Abstract

Background:

Leptin and its receptor are present in spermatozoa; however, the role of leptin in sperm function is still controversial. Our present study aimed at demonstrating the effect of cryopreservation on sperm DNA fragmentation (DNAf) and investigating the possible effects of sperm capacitation techniques and leptin in vitro incubation on frozen-thawed sperm DNAf and oxidative stress.

Methods:

Samples of 45 normospermic men attending for infertility investigation at Vida Centro de Fertilidade, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, were frozen and thawed with or without capacitation and leptin incubation prior to freezing. Sperm DNA fragmentation was evaluated by Sperm Chromatin Dispersion Assay before and after cryopreservation and oxidative stress parameters were measured by spectrophotometry with and without leptin incubation. Statistical analysis was performed using paired t test to compare DNAf between groups before and after freeze-thaw cycle, to compare groups before and after capacitation and leptin incubation and oxidative measurements before and after leptin incubation. Statistical significance was considered when p≤0.05.

Results:

Our results revealed a significant post-thaw rise in sperm DNAf compared with fresh samples (p=0.0003). Sperm DNAf was significantly reduced when sperm capacitation was performed before freezing, when compared to those frozen with no previous capacitation (p=0.01). The addition of leptin to capacitated sperm before freezing reduced DNAf (p<0.0001) and enhanced superoxide dismutase (p=0.001) and glutathione peroxidase (p=0.02) antioxidant enzymes activity.

Conclusion:

The addition of leptin to capacitated sperm can improve sperm DNA quality following cryopreservation, possibly by inducing the activity of certain antioxidant enzymes.

Keywords: DNA fragmentation, Freeze-thaw cycle, Leptin, Oxidative stress, Sperm

Introduction

Cryopreservation of gametes and embryos has a wide importance among assisted reproductive techniques. Taken into account the spermatozoa, cryopreservation has several applications, such as seminal storage prior to prostate and vasectomy surgeries, before chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments, prior to fertility treatments and for donor sperm banking (1). However, sperm freezing and thawing processes lead to intracellular ice crystals formation which causes organelles and cell membrane rupture (1), modifies the structure and integrity of plasma membranes (2), and alters mitochondrial membrane potential and release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (3). In addition, cryopreservation has been shown to diminish the antioxidant activity of the spermatozoa making them more susceptible to ROS damage (4).

Oxidative stress occurs when excessive ROS generation overcomes the ROS scavenging ability of spermatozoa. Spermatozoa and seminal plasma contain antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), although its lack of cytoplasm leads to a decrease of antioxidant defense. Moreover, spermatozoa are particularly more susceptible to lipid peroxidation because of the high proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acid in their membranes (5, 6). Deleterious effects of oxidative stress can result in several structural alterations of spermatozoa, such as protein fragmentation, lipid peroxidation and DNA fragmentation (DNAf) (7). Increase in DNAf is related to reduced implantation and pregnancy rates and increased recurrent pregnancy loss (8, 9). In order to minimize deleterious effects of cryopreservation, some studies have focused on testing antioxidants action on sperm cryopreservation (10, 11). Zhang et al. observed a protective effect of L-carnitine, leading to a significant improvement in post-thawed sperm parameters, including DNAf levels (10). Mata-Campuzano et al. also observed a reduction of lipid peroxidation and DNAf following antioxidant supplementation of spermatozoa during cryopreservation (11).

Leptin, a peptide hormone mainly secreted by adipose tissue, is widely known by its functions related to obesity, appetite and food intake inhibition and energy expenditure. However, it has been shown to have roles in diverse physiologic systems, including reproductive system (12). Although presence of leptin and its receptor has been demonstrated in spermatozoa (13–15), its role on spermatogenesis and sperm still needs to be clarified. Literature has some controversial results concerning sperm parameters after leptin in vitro incubation (13, 16). Lampiao and Du Plessis (2008) found an increase in total and progressive motility, in acrosome reaction and nitric oxide (NO) production after leptin incubation. In contrast, the study by Li et al. (2008) demonstrated no significant effects of leptin incubation on motility, and percentage of capacitated and acrosome reacted sperm after leptin incubation (13). Additionally, studies have suggested that leptin has a role in oxidative stress (17, 18) which is still controversial. Zheng et al. demonstrated that leptin increased sod activity in cardiomyocytes (19), while Yamagishi et al. observed a leptin-induced lipid oxidation in endothelial cells (20). However, leptin role in oxidative stress and sperm cryopreservation remains unclear.

Our present study aimed at demonstrating the effect of cryopreservation on sperm DNAf and investigating the possible effects of sperm capacitation and leptin incubation on frozen-thawed sperm DNAf and oxidative stress.

Methods

Patients and semen analysis:

Semen samples were collected from 45 normospermic patients aged 28–45 years (35.3±4.8) from November 2014 to June 2015, by masturbation after 2 to 3 days of ejaculatory abstinence attending for male infertility investigation at Vida Centro de Fertilidade da Rede D’Or in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Samples were collected into sterile vials and were left to be liquefied at 37°C for 30 min. Semen samples were analyzed according to WHO criteria (2010) for concentration (≥15×106 sperm/ml) and motility (≥32% progressive motility or 40% total motility) and according to Kruger’s criteria for morphology (≥4% normal morphology). The evaluation of concentration, motility and morphology were performed using Neubauer chamber, Makler chamber and Spermac staining (SermacstainTM Sperm Morphology kit, FertiPro; Belgium), respectively. The criteria for exclusion from the study were urogenital infection, varicocele, hydrocele, use of drugs and medications and other diseases such as diabetes mellitus, obesity and malnutrition. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Pedro Ernesto (CEP/HUPE 432.202) and all patients provided written informed consent.

Experimental design:

In order to achieve the goal of this study, an experiment was initially done comparing fresh raw (FR) and frozen-thawed raw (F-T) semen samples from 15 patients to evaluate the effect of cryopreservation on DNAf. Based on the results observed, a second experiment was done using frozen-thawed raw (F-T) and capacitated (F-Tcap) semen samples from other 15 patients. In order to evaluate if leptin had some additional effect on the DNAf and oxidative stress of capacitated samples, a new experiment was performed using other 15 semen samples of previously capacitated frozen-thawed treated (F-TcapL) or not treated (F-Tcap) ones with leptin.

Sperm freeze-thaw cycle:

Samples were placed with 1:2 cryoprotectants (SpermFreeze; Vitrolife; Sweden) on cryovials and frozen in vapor liquid nitrogen for 30 min, followed by liquid nitrogen immersion. Samples remained in liquid nitrogen for two months when analysis was performed. For sperm thawing, cryovials were taken from liquid nitrogen and immediately immersed in water bath at 37°C for 5 min.

Sperm capacitation:

For sperm capacitation, samples were centrifuged at 180 g for 20 min using 2-layered density gradient centrifugation (DGC) solutions of 45% and 90% (SpermGrad; Vitrolife; Sweden). The supernatant was then removed and the pellet was washed in 1.5 ml human tubal fluid medium (HTF HEPES; Irvine Scientific; United States) supplemented with 10% SPS (SPS; Irvine Scientific; United States) at 180 g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and 1 ml of medium was gently layered on the pellet. Then, the tube was inclined at an angle of 45 degrees and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. The upper interface was aspirated to obtain the motile fraction, which was divided in aliquots for leptin incubation.

Leptin incubation:

Capacitated samples were incubated with 10 ng leptin at 37°C and 6% CO2 overnight, before freezing. The leptin dose was used based on previous studies ( 13, 15, 16).

Sperm DNA fragmentation assay:

Sperm DNA integrity was assessed using SCD assay (Halosperm kit). Semen samples were diluted using 1:1 concentration in melt agarose microgel and placed in pretreated slides. Denaturing solution was used to denature nuclear DNA protein. Sperm were lysed and dispersed a large or medium DNA halo in non-fragmented sperm cells and a small or none DNA halo in fragmented sperm cells. At least 300 spermatozoa per sample were examined at 1000x magnification by oil immersion. The cut-off of SCD test is 30% (21). DNAf was performed to compare FR versus F-T; F-T versus F-Tcap; F-Tcap versus F-TcapL.

Oxidative stress

Pro-oxidant mechanisms were evaluated in F-Tcap and F-TcapL.

- Lipid peroxidation was evaluated through measurement of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (22).

- Protein oxidation: This method is based on reaction of 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) with sulfhydryl (SH) group, which was measured at 412 nm using a spectrophotometer (23).

Antioxidant mechanisms were evaluated in F-Tcap and F-TcapL.

- Superoxide dismutase (SOD): In this method, adrenaline undergoes oxidation by anion superoxide action, which is inhibited by SOD activity. This oxidation generates adrenochrome, which is measured at 480 nm with a spectrophotometer (24).

- Catalase: Catalase activity was measured by H2O2 quantification at 240 nm with a spectrophotometer (240 nm) (25).

- Glutathione peroxidase (GPx): GPx activity was determined through decay rate of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) at 340 nm with a spectrophotometer (26).

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism version 6.0 software. Data are represented as mean and standard error. D’Agostino-Pearson was used to test normality of samples distribution. Paired t test was used to compare DNAf between groups before and after freeze-thaw cycle, to compare groups before and after capacitation and leptin incubation and oxidative measurements before and after leptin incubation. Statistical significance was considered when p≤0.05.

Results

Sperm DNAf:

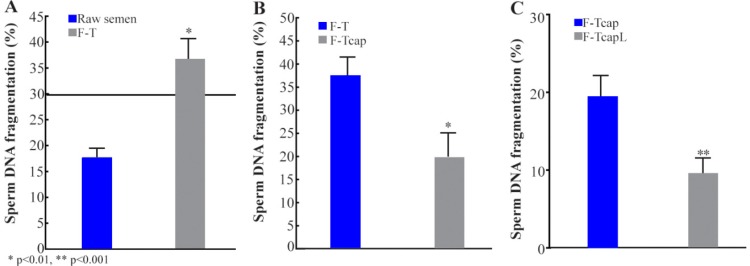

There was a significant increase in sperm DNAf evaluation after freeze-thaw cycle compared to evaluation with the same fresh raw sample (FR=17.6±1.7, F-T=36.2±3.5; p=0.0003; figure 1A). Besides that, this increase occurred in such a way that 53.3% of the samples classified as fragmented (above 30%) after freeze-thaw cycle were found to be non-fragmented (under 30%) in the fresh raw evaluation.

Figure 1.

Percentage of sperm DNAf in fresh raw (FR) and frozen-thawed (F-T) samples. Horizontal line corresponds to cutoff value of the test; n=15 (Figure 1A). Percentage of sperm DNA fragmentation in capacitated (F-TCap) and non-capacitated (F-T) samples before freeze-thaw cycle; n=15 (Figure 1B) and capacitated samples with (F-TCapL) or without (F-TCap) leptin addition before freeze-thaw cycle; n=15 (Figure 1C). Data are represented as mean and standard error

Sperm DNAf was significantly reduced when sperm capacitation was performed before freezing samples, when compared to those frozen with no previous capacitation (raw). (F-T=37.4±4.0, F-Tcap=19.7±5.3; p=0.01; figure 1B). Leptin addition to culture media in capacitated samples, before sperm freezing increased this reduction (F-Tcap=19.3±2.8, F-TcapL=9.5±2.0; p<0.0001; figure 1C) in sperm DNAf.

Pro-oxidant mechanisms:

Leptin addition to capacitated spermatozoa before freezing had no effect on lipid peroxidation (F-Tcap=0.04±0.004, F-TcapL=0.03±0.002; p=0.6; table 1) and protein oxidation (F-Tcap=4.1±0.1, F-TcapL=4.0±0.1; p= 0.2; table 1).

Table 1.

Oxidative damage measured by lipid peroxidation (TBARS), protein oxidation (SH) in capacitated spermatozoa with (F-TCapL) and without (F-TCap) leptin incubation before freezing. Antioxidant activity measured by superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) in capacitated spermatozoa with (F-TCapL) and without (F-TCap) leptin incubation before freezing. Data are represented as mean and standard error; n=15

| Oxidative stress parameter | F-Tcap | F-TcapL | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBARS | 0.04±0.004 | 0.03±0.002 | 0.6 |

| SH | 4.1±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 0.2 |

| SOD | 82.4±6.9 | 100.8±6.2 | 0.001 |

| CAT | 0.02±0.006 | 0.02±0.007 | 0.9 |

| GPx | 88.8±9.8 | 110.7±8.7 | 0.02 |

Antioxidant activity:

There was a significant increase in antioxidant activity of SOD (F-Tcap= 82.4±6.9, F-TcapL=100.8±6.2; p=0.001; table 1) and GPx (88.8±9.8, F-TcapL=110.7±8.7; p=0.02; table 1) when comparing samples with and without leptin addition. However, catalase activity did not differ between groups (F-Tcap=0.02±0.006, F-TcapL=0.02±0.007; p=0.9; table 1).

Discussion

While cryo-induced damage to motility, viability, morphology and fertility capacity is already well documented, the possible DNA damage following sperm freezing is still not confirmed. There appears to be some contradictions concerning whether or not freezing can affect and the extent of the effect on sperm DNAf (4, 27). Some authors reported a significant increase on sperm DNA fragmentation caused by cryopreservation (28, 29), while others suggest there is no harm to DNA integrity (30, 31). This controversy could be explained by several factors: 1) patients selection; in the study of Ozkavukcu et al. (2008) (32), 30% of the patients were smokers and it is known that smoking can alter DNA fragmentation (33); 2) different sperm capacitation techniques before freezing, i.e some studies used raw semen (34), others have isolated sperm by washing (35) or DGC (36); 3) different cryoprotectors were used in the studies; 4) different freezing and thawing protocols; 5) and the use of different techniques to measure sperm DNAf. In our study, a rise in DNAf after sperm freeze-thaw cycle was observed corroborating some previous studies. In order to decrease the variability in the present study, only patients who had no diseases, or used no medication were evaluated. Besides, only normospermic patients according to WHO criteria were included in the study since sperm of infertile men are less resistant to freezing process, showing poor results concerning sperm DNAf, compared to fertile men (4, 37). In this study, raw semen was used for comparison between before freezing and post-thaw DNAf, taking into account that raw semen has a strong antioxidant defense that could protect sperm against oxidative stress during cryopreservation, which in turn, could induce an increase on DNAf (38, 39). The present results can be explained by previous evidence that the process of freezing and thawing can lead to ice crystals formation, provoking plasma membrane disruption, organelle and nuclear membrane, reaching cell DNA (1, 4). The mechanism by which these alterations occur is still unknown. However, a possible reason for this cryo-induced injury could be oxidative stress (40) and the activation of apoptotic cascades (41).

There is still controversy in literature regarding sperm capacitation previous to cryopreservation. Some studies observed better DNAf results by addition of cryoprotectors directly to raw semen, supporting the idea that seminal plasma protects spermatozoa during freeze-thaw cycle, once it is rich in antioxidant enzymes (38, 39). Other researchers support that seminal plasma needs to be removed before freezing, otherwise it can damage sperm motility and vitality after thawing (42, 43). Also, sperm DNAf rates were compared using raw semen for cryopreservation and capacitated samples. Our results showed that sperm preparation previous to cryopreservation had reduced sperm DNAf rates. For sperm capacitation, DGC was performed, followed by sperm wash and pellet swim-up. The likely reason why better results were obtained concerning sperm DNAf of capacitated sperm before freezing can be raised on the hypothesis that the morphologically abnormal sperm are more susceptible to DNA damage during the freezing process than sperm with normal morphology (37). Additionally, head abnormalities and irregular chromatin organization may have altered membrane physical properties and thereby have altered tolerance to cold stress (37). By selecting a subpopulation of spermatozoa through sperm capacitation before freezing, a better quality sample can be obtained after thawing. This procedure allows selecting high quality spermatozoa and the removal of seminal plasma which contains germ cells, not viable, apoptotic and other components that can cause oxidative damage and apoptosis during freeze and thaw procedures (43).

Several studies have been searching for mechanisms to attenuate deleterious effects caused by cryopreservation (10, 11). Some of these attempt for a better sperm preparation before freezing, some for an ideal freeze and thaw protocol and others for better cryoprotector agents. As it is known that oxidative stress is one of the most detrimental factors during cryopreservation, recent studies have been reaching for cryoprotective substances which could minimize this damage (44).

Due to its exclusive structural composition, such as lack of cytoplasm, which leads to decrease of antioxidant defense and a high proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acid in their membranes, making it more susceptible to lipid peroxidation, sperm became more vulnerable to ROS actions (5, 6). Deleterious effects of oxidative stress can result in several structural alterations of spermatozoa, such as protein fragmentation, lipid peroxidation and membrane and DNAf (7). This was the first study to focus on the possible cryoprotective effect of leptin on spermatozoa.

Our results showed that leptin incubation with capacitated spermatozoa before cryopreservation could lead to increase in antioxidant enzymes SOD and GPx, but not catalase. The major cellular enzymatic antioxidants are SOD, catalase and GPx. However, catalase is known to be very effective in high-level oxidative stress and especially important in case of limited glutathione content or reduced GPx activity (45).

A likely mechanism by which leptin can act against oxidative stress is by dissipating the excess energy via thermogenic mechanism and thus, preventing the development of excessive mitochondrial membrane potential (18). In another study, Zheng et al. demonstrated that leptin had anti-apoptotic effects on cardiomyocytes by increasing SOD activity. Leptin signaling could induce SOD2 gene expression and directly activate SOD2 promoter in cardiomyocytes (19). Interestingly, this effect was specific for SOD2 which is mitochondria-located, whereas the cytoplasm-located SOD1 remained unchanged following leptin treatment. In our study, leptin did not change pro-oxidant mechanisms. Leptin does not inhibit ROS formation directly. The reduction of oxidative stress is likely to be due to a rise of antioxidant enzymes activity. Controversially, leptin has shown to induce lipid oxidation in endothelial cells, leading to increased mitochondrial potential and consequent elevation of mitochondrial production of ROS (20). In the present study, leptin also potentiated DNAf reduction in frozen-thawed capacitated samples in relation to sperm capacitation. It can be speculated that the reduction of DNAf after leptin incubation could be explained by increased antioxidant defense, minimizing deleterious effects of oxidative stress during freezing and thawing processes.

In summary, our results show that leptin has a cryoprotective effect and if added to the sample before freezing could reduce deleterious effect of cryopreservation. However, it remains unclear if the addition of this hormone could add value to in vitro fertilization techniques.

Conclusion

Sperm DNAf increased after freeze-thaw cycle compared to evaluation with the same fresh raw sample. Sperm capacitation and leptin addition to culture media showed a cryoprotective effect on spermatozoa by reducing DNAf and increasing antioxidant enzymes activity. However, leptin did not inhibit ROS formation directly. The addition of leptin to capacitated sperm samples before freezing could possibly reduce deleterious effects of cryopreservation.

Acknowledgement

The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and Rio de Janeiro Foundation for Research Support (FAPERJ)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Petyim S, Neungton C, Thanaboonyawat I, Laokirkkiat P, Choavaratana R. Sperm preparation before freezing improves sperm motility and reduces apoptosis in post-freezing-thawing sperm compared with post-thawing sperm preparation. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31(12):1673–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieme H, Oldenhof H, Wolkers WF. Sperm membrane behaviour during cooling and cryopreservation. Reprod Domest Anim. 2015;50 Suppl 3:20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeste M, Estrada E, Rocha LG, Marin H, Rodriguez-Gil JE, Miro J. Cryotolerance of stallion spermatozoa is related to ROS production and mitochondrial membrane potential rather than to the integrity of sperm nucleus. Andrology. 2015;3(2):395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Santo M, Tarozzi N, Nadalini M, Borini A. Human Sperm Cryopreservation: Update on Techniques, Effect on DNA Integrity, and Implications for ART. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:854837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aitken RJ, Baker MA, De Iuliis GN, Nixon B. New insights into sperm physiology and pathology. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010;(198):99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helfenstein F, Losdat S, Moller AP, Blount JD, Richner H. Sperm of colourful males are better protected against oxidative stress. Ecol Lett. 2010;13 (2):213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocuzza M, Sikka SC, Athayde KS, Agarwal A. Clinical relevance of oxidative stress and sperm chromatin damage in male infertility: an evidence based analysis. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33(5):603–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakkas D, Alvarez JG. Sperm DNA fragmentation: mechanisms of origin, impact on reproductive outcome, and analysis. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1027–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Li Y. Whether sperm deoxyribonucleic acid fragmentation has an effect on pregnancy and miscarriage after in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4): 998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Li F, Cao H, Li C, Du C, Yao L, et al. Protective effects of l-carnitine on astheno- and normozoospermic human semen samples during cryopreservation. Zygote. 2016;24(2):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mata-Campuzano M, Alvarez-Rodriguez M, Alvarez M, Tamayo-Canul J, Anel L, de Paz P, et al. Post-thawing quality and incubation resilience of cryopreserved ram spermatozoa are affected by antioxidant supplementation and choice of extender. Theriogenology. 2015;83(4):520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Galiano D, Allen SJ, Elias CF. Role of the adipocyte-derived hormone leptin in reproductive control. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2014;19(3): 141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li HW, Chiu PC, Cheung MP, Yeung WS, O WS. Effect of leptin on motility, capacitation and acrosome reaction of human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 2009;32(6):687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jope T, Lammert A, Kratzsch J, Paasch U, Glander HJ. Leptin and leptin receptor in human seminal plasma and in human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 2003;26(6):335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aquila S, Giordano F, Guido C, Rago V, Carpino A. Nitric oxide involvement in the acrosome reaction triggered by leptin in pig sperm. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampiao F, du Plessis SS. Insulin and leptin enhance human sperm motility, acrosome reaction and nitric oxide production. Asian J Androl. 2008; 10(5):799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haron MN, D’Souza UJ, Jaafar H, Zakaria R, Singh HJ. Exogenous leptin administration decreases sperm count and increases the fraction of abnormal sperm in adult rats. Fertil Steril. 2010; 93(1):322–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solinas G. Leptin signalling coordinates lipid oxidation with thermogenesis and defence against oxidative stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010; 37(10):953–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng J, Fang J, Yin YJ, Wang XC, Ren AJ, Bai J, et al. Leptin protects cardiomyocytes from serum-deprivation-induced apoptosis by increasing anti-oxidant defence. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37(10):955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamagishi SI, Edelstein D, Du XL, Kaneda Y, Guzman M, Brownlee M. Leptin induces mitochondrial superoxide production and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic endothelial cells by increasing fatty acid oxidation via protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27): 25096–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feijo CM, Esteves SC. Diagnostic accuracy of sperm chromatin dispersion test to evaluate sperm deoxyribonucleic acid damage in men with unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Draper HH, Hadley M. Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:421–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bannister JV, Calabrese L. Assays for superoxide dismutase. Methods Biochem Anal. 1987;32:279–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flohe L, Gunzler WA. Assays of glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paoli D, Lombardo F, Lenzi A, Gandini L. Sperm cryopreservation: effects on chromatin structure. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;791:137–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma R, Kattoor AJ, Ghulmiyyah J, Agarwal A. Effect of sperm storage and selection techniques on sperm parameters. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2015;61 (1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meamar M, Zribi N, Cambi M, Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Filimberti E, et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation induced by cryopreservation: new insights and effect of a natural extract from Opuntia ficus-indica. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(2):326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tataru DA, Markova EV, Osadchuk LV, Sheina EV, Svetlakov AV. [The optimal conditions of storage of spermatozoa for analysis of DNA fragmentation]. Klin Lab Diagn. 2015;60(4):52–6. Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vutyavanich T, Piromlertamorn W, Nunta S. Rapid freezing versus slow programmable freezing of human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):1921–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozkavukcu S, Erdemli E, Isik A, Oztuna D, Karahuseyinoglu S. Effects of cryopreservation on sperm parameters and ultrastructural morphology of human spermatozoa. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25 (8):403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basu S, Pant M, Rachana R. Protective effect of Salacia oblonga against tobacco smoke-induced DNA damage and cellular changes in pancreatic β-cells. Pharm Biol. 2016;54(3):458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olaciregui M, Luno V, Gonzalez N, De Blas I, Gil L. Freeze-dried dog sperm: Dynamics of DNA integrity. Cryobiology. 2015;71(2):286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khodayari Naeini Z, Hassani Bafrani H, Nikzad H. Evaluation of ebselen supplementation on cryopreservation medium in human semen. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12(4):249–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghorbani M, Amiri I, Khodadadi I, Fattahi A, Atabakhsh M, Tavilani H. Influence of BHT inclusion on post-thaw attributes of human semen. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2015;61(1):57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalthur G, Adiga SK, Upadhya D, Rao S, Kumar P. Effect of cryopreservation on sperm DNA integrity in patients with teratospermia. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(6):1723–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saritha KR, Bongso A. Comparative evaluation of fresh and washed human sperm cryopreserved in vapor and liquid phases of liquid nitrogen. J Androl. 2001;22(5):857–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martínez-Soto JC, Landeras J, Gadea J. Spermatozoa and seminal plasma fatty acids as predictors of cryopreservation success. Andrology. 2013;1(3): 365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomson LK, Fleming SD, Aitken RJ, De Iuliis GN, Zieschang JA, Clark AM. Cryopreservation-induced human sperm DNA damage is predominantly mediated by oxidative stress rather than apoptosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(9):2061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zribi N, Feki Chakroun N, El Euch H, Gargouri J, Bahloul A, Ammar Keskes L. Effects of cryopreservation on human sperm deoxyribonucleic acid integrity. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zorn B, Ihan A, Kopitar AN, Kolbezen M, Sesek-Briski A, Meden-Vrtovec H. Changes in sperm apoptotic markers as related to seminal leukocytes and elastase. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21(1): 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brugnon F, Ouchchane L, Pons-Rejraji H, Artonne C, Farigoule M, Janny L. Density gradient centrifugation prior to cryopreservation and hypotaurine supplementation improve post-thaw quality of sperm from infertile men with oligoasthenoterato-zoospermia. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(8):2045–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bateni Z, Azadi L, Tavalaee M, Kiani-Esfahani A, Fazilati M, Nasr-Esfahani MH. Addition of Tempol in semen cryopreservation medium improves the post-thaw sperm function. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2014;60(4):245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. NADPH oxidases, reactive oxygen species, and hypertension: clinical implications and therapeutic possibilities. Diabetes Care. 2008;31 Suppl 2:S170–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]