Abstract

HIV-positive Kenyan men who have sex with men (MSM) are a highly stigmatized group facing barriers to care engagement and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence. Because care providers' views are important in improving outcomes, we sought the perspective of those serving MSM patients on how to optimize ART adherence in a setting where same-sex behavior is criminalized. We conducted 4 focus group discussions with a total of 29 healthcare workers (HCWs) experienced in providing HIV care to MSM. The semistructured, open-ended topic guide used was based on an access-information-motivation-proximal cues model of adherence, with added focus on trust in providers, stigma, and discrimination. Detailed facilitator notes and transcripts were translated into English and reviewed for common themes. The HCW identified adherence challenges of MSM patients that are similar to those of the general population, including HIV-related stigma and lack of disclosure. In addition, HCWs noted challenges specific to MSM, such as lack of access to MSM-friendly health services, economic and social challenges due to stigma, difficult relationships with care providers, and discrimination at the clinic and in the community. HCWs recommended clinic staff sensitivity training, use of trained MSM peer navigators, and stigma reduction in the community as interventions that might improve adherence and health outcomes for MSM. Despite noting MSM-specific barriers, HCWs recommended strategies for improving HIV care for MSM in rights-constrained settings that merit future research attention. Most likely, multilevel interventions incorporating both individual and structural factors will be necessary.

Keywords: : HIV-AIDS, men who have sex with men, antiretroviral therapy, adherence, healthcare providers, Kenya

Introduction

HIV prevalence and incidence are elevated among African men who have sex with men (MSM) relative to men in the general population.1,2 For example, the national HIV-1 prevalence among adult men in Kenya was estimated at 5.6% in 2007;3 while among MSM recruited into research cohorts at the Kenyan coast in the same year, the estimated HIV-1 prevalence was 43% among men who reported sex with men exclusively and 12% among men who reported sex with both men and women.4

In Kenya, as in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, male same-sex sexual behavior is criminalized and highly stigmatized by society, including in the health sector.5 Past HIV control efforts in Kenya have focused on prevention of heterosexual and mother-to-child transmission, leading to a reduction in overall HIV prevalence among adults aged 15–64 years, from 7.2% in 2007 to 5.6% in 2012.6 However, programming and policy to address the HIV epidemic among Kenyan MSM have lagged behind, in large part, due to stigma.7

Access to good quality care is a key determinant of effective engagement with health services and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART).8,9 Access to effective HIV care involves not only the availability of easily reachable and well-resourced health facilities but also of health providers with nonjudgmental attitudes who foster effective relationships with their patients. Stigmatizing attitudes by healthcare providers has been shown to affect the desire and motivation of African patients to start and adhere to ART.10–12 Poor provider–patient relationships are of particular concern for ostracized population groups and have been associated with poor access to care and worse clinical outcomes among African MSM.13–15

In recognition of these problems, the World Health Organization has offered guidelines for best practices in providing care to MSM, using a rights-based approach to ensure access to services of the highest possible quality.16 Despite this, evidence-based culturally relevant interventions and approaches to care provision for MSM in rights-constrained settings are still lacking. In this study, we conducted a qualitative assessment among healthcare workers (HCWs) with experience managing HIV in MSM patients in coastal Kenya. Our overall objective was to explore factors affecting ART adherence and engagement with care for this population, with an ultimate goal of developing a tailored intervention to promote optimal ART adherence and improve health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Conceptual framework

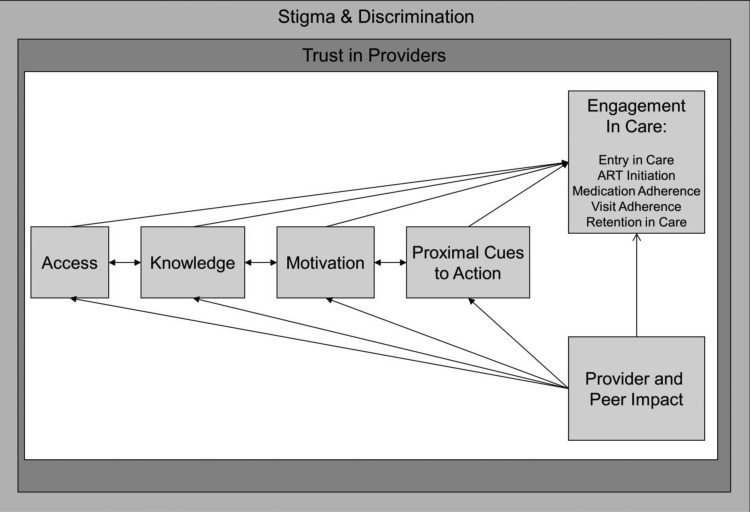

To ensure that we explored adherence determinants comprehensively, we adopted a conceptual framework closely compatible with our prior cross-cultural work and the adherence literature.17–21 This model, depicted in Fig. 1, identifies four general steps that are necessary for affected populations to engage in care and adhere to treatment, and which are applicable to the needs of Kenyan MSM: access, information, motivation, and proximal cues to action. The model emphasizes the overarching context of stigma and discrimination that shapes MSM patients' trust in providers. In turn, this trust exerts a more immediate contextual influence on the patients' ART-related access, information, motivation, and cues to action.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model.

We developed a semistructured, open-ended topic guide with questions exploring HCWs' views about whether the MSM patients they served face difficulties with any of the four steps to adherence depicted in Fig. 1:

1. Access: Factors affecting MSM patients' access to healthcare and medication, including provider knowledge, provider attitudes, and structural aspects of care delivery.

2. Knowledge: General MSM patient knowledge about ART, side effects, and the importance of adherence.

3. Motivation: Psychosocial factors among MSM patients such as beliefs that medication will work, self-efficacy to adhere despite challenges, support from family and social networks, and the impact of substance abuse and mental health.

4. Proximal cues to action: Psychological, social, or electronic reminders for timely pill-taking such as the use of mobile phone alarms.

Providers were also asked to comment on the adequacy of their training to address the challenges of caring for MSM patients, their thoughts on what interventions might be helpful to improve adherence and care engagement for this group, and any other concepts that they felt were relevant to the topic addressed.

Study setting

The study was conducted between June 2013 and March 2014 in Mombasa and Kilifi, two counties of coastal Kenya that are home to a large population of MSM.22 Discussions were held at the Malindi sub-County Hospital Comprehensive Care Clinic, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Kilifi HIV Clinic, the KEMRI Mtwapa HIV Clinic, and the Ganjoni Municipal Clinic in Mombasa Island. While the Malindi and Mombasa sites are large public clinics serving HIV-positive members of the general population in coastal Kenya, the two KEMRI HIV clinics target key populations, including MSM and male and female sex workers.

Recruitment and sampling

KEMRI, with the support of the local government and the National AIDS and STI Control Program (NASCOP), has conducted sensitivity training for HCWs attending to MSM patients (www.marps-africa.org). Prior evaluation of the MSM sensitivity training has shown improvements in HCWs' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to the care of MSM patients.23 Through this network of trained HCWs and input from local community MSM leaders, we identified HCWs with experience caring for HIV-positive MSM patients and invited them to participate in a focus group discussion (FGD) convened at one of four central health facilities. County health chiefs and hospital administrators were consulted beforehand to provide formal permission for staff attendance.

Study population

Twenty-nine of 32 HCWs invited for participation in the study were enrolled in four FGDs. The three HCWs who were not enrolled were unable to attend and sent their regrets. Each FGD included from six to eight HCWs. Mean age was 39 years (interquartile range, 28–59), and 52% were female. Most participants reported five or more years of experience in providing ART care, while only one-third had similar years of experience providing care to MSM patients. Participants included 8 counselors, 7 nurses, 13 clinical officers, and 1 pharmacist. Table 1 provides summary characteristics of the participating HCWs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Healthcare Workers (n = 29)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 15 (52) |

| Male | 14 (48) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–35 | 10 (34) |

| Over 35 | 19 (66) |

| Location | |

| Mombasa | 8 (28) |

| Malindi | 7 (24) |

| Kilifi | 6 (20) |

| Mtwapa | 8 (28) |

| Organization type | |

| Governmenta | 23 (80) |

| Private | 4 (14) |

| Research clinic | 2 (7) |

| Cadre | |

| Clinical staffb | 21 (72) |

| Counselors | 8 (38) |

| Experience working with MSM patients, years | |

| 1–5 | 19 (66) |

| Over 5 | 10 (34) |

| Experience providing ART care, years | |

| 1–5 | 12 (41) |

| Over 5 | 17 (59) |

| Prior MSM training | |

| Yes | 29 (100) |

| No | 0 |

Three of these providers were based at prison health facilities.

Clinical staff included 13 clinicians, 7 nurses, and 1 pharmacist.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Data collection

FGD were facilitated by a trained moderator and followed the semi-structured topic guide described above. Each discussion lasted ∼90 min and was audio-recorded with participant consent. One independent observer and one note-taker were also present to assist in documentation. Discussions began by exploring the challenges of providing HIV care to the general population, before moving on to experiences with MSM patients. Pertinent excerpts from recently conducted in-depth interviews with HIV-positive MSM about the challenges of taking ART were presented as a means of enriching the discussion.24

Data analysis

Two research team members (M.M. and B.K.K.) transcribed the audio recordings verbatim, and translated them from Kiswahili to English when required. These transcripts, together with accompanying facilitator notes, were analyzed with NVivo software, Version 10 (QSR, Cambridge, MA). An initial coding dictionary was developed through discussions of recurring patterns and themes that emerged from detailed notes and reports generated by the study team (moderator, observer, and note-taker) immediately after completion of each FGD. This dictionary was periodically updated by an appointed team member to reflect nuances and emerging constructs identified during the coding process. Each transcript was coded by two research team members (M.M. and B.K.K.), and intercoder reliability was assessed by an independent (noncoding) research team member (D.O.) to ensure rigor and fidelity to the coding dictionary. The final analytic report emerged after a series of discussions with all team members and included representative quotes that illustrated key findings.

Ethics statement

Study procedures were approved by the ethics review boards at KEMRI and the University of Washington. All participants provided written, informed consent. Participants received 350 Kenyan shillings (∼$3.44 USD) for transportation.

Results

HCWs discussed barriers to effective HIV care that were similar to those of the general population, as well as barriers that they felt were specific to HIV-positive MSM. While many of the barriers discussed fit into the conceptual framework proposed and related to access, knowledge, motivation, or proximal cues to action, other barriers, such as anticipatory stigma, related to social and other behavioral skills that HCWs felt were lacking in their MSM patients were also identified. Specific examples of these identified barriers are given below, followed by the strategies for change suggested by participating HCWs. A summary of the themes identified is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary Themes Identified from the Focus Group Discussions with Health Providers

| Major themes | Subthemes | Representative quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to ART for all patients, regardless of sexual orientation | |||

| 1 | Information and AIDS literacy | Lack of knowledge on HIV prognosis, ART, and ART adherence | “When you tell somebody that they have a low CD4 and they have to take medication, they do not understand, because it does not align with what they are saying out there…” (Male clinician, age 28 years) |

| Belief in traditional medicine | “… There are those who have gone for faith healing, others are using herbal medicines…” (Female clinician, age 47 years) | ||

| 2 | HIV stigma | Delayed health seeking | “They really have a lot of stigma, and I think they fear to come out” (Female clinician, age 53 years) |

| Irregular clinic attendance | “You want to go the hospital but you do not want to say where you are going, so you end up missing your visit” (Female clinician, age 45 years) | ||

| Lack of disclosure and psychosocial support | “If there is no disclosure you cannot adhere… You may take the drugs late, or even forget, because you fear your partner might see” (Female clinician, age 45 years) | ||

| 3 | Economic challenges | Inability to afford transport, nonsubsidized medical expenses | “Sometimes they have money to come to the clinic, sometimes they do not have and they miss their appointments” (Male clinician, age 28 years) |

| Lack of adequate nutrition | “In terms of nutrition, sometimes they get supplemental food, but when the programme stops, they come to you and say ‘how can I take this medicine, and I have not even been able to get breakfast, and even lunch?’” (Female counselor, age 43 years) | ||

| 4 | Mental health and substance abuse | Overcoming severe anxiety, guilt, and depression | “I think it is because of desperation, some of them do not have money, they do not have anything so they resort to taking drugs, which helps them feel good about themselves. The drugs themselves: when they overdrink they forget to take their medication, they forget to come to the clinic, they do not keep the time, and so will not be doing as well as per the treatment” (Male clinician, age 28 years) |

| Forgetfulness | |||

| Barriers to ART adherence considered specific to MSM HIV patients | |||

| 1 | Biased clinical environments | Lack of MSM friendly services | “Many had complaints about the staff and how they treated them and this is what had made them default” (Male clinician, age 59 years) |

| Provider inaptitude | “Another issue is that they are not certain; they do not know who is a good person for them, who will understand them” (Male clinician, age 59 years) | ||

| Secondary stigma | “… we were told to be careful because we were going to be beaten for supporting this group” (Female clinician, age 47 years) | ||

| Lack of structural support | “…there is that mentality, especially from the administration, that these people, it's like they are sinners, they are evil, they have done all the evils they should not be getting services from here…” (Male clinician, age 35 years) | ||

| 2 | Prejudiced patient–provider relationships | MSM-related stigma | “… Initially I was very against them, because I wanted them to change and be the right way, you know?” (Male clinician, age 37 years) |

| Anticipatory stigma | “We see sometimes almost 200 patients, and we are so busy… you know they do not have labels on their foreheads… and if I tell you that you are being out of line, it is not because I have phobia… Do not start using words like homophobia with me, there is no place that you will go to that does not have rules, you know?” (Female clinician, age 47 years) | ||

| 3 | Impeded access to social and financial capital | Economic challenges secondary to social ostracism | “…For those who openly say that they are MSM, you find that they have many challenges. For one, they cannot move out during the day because… some have weaves, have plaited their hair, have nail polish… you know the way they present themselves, they cannot walk freely daytime… you find that when they are out doing their work, they are arrested, they are harassed, so on and off they are in prison…” (Female counselor, age 39 years) |

| Unsustainable expectations of support from health workers and facilities | “They also say that taking ARV's on an empty stomach is hectic, so they would rather not take them. And they tell you that if you give me food, I will eat and I will take them, but if you don't, then it is difficult for me to take them” (Female counselor, age 39 years) | ||

| Interventions to improve care | |||

| 1 | HCW sensitization | HCW training | “…through training you come to feel, you come to understand them, you come to understand their suffering… at least you know, what are the things they are getting out there, what are the things that are making them not swallow these drugs, what are that things that are making them not to attend to the clinic, what are the things that are making him, sometimes come in annoyed, so you feel that you want to know more” (Male clinician, age 35 years) |

| Structural support | “The administration is also important … our bosses should be called, and be informed, be educated…” (Male counselor, age 35 years) | ||

| 2 | Peer navigators | Peer mentorship | “To support MSM adherence, I think you need to use an MSM doing pretty well to support the others” (Female counselor, age 36 years) |

| Support to HCW | “We have an MSM peer working with us, sometimes they call him and he calls us” (Female clinician, age 53 years) | ||

ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; HCW, healthcare worker; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Barriers to ART adherence for all patients, regardless of sexual orientation

Information and AIDS literacy

HCWs felt that a common barrier to adherence in all patient groups was mistrust of ART due to ignorance and misinformation, leading to rejection of conventional care services in favor of faith-healing and herbal medications.

“…In the clinic where I work they still believe that HIV is from bewitchment, so they opt to go to the witch doctors in the village, turning up for treatment in the critical phase when you cannot do anything for them … Some think that the medications are poisons which will harm you if you take them early, so you need to delay taking them. So when you tell somebody that they have a low CD4 and they have to take medication, they do not understand, because it does not align with what they are saying out there.” (Male clinician, age 28 years).

“For me, from where I sit, the patients I see most are semi-illiterate… So I think the literacy level is affecting the awareness of HIV… we need to change the mode of communicating to them, in simple language that they can understand.” (Male clinician, age 28 years).

HIV stigma

Fear of rejection and discrimination based on HIV status was also identified as a major hindrance to effective care-seeking for many patients, regardless of sexual orientation. Presenting late for care and a preference for clinics located away from home were attributed to a wish to hide one's HIV status.

“It is the fear of being seen by other people coming here… you might find someone coming for adherence counselling or a clinic visit, but they leave because there are people who might see them and then talk about them in the community.” (Female counselor, age 40 years).

This fear was thought to lead frequently to nondisclosure, particularly to partners, family, and other social networks, which otherwise could offer much-needed psychosocial support.

“I think that when it comes to disclosure, most of our patients do not disclose about their status to either their partners or even family members who are the key people who can be of support to them. I think that is one of the major challenges why patients who have not disclosed their status fail to come to medications or are lost to follow up … If I am seen taking medications, how will people take me?” (Male counselor, age 28 years).

Economic challenges

Socioeconomic status and food security were also identified as factors critical for treatment success for all patients.

“You can find someone who is willing and motivated to take the medicines properly, but when he gets sick with a different illness that he needs to buy medicines for and can't afford, he gets demoralized to take the ARV's you are giving him.” (Female counselor, age 43 years).

Mental health

Health providers felt that adherence and clinical prognosis were poorer in those with substance abuse and mental illness regardless of sexual orientation.

“For those who might have gone through… let's say treatment failure,… at times they also reach that level of apathy and just refuse to take their medications, and just wait for their deaths. We also see this in the general population, sometimes people just get tired, they get into depression, and decide not to take their medications…” (Male clinician, age 38 years).

Barriers to ART adherence considered specific to MSM HIV patients

HCWs identified barriers specific to MSM, which they broadly attributed to heterosexist bias, with implications on institutional practice and clinical interactions, and the social and economic well-being of their MSM patients.

Biased clinical environments

HCWs identified clinical barriers at both provider and structural levels that made engagement with their MSM patients difficult, including prejudice and social norms that led to discriminatory practices. HCWs' own confidence in their capability to provide high-quality empathetic care was identified as important for adherence. Most stated that before sensitivity training, they had felt ill prepared to address the unique health concerns of their MSM patients.

“Health worker training does not address the issues of MSM in any way… Health care workers who have not gone through the sessions on MSM are ill prepared to handle MSM.” (Male clinician, age 38 years).

“When we started offering MSM services here, from the counselling point of view, […] it was not something that was really flowing, because of the personal values and other things, traditional beliefs…” (Female counselor, age 39 years).

HCWs who had attended sensitization sessions reported facing discrimination by their nonsensitized colleagues once back at their duty stations. Such experiences and fear of secondary stigma led to reluctance to associate with MSM patients, inhibiting quality care.

“Some of them are calling us lesbians, simply for attending to MSM, but I am not a lesbian, so I don't care…” (Female counselor, age 50 years).

In addition, the lack of structural support from administrators and policy makers was seen as an impediment to improving access.

“The administration itself does not want to accept the issue of homosexuality… Being well known that it [the health facility] is a government institution, it's a challenge of itself so sometimes have to work on my own in secret… Our bosses should be called, and be informed, be educated… because if I will get educated but my boss is like that, then we will be doing zero work.” (Male counselor, age 35 years).

Prejudiced patient–provider relationships

While HCWs felt that MSM were able to use reminders and other cues for adherence appropriately, they thought that some MSM lacked the skills needed to interface with the healthcare system. In our discussions, it became apparent that the level of interaction between HCWs with MSM patients outside of health services was minimal, resulting in MSM patients being seen as oddities or outsiders.

“I could not know them; it was very difficult for me to know them.” (Male clinician, age 36 years).

Some HCWs appeared to fear conflict with MSM patients, either from reluctance to be perceived as homoprejudiced or fear of calling attention to themselves while interacting with these patients.

“We have the few [MSM patients] who draw negative attention to themselves… they talk, sometimes insulting the next patient, then that will be one who will get into trouble with the staff here. And not because they are MSM but because they are disturbing the other patients, and here we have to look out for all the patients, whether they are MSM or not MSM. So if I tell you that you are going out of line, do not start using words like homophobia with me, there is no place that you will go to that does not have rules, you know?” (Female clinician, age 47 years).

MSM-related stigma was thought to be compounded by HIV stigma, with consequent complications for effective care-seeking.

“For them, even before they know their status, being an MSM is already stigmatizing. When they come for treatment, when they come to the hospital and realize that they are positive, it becomes worse. It is also affecting them, in that they get service late because of that stigma. So you find that most of them come with OI's [opportunistic infections], which is when they seek treatment. That is when you get to know that this person is HIV positive and also MSM…” (Female counselor, age 33 years).

HCWs felt that this dual stigma experienced by MSM HIV patients could have devastating clinical consequences, such that avoidance of HIV care and delayed treatment due to anticipatory stigma can exacerbate MSM patients' clinical problems. HCWs further ascribed some of the difficult interactions they had with MSM patients due to anticipatory stigma, and commented on how this stigma could translate into difficulties navigating HIV care:

“When somebody has self-stigma, they will come to the CCC [comprehensive care center], and anybody who looks in their direction, they think they are looking at them, the seat arrangement is in a way that it is bothering them…” (Female clinician, age 47 years).

Such strained relationships exemplify how MSM patients' perceptions about the healthcare environment can impede respectful care and preclude open, honest engagement. Despite this, participating HCWs recognized a responsibility in educating the larger community to mitigate stigma and its effects, particularly given their respected position in society.

“I think if I can put myself in the shoes of a patient, I want something that will give me hope… The status of HCW in society is different… ‘When I look at you, I know that you are a doctor, so whatever you tell me, I will take it more seriously than the other person out there who has less information.’” (Male clinician, age 38 years).

Impeded access to social and financial capital

HCWs felt that many MSM also faced economic challenges that were often seen as a consequence of their social ostracization, which resulted in limited social support, an interrupted education, and reduced earning power. MSM patients were portrayed as requesting monetary help or nutritional supplements frequently, and HCWs felt challenged by the lack of services or funding to support patients with such problems:

“They [MSM patients] have challenges, and will present many things that are not maybe in line with your work. For instance, they keep talking about food, whereby we [HCWs] do not provide food…” (Female counselor, age 33 years).

“I think the biggest challenge we have is once you identify these problems, do you have the proper referral mechanisms that can deal with the problems, because there are some [MSM patients] who will tell you that my house has been locked, and everything including the drugs are in that house, so in that case, you identify the immediate need is monetary …” (Male clinician, age 35 years).

Interventions to improve care

Providers were encouraged to identify and discuss potential strategies for improving ART adherence and care engagement that might be integrated into an intervention tailored for HIV-positive MSM. In addition, we presented health providers with possible intervention components that had been found beneficial for similar use in various settings. These focused primarily on client-centered care provision, behavioral modification, and the use of trained peers.25–27 Ultimately, the strategies proposed by HCWs centered on two interconnected themes: HCW capacity building through training, sensitization, and other structural modifications, and empowerment of MSM patients through the use of trained peer navigators.

HCW sensitization

Providers' ability to provide high-quality empathetic care was identified as crucial for the adherence of their MSM patients to ART. Participating HCWs suggested that MSM-specific health issues be incorporated into preservice training, which would also serve to normalize care provision and prevent secondary stigma for providers. Inclusion of administrators and managers was suggested, as structural support from senior staff was deemed essential.

“I suggest that we train more health workers …because not all of them have been sensitized. Because the buck stops with the health care worker: If they [MSM] think that you are approachable and that the clinic is friendly, then they will be back…” (Male clinician, age 28 years).

“If possible, perhaps the issues of HIV and MSM should be put maybe in the core curriculum during the basic training at the college, maybe that will bring insight…” (Male clinician, age 38 years).

Use of peer navigators

Participating HCWs were asked their views on whether trained MSM peer navigators with experience taking ART could be helpful. This idea was well received, as HCWs were aware of other successful peer mentor programs, particularly the “mother mentor” program for prevention of mother to child transmission, in which HIV-positive mothers provide mentorship to pregnant women newly diagnosed with HIV infection, assisted by health providers in antenatal clinics. This positive example appeared to instill confidence in the feasibility and acceptability of advancing similar programs for MSM patients.

“The benefits are they [MSM] sit together as peers, they understand themselves better. They have the same characteristics and are in the same group, so they will benefit more.” (Female clinician, age 43 years).

Even so, when asked to list characteristics preferred in trained peers, HCWs continued to demonstrate homoprejudiced attitudes, exemplified by their preference for those esteemed by the general community, “despite being MSM.” Effeminate MSM, those with drug and alcohol problems, men in obviously poor health, and those involved in sex work were not considered appropriate.

“If I were asked to choose this peer, then I would get one who has organized himself, one who respects himself, who is a role model even in the wider community, despite being an MSM, he has kept himself well, it is not easy to know. Not someone who is meant to be the peer in his locale supporting others, but when he is going to visit others, he is dressed in a miniskirt and boots! Will he get anywhere? He won't be listened to by anyone.” (Female counselor, age 36 years).

HCWs welcomed the idea of help from MSM peers, citing the heavy clinic workloads and time constraints typical of most public health facilities. They proposed that peers help provide psychosocial support and health information, and remind patients of medication-taking and clinic visits. HCWs, however, emphasized the need for patients receiving peer support to maintain regular contact with HCWs at clinics.

“We have seen peer educators do that, come with cards, collect medicines for their people and I always tell them that next time, we will not be able to give you medicine because we want to see how this patient is doing, we do not know the condition of the person you are taking medicine for… we do TB screening every visit, this person could have gotten TB out there and you are just collecting medicine for them. So there is a reason why we want them to be coming to the CCC.” (Female clinician, age 47 years).

Enthusiasm for using MSM peer navigators to provide adherence support was tempered by concerns that patients ultimately need to become self-sufficient and take medications independently after a limited period of support, rather than become dependent upon peer navigators for continued assistance.

“The issue is that if you encourage him [the MSM patient] to think that you will do everything for him, he will say ‘you tell me what to do.’ But sometimes it is important for them to find out what they can do for themselves, so if you let him feel that he has some responsibility in this […], instead of him depending on you for everything.” (Male clinician, age 59 years).

Community reactions to peer MSM support programs were also of concern due to perceptions among community members that MSM receive additional services that are not available to others. Some HCWs felt that such interventions could consequently jeopardize safety for the MSM community, while others saw this as an opportunity for sensitization and dialogue.

“Special attention given to MSM upsets the community. Because if we [HCWs] bring in all this, well we are trying to do a good thing for them, encouraging them to access health care services and so on, but I think there might be some… the community might be negative about it, because they feel MSM are given special attention, and this is encouraging the practice.” (Male counselor, age 28 years).

“Other people also need to understand MSM […] because the other people are their brothers and sisters, and parents who need to be able to live with them and support them, and the first step is in understanding them…” (Female counselor, age 47 years).

Discussion

Findings from this qualitative study of HCWs in coastal Kenya provided support to the ART adherence model for use with Kenyan MSM.18,21,28 In this analysis, access to services and the need to prioritize health for MSM were the most salient determinants of ART adherence described by HCWs. Specific barriers to access for MSM patients included the lack of HCWs who were trained in male sexual health and sensitized to provide respectful patient-centered care. In addition, HCWs felt that the homoprejudiced social–political environment in Kenya negatively influenced MSM's health-seeking behavior and led to late presentation for care, as reported elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa.14,29,30

Our findings suggest that, in addition to structural factors such as the availability of services, HCWs are themselves a critical component of access to good clinical care and positive health outcomes. Provider attitudes have been implicated in poor engagement in care in the general population,10–12 and HIV-related stigma was reported as an important issue that MSM HIV patients face. However, HCWs participating in this study, all of whom had received sensitivity training in MSM health provision, felt that MSM living with HIV infection faced specific challenges in accessing care. Specifically, HCWs identified economic and social challenges due to stigma, difficult relationships with care providers, and discrimination at the clinic and in the community, as major deterrents to optimal ART adherence.

In the conceptual framework used, we proposed that the effects of stigma faced by MSM patients would be mediated by trust in their providers. However, we found that HCWs are themselves inhibited by secondary stigma resulting from being seen as MSM-friendly.31 In addition, HCWs also reported structural barriers such as busy workloads and time constraints, inadequate training to address patient problems, and poor administrative support for work with MSM patients. The challenges of inadequate training, personal and social prejudices, and concern about secondary stigma have been reported by other HCWs working in similar environments.31–33 Encouragingly, HCW attitudes toward MSM were thought to improve after sensitivity training,23,34 with suggestions to bolster sensitization by increased hands-on interaction with MSM patients and inclusion of MSM-specific health topics in both preservice curricula and continuing medical education programs. Participating HCWs also proposed improved stigma reduction in the community and strongly endorsed the use of trained MSM peer navigators to improve care engagement and foster trust in their MSM patients.

The motivation of MSM patients to engage in care and adhere to ART was found to be complicated by societal stigma, including what may well be anticipatory stigma related to clinic visits. Of interest, HCWs did not think that MSM faced barriers related to substance abuse or mental health that differed from those seen in the general population. HCWs may need further training on this issue, as evidence suggests that MSM are particularly vulnerable to these problems. In formative work exploring the correlates of depression among self-identified MSM in coastal Kenya, Secor et al. found not only that levels of depression in participants were considerably higher than those reported nationally but also that sexual stigma was a risk factor for depression in this population.35 Similar challenges have been reported among African MSM living elsewhere,36,37 and have been accompanied by calls for increased HCW training to address these needs.

Our main objective in conducting this study was to identify interventions that HCWs thought feasible, acceptable, and likely to improve engagement and adherence among MSM in HIV care. The idea to use peer navigators to improve ART adherence in the target population was well received and compared by participants to similar successful initiatives among less stigmatized populations such as HIV-positive pregnant women. However, HCWs had concerns about finding MSM peers with the requisite skills and social qualities, integrating MSM peers into the provider team, and community misperceptions about a program benefiting MSM patients only. These concerns make it clear that even among sensitized HCWs, implicit bias against MSM can perpetuate a professional climate reinforcing negative attitudes. This situation is not unique to African settings,38,39 but may be exacerbated by the lack of countervailing cultural forces in this region.

Due to overall positive feedback on the idea of peer navigators by these HCWs and MSM patients living in these communities, this idea has been developed into an intervention that is currently being tested in the KEMRI Mtwapa clinic.40 Provider training in patient-centered care and motivational interviewing, as well as mental health screening, are also intervention components.40 Partnering of peer navigators with health teams may help mobilize social capital for otherwise marginalized patients and promote a shared ownership in a health promotion model that includes MSM in the care delivery team. However, as the results presented in this study demonstrate, such interventions must be accompanied by HCW training, ongoing support, and stigma reduction such that the challenges facing both MSM patients and their providers are addressed.

This study was limited by a relatively small sample size (29 providers in 4 focus groups), in addition to the use of HCWs who had already completed sensitivity training and whose views may not be representative of HCWs in the region at the coast. However, as the roll out of MSM sensitivity training continues through online forums such as www.marps-africa.org and other training initiatives, disparities between those sensitized and those not should be minimized by changing social norms.

Hostile social and political environments hinder the ability of HCWs to provide optimal and respectful care to MSM. Provider training coupled with administrative and policy support are key to moderating the homoprejudice ingrained in health services, especially in African settings. Integrating provider training with MSM patient empowerment initiatives such as peer navigator programs and support for MSM advocacy groups should also foster increased trust and mutually beneficial health programs.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by NIH grant R34MH099946 (S.M.G., principal investigator). J.M.S. was supported by NIH grant K24 MH093243. D.O. was supported by R24 HD07796. We thank the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI027757) supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, and NIDDK, for supporting the high-risk cohort studies in Kilifi, and staff in the HIV/STI project at the Kenya Medical Research Institute in Kilifi for their commitment to serving MSM. We are also grateful for support and guidance provided by the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme to carry out research with stigmatized and vulnerable populations.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: A systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2012;380:367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National AIDS and STI Control Programme, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007: Preliminary Report. 2008

- 4.Sanders EJ, Graham SM, Okuku HS, et al. HIV-1 infection in high risk men who have sex with men in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS 2007;21:2513–2520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AD, Tapsoba P, Peshu N, Sanders EJ, Jaffe HW. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2009;374:416–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimanga DO, Ogola S, Umuro M, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HIV infection, trends, and risk factors among persons aged 15–64 years in Kenya: Results from a Nationally Representative Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:S13–S26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinnon LR, Gakii G, Juno JA, et al. High HIV risk in a cohort of male sex workers from Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merten S, Kenter E, McKenzie O, Musheke M, Ntalasha H, Martin-Hilber A. Patient-reported barriers and drivers of adherence to antiretrovirals in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-ethnography. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15(Suppl 1):16–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannheimer SB, Matts J, Telzak E, et al. Quality of life in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy is related to adherence. AIDS Care 2005;17:10–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treves-Kagan S, Steward WT, Ntswane L, et al. Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: A rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health 2016;16:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons A, Moiane L, Demetria E, Veldkamp P, Prasad R. Patient perspectives on reasons for failure to initiate antiretroviral treatment in Mozambique: A call for compassionate counseling. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:197–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Loggerenberg F, Gray D, Gengiah S, et al. A qualitative study of patient motivation to adhere to combination antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloete A, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Henda N. Stigma and discrimination experiences of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care 2008;20:1105–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fay H, Baral SD, Trapence G, et al. Stigma, health care access, and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS Behav 2011;15:1088–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham SM, Mugo P, Gichuru E, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and clinical outcomes among young adults reporting high-risk sexual behavior, including men who have sex with men, in coastal Kenya. AIDS Behav 2013;17:1255–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines: Prevention and Treatment of HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender People: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach 2011. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starks H, Simoni J, Zhao H, et al. Conceptualizing antiretroviral adherence in Beijing, China. AIDS Care 2008;20:607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Shiu CS, Starks H, et al. “You must take the medications for you and for me”: Family caregivers promoting HIV medication adherence in China. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:735–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: A review of current literature and ongoing studies. Top HIV Med 2003;11:185–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni JM, Amico KR, Smith L, Nelson K. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: Translating research findings to the real world clinic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2010;7:44–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simoni JM, Amico KR, Pearson CR, Malow R. Strategies for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A review of the literature. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2008;10:515–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geibel S, van der Elst EM, King'ola N, et al. ‘Are you on the market?’: A capture-recapture enumeration of men who sell sex to men in and around Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS 2007;21:1349–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Elst EM, Smith AD, Gichuru E, et al. Men who have sex with men sensitivity training reduces homoprejudice and increases knowledge among Kenyan healthcare providers in coastal Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16(Suppl 3):18748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Micheni M, Secor A, van der Elst E, et al. Facilitators and challenges to ART adherence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Coastal Kenya. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014;30(Suppl 1):A136 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss L, French T, Finkelstein R, Waters M, Mukherjee R, Agins B. HIV-related knowledge and adherence to HAART. AIDS Care 2003;15:673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leeman J, Chang YK, Lee EJ, Voils CI, Crandell J, Sandelowski M. Implementation of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A realist synthesis of evidence. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:1915–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher JD, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Harman JJ. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of antiretroviral adherence and its applications. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2008;5:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baral S, Trapence G, Motimedi F, et al. HIV prevalence, risks for HIV infection, and human rights among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. PLoS One 2009;4:e4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Risher K, Adams D, Sithole B, et al. Sexual stigma and discrimination as barriers to seeking appropriate healthcare among men who have sex with men in Swaziland. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Elst EM, Gichuru E, Omar A, et al. Experiences of Kenyan healthcare workers providing services to men who have sex with men: Qualitative findings from a sensitivity training programme. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16(Suppl 3):18741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dijkstra M, van der Elst EM, Micheni M, et al. Emerging themes for sensitivity training modules of African healthcare workers attending to men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Int Health 2015;7:151–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane T, Mogale T, Struthers H, McIntyre J, Kegeles SM. “They see you as a different thing”: The experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare workers in South African township communities. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:430–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Elst EM, Kombo B, Evans Gichuru AO, et al. The green shoots of a novel training programme: Progress and identified key actions to providing services to MSM at Kenyan health facilities. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:20226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Secor AM, Wahome E, Micheni M, et al. Depression, substance abuse and stigma among men who have sex with men in coastal Kenya. AIDS 2015;29:S251–S259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy CE, Baral SD, Fielding-Miller R, et al. “They are human beings, they are Swazi”: Intersecting stigmas and the positive health, dignity and prevention needs of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Swaziland. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16(Suppl 3):18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoloff K, Joska JA, Feast D, et al. A description of common mental disorders in men who have sex with men (MSM) referred for assessment and intervention at an MSM clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav 2013;17:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fallin-Bennett K. Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: Cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum. Acad Med 2015;90:549–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorsen C. An integrative review of nurse attitudes towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. Can J Nurs Res 2012;44:18–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham SM, Micheni M, Kombo B, et al. Development and pilot testing of an intervention to promote care engagement and adherence among HIV-positive Kenyan MSM. AIDS 2015;29:S241–S249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]