Abstract

Purpose

The arthroscopic assisted ankle arthrodesis (AAAA) is a minimally invasive procedure for end-stage ankle arthritis with numerous benefits like faster time of union, insignificant blood loss, less morbidity, less infection rate, and less soft tissue complications. A shorter hospital stay decreases the cost and results in early mobilization compared to open methods. We present a retrospective series of 32 patients, who underwent AAAA during a period of 8 years.

Methods

Thirty-two patients were reviewed retrospectively from 2008 to 2015. We calculated the Karlsson and Peterson ankle function scoring system pre-operatively and at 3 and 12 months after the surgery, in all the patients. All the patients were operated using arthroscopic denuding of degenerated cartilage followed by percutaneous criss-cross screw fixation through the tibia crossing the ankle joint into the talus.

Results

The mean age at operation time was 43.7 years. Four patients were excluded from the study. 18 were male, and 10 were female patients. All the 28 cases were followed up for a minimum of 1 year (mean 1.7 years). The average time to union was 14 weeks. The complications included four cases requiring removal of a screw for prominence, and one superficial infection. There were 20 (71.4%) patients with excellent, 4 (14.2%) with good, 3 (10.7%) with fair and 1 (3.5%) with poor clinical outcome. The average tourniquet time for the surgery was 70 min. The mean hospital stay was 2 days. The average Karlsson and Peterson's scoring was 32.71 pre-operatively and 74.10 and 89.00 postoperatively measured at 3 months and 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion

With the high incidence of soft-tissue problems and the young age of onset of post-traumatic arthritis, AAAA remains the treatment of choice in most cases with numerous advantages over open technique.

Keywords: Ankle arthritis, Ankle arthrodesis, Ankle arthroscopy

1. Introduction

Ankle arthrodesis is a recognized surgical treatment for end-stage ankle arthritis in young patients, who are resistant to conservative treatment.1 Nowadays, arthroscopic assisted ankle arthrodesis (AAAA) is becoming popular because it is a minimally invasive procedure and have shown good clinical outcomes. Between the open versus arthroscopic techniques, the rate of the union is almost the same. However, the benefits of the arthroscopic method are numerous like faster time of union, insignificant blood loss, less morbidity, less infection rate, less soft tissue complications, a shorter hospital stay that decreases the cost, and results in early mobilization.2, 3, 4 In patients with local skin problems where an open technique cannot be used, the arthroscopic technique provides an additional benefit and become a useful alternative procedure (Table 1). We present a retrospective series of 32 patients, who underwent AAAA during a period of 8 years.

Table 1.

Pros and cons of open versus arthroscopic assisted ankle arthrodesis.

| Open ankle arthrodesis | Arthroscopy assisted ankle arthrodesis |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Advantages |

| 1. Better visibility | 1. Lesser blood loss |

| 2. Ability to correct severe deformities | 2. Faster time of union |

| 3. Ability to deal with significant bone loss | 3. Lesser morbidity |

| 4. Lesser soft tissue complications | |

| 5. Shorter hospital stay | |

| 6. Early mobilization | |

| 7. Lesser infection rate | |

| 8. Can be performed in ankles with skin problem | |

| Disadvantages | Disadvantages |

| 1. Significant blood loss | 1. Lesser access to the joint |

| 2. Delayed mobilization | 2. Lesser ability to correct severe deformities |

| 3. Higher infection rate | |

| 4. Longer hospital stay | |

| 5. Cannot be performed in ankles with skin problem | |

2. Materials and methods

We reviewed all 32 patients who have had AAAA from 2008 to 2015 from our database. Out of 32, four patients were excluded from this study due to incomplete, and mandatory follow-up of 1 year. Weight-bearing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were taken preoperatively (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) to identify the degree of deformation. We calculated the ankle function scoring (Karlsson and Peterson scoring system5 for ankle function) pre-operatively, at 3 and 12 months after the surgery, in all the patients.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative X-ray right ankle anteroposterior view showing advanced arthritis.

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative X-ray right ankle lateral view showing advanced arthritis.

2.1. Surgical procedure

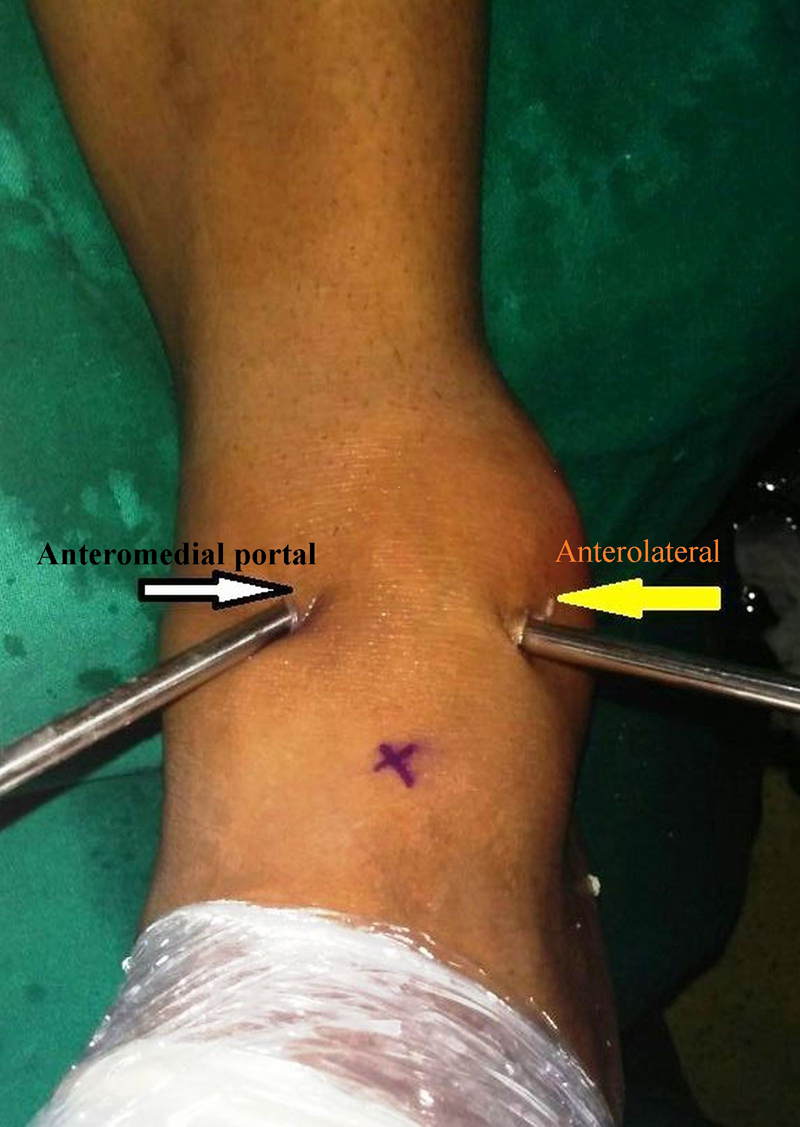

All of these procedures were done under spinal anesthesia. The position of the patient was kept supine on a conventional surgical table. Joint distraction was not used in any of these cases. A pneumatic tourniquet was used in all the cases during the whole procedure. Drapping, the limb above the knee, allowed complete visualization of the leg. The anatomical landmarks of the ankle, especially both malleoli and the joint line were identified and marked before the incision (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Anteromedial and anterolateral arthroscopic portals for ankle arthroscopy.

2.2. Arthroscopic portals and procedure

We had used an anterolateral and an anteromedial arthroscopic portals for the ankle arthroscopy, using 4 mm 30° arthroscope. The anteromedial portal was first made using a trocar and cannula, and the arthroscope was then inserted. The lateral portal was created under direct vision by entering an intravenous needle lateral to the extensor digitorum tendons.6 The anatomical relations of anterior approaches to the ankle joint was carefully observed, to avoid iatrogenic injuries to the neighboring structures. The ankle joint was kept distended with normal saline, using a pressure bag. The remaining articular cartilage was shaved using arthroscopic 5 mm shaver and the underlying burned subchondral bone was roughened until the bleeding surface was achieved, using arthroscopic burr. After freshening the joint surfaces, the ankle joint was assessed by an image intensifier, intraoperatively. We preferred the position for arthrodesis in neutral dorsiflexion, 5–10° of external rotation, 0–5° of valgus. AAAA helped us to minimize shortening of the limb, by minimal bone removal for arthrodesis.

2.3. Correction of severe deformities

To have a good vision of capsular insertion proper debridement of the lateral gutters were done. Moreover, for the correction of severe deformities in the ankle, a larger release of the capsule was needed to mobilize and oppose the surfaces of tibia and talus to achieve a proper anatomical alignment.

2.4. Fixation

After correcting the axis of the ankle, two tibiotalar guidewires were inserted in a criss-cross direction to cross the ankle joint, under the control of image intensifier. The first wire was inserted anterolaterally about 5 cm above the joint line. The position of insertion is at an angle of 10–20° to reach the dorsal half of talus. The structures that are more prone to be damaged are sural nerve and peroneus tendon. The position for inserting the second wire is at a posteromedial position just in front of the tibialis posterior tendon. These two wires are inserted in a criss-cross position to provide better stability. Appropriate length 7.0 mm cancellous screws with 16 mm thread was used to achieve fixation across the ankle joint.

2.5. Postoperative protocol

For 2 weeks the leg was immobilized in a below knee slab and after stitch removal, below knee cast was applied for 6 weeks. Partial weight bearing was allowed with the help of axillary crutches. X-rays were done in immediate post-operative period, at the end of 3 months and 1 year (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). Patients were allowed full weight bearing gradually. A short course of physiotherapy was required in order to gain foot movements and proprioception, particularly in older patients.

Fig. 4.

One year post-operative X-ray right ankle anteroposterior view showing fused ankle with two cross screws in situ.

Fig. 5.

One year post-operative X-ray right ankle lateral view showing fused ankle.

3. Results

We reviewed 32 patients who have had AAAA from 2008 to 2015 from our database. Out of 32, four patients were excluded from this study due to incomplete, and mandatory follow-up of one year. Hence, 28 patients were examined in this series. The mean age at the time of surgery was 43.7 years (range 20–76 years). Out of 28 included patients, 18 were males, and 10 were females. Preoperative diagnosis was post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the majority of cases (19), followed by primary osteoarthritis (6), inflammatory arthropathy (2), and avascular necrosis of talus (1) case (Table 2). The average pre-operative symptoms’ duration was 15.9 months. All the 28 cases were followed up for a minimum of 1 year (mean 1.7 years). The average time to union was 14 weeks. Arthrodesis was achieved in all the cases. Complications include four cases requiring screw removal for prominence, and one superficial infection which was managed conservatively. There were 20 (71.4%) patients with excellent, 4 (14.2%) with good, 3 (10.7%) with fair and 1 (3.5%) with poor clinical outcome. Out of total 28 patients, the right side was involved in 17 cases. The average tourniquet time for the surgery was 70 min (range 60–100 min). The mean hospital stay was 2 days (range 1–4 days). The nonunion case was diagnosed as having avascular necrosis (Table 3).

Table 2.

Indications for ankle joint arthrodesis.

| Preoperative diagnosis | Number and percentage |

|---|---|

| Post-traumatic arthritis | 19 (67.85%) |

| Primary OA | 6 (21.42%) |

| Inflammatory arthropathy | 2 (7.14%) |

| Avascular necrosis | 1 (3.57%) |

Table 3.

Demographics of the patient population of this study.

| No. | Age/year | Sex | Pre-op. diagnosis | Duration of symptoms/month | Pre-op. score | Post-op score |

Duration of follow up/month | Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 1 year | ||||||||

| 1 | 52 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 11.0 | 42.0 | 67.0 | 90.0 | 18.0 | NA |

| 2 | 34 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 09.5 | 32.0 | 65.0 | 89.0 | 14.0 | Screw prominence |

| 3 | 21 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 13.0 | 47.0 | 65.0 | 92.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 4 | 76 | M | Primary OA | 24.0 | 32.0 | 75.0 | 89.0 | 21.0 | Infection |

| 5 | 45 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 12.0 | 29.0 | 60.0 | 92.0 | 36.0 | NA |

| 6 | 53 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 14.0 | 29.0 | 62.0 | 89.0 | 18.0 | NA |

| 7 | 44 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 10.0 | 32.0 | Lost | Lost | Lost | NA |

| 8 | 32 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 12.0 | 42.0 | 62.0 | 90.0 | 16.0 | NA |

| 9 | 28 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 11.0 | 24.0 | 75.0 | 87.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 10 | 28 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 23.0 | 37.0 | 77.0 | 90.0 | 16.0 | NA |

| 11 | 25 | M | Avascular necrosis | 24.0 | 34.0 | Lost | Lost | Lost | NA |

| 12 | 31 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 14.5 | 30.0 | 69.0 | 87.0 | 14.0 | NA |

| 13 | 33 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 11.0 | 22.0 | 70.0 | 79.0 | 21.0 | Screw prominence |

| 14 | 56 | M | Primary OA | 39.0 | 34.0 | 75.0 | 90.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 15 | 71 | M | Primary OA | 12.0 | 29.0 | 70.0 | 89.0 | 33.0 | NA |

| 16 | 49 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 09.5 | 34.0 | 65.0 | 87.0 | 21.0 | NA |

| 17 | 45 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 14.0 | 29.0 | 70.0 | 90.0 | 28.0 | NA |

| 18 | 37 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 22.0 | 32.0 | 62.0 | 92.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 19 | 66 | M | Primary OA | 17.0 | 30.0 | 75.0 | 90.0 | 30.0 | NA |

| 20 | 61 | M | Primary OA | 27.0 | 22.0 | 77.0 | 87.0 | 14.0 | Screw prominence |

| 21 | 29 | M | Post-traumatic arthritis | 21.0 | 37.0 | Lost | Lost | Lost | NA |

| 22 | 20 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 11.0 | 42.0 | 62.0 | 90.0 | 36.0 | NA |

| 23 | 26 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 13.0 | 34.0 | 70.0 | 90.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 24 | 65 | F | Primary OA | 28.0 | 29.0 | 62.0 | 85.0 | 19.0 | NA |

| 25 | 54 | F | Inflammatory arthropathy | 44.0 | 35.0 | 65.0 | 89.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 26 | 48 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 34.5 | 40.0 | 75.0 | 95.0 | 12.0 | NA |

| 27 | 59 | F | Primary OA | 32.0 | 34.0 | 70.0 | 92.0 | 30.0 | Screw prominence |

| 28 | 40 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 12.0 | 24.0 | 62.0 | 87.0 | 24.0 | NA |

| 29 | 47 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 42.0 | 24.0 | Lost | Lost | Lost | NA |

| 30 | 53 | F | Primary OA | 13.0 | 35.0 | 75.0 | 90.0 | 36.0 | NA |

| 31 | 33 | F | Post-traumatic arthritis | 23.0 | 24.0 | 70.0 | 85.0 | 32.0 | NA |

| 32 | 38 | F | Inflammatory arthropathy | 48.0 | 47.0 | 75.0 | 90.0 | 24.0 | NA |

| Average | 43.7 | 20.3 | 32.71 | 74.10 | 89.00 | 20.80 | |||

The average Karlsson and Peterson's scoring was 32.71 pre-operatively, 74.10 and 89.00 postoperative measured at 3 months and 1 year follow-up.

4. Discussion

Arthrodesis of the ankle is indicated in cases of painful arthritis, where conservative treatment has been tried and failed. Indications for ankle joint arthrodesis include post-traumatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Charcot's arthropathy, seronegative arthritis, avascular necrosis of talus, after a failed total ankle replacement, and infective arthritis.7

Until recent past, the ankle arthrodesis was performed using various open techniques. Since Charnley introduced the concept of compression ankle arthrodesis, more than 30 techniques and countless modifications have been described.8 Regardless of the specific technique used, some general principles need to be taken into consideration for good results such as to create broad, flat, cancellous surfaces that are placed in apposition to allow fusion to occur; the arthrodesis site should be stabilized with rigid internal fixation, if possible, or with external fixation. Achieving this in patients with osteoporotic bones may be difficult. It is important that the hind foot should be aligned to the leg and the forefoot to the hind foot to create a plantigrade foot.

There are various approaches for ankle arthrodesis including anterior, transmalleolar and posterior approach.9 Fixation also can be obtained by different methods including compression with an external fixator, large cancellous screws, or intramedullary fixation. Charnley first described the use of an external fixation device for compression ankle arthrodesis whereas Calandruccio designed a triangular frame to produce compression and control motion in all three planes. A modified design, the Calandruccio II compression device (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tenn), is easier to apply and allows more latitude in pin placement to avoid compromised areas of skin or bone. Ring or circular external fixators also have been used to minimize pin track infection, but they are cumbersome for the patient, require careful pin track care, and are expensive. Proponents of internal fixation cite several advantages over external fixation, including ease of insertion, patient convenience, comparable rates of delayed union, malunion, nonunion, and infection; and greater resistance to shear stress.

Braly et al. and Wang et al. reported good results with the use of a lateral T-plate and cited advantages of the better cosmetic result, quicker fusion, and fewer complications than with other fixation methods.10, 11 Rowan and Davey also reported a high fusion rate (94%) and few complications with the use of anterior AO T-plates in 33 patients.12 Gruen and Mears used a posterior blade plate for late reconstruction of five ankles with complex deformity.13

Cancellous screws in various configurations are the most commonly used for internal fixation. Swärd et al. described a technique of posterior internal compression using two posterior cancellous screws with washers inserted obliquely, across the tibiotalar joint and down into the neck of the talus.14 They added autologous cancellous bone chips from the iliac crest packed into a deep slot cut in the joint.

The AAAA is commonly utilized nowadays by the arthroscopic surgeons. We were able to perform arthroscopy-assisted ankle surgery in all cases requiring an isolated ankle arthrodesis, without using any joint distraction. It is recommended to prepare both tibial and talar articular surfaces by denuding the cartilage and to use two crossed short threaded cancellous screws.15 We feel that talofibular fusion is not always essential, and we only cleared the lateral side (a talofibular aspect of joint) enough to allow apposition of the tibiotalar surfaces.

The absolute contraindications for arthrodesis include active infection, active Charcot's neuroarthropathy, avascular necrosis of talus with >30% involvement of talus because it causes nonunion after arthrodesis.16 The relative contraindications for AAAA are chronic smoker patient, varus or valgus deformity >15–20°.

Performing an AAAA is a technically challenging surgery and requires expertise in arthroscopic procedures. The surgeon must have the skill and resources to change the technique to an open fusion if necessary arises intraoperatively, although we did not need to do so in any of our cases in this series. We agree with the reported advantages of the arthroscopic technique include faster time of union, in significant blood loss, less morbidity, less infection rate, less soft tissue complications, shorter hospital stay, and early mobilization. In the patients with compromised skin and soft tissue problems over the ankle, this technique allows fusion surgery, in a safer manner. Traditionally joint distractor has been used intraoperatively to distract the joint, but in our series we have managed to perform the surgery without using the distractor by simply distending the joint using normal saline under pressure using pressure bag. It saves extra time and is associated with fewer complications.

The time of union is found to be less in this technique compared to open method.17 It can be because the periosteal stripping is not necessary for this method and the local circulation is not disturbed. After arthroscopic arthrodesis, the mean time for the union may be as short as 9 weeks. Although four (14.28%) patients required removal of their screws due to prominence, it is a simple procedure.

After ankle joint fusion, there is a compensatory increase in the movement of the surrounding joints of the foot. Subtalar degenerative changes are commonly seen in patients following ankle fusion, less common talonavicular, and rarely calcaneocuboid degenerative changes are seen.18, 19, 20

We have compared some parameters of our study with another similar study from the literature. Winson et al. have the largest series. Dent et al. did not analyze the outcome in his study. Gougoulias et al. has higher complications rate of 30.8% in his study (Table 4).1, 16, 21, 22

Table 4.

Comparison of various published studies on AAAA.

| No. of cases | Outcome |

Mean follow-up | Mean time of union | Complications | Distractor used | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | ||||||

| Vaishya et al. | 32 | 20 (71.4%) | 4 (14.2%) | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (3.5%) | 12 months | 14 weeks | 5 (17.5%) | Not used |

| Winson et al. | 116 | 48 (46.1%) | 35 (33.6%) | 10 (9.6%) | 11 (10.5%) | 18 months | 12 weeks | 30 (25.8%) | Used |

| Dent et al. | 7 | 16 months | 16 weeks | 0 (0%) | Used | ||||

| Gougoulias et al. | 78 | 62 (79.5%) | 14 (17.9%) | 2 (2.6%) | 21.1 months | 12.5 weeks | 24 (30.8%) | Used | |

| Zvijac et al. | 21 | 9 (42.8%) | 11 (52.3%) | 1 (4.7%) | 34 months | 8.9 weeks | 1 (4.7%) | Not used | |

The results of total ankle replacement are improving day by day but still its long-term survivorship is not very good. With the high incidence of soft-tissue problems and the young age of onset of post-traumatic arthritis, on the basis of clinical outcome in our study we believe that an arthrodesis remains the treatment of choice in most cases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Contributor Information

Raju Vaishya, Email: raju.vaishya@gmail.com.

Ahmad Tariq Azizi, Email: dr.azizitariq@gmail.com.

Amit Kumar Agarwal, Email: amitorthopgi@yahoo.co.in.

Vipul Vijay, Email: dr_vipulvijay@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Winson I.G., Robinson D.E., Allen P.E. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Surg Br. 2005;87(3):343–347. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b3.15756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaishya R., Vijay V., Agarwal A.K. Arthroscopic assisted ankle arthrodesis: a surgery simplified. Apollo Med. 2015;12(4):280–282. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien T.S., Hart T.S., Shereff M.J., Stone J., Johnson J. Open versus arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: a comparative study. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(6):368–374. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dannawi Z., Nawabi D.H., Patel A., Leong J.J., Moore D.J. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: results reproducible irrespective of pre-operative deformity? Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17(4):294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson J., Peterson L. Evaluation of ankle joint function: the use of a scoring scale. Foot. 1991;1:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roster B., Kreulen C., Giza E. Subtalar joint arthrodesis: open and arthroscopic indications and surgical techniques. Foot Ankle Clin. 2015;20(2):319–334. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang K.L., Li Q.H., Chen G.X., Guo L., Dai G., Yang L. Arthroscopically assisted ankle fusion in a patient with end-stage tuberculosis. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(9):919–922. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charnley J. Compression arthrodesis of the ankle and shoulder. J Bone Jt Surg. 1951;33B(2):180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M.S., Millward D.M. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2009;26(2):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braly W.G., Baker J.K., Tullos H.S. Arthrodesis of the ankle with lateral plating. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:649–653. doi: 10.1177/107110079401501204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowan R., Davey K.J. Ankle arthrodesis using an anterior AO T-plate. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1999;81(1):113–116. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b1.8999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang G.J., Shen W.J., McLaughlin R.E., Stamp W.G. Transfibular compression arthrodesis of the ankle joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;289:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruen G.S., Mears D.C. Arthrodesis of the ankle and subtalar joints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;268:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swärd L., Hughes J.S., Howell C.J., Colton C.L. Posterior internal compression arthrodesis of the ankle. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1992;74(5):752–756. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B5.1527128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corso S.J., Zimmer T.J. Technique and clinical evaluation of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(5):585–590. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zvijac J.E., Lemak L., Schuhoff M.R., Hechtman K.S., Uribe J.W. Analysis of arthroscopically assisted ankle arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):70–75. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.29923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y.-C., Ahn J.H. Arthroscopically assisted ankle fusion. Arthrosc Orthop Sports Med. 2014;1(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coester L.M., Saltzman C.L., Leupold J., Pontarelli W. Long-term results following ankle arthrodesis for post-traumatic arthritis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2001;83-A(2):219–228. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs S., Sandmann C., Skwara A., Chylarecki C. Quality of life 20 years after arthrodesis of the ankle: a study of adjacent joints. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2003;85(7):994–998. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b7.13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann R.A., Rongstad K.M. Arthrodesis of the ankle: a critical analysis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(1):3–9. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dent C.M., Patil M., Fairclough J.A. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1993;75(5):830–832. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gougoulias N.E., Agathangelidis F.G., Parson S.W. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(6):695–706. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]