Short abstract

Most amnesic conditions in films bear little relation to reality. Since movies both inform and reflect public opinion, doctors should be aware of the prevalent myths about amnesia. This could be invaluable when informing patients and their relatives of a diagnosis of an amnesic condition and its likely prognosis

Although clinically rare, profound amnesia is a common cinematic device. In 1915, film makers spotted the dramatic potential of an amnesic syndrome, and it has continued to provide the vehicle for both tragedy and comedy. This review examines the frequent misconceptions and occasionally strikingly accurate portrayals of amnesic syndromes with reference to the scientific and medical case literature.

Early cinema

Hollywood's recent offerings, The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and 50 First Dates (2004), head up a long tradition of movies featuring amnesic characters. No fewer than 10 silent movies (before 1926) do so. In one of the earliest, Garden of Lies (1915), predictable complications ensue when a doctor hires a new husband for an amnesic bride in an attempt to jog her memory. This film was an early trendsetter, and nuptials have precipitated amnesia in later films (Samaya, 1975; Kisses for Breakfast, 1941). In 1915 The Right of Way was one of the first films to depict amnesia as the result of an assault, and the trigger for starting life afresh. These themes are seen again in The Victory of Conscience (1916) and have been consistently used throughout the decades to modern times (see Amateur,1994).

Figure 1.

50 First Dates maintains a venerable movie tradition of portraying an amnesiac syndrome that bears no relation to any known neurological or psychiatric condition

Credit: COLUMBIA/KOBAL/DARREN MICHAELS

Amnesic syndromes

In the real world, most profound amnesic syndromes have a clear neurological or psychiatric basis. True dissociative amnesia or fugue states are rare, but people with such conditions are able to learn new information and perform everyday tasks in the context of a profound retrograde amnesia triggered by a traumatic event. The most commonly agreed features of organic amnesic syndromes include normal intelligence and attention span, with severe and permanent difficulties in taking in new information. Personality and identity are unaffected. These distinctions, which in a medical setting are critical in terms of prognosis and treatment, are often blurred at the movies.

The most profound amnesic syndromes usually develop as a result of neurosurgery, brain infection, or a stroke. These factors are overlooked at the movies in favour of the much more dramatic head injury. Road traffic crashes and assault are the most common causes for amnesia in movie characters. Although post-traumatic amnesia is common in survivors of road crashes and assaults in the real world, the profound loss of identity and autobiographical knowledge repeatedly portrayed at the movies is unrealistic. So when Santa falls from his sleigh and loses his identity in Santa Who? (2000) the medically astute viewer may suspect a psychiatric rather than a neurological basis for his profound amnesia.

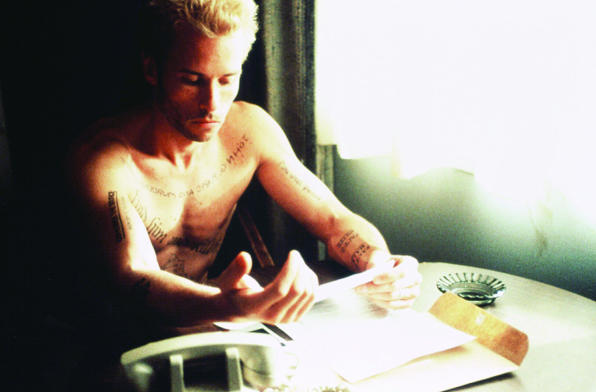

Figure 2.

In The Bourne Identity and again in The Bourne Supremacy (shown here), Jason Bourne struggles with amnesia, which, according to Hollywood, is something of an occupational hazard for professional assassins

Credit: UNIVERSAL STUDIOS/IMAGENET

Some movies fully embrace a psychological basis for a loss of identity when their characters become amnesic after they witness a traumatic event, such as the murder of a husband (see L'Assassino e al Telefono, 1972) or mother (see Hellhole, 1985). Murdering is not a picnic, however, and the killers themselves can also become amnesic if it all gets unexpectedly messy or the killer suffers a powerful attack of conscience (see Garden of Lies, 1915; Snapdragon, 1993; and Insaniac, 2002). Dramatic shipwrecks result in amnesia in at least three films (A Modern Cain, 1921; The White Pearl, 1915; The New Adventures of Black Beauty, 1992), and in a cautionary tale for aspiring surgeons everywhere, in Dangerous Intrigue (1936) the shock of (unavoidable) professional failure is enough to cause a brilliant young surgeon to lose his identity. In a more psychologically sensitive and accurate study Les Dimanches de Ville d'Avray (1962) portrays delayed stress and partial amnesia in a pilot who killed a child on a routine bombing mission in Vietnam.

Many amnesic movie characters do not have noticeable everyday memory difficulties and manage to create and maintain entirely new vocational and social networks shortly after their neurological injuries. Thus in Finding the Way Home (1991) 60 year old Max, an antiques dealer, finds new meaning in life working as a farm hand, and in The Matrimonial Bed (1930) a wealthy landowner starts a new life (complete with a new wife) as a hairdresser after amnesia brought on by a train crash.

In Hollywood trained assassins have an unfortunate tendency to forget their vocation, and in both The Bourne Identity (2002) and The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996) the hunter becomes the prey after the onset of amnesia. A different perspective is taken in the amusing parody The Bourne Identity Crisis (2003), when the lead character forgets that he is gay and thinks he is a trained assassin instead.

On the right side of the law, police officers also seem to be particularly prone to amnesia in the movies, particularly when they reach a vital part of their investigation (see Clean Slate, 1994; Violence, 1947; In the Shadow of Evil, 1995; Tough and Deadly, 1995). Despite their profound memory difficulties these amnesic characters are not “signed off sick” and valiantly manage to complete their investigations.

These scenarios are neurologically improbable, but some amnesic syndromes in the movies bear no relation whatsoever to any authentic neurological or psychiatric condition. For example, although the unfortunate hero in Clean Slate (1994) has no difficulties in laying down new memories during wakefulness, these memories are obliterated by sleep and he awakes to a “clean slate” every morning. This idea has recently been revived in 50 First Dates (2004), in which Adam Sandler attempts to woo Drew Barrymore, who forgets their previous encounters with each new day. Some viewers might envy Ms Barrymore's ability to forget her romantic encounters with Mr Sandler, but her affliction seems to be the result of a head injury rather than the unconscious suppression of traumatic memories. The idea is turned on its head in Groundhog Day (1990), where only the hero retains any recall of the previous day's events whereas the rest of the world suffers a collective and global amnesia, perpetually reliving the same day without any recollection.

Personality change

Amnesia not only frequently results in a loss of identity in the movies, it also commonly causes a complete personality change. This can just mean a character becomes more extroverted or introverted, but usually it involves a complete shift in values and behaviour. Thus a startling number of originally “bad” characters become “good” after the onset of their amnesia. In Crime Doctor (1943) a shady criminal becomes a leading criminal psychologist; the “claw hammer killer” becomes a nice guy in Murder by Night (1989) (or does he?), and in one of the earliest cinematic examples a roguish cad becomes a valued parish priest in The Victory of Conscience (1915). Goldie Hawn's rich spoilt socialite transforms into a loving mother to Kurt Russell's unruly brood when she falls from her yacht in Overboard (1987), and even Tom the cat forgets himselfand makes up with Jerry the mouse after his head injury in Nit-Witty Kitty (1951). Sadly, this transformation doesn't always last. Occasionally in the movies, amnesia results in a personality change for the worse (see The Back Trail, 1924; Delux Annie, 1918).

Movies also occasionally endow their amnesic sufferers with superhuman powers, presumably to replace their ordinary lost faculties. Thus paranormal sensations are explored in See Jane Run (1995) and Insaniac (2002), and there are no holds barred in Uchu no Kishi Tekkaman Bureido (1994), in which an amnesic with no idea of his identity can nevertheless transform himself into “Teknoman,” an unstoppable fighting machine. The arrival of an amnesic patient at a hospital coincides with the opening of the “Dead Pit” in the film of the same name, unleashing an evil doctor who clearly has not been keeping up to date with his medical education during his enforced incarceration in the vault.

Figure 3.

Jim Carrey's memories take a bit of a pounding in The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind thanks to one of those high tech memory erasing devices so beloved of moviemakers

Credit: FOCUS FEATURES/EILEEN KURUS/REX

Recovery

One of the most neurologically bizarre features of cinematic amnesia is the universal embrace of the “two is better than one” approach when it comes to head injury. In countless movies, the amnesic character is restored to full faculty, identity, and personality after a second bang on the head. From Tom the cat to Tarzan in Tarzan the Tiger (1922), it seems that all these characters require is another serious head injury to recover. Although a second traumatic event may serve as abreaction or a cure for some dissociative amnesic states, this seems unlikely in the event of two severe neurological insults. The “mix and match” approach to recovery is taken one stage further in Singing in the Dark (1956), when recovery from amnesia with a psychological basis (deep trauma associated with the holocaust) is kickstarted by a blow to the head.

Figure 4.

As an honourable exception, Memento accurately describes the problems faced by someone with severe anterograde amnesia

Credit: SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT/KOBAL

The other popular mechanism for the return of memory function and identity is an encounter with familiar objects from the past; these can range from a single item, such as a panelled door in The Woman with no Name (1950), to a rich array of experiences, such as a tour around old haunts (see Le Gendarme en Balade, 1970; Saved by the Bells, 2003). Hypnosis is used to cure several characters, including the unfortunate Leopold in The Matrimonial Bed, when it has the unfortunate side effect of erasing five years of his “new” memories (also see Dead Again, 1991). The regaining of old memories only to lose the new ones is also seen in Streets of Memory (1940).

Interestingly, although it is occasionally depicted as the source of an amnesic syndrome, neurosurgery is usually portrayed as a viable treatment option. In Deluxe Annie (1918) neurosurgery restores Annie's memory, while in Rascals (1938) a socialite works as a fortune teller to raise money for an operation to restore her memory.

Though the options for recovery remain limited in the movies, the imperative can be high. Protagonists are often in grave danger while their amnesia persists. They may become potential murder victims (see With a Vengeance, 1992; Unstable Minds, 2002) or be convicted of crimes they did not commit (Two in the Dark, 1936; Two O'Clock Courage, 1945). The wellbeing of an entire region rests on the shoulders of an engineer who has become amnesic after a nuclear incident in Chain Reaction (1980).

Of course, in movies it is not always desirable to recover lost memories. Several films in the science fiction genre have used high tech memory erasing devices to help their characters forget. Thus Jim Carrey willingly signs up to have his memory of a failed relationship erased in The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2003), and in Men in Black and its sequel the eponymous heroes frequently erase the public's memories of their extraterrestrial encounters for societal good and sanity. However, a force for good in one person's hands can be a force for evil in another's, with memory erasing devices being used to control and rule. Fortunately, the likes of Ben Affleck (Paycheck, 2003) and the current governor of California (Total Recall, 1990) are strong enough to overcome these electronic attempts at memory suppression.

Doppelgangers

In the real world, the prevalence of true amnesic syndrome, particularly after a head injury, is extremely low. In addition, the existence of a doppelganger—a lookalike so similar as to fool your loved ones—is almost unknown, even among monozygotic twins. Nevertheless, several films (such as The Great Dictator, 1940; The Majestic, 2001) have combined the concept of amnesia and doppelgangers. In many of these the combination of amnesia and a likeness to another individual allows the character to easily adopt a new persona. However, credulity is stretched beyond limits in X-paroni (1964), a Finnish comedy in which two unrelated but identical men both become amnesic and begin to live the other's life more successfully than their original one.

Honourable exceptions

The overwhelming majority of amnesic characters in films bear little relation to any neurological or psychiatric realities of memory loss. However, three films deserve special consideration. In Se Quien Eres (2000) a psychiatrist treats a patient with Korsakoff's syndrome. Although there is some dramatic license, the writers and director have clearly done their research into the condition.

Memento (2000) also deserves a special mention. Apparently inspired partly by the neuropsychological studies of the famous patient HM (who developed severe anterograde memory impairment after neurosurgery to control his epileptic seizures) and the temporal lobe amnesic syndrome, the film documents the difficulties faced by Leonard, who develops a severe anterograde amnesia after an attack in which his wife is killed. Unlike in most films in this genre, this amnesic character retains his identity, has little retrograde amnesia, and shows several of the severe everyday memory difficulties associated with the disorder. The fragmented, almost mosaic quality to the sequence of scenes in the film also cleverly reflects the “perpetual present” nature of the syndrome.

It is perhaps ironic that one of the most neuropsychologically accurate portrayals of an amnesic syndrome at the movies comes not from a human character but an animated blue tropical fish. In Finding Nemo (2003) Dory is a fish with profound memory disturbance. The aetiology is unclear, but her difficulties in learning and retaining any new information, recalling names, and knowing where she is going or why are an accurate portrayal of the considerable memory difficulties faced daily by people with profound amnesic syndromes. The frustration of the other fish around her with constant repetition also accurately reflects the feelings of people who live with amnesic patients. Although her condition is often played for laughs during the film, poignant aspects of her memory loss are also portrayed, when she is alone, lost, and profoundly confused.

Summary

Although amnesia is a popular cinematic device, this review reveals several profound misconceptions about the condition.

Most films make no distinction between amnesic syndromes with a psychiatric basis and those with an underlying neurological cause. In the real world the aetiology of an amnesic syndrome is critical in terms of its prognosis and treatment; but a “mix and match” approach is adopted in the movies.

In the real world, post-traumatic amnesia is common after a head injury, and deficits in the learning and retention of new information are often seen the early stages of recovery. In the movies, however, head injuries often result in a profound retrograde amnesia with the capacity for new learning left completely intact.

Two head injuries are better than one at the cinema. One of the commonest “cures” for an amnesic syndrome sustained as a result of a severe head injury is another head injury.

In most films memories are not lost, just made temporarily inaccessible. Recovery of memory is possible, via various unlikely means.

These myths seem to be universal and occur in films from all around the world. The medical profession cannot, and indeed should not, dictate cinematic content. However, since movies both inform and reflect public opinion, the public seems to have very little understanding of amnesic syndromes. Amnesia as portrayed in the movies is more in keeping with a psychiatric than an organic cause. Clinicians should be aware of this when talking to patients and their relatives.

Supplementary Material

Details of the films mentioned in this article are listed on bmj.com

Details of the films mentioned in this article are listed on bmj.com

Competing interests: None declared.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.