ABSTRACT

Acetate, propionate, and butyrate (volatile fatty acids [VFA]) occur in oil field waters and are frequently used for microbial growth of oil field consortia. We determined the kinetics of use of these VFA components (3 mM each) by an anaerobic oil field consortium in microcosms containing 2 mM sulfate and 0, 4, 6, 8, or 13 mM nitrate. Nitrate was reduced first, with a preference for acetate and propionate. Sulfate reduction then proceeded with propionate (but not butyrate) as the electron donor, whereas the fermentation of butyrate (but not propionate) was associated with methanogenesis. Microbial community analyses indicated that Paracoccus and Thauera (Paracoccus-Thauera), Desulfobulbus, and Syntrophomonas-Methanobacterium were the dominant taxa whose members catalyzed these three processes. Most-probable-number assays showed the presence of up to 107/ml of propionate-oxidizing sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in waters from the Medicine Hat Glauconitic C field. Bioreactors with the same concentrations of sulfate and VFA responded similarly to increasing concentrations of injected nitrate as observed in the microcosms: sulfide formation was prevented by adding approximately 80% of the nitrate dose needed to completely oxidize VFA to CO2 in both. Thus, this work has demonstrated that simple time-dependent observations of the use of acetate, propionate, and butyrate for nitrate reduction, sulfate reduction, and methanogenesis in microcosms are a good proxy for these processes in bioreactors, monitoring of which is more complex.

IMPORTANCE Oil field volatile fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate were specifically used for nitrate reduction, sulfate reduction, and methanogenic fermentation. Time-dependent analyses of microcosms served as a good proxy for these processes in a bioreactor, mimicking a sulfide-producing (souring) oil reservoir: 80% of the nitrate dose required to oxidize volatile fatty acids to CO2 was needed to prevent souring in both. Our data also suggest that propionate is a good substrate to enumerate oil field SRB.

KEYWORDS: butyrate oxidation, methanogenesis, nitrate dose, nitrate injection, propionate oxidation, souring control, syntrophic degradation

INTRODUCTION

The injection of water into oil fields to maintain reservoir pressure often leads to increased concentrations of sulfide (souring) through the activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), which derive energy for growth from the oxidation of oil organics to reduce sulfate to sulfide (1, 2). The sulfide formed represents a health hazard, decreases the value of produced oil, and/or accelerates corrosion of facilities and infrastructure.

Nitrate injection is a well-known strategy for control of souring (3, 4). The mechanism of inhibition of sulfate reduction by nitrate injection includes biocompetitive exclusion of SRB by heterotrophic nitrate-reducing bacteria (hNRB), which assumes that these use the same electron donors for reduction of nitrate as are used by SRB for reduction of sulfate (5–9).

Volatile fatty acids (VFA), which include acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are considered to be major electron donors shared by hNRB and SRB. A survey of 21 formation waters from wells accessing oil reservoirs on the Norwegian continental shelf (10) gave average concentrations of 4.7 mM acetate (range, 0.32 to 16.9 mM), 0.48 mM propionate (range, 0.05 to 1.53 mM), and 0.14 mM butyrate (range, 0 to 0.82 mM). Produced waters from fields in the Danish sector of the North Sea and from the Kuparuk oil field in Alaska had concentrations in the same range (11, 12). All of these oil fields had a high downhole temperature of 60 to 90°C. Produced waters from a mesothermic Alaskan oil field contained on average 3.5 mM acetate, 0.65 mM propionate, and 0.12 mM butyrate, with some samples having zero VFA (13). Produced waters from the Medicine Hat Glauconitic C (MHGC) field with a downhole temperature of 30°C (3) had lower VFA concentrations, with 0.12 mM acetate detected. In view of these results, microbial tests have been done with acetate and propionate (14) or with acetate, propionate, and butyrate (15).

VFA are formed by anaerobic metabolism of oil hydrocarbons. Their concentrations thus result from rates of formation and of use. Transient formation of acetate was demonstrated in a bioreactor (containing heavy MHGC oil) whenever injection of nitrate was terminated and reduction of sulfate restarted (16). VFA may be formed by beta-oxidation of alkanes, with even-chain-length alkanes forming acetate (equation 1) and uneven-chain-length alkanes forming acetate and propionate (equation 2). Butyrate may be formed if the final beta-oxidation step in the degradation of even-chain-length alkanes (equation 3) remains incomplete. These reactions are catalyzed by syntrophic Firmicutes or Deltaproteobacteria (17–19) and are driven forward by removal of the H2 formed by hydrogenotrophic methanogens (equation 4) or SRB (equation 5) (17, 19–21). High VFA concentrations result if the rates of these hydrogenotrophic reactions exceed those for acetotrophic methanogenesis or syntrophic acetate oxidation or the use of VFA for sulfate reduction.

VFA are also used by hNRB in biological nitrogen removal in wastewater treatment. In this process, acetate is used first, followed by propionate and butyrate and finally valerate (22). In addition, VFA are important electron donors in enhanced biological phosphorus removal and are precursors for biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates (23). They also function as electron donors in microbial fuel cells for electricity generation or hydrogen production (24, 25).

Previous work on the use of VFA as electron donors in microcosms has shown that use of propionate and butyrate by SRB to reduce sulfate to sulfide is accompanied by acetate production (26). Nitrate reduction by hNRB occurred with all three VFA components (26). Once nitrate was depleted, methanogenesis was also observed (4, 26–28). In this study, the effects of nitrate addition on sulfate reduction and methanogenesis by an anaerobic oil field consortium in microcosms were compared with those in an up-flow bioreactor operated under similar conditions. Bioreactors mimic souring in reservoir environments subjected to nitrate injection more accurately but are more laborious to run. We conclude that, despite differences in kinetics, the two approaches give similar results with respect to the nitrate dose needed to control souring.

RESULTS

Kinetics of use of VFA by oil-field microcosms.

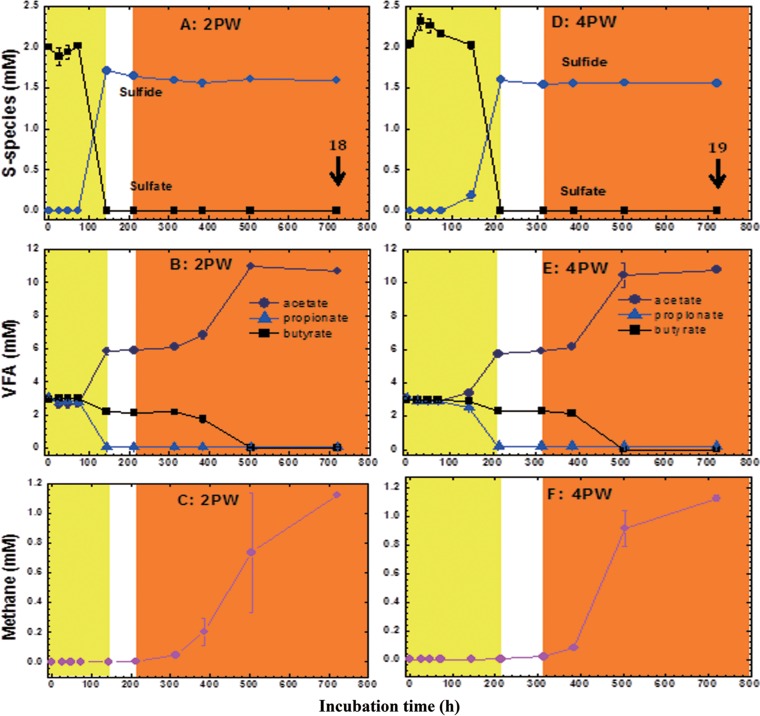

MHGC-produced waters contained on average 0.117 mM acetate (n = 29; range, 0.056 to 0.315 mM). Propionate and butyrate were not detected. When 10% (vol/vol) of duplicate samples of waters produced from producing wells (PW) 2PW, 4PW, 7PW, and 13PW was inoculated into CSBA-S medium (7 g NaCl per liter, 0.2 g KH2PO4 per liter, 0.4 g MgCl2 · 6H2O per liter, 0.5 g KCl per liter, 0.15 g CaCl2 · 2H2O per liter, 0.25 g NH4Cl per liter [29] containing 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM VFA), all of the samples showed similar uses of VFA components except for one of the replicates of 7PW (7PWb). SRB first reduced sulfate to sulfide (1.7 mM) with a preference for propionate as the electron donor, which was converted to acetate (equation 6). Subsequent methanogenesis was coupled to the conversion of butyrate to two acetates (equation 7). These two processes increased the acetate concentration from 3 to 11 mM (Fig. 1B and E; see also Fig. S1B and F in the supplemental material). Sulfate, propionate, and butyrate were completely consumed at the end of the incubations. Methane was detected at concentrations of up to 1.1 mM in the headspace of the bottles. Correcting for the difference in the volumes of the headspace (67 ml) and aqueous phase (55 ml) indicates formation of 1.3 mM methane, which is close to the theoretical maximum of 1.5 mM methane formed from 3 mM butyrate according to equation 8.

FIG 1.

Sulfate reduction (yellow) and methanogenesis (orange) in CSBA-S medium with 3 mM VFA inoculated with water produced from 2PW (A to C; microcosm 2PW_S2V3_18) or 4PW (D to F; microcosm 4PW_S2V3_19). The concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, and VFA in the aqueous phase and of methane in the headspace are shown as a function of time. The data represent averages of results from duplicate incubations, with standard deviations shown when these exceed the size of the symbols. The numbered arrows indicate sampling for DNA isolation.

However, butyrate was used preferentially in microcosm 7PWb as the electron donor for sulfate reduction. Only 1 mM propionate was oxidized, with 2 mM propionate remaining (Fig. S1C). The decreased availability of butyrate allowed production of only 0.5 mM methane (corrected for volume) in microcosm 7PWb (Fig. S1D). This was much lower than that in microcosm 7PWa, in which propionate was used for sulfate reduction (as in all other microcosms) and butyrate for methanogenesis with production of 1.5 mM methane (corrected for volume; Fig. S1D). Since the VFA components were used with similar kinetics in all other microcosms, the microcosm inoculated with 2PW was assumed to be representative of all microcosms and was used throughout in further experiments (see Table 2 [E2PW]).

TABLE 2.

Sequence accession numbers, numbers of quality controlled reads, and derived numbers of operational taxonomic units and taxa for 22 amplicon librariesa

| Library_name_no.b | Day or inoculumc | SA no. | No. of QC reads | No. of OTUs | No. of taxa | Shannon index | Archaea (%) | Bacteria (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE_S2N13V3_1 | 45 | SRR1555313 | 8,338 | 31 | 52 | 1.19 | 0.6 | 99.4 |

| BE_S2V3_2 | 60 | SRR1555314 | 3,743 | 65 | 65 | 2.17 | 8.6 | 91.3 |

| BE_S2N4A3P3_3 | 83 | SRR1555315 | 7,876 | 28 | 55 | 1.25 | 1.3 | 98.7 |

| BE_S2N8A3P3_4 | 95 | SRR1555331 | 5,371 | 29 | 43 | 1.03 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| BE_S2N13A3P3_5 | 111 | SRR1555323 | 6,551 | 75 | 86 | 2.39 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| BE_S2N4P3_6 | 145 | SRR1555332 | 7,832 | 27 | 49 | 0.57 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| BE_S2N6P3_7 | 161 | SRR1555334 | 6,467 | 41 | 53 | 1.43 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| E_S2V3_8 | E2PW | SRR1555316 | 7,283 | 18 | 25 | 0.75 | 77.4 | 22.6 |

| E_S2N4V3_9 | E2PW | SRR1555320 | 5,041 | 27 | 35 | 1.07 | 2.0 | 98.0 |

| E_S2N8V3_10 | E2PW | SRR1555321 | 12,006 | 19 | 38 | 0.90 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| E_S2N13V3_11 | E2PW | SRR1555322 | 9,291 | 22 | 36 | 1.19 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| E_S2N4V3_12 | E2PW | SRR1555317 | 8,717 | 33 | 47 | 1.10 | 10.6 | 89.4 |

| E_S2N8V3_13 | E2PW | SRR1555318 | 10,728 | 26 | 32 | 0.82 | 0.3 | 99.7 |

| E_S2N13V3_14 | E2PW | SRR1555319 | 1,831 | 32 | 28 | 1.02 | 1.3 | 98.7 |

| E_S2P3_15 | E2PW | SRR1555328 | 7,603 | 31 | 49 | 1.12 | 5.4 | 94.6 |

| E_S2B3_16 | E2PW | SRR1555329 | 7,190 | 31 | 30 | 1.32 | 30.3 | 69.7 |

| E_V3_17 | E2PW | SRR1555330 | 7,129 | 21 | 25 | 1.15 | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| 2PW_S2V3_18 | 2PW | SRR1555324 | 7,773 | 55 | 56 | 1.62 | 88.0 | 12.0 |

| 4PW_S2V3_19 | 4PW | SRR1555325 | 6,860 | 67 | 67 | 2.33 | 62.6 | 37.5 |

| 7PWa_S2V3_20 | 7PW | SRR1555326 | 9,040 | 70 | 64 | 2.08 | 81.6 | 18.4 |

| 7PWb_S2V3_21 | 7PW | SRR1555333 | 12,261 | 41 | 58 | 1.75 | 64.5 | 35.5 |

| 13PW_S2V3_22 | 13PW | SRR1555327 | 6,208 | 55 | 49 | 1.77 | 62.0 | 38.0 |

Shannon index values and fractions (percent) of bacterial and archaeal reads are also indicated.

Samples were from bioreactor effluent (BE) or from microcosms. Inputs were as follows: S, sulfate; N, nitrate; V, VFA; A, acetate, P, propionate, B, butyrate. The numbers are the concentrations in millimoles. All had 2 mM sulfate (S2), except sample 17 (E_V3_17), which had only 3 mM VFA. SA, sequence accession; QC, quality controlled; OTUs, operational taxonomic units.

Data represent the day on which the BE sample was taken or the inoculum that was used to start the microcosm (produced water from 2PW, 4PW, 7PW or 13PW, or 2PW enrichment [E2PW]).

In microcosms with 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM propionate, sulfate reduction started immediately: 1.2 mM sulfide was produced, and all propionate was oxidized with the production of 3 mM acetate, per equation 6. No methane production was observed (Fig. 2A, B, and C). In microcosms with 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM butyrate sulfate, reduction started after a lag phase of 150 h (Fig. 2D). No methane formation was observed during this period. Subsequent oxidation of 3 mM butyrate to 6 mM acetate was coupled to the reduction of 1.2 mM sulfate to sulfide and the formation of 0.3 mM methane (corrected for volume; Fig. 2D, E, and F), per equation 9. Incubations with 3 mM VFA in the absence of sulfate showed that only butyrate was used for methanogenesis. Metabolism of 3 mM butyrate caused the acetate concentration to increase to 9 mM and the corrected methane concentration to increase to 1.3 mM (Fig. 3), which were somewhat less than the theoretically expected 1.5 mM concentration of methane (equation 7). Propionate was not used under these conditions.

FIG 2.

Sulfate reduction (yellow) and methanogenesis (orange) in CSBA-S medium with 3 mM propionate (A, B, and C; microcosm E_S2P3_15) or butyrate (D, E, and F; microcosm E_S2B3_16) and inoculated with 2PW enrichment. (D, E, and F) Color overlap indicates that the two processes occurred simultaneously. The concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, propionate, butyrate, and acetate in the aqueous phase and of methane in the headspace are shown as a function of time. The data represent averages of results from duplicate incubations, with standard deviations shown when these exceed the size of the symbols. The numbered arrows indicate sampling for DNA isolation.

FIG 3.

Syntrophic butyrate degradation and coupled methanogenesis (orange) in CSBA medium with 3 mM VFA in microcosm E_V3_17. The concentrations of aqueous acetate, propionate, and butyrate (A) and of headspace methane (B) are shown as a function of time. The data represent averages of results from duplicate incubations; standard deviations did not exceed the size of the symbols.

Use of VFA in the presence of nitrate.

When 4 mM nitrate was added to CSBA-S medium containing 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM VFA, the nitrate was completely reduced within 25 h. No nitrite intermediate was detected. A small decrease in the ammonium concentration in the medium was noted (Fig. S2A). The ammonium was probably used as the nitrogen source in biomass synthesis. These results indicate that nitrate was mostly reduced to N2 and not to ammonium, as shown elsewhere (30). Nitrate reduction was coupled to preferential oxidation of acetate and propionate (Fig. S2C). Reduction of 2 mM sulfate (Fig. S2B) then proceeded with use of the remaining propionate and butyrate as the electron donor, forming 5 mM acetate (Fig. S2C). A little methane (0.1 mM) was formed in the headspace (Fig. S2D).

When added at 8 mM, nitrate was first reduced to N2 with removal of 3 mM acetate, 3 mM propionate, and 1 mM butyrate (Fig. S3A). This stoichiometry shows that not all VFA were oxidized to CO2 per equations 10 to 12, which would yield 2-fold more electrons (86 mM) than are required to reduce 8 mM nitrate to N2 (40 mM, per equation 13). Hence, some VFA were used as the carbon source for the formation of biomass and associated storage polymers. Sulfate (1.4 mM) was then reduced to sulfide (Fig. S3B) with the oxidation of the residual 2 mM butyrate and of biomass to form 5 mM acetate (Fig. S3C). The kinetics of acetate formation was considerably slower than that of butyrate use (Fig. S3C), suggesting acetate formation via a more complex route than mere oxidation of butyrate. No methane was formed. Upon addition of 13 mM nitrate, nitrate reduction proceeded with the complete removal of all VFA within 25 h (Fig. S4A). This stoichiometry indicates partial oxidation of VFA to CO2 and use of VFA for formation of biomass and storage polymers. The latter participated in reduction of 0.7 mM sulfate to sulfide from 100 h onward (Fig. S4B) and in formation of 2 mM acetate at 300 h (Fig. S4C). No methanogenesis was observed. Thus, addition of 0, 4, 8, and 13 mM nitrate resulted in remaining sulfate concentrations of 0, 0, 0.7, and 1.3 mM and production of 2, 2, 1.3, and 0.7 mM sulfide, indicating increased but not complete souring control. The theoretical nitrate dose at which all of the 3 mM VFA are oxidized to CO2 is 25.2 mM (equation 14).

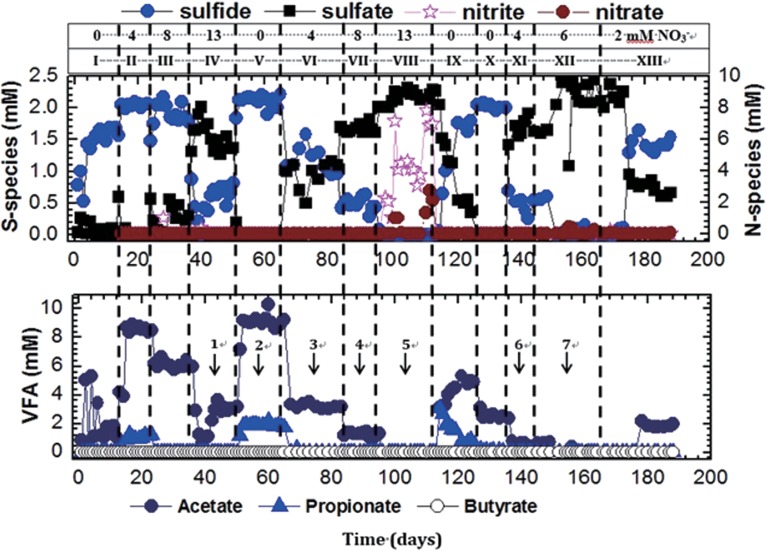

Effect of nitrate on souring in bioreactors.

To establish microbial activity, the bioreactor was inoculated with 0.5× the pore volume (PV) (14 ml) of the SRB enrichment E2PW. The bioreactor was then incubated for 1 week without flow, after which CSBA medium containing 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM VFA was pumped in at a flow rate of 42 ml/day. The concentration of injected sulfate (2 mM) and flow rate were constant throughout. The nitrate concentration and the kinds of VFA injected (at 3 mM each) are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of the indicated analytes in the bioreactor effluent during stages I to XIIIa

| Stage (days) | Input(s)b | Concn of analyte in effluent (mM) |

DNA dayc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfate | Sulfide | Nitrate | Nitrite | Acetate | Propionate | |||

| I (1–13) | 3 VFA | 0.03 ± 0.08 | 1.63 ± 0.08 | 4.04 ± 0.2 | 0 | |||

| II (14–22) | 3 VFA, 4 NO3− | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 8.57 ± 0.11 | 1.06 ± 0.1 | |

| III (23–35) | 3 VFA, 8 NO3− | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 1.87 ± 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 6.09 ± 0.13 | 0 | |

| IV (36–49) | 3 VFA, 13 NO3− | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 0.67 ± 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 3.01 ± 0.09 | 0 | 45 |

| V (50–64) | 3 VFA | 0 | 2.08 ± 0.09 | 9.17 ± 0.42 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 60 | ||

| VI (65–83) | 3 ace, 3 prop, 4 NO3− | 1.05 ± 0.08 | 1.11 ± 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 3.10 ± 0.06 | 0 | 83 |

| VII (84–95) | 3 ace, 3 prop, 8 NO3− | 1.67 ± 0.07 | 0.47 ± 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 1.19 ± 0.17 | 0 | 95 |

| VIII (96–112) | 3 ace, 3 prop, 13 NO3− | 2.2 ± 0.05 | 0 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 111 |

| IX (113–125) | 3 ace, 3 prop | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 1.72 ± 0.05 | 5.01 ± 0.17 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | |||

| X (127–134) | 3 prop | 0 | 2.01 ± 0.03 | 2.48 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | |||

| XI (136–147) | 3 prop, 4 NO3− | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 145 | |

| XII (149–163) | 3 prop, 6 NO3− | 2.21 ± 0.14 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 161 |

| XIII (164–187) | 3 prop, 2 NO3− | 0.7 ± 0.07 | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 1.82 ± 0.05 | 0 | |

Data are shown in Fig. 4; the flow rate was 42 ml/day (1.5 PV/day); 2 mM sulfate was injected throughout; butyrate was not detected.

Numbers are concentrations in millimoles ± standard deviations. ace, acetate; prop, propionate.

Data represent the days on which effluent samples were collected for 454 sequencing.

When 3 mM VFA and 0 mM nitrate were injected, complete reduction of sulfate to 1.6 mM aqueous sulfide was obtained after day 10 (Fig. 4, stage I). No propionate or butyrate was detected in the effluent, which contained a low (1 to 4 mM) concentration of acetate compared to 11 to 12 mM in comparable microcosms (Fig. 1B and E). These lower acetate concentrations suggested increased formation of methane, which was not monitored in the bioreactors. Injection of 4 mM nitrate did not limit sulfate reduction because 2 mM sulfide was still detected in the effluent. However, the concentrations of acetate and propionate in the effluent increased to 8.6 and 1 mM, respectively (Fig. 4, stage II). This acetate concentration was similar to that observed in the comparable microcosm (Fig. S2C), indicating inhibition of methanogenesis by the nitrate injection. When 8 mM nitrate was injected, some sulfate remained, the average sulfide concentration in the effluent was 1.9 mM, and the average acetate concentration dropped to 6 mM (Fig. 4, stage III), which was similar to the 5 mM acetate concentration observed in the microcosm represented in Fig. S3C. No propionate was observed in the effluent. Souring was partially controlled by injecting 13 mM nitrate, which limited reduction of sulfate to 0.7 mM sulfide, while the acetate concentration decreased further to 3 mM (Fig. 4, stage IV). This can be compared to the microcosm represented in Fig. S4, in which 0.7 mM sulfide and 2 mM acetate were observed. No propionate, butyrate, nitrate, or nitrite was found in the effluent, similarly to the findings in the comparable microcosm (Fig. S4). When nitrate injection was stopped, the sulfide concentration rose immediately to 2 mM and the acetate and propionate concentrations increased to 9.2 mM and 2 mM, respectively (Fig. 4, stage V). This indicated that the sulfate reduction had been restored to the same level as during the startup (Fig. 4, stage I). However, increased concentrations of acetate and propionate in stage V, compared to stage I, suggest that nitrate injection provided long-term inhibition of methanogenic activity.

FIG 4.

Effect of nitrate (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 13 mM) on souring in an up-flow, packed-bed bioreactor injected with CSBA medium with 2 mM sulfate and electron donors as follows: stages I to V, 3 mM (each) acetate, propionate, and butyrate; stages VI to IX, 3 mM acetate and 3 mM propionate; stages X to XIII, 3 mM propionate. The concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, nitrate, nitrite, acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the effluent are shown as a function of time. The numbered arrows indicate sampling for DNA isolation. (Top) S-species. (Bottom) VFA.

When 3 mM acetate and 3 mM propionate were injected with 4, 8, or 13 mM nitrate, the sulfide concentration in the effluent decreased to 1, 0.5, or 0 mM, respectively (Fig. 4, stages VI, VII, and VIII). The concentrations of acetate in the effluent were 3, 1, and 0 mM, respectively. No propionate was observed. Injection of 13 mM nitrate led on average to a breakthrough of 1 mM nitrate and up to 4 mM nitrite in the bioreactor effluent (Fig. 4, stage VIII). As indicated in equation 15, 13.2 mM nitrate can completely oxidize 3 mM propionate and 3 mM acetate to CO2. The average eluted concentrations of 1 mM nitrate and 4 mM nitrite indicate that the nitrate was only about 80% reduced. Hence, 20% of the injected acetate and propionate most likely served as the carbon source for biomass formation. When nitrate injection was stopped, the concentrations of sulfide and acetate in the effluent increased within 10 days to 1.7 and 5.0 mM, respectively (Fig. 4, stage IX), whereas the concentration of propionate was 0.71 mM in the same period. This is consistent with propionate being incompletely oxidized to acetate and CO2 while serving as the electron donor for sulfate reduction.

The available electron donor concentrations were then further decreased from 3 mM acetate and 3 mM propionate to 3 mM propionate only. In the absence of nitrate, complete reduction of 2 mM sulfate to sulfide was observed with production of 2 to 3 mM acetate in the effluent (Fig. 4, stage X). Subsequent injection of 4 and 6 mM nitrate resulted in partial and complete control of souring (Fig. 4, stages XI and XII, respectively). No acetate was observed in the effluent when 6 mM nitrate was injected. Although 8.4 mM nitrate is needed to completely oxidize 3 mM propionate to CO2 (equation 16), the observation that 6 mM nitrate was sufficient to control souring indicates again that part of the propionate was used as the carbon source for biomass formation. When the injected nitrate concentration was decreased to 2 mM, the sulfide and acetate concentrations increased to 1.5 and 2 mM, respectively (Fig. 4, stage XIII).

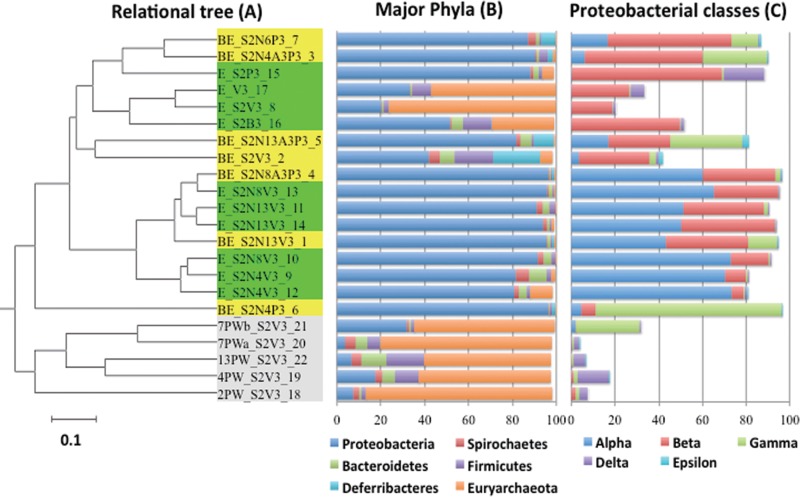

Microbial community analyses.

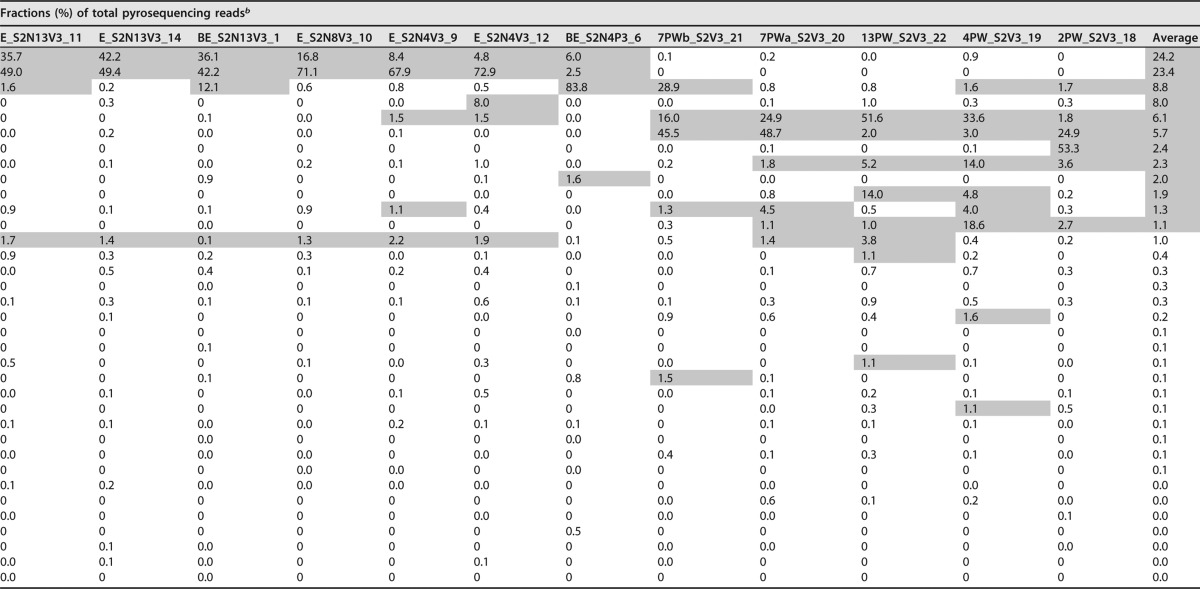

DNA was isolated and subjected to PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes and pyrosequencing, yielding 7 amplicon libraries for bioreactor effluents and 15 amplicon libraries for microcosms (Table 2).

Comparisons in a dendrogram (Fig. 5A) indicated clade I for libraries of bioreactor effluents and enrichments (inoculated with E2PW) and clade II for libraries of microcosms directly inoculated with field samples (2PW_S2V3, 4PW_S2V3, 7PWa_S2V3, 7PWb_S2V3, and 13PW_S2V3). Because the enrichments were harvested after prolonged incubation, where nitrate and sulfate had already been reduced (see arrows in Fig. 1 to 3 and S1 to S4), the physiological states of these enrichments corresponded to those of the bioreactor effluents, which were also mostly devoid of electron acceptors. Microbial community compositions are presented in Table 3. Microbial communities in clade II for microcosms inoculated with field samples had high fractions of hydrogenotrophic methanogens (31–33), including Methanocalculus (1.8 to 51.6%), Methanocorpusculum (0 to 53.3%), and Methanofollis (0.3 to 18.6%). Interestingly, a high proportion (2.0 to 48.7%) of the acetotrophic methanogen Methanosaeta was present (Table 3) even though methane production from the metabolism of acetate was not detected in these microcosms. Microbial communities in clade I are discussed below.

FIG 5.

Analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences (reads) in 22 amplicon libraries, identified by name and number as described for Table 2. (A) Relational tree; the bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position. Clades I and II are indicated, as explained in the text. (B and C) Fractions of phyla (percent total reads) (B) and fractions of classes (percent Proteobacteria reads) (C).

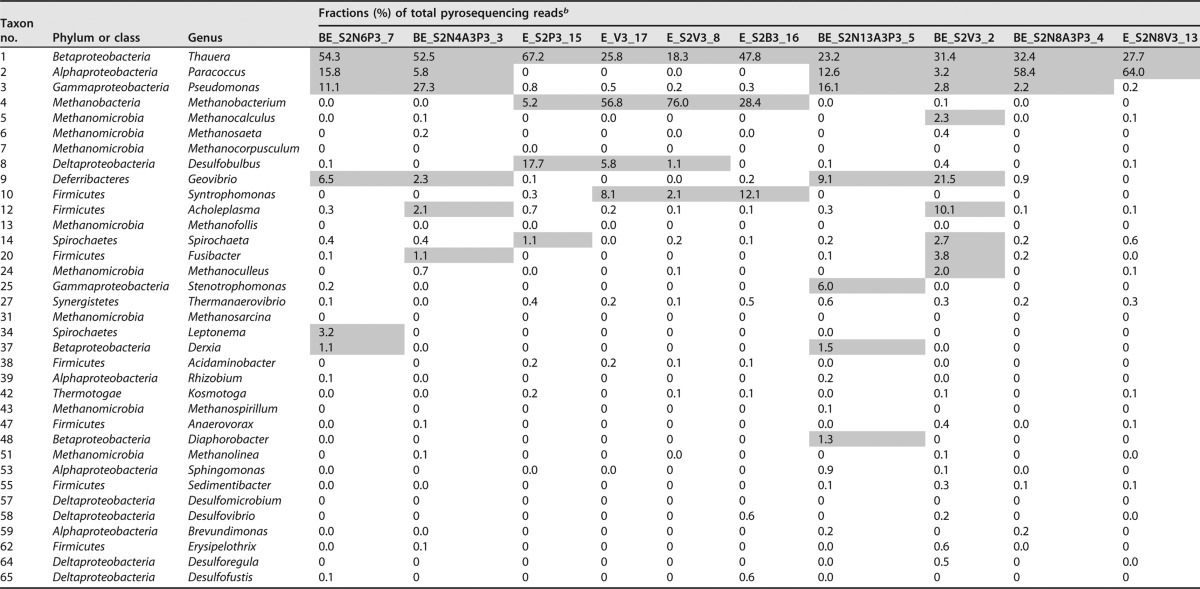

TABLE 3.

Taxa in 16S rRNA libraries from microcosms and bioreactor effluentsa

Taxa are presented in the same order as in the dendrogram in Fig. 5A. Library numbers (1 to 22) are as indicated in Fig. 1 to 4 and Fig. S1 to S4.

The numbers shown are fractions (percent) of total pyrosequencing reads. Fractions in excess of 1% are indicated with gray shading. The data in the table are ranked according to average fraction values. Missing entries (e.g., entries 15 to 19) could not be assigned at the genus level.

Use of propionate for measuring the MPN of SRB in oil field samples.

Our results have shown that VFA components served different functions, with propionate being used for sulfate reduction and butyrate being used for syntrophy and methanogenesis. The presence of SRB in oil field samples is often evaluated by most-probable-number (MPN) assays in which lactate is used as the electron donor for sulfate reduction (34). Because propionate is readily used by SRB in the MHGC field, we compared MPNs in lactate-containing media with those obtained in propionate-containing media. The data for 13 samples showed that log MPN obtained with propionate was linearly related to log MPN for lactate (Fig. S5; r2 = 0.86). Although lactate-utilizing SRB were more numerous than propionate-utilizing SRB, the difference was less than 10-fold at a high MPN (107/ml).

DISCUSSION

The effect of nitrate on sulfide-producing oil field consortia has been studied in microcosms (4, 7–9, 11, 26, 30, 35, 36), in bioreactors (14, 16, 29, 37), and in the field (3–5, 11, 15, 30). Despite this wealth of information, some misconceptions remain. One of these is that the inhibitory effect of nitrate is due to competitive exclusion (8) in which hNRB outcompete SRB for the same electron donors. This is typically demonstrated in bottle tests (microcosms) with a high concentration of nitrate relative to that of the available electron donor (e.g., VFA). Because nitrate is always reduced first, no sulfate reduction is observed under these conditions. However, in the presence of excess VFA, nitrate reduction is followed by sulfate reduction, giving only transient inhibition as observed here in microcosms and in bioreactors (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S2 to S4 in the supplemental material) and as shown elsewhere (26, 29, 37). Excess amounts of electron donors are expected in oil fields, and transient inhibition was indeed demonstrated in the MHGC field, when injection water with 1 mM sulfate was continuously amended with 2 mM nitrate (3, 4). Interestingly, competitive exclusion applies in the presence of excess electron donors at high (>50°C) temperatures, because nitrate reduction stops at nitrite under these conditions (35). Nitrite is a very strong and specific SRB inhibitor (38) which targets sulfide-producing dissimilatory sulfite reductase (Dsr).

A second misconception, related to the first, is that when VFA serve as the electron donors for the reduction of nitrate and sulfate in oil fields, the nitrate dose required to prevent souring can be derived by determining the concentrations of VFA in oil field waters. VFA are constantly being formed from syntrophic degradation of oil (16, 19, 20), and their concentrations reflect differences in rates of formation and use. Accumulation of up to 6 mM acetate was demonstrated in a bioreactor in which heavy MHGC oil served as the sole electron donor for the reduction of sulfate and nitrate (16). VFA accumulation was credited to preferential use of H2, formed during water-mediated fermentation of hydrocarbons (equations 1 and 2), by oil field SRB (16).

Thus, VFA are formed from oil components and are significant electron donors. As shown here, VFA have some specificity for different physiological processes. When present in excess, acetate and propionate were used preferentially for nitrate reduction, propionate for sulfate reduction, and butyrate for methanogenic fermentation (Fig. 1 to 3; see also Fig. S1 to S3). Interestingly, although the kinetics of VFA use and associated nitrate and/or sulfate reduction were much slower in microcosms than in the bioreactor, the effect of nitrate dosing was the same. In the bioreactor, injection of 0, 4, 8, and 13 mM nitrate resulted in 1.7, 2, 1.8, and 0.7 mM aqueous sulfide, whereas concentrations of 2, 2, 1.3, and 0.7 mM aqueous sulfide were seen in microcosms. Plots of the residual concentration of sulfide in the bioreactor effluent and of the injected nitrate concentration (Fig. 6) indicated that higher nitrate doses were needed to limit souring (the production of sulfide) with increased injection of VFA. The dose needed to eliminate all sulfide was approximately 80% of that required to oxidize all injected VFA to CO2 (Fig. 6, arrows, and equations 14 to 16). These results indicate that 20% of the VFA was used as the carbon source for biomass formation.

FIG 6.

Effect of increased injection of nitrate on the concentration of produced sulfide in bioreactor effluents. The injected electron donors were 3 mM (each) propionate, acetate, and butyrate (diamonds), propionate and acetate (squares), and propionate only (triangles). The nitrate doses required to oxidize these concentrations of electron donors to CO2 are indicated (↓).

The microbial community compositions (Table 3) indicated that Desulfobulbus was the prominent SRB, with a fraction of 1.8 to 14.0%, except in the amplicon library from microcosm 7PWb_S2V3, where it was only 0.2%. Desulfobulbus was also the most prominent SRB in a previous bioreactor study (37). Many species of this genus are able to use propionate as the electron donor for sulfate reduction (39). This is consistent with the physiology of these enrichments, which showed use of propionate as the electron donor for sulfate reduction in microcosms 2PW_S2V3, 4PW_S2V3, 7PWa_S2V3, and 13PW_S2V3 but not in 7PWb_S2V3 (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Microcosm 13PW_S2V3 had a high proportion of Syntrophomonas (Table 3: 14.0%), which is a potential syntrophic butyrate degrader forming hydrogen, formate, and acetate in syntrophic coculture with methanogens (17–19, 40). Enrichment E_S2B3 with 2 mM sulfate and 3 mM butyrate had a high fraction of Syntrophomonas (12.1%) and of the methanogen Methanobacterium (28.4%), indicating that this culture supported itself by methanogenic, syntrophic butyrate degradation at the time of sampling. This culture had the highest proportions of the SRB Desulfovibrio and Desulfofustis (Table 3: 0.6%), indicating that a syntrophic coculture of Syntrophomonas and these SRB may have catalyzed butyrate-dependent sulfate reduction earlier in this culture.

Amplicon libraries for enrichments with 2 mM sulfate, 3 mM VFA, and 4, 8, or 13 mM nitrate had high fractions of the hNRB Paracoccus (49 to 71.1%) and Thauera (8.4 to 42.2%). The fraction of Paracoccus increased with increasing concentrations of nitrate. Methanogens were minor components in enrichments with nitrate (Table 3). Desulfobulbus was also only a minor (0 to 1%) component in these libraries, and Syntrophomonas was not found. These results are consistent with the physiological data obtained for these microcosms.

VFA concentrations in oil field-produced waters do not define the nitrate dose needed to eliminate souring, as VFA are constantly formed from syntrophic degradation of oil and some hNRB can couple reduction of nitrate to oxidation of selected oil components, such as toluene (4, 36). Collectively, our data indicate that, when water amended with sulfate and nitrate is injected into the MHGC field, nitrate is reduced first, with toluene (4, 36), other oil components, and VFA as the electron donors. Sulfate is reduced further along the flow path, with H2, propionate, and other products from syntrophic oil degradation as substrates. Syntrophic degradation substrates, including butyrate and acetate, are used for further syntrophy and methanogenesis, which occurs even deeper in the reservoir. In the MHGC field, the overall outcome of this is that produced waters are free of nitrate and sulfate but contain some (0.12 mM) acetate (this study) and sulfide (3, 4). This is similar to what was observed in microcosms and in bioreactor effluents in this study. The latter had higher acetate concentrations, especially following nitrate treatments, which appeared to cause long-term inhibition of acetotrophic methanogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and enrichment cultures.

CSBA medium (pH 7.2 to 7.4) contained the following components (per liter): 7 g NaCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, 0.4 g MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.5 g KCl, 0.15 g CaCl2 · 2H2O, and 0.25 g NH4Cl (29). Following dissolution and autoclaving, the medium was cooled under a gas mixture of 90% (vol/vol) N2 and 10% CO2 (N2-CO2). The following were added (per liter) aseptically to cooled anoxic medium: 1 ml trace element solution, 1 ml selenite-tungstate solution, and 30 ml of 1 M NaHCO3 (41). CSBA medium was further amended with sulfate to 2 mM (CSBA-S) and with VFA to 3 mM (3 mM [each] acetate, propionate, and butyrate) for use in serum bottle tests and in a bioreactor. Alternatively, acetate and propionate, propionate only, or butyrate only was added (all to 3 mM). Medium (50 ml) was placed in 122-ml serum bottles, which were flushed with N2-CO2 for 5 min to remove oxygen from the headspace. The bottles were then sealed with butyl rubber stoppers and closed with aluminum caps. SRB enrichment culture E2PW was made by inoculating 5 ml of produced water 2PW from the MHGC field (3) into 50 ml of CSBA containing 5 mM sulfate and 3 mM VFA. Enrichments were incubated for 14 days at room temperature (22°C) and transferred at least twice prior to use as an inoculum for serum bottles and the bioreactor.

Kinetics of use of VFA by MHGC oil field-produced waters.

A schematic of the MHGC field, indicating “make-up” water sources (water used to replace the volume of produced oil in order to maintain the reservoir pressure), water plants, injection wells, and producing wells, sampled monthly, has been presented elsewhere (3). Volumes (5 ml) of produced waters 2PW, 4PW, 7PW, and 13PW (3) were inoculated into 122-ml serum bottles containing 50 ml of CSBA or 50 ml of CSBA-S medium and 3 mM VFA, 3 mM propionate, or 3 mM butyrate. Before inoculation, the medium was flushed with N2-CO2 for 5 min to remove oxygen. Each experimental condition was set up in duplicate, and reaction mixtures were incubated at 22°C. Aliquots (0.5 ml) of liquid samples were removed periodically with a 1-ml syringe flushed with N2-CO2 to determine concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, nitrate, nitrite, or VFA. The sulfide concentration was analyzed immediately after each sampling. The remaining amounts of the samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants were frozen at −20°C for further analysis. Aliquots (0.2 ml) of headspace gas were analyzed for methane.

Effect of nitrate on the kinetics of VFA use by hNRB, SRB, and methanogens.

CSBA-S medium (50 ml) with 3 mM VFA or its components was amended with nitrate to 0, 4, 8, or 13 mM and inoculated with 5 ml of SRB enrichment E2PW. Incubation and sampling were performed as described above.

Comparison of most-probable numbers of lactate- and propionate-utilizing SRB.

Aliquots (100 μl) of MHGC field samples collected in July 2016 were serially diluted in triplicate in 48-well microtiter plates containing Postgate medium B (900 μl). Postgate medium B (pH 7.0 to 7.5) contains the following components (g liter−1): KH2PO4 (0.5), NH4Cl (1.0), CaSO4 (1.0), MgSO4 · 7H2O (2.0), sodium lactate (4.0 [60% {wt/wt}]), yeast extract (1.0), ascorbic acid (0.1), thioglycolate (0.1), and FeSO4 · 7H2O (0.5). For medium in which propionate served as the electron donor for sulfate reduction, sodium lactate was replaced by 2.2 g/liter of sodium propionate. Microtiter plates were sealed with a Titer-Tops polyethylene membrane. The samples were incubated anaerobically for 3 weeks at 30°C in an anaerobic hood with an atmosphere of 5% H2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2. Wells exhibiting a black FeS precipitate were scored as positive. Most-probable numbers (MPNs) were derived from the data using appropriate statistical tables (34). Because the microtiter plate wells had a headspace of only 0.6 ml, the available H2 would reduce maximally 0.3 mM sulfate, whereas the concentrations of lactate (21.4 mM) and propionate (22.9 mM) would reduce 10.7 and 17.3 mM sulfate, respectively, of the 17.3 mM sulfate present in the medium. The MPN method counted, therefore, lactate- or propionate-oxidizing SRB, not H2-oxidizing SRB.

Bioreactor setup and startup.

A 60-ml syringe column (2.5 by 16 cm) was fitted with glass wool and polymeric mesh at the bottom, packed with sand with an average grain size of 225 μm (Sigma-Aldrich), and then fitted with one layer of polymeric mesh at the top (37). All materials, including the sand, tubing, glass wool, and polymeric mesh, were autoclaved before use. The pore volume (PV; 28 ml) of the column was determined by flooding with CSBA medium using a multichannel peristaltic pump (Minipuls-3; Gilson Inc.) (8-channel head) and calculating the difference between the wet and dry weights of the column. The column had 22% liquid porosity and an effective area of 1.1 cm2 (Aeff = 0.22 ëR2). Three-way valves were placed at the influent and effluent ports for sampling. The flow rate was 42 ml/day, with a retention time of 16 h. For startup, 0.5 PV of SRB enrichment E2PW was pumped into the column via the influent port. The bioreactor was shut down and incubated without flow for 1 week to allow SRB growth. CSBA-S medium with 3 mM VFA was then injected at 21 ml/day. When the 2 mM sulfate in this medium was completely reduced, the flow rate was increased to 42 ml/day and kept at this rate throughout the remaining operation. The bioreactor was run at room temperature (22°C), with the operating conditions being changed when a new steady state was established as indicated by constant concentrations of sulfate, sulfide, nitrate, nitrite, and VFA.

DNA extraction.

Samples of enrichments (3 ml) taken at the end of the serum bottle incubations and of bioreactor effluents (5 ml) were centrifuged for 5 min at 13,200 rpm at 4°C. The cell pellets were collected for DNA isolation using a Fast DNA Spin kit for soil and a Fast Prep instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentrations of extracted DNA were quantified using a Qubit fluorimeter (Invitrogen).

Pyrosequencing.

Pyrosequencing of 16S amplicons was done for 15 enrichments and 7 bioreactor effluents. PCR amplification involved 35 cycles using 16S primers 926Fw (AAACTYAAAKGAATTGRCGG) and 1392R (ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC), followed by 15 cycles with FLX titanium primers 454T_RA_X and 454T_FwB, as described elsewhere (42). Purified 16S amplicons (∼125 ng) were sequenced at the Genome Quebec and McGill University Innovation Centre (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) with a Genome Sequencer FLX instrument, using GS FLX Titanium Series kit XLR 70 (Roche Diagnostics Corporation). Data analysis was conducted with Phoenix 2, a 16S rRNA data analysis pipeline, developed in-house (43). The high-quality sequences which remained following quality control and chimeric sequence removal were clustered into operational taxonomic units at a distance of 3% by using the average linkage algorithm (38). A taxonomic consensus of all representative sequences from each of these was derived from the recurring species within 5% of the best bit score from a BLAST search against small-subunit (SSU) reference data set SILVA102 (44). Amplicon libraries were clustered into a Newick-formatted tree with the unweighted pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) algorithm, with the distance between libraries calculated using the thetaYC coefficient (45) as a measurement of their similarity in the Mothur software package (38, 46). The Newick format of the sample relation tree was visualized using Dendroscope (47). The entire set of the raw reads is available from the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI (see Materials and Methods).

Chemical analyses.

Aqueous sulfide concentrations were determined colorimetrically with N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (48). Ammonium was measured colorimetrically at 635 nm using the indophenol blue method (49). Sulfate, nitrate, and nitrite were assayed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), using a Waters 600E HPLC instrument equipped with a Waters 423 conductivity detector, a Waters 2489 UV/VIS detector (wavelength set at 200 nm), and a Waters IC-PAK Anion HC column (Waters, Japan) (4.6 by 150 mm) with a mobile phase flow rate of 2 ml/min. The mobile phase contained the following components (per liter of water): 20 ml butanol, 120 ml acetonitrile, and 20 ml borate/gluconate concentrate (boric acid, 18 g/liter; sodium d-gluconate, 16 g/liter; sodium tetraborate decahydrate, 25 g/liter; glycerol, 250 ml/liter). The concentrations of lactate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate were determined using an HPLC instrument equipped with a Waters 2489 UV/visible light (UV/VIS) detector at 210 nm and a Prevail Organic Acids 5u column (Alltech) (250.0 by 4.6 mm) with a mobile phase of 25 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.5) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Methane production was detected by injection of 0.2 ml of culture headspace into an HP 5890 gas chromatograph equipped with a stainless steel Porapak R 80/100 column (0.049 by 5.49 m). Injector and detector temperatures were 150 and 200°C, respectively (42).

Chemical reactions considered in Results and Discussion.

Sequential beta-oxidation of octadecanoate to acetate and H2 was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

Degradation of heptadecanoate to acetate, propionate, and H2:

| (2) |

Conversion of butyrate to two acetate and H2 (final step of equation 1):

| (3) |

Reduction of CO2 with H2:

| (4) |

Reduction of sulfate with H2:

| (5) |

Reduction of sulfate coupled to oxidation of propionate to acetate and CO2:

| (6) |

Fermentation of butyrate to two acetates coupled to methanogenesis:

| (7) |

Reduction of sulfate coupled to oxidation of butyrate to two acetates:

| (8) |

Combination of equations 7 and 8:

| (9) |

Redox half-reactions for oxidation of butyrate, propionate, and acetate to CO2:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

Redox half-reaction for reduction of nitrate:

| (13) |

Complete oxidation of 3 each of acetate, propionate, and butyrate to equation 14 CO2:

| (14) |

Complete oxidation of 3 each of acetate and propionate to CO2:

| (15) |

Complete oxidation of 3 propionate to CO2:

| (16) |

Incomplete oxidation of propionate to acetate and CO2:

| (17) |

In equations 13 to 17, we have assumed that N2 is the sole product of nitrate reduction by MHGC consortia. In the presence of excess electron donors, neither nitrite (NO2−) nor nitrous oxide (N2O) accumulated under the tested conditions (results not shown). Nitrate was not reduced to ammonium (30).

Accession number(s).

The entire set of the raw reads is available from the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRX684441.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rhonda Clark for administrative support and to Baker Hughes and Enerplus Corporation and Suncor for providing the field samples used in this study.

This work was supported through a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Industrial Research Chair awarded to G.V., who was also supported by Baker Hughes, BP, Computer Modeling Group Ltd., ConocoPhillips, Intertek, Dow Microbial Control, Enbridge, Enerplus Corporation, Oil Search Limited, Shell Global Solutions International, Suncor Energy Inc., Yara Norge, and Alberta Innovates Energy and Environment Solutions (AIEES).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02983-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sunde E, Torsvik T. 2005. Microbial control of hydrogen sulfide production in oil reservoirs, p 201–213. In Ollivier B, Magot M (ed), Petroleum microbiology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vance I, Thrasher DR. 2005. Reservoir souring: mechanisms and prevention, p 123–142. In Ollivier B, Magot M (ed), Petroleum microbiology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voordouw G, Grigoryan AA, Lambo A, Lin SP, Park HS, Jack TR, Coombe D, Clay B, Zhang F, Ertmoed R, Miner K, Arensdorf JJ. 2009. Sulfide remediation by pulsed injection of nitrate into a low temperature Canadian heavy oil reservoir. Environ Sci Technol 43:9512–9518. doi: 10.1021/es902211j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal A, Park HS, Nathoo S, Gieg LM, Jack TR, Miner K, Ertmoed R, Benko A, Voordouw G. 2012. Toluene depletion in produced oil contributes to souring control in a field subjected to nitrate injection. Environ Sci Technol 46:1285–1292. doi: 10.1021/es203748b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telang AJ, Ebert S, Foght JM, Westlake DWS, Jenneman GE, Gevertz D, Voordouw G. 1997. The effect of nitrate injection on the microbial community in an oil field as monitored by reverse sample genome probing. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:1785–1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene EA, Hubert C, Nemati M, Jenneman GE, Voordouw G. 2003. Nitrite reductase activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria prevents their inhibition by nitrate-reducing, sulfide-xidizing bacteria. Environ Microbiol 5:607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaster KM, Grigoriyan A, Jenneman G, Voordouw G. 2007. Effect of nitrate and nitrite on sulfide production by two thermophilic, sulfate-reducing enrichments from an oil field in the North Sea. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 75:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0796-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandbeck K, Hitzman DO. 1995. Biocompetitive exclusion technology: a field system to control reservoir souring and increase production, p 311–320. In Bryant R, Sublette KL (ed), Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery and Related Biotechnology for Solving Environmental Problems. National Technical and Information Services, Springfield, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubert C, Voordouw G. 2007. Oil field souring control by nitrate reducing Sulfurospirillum spp. that outcompete sulfate-reducing bacteria for organic electron donors. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2644–2652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02332-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barth T. 1991. Organic acids and inorganic ions in waters from petroleum reservoirs, Norwegian continental shelf: a multivariate statistical analysis and comparison with American reservoir formation waters. Appl Geochem 6:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0883-2927(91)90059-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gittel A, Sørensen KB, Skovhus TL, Ingvorsen K, Schramm A. 2009. Prokaryotic community structure and sulfate reducer activity in water from high-temperature oil reservoirs with and without nitrate treatment. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7086–7096. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01123-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller RF, Nielsen PH. 1996. Characterization of thermophilic consortia from two souring oil reservoirs. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:3083–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pham VD, Hnatow LL, Zhang S, Fallon RD, Jackson SC, Tomb JF, DeLong EF, Keeler SJ. 2009. Characterizing microbial diversity in production water from an Alaskan mesothermic petroleum reservoir with two independent molecular methods. Environ Microbiol 11:176–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunsmore B, Youldon J, Thrasher DR, Vance I. 2006. Effects of nitrate treatment on a mixed species, oil field microbial biofilm. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 33:454–462. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuijvenhoven C, Noirot JC, Hubbard P, Oduola L. 2007. One year experience with the injection of nitrate to control souring in Bonga deepwater development offshore Nigeria. SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, Houston, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callbeck CM, Agrawal A, Voordouw G. 2013. Acetate production from oil under sulfate-reducing conditions in bioreactors injected with sulfate and nitrate. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:5059–5068. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01251-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieber SR, Le HM, McInerney M. 2014. The importance of hydrogen and formate transfer for syntrophic fatty, aromatic and alicyclic metabolism. Environ Microbiol 16:177–188. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolfing J. 2014. Thermodynamic constraints on syntrophic acetate oxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1539–1541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03312-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray ND, Sherry A, Grant RJ, Rowan AK, Hubert CRJ, Callbeck CM, Aitken CM, Jones DM, Adams JJ, Larter SR, Head IM. 2011. The quantitative significance of Syntrophaceae and syntrophic partnerships in methanogenic degradation of crude oil alkanes. Environ Microbiol 13:2957–2975. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zengler K, Richnow HH, Rosselló-Mora R, Michaelis W, Widdel F. 1999. Methane formation from long-chain alkanes by anaerobic microorganisms. Nature 401:266–269. doi: 10.1038/45777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolfing J, Larter SR, Head IM. 2008. Thermodynamic constraints on methanogenic crude oil biodegradation. ISME J 2:442–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elefsiniotis P, Wareham DG. 2007. Utilization patterns of volatile fatty acids in the denitrification reaction. Enzyme Microb Technol 41:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YG, Randall AA, McCue T. 2004. The efficiency of enhanced biological phosphorus removal from real wastewater affected by different ratios of acetic to propionic acid. Water Res 38:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du ZW, Li HR, Gu TY. 2007. A state of the art review on microbial fuel cells: a promising technology for wastewater treatment and bioenergy. Biotechnol Adv 25:464–482. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu WZ, Huang SC, Zhou AJ, Zhou GY, Ren NQ, Wang AJ, Zhuang GQ. 2012. Hydrogen generation in microbial electrolysis cell feeding with fermentation liquid of waste activated sludge. Int J Hydrogen Energy 37:13859–13864. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigoryan AA, Cornish SL, Buziak CB, Lin SP, Cavallaro A, Arensdorf JJ, Voordouw G. 2008. Competitive oxidation of volative fatty acids by sulfate- and nitrate-reducing bacteria from an oil field in Argentina. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:4324–4335. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00419-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bok FAM, Stams AJM, Dijkema C, Boone DR. 2001. Pathway of propionate oxidation by a syntrophic culture of Smithella propionica and Methanospirillum hungatei. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1800–1804. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1800-1804.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller N, Worm P, Schink B, Stams AJ, Plugge CM. 2010. Syntrophic butyrate and propionate oxidation process: from genomes to reaction mechanisms. Environ Microbiol Rep 2:489–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hubert C, Nemati M, Jenneman G, Voordouw G. 2003. Containment of biogenic sulfide production in continuous up-flow packed-bed bioreactors with nitrate or nitrite. Biotechnol Prog 19:338–345. doi: 10.1021/bp020128f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shartau SLC, Yurkiw M, Lin SP, Grigoryan AA, Lambo A, Park HS, Lomans BP, van der Biezen E, Jetten MSM, Voordouw G. 2010. Ammonium concentrations in produced waters from a mesothermic oil field subjected to nitrate injection decrease through formation of denitrifying biomass and anammox activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4977–4987. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00596-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zellner G, Stackebrandt E, Messner P, Tindall BJ, Conway de Macario E, Kneifel H, Sleytr UB, Winter J. 1989. Methanocorpusculaceae fam. nov., represented by Methanocorpusculum parvum, Methanocorpusculum sinense spec. nov. and Methanocorpusculum bavaricum spec. nov. Arch Microbiol 151:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imachi H, Sakai S, Nagai H, Yamaguchi T, Takai K. 2009. Methanofollis ethanolicus sp. nov., an ethanol-utilizing methanogen isolated from a lotus field. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 59:800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu JX, Liu XL, Dong XZ. 2011. Methanobacterium movens sp. nov. and Methanobacterium flexile sp. nov., isolated from lake sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:2974–2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Voordouw G. 2015. Primers for dsr genes and most probable number method for detection of sulfate-reducing bacteria in oil reservoirs, p 1–9. In McGenity T, Timmis K, Nogales B (ed), Hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology protocols. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. doi: 10.1007/8623_2015_72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fida TT, Chen C, Okpala G, Voordouw G. 2016. Implications of limited thermophilicity of nitrite reduction for control of sulfide production in oil reservoirs. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:4190–4199. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00599-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambo AJ, Noke K, Larter SR, Voordouw G. 2008. Competitive, microbially-mediated reduction of nitrate with sulfide and aromatic oil components in a low-temperature, western Canadian oil reservoir. Environ Sci Technol 42:8941–8946. doi: 10.1021/es801832s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callbeck CM, Dong XL, Chatterjee I, Agrawal A, Caffrey SM, Sensen CW, Voordouw G. 2011. Microbial community succession in a bioreactor modeling a souring low-temperature oil reservoir subjected to nitrate injection. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91:799–810. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schloss PD, Westcott SL. 2011. Assessing and improving methods used in operational taxonomic unit-based approaches for 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:3219–3226. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02810-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widdel F, Pfennig N. 1982. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. II. Incomplete oxidation of propionate by Desulfobulbus propionicus gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch Microbiol 131:360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu PF, Qiu QF, Lu YH. 2011. Syntrophomonadaceae-affiliated species as active butyrate-ultilizing syntrophs in paddy field soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:3884–3887. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00190-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Widdel F, Bak F. 1992. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. In Balows A, Trüper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer KH (ed), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed, vol 4 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park HS, Chatterjee L, Dong X, Wang SH, Sensen CW, Caffrey SM, Jack TR, Boivin J, Voordouw G. 2011. Effect of sodium bisulfite injection on the microbial community composition in failed pipe sections of a brackish-water-transporting pipeline. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:6908–6917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05891-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soh J, Dong X, Caffrey SM, Voordouw G, Sensen CW. 2013. Phoenix 2: a locally installable large-scale 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis pipeline with Web interface. J Biotechnol 167:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. 2007. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35:7188–7196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yue JC, Clayton MK. 2005. A similarity measure based on species proportions. Commun Stat Theory Methods 34:2123–2131. doi: 10.1080/STA-200066418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Thomas R, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huson D, Richter D, Rausch C, Dezulian T, Franz M, Rupp R. 2007. Dendroscope: an interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics 8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trueper HG, Schlegel HG. 1964. Sulfur metabolism in Thiorhodeaceae. I. Quantitative measurements on growing cells of Chromatium okenii. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 30:225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Staden JF, Taljaard RE. 1997. Determination of ammonia in water and industrial effluent streams with the indophenol blue method using sequential injection analysis. Anal Chim Acta 344:281–289. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(96)00523-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.