ABSTRACT

In the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans, phosphotransacetylase (Pta) and acetate kinase (Ack) convert pyruvate into acetate with the concomitant generation of ATP. The genes for this pathway are tightly regulated by multiple environmental and intracellular inputs, but the basis for differential expression of the genes for Pta and Ack in S. mutans had not been investigated. Here, we show that inactivation in S. mutans of ccpA or codY reduced the activity of the ackA promoter, whereas a ccpA mutant displayed elevated pta promoter activity. The interactions of CcpA with the promoter regions of both genes were observed using electrophoretic mobility shift and DNase protection assays. CodY bound to the ackA promoter region but only in the presence of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). DNase footprinting revealed that the upstream region of both genes contains two catabolite-responsive elements (cre1 and cre2) that can be bound by CcpA. Notably, the cre2 site of ackA overlaps with a CodY-binding site. The CcpA- and CodY-binding sites in the promoter region of both genes were further defined by site-directed mutagenesis. Some differences between the reported consensus CodY binding site and the region protected by S. mutans CodY were noted. Transcription of the pta and ackA genes in the ccpA mutant strain was markedly different at low pH relative to transcription at neutral pH. Thus, CcpA and CodY are direct regulators of transcription of ackA and pta in S. mutans that optimize acetate metabolism in response to carbohydrate, amino acid availability, and environmental pH.

IMPORTANCE The human dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans is remarkably adept at coping with extended periods of carbohydrate limitation during fasting periods. The phosphotransacetylase-acetate kinase (Pta-Ack) pathway in S. mutans modulates carbohydrate flux and fine-tunes the ability of the organisms to cope with stressors that are commonly encountered in the oral cavity. Here, we show that CcpA controls transcription of the pta and ackA genes via direct interaction with the promoter regions of both genes and that branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), particularly isoleucine, enhance the ability of CodY to bind to the promoter region of the ackA gene. A working model is proposed to explain how regulation of pta and ackA genes by these allosterically controlled regulatory proteins facilitates proper carbon flow and energy production, which are essential functions during infection and pathogenesis as carbohydrate and amino acid availability continually fluctuate.

KEYWORDS: acid tolerance, carbohydrate metabolism, dental caries, gene regulation, pyruvate

INTRODUCTION

Estimates from evolutionary genomic analysis of over 50 isolates of the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans from around the globe (1) are consistent with the bacterial composition of a small number of samples of dental calculus from ancient human fossils; both predict that S. mutans became a significant constituent of human oral biofilms around 3,000 to 10,000 years ago (2, 3), the time when humans adopted agriculture and the carbohydrate content of their diets began to increase (4–6). Thus, S. mutans evolved in close association with humans and their diets. Consequently, the organism is especially well adapted to persist during the extended periods of carbohydrate limitation associated with fasting by the host and to thrive when carbohydrate availability rapidly increases after ingestion of certain foods.

S. mutans can catabolize a large and diverse group of mono-, di-, tri-, and polysaccharides. The prioritization of catabolism of these carbohydrates by S. mutans is complex, involving multiple specific and global regulatory strategies (7). Carbohydrate catabolite repression (CCR) allows bacteria to first catabolize preferred carbohydrates when nonpreferred sources are present in significant quantities (8, 9). In many low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria, the dominant regulators of CCR are usually the histidine-containing protein (HPr) of the sugar:phosphotransferase system (PTS) and catabolite control protein A (CcpA). When cells are grown in the presence of certain preferred carbohydrates, increases in the pools of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (F-1,6-BP) and glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) can occur. FBP, and in some cases G6P, can activate an HPr kinase/phosphorylase that uses ATP to phosphorylate HPr at serine-46 (HPr-Ser46-P) (10, 11). HPr-Ser46-P forms a complex with CcpA, stimulating DNA binding to conserved catabolite-responsive elements (cre) that are located in the 5′ regions of target genes (12). To date, two consensus sequences for CcpA have been described: cre1 (see http://regprecise.lbl.gov/RegPrecise/) (12) and cre2 (TTTTYHWDHHWWTTTY) (13). Of note, CcpA can interact with other allosteric effectors and can regulate multiple genes and operons as a transcriptional repressor or activator. In transcriptomic studies of S. mutans, CcpA affected the transcription of numerous genes that encode products that enhance the pathogenic potential of S. mutans (14, 15). Specifically, 45 genes exhibited increased expression in a mutant lacking ccpA, relative to the wild-type strain, whereas 3 genes showed a reduction in expression when cells were cultured in tryptone-vitamin (TV)-base medium (16) supplemented with 25 mM glucose (15). The majority of the genes that were upregulated were involved in carbohydrate uptake and control of carbon metabolism. The three downregulated genes were sacB, amyA, and ccpA itself; ccpA had been deleted and replaced with an antibiotic resistance marker. Importantly, whereas CcpA clearly plays important roles in global control of gene expression, there are almost no instances where inactivation of ccpA in S. mutans alleviates catabolite repression (17). Instead, the ManL (EIIABman) protein of the PTS, the predominant permease for internalization of glucose, as well as other PTS permeases (e.g., the EII permease for sucrose), dominantly prioritizes carbohydrate uptake and metabolism. Interestingly, CcpA is a negative regulator of manL expression, and as a result, ccpA mutants often have enhanced sensitivity to CCR by glucose, presumably as a result of increases in the amount of ManL protein in cells.

A second global regulator of gene expression that is conserved in many low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria and that allows the organisms to rapidly adapt to changes in nutrient availability is CodY (7, 18–22). CodY can repress or activate gene expression by direct interaction with “CodY boxes” (proposed consensus AATTTTCNGAAAATT) located in the promoter regions of target genes (23), competing with transcriptional activators and/or binding of RNA polymerase (RNAP) (23–26). Moreover, CodY plays a key role in physiologic homeostasis by sensing fluctuations in intracellular pools of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs; l-isoleucine, l-leucine, and l-valine) (18, 27, 28). For example, in S. mutans, CodY acts as a repressor of the ilvE gene (SMU.1203c), encoding an aminotransferase important for catalyzing a late step in generation of BCAAs, and the addition of isoleucine enhanced the DNA binding affinity for CodY to the ilvE promoter in vitro (29). However, ilvE gene expression was elevated in a ccpA mutant, suggesting competition between CcpA and CodY for regulation of ilvE.

Of relevance here, expression of the pta gene (SMU.1043) in a ccpA mutant that was cultivated to mid-exponential phase in a TV-base medium with glucose as the carbohydrate source was increased 2.1-fold over the wild-type strain, as determined by RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) (15). Recently, our group revealed a global role for the phosphotransacetylase (Pta)-acetate kinase (Ack) pathway of S. mutans in regulating carbohydrate metabolism and in the ability of the organisms to cope with stressors that are commonly encountered in the oral cavity, particularly oxidative stress (30). The Pta-Ack pathway involves Ack-dependent generation of ATP and acetate from acetyl phosphate (AcP), which can be produced from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and phosphate by Pta. Pta-Ack also shunts carbon away from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle during overflow metabolism. Additionally, increased (p)ppGpp accumulation occurs in pta and ackA mutants, compared to the wild-type strain, and was correlated with AcP and ATP pools.

S. mutans is considered to be well adapted to the “feast-and-famine” existence in the human oral cavity (31). S. mutans produces mostly lactate when presented with excess carbohydrate under relatively anaerobic conditions, whereas the organisms shift to acetate production under certain other conditions (e.g., carbohydrate limitation and aerobic growth), yielding an additional ATP. However, it is also critical to manage carbon flow to balance the generation of ATP with maintenance of NAD+/NADH ratios, as well as to provide sufficient carbon for amino acid biosynthesis. Thus, monitoring carbohydrate availability and pools of amino acids is an essential activity for persistence and pathogenesis, and the Pta-Ack pathway is critical to achieving the proper balance of carbon flow in S. mutans and many other bacteria. Here, we explore the regulatory pathways that integrate information on nutrient availability and environmental inputs to control transcription of pta and ackA. The results clearly show that proper regulation of ackA and pta is crucial for physiological homeostasis and is dominantly coordinated by the activities of CcpA and CodY.

RESULTS

Δpta and Δpta ackA mutants require leucine and valine for optimal growth.

Pyruvate is utilized as a substrate for multiple pathways in S. mutans, including for acetate and ATP production via the Pta-Ack pathway and for the biosynthesis of BCAAs. In particular, the ilv and leu genes encode the biosynthetic enzymes to convert pyruvate to BCAAs (7). Notably, we showed previously that ilvE (SMU.1203c) expression was downregulated in an ackA mutant, which accumulates AcP levels at much higher levels than the wild-type strain (30). To investigate the interrelationship of the Pta-Ack and BCAA biosynthetic pathways further, we monitored growth of pta and ackA mutant strains in FMC medium with modified BCAA composition (Fig. 1). None of the mutant strains had their growth affected by the removal of individual BCAAs (data not shown). When the strains were grown in medium supplemented only with isoleucine (absent leucine and valine), we observed that the ackA mutant exhibited a slightly lower growth rate (doubling time, 286 min ± 15 min; P < 0.01), whereas the Δpta or Δpta ackA strains displayed no growth or severely impaired growth, respectively (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). However, no statistically significant differences in growth rates were observed when all mutant strains were grown in medium lacking isoleucine and valine (Fig. 1B). Finally, all mutant strains grown in medium lacking both isoleucine and leucine behaved similarly to strains growing in medium lacking isoleucine and valine (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Growth characteristics of S. mutans UA159 and its derivatives in FMC supplemented with individual branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). The wild-type (◆), ΔackA (■), Δpta (▲), and Δpta ackA (×) strains were grown in triplicate to mid-exponential phase in BHI medium and diluted 1:100 into fresh FMC medium supplemented with isoleucine (A), leucine (B), or valine (C) (see Materials and Methods). Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was monitored every 30 min at 37°C using the Bioscreen C Lab system. The data presented are the average values for at least four biological replicates performed in triplicate.

CcpA and CodY regulate ackA and pta.

RNA-Seq data generated by members of our group revealed that expression of ackA and pta in a ΔccpA mutant was increased ∼1.7- and ∼2.1-fold over the wild-type strain, respectively, when the cells were grown in TV medium supplemented with glucose (15). By searching consensus sequences for a cre site available in RegPrecise using the Clustal Omega program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/), a potential cre1 motif was identified 28 bp and 51 bp, respectively, upstream of the translational start sites of ackA and pta (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Also, a potential cre2 motif was identified 152 bp upstream of the ackA initiation codon and a CodY box was identified 116 bp upstream of the ackA start site.

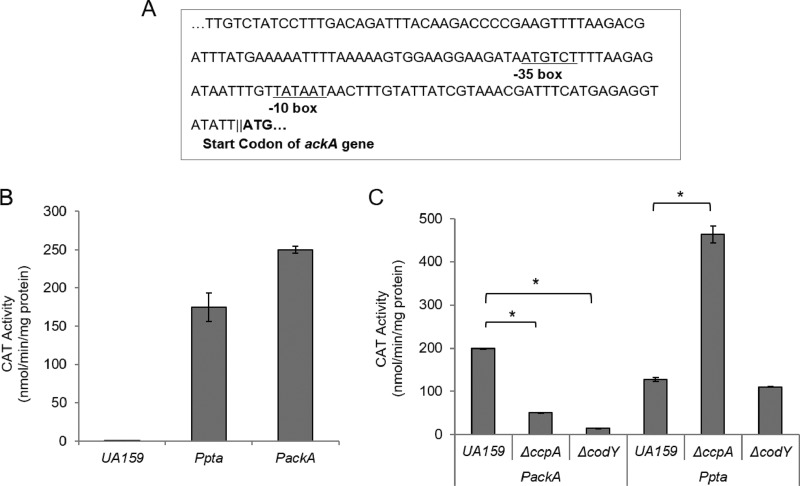

The putative promoter of pta in S. mutans has been predicted (32). Using the BPROM software (Softberry, Mount Kisco, NY), one potential promoter region for ackA, located at −46 to −69 with respect to the start codon for ackA, was identified (Fig. 2A). To determine whether a functional promoter was located 5′ to the ackA gene, a 323-bp fragment directly upstream of the start site of ackA was directionally cloned behind a promoterless cat gene in the integration vector pJL105 (33). The construct was used to transform S. mutans strain UA159. When grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium, the construct in the wild-type genetic background expressed 249 ± 4.5 units of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity (Fig. 2B), indicating that the predicted region included a promoter capable of driving transcription of ackA.

FIG 2.

(A) The promoter predicted by BPROM (see the text) to drive transcription of ackA. The −35 and −10 region sequences for the putative promoters are underlined. Bold letters indicate the predicted start codon (ATG) of ackA. (B) Promoter-cat fusion activity from the promoter region of ackA. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase in BHI broth at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and CAT activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. UA159, a negative control; Ppta, a positive control. (C) Promoter-cat fusion activity from the promoter region of ackA or pta in the wild-type, ΔccpA, or ΔcodY background strains. *, data differ from the wild-type genetic background at P < 0.01.

To investigate whether CcpA and CodY could regulate transcription of ackA or pta, promoter fusions of ackA or pta to a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene were introduced into S. mutans strains harboring deletions of ccpA or codY (32) (see Table 1). Interestingly, in cells growing in BHI broth, CAT activity of the ackA promoter fusion was reduced in the ΔccpA and ΔcodY strains (50.1 ± 0.6 and 14.1 ± 0.4 units, respectively) compared to CAT activity in the wild-type genetic background (199 ± 0.9 units) (Fig. 2C). In contrast, no change was found in promoter activity in the ΔcodY strain, but CAT activity of the pta promoter fusion in the ΔccpA strain showed a 3.6-fold increase (463 ± 20 units) over that measured in the wild-type strain (128 ± 5.1 units). Importantly, no differences in the patterns of gene expression were observed when cells were cultured in FMC; in both cases, pta and ackA gene expression was markedly changed (data not shown). Thus, the effects of loss of CcpA or CodY were consistent between cells grown in BHI and those grown in FMC. Differences were noted between this study and a previous report in which RNA-Seq was performed on cells cultivated in TV-glucose medium (15), possibly arising from differences in composition or accessibility of amino acids in BHI/FMC versus TV-base medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain and plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus mutans | ||

| UA159 | Wild type | Laboratory stock |

| ΔackA | ΔackA::NPKmr | 30 |

| Δpta | Δpta::NPKmr | 32 |

| ΔptaE | Δpta::NPErmr | 32 |

| ΔptaE ΔackA | Δpta ΔackA::NPKmr Ermr | 30 |

| ΔccpA | ΔccpA::NPErmr | 48 |

| ΔcodY | ΔcodY::NPTetr | 25 |

| WT::PackA-cat | cat gene fusion to putative ackA promoter, Spr Kmr | This study |

| ΔccpA::PackA-cat | ΔccpA carrying cat gene fusion to ackA promoter | This study |

| ΔcodY::PackA-cat | ΔcodY carrying cat gene fusion to ackA promoter | This study |

| WT::Ppta-cat | cat gene fusion to putative pta promoter, Spr Kmr | 32 |

| ΔccpA::Ppta-cat | ΔccpA carrying cat gene fusion to pta promoter | This study |

| ΔcodY::Ppta-cat | ΔcodY carrying cat gene fusion to pta promoter | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| His6-CcpA | ccpA coding region cloned into pQE30, Ampr | 14 |

| His6-CodY | codY coding region cloned into pET-30a, Ampr | This study |

| Δa-cre1 | Deletion of cre1 sequence in the region upstream of ackA | This study |

| Δa-cre2 | Deletion of cre2 sequence in the region upstream of ackA | This study |

| Δa-cre1_2 | Deletion of cre1 and cre2 sequences in the region upstream of ackA | This study |

| Δp-cre1 | Deletion of cre1 sequence in the region upstream of pta | This study |

| Δp-cre2 | Deletion of cre2 sequence in the region upstream of pta | This study |

| Δp-cre1_2 | Deletion of cre1 and cre2 sequences in the region upstream of pta | This study |

CcpA and CodY binding to the ackA and pta promoter regions.

To determine whether CcpA or CodY could bind to the ackA or pta promoter regions, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed (Fig. 3). Recombinant His6-tagged CcpA or CodY proteins were purified under denaturing conditions and allowed to renature as recommended by the supplier. The 323-bp ackA or 316-bp pta promoter regions containing potential CcpA and CodY binding sites were amplified with end-labeled (biotinylated) primers and used as the substrate. As a positive control, CcpA was shown to bind efficiently to a 320-bp probe from the 5′ region of the ilvE gene of S. mutans (Fig. 3, lane 1). In the presence of CcpA, a shift was also detected in all lanes containing the labeled ackA and pta fragments, indicating that the promoter regions of pta and ackA are capable of being bound by CcpA (Fig. 3, lanes 3 to 5 and 7 to 9, respectively). However, no shift with labeled ackA or pta probes was detected in the presence of CodY using the conditions detailed above (data not shown).

FIG 3.

In vitro binding of CcpA to the promoter of ackA or pta. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) of CcpA binding to the putative promoter region of ackA or pta. Biotin-labeled promoter regions of ackA and pta (10 fmol) were used as a probe and incubated with purified His-CcpA protein (0, 50, 100, and 200 pmol) at 37°C for 1 h. The promoter region of ilvE was used as a positive control for an individual binding assay in lane 1. GTP and BCAAs were added as a coeffector. The EMSA mixtures containing the promoter region of ackA are in lanes 2 to 5; those with pta are in lanes 6 to 9. The positions of the shifted product (CcpA-bound) or unbound DNA (free probe) are indicated to the left of the figure.

Interaction between CodY and the ackA promoter requires isoleucine.

Recent studies demonstrated that efficient binding of CodY to target DNAs can require GTP or BCAAs (18, 19). In fact, the addition of BCAAs appeared to enhance the affinity of CodY for the ackA promoter region of Bacillus subtilis, but this was not the case for GTP alone (19). Consistent with the finding that GTP does not appear to modulate the DNA binding activity of the S. mutans CodY protein (29), DNA-protein complex shifts between CodY and the 233-bp codY upstream region, which was used as a positive control, and CodY and the ackA probe were clearly enhanced by BCAAs but not by GTP alone (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 5 and lanes 9 and 10, respectively). However, no interaction between CodY and the pta promoter was observed, regardless of whether GTP and BCAAs or only BCAAs were added (Fig. 4A, lanes 12 to 15).

FIG 4.

EMSAs of CodY binding with the promoter of ackA or pta genes. (A) CodY binding to DNA fragments of the codY, ackA, and pta promoter was examined in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 5 mM GTP or 10 mM BCAAs. (B) Ten femtomoles of biotin-labeled PackA was used in each reaction mixture with 10 mM individual BCAAs and 50 pmol of His6-CodY protein. The arrows indicate the migration of either the complex of CodY-DNA (CodY-bound) or unbound DNA (free probe). In panel A, samples 1 to 5 and 6 to 15 are from separate replicates run on different gels.

BCAAs have been known to be effector molecules for CodY binding in S. mutans, with isoleucine being the most effective allosteric effector at enhancing protein-DNA interaction between CodY and the ilvE promoter region (18). To determine whether isoleucine could be the stronger of the BCAA signals for CodY binding to the ackA promoter region, individual BCAAs were used in the binding assays for CodY with the ackA promoter. When leucine or valine was added to the binding reaction, no shift was detected (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4). However, in the presence of isoleucine alone, an enhancement in the shifting of the probe, equivalent to that seen when all three BCAAs were present, was evident (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6). Collectively, these data demonstrate that CodY positively regulates ackA expression by direct interaction with the promoter region when BCAAs, and in particular isoleucine, are present, with no evidence of CodY binding being influenced by GTP.

Identification and characterization of binding sites for CcpA and CodY.

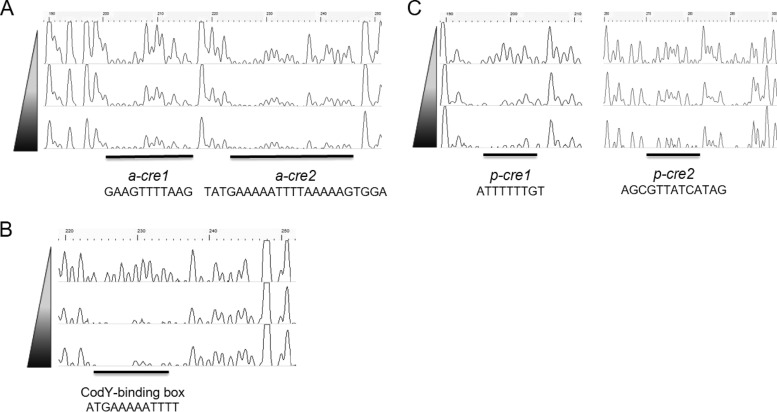

The mobility shift assays showed that CcpA and CodY could bind to the regions upstream of the ackA and/or pta genes. To determine sequences for binding of these proteins, DNase footprinting assays were performed using 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) fluorescence labeling capillary electrophoresis under the same conditions as used for EMSAs. A 510-bp or 476-bp biotin-/6-FAM-labeled purified PCR product that contained the ackA or pta promoter regions, respectively, was used as target DNA. The analysis of footprinting revealed that CcpA protected two pseudopalindromic regions, designated a-cre1 (GAAGTTTTAAG) and a-cre2 (TATGAAAAATTTTAAAAAGTGGA), beginning 118 and 101 bp upstream of the ackA start codon, respectively (Fig. 5A). The two cre sites were located upstream of the predicted −35 and −10 elements and were separated from one another by 6 bp. CodY also protected a single region in the ackA promoter region (ATGAAAAATTTT) (Fig. 5B). However, the region protected by CodY was different than the predicted site, so it should be considered that the current consensus sequence assigned to CodY may not accurately predict CodY binding in S. mutans. Notably, the region bound by CodY was within the a-cre2 sequence, so CodY binding at this site may occur when conditions are less favorable for binding of CcpA, and vice versa.

FIG 5.

DNase I footprinting assays of CcpA and CodY binding. Solid bars and labels depict the regions protected from DNase I digestion upstream of ackA by either CcpA (A) or CodY (B) or upstream of pta by CcpA (C). The electropherograms represent control DNA with no protein bound on top and footprints with increasing concentrations (10 and 20 μg) of His-tagged proteins (CcpA and CodY) in the middle and bottom of each panel.

When the promoter region of pta was incubated with purified CcpA, two protected regions beginning 118 and 46 bp upstream of the pta start codon were observed and were designated p-cre1 (ATTTTTTGT) and p-cre2 (AGCGTTATCATAG), respectively (Fig. 5C). While p-cre1 resides upstream of the −35 and −10 elements, p-cre2 overlaps the −10 element (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These findings indicate that CcpA likely represses pta transcription by preventing binding of RNA polymerase.

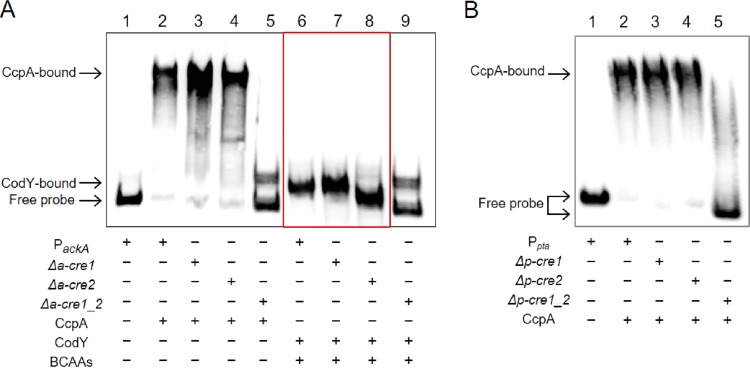

Deletion of the cre sites impedes binding of CcpA and CodY.

To explore whether the protected regions could be targets for CcpA or CodY binding in vitro, the individual regions were deleted from the full-length probes using the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit, as outlined in Materials and Methods. In this approach, the same PCR fragments used in the footprinting assays were cloned into a vector and mutagenesis was performed on these constructs. When the PCR products derived from the plasmid carrying the ackA promoter region lacking either a-cre1 or a-cre2 were used in mobility shift assays, a shift was clearly detected in the lanes containing the individual mutated DNAs (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, deletion of both regions resulted in no shift with the CcpA protein (Fig. 6A, lane 5).

FIG 6.

Effects of deletion of binding regions for CcpA and CodY assessed by EMSA. (A) This panel is a composite derived from two separate replicates and gels. In particular, the red box indicates that the portion of the image containing lanes 6, 7, and 8 was spliced into the figure for labeling purposes and to allow side-by-side comparison of the results. CcpA or CodY proteins were tested for the ability to induce a mobility shift with biotin-labeled DNA fragments of the ackA promoter carrying cre-deleted (a-cre1 and a-cre2) sequences. CodY binding assays were conducted in the presence of BCAAs. Lanes 1 and 2, ackA promoter without or with CcpA, respectively; lane 3, a-cre1 deletion; lane 4, a-cre2 deletion; lane 5, both deletions. (B) EMSA of CcpA binding to cre sites in the pta promoter region was performed with the pta promoter carrying wild-type and mutated (p-cre1 and p-cre2) DNA fragments. Lanes 1 and 2, the wild-type pta promoter as a negative or positive control, respectively; lane 3, p-cre1 deletion; lane 4, p-cre2 deletion; lane 5, both deletions.

When the DNA fragment lacking the a-cre1 sequence was used, there was no difference in the proportion of DNA shifted with CodY compared to the wild-type DNA (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 7). However, in the presence of the DNA fragment lacking the a-cre2 sequence, which contains the CodY-binding site, no CodY binding could be observed, which is also what was seen with the construct carrying the double deletion (Fig. 6A, lanes 8 and 9). These results provide further support that the a-cre2 sequence serves as a primary binding motif for the S. mutans CodY protein.

CcpA was able to bind to the DNA fragments lacking either the p-cre1 or p-cre2 sequences, the same as when the control DNA was used (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 to 4). In contrast to the results with the single deletions, no shift corresponding to the CcpA-DNA complex was detected when the DNA fragment lacking both the p-cre1 and p-cre2 sequences was used in this binding reaction (Fig. 6B, lane 5). These data confirm that the cre sequences mapped in the footprinting assays are indeed CcpA binding sites.

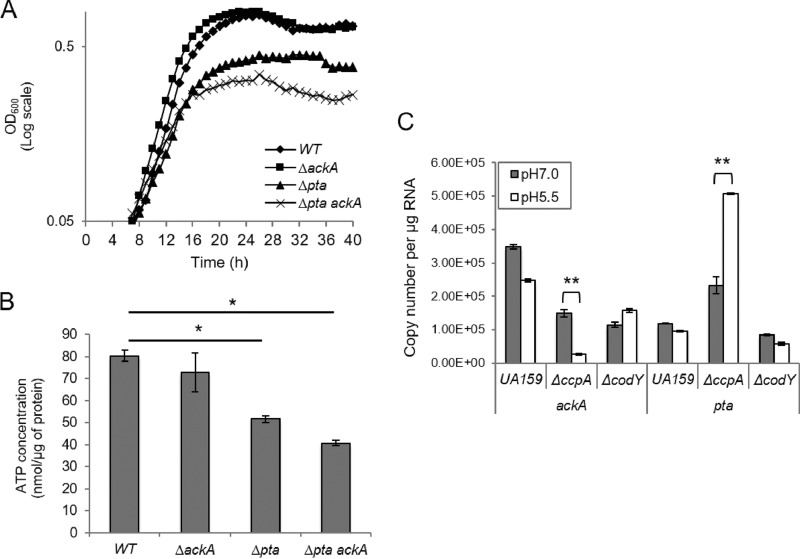

pH-dependent regulation of ackA and pta.

Aciduricity, the ability to maintain metabolic activity and to grow at low pH values, is generally recognized as a requirement for initiation and progression of dental caries pathogens, including S. mutans (34, 35). We examined whether mutations in the genes for the Pta-Ack pathway influenced the aciduricity of S. mutans. When cells were grown at pH 5.5, the Δpta and Δpta ackA mutants displayed lower final yields (P < 0.05; final optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.38 ± 0.12 and 0.27 ± 0.06, respectively), whereas the ackA single mutant (final OD600 of 0.65 ± 0.09) strain grew as well as the wild-type strain (final OD600 of 0.66 ± 0.15) (Fig. 7A). We explored whether there was a connection between the growth phenotypes and ATP production by measuring ATP levels in cells that had been grown in FMC medium that was acidified to pH 5.5 (36, 37). Strains harboring mutations in the pta gene had reduced ATP levels, 51.7 ± 1.5 nmol μg protein−1 for the single mutant and 40.1 ± 1.1 nmol μg protein−1, for the strains lacking Pta and AckA, respectively (P < 0.05). Low pH did not affect ATP pools in the ackA single mutant (72.8 ± 8.7 nmol μg protein−1) compared to that of the parental strain (80.4 ± 2.5 nmol μg protein−1) (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

(A) Growth of the wild-type (WT), ΔackA, Δpta, and Δpta ackA strains was monitored in medium to which HCl was added to lower the pH to 5.5. Data are expressed as the means of the results determined with triplicate wells for three biological replicates (individual colonies). (B) Cellular ATP levels of the wild-type strain were compared with those in the ΔackA, Δpta, and Δpta/ackA strains using cells grown to early exponential phase in FMC medium at pH 5.5 (see details in Materials and Methods). (C) Measurement of the copy number of ackA and pta transcripts in the wild-type, ΔccpA, and ΔcodY backgrounds. S. mutans wild-type and mutant strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in FMC medium supplemented with 20 mM glucose alone (gray bars) or with 20 mM glucose plus HCl to lower the pH of the medium to 5.5 (white bars). qRT-PCR data are reported as the copies of the target RNA derived from 1 μg of input RNA after normalization to the 16S rRNA in the same samples. All values shown are the means ± standard deviations from triplicates of three biological replicates. *, differs from the wild-type genetic background at P < 0.05 (Student's t test). **, data differ from the strain grown under neutral-pH conditions at P < 0.01.

Previously, our lab demonstrated that loss of ccpA in S. mutans results in enhanced acid resistance (14), presumably due to increases in expression of PTS permeases, as has been noted to occur during acid adaptation by Streptococcus sobrinus (38). In addition, regulation of ilvE by CodY also shows a dependence on pH in S. mutans (18), whereas regulation of ilvE by CcpA did not show pH responsiveness. We therefore examined if control of expression of pta or ackA by CcpA or CodY was sensitive to environmental pH. Specifically, expression of pta and ackA was monitored in the codY and ccpA deletion mutants using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). When cells were grown in BHI medium that had been acidified to pH 5.5, transcription of the ackA gene was reduced in a mutant lacking CcpA, whereas pta transcription was consistently higher than in the wild-type background, albeit not significantly so (data not shown). The gene expression patterns in response to low pH were also observed when the cells were grown in chemically defined medium. The ccpA mutant had up to 5-fold-lower ackA mRNA levels when grown in FMC at pH 5.5 (1.50E+5 ± 1.19E+4 at pH 7; 2.78E+4 ± 2.28E+3 at pH 5.5; P < 0.01), whereas pta mRNA levels were increased 2-fold compared to that of the mutant strain grown at an initial pH of 7 (2.33E+5 ± 2.56E+4 at pH 7; 5.07E+5 ± 2.54E+3 at pH 5.5; P < 0.01) (Fig. 7C). Under the same conditions, however, transcription of both genes in the mutant lacking codY showed no difference between acidic and neutral pH growth conditions. Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that CcpA modulates acid tolerance of S. mutans by controlling the expression of the pta and ackA genes, possibly to ensure an adequate supply of ATP to fuel growth and extrusion of protons by the F1Fo-ATPase.

DISCUSSION

Through intake and fermentation of carbohydrates and the controlled shunting of pyruvate into a partial TCA cycle, S. mutans balances energy production with maintenance of NAD+/NADH ratios to ensure sufficient synthesis of precursors for essential cellular processes. During fasting periods, the microbiota of the oral cavity must contend with limited access to free amino acids and must scavenge a variety of carbohydrates from host secretions, sloughed cells, and members of the oral flora. Under these conditions, lactate is not the primary fermentation product of streptococci, and carbohydrates are routed through other pathways to optimize energy generation. A particularly important pathway in oral ecology involves the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetate to generate ATP via the sequential activities of the Pta and Ack enzymes. The process of governing the flow of carbon is particularly critical for maintaining redox balances and producing ATP in bacteria lacking an electron transport system, including S. mutans (7). In addition to tightly regulated redox and carbon flow, the expression of genes encoding products for ATP-dependent transporters, energy metabolism, and transcriptional regulators in S. mutans is highly dependent on environmental inputs, including pH (39). This bacterium has thus developed complicated regulatory systems to maintain balanced carbon metabolism in response to environmental conditions. The findings presented here reveal that CcpA and CodY directly regulate transcription of the pta and ackA genes in S. mutans. This study also provides novel insights into how the regulation of the Pta-Ack pathway by these two regulators is integrated with tolerance of acidic conditions.

A major finding of this study is that the Pta-Ack pathway is transcriptionally regulated by the allosterically controlled regulatory proteins CcpA and CodY. In studies using microarrays or RNA-Seq, the expression of the pta and ackA genes of S. mutans was altered in a strain lacking CcpA compared to the parental strain, UA159 (14, 15). Further, a possible consensus sequence for CodY binding was predicted in the region upstream of the ackA gene; however, no difference in gene expression was observed in the codY mutant background (25). Here, bioinformatic identification of potential consensus sequences for CcpA and CodY-binding sites in the promoter regions of pta and ackA genes in S. mutans was validated by in vivo and in vitro experiments showing that CcpA bound to the promoter regions of both ackA and pta, and that CodY interacted only with the ackA promoter region in a specific manner. CcpA was also shown to function as an activator of the ackA gene but a repressor of the pta gene. Interestingly, there was a lack of similarity between the CcpA binding sites in the pta and ackA promoter regions. Thus, it can be hypothesized that transcription of the ackA and pta genes is regulated by CcpA under different environmental or physiologic conditions, with the binding of CcpA to its target sequences being modified by certain allosteric regulators and possibly by other DNA binding proteins that may compete for overlapping cis elements.

Our data also support that CodY of S. mutans is able to function as both a repressor and activator of gene expression, depending on the target gene and likely on environmental conditions that influence bioenergetics and amino acid pools. A dual function for CodY would be consistent with observations made with the B. subtilis CodY protein, which show that, in addition to negatively regulating certain genes, CodY is a positive regulator of ackA in the presence of BCAAs and GTP (19). However, DNA binding of CodY of S. mutans is not responsive to GTP, unlike what has been seen with other CodY orthologs (24, 27, 28). Rather, the binding of CodY of S. mutans to the targets of interest was most substantially influenced by isoleucine. Since the strains with mutations in the pta and ackA genes grew slowly in defined medium supplemented with excess isoleucine, but not other BCAAs, we postulate that CodY could be responsible, at least in part, for the growth inhibition of these mutants. In S. mutans, inactivation of codY affects, directly and indirectly, the expression of 79 genes. Among these, 50 genes encoding products involved in amino acid biosynthesis were upregulated, whereas 29 genes that included genes encoding proteins involved in amino acid uptake and ABC transporters were downregulated (25), also supporting a dual role as activator and repressor. Because the pta or ackA mutants showed no differences in the activity of PTS-dependent transport of glucose (data not shown) and the growth-defective phenotype of the codY mutant was evident in medium with isoleucine alone, but not other BCAAs, inhibition of growth by isoleucine in FMC is likely due to repression by CodY of essential genes.

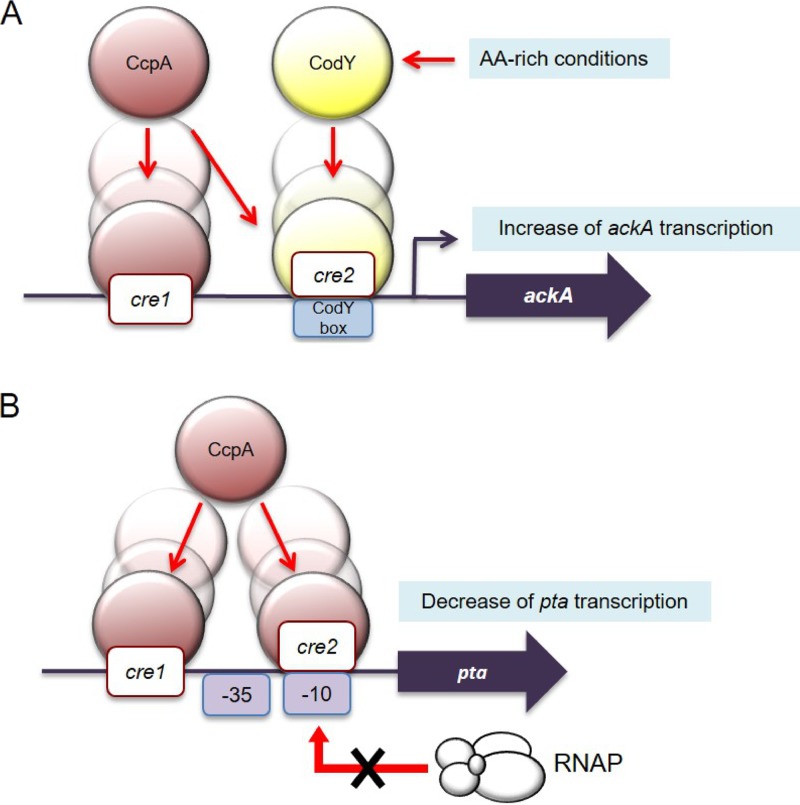

Based on current knowledge, one would predict that binding of CcpA to its target sequences is optimal when F-1,6-BP levels are elevated, i.e., when carbohydrate flow through glycolysis is elevated. On the other hand, binding of CodY should be highest when pools of isoleucine and possibly other BCAAs reach some critical threshold. Interestingly, regulation of ackA expression by CcpA and CodY appears synergistic in that both proteins can activate transcription of ackA. Based on the observations made in this study, a working model (Fig. 8) has been developed that illustrates how binding of the global regulators CcpA and CodY may occur under different physiologic conditions to facilitate increased transcription of the ackA gene (19). During growth under aerobic conditions with sufficient glucose, the cells route a larger proportion of carbon to generate acetate and provide the cells with an additional ATP, compared with production of lactate. As described by our model, positive regulation of ackA in S. mutans by CcpA could be triggered by an accumulation of early intermediates in the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathways, whereas CodY would respond if sufficient pools of BCAAs were available, with oxygen playing a key role in modulating the physiologic status of the cells (40, 41). The finding that the effect of loss of CcpA on ackA is dependent on the composition of the growth medium (TV-glucose in the RNA-Seq study compared with BHI or FMC in this study) adds further support to the notion that inputs from the environment influence intracellular metabolite pools (e.g., glycolytic intermediates and BCAAs) to dictate the binding behaviors of these two primary regulators of ackA.

FIG 8.

Working model for the CcpA- or CodY-mediated regulation in transcription of ackA or pta genes. (A) Upon transcriptional regulation, CcpA binds to two possible cre sites of the ackA promoter, while CodY binds to a CodY box that overlaps the cre2 site of ackA. While CcpA-dependent regulation is responsive to acidic conditions, CodY interaction appears to depend solely on pools of certain amino acids. In particular, CodY binding is enhanced in the presence of BCAAs, especially isoleucine; thus, CodY activation is diminished as the levels of BCAAs decrease. (B) When glycolytic intermediates accumulate, CcpA can negatively regulate pta expression by direct binding to the two possible cre sites in the promoter region of pta. Of note, cre2 overlaps the −10 element for RNAP.

In contrast, when the environment becomes acidified due to rapid carbohydrate metabolism, CcpA can function as a transcriptional repressor of the pta gene, apparently by binding in a way that interferes with the ability of RNA polymerase to interact with the promoter; the transcript levels of pta are substantially increased in a ccpA mutant strain. However, it should be emphasized that the strains with mutations in the pta gene displayed sensitivity to low pH and diminished ATP pools, consistent with the importance of the proton-pumping ATPase to acid tolerance in S. mutans and the increased energy devoted to maintenance versus growth at low pH (42). Thus, regulation by CcpA and CodY is important for fine-tuning transcription of the ackA and pta genes under acidic conditions created by carbohydrate fermentation in order to balance energy generation with anabolic processes. In all cases, we cannot exclude that as-yet-to-be-identified allosteric modulators of CcpA or CodY could alter whether they behave as repressors or activators of these pathways.

Conclusions.

In the oral cavity, it is essential for the persistence and virulence of S. mutans that the organism can rapidly adapt to fluctuations in carbon and amino acid source and availability and integrate these responses with the adaptation to the stresses that are created by carbohydrate metabolism. Clearly, from data presented here, CcpA- and CodY-dependent regulation of pta and ackA facilitates these adaptations by allowing for continuous monitoring of carbohydrate flow through the glycolytic pathway (CcpA) and BCAA pools (CodY), respectively. The control of acetate metabolism by CcpA and CodY, directly by modulation of expression of the pta and ackA genes, and the influence of acetate metabolism on AcP and ATP levels (30) represent a critically important circuit for S. mutans to coordinate stress tolerance with optimization of nutrient utilization (30); e.g., we have shown a clear connection between acetate metabolism and ppGpp production. Collectively, this study provides new insights into how the transcriptional regulation of the Pta-Ack pathway by CcpA and CodY exerts a positive effect on genetics and physiology of S. mutans that affects its persistence and virulence attributes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were grown using LB medium and Streptococcus mutans UA159, and its derivatives were grown using brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). Growth media were supplemented with spectinomycin (50 μg/ml for E. coli or 1 mg/ml for S. mutans), erythromycin (300 μg/ml for E. coli or 10 μg/ml for S. mutans), or kanamycin (50 μg/ml for E. coli or 1 mg/ml for S. mutans) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), when needed. Bacterial growth was monitored in the chemically defined medium FMC (43) formulated with 25 mM glucose as the carbohydrate source. Briefly, overnight cultures in BHI broth were diluted 1:50 into fresh BHI broth and grown to mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.5) at 37°C in a 5% CO2, aerobic atmosphere. Mid-exponential-phase cultures were then diluted 1:100 into fresh FMC medium supplemented with combinations of isoleucine, leucine, and/or valine, or with HCl to lower the pH of the medium to 5.5, where indicated. The OD600 of cells growing at 37°C was measured every 30 min using a Bioscreen C Lab system (Helsinki, Finland) with shaking for 10 s before the data points were collected. Sterile mineral oil (0.05 ml) was overlaid on the cultures to create a less aerobic environment.

Strain construction.

A fusion of the ackA promoter was created to a staphylococcal chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) reporter gene using an approach detailed by Zeng et al. (33). Briefly, a 197-bp fragment directly upstream of the ackA translational start site was amplified using custom primers (Table 2) and then cloned into the pJL105 integration vector (33), which carries the cat gene lacking a promoter and ribosome binding site (RBS). The resulting construct was transformed into S. mutans to establish the promoter-cat fusion in single copy in the chromosome by double crossover homologous recombination, with the mtlA-phnA genes serving as the integration site. To generate a His6-tagged CodY protein, the S. mutans codY gene was amplified with gene-specific primers carrying restriction enzyme sites (Table 2). The PCR product was digested with NcoI and XhoI (New England BioLabs) and cloned into pET-30a-c(+) (Novagen), which has an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T7 promoter and RBS for protein expression. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli DE3. Proper fusion of the His6 tag and the correct sequence of the codY gene in the plasmid were confirmed by sequence analysis of a PCR product obtained using plasmid-specific primers.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | Description |

|---|---|---|

| EMSA-Ppta-FP | TCTGGTAAATATGCACATACAAGTT | EMSA |

| EMSA-Ppta-RP | /5′-Bio/ATGTAAATACCCCTATCTAA | EMSA |

| Foot-Ppta-FP | /5′-6FAM/TCTGGTAAATATGCACATACAAGTT | DNase footprinting |

| DN-Ppta-RP | /5′-Bio/CAGTCGCATCTCCTAAA | DNase footprinting |

| EMSA-PackA-FP | AGCGCCAGTGGATCTTTTAAC | EMSA |

| EMSA-PackA-RP | /5′-Bio/AATATACCTCTCATGAAATC | EMSA |

| Foot-PackA-FP | /5′-6FAM/AGCGCCAGTGGATCTTTTAAC | DNase footprinting |

| DN-PackA-RP | /5′-Bio/CTGCAGTATGGTCTTTAATA | DNase footprinting |

| Delta-pta-Cre I RP | CTTTTGTGGATCCTTTTTCC | p-cre1 deletion |

| Delta-pta-Cre I FP | GGCAGTGAAGAGCTTGTC | p-cre1 deletion |

| Delta-pta-Cre II RP | ATTTACAAAAACATTAGATAGGGG | p-cre2 deletion |

| Delta-pta-Cre II FP | ATCAAGGTCTTCTGTCAAG | p-cre2 deletion |

| Delta-ackA-Cre I RP | ACGATTTATGAAAAATTTTAAAAAGTG | a-cre1 deletion |

| Delta-ackA-Cre I FP | GGGGTCTTGTAAATCTGTC | a-cre1 deletion |

| Delta-ackA-Cre II RP | AGGAAGATAATGTCTTTTAAGAG | a-cre2 deletion |

| Delta-ackA-Cre II FP | AATCGTCTTAAAACTTCGG | a-cre2 deletion |

| EMSA-PcodY-FP | TTCATGGACGCGGCTTTA | EMSA control |

| EMSA-PcodY-RP | /5′-Bio/ATGGATGTAATACGTCGCGTT | EMSA control |

| EMSA-PilvE-FP | GAACGGACTAGCAACGGTTCCT | EMSA control |

| EMSA-PilvE-RP | /5′-Bio/TTTAATACCTCTTTCCTCGT | EMSA control |

| pET30-CodY-NcoI-FP | TTTTTTCCATGGCTAATTTATTATCG | His-CodY |

| pET30-CodY-XhoI-RP | TTTTTTCTCGAGTTAACTATATCCTTTAA | His-CodY |

| 16S rRNA-S | CACACCGCCCGTCACACC | qRT-PCR (32) |

| 16S rRNA-AS | CAGCCGCACCTTCCGATACG | qRT-PCR (32) |

| RT-pta-FP | GGCAGTGCAAAGGCTTCTCAAGTT | qRT-PCR (32) |

| RT-pta-RP | ATTGGCTTGTCCTGCTACGTCACT | qRT-PCR (32) |

| RT-ackA-FP | TGATATGCGTGAAATTGAGGCGGC | qRT-PCR |

| RT-ackA-RP | TCACCAATACCCGCCGTAAAGACA | qRT-PCR |

/5′-Bio/, biotin-labeled primer at the 5′ end; /5′-6FAM/, 6-FAM-labeled primer at the 5′ end.

Mutagenesis.

Deletions of cre sites 5′ to the ackA and pta structural genes were generated using the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England BioLabs), according to the supplier's protocol. Briefly, DNA fragments containing the promoter regions of ackA or pta were amplified using specific primers, purified, and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Deletions were engineered with primers (Table 2) using the above plasmids as DNA templates. The resulting products were ligated and transformed into competent E. coli. Confirmation that the desired mutations were introduced was obtained using PCR and DNA sequencing.

CAT assay.

Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity was quantified as previously described (44). Strains carrying PackA-cat or Ppta-cat (32) promoter fusions in wild-type or mutant (ΔccpA or ΔcodY) genetic backgrounds were grown in BHI broth to mid-exponential phase at 37°C in a 5% CO2, aerobic atmosphere. For oxidative stress or low-pH conditions, the growth medium was supplemented with 0.003% H2O2 or titrated with HCl to lower the pH to 5.5, respectively. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 750 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.8. Proteins were extracted by mechanical disruption in a Bead Beater-16 cell disrupter (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK) with glass beads (0.1 mm) at 4°C for 30 s, twice, with a 2-min interval on ice after the first 30 s. Following centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatants were used to measure CAT activity. For measurement of CAT activity, 50 μl of the clarified whole-cell lysate was mixed with 950 μl of 0.1 mM acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and 0.4 mg/ml 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB). Each CAT reaction was initiated by addition of chloramphenicol to a final concentration of 0.1 mM, and the change in optical density at 412 nm was monitored for 3 min. The protein concentration of samples was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific). One unit of CAT activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to acetylate 1 nmol of chloramphenicol min−1 mg protein−1.

EMSAs.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as detailed elsewhere (45). Briefly, DNA fragments containing the promoter regions of ackA or pta were amplified by primers labeled on their 5′ end with biotinylated nucleotides (Table 2). Approximately 10 fmol of biotin-labeled probe was used in combination with different concentrations (0, 50, 100, or 200 pmol) of purified, recombinant His6-tagged CcpA (14) or with 50 pmol His6-tagged CodY in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 μg poly(dI-dC), 1 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 10% glycerol. GTP or branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) were included in the binding reaction mixtures at a final concentration of 5 mM or 10 mM, respectively, when desired. The binding reaction was allowed to occur at 37°C for 60 min, and then the DNA-protein samples were resolved in a 4.5% nondenaturing, low-ionic-strength polyacrylamide gel. The separated samples were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Perkin Elmer), and the membranes were air dried and then exposed to UV light to cross-link biological materials to the membranes. DNA was detected using the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module kit (Thermo Scientific) using the supplier's protocol.

DNase I footprinting assay.

DNase I footprinting experiments were performed using a nonradiochemical capillary electrophoresis method (46), with the following modifications. To map CcpA or CodY binding sites in the ackA or pta upstream regions, a 510-bp or 476-bp 5′ 6-FAM fluorescence-labeled/3′-biotinylated DNA fragment of the ackA or pta upstream region, respectively, was prepared by PCR using gene-specific primer pairs (Table 2) and gel purified. The amplified labeled DNA fragments were incubated individually with 0, 10, or 20 μg of His-tagged CcpA, and the 510-bp ackA upstream region was incubated with 0, 10, or 20 μg of His-tagged CodY protein at 37°C for 60 min in a 50-μl reaction mixture identical to that used for EMSAs. DNase I (0.1 unit) digestion was then performed at 37°C for 4 min, and the enzyme was inactivated by adding EDTA to a final concentration of 60 mM and heating the samples at 80°C for 10 min. The reaction mixtures were purified using a Centri-Sep column (Applied Biosystems, USA), vacuum desiccated, and resuspended in 10 μl Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems, USA). The samples were subjected to capillary electrophoresis by loading into a 3730xl DNA Analyzer with the GeneScan 600 LIZ dye size standard (Applied Biosystems, USA). Electropherograms were analyzed using the GelQuest program (http://www.sequentix.de/gelquest/).

Measurement of ATP.

The ATP content of cells was determined as described elsewhere (47). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in 5 ml of FMC containing 25 mM glucose, and cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.4. Following centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min, the cells were resuspended in fresh FMC that had been adjusted to pH 5.5 with HCl and incubated for an additional hour. Then, the samples were washed twice with 250 μl of cold buffer A (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA). Cells were resuspended in 250 μl of fresh cold buffer A and mechanically disrupted in a Bead Beater-16 cell disrupter (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK) with glass beads (0.1 mm) at 4°C for 30 s, twice. Triplicate 50-μl samples of the cell lysate were each mixed with 50 μl of CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) in a Costar Cell Culture 96-well, flat-bottom plate (Corning, Inc.). The mixtures were incubated at room temperature (RT) for 10 min, and luminescence was measured using a Synergy 2 multimode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA). All measurements were normalized to the amount of total protein in the extracts. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific).

qRT-PCR.

Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.4) in BHI or FMC at 37°C in a 5% CO2 aerobic atmosphere. The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of bacterial RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, resuspended in 10 mM TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), and then subjected to mechanical disruption in a Bead Beater-16 (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK). Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen). The concentration of RNA in the samples was determined using a spectrophotometer. The iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and random oligonucleotide primers were used to produce cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA. qRT-PCR was conducted using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a CF96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad) as follows: one cycle of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Target-specific primers used for PCRs were designed with PrimerQuest software (Integrated DNA Technologies). All expression data were normalized to the copy number of 16S rRNA in each sample.

Statistical analysis.

All graphical data display the means and standard deviations for a minimum of three biological replicates (n = 3) assayed in triplicate or greater. All data were analyzed using the Student t test with P values provided in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01 DE13239 (to R.A.B.) and a Pusan National University research grant (2016; to J.N.K.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03274-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornejo OE, Lefebure T, Bitar PD, Lang P, Richards VP, Eilertson K, Do T, Beighton D, Zeng L, Ahn SJ, Burne RA, Siepel A, Bustamante CD, Stanhope MJ. 2013. Evolutionary and population genomics of the cavity causing bacteria Streptococcus mutans. Mol Biol Evol 30:881–893. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon M, Montiel R, Smerling A, Solorzano E, Diaz N, Alvarez-Sandoval BA, Jimenez-Marin AR, Malgosa A. 2014. Molecular analysis of ancient caries. Proc Biol Sci 281:20140586. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler CJ, Dobney K, Weyrich LS, Kaidonis J, Walker AW, Haak W, Bradshaw CJ, Townsend G, Soltysiak A, Alt KW, Parkhill J, Cooper A. 2013. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions. Nat Genet 45:450–455. doi: 10.1038/ng.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warinner C, Hendy J, Speller C, Cappellini E, Fischer R, Trachsel C, Arneborg J, Lynnerup N, Craig OE, Swallow DM, Fotakis A, Christensen RJ, Olsen JV, Liebert A, Montalva N, Fiddyment S, Charlton S, Mackie M, Canci A, Bouwman A, Ruhli F, Gilbert MT, Collins MJ. 2014. Direct evidence of milk consumption from ancient human dental calculus. Sci Rep 4:7104. doi: 10.1038/srep07104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braidwood RJ, Howe B, Reed CA. 1961. The Iranian Prehistoric Project: new problems arise as more is learned of the first attempts at food production and settled village life. Science 133:2008–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.133.3469.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oelze VM, Siebert A, Nicklisch N, Meller H, Dresely V, Alt KW. 2011. Early Neolithic diet and animal husbandry: stable isotope evidence from three Linearbandkeramik (LBK) sites in Central Germany. J Archaeol Sci 38:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajdic D, McShan WM, McLaughlin RE, Savic G, Chang J, Carson MB, Primeaux C, Tian R, Kenton S, Jia H, Lin S, Qian Y, Li S, Zhu H, Najar F, Lai H, White J, Roe BA, Ferretti JJ. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:14434–14439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172501299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorke B, Stulke J. 2008. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutscher J. 2008. The mechanisms of carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deutscher J, Kuster E, Bergstedt U, Charrier V, Hillen W. 1995. Protein kinase-dependent HPr/CcpA interaction links glycolytic activity to carbon catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol 15:1049–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saier MH., Jr 1996. Cyclic AMP-independent catabolite repression in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 138:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weickert MJ, Chambliss GH. 1990. Site-directed mutagenesis of a catabolite repression operator sequence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:6238–6242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willenborg J, de Greeff A, Jarek M, Valentin-Weigand P, Goethe R. 2014. The CcpA regulon of Streptococcus suis reveals novel insights into the regulation of the streptococcal central carbon metabolism by binding of CcpA to two distinct binding motifs. Mol Microbiol 92:61–83. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abranches J, Nascimento MM, Zeng L, Browngardt CM, Wen ZT, Rivera MF, Burne RA. 2008. CcpA regulates central metabolism and virulence gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 190:2340–2349. doi: 10.1128/JB.01237-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng L, Choi SC, Danko CG, Siepel A, Stanhope MJ, Burne RA. 2013. Gene regulation by CcpA and catabolite repression explored by RNA-Seq in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One 8:e60465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burne RA, Wen ZT, Chen YY, Penders JE. 1999. Regulation of expression of the fructan hydrolase gene of Streptococcus mutans GS-5 by induction and carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol 181:2863–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moye ZD, Zeng L, Burne RA. 2014. Fueling the caries process: carbohydrate metabolism and gene regulation by Streptococcus mutans. J Oral Microbiol 6:24878–24892. doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.24878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santiago B, Marek M, Faustoferri RC, Quivey RG Jr. 2013. The Streptococcus mutans aminotransferase encoded by ilvE is regulated by CodY and CcpA. J Bacteriol 195:3552–3562. doi: 10.1128/JB.00394-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shivers RP, Dineen SS, Sonenshein AL. 2006. Positive regulation of Bacillus subtilis ackA by CodY and CcpA: establishing a potential hierarchy in carbon flow. Mol Microbiol 62:811–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Freedman JC, McClane BA. 2015. NanI sialidase, CcpA, and CodY work together to regulate epsilon toxin production by Clostridium perfringens type D strain CN3718. J Bacteriol 197:3339–3353. doi: 10.1128/JB.00349-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam M, Serror P, Wong KW, Sonenshein AL. 2001. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early-stationary-phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev 15:1093–1103. doi: 10.1101/gad.874201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonenshein AL. 2005. CodY, a global regulator of stationary phase and virulence in Gram-positive bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guedon E, Sperandio B, Pons N, Ehrlich SD, Renault P. 2005. Overall control of nitrogen metabolism in Lactococcus lactis by CodY, and possible models for CodY regulation in Firmicutes. Microbiology 151:3895–3909. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.den Hengst CD, Curley P, Larsen R, Buist G, Nauta A, van Sinderen D, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2005. Probing direct interactions between CodY and the oppD promoter of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 187:512–521. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.2.512-521.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemos JA, Nascimento MM, Lin VK, Abranches J, Burne RA. 2008. Global regulation by (p) ppGpp and CodY in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 190:5291–5299. doi: 10.1128/JB.00288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belitsky BR. 2011. Indirect repression by Bacillus subtilis CodY via displacement of the activator of the proline utilization operon. J Mol Biol 413:321–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendriksen WT, Bootsma HJ, Estevao S, Hoogenboezem T, de Jong A, de Groot R, Kuipers OP, Hermans PW. 2008. CodY of Streptococcus pneumoniae: link between nutritional gene regulation and colonization. J Bacteriol 190:590–601. doi: 10.1128/JB.00917-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petranovic D, Guedon E, Sperandio B, Delorme C, Ehrlich D, Renault P. 2004. Intracellular effectors regulating the activity of the Lactococcus lactis CodY pleiotropic transcription regulator. Mol Microbiol 53:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santiago B, MacGilvray M, Faustoferri RC, Quivey RG Jr. 2012. The branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase encoded by ilvE is involved in acid tolerance in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 194:2010–2019. doi: 10.1128/JB.06737-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JN, Ahn SJ, Burne RA. 2015. Genetics and physiology of acetate metabolism by the Pta-Ack pathway of Streptococcus mutans. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5015–5025. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01160-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlsson J. 1983. Regulation of sugar metabolism in relation to feast-and-famine existence of plaque, p 205–211. In Guggenheim B. (ed), Cariology today. Karger, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JN, Ahn SJ, Seaton K, Garrett S, Burne RA. 2012. Transcriptional organization and physiological contributions of the relQ operon of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 194:1968–1978. doi: 10.1128/JB.00037-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng L, Wen ZT, Burne RA. 2006. A novel signal transduction system and feedback loop regulate fructan hydrolase gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. Mol Microbiol 62:187–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banas JA. 2004. Virulence properties of Streptococcus mutans. Front Biosci 9:1267–1277. doi: 10.2741/1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemos JA, Burne RA. 2008. A model of efficiency: stress tolerance by Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 154:3247–3255. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/023770-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang DE, Shin S, Rhee JS, Pan JG. 1999. Acetate metabolism in a pta mutant of Escherichia coli W3110: importance of maintaining acetyl coenzyme A flux for growth and survival. J Bacteriol 181:6656–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown TD, Jones-Mortimer MC, Kornberg HL. 1977. The enzymic interconversion of acetate and acetyl-coenzyme A in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol 102:327–336. doi: 10.1099/00221287-102-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nascimento MM, Lemos JA, Abranches J, Goncalves RB, Burne RA. 2004. Adaptive acid tolerance response of Streptococcus sobrinus. J Bacteriol 186:6383–6390. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6383-6390.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Y, Tian XL, Sutherland T, Sisson G, Mai J, Ling J, Li YH. 2009. Global transcriptional analysis of acid-inducible genes in Streptococcus mutans: multiple two-component systems involved in acid adaptation. Microbiology 155:3322–3332. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahn SJ, Wen ZT, Burne RA. 2007. Effects of oxygen on virulence traits of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 189:8519–8527. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moye ZD, Zeng L, Burne RA. 2014. Modification of gene expression and virulence traits in Streptococcus mutans in response to carbohydrate availability. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:972–985. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03579-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sturr MG, Marquis RE. 1992. Comparative acid tolerances and inhibitor sensitivities of isolated F-ATPases of oral lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:2287–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terleckyj B, Willett NP, Shockman GD. 1975. Growth of several cariogenic strains of oral streptococci in a chemically defined medium. Infect Immun 11:649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen ZT, Burne RA. 2004. LuxS-mediated signaling in Streptococcus mutans is involved in regulation of acid and oxidative stress tolerance and biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 186:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2682-2691.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng L, Dong Y, Burne RA. 2006. Characterization of cis-acting sites controlling arginine deiminase gene expression in Streptococcus gordonii. J Bacteriol 188:941–949. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.941-949.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yindeeyoungyeon W, Schell MA. 2000. Footprinting with an automated capillary DNA sequencer. Biotechniques 29:1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramos-Montanez S, Kazmierczak KM, Hentchel KL, Winkler ME. 2010. Instability of ackA (acetate kinase) mutations and their effects on acetyl phosphate and ATP amounts in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. J Bacteriol 192:6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/JB.00995-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen ZT, Burne RA. 2002. Analysis of cis- and trans-acting factors involved in regulation of the Streptococcus mutans fructanase gene (fruA). J Bacteriol 184:126–133. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.1.126-133.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.