Abstract

Background:

In human, SRY (sex-determining region of the Y chromosome) is the major gene for the testis-determining factor which is found in normal XY males and in the rare XX males, and it is absent in normal XX females and many XY females. There are several methods which can indicate a male genotype by the presence of the amplified product of SRY gene. The aim of this study was to identify the SRY gene for embryo sex determination in human during pregnancy using loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method.

Methods:

A total of 15 blood samples from pregnant women at eight weeks of pregnancy were collected, and Plasma DNA was extracted. LAMP assay was performed using DNA obtained for detection of SRY gene. Furthermore, colorimetric LAMP assay for rapid and easy detection of SRY gene was developed.

Results:

LAMP results revealed that the positive reaction was highly specific only with samples containing XY chromosomes, while no amplification was found in samples containing XX chromosomes. A total of 15 blood samples from pregnant women were seven male embryos (46.6%) and eight female embryos (53.4%). All used visual components in the colorimetric assay could successfully make a clear distinction between positive and negative ones.

Conclusion:

The LAMP assay developed in this study is a valuable tool capable of monitoring the purity and detection of SRY gene for sex determination.

Keywords: Detection dyes, Embryo sexing, LAMP assay, Pregnancy, Sex determination analysis, SRY gene

Introduction

Molecular mechanisms of sex determination involve a growing network of genes, a large number, which are transcription factors. The transcription factors so far are identified as having a major role in sex determination (1). In humans, the gene for the testis-determining factor resides on the short arm of the Y chromosome. Individuals who are born with the short arm but not the long arm of the Y chromosome are male, while individuals born with the long arm of the Y chromosome but not the short arm are female (2). By analyzing the DNA of rare XX men and XY women, the position of the testis-determining gene has been narrowed down to a 35,000-base-pair region of the Y chromosome located near the tip of the short arm (3). In this region, a male-specific DNA sequence was found that could encode a peptide of 223 amino acids. This peptide is probably a transcription factor, since it contains a DNA-binding domain called the HMG (high-mobility group) box (4, 5). This domain is found in several transcription factors and non-histone chromatin proteins, and it induces bending in the region of DNA to which it binds (6). This gene is called SRY (sex-determining region of the Y chromosome), and there is extensive evidence that it is indeed the gene that encodes the human testis-determining factor (7–10).

Methods for sex determination using PCR for amplification of SRY gene have also been reported (11, 12). These methods can indicate a male genotype by the presence of the amplified product of SRY gene. Nonetheless, the need for trained staff, operating space, equipment, and reagents has impeded its usefulness (13). Hence, there has been an increasing demand for simple and cost-effective molecular tests. Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), a novel nucleic acid amplification method that relies on an auto-cycling strand displacement DNA synthesis, is performed by Bst DNA polymerase (14–17). Four or six primers that identify six or eight distinct regions are used in this method. It is operated under a constant temperature (60 to 65°C), and it eliminates the need for specialized thermal cycler equipment (18–23). An important advantage of LAMP is its ability to amplify specific sequences of DNA under isothermal conditions (24, 25). Detection of amplification product can be determined via turbidity caused by an increasing quantity of the magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate in solution (26–36). LAMP positive amplicons have been confirmed by adding a number of fluorescent dsDNA intercalating dye including ethidium bromide and SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II after the reaction is completed or metal indicators such as magnesium sulphate (MgSO4), calcium chloride (CaCl2), SYBR Green I, propidium iodide, GeneFinderTM, calcein, hydroxynaphthol blue (HNB), phenol red and Gel-RedTM prior to the reaction, allowing observation with the naked eye (37–40). The purpose of this study was to establish a rapid, sensitive, specific, and easy method to detect SRY gene using a visualized detection system.

Methods

Sample collection and plasma DNA extraction:

A total of 15 blood samples from pregnant women at eight weeks of pregnancy were collected. Another set of blood samples from non-pregnant women and men were also obtained using them as plasma negative and positive controls for the study, respectively. Fresh blood samples were drawn into Vacutainer EDTA tubes (BD Cat. 366643) immediately and were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min in a refrigerated centrifuge; their plasma fractions were collected and stored at −80°C for further analysis. Plasma DNA was extracted using QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen, Cat. 55114) by following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 2 ml of plasma was mixed with 200 μl proteinase K, 2.4 ml on ACL buffer by pulse-vortexing for 1 min in a 50 ml conical tube. Then the mixture was incubated in a 60°C water bath for 30 min. Then, 3.6 ml ACB buffer was added to the sample lysate and mixed by pulse-vortexing for 1 min, incubated for 5 min on ice and applied to the QIAamp mini column. Following the multiple wash and centrifugation steps, columns were incubated for 10 min at 56°C and DNA was eluted with 100 μl of AVE buffer and stored at −20°C for further analyses. The extraction quality of nucleic acid was confirmed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. The nucleic acid was stained with ethidium bromide. The purity of DNA was estimated by measuring the absorbance values at 260 nm and 280 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1700, Japan).

Amplification of SRY gene using LAMP:

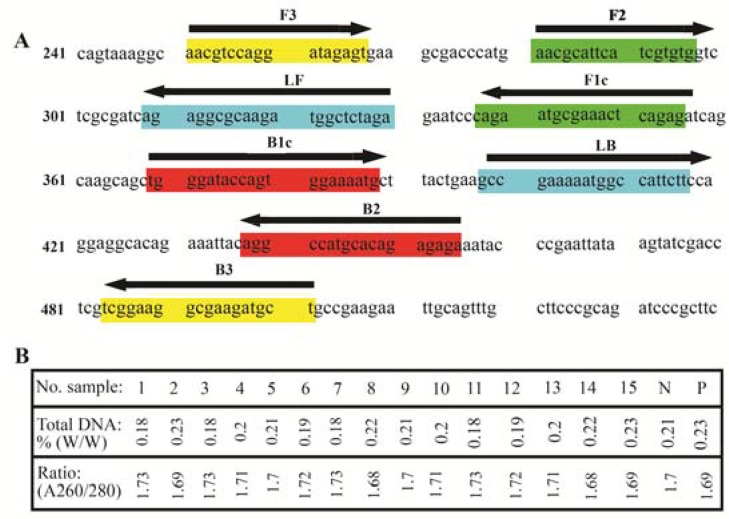

By means of the Primer Explorer V.4 software (specific for LAMP), specific primers were designed based on SRY genes (GenBank accession JQ811934.1) (Table 1). Figure 1A shows the schematic position of LAMP primers within SRY gene. A basic set of four primers was needed, including FIP (Forward Inner Primer), BIP (Backward Inner Primer), F3 (Forward Outer Primer), and B3 (Backward Outer Primer) to identify six distinct regions on the target DNA. To accelerate the LAMP reaction, two additional primers, i.e., LF (Loop Forward Primer) and LB (Loop Backward Primer) were also used. FIP consisted of the complementary sequence of F1, a T-T-T-T linker, and F2. BIP consisted of B1c, a T-T-T-T linker, and the complementary sequence of B2c. Primers F3 and B3 were located outside F2 and B2 regions, while loop primers LF and LB were located between F2 and F1 and between B1 and B2, respectively (13–16). Finally, the primers were tested for similarities with other sequences available in the GenBank databases using the BLASTN algorithm. LAMP assay was separately performed in a total volume of 25 μl using DNA obtained in a way described before, using designed primers in pregnant women, non-pregnant women (negative control) and men (positive control) samples. Initially, DNA was added to 23 μl of LAMP mixture to provide a final concentration of 20 mM supplied buffer (Thermopol buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH=8.8, 10 mM KCl, 10 (NH4)2SO4 mM, 0.1% Triton X100), 2 mM Betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM dNTP, 0.2 μM of primer F3 and B3, 0.4 μM of primer LF and LB, 0.8 μM of primer FIP and BIP and 8 U of Bst DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, UK). Tubes were then incubated at 63°C for 60 min in water bath. An agarose gel electrophoresis system (optional, 1.5%) under UV illumination could be also employed to visualize positive reaction.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for LAMP assay

| Name | Length | Sequence (5–3) | Length of product |

|---|---|---|---|

| F3 | 18 nt | AACGTCCAGGATAGAGTG | Fragment with different sizes |

| B3 | 18 nt | AGCATCTTCGCCTTCCGA | |

| FIB (F1c+F2) | 44 nt | ATCTCTGAGTTTCGCATTCTTTTTAACGCATTCATCGTGTGGTC | |

| BIP (B1c+B2) | 44 nt | TGGGATACCAGTGGAAAATGTTTTTCTCTCTGTGCATGGCCTGT | |

| LF | 22 nt | TCTAGAGCCATCTTGCGCCTCT | |

| LB | 22 nt | CCGAAAAATGGCCATTCTTCCA |

Figure 1.

A: Schematic representation of position primers used in LAMP assay; B: Quantity assessment of isolated DNA by spectrophotometric

Visual detection and confirmation of LAMP products (colorimetric assay):

The validations of positive LAMP reactions were justified by means of eight staining approaches. In doing so, several dyes were added to the LAMP reaction as described previously (40). Prior to amplification, 2 μl magnesium sulphate (8 mM MgSO4), 1 μl of GeneFinderTM (diluted to 1:10 with 6×loading buffer) (Biov. Bio. China), 1 μl of SYBR Green I (diluted to 1:10 with 6×loading buffer) (Invitrogen, Australia), 1 μl of the hydroxynaphthol blue dye (HNB) (3 mM, Lemongreen, Shanghai, China), 1 μl of phenol red (diluted to 1:10 with 6×loading buffer) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH) or 1 μl of the GelRedTM dye (Biotum, India) were separately added from a stock solution to the master mix. After amplification, 0.5 μl ethidium bromide (Sigma) and 2 μl SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Perfect Real-time, Takara Bio Co., Ltd., RR081A) were added to LAMP reaction separately. The tubes containing MgSO4, GeneFinderTM, SYBR Green I, HNB and phenol red dyes were easily monitored for color change by simply looking at them in daylight, while the ones containing GelRedTM, ethidium bromide and SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II were examined under UV light (302 nm) after a short vortex.

Results

DNA isolation:

DNA must be purified from cellular material in such a manner to prevent degradation. The absorbance ratios (A260/A280) of DNA samples were found to be in range of 1.68–1.73, indicating the purity of DNA (Figure 1B).

LAMP assay:

The initial optimization of the assay was conducted using a set of four basic primers, and optimal concentrations were determined. The reaction mixture was incubated at temperatures ranging from 60 to 65°C. The optimal temperature was found to be 63°C for 60 min. Values and concentrations of other components of the reaction were optimized. After detection of LAMP by gel electrophoresis, the smeared bands of amplified product indicated the positive reaction (Figure 2A). Our results revealed the positive reaction was highly specific only with fresh blood samples containing XY chromosomes, while no amplification was found in blood samples containing XX chromosomes. Our new LAMP protocol could successfully identify positive samples and positive control. LAMP amplicons were electrophoresed and a large number of fragments (a ladder like pattern) were eventually visualized. As shown in figure 2A typical ladder pattern of the amplified LAMP products with agarose gel electrophoresis was only observed for the positive samples and positive control. The LAMP assay showed no detectable amplification of other samples, including the negative control and negative samples. A total of 15 blood samples from pregnant women were seven male embryos (46.6%) and eight female embryos (53.4%). The authenticity of the results by the follow up was performed after delivery and finally the diagnosis of gender in 15 pregnant women was determined by plasma LAMP method.

Figure 2.

A: Gel electrophoresis pattern of LAMP amplicons on 1.5% agarose gel; B: Details of eight different visualization methods to analyze LAMP products. Lane M: DNA size marker (100 bp), lanes and tubes 1–7: positive samples, lanes and tubes 8–15: negative samples, lane and tube N: non-pregnant women sample (negative sample) and, lane and tube P: men sample (positive control)

Colorimetric assay:

LAMP amplicons could be detected with the naked eye by adding different visual dyes followed by color changing in the solutions. In this regard, all used visual components could successfully make a clear distinction between positive and negative ones (Figure 2B). It is noticeable that positive results by MgSO4, Gene-FinderTM, SYBR Green I, HNB, phenol red, Gel-RedTM, ethidium bromide and SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II were turbidity, green, green, sky blue, red, orange, yellow and green, respectively.

Discussion

The LAMP method, generally, had the following advantages over the other methods such as easy detection, high sensitivity, high efficiency, simple manipulation, safety, low cost and being user friendly. In reality, except for section one which takes equal time (see “Material and Methods” section), LAMP overall requires just 60 min to accomplish (as the least demanding detection method) (13–21). This, in turn, would simplify the detection procedure and result in saving significant time needed for separating the amplified products on the gel and analyzing the data which are commonly used in other PCR-based methods, including nested PCR, reverse transcription PCR, multiplex PCR and immunocapture PCR (29–39). Such visual methods not only involve some expensive instruments but also during a period of time, exposure to the UV light (because it is harmful to the eyes, even watching for a short period would irritate the eyes and cause symptoms similar to conjunctivitis) as well as ethidium bromide could induce a number of serious negative effects on researchers who use these methods (13). More surprisingly, in LAMP amplified products can be easily visualized by means of different in-tube color indicators with no essential requirement of additional staining systems; thus, toxic staining materials would be significantly avoided (39). Simple, cost effective and user friendly equipped labs with some molecular instruments as well as trained personnel are prerequisites to perform PCR assays (35). On the contrary, LAMP can be easily accomplished just in a water bath or temperature block with no need of thermocycler and gel electrophoresis as the same results were recorded by other researchers (29–40). Likewise, exclusive of the primer designing process which is somehow complicated and sensitive, other phases are simply applicable. On the other hand, the presence of LAMP positive amplicons proved to be confirmed by adding a number of fluorescent or metal dyes to the reaction tubes, allowing observation with the naked eye (24–37). In the current study, therefore, LAMP amplified products were confirmed by adding all aforementioned visual systems (see “Methods” section), either prior to or after the reaction along with forming diverse color patterns depending upon the chemical characteristics of the applied chemical substances as dye. According to our results, despite the precise detection of positive LAMP products using all dyes, some were significantly superior when the time of stability, cost and the safety were taken into consideration (Table 2). For instance, regardless of its reasonable color change stability (≥2 weeks), when employing ethidium bromide, a UV transilluminator must be available; both of them are toxic, resulting in deleterious consequences on human health and the environment (25–30). More interestingly, in some cases, just a little fluorescent emission could be observed in negative tubes, presumably arising from the presence of primers and/or DNA templates, leading to an increase in false-positive results (30–35). Alternative to such problems, the first metal dye called magnesium sulphate was utilized, but just an ephemeral color change (i.e. turbidity; no more than a few seconds) was observed as the same result was reported (31–39). Even though short stability of the color change probably cannot be a significant problem as long as just a few numbers of suspicious samples are used, during assessment of a great quantity of infected samples, most of the time, inaccurate results will be accordingly achieved (29–35). The method, nevertheless, could be thereby attributed as a reliable visual observation approach since on the one hand, it is exploited prior to the reaction and on the other hand, there is no need for toxic devices. Anyway, to provide a situation to increase time stability, the second fluorescent dye SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II was employed, leading to a clear green color pattern. Notably, regardless of observing a significant growth on time stability (about 1–3 days), the method not only requires UV transilluminator but also its stability is more negatively sensitive (in daylight). Indeed, since the dye must be added after the amplification as it requires opening of the tubes, the occurrence of cross-contamination risk will be accordingly enhanced (28–35). To avoid such contaminations, using separate rooms can be a solution for LAMP setup and analysis. More recently, it has also been pointed out that the visualized LAMP assay demands a high concentration of SYBR Green I, which will hamper the LAMP reaction if it is added before LAMP reaction, so the close-tube LAMP detection based on SYBR Green I might be difficult (32–38). To abbreviate the contamination hazard and also increase color stability, as a result, two additional metal indicators (i.e. HNB and GeneFinderTM) known as close-tube LAMP detection were lastly used. Interestingly, among several different visual dyes to accurately detect LAMP products, both HNB and GeneFinderTM could produce long stable color change and brightness in a close tube-based approach to prevent cross-contamination risk as the best alternatives (35, 37, 40). Two additional metal indicators (phenol red and GelRedTM) were added before LAMP reaction but UV transilluminator was required. Meanwhile, the visual inspection of LAMP products by means of HNB and GeneFinderTM metal dyes was seen as advantageous as there was no need for electrophoresis and subsequent staining with carcinogenic ethidium bromide (40). Lastly, the color brightness and stability of both HNB and GeneFinderTM in the solutions with positive/negative reactions remained constant after 2 weeks of exposure to ambient light, whereas turbidity caused by precipitation of MgSO4 or SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM II was stable for only 5–10 s and 1–3 days, respectively, which were in agreement with the results reported by previous researchers (35, 37, 39). However, the results obtained here represent those achievable in the research laboratory setting, and it is uncertain whether these results also apply to actual specimens compared with other LAMP assays (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of colorimetric assays for detection of SRY gene

| Visual system | Detection method | Safety | Positive reaction | Negative sample | Apply UV ray | Stability | Cross contamination | Use time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO4) | Visual | Yes | Turbidity | No turbidity | No | 5–10 s | No | Prior to amplification |

| GeneFinderTM | Visual | Yes | Green | Orange | No | 2–3 weeks | No | Prior to amplification |

| SYBR Green I | Visual | Yes | Green | Orange | No | 2–3 weeks | No | Prior to amplification |

| Hydroxynaphthol blue (HNB) | Visual | Yes | Sky blue | Violet | No | 2–3 weeks | No | Prior to amplification |

| Phenol red | Visual | Yes | Red | Orange | No | 1 week | No | Prior to amplification |

| Ethidium bromide | Visual | No | Yellow | No color | Yes | 2 weeks | Yes | After amplification |

| SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II | Visual | Yes | Green | No color | Yes | 1–3 days | Yes | After amplification |

| GelRedTM | Visual | Yes | Orange | No color | Yes | 2 weeks | No | Prior to amplification |

Table 3.

Comparison of different LAMP assays

| Assay | Detection method | Safety | Apply UV ray | Apply detect instruments | Cost | User friendly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP with gel detection | Gel electrophoresis | No | Yes | Yes | High | High |

| Colorimetric LAMP without UV | Visual | Yes | No | No | Very low | Very high |

| Colorimetric LAMP with UV | Visual | No | Yes | Yes | High | high |

Conclusion

In conclusion, sex determination using detection of SRY gene by LAMP method in fresh human blood shows the smear and/or ladder band only in male blood samples, but not in female samples. The LAMP assay developed in this study is a valuable tool capable of helping in monitoring the purity and identification of SRY gene for sex determination. LAMP method, all in all, had the following advantages over the other mentioned procedures: (I) no requirement for expensive and sophisticated tools in amplification and detection; (II) no post-amplification treatment of the amplicons; (III) a flexible and easy detection approach, by detecting with naked eyes using diverse visual dyes; (IV) high sensitivity; (V) high efficiency; (VI) safety; and (VII) being user friendly. This robust assay is quick, sensitive and specific enough to be applied for gene detection.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Young Researchers and Elites Club, North Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest. This study was supported by Islamic Azad University, North Tehran Branch.

References

- 1.Murakami H, Yamamoto Y, Yoshitome K, Ono T, Okamoto O, Shigeta Y, et al. Forensic study of sex determination using PCR on teeth samples. Acta Med Okayama. 2000;54(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assumpção JG, Benedetti CE, Maciel-Guerra AT, Guerra G, Jr, Baptista MT, Scolfaro MR, et al. Novel mutations affecting SRY DNA-binding activity: the HMG box N65H associated with 46, XY pure gonadal digenesis and the familial non-HMG box R30I associated with variable phenotypes. J Mol Med (Berl). 2002;80(12):782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimelli G, Gimelli S, Dimasi N, Bocciardi R, Di Battista E, Pramparo T, et al. Identification and molecular modelling of a novel familial mutation in the SRY gene implicated in the pure gonadal dysgenesis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15(1):76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellermayer R, Halvax L, Czakó M, Shahid M, Dhillon VS, Husain SA, et al. A novel frame shift mutation in the HMG box of the SRY gene in a patient with complete 46, XY pure gonadal dysgenesis. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2005;14(3):159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King TF, Conway GS. Swyer syndrome. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2014;21(6):504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips NB, Jancso-Radek A, Ittah V, Singh R, Chan G, Haas E, et al. SRY and human sex determination: the basic tail of the HMG box functions as a kinetic clamp to augment DNA bending. J Mol Biol. 2006; 358(1):172–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racca JD, Chen YS, Maloy JD, Wickramasinghe N, Phillips NB, Weiss MA. Structure-function relationships in human testis-determining factor SRY: an aromatic buttress underlies the specific DNA-bending surface of a high mobility group (HMG) box. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(47):32410–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizvi AA. 46, XX man with SRY gene translocation: cytogenetic characteristics, clinical features and management. Am J Med Sci. 2006;335(4):307–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahid M, Dhillion VS, Jain N, Hedau S, Diwakar S, Sachdeva P, et al. Two new novel point mutations localized upstream and downstream of the HMG box region of the SRY gene in three Indian 46,XY females with sex reversal and gonadal tumour formation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(7):521–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waters PD, Wallis MC, Marshall Graves JA. Mammalian sex--Origin and evolution of the Y chromosome and SRY. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(3): 389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos FR, Pandya A, Tyler-Smith C. Reliability of DNA-based sex tests. Nat Genet. 1998;18(2):103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thangaraj K, Reddy AG, Singh L. Is the amelogenin gene reliable for gender identification in forensic casework and prenatal diagnosis? Int J Legal Med. 2002;116(2):121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, Yonekawa T, Watanabe K, Amino N, et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(12):E63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirayama H, Katagiri S, Kageyama S, Minamihashi A, Moriyasu S, Sawai K, et al. Rapid sex chromosomal chimerism analysis in heterosexual twin female calves by Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007;101(1–2):38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang ZP, Zhang Y, Liu JP, Zhang JT, An ZX, Quan FS, et al. Codeposition of dNTPs detection for rapid LAMP-based sexing of bovine embryos. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009;44(1):116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan KW, Liu PC, Yang WC, Kuo J, Chang CL, Wang CY. A novel loop-mediated isothermal amplification approach for sex identification of Columbidae birds. Theriogenology. 2012;78(6):1329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanchanaphum P, Sarataphan T, Thirasan W, Anatasomboon G. Development of Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of SRY gene in human blood samples for sex determination. Rangsit J Arts Sci. 2013;3(2):129–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwamoto T, Sonobe T, Hayashi K. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, M. avium, and M. intracellulare in sputum samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2616–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori Y, Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective diagnostic method for infectious diseases. J Infect Chemother. 2009;15(2):62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadersdorfer J, Neumuller M, Treutter D, Fischer T. Fast and reliable detection of Plum pox virus in woody host plants using the Blue LAMP protocol. Ann Appl Biol. 2011;159(3):456–66. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardoso TC, Ferrari HF, Bregano LC, Silva-Frade C, Rosa AC, Andrade AL. Visual detection of turkey coronavirus RNA in tissues and feces by reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. Mol Cell Probes. 2010;24(6):415–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goto M, Honda E, Ogura A, Nomoto A, Hanaki K. Colorimetric detection of loopmediated isothermal amplification reaction by using hydroxyl naphthol blue. Biotechniques. 2009;46(3):167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu S, Qu G, Guo S, Ma L, Zhang N, Zhang S, et al. Applications of loop-mediated isothermal DNA amplification. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;163 (7):845–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almasi MA, Jafary H, Moradi A, Zand N, Ojaghkandi MA, Aghaei S. Detection of coat protein gene of the Potato Leafroll Virus by reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2013;4(1):156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moradi A, Nasiri J, Abdollahi H, Almasi MA. Development and evaluation of a loopmediated isothermal amplification assay for detection of Erwinia amylovora based on chromosomal DNA. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2012;133(3):609–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parida M, Shukla J, Sharma S, Ranghia Santhosh S, Ravi V, Mani R, et al. Development and evaluation of reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and real-time detection of the swine-origin influenza A H1N1 virus. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13(1):100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(5):877–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai SM, Chan KW, Hsu WL, Chang TJ, Wong ML, Wang CY. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of orf virus. J Virol Methods. 2009;157(2):200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmadi S, Almasi MA, Fatehi F, Struik PC, Moradi A. Visual detection of potato leafroll virus by one-step reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. J phytopathol. 2012;161(2):120–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dukes JP, King DP, Alexandersen S. Novels reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Arch Virol. 2006;151(6):1093–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almasi MA, Hosseyni-Dehabadi SM, Aghapour-Ojaghkandi M. Comparison and evaluation of three diagnostic methods for detection of Beet Curly Top Virus in sugar beet using different visualizing systems. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;173(7): 1836–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almasi MA, Moradi A, Nasiri J, Karami S, Nasiri M. Assessment of performance ability of three diagnostic methods for detection of Potato Leafroll Virus (PLRV) using different visualizing systems. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;168(4):770–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almasi MA, Dehabadi SH, Eftekhari Z. Immunocapture loop mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of Tomato Yellow Leaf curl Virus (TYLCV) without DNA extraction. J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2013;4(7):185. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almasi MA, Hosseini SMD, Moradi A, Eftekhari Z, Ojaghkandi MA, Aghaei S. Development and application of loop-mediatred Isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici. J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2013;4(5):177. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moradi A, Almasi MA, Jafary H, Mercado-Blanco J. A novel and rapid loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the specific detection of Verticillium dahlia. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;116(4):942–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuta S, Iida T, Mizukami Y, Ishida A, Ueda J, Kanbe M, et al. Detection of Japanese yam mosaic virus by RT-LAMP. Arch Virol. 2003;148(9): 1713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almasi MA, Erfan manesh M, Jafary H, Dehabadi SM. Visual detection of Potato Leafroll virus by one-step reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA with the genefinderTM dye. J Virol Methods. 2013;192(1–2):51–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almasi MA, Ojaghkandi MA, Hemmatabadi A, Hamidi F, Aghaei S. Development of colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of the Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2013;4(1):153. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almasi MA, Aghapour-ojaghkandi M, Bagheri K, Ghazvini M, Hosseyni-dehabadi SM. Comparison and evaluation of two diagnostic methods for detection of npt II and GUS genes in Nicotiana tabacum. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;175(8): 3599–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almasi M. Establishment and application of a reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for detection of grapevine Fanleaf Virus. Mol Biol. 2016;5(1):149. [Google Scholar]