Abstract

Although palliative care consultation teams are common in U.S. hospitals, the follow-up and outcomes of consultation for frail older adults discharged to nursing facilities are unclear. To summarize and critique research on the care of patients discharged to nursing facilities following a hospital-based palliative care consult, a systematic search of PubMED, CINAHL, Ageline, and PSYCINFO was conducted in February 2016. Data from the articles (n = 12) were abstracted and analyzed. The results of 12 articles reflecting research conducted in five countries are presented in narrative form. Of the studies, two focused on nurse perceptions only, three described patient/family/caregiver experiences and needs, and seven described patient-focused outcomes. Collectively, these articles demonstrate that disruption in palliative care service upon hospital discharge and nursing facility admission may result in high symptom burden, poor communication, and inadequate coordination of care. High mortality was also noted.

Keywords: hospitalization, palliative care, patient discharge, nursing homes, continuity of patient care

Palliative care is person-centered care provided at any point in the illness trajectory to patients with serious or life-limiting disease and their families. Its focus is on pain and symptom management, communication about individual goals of care and treatment choices, and psychological and spiritual support. Palliative care improves quality of life and reduces suffering (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013; World Health Organization, 2015).

Over the past 15 years, there has been a threefold increase in the number of palliative care teams in inpatient hospital settings; more than 60% of hospitals with 50 beds or more report presence of a palliative care team (Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2014; Dumanovsky et al., 2016). Multiple studies have explored the impact of hospital-based palliative care consultation on patient care and outcomes, financial impact, and the patient’s and family caregiver’s satisfaction with care (Cassel, Webb-Wright, Holmes, Lyckholm, & Smith, 2010; Chand, Gabriel, Wallace, & Nelson, 2013; May, Normand, & Morrison, 2014). Overall, the literature reports favorable outcomes on pain and symptom management, quality of care, hospital costs, and patient and family satisfaction during hospitalization. However, this empirical evidence is limited in that it does not examine the impact on care that is delivered during and after discharge.

Care coordination and continuity across settings, including planning for hospital discharge, are considered core components of palliative care (Institute of Medicine, 2014; National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2013). Preparation for hospital discharge for patients with life-limiting illness is often complex due to the unpredictable illness trajectory, shifting goals of care, and availability of resources to meet patients’ needs. Manfredi et al. (2000) found that their palliative care team contributed to the discharge plan for more than 80% of the patients seen for a palliative care consultation. The majority of patients were cared for in the hospital until death, discharged with hospice support, or discharged with outpatient palliative care. The remaining patients were discharged to a nursing home or sent home with home health care. It is unclear whether palliative care resources were available beyond the hospital, especially for frail older adults discharged to nursing facilities. Other researchers report that up to 49% of patients who received a palliative care consult in the hospital underwent discharge to a nursing facility (Cassel et al., 2010; Ciemins, Blum, Nunley, Lasher, & Newman, 2007; Cowan, 2004; Hanson, Usher, Spragens, & Bernard, 2008). The purpose of this paper is to present the findings of an integrative literature review that focuses on the care of patients discharged to nursing facilities following a hospital-based palliative care consult.

Methods

Search Strategy

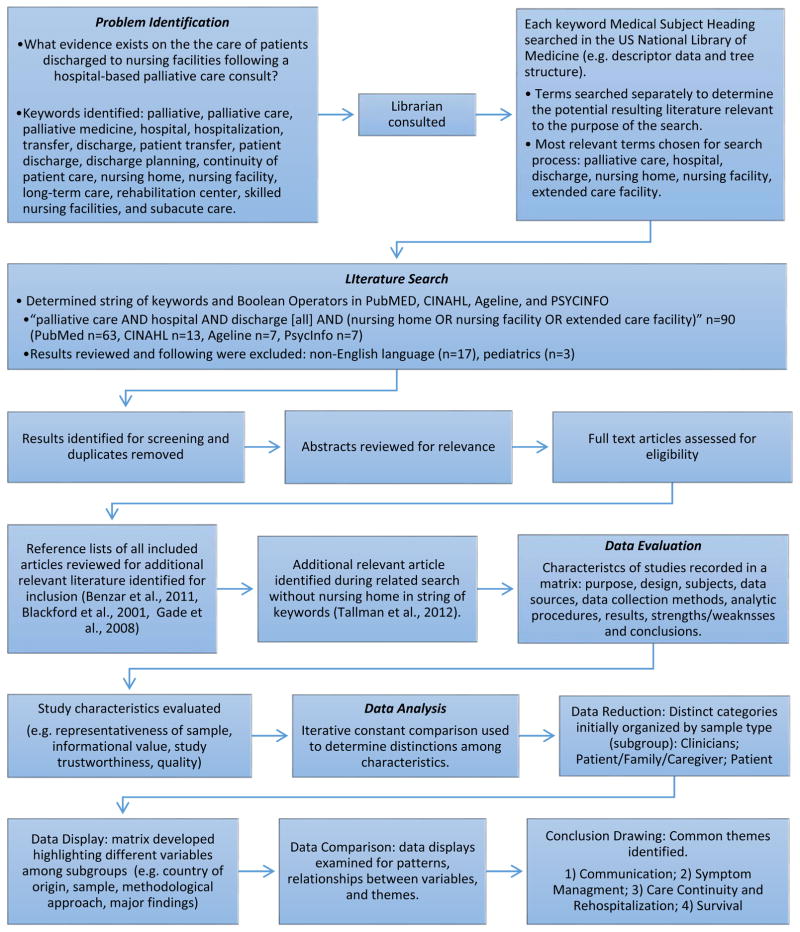

MeSH and non-MeSH terms to identify possible articles for inclusion in the review included palliative, palliative care, palliative medicine, hospital, hospitalization, transfer, discharge, patient transfer, patient discharge, discharge planning, continuity of patient care, nursing home, nursing facility, long-term care, rehabilitation center, skilled nursing facilities, and subacute care. Four electronic databases (PubMED, CINAHL, Ageline, and PSYCINFO) were searched using the following search strategy: “palliative care AND hospital AND discharge [all] AND (nursing home OR nursing facility OR extended care facility).” No limits in dates were applied in order to capture all research. All English-language articles in the databases as of February 2016 were included. Articles were limited to adults. Because this review integrated data from diverse studies, both experimental and nonexperimental, recommendations from Whittemore & Knafl (2005) guided the review approach (see Figure 1). The 27 preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) recommendations provided additional guidance for this review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

Figure 1.

Review Method Steps

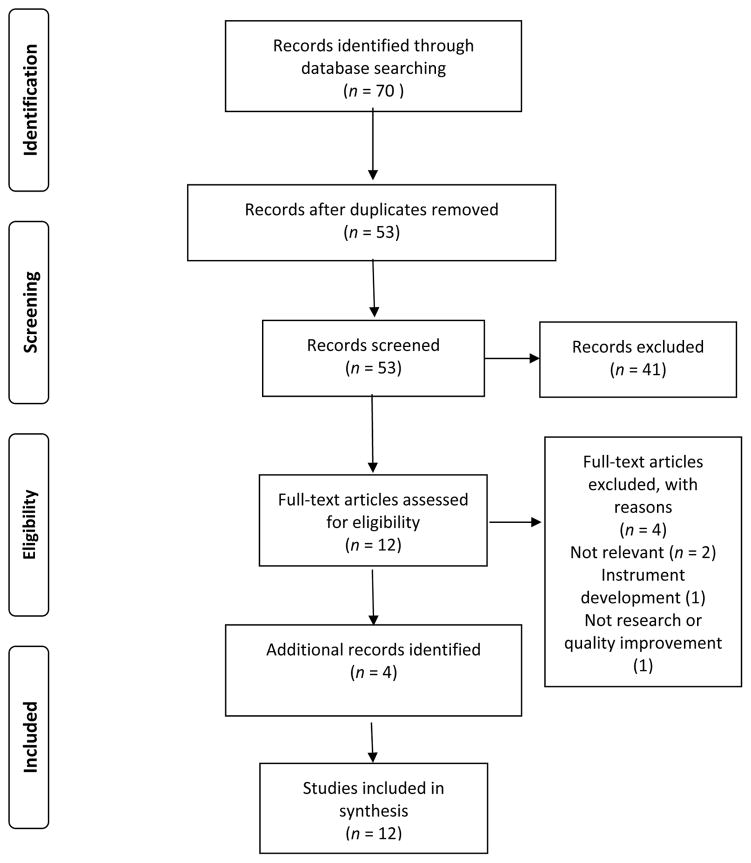

Retrieved titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and individual articles were assessed for inclusion (see Figure 2). To be included, a study needed to address inpatient hospital palliative care, illness trajectory after hospital discharge, and/or post hospitalization discharge follow-up involving the nursing facility setting. Additional studies were excluded if authors reported only on tool testing and development, hospital mortality or in-hospital outcomes, hospice outcomes, palliative home care, or home discharge without inclusion of a nursing facility. Studies that focused on hospice care were excluded due to the empirical evidence that palliative care outcomes are improved when nursing home residents receive hospice care (Stevenson & Bramson, 2009).

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram of Article Selection

Analysis

Data were abstracted and analyzed systematically and entered into a matrix with the following topics: (a) study year and authors, (b) study location/setting, (c) research question/hypothesis, (d) study design, (e) sample characteristics, (f) results, (g) strengths, (h) limitations, (i) clinical implications, and (j) research implications. Studies were then categorized by sample type: Clinicians, Patient/Family/Caregiver, and Patient. Clinician studies included those in which the researchers described nurse perceptions of palliative care patients’ needs after hospital discharge and the nurses’ role in maintaining continuity in patient care. Data for these studies were collected through focus groups and semistructured interviews. Patient/Family/Caregiver studies described outcomes during and after hospitalization of palliative care interventions targeted at family caregivers, determined how palliative care teams could prepare patients for discharge, and established an understanding of the patient/family experience after discharge. Surveys, individual interviews, videos, and medical records provided the data in these studies. Patient studies focused strictly on patient outcomes during and after hospitalization and primarily relied on administrative databases and surveys for data collection.

To minimize bias, an iterative approach to analysis with constant comparison techniques to explore patterns and themes was employed. A report maintaining a log of events during data collection and analysis was kept (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Results

The literature review included 12 articles from all searches and reflected research conducted in five countries from 2001 to 2013. Indicating the recent growth of palliative care research, 10 articles were published between 2010 and 2015. All articles were original research studies or quality improvement reports published in peer-reviewed journals. Table 1 details the country of study origin, author, and publication year and Table 2 includes study information.

Table 1.

Study Origin, Authors, and Year

| Country of Origin | Authors and Year |

|---|---|

| United States (n = 8) | Baldwin et al. (2013); Benzar, Hansen, Kneitel, & Fromme (2011); Brody, Ciemins, Newman, & Harrington (2010); Catic et al. (2013); Enguidanos, Vesper, & Lorenz (2012); Fromme et al. (2006); Gade et al. (2008); Tallman, Greenwald, Reidenouer, & Pantel (2012) |

| Australia (n = 1) | Blackford & Street (2001) |

| United Kingdom (n = 1) | Gerrard et al. (2011) |

| Germany (n = 1) | Kötzsch, Stiel, Heckel, Ostgathe, & Klein (2014) |

| Norway (n = 1) | Thon Aamodt, Lie, & Helleso (2013) |

Table 2.

Main Categories of Literature

Communication

|

Symptom Management

|

Care Continuity & Rehospitalization

|

Survival

|

Methodological approaches varied, though most studies were pilot work or descriptive (Benzar, Hansen, Kneitel, & Fromme, 2011; Blackford & Street, 2001; Catic et al., 2013; Thon Aamodt, Lie, & Helleso, 2013). Three studies were longitudinal over a one- to two-year period (Fromme et al., 2006; Kötzsch, Stiel, Heckel, Ostgathe, & Klein, 2014), including one ethnography (Tallman, Greenwald, Reidenouer, & Pantel, 2012). Hospital databases were used to conduct retrospective cohort and matched case control studies (Baldwin et al., 2013; Brody, Ciemins, Newman, & Harrington, 2010; Enguidanos, Vesper, & Lorenz, 2012). One randomized control trial (Gade et al., 2008) and one quality improvement project with repeated measures over a two-year period were reviewed (Gerrard et al., 2011).

Researchers focused on nurse perceptions only (two international studies); patient/family/caregiver-oriented research outcomes (two US studies, one international study), and patient-oriented outcomes only (seven US studies, two international studies). Four themes across the three sample categories were (a) symptom management (e.g., ability to manage, education, information, unmet needs); (b) communication (e.g., clarity, respecting choices, participation in advance-care planning); (c) care continuity and hospital readmission (e.g., who to contact, timely access to care, care trajectory); and (d) patient survival. Refer to Table 3 for additional details.

Symptom Management: Physical, Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Needs

Researchers in four studies focused on patients’ symptom management needs postdischarge—three studies were qualitative, and one was an observational study. Findings of the four together indicated that disruption in palliative care service upon hospital discharge and nursing facility admission was concerning due to inadequate coordination of symptom management interventions between the hospital and nursing facility.

The leading concern of ten bachelor’s prepared inpatient oncology nurses in a Norway hospital planning for patient discharge to a nursing home was the lack of clinical capacity and palliative care experience of the nurses in the receiving facility. The hospital nurses felt that patients should only be discharged to a nursing home when pain was well controlled. If the nursing home had a specialty palliative care unit, hospital nurses perceived better care delivery, especially for older adults with functional limitations, multiple chronic conditions, and fluctuating symptoms (Thon Aamodt et al., 2013).

Patients with various life limiting diagnoses and their family caregivers in two descriptive studies identified concerns about their own ability to identify and relieve symptoms after hospital discharge, even with a palliative care consult that included substantial emphasis on symptom management. Instructions for managing symptoms were not written down, counseling regarding medication dose adjustment did not take place, and new problems with existing symptoms occurred. Despite having access to medical and nursing care, family members reported dissatisfaction with the care their family members received in nursing facilities (Benzar et al., 2011; Tallman et al., 2012).

Baldwin et al. (2013) used proxy measures to identify potential palliative care needs of 228 medical intensive care unit survivors discharged for postacute care in nursing facilities. Proxy measures were defined as characteristics indicative of palliative care needs (e.g., presence of wounds indicating symptom burden, psychological distress such as delirium, and poor prognosis including advanced cancer) identified by expert input, clinical practice guidelines, and empirical evidence. They found that 88% of the study sample had one or more potential palliative care needs.

Researchers’ longitudinal study of patients and families greatly expanded observation and reporting of ongoing symptom needs after hospital discharge. Family caregivers reported not only that psychological, social, and spiritual needs are very important during the hospital palliative care consult but also that these needs appear to persist months after discharge. However, when other issues (e.g., pain or dyspnea) were more noticeable, psychological, social, and spiritual needs seemed less important to patients and family caregivers (Tallman et al., 2012). Baldwin et al. (2013) also reported that unmet psychological and spiritual needs are especially prominent in older adults discharged to nursing facilities after an intensive care unit stay during hospitalization.

Communication

Poor communication and unmet needs for information and education in the postdischarge setting were reported as problematic by patients, family caregivers, and nurses in three studies (Benzar et al., 2011; Blackford & Street, 2001; Tallman et al., 2012). This finding was true even for those patients who had recently left the hospital; some patients and family caregivers did not recall the palliative care team specialists from the hospital consult. When concerns did arise, there was difficulty in determining the best person to answer a question due to the complexity of the health care system. In the months following palliative care consults, patients and family caregivers reported that they continued to require information about advanced illness. In contrast, other researchers found that engaging patients and family caregivers in ongoing communication, education, and advance-care planning during and after discharge may result in clearer expectations and care aligned with preferences (Catic et al., 2013; Gerrard et al., 2011).

In the reviewed studies, nurses, patients, and family caregivers reported communication was very important. Palliative care nurses reported that ineffective communication with primary care providers of discharged patients negatively impacted care in the nursing home setting (Blackford & Street, 2001). Ineffective communication was described as delays in discharge summaries or transfer notes making it to the postdischarge setting and lack of detail or full information about the events during hospitalization. “Professional territorialism” (Blackford & Street, 2001, p. 276)—that is, the perception of nurses acting outside of their usual role—weakened lines of communication and resulted in unreturned phone calls and an inability to connect with primary care providers after transition of care.

Tallman et al. (2012) noted in an ethnographic study of 12 patient/family caregiver cases (of which 2 were originally discharged to nursing facilities) over one year that family caregivers’ need for clear communication of information increased in the postdischarge setting. When discussing needs and concerns, caregivers reported that setting clear expectations for disease trajectory and what to expect in the future was important during the initial palliative care consult. Interruptions in care continuity after discharge were primarily related to how to initiate communication about a new or recurrent issue or symptom, especially for those not using hospice care (Tallman et al. 2012; Benzar et al., 2011).

Palliative care team communication and goals-of-care discussions included asking patients where they want to receive care in the postdischarge period; for some patients with life-limiting illness, this might be the preferred place of care until death. Gerrard et al. (2011) described their U.K. healthcare system’s palliative care team’s effort to meet patients’ requests to remain in their preferred place of care until death. In this quality improvement project, the stated preferred place of care at discharge was also defined as the preferred place of death for terminally ill patients. Over a two-year period (2007–2009), the percentage of match between the nursing home as the stated preferred place of care and nursing home death increased from 53% to 100%. The study did not reference where goals were documented and how these outcomes were achieved, thus limiting its usefulness.

A pilot study in the United States that targeted communication, education, and follow-up with family caregivers/proxy decision makers of people with dementia resulted in greater reported communication and advance-care planning discussions at one month postdischarge (Catic et al., 2013). A key component of this intervention provided specific follow-up with the family caregiver/proxy decision maker two weeks after discharge to review health status, goals and decision making, and need for information. Detailed information about the palliative care consult was also sent to the patient’s primary care provider.

Care Continuity and Hospital Readmission

In whole, the authors’ findings in 10 studies suggested that continuity of care hinges on regular, interactive dialogue among patients, family caregivers, and health care providers throughout the course of illness. Researchers who noted lower hospital readmission rates for palliative care patients and more stable care trajectories cited the discharge planning process and continual interaction as the reasons for improved outcomes.

In the posthospital period, nurses and family caregivers of patients who received palliative care during hospitalization reported greater use of medical services when new symptoms required a change in the plan of care. Often, frequent visits to the emergency department and subsequent rehospitalization occurred for acute changes that needed immediate resolution (Tallman et al., 2012; Thon Aamodt et al., 2013). Acute care nurses in Norway anticipated rehospitalization for patients’ symptoms that could not be managed in a nursing home (Thon Aamodt et al., 2013).

Enguidanos et al. (2012) observed that of all patients who received palliative care consults and were discharged to nursing facilities, 24% were readmitted at one month. When compared to patients discharged with hospice or home palliative care, patients discharged to nursing facilities were five times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of hospital discharge. Baldwin et al. (2013) showed that 37% of the sample with potential palliative care needs were readmitted to the hospital from nursing facilities at six months (approximately 20% of the sample lived in a nursing home before hospital intensive care admission). Fromme et al. (2006) found that only 10% of their sample was readmitted at one month; but it is not clear what proportion of these patients were discharged to and readmitted from nursing facilities (20% of the entire sample transferred to a nursing facility after hospitalization). Despite high hospital readmission rates for palliative care patients, when compared to those receiving usual care, researchers reported that costs were overall reduced, including for those in a skilled nursing facility after palliative care consult during hospitalization (Gade et al., 2008). It is unclear if reduced costs were associated specifically with nursing home discharge rates in this sample.

U.S. researchers found a lower hospital readmission rate at one month after discharge with a palliative care education and support intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia, the majority of whom lived in nursing homes (Catic et al., 2013). A key part of the intervention included postdischarge support and contact with the primary care provider. However, this pilot study was not adequately powered to generalize results. Gerrard at al. (2011) also showed that in the United Kingdom, continuing care until death in the preferred place is achievable when patients are asked about their preferences, although preferred place of care and death is subject to change over time as an illness progresses.

Care continuity for nursing home residents was also reported by a research team in Germany (Kötzsch et al., 2014). Patients discharged to nursing homes had the most stable care trajectory, second only to those in hospice care. Almost half of the discharged patients in the entire sample were followed by a specialized outpatient palliative care team. Australian palliative care nurse consultants reported good continuity of care when they were able to participate in the discharge planning process, provide clear information to the postacute care setting about the hospitalization, and follow up after discharge (Blackford & Street, 2001).

Survival

Authors of seven reports included survival after palliative care consult as an outcome. Overall, survival in the nursing home after palliative care during hospitalization is poor. Researchers in Germany and the United States were unique in that they reported survival with different models of palliative care services available in the nursing facility (Catic et al., 2013; Kötzsch et al., 2014). The researchers of the other five articles only reported survival after hospital discharge; it is unknown if and how palliative care was delivered to those patients in nursing homes.

Several U.S. research teams have investigated the outcomes of palliative care on discharge disposition and survival. When separating out patients who died within 30 days of a palliative care consult and hospital discharge, Brody et al. (2010) reported that 42.0% of those who died were discharged to a nursing facility. Of those who died one to three months after palliative care consult and discharge, 20% were discharged to a nursing facility. While the reported rates of death are statistically significantly lower than those not receiving palliative care, the findings highlight the likelihood that patients are near death at hospital discharge. Another U.S.-based research team reported that at six months after palliative care consult and hospital discharge, 24.0% of all deaths occurred in a nursing facility (Fromme et al., 2006). In comparison, 33% of the sample was discharged to inpatient hospice and 37% to a personal home, with the majority having hospice support.

Kötzsch et al. (2014) reported that posthospital survival was lowest (39.8 days) for patients discharged to nursing homes who received palliative care during and after hospitalization as compared with all patients (51.7 days). It is unclear how palliative care services were organized and delivered and how many study participants received the services. Of those with palliative care needs in the intensive care unit during hospitalization and discharged to a nursing facility, 40% had died at six months (Baldwin et al., 2013).

In a study to ascertain outcomes of patients who received inpatient palliative care, Fromme et al. (2006) noted several categories of patients that could be identified based on life expectancy. Of the 70 patients who died 1–14 days after discharge, close to 20% were in a nursing home; of the 59 patients who died 15 days to 6 months after discharge, 30% were in a nursing home. Based on their findings, the authors suggested that assigning life expectancy categories can lead to more efficient discharge planning: (a) if the patient will die in the hospital, (b) if the patient will die within two weeks of hospitalization, (c) if the patient will die within six months of hospitalization, and (d) if the patient has an unknown life expectancy but has a symptom burden

Discussion

Symptoms such as pain and dyspnea can be challenging to manage and may cause fear and anxiety for patients and family caregivers. Most concerning in this review is that despite having access to medical and nursing staff in nursing facilities, patients and families still feel symptoms may not be adequately managed. Pain and other symptoms may be related to a patient’s spiritual and psychosocial issues at end of life in addition to the physical experience (e.g., total pain). Some researchers reported that nursing home staff lacked skill in end-of-life care and therefore could have difficulty assessing and managing complex symptoms (Unroe, Cagle, Lane, Callahan, & Miller, 2015). Cognitive impairment inhibits verbal and nonverbal assessment of nursing home residents’ pain, and nurses may feel unsure about analgesic safety and use (Burns & McIlfatrick, 2015; Monroe, Carter, Feldt, Tolley, & Cowan, 2012). It is unclear how symptoms are being managed after hospitalization for these patients. For this reason, additional in-depth systematic study of symptom management, psychosocial support for anxiety and depression, and spiritual care in the nursing facility setting is needed.

Communication is the cornerstone of palliative care. This review demonstrates that advance-care planning conversations (about prognosis, goals, and care preferences) and the logistics of when and how to contact palliative care specialists are important for nurses, patients, and family caregivers alike. Discussions about prognosis need to be clear and concise to help patients and family caregivers decide if a nursing facility is the best place after hospitalization to care for patients with serious or life-limiting illness. Extensive and complete discharge planning with postdischarge support of palliative care patients is needed to maintain care continuity (King et al., 2013) and reduce rehospitalization when symptoms worsen, new symptoms develop, or goals of care change (Meier & Beresford, 2008).

Advance-care planning conversations lead to better outcomes and high-quality care that is consistent with the patient’s and family’s goals (Bernacki & Block, 2014). None of the research in this synthesis describes how well palliative care teams match expressed goals of care and actual care delivery in a comprehensive manner. Only one team implementing a quality improvement project reported patient preferred place of care and death; they were limited to reporting outcomes that were not scientifically investigated (Gerrard et al., 2011).

Additional topics around communication, care continuity, and rehospitalization worthy of investigation include the following: What is the continuity of patients’ palliative plan of care from the hospital to the nursing facility? How do patients perceive care delivery after goals are elicited? What causes palliative care patient readmission, and how can rehospitalization be limited to those that are concordant with patient and family care preferences? What community-based palliative care services are available for nursing facility residents?

It is concerning that when compared to those discharged to personal homes, some researchers report higher mortality for those discharged to nursing facilities. This finding may be because patients who are discharged to nursing facilities are relatively sicker and may be closer to death than those discharged to personal homes. Patients are often admitted to nursing facilities for nursing and rehabilitative care to improve or stabilize their overall condition. In this context, patients’ and family caregivers’ confusion may grow about goals of care in serious life-threatening illness when improvement is not realistic. The barriers to providing palliative care in U.S. nursing homes have been widely documented. These challenges include regulatory and economic issues (specifically reimbursement policy), staff education and training, the facility culture, and lack of administrative support and leadership (Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2008). Because of these challenges, additional research is needed to determine how well nursing facilities are able to implement hospital palliative care recommendations into nursing and rehabilitative care. Remaining questions include the following: How are hospital palliative care teams and nursing facilities aligning goals with care? How do patients and/or families perceive adherence to goals of care after hospital discharge with a palliative care consult?

Implications for Future Research

The majority of the reviewed studies were descriptive, observational, and exploratory. One experimental randomized controlled trial looked primarily at costs after discharge and did not separate outcomes of patients discharged to nursing facilities. Authors who used cross-sectional retrospective designs on large administrative databases reported findings limited to survival and likelihood of hospice admission. A strength of this reviewed literature is that several researchers focused on in-depth individual experiences. Comprehensive study of personal perspectives, through interviews, medical record reviews, and longitudinal designs, allowed for reporting person-focused outcomes—in one instance, up to one year after a palliative care consult.

Synthesizing a body of literature of palliative care and nursing facility research conducted in different countries using various methods is challenging. The first major issue encountered while analyzing this research was that inpatient and outpatient palliative care are defined, managed, and delivered differently internationally. For example, health care professionals in Norway follow formal recommendations for generalist palliative care, specialist palliative care, and a palliative care “approach” in primary care. For the most part, palliative care is widely available, community-based care that is delivered in the home environment (Thon Aamodt et al., 2013). The second factor was that nursing homes do not deliver palliative care uniformly from country to country. In Germany, palliative care is considered a health care right, and palliative care principles are integrated into nursing homes, where patients are expected to live until they die (Kötzsch et al., 2014). The findings of international literature are of limited use in the United States because of different reimbursement structures and health care systems and palliative care is not defined, operationalized, or paid for in the same way.

Gleaning knowledge from international research can shape the development and advancement of palliative care research in the United States. For example, in the international literature, there was less emphasis on studying survival. Instead, teams focused on studying care continuity (Kötzsch et al., 2014), clinician perceptions (Blackford & Street, 2001; Thon Aamodt et al., 2013), and patient preferences (Gerrard et al., 2011).

Two implications of this review include a need for studying how well pain and symptoms are managed and how promptly prognoses and goals of care are readdressed after hospital discharge. Longitudinal systematic study of how well palliative care teams are able to match a patient’s care to his or her care preferences is needed. Prospective person-level narratives or case studies of individual preferences and care follow-through would allow for a better understanding of these outcomes.

For health care providers, a better understanding of the benefits of clear, concise communication during discharge planning is needed. One approach id for clinicians to consider a patient’s symptom burden and functional status (e.g., ability to carry out daily living activities) as a predictor of survival and integrate this information into discussions when planning for hospital discharge and continued care.

Conclusion

There is no available systematic study on how palliative care teams are managing posthospital transitions and care for patients discharged to nursing facilities. The findings of this review demonstrate a deficiency in understanding the posthospital experience after a palliative care consult. The literature does not describe integration and follow-through of palliative care after hospitalization, including whether recommendations are implemented and followed in the postacute care setting. Multiple studies have shown that palliative care improves care satisfaction during hospitalization and does not reduce survival when compared to a patient receiving usual care. Empirical study of palliative care in nursing homes after hospitalization is needed to determine whether similar outcomes are attainable.

References

- Baldwin MR, Wunsch H, Reyfman PA, Narain WR, Blinderman CD, Schluger NW, … Bach P. High burden of palliative needs among older intensive care unit survivors transferred to post-acute care facilities. a single-center study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013;10(5):458–465. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201303-039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzar E, Hansen L, Kneitel AW, Fromme EK. Discharge planning for palliative care patients: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2011;14(1):65–69. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackford J, Street A. The role of the palliative care nurse consultant in promoting continuity of end-of-life care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2001;7(6):273–278. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.6.9024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AA, Ciemins E, Newman J, Harrington C. The effects of an inpatient palliative care team on discharge disposition. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(5):541–548. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M, McIlfatrick S. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards pain assessment for people with dementia in a nursing home setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2015;21(10):479–487. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.10.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel JB, Webb-Wright J, Holmes J, Lyckholm L, Smith TJ. Clinical and financial impact of a palliative care program at a small rural hospital. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(11):1339–1343. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catic AG, Berg AI, Moran JA, Knopp JR, Givens JL, Kiely DK, … Mitchell SL. Preliminary data from an advanced dementia consult service: Integrating research, education, and clinical expertise. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(11):2008–2012. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. Improving Palliative Care in Nursing Homes. New York: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. National Palliative Care Registry 2012 Annual Survey Summary. 2014 Retrieved from https://registry.capc.org/cms/portals/1/Reports/Registry_Summary%20Report_2014.pdf.

- Chand P, Gabriel T, Wallace CL, Nelson CM. Inpatient palliative care consultation: Describing patient satisfaction. Permanente Journal. 2013;17(1):53–55. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciemins EL, Blum L, Nunley M, Lasher A, Newman JM. The economic and clinical impact of an inpatient palliative care consultation service: A multifaceted approach. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;10(6):1347–1355. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan JD. Hospital charges for a community inpatient palliative care program. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 2004;21(3):177–190. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The Growth of Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals: A Status Report. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2016;19(1):8–15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(12):1356–1361. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme EK, Bascom PB, Smith MD, Tolle SW, Hanson L, Hickam DH, Osborne ML. Survival, mortality, and location of death for patients seen by a hospital-based palliative care team. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(4):903–911. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, … Penna RD. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(2):180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard R, Campbell J, Minton O, Moback B, Skinner C, McGowan C, Stone PC. Achieving the preferred place of care for hospitalized patients at the end of life. Palliative Medicine. 2011;25(4):333–336. doi: 10.1177/0269216310387459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LC, Usher B, Spragens L, Bernard S. Clinical and economic impact of palliative care consultation. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2008;35(4):340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicince. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJH. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(7):1095–1102. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kötzsch F, Stiel S, Heckel M, Ostgathe C, Klein C. Care trajectories and survival after discharge from specialized inpatient palliative care: Results from an observational follow-up study. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2015;23(3):627–634. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2393-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi PL, Morrison RS, Morris J, Goldhirsch SL, Carter JM, Meier DE. Palliative care consultations: How do they impact the care of hospitalized patients? Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2000;20(3):166–173. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May P, Normand C, Morrison RS. Economic impact of hospital inpatient palliative care consultation: Review of current evidence and directions for future research. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014;17(9):1054–1063. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier DE, Beresford L. Palliative care’s challenge: Facilitating transitions of care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(3):416–421. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe T, Carter M, Feldt K, Tolley B, Cowan R. Assessing advanced cancer pain in older adults with dementia at the end-of-life. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(9):2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 3. Pittsburgh, PA: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DG, Bramson JS. Hospice care in the nursing home setting: A review of the literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;38(3):440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman K, Greenwald R, Reidenouer A, Pantel L. Living with advanced illness: Longitudinal study of patient, family, and caregiver needs. Permanente Journal. 2012;16(3):28–35. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon Aamodt IM, Lie I, Helleso R. Nurses’ perspectives on the discharge of cancer patients with palliative care needs from a gastroenterology ward. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2013;19(8):396–402. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.8.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unroe KT, Cagle JG, Lane KA, Callahan CM, Miller SC. Nursing home staff palliative care knowledge and practices: Results of a large survey of frontline workers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015;50(5):622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/en/