Abstract

This study represents the first attempt to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which nitrate, an anion of significant ecological, agricultural, and medical importance, is transported into cells by high-affinity nitrate transporters. Two charged residues, R87 and R368, located within hydrophobic transmembrane domains 2 and 8, respectively, are conserved in all 52 high-affinity nitrate transporters sequenced thus far. Site-directed replacements of either of R87 or R368 residues by lysine were found to be tolerated, but such residue changes increased the Km for nitrate influx from micromolar to millimolar values. Seven other amino acid substitutions of R87 or R368 all led to loss of function and lack of growth on nitrate. No evidence was obtained of R87 or R368 forming a salt-bridge with conserved acidic residues. Remarkably, the phenotype of loss-of-function mutant R87T was found to be alleviated by an alteration to lysine of N459, present in the second copy of the nitrate signature (transmembrane domain 11), suggesting a structural or functional interplay between residues R87 and N459 in the three-dimensional NrtA protein structure. Failure of the potential reciprocal second site suppressor N168K (in the first nitrate signature copy of transmembrane domain 5) to revert R368T was observed. Taken with recent structural studies of other major facilitator superfamily proteins, the results suggest that R87 and R368 are involved in substrate binding and probably located in a region of the protein close to N459.

Keywords: anion transport, membrane protein, nitrate permease, transmembrane domain

Nitrate is a major source of nitrogen for crop plants and it is the nutrient that most frequently limits their growth (reviewed in refs. 1–3). In the natural environment, nitrate is the most ephemeral of inorganic nutrients, with concentrations varying by as much as 5 orders of magnitude (4). Nitrate is readily leached from soils, contributing to eutrophication of natural water systems and simultaneously lowering nitrogen availability to land plants. In addition, nitrogen-based fertilizers, widely used at around 1011 kg per annum globally to sustain current high crop yields, cost roughly $50 billion (U.S.) (5). There are also health concerns because nitrogen oxides derived from nitrate may be generated in the human gut (6). The first step in the assimilation of nitrate to ammonium, involves the influx of nitrate into cells, an active process that may require up to 25 kJ·mol–1, depending on external nitrate concentration (4). Regulation of nitrate uptake includes induction by nitrate and feedback repression thought to be due to glutamine, which is overlaid by both spatial and developmental control (4, 7). Indeed, certain plant metabolic and morphogenic processes are controlled by nitrate (8, 9).

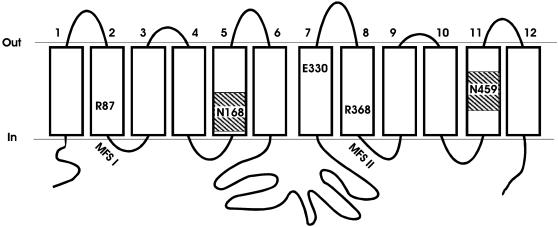

Two classes of nitrate transport systems, high- and low-affinity, have been identified (5, 10, 11). The Aspergillus nidulans nrtA, formerly crnA (12), gene encodes a membrane protein, TC 2.A.1.8.5, that belongs to the family of high-affinity nitrate transporters (10, 13–15). This gene was the first encoding a eukaryotic high-affinity nitrate transporter to be isolated (14) and has acted as a paradigm for plant high-affinity systems, leading to the cloning and identity of orthologous genes from a number of species (10, 16–20). A secondary structure model (Fig. 1) was proposed for the 57-kDa (507 aa) NrtA protein in which 12 hydrophobic transmembrane domains (Tms) in α-helical conformation pass through the membrane connected by hydrophilic loops, although caution must be exercised as to the precise locations of the Tms (10, 14). The NrtA homologues belong to a distinct cluster of the largest secondary transporter family known, the major facilitator superfamily (MFS; TC 2.A.1), which comprises a vast range of functionally diverse transporters (21–23), each containing motifs characteristic of the superfamily (Fig. 1, positions marked by MFS). Recently, the three-dimensional structures of three MFS members have been determined: the oxalate (TC 2.A.1.11.1) (24) and glycerol-3-phosphate (TC 2.A.1.4.3) (25) transporters and lactose permease (LacY; TC 2.A.1.5.1) (26).

Fig. 1.

Simplified secondary structure model of the high-affinity nitrate transporter NtrA of A. nidulans. Positions of residues R87, N168, E330, R368, and N459 are shown, with the two MFS motifs indicated and the two nitrate signatures marked by hatched boxes.

There are a number of very highly conserved residues within the high-affinity nitrate transporter subfamily of the nitrate/nitrite porter family, TC 2.A.1.8, with at least 95% conservation in 52 proteins from archaebacteria, eubacteria, fungi, algae, and plants (refs. 10 and 13 and D.A.R., unpublished data). Some of these amino acids are found within a motif present in all nitrate transporters, F/Y/K-x3-I/L/Q/R/K-x-G/A-x-V/A/S/K-x-G/A/S/N-L/I/V/F/Q-x1,2-G-x-G-N/I/M-x-G-G/V/T/A (Fig. 1, hatched boxes), which is not observed in any other classes of MFS proteins (10). This residue stretch has been referred to as the nitrate signature that has two copies within NrtA located in Tm-5 and Tm-11. The first copy contains a highly conserved (48/52) polar N168 residue, whereas the second (N459) is conserved in eukaryotes. Also prominent are two charged polar arginine residues, R87 and R368, that are completely conserved in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes within hydrophobic helices Tm-2 and Tm-8, respectively, being located close to the N termini of the two MFS motifs present in NrtA. The MFS motifs may be important in promoting global conformational changes associated with transport in MFS members (27). Toward gaining an understanding of the importance of residues R87 and R368 and their role in the structure and function of this important anion transporter, we have altered these amino acids and characterized the resulting mutant strains by using the short-lived tracer  .

.

Experimental Procedures

Escherichia coli Strains, Plasmids, and Media. Standard procedures were used for the propagation of plasmids and for subcloning and maintenance of plasmids within E. coli strain DH5α.

Molecular Methods and Amino Acid Replacement Constructs. DNA was isolated by using a Nucleon BACC2 Kit (Amersham Pharmacia) and RNA by using an RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Crawley, U.K.). The conditions used during Southern analysis were as described in ref. 28. Nucleotide sequencing was determined by automated sequence analysis as described in ref. 28. The generation of mutations was by PCR overlap extension (29). Details of the primers used for mutagenesis as well as those for amplification of wild-type and mutant copies of nrtA can be obtained from the authors. For immunological detection, a sequence encoding the V5 epitope was fused to the 3′ end of the nrtA coding region (S.E.U., unpublished data).

A. nidulans Methodology. Routine Aspergillus growth media and handling techniques were as described in ref. 30. Shake flask cultures for nitrate uptake were grown in liquid minimal medium (31) (as modified in ref. 15). Gene transformation methods used in this report are reviewed in ref. 32 and references therein. Initially, strain JK900 was used as the recipient in transformation experiments. JK900 is a double mutant harboring loss-of-function mutations (nrtA747 and nrtB110) in both nitrate transporter genes, nrtA and nrtB, and consequently completely fails to grow on 10 mM nitrate in the medium (15). Such lack of growth allows the direct selection of nitrate-utilizing strains when transformed with NrtA residue replacement constructs after 3 days of incubation at 37°C on agar minimal medium with nitrate as the sole source of nitrogen at the routinely used concentration of 10 mM. Although direct selection provides a rapid qualitative estimate of the effect of a mutation, no control over integration locus or copy number is possible with this transformation strategy. Transformation of JK900 was carried out at least twice for each mutant construct.

An indirect selection strategy was then adopted to obtain single or at least lower copy integration of nrtA constructs targeted to the argB locus by conventional techniques (ref. 32 and references therein) with strain JK1060, which is a triple mutant carrying nrtA747 and nrtB110 mutations and additionally harboring argB2, a marker that allows the independent selection of transformants on the basis of selection for the repair of arginine auxotrophy on agar minimal medium with 5 mM ammonium tartrate as the sole nitrogen source. Such arginine prototrophs are screened for nitrate utilization on agar minimal medium with 10 mM nitrate as a sole source of nitrogen (15). Although obtaining single-copy transformant strains is more time-consuming than those directly selected, given that their identification requires Southern analysis, they are stable. Also, because all of the constructs are integrated at the same location (33), these strains can be used for quantitative and comparative assessment of the effect of residue changes.

Intragenic Suppression of R87T and R386T Mutants. Mutations R87T and R368T were generated after changes of two and three base pairs, respectively, resulting in mutant nrtA alleles that are unlikely to revert to wild type. Transformants containing single-copy integrations of these constructs located at the argB locus were identified by Southern analysis. The coding region of such single-copy R87T or R368T transformants was amplified by using primers specific for the construct copy of nrtA and sequenced to verify the presence of the mutation. These strains were treated with the chemical mutagen, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (34), after which spores were plated out on agar minimal medium containing 10 mM nitrate as the sole nitrogen source. This approach takes advantage of the fact that phenotypic reversion is easy to observe because neither R87T nor R386T mutant strains are capable of growth on 10 mM nitrate (see Fig. 2, R87T T1). Representative nitrate-utilizing revertant strains were selected and purified, and their complete nrtA coding region was sequenced. Confirmation of intragenic suppression results was obtained by repeating experiments while using an in vitro mutagenesis approach as described above.

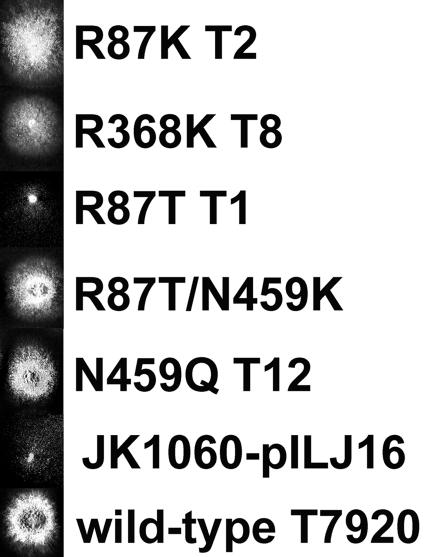

Fig. 2.

Growth tests of single-copy nrtA gene transformants. Shown are representative single colonies of arginine prototrophic transformants of JK1060 grown on minimal medium containing 10 mM nitrate as the sole nitrogen source. Transformant strains R87K T2, R368K T8, and N168Q T12, each possess a single nrtA mutant copy located at argB. Transformant JK1060-pILJ16 (a vector that contains the argB gene only) is used as the control for the base level of growth on nitrate. Transformant T7920 is a single-copy integration at argB of the wild-type coding region in pMUT (containing the wild-type nrtA gene) and was included as a control for wild-type growth. R87T/N459K is the intragenic suppressor mutant generated by chemical mutagenesis of a single-copy R87T T1 strain.

Nitrate Influx Assays. Synthesis of  tracer and the influx assay method have been described before (15, 35, 36). Values for influx are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of dry weight per hour. Influx assays were repeated at least three times, and the values shown in Table 1 are from a single representative experiment.

tracer and the influx assay method have been described before (15, 35, 36). Values for influx are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of dry weight per hour. Influx assays were repeated at least three times, and the values shown in Table 1 are from a single representative experiment.

Table 1. Kinetic constants for  influx of NrtA amino acid replacement mutants.

influx of NrtA amino acid replacement mutants.

| Residue alteration | Km | Vmax |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type T7920 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 1,116 ± 83.0 |

| R87K T2 | 3.36 ± 0.2 | 297 ± 11 |

| R368K T8 | 36.9 ± 5.9 | 376 ± 40 |

| N459Q T12 | 0.163 ± 0.026 | 1,294 ± 145 |

| R87T/N459K | 49.6 ± 4.1 | 1,886 ± 99 |

Strains were grown for 6 h in media containing 2.5 mM urea as the sole nitrogen source and exposed to 10 mM NO3- for 100 min prior to influx measurements. Km (mM) and Vmax (nmol per mg of dry weight per h) values were determined by computer by using direct fits of data to rectangular hyperbolae. Wild-type refers to a transformant in which a single copy of the wild-type nrtA gene has been integrated at the argB locus. The R87T/N459K strain was generated by chemical mutagenesis.

Protein Analysis. Crude membrane preparations were made as described in ref. 37. Protein was assayed with a BCA kit (Pierce) by using BSA as standard. Equal amounts (50 μg) of protein were subjected to 10% SDS/PAGE, and immunological detection was performed by using anti-V5-horseradish peroxidase antibody (Invitrogen) against engineered C-terminal V5 epitope (S.E.U., unpublished data).

Results

R87 Residue Replacement. Direct selection of transformants of strain JK900 on 10 mM nitrate medium with plasmid constructs in which R87 had been replaced with less bulky, positively charged lysine showed growth similar to the wild-type construct. In contrast, constructs with R87 altered to asparagine, cysteine, histidine, isoleucine, glutamate, glutamine, or threonine residues failed to permit growth of transformants significantly above host strain background. Strains obtained by indirect selection harboring single gene copies integrated at the argB locus with residue change R87K yielded nitrate-utilizing transformants (e.g., R87K T2) (Fig. 2), confirming the result from direct selection of transformants. Such R87K transformants grew slightly less well than wild type but markedly better than R87T or an arginine prototrophic transformant (JK1060-pILJ16) of the recipient strain. Residual growth of strains similar to that shown in Fig. 2, such as R87T and JK1060-pILJ16, was observed also on agar minimal medium without a nitrogen source and is probably due to modest reserve nitrogen availability within conidia or to a very limited level of a nitrogen source(s) being present in the minimal medium. This phenotype is typical of Aspergillus nitrogen-starved growth. Single-copy transformant R87K T2 was used for kinetic analysis.

R368 Residue Replacement. Good growth of transformed strains harboring the construct in which R368 was replaced by lysine were obtained by direct selection on nitrate, although such transformants grew slightly less vigorously than directly selected R87K strains. Alteration of R368 to asparagine, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, histidine, isoleucine, or threonine did not permit growth on 10 mM nitrate. R368K T8, the single-copy transformant from indirect selection with JK1060 by using construct R368K, was observed to grow after screening on nitrate (Fig. 2), which supports the results from direct selection; i.e., R368K T8 grows but less well than transformant R87K T2.

Investigation of a Potential Salt-Bridge Partner for Residue R87 or R368. The glutamate residue E330 located in Tm-7 (Fig. 1) is conserved in all eukaryotic nitrate transporters. Replacement of E330 by aspartate was tolerated, whereas replacement by arginine, cysteine, isoleucine, or glutamine was not. Therefore, the observation that E330 seemed to be successfully replaced only by a negatively charged residue (aspartate) and R87 and R368 by a positively charged residue (lysine), raised the possibility that neutralization of these charges located within the transmembrane domains may occur by means of a salt-bridge formation between R87 or R368 and E330. To investigate this, a second-site mutation of E330Q was introduced in the R87T construct by site-directed mutagenesis, producing a mutant protein in which both the charged residues were replaced by uncharged residues. Likewise, second-site mutation E330R was introduced into the R87E background, “reversing” the charge positions. After these constructs were transformed into JK900, growth of transformants was not observed, which showed that neither (i) removal of both charges at positions 87 and 330 to give uncharged R87T/E330Q nor (ii) interchanging of charges as in R87E/E330R could restore growth. A similar result was observed for E330 and R368 combinations.

Intragenic Suppression of R87T and R368T Mutant Strains. To probe the local structural environments of the two conserved arginine positions, we selected possible second-site revertants after chemical mutagenesis that restored growth of R87T and R368T mutant strains on 10 mM nitrate as the sole nitrogen source. One phenotypic revertant of transformed strain R87T T1 (see Fig. 2 and Experimental Procedures) was found to carry the suppressor mutation in codon 459 (AAC to AAA), resulting in the replacement of asparagine with lysine, the revertant (i.e., R87T/N459K) showing appreciable growth on nitrate (Fig. 2). Residue N459 is located within the second copy of the nitrate signature in Tm-11 (Fig. 1). However, to circumvent the unlikely possibility that two second-site mutations had taken place concomitantly, i.e., intragenic N459K and an intergenic unknown mutation acting as the true suppressor of R87T, a site-directed mutagenesis strategy was adopted to alter N459 to lysine in the R87T construct. The resulting nrtA double-mutant transformant harboring the R87T/N459K construct, generated by in vitro mutagenesis, grew well on nitrate, confirming the validity of the original chemical mutagenesis result. This line of inquiry was pursued to determine whether R87T was suppressed by change of N459 to another polar basic residue, i.e., arginine (instead of lysine). No growth was observed with an R87T/N459R construct. Neither was growth sustained by the arrangement reciprocal to wild type, i.e., R87N/N459R. However, growth was restored in a double mutant of R87N in combination with N459K.

Whereas several phenotypic revertants of transformed strain R368T T5 using chemical mutagenesis were observed, none of five sequenced was found to have alterations within the nrtA gene (apart from one revertant for which the nucleotide alteration ACG to AGG resulted in the return of arginine at position 368, albeit with a different codon). Because of the significant bi-fold symmetry exhibited in the sequence of the transporter, we had predicted that the alteration equivalent to N459K would be N168 to lysine (N168 being located in the first nitrate signature of Tm-5) (Fig. 1) and that this might similarly suppress the loss-of-function R368T phenotype. Consequently, to circumvent the possibility of insufficient revertants having been sequenced, a site-directed mutagenesis strategy was pursued to alter N168 to lysine in the R368T construct. This possible counterpart of the N459K suppressor of R87T (i.e., R368T/N168K), however, failed to yield transformants by direct selection on nitrate. Moreover, a transformant selected by indirect means on the basis of arginine prototrophy and shown by Southern blot and PCR amplification followed by DNA sequence analysis to contain a single copy of the R368T/N168K allele (S.E.U., unpublished data) was likewise unable to grow on nitrate. Finally, R368N/N168R transformants also failed to grow on nitrate.

N168 or N459 Replacements. Because the suppressor studies had highlighted the importance of N459 in the second nitrate signature, further site-directed mutagenesis investigations of this residue and its counterpart, N168, in the first nitrate signature were undertaken. N459 was altered to arginine, cysteine, glutamine, or lysine. Only the glutamine replacement construct yielded transformants with significant growth on nitrate. The single-copy transformant from indirect selection with JK1060 by using construct N459Q, N459Q T12, was observed to grow on nitrate after screening (Fig. 2), confirming the results from direct selection. Finally, it was noted that lysine was unable to substitute N459 in the wild-type R87 background, in contrast to a R87T or R87N background.

Such studies showed that N168K (or N168R) failed to suppress R368T. Consequently, the requirement for N168 was examined by alteration to arginine, cysteine, or glutamine in an otherwise wild-type NrtA. None of these changes yielded transformants with significant growth on nitrate.

Characterization of Nitrate Uptake in Residue Replacement Strains by Using Tracer  . Nitrate influx was measured by using the short-lived isotope 13N (t0.5 = 10 min) at the lower

. Nitrate influx was measured by using the short-lived isotope 13N (t0.5 = 10 min) at the lower  concentration range (up to 250 μM, the typical concentration range of a high-affinity transporter) and at the higher concentration range of low-affinity transporters (up to 100 mM). The Km value for NrtA in the wild-type transformant T7920 was found to be 0.13 mM, whereas the Vmax value was 1,116 nmol per mg of dry weight per h in young mycelium (Table 1). Single-copy strains of R87K and R368K that showed tangible growth on nitrate were analyzed. NrtA in strain R87K T2 was found to have a Km value of 3.36 mM, ≈30-fold that of the wild-type T7920 (Table 1). The Km for the nitrate of the R368K T8 mutant protein was 36.9 mM, almost 300-fold higher than the wild-type NrtA of strain T7920 (Table 1). Similar to R87 and R368 alterations, NrtA in the double-mutant strain R87T/N459K showed a much reduced affinity for nitrate. In contrast, studies of the N459Q mutant showed no significant difference in Km or Vmax compared with wild type (Table 1), demonstrating that change per se within a Tm does not necessarily result in aberrant kinetic properties. Finally, whereas R87K T2 and R368K T8 Vmax values for NrtA were less than the wild-type value, the Vmax value for the R87T/N459K mutant protein was higher than that of the wild-type value (Table 1).

concentration range (up to 250 μM, the typical concentration range of a high-affinity transporter) and at the higher concentration range of low-affinity transporters (up to 100 mM). The Km value for NrtA in the wild-type transformant T7920 was found to be 0.13 mM, whereas the Vmax value was 1,116 nmol per mg of dry weight per h in young mycelium (Table 1). Single-copy strains of R87K and R368K that showed tangible growth on nitrate were analyzed. NrtA in strain R87K T2 was found to have a Km value of 3.36 mM, ≈30-fold that of the wild-type T7920 (Table 1). The Km for the nitrate of the R368K T8 mutant protein was 36.9 mM, almost 300-fold higher than the wild-type NrtA of strain T7920 (Table 1). Similar to R87 and R368 alterations, NrtA in the double-mutant strain R87T/N459K showed a much reduced affinity for nitrate. In contrast, studies of the N459Q mutant showed no significant difference in Km or Vmax compared with wild type (Table 1), demonstrating that change per se within a Tm does not necessarily result in aberrant kinetic properties. Finally, whereas R87K T2 and R368K T8 Vmax values for NrtA were less than the wild-type value, the Vmax value for the R87T/N459K mutant protein was higher than that of the wild-type value (Table 1).

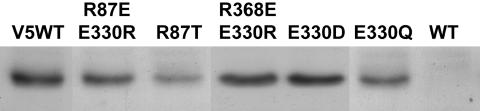

Expression of Mutant NrtA Protein. Protein expression in single-copy transformants was compared with that of a transformant containing the wild-type construct with the C-terminal V5 epitope tag, designated V5WT (Fig. 3). Protein levels similar to V5WT were observed with all single-copy transformants, including changes of R87 to threonine (Fig. 3), lysine, cysteine, isoleucine, glutamate, and glutamine (unpublished data); R368 to lysine, isoleucine, and glutamine (unpublished data); E330 to aspartate and glutamine (Fig. 3); and double mutants R87T/N459K, R368T/N168K, R368T/E330Q (unpublished data) R87E/E330R, and R368E/E330R (Fig. 3). That no protein was detected with the anti-V5 antibody in a membrane preparation from a transformant containing a single copy of the wild-type construct without the V5 epitope, designated WT, demonstrated antibody specificity (Fig. 3). Reduction or loss of nitrate transport activity is not, therefore, due to lack of expression of the mutant NrtA protein in these strains.

Fig. 3.

Expression of NrtA. Approximately 50 μg of protein from membrane fractions of strains carrying single copies of the V5-tagged constructs was subjected to 10% SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis by using anti-V5-horseradish peroxidase monoclonal antibody. V5WT refers to the wild-type NrtA construct with a C-terminal V5 epitope tag, and WT refers to the wild-type construct without the V5 tag. Mutant constructs are indicated above the respective lanes. Immunoblot data for mutants not shown can be viewed upon request. Details of mutant strains are given for Fig. 2 or in the text.

Discussion

This study represents an attempt to address structure/function relationships in a high-affinity nitrate transporter. Initially, we sought to determine the essentiality of two charged residues, R87 and R368, that are conserved in hydrophobic domains Tm-2 and Tm-8, respectively, of all high-affinity nitrate transporters sequenced thus far, from archaebacterial and eubacterial prokaryote groups to fungal and plant eukaryotic kingdoms. Second, we examined whether salt bridges might be formed between positively charged basic residues (R87 or R368) and a conserved negatively charged residue (E330) located in Tm-7. Third, following evidence from second-site reversion, we extended our studies to investigate the effects of substitutions of the conserved polar uncharged residues, N168 and N459, present in copies 1 (Tm-5) and 2 (Tm-11) of the nitrate signature (Fig. 1), respectively, in R87 and R368 mutant backgrounds.

The two arginine residues were altered to a variety of amino acids representing differences in charge, hydrophobicity, and side-chain bulk. Analysis of transformant strains containing such site-directed mutations has shown that R87 and R368 are important, but not mandatory, for nitrate influx. Residue substitution of either arginine residue to nonbasic residues, even those with a fairly bulky side chain, like glutamine, leading to loss of the positive charge, resulted in NrtA loss of function. In contrast, changes of R87 or R368 to lysine permitted appreciable, although not wild-type, growth. Moreover, kinetic measurements of the nitrate transporter in R87K and R368K single-copy mutants revealed Km values increased by 30- and 300-fold, respectively, compared with wild-type values, indicating substantially reduced affinity for nitrate. Lysine has a charge similar to arginine, which suggests that positions 87 and 368 require a positive charge, whereas the slightly shorter side chain and significantly smaller head group of lysine could account for the large reduction in affinity for nitrate. The reason that histidine could not functionally replace either arginine may be that the local microenvironment is such that the imidazole group is uncharged. Together with the perfect conservation of the two arginine residues and the very limited number of permitted substitutions, the dramatic effect on Km in arginine-to-lysine mutants suggests that these arginine residues interact directly with the substrate nitrate, most likely forming part of the substrate binding site.

Because mid-Tm charges, such as R87 and R368, are thermodynamically unfavorable, the existence of potential chargestabilizing salt bridges to neutralize these basic residues was investigated. In the lactose permease, mutation of one residue of an ion pair can result in much reduced lactose transport. However, a characteristic of salt bridges is that substitution of both acidic and basic amino acid partners, either by noncharged amino acids or by interchange of charged residues, can restore activity (38–41). Within or at the borders of the proposed Tms of NrtA there are several negatively charged residues. However, a number of these, namely D152, D183, D220, D408, E414 and E429, are conserved in four or fewer of the 52 different nitrate transporters and are therefore considered to be unlikely candidates for interaction with such conserved arginine residues as R87 and R368. In contrast, two well conserved aspartate residues, D95 and D376, are found in the MFS motifs of loop 2/3 and 8/9, respectively. Because these motifs are present in MFS families whose members recognize very different substrates, it would seem that these also are unlikely salt-bridge partners for arginine residues conserved only in nitrate transporters. Of the remaining two possibilities, conserved D221 can be substituted by the nonacidic residue asparagine without apparent impairment of growth on nitrate (S.E.U., unpublished data). If this residue were the partner of R87 or R368, such loss of negative charge would be expected to lead to detrimental effects on NrtA protein structure or function. However, compensation (as a salt-bridge partner) by another nearby negatively charged residue, although unlikely, cannot be excluded. Finally, residue E330, although not present in the prokaryotes (nor is there an obvious conserved negatively charged counterpart in the prokaryotes), is nevertheless perfectly conserved in the eukaryotic high-affinity nitrate transporters. Alteration of residue E330 to aspartate was tolerated, whereas neutral amino acid substitutions resulted in loss of function. Moreover, such defects could not be alleviated by a neutral change to either R87 or R368 in double mutants R87T/E330Q or R368T/E330Q. Similarly, charge-exchange double-mutants R87E/E330R or R368E/E330R were unable to grow on nitrate as sole nitrogen source. These observations suggest that salt-bridge formation of E330 with either R87 or R368 is unlikely, a contention perhaps supported by the unequal balance of conserved positive-to-negative Tm-located charges (2:1) and the absence of a counterpart to E330 in the prokaryotes. As a caveat to this conclusion, however, it should be noted that the lack of functional restoration in double mutants is not proof of the nonexistence of salt bridges, because such results could also be observed if a positive charge at positions 87 or 368 were essential for substrate interaction. If, however, there are no salt-bridge partners, it may be that nitrate molecules themselves may act as “dynamic” salt bridges as they pass through the transport pore, displacing water molecules neutralizing the positive charges present in the absence of substrate.

Evidence concerning the functional role of residues, such as the interaction of amino acid side chains, separated by linear distance within a protein may be obtained by analyzing secondsite mutations. To gain insight into the function of the R87 and R368, second-site suppressors were sought that would restore the ability to grow on nitrate in the loss-of-function R87T and R368T mutants. A suppressor of R87T that possessed a second mutation of N459 to lysine was obtained, which was remarkable in that (i) N459 is located in the second nitrate signature, a motif well conserved among high-affinity nitrate transporters in Tm-11 and (ii) the replacement involved change of a noncharged residue to a basic amino acid. As described from extensive second-site suppression studies of LacY (42), restoration of transport activity may occur by several means. Broadly, these can occur as (i) structural corrections made as a consequence of the second amino acid alteration either at some distance from the first alteration or in close tertiary structure proximity or (ii) functional compensation of the first change by the second change. The latter could imply close proximity of residues. In the case of NrtA, the observation that the second site suppressor of R87T occurs in a motif highly conserved among nitrate transporters would suggest a functional rather than a purely structural mode of suppression. Also, it is clear from analysis of R87 single mutations that a positive charge is required for nitrate transport and kinetic studies show the R87 residue plays an important role in substrate affinity. Therefore, the change of asparagine to lysine at position 459 would support the notion that this alteration represents functional suppression. Regaining a positive charge in a region accessible to substrate (i.e., at or close to the natural substrate binding site) would allow some transport to resume. The affinity for nitrate in the suppressor strain remains much lower than the wild type and even lower than an R87K single mutant, consistent with the altered location of the charge being suboptimal and lysine being unable to substitute adequately for arginine.

Perhaps surprisingly, the in vitro-generated mutants R87T/N459R or R87N/N459R would not permit growth on nitrate. Instead, activity was only observed with R87T or R87N when N459 was changed to lysine. Replacement with bulky arginine may not be permitted within space constraints at position 459, which the high number of compact glycine residues in the nitrate signature might imply.

The compensation of N459K for R87T or R87N suggests that these residue positions are likely to be within the region of the protein responsible for binding/translocation of the substrate. Compelling supportive evidence for such a location comes from comparison of other MFS protein tertiary structure models for LacY (43, 44), the tetracycline transporter TetA (45), and recently reported, high-resolution, three-dimensional structures of the oxalate transporter (24), the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter (25), and LacY (26). For each of these MFS proteins, the overall arrangement of transmembrane helices, predicted by biochemical and genetic analysis or by structure determination, is the same. Therefore, the general architecture of the 12 Tm members of the superfamily is likely to be similar, representing an ancestral structure from which the individual families within the group have evolved. In this structure, Tm-2 and Tm-11 are close to each other and line one side of the substrate translocation pore, so we predict that R87 and N459 may lie in close proximity, thus having the potential to influence the transport process. However, whereas R87 may appear a good candidate for substrate binding as judged by the marked effects of conservative substitutions on Km values, N459 is less likely in this role because change to glutamine has no significant effect on affinity for nitrate. However, N459 is clearly important for activity either in a structural or functional capacity because no other substitution tested allows substantial growth.

Despite the symmetry obvious from the NrtA secondary structure (Fig. 1) and by extrapolation from the known MFS structures in which Tm-5 and Tm-8 form the opposite side of the translocation pore from Tm-2 and Tm-11, substitutions N168K or N168R in the first nitrate signature of Tm-5 failed to compensate for the change (R368T) in Tm-8. An extensive study of suppression in LacY noted functional asymmetry (42), which may account for this result for NrtA.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of British Columbia Tri-University Meson Facility (TRIUMF) for provision of 13N. This work was supported in part by the Biotechnology and Biology Research Councils of the United Kingdom (J.R.K.), the Dairy Research and Development Corporation of Australia (D.A.R.), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (A.D.M.G.).

Author contributions: S.E.U., D.A.R., A.D.M.G., and J.K. designed research; S.E.U., Y.W., M.Y.S., A.D.M.G., and J.K. performed research; S.E.U., D.A.R., Y.W., M.Y.S., A.D.M.G., and J.K. analyzed data; and S.E.U., A.D.M.G., and J.K. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: MFS, major facilitator superfamily; Tm, transmembrane domain; LacY, lactose permease.

References

- 1.Crawford, N. M. & Glass, A. D. M. (1998) Plant Sci. 3, 389–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniel-Vedele, F., Filleur, S. & Caboche, M. (1998) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 1, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams, L. & Miller, A. (2001) Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 659–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidmar, J. J., Zhuo, D., Siddiqi, M. Y., Schjoerring, J. K., Touraine, B. & Glass, A. D. M. (2000) Plant Physiol. 123, 307–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass, A. D. M. & Siddiqi, M. Y. (1995) in Nitrogen Nutrition in Higher Plants, eds. Srivastava, H. S. & Singh, R. P. (Associated Publishing, New Delhi), pp. 21–56.

- 6.Vermeer, I. T. M. & van Maanen, J. M. S. (2001) Rev. Environ. Health 16, 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forde, B. G. (2002) Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 203–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheible, W. R., Gonzales-Fontes, A., Laurer, M., Muller-Rober, B., Caboche, M. & Stitt, M. (1997) Plant Cell 9, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, H. & Forde, B. G. (1998) Science 279, 407–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trueman, L. J., Richardson, A. & Forde, B. G. (1996) Gene 175, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsay, Y.-F., Schroeder, J. I., Feldmann, K. A. & Crawford, N. M. (1993) Cell 72, 705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownlee, A. G. & Arst, H. N., Jr. (1983) J. Bacteriol. 155, 1138–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forde, B. G. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465, 219–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unkles, S. E., Hawker, K., Grieve, C., Campbell, E. I. & Kinghorn, J. R. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 204–208, and correction (1995) 92, 3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unkles, S. E., Zhou, D., Siddiqi, M. Y., Kinghorn, J. R. & Glass, A. D. M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6246–6255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quesada, A., Galvan, A. & Fernandez, E. (1994) Plant J. 5, 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quesada, A., Krapp, A., Trueman, L. J., Daniel-Vedele, F., Fernandez, E., Forde, B. G. & Caboche, M. (1997) Plant Mol. Biol. 34, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amarasinghe, B. H. R. R., Debruxelles, G. L., Braddon, M., Onyeocha, I., Forde, B. G. & Udvardi, M. K. (1998) Planta 206, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filleur, S., Dorbe, M. F., Cerezo, M., Orsel, M., Granier, F., Gojon, A. & Daniel-Vedele, F. (2001) FEBS Lett. 489, 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou, J. J., Fernandez, E., Galvan, A. & Miller, A. J. (2000) FEBS Lett. 466, 225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith, J. K., Baker, M. E., Rouch, D. A., Page, M. G. P., Skurray, R. A., Paulsen, I. T., Chater, K. F., Baldwin, S. A. & Henderson, P. J. F. (1992) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 4, 684–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pao, S. S., Paulsen, I. T. & Saier, M. H. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marger, M. D. & Saier, M. H. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 18, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirai, T., Heymann, J. A. W., Maloney, P. C. & Subramaniam, S. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 1712–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, Y., Lemieux, M. J., Song, J., Auer, M. & Wang, D.-N. (2003) Science 301, 616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abramson, J., Smirnova, I., Kasho, V., Verner, G., Kaback, H. R. & Iwata, S. (2003) Science 301, 610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pazdernik, N. J., Matzke, E. A., Jessen-Marshall, A. E. & Brooker, R. J. (2000) J. Membr. Biol. 174, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unkles, S. E., Heck, I. S., Appleyard, M. V. C. L. & Kinghorn, J. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19286–19293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warrens, A. N., Jones, M. D. & Lechler, R. I. (1997) Gene 186, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clutterbuck, A. J. (1974) in Handbook of Genetics, ed. King, R. C. (Plenum, New York), Vol. 1, pp. 447–510. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cove, D. J. (1966) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 113, 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riach, M. & Kinghorn, J. R. (1995) in Fungal Genetics, ed. Bos, C. (Wiley, London) pp. 209–234.

- 33.Punt, P. J., Strauss, J., Smit, R., Kinghorn, J. R., van den Hondel, C. A. & Scazzocchio, C. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5688–5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adelberg, E. A., Mandel, M. & Chen, G. C. C. (1965) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 18, 788–795. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siddiqi, M. Y., Glass, A. D. M., Ruth, T. J. & Fernando, M. (1989) Plant Physiol. 90, 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kronzucker, H. J., Siddiqi, M. Y. & Glass, A. D. M. (1995) Planta 196, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unkles, S. E., Wang, R., Wang, Y., Glass, A. D. M., Crawford, N. M. & Kinghorn, J. R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28182–28186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahin-Toth, M., Dunten, R. L., Gonzalez, A. & Kaback, R. H. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 10547–10551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, J.-I., Varela, M. F. & Wilson, T. H. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1278, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson, J. L. & Brooker, R. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4074–4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson, J. L., Lockheart, M. S. K. & Brooker, R. J. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 181, 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green, A. L., Hrodey, H. A. & Brooker, R. J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 11226–11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frillingos, S., Sahin-Tóth, M., Wu, J. & Kaback, H. R. (1998) FASEB J. 12, 1281–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green, A. L., Anderson, E. J. & Brooker, R. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23240–23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura, N., Konishi, S., Iwaki, S., Kimura-Someya, T., Nada, S. & Yamaguchi, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20330–20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]