montserrat JM, Teran-Santos J, Puertas FJ. Sleep medicine certification for physicians in Spain. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):1189–1191. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00188314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gozal D. Accreditation of sleep medicine in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a critical step toward quality outcomes. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8(1):1–2. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.105707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almohaya A, Qrmli A, Almagal N, et al. Sleep medicine education and knowledge among medical students in selected Saudi Medical Schools. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:133. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahammam AS. Sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia: current problems and future challenges. Ann Thorac Med. 2011;6(1):3–10. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.74269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleem A, Al Rashed F, Alkharboush G, et al. Primary care physicians' knowledge of sleep medicine and barriers to transfer of patients with sleep disorders: a cross-sectional study. Paper presented at: 23rd Congress of the European Sleep Research Society; September 13-16, 2016; Bologna, Italy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BaHammam AS. Knowledge and attitude of primary health care physicians towards sleep disorders. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(12):1164–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alotair H, Bahammam A. Gender differences in Saudi patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2008;12(4):323–329. doi: 10.1007/s11325-008-0184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.BaHammam AS, Alrajeh MS, Al-Ibrahim FS, Arafah MA, Sharif MM. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in middleaged Saudi women in primary care. Saudi Med J. 2009;30(12):1572–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.BaHammam A. Polysomnographic characteristics of patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Hypnosis. 2004;6(4):163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Punjabi NM, Welch D, Strohl K. Sleep disorders in regional sleep centers: a national cooperative study. Coleman II Study Investigators. Sleep. 2000;23(4):471–480. doi: 10.1093/sleep/23.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BaHammam A. Polysomnographic diagnoses of patients referred to the sleep disorders center by otolaryngologists. Saudi J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;6:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gitanjali B. Establishing a polysomnography laboratory in India: problems and pitfalls. Sleep. 1998;21(4):331–332. doi: 10.1093/sleep/21.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]