Abstract

This study investigated the transcriptomic response of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 to methionine. Transcriptome comparison of the S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type grown in chemically defined medium with 0–10 mM methionine revealed the elevated expression of various genes/operons involved in methionine synthesis and transport (fhs, folD, gshT, metA, metB-csd, metEF, metQ, tcyB, spd-0150, spd-0431 and spd-0618). Furthermore, β-galactosidase assays and quantitative RT-PCR studies demonstrated that the transcriptional regulator, CmhR (SPD-0588), acts as a transcriptional activator of the fhs, folD, metB-csd, metEF, metQ and spd-0431 genes. A putative regulatory site of CmhR was identified in the promoter region of CmhR-regulated genes and this CmhR site was further confirmed by promoter mutational experiments.

Keywords: Methionine, CmhR, Pneumococcus, MetE, MetQ

Data Summary

1. The sequence data of S. pneumonaie D39 which is used to construct all isolates in this study are available for download from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_008533.1.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files.

Impact Statement

This study demonstrates methionine-mediated gene regulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae and identifies methionine transport and biosynthesis genes. S. pneumoniae is a human nasopharyngeal pathogen that is responsible for millions of deaths each year. Methionine is one of the important amino acids for pneumococci and some of the methionine-regulated genes have been shown to have a role in virulence in different bacteria including S. pneumoniae. In other bacteria, two to three transcriptional regulators have been shown to be involved in the regulation of sulphur-containing amino acids. The current study highlights the transcriptomic response of S. pneumoniae to methionine and identifies an important transcriptional regulator, CmhR, which acts as an activator for its regulon genes. The regulatory site of CmhR in the promoter regions of its regulon genes is predicted and confirmed through mutagenesis studies. CmhR (also called MtaR in other bacteria) has been demonstrated to have a role in virulence in many bacteria. Therefore, investigation of the involvement of CmhR in virulence in S. pneumoniae might be of interest.

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizes the human nasopharynx during the first few months of life and is the causative agent of many human diseases including pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, otitis media and conjunctivitis, resulting in over a million deaths each year worldwide (Gray et al., 1982; Ispahani et al., 2004; O’Brien et al., 2009). Proper utilization of the available nutrients is a prerequisite for the successful colonization and survival of bacteria inside the human body in addition to the virulence factors it possesses (Phillips et al., 1990; Titgemeyer & Hillen, 2002). Virulence gene screening and targeted examination of specific nutrient transporters have established the importance of nutrient acquisition for the pathogenesis of many microbial pathogens (Darwin, 2005; Lau et al., 2001; Mei et al., 1997). Amino acids are one of the most important groups of nutrients needed for proper bacterial growth.

Methionine is an amino acid that is scarcely present in physiological fluids but its importance cannot be underestimated. It is vital for protein synthesis and is an integral component of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM: the main biological methyl donor needed for the biosynthesis of phospholipids and nucleic acids) (Fontecave et al., 2004; Shelver et al., 2003). A number of genes/gene clusters are present in S. pneumoniae that can synthesize methionine from other sources in the absence of methionine. Csd and MetE are part of the methionine synthesis pathway and are involved in conversion of cystathionine to homocysteine, and homocysteine to methionine, respectively (Kanehisa et al., 2014). Cystathionine and homocysteine can also be formed from homoserine, where O-acetyl-l-homoserine is converted to cystathionine by MetB. O-Acetyl-l-homoserine can be converted to homocysteine by MetB, SPD-1073 and SPD-1074 (spd-1073 and spd-1074 encode an O-acetylhomoserine aminocarboxypropyltransferase/cysteine synthase and a hypothetical protein, respectively) (Kanehisa et al., 2014).

Methionine can be synthesized by other microbes as they may convert homoserine to homocysteine through addition of a sulphur group from either cysteine (involving MetABC), sulphide (involving MetA and CysD) or methionine using the SAM recycling pathway (MetK, Pfs and LuxS) (Kovaleva & Gelfand, 2007). MetE (methionine synthase) then methylates homocysteine in combination with MetF (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase), and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (FolD) provides it with the methyl group to form methionine (Kovaleva & Gelfand, 2007; Ravanel et al., 1998). It has been shown that methionine biosynthetic genes are essential for full virulence in Brucella melitensis (Lestrate et al., 2000), Haemophilus parasuis (Hill et al., 2003) and Salmonella enterica (Ejim et al., 2004). Moreover, mutation of the methionine transport regulator MtaR led to attenuated virulence in Streptococcus agalactiae (Shelver et al., 2003), which suggests that methionine synthesis is indispensable for the existence of many bacteria during invasive infection.

In the current study, we elucidated the effect of methionine on the global gene expression of S. pneumoniae and demonstrated that the transcriptional regulator CmhR (SPD-0588) acts as a transcriptional activator for fhs, folD, metB-csd, metEF, metQ and spd-0431, involved in methionine uptake and utilization. The putative regulatory site of CmhR (5′-TATAGTTTSAAACTATA-3′, where S denotes G/C/A) in the promoter regions of its regulon genes is predicted and confirmed by promoter mutational experiments. This site is also found to be highly conserved in other pneumococcal strains and streptococci.

Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions and DNA isolation and modification.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type was grown as described previously (Afzal et al., 2014). For β-galactosidase assays, derivatives of S. pneumoniae D39 were grown in chemically defined medium (CDM) (Neves et al., 2002), supplemented with different concentrations of methionine as indicated in the Results. For selection on antibiotics, the medium was supplemented with the following concentrations of antibiotics: spectinomycin at 150 µg ml−1 and tetracycline at 2.5 µg ml−1 for S. pneumoniae; and ampicillin at 100 µg ml−1 for Escherichia coli. All bacterial strains used in this study were stored in 10 % (v/v) glycerol at −80 °C. For PCR amplification, chromosomal DNA of S. pneumoniae D39 (Lanie et al., 2007) was used as a template. Primers used in this study are based on the sequence of the D39 genome and are listed in Table S1, available in the online Supplementary Material.

Table 1. List of strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain/plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae | ||

| D39 | Serotype 2 strain. cps 2 | Laboratory of P. Hermans |

| MA1100 | D39 ΔcmhR; SpecR | This study |

| MA1101 | D39 ΔbgaA:: Pspd-0150-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1102 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PmetQ-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1103 | D39 ΔbgaA:: Pspd-0431-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1104 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PmetE-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1105 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PgshT-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1106 | D39 ΔbgaA:: Pspd-0618-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1107 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PfolD-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1108 | D39 ΔbgaA:: Pfhs-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1109 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PtcyB-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1110 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PmetA-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1111 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PmetB-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1112 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: PmetQ-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1113 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: Pspd-0431-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1114 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: PmetE-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1115 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: PfolD-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1116 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: Pfhs-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1117 | MA1100 ΔbgaA:: PmetB-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1118 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PfolD-M-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1119 | D39 ΔbgaA:: Pfhs-M-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| MA1120 | D39 ΔbgaA:: PmetB-M-lacZ; TetR | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| EC1000 | KmR; MC1000 derivative carrying a single copy of the pWV1 repA gene in glgB | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPP2 | AmpR TetR; promoter-less lacZ. For replacement of bgaA with promoter lacZ fusion. Derivative of pPP1 | Halfmann et al. (2007) |

| pMA1101 | pPP2 Pspd-0150-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1102 | pPP2 PmetQ-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1103 | pPP2 Pspd-0431-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1104 | pPP2 PmetE-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1105 | pPP2 PgshT-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1106 | pPP2 Pspd-0618-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1107 | pPP2 PfolD-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1108 | pPP2 Pfhs-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1109 | pPP2 PtcyB-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1110 | pPP2 PmetA-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1111 | pPP2 PmetB-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1112 | pPP2 PfolD-M-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1113 | pPP2 Pfhs-M-lacZ | This study |

| pMA1114 | pPP2 PmetB-M-lacZ | This study |

Construction of a cmhR mutant.

A cmhR (spd-0588) deletion mutant (MA1100) was made by allelic replacement with a spectinomycin-resistance cassette. Briefly, primers cmhR-1/cmhR-2 and cmhR-3/cmhR-4 were used to generate PCR fragments of the left and right flanking regions of cmhR. PCR products of left and right flanking regions of cmhR contain AscI and NotI restriction enzyme sites, respectively. The spectinomycin-resistance marker, which is amplified by primers SpecR/SpecF from pORI38, also contains AscI and NotI restriction enzyme sites on its ends. Then, by restriction and ligation, the left and right flanking regions of cmhR were fused to the spectinomycin-resistance gene. The resulting ligation products were transformed to S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type and selection of the mutant strains was done with the appropriate concentration of spectinomycin.

For transformation, cells were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of ~0.1. Then, 0.2 % BSA and 1 mM CaCl2 were added to the cells. A 1 ml aliquot of the grown culture was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube and 100 ng µl−1 of CSP1 (Competence Stimulating Peptide 1) was added to the culture. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 10–12 min. Then, the ligation mixture was added to the incubated cells and the cells were allowed to grow for 90–120 min at 37 °C. After growth, the culture was spun for 1 min at 7000 r.p.m. and most of the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was dissolved in the remaining medium (50–100 µl) and plated on blood agar plates with 1 % sheep blood. The cmbR mutant was further confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Construction of promoter lacZ-fusions and β-galactosidase assays.

Chromosomal transcriptional lacZ-fusions to the spd-0150, metQ (spd-0151), spd-0431, metE (spd-0510), gshT (spd-0540), spd-0618, folD (spd-0721), fhs (spd-1087), tcyB (spd-1290), metA (spd-1406) and metB (spd-1353) promoters were constructed in the integration plasmid pPP2 (Halfmann et al., 2007) with primer pairs mentioned in Table S1, resulting in pMA1101–1111, respectively. These constructs were further introduced into S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type, resulting in strains MA1101–11, respectively. pMA1102, pMA1103, pMA1104, pMA1107, pMA1108 and pMA1111 were also transformed into the D39 ΔcmhR strain resulting in strains MA1112–17, respectively. The following sub-clones of PfolD, Pfhs and PmetB with mutations in the cmhR site were made in pPP2 (Halfmann et al., 2007) using the primer pairs mentioned in Table S1: PfolD-M, Pfhs-M and PmetB-M, resulting in plasmids pMA1112–14, respectively. These constructs were introduced into the S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type, resulting in strains MA1118–20, respectively. All plasmid constructs were further checked for the presence of insert by PCR and DNA sequencing.

The β-galactosidase assays were performed as described before (Halfmann et al., 2007; Israelsen et al., 1995) using cells that were harvested in the mid-exponential growth phase and grown in CDM.

Microarray analysis.

Microarray analysis was performed as described before (Afzal et al., 2015a; Shafeeq et al., 2015). For DNA microarray analysis of S. pneumoniae in the presence of methionine, the transcriptome of S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type, grown in replicates in CDM with 10 mM methionine, was compared to that grown in CDM with 0 mM methionine, and harvested at respective mid-exponential growth phases. For the identification of differentially expressed genes a Bayesian P-value <0.001 and a fold-change cut-off >1.5 was applied.

For RNA isolation the following procedure was performed: the pellet of the harvested cells was resuspended in 400 µl TE buffer (diethylpyrocarbonate) and the resuspended cells were added into RNA-free screw-cap tubes containing 0.5 g glass beads, 50 µl 10 % SDS, 500 µl phenol/chloroform: isoamylalcohol, macaloid layer (150–175 µl, not exact as it is highly viscous). To break the cells the screw-cap tubes were placed in a bead beater and two 1 min pulses were applied with 1 min interval on ice. The samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 10 000 r.p.m. (4 °C). Then, 500 µl chloroform/isoamylalcohol (24 : 1) was added to the tubes containing the upper phase of the centrifuged tubes and the samples were again centrifuged for 5 min at 10 000 r.p.m. (4 °C). A 500 µl aliquot of the upper phase was transferred to fresh tubes and total RNA was isolated using the High pure RNA isolation kit (Roche life science) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed on a chip using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer according to the manufacturer’s instructions and an RNA integrative number (RIN) value above 8 was considered good. All other procedures regarding the DNA microarray experiment and data analysis were performed as previously described (Afzal et al., 2015b; Shafeeq et al., 2011a, b). Microarray data have been submitted to GEO under accession number GSE88766.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and purification for quantitative RT-PCR.

For quantitative RT-PCR, S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type and D39 ∆cmhR were grown in CDM. RNA isolation was done as described above. First, cDNA synthesis was performed on RNA (Shafeeq et al., 2011b; Yesilkaya et al., 2008). cDNA (2 µl) was amplified in a 20 µl reaction volume that contained 3 pmol of each primer (Table S1) and the reactions were performed in triplicate (Shafeeq et al., 2011b). The transcription level of specific genes was normalized to gyrA transcription, amplified in parallel with primers gyrA-F and gyrA-R. The results were interpreted using the comparative CT method (Schmittgen & Livak, 2008). Differences in expression of twofold or greater relative to the control were considered significant.

Results

Methionine-dependent gene regulation in S. pneumoniae D39

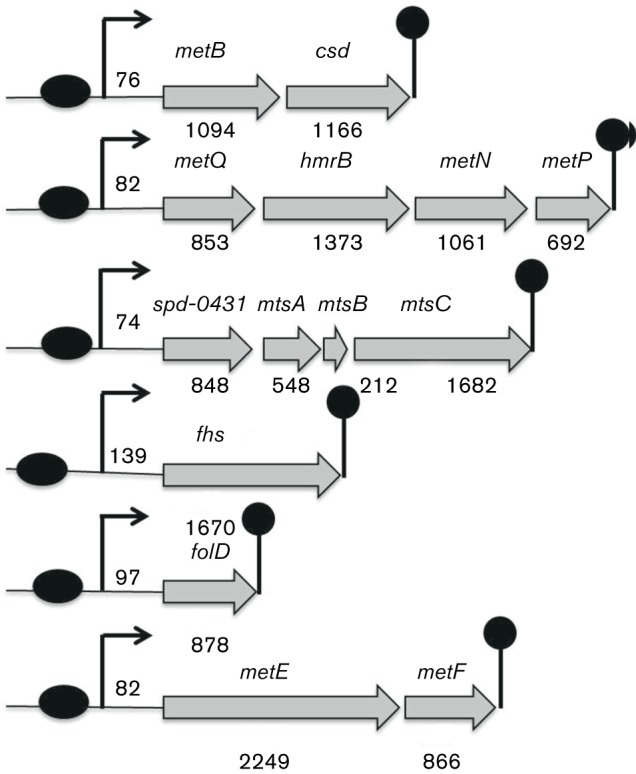

The importance of methionine acquisition and synthesis for S. pneumoniae growth and virulence has been reported before (Basavanna et al., 2013). In this study, we explored the impact of methionine on the transcriptome of S. pneumoniae D39. To do so, we performed transcriptome comparison of S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type grown in CDM with 0–10 mM methionine. The concentration of methionine in CDM is around 0.67 mM. A number of genes/gene clusters were differentially regulated under our tested conditions (Table 2). Putative methionine pathway genes were significantly upregulated in the absence of added methionine in CDM. These genes include spd-0150 [coding for a predicted glutathione ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter, substrate-binding protein], metQ–hmrB–metNP (a gene cluster putatively involved in methionine transport, whereas hmrB codes for a putative N-acyl-l-amino acid amidohydrolase), spd-0431 (hypothetical protein), metEF (coding for 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, respectively), gshT (coding for a predicted glutathione ABC transporter, substrate-binding protein), spd-0616–18 (coding for a predicted polar amino acid ABC transporter), folD [coding for a methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP+)], fhs (coding for a formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase), metA (coding for a homoserine O-succinyltransferase), metB–csd (coding for a cystathionine gamma-synthase and cysteine desulfurase, respectively) and tcyBC (coding for a cysteine ABC transporter). The genetic organization of these putative methionine genes is shown in Fig. 1. There were some other genes (spd-0360–63, spd-0372–74, spd-0385–91, spd-0447–49, spd-0616–18, spd-1073–75, spd-1098–99 and spd–2037) whose expression was also altered under our tested conditions and whose role in methionine biosynthesis and transport may be of interest. Some of the genes differentially regulated in our transcriptome comparison are putatively involved in carbohydrate transport and utilization (spd-0424–28 and spd-0559–62), and these genes have been studied in our previous studies (Afzal et al., 2014; Shafeeq et al., 2012). The spd-0424–28 genes putatively encode a cellobiose/lactose-specific phosphotransferase system, and transcriptional regulator RokA acts as a transcriptional repressor of this operon (Shafeeq et al., 2012). The spd-0559–62 genes putatively code for a lactose/galactose-specific phosphotransferase system and the regulatory mechanism of this gene cluster is not yet known. A gene, spd-0588, coding for a transcriptional regulator is also upregulated in our methionine microarray. Our bioinformatics analysis shows that this gene shares high homology with mtaR present in other bacteria and because of its putative involvement in cysteine and methionine metabolism we call it cmhR. The upregulation of cmhR under our tested conditions might be an indication of its involvement in the regulation of the methionine genes.

Table 2. Summary of transcriptome comparison of S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type grown in CDM with 0–10 mM methionine.

PTS, phosphotransferase system.

| D39 tag* | Function† | Ratio‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated genes | ||

| spd-0152 | Peptidase, M20/M25/M40 family protein | 2.9 |

| spd-0153 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 2.3 |

| spd-0154 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative | 1.9 |

| spd-0360 | PTS system, mannitol-specific IIBC components | 3.4 |

| spd-0361 | Transcriptional regulator, putative | 3.0 |

| spd-0362 | PTS system, mannitol-specific enzyme IIA | 2.8 |

| spd-0363 | Mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase | 3.2 |

| spd-0372 | Sodium:alanine symporter family protein | 2.2 |

| spd-0373 | Hypothetical protein | 4.8 |

| spd-0374 | Exfoliative toxin, putative | 2.1 |

| spd-0424 | PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIC component | 2.6 |

| spd-0426 | PTS system, lactose-specific IIA component | 2.0 |

| spd-0427 | 6-Phospho-β-galactosidase | 2.5 |

| spd-0428 | PTS system, lactose-specific IIBC components | 2.5 |

| spd-0429 | Potassium uptake protein, Trk family protein | 2.4 |

| spd-0430 | Potassium uptake protein, Trk family protein | 2.0 |

| spd-0431 | Hypothetical protein | 1.8 |

| spd-0432 | Hypothetical protein | 1.8 |

| spd-0434 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 1.6 |

| spd-0510 | 5-Methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine S-methyltransferase, MetE | 5.0 |

| spd-0511 | 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, MetF | 7.7 |

| spd-0512 | Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | 1.8 |

| spd-0513 | Serine O-acetyltransferase | 1.6 |

| spd-0514 | Acetyltransferase, GNAT family protein | 1.8 |

| spd-0515 | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | 1.5 |

| spd-0540 | Amino acid ABC transporter, amino acid-binding protein, putative | 2.4 |

| spd-0559 | PTS system IIA component, putative | 2.0 |

| spd-0560 | PTS system, IIB component, putative | 1.5 |

| spd-0561 | PTS system, IIC component, putative | 2.2 |

| spd-0562 | β-Galactosidase precursor, putative | 2.5 |

| spd-0588 | Transcriptional regulator, putative, CmhR | 1.5 |

| spd-0610 | Hypothetical protein | 2.5 |

| spd-0611 | Hypothetical protein | 2.4 |

| spd-0612 | Lipoprotein, putative | 2.2 |

| spd-0613 | Hypothetical protein | 2.6 |

| spd-0614 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 4.2 |

| spd-0616 | Amino acid ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 1.7 |

| spd-0617 | Amino acid ABC transporter, permease protein | 2.3 |

| spd-0618 | Amino acid ABC transporter, permease protein | 1.7 |

| spd-0818 | Transcriptional regulator, LysR family protein | 2.1 |

| spd-1073 | O-Acetylhomoserine aminocarboxypropyltransferase/cysteine synthase | 2.3 |

| spd-1074 | Hypothetical protein | 2.3 |

| spd-1075 | Transporter, FNT family protein, putative | 2.0 |

| spd-1087 | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase, Fhs | 1.7 |

| spd-1351 | Snf2 family protein | 1.5 |

| spd-1352 | Aminotransferase, class II, Csd | 3.5 |

| spd-1353 | Cys/Met metabolism PLP-dependent enzyme, putative, MetB | 1.5 |

| spd-1355 | Hypothetical protein | 2.4 |

| spd-1899 | Glutamine amidotransferase, class 1 | 1.6 |

| Downregulated genes | ||

| spd-0147 | CAAX amino terminal protease family protein | −2.0 |

| spd-0278 | Hypothetical protein | −2.2 |

| spd-0279 | PTS system, IIB component | −2.6 |

| spd-0281 | PTS system, IIA component | −4.3 |

| spd-0282 | Hypothetical protein | −3.8 |

| spd-0283 | PTS system, IIC component | −3.4 |

| spd-0385 | 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase II | −2.1 |

| spd-0386 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, biotin carboxyl carrier protein | −2.5 |

| spd-0387 | β-Hydroxyacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) dehydratase FabZ | −2.2 |

| spd-0388 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, biotin carboxylase | −2.1 |

| spd-0389 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, carboxyl transferase, beta subunit | −4.1 |

| spd-0390 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, carboxyl transferase, alpha subunit | −2.3 |

| spd-0391 | Hypothetical protein | −2.3 |

| spd-0447 | Transcriptional regulator, GlnR | −2.1 |

| spd-0448 | Glutamine synthetase, GlnA | −2.5 |

| spd-0449 | Hypothetical protein | −2.1 |

| spd-0636 | Pyruvate oxidase, SpxB | −3.6 |

| spd-1041 | Glutaredoxin-like protein, NrdH | −3.6 |

| spd-1042 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase, NrdE | −3.0 |

| spd-1098 | Amino acid ABC transporter, GlnP | −2.1 |

| spd-1099 | Amino acid ABC transporter, GlnQ | −2.0 |

| spd-1461 | Manganese ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein, PsaB | −2.7 |

| spd-1463 | ABC transporter, substrate binding lipoprotein | −2.3 |

| spd-1464 | Thiol peroxidase, PsaD | −2.2 |

| spd-2037 | Cysteine synthase A, CysK | −1.8 |

*Gene numbers refer to D39 locus tags.

†D39 annotation/TIGR4 annotation (Lanie et al., 2007).

‡Ratio represents the fold increase/decrease in the expression of genes in CDM with 0–10 mM methionine. Errors in the ratios never exceeded 10 % of the given values.

Fig. 1.

Organization of the CmhR-regulated genes in S. pneumoniae D39. Black ovals represent the putative CmhR binding sites, whereas the lollipop structures represent the putative transcriptional terminators. Numbers below genes represent the number of base pairs of genes, whereas the number between putative binding sites and start of genes shows the number of bases between the translation start sites and the putative CmhR binding sites. See text for further details.

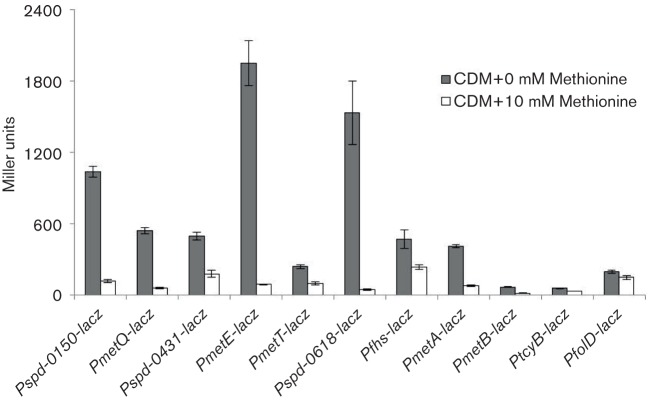

Confirmation of methionine-dependent expression of fhs, folD, gshT, metA, metB, metEF, metQ, tcyB, spd-0150, spd-0431 and spd-0618

To confirm our microarray results and study the expression of fhs, folD, gshT, metA, metB–csd, metEF, metQ, tcyB, spd-0150, spd-0431 and spd-0618 in the presence and absence of methionine in CDM, we constructed promoter lacZ-fusions of these putative methionine genes and transformed these promoter lacZ-fusions into S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type. β-Galactosidase assays were performed on cells grown in CDM with 0 and 10 mM methionine (Fig. 2). Our β-galactosidase assay results showed that expression of fhs, folD, gshT, metA, metB-csd, metEF, metQ, tcyB, spd-0150, spd-0431 and spd-0618 promoters increased significantly in the absence of added methionine in CDM. These data further confirm our microarray data mentioned above.

Fig. 2.

Expression levels (in Miller units) of Pspd-0150-lacZ, PmetQ-lacZ, Pspd-0431-lacZ, PmetE-lacZ, PgshT-lacZ, Pspd-0618-lacZ, Pfhs-lacZ, PmetA-lacZ, PmetB-lacZ, PtcyB-lacZ and PfolD-lacZ in S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type grown in CDM with 0 and 10 mM methionine. Standard deviations of three independent experiments are indicated by bars.

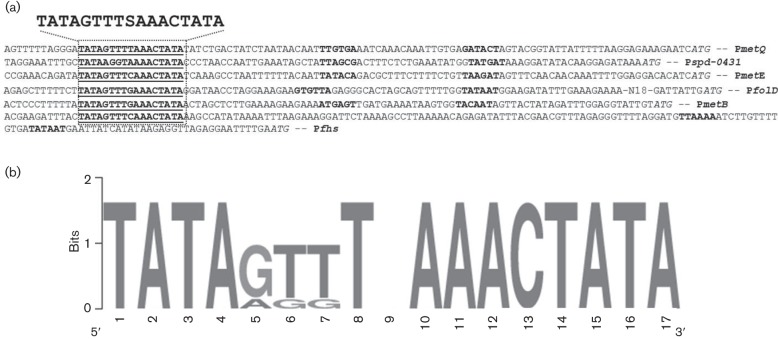

Prediction of the CmhR regulatory site in CmhR-regulated genes

A number of genes/gene clusters were differentially regulated under our tested conditions. One important gene that was significantly upregulated in our microarray results was cmhR (spd-0588). This gene codes for a transcriptional regulator CmhR, which putatively belongs to the LysR family of proteins (Shelver et al., 2003). CmhR is a homologue of MtaR of other bacteria and our bioinformatics analysis shows that the MtaR binding site is also present in the genes of the CmhR regulon in S. pneumoniae. Using Genome2D software (Baerends et al., 2004) and a MEME motif sampler search (Bailey & Elkan, 1994), a 17 bp palindromic sequence was found in the promoter regions of several genes in S. pneumoniae D39. These genes were identified in our methionine microarray suggesting their role in methionine transport and metabolism. The CmhR regulatory site present in the promoter regions of methionine genes is shown in Fig. 3(a). A weight matrix of these putative CmhR regulatory sites (5′-TATAGTTTSAAACTATA-3′) was constructed using these DNA regions (Fig. 3b). This DNA sequence may serve as the CmhR regulatory site in S. pneumoniae. Promoter regions of these genes were also examined in other streptococcal species (Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus thermophiles, Streptococcus uberis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus gallolyticus, Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus suis) to check if the CmhR regulatory site is also conserved in those streptococci. From this study, we conclude that the CmhR regulatory sequence is highly conserved in these streptococci as well (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Identification of the CmhR regulatory site. (a) Weight matrix of the identified CmhR regulatory site in the promoter region of metQ, spd-0431, metE, folD, metB and fhs. (b) Position of the CmhR regulatory site in the promoter region of metQ, spd-0431, metE, folD, metB and fhs. Core promoter sequences are in bold, translational start sites are in italic and putative CmhR regulatory sites are bold-underlined.

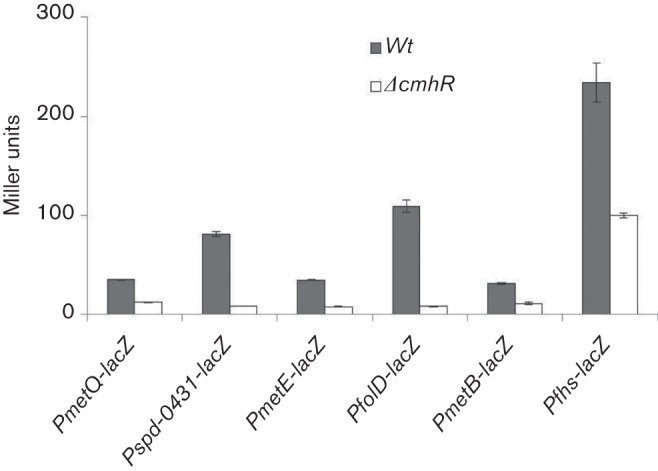

CmhR acts as transcriptional activator of metQ, spd-0431, metEF, folD, fhs and metB-csd in S. pneumoniae D39

The genes that are proposed to be the part of the CmhR regulon are metQ, spd-0431, metEF, folD, fhs and metB-csd. To investigate the role of CmhR in the regulation of the proposed CmhR regulon, we made a cmhR deletion mutant and transformed the lacZ-fusions of the promoter regions of these genes in to D39 ∆cmhR and performed β-galactosidase assays in CDM (Fig. 4). The results of the β-galactosidase assays showed that the activity of all these promoters decreased significantly in D39 ∆cmhR compared to the D39 wild-type, suggesting a role for CmhR as a transcriptional activator of these genes.

Fig. 4.

Expression levels (in Miller units) of PmetQ-lacZ, Pspd-0431-lacZ, PmetE-lacZ, PfolD-lacZ, PmetB-lacZ and Pfhs-lacZ in S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type and D39 ∆cmhR grown in CDM. Standard deviations of three independent experiments are indicated as bars.

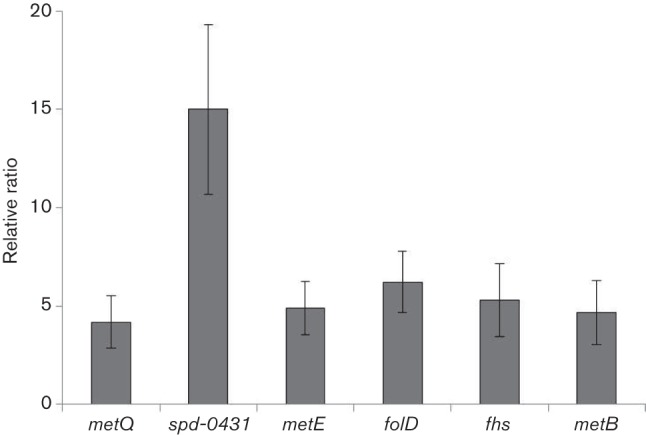

To further confirm our β-galactosidase assay results mentioned above, we performed quantitative RT-PCR on CmhR-regulated genes (metQ, spd-0431, metEF, folD, fhs and metB). Our quantitative RT-PCR results also demonstrated that the expression of these genes increased significantly in the D39 wild-type compared to D39 ∆cmhR (Fig. 5). These results further confirm that CmhR acts as a transcriptional activator of metQ, spd-0431, metEF, folD, fhs and metB-csd.

Fig. 5.

The relative increase in the expression of metQ, spd-0431, metE, folD, fhs and metB in S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type compared to D39 ΔcmhR grown in CDM. Expression of metQ, spd-0431, metE, folD, fhs and metB was normalized with the housekeeping gene gyrA. Results represent the mean and standard deviation of three independent replicates.

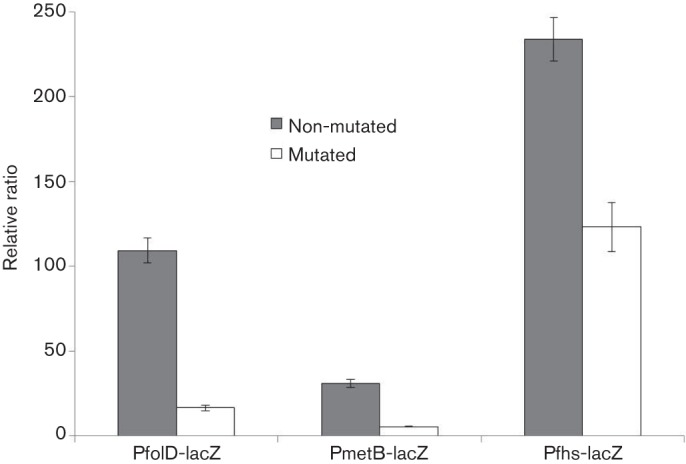

Verification of a CmhR regulatory site in CmhR-regulated genes

To verify the CmhR regulatory site present in the promoter regions of the CmhR-regulated genes (metQ, spd-0431, metEF, folD, fhs and metB-csd), we made transcriptional lacZ-fusions of PfolD, Pfhs and PmetB, where conserved bases in the putative cmhR regulatory sites were mutated (shown in bold-underlined) in PfolD (5′-TATAGTTTGAAACTATA-3′ to 5′-TCGCGTTTGAAACGCGA-3′), Pfhs (5′-TATAGTTTCAAACTATA-3′ to 5′-TCGCGTTTCAAACGCGA-3′) and PmetB (5′-TATAGTTTGAAACTATA-3′ to 5′-TCGCGTTTGAAACGCGA-3′), and β-galactosidase assays were performed with cells grown in CDM. The expression of these promoters with mutated conserved bases in CmhR regulatory sites decreased significantly. These results confirm that the predicted CmhR sites present in the promoter regions of these genes are active and intact in S. pneumoniae D39 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Expression levels (in Miller units) of mutated and non-mutated CmbR regulatory site in PfolD-lacZ, PmetB-lacZ and Pfhs-lacZ in S. pneumoniae D39 wild-type grown in CDM. Standard deviations of three independent experiments are indicated as bars.

Discussion

Bacterial pathogens need to acquire the essential nutrients from their surroundings inside the human host in order to survive and cause infections (Eisenreich et al., 2010; Kilian et al., 1979). In this study, we have explored the impact of methionine on the gene expression of S. pneumoniae D39 and found that a number of genes/operons respond to methionine. The results presented in this study will significantly enhance our understanding of the role of methionine on the gene expression of S. pneumoniae.

Several regulatory systems involved in the regulation of methionine biosynthesis have been reported in bacteria. In most Gram-positive bacteria, RNA structures acting on the level of premature termination of transcription control methionine biosynthesis: S-boxes present upstream of methionine biosynthesis genes in the Bacillales and Clostridia (Epshtein et al., 2003; McDaniel et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2003), and methionine-specific T-boxes in the Lactobacillales (Grundy & Henkin, 2003; Rodionov et al., 2004). Conversely, neither S-boxes nor methionine-specific T-boxes were found in Streptococcaceae for all methionine biosynthesis genes, with metK being the only exception that is regulated by the SMK-riboswitch (Fuchs et al., 2006). Therefore, it is clear that methionine biosynthesis in the Streptococcacae is controlled by a different mechanism that evolved after the split of this group from other Firmicutes.

Three transcriptional factors have been found to play a role in regulation of methionine metabolism in streptococci: MtaR in S. agalactiae, its orthologue MetR in S. mutans and CmbR (earlier known as FhuR) in Lactococcus lactis (Fernández et al., 2002). Methionine uptake decreased fivefold in the mtaR mutant in comparison to the wild-type in S. agalactiae, suggesting its role as a transcriptional activator of the methionine transport genes (Shelver et al., 2003). By contrast, MetJ and MetR regulate the expression of methionine biosynthetic genes in E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Weissbach & Brot, 1991). The E. coli met genes (except for metH) are negatively regulated by MetJ, a transcriptional repressor, with SAM serving as a co-repressor (Saint-Girons et al., 1988,). These genes are also positively regulated by a LysR-type transcriptional regulator MetR, with homocysteine as a co-effector (Cai et al., 1989; Cowan et al., 1993; Mares et al., 1992). CmbR in L. lactis has been demonstrated to activate most genes involved in the methionine and cysteine biosynthesis pathway in the absence of cysteine (Fernández et al., 2002; Sperandio et al., 2005). MetR has also been shown to regulate a number of methionine biosynthesis genes (Sperandio et al., 2007) by binding to the DNA motif suggested by Rodionov et al. (2004). The regulatory proteins mentioned above belong to the LysR family of transcriptional factors, which is the most abundant family of transcriptional regulators in bacteria (Maddocks & Oyston, 2008). These transcriptional regulators control diverse biological pathways such as central metabolism, cell division, quorum sensing, virulence, motility, nitrogen fixation, oxidative stress responses, toxin production, attachment and secretion. These transcriptional regulators act as either transcriptional activators or repressors, and often are transcribed divergently with one of the regulated genes (Schell, 1993). LysR-family regulators consist of two characteristic domains, an N-terminal helix–turn–helix DNA binding domain (PF00126) and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (PF03466). There appear to be two transcriptional regulators in S. pneumoniae that control the expression of the cysteine and methionine genes. CmhR in S. pneumoniae belongs to the LysR family of transcriptional factors and has a helix–turn–helix domain and a substrate-binding domain of LysR-type transcriptional regulators. The second is CmbR and study of its regulatory mechanism might be of interest (L. lactis has also two: CmbR and CmhR). Our results showed that CmhR acts as a transcriptional activator for a number of genes involved in methionine uptake and biosynthesis and deletion of CmhR led to downregulation of the CmhR genes. The deletion of CmhR also hampers growth of S. pneumoniae (data not shown), which might be an indication of the importance of this protein in the lifestyle of pneumococci.

In this study, we have demonstrated that the CmhR regulon consists of metQ, spd-0431, metEF, fhs, metB-csd and folD in S. pneumoniae D39. There are two bacterial methionine transport systems: the methionine ABC uptake transporter (MUT) family (Hullo et al., 2004; Merlin et al., 2002) and a secondary transporter BcaP (den Hengst et al., 2006). The MUT system is encoded by the metD locus in E. coli and consists of the MetQ substrate binding protein (SBP), MetL trans-membrane permease and the MetN cytoplasmic ATP-hydrolysing protein (ATPase) (Merlin et al., 2002). In S. pneumoniae D39, the spd-0150–54 locus encodes a methionine uptake ABC transporter and deletion of the gene encoding the lipoprotein MetQ resulted in a strain that had reduced growth in methionine-restricted media and no detectable uptake of radioactive methionine (Basavanna et al., 2013). Moreover, deletion of another important locus encoding MetEF (which is also part of the CmhR regulon) increased the growth defect of the metQ deletion strain in methionine-restricted media and in blood plasma, strengthening a role for the products of these genes in methionine synthesis (Basavanna et al., 2013). Micro-organisms can synthesize methionine by converting homoserine to homocysteine through addition of a sulphur group from either cysteine (requiring MetABC), sulphide (requiring MetA and CysD) or methionine using the SAM recycling pathway (MetK, Pfs and LuxS) (Kovaleva & Gelfand, 2007). Homocysteine is then methylated by methionine synthase (MetE) in conjunction with a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MetF), with the methyl group supplied by 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, to form methionine (Kovaleva & Gelfand, 2007). Existing data show that methionine biosynthetic genes are required for the full virulence of B. melitensis (Lestrate et al., 2000), H. parasuis (Hill et al., 2003) and Salmonella enterica (Ejim et al., 2004), and that mutation of the S. agalactiae methionine regulator MtaR attenuates virulence (Shelver et al., 2003), suggesting methionine synthesis is essential for survival of many bacteria during invasive infection. These observations also suggest that CmhR might have a role in pneumococcal pathogenesis and further studies may shed more light on this. Our microarray results show that the genes discussed above are part of methionine biosynthesis and transport genes, and are differentially regulated in our methionine microarray. Therefore, further investigations of the CmhR regulon may provide valuable information regarding virulence mechanisms in S. pneumoniae, which could be very useful for devising strategies to combat pneumococcal infections.

Acknowledgements

M.A. was supported by Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan, under the faculty development programme of HEC Pakistan.

Supplementary Data

Abbreviations:

- SAM

S-adenosyl methionine

References

- Afzal M., Shafeeq S., Kuipers O. P.(2014). LacR is a repressor of lacABCD and LacT is an activator of lacTFEG, constituting the lac gene cluster in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol 805349–5358. 10.1128/AEM.01370-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzal M., Manzoor I., Kuipers O. P.(2015a). A fast and reliable pipeline for bacterial transcriptome analysis case study: serine-dependent gene regulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzal M., Shafeeq S., Henriques-Normark B., Kuipers O. P.(2015b). UlaR activates expression of the ula operon in Streptococcus pneumoniae in the presence of ascorbic acid. Microbiology 16141–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerends R. J., Smits W. K., de Jong A., Hamoen L. W., Kok J., Kuipers O. P.(2004). Genome2D: a visualization tool for the rapid analysis of bacterial transcriptome data. Genome Biol 5R37. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-5-r37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Elkan C.(1994). Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol 228–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basavanna S., Chimalapati S., Maqbool A., Rubbo B., Yuste J., Wilson R. J., Hosie A., Ogunniyi A. D., Paton J. C., et al. (2013). The effects of methionine acquisition and synthesis on Streptococcus pneumoniae growth and virulence. PLoS One 8e49638. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. Y., Maxon M. E., Redfield B., Glass R., Brot N., Weissbach H.(1989). Methionine synthesis in Escherichia coli: effect of the MetR protein on metE and metH expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 864407–4411. 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan J. M., Urbanowski M. L., Talmi M., Stauffer G. V.(1993). Regulation of the Salmonella typhimurium metF gene by the MetR protein. J Bacteriol 1755862–5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin A. J.(2005). Genome-wide screens to identify genes of human pathogenic Yersinia species that are expressed during host infection. Curr Issues Mol Biol 7135–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hengst C. D., Groeneveld M., Kuipers O. P., Kok J.(2006). Identification and functional characterization of the Lactococcus lactis CodY-regulated branched-chain amino acid permease BcaP (CtrA). J Bacteriol 1883280–3289. 10.1128/JB.188.9.3280-3289.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W., Dandekar T., Heesemann J., Goebel W.(2010). Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol 8401–412. 10.1038/nrmicro2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejim L. J., D'Costa V. M., Elowe N. H., Loredo-Osti J. C., Malo D., Wright G. D.(2004). Cystathionine beta-lyase is important for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Infect Immun 723310–3314. 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3310-3314.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epshtein V., Mironov A. S., Nudler E.(2003). The riboswitch-mediated control of sulfur metabolism in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1005052–5056. 10.1073/pnas.0531307100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández M., Kleerebezem M., Kuipers O. P., Siezen R. J., van Kranenburg R.(2002). Regulation of the metC-cysK operon, involved in sulfur metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 18482–90. 10.1128/JB.184.1.82-90.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontecave M., Atta M., Mulliez E.(2004). S-adenosylmethionine: nothing goes to waste. Trends Biochem Sci 29243–249. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs R. T., Grundy F. J., Henkin T. M.(2006). The S(MK) box is a new SAM-binding RNA for translational regulation of SAM synthetase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13226–233. 10.1038/nsmb1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray B. M., Turner M. E., Dillon H. C.(1982). Epidemiologic studies of Streptococcus pneumoniae in infants. the effects of season and age on pneumococcal acquisition and carriage in the first 24 months of life. Am J Epidemiol 116692–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy F. J., Henkin T. M.(2003). The T box and S box transcription termination control systems. Front Biosci J Virtual Libr 8d20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann A., Hakenbeck R., Brückner R.(2007). A new integrative reporter plasmid for Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 268217–224. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen W. T., Bootsma H. J., Estevão S., Hoogenboezem T., de Jong A., de Groot R., Kuipers O. P., Hermans P. W.(2008). CodY of Streptococcus pneumoniae: link between nutritional gene regulation and colonization. J Bacteriol 190590–601. 10.1128/JB.00917-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. E., Metcalf D. S., MacInnes J. I.(2003). A search for virulence genes of Haemophilus parasuis using differential display RT-PCR. Vet Microbiol 96189–202. 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00212-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullo M. F., Auger S., Dassa E., Danchin A., Martin-Verstraete I.(2004). The metNPQ operon of Bacillus subtilis encodes an ABC permease transporting methionine sulfoxide, D- and L-methionine. Res Microbiol 15580–86. 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispahani P., Slack R. C., Donald F. E., Weston V. C., Rutter N.(2004). Twenty year surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease in Nottingham: serogroups responsible and implications for immunisation. Arch Dis Child 89757–762. 10.1136/adc.2003.036921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelsen H., Madsen S. M., Vrang A., Hansen E. B., Johansen E.(1995). Cloning and partial characterization of regulated promoters from Lactococcus lactis Tn917-lacZ integrants with the new promoter probe vector, pAK80. Appl Environ Microbiol 612540–2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S., Sato Y., Kawashima M., Furumichi M., Tanabe M.(2014). Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res 42D199–205. 10.1093/nar/gkt1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian M., Mestecky J., Schrohenloher R. E.(1979). Pathogenic species of the genus Haemophilus and Streptococcus pneumoniae produce immunoglobulin A1 protease. Infect Immun 26143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva G. Y., Gelfand M. S.(2007). Transcriptional regulation of the methionine and cysteine transport and metabolism in streptococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett 276207–215. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanie J. A., Ng W. L., Kazmierczak K. M., Andrzejewski T. M., Davidsen T. M., Wayne K. J., Tettelin H., Glass J. I., Winkler M. E.(2007). Genome sequence of Avery's virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J Bacteriol 18938–51. 10.1128/JB.01148-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau G. W., Haataja S., Lonetto M., Kensit S. E., Marra A., Bryant A. P., McDevitt D., Morrison D. A., Holden D. W.(2001). A functional genomic analysis of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence. Mol Microbiol 40555–571. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestrate P., Delrue R. M., Danese I., Didembourg C., Taminiau B., Mertens P., De Bolle X., Tibor A., Tang C. M., Letesson J. J.(2000). Identification and characterization of in vivo attenuated mutants of Brucella melitensis. Mol Microbiol 38543–551. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks S. E., Oyston P. C. F.(2008). Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 1543609–3623. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares R., Urbanowski M. L., Stauffer G. V.(1992). Regulation of the Salmonella typhimurium metA gene by the metR protein and homocysteine. J Bacteriol 174390–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel B. A., Grundy F. J., Artsimovitch I., Henkin T. M.(2003). Transcription termination control of the S box system: direct measurement of S-adenosylmethionine by the leader RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1003083–3088. 10.1073/pnas.0630422100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J. M., Nourbakhsh F., Ford C. W., Holden D. W.(1997). Identification of Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes in a murine model of bacteraemia using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 26399–407. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5911966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin C., Gardiner G., Durand S., Masters M.(2002). The Escherichia coli metD locus encodes an ABC transporter which includes Abc (MetN), YaeE (MetI), and YaeC (MetQ). J Bacteriol 1845513–5517. 10.1128/JB.184.19.5513-5517.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves A. R., Ventura R., Mansour N., Shearman C., Gasson M. J., Maycock C., Ramos A., Santos H.(2002). Is the glycolytic flux in Lactococcus lactis primarily controlled by the redox charge? Kinetics of NAD(+) and NADH pools determined in vivo by 13C NMR. J Biol Chem 27728088–28098. 10.1074/jbc.M202573200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien K. L., Wolfson L. J., Watt J. P., Henkle E., Deloria-Knoll M., McCall N., Lee E., Mulholland K., Levine O. S., et al. (2009). Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374893–902. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N. J., John C. M., Reinders L. G., Gibson B. W., Apicella M. A., Griffiss J. M.(1990). Structural models for the cell surface lipooligosaccharides of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Haemophilus influenzae. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom 19731–745. 10.1002/bms.1200191112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanel S., Gakière B., Job D., Douce R.(1998). The specific features of methionine biosynthesis and metabolism in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 957805–7812. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov D. A., Vitreschak A. G., Mironov A. A., Gelfand M. S.(2004). Comparative genomics of the methionine metabolism in gram-positive bacteria: a variety of regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res 323340–3353. 10.1093/nar/gkh659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Girons I., Parsot C., Zakin M. M., Bârzu O., Cohen G. N.(1988). Methionine biosynthesis in Enterobacteriaceae: biochemical, regulatory, and evolutionary aspects. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 23S1–42. 10.3109/10409238809083374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell M. A.(1993). Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol 47597–626. 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J.(2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 31101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafeeq S., Kloosterman T. G., Kuipers O. P.(2011a). Transcriptional response of Streptococcus pneumoniae to Zn2+ limitation and the repressor/activator function of AdcR. Metallomics 3609–618. 10.1039/c1mt00030f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafeeq S., Yesilkaya H., Kloosterman T. G., Narayanan G., Wandel M., Andrew P. W., Kuipers O. P., Morrissey J. A.(2011b). The cop operon is required for copper homeostasis and contributes to virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 811255–1270. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafeeq S., Kloosterman T. G., Rajendran V., Kuipers O. P.(2012). Characterization of the ROK-family transcriptional regulator RokA of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Microbiology 1582917–2926. 10.1099/mic.0.062919-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafeeq S., Afzal M., Henriques-Normark B., Kuipers O. P.(2015). Transcriptional profiling of UlaR-regulated genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Genom Data 457–59. 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelver D., Rajagopal L., Harris T. O., Rubens C. E.(2003). MtaR, a regulator of methionine transport, is critical for survival of group B Streptococcus in vivo. J Bacteriol 1856592–6599. 10.1128/JB.185.22.6592-6599.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio B., Polard P., Ehrlich D. S., Renault P., Guédon E.(2005). Sulfur amino acid metabolism and its control in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. J Bacteriol 1873762–3778. 10.1128/JB.187.11.3762-3778.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio B., Gautier C., McGovern S., Ehrlich D. S., Renault P., Martin-Verstraete I., Guédon E.(2007). Control of methionine synthesis and uptake by MetR and homocysteine in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 1897032–7044. 10.1128/JB.00703-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titgemeyer F., Hillen W.(2002). Global control of sugar metabolism: a gram-positive solution. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 8259–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach H., Brot N.(1991). Regulation of methionine synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 51593–1597. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01905.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler W. C., Nahvi A., Sudarsan N., Barrick J. E., Breaker R. R.(2003). An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding S-adenosylmethionine. Nat Struct Biol 10701–707. 10.1038/nsb967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesilkaya H., Manco S., Kadioglu A., Terra V. S., Andrew P. W.(2008). The ability to utilize mucin affects the regulation of virulence gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 278231–235. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Data Bibliography

- 1.Lanie, J. A., Ng, W. L., Kazmierczak, K. M., Andrzejewski, T. M., Davidsen, T. M., Wayne, K. J., Tettelin, H., Glass, J. I. and Winkler, M. E. (2007). Genome sequence of Avery's virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. NCBI Nucleotide sequence database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NC_008533.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.